Abstract

Cryptococcus neoformans is an environmental fungus that can cause severe disease in humans. C. neoformans encounters a multitude of stresses within the human host to which it must adapt in order to survive and proliferate. Upon stressful changes in the external milieu, C. neoformans must reprogram its gene expression to properly respond to and combat stress in order to maintain homeostasis. Several studies have investigated the changes that occur in response to these stresses to begin to unravel the mechanisms of adaptation in this organism.

Here we review studies that have explored stress-induced changes in gene expression with a focus on host temperature adaptation. We compare global mRNA expression data compiled from several studies and identify patterns which suggest that orchestrated, transient responses occur. We also utilize the available expression data to explore the possibility of a common stress response that may contribute to cellular protection against a variety of stresses in C. neoformans. In addition, we review studies that have revealed the significance of post-transcriptional mechanisms of mRNA regulation in response to stress and we discuss how these processes may contribute to adaptation and virulence.

Cryptococcus neoformans is an environmental yeast-like fungus that is capable of infecting humans and causing severe disseminated disease1. Spores, produced either by bipolar mating between the “a” and “alpha” mating partners or by same-sex mating by alpha cells (monokaryotic fruiting), and/or dessicated yeast cells are believed to be the infectious propagules1, 2. In immunocompromised individuals, primary pulmonary infections often progress into disseminated infections facilitated by proliferation and survival in macrophages1. Meningioencephalitis is the most common manifestation of disseminated disease due to the robust neurotropic nature of this organism1. The host environment is very different from the natural niche of this organism, and C. neoformans encounters dynamic milieus throughout the progression of infection sensed as cellular stress that it must overcome in order to adapt and survive within the host.

The C. neoformans species complex is divided into two varieties. C. neoformans var. grubii encompasses serotype A of which the wild type strain H99 and congenic mating partners KN99a and KN99α form the basis for most Serotype A laboratory work. C. neoformans var. neoformans encompasses serotype D of which the congenic mating pair JEC21 (MAT α) and JEC20 (MAT a) form the basis for laboratory work. The H99 derived strains are highly virulent and have been used for many of the studies of virulence and gene expression whereas the JEC21/20 pair, because of their facility in mating, has been used to study mating and sexual development in C. neoformans, though both sets of strains have been utilized to investigate many aspects of cryptococcal pathogenesis.

Several investigators have begun to set the groundwork for understanding how C. neoformans adapts to the multitude of stresses within the host environment. Gene expression profiles comparing stressed conditions to nonstressed conditions have allowed researchers to focus their studies on genes that are likely important for adaptation to specific stresses. Beyond the determination of a gene's up- or down-regulation during a specific stress, patterns can be identified within global analyses of mRNA expression that shed light on the orchestration of proper stress responses, and we can start to draw conclusions and develop hypotheses from the stories that the data convey. For example, the gene expression profiles during time-courses allow us to observe temporal patterns that are likely important for proper responses. We can also compare the available data to ask whether responses are unique to a specific stress or if they are triggered by multiple stresses. We can glean very important concepts utilizing this type of approach. Caution, of course, must be taken when comparing independent sets of data as growth conditions and experimental design undoubtedly affect the results of these types of analyses. For example, it is important to understand that gene expression profiles taken immediately following a stress are different from those taken later, during maintenance of growth after exposure to the stressor. The differences between these conditions, too, are interesting and add complexity to the processes of stress adaptation in C. neoformans.

In recent years, our understanding of gene expression regulation has expanded beyond that of transcriptional control, and control of mRNA fate has become a major topic of interest. Post-transcriptional events including alternative splicing, export, changes in mRNA stability/decay, mRNA localization, and translatability have been demonstrated to significantly influence the regulation of gene expression3-5. These events do not occur at random, but seem to be specific and highly orchestrated. Particular subsets or classes of functionally related transcripts undergo specific post-transcriptional regulation at a certain times and in response to specific stimuli. These controlled events are coordinated as “mRNA regulons” by which RNA-binding proteins that recognize and bind cis regulatory elements or certain secondary structures found in related classes of mRNAs facilitate a specific post-transcriptional process3, 4. In combination with transcriptional control, these post-transcriptional mechanisms can enhance and fine-tune responses allowing rapid and controlled changes. Investigations of these post-transcriptional mechanisms in C. neoformans have only recently begun, but they have already demonstrated that these processes contribute to the adaptability and virulence of C. neoformans.

In this review, studies that have investigated RNA biology in response to stress in C. neoformans will be discussed. We will compare gene expression profiles compiled from several studies that have investigated stress responses, and expose patterns and themes found within the data. We will utilize these data to address the possibility of an environmental stress response in C. neoformans. Finally, we will discuss investigations that have begun to build a foundation for understanding post-transcriptional mechanisms of gene regulation and how they contribute to stress adaptation and virulence of C. neoformans.

PATTERNS IN STRESS-INDUCED GENE EXPRESSION

A trend toward transient induction of stress response mRNAs

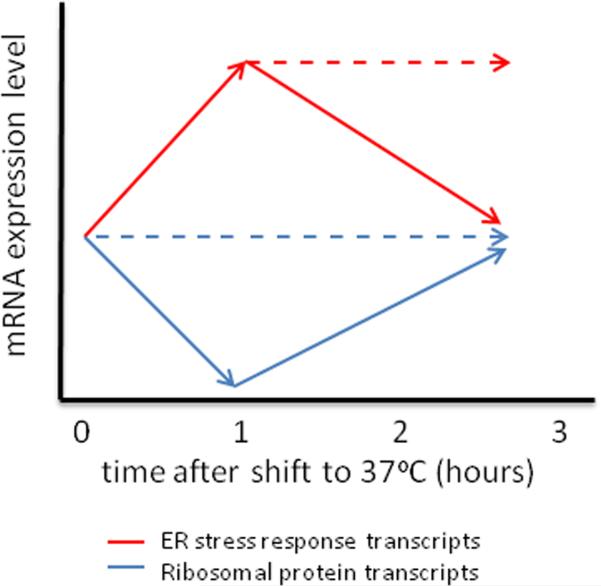

When comparing gene expression during stress over periods of time, as well as comparing data compiled from independent experiments designed to investigate stress-induced gene expression, several patterns can be observed that may contribute to understanding the complexity involved in orchestrating proper stress responses. In our recent work, our laboratory has revealed transient induction of the ER stress response genes synchronized with transient repression of the ribosomal protein (RP) transcripts in response to host-temperature shock6, 7. We demonstrate that maximal induction of ER stress transcripts and maximal repression of the RP transcripts simultaneously occur 60 minutes after temperature shift, followed by “recovery” to pre-shift quantities (Fig. 1). It is believed that coordinate down-regulation of highly abundant house-keeping genes with up-regulation of genes important for repair results in stress-induced reprogramming that promotes more efficient use of cellular energy8. It is likely that other functionally related classes of transcripts undergo similar induction (genes important for stress adaptation) or repression (abundant genes that are not critical for the initial response to stress) during this immediate stage after exposure to the stress, however we have not yet analyzed other functionally related groups of mRNAs in fine detail. Interestingly, Chow et al. analysed gene expression of cells exposed to heat shock (30°C to 42°C) over a 30-minute time course, and observed gradual induction of genes related to the thioredoxin and glutathione systems in addition to heat shock proteins and other ER stress related genes, indicating that balancing the cellular redox potential is likely important during heat stress9. Genes involved in the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway were gradually repressed during the 30-minutes of heat shock in this study9, suggesting that sterol production is not necessary for membrane fluidity at this higher temperature. Longer time courses are required to determine whether these changes are transient, however. Notably, a shift to host-temperature (37°C) is a mild heat shock compared to a shift to 42°C, and it is likely that the gene expression profiles reflect this difference in severity. Interestingly, in an earlier study in which gene expression was analyzed every 3 hours for 12 hours following a shift to 37°C, the majority of differential gene expression occurred at later time-points10. There was very little overlap in the genes affected in this study compared to the Chow study, and it is likely that at these later times, culture density and/or nutrient depletion may have contributed to these differences. In addition, while analyzing the gene expression changes over a longer period of time may provide clues as to what genes are important for maintaining growth at host temperature (i.e. the transcription factor Mga2 was identified in this study), our data suggest that 3 hours may be too long to observe the changes required for adaptation and instead, shed light on changes that occur during “maintenance” (see below).

