Abstract

Background:

Job satisfaction is a pleasant emotional state associated with the appreciation of one's work and contributes immensely to performance in an organization. The purpose of this study was to assess the comparative job satisfaction among regular and staff on contract in Government Primary Urban Health Centers in Delhi, India.

Materials and Methods:

The study was conducted in 2013, on a sample of 333 health care providers who were selected using a multistage random sampling technique. The sample included medical officers (MOs), auxiliary nurses and midwives (ANMs), pharmacists and laboratory technicians (LTs)/laboratory assistants (LAs) among regular and staff on contract. Analysis was done using SPSS version 18, and appropriate statistical tests were applied.

Results:

The job satisfaction for all the regular staff that is, MOs, ANMs, pharmacists, LAs, and LTs were relatively higher (3.3 ± 0.44) than the contract staff (2.7 ± 0.45) with ‘t’value 10.54 (P < 0.01). The mean score for regular and contract MOs was 3.2 ± 0.46 and 2.7 ± 0.56, respectively, and the same trends were found between regular and ANMs on the contract which was 3.4 ± 0.30 and 2.7 ± 0.38, regular and pharmacists on the contract was 3.3 ± 0.50 and 2.8 ± 0.41, respectively. The differences between groups were significant with a P < 0.01.

Conclusion:

Overall job satisfaction level was relatively low in both regular and contract staff. The factors contributing to satisfaction level were privileges, interpersonal relations, working-environment, patient relationship, the organization's facilities, career development, and the scarcity of human resources (HRs). Therefore, specific recommendations are suggested to policy makers to take cognizance of the scarcity of HRs and the on-going experimentation with different models under primary health care system.

Keywords: Career development, contract staff, human resource policy

INTRODUCTION

The scarcity of skilled and motivated health care providers is a universal challenge in many countries. In some countries, <50% of the required staff is available, and health care is provided by nonqualified staff.[1,2] India is one of those countries with a critical shortage of health manpower.[1] As per rural health statistics by the Government of India (2011), there is a shortfall of 12.0% doctors at Primary Health Centers (PHCs), 33.9% of female health assistants/lady health visitors, 35.3% of male health assistants; 4.6% of the PHCs were without a doctor, 36.9% PHCs had no laboratory technician, and 24.6% PHCs had no pharmacist.[3] This crisis is being addressed in the new economic policy in India through outsourcing and the appointment of staff on a contract basis.

The contract model is used with the single objective of reducing government expenditure.[4] The position of human resource (HR) in the health care system is unique, in the sense that unlike any other sector, the human touch is essential for patient's care. Therefore, the health care provider's demands for personal development and job satisfaction have to be recognized as quality indicators. Experience has shown that the provider's satisfaction has to be achieved.[5]

The motivation of health care providers is declining day by day. The attrition rate of contract staff is increasing. Therefore, the questions are whether the contract model of HR really takes care of motivation and satisfaction. Do health care providers of two streams, that is, regular and on contract, have similar or different motivations and satisfaction? Who are relatively better placed on the satisfaction scale? Keeping these issues in mind, the present study was conducted to assess the comparative job satisfaction of regular and contract staff in Government Primary Urban Health Centers (PUHCs) in Delhi, India.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling was done using multistage simple random sampling technique in 2013. Three out of the nine districts in Delhi, were chosen by simple random technique. From the 63 PUHCs in the three selected districts, a total sample size of 333 of primary health care providers of medical officers (MOs) (101), auxiliary nurses and midwives (ANMs) (114), pharmacists (85), laboratory assistants (LAs) and laboratory technicians (LTs) (33) both in regular and contract positions were selected randomly ensuring a 10% cadre strength of staff for each category. Inclusion criteria for selection were: >2 years on the job for regular personnel and 6 months on the job for contract personnel. The reason for the 2-year job provision for regular employees was that they would have completed the probation period by that time. For employees on contract, 6 months is the initial period of appointment after which it is likely to be extended subject to satisfactory performance. Data was collected using the job satisfaction scale (49 item five-point Likert scale) developed by Kumar and Khan (2013).[6]

Job satisfaction is the degree to which a health care provider reports satisfaction with different features of his/her job in the PUHCs. Score 1 is given to “I am very much dissatisfied”, score 2 is given to “I am dissatisfied”, score 3 is given to “cannot say”, score 4 is given to “I am satisfied”, and score 5 is given to “I am very much satisfied”.

