Abstract

Detection and careful stratification of fetal heart rate (FHR) is extremely important in all pregnancies. The most lethal cardiac rhythm disturbances occur during apparently normal pregnancies where FHR and rhythmare regular and within normal or low-normal ranges. These hidden depolarization and repolarization abnormalities, associated with genetic ion channelopathies cannot be detected by echocardiography, and may be responsible for up to 10% of unexplained fetal demise, prompting a need for newer and better fetal diagnostic techniques. Other manifest fetal arrhythmias such as premature beats, tachycardia, and bradycardia are commonly recognized. Heart rhythm diagnosis in obstetrical practice is usually made by M-mode and pulsed Doppler fetal echocardiography, but not all fetal cardiac time intervals are captured by echocardiographic methods. This article reviews different types of fetal arrhythmias, their presentation and treatment strategies, and gives an overview of the present and future diagnostic techniques.

Keywords: fetal arrhythmia, magnetocardiography, electrocardiography, tachycardia, bradycardia, stillbirth, long QT syndrome, fetal demise

Fetal Arrhythmia and Its Clinical Importance

Fetal arrhythmias account for approximately 10 to 20% of referrals to fetal cardiologists. The majority of these rhythms will have either resolved by the time of evaluation, or they will consist of atrial ectopy. The detection of a fetal arrhythmia by an obstetrical care provider should prompt rapid referral to a fetal cardiac center of excellence for further assessment, especially if the arrhythmia is sustained.

Careful stratification of fetal heart rate (FHR) by gestation is important in all pregnancies, since potentially lethal conditions such as long QT syndrome or fetal thyrotoxicosis may have only minimal persistent alterations in FHR. In addition, most clinicians think of cardiac electrophysiologic disorders only when the heart rate or rhythm is abnormal, whereas the most lethal cardiac rhythm disturbances occur during normal rate and regular rhythm and are due to depolarization and repolarization abnormalities. Previously, unrecognized rhythm disturbances include cardiac channelopathy disorders such as long QT syndrome, malignant but very brief and transient arrhythmias such as junctional or ventricular tachycardia, and chronic conduction disturbances such as bundle branch block that are associated with certain congenital heart defects (CHDs), severe-metabolic derangements, myocarditis, and certain maternal medications. These “silent” arrhythmias cannot be detected using ultrasound, but some can be suspected due to persistent FHRs between 110 beats per minute (bpm) and the lower limits of normal rate for gestation. This, coupled with a careful family history of fetal/neonatal demise or sudden unexplained death in a young adult, may provide clues to these hidden ion channelopathies. Fetal diagnosis using advanced technologies such as fetal magnetocardiography or electrocardiography can be confirmed where available, or diagnosis made after delivery using electrocardiography.

The prognosis and treatment of the arrhythmia will depend on accurate and complete diagnosis, which in the majority of cases is made by M-mode and pulsed Doppler fetal echocardiography. However, fetal echocardiography does not capture cardiac time interval wave forms such as the P wave duration, the QRS duration, or the QT interval. An incomplete/incorrect diagnosis can lead to mismanagement and incorrect treatment which can jeopardize the well-being of the fetus and the mother.

Due to the advances in prenatal care, rhythm disturbances are now being recognized using advanced technologies, which will be described in the following paragraphs.1–8

Rhythm detection technologies are used at all other ages in medical care, including intensive care monitoring and diagnostic electrophysiology, and it is only a matter of time before advanced fetal technologies will provide obstetricians and fetal cardiologists with a new window into the health and disease of the susceptible fetus.

Different Methods of Diagnosing Fetal Arrhythmias

Fetal Ultrasound

Ultrasound is the primary modality for the diagnosis of fetal arrhythmias. The obstetrician observing an arrhythmia must first differentiate arrhythmia from fetal distress. Most confirmed arrhythmias are best evaluated and treated in utero, and unconfirmed rhythm disturbances vigilantly followed. The initial ultrasound scan should include measurement of atrial and ventricular rate, determination of whether these are regular or irregular, and whether there is a 1:1 association of atrial to ventricular contraction. In addition, fetal growth, biophysical profile, and umbilical or ductus venosus Doppler flow patterns can be defined, as rapidly as possible, provided it does not delay referral of the fetus to an arrhythmia specialist. It is important to record digital clips of any arrhythmia observed, since fetal arrhythmias may be transient, and retrospective analysis may be required. Referral to a maternal–fetal medicine (MFM) specialist should be quick to obtain a full targeted ultrasound, looking for anomalies, organ dysfunction, and acquired diseases (e.g., goiter in a tachycardic fetus), as well as to further define the arrhythmia. If the duration of the first visit for the MFM is long, direct fetal cardiac referral can be obtained first followed by subsequent MFM assessment—the goal being to provide rapid diagnosis and treatment. More targeted assessment by ultrasound, Doppler, and M-mode is described in the following section.

Fetal Echocardiography

Fetal echocardiography is the mainstay of perinatal assessment tools for fetal heart evaluation. Recently, there has been a shift from M-mode to Doppler techniques for assessing rhythm. M-mode still plays an important role in assessing the atrial and ventricular wall motion, cardiac function, and contraction patterns. Some echocardiography equipment has independently directed cursors that can project simultaneous atrial and ventricular M-modes, but if not, the goal should be to transect the heart, obtaining simultaneous atrial and a ventricular wall motion. Pulsed Doppler is important in assessing mechanical PR interval, presence of atrioventricular (AV) valve regurgitation, venous flow reversal, cardiac output, and predicting VA or AV sequencing.

Rein et al9 have shown that tissue Doppler recording provides accurate diagnosis of arrhythmias, but there is still an inability to fully assess fetal rhythm because echocardiography measures the mechanical consequence of the arrhythmia rather than the arrhythmia or conduction itself. Further, echo/Doppler does not allow for prolonged continuous monitoring (similar to telemetry), and hence, can miss fleeting arrhythmias and heart rate trend patterns over time.

The techniques for fetal echocardiography have been divided into those that are standard and those that are more advanced. Table 1 lists views for rhythm assessment. It is beyond the scope of this review to cover all aspects of the fetal echo examination, and we refer the reader to the American Heart Association’s Scientific Statement on Fetal Diagnosis and Treatment which will be published in 2014.

Table 1.

Echocardiographic rhythm assessment: echocardiographic views and measurements for fetal arrhythmia assessment

| 2D | Pulsed and color Doppler | M-mode | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extracardiac imaging | Hydrops Extracardiac birth defects Organ enlargement or injury Amniotic fluid assessment |

Ductus venosus notching Middle cerebral artery/umbilical artery resistance indices and systolic/diastolic ratios Hepatic vein/IVC/SVC flow reversal |

|

| Intracardiac imaging | Structural cardiac defects A and V function Qualitative wall thicknesses, rhythm characteristics, chamber sizes, and foramen ovale size (orifice > 30% of atrial septum length) |

Mechanical PR (AV), VA (if SVT), VV (cycle length) intervals Flow velocities at all valves and transvalvular gradients (Bernoulli equation) Color Doppler flow patterns during arrhythmia, AV valve insufficiency, foramen ovale, and ductus arteriosus flow velocities, F or SVT sequencing of Doppler in pulmonary vein/pulmonary artery and/or SVC/ascending aorta |

Atrial and ventricular contraction (bisecting atrial/ventricular wall and heart rate(s) Quantification of A and V function, AV contraction sequence and interval |

Abbreviations: A, atrium; AV, atrioventricular; IVC, inferior vena cava; SVT, supraventricular tachycardia; V, ventricle.

