Abstract

Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Vibrio vulnificus and Vibrio cholerae are human pathogens. Little is known about these Vibrio spp. in the coastal lagoons of France. The purpose of this study was to investigate their incidence in water, shellfish and sediment of three French Mediterranean coastal lagoons using the most probable number-polymerase chain reaction (MPN-PCR). In summer, the total number of V. parahaemolyticus in water, sediment, mussels and clams collected from the three lagoons varied from 1 to >1.1 × 103 MPN/l, 0.09 to 1.1 × 103 MPN/ml, 9 to 210 MPN/g and 1.5 to 2.1 MPN/g, respectively. In winter, all samples except mussels contained V. parahaemolyticus, but at very low concentrations. Pathogenic (tdh- or trh2-positive) V. parahaemolyticus were present in water, sediment and shellfish samples collected from these lagoons. The number of V. vulnificus in water, sediment and shellfish samples ranged from 1 to 1.1 × 103 MPN/l, 0.07 to 110 MPN/ml and 0.04 to 15 MPN/g, respectively, during summer. V. vulnificus was not detected during winter. V. cholerae was rarely detected in water and sediment during summer. In summary, results of this study highlight the finding that the three human pathogenic Vibrio spp. are present in the lagoons and constitute a potential public health hazard.

Keywords: Vibrio, Lagoons, Shellfish, Water, Sediment, Human pathogen

1. Introduction

Vibrio spp. are autochthonous to marine and estuarine environments and are components of those ecosystems (Colwell et al., 1977). However, some Vibrio species are also human pathogens. Vibrio parahaemolyticus is recognized throughout the world as the leading causal agent of human gastroenteritis resulting from consumption of raw seafood. Enteropathogenic strains of V. parahaemolyticus generally produce a thermostable direct hemolysin (TDH) and/or a TDH-related hemolysin (TRH). The genes tdh and trh code for TDH and TRH, respectively (Iida et al., 2006). In the United States, Vibrio vulnificus is responsible for 95 percent of all seafood-related deaths following ingestion of raw or undercooked seafood. Moreover, V. vulnificus has often been associated with serious infections caused by exposure of skin wounds to seawater. Different factors have been implicated in virulence of V. vulnificus, including the vvhA gene that encodes hemolytic cytolysin (Oliver, 2006). Vibrio cholerae, the causative agent of cholera, has been detected in natural fresh and brackish waters worldwide. This species has also been isolated from areas where no clinical cases of cholera have been reported (Colwell et al., 1977). However, most environmental isolates are V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 capable of causing diarrheal outbreaks locally (Rippey, 1994).

Vibrios are responsible for numerous human cases of seafood-borne illness in many Asian countries and the United States (Rippey, 1994; Daniels et al., 2000; Su and Liu, 2007). The occurrence of potentially pathogenic Vibrio spp. in coastal waters and shellfish of European countries has already been documented, i.e., in Italy, Spain and France (Barbieri et al., 1999; Hervio-Heath et al., 2002; Martinez-Urtaza et al., 2008). Some non-cholera Vibrio outbreaks have also been described in these countries. However, vibrios are rarely responsible for severe outbreaks in Europe, but instead, are implicated in the incidence of vibriosis (Geneste et al., 2000). In France, one-hundred cases of V. parahaemolyticus infection were reported in 2001, all of which involved consumption of mussels imported from Ireland (Hervio-Heath et al., 2005). Since then, however, only sporadic cases of V. parahaemolyticus infections have been reported (Quilici et al., 2005).

The coastal lagoons of southern France (Mediterranean) are ecosystems that receive inputs from watersheds and exchanges with the sea and are thus characterized by significant variation in water temperature and salinity. The coastal area and lagoons, especially Thau, the largest lagoon, are sites of significant shellfish production. V. parahaemolyticus, V. vulnificus and V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 were isolated in coastal water and mussel samples collected offshore near the lagoons (Hervio-Heath et al., 2002). Two cases of infection involving Vibrio spp. have been reported in the south of France. The death in 1994 of an immunocompromised patient was caused by an infection by V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 after exposure of skin wounds to seawater (Aubert et al., 2001). In 2008, a fisherman was infected by V. vulnificus after a skin injury came into contact with brackish water from the Vic lagoon in southern France. This victim, weakened by both kidney and lung failure, died as a result of sepsis (Personal communication).

The presence of pathogenic vibrios in these lagoons represents a potential public health threat. To evaluate public health risk, data on the prevalence, distribution and virulence of these bacteria are needed.

In this study, the occurrence and abundance of three human pathogenic Vibrio species (V. parahaemolyticus, V. vulnificus and V. cholerae) were investigated in water, shellfish and sediment samples collected from three coastal Mediterranean lagoons during summer and winter seasons of 2006 and 2007. To our knowledge, this report represents the first detection and quantification of these three Vibrio species simultaneously in water, shellfish and sediment of a lagoon ecosystem.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sampling sites