Figure 1. Transient changes in ribosomal protein (RP) transcripts and ER stress response transcripts during host-temperature adaptation are mediated by Ccr4.

Upon a shift from 30°C to 37°C, RP transcripts are immediately repressed, at least in part, by Ccr4-dependent degradation. After one hour, maximum repression is reached and RP transcript levels recover to pre-shift abundance in the wildtype (solid blue line). In the absence of Ccr4, RP transcripts remain stable during the temperature shift and little change is observed in steady state levels (dashed blue line). Immediately following the temperature shift ER stress transcripts are induced to elicit the ER stress response (in both the wild type and the ccr4Δ mutant). Peak induction is reached after 1hr. During the second and third hours the resolution of the ER stress response is facilitated by repression of the ER stress mRNAs to pre-shift levels in the wild type (solid red line). The resolution of the ER stress response is mediated, in part, by Ccr4-dependent degradation of the ER stress mRNAs, as these transcripts remain at induced levels in the ccr4Δ mutant (dashed red line).

In a recent study, transient patterns of gene expression have also been observed in C. neoformans cells exposed to H2O2-induced oxidative stress11. Upadhya et al. demonstrated that the total number of genes that undergo induction or repression is transient, with a gradual increase in numbers during the first 30 minutes after treatment with 1mM H2O2 followed by a decline during the next 30 minutes11. This pattern was in concordance with the rate at which the yeast was able to remove 1mM H2O2 (majority is depleted by 30 min). Several classes of transcripts were differentially regulated at all time points, however biological processes were most affected at the 30 and 45 minute time points, indicating that cellular functions during H2O2 stress are temporally regulated11. Indeed certain classes were greater represented earlier in the time course suggesting importance in regulation immediately following stress, whereas other classes were represented at later time points suggesting a role in recovery.

An Environmental Stress Response in C. neoformans?

The pattern of transient induction of certain genes with concomitant repression of certain other genes immediately following exposure to stress is not a new phenomenon. Work in S. cerevisiae has demonstrated that in response to many different stresses, a core set of genes is routinely induced whereas another set of genes is synchronously repressed12-14. This occurrence, referred to as the Environmental Stress Response (ESR), is thought to protect the cells from stressful events that result in suboptimal conditions in the internal milieu that threaten cellular homeostasis13, 15. (See Box 1.)

Several studies have identified signaling pathways that contribute to the ability of C. neoformans to adapt to specific environmental stresses. In fact, both Hog1 and Pka1 signaling contribute to the proper gene expression profiles in response to multiple environmental stressors16, 17. A core set of genes that is co-ordinately regulated in response to multiple sub-optimal conditions, however, is not clear. In a study that set out to explore the stress-activated HOG pathway in C. neoformans, Ko et al. analyzed gene expression profiles from cells exposed to oxidative stress (H2O2), osmotic stress (2M NaCl), and stress induced by the anti-fungal drug Fludioxonil16. Similar to studies performed in S. cerevisiae12, 13, S. pombe18, and C. albicans19, 20, genes that were co-ordinately regulated in the three conditions were identified to determine if a shared regulated response existed in C. neoformans in response to general stress. Interestingly, only 125 mutually inclusive genes were identified, falling significantly short of the predicted ~500-900 ESR genes in S. cerevisiae 12, 13. In a separate study, Missall et al. observed a significant down-regulation of genes related to osmotic or nutritional stress in response to acidified nitrite-induced nitrosative stress, suggesting that responses to different environmental stresses may be more specialized in C. neoformans21. These findings are slightly reminiscent of studies in Candida albicans that suggest an absence of ESR20, and instead a more specialized profile for each stress with a very small subset of “core stress genes” that are commonly affected19. Supporting this, Ko et al. compared the shared, coregulated genes that overlapped only during oxidative and osmotic stress in C. neoformans to differentially expressed genes during similar stresses in other fungal species (S. cerevisiae, S. Pombe, and C. albicans) and found almost no correlation, suggesting that the stress mechanisms utilized in these organisms have diverged greatly16. This is not surprising given that signaling components involved in triggering ESR appear to be very divergent (reviewed in Gasch, 200722). It is notable, however, that HOG signaling in C. neoformans partially regulates the differential expression of the coordinately regulated genes16, which has also been demonstrated in C. albicans19.

It is not yet clear as to whether or not C. neoformans demonstrates a true ESR. A hallmark trait of the ESR is the transient response of these genes. The authors of the C. neoformans study did not comment on whether the 125 genes that were differentially regulated during all three stress conditions were transiently induced/repressed. In addition, ESR studies in S. cerevisiae utilize optimized potency of stress-inducing agents in order to ensure that the majority of cells are viable as well as to control the intensity of the response, as it has been found that the ESR is proportional to the magnitude of the environmental change13, 14. While several studies that have analyzed the early profiles of C. neoformans cells exposed to different environmental stresses show correlation in the functional categories that are affected, a core set of specific genes has not been identified beyond the findings of Ko et al. It may be important to include expression profiles from more stress conditions and also to decrease the stringency in the definition of how we define ESR genes. Perhaps a large scale comparison of the available data will shed light on the existence of an ESR; however, it is important to note that multiple variables exist in these types of studies that can certainly affect the interpretation of this type of data. In fact, in the aforementioned study, Upadhya et al. demonstrated that the choice of media, cellular density, and concentration of H2O2 all affect cellular viability as well as the ability of C. neoformans to breakdown H2O211. It is likely, then, that the stress response would be altered with variation in any one of these factors, and emphasizes the importance to take all variables into consideration when designing individual experiments and comparing the data across experiments.

