Abstract

Paneth cells at the base of small intestinal crypts of Lieberkühn secrete high levels of α-defensins in response to cholinergic and microbial stimuli. Paneth cell α-defensins are broad spectrum microbicides that function in the extracellular environment of the intestinal lumen, and they are responsible for the majority of secreted bactericidal peptide activity. Paneth cell α-defensins confer immunity to oral infection by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, and they are major determinants of the composition of the small intestinal microbiome. In addition to host defense molecules such as α-defensins, lysozyme, and Pla2g2a, Paneth cells also produce and release proinflammatory mediators as components of secretory granules. Disruption of Paneth cell homeostasis, with subsequent induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress, autophagy, or apoptosis, contributes to inflammation in diverse genetic and experimental mouse models.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00018-011-0714-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Antimicrobial peptide, Small intestine, Disulfide bonds, Inflammatory bowel disease, Exocytosis, Epithelium, Dense core secretory granules, Mucosa

Paneth cells and the enteric epithelial barrier

A resident microflora and ingested microorganisms represent a continuing infectious challenge to intestinal epithelium. Factors that contribute to mucosal health include transcytosis of secretory IgA, secreted mucus, gastric and pancreatic secretions, bile salts, peristalsis, the resident commensal microflora, exfoliation of enterocytes during epithelial renewal, and CD8+ intraepithelial T lymphocytes. In addition, innate host defense mechanisms have evolved to confer immediate biochemical protection against infection and colonization by pathogenic or opportunistic microorganisms. The secretion of gene-encoded antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and host defense proteins by Paneth cells plays a major role in mediating this activity [1].

Mechanisms that regulate Paneth cell maturation provide insights into their role in innate immunity and in intestinal homeostasis. Four major epithelial cell lineages populate the adult small intestine. Absorptive enterocytes, goblet cells, enteroendocrine cells, and Paneth cells are renewed continually from mitotically-active, transit-amplifying cell progenitors that reside in crypts of Lieberkühn [2–7]. Villus enterocytes, goblet cells and enteroendocrine cells differentiate as they ascend from crypts onto villi [3, 8, 9]. After emergence from the crypt–villus boundary, absorptive enterocytes live 3–5 days, undergo apoptosis near the tips of the villi, and are exfoliated into the lumen. In contrast, Paneth cell progenitors descend to the crypt base as they accumulate lineage-specific products and adopt their remarkable morphology, and label retention experiments estimate Paneth cell lifetimes at approximately 70 days [10, 11]. Paneth cell differentiation requires continuous Wnt signaling via the Frizzled-5 receptor, inducing specific Paneth cell genes, including α-defensins, which are targets of β-catenin- and TCF-4-mediated transcription [10, 12]. Wnts, the Frizzled-5 receptor, and the Math1, Gfi1, and Sox9 transcription factors are required for Paneth cell differentiation [12], with Sox9 being essential for the appearance of the lineage [13, 14].

