ABSTRACT

An 8-year-old neutered female Cavalier King Charles spaniel was evaluated for progressing right forelimb lameness. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed that the right-side radial nerves and the caudal brachial plexus were swollen. The histological and molecular biological diagnosis by partial biopsy of the C8 spinal nerve was T-cell lymphoma. Coadministration of lomustine and irradiation was started. However, this therapy was ineffective. At necropsy, neoplastic tissues were seen extending into the subarachnoid space of the spinal cord, liver, pancreas and kidneys as gross findings. A large mass was also identified occupying the caudal thorax. Histologic findings included infiltration in these organs and the mass by neoplastic lymphocytes. To date, involvement of peripheral nerves (neurolymphomatosis) is rarely reported in veterinary species.

Keywords: caudal brachial plexus, radius nerve, T-cell lymphoma

Lymphoma is one of the most common neoplasias in dogs [16]. The majority of lymphomas in dogs occur in parenchymatous organs and/or peripheral lymph nodes with occasional primary or secondary involvement of the brain and spinal cord [13, 14]. On the other hand, involvement of peripheral nerves (neurolymphomatosis) is rarely reported in veterinary species. Neurolymphomatosis is a rare condition defined as infiltration of peripheral nerves or nerve roots by neurotropic lymphoma or leukemia [1,2,3]. In humans, there are 4 basic clinical presentations: 1) painful polyneuropathy or polyradiculopathy, 2) cranial neuropathy, 3) painless polyneuropathy and 4) peripheral mononeuropathy [1]. Most human neurolymphomatosis cases are diffuse large B-cell lymphomas when classified by the Revised European- American Lymphoma or World Health Organization (WHO) system [3, 4]. We present a case of a dog with multicentric T-cell lymphoma involving the right radius nerve and the caudal brachial plexus.

An 8-year-old, neutered, female, Cavalier King Charles spaniel was brought to the Rakuno Gakuen University Veterinary Teaching Hospital with a 20-day history of progressive right forelimb lameness. Neurological examination by the referring veterinarian revealed knuckling and decreased superficial cutaneous sensation in the right forelimb. The dog had been treated with oral prednisolone.

On initial referral to our hospital (day 1), the dog’s general physical condition was good. The dog showed right forelimb lameness and, when standing, put a little weight on this leg intermittently. There was marked muscle atrophy of the right triceps muscles. On flexion and extension of the limb, the dog did not show pain related to a specific bone or joint. Physical examination did not reveal any masses or superficial lymphadenopathy upon constitutional palpation. The dog did not show any discomfort upon auxiliary palpation. The deficit of the left forelimb was not detected remarkably in a neurological examination. The cutaneous trunci reflex was present. Cranial nerve reflexes were functionally normal (Table 1). Based on these examinations, neurological deficits of the right brachial plexus, spinal nerves and spinal roots at the C6-T2 level were suspected. As differential diagnoses, neoplasia, intervertebral disc disease and inflammatory disease were suspected. Serum biochemical abnormalities included high alkaline phosphatase activity (ALP, 1,273 unit/l; reference range, 11 to 140 unit/l) and high alanine aminotransferase activity (ALT, 127 unit/l; reference range, 10 to 90 unit/l). The dog’s whole cell blood count (CBC) and 3-view thoracic (left lateral [LL], right lateral [RL] and ventrodorsal [VD]), spinal and right forelimb radiographs showed no significant abnormalities.

Table 1. The results of neurological examination.

| Day 1 | Day 28 | Day 42 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LF | RF | LR | RR | LF | RF | LR | RR | LF | RF | LR | RR | |

| CP | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Flexor reflex | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Biceps reflex | 2 | 0 | – | – | 1 | 0 | – | – | 1 | 0 | – | – |

| Triceps reflex | 2 | 0 | – | – | 1 | 0 | – | – | 1 | 0 | – | – |

| Cutaneous trunci reflex | Normal | Not detected on either side | Not detected on either side | |||||||||

LF: Left forelimb, RF: Right forelimb, LR: Left pelvic limb, RR: Right pelvic limb, CP: conscious proprioceptive response. 0: Absent, 1: Decrease, 2: Normal, 3: Increase