Electromechanical dysfunction has been reported with several types of arrhythmias, especially blocked atrial bigeminy, atrial flutter (AF), and long QT syndrome.10,11 In such cases, the mechanical rhythm does not accurately reflect the electrical rhythm. Intermittent myocardial akinesis, or hypokinesis canmimic absence of a P or QRS, when in fact, they are present. In the future, the most powerful tool will be a combination of fetal echocardiography and fetal magnetocardiography used for continuous monitoring, function assessment, and rhythm/conduction pattern evaluation.

Cardiotocography

Cardiotocography (CTG) registers baseline FHR and FHR variability by Doppler as well as registering uterine contractions. The use of CTG is usually limited to > 30 weeks’ gestation. CTG technology functions poorly during fetal tachycardia or AV block. It is best used to trend certain treatments such as the response to transplacental medications and as an adjunct to biophysical profiles for fetal assessment when sinus rhythm is the predominant rhythm.

Fetal Electrocardiography

Fetal electrocardiogram (fECG) can detect QRS signals in fetuses from as early as 17 weeks’ gestation; however, the technique is limited by the minute size of the fetal signal relative to noise ratio. This is impacted by early gestation, maternal noise such as uterine contractions, degree of electrical insulation caused by the surrounding tissues (vernix caseosa), and skin resistance. Fetal electrocardiography during labor (using a scalp lead) has also been studied in more than 15,000 patients after 36 weeks’ gestation.12–16

Overall, fetal electrocardiography has not been adopted widely in clinical applications, likely due to its inconsistent quality. Normal values for fetal ECG have been reported.17–21 Gardiner et al demonstrated fetal ECG’s utility in assessing first degree AV block associated with maternal collagen vascular disease.19 Recently, Velayo et al reported fetal ECG in CHDs and twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome.22

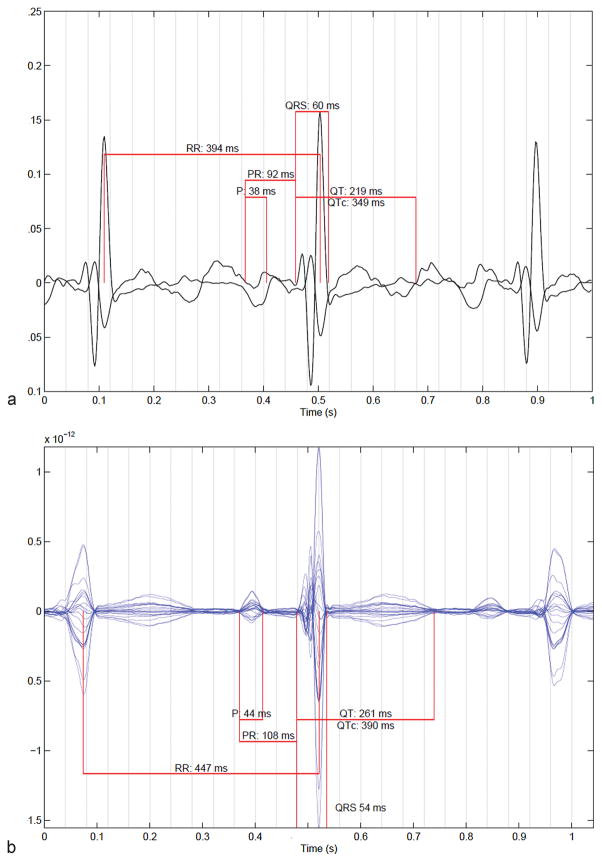

However, in one series, only 61% of subjects showed adequate signal fidelity for P and T wave interpretation.18 QRS detection alone can generally be achieved. Compared with mechanical PR intervals derived from pulsed Doppler echocardiography, fetal ECG PR intervals were shorter.17,18,23,24 Tissue Doppler, at the right AV groove, better estimated fECG PR intervals than did pulsed-wave Doppler17 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A 20-second signal-averaged waveform of a normal fetal heart rate in a 38-week gestational age fetus by (a) fECG and (b) fMCG. fECG, fetal electrocardiogram; fMCG, fetal magnetocardiography.

Fetal Magnetocardiography

Fetal magnetocardiography (fMCG) is more precise in clarifying fetal arrhythmias and conduction. Because it is very expensive, the method is only available in a small number of laboratories worldwide.

The fetal magnetocardiogram is acquired by using sensitive biomagnetometers based on superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) technology. Unlike magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), SQUIDs are passive receivers that do not emit energy or magnetic fields. The studies must be performed within a magnetically shielded room which attenuates magnetic interference from external sources, including the earth’s magnetic field. Two types of fMCG recording devices have been developed. One allows the patient to recline,25,26 while the other allows to lean forward over the SQUID sensors.27 In the Biomagnetism Laboratory at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, more than 800 subjects, at least 400 with fetal arrhythmias, have undergone recording. These fetal MCG recordings capture each of the cardiac time intervals (P, QRS, and T waves, RR, PR, and QT intervals) in almost all fetuses over 24 weeks’ gestation, and QRS and RR intervals in most fetuses over 17 weeks’ gestation.26,28 Normative data have been reported.20,25–35 Once the maternal MCG is extracted, the fetal MCG can also be displayed as uninterrupted segments of recording.36–38 This is similar to telemetry or Holter monitoring making it possible to detect brief nonsustained arrhythmias such as torsades de pointes (TdP) ventricular tachycardia.

Over the prior decade, fMCG has been shown to improve the accuracy and precision of diagnosis in longQTsyndrome,5,7,39–43 congenital atrioventricular block (CAVB),3,37,44–47 and various tachyarrhythmias.2,10,40,46,48,49 fMCG has supported echocardiography in the evaluation of fetuses with structural cardiac defects, ventricular aneurisms,50 and cardiac tumors.51 fMCG has led to changes in rhythm diagnosis and detection of unsuspected arrhythmias that have subsequently modified medical care, including the choice or use of drug therapies3,5,7,39 (Fig. 2).

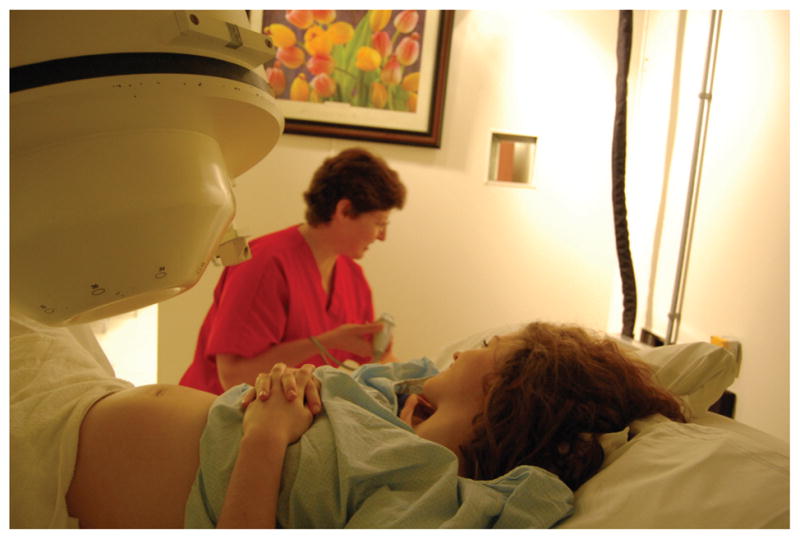

Fig. 2.

