Abstract

Background

Limited data is available on how the timing and setting of palliative care referral can affect end-of-life care. In this retrospective cohort study, we examined how the timing and setting of palliative care (PC) referral were associated with the quality of end-of-life care.

Methods

All adult patients residing in the Houston area who died of advanced cancer between 9/1/2009 and 2/28/2010 and had a PC consultation were included. We retrieved data on PC referral and quality of end-of-life care indicators.

Results

Among 366 decedents, 120 (33%) had early PC referral (>3 months before death) and 169 (46%) were first seen as outpatients. Earlier PC referral was associated with fewer emergency room visits (39% vs. 68%, P<0.001), hospitalizations (48% vs. 81%, P<0.003), and hospital deaths (17% vs. 31%, P=0.004) in the last 30 days of life. Similarly, outpatient PC referral was associated with fewer emergency room visits (48% vs. 68%, P<0.001), hospital admissions (52% vs. 86%, P<0.001), hospital deaths (18% vs. 34%, P=0.001) and intensive care unit admissions (4% vs. 14%, P=0.001). In multivariate analysis, outpatient PC referral (odds ratio [OR]=0.42, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.28-0.66; P<0.001) was independently associated with less aggressive end-of-life care. Male sex (OR=1.63, 95%CI 1.06-2.50; P=0.03) and hematologic malignancy (OR=2.57, 95%CI 1.18-5.59; P=0.02) were associated with more aggressive end-of-life care.

Conclusion

Patients referred to outpatient PC had improved end-of-life care compared to inpatient PC. Our findings support the need to increase the availability of PC clinics and to streamline the process of early referral.

Keywords: Chemotherapeutic Agents, Inpatients, Neoplasms, Outpatients, Palliative Care, Quality of Care

INTRODUCTION

Palliative care is an interprofessional discipline that aims at improving the quality of life of patients with advanced diseases and their families by addressing their symptom concerns and communication and decision making needs.1 A growing number of studies suggest that palliative care has a positive effect on many clinical outcomes, including symptom distress, quality of life, satisfaction and survival.2-4

The quality of care at the end-of-life represents another important outcome. Aggressive medical interventions in the last weeks of life, such as emergency room (ER) visits, hospital and intensive care unit (ICU) admission and death, and chemotherapy administration are generally considered as indicators of poor quality of care.5, 6 These indicators have now been incorporated into the National Quality Forum (NQF) and American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Quality Oncology Practice Initiative as benchmarks to assess the quality of end-of-life care.7, 8

A randomized controlled trial of outpatient palliative care referral compared to routine oncologic care revealed that palliative care was effective in improving end-of-life care;4 however, it is not clear whether inpatient palliative care also offers similar benefit. No study to date has specifically examined how the timing and setting of palliative care referral are associated with these end-of-life care indicators. Although early access to palliative care occurs primarily in the outpatient setting, a large proportion of US cancer centers do not have outpatient palliative care clinics.9 Therefore, a majority of referrals to palliative care occurs only in the inpatient setting and late in the disease process.

A better understanding of how the timing and setting of palliative care referral are associated with the quality of end-of-life care may help guide our clinical practice. In this retrospective cohort study, we examined how the timing and setting of palliative care referral were associated with the quality of end-of-life care. We hypothesized that earlier involvement of palliative care in the outpatient setting is associated with positive end-of-life care outcomes.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Setting and Eligibility Criteria

The Institutional Review Board at MD Anderson Cancer Center reviewed and approved this retrospective study, and waived the requirement of informed consent. This is a secondary analysis of a study examining the pattern of palliative care referral at our institution.10 Briefly, we included all adult patients in the Houston area who died of advanced cancer between 9/1/2009 and 2/28/2010, who had received a palliative care referral, and had contact with our cancer center within the last 3 months of life. Patients who transferred care to outside oncologists, relocated to another city or lost to followup were excluded. These criteria were specifically chosen such that we were able to reliably capture their medical information in the last months of life.10

The Supportive Care Center operated 5 days per week and saw approximately 25 patients per day. It was staffed by 2 palliative care specialists who were supported by an interdisciplinary team of nurses and a social worker. Upon completion of a standardized comprehensive assessment, patients received personalized recommendations addressing their symptom distress, psychosocial, communication and decision-making needs.11 Patients referred to the palliative care mobile team in the inpatient setting were managed similarly by the same team of palliative care specialists following common clinical pathways.