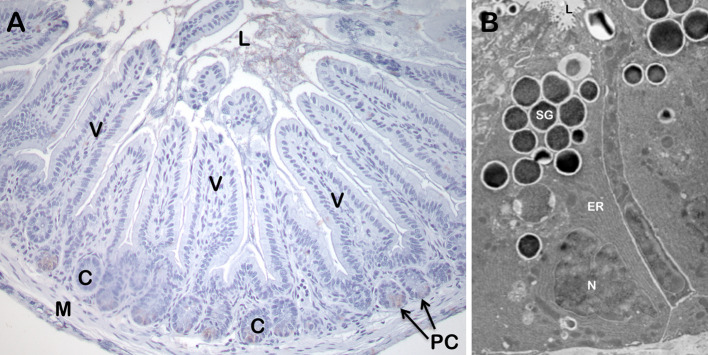

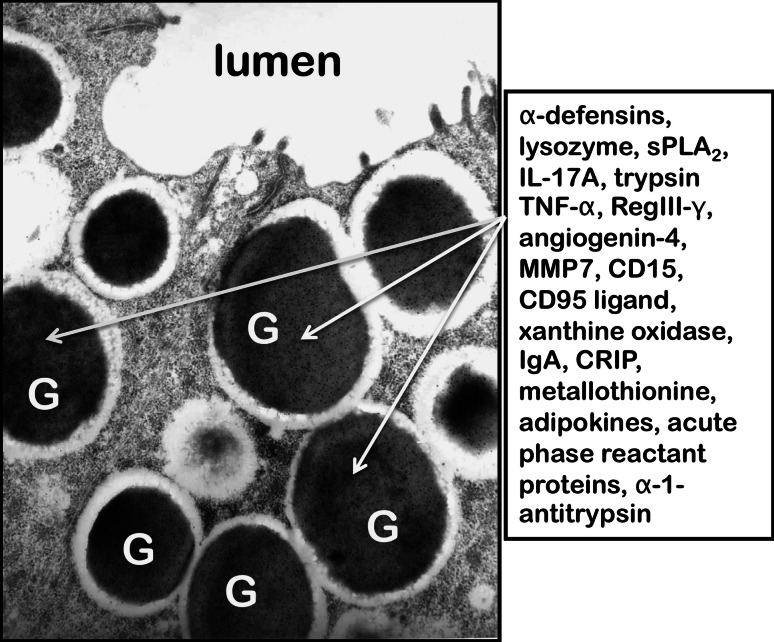

Paneth cells populate the base of the crypts of Lieberkühn in the small intestine of most mammals [1, 15]. These unique cells have an extensively developed endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi apparatus that direct large dense core granules to the apical membrane for secretion (Fig. 1). Paneth cell dense core granules are rich in antibiotic proteins and peptides as well as potent proinflammatory mediators [1, 16, 17]. Diverse Paneth cell gene products include α-defensins, sPLA2, lysozyme, lipopolysaccharide-binding protein, matrix metalloproteinase-7 (MMP7), interleukin-17 (IL-17), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), pancreatitis-associated protein 3 or regenerating islet-derived protein III-gamma (RegIII-γ), CD95 ligand, IgA, cysteine-rich intestinal polypeptide (CRIP), CD15, and metallothionine, which are found at their highest concentrations in fully differentiated Paneth cells that occupy the crypt base [1] (Fig. 2). Described as early as 1867, Paneth cells and their diverse, secreted effectors have become increasingly implicated in mucosal health and disease. For example, reports associate disrupted Paneth cell homeostasis with ileitis [18–21], their release of proinflammatory mediators in TNF-α-induced shock [16], and Paneth cells provide key signaling molecules to maintain adult crypt small intestinal stem cell niche [22].

Fig. 1.

The small intestinal Paneth cell. a A section of ileum from an AKR strain mouse was lightly stained with hematoxylin–eosin. The position of Paneth cells (PC) at the base of crypts (C) is indicated by arrows. Also shown are the small intestinal lumen (L), representative villi (V), and small intestinal smooth muscle (M). b Large, electron-dense secretory granules (SG) of a Paneth cell. The SG are clustered at the apical cell membrane in proximity of the crypt lumen (L). The extensive endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and basolaterally-oriented nucleus (N), characteristic of this lineage are also indicated. Dr. Susan J. Hagen, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, provided the electron micrograph

Fig. 2.

Selected constituents of Paneth cell dense core secretory granules. Arrows denote electron dense secretory granules (G) near the apical surface of a mouse Paneth cell. The dense core granules, surrounded by an electron lucent matrix, are released apically into the lumen, labeled as such, of the crypt by uncharacterized vesicular fusion events. In contrast to the highly fucosylated N- and O-linked glycoprotein components of the electron dense cores, the electron lucent peripheral halo contains GalNAc residues in O-linked oligosaccharides and terminal GlcNAc residues in N- and O-linked glycoconjugates [178]. Box at right contains a partial listing of biologically active proteins confirmed to be constituents of Paneth cell granules

Paneth cell α-defensins

There are two major AMP families in mammals, the cathelicidins and defensins. Cathelicidins have a phylogenetically conserved precursor structure from which remarkably varied AMPs are derived [23–25]. Cathelicidin peptides are highly diverse and occur widely, being found in primates, cattle, swine, and rodents, and also in non-mammalian species, including chicken, trout, and the primitive protovertebrate, the Atlantic hagfish, [23]. Defensins were among the first AMPs to be described [26, 27], and have broad-spectrum antimicrobial activities [28]. The α-defensins are granule constituents of mammalian phagocytes, particularly neutrophils, and of small intestinal Paneth cells [29]. In neutrophil phagolysosomes, the concentration of α-defensins has been estimated at ~10 mg/ml [30], and mouse Paneth cells secrete α-defensins into the lumen of small intestinal crypts at local concentrations of 25–100 mg/ml at the point of release [31, 32]. The β-defensins are expressed by a great variety of epithelial cell types and at many more sites than the α-defensins, including human kidney, skin, pancreas, gingiva, tongue, esophagus, salivary gland, cornea, and airway epithelium and in epithelial cells of several species [33]. The θ-defensins are ~2 kDa, tridisulfide bonded, macrocyclic peptides found only in neutrophils and monocytes of Old World monkeys [34–37]. The biology of defensins as immunomodulatory molecules in the innate and adaptive immune responses have been widely reported and reviewed [38–45] and will not be considered here.

Human Paneth cells produce two α-defensin peptides, HD-5 and HD-6, which are stored in dense core secretory granules as unprocessed α-defensin precursors. Human pro-HD5 is converted to the major HD5 processed product by anionic and meso isoforms of trypsin after release into the crypt lumen [32], although alternative proHD5 processing variants have been identified in secretions elicited from human small intestinal crypts in vitro by carbamyl choline [46]. HD5 peptide levels in ileum range from 90 to 450 μg/cm2 of mucosal surface area [47], suggesting that HD5 may attain concentrations of ~250 μg/ml in the lumen of adult ileum. HD5 has potent microbicidal activity in in vitro assays, but HD6 lacks such activity in comparable assays [48]. Perhaps HD6 has antifungal or antiviral effects or unanticipated immunomodulatory roles following release into the lumen.