While the environmental stress defense may not be highly correlated between C. neoformans and S. cerevisiae, the phenomenon of cross-resistance has been demonstrated. Often, related groups of genes that are functionally important for regulating defense against a specific stress also undergo differential regulation in response to other stresses, and therefore pre-exposure to one stress protects cells from another stress. In a study that analysed the gene expression profile of C. neoformans following exposure to the anti-fungal triazole drug, Fluconazole (FLC), Florio et al. found that several genes that function in oxidoreduction and cell wall maintenance were significantly enriched or repressed23. Further investigation, indeed, confirmed that prior exposure to FLC protected cells from cell wall inhibitors and from H2O2 induced oxidative stress compared to cells that were not pre-treated with FLC23. Similarly, when cells were treated with H2O2, Upadhya et al. found that genes involved in ergosterol synthesis (the pathway in which FLC targets) and anti-fungal resistance genes were upregulated11. Studies from the Lodge laboratory have demonstrated that several aspects of the stress responses to oxidative stress and nitrosative stress overlap, especially in regard to metabolic processing and induction of thioredoxin genes11, 21. Interestingly, their data suggests that these responses are dependent on different regulatory mechanisms. Cross-resistance is a hallmark of ESR, and supports the existence of this defense mechanism in C. neoformans. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that some cross-resistance is due to specific mechanisms that are involved in responses to multiple sources of stress. Cross resistance, for example, has been shown to occur in ESR-deficient C. albicans when cells are pre-exposed to a mild heat shock prior to oxidative stress24, but mild osmotic or oxidative stress does not improve resistance to heat shock20. Interestingly, when Chow et al. investigated changes in gene expression in response to heat stress and nitrosative stress, they observed that genes induced by the nitric oxide stressor DPTA-NONOate were repressed under conditions of high temperature9. The reasoning for this correlation is unclear, but it seems likely that exposure to either stress may impair defense against the other, however cross-resistance was not tested.

Adaptation vs. Maintenance

With the exception of starvation, stress-responses seem to be transient. The transient nature of these responses suggests that cells undergo an adaptation phase that allows the cell to quickly adjust the internal milieu to allow for optimal growth under the new conditions. Following this adjustment, the cells recover and can maintain this new balance. It is reasonable to suggest, that some genes will remain induced or repressed even when the majority of transcript levels have “recovered”. Together, it is conceivable that the resulting gene expression profile from cells that undergo long-term growth and have adapted to a sub-optimal environment will be distinctive from profiles obtained from those grown under optimal conditions. The differences can be instrumental in identifying genes that contribute to both the ability of C. neoformans to adapt to the multitude of stresses that it encounters in the human host and ultimately, its pathogenic capacity.

Growth at host-temperature has been analyzed by several investigators to determine the factors involved in the ability of C. neoformans to proliferate in this environment. “Maintenance” is likely most easily studied for prolonged high temperature growth in comparison to other studies in which continuous addition of stressors would be required (i.e. H2O2 is degraded relatively quickly). Comparison of four studies9, 10, 25, 26 that have looked specifically at prolonged growth at 37°C show very little overlap. This finding highlights the inconsistencies that can be introduced when several variables exist in experimental design. Two studies utilized microarrays9, 10, one used representational difference analysis (RDA)25, and one study employed serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE)26. In addition, growth media and cellular density varied among the studies. Chow et al. analyzed cells grown to early log phase and found only 7 upregulated genes, which was considerably lower than the other studies, which analyzed cells grown to much higher densities. In addition, these genes did not overlap with the other studies.

Some conclusions could be drawn from comparing the studies. The RDS1 gene, a stress response related protein gene, was upregulated in two studies10, 25 although the contribution of this gene to temperature stress or virulence is unknown. Also, MGA2, which encodes a transcription factor that regulates transcription of genes involved in fatty acid biosynthesis was upregulated in one of these studies and found to contribute to the ability of C. neoformans to grow at host temperature10. Additionally, genes related to fatty acid biosynthesis and membrane composition were reported to be differentially regulated in 2 of the other studies25, 26. Surprisingly, many genes that have been reported to function in the ability of C. neoformans to persist at host-temperature have not been reported to be upregulated by temperature.

Given the very minor changes that were observed by Chow et al. when culture density was kept low, it is possible that the differences in the gene expression profiles during unstressed conditions and during maintenance of growth at host temperature are minor. If this is the case, it is tempting to speculate that following the transient adaptation phase, the cell resumes pre-stressed gene regulation and cellular processing similar to when it grows optimally. This raises the interesting question as to whether the transient adaptation phase is therefore a prerequisite for maintenance. Recent data from our laboratory supports that this may be the case, as mutant strains (ccr4Δ and rpb4Δ) that display prolonged adaptation phases, due to mutations that disrupt the transient gene expression changes that occur in response to host temperature, demonstrate growth defects when grown at 37°C6, 7 (see below).

MECHANISMS OF REGULATION OF mRNA

Although post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression has only just begun to be explored in C. neoformans, the few published studies already suggest that these processes contribute to the adaptability and pathogenic capacity of this organism. Most of this small body of work has demonstrated that post-transcriptional regulation, specifically alteration of mRNA stability/degradation, contributes to the ability of C. neoformans to adapt to host-temperature induced stress. Controlled alternative splicing and mRNA localization have also been revealed, and suggest that mechanisms that regulate the fate of mRNA are critical for proper regulation of gene expression and support the ability of C. neoformans to adapt to changing environments.

Localization

Elegant work in S. cerevisiae has shown that ribonucleo-protein complexes accumulate in punctate structures in the cytoplasm known as processing bodies (P-bodies) and stress granules, sites that facilitate enhanced mRNA degradation and stalled translation initiation, respectively, in response to specific stressors27-30. Kozubowski et al. were the first to confirm that C. neoformans is capable of assembling these stress-induced punctate bodies31. Specifically, it was demonstrated that upon shift to host temperature, GFP-tagged catalytic subunit A of calcineurin (Cna1) colocalizes with specific markers of both P-bodies and stress granules, indicating that mRNA decay and/or mRNA storage is important in the response to host temperature stress, and suggesting that Cna1 contributes to mRNA processing. Previous studies have established that calcineurin, the calcium-calmodulin-dependent serine/threonine specific phosphatase, is essential for growth of C. neoformans at host temperature32. In S. cerevisiae, signaling through calcineurin contributes to the proper responses to high cation concentrations, cell wall stress, and exposure to mating pheromone33. During these conditions, dephosphorylation of the S. cerevisiae calcineurin target, Crz1, results in translocation of this transcription factor from the cytoplasm to the nucleus and subsequent transcriptional activation of genes with promoters that contain the calcineurin-dependent response element33. Interestingly, while a C. neoformans ortholog of Crz1 has recently been identified, it seems that Crz1 is dispensable for growth at host temperature34. No other transcription factor targets of calcineurin have yet been identified in C. neoformans, and the association of Cna1 with P-bodies and stress granules suggests a novel function of calcineurin in this organism. The catalytic activity of calcineurin was not required for this temperature-dependent localization, as FK506 did not impair colocalization with P-bodies or stress granules31. Additionally, Cna1 was found in a punctate pattern with partial colocalization with P-bodies in response to high salt stress and osmotic stress indicating that calcineurin may associate with the mRNA decay machinery in response to a multitude of stressors31. Additionally, this suggests that mRNA processing may be an important mechanism of regulating gene expression during stress. In a more recent study, Cts1, a phospholipid binding protein and target of calcineurin, was shown to colocalize with Cna1 as well as P-body and stress granule markers at 37°C35. Despite localization of Cna1 and Cts1 to these structures, P-bodies and stress granules still form in the absence of Cts1 and Cna1, suggesting that neither of these proteins is required for assembly35. However, a direct role for Cna1 in the specific mRNA processes that occur in these complexes has not yet been investigated, and it is possible that these proteins may influence the rate of decay or may affect stalled translation initiation. It would be interesting to examine if deletion or loss of calcineurin results in defects in either of these processes in response to host temperature. Further, it would be interesting to assess whether calcineurin functions to dephosphorylate any of the proteins involved in these processes, specifically proteins that are common to both P-bodies and stress granules.