Data Collection

The data retrieval process has been documented previously.10, 12 Briefly, we collected baseline demographics and the timing of palliative care referral in relation to death. We also determined whether patients’ first palliative care consultation was conducted in the outpatient or inpatient setting, independent of the timing of referral.

We documented the presence or absence of quality of care indicators in the last 30 days of life based on the published literature.13 These included any ER visit, ≥2 ER visits, any hospital admission, ≥2 hospital admissions, >14 days of hospitalization, hospital death, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and ICU death. These data were retrieved from our institutional database, and further verified by chart review to ensure accuracy of data collection. We also manually reviewed the last date of administration of systemic cancer therapy, and determined the proportion who received these treatments in the last 14 and 30 days of life as documented previously.12

Statistical Analysis

We summarized the baseline demographics using descriptive statistics, including means, medians, ranges, interquartile range and frequencies.

We compared the demographics and quality of care indicators between patients who had an outpatient palliative care consultation to those with an inpatient palliative care consultation using the t-test for continuous, normally distributed variables (e.g. age), the Mann-Whitney test for continuous, non-parametric variables (e.g. duration between advanced cancer diagnosis and death), the Chi-square test or the Fisher exact test for categorical variables (e.g. proportion of patients with hospital death). We compared the quality of care between early (>3 months between first palliative care consultation and death) and late (≤3 months) palliative care referral. This cutoff was chosen because the median time from referral to death to the outpatient clinic was approximately 3 months. A similar analysis was also conducted using the hospice referral criteria of 6 months as a cutoff.

We also compared between outpatient and inpatient palliative care consultations. The inpatient consultation group was a good control because these patients had similar characteristics and received similar interventions from the same team of palliative care professionals as those who were first seen at the outpatient palliative care clinic. Importantly, the setting of referral is conceptually distinct from the outcome of interest (i.e. aggressiveness of end-of-life care in the last 30 days of life). This is because when clinicians make a palliative care referral, they cannot predict with accuracy that the patient will die in the next 30 days.14 A palliative care referral is often triggered by symptom distress rather than prognosis. Inpatient palliative care referral is operationally different from our outcome. Inpatient palliative care referral involves only one hospital visit which could occur any time before death (median 0.7 month, range 0-17.7 month). In contrast, the outcomes reported here are established by the NQF and ASCO, and have a higher threshold in terms of severity and timing than a single hospitalization.

A composite aggressive end-of-life care score has previously been reported,13, 15 with one point for each of the following 6 indicators in the last 30 days of life: ≥2 ER visits, ≥2 hospital admissions, >14 days of hospitalization, an ICU admission, death in a hospital, and use of chemotherapy. The total score ranged from 0 to 6, with a higher score indicating more aggressive care. We used a multivariate logistic regression model with backward elimination to identify factors associated with the presence of any of the above 6 indicators. Variables included in the model were age, sex, race, marital status, cancer diagnosis (hematologic or solid tumors), setting of palliative care referral (outpatient or inpatient), timing of palliative care referral (≤3 months or >3 months), time between advanced cancer diagnosis and death, and percentage of advanced cancer diagnosis with palliative care involvement. The dataset was complete without missing data.

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS version 19.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois) software was used for statistical analysis. A P-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

366 decedents met the eligibility criteria and were included in this study; 169 (46%) had their first palliative care consultation in the outpatient setting, and 199 (54%) in the inpatient setting. The median age was 61 (range 23-87). A majority were female (192, 52%), Caucasian (N=228, 62%), and married (N=241, 66%). Table 1 shows the baseline patient characteristics at first palliative care consultation, with no significant differences between outpatient and inpatient consultations except for cancer diagnosis (P=0.003).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics (N=366)

| Patient Characteristics | Inpatient Referral N=199 (%)1 | Outpatient Referral N=169 (%)1 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (range) | 59 (23-86) | 61 (25-87) | 0.112 |