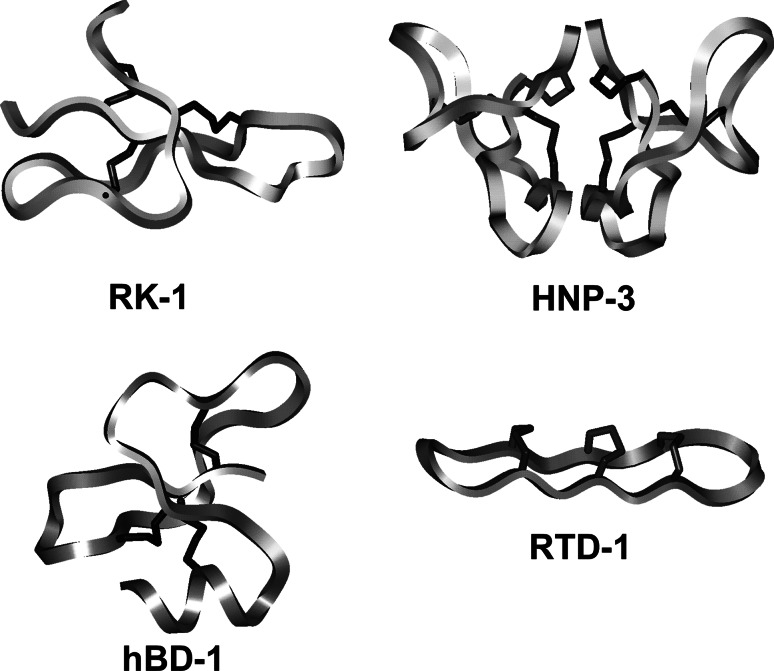

α-Defensin structures

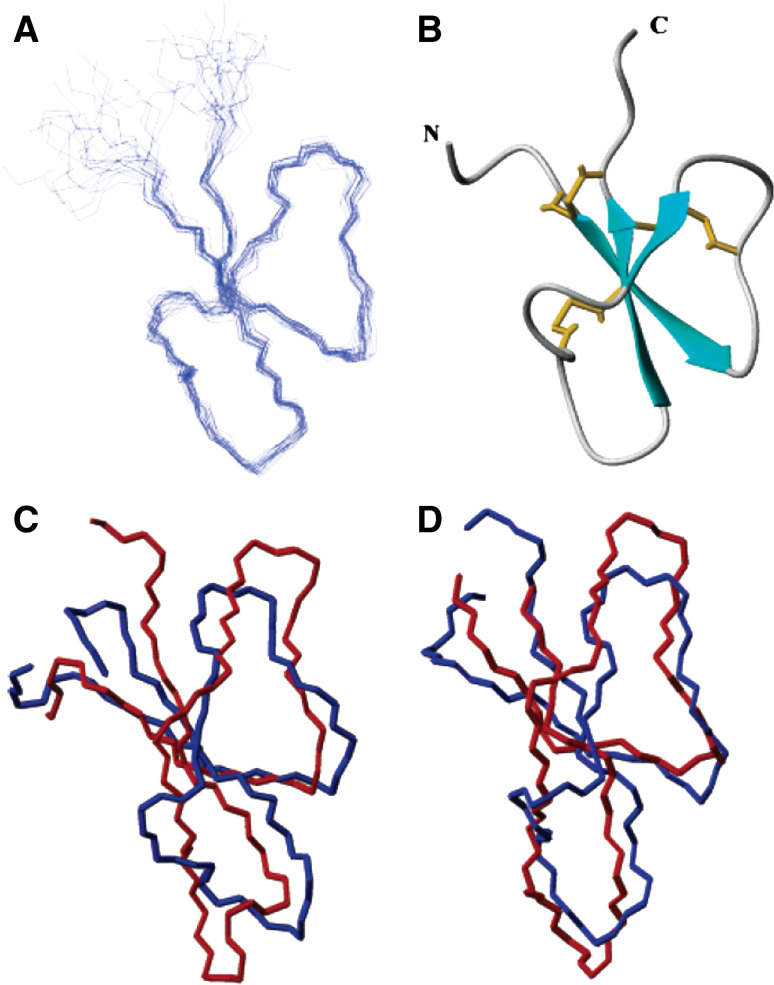

The 3D structures of several α-defensins have been determined by both NMR and X-ray crystallographic techniques [28, 49], and the 3D structures contain a canonical triple-stranded antiparallel β-sheet motif (Fig. 3). The 3- to 4-kDa α-defensins contain six cysteine residues in canonical disulfide bond pairings that distinguish the individual defensin subfamilies [50, 51]. Although the spacing of cysteine residues and Cys–Cys pairings of disulfide bonds in α- and β-defensins differ, the peptides have remarkably similar folded conformations [52–54]. The crystal structure of the human neutrophil α-defensin HNP-3 is a non-covalent, amphipathic dimer [55] as are the crystal structures of all human α-defensin peptides [48, 56, 57]. On the other hand, α-defensins from rabbit neutrophils, mouse Paneth cells, and rabbit kidney are monomeric in solution [53, 54, 58–61]; see Fig. 5.

Fig. 3.

Structures of α-, β- and θ-defensins. The backbone and disulfide structures are shown of RK-1 (upper left), a monomeric rabbit α-defensin, HNP-3 (upper right), a dimeric human α-defensin, hBD-1 (lower left), a monomeric human β-defensin, and RTD-1 (lower right), a θ-defensin from rhesus macaque [179]. Reprinted from [180], with permission

Fig. 5.