Dr. Strasburger performing ultrasound within the magnetically shielded room at UW-Madison Biomagnetism Laboratory, The superconducting quantum interference device above the patient is not yet in position against the maternal abdomen.

Fetal Arrhythmia Mechanisms

Although fetal arrhythmias account for a small percentage (0.6–2.0% of all pregnancies) certain of these arrhythmias are associated with a high morbidity and mortality. Hidden fetal arrhythmias may contribute to a high rate of fetal demise (perhaps 3–10%), unexplained hydrops, and prematurity.52

Fetal Atrial and Ventricular Ectopy

Irregular heart rhythms are the most common abnormal rhythms seen in clinical practice. Fetal ectopy occurs in up to 1 to 2% of all pregnancies and has been reported to be a relatively benign condition. Fetal ectopy is mainly atrial, rather than ventricular in origin. Two percent of the fetal ectopy patients have additionally associated PR prolongation which can be associated with long QT syndrome, fetal or neonatal AF, and second-degree AV block.53,54 The risk of developing fetal tachycardia is approximately 0.5 to 1%. The presence of couplets and blocked atrial bigeminy increases this risk to approximately 10%.11 Medication treatment is not required but patients should be monitored weekly by auscultation or imaging to detect supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) before it becomes life threatening (Fig. 3).

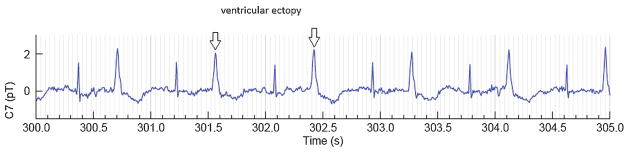

Fig. 3.

Ventricular ectopy in a bigeminy pattern.

Fetal Bradycardia

The standard obstetric definition of fetal bradycardia has been a sustained FHR < 110 bpm over at least a 10-minute period. FHRs are gestational age dependent, and decrease significantly as gestation progresses from a median of 141 bpm(interquartile range 135–147bpm) < 32 weeks’ gestation to 137 bpm (interquartile range 130–144 bpm) > 37 weeks’ gestation. These interquartile ranges correspond to the middle 50% of subjects. Persistent heart rates below the third percentile, may be normal, but can also be a marker for significant conduction disease. Mitchell et al reported that 40% of the long QT syndrome cases evaluated by fMCG were referred due to sinus bradycardia.55

Brief episodes of transient fetal decelerations that resolve within minutes are often noted especially in the second trimester and are thought to be benign. Persistent fetal bradycardia for gestation may be due to sinus, low atrial or junctional bradycardia, blocked atrial bigeminy, or atrioventricular block and need evaluation to distinguish between them.

Fetal Sinus and Low Atrial Bradycardias

In fetuses with sinus and low atrial bradycardias, FHRs range between 90 and 130 bpm. Persistent fetal bradycardia is relatively rare. The basic mechanisms include congenital displaced atrial activation or acquired damage of the sinoatrial node. Sinus node rates can be suppressed, for example, due to (1) left and right atrial isomerism, (2) inflammation and fibrosis in a normal sinus node in patients with viral myocarditis or collagen vascular disorders (SSA/Ro [+] or SSA/Ro and SSB/La [+] antibodies), or (3)maternal treatment with β blockers, sedatives, or othermedications.56 No fetal therapy is required for sinus or low atrial bradycardia, however, observation is recommended.

Fetal Atrioventricular Block

CAVB can be related to either an anatomical displacement or due to inflammatory damage and/or fibrosis of the conduction system. A third group has an undetermined etiology. The most important characteristic of advanced fetal AV block is that the atrial rate is regular and normal, and AV dissociation is present with slower ventricular rate. First-, second-, and third-degree (complete) AV blocks occur, though progression from one to another is not usually seen. The block is often unstable at first, with associated rhythm disturbances.3

Fetal Atrioventricular Block Associated with Structural Heart Disease

Congenital cardiac defects associated with AV block include mainly heterotaxy syndromes (primarily left atrial isomerism) and congenitally corrected transposition.

These cardiac defects are very complex. The right and left chambers are malaligned with the inflow and outflow portions of the heart, resulting in a discontinuity between the AV node and the conduction system. Similarly, the absence of the sinus node in left atrial isomerism can lead to a slower atrial rhythm in these fetuses. The combination of CAVB and major structural heart disease carries high mortality. When hydrops is present, it approaches 100%.

Fetal Atrioventricular Block without Structural Heart Disease

Isoimmune Fetal Atrioventricular Block

The majority of CAVB in structurally normal hearts is secondary to immune-mediated inflammation and fibrosis of the fetal conduction system from maternal SSA/Ro and/or SSB/La antibodies which can cross the placenta.

The incidence of CAVB in patients with SSA/Ro and SSB/La antibodies is approximately 2 to 3%. The risk is higher in pregnant women who previously had an affected child with either CHB or a neonatal lupus rash and may be substantially lower in pregnant women with low SSA/Ro titers.57,58 In fetuses with CAVB and hydrops or endocardial fibroelastosis, high rates of mortality (6–20% or more) and morbidity have been described. In addition life-threatening late-onset cardiomyopathies have also been found.59,60 Other manifestations of SSA/Ro-mediated or SSB/La-mediated cardiac disease include sinus node dysfunction, bundle branch block, and late-onset rupture of the AV valve chordae.10

AV block is generally not seen before 18 weeks’ gestation and onset is rare after 28 weeks’ gestation. Half of these women are asymptomatic concerning their rheumatologic disorder and are unaware that they carry the antibodies. This makes pre-emptive evaluation difficult.