Analysis of data was done by SPSS version 18, developed by IBM corporation and appropriate statistical tests such as the one-way ANOVA and independent “t”-test were applied. Cronbach's alpha score for internal consistency of scale was 0.909 and content validity was established by three experts. Therefore, the scale used was reliable and valid.

RESULTS

The majority of regular staff was in the age group of 35 years and above. The staff on contract were aged <35 years. The majority of the regular staff in the study population had >15 years of job experience (46.6%) and the majority of the contract staff had a job experience of <5 years (79.5%).

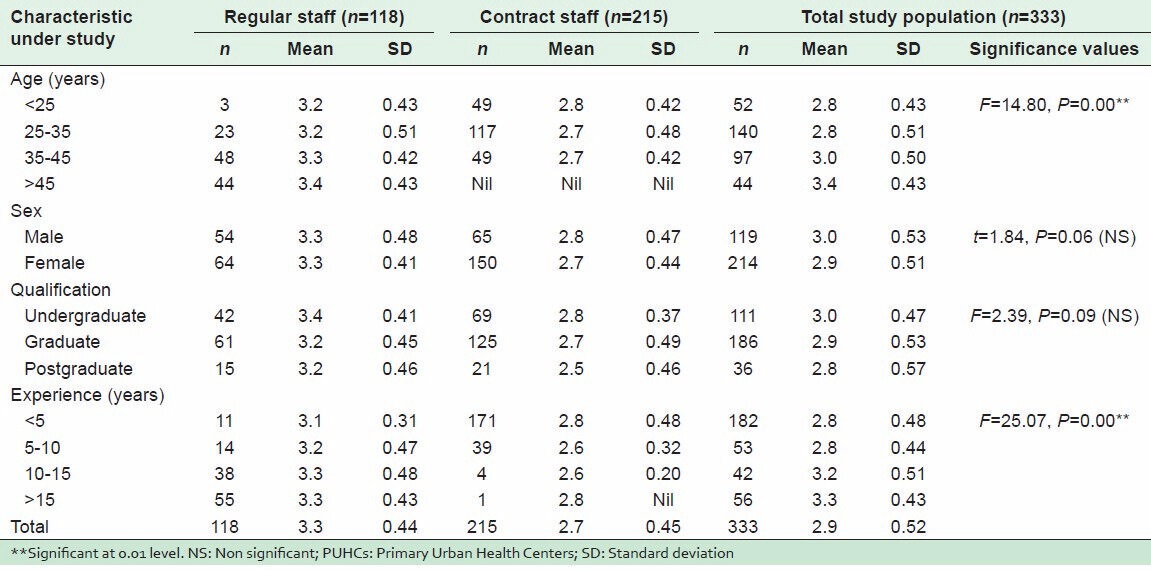

The level of job satisfaction for the entire study population across the different age groups showed statistically significant difference (F value: 14.80; P value: 0.000). There was relatively more satisfaction in the older group. It appears that the employees gradually internalize the realities of the organization, regardless of what they like or dislike, and their adverse reactions to the issues they have gradually decline. Though speculative, the data seemed to fully support this when those on experience and span of work were analyzed. The job satisfaction of the entire study population with different job experiences showed significant differences (F: 25.07; P value: 0.000). However, gender and educational qualification did not reflect any significant difference in job satisfaction as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Background profile and job satisfaction score of regular and contract staff in PUHCs

These findings emerged when satisfaction data was analyzed by pooling both regular and contract staff. The results of a comparison between regular and contract staff suggested that the regular staff were relatively more satisfied than the contract staff. The regular staff showed significantly higher level of satisfaction. The mean score for job satisfaction for the entire regular staff was 3.3 (SD: 0.44) and contract staff 2.7 (SD: 0.45), which had a statistically significant difference (t value was 10.54 and P value was 0.00). The job satisfaction score of regular and contract MOs was 3.2 (SD: 0.46) and 2.7 (SD: 0.56) respectively with t value 4.27 and P < 0.001. Similar findings were obtained among regular and ANMs and LAs/LTs on contract with significant differences (P < 0.001). The regular staff were more satisfied than staff on contract.