| Female sex | 110 (55) | 82 (49) | 0.253 |

| Race | |||

| White | 117 (57) | 111 (62) | 0.494 |

| Black | 48 (23) | 34 (19) | |

| Hispanic | 31 (15) | 22 (12) | |

| Asian | 8 (4) | 11 (6) | |

| Others | 3 (1) | 1 (1) | |

| Married | 129 (65) | 112 (67) | 0.663 |

| Education | |||

| High school or less | 73 (37) | 61 (37) | 0.193 |

| College education | 63 (32) | 61 (37) | |

| Post graduate education | 10 (5) | 14 (8) | |

| Not available | 53 (27) | 31 (19) | |

| Cancer type | |||

| Breast | 21 (11) | 18 (11) | 0.0034 |

| Gastrointestinal | 53 (27) | 37 (22) | |

| Genitourinary | 16 (8) | 17 (10) | |

| Gynecologic | 21 (11) | 19 (11) | |

| Head and neck | 4 (2) | 18 (11) | |

| Hematologic | 29 (15) | 8 (5) | |

| Other | 18 (9) | 16 (10) | |

| Respiratory | 37 (19) | 34 (20) | |

| Months between advanced cancer diagnosis and death, median (interquartile range) | 11.7 (4.7-25.8) | 19.6 (10.3-31.3) | <0.0015 |

| Months between advanced cancer diagnosis and palliative care consultation, median (interquartile range) | 10.6 (3.3-24.3) | 12.0 (4.6-24.5) | 0.405 |

| Months between palliative care consultation and death, median (interquartile range) | 0.7 (0.2-1.6) | 3.7 (1.6-9.6) | <0.0015 |

| Percent of advanced cancer diagnosis with palliative care involvement, median (interquartile range) | 6.3 (2.3-22.6) | 24.2 (7.8-58.3) | <0.0015 |

Column percentage unless otherwise specified

Student t test

Chi square test

Fisher's exact test

Mann Whitney test

Quality of End-of-Life Care by Timing of Palliative Care Referral

Compared to late referrals (≤3 months before death), early palliative care referral (>3 months before death) was associated with significantly fewer ER visits (P<0.001), hospital admissions (P<0.001) and hospital death (P=0.004) in the last 30 days of life (Table 2). The composite aggressive end-of-life care score was also significantly lower in the early referral group compared to late referral group (median 0 vs. 1, P<0.001). The findings are similar using 6 months as a cutoff for timing of palliative care referral (Table 2).

Table 2.

Quality of End-of-life Care by Timing of Palliative Care Referral

| Duration between Palliative Care Referral and Death | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | ≤3 m N=246 (%)1 | >3 m N=120 (%)1 | P-value | ≤6 m N=298 (%)1 | >6 m N=68 (%)1 | P-value |

| Within last 30 days of life | ||||||

| Any emergency room visit | 168 (68) | 47 (39) | <0.0013 | 187 (63) | 28 (41) | 0.0023 |

| 2 or more emergency room visits | 57 (23) | 12 (10) | 0.0033 | 63 (21) | 6 (9) | 0.023 |

| Any hospital admission | 200 (81) | 58 (48) | <0.0013 | 223 (75) | 35 (51) | <0.0013 |

| 2 or more hospital admissions | 52 (21) | 12 (10) | 0.013 | 55 (18) | 9 (13) | 0.383 |

| More than 14 days of hospitalization | 40 (16) | 14 (12) | 0.283 | 47 (16) | 7 (10) | 0.273 |

| Hospital death | 77 (31) | 20 (17) | 0.0043 | 85 (29) | 12 (18) | 0.073 |

| Any ICU admission | 28 (11) | 7 (6) | 0.133 | 30 (10) | 5 (7) | 0.654 |

| ICU death | 10 (4) | 3 (3) | 0.564 | 11 (4) | 2 (3) | >0.994 |

| Chemotherapy use | 42 (17) | 17 (14) | 0.553 | 50 (17) | 9 (13) | 0.593 |

| Targeted therapy use | 36 (15) | 13 (11) | 0.333 | 39 (13) | 10 (15) | 0.843 |

| Chemotherapy and targeted agent use | 67 (27) | 29 (24) | 0.613 | 77 (26) | 19 (28) | 0.763 |

| Within last 14 days of life | ||||||

| Chemotherapy use | 17 (7) | 5 (4) | 0.364 | 19 (6) | 3 (4) | 0.784 |

| Targeted therapy use | 11 (4) | 5 (4) | >0.993 | 13 (4) | 3 (4) | >0.994 |

| Chemotherapy and targeted agent use | 23 (9) | 10 (8) | 0.853 | 27 (9) | 6 (9) | >0.994 |