Nonisoimmune Fetal Atrioventricular Block

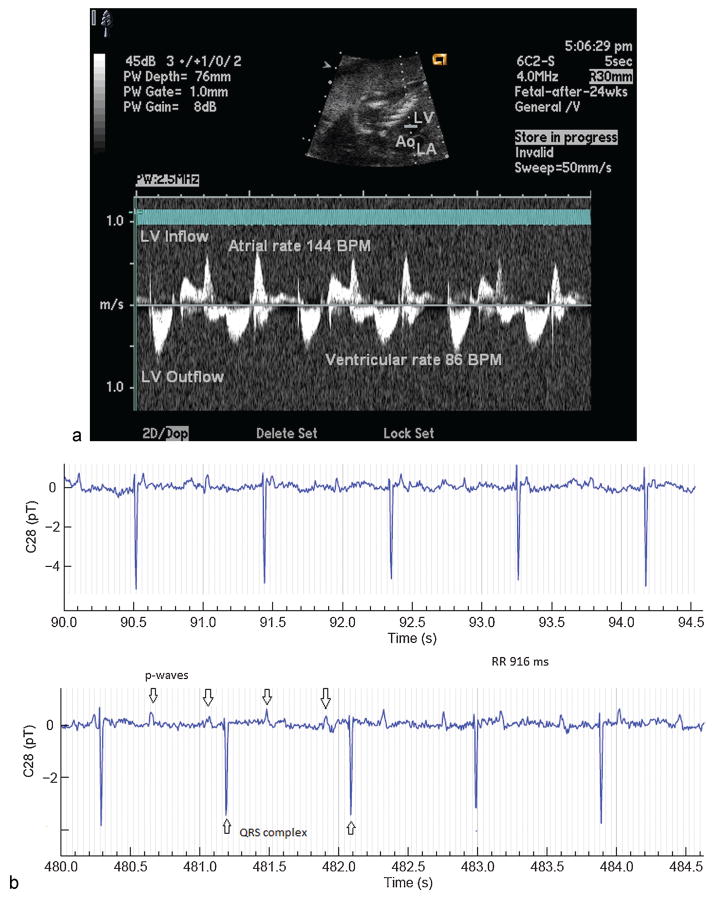

Isolated complete AV block without positive SSA/Ro or SSB/La antibodies is rare and appears to have the best long-term prognosis. Baruteau and Study reported survival of 100% in 120 children with isolated AV block, 23 of whom presented in utero or in the first month of life61 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

AV block by (a) echocardiography and (b) fMCG. AV, atrioventricular; fMCG, fetal magnetocardiography.

Treatment Options of Fetal Atrioventricular Block

Treatment of AV block depends on the etiology, the ventricular rate, and the presence and degree of heart failure.

First, β sympathomimetics (terbutaline, salbutamol, isoprenaline) have been used to elevate low fetal ventricular rates (< 55–60 bpm).44,62 Fetuses may therefore improve if they have symptoms of heart failure; however, no studies have demonstrated survival benefit. Terbutaline is normally well tolerated, but maternal resting heart rates around 100 to 120 bpm and benign maternal ectopy have been commonly encountered.44 Immune-mediated AV block may benefit from in utero treatment with fluorinated steroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, or both. Dexamethasone is believed to reduce inflammation.59,63 Although no consensus exists, many clinicians are using dexamethasone 4 to 8 mg/d to treat second-degree AV block, recent onset AV block, or severe cardiac dysfunction and hydrops. A window of time may exist when incomplete AV block can be reversed, and therefore quick referral is suggested for fetal bradycardia patients where FHR is < 80 bpm. Given the higher rates of AV block in winter months, 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels should be assessed and deficiencies corrected64 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Checklist for persistent fetal bradycardia and management of fetal bradycardia or suspected long QT syndrome

| Differential diagnosis for persistent fetal bradycardia | |

|---|---|

| Maternal (or familial) conditions | Fetal/neonatal conditions |

| Long QT syndrome may present in the patient, father of fetus, or close family member as generalized seizures, recurrent syncope, sudden death, or unexplained accidental death from drowning or one car accident, neural deafness, or syndactyly Long QT syndrome is autosomal dominant in most cases. If present, all first degree relatives should be screened with ECG and electrophysiology consultation |

Fetal/neonatal long QT syndrome Presentation in the fetus includes second degree AV block, sinus bradycardia, torsades de pointes ventricular tachycardia, and sudden intrauterine fetal demise. LQTS can present in the neonate as sudden infant death syndrome |

| Other rare heritable bradycardia syndromes in the patient, father of fetus, or close family member (e.g., low atrial rhythms, sinus node dysfunction, history of pacemaker) | Rare heritable bradycardia syndromes can present with sinus or junctional bradycardia |

| Congenital cardiac disease has varying risk of recurrence. First degree relatives with CHD should have screening echo at 18–22 wk GA | Heterotaxy syndromes, usually manifesting with dextrocardia, complex CHD, but may be more subtle with only interrupted IVC, dual SVC, or other venous malformations |

| SSA/Ro and/or SSB/La antibodies, and maternal thyroid disease | SSA/SSB isoimmunization with sinus node dysfunction |

| Medications (e.g., beta blockers) | Medications (e.g.,. beta blockers) |

| Illness/infection | Infectious diseases |

| Idiopathic | Rare metabolic disorders (e.g., Pompe disease) |

| Idiopathic, or sinus bradycardia due to neck stretch or other autonomic causes | |

| Management of pregnancy complicated by persistent fetal bradycardia or suspected long QT syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Maternal checklist | Fetal/neonatal checklist |

| Referral to center of excellence for fetal cardiology/electrophysiology evaluation | Avoidance or closely monitored use, if necessary, of any medications that lengthen QT interval |

| Avoidance of or closely monitored use of (if necessary) any medications that lengthen QT interval (e.g., odansentrone, pitocin, azithromycin, antidepressants, etc.) | Neonatal ECG ± Holter monitor, repeat ECG at 3 wk of age if QTc is prolonged at birth |

| Exclude maternal electrolyte disorders (25(OH) Vit D deficiency, hypomagnesemia, hypocalcemia, or hypokalemia | Exclude neonatal electrolyte disorders that may be proarrhythmic (hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, hypokalemia) |

| Fetal magnetocardiography or electrocardiography (if available) | Retain cord blood for possible neonatal genetic testing for ion channelopathies |

Abbreviations: CHD, congenital heart defect; IVC, inferior vena cava.

Fetal Tachycardia

Tachycardia is generally characterized by sustained FHR above 160 bpm. The most common forms of tachycardia are SVT, AF, sinus tachycardia, and ventricular or junctional tachycardia (VT) which typically show heart rates greater than 200 bpm. Heart rates between 180 and 200 bpm are less common, but may appear, for example, with maternal use of stimulants, amnionitis, maternal thyrotoxicosis, or other systemic fetal disease and with some rare arrhythmias.

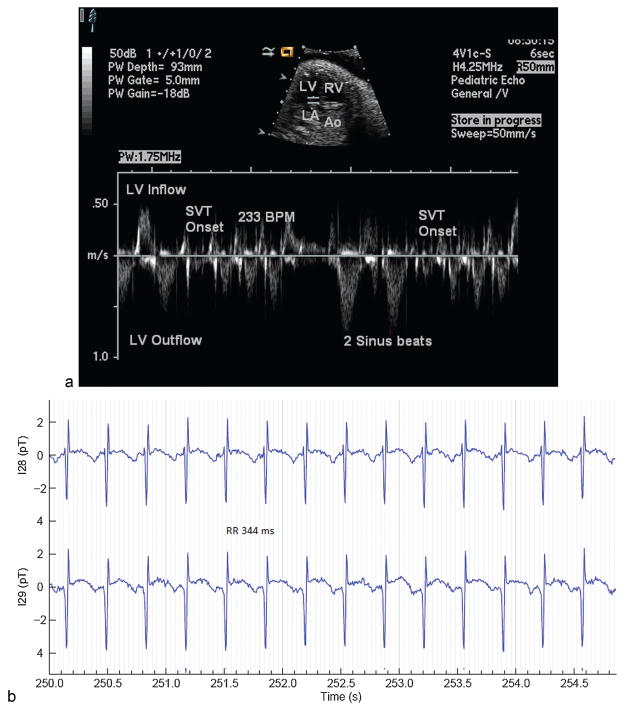

Fetal tachycardias can cause fetal hydrops, premature delivery, and perinatal morbidity and mortality. This is largely due to inability to detect tachycardia until hydrops appears. Progression of hydrops can be rapid at earlier gestational age, at higher ventricular rates, and for incessant tachycardias. With complex and unusual types of tachycardia, defining the mechanism is important because it can impact the choice of therapy. Finally, there can be a poor response to transplacental treatment. We have recently been impressed that correction of underlying maternal electrolyte abnormality (Ca2+, Mg2+, and K+), as well as vitamin D deficiency, can facilitate pharmacoconversion of tachycardia and maintenance of sinus rhythm (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

SVT measured by (a) echocardiography and (b) by fMCG. fMCG, fetal magnetocardiography; SVT, supraventricular tachycardia.