All the three districts of Delhi under study showed significant difference in job satisfaction amongst the regular and contract staff as P value was 0.000 and t value 10.54. This denotes that job satisfaction was almost the same across the districts among regular and contract staff. There were no significant differences in districts with regard to conditions related to work.

Further data was analyzed group wise. Different types of staff in the regular category such as the regular MOs and ANMs, ANMs and the pharmacists, and the MOs and pharmacists showed no significant differences as P > 0.05. Similarly study found no significant differences between satisfaction for the different categories of contract staff except the ANMs and LAs/LTs, for whom there was a significant difference as P < 0.05 and t value 2.06. Contractual LAs/LTs were more satisfied than ANMs on contract.

The mean job satisfaction of regular male and female staff was not significant. Similarly, there was no significant difference in job satisfaction between male and female contract staff as P > 0.05.

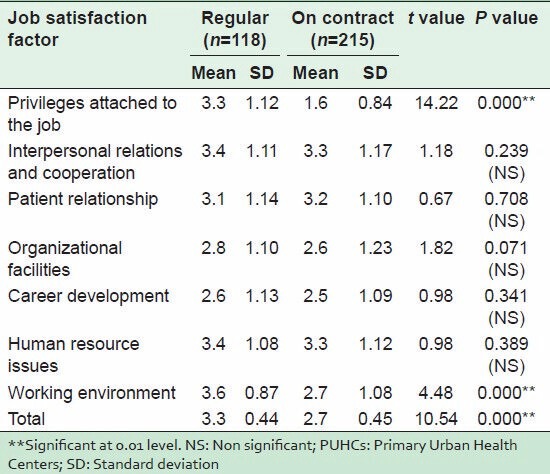

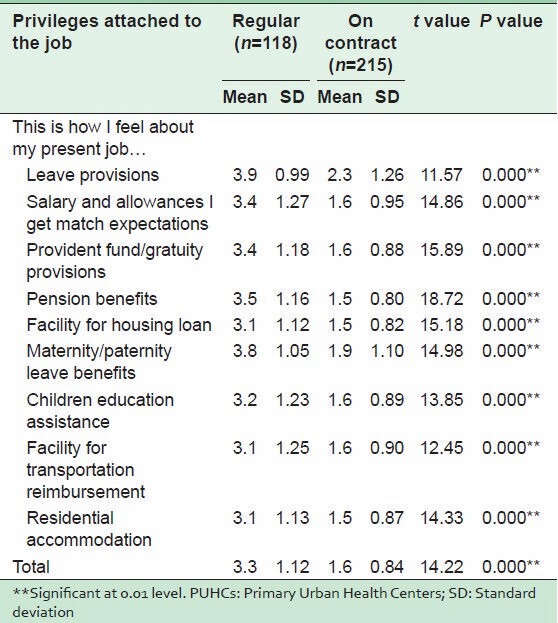

A summary of job satisfaction scores under the seven main factors is shown in Table 2. The detailed results of satisfaction for privileges attached to the job of regular and contract staff are shown in Tables 3–7. Under the construct of privileges attached to the job, there were significant differences for job satisfaction for all variables between regular and contract staff as P < 0.001 as shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Summary of comparative job satisfaction score for regular and contract staff in PUHCs

Table 3.

Comparative job satisfaction score for privileges attached with job for regular and contract staff in PUHCs

Table 7.