The characteristic α-defensin fold. a Diagram of the backbone traces of the 20 lowest energy NMR structures of the mouse Paneth cell α-defensin cryptdin-4 (Crp4). b Ribbon diagram of the Crp4 structure showing the triple β-sheet in turquoise and the three disulfide bonds shown in gold, as generated with MOLMOL. c, d Overlay of the NMR structure of Crp4 (blue) with the NMR structure of rabbit kidney RK-1 (c, red) and the crystal structure of human HNP-3 (d, red). Reprinted from [59], with permission

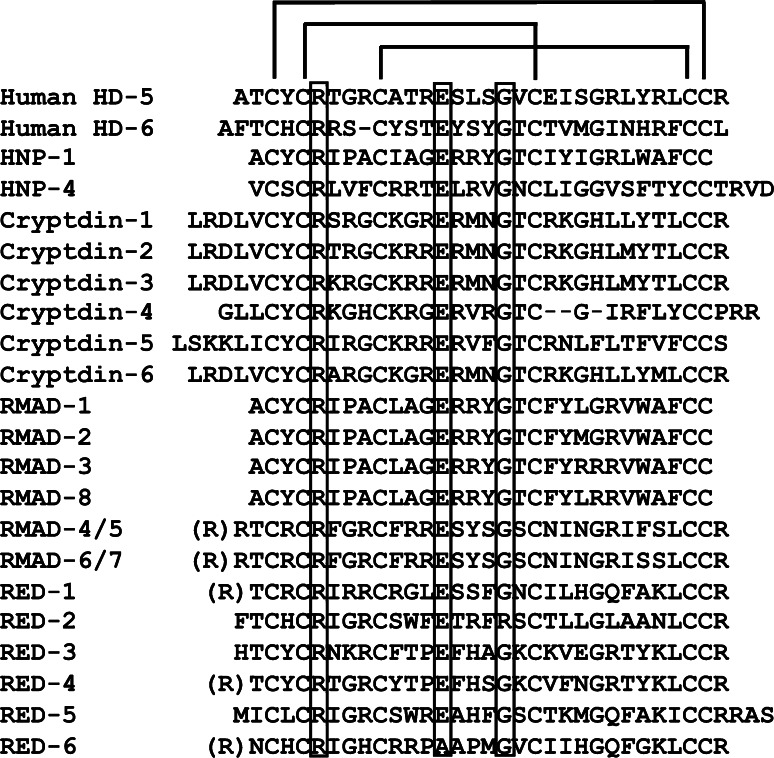

The α-defensins share four canonical structural features (Fig. 4). Numbering residue positions from the N-termini of the mouse Crp4 and rhesus RMAD-4 mature peptides (Fig. 4), the conserved features are: (1) the disulfide array, (2) a salt bridge formed by Arg7–Glu15 hydrogen bonds, (3) a conserved Gly at residue position 19, and (4) a high Arg:Lys molar ratio. Most efforts to identify the function(s) of these canonical α-defensin features have focused on their roles as potential determinants of bactericidal activity. In most instances, mutagenesis at these conserved positions did not alter in vitro bactericidal activity [60, 62–64]. For example, in the case of the disulfide array, the disulfide bonds confer protection against proteolysis by the activating convertases [62, 63, 65–67]. Also, mutagenesis of the Arg7–Glu15 salt bridge did not modify bactericidal peptide activity, although salt-bridge variants do not refold as efficiently as native peptides and are more sensitive to proteolysis [60]. These collective findings suggest that the salt bridge and the Gly19 position may have evolved to provide conserved function(s) in the peptide family that are independent of bactericidal activity, possibly to enable or facilitate efficient chaperone interactions, peptide folding, trafficking in the ER, protection against proteolysis, or receptor-mediated events.

Fig. 4.

Primary structures of representative α-defensins. The single letter notation amino acid sequences of human Paneth cell α-defensins HD-5 and HD-6, human neutrophil α-defensins HNPs 1 and 4, mouse Paneth cell α-defensins cryptdins 1–6, rhesus macaque myeloid α-defensins RMADs 1–8, and rhesus macaque Paneth cell α-defensins REDs 1–6 are aligned. The canonical 1–6, 2–4, 3–5 pairings of the conserved Cys residue positions in all sequences are noted above the HD5 primary structure, and conserved Arg, Glu, and Gly residues are denoted within boxes. Dash characters were introduced into the HD6 and Crp4 sequences to maintain the alignment of conserved residue positions

In contrast to comparisons of HNP-1 and Lys-substituted HNP-1 [65], in vitro bactericidal peptide assays of (R/K)-Crp4 and (R/K)-RMAD-4 in the presence of NaCl showed that both substituted peptides were more sensitive to salt inhibition than the native molecules [68]. Complete Lys for Arg replacements in RMAD-4 did not diminish bactericidal peptide activity or reduce the kinetics of E. coli cell permeabilization, resulting instead in equal or better activities against most bacterial cell targets. Perhaps Arg abundance contributes to optimization of microbicidal activities under higher NaCl concentrations, as a function of the bidentate Arg guanidinium group [69]. The increased sensitivity of Lys substituted Crp4 and RMAD-4 peptides to inhibition by NaCl suggests that the prevalence of Arg as the basic amino acid in α-defensins confers improved bactericidal activity at higher ionic strength. However, in comparisons of native human HNP-1 with a variant containing three Lys for Arg substitutions, HNP-1 was more sensitive to salt inhibition against E. coli than the variant peptide. Although this finding may be due to the low cationicity of HNP-1 relative to Crp4 and RMAD-4, it may be further evidence that effects of α-defensin mutagenesis must be interpreted in the context of individual peptide primary structures.