| Aggressive EOL care score | ||||||

| 0 | 111 (45) | 78 (65) | 0.0174 | 146 (49) | 43 (63) | 0.424 |

| 1 | 52 (21) | 19 (16) | 59 (20) | 12 (18) | ||

| 2 | 32 (13) | 11 (9) | 37 (12) | 6 (9) | ||

| 3 | 29 (12) | 8 (7) | 33 (11) | 4 (6) | ||

| 4 | 17 (7) | 3 (3) | 17 (6) | 3 (4) | ||

| 5 | 5 (2) | 1 (1) | 6 (2) | 0 (0) | ||

| Median score (IQR) | 1 (0-2) | 0 (0-1) | <0.0015 | 1 (0-2) | 0 (0-1) | 0.025 |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range

Column percentage unless otherwise specified

2 Student t test

Chi square test

Fisher's exact test

Mann Whitney test

Quality of End-of-Life Care by Setting of Palliative Care Referral

Table 3 shows that patients with outpatient referral had improved quality of end-of-life care compared to those who were first referred as inpatients. Specifically, outpatient referral was associated with significantly fewer ER visits (P<0.001), hospital admissions (P<0.001), hospital death (P=0.001), ICU admissions (P=0.001), and shorter duration of hospital stay (P=0.002) in the last 30 days of life. In contrast, the proportion of patients who received chemotherapy and targeted therapy in the last 14 or 30 days of life did not differ significantly between the two groups. The composite aggressive end-of-life care score was also significantly lower in the outpatient referral group (median 0 vs. 1, P<0.001).

Table 3.

Quality of End-of-life Care by Setting of Palliative Care Referral

| Patient Characteristics | Inpatient Referral N=199 (%)1 | Outpatient Referral N=169 (%)1 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Within the last 30 days of life | |||

| Any emergency room visit | 135 (68) | 80 (48) | <0.0012 |

| 2 or more emergency room visits | 51 (26) | 18 (11) | <0.0012 |

| Any hospital admission | 171 (86) | 87 (52) | <0.0012 |

| 2 or more hospital admissions | 47 (24) | 17 (10) | 0.0012 |

| More than 14 days of hospitalization | 40 (20) | 14 (8) | 0.0022 |

| Hospital death | 67 (34) | 30 (18) | 0.0012 |

| Any ICU admission | 28 (14) | 7 (4) | 0.0013 |

| ICU death | 10 (5) | 3 (2) | 0.153 |

| Chemotherapy use | 34 (17) | 25 (15) | 0.672 |

| Targeted therapy use | 29 (15) | 20 (12) | 0.542 |

| Chemotherapy and targeted agent use | 55 (28) | 41 (25) | 0.552 |

| Median length of hospitalization in last 30 days of life | 9 (5-14) | 8 (3-11) | 0.014 |