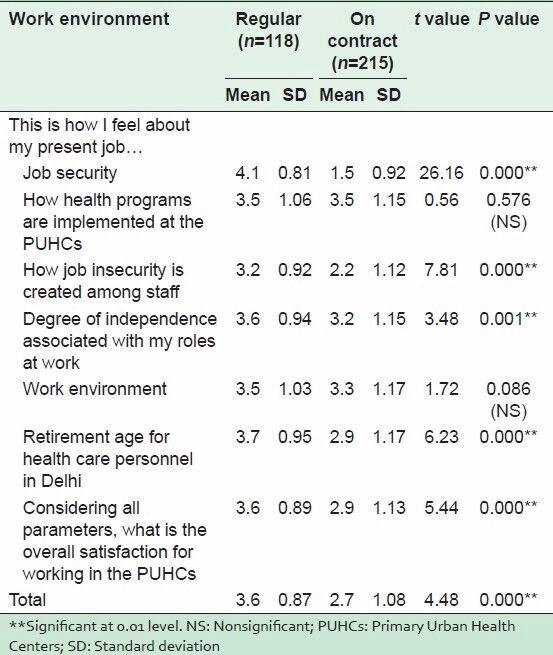

Comparative job satisfaction score for working environment among regular and contract staff in PUHCs

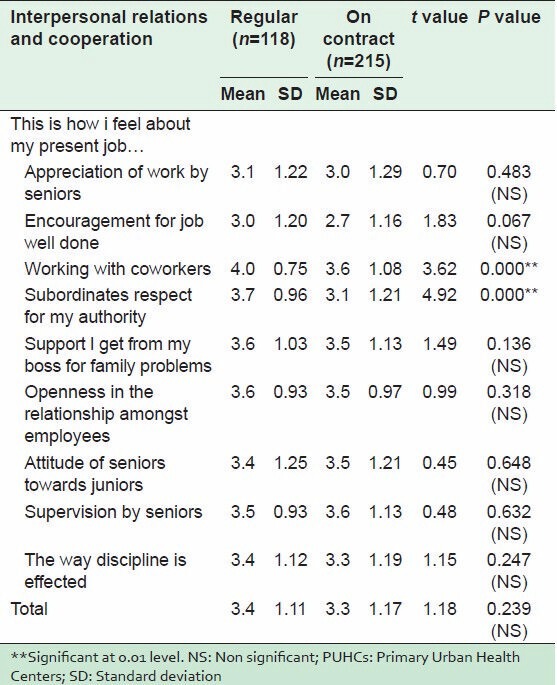

Interpersonal relations and co-operation, variables such as working with colleagues and the respect of subordinates for those in authority showed significant differences. Regular staff were more satisfied than the contract staff, indicating that subordinate staff showed more respect to the authority of the regular staff than to the staff on contract. However, there was no difference in satisfaction between regular and contract staff as regards such factors as support for family-related problems, attitude of senior towards junior staff, openness in relation with employees, supervision by seniors and the way of enforcing discipline in the organization. Both categories of staff had almost the same satisfaction level, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparative job satisfaction score for interpersonal relations and cooperation among regular and staff on contract in PUHCs

