Abstract

The purpose of this work is to present the results of a margin reduction study involving dosimetric and radiobiologic assessment of cumulative dose distributions, computed using an image guided adaptive radiotherapy based framework. Eight prostate cancer patients, treated with 7–9, 6 MV, intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) fields, were included in this study. The workflow consists of cone beam CT (CBCT) based localization, deformable image registration of the CBCT to simulation CT image datasets (SIMCT), dose reconstruction and dose accumulation on the SIM-CT, and plan evaluation using radiobiological models. For each patient, three IMRT plans were generated with different margins applied to the CTV. The PTV margin for the original plan was 10 mm and 6 mm at the prostate/anterior rectal wall interface (10/6 mm) and was reduced to: (a) 5/3 mm, and (b) 3 mm uniformly. The average percent reductions in predicted tumor control probability (TCP) in the accumulated (actual) plans in comparison to the original plans over eight patients were 0.4%, 0.7% and 11.0% with 10/6 mm, 5/3 mm and 3 mm uniform margin respectively. The mean increase in predicted normal tissue complication probability (NTCP) for grades 2/3 rectal bleeding for the actual plans in comparison to the static plans with margins of 10/6, 5/3 and 3 mm uniformly was 3.5%, 2.8% and 2.4% respectively. For the actual dose distributions, predicted NTCP for late rectal bleeding was reduced by 3.6% on average when the margin was reduced from 10/6 mm to 5/3 mm, and further reduced by 1.0% on average when the margin was reduced to 3 mm. The average reduction in complication free tumor control probability (P+) in the actual plans in comparison to the original plans with margins of 10/6, 5/3 and 3 mm was 3.7%, 2.4% and 13.6% correspondingly. The significant reduction of TCP and P+ in the actual plan with 3 mm margin came from one outlier, where individualizing patient treatment plans through margin adaptation based on biological models, might yield higher quality treatments.

Introduction

Previous studies have reported that intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) has fewer gastrointestinal complications such as proctitis and rectal bleeding compared to 3D-CRT for men with prostate cancer (Sheets et al 2012). With the development of IGRT, the target localization accuracy and precision have been improved (Ghilezan et al 2004). However, IGRT cannot correct for daily deformation of the prostate gland and organs at risk (OAR) such as bladder and rectum. We have developed and previously validated an image guided adaptive radiotherapy (IGART) framework ‘in-house’, to track anatomical changes, such as displacement and deformation in the target and surrounding tissues (via daily cone beam CT (CBCT) images), and to perform daily dose accumulation (Wen et al 2012). The goal of this framework is to determine the actual daily dose delivered to the patient through the treatment course. We hypothesize that, using our framework, we will be better able to account for systematic and random setup errors, as well as daily physiological changes in the prostate and surrounding normal organ volumes, and, consequently, that we will be able to reduce planning margins. The purpose of this work is to describe the methods and results of a margin reduction study involving dosimetric and radiobiologic assessment of cumulative dose distributions, computed using this framework.

Material and methods

Treatment planning

Eight prostate cancer patients receiving IMRT were included in this retrospective study approved by our Institutional Review Board. A partially full bladder and empty rectum were required during simulation and daily treatment. Patients were simulated using 3 mm slice thicknesses with a Brilliance CT 16-slice (Philips Medical Systems, Andover, MA). The technical settings of the pelvis protocol were 120 kV, 500 mAs. The prescription dose was 75.6 Gy (1.8 Gy × 42 fractions) except for patients 2 and 4, who had prescribed doses of 80 Gy (2 Gy × 40 fractions) for the requirement of a gene therapy study. The CTV included the entire prostate gland and the inferior 10 mm of the proximal seminal vesicles. The PTV was created by adding a 10 mm margin to the CTV except posteriorly, where the margin was 6 mm to limit dose to the anterior rectal wall. The rectum was drawn on CT slices starting at the anal verge and continuing superiorly for a maximal length of 15 cm or until the rectosigmoid junction. The standard margin scheme in our clinic will be referred to as ‘10/6 mm’. All patients were treated with 7–9, 6 MV, IMRT fields.