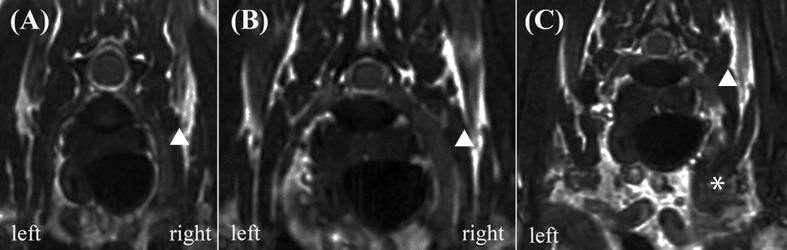

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed on day 14. The images were obtained using a low-field MRI unit incorporating an open 0.2-T unit permanent magnet (Sigma Profile, GE Healthcare, Hino, Tokyo, Japan). Images included T2-weighted (T2W), three-dimensional fast imaging employing steady-state acquisition (3D-FIESTA) and T1-weighted (T1W) images before and after intravenous contrast administration (0.1 mmol/kg gadodiamide, Magnevist, Berlex Laboratories, Wayne, NJ, U.S.A.). The epidural fat was intact, and no evidence of cord compression was observed. The right-side radial nerve (C8 and T1 spinal nerves) was thickened, and the caudal brachial plexus was also swollen compared with the left side (Fig. 1). On post-contrast images, lesions were uniformly and slightly hyperintense. Based on these MRI findings, neoplasia and inflammatory disease were suspected, and histopathological diagnosis was requested.

Fig. 1.

3D-FIESTA transverse magnetic resonance image of the C8 spinal nerve (A), the T1 spinal nerve (B) and the caudal brachial plexus (C). The right-side radial nerve (arrow) was thickened, and the caudal brachial plexus (asterisk) was swollen compared with the left side.

On day 28, the dog showed non-weight-bearing lameness of both forelimbs. It also showed discomfort on auxiliary palpation. The decrease in the left forelimb was also revealed in the neurological examination. The cutaneous trunci reflex was not detected on either side (Table 1). These neurological results revealed that the lesion extended at least into the spinal canal. A partial biopsy of the C8 spinal nerve was thus performed using an approach method [12].