Mechanisms of α-defensin bactericidal action

The α-defensins are microbicidal against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, certain fungi, spirochetes, protozoa, and enveloped viruses [28, 70], and many peptides kill bacteria by distinctive membrane disruptive mechanisms [49]. For example, certain defensins kill bacteria by sequestering lipid II and inhibiting bacterial cell wall biosynthesis [71–73], whereas human neutrophil α-defensins mediate non-oxidative microbial cell killing by sequential permeabilization of the outer and inner membranes following phagolysosomal fusion [74]. α-Defensins induce the formation of ion channels in lipid bilayers [74], and peptide-elicited effects are influenced by cell and membrane energetics [30]. Peptide-induced efflux of potassium ions from bacterial cells is a sensitive indicator of membrane disruption and cell death [75–77], and extracellular K+ levels increase markedly and almost immediately when bacteria are exposed to varied Paneth cell α-defensins [64, 78].

Even though the overall tertiary structure and topology of α-defensins is highly conserved (Fig. 5), α-defensins with differing primary structures may vary markedly in their membrane disruptive mechanisms. As noted previously, human HNP-3 is a noncovalent dimer, but rabbit neutrophil (NPs), rabbit kidney, and mouse Paneth cell α-defensins are monomers in solution [54, 55, 58, 59], and the mechanisms by which these distinct molecular forms induce leakage from model membranes in vitro differ. For example, dimeric HNP-2 forms stable, 20-Å multimeric pores after insertion in model phospholipid bilayers [79], in contrast to rabbit NP-1 monomers which create short-lived defects [80]. The mouse Paneth cell α-defensin Crp4 exhibits strong interfacial binding to model phospholipid membranes [81], and its induction of graded fluorophore leakage from model membranes, like NPs, depends on peptide concentration and vesicular phospholipid composition [64, 81, 82].

The canonical α-defensin disulfide arrangement provides critical peptide protection during precursor activation, but it is not a determinant of α-defensin bactericidal activity. Disulfide bond disruption does not induce loss-of-function per se, although native Crp4 is completely resistant to proteolysis by matrix metalloproteinase-7, the mouse pro-α-defensin convertase (see below), all disulfide variants of Crp4 and rhesus neutrophil RMAD-4, even those with just one disulfide mutation, were degraded extensively with loss of all bactericidal activity. The in vitro bactericidal activities of certain α-defensin disulfide variants with disordered structures equal or exceed those of the native Crp4 peptide [62–64, 66].

The mechanism of action of the disulfide-null mouse α-defensin cryptdin-4 (Crp4) variant, termed (6C/A)-Crp4, was compared with the native peptide to assess how the two peptides interact with and disrupt phospholipid vesicles of defined composition. Disordered (6C/A)-Crp4 and Crp4 induced similar leakage in live bacteria and model membranes, but the mutant peptide had less overall membrane-permeabilizing activity [83]. Crp4 translocates across highly charged or cardiolipin-containing membranes, in a process coupled with membrane permeabilization, but (6C/A)-Crp4 did not translocate lipid bilayers and consistently displayed membrane surface association. Thus, despite the greater in vitro bactericidal activity of (6C/A)-Crp4, native, β-sheet containing Crp4 induces membrane permeabilization more effectively than disulfide-null Crp4 by translocating and forming transient membrane defects.

α-Defensin distribution and gene expression

α-Defensins were identified initially as antimicrobial activities in cytoplasmic granules of neutrophils [84–86], and subsequent biochemical analyses showed that the molecules were cationic peptides with a tridisulfide array [30]. α-Defensins have been isolated from primate leukocytes and neutrophils of several rodents including rats, rabbits, guinea pigs, and hamsters [28]. Myeloid α-defensin mRNAs are expressed almost exclusively in the bone marrow, where they occur at highest levels in promyelocytes and at lower levels in myeloblasts and myelocytes [87]. Species may differ regarding the leukocyte lineages that express α-defensins as exemplified by the appreciable levels of α-defensins in rabbit alveolar macrophages [26, 27, 88]. Mice are unusual among α-defensin-expressing species in that they lack neutrophil α-defensins [89, 90].

Human monocytes [91] and natural killer (NK) cells [92] express myeloid α-defensins HNP 1–3 constitutively, and microarray experiments have also provided evidence of HNP expression in NK cells [93]. Human CD56+ lymphocytes, accumulate HNPs and the human cathelicidin LL-37 [94], and CD56+ NK cell exposure to Klebsiella spp. outer membrane protein A and to E. coli flagellin induces IFN-γ production and NK cell release of α-defensins [92].

Enteric α-defensins are components of Paneth cell secretory granules [46, 95–98], and other AMPs, e.g., β-defensins or cathelicidins, have not been detected in the small bowel to my knowledge [99]. In human, rat, mouse, and monkey small intestine, α-defensin transcripts and peptides occur only in Paneth cells, with peptides localizing to dense core secretory granules [78, 96–98, 100–102]. In contrast to the numerous and diverse α-defensin genes expressed by mouse and macaque Paneth cells, humans make only two Paneth cell α-defensins, HD5 and HD6 (Fig. 3) [102–106]. Paneth cell α-defensins have also been recovered from luminal rinses of human ileum [32], from washings of mouse jejunum and ileum [95, 97], and from the distal colonic lumen [107].