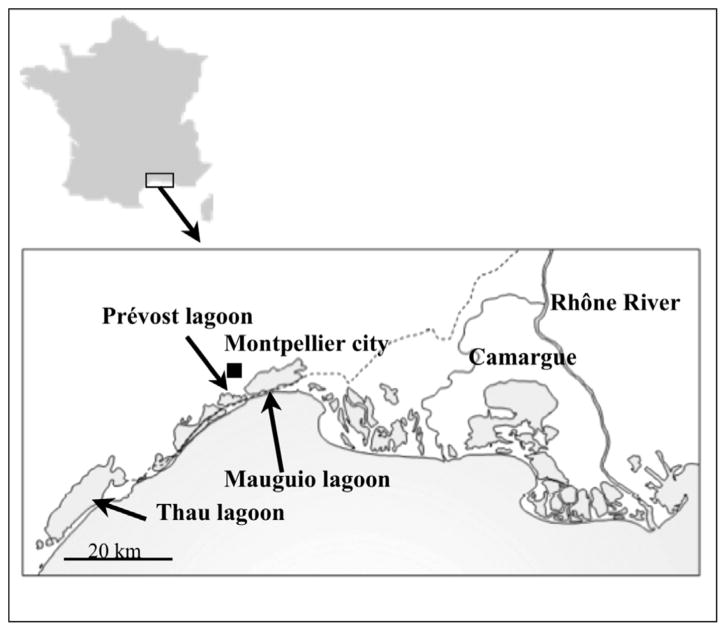

Fig. 1 shows the location of sampling sites included in this study: Thau, Prévost and Mauguio, three lagoons on the French Mediterranean coast (Languedoc area). These lagoons were selected on the basis of fishery and recreational activities that take place there. The Thau lagoon is of economic importance due to its large-scale bivalve mollusk farming (approximately 15,000 t of mussels and oysters produced each year), surface area of 75 km2 and mean depth of 5 m. Small-scale recreational activities (bathing and sailing) also take place in this lagoon. The Prévost lagoon (29 km2, 0.8 m mean depth) sustains a small shellfish (mussel) production capacity. Unlike the Thau and Prévost lagoons, each of which has salinity similar to seawater, the Mauguio lagoon, with a controlled seawater entry, displays significantly lower salinity (31.7 km2, 0.8 m mean depth).

Fig. 1.

Location of the Thau, Prévost and Mauguio lagoons on the French Mediterranean coast (Languedoc area).

2.2. Sample collection and processing

Surface water (5 l) and sediment (five 800 cm3 cores) samples were collected in September 2006 and January and June 2007 at one site in each lagoon (Thau: N 43°23′35.8″, E 003°37′20.8″; Prévost: N 43°31′16.6″, E 003°54′03.1″; and Mauguio: N 43°35′09.5″, E 004°01′15.4″) along with mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis, 20–30 per sample) from the Thau and Prévost lagoons and clams (Ruditapes decussatus, 30–40 per sample) from the Thau lagoon. Water temperature and salinity were recorded simultaneously at the time of sampling at each site. Environmental samples were transported in coolers (12–15 °C) to the laboratory and processed within 4 h of collection.

2.3. Quantification of V. parahaemolyticus, V. vulnificus and V. cholerae by MPN-PCR

A combined most probable number-polymerase chain reaction (MPN-PCR) method (Luan et al., 2008) was applied to detect and enumerate V. parahaemolyticus, V. vulnificus and V. cholerae in the environmental samples. Quantification of the vibrios was achieved by enrichment in alkaline peptone water (APW), following application of the MPN method. Growth of the Vibrio species in APW broth was confirmed by PCR and enteropathogenic V. parahaemolyticus (tdh positive and trh2 positive) by real-time PCR.

Water samples (1, 10, 100 ml and 1 l) were filtered, in triplicate, through 0.45 μm pore size membranes (nitrocellulose, Whatman, GE healthcare, Versailles, France) and the filters were incubated in APW at 41 °C for 24 h. Superficial sediment samples collected from the first 3 cm of five cores were mixed thoroughly, and flesh and intravalvular liquid of mussels and clams (shellfish tissue) were each homogenized. From preparations of sediment and shellfish, 10 ml and 1 ml, respectively, of serial 10-fold dilutions were inoculated in triplicate into APW broth and incubated at 41 °C for 24 h.

After enrichment, bacterial DNA was extracted from 1 ml of APW using the Wizard Genomic DNA purification kit (Promega, Charbonnières, France) designed for Gram-negative bacteria. Three primer pairs, based on toxR and vvhA genes and a portion of the intergenic spacer region (ISR) 16S–23S rRNA were used to detect V. parahaemolyticus, V. vulnificus and V. cholerae, respectively (Table 1). PCR amplification included initial denaturation at 94 °C for 2 min, 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, primer annealing at 57 °C for 30 s, extension at 72 °C for 30 s and final extension at 72 °C for 8 min.

Table 1.

Primers used in this study to detect V. parahaemolyticus, V. vulnificus and V. cholerae in enrichment culture.

| Vibrio species | Target genes region | Primer sequencesa | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| V. parahaemolyticus | toxR |

F-toxRvp: 5′-GTCTTCTGACGCAATCGTTG-3′ R-toxRvp: 5′-ATACGAGTGGTTGCTGTCATG-3′ |

Kim et al. (1999) |

| V. vulnificus | vvhA | L-CTH: 5′-TTCCAACTTCAAACCGAACTATGAC-3′ | Brasher et al. (1998) |

| Vvh-R: 5′-TGATTCCAGTCGATGCGAATACG-3′ | Yamamoto et al. (1990) | ||

| V. cholerae | ISR 16S–23S rRNA |

prVC-F: 5′-TTAAGCSTTTTCRCTGAGAATG-3′ prVCM-R: 5′-AGTCACTTAACCATACAACCCG-3′ |

Chun et al. (1999) |

S: G or C; R: A or G.