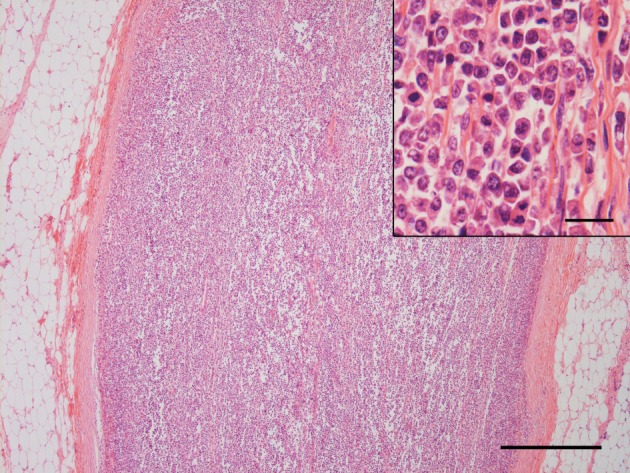

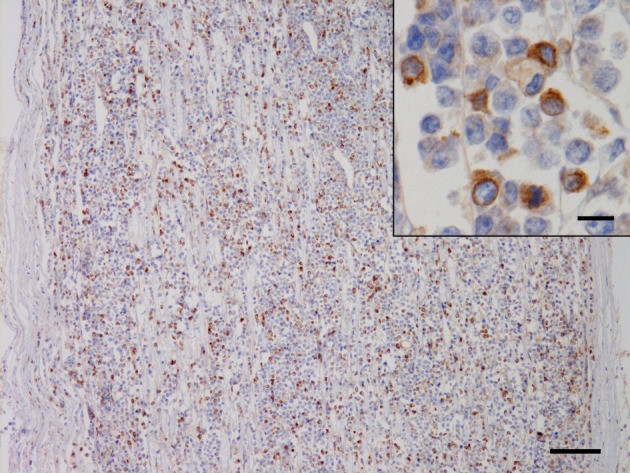

Histologically, neoplastic lymphoid cells proliferated in the endoneurium of the 8th cervical nerve. The cells had a single nucleus 1 to 1.5 times the diameter of a red blood cell and a moderate amount of lightly eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 2) . The nuclei were round to polygonal with occasional indentations and had a diffusely-distributed fine chromatin pattern. One to three nucleoli were sometimes observed. The average number of mitoses in 10 high-power fields using a 40-power objective was 11.1. Detection of clonal antigen receptor gene rearrangement for the immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) and T cell receptor gamma (TCR γ) using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) could also be used to determine lineage of lymphoproliferation. This case had a clonal TCR γ gene rearrangement. Based on the histological findings and clonality assessment, the neoplastic growth in the present case likely corresponded to T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma according to the histological classification of hematopoietic tumors in the WHO International Histological Classification of Tumors of Domestic Animals [17]. Immunohistochemical examination was performed by the avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex method (Vectastain Elite ABC Kit; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, U.S.A.) using polyclonal antibodies against human CD3 (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) and human CD20 (LabVision, Fremont, CA, U.S.A.). A positive reaction for CD3 was detected in the cytoplasm of the scattered neoplastic cells (Fig. 3), and cells positive for CD20 were also distributed in the population, which were considered to be nonneoplastic B lymphocytes based on the results of the clonality assessment.

Fig. 2.

The right 8th cervical nerve is replaced by proliferation of neoplastic lymphoid cells. Hematoxylin and eosin (HE). Bar=500 µm. (Inset) Higher magnification. Neoplastic cells with a round to polygonal nucleus and eosinophilic cytoplasm proliferating in the endoneurial tissue. HE. Bar=20 µm.

Fig. 3.

Positive staining for CD3 in the lymphoid cells infiltrating in the right 8th cervical nerve. Bar=100 µm. (Inset) Higher magnification. The immunoreaction was detected in the cytoplasm of the lymphoid cells. Bar=10 µm. Immunohistochemistry for human CD3 counterstained with hematoxylin.

On day 30, Horner’s syndrome was noted in the right eye. However, the dog’s general physical condition was good. On day 32, a CBC and serum biochemistry showed no significant abnormalities. Administration of oral lomustine (60 mg/m2, every 21 days) was started. On day 39, although the dog’s general physical condition was good, it was not ambulatory. On day 42, postural responses were decreased in not only the forelimbs but also the pelvic limbs. Orthovoltage X-ray radiation therapy (half value layer: 2.5 mmCu, 4 Gy fractions on a Monday-Thursday basis) was started. The radiation area was a square field (15 × 15 cm) from the C5 to T3 vertebrae, centered on the spinal canal and the caudal brachial plexus. The lung area was covered with a 2.5-mm lead sheet. On day 45, Horner’s syndrome was noted in both eyes. A micturition disorder became evident, and assisted emptying of the bladder was performed by manual expulsion. A CBC showed leukocytopenia (1,400 cells/µl; reference range, 5,700 to 16,300 cells/µl) due to the myelosuppression effect of lomustine. Chemotherapy was halted, and only radiotherapy was performed. On day 52, the dog developed difficulty in breathing. Respiratory excursions of the chest were not restricted. The breath sounds were normal. On thoracic radiography, a large mass with ventral shift of the caudal bronchus was seen (Fig. 4A), while there were no abnormalities observed on abdominal radiographs. The radiotherapy was halted. Although euthanasia was discussed, the owner did not request it.

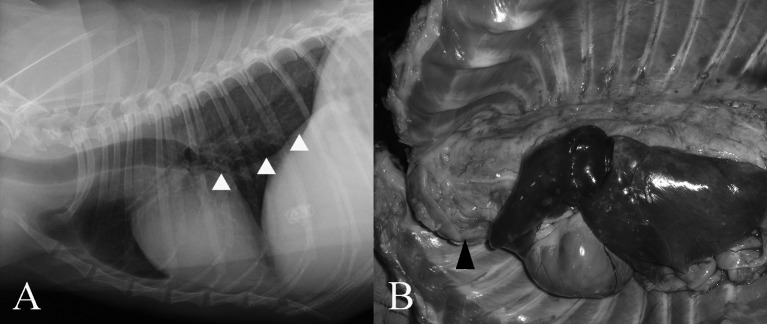

Fig. 4.

(A) Thoracic radiography demonstrates a large mass with ventral shift of the caudal bronchus (arrowhead). (B) A solid mass (arrowhead), about 6 cm in diameter, occupies the precardiac space. The lung lobes show congestive edema.

The dog died on day 53 and was submitted to pathological examinations with the agreement of the owner. Grossly, there was a solid white mass, about 6 cm in diameter, at the anterior mediastinum, which occupied the anterior part of the thoracic cavity and involved the trachea, esophagus and major vessels (Fig. 4B). The mass extended backward along the dorsal mediastinum to the diaphragm. The spinal nerves comprising the right brachial plexus were slightly enlarged and invaded the mass. A white soft tissue was present within the subdural space at the roots of these spinal nerves. The lungs presented diffuse congestive edema, and the pleural effusion was lightly sanguineous and opaque and moderately increased. The pancreas and the both kidneys contained a white nodule about 2 cm in diameter and multiple white nodules of up to 0.4 cm in diameter, respectively. The abdominal fluid was mildly increased.

