Abstract

The impact of vaccines on public health and well-being has been profound. Smallpox has been eradicated, polio is nearing eradication, and multiple diseases have been eliminated from certain areas of the world. Unfortunately, we now face diseases such as: hepatitis C, malaria, or tuberculosis, as well as new and re-emerging pathogens for which lack effective vaccines. Empirical approaches to vaccine development have been successful in the past, but may not be up to the current infectious disease challenges facing us. New, directed approaches to vaccine design, development, and testing need to be developed. Ideally these approaches will capitalize on cutting-edge technologies, advanced analytical and modeling strategies, and up-to-date knowledge of both pathogen and host. These approaches will pay particular attention to the causes of inter-individual variation in vaccine response in order to develop new vaccines tailored to the unique needs of individuals and communities within the population.

Keywords: vaccines, personalized vaccinology, vaccinomics, systems biology, systems vaccinology, immunogenetics, microbiome

Introduction

Vaccination represents one of medicine’s greatest achievements. Vaccines have systematically reduced mortality and morbidity rates from infectious diseases and have saved countless lives. One of the first vaccines developed was the smallpox vaccine, initially based on cowpox virus, in 1796 by Edward Jenner. The use of this vaccine world-wide led to the World Health Organization’s eradication campaign in 1967.[1] The last naturally occurring case of smallpox was seen in 1977, and by 1980 the disease was declared eradicated. The development, licensure, and use of inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) in the 1950s led to an 86% decrease in polio cases. [2] This was followed by the development and use of oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV) in the 1960s with further reductions in the incidence rate of the disease. Together, these vaccines have prevented millions of cases of polio and its associated crippling effects. The phenomenal success of these vaccines led the WHO to adopt the goal of global polio eradication. Polio rates have decreased by 99% since the eradication efforts started with only a few hundred cases per year, mostly in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nigeria, and neighboring countries.[3] Unfortunately, 39 previously polio-free countries have experienced outbreaks due to imported cases, making continued vaccination programs essential to the final eradication efforts. In 2000, concerns over the safety of oral poliovirus vaccines shifted vaccine usage to IPV.

The use of vaccines has not been entirely positive. RotaShield, a rotavirus vaccine developed by Wyeth, was licensed in 1988, however; a little more than one year later, Wyeth removed RotaShield from the market and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) withdrew their recommendation for its use due to an increased risk of intussusception, a rare life-threatening intestinal disorder (1 in 5,000 children vaccinated).[4] Over the next several years, additional formulations would be licensed; RotaTeq by Merck in 2006 and Rotarix by GlaxoSmithKlein in 2008. Importantly, these new products were only licensed after large-scale trials specifically evaluating the risk of intussusception.

The purpose of a vaccine is to provoke a beneficial immune response from the recipient. The vast majority of the time, this response results in protective immunity accompanied by temporary discomfort. However, each vaccine product (much like all medicines and medical procedures) can have side effects. Although typically minor and temporary, some side effects can be serious and life-threatening. In a very real way, vaccines are a victim of their own success. Initially, the substantial risks from the disease far outweigh the minimal risks associated with the vaccine. As vaccination rates rise, disease incidence falls, thereby changing the risk/reward balance. In many cases, it is the public perception of the risk/reward balance that changes rather than the actual risk/reward balance. Polio, measles, mumps, pertussis, and many other diseases may be considered: too rare for concern; historical diseases that no longer affect people; diseases that only occur in distant regions of the world; or diseases that are simply too minor to worry about. To the general public, the perceived risk from these diseases is minimal, while vaccine-related side effects (real or imagined) are hyped by the media. In reality, these disease are serious public health threats: measles has a mortality rate of 1–2 per 1,000 cases, pertussis has a mortality rate of 1–2%, and diphtheria fatality rates are 5–10% overall and up to 20% in younger children.[2] Many regions of the world have been experiencing a significant increase in measles outbreaks in the last several years. In 2012 there were 29,150 cases of measles and 29,354 cases of rubella in Europe alone, and data from early in 2013 indicate that these numbers are likely to increase.[5] These outbreaks are a direct result of decreased vaccine coverage,[6] caused in large part, by unwarranted fears concerning measles vaccine and autism. Justified or not, we currently live in a society with a heightened concern regarding vaccine safety. This has led to removal of thimerosal from vaccine formulations, as well as adjustments in vaccination schedules, and has also raised the bar on clinical trial and safety data required for licensure. Prediction of adverse events and side effects due to vaccination is now becoming an important process of vaccine development.

Until recently, vaccine development has followed a one-size-fits-all approach characterized by empirical methods that can be described as an isolate, inactive/attenuate, inject paradigm. This is a straightforward approach that has been remarkably successful in the past. Unfortunately, we are reaching the point of diminishing returns, especially for complex pathogens. This approach also ignores our increased understanding of both innate and adaptive immune responses, variations in host genetics, the effect of age, gender, race/ethnicity, microbiome, or even diet and nutrition. It also overlooks host-pathogen interactions, overemphasizes humoral immune responses, and has dealt with variation in pathogen genetics by creating different products for different strains (polio and pneumococcal vaccines) or yearly reformulations (influenza vaccine). The ultimate goal of the vaccine research community is to develop safer and more effective vaccines to enhance public health. This review will focus on current technologies and scientific advances in vaccine research and their application to predicting vaccine-induced immune responses. These include: 1) The role of innate immune responses in the establishment of adaptive immunity, and the use of adjuvants to enhance immunity; 2) The effect of the microbiome on immune responses; 3) The influence of host genetic variation on vaccine response; and 4) The role of systems biology approaches in understanding and predicting immunity to vaccines.

Vaccinomics and Personalized Vaccinology

It is likely that the development of effective vaccines to counter these current public health threats will require a new approach to vaccinology. We have called this new approach “vaccinomics”, an approach informed by a detailed understanding of the critical components of effective immune responses at both the mechanistic and systems levels (Figure 1).[7–12] An essential element of this new approach will be the recognition that vaccine recipients represent a widely diverse population, a population that responds to a given vaccine with a wide spectrum of immune responses. Men and women exhibit differences in immune responses after vaccination and/or infection, a phenomenon that has been seen with multiple viruses (rhinoviruses, CMV, dengue, EBV, HBV, HCV, influenza, measles, WNV) [13–16] and is mediated, in part, by hormonal differences.[17,18] The idea that a diverse population, with varied responses to immunization, might require different vaccines for optimal protection has been termed personalized vaccinology. Much like personalized medicine has impacted the fields of pharmacology and cancer, we are beginning to see a move toward “personalized vaccinology,” with influenza vaccines being an excellent example. For the 2013–2014 influenza season there are five different types of vaccines available, each geared toward a specific segment of the population (Table 1). We have influenza vaccines containing antigens from three or four viral strains; we have multiple formulations of the standard dose, inactivated, vaccine each with its own age range; we recommend two doses for infants and children who have never received influenza vaccine; we have a high dose vaccine intended to overcome immunosenescence in older and elderly individuals; we have a recombinant formulation produced in insect cells for those with allergies to eggs and egg proteins; we have a product containing a live attenuated virus, thought to better mimic a real infection; and we have a low dose, intradermal vaccine that delivers the antigen to skin-resident APCs and is being marketed as being antigen sparing and having a needle 90% smaller than other flu shots. There are undoubtedly market forces, such as profit motives, contributing to the increased product line. We would argue that new products that meet the needs of population groups (those with egg-based allergies or the elderly to name a few) will be more successful. It is therefore in the long-term interest of vaccine manufacturers to develop new vaccines that successfully address the limitations of current vaccines.