This protocol was performed in an Eppendorf Mastercycler (Eppendorf, Le Pecq, France) and optimized in a 25 μl reaction containing 5 μl of 5× buffer (Promega, Charbonnières, France), 0.5 μl of dNTPs (200 μM), 0.25 μl of each primer (25 μM) (Invitrogen, Cergy Pontoise, France), 13.9 μl of ultrapure water (Millipore SAS, Molsheim, France), 5 μl of target DNA (undiluted, diluted 1/10 and 1/100), 0.1 μl of GoTaq DNA polymerase (5 U/μl, Promega, Charbonnières, France) and 1 mg/ml of BSA (Sigma–Aldrich Chimie SARL, Saint Quentin Fallavier, France). The PCR-amplified DNA products were separated on a 1.2% agarose gel in Tris-Borate ETDA (TBE) buffer pH 8.3 (Invitrogen, Cergy Pontoise, France), at 100 V for 30 min with a 1 kb Plus DNA ladder (Invitrogen, Cergy Pontoise, France) and revealed with ethidium bromide (0.5 mg/ml).

MPN values were calculated from the statistical tables of De Man and expressed as MPN per liter, MPN per milliliter and MPN per gram, for water, sediment and shellfish tissue samples, respectively.

2.4. Quantification of tdh+ and trh2+ V. parahaemolyticus by MPN-real-time PCR

V. parahaemolyticus(toxR)-positive enrichment cultures were further characterized by real-time PCR (TAQMAN probe, Eurogentec, Seraing, Belgique) for the presence of virulence-associated genes, tdh and tdh-related hemolysin, trh2, found in enteropathogenic V. parahaemolyticus. Primers and probes for tdh and trh2 genes selected for real-time PCR assay were designed based on the sequences of a 269 bp and 500 bp region of the two genes, respectively, using primers from Bej et al. (1999). Sequence data are available on Gen-bank under accession numbers AF378099 and AY034609 for tdh and trh2, respectively. The real-time PCR systems developed for these two genes exhibited positive amplification on 8 clinical and 30 environmental V. parahaemolyticus strains. TaqMan PCR using tdh and trh2 primers and probes on 50 other bacterial isolates belonging to the Vibrio genus (V. vulnificus, V. cholerae, Vibrio alginolyticus, Vibrio mimicus) and to other genera (Aeromonas, Listonella, Citrobacter, Proteus, Klebsiella, Salmonella, Enterobacter, Escherichia, Pasteurella and Photobacterium) did not exhibit any amplification and thus confirmed the specificity of detection. Sensitivity was tested using real-time PCR on serial dilutions of genomic DNA purified from V. parahaemolyticus tdh+ and V. parahaemolyticus trh2+ and exhibited amplification of tdh and trh2 genes at the level of 0.33 pg and of 0.126 pg, respectively. Alternatively, unenriched 10-fold serial dilution of pure cultures of V. parahaemolyticus tdh and trh2 exhibited a detection level of 1.75 102 CFU/ml and of 4 102 CFU/ml with the above primers and probes for tdh and trh2, respectively. Furthermore, the standards used as controls (PCR-positive control) in these assays were plasmids that were cloned with tdh and trh2 amplicons obtained with the real-time systems. The MPN values were calculated and expressed as above.