In the 7th cervical to 1st thoracic spinal cords, the neoplastic cells proliferated in the extradural adipose tissue and the subdural space and partially invaded the spinal parenchyma. Additionally, the neoplastic growth was also detected in the endoneurium of the 6th cervical to 3rd thoracic nerves and dorsal root ganglions of both sides, subarachnoid and Virchow-Robin spaces of the whole brain, pituitary gland and trigeminal nerves. In the thoracic mass, the adipose, muscular and peripheral nervous tissues had been destroyed and replaced by the neoplastic growth. Neoplastic cells invaded the submucosa of the trachea and cranial vena cava which were involved in the mass. Neoplastic cells were also present in the liver, spleen, heart base adipose tissue, diaphragm, bone marrow of the rib and nodules in the pancreas and kidneys.

Canine neurolymphomatosis is uncommon, and only two reports have been published [9, 11]. A comparison of three cases including this case is shown in Table 2 [9, 11]. The immunophenotype of the lymphoma reported by Schaffer et al. was B-cell lymphoma. On the other hand, the present case was T-cell lymphoma. In the case reported by Pfaff et al., infiltration of neoplastic cells was confirmed in lymph nodes and bone marrow. On the other hand, neoplastic cell infiltration in bone marrow was not detected in the case reported by Schaffer et al. In the present case, the neoplastic cell infiltration in bone marrow was confirmed. Although only a limited amount of data was available, it was thought that the clinical stages (i.e. WHO Clinical Staging System) of canine neurolymphomatosis were not uniform.

Table 2. Comparison of three cases with canine neurolymphomatosis.

| Affected peripheral nerves | Extention of neoplastic cells infiltration | Immunophenotype | |

|---|---|---|---|

| The present case | Radial nerve (C8 and T1 spinal nerves) |

Spinal cord (C6-T3) Subarachnoid cavity of CNS Choroid plexus of lateral ventricle Hypophysis Trigeminal nerve Liver Spleen Pancreas Kidney Adipose tissue of a cardiac apex Diaphragm Bone marrow |

T-cell |

| Pfaff et al. (2000) | Trigeminal nerves | Laryngeal Mesenteric vagus Spinal nerves Trigeminal musculature Lymph nodes Bone marrow Meninges CSF |

Not evaluated |

| Schaffer et al. (2012) | Femoral nerve | Multiple lymph

nodes Submandibular Mesenteric Popliteal Kidney |

B-cell |

CNS: Central nervous system, CSF: Cerebrospinal fluid.

There are two case reports regarding the presentation and antemortem diagnosis of lymphoma involving the brachial plexus in two cats [6, 7]. One cat was treated by a forelimb amputation, resection of the mass in the spinal nerve with hemilaminectomy and a multidrug chemotherapy protocol involving cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisolone. However, the owners elected euthanasia because the cat’s subsequent quality of life was unacceptable, while the period from surgical treatment to euthanasia was not described [7]. In humans, the most effective treatment for brachial plexus lymphoma also appears to be poorly defined, because primary solitary peripheral nerve lymphoma is exceedingly rare [5, 10, 15]. On the other hand, Misdraji et al. reported four cases of primary lymphoma of the peripheral nerve in humans. The four patients were treated with aggressive combination chemotherapy, and all patients experienced an initial response. External beam radiation therapy was given in three patients. Two patients relapsed at 4 and 19 months and died of lymphoma at 6 and 43 months, respectively. The other two patients are still alive [8]. Lymphoma is one of the most chemotherapy-responsive tumors diagnosed in dogs [16]. In the present case, postoperative metastases to the liver, pancreas and kidneys were confirmed. Neoplastic tissues were seen extending into the subarachnoid space of the spinal cord, and a large mass was identified within the caudal thoracic cavity. Therefore, the lymphoma in the present case was a systemic disease. Surgical treatment alone has only a limited role in lymphoma, because of the multifocal nature of the disease [16]. The present dog was treated with lomustine (60 mg/m2), but no clinical improvement was seen. In the aforementioned case involving a cat, postoperative chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisolone was performed; the owners elected euthanasia, because the cat’s quality of life following treatment was unacceptable [7]. However, the effects of chemotherapy for brachial plexus lymphoma cannot be discussed, because peripheral nervous system lymphomas have been infrequently reported. Radiotherapy has been demonstrated to be effective for treating localized lymphoma [16]. The present dog was also treated with orthovoltage X-ray radiation therapy as a local treatment. However, the dog died on the 11th postoperative day. Therefore, the effects of radiotherapy for the lymphoma in the brachial plexus cannot be discussed here either.