| Within the last 14 days of life | |||

| Chemotherapy use | 14 (7) | 8 (5) | 0.382 |

| Targeted therapy use | 9 (5) | 7 (4) | >0.992 |

| Chemotherapy and targeted agent use | 20 (10) | 13 (8) | 0.472 |

| Composite aggressive EOL care score | |||

| 0 | 83 (42) | 106 (63) | <0.0013 |

| 1 | 38 (19) | 33 (20) | |

| 2 | 31 (16) | 12 (7) | |

| 3 | 26 (13) | 11 (7) | |

| 4 | 16 (8) | 4 (2) | |

| 5 | 5 (3) | 1 (1) | |

| Median score (IQR) | 1 (0-2) | 0 (0-1) | <0.0014 |

Column percentage unless otherwise specified

Chi square test

Fisher's exact test

Mann Whitney test

Factors associated with Aggressive End-of-Life Care

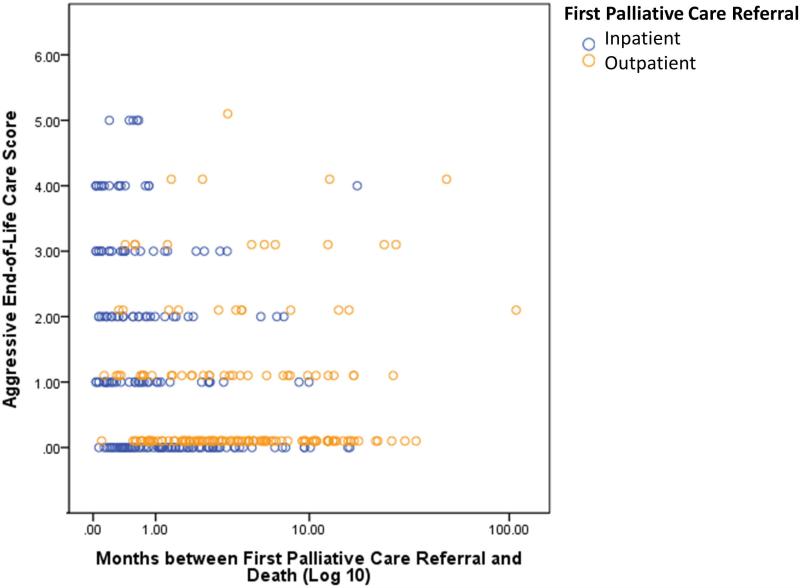

As shown in Figure 1, outpatient palliative care referrals occurred earlier than inpatient referrals. Moreover, outpatient referrals and earlier referrals were associated with lower aggressive end-of-life care scores. In multivariate regression analysis, palliative care outpatient referral (odds ratio [OR]=0.42, P<0.001) was associated with less aggressive end-of-life care, while male sex (OR=1.63, P=0.03) and hematologic malignancy (OR=2.57, P=0.02) were independently associated with more aggressive end-of-life care (Table 4).

Figure 1. Association between Aggressive End-of-Life Care and the Timing and Setting of Palliative Care Referral.

The aggressive end-of-life care score is a previously published composite score with one point assigned for each of the following 6 indicators in the last 30 days of life: two or more emergency room visits, two or more hospital admissions, more than 14 days of hospitalization, an ICU admission, death in a hospital, and use of chemotherapy.13 The total score ranged from 0 to 6, with a higher score indicating more aggressive care. As shown in this scatter plot, outpatient consultations (orange circles) occurred earlier in the disease trajectory than inpatient consultations (blue circles), and were more likely to be associated with less aggressive end-of-life care.

Table 4.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis for Quality of End-of-Life Care Indicator1

| Variable | Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 1.63 (1.06-2.50) | 0.027 |

| Hematologic malignancies | 2.57 (1.18-5.59) | 0.018 |

| Palliative care outpatient referral | 0.42 (0.28-0.66) | <0.001 |

Variables entered in the logistic regression model with backward selection were age, sex, race, marital status, cancer diagnosis (hematologic or solid tumors), setting of palliative care referral (outpatient or inpatient), timing of palliative care referral (≤3 months or >3 months), time between advanced cancer diagnosis and death, and percentage of advanced cancer diagnosis with palliative care involvement.

DISCUSSION

We found that almost 50% of decedents seen by the palliative care team at our cancer center had at least one aggressive end-of-life care indicator. Importantly, patients who were referred to palliative care earlier and as outpatients had improved quality of care compared to those who were referred late and as inpatients, with lower proportion of patients having ER visits, hospitalization and ICU admissions. Outpatient palliative care referral remained an independent factor for improved end-of-life care in multivariate analysis. Our findings support the need to increase outpatient palliative care services in cancer centers and to improve the process of early palliative care referral.

We found that a large proportion of our patients received aggressive care at the end-of-life. How can we improve these outcomes? The Coping with Cancer Study showed that patients who reported having had end-of-life discussions had improved medical utilization in the last week of life, such as decreased ICU admission, ventilator use, resuscitation, and increased hospice referral.16 Importantly, Mack et al. showed that end-of-life discussions that occurred earlier and in the outpatient setting were associated with improved end-of-life outcomes.17 The palliative care team plays a key role facilitating such discussions. Indeed, a landmark randomized controlled trial of palliative care as an intervention demonstrated improved documentation of resuscitation preferences and less aggressive end-of-life care.4 Our current study expands on this knowledge by demonstrating that early and outpatient involvement of palliative care is associated with improved end-of-life outcomes compared to late and inpatient referrals.

Our observation that early and outpatient palliative care is associated with improved end-of-life outcomes can potentially be explained by multiple mechanisms. First, early involvement allows patients to develop a longitudinal therapeutic relationship with the palliative care team over multiple clinic visits. This may facilitate many important discussions over time, such as goals of care and advance care planning, which may help to minimize aggressive interventions at the end-of-life. Second, early involvement allows detection of symptoms such as pain and depression through routine screening, early intervention and patient education, thus reducing the risk of symptom crisis necessitating ER visits and hospital stays, which are particularly common at the end-of-life. Third, palliative care can improve access to psychosocial services and introduce resources to the home setting, including hospice referral when appropriate, thus reducing the need for urgent acute care. Finally, oncologists who refer patients to palliative care early in the disease trajectory may be more “palliphilic”, and more involved in goals of care discussions with their own patients. Prospective studies are needed to determine the cause-effect relationships.