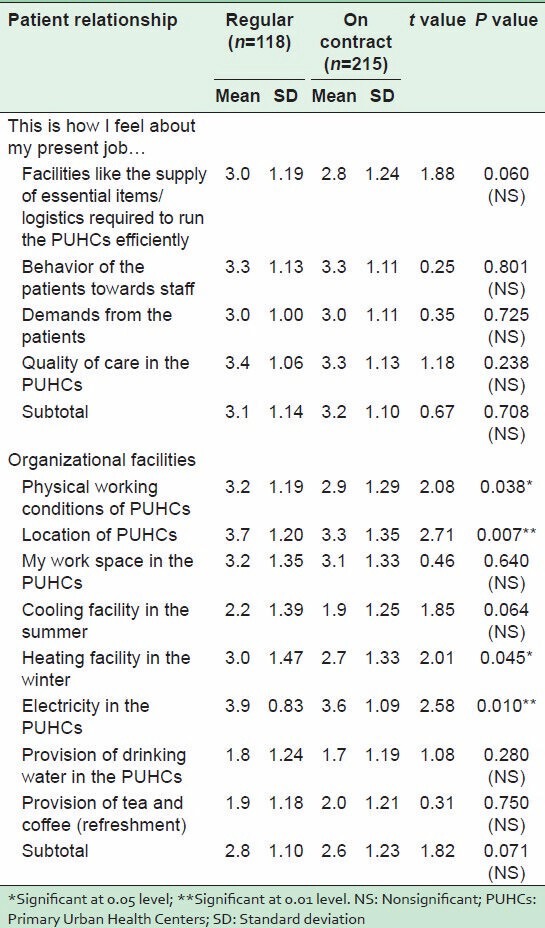

Under the patient relationship construct, there was no difference between job satisfaction of regular and contract staff as P > 0.05. Under the organizational facilities construct, with regard to variables such as the physical working conditions of PUHCs, location of the health facility, heating and electricity, there were significant differences between regular and contract staff (P < 0.05). However, for total satisfaction for regular and contract staff regarding the organizational facilities provided, there was no significant difference as P > 0.05 as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Comparative job satisfaction score for patient relationship and organizational facilities among regular and contract staff in PUHCs

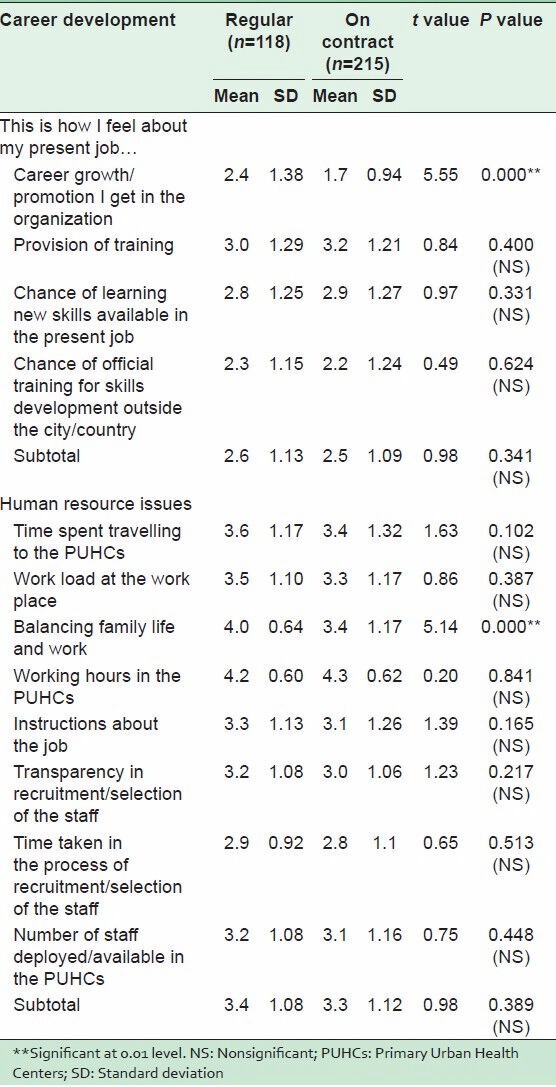

In career development, both types of staff were less satisfied with the organization, but the contract staff were more dissatisfied than the regular staff, and the difference in dissatisfaction was statistically significant as P < 0.001. However, satisfaction for on the job training provided, the chances of both regular and staff on contract of learning new skills and getting training officially outside the country did not reveal any significant difference as P > 0.05 as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Comparative job satisfaction score for career development and human resource issues among regular and contract staff in PUHCs

There were significant differences relating to HR issues such as family and work life with the regular and contract staff. Contract staff were more dissatisfied with work life. The total job satisfaction scores for HR issues did not show any significant differences as P > 0.05 as shown in Table 6.

There was a remarkable difference in the perception of regular and contract staff on the working environment of the health facilities. Contract staff felt that they had little job security in their present job. There was a significant difference for independence associated with the job, and contract staff were dissatisfied with this area of the present job. Taking into account all the variables of job satisfaction, there was a significant difference in job satisfaction between regular and staff on contract as shown in Table 7.