3. Results

3.1. V. parahaemolyticus

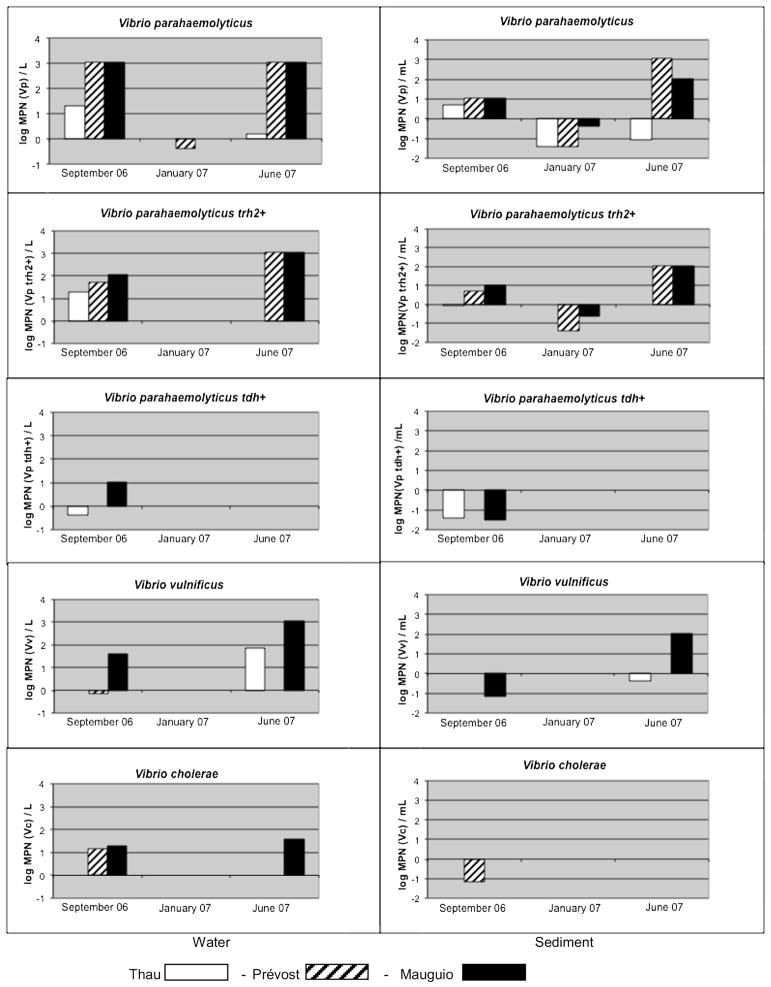

V. parahaemolyticus was detected in water samples collected from the three lagoons included in this study during the summer months (September 2006 and June 2007) (Fig. 2). Concentrations varied from 1 to 20 MPN/l in the Thau lagoon and 1100 MPN/l or more in the Mauguio and Prévost lagoons. Water temperatures ranged from 20 °C to 24 °C in the three lagoons and salinity from 36 to 39.6‰ in the Thau and Prévost lagoons; Mauguio had lower salinity, 29.6‰ in September, 2006 and 20‰ in June, 2007. In January, 2007, culturable V. parahaemolyticus was detected only in the Prévost lagoon, but at a concentration 1000 times lower than during the summer months (0.1–1 MPN/l). Water temperatures at the time of sampling were 8 °C, 11 °C and 3 °C for the Thau, Prévost and Mauguio lagoons, respectively and salinity was comparable to summer salinities, i.e., 37‰, 34‰ and 20‰, respectively. Except for June, 2007, in the Thau lagoon, enteropathogenic trh2+ V. parahaemolyticus was detected in water samples collected from the three lagoons during the summer in numbers from 20 to more than 1100 MPN/l. Enteropathogenic tdh+ V. parahaemolyticus was detected only in water samples collected from the Thau lagoon (0.4 MPN/l) and from the Mauguio lagoon (11 MPN/l) in September, 2006. However, no enteropathogenic V. parahaemolyticus was detected in water samples collected from any of the lagoons during winter sampling (January 2007).

Fig. 2.

Numbers of V. parahaemolyticus, V. parahaemolyticus trh2+, V. parahaemolyticus tdh+, V. vulnificus and V. cholerae in water and sediment samples collected from the Thau, Prévost and Mauguio lagoons. The units are log MPN/l for water samples and log MPN/ml for sediment samples.

The total number of V. parahaemolyticus in all sediment samples collected in winter (January 2007) from the Thau, Mauguio and Prévost lagoons varied from 0.04 to 0.4 MPN/ml; during the summer months, these numbers varied from 0.09 to 5 MPN/ml, 11 to 110 MPN/ml and 11 to 1100 MPN/ml, respectively for the three lagoons. Enteropathogenic trh2+ V. parahaemolyticus was detected in sediment samples collected from the Mauguio and Prévost lagoons at concentrations of 0.04–0.23 MPN/ml in winter and 5 to 210 MPN/ml in summer, but only once in sediment collected from the Thau lagoon (0.9 MPN/ml in September, 2006). Enteropathogenic tdh+ V. parahaemolyticus was detected only in September 2006, in sediment samples collected from the Thau and Mauguio lagoons (0.04 MPN/ml).

V. parahaemolyticus was consistently detected in shellfish tissue during the warm season (Table 2), with concentrations varying from 9 to 210 MPN/g of mussels and from 1.5 to 2.1 MPN/g of clams. While V. parahaemolyticus was absent in mussels during the winter, it nevertheless remained detectable in clams (1.5 MPN/g). The concentration of enteropathogenic trh2+ V. parahaemolyticus in shellfish tissue was lower than the concentration of total V. parahaemolyticus, varying from 0.07 to 9 MPN/g in mussels collected from the Prévost lagoon and detected only once (0.03 MPN/g) in mussels collected from the Thau lagoon (June 2007). Enteropathogenic trh2+ V. parahaemolyticus was not detected in clams and was absent from shellfish collected in January 2007. Enteropathogenic tdh+ V. parahaemolyticus was detected in clams sampled during the summer and winter (from 0.07 to 0.4 MPN/g). However, it was detected only once in mussels collected from the Thau lagoon in September, 2006 (0.04 MPN/g).

Table 2.

Concentration (MPN/g of shellfish tissue) of V. parahaemolyticus (total and enteropathogenic, trh2 and tdh), V. vulnificus and V. cholerae in mussels and clams collected in September 2006 and January and June 2007 from the Thau and Prévost lagoons.

| September 2006 | January 2007 | June 2007 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total V. parahaemolyticus | Thau lagoon clams | 0.8 < 2.1 < 6.3 | 0.6 < 1.5 < 4.1 | 0.5 < 1.5 < 5 |

| Thau lagoon mussels | 20 < 50 < 240 | 0 | 10 < 20 < 140 | |

| Prévost lagoon mussels | 3 < 9 < 39 | 0 | 80 < 210 < 640 | |

| V. parahaemolyticus trh2+ | Thau lagoon clams | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Thau lagoon mussels | 0 | 0 | 0.01 < 0.03 < 0.17 | |

| Prévost lagoon mussels | 3 < 9 < 39 | 0 | 0.02 < 0.07 < 0.28 | |

| V. parahaemolyticus tdh+ | Thau lagoon clams | 0.02 < 0.07 < 0.28 | 0.1 < 0.4 < 0.21 | 0.1 < 0.4 < 0.21 |

| Thau lagoon mussels | 0.01 < 0.04 < 0.21 | 0 | 0 | |

| Prévost lagoon mussels | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| V. vulnificus | Thau lagoon clams | 0.01 < 0.04 < 0.21 | 0 | 6 < 15 < 41 |

| Thau lagoon mussels | 0 | 0 | 0.01 < 0.04 < 0.21 | |

| Prévost lagoon mussels | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| V. cholerae | Thau lagoon clams | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Thau lagoon mussels | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Prévost lagoon mussels | 0 | 0 | 0 |

3.2. V. vulnificus

V. vulnificus was detected during the warm season in water samples collected from the Mauguio lagoon, varying from 40 to more than 1100 MPN/l in water samples collected from the Thau lagoon in June 2007, and from the Prévost lagoon in September 2006 (70 MPN/l and approximately 1 MPN/l, respectively) (Fig. 2).