IGART

Previously, we developed and reported on an offline framework for performing IGART (Wen et al 2012). Validation of the various processes in the IGART workflow, including dose calculation on CBCT image data sets, and accuracy of the deformable image registration (DIR) algorithm, were also carried out. The accuracy of DIR on patient image sets was evaluated using three different approaches: landmark matching with fiducial markers, visual evaluation of CT images, and unbalanced energy (UE), a voxel based algorithm to quantify displacement vector field (DVF) errors (Zhong et al 2007). The dose calculated on each CBCT image set was warped back to simulation CT image datasets to determine the ‘actual dose’ delivered to the patient. The dose delivered at each treatment fraction was accumulated to reflect the final dose given to the patient (Wen et al 2012).

Margin reduction

For each patient, two additional IMRT plans were generated using a smaller margin applied to the CTV. The PTV margin for the original plan was 10/6 mm. The margin was reduced to: (a) 5 mm uniformly except posteriorly, where it was 3 mm (5/3 mm), and (b) 3 mm uniformly (3 mm).

The new IMRT plans were recalculated on each CBCT image set. Using the same DVFs generated from offline DIR, dose was reconstructed and accumulated over all fractions to determine the actual dose. The actual dose was then compared to the dose calculated in the original plan (static plan), without deformation to evaluate the doses delivered to the PTV and OARs at each margin setting.

Plan evaluation

Tumor control probability (TCP) and normal tissue complication probability (NTCP) were evaluated to determine differences in dose distributions between the static and actual plans across the three margin settings. TCP was based on a Poisson statistics-based model that has been described previously (Liu et al 2009). We used the classic four parameter Lyman– Kutcher–Burman model to calculate NTCP. The parameter estimates of the gastrointestinal toxicity (GI,) i.e. late grade 2/3 and grade 3 rectal bleeding) for the model were defined by a large multi-center trial of 547 prostate cancer patients (Rancati et al 2004). Using grade 2/3 late bleeding as the endpoint, the parameters were as follows: TD50 81.9 Gy, m (steepness) =0.19, and n (seriality) = 0.23. TD50 is defined as dose received by the volume that could lead to a complication probability of 50 percent. m is the slope of the complication probability versus dose curve. n is the volume dependence of the complication probability. For grade 3 late bleeding as the endpoint, TD50 = 78.6 Gy, m = 0.06, and n = 0.06. The parameter estimates of the grade 1 or greater genitourinary toxicity (GU) were based on a previous study of 128 patients (Cheung et al 2007). The parameters were as follows: TD50 = 77.6 Gy, m 0.02, and n 0.01.

The complication free tumor control probability (P+) was used to rank the static and actual dose at each margin setting by combining TCP and NTCP (Kallman et al 1992). P+ is defined as:

| (1) |

where δ is fraction of patients having independent tumor and normal tissue response. A fixed value of 20% was used for δ in our study.

Results

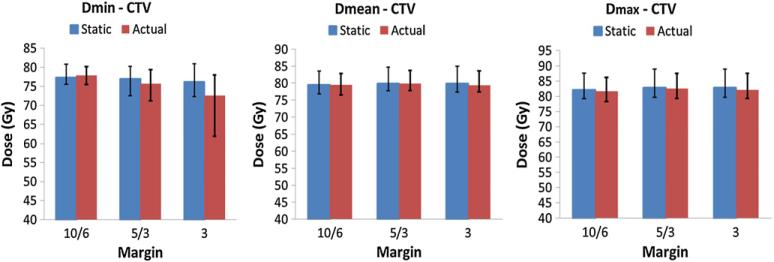

Target coverage—dosimetric evaluation

The average values of CTV minimum, mean and maximum doses of all eight patients for both static and actual plans are shown in figure 1 at each margin setting. Error bars represent the minimum and maximum values of all patients. With the 10/6 mm margin, differences in the CTV mean, minimum and maximum doses between the static and actual plans were all within 2%. When the margin was reduced to 5/3 mm, the difference in CTV minimum dose between static and actual plans was within 2% for three patients, 2–5% for four patients. The difference was 7% for patient 7. The CTV mean and maximum doses were within 2% agreement. When a 3 mm uniform margin was applied, there was a large variation in the percentage difference of the CTV minimum dose. The difference was within 1% for one patient, 4–7% in six patients, and 20% for patient 7. The differences in the CTV mean and maximum doses were within 2% for all patients.

Figure 1.

Comparisons of CTV minimum (left), mean (middle) and maximum (right) doses between static and actual plans. Vertical bars represent the average value of all eight patients at each margin setting. The bar on the left-hand side shows the static dose while the right-hand side shows the actual dose. Error bars represent the minimum and maximum values for all patients.