Re-entrant Supraventricular Tachycardia

The most common fetal tachycardia is re-entrant SVT mediated by an accessory connection which accounts for almost two-thirds of fetal tachycardia. It mainly develops between 24 and 32 weeks’ gestation. SVT is commonly initiated by an ectopic beat, though other complex patterns are seen. When it breaks to normal sinus rhythm, the rate of the subsequent rhythm should be normal for gestational age. Choice of antiarrhythmic therapy is influenced by several factors. At present, there is no consensus on first-line treatment of SVT. For the hydropic fetus, flecainide may be slightly more effective than sotalol.65 Intramuscular digoxin reduced the time to conversion of SVT in one report.66 Combination therapies (amiodarone/digoxin, amiodarone/flecainide, sotalol/digoxin, and sotalol/flecainide) have been reported to be effective when other agents have failed though such combinations potentiate the risk of adverse effects and should be reserved for critical cases (J.F. Strasburger et al, unpublished data, 2001).65,67 For the nonhydropic fetus, sotalol, flecainide, and digoxin are commonly used. Monitoring fetuses after SVT conversion is important, since the fetal diuresis after SVT conversion can cause rapid progressive polyhydramnios and preterm labor in up to 40%. The use of home hand-held Doppler monitors is being investigated to more rapidly detect SVT recurrences. (B.F. Cuneo, personal communication).

Atrial Flutter

AF is the second most common cause of fetal tachycardia, accounting for approximately 30% of cases.65,68–70 Jaeggi et al reported that fetal hydrops developed in 13% of the cases.65 AF can be seen with myocarditis, structural heart disease, and SSA isoimmunization.4,71 Accessory AV pathways and reentrant SVT are a common association.72 Currently, digoxin and sotalol are used to treat AF, with sotalol preferred in the presence of hydrops.73

Junctional Ectopic Tachycardia

Junctional tachycardia is relatively rare, although undoubtedly underdetected by current diagnostic means. Junction ectopic tachycardia (JET) is mainly associated with SSA/Ro antibodies, and has been reported in both the presence and absence of AV block.2,3,6,74 The heart rate in a JET is typically between 160 and 210 bpm, nonsustained, and slower than in ventricular tachycardia. The therapy is directed at the underlying cause (e.g., inflammation).

Ventricular Tachycardia

VT has been observed with underlying cardiac diseases such as cardiac tumors, ventricular aneurysms, myocarditis, long QT syndrome, and unstable phases of AV block.3,7,39,68 Common accompanying rhythms are premature ventricular contractions, sinus bradycardia, and AV block. The echocardiogram can show ventricular dysfunction, AV valve regurgitation, and often hydrops.5 Ventricular tachycardia is often unrecognized because of its brief paroxysmal nature.

Maternal transplacental short-duration intravenous magnesium treatment should be considered as first-line therapy. 39,75 Transplacental propranolol, lidocaine, mexiletine, flecainide, sotalol, and amiodarone have all been used for fetal treatment of ventricular tachycardia.39,76 The latter three drugs should be avoided if long QT syndrome is suspected (Table 3).

Table 3.

Differential diagnosis for fetal tachycardia and management for fetal tachycardia

| Differential diagnosis for fetal tachycardia | |

|---|---|

| Maternal conditions | Fetal conditions |

| Rheumatologic disease (e.g., Lupus, Sjogrens) | Fetal tachyarrhythmia (SVT, a flutter, JET, VT) |

| Thyroid disease with clinical hyperthyroid state, or with positive antithyroid antibodies (which can be present even when patient is euthyroid) | Fetal thyrotoxicosis (sinus tachycardia) |

| Infection or fever | Infection or myocarditis (sinus tachycardia) |

| Drugs (e.g., cocaine, β-sympathomimetics) | Drug induced (sinus tachycardia) |

| Injury, shock | Primary cardiomyopathy (sinus tachycardia) |

| Management for fetal tachycardia | |

|---|---|

| Maternal checklist | Fetal/neonatal checklist |

| Avoidance of caffeine, β-sympathomimetics, nicotine, illicit drugs, or combinations | Avoidance of second hand exposure to caffeine, beta sympathomimetics, nicotine, illicit drugs, or combinations (including through breast milk) |

| ECG, and if indicated cardiology consult if transplacental treatment is anticipated | Exclusion of goiter, infection, and other treatable conditions |

| Electrolytes and maternal vitamin D assessment | Fetal antiarrhythmic drug levels from cord blood if appropriate at the time of birth |

| Maternal drug therapies (see text) | Adenosine readily available for neonatal SVT if appropriate |

Abbreviations: JET, junction ectopic tachycardia; SVT, supraventricular tachycardia; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Genetic Ion Channelopathies (Long QT Syndrome)