Stability/Decay

In two recent studies, mRNA decay in response to host temperature was specifically examined and was determined to significantly affect the ability of C. neoformans to adapt to stress induced by a shift to 37°C6, 7. The conventional mRNA degradation pathway is initiated by poly(A)-tail trimming by deadenylases, followed by removal of the 5’-7-methylguanosine cap by decapping enzymes36. Decapping leaves the 5’ end exposed for rapid exonucleolytic digestion by 5’ to 3’ exonucleases36. Deadenylation is the rate-limiting step in this process37, and is required for the subsequent step to occur. A null mutation of the cellular deadenylase, Ccr4, was previously demonstrated to have a major impact on the ability of C. neoformans to grow at host temperature38. This temperature-dependent growth defect was demonstrated to be, in part, due to severe cell wall integrity defects, and as expected, the ccr4Δ mutant strain was severely attenuated for virulence in a mouse model of cryptococcosis38. The temperature-dependent growth defect was only partially rescued by osmotic stabilization, suggesting other contributing factors to the temperature sensitivity of the ccr4Δ mutant. Comparative microarray analyses revealed that several functionally related classes of transcripts were upregulated in the ccr4Δ mutant strain compared to wild type following a shift to host temperature for ten minutes, suggesting that Ccr4-mediated mRNA degradation plays a role in the initial responses to this stress7. The largest of the functionally related classes of mRNAs upregulated in the absence of Ccr4 encode the ribosomal proteins (RP), and mRNA stability assays confirmed that RP-mRNAs are rapidly degraded immediately following host temperature stress in a Ccr4-dependent manner6. Furthermore, analysis of steady state RP-transcript levels following a shift to 37°C demonstrated that RP-transcript levels rapidly declined over the first hour, but increased to pre-shift abundance during the second hour, indicating that this rapid repression of RP-genes is transient6 (Fig. 1). This phenomenon of rapid repression of highly abundant genes (so called housekeeping genes) during stress is thought to facilitate the shift of available cellular energy to processes that are critical for proper stress responses8. The repression of RP-transcripts during host-temperature adaptation was absent in the ccr4Δ mutant.

Rapid repression of RP genes has previously been documented in S. cerevisiae39, 40. Studies by the Choder laboratory demonstrate that temperature-dependent decay of RP-mRNAs, specifically, is influenced by the dissociable RNA polymerase II subunit, Rpb440. Further work has suggested that Rpb4 and its binding partner, Rpb7, “imprint” transcripts during synthesis by binding them and marking for enhanced decay in the cytoplasm41 (See Box 2). This theory of coupling mRNA synthesis and degradation is enticing as it suggests a very elegant mechanism for tightly controlling the expression of specific genes, and ultimately allows for fine-tuned regulation of responses. Our laboratory confirmed that this Rpb4-mediated coupling is conserved in C. neoformans as an rpb4Δ mutant failed to demonstrate enhanced RP-transcript decay in response to host-temperature6. Additionally, deadenylation of RP transcripts is aberrant in the rpb4Δ mutant, suggesting that imprinting by Rpb4 may influence Ccr4-mediated poly(A)-tail trimming6. While Ccr4 acts on nucleic acid substrates, it lacks a nucleic acid binding domain, and therefore must be recruited to its targets. RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) have been identified that recruit Ccr4 to specific functionally related classes of mRNAs in S. cerevisiae42, 43. These RBPs help to orchestrate Ccr4-mediated decay regulons for enhanced decay of functionally related classes of transcripts during specific conditions. To date, there is no evidence for a direct interaction between Rpb4 and Ccr4, suggesting that other factors are involved in this coupling process.

As aforementioned, the down-regulation of genes that are normally highly abundant allows the cell to utilize its energy more efficiently by investing more in processes that contribute to overcoming the stress, including the production of proteins required for proper stress responses. During host-temperature adaptation, one class of transcripts that is upregulated in C. neoformans is the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response genes7. The ER stress response is triggered by the accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins, and it activates pathways involved in the production of chaperones that aid in protein folding. Our laboratory previously demonstrated that ER stress transcripts are transiently upregulated immediately following a shift to host temperature7. After one hour, levels of these mRNAs decline to pre-shift quantities mediated by enhanced Ccr4-dependent degradation7 (Fig. 1). This suggests that the ER stress response is required very early in host temperature adaptation, and that decreased mRNA stability contributes to regulating the duration of this response. In the absence of Ccr4, the ER stress response is constitutively active7, and this likely contributes to the growth and morphological defects observed in the ccr4Δ mutant strain38. In our more recent study, we elaborated on this mechanism and demonstrated that Rpb4 contributes to the temporally-regulated destabilization of ER stress transcripts that mediates the resolution of the ER stress response6. These data demonstrated that imprinting by Rpb4 is not exclusive to the RP transcripts in C. neoformans, and also suggested that imprinting of specific classes of mRNAs is triggered in a time-dependent manner.

To further support coupling of synthesis and decay via Rpb4 as a mechanism involved in host-temperature adaptation, we demonstrated that Rpb4 shuttles from the nucleus to the cytoplasm following a shift to 37°C6. Interestingly, Rpb4 is observed in a punctate pattern in the cytosol for up to 3 hours after the temperature shift6. This cytoplasmic localization coincides with our findings that Rpb4 contributes to the enhanced decay of both the RP transcripts (during the first hour) and the ER stress response transcripts (during the 2nd and 3rd hours). The transient nature of these responses was reflected in the movement of Rpb4 back to the nucleus by the fourth hour. While colocalization of Rpb4 with P-body markers has been shown in S. cerevisiae40, further work is needed to determine if the cytosolic, punctate structures to which Rpb4 localizes are either P-bodies, sites predominantly where mRNA decay occurs44, and/or stress granules, sites where mRNA is stored in stalled translation initiation complexes44, in C. neoformans.

The significance of coupling mRNA synthesis and decay was supported by the contribution of RPB4 to virulence. As expected, the rpb4Δ mutant strain has a moderate growth defect when grown at 37°C and also displays attenuated virulence in a mouse model of cryptococcosis6. Our findings strongly support the paradigm that coupling mRNA synthesis and decay contributes to finely controlled intensity and duration of responses that are required for stress adaptation and virulence. It is likely that this mechanism is utilized in response to many of the environmental changes that C. neoformans encounters in the human host, however this has not yet been investigated. On the other hand, this may be a temperature-specific phenomenon that is directed by the effect of temperature on the RNA itself. In a recent study in S. cerevisiae, Wan et al. determined the melting temperatures of RNA and revealed that mRNA melting temperature correlates with the changes in mRNA expression during heat shock45 (also reviewed by Leach and Cohen 46). RNAs with the lowest melting temperatures encoded for the ribosomal proteins, which coincide with larger and prolonged decreases in abundance in response to heat shock, whereas the most stable RNAs, which have the highest melting temperatures, show little decline. The authors identified putative RNA thermometers, stable structures that undergo structural rearrangement in response to different temperatures to mediate gene expression regulation, and demonstrated that RNAs with higher melting temperatures possess these structures and are more resistant to decay. Indeed, the mRNA with the most stable structure encodes for HAC1, which regulates the ER stress response in S. cerevisiae. It is unknown if these same structures exist in C. neoformans, but it is tempting to speculate that if they do, RNA elements may be unblocked in response to temperature and may contribute to decay regulons.