Target coverage—radiobiological evaluation

The CTV TCP was computed for all three planning margin scenarios. The average percent differences of TCP between the actual and static plans over eight patients were 0.4% (range, −3.7%–6.3%) with 10/6 mm margin, 0.7% (range, 2.8%–9.7%) with 5/3 mm margin, and −11.0% (range, −71.3%–2.1%) with 3 mm uniform margin respectively. There was significant percent difference (−71.3%) in patient 7 with 3 mm margin. The average percent difference in TCP between the actual and static plans was within 2.3% for the other seven patients.

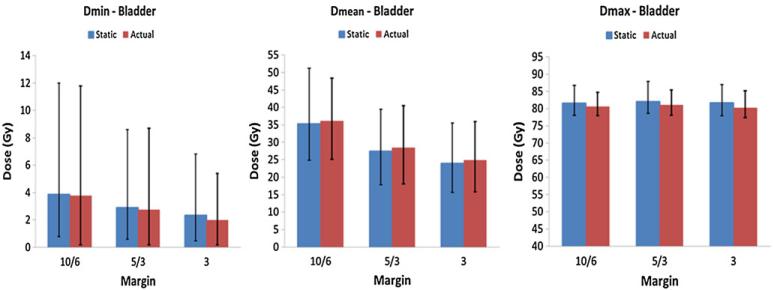

Normal tissue evaluation

The average values of minimum, mean and maximum doses for rectum and bladder of all eight patients are summarized in figures 2 and 3 respectively at each margin setting. Error bars represent the minimum and maximum values of all patients.

Figure 2.

Comparisons of minimum (left), mean (middle) and maximum (right) rectal doses between static and actual plans. Vertical bars represent the average value of all eight patients at each margin setting. The bar on the left-hand side shows the static dose while the right-hand side shows the actual dose. Error bars represent the minimum and maximum values for all patients.

Figure 3.

Comparisons of minimum (left), mean (middle) and maximum (right) bladder doses between static and actual plans. Vertical bars represent the average value of all eight patients at each margin setting. The bar on the left-hand side shows the static dose while the right-hand side shows the actual dose. Error bars represent the minimum and maximum values for all patients.

The mean, minimum and maximum doses to rectum and bladder for each patient are summarized in figures 2 and 3 respectively. The actual treatment plans resulted in higher mean doses to the rectum and bladder in comparison to the corresponding static treatment plans. For the rectum this increase in dose in the actual plans was as follows: (a) 15.6% (range, 0.6%– 42.4%) for the 10/6 mm margin; (b) 21.6% (range, 0.2%–51.8%) for the 5/3 mm−margin, and (c) 23.6% (range, −2.9%–55.6%) for the 3 mm −uniform margin. The difference in the maximum rectal dose was insignificant, within 2.4% for all three margin scenarios.

Similarly, for the bladder the actual plans showed higher mean dose than the corresponding static plans, as follows: (a) 4.1% (range, −18.1%–30.7%) for the 10/6 mm margin; (b) 5.4% (range, −24.8%–36. 9%) for the 5/3 mm margin, and (c) 5.7% (range, 26.6%–37.8%) for the 3 mm uniform margin. The maximum bladder dose was within 2.8%−between the actual and static plans.

In general, the rectum and bladder doses were reduced as the planning margin was reduced. As the margin was reduced from 10/6 to 5/3 mm in the actual plans, the mean dose to rectum was reduced by 20.1% (range, 9.4%–40.3%) among eight patients. As the margin was reduced from 5/3 to 3 mm uniformly, the dose reduction was 8.5% (range, 3.3%–21.8%). For the bladder, the mean dose was reduced by 26.9% (range 14.1%–42.0%) as the margin was reduced from 10/6 to 5/3 mm and 14.3% (range, 6.6%–30.3%) as the margin was reduced from 5/3 to 3 mm uniformly. Plans with different margin settings also had similar maximum dose, located at the rectal wall.