V. vulnificus was not detected in sediment samples collected from the Prévost lagoon and was detected in the Thau lagoon sediment in June 2007 (0.4 MPN/ml). The concentration of V. vulnificus ranged from 0.07 to more than 110 MPN/ml during the summer months in the Mauguio lagoon sediment samples and was not detected in sediment samples collected from the three lagoons during the winter.

V. vulnificus was not isolated from mussel samples collected from the Prévost lagoon (Table 2), but was detected in clams collected from the Thau lagoon during the warm months (between 0.04 and 15 MPN/g) and in mussels from the same lagoon in June 2007 (0.04 MPN/g).

3.3. V. cholerae

V. cholerae was detected in water samples collected from the Mauguio lagoon only during the warm season (concentrations ranging from 20 to 40 MPN/l) and from the Prévost lagoon in September 2006 (14 MPN/l) (Fig. 2). It was not detected in water samples collected from the Thau lagoon and was detected only in sediment samples from the Prévost lagoon in September 2006 (0.07 MPN/ml). V. cholerae was not detected in shellfish collected from the Thau or Prévost lagoons (Table 2). Isolates from V. cholerae-positive APW broth streaked onto TCBS agar were confirmed as V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 (data not shown).

4. Discussion

In this study, V. parahaemolyticus, V. vulnificus and V. cholerae were detected and enumerated in environmental samples (water, sediment, mussels and clams) using the MPN-PCR method. This method was used because it permits enhanced detection of Vibrio spp. compared to direct plating using selective media, and notably because large samples can be employed (1 l water samples inoculated in triplicate and 10 ml in triplicate of sediment or shellfish). Furthermore, the MPN-PCR and MPN-real-time PCR methods were selected because they enabled providing data comparable to those obtained in studies investigating the presence and ecology of Vibrio spp. and pathogenic Vibrio species in seafood and coastal environmental samples from many other parts of the world (Blanco-Abad et al., 2009; Luan et al., 2008; Vezzulli et al., 2009; Wright et al., 2007).

The presence of the three Vibrio spp. pathogenic for humans was either not detected in water samples collected from the Thau, Prévost and Mauguio lagoons or were detected at very low concentrations during the winter, while higher concentrations were detected during the summer, confirming results of investigators in the United States (Motes et al., 1998; Parveen et al., 2008; Pfeffer et al., 2003) and Japan (Fukushima and Seki, 2004). These Vibrio spp. have also been detected in European coastal waters, i.e. in France (Deter et al., 2010; Hervio-Heath et al., 2002; Robert-Pillot et al., 2004), Spain (Martinez-Urtaza et al., 2008), Italy (Barbieri et al., 1999), Denmark (Hoi et al., 1998) and Norway (Bauer et al., 2006).

Most of the investigations showed the presence or absence of these bacteria in water samples. However, few studies reported total culturable V. parahaemolyticus, V. vulnificus or V. cholerae. The counts of culturable V. vulnificus ranged from 3 × 104 bacteria/l to 2 × 105 bacteria/l in surface waters of Chesapeake Bay (Wright et al., 1996) and from 5 to 19 MPN/l in Danish marine waters (Hoi et al., 1998). Counts of V. parahaemolyticus and V. vulnificus were 9.3 × 104 MPN/l in estuarine water samples collected from the Sada River in Japan (Fukushima and Seki, 2004). Concentrations of V. cholerae in recreational beach waters of southern California were <15–60.9 CFU/l, with higher concentrations in tributaries up to 4.25 × 105 CFU/l (Jiang, 2001). High concentrations of V. parahaemolyticus (up to 105 CFU/l), V. vulnificus (104 CFU/l) and V. cholerae (2 × 104 CFU/l) were reported in estuarine waters of eastern North Carolina during the warmer season and of the northern Gulf of Mexico (Blackwell and Oliver, 2008; Pfeffer et al., 2003; Zimmerman et al., 2007). Depending on the lagoon sampled, the concentrations were a hundred-fold higher than those reported in this study.

Temperature has been shown to be the major factor explaining the dynamics of V. parahaemolyticus, V. vulnificus and V. cholerae in coastal marine ecosystems. Many studies have shown, both experimentally and in situ, that these bacteria enter a viable but non-culturable state when water temperatures average less than 15 °C (Colwell and Grimes, 2000; Roszak and Colwell, 1987). As observed in lagoon water, this phenomenon could explain the absence or presence at very low concentrations of culturable Vibrio in marine coastal waters in the winter. Temperatures above 20 °C favor growth of Vibrio spp. in seawater (Blackwell and Oliver, 2008; Motes et al., 1998; DePaola et al., 2003). Our results show that temperatures ranging from 20 °C to 24 °C during the summer months in the three Mediterranean lagoons studied were correlated with presence of these bacteria.

Salinity is also an important parameter in the dynamics of vibrios in marine systems (Hsieh et al., 2008). Many studies have shown a strong correlation between the presence of these three Vibrio spp. and temperature and salinity (Blackwell and Oliver, 2008; Colwell et al., 1977; DePaola et al., 2003; Jiang, 2001; Motes et al., 1998; Pfeffer et al., 2003; Randa et al., 2004; Wright et al., 1996). The results indicate that a decrease in salinity favors Vibrio growth and proliferation, particularly in brackish waters of estuaries. In this study, the highest concentrations of V. parahaemolyticus, V. vulnificus and V. cholerae occurred in the Prévost and Mauguio lagoons, both of which have lower salinities than the Thau lagoon. A higher abundance of V. vulnificus was observed in the Mauguio lagoon, where salinity ranges from 20 to 29‰, confirming that salinity is a strong determinant of V. vulnificus abundance and dynamics, as previously reported by Randa et al. (2004).