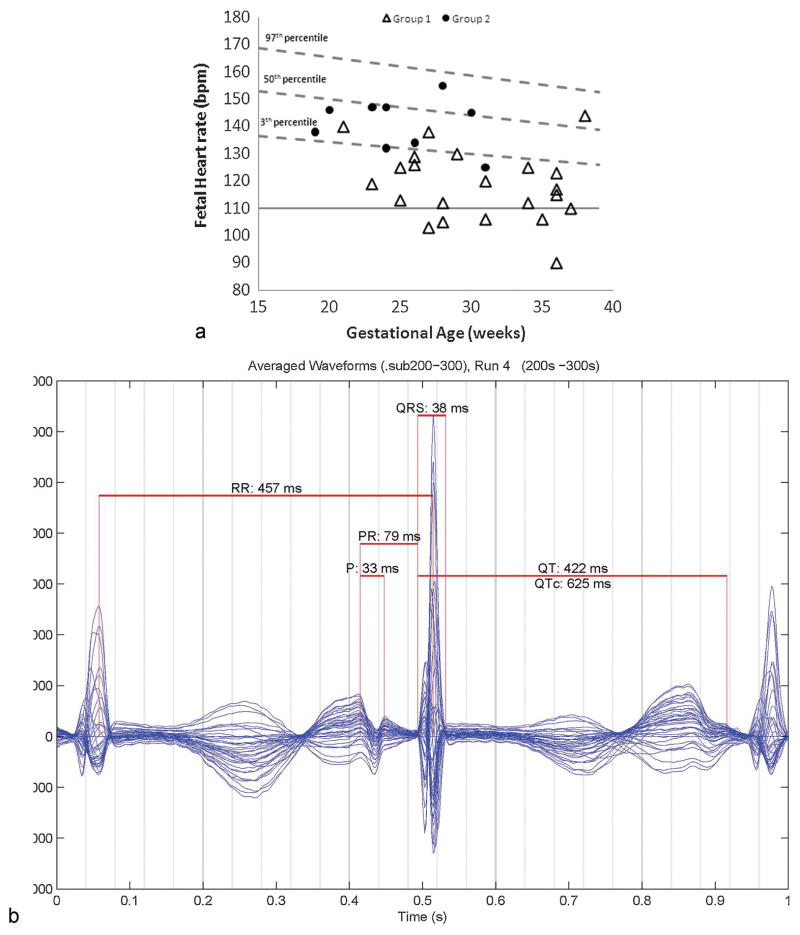

Unexplained fetal demise after 20 weeks’ gestation, or stillbirth, is now suspected to be due to ion channelopathy syndromes in approximately 3 to 10% of cases based on genetic autopsy.52 The most common fetal presentation of long QT syndrome is fetal bradycardia, but the syndrome can also be associated with intermittent or persistent TdP ventricular tachycardia, second-degree AV block, or both.10,39 The more serious fetal presentations are usually seen with SCN5A or rare forms of LQTS. In fMCG studies, TdP and second-degree AV block pre- or postnatally were common in fetuses with QTc intervals of more than 580 ms and with easily visible T-wave alternans.10 If LQTS is confirmed or suspected in the fetus (or in the mother), close observation and avoidance of drugs that lengthen QT interval is recommended. A frequently updated list of these drugs can be found on several Web sites (e.g., www.torsades.org). As mentioned previously, electrolyte and vitamin D deficiency should be corrected. Fetal transplacental treatment is not necessary for bradycardia, but TdP requires treatment. Treatments are outlined in the ventricular tachycardia section. A family history should be obtained for other effected family members who may need to be evaluated. Delivery of the fetus in a center familiar with neonatal electrophysiology and postnatal genetic testing for LQTS is also recommended (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

(A) Fetal heart rates (FHRs) in group 1 with long QT syndrome were substantially lower than group 2 without long QT syndrome (used with permission from Cuneo et al10). Only five FHRs in group 1 were below 110 bpm, the usual cutoff for defining fetal bradycardia. But when the predicted minimum FHR for gestational age was used as a reference, all except three were low. Thus fetuses are at risk for underdetection of LQTS when FHRs fall between 110 bpm and the low-normal range of approximately 120 to 135 bpm. Not all fetuses with FHRs in this range, however, have LQTS. (B) Signal-averaged complex showing cardiac time intervals in a fetus with long QT syndrome. QTc is 625 ms using Bazett formula, FHR 131 bpm sinus rhythm, T-wave alternans can be seen.

Perspectives of Fetal Monitoring Methods

Fetal arrhythmias can be diagnosed and treated. Consequently, early recognition is important, as these conditions may contribute to a disproportionate number of fetal and neonatal demise.

But not all fetal monitoring methods (newer Doppler techniques, fECG, fMCG) are widely available for clinicians. Consequently, innovative technical advancements and more readily-available inexpensive devices are required.

New device technologies meant for assessing fetal rhythm are moving through the stages of device development and testing, though none, including fMCG and fECG have full regulatory approval at this time.5,77 A major new innovation is the atomic magnetometer which is much smaller and cheaper than the SQUID magnetometer.78,79 Gaited fetal MRI, 3D/4D echo, and other technologies, once developed, may further refine diagnostics.

It will be important to reduce the “pipeline” time to market of new medical products necessary for high-quality fetal cardiac diagnostics (and therapy). The high loss of fetal life, often unexpected and unexplained, demands better cardiac rhythm diagnosis and more comprehensive disease monitoring. Challenges include the complexity of research in vulnerable subjects, and the paucity of manufactures in pregnancy and neonatal products. Interdisciplinary clinical/technical fetal research teams can facilitate this.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding

This study was funded by Deutsche Stiftung für Herzforschung F02/11, Friede-Springer HerzStiftung, AKF 307–0-0, and TÜFF Application 2156–0-0 (A. Wacker-Gussmann) and National Institutes of Health grant R01 HL063174 (R.T. Wakai, principle investigator and J.F. Strasburger, senior personnel).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Cuneo is an educational consultant for Philips Ultrasound.