Grade 2/3 and grade 3 late rectal bleeding were also evaluated using parameters defined through a multi-center trial of 547 prostate cancer patients. The corresponding NTCPs for grades 2/3 and grade 3 rectal bleeding are shown in figure 4, for static and actual plans for the three different planning margins. The mean difference in NTCP for grades 2/3 bleeding between the static and actual plans with margin of 10/6, 5/3 and 3 mm was 3.5%, 2.8% and 2.4% respectively. For grade 3 late rectal bleeding, the mean difference was 4.1%, 3.5% and 2.6% respectively. In the actual plans, NTCP for late rectal bleeding was reduced by 3.6% on average when the margin was reduced from 10/6 mm to 5/3 mm, and further reduced by 1.0% on average when the margin was reduced to 3 mm uniformly.

Figure 4.

NTCP comparison of late rectal bleeding between the static (solid line) and actual (dashed line) plans at the three margins. Markers with filled square showed NTCP of real grade 2/3 bleeding. Markers with filled triangle represented NTCP of real grade 3 bleeding only.

Complication free tumor control probability

P+ was calculated using TCP and NTCP for the rectum since late rectal toxicity is relatively more important in the decision making. The P+ values are shown in figure 5, for static and actual plans for the three different planning margins. The average percent differences of P+ between the actual and static plans over eight patients were –3.7% (range, 8.3%–5.4%) with 10/6 mm margin, −2.4% (range, −7.5%–10.0%) with 5/3 mm margin, and −and 13.6% (range, −73.0%–2.6%) with 3 mm uniform margin respectively. Similarly, there was − significant percent difference (−73.0%) in patient 7 with 3 mm margin. The average percent differences of P+ were within 5.0% for the remaining patients.

Figure 5.

P+ comparison between static (solid line) and actual (dash line) plans at three margins 10/6, 5/3, and 3 mm.

Discussion

This study explored dosimetric and radiobiological endpoints arising from margin reduction in an IGART framework for prostate cancer. Validation of the accuracy of the steps involved in deformation and dose mapping is a crucial process. We have evaluated procedures in our framework by performing phantom experiments and patient studies (Wen et al 2012). Studies have shown that smaller PTV margins can reduce the computed rectal NTCPs by up to 10% (Huang et al 2008; Ghilezan et al 2004). Sandler et al showed that patient-reported quality of life outcomes were improved by decreasing PTV margin to 3 mm (Sandler et al 2010). We have completed a prospective study of 27 patients, in which the interfraction setup error and residual errors were investigated using multiple imaging modalities (Mayyas et al 2013). The PTV margin, derived following Van Herk's formalism (van Herk et al 2000) was on the order of 10 mm to compensate for inter-fraction setup errors using skin-tattoo alignment for localization. Using CBCT-based alignment, residual errors were less than 3 mm in all directions (Mayyas et al 2013). Using daily CBCT-based image guidance it was concluded that the setup margin can be reduced to 3 ~ 5 mm to properly account for setup uncertainties (Mayyas et al 2013). (Chung et al 2004) analyzed the position of fiducial markers in 17 patients using portal imaging. The center of mass displacement of the prostate was within 3 mm in all directions. The data from Beltran et al suggested that 3.0 mm was the minimum necessary margin to compensate for inter- and intra-fraction prostate motion (Beltran et al 2008). While this study only included eight patients, the results here are in agreement with other groups that the minimum population-based margin is approximately 3–5 mm. However, if geometric uncertainties resulting from organ deformation are not considered, the implementation of a smaller PTV margin is likely to have a negative dosimetric and radiobiological impact. We noted that there were no differences in the mean and maximum doses in the CTV for the three margin scenarios. However, as the margin was reduced, the discrepancy in the CTV minimum dose increased. Patient 7 showed the largest deviation in the CTV minimum dose coverage with 3 mm margin due to the geometric shift caused by deformation. For this patient, the uniform 3 mm margin plan could lead to significant reduction in the predicted TCP value. Wu et al reported that a 5 mm PTV margin is required to keep the difference between accumulated and prescription doses within 2% (Wu et al 2006). Our results are generally consistent with the study of Wu et al but it is important to view any margin reduction study, different than standard-of-care, with extreme caution. Ultimately clinical outcomes need to be studied to unequivocally assess the benefit of margin reduction.

The rectal mean dose increased in the actual plans relative to the corresponding static plans for all patients likely due to the lack of adherence to the full bladder/empty rectum initial conditions in the simulation. This suggests that IGRT alone cannot correct the daily deformation of the rectum. The treatment plans tend to underestimate the rectal dose delivered in the actual treatment. Several studies have discussed the impact of dose schemes and techniques on the therapeutic ratio for prostate cancer treatments (Amer et al 2003; Huang et al 2008). In our study, predicted NTCP (for late rectal bleeding endpoint) was 2.4–4.1% higher in the actual plan than that in the static plan. Such variability should be considered in evaluating the radiobiological effects of treatments.