α-Defensin mRNAs accumulate in small bowel during intestinal development, coinciding with differentiation of the Paneth cell lineage during intestinal crypt ontogeny [108–110]. Paneth cells differentiate as they descend to the base of the crypt from the proliferative compartment [4, 11], and Paneth cells populate the base of small intestinal crypts in most mammals [1]. The HD5 and HD6 genes are expressed in the developing human fetus as early as 13.5 weeks of gestation, as detected by RT-PCR, and their appearance coincides with Paneth cell ontogeny during gestation [110, 111]. The expression of HD5 and HD6 genes in utero shows that human Paneth cell α-defensin gene activation is independent of infectious stimuli, as was found in mice [109, 112].

In mice, certain Crp genes are expressed at a low level in the maturing epithelial cell monolayer of fetal and newborn small intestine in goblet-like cells that are scattered throughout the epithelial sheet [108].

In humans and mice, Paneth cell α-defensin genes may be expressed in reproductive epithelium as shown by the presence of HD5 in female genital tract epithelia [113, 114], and HD5 mRNA in normal vagina, ectocervix, endocervix, endometrium, and fallopian tube specimens. The highest endometrial HD5 levels occurred during the early secretory phase of the menstrual cycle, localized to the upper half of the stratified squamous epithelium of the vagina and ectocervix [113]. In endocervix, endometrium, and fallopian tube, HD5 was found in apically-oriented granules and on the apical surface of some columnar epithelial cells. In addition, Paneth cell α-defensins have been detected in human oropharyngeal mucosa [115]. In the mouse, immunoreactive Crp1 has been localized to Sertoli cells and Leydig cells of the testis [116, 117], and rabbit kidney expresses an α-defensin subset that is distinct from α-defensin peptides isolated from rabbit neutrophils [118, 119]. Despite their expression at these sites, α-defensins occur only in Paneth cells in the small intestine and throughout the gastrointestinal tract [97, 98, 112].

Although expressed only in small intestinal Paneth cells, enteric α-defensins are abundant in the lumen of mouse colon. Paneth cells are absent or very rare in colon, and colonic epithelium does not express α-defensins [97, 106, 120–123], but full-length, intact Paneth cell α-defensins can be recovered in abundance from the colonic lumen, owing to their inherent resistance to proteolysis. Colonic α-defensins have the same overall bactericidal peptide activity as α-defensins from ileal tissue [107], raising the possibility of their influence on colonic mucosal innate immunity. For example, they may influence the composition of the colonic microflora [124], although the microbial burden of the colon is several logs greater than distal small intestine. However, because some defensins also inhibit bacterial peptidoglycan biosynthesis by binding to lipid II, it is possible [71–73, 125], though highly speculative, that even low colonic α-defensin levels could influence the microbiome population by such a mechanism. Achieving an understanding of the interactions between α-defensins and this microbial ecosystem is complicated, because most commensal microbes are unculturable obligate anaerobes and the effects of α-defensins on these species are largely unexplored.

Regulation of α-defensin biosynthesis

The genetic, epigenetic, translational or posttranslational determinants that regulate α-defensin gene activity and peptide abundance remain unknown. In macaques, mice, and the horse, 20 or more diverse enteric α-defensins are predicted based on cDNA cloning studies [103, 126]. In contrast, dogs and cattle lack α-defensin genes altogether, human Paneth cells have a limited α-defensin repertoire consisting only of HD5 and HD6, and rats express only 5 Paneth cell α-defensin genes. Despite the 20 or more α-defensin genes found in the mouse genome(s), though, only 6 or 7 peptides occur at measureable levels [97], and similar findings have been made in rhesus macaque (R.A. Llenado et al., unpublished) and horses [126].

α-Defensin genes map to 8p21-8pter through 8p23 in human, are syntenic in mice [120, 127, 128], and are expressed predominantly in myeloid cells or in Paneth cells [129]. Myeloid and Paneth cell α-defensin genes differ in that genes expressed in cells of myeloid origin consist of three exons, but those expressed in Paneth cells have two [102, 105, 130–133]. In Paneth cell α-defensin genes, the 5′-untranslated region and the preprosegment are coded by exon 1, but an additional intron interrupts the 5′-untranslated region of myeloid α-defensin gene transcripts [134]. Regardless of the site of expression, the 5′-distal exon codes for the α-defensin peptide moiety [70, 102, 130, 132, 133, 135]. Studies of cis-acting DNA elements involved in myeloid α-defensin gene regulation identified a short region containing a CAAT box and a putative polyoma enhancer-binding protein 2/core-binding factor (PEBP2/CBF) site ~90 bp upstream of the transcription start site as important for defensin core promoter activity [136]. Despite these advances, the mechanisms that specify myeloid α-defensin gene expression remain obscure.

Events associated with posttranslational pro-α-defensin activation involve proregion cleavage by lineage-specific proteinases, which may occur during granulogenesis in the regulated pathway or after secretion in primate species [137]. Both myeloid and Paneth cell α-defensins derive from ~10-kDa prepropeptides consisting of canonical signal sequences, usually acidic proregions, and a ~3.5-kDa mature α-defensin peptide in the C-terminal portion of the precursor.