Factor analysis of job satisfaction items was done by SPSS version 18. In Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure (KMO) of sampling adequacy and Bartlett's test, the KMO adequacy was 0.855 which means the sample was adequate for factor analysis. In running the factor analysis, the minimum factor loading was set at 0.4. All factors were considered if they had an Eigen value over 1. This resulted in seven factors in the analysis, and one job satisfaction item not loaded. This was the “way of implementation of health programs in the dispensary”. Under factor analysis, seven factors were identified: Factor 1: Privileges attached to the job, factor 2: Interpersonal relations and cooperation, factor 3: Work environment, factor 4: Patient relationship, factor 5: Organization facilities, factor 6: Career development, factor 7: HR issues.

On job satisfaction as a dependent variable, nature of job and educational level were treated as independent variable to compute the regression analysis. The results show that the nature of position whether regular or contract alone explains 25.1% of variance in the job satisfaction of health care providers (R square = 0.251, P = 0.000). The nature of work along with the level of education of health care providers explain the 26.5% variance in job satisfaction (R square = 0.265, P = 0.015). On the nature of work, whether contract or regular, the beta value was 0.501 at a significance level of 0.01. The findings strongly suggest that the mode of employment of the employee and the nature of the organization itself contribute substantially to the organization's culture and performance.

DISCUSSION

Mean job satisfaction score in those aged 45 years and above was 3.4. It was significantly higher than for those aged <35 years (mean score 2.8). It shows that the older group of staff was significantly more satisfied than the younger group. Older staff tend to have more job satisfaction than younger ones (Bowen et al., 1994).[7] Clark et al. (1996)[8] and Al Juhani et al. (2006), reported that the fulfillment of higher level of need with increasing age and the attainment of senior positions could account for the higher satisfaction levels.[9] The older workers appear to be more satisfied than younger workers could be attributed to better adjustment at work, greater rewards, less conflict between work and personal life (Al-Eisa et al., 2005).[10] Younger staff reaction to facilities is relatively stronger than those who have been in the organization for a longer period. Research done by Bowen et al. (1994),[7] Bretz and Judge (1994),[11] Boltes et al. (1995),[12] and Al-Eisa et al. (2005)[10] found that overall job satisfaction increased with years of experience in the job. Therefore, the findings of the present study are well supported by earlier studies.

The insignificant differences in job satisfaction found between male and female staff are fully supported by Smith and Plant (1982),[13] De Vaus and McAllister (1991),[14] and Al-Eisa et al. (2005).[10]

Different education levels in the study population did not make any significant differences in job satisfaction. This means the level of education had no bearing on job satisfaction in the present study.

The study showed that the majority of contract staff felt that there was some discrimination between regular and contract staff doing the same kind of work. The Common Review Mission identified great disparity between regular employees and those on contract and thus recommended a parity in remuneration to employees on contract and regular ones in a similar service role in public health facilities.[15] WHO (2004) have also identified low salaries as the major reason for low motivation and poor job satisfaction in the health sector.[16]

Herzberg in his two-factor theory emphasized that opportunities for growth and advancement are strong motivators that lead to job satisfaction.[17] Regular staff showed relatively higher level of satisfaction for working with other employees in the PUHCs. Similar findings were observed in a study of CGHS dispensaries in Delhi.[18] The greater degree of independence associated with the work of the regular staff than the staff on contract staff showed a significant difference. Studies by Bhuian et al. (1996)[19] and Landerweerd and Boumans (1994)[20] indicated a positive association between autonomy, job satisfaction, and work motivation.