Other studies have also revealed the importance of controlling mRNA stability in regulating gene expression in response to other changes in environment besides temperature. An excreted protein known as anti-phagocytic protein 1, App1, was identified in the serum of infected patients and found to prevent complement-mediated phagocytosis by macrophages47. It is suggested that escaping phagocytosis is critical for establishing the early infection in the pulmonary environment48. Given that alveolar macrophages are the first line of defense against the yeast cells, it was likely that the lung environment promotes the production of this protective protein. Further investigation revealed that a low-glucose environment, like the lung, results in upregulated expression of APP149. Intriguingly incubation in BAL, serum, and CSF, which are all relatively low glucose environments, all resulted in upregulated APP1 expression49. Interestingly, glucose deprivation not only caused increased transcription but also significantly increased stability of the APP1 transcript, ultimately resulting in increased App1 protein expression47. The factors involved in this prolonged stability are unknown. An earlier study revealed that APP1 transcription is controlled via the Ipc1-DAG-Atf2 pathway50. However, the low-glucose induced upregulation of APP1 was independent of this pathway, suggesting that APP1 induction and stability in the lung is regulated by other signaling mechanisms49.

Regulated mRNA stability has also been demonstrated to play an interesting role in mating. Bipolar mating in C. neoformans is believed to be a rare event given that the α mating type is predominantly found in both the environment as well as clinical isolates compared to its a-type mating partner51, 52. Mating is initiated by the production of pheromones that are expressed from the MAT locus from each mating partner53, 54. Park et al. discovered that MFα1, which encodes a small peptide pheromone, undergoes a continuous cycle of synthesis and decay in the vegetative state, resulting in overall low steady state levels under these conditions55. This low abundance is mediated by the DEAD-box RNA helicase, Vad1, as MFα1 accumulates in a vad1Δ mutant55. The S. cerevisiae orthologue of Vad1, Dhh1, is an accelerator of decapping and is known to associate with the Ccr4-NOT complex in S. cerevisiae56, 57. Vad1 was found to associate with the MFα1 mRNA and mediate degradation of this transcript during vegetative conditions demonstrated by increased stability in vad1Δ cells55. Not surprisingly, the vad1Δ mutant had a higher capacity to mate with MATa cells on mating medium compared to the wild type55, and it was previously discovered that Vad1 is required for virulence58. Interestingly, transfer of wild type cells to mating medium resulted in increased stability of MFα1 and increased protein product, indicating that MFα1 pheromone production is, at least in part, regulated by Vad1-mediated decay55. The authors suggest that the “futile” cycle of synthesis and decay during vegetative growth allows the cells to efficiently maintain low steady state levels while standing ready for rapid production of mating pheromone when the rare opportunity to mate arises. C. neoformans can also undergo same-sex mating, a process known as haploid or monokaryotic fruting, in which alpha cells employ a modified sexual cycle to produce spores59, 60. While pheromone production and signalling components are shared in both same-sex and opposite-sex mating59, 61, 62, it is unknown if MFα1 production is regulated by Vad1 during monokaryotic fruiting.

Unconventional Splicing

As mentioned above, the ER stress response is elicited following exposure to host temperature. This response is also activated in response to nutrient starvation, oxidative stress, and calcium imbalance, in addition to chemicals that directly cause unfolding/misfolding of proteins including DTT and tunicamycin. Studies in S. cerevisiae have unraveled an unconventional splicing event that regulates the ER stress response. A self-activating Ser/Thr kinase in the ER lumen known as Ire1 serves as the unfolded protein sensor63. This protein contains an endoribonuclease domain that, when Ire1 is activated, removes an intron from its target, HAC164. Hac1 is a transcription factor that drives the transcription of critical Unfolded Protein Response (UPR) genes65. Unspliced HAC1 mRNA in S. cerevisiae does not undergo translation due to secondary structure that forms between sequences in the 5’UTR that are complementary to the unconventional intron sequence; therefore the splicing event is critical for a proper response to ER stress66. Recently, Cheon et al. identified the Ire1 and Hac1 orthologs in C. neoformans67. While Ire1 is very well conserved, the Hac1 ortholog, Hxl1, is more divergent. This group revealed that HXL1 does undergo a splicing event in response to the ER stressor tunicamycin67. Interestingly, both spliced and unspliced HXL1 are present under unstressed conditions in C. neoformans, albeit the ratio of spliced to unspliced is greater under stress67. In addition, the intron in C. neoformans HXL1 is much shorter (56 nt) compared to the intron in HAC1 (252-nt), and it does not contain sequences complementary to its 5’UTR67. This is also true for other fungal orthologs of HAC1 as well as the mammalian ortholog. This suggests that the intron does not serve to attenuate translation. Interestingly, Cheon et al. reported that a protein product for the unspliced HXL1 could not be detected, and the spliced HXL1 protein product is only observed under stressed conditions, despite the presence of both spliced and unspliced HXL1 mRNA during unstressed conditions67. These data suggest that there is a novel mechanism tightly controlling the induction of this response, and it is likely that translational regulation or protein stability of the HXL1 products may be involved. Regardless, the unconventional splicing event seems to be critical for this process. This group also demonstrated that the splicing event is enhanced during cell wall stress, heat shock, and high salt stress although tunicamycin produced the greatest increase in the spliced:unspliced ratio67. The importance of this mechanism is highlighted in the complete attenuation of virulence by both ire1Δ and hxl1Δ mutant strains in a mouse model of disseminated cryptococcosis, suggesting that Ire1-HXL1 regulation of UPR significantly contributes to C. neoformans virulence67.

Alternative Splicing

In a study performed a decade ago, another example of stress-induced alternative splicing was reported. Differential display RT-PCR was utilized to identify genes that were upregulated in response to host temperature68. Genes of interest were identified by comparing this data to data obtained from C. neoformans cells purified from the subarachnoid space of infected rabbits69. One transcript that was upregulated in both sets of data was the cytochrome c oxidase subunit, COX1. Further investigation of this gene led to the discovery of a possible host-temperature induced alternative splicing event. Specifically, a 2.3kb polycistronic transcript, in addition to a 1.9kb transcript hybridized to a COX1 probe at 37°C68. The authors concluded that the larger transcript is a tricistronic RNA that also encodes for ATP9 and ATP8, neighboring mitochondrial genes just up and downstream of COX1, respectively, whereas the shorter dicistronic transcript encodes for COX1 and ATP8 only68. It is unknown whether the larger pre-processed transcript is transcriptionally induced and/or if host-temperature triggers a reduction in the rate of mRNA processing. Interestingly, it seems that the presence of the larger precursor is specific to serotype A strains, given that the 2.9 kb transcript is not detectable in the serotype D strain, JEC2168. However, monocistronic COX1 transcripts were not found in serotype A strain H99, but were observed in JEC21, suggesting that these mature transcripts have differing stabilities in the two backgrounds68. It was suggested that the tri-cistronic precursor may serve as a direct template for translation during host-temperature induced stress; however there is no evidence for this mechanism. The authors suggest that differences in the mitochondria may contribute to the unique pathogenic profiles of these two serotypes including the increased thermotolerance of the more virulent serotype A strains68. While a study investigating the mitochondrial genomes of these two serotypes found striking differences in the overall sizes of the genomes, number of introns (loss of introns in the serotype A strain), and the nucleotide sequences of some genes70, Toffaletti et al. utilized AD hybrid strains to demonstrate that the virulence composite of the two serotypes is predominantly controlled by the nuclear-encoded factors71. However, several studies have demonstrated the upregulation of genes important for mitochondrial function following host-temperature stress, and it is likely that oxidative phosphorylation and energy production via the mitochondria contribute to this stress response.26, 69, 72