In human and rabbit neutrophils, α-defensins are almost fully processed by primary cleavage steps that leave major intermediates of 75 and 56 amino acids and the mature HNP-1 peptide [137–140]. In vitro studies implicate the granule serine proteinases elastase, cathepsin G, and proteinase-3 as the activating convertases [62, 141].

The details of human and mouse Paneth cell α-defensin processing differ. For example, human Paneth cells store unprocessed α-defensin precursors, e.g., proHD5, which is cleaved after secretion by anionic and meso isoforms of trypsin at R62↓A63 to produce the predominant form of HD5 [32]. Additional, perhaps alternative, proHD5 processing sites exist as evident from an HD5(37–94) variant isolated from human small intestinal crypt secretions elicited with carbamyl choline [46]. Macaque Paneth cell pro-α-defensins may also be processed after secretion by trypsin [103], because macaque Paneth cell α-defensin precursors have canonical trypsin cleavage sites at residue position 62, the junction of the proregion and the α-defensin N-terminus [103].

In contrast, in vivo pro-α-defensin activation in mice takes place intracellularly and prior to secretion [112], and MMP7 gene disruption ablates proCrp processing and impairs innate immunity to oral bacterial infection [142]. Mouse pro-α-defensin processing is mediated by MMP7, the sole pro-α-defensin activating convertase in mouse Paneth cells [112, 142], which co-localizes with α-defensins and pro-α-defensins in dense core secretory granules [143]. MMP7 produces active 3.5-kDa α-defensins by cleaving precursors in vitro at conserved sites in the proregion and at the junction of the propeptide and the α-defensin [144], which relieves the inhibitory effects of the covalently linked proregion [144, 145]. In nearly all pro-α-defensins, the electropositive charge of the α-defensin component, essential for bactericidal peptide activity [68, 146], is balanced or neutralized by anionic amino acid residues in the prosegment. In mouse proCrp4, acidic amino acids clustered near the N terminus of the proregion maintain the precursor in an inhibited state [147]. In the Crp4 precursor, cleavage at Ser43↓Ile44 catalyzed by MMP7 removes 24 amino acid residues from prosegment N-terminus, including 9 acidic amino acids [145], and is sufficient to activate and enable the full bactericidal and membrane disruptive behavior of Crp4 [145, 147].