The ecology of V. parahaemolyticus, V. vulnificus and V. cholerae in coastal waters is relatively well documented, but information is scarce for sediments. Vibrios are present in sediment during the summer and are either absent or present in low numbers in the winter (DePaola et al., 1994; Fukushima and Seki, 2004; Pfeffer et al., 2003). V. parahaemolyticus and V. cholerae were detected at concentrations up to 3 × 103 MPN/l and 2 × 102 MPN/l, respectively, in sediment samples collected from the Spezia Gulf, Italy (Vezzulli et al., 2009). The densities of V. parahaemolyticus were one hundred times lower than those reported in this study. V. parahaemolyticus and V. vulnificus counts in estuarine sediment samples collected from the Sada river in Japan displayed values comparable to those observed in sediment samples from the Prévost and Mauguio lagoons (Fukushima and Seki, 2004). V. vulnificus has also been detected in large numbers in estuarine sediment samples (DePaola et al., 1994; Hoi et al., 1998; Wright et al., 1996). Like estuarine sediments, sediment in the lagoons accumulates runoff from the watershed. This watershed discharge supports growth of vibrios. Moreover, V. parahaemolyticus and V. vulnificus concentrations in the lagoon sediments were, on average, 100 to 1000 times higher than in the water column. V. cholerae was detected less frequently, with equivalent concentrations in sediment and water. Thus, it can be concluded that sediment serves as a reservoir for these Vibrio spp. (DePaola et al., 1994; Fukushima and Seki, 2004; Randa et al., 2004; Vezzulli et al., 2009). V. parahaemolyticus is absent from the water column during the winter season, but it is present in sediment, suggesting that sediment allows at least one subpopulation of these bacteria to survive in the culturable state.

The number of Vibrio spp. in shellfish varies widely and depends on geographical area, environmental conditions and local parameters. For example, V. parahaemolyticus was detected in concentrations ranging from <10 to 12,000 CFU/g in Alabama oysters (DePaola et al., 2003), <10 to 600 MPN/g in Chesapeake Bay oysters (Parveen et al., 2008), <10 to 32 MPN/g in mussels collected in Spain (Martinez-Urtaza et al., 2008), <10 to 10,000 CFU/g in oysters from India (Deepanjali et al., 2005) and <10 to 1500 MPN/g in New Zealand oysters (Kirs et al., 2011). In oysters from the lagoons of Mandinga (Veracruz), Mexico, the concentrations of V. parahaemolyticus ranged from <3 to 150 MPN/g (Reyes-Velazquez et al., 2010), comparable to the numbers in mussels from the Thau and Prévost lagoons (9–210 MPN/g).

The number of V. parahaemolyticus in shellfish is an indication of the potential risk of gastroenteritis following consumption of shellfish. However, quantification of pathogenic (tdh− or trh-positive) V. parahaemolyticus may provide a better estimate of public health risk (Zimmerman et al., 2007). Many studies have detected the two virulence genes (tdh or trh) in coastal water, oyster and mussel samples and in environmental isolates of V. parahaemolyticus (Bauer et al., 2006; Deepanjali et al., 2005; DePaola et al., 2003; Deter et al., 2010; Kirs et al., 2011; Martinez-Urtaza et al., 2008; Parveen et al., 2008; Robert-Pillot et al., 2004; Zimmerman et al., 2007). In general, the percentage of samples that were positive for pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus varied according to geographic site, ranging from <20% to 100%. However, the percentage of pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus strains was <0.1%–15% of total V. parahaemolyticus (Deter et al., 2010; DePaola et al., 2003; Hervio-Heath et al., 2002; Ottaviani et al., 2010; Robert-Pillot et al., 2004).

Very few data are available on the number of pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus in shellfish. The average number of tdh+ V. parahaemolyticus in oysters collected from two sites in Alabama was 2.7 CFU/g and 1.3 CFU/g, respectively (DePaola et al., 2003). The number of tdh+ V. parahaemolyticus in oysters in Chesapeake Bay was 10 CFU/g (Parveen et al., 2008). In the northern Gulf of Mexico, the number of tdh+ V. parahaemolyticus and trh+ V. parahaemolyticus ranged from <0.01 to 10 MPN/g oyster tissue (Zimmerman et al., 2007). The number of pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus found in shellfish in this study was slightly lower and reflects the lower concentration of total V. parahaemolyticus in shellfish from Mediterranean lagoons.

This study is the first to simultaneously examine the concentrations of V. vulnificus, V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 and both total and pathogenic (tdh- or trh2-positive) V. parahaemolyticus in water, sediment and shellfish in lagoons.

The three major pathogenic Vibrio spp. for humans were detected in the lagoons, and their presence in raw shellfish for human consumption represents a public health hazard. More information is needed to improve quantitative risk assessment concerning the presence of vibrios in shellfish (WHO, 2011). DePaola et al. (2000) suggested that densities >10 of tdh-and/or trh-positive V. parahaemolyticus be considered unusual. It is important to determine whether physicochemical conditions other than water temperature favor an increase in Vibrio populations. Lagoons with lower salinity or showing a significant decrease in salinity due to heavy rainfall need to be studied to determine the combined effects of salinity and temperature upon Vibrio population dynamics. Organic matter entering the lagoon from the watershed during heavy rainfall may also significantly affect the dynamics of these vibrios. Environmental factors may play an important role in the dynamics of Vibrio spp., and should trigger preventive measures for management of shellfish safety.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding provided by the French Agency for Environmental and Occupational Health Safety (AFSSET) (Programme Environnement Santé; no. ES-2005-020). Support was provided to RRC by NIH Grant No. 2R01A1039129-11A2.