References

- 1.Oudijk MA. Fetal Tachycardia: Diagnosis and Treatment and the Fetal QT Interval in Hypoxia. Vol. 216 Utrecht, The Netherlands: Dong UMC, Neoventa Medical AB, Stiefel; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dubin AM, Cuneo BF, Strasburger JF, Wakai RT, Van Hare GF, Rosenthal DN. Congenital junctional ectopic tachycardia and congenital complete atrioventricular block: a shared etiology? Heart Rhythm. 2005;2(3):313–315. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao H, Cuneo BF, Strasburger JF, Huhta JC, Gotteiner NL, Wakai RT. Electrophysiological characteristics of fetal atrioventricular block. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(1):77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuneo BF, Strasburger JF, Niksch A, Ovadia M, Wakai RT. An expanded phenotype of maternal SSA/SSB antibody-associated fetal cardiac disease. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;22(3):233–238. doi: 10.1080/14767050802488220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strasburger JF, Wakai RT. Fetal cardiac arrhythmia detection and in utero therapy. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010;7(5):277–290. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cuneo BF, Strasburger JF, Wakai RT. Magnetocardiography in the evaluation of fetuses at risk for sudden cardiac death before birth. J Electrocardiol. 2008;41(2):e1–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao H, Strasburger JF, Cuneo BF, Wakai RT. Fetal cardiac repolarization abnormalities. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98(4):491–496. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz PJ. Stillbirths, sudden infant deaths, and long-QT syndrome: puzzle or mosaic, the pieces of the Jigsaw are being fitted together. Circulation. 2004;109(24):2930–2932. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133180.77213.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rein AJ, O’Donnell C, Geva T, et al. Use of tissue velocity imaging in the diagnosis of fetal cardiac arrhythmias. Circulation. 2002;106(14):1827–1833. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000031571.92807.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cuneo BF, Strasburger JF, Yu S, et al. In utero diagnosis of long QT syndrome by magnetocardiography. Circulation. 2013;128(20):2183–2191. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.004840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiggins DL, Strasburger JF, Gotteiner NL, Cuneo B, Wakai RT. Magnetophysiologic and echocardiographic comparison of blocked atrial bigeminy and 2:1 atrioventricular block in the fetus. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10(8):1192–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kähler C, Schleussner E, Grimm B, et al. Fetal magnetocardiography in the investigation of congenital heart defects. Early Hum Dev. 2002;69(1–2):65–75. doi: 10.1016/s0378-3782(02)00041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devoe LD. Fetal ECG analysis for intrapartum electronic fetal monitoring: a review. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2011;54(1):56–65. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e31820a0ee7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vayssière C, David E, Meyer N, et al. A French randomized controlled trial of ST-segment analysis in a population with abnormal cardiotocograms during labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(3):e1–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ojala K, Vääräsmäki M, Mäkikallio K, Valkama M, Tekay A. A comparison of intrapartum automated fetal electrocardiography and conventional cardiotocography—a randomised controlled study. BJOG. 2006;113(4):419–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Westerhuis ME, Visser GH, Moons KG, et al. Cardiotocography plus ST analysis of fetal electrocardiogram compared with cardiotocography only for intrapartum monitoring: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(6):1173–1180. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181dfffd6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nii M, Hamilton RM, Fenwick L, Kingdom JC, Roman KS, Jaeggi ET. Assessment of fetal atrioventricular time intervals by tissue Doppler and pulse Doppler echocardiography: normal values and correlation with fetal electrocardiography. Heart. 2006;92(12):1831–1837. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.093070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nii M, Roman KS, Kingdom J, Redington AN, Jaeggi ET. Assessment of the evolution of normal fetal diastolic function during mid and late gestation by spectral Doppler tissue echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2006;19(12):1431–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2006.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gardiner HM, Belmar C, Pasquini L, et al. Fetal ECG: a novel predictor of atrioventricular block in anti-Ro positive pregnancies. Heart. 2007;93(11):1454–1460. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.099242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor MJ, Smith MJ, Thomas M, et al. Non-invasive fetal electrocardiography in singleton and multiple pregnancies. BJOG. 2003;110(7):668–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor MJ, Thomas MJ, Smith MJ, et al. Non-invasive intrapartum fetal ECG: preliminary report. BJOG. 2005;112(8):1016–1021. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Velayo C, Sato N, Ito T, et al. Understanding congenital heart defects through abdominal fetal electrocardiography: case reports and clinical implications. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2011;37(5):428–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dancea A, Fouron JC, Miró J, Skoll A, Lessard M. Correlation between electrocardiographic and ultrasonographic time-interval measurements in fetal lamb heart. Pediatr Res. 2000;47(3):324–328. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200003000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pasquini L, Seale AN, Belmar C, et al. PR interval: a comparison of electrical and mechanical methods in the fetus. Early Hum Dev. 2007;83(4):231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2006.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horigome H, Takahashi MI, Asaka M, Shigemitsu S, Kandori A, Tsukada K. Magnetocardiographic determination of the developmental changes in PQ, QRS and QT intervals in the foetus. Acta Paediatr. 2000;89(1):64–67. doi: 10.1080/080352500750029086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leuthold A, Wakai RT, Martin CB. Noninvasive in utero assessment of PR and QRS intervals from the fetal magnetocardiogram. Early Hum Dev. 1999;54(3):235–243. doi: 10.1016/s0378-3782(98)00100-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lowery CL, Campbell JQ, Wilson JD, et al. Noninvasive antepartum recording of fetal S-T segment with a newly developed 151-channel magnetic sensor system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(6):1491–1496. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.367. discussion 1496–1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Leeuwen P, Schiermeier S, Lange S, et al. Gender-related changes in magnetocardiographically determined fetal cardiac time intervals in intrauterine growth retardation. Pediatr Res. 2006;59(6):820–824. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000219300.95218.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Comani S, Alleva G. Fetal cardiac time intervals estimated on fetal magnetocardiograms: single cycle analysis versus average beat inspection. Physiol Meas. 2007;28(1):49–60. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/28/1/005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horigome H, Ogata K, Kandori A, et al. Standardization of the PQRST waveform and analysis of arrhythmias in the fetus using vector magnetocardiography. Pediatr Res. 2006;59(1):121–125. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000190578.81426.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kähler C, Schleussner E, Grimm B, et al. Fetal magnetocardiography: development of the fetal cardiac time intervals. Prenat Diagn. 2002;22(5):408–414. doi: 10.1002/pd.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quinn A, Weir A, Shahani U, Bain R, Maas P, Donaldson G. Antenatal fetal magnetocardiography: a new method for fetal surveillance? Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;101(10):866–870. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1994.tb13547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stinstra J, Golbach E, van Leeuwen P, et al. Multicentre study of fetal cardiac time intervals using magnetocardiography. BJOG. 2002;109(11):1235–1243. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-0528.2002.01057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Leeuwen P, Lange S, Klein A, Geue D, Grönemeyer DH. Dependency of magnetocardiographically determined fetal cardiac time intervals on gestational age, gender and postnatal biometrics in healthy pregnancies. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2004;4(1):6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-4-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Leeuwen P, Lange S, Klein A, et al. Reproducibility and reliability of fetal cardiac time intervals using magnetocardiography. Physiol Meas. 2004;25(2):539–552. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/25/2/011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Leeuwen P, Lange S, Geue D, Grönemeyer D. Heart rate variability in the fetus: a comparison of measures. Biomed Tech (Berl) 2007;52(1):61–65. doi: 10.1515/BMT.2007.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wakai RT, Leuthold AC, Martin CB. Atrial and ventricular fetal heart rate patterns in isolated congenital complete heart block detected by magnetocardiography. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179(1):258–260. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70282-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wakai RT, Wang M, Martin CB. Fetal magnetocardiogram amplitude-modulation associated with respiratory sinus arrhythmia and fetal rate acceleration. Physiol Meas. 1995;16:49–54. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/16/1/006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cuneo BF, Ovadia M, Strasburger JF, et al. Prenatal diagnosis and in utero treatment of torsades de pointes associated with congenital long QT syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91(11):1395–1398. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00343-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fukushima A, Nakai K, Matsumoto A, Strasburger J, Sugiyama T. Prenatal diagnosis of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia using 64-channel magnetocardiography. Heart Vessels. 2010;25(3):270–273. doi: 10.1007/s00380-009-1195-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hamada H, Horigome H, Asaka M, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of long QT syndrome using fetal magnetocardiography. Prenat Diagn. 1999;19(7):677–680. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0223(199907)19:7<677::aid-pd597>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Horigome H, Iwashita H, Yoshinaga M, Shimizu W. Magnetocardiographic demonstration of torsade de pointes in a fetus with congenital long QT syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19(3):334–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.01026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Menéndez T, Achenbach S, Beinder E, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of QT prolongation by magnetocardiography. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2000;23(8):1305–1307. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2000.tb00950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cuneo BF, Zhao H, Strasburger JF, Ovadia M, Huhta JC, Wakai RT. Atrial and ventricular rate response and patterns of heart rate acceleration during maternal-fetal terbutaline treatment of fetal complete heart block. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(4):661–665. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.03.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Z, Strasburger JF, Cuneo BF, Gotteiner NL, Wakai RT. Giant fetal magnetocardiogram P waves in congenital atrioventricular block: a marker of cardiovascular compensation? Circulation. 2004;110(15):2097–2101. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000144302.30928.AA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Leeuwen P, Hailer B, Bader W, Geissler J, Trowitzsch E, Grönemeyer DH. Magnetocardiography in the diagnosis of fetal arrhythmia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106(11):1200–1208. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1999.tb08149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wakai RT, Lengle JM, Leuthold AC. Transmission of electric and magnetic foetal cardiac signals in a case of ectopia cordis: the dominant role of the vernix. caseosa Phys Med Biol. 2000;45(7):1989–1995. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/45/7/320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Das B, Cuneo BF, Ovadia M, Strasburger JF, Johnsrude C, Wakai RT. Magnetocardiography-guided management of an unusual case of isoimmune complete atrioventricular block complicated by ventricular tachycardia. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2008;24(3):282–285. doi: 10.1159/000151677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wakai RT, Strasburger JF, Li Z, Deal BJ, Gotteiner NL. Magnetocardiographic rhythm patterns at initiation and termination of fetal supraventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2003;107(2):307–312. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000043801.92580.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peters C, Wacker-Gussmann A, Strasburger JF, et al. Electrophysiologic features of fetal ventricular aneurysms and diverticula. Cardiol Young. 2013;23(Suppl 1):S73. doi: 10.1002/pd.4501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wacker-Gussmann A, Strasburger JF, Cuneo B, Wiggins D, Gotteiner N, Wakai RT. Fetal arrhythmias associated with cardiac rhabdomyomas. Heart Rhythm. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Crotti L, Tester DJ, White WM, et al. Long QT syndrome-associated mutations in intrauterine fetal death. JAMA. 2013;309(14):1473–1482. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.3219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eliasson H, Sonesson S-E, Sharland G, et al. Isolated atrioventricular block in the fetus/clinical perspective. Circulation. 2011;124(18):1919–1926. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.041970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cuneo BF, Strasburger JF, Wakai RT, Ovadia M. Conduction system disease in fetuses evaluated for irregular cardiac rhythm. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2006;21(3):307–313. doi: 10.1159/000091362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mitchell JL, Cuneo BF, Etheridge SP, Horigome H, Weng HY, Benson DW. Fetal heart rate predictors of long QT syndrome. Circulation. 2012;126(23):2688–2695. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.114132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Acherman RJ, Evans WN, Luna CF, et al. Fetal bradycardia. A practical approach. Fetal Matern Med Rev. 2007;18(3):225–255. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Buyon JP, Clancy RM, Friedman DM. Cardiac manifestations of neonatal lupus erythematosus: guidelines to management, integrating clues from the bench and bedside. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2009;5(3):139–148. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Izmirly PM, Saxena A, Kim MY, et al. Maternal and fetal factors associated with mortality and morbidity in a multi-racial/ethnic registry of anti-SSA/Ro-associated cardiac neonatal lupus. Circulation. 2011;124(18):1927–1935. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.033894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Trucco SM, Jaeggi E, Cuneo B, et al. Use of intravenous gamma globulin and corticosteroids in the treatment of maternal autoantibody-mediated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(6):715–723. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jaeggi ET, Silverman ED, Laskin C, Kingdom J, Golding F, Weber R. Prolongation of the atrioventricular conduction in fetuses exposed to maternal anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibodies did not predict progressive heart block. A prospective observational study on the effects of maternal antibodies on 165 fetuses. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(13):1487–1492. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baruteau A-E Study AFM. Non immune isolated atrioventricular block in childhood: a French multicentric study. Heart Rhythm J. 2009;S39:AB19–AB31. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Groves AM, Allan LD, Rosenthal E. Therapeutic trial of sympathomimetics in three cases of complete heart block in the fetus. Circulation. 1995;92(12):3394–3396. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.12.3394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jaeggi ET, Fouron JC, Silverman ED, Ryan G, Smallhorn J, Hornberger LK. Transplacental fetal treatment improves the outcome of prenatally diagnosed complete atrioventricular block without structural heart disease. Circulation. 2004;110(12):1542–1548. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000142046.58632.3A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ambrosi A, Salomonsson S, Eliasson H, et al. Development of heart block in children of SSA/SSB-autoantibody-positive women is associated with maternal age and displays a season-of-birth pattern. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(3):334–340. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jaeggi ET, Carvalho JS, De Groot E, et al. Comparison of transplacental treatment of fetal supraventricular tachyarrhythmias with digoxin, flecainide, and sotalol: results of a nonrandomized multicenter study. Circulation. 2011;124(16):1747–1754. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.026120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Parilla BV, Strasburger JF, Socol ML. Fetal supraventricular tachycardia complicated by hydrops fetalis: a role for direct fetal intramuscular therapy. Am J Perinatol. 1996;13(8):483–486. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-994432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.van der Heijden LB, Oudijk MA, Manten GT, ter Heide H, Pistorius L, Freund MW. Sotalol as first-line treatment for fetal tachycardia and neonatal follow-up. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;42(3):285–293. doi: 10.1002/uog.12390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jaeggi ET, Nii M. Fetal brady- and tachyarrhythmias: new and accepted diagnostic and treatment methods. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2005;10(6):504–514. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Krapp M, Kohl T, Simpson JM, Sharland GK, Katalinic A, Gembruch U. Review of diagnosis, treatment, and outcome of fetal atrial flutter compared with supraventricular tachycardia. Heart. 2003;89(8):913–917. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.8.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Oudijk MA, Michon MM, Kleinman CS, et al. Sotalol in the treatment of fetal dysrhythmias. Circulation. 2000;101(23):2721–2726. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.23.2721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Srinivasan S, Strasburger J. Overview of fetal arrhythmias. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20(5):522–531. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32830f93ec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Naheed ZJ, Strasburger JF, Deal BJ, Benson DW, Jr, Gidding SS. Fetal tachycardia: mechanisms and predictors of hydrops fetalis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27(7):1736–1740. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(96)00054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Strasburger JF. Re: Sotalol as first-line treatment for fetal tachycardia and neonatal follow-up. L. B. van der Heijden, M. A. Oudijk, G. Manten, H. ter Heide, L. Pistorius and M. W. Freund. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2013; 42: 285-293. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;42:285–293. doi: 10.1002/uog.12390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;42(3):254–255. doi: 10.1002/uog.12576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Collins KK, Van Hare GF, Kertesz NJ, et al. Pediatric nonpostoperative junctional ectopic tachycardia medical management and interventional therapies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(8):690–697. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Horigome H, Nagashima M, Sumitomo N, et al. Clinical characteristics and genetic background of congenital long-QT syndrome diagnosed in fetal, neonatal, and infantile life: a nationwide questionnaire survey in Japan. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2010;3(1):10–17. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.882159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Simpson JM, Maxwell D, Rosenthal E, Gill H. Fetal ventricular tachycardia secondary to long QT syndrome treated with maternal intravenous magnesium: case report and review of the literature. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34(4):475–480. doi: 10.1002/uog.6433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kominis IK, Kornack TW, Allred JC, Romalis MV. A subfemtotesla multichannel atomic magnetometer. Nature. 2003;422(6932):596–599. doi: 10.1038/nature01484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shah VK, Wakai RT. A compact, high performance atomic magnetometer for biomedical applications. Phys Med Biol. 2013;58(22):8153–8161. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/58/22/8153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wyllie R, Kauer M, Smetana GS, Wakai RT, Walker TG. Magnetocardiography with a modular spin-exchange relaxation-free atomic magnetometer array. Phys Med Biol. 2012;57(9):2619–2632. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/57/9/2619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]