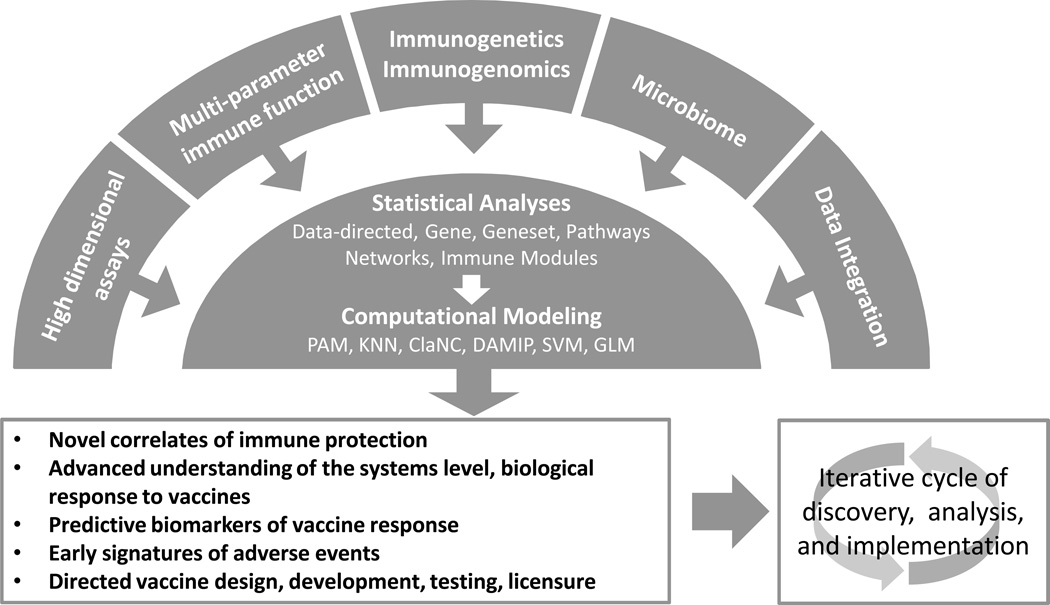

Figure 1. Vaccinomics and Predictive Vaccinology.

Vaccinomics incorporates: 1) the use of omics-level technologies, from genome to proteome, to metabolome; 2) appropriate measures of innate and adaptive immune function; and 3) information regarding host genetics/genomics, host-pathogen interactions, and host microbiome. These data are integrated and analyzed at multiple levels (unsupervised, data-driven analyses, individual parameter analyses, and pathway/network/module/geneset analyses incorporating known biologic function). The analyses are followed by computational and predictive modeling strategies (Prediction Analysis for Microarrays, K-Nearest Neighbor, Classification to Nearest Centroids, Support Vector Machines, Discriminant Analysis via Mixed Integer Programming, Generalized Linear Model) that allow investigators to predict immunogenicity and/or vaccine efficacy. Results from these studies inform vaccine development and clinical trials. Results from the clinical trials lead to new products and form the foundation for the next cycle of scientific discovery.

Table 1.

U.S. Licensed Influenza Vaccines as an Example of Personalized Vaccinology

| Vaccine Type | Route | Dose (per strain) | Age | Targeted Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trivalent, Inactivated, Influenza Vaccine. Standard dose. | I.M. | 15ug HA | 6–35 mos. >3 yrs. | Normal population |

| Trivalent, Inactivated, Influenza Vaccine. | I.D. Microneedle | 9ug HA | 18 – 64 yrs. | Individuals averse to needles |

| Trivalent, Inactivated, Influenza Vaccine. High dose. | I.M. | 180ug HA | ≥ 65 yrs. | Elderly |

| Quadravalent, Inactivated, Influenza Vaccine. | I.M. | 15ug HA | 6–35 mos. >3 yrs. | Normal population |

| Recombinant, Trivalent, Influenza Vaccine | I.M. | 45ug HA | 18 – 49 yrs. | Those with egg allergies |

| Quadravalent, Live- attenuated Influenza Vaccine | I.N. | 106.5–7.5 FFU | 2 – 49 yrs. | Healthy individuals Without immunosuppression |

Abbreviations: I.M. intramuscular; I.D. intradermal; I.N. intranasal; HA hemagluttinin; FFU fluorescent focus units.

Given the increased emphasis on personalized medicine, it is likely that the trend that we now see with influenza vaccines will expand to other vaccines as well. A critical element of this personalized vaccinology, as well as new, directed vaccine development approaches is the ability to predict vaccine response.

In summary, the use of systems-level analyses to better understand immune responses they offer the promise of: an informed approach to new vaccine development, an appreciation of the effect of genetic and non-genetic influences on immune responses; the development of novel biomarkers of vaccine response; and the creation of predictive models allowing us to select appropriate vaccine products, identify and avoid adverse responses, thereby creating safer, yet still effective vaccines against current and future public health threats.

Innate immunity and vaccine response

The past decade has seen a dramatic increase in studies focused on innate immunity. Innate immunity represents a key element in host immune response to infection and vaccination. Importantly, innate responses perform three key functions: 1) immediate recognition of pathogens; 2) non-specific defense mechanisms to halt infectious processes; and 3) initiation of powerful, antigen-specific adaptive immune responses. Stimulation of innate immunity starts with a repertoire of innate sensors such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs), RIG-I-like receptors (RIG-I/DDX5, MDA-5/IFIH1), cytosolic DNA sensors and others that recognize different pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), including: lipopolysaccharides (LPS), lipoproteins, lipopeptides, lipoarabinomannan; bacterial flagellins and viral glycoproteins; double-stranded RNA of viruses; unmethylated CpG sites of bacterial and viral DNA; as well as other RNA and DNA molecules [19–38]. Of the 10 human TLRs, 3, 7, 8 and 9 are endosomal and specialize in viral recognition and antiviral host response.

Upon viral infection, engagement of pathogen recognition receptors triggers intracellular signaling cascades leading to the activation of a wide variety of defensive mechanisms. These include: cytokine and/or chemokine secretion; upregulation of cytokine receptors; induction of s type I and III interferon (IFNα/β, IFNλ1, IFNλ2, IFNλ3); and production of antiviral effector proteins and activation of host defense pathways (e.g., dsRNA-activated protein kinase R, the 2′-5′-oligoadenylate-synthetase - ribonuclease L pathway, Mx protein, adenosine deaminase RNA-specific 1, the ISG15 ubiquitin-like pathway, etc.).[39–43] Multiple cytokines and chemokines are also produced in response to pathogen recognition.[33,34,44–49] Collectively, these defense mechanisms limit replication and spread of the pathogen within the host.

The third important function of innate immunity is to aid the priming and development of adaptive immunity that specifically eliminates the pathogen and/or pathogen-infected cells. Many of the same effector mechanisms also affect antigen presenting cells, resulting in the upregulation of costimulatory molecules, enhanced expression of MHC I and II molecules, increased phagocytosis, altered antigen processing and presentation machinery, activation and maturation of dendritic cells and other APCs. They also drive alterations in cellular trafficking patterns, which collectively bring APCs and lymphocytes together in order to more effectively initiate activation and clonal expansion of pathogen-specific lymphocyte populations. Still other factors provide costimulation, or serve as growth and differentiation factors to antigen-specific T and B lymphocytes.

Adjuvants are compounds that improve vaccine efficacy. Until recently, aluminum salts were the only adjuvant used in vaccine formulations in the U.S. As our knowledge of how the innate immune system recognizes and responds to pathogens has increased, so too has our ability to control and direct both innate and adaptive immune responses through the use of novel adjuvants. Adjuvants boost immune responses through a variety of mechanisms such as immunomodulation, cytokine upregulation, depot generation, targeting of antigen to appropriate APCs, enhanced antigen presentation, or combinations of the above effects. Currently, MF59 and AS03 (oil-in-water emulsions), ASO4 (Alum absorbed TLR4 agonist), and virosomes are used in commercial vaccine products.[50–53] Furthermore, a wide variety of vaccine adjuvants has been tested in humans with promising results. These include: TLR agonists such as CpG derivatives, Imidazoquinolines, PolyI:C, Pam3Cys, Flagellin; oil-in-water or water-in-oil emulsions such as mineral oil, squalene, copolymers; liposomes; nano-particles, ISOCMs; calcium salts, proteasomes/virosomes; muramyl dipeptide derivatives; saponins; Lipid A; bacterial toxins; and cytokines.[50,51,54] Continuing our influenza vaccine analogy, multiple adjuvants have been successfully tested in clinical trials in combination with influenza vaccines, and are of special interest for development of improved (i.e. greater immune response, antigen sparing, cross-reactive immunity) vaccines [55–59].