It is important to note that inpatient palliative care services also serve important functions. Studies by our group and others have consistently shown that inpatient palliative care consultation teams can successfully reduce physical and psychological symptom burden and assist with transition of care.18, 19 Acute palliative care units may even be more effective than inpatient consultation teams at relieving patient and caregiver distress.20-22 However, it would be unreasonable to expect a large impact on quality of end-of-care from the inpatient palliative care teams when they are involved for the first time weeks or days before death and when many of the catastrophic complications requiring hospitalization have already occurred.

Despite the growing evidence supporting the effectiveness of palliative outpatient clinics, only 59% of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) designated cancer centers and 22% of non-NCI designated cancer centers reported having such clinics.9 This is in contrast to the almost ubiquitous presence of inpatient palliative care consultation teams. Even with palliative care clinic available, only 46% had their first palliative care visit in the outpatient setting at our center.10 Given that oncologic care is predominantly delivered in the ambulatory setting, outpatient palliative care is an ideal setting for cancer patients to access comprehensive symptom management and psychosocial care. ASCO recently published a position paper based on the findings of multiple randomized controlled trials supporting early integration of palliative care in the disease trajectory for patients with advanced cancer and the role of outpatient palliative care clinics.23, 24 Currently, no consensus list of indicators for outpatient palliative care referral exists. Further research is necessary to examine potential barriers for outpatient palliative care referrals and to develop standardized criteria for making such referrals. In addition to increasing the availability of outpatient palliative care clinics, clinical care pathways and increased collaboration are necessary to improve patient access to palliative care.11, 25

We also found that male sex was associated with more aggressive end-of-life care. This findings is consistent with multiple studies demonstrating that women received fewer medical interventions at the end-of-life relative to men.13, 26 Possible explanations include development of terminal illness at an older age among women, differences in acute/chronic medical conditions, and differential treatment preferences and care delivery.27

This study has several limitations. First, the data were based on patients seen at our tertiary care cancer center, who are likely to have different characteristics compared to those seen at community setting, and may receive more cancer treatments for their advanced stage disease. This may limit the generalizability of our study. Prospective studies examining the outcomes of palliative care clinics both in the tertiary and community settings are warranted. Second, our sample size was relatively small. In contrast to population based studies, we were able to verify our data with higher accuracy and include non-Medicare patients. Third, we limited our analysis only to patients who received palliative care to ensure that we can compare between two groups who had similar needs. Patients who were referred to palliative care often have greater symptom distress, and may be more likely to need acute care than patients not referred to palliative care. Fourth, we only retrieved outcomes data at our institution. It is possible that some patients received their acute care outside of our institution in the last month of life; however, this is believed to represent a minority. In our cohort, 293/366 (80%) patients had their last visit within the last 30 days of life. The median time from last institutional followup to death was 11 days (interquartile range 4-25 days). Fifth, because of the retrospective nature of this study, we were not able to capture other factors that may influence quality of end-of-life care. For instance, oncologists who refer patients earlier to palliative care may also be more likely to focus on quality of care and discuss goals of care with their patients. ASCO Quality Oncology Practice Initiative included “referral to palliative care” as one of the indicators to assess care at the end-of-life. Based on our findings, referral to outpatient palliative care may be a more appropriate marker.

Our study adds to the body of knowledge by demonstrating that outpatient palliative care consultation is associated with improved quality of end-of-life care compared to inpatient palliative care consultation, independent of cancer diagnosis and other patient characteristics. Our findings support the role of outpatient palliative care clinics in cancer centers, and the need to address both the proportion and timing of palliative care referral.

Acknowledgments

Funding support: Dr. Bruera is supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants RO1NR010162-01A1, RO1CA122292-01, and RO1CA124481-01. Dr. Hui is supported in part by an institutional startup fund. This study is also supported by the MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant (CA 016672). The sponsors had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or writing of the report.