The environmental stress response (ESR)

Work in S. cerevisiae has demonstrated that a mechanism of coordinated gene expression changes has evolved to defend cells from environmental variation. While stress-specific responses are observed, a common set of 900 genes are stereotypically affected by a variety of stresses13, 15. The 600 genes that undergo repression in response to stress generally encode for proteins that contribute to energy-demanding processes, specifically translation12-15. Repression of these genes results in decreased protein synthesis and cell-cycle and growth arrest, allowing the cell to conserve energy while it adapts to its new environment. The 300 genes that are induced by ESR belong to several functional categories including carbohydrate metabolism, fatty acid metabolism, oxidation/reduction, signaling, respiration, and protein folding/degradation15. These processes contribute to protecting the internal milieu. These two groups of genes display nearly identical but opposite changes following exposure to stress, and with the exception of starvation, these changes are transient14. The intensity of the changes provoked by stress is proportional to the magnitude of the environmental change, indicating that the ESR is dose-dependent13. The ESR has been demonstrated to provide cross-resistance to cells, a phenomenon that offers cells protection against one stress when pre-treated with a different stressor. The ESR has been shown to be conserved between S. cerevisiae and S. pombe, although the regulation of this response is clearly divergent18, 22. Studies in the pathogenic yeast, C. albicans, suggest that an ESR-like mechanism may exist, but the response is much smaller and occurs only under limited conditions19, 20.

Coupling synthesis and decay

Studies in S. cerevisiae have demonstrated that coupling of transcription and degradation contributes to regulated gene expression40, 41, 73-76. This process is mediated by the dissociable RNA polymerase II subunits Rpb4 and Rpb7, which form a heterodimer. Rpb4/7 associates with the PolII complex in close proximity to the RNA exit channel, and Rpb7 can interact with nascent RNA77-79. It has been demonstrated that during stress, Rpb4/7 co-transcriptionally associates with transcripts and travels with them to the cytoplasm41. Both Rpb4 and Rpb7 accumulate in P-bodies, sites for mRNA decay and storage, demonstrating a function in mRNA processing40, 80. While Rpb4 has been demonstrated to specifically influence the decay kinetics of ribosomal protein transcripts, Rpb7 seems to play a more general role in degradation. Whether Rpb4 and Rpb7 function without the other is unclear. Association of Rpb4/7 with the holoenzyme is required for proper mRNA degradation and regulation of genome-wide transcriptome profiles during stress, demonstrating that synthesis and decay are coupled41, 74. It is proposed that association with Rpb4/7 “imprints” mRNAs, marking them for enhanced decay by more efficient recruitment of degradation factors41. The combined effect of increased/decreased rates of transcription with modulation of the levels of imprinting can allow the cell to manipulate the overall transcriptome kinetics41. In response to specific stresses, it is suggested that the counter-action of increased synthesis with enhanced imprinting allows the cell to mount a very quick, transient response that is tightly controlled.

Conclusion

When C. neoformans enters the human host, a series of environmental changes occurs that challenges the cells to reprogram gene expression in order to protect the internal milieu and persist in the new environment. By examining gene expression profiles of cells exposed to different stresses investigators are beginning to understand how the cell responds to each stress in order to adapt. Through time-courses and carefully designed experiments, these types of analyses can allow investigators to reveal patterns and identify significant changes that occur throughout adaptation and allow maintained growth in new environments. It seems that in many cases C. neoformans undergoes transient reprogramming of the RNA pools following exposure to stress. Some of the responses to multiple stresses overlap, leading to cross-protection. These traits are reminiscent of the environmental stress response that has been demonstrated in S. cerevisiae which facilitates a rapid and efficient means to protect the cell. The response in C. neoformans, however, may be less robust and more specialized similar to the pathogenic ascomycete, C. albicans. Carefully designed time course studies that examine multiple stress responses will clarify this matter. Regulating this response as well as stress-specific responses is likely critical in the ability of C. neoformans to adapt to stress.

Several mechanisms beyond transcriptional regulation that contribute to reprogramming the RNA pools following exposure to stress have been revealed. Specifically, alternative splicing and regulated stability of transcripts have been implicated in stress adaptation. The existence of P-bodies and stress granules has been confirmed in C. neoformans, implying that mRNA localization and processing plays a role during stress. In addition, coupling of mRNA synthesis and decay has recently been demonstrated to regulate the intensity and duration of stress responses following shift to host temperature. It is likely that this mechanism is employed during other stresses as well, given that this process is driven by a dissociable subunit of the synthesis machinery, but future investigation is necessary to determine this possibility. Exploring the fate of RNAs during stress in C. neoformans has only just begun, but the current work suggests that RNA biology contributes greatly to proper cellular responses to stress, and ongoing investigation will likely contribute to overall understanding of stress adaptation and virulence of this organism.

Contributor Information

Amanda L. M. Bloom, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Witebsky Center for Microbial Pathogenesis and Immunology, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York, Buffalo, NY, USA

John C. Panepinto, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Witebsky Center for Microbial Pathogenesis and Immunology, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York, Buffalo, NY, USA

