In this issue of the Journal of thoracic diseases, Zeng et al. (1) present an extremely interesting synthesis of 145 population-based cancer registries submitting qualified cancer incidence and mortality data to National Cancer Registration Center of China. The authors provide interesting age-standardized incidence and mortality rates, highlighting higher incidence rates in urban areas as well as meaningful geographical disparities.

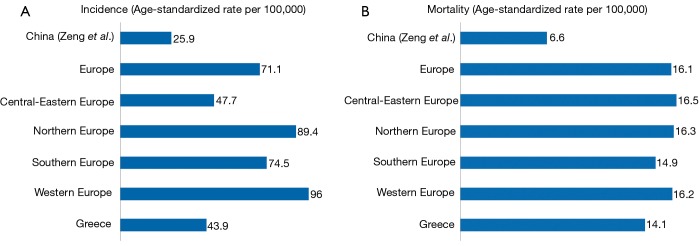

Based on the most recent data, China exhibits considerably lower incidence and mortality rates for female breast cancer than Europe; more specifically, the age-standardized rate (ASR) per 100,000 was equal to 25.9 in China (1), whereas the respective rates according to GLOBOCAN 2012 were 71.1 for Europe with Greece presenting with more favorable rates (43.9) (2) (Figure 1A). Regarding the lower rates in China, the underlying explanation remains elusive as a host of factors including genetic, environmental, lifestyle and somatometric differences have been acknowledged (3,4). As far as the favorable profile of Greece compared to the rest of Europe is concerned, once again the specific explanations remain to be uncovered; nevertheless, genetic differences, adherence to Mediterranean diet, consumption of olive oil, prolonged sun exposure (5-7) may have contributed.

Figure 1.

Incidence and mortality age-standardized rate in Europe, according to GLOBOCAN 2012.

In accordance with incidence rates, China exhibited lower breast cancer mortality rates [6.6 per 100,000 (1)], whereas the respective mortality rate in Europe was equal to 16.1 (2); of note, the discrepancies in mortality rates across Europe were relatively milder (Figure 1B). Especially regarding Greece, the bridging of the gap with the rest of Europe may be attributed to the lack of State implemented national screening program potentially leading to diagnosis at a more advanced stage, to the existence of geographically isolated, remote regions (small islands and mountainous regions) in the country, etc. Indeed, a recent study published by the Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group pointed to worst outcomes from breast cancer among women residing in distant Greek regions (8). Nevertheless, these questions remain to be addressed by future studies as detailed relevant nationwide data are not currently available. Of note, previous studies issued by our research team in tertiary Breast Units have highlighted the suboptimal adherence of women to the worldwide breast cancer screening recommendations (9,10).

On the other hand, treatment modalities among Europe do not seem to exhibit significant differences given the common regulatory agency—European Medicines Agency (EMEA)—for the evaluation of approved agents, the adherence to European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines, etc. (11-13). However, national guidelines in each European country exist, exhibiting slight discrepancies in screening, treatment modalities and surveillance of female breast cancer patients.

In conclusion, it seems that the article by Zeng et al. (1) provides interesting insight into significant questions regarding female breast cancer epidemiology surpassing the boundaries of China. It seems important to develop careful public health plans, conduct screening strategies and adopt cancer prevention measures in order to guide scientific research applicable and treatment applicable to each country and consequently reduce breast cancer burden.

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Zeng H, Zheng R, Zhang S, et al. Female breast cancer statistics of 2010 in China: estimates based on data from 145 population-based cancer registries. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:466-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11 [Internet]. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. Available online: http://globocan.iarc.fr, accessed on May 20, 2013.

- 3.Ziegler RG, Hoover RN, Pike MC, et al. Migration patterns and breast cancer risk in Asian-American women. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993;85:1819-27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adami HO, Hunter D, Trichopoulos D. Textbook of Cancer Epidemiology. NY: Oxford University Press, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and risk of cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1002/ijc.28824. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engel LS, Satagopan J, Sima CS, et al. Sun exposure, vitamin D receptor genetic variants, and risk of breast cancer in the Agricultural Health Study. Environ Health Perspect 2014;122:165-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Psaltopoulou T, Kosti RI, Haidopoulos D, et al. Olive oil intake is inversely related to cancer prevalence: a systematic review and a meta-analysis of 13,800 patients and 23,340 controls in 19 observational studies. Lipids Health Dis 2011;10:127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Panagopoulou P, Gogas H, Dessypris N, et al. Survival from breast cancer in relation to access to tertiary healthcare, body mass index, tumor characteristics and treatment: a Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group (HeCOG) study. Eur J Epidemiol 2012;27:857-66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Domeyer PJ, Sergentanis TN, Katsari V, et al. Screening in the era of economic crisis: misperceptions and misuse from a longitudinal study on Greek women undergoing benign vacuum-assisted breast biopsy. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2013;14:5023-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zografos GC, Sergentanis TN, Zagouri F, et al. Breast self-examination and adherence to mammographic follow-up: an intriguing diptych after benign breast biopsy. Eur J Cancer Prev 2010;19:71-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Senkus E, Kyriakides S, Penault-Llorca F, et al. Primary breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2013;24Suppl 6:vi7-23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cardoso F, Harbeck N, Fallowfield L, et al. Locally recurrent or metastatic breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2012;23Suppl 7:vii11-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azim HA, Jr, Michiels S, Zagouri F, et al. Utility of prognostic genomic tests in breast cancer practice: The IMPAKT 2012 Working Group Consensus Statement. Ann Oncol 2013;24:647-54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]