We also predict that reducing the margin is an effective means to reduce GI toxicity. When the margin was reduced from 10/6 to 5/3 mm, NTCP of late rectal bleeding was decreased by 3.6% on average. When the margin was reduced to 3 mm uniformly, NTCP was further reduced by another 1.0%. Considering that smaller margins do not result in a significant reduction in the predicted TCP value, IGART has the potential to improve the therapeutic ratio in combination with smaller planning margins.

We also performed a test of the TCP and corresponding P with different surviving fraction (SF2) parameters, and clonogenic cell density to evaluate the robustness of our results. Since standard fractionation was used in the treatment, α/β ratio was excluded for evaluation. The effect of δ on P+ was investigated by Liao et al (2010) and the impact of δ on P was negligible. When SF2 was 0.5, there were undetectable differences in TCP and between the static and actual plans since TCP was 99% for all plans and was independent of cell density. When SF2 was 0.6, TCP depended on cell density only when cell density increased from 105 to 106 cm−3 as shown in figure 6. The P+ values shown in figure 5 represented less responsive tumor cells (SF2 = 0.6) and early stage prostate cancer (cell density 106 cm−3). The P+ values predicted that the actual complication free tumor control possibility was inferior to the static one at each margin setting in general. The results demonstrated that current radiobiological evaluation based on the static treatment planning could not accurately predict the treatment outcome. Reducing the margin to 5/3 mm showed systematic improvement on the actual P+ values for all patients. Further reducing the margin to 3 mm did not provide any gain on P+. And the P+ value was significantly degraded for patient 7 with 3 mm margin. By combining TCP and NTCP, P+ provides a useful guidance to understand the clinical results in the relative ranking of the margins.

Figure 6.

TCP versus N0 evaluation between static (solid line) and actual (dash line) plans at three different margins 10/6 (markers with circle), 5/3 (markers with triangle) and 3 mm (markers with diamond). N0 is in log scale, ranging from 103 to 106.

A similar radiobiological analysis was performed for the bladder. Data published by Cheung was used for NTCP calculation (TD50 = 77.6 Gy, n 0.00995, m 0.022) to evaluate late GU toxicity with grade equal or greater than 1. Since n is small, the bladder is considered a serial organ when the risk of low grade GU toxicities is included. Therefore the complication is directly related to the bladder Dmax. The effectiveness of margin reduction to reduce the mild GU toxicity depends heavily on the prescription dose and the maximum bladder dose. No direct correlation was found in this study between the planning margin and NTCP, because even though the mean dose decreased with smaller margins, the maximum bladder dose showed no predictable variation as a function of margin. A future study will focus on the correlation between PTV margin and severe GU toxicity.

We applied a uniform margin to all patients. However, even with a cohort of eight patients, we noticed large inter-patient variation in NTCP. Patient compliance with regard to bladder and rectal physiology prior to treatment was found to be an important factor. All eight patients were instructed on proper bowel preparation, and how to maintain bladder filling at each treatment. If the rectum showed large deformational changes, the patient was taken off the table and given time to ensure that the bladder and bowel physiology closely resembled that at the time of simulation. Patient 2 had difficulty complying with the instructions; therefore there was large deformation in the rectum which could not be corrected by rigid transformation. Even though patient 7 did not have significant difficulty complying with bowel and bladder preparation instructions, the systematic geometric errors caused by deformation through the treatment course could lead to a treatment failure if 3 mm margin was applied. The benefit of margin reduction was dependent on the individual patient, which has been reported by other studies as well (Song et al 2006, Ghilezan et al 2004). Moreover, the lack of consistent physiologic conditions in the bladder and rectum on a daily basis, due in part to lack of preparation, produces intra- and inter- patient variability. Huang et al quantified the dosimetric and radiobiological impact by reducing PTV margin from 7 mm to 3 mm for IMRT plans (Huang et al 2008). However, their results were also subject to large inter-patient variability. This suggests that individualizing patient margins may be helpful in achieving the best clinical outcome and may facilitate better plan re-optimization, as necessary during the treatment course. The assessment of the re-planning/re-optimization is a subject of future investigation.