Footnotes

Financial disclosures: No relevant disclosure for all authors

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO [March 21, 2013];Definition of Palliative Care. Available from URL: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/

- 2.Higginson IJ, Finlay IG, Goodwin DM, Hood K, Edwards AG, Cook A, et al. Is there evidence that palliative care teams alter end-of-life experiences of patients and their caregivers? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25(2):150–68. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00599-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimmermann C, Riechelmann R, Krzyzanowska M, Rodin G, Tannock I. Effectiveness of specialized palliative care: a systematic review. JAMA. 2008;299(14):1698–709. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.14.1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Earle CC, Landrum MB, Souza JM, Neville BA, Weeks JC, Ayanian JZ. Aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life: is it a quality-of-care issue? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(23):3860–66. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Earle CC, Park ER, Lai B, Weeks JC, Ayanian JZ, Block S. Identifying potential indicators of the quality of end-of-life cancer care from administrative data. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(6):1133–38. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McNiff KK, Neuss MN, Jacobson JO, Eisenberg PD, Kadlubek P, Simone JV. Measuring supportive care in medical oncology practice: lessons learned from the quality oncology practice initiative. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(23):3832–37. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.8674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative C Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. (Second Edition) 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hui D, Elsayem A, De la Cruz M, Berger A, Zhukovsky DS, Palla S, et al. Availability and integration of palliative care at US cancer centers. JAMA. 2010;303(11):1054–61. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hui D, Kim SH, Kwon JH, Tanco KC, Zhang T, Kang JH, et al. Access to palliative care among patients treated at a comprehensive cancer center. Oncologist. 2012;17(12):1574–80. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruera E, Hui D. Conceptual models for integrating palliative care at cancer centers. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(11):1261–9. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hui D, Karuturi MS, Tanco KC, Kwon JH, Kim SH, Zhang T, et al. Targeted Agent Use in Cancer Patients at the End of Life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang ST, Wu SC, Hung YN, Chen JS, Huang EW, Liu TW. Determinants of aggressive end-of-life care for Taiwanese cancer decedents, 2001 to 2006. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(27):4613–18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hui D, Kilgore K, Nguyen L, Hall S, Fajardo J, Cox-Miller TP, et al. The accuracy of probabilistic versus temporal clinician prediction of survival for patients with advanced cancer: a preliminary report. The Oncologist. 2011;16(11):1642–8. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hui D, Didwaniya N, Vidal M, Shin SH, Chisholm G, Roquemore J, et al. Quality of End-of-Life Care in Patients with Hematologic Malignancies: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1002/cncr.28614. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, Mack JW, Trice E, Balboni T, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mack JW, Cronin A, Keating NL, Taback N, Huskamp HA, Malin JL, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussion characteristics and care received near death: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(35):4387–95. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.6055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higginson IJ, Finlay I, Goodwin DM, Cook AM, Hood K, Edwards AG, et al. Do hospital-based palliative teams improve care for patients or families at the end of life? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;23(2):96–106. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yennurajalingam S, Urbauer DL, Casper KL, Reyes-Gibby CC, Chacko R, Poulter V, et al. Impact of a Palliative Care Consultation Team on Cancer-Related Symptoms in Advanced Cancer Patients Referred to an Outpatient Supportive Care Clinic. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;41(1):49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Casarett D, Johnson M, Smith D, Richardson D. The optimal delivery of palliative care: a national comparison of the outcomes of consultation teams vs inpatient units. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(7):649–55. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruera E, Hui D. Palliative care units: the best option for the most distressed. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(17):1601. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.415. author reply 01-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hui D, Elsayem A, Palla S, De La Cruz M, Li Z, Yennurajalingam S, et al. Discharge outcomes and survival of patients with advanced cancer admitted to an acute palliative care unit at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(1):49–57. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferris FD, Bruera E, Cherny N, Cummings C, Currow D, Dudgeon D, et al. Palliative cancer care a decade later: accomplishments, the need, next steps. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(18):3052–58. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, Abernethy AP, Balboni TA, Basch EM, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(8):880–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bruera E, Hui D. Integrating supportive and palliative care in the trajectory of cancer: establishing goals and models of care. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(25):4013–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.5618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, Ayanian JZ, Block SD, Weeks JC. Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(2):315–21. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bird CE, Shugarman LR, Lynn J. Age and gender differences in health care utilization and spending for medicare beneficiaries in their last years of life. J Palliat Med. 2002;5(5):705–12. doi: 10.1089/109662102320880525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]