These examples illustrate how one can apply current insights into both innate immunology and adjuvant mechanisms of action in order to optimize vaccine development through the judicious selection of adjuvants. In particular, one can take a successful vaccine formulation and combine it with several different adjuvants that are uniquely tailored to individual groups within a population. One might target a strong adjuvant formulation for the elderly in order to overcome immunosenescence; alternatively, one might utilize a Th1 promoting adjuvant for pregnant women predisposed to Th2 responses, or for vaccines targeting pathogens (HCV, HIV) requiring strong cellular immune responses; likewise, immunocompromised individuals requiring inactivated or subunit vaccines may benefit from adjuvanted versions that safely and effectively replace the “danger signals” present in live virus vaccines; similarly, vaccines targeting respiratory pathogens may benefit from adjuvants promoting mucosal immunity.

The benefits of understanding innate responses go beyond adjuvant selection and have implications for vaccine safety as well. As adjuvant use increases, we must carefully monitor potential side effects of these adjuvants. This testing will be facilitated by detailed knowledge regarding the mechanism(s) of action, pathway(s) stimulated by each compound, and the downstream immunologic consequences of stimulating those specific pathways. In turn, this knowledge allows us to establish relevant biomarkers to quickly and carefully assess an individual’s response to the compound and, if necessary, treat potential complications quickly.[60–62] For example, one study examining early gene expression events after vaccination noted the upregulation of IFN-inducible genes was correlated with systemic adverse events, potentially creating a biomarker predicting reactogenicity.[63] If strong, early IFN responses precede damaging inflammatory reactions, one can manage those side effects, or even engineer a vaccine that that avoids over-activation of those inflammatory responses.

To assess the potential of innate immunity markers to characterize and/or predict vaccine-induced adaptive immunity and/or adverse events, the current experimental approaches are moving from single biomarker experiments and focused assays to high throughput “omics”-based assays. The latter include whole genome and transcriptome sequencing (next generation sequencing), genomic and proteomic microarrays, mass spectrometry-based proteomics, multiplexed cytokine/chemokine assays, polychromic flow cytometry, high-content assays for ligand activation/suppression of innate receptors and functional characterization of innate immune signaling cascades, high throughput assays for adjuvant activity and function screening etc. The high dimensional technologies typically produce immense amounts of data that requires sophisticated computational, bioinformatics and statistical analytical approaches, but provide systems level information that best reflects the innate-adaptive immune interface.

To summarize, as our understanding of innate immunity and adjuvant activity increases, we will be able to apply this knowledge to the judicious selection of adjuvants in order to control vaccine induced immune responses. The resulting vaccines can be tailored to various population groups: pregnant women; infants and toddlers; the elderly; the immunocompromised; individuals with chronic diseases; and patients with confounding complications (pre-existing diseases, poor diet and nutrition). As innate immunity is the first line of defense, careful monitoring of these initial events, whether at the gene or protein level, will provide early biomarkers allowing us to predict immune outcome, adverse events, disease severity, or even response to therapy. [64]

The microbiome and vaccine response

With up to 100 trillion microbial occupants, it is easy to appreciate the contributing role the microbiome plays on our health and disease [65]. The human microbiome is as unique to a person as blood type and HLA class, and there are high levels of site-specific diversity within an individual [66]. A symbiotic relationship exists between host and commensal bacteria, which is influenced by genetics, diet, and other environmental factors.[67] A disruption in this relationship, or dysbiosis, can lead to a state of disease. Culture-independent, high-throughput sequencing of non-gut microbial environments has revealed distinct microbiome profiles associated with diseases such as cystic fibrosis, chronic rhinosinusitis, tuberculosis, periodontal, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [68–72]. The coevolution of vertebrate species and their microbial residents is thought to have occurred through beneficial metabolic processing of dietary nutrients [73]. In response, the immune system has developed to accommodate the complex relationship between commensal microbes and to prevent invasion and infection by potential pathogens along tissue/microbial barriers [74]. The composition of our microbiome is shaped and manipulated through the release of specific anti-microbial compounds that prevent growth of certain microbes and allow others to flourish [75–77]. The systemic spread of invading microbes is inhibited through the release of secretory IgA through the epithelial barrier, phagocytosis by compartmentalized immune cells, and delivery to mesenteric lymphoid tissue, which is not considered to be connected to the systemic secondary lymph organs [78].

In parallel to the immune systems influence on the microbiome is a robust immune response that relies heavily on the resident microbial environment. This influence is significantly evident with lymphoid organ development in germ-free animals. Gut associated lymphoid tissue, mesenteric lymph nodes, Peyer’s patches, and lymphoid follicles are absent or diminished in size in mice lacking inherent microbiota [74,79,80]. The microbiota plays a crucial role in the development and expansion of T and B cells [81,82]. In the context of microbial infection, evidence suggests that the host microbiome is essential to the induction of immunity. In a mouse model of infection, Ichinohe et al. demonstrated that the host microbiome is crucial for the development of an adaptive response to infection with influenza A virus [83]. Commensal-derived signals are thought to contribute to the antiviral response and dampen disease severity after influenza infection [84]. These examples demonstrate that the amplitude of innate and adaptive immune responses to infection is dependent on interactions with microbial residents.

Personalized medicine-based therapies have already tailored the microbiome environment for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. For example, a fecal transplant from a healthy donor is an effective and promising treatment for recurrent Clostridium difficile infections [85]. This approach is also being used to treat inflammatory bowel disease, colitis, insulin resistance, and even multiple sclerosis [86].With the strong evidence that the host microbiome influences immunological responses, the next logical step is to investigate the influence of the microbiome on vaccine-induced immunity. For example, if a specific microbial community is associated with a robust response to vaccine, then perhaps, research can focus on potential adjuvants derived from the microbial community. Studies have begun to characterize the lung microbiome after influenza infection [87,88]. Insight into the relationship between the commensal and pathogenic microbes present after influenza infection may help in the synthesis of novel vaccine and therapeutics against influenza. Influenza virus is known to alter and facilitate the growth dynamics of certain bacterial species, such as Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus [89,90]. These species are the major etiological contributors of secondary pneumonia after influenza infection. In the future, a personalized vaccine may be targeted at influenza and at those bacterial species known to have an increased growth potential after infection. Oral vaccination may also be an avenue for personalized medicine targeted toward microbiome components, because of the route of administration and the subsequent interaction with mucosal microbiota.

In summary, we are just beginning to understand the complex relationship between our microbial cohabitants and immunity. Personalized medicine, and vaccinology, has focused on our individual genetic makeup with a significant amount of success. With advances in affordable next-generation sequencing platforms, like the Illimuna® MiSeq Desktop Sequencer, we may be able to develop a unique “fingerprint” of an individual’s microbiome in a clinical setting that could inform the administration of a personalized vaccine based on microbial composition

Immunogenetics and vaccine response

While it is well appreciated that host genetic factors influence host susceptibility to infectious diseases, it is not as well known that genetic factors similarly affect immune responses to vaccines.[11,91] A truly personalized vaccinology approach will take these important factors into consideration.

Two decades of using recombinant hepatitis B vaccine (HBV) have demonstrated significant inter-individual differences in vaccine-induced immunity and genetic factors affecting hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) specific immune responses [92,93]. Several HLA markers (individual alleles and extended haplotypes) and genetic polymorphisms in the cytokine (IL2, IL6, IL10, IL12B, TNF), cytokine receptor (IL4R), complement (C4A), and other immune response genes have been associated with non-responder and responder phenotypes after HBV vaccination. This suggests a genetic driver for differences in immune responses to HBV [92,94–98].

Our laboratory has published intensively on the topic of vaccine immunogenetics [91] and its critical role in new vaccine development [9,12,99], as well as multiple studies on viral vaccine immunogenicity [100–102]. These studies have demonstrated that immune response gene polymorphisms explain, in part, variations in vaccine-induced adaptive immune response. This work has progressed from candidate gene association studies to genome-wide association studies (GWAS), to next-generation transcriptomics examining gene sets and functional pathways to systems level studies. Using these approaches we have explained approximately 30% of the inter-individual variation in immune responses to measles vaccine.