Conclusion

We applied an ‘in-house’ developed framework to determine the actual doses delivered to a cohort of eight patients with early stage prostate cancer. We demonstrated that margin reduction is an effective method to improve the therapeutic ratio but has to be implemented with extreme caution. A prospective study with a large patient population is warranted to produce more conclusive results.

Acknowledgment

This work has been supported in part by a research grant from Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA.

References

- Amer AM, Mott J, Mackay RI, Williams PC, Livsey J, Logue JP, Hendry JH. Prediction of the benefits from dose-escalated hypofractionated intensity-modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2003;56:199–207. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00086-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltran C, Herman MG, Davis BJ. Planning target margin calculations for prostate radiotherapy based on intrafraction and interfraction motion using four localization methods. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2008;70:289–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung MR, Tucker SL, Dong L, de Crevoisier R, Lee AK, Frank S, Kudchadker RJ, Thames H, Mohan R, Kuban D. Investigation of bladder dose and volume factors influencing late urinary toxicity after external beam radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2007;67:1059–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung PW, Haycocks T, Brown T, Cambridge Z, Kelly V, Alasti H, Jaffray DA, Catton CN. On-line aSi portal imaging of implanted fiducial markers for the reduction of interfraction error during conformal radiotherapy of prostate carcinoma. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2004;60:329–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghilezan M, Yan D, Liang J, Jaffray D, Wong J, Martinez A. Online image-guided intensity-modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer: how much improvement can we expect? A theoretical assessment of clinical benefits and potential dose escalation by improving precision and accuracy of radiation delivery. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2004;60:1602–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.07.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SH, Catton C, Jezioranski J, Bayley A, Rose S, Rosewall T. The effect of changing technique, dose, and PTV margin on therapeutic ratio during prostate radiotherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2008;71:1057–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallman P, Agren A, Brahme A. Tumour and normal tissue responses to fractionated non-uniform dose delivery. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1992;62:249–62. doi: 10.1080/09553009214552071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y, Joiner M, Huang Y, Burmeister J. Hypofractionation: what does it mean for prostate cancer treatment? Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2010;76:260–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Ajlouni M, Jin JY, Ryu S, Siddiqui F, Patel A, Movsas B, Chetty IJ. Analysis of outcomes in radiation oncology: an integrated computational platform. Med. Phys. 2009;36:1680–9. doi: 10.1118/1.3114022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayyas E, et al. Evaluation of multiple image-based modalities for image-guided radiation therapy (IGRT) of prostate carcinoma: a prospective study. Med. Phys. 2013;40:041707. doi: 10.1118/1.4794502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rancati T, et al. Fitting late rectal bleeding data using different NTCP models: results from an Italian multi-centric study (AIROPROS0101) Radiother. Oncol. 2004;73:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler HM, Liu PY, Dunn RL, Khan DC, Tropper SE, Sanda MG, Mantz CA. Reduction in patient-reported acute morbidity in prostate cancer patients treated with 81-Gy Intensity-modulated radiotherapy using reduced planning target volume margins and electromagnetic tracking: assessing the impact of margin reduction study. Urology. 2010;75:1004–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.10.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheets NC, et al. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy, proton therapy, or conformal radiation therapy and morbidity and disease control in localized prostate cancer. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2012;307:1611–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song WY, Schaly B, Bauman G, Battista JJ, Van Dyk J. Evaluation of image-guided radiation therapy (IGRT) technologies and their impact on the outcomes of hypofractionated prostate cancer treatments: a radiobiologic analysis. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2006;64:289–300. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Herk M, Remeijer P, Rasch C, Lebesque JV. The probability of correct target dosage: dose-population histograms for deriving treatment margins in radiotherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2000;47:1121–35. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00518-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen N, Glide-Hurst C, Nurushev T, Xing L, Kim J, Zhong H, Liu D, Liu M, Burmeister J, Movsas B, Chetty IJ. Evaluation of the deformation and corresponding dosimetric implications in prostate cancer treatment. Phys. Med. Biol. 2012;57:5361–79. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/57/17/5361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Liang J, Yan D. Application of dose compensation in image-guided radiotherapy of prostate cancer. Phys. Med. Biol. 2006;51:1405–19. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/6/003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong H, Peters T, Siebers JV. FEM-based evaluation of deformable image registration for radiation therapy. Phys. Med. Biol. 2007;52:4721–38. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/52/16/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]