In the present case, the dog was treated with a variety of management options based on what was available at the time of diagnosis and the owner’s wishes. Further consideration of the management strategy for canine neurolymphomatosis is needed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baehring J. M., Damek D., Martin E. C., Betensky R. A., Hochberg F. H.2003. Neurolymphomatosis. Neuro-oncol. 5: 104–115. doi: 10.1215/15228517-5-2-104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chamberlain M. C., Fink J.2009. Neurolymphomatosis: a rare metastatic complication of diffuse large B-Cell lymphoma. J. Neurooncol. 95: 285–288. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-9918-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grisariu S., Avni B., Batchelor T. T., van den Bent M. J., Bokstein F., Schiff D., Kuittinen O., Chamberlain M. C., Roth P., Nemets A., Shalom E., Ben-Yehuda D., Siegal T.; International primary CNS lymphoma collaborative group. 2010. Neurolymphomatosis: an international primary CNS lymphoma collaborative group report. Blood 115: 5005–5011. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-258210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris N. L., Jaffe E. S., Diebold J., Flandrin G., Muller-Hermelink H. K., Vardiman J., Lister T. A., Bloomfield C. D.2000. The World Health Organization classification of neoplastic diseases of the haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: Report of the Clinical Advisory Committee Meeting, Airlie House, Virginia, November 1997. Histopathology 36: 69–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2000.00895.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liang R., Kay R., Maisey M. N.1985. Brachial plexus infiltration by non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Br. J. Radiol. 58: 1125–1127. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-58-695-1125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linzmann H., Brunnberg L., Gruber A. D., Klopfleisch R.2009. A neurotropic lymphoma in the brachial plexus of a cat. J. Feline Med. Surg. 11: 522–524. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2008.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mellanby R. J., Jeffery N. D., Baines E. A., Woodger N., Herrtage M. E.2003. Magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of lymphoma involving the brachial plexus in a cat. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 44: 522–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2003.tb00500.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Misdraji J., Ino Y., Louis D. N., Rosenberg A. E., Chiocca E. A., Harris N. L.2000. Primary lymphoma of peripheral nerve: report of four cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 24: 1257–1265. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200009000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pfaff A. M., March P. A., Fishman C.2000. Acute bilateral trigeminal neuropathy associated with nervous system lymphosarcoma in a dog. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 36: 57–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Purohit D. P., Dick D. J., Perry R. H., Lyons P. R., Schofield I. S., Foster J. B.1986. Solitary extranodal lymphoma of sciatic nerve. J. Neurol. Sci. 74: 23–34. doi: 10.1016/0022-510X(86)90188-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schaffer P. A., Charles J. B., Tzipory L., Ficociello J. E., Marvel S. J., Barrera J., Spraker T. R., Ehrhart E. J.2012. Neurolymphomatosis in a dog with B-cell lymphoma. Vet. Pathol. 49: 771–774. doi: 10.1177/0300985811419531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharp N. J. H., Wheeler S. J.2005. Neoplasia. pp. 247–279. In: Small Animal Spinal Disorders (Sharp, N. J. H. and Wheeler, S. J. eds.), Elsevier Mosby, London. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snyder J. M., Shofer F. S., Van Winkle T. J., Massicotte C.2006. Canine intracranial primary neoplasia: 173 cases (1986–2003). J. Vet. Intern. Med. 20: 669–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spodnick G. J., Berg J., Moore F. M., Cotter S. M.1992. Spinal lymphoma in cats: 21 cases (1976–1989). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 200: 373–376 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Usuki K., You A., Muto Y., Yamaguchi H., Tsukada T., Honda K.1988. Primary malignant lymphoma of the left brachial plexus. Rinsho Ketsueki 29: 1125–1128 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vail D. M., Young K. M.2007. Hematopoietic tumors. pp. 699–784. In: Small Animal Clinical Oncology. 4th ed. (Withrow, S. J. and Vail, D. M. eds.), WB Saunders, Philadelphia. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valli V. E., Jacobs R. M., Parodi A. L., Vernau W., Moore P. F.2002. pp. 39–47. In: Histological Classification of Tumors of the Hematopoietic Tumors of Domestic Animals. 2nd ser. vol. VIII (Schulman, F. Y. ed.), Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]