References

- 1.Cryptococcus: From Human Pathogen to Model Yeast. 2nd ed. Amer Society for Microbiology; Washington, D.C.: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Velagapudi R, Hsueh YP, Geunes-Boyer S, Wright JR, Heitman J. Spores as infectious propagules of Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 2009;77:4345–4355. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00542-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keene JD. RNA regulons: coordination of post-transcriptional events. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:533–543. doi: 10.1038/nrg2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keene JD, Lager PJ. Post-transcriptional operons and regulons co-ordinating gene expression. Chromosome Res. 2005;13:327–337. doi: 10.1007/s10577-005-0848-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keene JD, Tenenbaum SA. Eukaryotic mRNPs may represent posttranscriptional operons. Mol Cell. 2002;9:1161–1167. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00559-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloom AL, Solomons JT, Havel VE, Panepinto JC. Uncoupling of mRNA synthesis and degradation impairs adaptation to host temperature in Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol Microbiol. 2013;89:65–83. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Havel VE, Wool NK, Ayad D, Downey KM, Wilson CF, Larsen P, Djordjevic JT, Panepinto JC. Ccr4 promotes resolution of the endoplasmic reticulum stress response during host temperature adaptation in Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot Cell. 2011;10:895–901. doi: 10.1128/EC.00006-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamasaki S, Anderson P. Reprogramming mRNA translation during stress. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:222–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chow ED, Liu OW, O'Brien S, Madhani HD. Exploration of whole-genome responses of the human AIDS-associated yeast pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans var grubii: nitric oxide stress and body temperature. Curr Genet. 2007;52:137–148. doi: 10.1007/s00294-007-0147-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kraus PR, Boily MJ, Giles SS, Stajich JE, Allen A, Cox GM, Dietrich FS, Perfect JR, Heitman J. Identification of Cryptococcus neoformans temperature-regulated genes with a genomic-DNA microarray. Eukaryot Cell. 2004;3:1249–1260. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.5.1249-1260.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Upadhya R, Campbell LT, Donlin MJ, Aurora R, Lodge JK. Global transcriptome profile of Cryptococcus neoformans during exposure to hydrogen peroxide induced oxidative stress. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Causton HC, Ren B, Koh SS, Harbison CT, Kanin E, Jennings EG, Lee TI, True HL, Lander ES, Young RA. Remodeling of yeast genome expression in response to environmental changes. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:323–337. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.2.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gasch AP, Spellman PT, Kao CM, Carmel-Harel O, Eisen MB, Storz G, Botstein D, Brown PO. Genomic expression programs in the response of yeast cells to environmental changes. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:4241–4257. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.12.4241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gasch AP, Werner-Washburne M. The genomics of yeast responses to environmental stress and starvation. Funct Integr Genomics. 2002;2:181–192. doi: 10.1007/s10142-002-0058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gasch AP. The environmental stress response: a common yeast response to diverse environmental stresses. In: Hohmann S, Mager WH, editors. Yeast Stress Responses. Springer Berlin-Heidelberg; Berlin, Germany: 2003. pp. 11–70. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ko YJ, Yu YM, Kim GB, Lee GW, Maeng PJ, Kim S, Floyd A, Heitman J, Bahn YS. Remodeling of global transcription patterns of Cryptococcus neoformans genes mediated by the stress-activated HOG signaling pathways. Eukaryot Cell. 2009;8:1197–1217. doi: 10.1128/EC.00120-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maeng S, Ko YJ, Kim GB, Jung KW, Floyd A, Heitman J, Bahn YS. Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals novel roles of the Ras and cyclic AMP signaling pathways in environmental stress response and antifungal drug sensitivity in Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot Cell. 2010;9:360–378. doi: 10.1128/EC.00309-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen D, Toone WM, Mata J, Lyne R, Burns G, Kivinen K, Brazma A, Jones N, Bahler J. Global transcriptional responses of fission yeast to environmental stress. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:214–229. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-08-0499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Enjalbert B, Smith DA, Cornell MJ, Alam I, Nicholls S, Brown AJ, Quinn J. Role of the Hog1 stress-activated protein kinase in the global transcriptional response to stress in the fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:1018–1032. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-06-0501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Enjalbert B, Nantel A, Whiteway M. Stress-induced gene expression in Candida albicans: absence of a general stress response. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:1460–1467. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-08-0546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Missall TA, Pusateri ME, Donlin MJ, Chambers KT, Corbett JA, Lodge JK. Posttranslational, translational, and transcriptional responses to nitric oxide stress in Cryptococcus neoformans: implications for virulence. Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5:518–529. doi: 10.1128/EC.5.3.518-529.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gasch AP. Comparative genomics of the environmental stress response in ascomycete fungi. Yeast. 2007;24:961–976. doi: 10.1002/yea.1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Florio AR, Ferrari S, De Carolis E, Torelli R, Fadda G, Sanguinetti M, Sanglard D, Posteraro B. Genome-wide expression profiling of the response to short-term exposure to fluconazole in Cryptococcus neoformans serotype A. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:97. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gonzalez-Parraga P, Alonso-Monge R, Pla J, Arguelles JC. Adaptive tolerance to oxidative stress and the induction of antioxidant enzymatic activities in Candida albicans are independent of the Hog1 and Cap1-mediated pathways. FEMS Yeast Res. 2010;10:747–756. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2010.00654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosa e Silva LK, Staats CC, Goulart LS, Morello LG, Pelegrinelli Fungaro MH, Schrank A, Vainstein MH. Identification of novel temperature-regulated genes in the human pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans using representational difference analysis. Res Microbiol. 2008;159:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steen BR, Lian T, Zuyderduyn S, MacDonald WK, Marra M, Jones SJ, Kronstad JW. Temperature-regulated transcription in the pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans. Genome Res. 2002;12:1386–1400. doi: 10.1101/gr.80202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balagopal V, Parker R. Polysomes, P bodies and stress granules: states and fates of eukaryotic mRNAs. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:403–408. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brengues M, Teixeira D, Parker R. Movement of eukaryotic mRNAs between polysomes and cytoplasmic processing bodies. Science. 2005;310:486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1115791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parker R, Sheth U. P bodies and the control of mRNA translation and degradation. Mol Cell. 2007;25:635–646. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson P, Kedersha N. Stress granules: the Tao of RNA triage. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kozubowski L, Aboobakar EF, Cardenas ME, Heitman J. Calcineurin colocalizes with P-bodies and stress granules during thermal stress in Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot Cell. 2011;10:1396–1402. doi: 10.1128/EC.05087-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Odom A, Muir S, Lim E, Toffaletti DL, Perfect J, Heitman J. Calcineurin is required for virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. EMBO J. 1997;16:2576–2589. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cyert MS. Calcineurin signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: how yeast go crazy in response to stress. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;311:1143–1150. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01552-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lev S, Desmarini D, Chayakulkeeree M, Sorrell TC, Djordjevic JT. The Crz1/Sp1 transcription factor of Cryptococcus neoformans is activated by calcineurin and regulates cell wall integrity. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51403. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aboobakar EF, Wang X, Heitman J, Kozubowski L. The C2 domain protein Cts1 functions in the calcineurin signaling circuit during high-temperature stress responses in Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot Cell. 2011;10:1714–1723. doi: 10.1128/EC.05148-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parker R, Song H. The enzymes and control of eukaryotic mRNA turnover. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:121–127. doi: 10.1038/nsmb724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cao D, Parker R. Computational modeling of eukaryotic mRNA turnover. RNA. 2001;7:1192–1212. doi: 10.1017/s1355838201010330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Panepinto JC, Komperda KW, Hacham M, Shin S, Liu X, Williamson PR. Binding of serum mannan binding lectin to a cell integrity-defective Cryptococcus neoformans ccr4Delta mutant. Infect Immun. 2007;75:4769–4779. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00536-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herruer MH, Mager WH, Raue HA, Vreken P, Wilms E, Planta RJ. Mild temperature shock affects transcription of yeast ribosomal protein genes as well as the stability of their mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:7917–7929. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.16.7917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lotan R, Bar-On VG, Harel-Sharvit L, Duek L, Melamed D, Choder M. The RNA polymerase II subunit Rpb4p mediates decay of a specific class of mRNAs. Genes Dev. 2005;19:3004–3016. doi: 10.1101/gad.353205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shalem O, Groisman B, Choder M, Dahan O, Pilpel Y. Transcriptome kinetics is governed by a genome-wide coupling of mRNA production and degradation: a role for RNA Pol II. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goldstrohm AC, Seay DJ, Hook BA, Wickens M. PUF protein-mediated deadenylation is catalyzed by Ccr4p. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:109–114. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609413200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goldstrohm AC, Hook BA, Seay DJ, Wickens M. PUF proteins bind Pop2p to regulate messenger RNAs. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:533–539. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buchan JR, Nissan T, Parker R. Analyzing P-bodies and stress granules in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Enzymol. 2010;470:619–640. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)70025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wan Y, Qu K, Ouyang Z, Kertesz M, Li J, Tibshirani R, Makino DL, Nutter RC, Segal E, Chang HY. Genome-wide measurement of RNA folding energies. Mol Cell. 2012;48:169–181. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leach MD, Cowen LE. Surviving the heat of the moment: a fungal pathogens perspective. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003163. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luberto C, Martinez-Marino B, Taraskiewicz D, Bolanos B, Chitano P, Toffaletti DL, Cox GM, Perfect JR, Hannun YA, Balish E, et al. Identification of App1 as a regulator of phagocytosis and virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1080–1094. doi: 10.1172/JCI18309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Okagaki LH, Nielsen K. Titan cells confer protection from phagocytosis in Cryptococcus neoformans infections. Eukaryot Cell. 2012;11:820–826. doi: 10.1128/EC.00121-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams V, Del Poeta M. Role of glucose in the expression of Cryptococcus neoformans antiphagocytic protein 1, App1. Eukaryot Cell. 2011;10:293–301. doi: 10.1128/EC.00252-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mare L, Iatta R, Montagna MT, Luberto C, Del Poeta M. APP1 transcription is regulated by inositol-phosphorylceramide synthase 1-diacylglycerol pathway and is controlled by ATF2 transcription factor in Cryptococcus neoformans. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:36055–36064. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507285200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kwon-Chung KJ, Bennett JE. Distribution of alpha and alpha mating types of Cryptococcus neoformans among natural and clinical isolates. Am J Epidemiol. 1978;108:337–340. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Halliday CL, Bui T, Krockenberger M, Malik R, Ellis DH, Carter DA. Presence of alpha and a mating types in environmental and clinical collections of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii strains from Australia. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2920–2926. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.9.2920-2926.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Davidson RC, Moore TD, Odom AR, Heitman J. Characterization of the MFalpha pheromone of the human fungal pathogen cryptococcus neoformans. Mol Microbiol. 2000;38:1017–1026. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shen WC, Davidson RC, Cox GM, Heitman J. Pheromones stimulate mating and differentiation via paracrine and autocrine signaling in Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot Cell. 2002;1:366–377. doi: 10.1128/EC.1.3.366-377.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park YD, Panepinto J, Shin S, Larsen P, Giles S, Williamson PR. Mating pheromone in Cryptococcus neoformans is regulated by a transcriptional/degradative “futile” cycle. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:34746–34756. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.136812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hata H, Mitsui H, Liu H, Bai Y, Denis CL, Shimizu Y, Sakai A. Dhh1p, a putative RNA helicase, associates with the general transcription factors Pop2p and Ccr4p from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1998;148:571–579. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.2.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maillet L, Collart MA. Interaction between Not1p, a component of the Ccr4-not complex, a global regulator of transcription, and Dhh1p, a putative RNA helicase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:2835–2842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107979200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Panepinto J, Liu L, Ramos J, Zhu X, Valyi-Nagy T, Eksi S, Fu J, Jaffe HA, Wickes B, Williamson PR. The DEAD-box RNA helicase Vad1 regulates multiple virulence-associated genes in Cryptococcus neoformans. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:632–641. doi: 10.1172/JCI200523048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lin X, Hull CM, Heitman J. Sexual reproduction between partners of the same mating type in Cryptococcus neoformans. Nature. 2005;434:1017–1021. doi: 10.1038/nature03448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wickes BL, Mayorga ME, Edman U, Edman JC. Dimorphism and haploid fruiting in Cryptococcus neoformans: association with the alpha-mating type. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:7327–7331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fu J, Mares C, Lizcano A, Liu Y, Wickes BL. Insertional mutagenesis combined with an inducible filamentation phenotype reveals a conserved STE50 homologue in Cryptococcus neoformans that is required for monokaryotic fruiting and sexual reproduction. Mol Microbiol. 2011;79:990–1007. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang P, Perfect JR, Heitman J. The G-protein beta subunit GPB1 is required for mating and haploid fruiting in Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:352–362. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.1.352-362.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shamu CE, Walter P. Oligomerization and phosphorylation of the Ire1p kinase during intracellular signaling from the endoplasmic reticulum to the nucleus. EMBO J. 1996;15:3028–3039. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sidrauski C, Walter P. The transmembrane kinase Ire1p is a site-specific endonuclease that initiates mRNA splicing in the unfolded protein response. Cell. 1997;90:1031–1039. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80369-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cox JS, Walter P. A novel mechanism for regulating activity of a transcription factor that controls the unfolded protein response. Cell. 1996;87:391–404. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81360-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ruegsegger U, Leber JH, Walter P. Block of HAC1 mRNA translation by long-range base pairing is released by cytoplasmic splicing upon induction of the unfolded protein response. Cell. 2001;107:103–114. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00505-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cheon SA, Jung KW, Chen YL, Heitman J, Bahn YS, Kang HA. Unique evolution of the UPR pathway with a novel bZIP transcription factor, Hxl1, for controlling pathogenicity of Cryptococcus neoformans. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002177. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Toffaletti DL, Del Poeta M, Rude TH, Dietrich F, Perfect JR. Regulation of cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (COX1) expression in Cryptococcus neoformans by temperature and host environment. Microbiology. 2003;149:1041–1049. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Steen BR, Zuyderduyn S, Toffaletti DL, Marra M, Jones SJ, Perfect JR, Kronstad J. Cryptococcus neoformans gene expression during experimental cryptococcal meningitis. Eukaryot Cell. 2003;2:1336–1349. doi: 10.1128/EC.2.6.1336-1349.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Litter J, Keszthelyi A, Hamari Z, Pfeiffer I, Kucsera J. Differences in mitochondrial genome organization of Cryptococcus neoformans strains. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2005;88:249–255. doi: 10.1007/s10482-005-8544-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Toffaletti DL, Nielsen K, Dietrich F, Heitman J, Perfect JR. Cryptococcus neoformans mitochondrial genomes from serotype A and D strains do not influence virulence. Curr Genet. 2004;46:193–204. doi: 10.1007/s00294-004-0521-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Akhter S, McDade HC, Gorlach JM, Heinrich G, Cox GM, Perfect JR. Role of alternative oxidase gene in pathogenesis of Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 2003;71:5794–5802. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.10.5794-5802.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dori-Bachash M, Shema E, Tirosh I. Coupled evolution of transcription and mRNA degradation. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Goler-Baron V, Selitrennik M, Barkai O, Haimovich G, Lotan R, Choder M. Transcription in the nucleus and mRNA decay in the cytoplasm are coupled processes. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2022–2027. doi: 10.1101/gad.473608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Haimovich G, Choder M, Singer RH, Trcek T. The fate of the messenger is pre-determined: a new model for regulation of gene expression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1829:643–653. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Harel-Sharvit L, Eldad N, Haimovich G, Barkai O, Duek L, Choder M. RNA polymerase II subunits link transcription and mRNA decay to translation. Cell. 2010;143:552–563. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Meka H, Werner F, Cordell SC, Onesti S, Brick P. Crystal structure and RNA binding of the Rpb4/Rpb7 subunits of human RNA polymerase II. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:6435–6444. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Orlicky SM, Tran PT, Sayre MH, Edwards AM. Dissociable Rpb4-Rpb7 subassembly of rna polymerase II binds to single-strand nucleic acid and mediates a post-recruitment step in transcription initiation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10097–10102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003165200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ujvari A, Luse DS. RNA emerging from the active site of RNA polymerase II interacts with the Rpb7 subunit. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:49–54. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lotan R, Goler-Baron V, Duek L, Haimovich G, Choder M. The Rpb7p subunit of yeast RNA polymerase II plays roles in the two major cytoplasmic mRNA decay mechanisms. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:1133–1143. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200701165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]