Overall satisfaction score was relatively low in the present study population. Under National Rural Health Mission, contract appointments have improved the overall availability of HRs at all levels of health facilities, but a general sense of lack of motivation has been observed because of poor service conditions, outdated renewal policies and clear lines of demarcation between regular and contract employees.[21,22] Job satisfaction is a multidimensional phenomenon that cannot be determined by a single factor. A number of factors operate simultaneously, and the dynamics of relationship between factors are more important than a single factor.[18,23]

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The factors which need immediate attention are privileges attached to the job, interpersonal relations, work environment, patient relationship, organization facilities, career development plan, and HR issues. If the contract model is to remain in the primary health care system, there should be better rationalization of structures, and provisions made to eliminate much of the disparity between the two groups of workers in order to achieve good quality services in the system. Job satisfaction of all the employees, both regular and the contract has to be enhanced on the scale of satisfaction. Therefore, it is recommended that suitable policy changes be made for the primary health care system to motivate the personnel to achieve the health goals.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Working Together for Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Last accessed on 2013 Sep 08]. World Health Report. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/2006/whr06_en.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hongoro C, Normand C. Health workers: Building and motivating the workforce. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, editors. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 2nd ed. Washington DC: The World Bank Group; 2006. pp. 1309–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rural Health Statistics. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Govt. of India. 2011. [Last accessed on 2013 Sep 09]. Available from: http://www.nrhm.mis.nic.in/UI/RHS/RHS%202011/RHS%202011%20Webpage.htm .

- 4.Bach S. Prepared for the Global Health Workforce Strategy Group. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. [Last accessed on 2013 Sep 07]. HR and new approaches to public sector management: Improving HRM capacity. Available from: http://www.who.int/health.servicesdelivery/human/workforce/papers/HR.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sutherland VJ, Cooper CL. Job stress, satisfaction, and mental health among general practitioners before and after introduction of new contract. BMJ. 1992;304:1545–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6841.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar P, Khan AM. Development of job satisfaction scale for health care providers. India: NIHFW Unpublished; 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowen CF, Radhakrishna R, Keyser R. Job satisfaction and commitment of 4-H agents. J Ext (Online) 1994;32:1. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clarke AE, Oswald AJ, Warr P. "Is job satisfaction U shaped in age? " J Occup Organ Psychol. 1996;69:57–81. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al Juhani AM, Kishk NA. Job satisfaction among primary health care physicians and nurses in Al-Madinah Al-Munawwara. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2006;81:165–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Eisa IS, Al-Mutar MS, Al-Abduljalil HK. Job satisfaction of primary health care physicians at capital health region, Kuwait. Middle East J Fam Med. 2005;3:2–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bretz RD, Judge TA. Person-organization fit and the theory of work adjustment: Implications for satisfaction, tenure, and career success. J Vocat Behav. 1994;44:32–54. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boltes BV, Lippke LA, Gregory E. Employee satisfaction in extension: A Texas study. [Last accessed on 2014 Mar 29];J Ext [Electron J] 1995 33:5. Available from: http://www.joe.org/joe/1995october/rb1.php . [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith DB, Plant WT. Gender differentiation in the job satisfaction of university professors. J Appl Psychol. 1982;67:249–51. [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Vaus D, Mcallister I. Gender and work orientation; Values and satisfaction in Western Europe. Work Occup. 1991;18:72–93. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Common Review Mission Report 6th. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India. New Delhi: Nirman Bhawan; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. The Migration of Skilled Health Personnel in the Pacific Regions. WHO Western Pacific Region. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herzberg F, Mausner B, Snyderman B. The Motivation to Work. New York, NY: John Wiley; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhandari P, Bagga R, Nandan D. Level of job satisfaction among health care providers in CGHS dispensaries. J Health Manage. 2010;12:403–22. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhuian S, Al-Shammari E, Jefri O. Organizational commitment, job satisfaction and job characteristics: An empirical study of expatriates in Saudi Arabia. Int J Commer Manage. 1996;6:57–80. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landerweerd JA, Boumans NP. The effect of work dimensions and need for autonomy on nurses work satisfaction and health. J Occup Organ Psychol. 1994;67:207–17. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Common Review Mission Report 5th. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India. New Delhi: Nirman Bhawan; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar P, Khan AM. Transition in human resource for health: Challenges ahead. Int J Sci Res. 2012;1:138–9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bodur S. Job satisfaction of health care staff employed at health centres in Turkey. Occup Med (Lond) 2002;52:353–5. doi: 10.1093/occmed/52.6.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]