References

- Aubert G, Carricajo A, Vermesch R, Paul G, Fournier JM. Isolement de vibrions dans les eaux côtières françaises et infection à V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139. La Presse Médicale. 2001;30:631–633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri E, Falzano L, Fiorentini C, Pianetti A, Baffone W, Fabbri A, Matarrese P, Casiere A, Katouli M, Kühn I, Mollby R, Bruscolini F, Donelli G. Occurrence, diversity and pathogenicity of halophilic Vibrio spp. and non-O1 Vibrio cholerae from estuarine waters along the Italian Adriatic coast. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:2748–2753. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.6.2748-2753.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer A, Ostensvik O, Florvag M, Ormen O, Rorvik LM. Occurrence of Vibrio parahaemolyticus, V. cholerae and V. vulnificus in Norwegian blue mussels (Mytilus edulis) Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:3058–3061. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.4.3058-3061.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bej AK, Patterson DP, Brasher CW, Vickery MCL, Jones DD, Kaysner CA. Detection of total and hemolysin-producing Vibrio parahaemolyticus in shellfish using multiplex PCR amplification of tl, tdh and trh. J Microbiol Meth. 1999;36:215–225. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(99)00037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell KD, Oliver JD. Ecology of Vibrio vulnificus, Vibrio cholerae and Vibrio parahaemolyticus in North Carolina Estuaries. J Microbiol. 2008;46:146–153. doi: 10.1007/s12275-007-0216-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Abad V, Ansede-Bermejo J, Rodriguez-Castro A, Martinez-Urtaza J. Evaluation of different procedures for the optimized detection of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in mussels and environmental samples. Int J Food Microbiol. 2009;129:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasher CW, DePaola A, Jones DD, Bej AK. Detection of microbial pathogens in shellfish with multiplex PCR. Curr Microbiol. 1998;37:101–107. doi: 10.1007/s002849900346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun J, Huq A, Colwell RR. Analysis of 16S–23S rRNA intergenic spacer regions of Vibrio cholerae and Vibrio mimicus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:2202–2208. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.5.2202-2208.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colwell RR, Kaper J, Joseph SW. Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio parahaemolyticus and other vibrios: occurrence and distribution in Chesapeake Bay. Science. 1977;198:394–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colwell RR, Grimes DJ. Nonculturable Microorganisms in the Environment. ASM Press; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels NA, MacKinnon L, Bishop R, Altekruse S, Ray B, Hammond RM, Thompson S, Wilson S, Bean N, Griffin PM, Slutsker L. Vibrio parahaemolyticus infections in the United States, 1973–1998. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1661–1666. doi: 10.1086/315459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deepanjali A, Kumar HS, Karunasagar I, Karunasagar I. Seasonal variation in abundance of total and pathogenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus bacteria in oysters along the southwest coast of India. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:3575–3580. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.7.3575-3580.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePaola A, Capers GM, Alexander D. Densities of Vibrio vulnificus in the intestines of fish from the U.S. Gulf Coast. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:984–988. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.3.984-988.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePaola A, Kaysner CA, Bowers J, Cook DW. Environmental investigations of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in oysters after outbreaks in Washington, Texas and New York (1997 and 1998) Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:4649–4654. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.11.4649-4654.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePaola A, Nordstrom JL, Bowers JC, Wells JG, Cook DW. Seasonal abundance of total and pathogenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus in Alabama oysters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:1521–1526. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.3.1521-1526.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deter J, Lozach S, Veron A, Chollet J, Derrien A, Hervio-Heath D. Ecology of pathogenic and non-pathogenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus on the French Atlantic coast. Effects of temperature, salinity, turbidity and chlorophyll a. Environ Microbiol. 2010;12:929–937. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima H, Seki R. Ecology of Vibrio vulnificus and Vibrio parahaemolyticus in brackish environments of the Sada River in Shimane Prefecture, Japan. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2004;48:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.femsec.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geneste C, Dab W, Cabanes PA, Vaillant V, Quilici ML, Fournier JM. Les vibrioses noncholériques en France: cas identifiés de 1995 à 1998 par le Centre National de Référence. Bull Epidémiologie Hebdomadaire. 2000;9:38–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hervio-Heath D, Colwell RR, Derrien A, Robert-Pillot A, Fournier JM, Pommepuy M. Occurrence of pathogenic vibrios in coastal areas of France. J Appl Microbiol. 2002;92:1123–1135. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2002.01663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hervio-Heath D, Zidane M, Le Saux JC, Lozach S, Vaillant V, Le Guyader S, Pommepuy M. Toxi-infections alimentaires collectives liées à la consommation de moules contaminées par Vibrio parahaemolyticus: enquête environnementale. Bull Epidemiol AFSSA. 2005;17:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Hoi L, Larsen JL, Dalsgaard I, Dalsgaard A. Occurrence of Vibrio vulnificus biotypes in Danish marine environments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:7–13. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.1.7-13.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh JL, Fries JS, Noble RT. Dynamics and predictive modeling of Vibrio spp. in the Neuse river estuary, North Carolina, USA. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:57–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida T, Park KS, Honda T. Vibrio parahaemolyticus. In: Thompson FL, Austin B, Swings J, editors. Biology of Vibrios. ASM Press; Washington, DC: 2006. pp. 341–348. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang SC. Vibrio cholerae in recreational waters and tributaries of southern California. Hydrobiologia. 2001;460:157–164. [Google Scholar]