It is possible to study the potential influence of any number of genes on vaccine response. In fact, our earlier work selected genes, based on the published literature and biologic plausibility, that were highly likely to be involved in controlling vaccine immunity. Data from our studies of measles, rubella, mumps, influenza, and vaccinia viral vaccines demonstrate that viral receptor, HLA, cytokine/chemokine, cytokine/chemokine receptor, Toll-like receptor, vitamin A and D receptor, TRIM, and other key immune response gene polymorphisms significantly influence adaptive immune responses following vaccination [103–111] [112]. Also, research across multiple viral vaccine models (measles and rubella) demonstrates that genetic influences on vaccine responses are multigenic [11,113,114]. As an example, a search for the single nucleotide polymorphisms, frequently called SNPs, that contributed to the variation in rubella vaccine-induced antibody levels identified a total of 29 SNPs in 23 genes controlling immune function that were jointly associated with variation in rubella antibody level, while only four SNPs in three candidate genes were implicated when SNPs were examined individually. Among these genes are cytokines, cytokine receptors, lymphotoxin alpha (LTA), leukocyte specific transcript-1 (LST1), antiviral effectors (OAS2, ADAR), IFN-type I-induced (EIF2AK2), vitamin A receptor family (RARB), the innate antiviral factors (TRIM5, TRIM22), and others [113]. Thus, population-based vaccine studies can identify significant polymorphisms of interest [11,103,104,115,116] In addition, genetic variation in innate antiviral genes has been previously linked to host susceptibility to viral infection (West Nile Virus, hepatitis C virus, hepatitis B virus and severe acute respiratory syndrome/SARS coronavirus) and response to interferon therapy.[103,104,116–124] These SNPs that could potentially alter expression and/or function of their corresponding proteins and subsequent functional pathways, were associated with variations in the adaptive immune response to viral vaccines.

To further examine the impact of genetic polymorphisms on immune response heterogeneity, several groups have also conducted GWAS studies to examine, in an unbiased manner, the influence of genetic polymorphisms on innate and adaptive immune responses to vaccination.[111,125–131] In these studies, we and others have found polymorphisms in both known and novel genes with no previously identified immune function to be associated with significant inter-individual variations in immune responses. Validation studies, as well as studies revealing the molecular mechanisms of identified causal genes and SNPs, are a necessary next step.

Influenza serves as an excellent example of the contributions of immunogenetics to understanding disease and improving vaccines. Influenza vaccines offer incomplete protection against infection and complications due to influenza diseases (with 10% to 50% failure rates). It was recently observed that multiple clusters of highly pathogenic avian influenza A/H5N1 infection have occurred among genetically related individuals, but not among others having equally close contact with the same ill index case in the home.[132,133] Other reports have indicated that host genetics can influence susceptibility to severe influenza (seasonal and pandemic) and death [134,135], strongly suggesting that genetic associations affect the immune response to this viral infection.

There are limited data from genetic studies regarding the influence of gene polymorphisms (including HLA) on influenza vaccine immune responses. While early reports suggested that class I HLA alleles might influence immune response to influenza A antigens, these findings have yet to be replicated or confirmed [136–138]. Other reports have identified several HLA class II loci associated with failure to mount neutralizing antibody responses (DRB1*0701 and DQB1*0303)[139,140] and other HLA class II loci associated with seroprotective (HAI titers of ≥40) responses (DRB1*04:01 and DPB1*0401). [141] Given the role of HLA in molecules in antigen presentation to T cells, further examination of the impact of HLA polymorphisms on immune response to influenza vaccination is necessary. In addition to HLA, other genes such as FCGR2A, C1QBP, and RPAIN have also been shown to affect host immune responses to the A/H1N1 influenza virus and/or replication of the influenza virus [142]. Studies like these could aid in developing the next generation of influenza vaccines by helping us to understand genetic drivers of immune response and genetic restrictions to immunity after vaccination [134,135,143].

Systems biology and predicting vaccine response

It is increasingly apparent that complex biologic processes such as immune responses are far more than the sum of their individual parts. Recently, there has a been a shift in emphasis toward studies designed to more comprehensively characterize immune function in order to visualize and understand not just the individual components of the immune response but also the multifaceted interactions between these components and to examine the temporal changes that occur during a developing immune response. Systems biology has been defined as an interdisciplinary approach that combines multiple important elements: 1) high dimensional datasets spanning various biological ‘spaces’ (genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, lipidomics, the microbiome); 2) immunologic and clinical outcomes; 3) multiple time-points to assess temporal changes in order to understand the big picture; 4) integration of the data; 5) computational modeling and analyses; and 6) development of rules governing the system in order to predict outcomes.[144–149]

Access to large quantities of data from the experimental system being studied is key to systems biology. High throughput, or “omic” level technologies such as mass spectrometry, next generation sequencing, antibody and pathogen proteome microarrays allow investigators to comprehensively assess biological systems (e.g. genome, transcriptome, proteome). In fact, we are quickly moving past the genomic era and studies focused on the proteome, metabolome, epigenome, and other ‘omes’ are becoming increasingly important and have greatly enriched our knowledge of biology.[150–153] These high dimensional results, when combined with multi-parameter assessments of immune function that capture both humoral and cellular outcomes, provide a rich dataset from which a systems level understanding can be obtained. Excellent examples of the high dimensional immune phenotyping are polychromatic flow cytometry and mass spectrometry, which allow researchers to simultaneously probe immune function in multiple cellular subsets. [154–159] Software systems and alogrithms are being developed that allow researchers to handle the immense amount of data that these new technologies produce. These bioinformatics and computation tools allow users to integrate and interrogate the datasets in order to observe correlations, to understand interaction networks, and to identify molecular and/or transcriptomic signatures. [160–162] One issue with monitoring human immune function is that while blood is the most readily accessible biological specimen, most of the immune response develops in the lymph nodes and site of infection or vaccination. Fagerberg et al. have integrated protein expression data from multiple tissue and cell types with transcriptomic analysis in order to create an updated Human Protein Atlas, which will facilitate both in-depth studies of specific tissues, genes, and/or proteins and large scale, systems biology studies. [163] Other groups are using a variety of network analysis techniques to detect gene expression signals following vaccine administration. [12,164]

The most promising elements of systems approaches are: the ability to detect novel mechanisms of immune function; to refine correlates of protection; and to identify biomarkers of immune response. Systems biology approaches have been applied to a number of vaccines with promising initial results. Some of the first systems biology studies applied to the vaccine field focused on the yellow fever vaccine YF-17D. [149,165] These studies showed that immune responses were preceded by expression level changes in a set of ~600 genes. Interestingly, these genes were coordinately regulated by transcription factors controlling type I IFN response, the inflammasome, and complement. Furthermore, these studies initially examined gene expression changes and then integrated transcription factor binding motif and information and pathway analysis in order identify genomic signatures of T cell and neutralizing antibody responses to the vaccine. The same investigators used a similar approach to understand immune responses to seasonal influenza vaccine and experimentally validated their findings using KO mice.[166] Influenza vaccine has been the target of several systems biology studies: Bucasas et al. identified a 494-gene expression signature that correlated with antibody response and demonstrated that high responders had increased expression of genes involved in IFN signaling and antigen processing/presentation.[167] The same investigative team also conducted an analysis integrating their immunologic and transcriptomic data with whole-genome genotyping and eQTL analysis. The combined data uncovered 20 genes where genetic polymorphisms influenced humoral immunity following influenza vaccination. [131] Furman et al. identified nine parameters (i.e. gene expression, serum cytokines, cell subset phenotypes) that collectively predicted antibody response to influenza vaccination. [168] Interestingly, these three studies all identified different gene signatures correlated with HAI response. These differences may be related to the variations in testing, timing of biospecimen collection, and/or analytic approaches, or indicate false-positive signals. Importantly, their data also indicated response parameters unique to each individual, implying that there may be multiple “signatures” of vaccine response. Some elements of these signatures may be in common among vaccine recipients, while other elements may vary. In contrast, several studies have identified similar elements of a B cell transcriptional signature that correlated with the presence of vaccine-specific plasma cells.[131,168,169] This highlights an important caveat of these studies: how do we reconcile different results, especially given the complexity and variations of the immunophenotyping, high dimensional data acquisition, and statistical analyses used by different groups? Another important point to consider is that these genetic signatures are selected based on statistical strength and not biology per se; therefore it is important to reconnect these genes with the relevant biological context. This limitation can be addressed by considering known biology, functional pathways, co-regulated gene sets or gene modules. [144,170–173] Obermoser et al. have examined innate and adaptive responses to both influenza and pneumococcal vaccines within the context of functional groupings of genes (modules). [169] As expected, each vaccine elicited expression profiles with both common and unique elements. Both vaccines triggered increased gene expression in modules associated with inflammation, apoptosis, T cell activity, and protein synthesis, while influenza vaccine also induced a strong, early IFN response less than 1 day after vaccination. The investigators isolated a variety of lymphocyte populations and tracked the signature to monocytes and neutrophils. On the other hand, pneumococcal vaccine elicited a strong plasmablast signature at Day 7. These data have been made publicly available along with analytic tools, in order to allow broader access to the primary data, facilitating further knowledge discovery by other researchers. One example of this is the NIH funded human immunology project consortium (HIPC: http://www.immuneprofiling.org/). The ultimate goal of HIPC is to create a publicly available resource of immune profiling data, methodologies, and tools.