- Kim YB, Okuda J, Matsumoto C, Takahashi N, Hashimoto S, Nishibuchi M. Identification of Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains at the species level by PCR targeted to the toxR Gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1173–1177. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.4.1173-1177.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirs M, DePaola A, Fyfe R, Jones JL, Krantz J, Van Laanen A, Cotton D, Castle M. A survey of oysters (Crassostrea gigas) in New Zeeland for Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio vulnificus. Int J Food Microbiol. 2011;147:149–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan X, Chen J, Liu Y, Li Y, Jia J, Liu R, Zhang XH. Rapid quantitative detection of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in seafood by MPN-PCR. Curr Microbiol. 2008;57:218–221. doi: 10.1007/s00284-008-9177-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Urtaza J, Lozano-Leon A, Varela-Pet J, Trinanes J, Pazos Y, Garcia-Martin O. Environmental determinants of the occurrence and distribution of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in the rias of Galicia, Spain. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:265–274. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01307-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motes NL, De Paola A, Cook DW, Veazey JE, Hunsucker JC, Gartright WE, Blodgett RJ, Chirtel SJ. Influence of water temperature and salinity on Vibrio vulnificus in Northern Gulf and Atlantic coast oysters (Crassostrea virginica) Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1459–1465. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.4.1459-1465.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver JD. Vibrio vulnificus. In: Thompson FL, Austin B, Swings J, editors. Biology of Vibrios. ASM Press; Washington, DC: 2006. pp. 349–366. [Google Scholar]

- Ottaviani D, Leoni F, Rocchegiani E, Canonico C, Potenziani S, Santarelli S, Masini L, Mioni R, Carraturo A. Prevalence, serotyping and molecular characterization of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in mussels from Italiangrowing areas, Adriatic Sea. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2010;2:192–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2010.00134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parveen S, Hettiarachchi KA, Bowers JC, Jones JL, Tamplin ML, Mckay R, Beatty W, Brohawn K, DaSilva LV, DePaola A. Seasonal distribution of total and pathogenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus in Chesapeake Bay oysters and waters. Int J Food Microbiol. 2008;128:354–361. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer CS, Hite MF, Oliver JD. Ecology of Vibrio vulnificus in estuarine waters of eastern North Carolina. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:3526–3531. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.6.3526-3531.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quilici ML, Robert-Pillot A, Picart J, Fournier JM. Pandemic Vibrio parahaemolyticus O3:K6 spread, France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1148–1149. doi: 10.3201/eid1107.041008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randa MA, Poltz MF, Lim E. Effects of temperature and salinity on Vibrio vulnificus population dynamics as assessed by quantitative PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:5469–5476. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.9.5469-5476.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Velazquez C, Castaneda-Chavez MD, Landeros-Sanchez C, Galaviz-Villa I, Lango-Reynoso F, Minguez-Rodriguez MM, Nikolskii-Gavrilov I. Pathogenic vibrios in the oyster Crassostrea virginica in the lagoon system of Mandinga, Veracruz, Mexico. Hidrobiologica. 2010;20:238–245. [Google Scholar]

- Rippey SR. Infectious diseases associated with shellfish consumption. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;4:419–425. doi: 10.1128/cmr.7.4.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert-Pillot A, Guenole A, Lesne J, Delesmont R, Fournier JM, Quilici ML. Occurrence of the tdh and trh genes in Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolates from waters and raw shellfish collected in two French coastal areas and from seafood imported into France. Int J Food Microbiol. 2004;91:319–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2003.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roszak DB, Colwell RR. Survival strategies of bacteria in the natural environment. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:365–379. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.3.365-379.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su YC, Liu C. Vibrio parahaemolyticus: a concern of seafood safety. Food Microbiol. 2007;24:549–558. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vezzulli L, Pezzati E, Moreno M, Fabiano M, Pane L, Pruzzo C The VibrioSea Consortium. Benthic ecology of Vibrio spp. and pathogenic Vibrio species in a coastal Mediterranean environment (La Spezia Gulf, Italy) Microb Ecol. 2009;58:808–818. doi: 10.1007/s00248-009-9542-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO - World Health Organization. [accessed 11.05.12];Risk Assessment of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in Seafood: Interpretative Summary and Technical Report. 2011 :200. http://www.fao.org/docrep/014/i2225e/i2225e00.pdf.

- Wright AC, Hill RT, Johnson JA, Roghman MC, Colwell RR, Morris JG. Distribution of Vibrio vulnificus in the Chesapeake Bay. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:717–724. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.717-724.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright AC, Garrido V, Debuex G, Farrell-Evans M, Mudbidri AA, Otwell WS. Evaluation of postharvest-processed oysters by using PCR-based Most-Probable-Number enumeration of Vibrio vulnificus bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:7477–7481. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01118-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K, Wright AC, Kaper JB, Morris JB. The cytolysin gene of Vibrio vulnificus: sequence and relationship to the Vibrio cholerae E1 Tor hemolysin gene. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2706–2709. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.8.2706-2709.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman AM, DePaola A, Bowers JC, Krantz JA, Nordstrom JL, Johnson CN, Grimes DJ. Variability of total and pathogenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus densities in Northern Gulf of Mexico water and oysters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:7589–7596. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01700-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]