Expert Commentary and Five Year View on Personalized Vaccinology

Vaccines have made remarkable contributions to human health and remain one of the most cost-effective medical interventions yet devised.[2] However, there are major diseases of global impact for which vaccines do not exist, but are ideal targets for the next generation of vaccine products. [174] Historically, vaccines have been made by empirical methods and are applied to entire populations in a one size fits all approach. While this approach has been tremendously successful, it has a number of disadvantages: candidate vaccines are largely developed in animal models and then must enter large and expensive clinical trials to demonstrate safety and efficacy; vaccine development also relies on an inconsistent or incomplete understanding of correlates of protection. Current issues that affect vaccine development, particularly for complex and hypervariable organisms, require a shift away from empirical approaches toward directed vaccine development approaches that capitalize on: cutting edge technologies; current understanding of innate and adaptive immune function; an increased awareness of vaccine safety; ability to predict and reduce adverse events; the effect of host-pathogen interactions; and the influence of the microbiome. Most important is the realization that human diversity (e.g. genetic, epigenetic, chronologic, and environmental) results in a wide spectrum of inter-individual vaccine responses.

While current vaccines and vaccine development approaches have substantially improved human health, such approaches have not been successful in developing protective vaccines against pathogens such as hepatitis C, HIV, rhinoviruses, etc. Such is also the case with complex organisms such as tuberculosis, malaria, and other parasitic and fungal organisms. In addition, current empiric approaches to vaccine development are slow, costly, and inefficient. The next step in vaccine development is to recognize these limitations and challenges and to realize that we need more personalized vaccines and approaches that are tailored to the needs of the recipients. From the point of view of the recipient, current immunization policies are conceived of and administered through a population-level paradigm. For example, if an individual’s genotype is such that they are not at risk of chronic infection due to hepatitis B or HPV; why administer a costly series of three vaccines to them? Other individuals have immune genotypes that allow for protective immune responses after a single dose of vaccine – why incur the expense, side effects, time, and other parameters to administer an additional two doses? We have previously comprehensively addressed such issues as these in other review papers. [9,11,15,175]

The idea of personalized vaccines is often a difficult concept for scientists to understand, though such approaches are already being utilized in therapeutic cancer vaccine approaches and will increasingly be used in other clinical areas. It is important to understand that at this point in time, it is difficult to conceive of vaccine development aimed at a single individual, but rather personalized approaches based on common understandings of common genotypes, genders, or even racial groups. For example, for all vaccines studied to date, healthy non-immunosenescent females produce higher levels of antibody to viral vaccines than males – if so should they receive the same dose and number of doses of a given vaccine as males? Vaccines can be created specific to HLA genotype based on HLA supertypes, a process we are already exploring in our laboratory. Too, we may alter or even avoid immunizing some individuals based on immune genotype-phenotype signatures that might predict significant adverse effects from a given vaccine. While the field is exciting, it is too early to answer all concerns and objections to the personalized vaccinology approach.

Additionally, personalized vaccine approaches may lead to the identification of more effective correlates of protection as well as predictive biomarkers, with concomitant improvements in vaccine safety and efficacy, as well as reductions in the time and costs required to bring new vaccines into the market. Although there are difficult challenges currently facing vaccinologists, we also know more about innate responses, adaptive immunity, and host biology than ever before. Similarly, we now possess advanced techniques and computational modeling strategies to characterize and understand the human immunology at the systems level, and are in an excellent position to face and overcome those challenges.

Key Issues.

Historically, vaccine development approaches have been empirical in nature

We are now dealing with emerging and re-emerging pathogens that are complex, highly variable, and have elaborate immune escape mechanisms

Society is increasingly risk-averse and demands very high levels of safety

The one-size-fits-all approach to vaccination ignores the incredible complexity and diversity of the human race

Vaccine development needs to be based on modern understanding of innate and adaptive immune processes

Immunity is not just antibody titer, new, and we need to develop improved correlates of protection that recognize this reality

The promise of vaccinomics, systems biology, and related paradigms is to identify biomarkers and signatures that predict vaccine safety and/or vaccine efficacy

Acknowledgments

All authors have NIH-funded grants/contracts to study the immunogenetics of viral vaccine responses and systems biology approaches to understanding influenza vaccines. Dr. Poland is the chair of a Safety Evaluation Committee for novel non-rubella investigational vaccine trials being conducted by Merck Research Laboratories. Dr. Poland offers consultative advice on vaccine development to Merck & Co. Inc., CSL Biotherapies, Avianax, Sanofi Pasteur, Dynavax, Novartis Vaccines and Therapeutics, PAXVAX Inc, and Emergent Biosolutions. Drs. Poland and Ovsyannikova hold patents related to vaccinia and measles peptide research.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

These activities have been reviewed by the Mayo Clinic Conflict of Interest Review Board and are conducted in compliance with Mayo Clinic Conflict of Interest policies. Mayo Clinic research reported here has been reviewed by the Mayo Clinic Conflict of Interest Review Board and was conducted in compliance with Mayo Clinic Conflict of Interest policies and the Mayo Clinic IRB or IACUC as appropriate. The other authors do not have any conflicts of interest.

References

Papers of particular note have been highlighted as:

* of interest

** of considerable interest

- 1.Fenner F, Henderson DA, Arita I, Jezek Z, Ladnyi ID. Smallpox and its Eradication. Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plotkin SA, Orenstein WA, Offit PA. Vaccines. Elsevier/Saunders, Edinburgh; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC. CDC Polio eradication update. 2014. CDC polio eradication effort update. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vesikari T. Rotavirus vaccination: a concise review. Clinical microbiology and infection : the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2012;18(Suppl 5):57–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muscat M, Shefer A, Ben Mamou M, et al. The state of measles and rubella in the WHO European Region, 2013. Clinical microbiology and infection : the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2014 doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramsay ME. Measles: the legacy of low vaccine coverage. Archives of disease in childhood. 2013;98(10):752–754. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2013-304292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poland GA, Oberg AL. Vaccinomics and bioinformatics: accelerants for the next golden age of vaccinology. Vaccine. 2010;28(20):3509–3510. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haralambieva IH, Poland GA. Vaccinomics, predictive vaccinology and the future of vaccine development. Future Microbiol. 2010;5:1757–1760. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poland GA, Ovsyannikova IG, Jacobson RM. Personalized vaccines: the emerging field of vaccinomics. Expert.Opin.Biol.Ther. 2008;8(11):1659–1667. doi: 10.1517/14712598.8.11.1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poland GA, Ovsyannikova IG, Kennedy RB, Haralambieva IH, Jacobson RM. Vaccinomics and a New Paradigm for the Development of Preventive Vaccines Against Viral Infections. Omics. 2011;15(9):625–636. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poland GA, Kennedy RB, Ovsyannikova IG. Vaccinomics and personalized vaccinology: Is science leading us toward a new path of directed vaccine development and discovery? PLoS Pathogens. 2011;7(12):e1002344. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poland GA, Kennedy RB, McKinney BA, et al. Vaccinomics, adversomics, and the immune response network theory: Individualized vaccinology in the 21st century. Seminars in Immunology. 2013;25(2):89–103. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carroll ML, Yerkovich ST, Pritchard AL, Davies JM, Upham JW. Adaptive immunity to rhinoviruses: sex and age matter. Respir Res. 2010;11:184. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook IF. Sexual dimorphism of humoral immunity with human vaccines. Vaccine. 2008;26(29–30):3551–3555. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klein SL, Poland GA. Personalized vaccinology: one size and dose might not fit both sexes. Vaccine. 2013;31(23):2599–2600. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.02.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klein SL. Sex influences immune responses to viruses, and efficacy of prophylaxis and treatments for viral diseases. BioEssays : news and reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental biology. 2012;34(12):1050–1059. doi: 10.1002/bies.201200099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Furman D, Hejblum BP, Simon N, et al. Systems analysis of sex differences reveals an immunosuppressive role for testosterone in the response to influenza vaccination. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111(2):869–874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321060111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pennell LM, Galligan CL, Fish EN. Sex affects immunity. Journal of autoimmunity. 2012;38(2–3):J282–J291. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoneyama M, Fujita T. Function of RIG-I-like receptors in antiviral innate immunity. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(21):15315–15318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700007200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kato H, Sato S, Yoneyama M, et al. Cell type-specific involvement of RIG-I in antiviral response. Immunity. 2005;23(1):19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawai T, Akira S. Antiviral signaling through pattern recognition receptors. Journal of Biochemistry. 2007;141(2):137–145. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvm032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pichlmair A, Schulz O, Tan CP, et al. RIG-I-mediated antiviral responses to single-stranded RNA bearing 5'-phosphates. Science. 2006;314(5801):997–1001. doi: 10.1126/science.1132998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kato H, Takeuchi O, Mikamo-Satoh E, et al. Length-dependent recognition of double-stranded ribonucleic acids by retinoic acid-inducible gene-I and melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2008;205(7):1601–1610. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiu YH, Macmillan JB, Chen ZJ. RNA polymerase III detects cytosolic DNA and induces type I interferons through the RIG-I pathway. Cell. 2009;138(3):576–591. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawai T, Takahashi K, Sato S, et al. IPS-1, an adaptor triggering RIG-I- and Mda5-mediated type I interferon induction. Nature immunology. 2005;6(10):981–988. doi: 10.1038/ni1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takaoka A, Wang Z, Choi MK, et al. DAI (DLM-1/ZBP1) is a cytosolic DNA sensor and an activator of innate immune response. Nature. 2007;448(7152):501–505. doi: 10.1038/nature06013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keating SE, Baran M, Bowie AG. Cytosolic DNA sensors regulating type I interferon induction. Trends in immunology. 2011;32(12):574–581. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lester SN, Li K. Toll-Like Receptors in Antiviral Innate Immunity. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aderem A, Ulevitch RJ. Toll-like receptors in the induction of the innate immune response. Nature. 2000;406(6797):782–787. doi: 10.1038/35021228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bieback K, Lien E, Klagge IM, et al. Hemagglutinin protein of wild-type measles virus activates toll-like receptor 2 signaling. J Virol. 2002;76(17):8729–8736. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.17.8729-8736.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bowie AG, Haga IR. The role of Toll-like receptors in the host response to viruses. Molecular Immunology. 2005;42(8):859–867. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kawai T, Akira S. Pathogen recognition with Toll-like receptors. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2005;17(4):338–344. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Nat.Rev.Immunol. 2001;1(2):135–145. doi: 10.1038/35100529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takeda K, Kaisho T, Akira S. Toll-like receptors. Annual Review of Immunology. 2003;21:335–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bowie AG. Translational mini-review series on Toll-like receptors: recent advances in understanding the role of Toll-like receptors in anti-viral immunity. DUPLICATE use 10177. 2007;147(2):217–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03301.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parker LC, Prince LR, Sabroe I. Translational mini-review series on Toll-like receptors: networks regulated by Toll-like receptors mediate innate and adaptive immunity. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2007;147(2):199–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03203.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barton GM. Viral recognition by Toll-like receptors. Seminars in Immunology. 2007;19(1):33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takeuchi O, Akira S. Recognition of viruses by innate immunity. Immunological Reviews. 2007;220(1):214–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jensen S, Thomsen AR. Sensing of RNA viruses: a review of innate immune receptors involved in recognizing RNA virus invasion. Journal of Virology. 2012;86(6):2900–2910. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05738-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Samuel CE. Antiviral actions of interferons. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14(4):778–809. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.4.778-809.2001. table. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garcia-Sastre A, Biron CA. Type 1 interferons and the virus-host relationship: a lesson in detente. Science. 2006;312(5775):879–882. doi: 10.1126/science.1125676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Randall RE, Goodbourn S. Interferons and viruses: an interplay between induction, signalling, antiviral responses and virus countermeasures. J Gen.Virol. 2008;89(Pt 1):1–47. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83391-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sadler AJ, Williams BR. Interferon-inducible antiviral effectors. Nat.Rev.Immunol. 2008;8(7):559–568. doi: 10.1038/nri2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boehme KW, Compton T. Innate sensing of viruses by toll-like receptors. Journal of Virology. 2004;78(15):7867–7873. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.15.7867-7873.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rassa JC, Ross SR. Viruses and Toll-like receptors. Microbes.Infect. 2003;5(11):961–968. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(03)00193-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Horng T, Barton GM, Medzhitov R. TIRAP: an adapter molecule in the Toll signaling pathway. Nat.Immunol. 2001;2(9):835–841. doi: 10.1038/ni0901-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fitzgerald KA, Palsson-McDermott EM, Bowie AG, et al. Mal (MyD88-adapter-like) is required for Toll-like receptor-4 signal transduction. Nature. 2001;413(6851):78–83. doi: 10.1038/35092578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamamoto M, Sato S, Mori K, et al. Cutting edge: a novel Toll/IL-1 receptor domain-containing adapter that preferentially activates the IFN-beta promoter in the Toll-like receptor signaling. Journal of Immunology. 2002;169(12):6668–6672. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.6668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oshiumi H, Matsumoto M, Funami K, Akazawa T, Seya T. TICAM-1, an adaptor molecule that participates in Toll-like receptor 3-mediated interferon-beta induction. Nat.Immunol. 2003;4(2):161–167. doi: 10.1038/ni886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cox JC, Coulter AR. Adjuvants--a classification and review of their modes of action. Vaccine. 1997;15(3):248–256. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00183-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mbow ML, De GE, Valiante NM, Rappuoli R. New adjuvants for human vaccines. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2010;22(3):411–416. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ebensen T, Guzman CA. Immune modulators with defined molecular targets: cornerstone to optimize rational vaccine design. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2009;655:171–188. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1132-2_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wilson-Welder JH, Torres MP, Kipper MJ, Mallapragada SK, Wannemuehler MJ, Narasimhan B. Vaccine adjuvants: current challenges and future approaches. J Pharm Sci. 2009;98(4):1278–1316. doi: 10.1002/jps.21523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Riese P, Schulze K, Ebensen T, Prochnow B, Guzman CA. Vaccine adjuvants: key tools for innovative vaccine design. Curr Top Med Chem. 2013;13(20):2562–2580. doi: 10.2174/15680266113136660183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ishii KJ, Akira S. Toll or toll-free adjuvant path toward the optimal vaccine development. Journal of Clinical Immunology. 2007;27(4):363–371. doi: 10.1007/s10875-007-9087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Talbot HK, Rock MT, Johnson C, et al. Immunopotentiation of trivalent influenza vaccine when given with VAX102, a recombinant influenza M2e vaccine fused to the TLR5 ligand flagellin. PLoS.ONE. 2010;5(12):e14442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ichinohe T. Respective roles of TLR, RIG-I and NLRP3 in influenza virus infection and immunity: impact on vaccine design. Expert.Rev.Vaccines. 2010;9(11):1315–1324. doi: 10.1586/erv.10.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Steinhagen F, Kinjo T, Bode C, Klinman DM. TLR-based immune adjuvants. Vaccine. 2011;29(17):3341–3355. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Olive C. Pattern recognition receptors: sentinels in innate immunity and targets of new vaccine adjuvants. Expert Review of Vaccines. 2012;11(2):237–256. doi: 10.1586/erv.11.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mastelic B, Ahmed S, Egan WM, et al. Mode of action of adjuvants: implications for vaccine safety and design. Biologicals : journal of the International Association of Biological Standardization. 2010;38(5):594–601. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mastelic B, Garcon N, Del Giudice G, et al. Predictive markers of safety and immunogenicity of adjuvanted vaccines. Biologicals : journal of the International Association of Biological Standardization. 2013;41(6):458–468. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mastelic B, Lewis DJ, Golding H, Gust I, Sheets R, Lambert PH. Potential use of inflammation and early immunological event biomarkers in assessing vaccine safety. Biologicals : journal of the International Association of Biological Standardization. 2013;41(2):115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang IM, Bett AJ, Cristescu R, Loboda A, ter Meulen J. Transcriptional profiling of vaccine-induced immune responses in humans and non-human primates. Microb Biotechnol. 2012;5(2):177–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2011.00317.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yan Q. Systems biology of influenza: understanding multidimensional interactions for personalized prevention and treatment. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;662:285–302. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-800-3_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Whitman WB, Coleman DC, Wiebe WJ. Prokaryotes: the unseen majority. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(12):6578–6583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature. 2012;486(7402):207–214. doi: 10.1038/nature11234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guzman JR, Conlin VS, Jobin C. Diet, microbiome, and the intestinal epithelium: an essential triumvirate? Biomed Res Int. 2013:425146. doi: 10.1155/2013/425146. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Filkins LM, Hampton TH, Gifford AH, et al. Prevalence of streptococci and increased polymicrobial diversity associated with cystic fibrosis patient stability. Journal of bacteriology. 2012;194(17):4709–4717. doi: 10.1128/JB.00566-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Guss AM, Roeselers G, Newton IL, et al. Phylogenetic and metabolic diversity of bacteria associated with cystic fibrosis. Isme J. 2011;5(1):20–29. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cabrera-Rubio R, Garcia-Nunez M, Seto L, et al. Microbiome diversity in the bronchial tracts of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2012;50(11):3562–3568. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00767-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu B, Faller LL, Klitgord N, et al. Deep sequencing of the oral microbiome reveals signatures of periodontal disease. PLos ONE. 2012;7(6):e37919. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Feazel LM, Robertson CE, Ramakrishnan VR, Frank DN. Microbiome complexity and Staphylococcus aureus in chronic rhinosinusitis. The Laryngoscope. 2012;122(2):467–472. doi: 10.1002/lary.22398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ley RE, Lozupone CA, Hamady M, Knight R, Gordon JI. Worlds within worlds: evolution of the vertebrate gut microbiota. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6(10):776–788. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hooper LV, Littman DR, Macpherson AJ. Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system. Science. 2012;336(6086):1268–1273. doi: 10.1126/science.1223490. * An excellent review that examines many of the reciprocal influences that the microbiome and the immune system have on one another

- 75.Vaishnava S, Yamamoto M, Severson KM, et al. The antibacterial lectin RegIIIgamma promotes the spatial segregation of microbiota and host in the intestine. Science. 2011;334(6053):255–258. doi: 10.1126/science.1209791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bevins CL. Innate Immune Functions of alpha-Defensins in the Small Intestine. Dig Dis. 2013;31(3–4):299–304. doi: 10.1159/000354681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ostaff MJ, Stange EF, Wehkamp J. Antimicrobial peptides and gut microbiota in homeostasis and pathology. EMBO Mol Med. 2013;5(10):1465–1483. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201201773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Macpherson AJ, Uhr T. Induction of protective IgA by intestinal dendritic cells carrying commensal bacteria. Science. 2004;303(5664):1662–1665. doi: 10.1126/science.1091334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Falk PG, Hooper LV, Midtvedt T, Gordon JI. Creating and maintaining the gastrointestinal ecosystem: what we know and need to know from gnotobiology. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62(4):1157–1170. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1157-1170.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bouskra D, Brezillon C, Berard M, et al. Lymphoid tissue genesis induced by commensals through NOD1 regulates intestinal homeostasis. Nature. 2008;456(7221):507–510. doi: 10.1038/nature07450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bos NA, Meeuwsen CG, Wostmann BS, Pleasants JR, Benner R. The influence of exogenous antigenic stimulation on the specificity repertoire of background immunoglobulin-secreting cells of different isotypes. Cellular Immunology. 1988;112(2):371–380. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(88)90306-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gaboriau-Routhiau V, Rakotobe S, Lecuyer E, et al. The key role of segmented filamentous bacteria in the coordinated maturation of gut helper T cell responses. Immunity. 2009;31(4):677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ichinohe T, Pang IK, Kumamoto Y, et al. Microbiota regulates immune defense against respiratory tract influenza A virus infection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(13):5354–5359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019378108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Abt MC, Osborne LC, Monticelli LA, et al. Commensal bacteria calibrate the activation threshold of innate antiviral immunity. Immunity. 2012;37(1):158–170. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lofland D, Josephat F, Partin S. Fecal transplant for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Lab Sci. 2013;26(3):131–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Smits LP, Bouter KE, de Vos WM, Borody TJ, Nieuwdorp M. Therapeutic potential of fecal microbiota transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(5):946–953. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chaban B, Albert A, Links MG, Gardy J, Tang P, Hill JE. Characterization of the upper respiratory tract microbiomes of patients with pandemic H1N1 influenza. PLos ONE. 2013;8(7):e69559. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lysholm F, Wetterbom A, Lindau C, et al. Characterization of the viral microbiome in patients with severe lower respiratory tract infections, using metagenomic sequencing. PLoS.ONE. 2012;7(2):e30875. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Alymova IV, Green AM, van dV, et al. Immunopathogenic and antibacterial effects of H3N2 influenza A virus PB1-F2 map to amino acid residues 62, 75, 79, and 82. Journal of Virology. 2011;85(23):12324–12333. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05872-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Peltola VT, Murti KG, McCullers JA. Influenza virus neuraminidase contributes to secondary bacterial pneumonia. J Infect Dis. 2005;192(2):249–257. doi: 10.1086/430954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Poland GA, Ovsyannikova IG, Jacobson RM, Smith DI. Heterogeneity in vaccine immune response: the role of immunogenetics and the emerging field of vaccinomics. Clin Pharmacol.Ther. 2007;82(6):653–664. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wang C, Tang J, Song W, Lobashevsky E, Wilson CM, Kaslow RA. HLA and cytokine gene polymorphisms are independently associated with responses to hepatitis B vaccination. Hepatology. 2004;39(4):978–988. doi: 10.1002/hep.20142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Li Y, Ni R, Song W, et al. Clear and independent associations of several HLA-DRB1 alleles with differential antibody responses to hepatitis B vaccination in youth. Human Genetics. 2009;126(5):685–696. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0720-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Desombere I, Willems A, Leroux-Roels G. Response to hepatitis B vaccine: multiple HLA genes are involved. Tissue Antigens. 1998;51(6):593–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1998.tb03001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hohler T, Reuss E, Evers N, et al. Differential genetic determination of immune responsiveness to hepatitis B surface antigen and to hepatitis A virus: a vaccination study in twins. Lancet. 2002;360(9338):991–995. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11083-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hohler T, Reuss E, Freitag CM, Schneider PM. A functional polymorphism in the IL-10 promoter influences the response after vaccination with HBsAg and hepatitis A. Hepatology. 2005;42(1):72–76. doi: 10.1002/hep.20740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hohler T, Stradmann-Bellinghausen B, Starke R, et al. C4A deficiency and nonresponse to hepatitis B vaccination. J Hepatol. 2002;37(3):387–392. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00205-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.De Silvestri A, Pasi A, Martinetti M, et al. Family study of non-responsiveness to hepatitis B vaccine confirms the importance of HLA class III C4A locus. Genes Immunit. 2001;2:367–372. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ovsyannikova IG, johnson KL, Bergen HR, III, Poland GA. Mass spectrometry and peptide-based vaccine development. Clin Pharmacol.Ther. 2007;82(6):644–652. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Poland GA, Jacobson RM, Colbourne SA, et al. Measles vaccine immunogenicity among Inuit, Innu, and non-native Canadian subjects; The Infectious Diseases Society of America 34th Annual Meeting; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Poland GA, Hagensee ME, Koutsky LA, et al. A randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the immunogenicity and reactogenicity of a novel HPV 16 vaccine: Preliminary results. 18th International Papillomavirus Conference, HPV Clinical Workshop, Barcelona, Spain. 2000 Jul 23–28;#363 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tosh PK, Boyce TG, Poland GA. Flu myths: dispelling the myths associated with live attenuated influenza vaccine. Mayo Clin.Proc. 2008;83(1):77–84. doi: 10.4065/83.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ovsyannikova IG, Jacobson RM, Vierkant RA, O'Byrne MM, Poland GA. Replication of rubella vaccine population genetic studies: validation of HLA genotype and humoral response associations. Vaccine. 2009;27(49):6926–6931. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.08.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ovsyannikova IG, Pankratz VS, Vierkant RA, Jacobson RM, Poland GA. Consistency of HLA associations between two independent measles vaccine cohorts: a replication study. Vaccine. 2012;30(12):2146–2152. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ovsyannikova IG, Jacobson RM, Dhiman N, Vierkant RA, Pankratz VS, Poland GA. Human leukocyte antigen and cytokine receptor gene polymorphisms associated with heterogeneous immune responses to mumps viral vaccine. Pediatrics. 2008;121(5):e1091–e1099. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ovsyannikova IG, Dhiman N, Haralambieva IH, et al. Rubella vaccine-induced cellular immunity: evidence of associations with polymorphisms in the Toll-like, vitamin A and D receptors, and innate immune response genes. Human Genetics. 2010;127:207–221. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0763-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Haralambieva IH, Dhiman N, Ovsyannikova IG, et al. 2'-5'-Oligoadenylate synthetase single-nucleotide polymorphisms and haplotypes are associated with variations in immune responses to rubella vaccine. Hum.Immunol. 2010;71(4):383–391. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Poland GA, Ovsyannikova IG, Jacobson RM. Immunogenetics of seasonal influenza vaccine response. Vaccine. 2008;26S:D35–D40. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.07.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ovsyannikova IG, Haralambieva IH, Vierkant RA, O'Byrne MM, Poland GA. Associations between polymorphisms in the antiviral TRIM genes and measles vaccine immunity. Human Immunology. 2013;74(6):768–774. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2013.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ovsyannikova IG, Haralambieva IH, Kennedy RB, O'Byrne MM, Pankratz VS, Poland GA. Genetic Variation in IL18R1 and IL18 Genes and Inteferon gamma ELISPOT Response to Smallpox Vaccination: An Unexpected Relationship. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2013;208(9):1422–1430. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kennedy RB, Ovsyannikova IG, Shane PV, Haralambieva IH, Vierkant RA, Poland GA. Genome-wide analysis of polymorphisms associated with cytokine responses in smallpox vaccine recipients. Human Genetics. 2012;131(9):1403–1421. doi: 10.1007/s00439-012-1174-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Clifford HD, Yerkovich ST, Khoo SK, et al. TLR3 and RIG-I gene variants: Associations with functional effects on receptor expression and responses to measles virus and vaccine in vaccinated infants. Human Immunology. 2012;73(6):677–685. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Pankratz VS, Vierkant RA, O'Byrne MM, Ovsyannikova IG, Poland GA. Associations between SNPs in candidate immune-relevant genes and rubella antibody levels: a multigenic assessment. BMC Immunol. 2010;11(1):48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-11-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kennedy RB, Ovsyannikova IG, Haralambieva IH, et al. Multigenic control of measles vaccine immunity mediated by polymorphisms in measles receptor, innate pathway, and cytokine genes. Vaccine. 2012;30(12):2159–2167. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Poland GA, Ovsyannikova IG, Jacobson RM. Application of pharmacogenomics to vaccines. Pharmacogenomics. 2009;10(5):837–852. doi: 10.2217/PGS.09.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ovsyannikova IG, Haralambieva IH, Vierkant RA, O'Byrne MM, Jacobson RM, Poland GA. The Association of CD46, SLAM, and CD209 Cellular Receptor Gene SNPs with Variations in Measles Vaccine-Induced Immune Responses--A Replication Study and Examination of Novel Polymorphisms. Human Heredity. 2011;72(3):206–223. doi: 10.1159/000331585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hijikata M, Ohta Y, Mishiro S. Identification of a single nucleotide polymorphism in the MxA gene promoter (G/T at nt −88) correlated with the response of hepatitis C patients to interferon. Intervirology. 2000;43(2):124–127. doi: 10.1159/000025035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Suzuki F, Arase Y, Suzuki Y, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphism of the MxA gene promoter influences the response to interferon monotherapy in patients with hepatitis C viral infection. J Viral Hepat. 2004;11(3):271–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2004.00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Torisu H, Kusuhara K, Kira R, et al. Functional MxA promoter polymorphism associated with subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Neurology. 2004;62(3):457–460. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000106940.95749.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.King JK, Yeh SH, Lin MW, et al. Genetic polymorphisms in interferon pathway and response to interferon treatment in hepatitis B patients: A pilot study. Hepatology. 2002;36(6):1416–1424. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.37198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Yakub I, Lillibridge KM, Moran A, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in genes for 2'-5'-oligoadenylate synthetase and RNase L inpatients hospitalized with West Nile virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2005;192(10):1741–1748. doi: 10.1086/497340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Knapp S, Yee LJ, Frodsham AJ, et al. Polymorphisms in interferon-induced genes and the outcome of hepatitis C virus infection: roles of MxA, OAS-1 and PKR. Genes Immun. 2003;4(6):411–419. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Hamano E, Hijikata M, Itoyama S, et al. Polymorphisms of interferon-inducible genes OAS-1 and MxA associated with SARS in the Vietnamese population. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2005;329(4):1234–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.02.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.He J, Feng D, de Vlas SJ, et al. Association of SARS susceptibility with single nucleic acid polymorphisms of OAS1 and MxA genes: a case-control study. BMC.Infect Dis. 2006;6:106. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ovsyannikova IG, Kennedy RB, O'Byrne M, Jacobson RM, Pankratz VS, Poland GA. Genome-wide association study of antibody response to smallpox vaccine. Vaccine. 2012;30(28):4182–4189. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.04.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kennedy RB, Ovsyannikova IG, Pankratz VS, et al. Genome-wide genetic associations with IFNgamma response to smallpox vaccine. Human Genetics. 2012;131(9):1433–1451. doi: 10.1007/s00439-012-1179-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Pan L, Zhang L, Zhang W, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies polymorphisms in the HLA-DR region associated with non-response to hepatitis B vaccination in Chinese Han populations. Human Molecular Genetics. 2013 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Falola MI, Wiener HW, Wineinger NE, et al. Genomic copy number variants: evidence for association with antibody response to anthrax vaccine adsorbed. PLos ONE. 2013;8(5):e64813. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Pajewski NM, Shrestha S, Quinn CP, et al. A genome-wide association study of host genetic determinants of the antibody response to Anthrax Vaccine Adsorbed. Vaccine. 2012;30(32):4778–4784. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Png E, Thalamuthu A, Ong RT, Snippe H, Boland GJ, Seielstad M. A genome-wide association study of hepatitis B vaccine response in an Indonesian population reveals multiple independent risk variants in the HLA region. Human Molecular Genetics. 2011;20(19):3893–3898. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]