Mouse α-defensin genomics

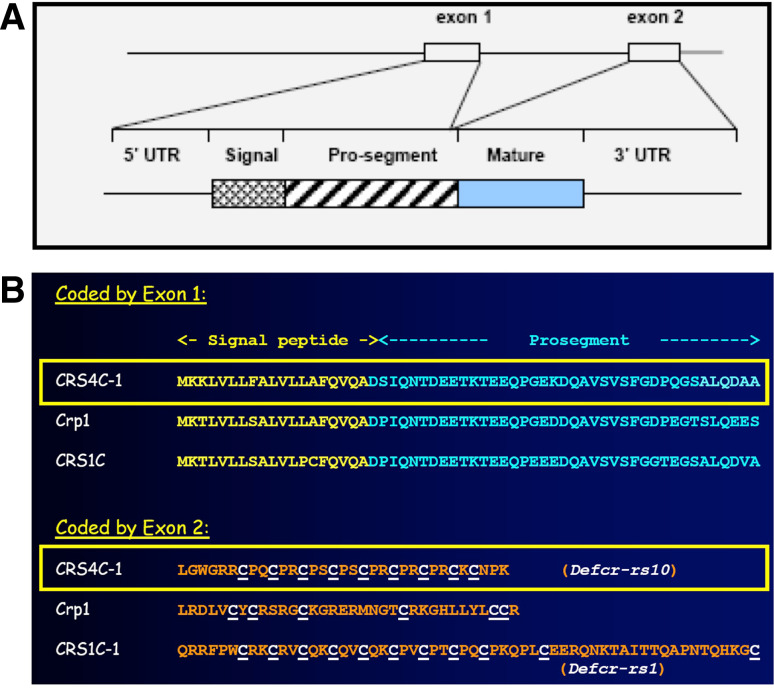

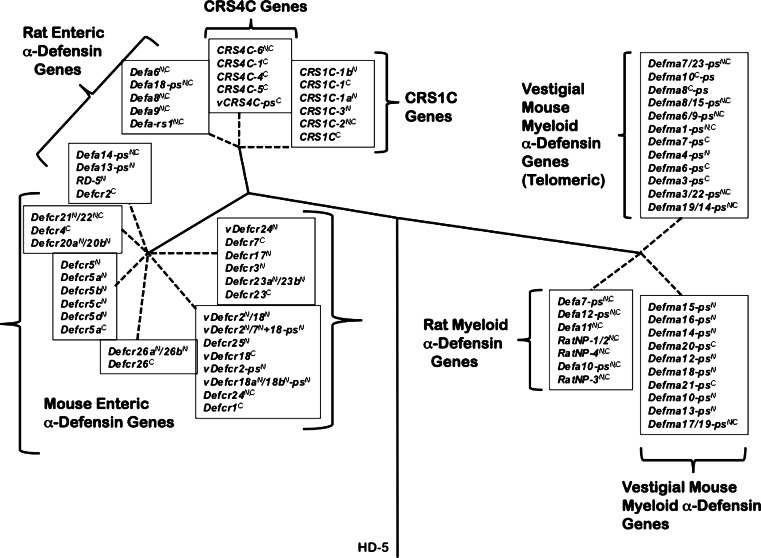

In mice, and only in mice, α-defensin-related genes code for two subfamilies of cysteine-rich sequence (CRS) peptides, CRS1C and CRS4C [78, 148–152]. Also expressed specifically by Paneth cells, CRS and Crp mRNA levels in Paneth cells are approximately the same, and the concentrations of both mRNA subfamilies increase coordinately during postnatal crypt ontogeny [148]. Like the α-defensins [151], CRS peptides are coded by linked genes with conserved two-exon structures [91, 153]. The first exons of CRS genes and Crp genes are highly conserved in that their nucleotide sequences and deduced prepro regions are almost identical (Fig. 6). However, the peptide-coding second exons of CRS genes diverge markedly from the α-defensin-coding Crp genes [148, 149, 151]. CRS1C and CRS4C peptides contain 11 or 9 Cys residues, respectively, in a series of 9 [C]-[X]-[Y] (CRS1C) or 7 [C]-[P]-[Y] (CRS4C) triplet repeats [148, 151]. The mouse CRS1C and CRS4C genes are more closely related to rat enteric α-defensin genes than to any α-defensin gene known in mouse (Fig. 7), which is unexpected but consistent with mouse α-defensin and CRS1C/4C-coding genes being evolutionarily distinct [120].

Fig. 6.

Alignment of CRS1C-1, CRS4C-1, and Crp1 precursors. a Schematic representation of the structure of Paneth cell α-defensin genes and precursors. Reprinted with permission from [28, Fig. 1]. b The primary structures deduced Crp1, CRS4C-1, and CRS1C-1 precursors are aligned, beginning at the initiating methionine residue position, with the signal sequence shown in yellow text and the proregion in aqua text. Natural proCrp1 and CRS4C have been isolated and their MMP7 processed N-termini have been confirmed experimentally [78, 144]. In the lower half of the figure, Cys residues in the mature peptides (orange text) are underlined and highlighted in white text to denote the differences between the Crp1 α-defensin Cys distribution and that of the CRS1C and CRS4C peptide subfamilies

Fig. 7.

Phylogenetic relationships between rat and mouse α-defensin, CRS1C, and CRS4C genes. The introns of mouse Paneth cell α-defensin, CRS1C and CRS4C genes from the NIH C57BL/6 and the mixed strain Celera assemblies, introns of rat enteric α-defensin genes, and second introns of rat myeloid α-defensin genes, and vestigial mouse myeloid α-defensin (DefmaN-ps) genes were used to construct the phylogenetic tree. The tree was rooted with the intron of the human α-defensin-5 (HD-5) gene, and construction of the tree involved the calculation of the proportion difference (p-distance) of aligned nucleotide sites of the entire intron sequences according to the neighbor-joining method. One thousand bootstrap replications were used to test the reliability of each branch. Solid lines maintain phylogenetic distances, but dashed lines do not in order to maintain legibility of sequences of the tree. Reprinted from [90], with permission

Homodimeric and heterodimeric forms of CRS4C isoforms were detected in protein extracts, and both CRS4C forms behaved similarly in in vitro bactericidal peptide assays [152]. CRS4C-coding genes exhibit a regional expression pattern, with highest CRS4C mRNA levels in ileum with nearly undetectable levels in proximal small intestine [78]. CRS4C-1 peptides also occur in Paneth cell dense core granules, and thus are secreted to function in the intestinal lumen.

CRS4C bactericidal peptide activity is membrane-disruptive in that it permeabilizes E. coli and induces rapid microbial cell K+ efflux, but in a manner different from mouse α-defensin cryptdin-4 [78]. In vitro, inactive pro-CRS4C-1 is converted to bactericidal CRS4C-1 peptide by MMP7 proteolysis of the precursor proregion at the same residue positions that MMP7 activates mouse pro-α-defensins. The absence of processed CRS4C in protein extracts of MMP7-null mouse ileum demonstrates the in vivo requirement for intracellular MMP7 in pro-CRS4C processing [78].

Mice of the SAMP1/YitFc strain, derived from the SAMP1/Yit strain [154], develop chronic ileitis that resembles human Crohn’s disease as early as 10 weeks of age, with perianal disease with ulceration and fistulae in ~5% of mice. Prior to histologic evidence of ileitis, SAMP1/YitFc mouse Paneth cell levels of CRS4C mRNAs and peptides increase more than 1,000-fold relative to non-prone strains as early as 4 weeks of age. Possibly, unusually high levels of CRS4C peptide secretion into the SAMP1/YitFc mouse ileum could influence the composition of the microbiome, leading to ileitis in these mice. However, because CRS4C-coding genes are unique to the mouse genome [90, 120, 153], CRS4C overproduction cannot be directly relevant to human disease. Plausibly, CRS4C overexpression could induce inflammation by disrupting Paneth cell homeostasis leading to increased sensitivity to proinflammatory stimuli with resultant ileitis [15, 19–21, 155]. Because (1) CRS4C peptide accumulation is high before histologically detectable ileitis in SAMP1/YitFc mice, (2) SAMP1/YitFc mice still develop attenuated ileitis in the absence of intestinal microflora [156], and (3) membrane-active CRS4C peptides are highly unstable and fold inefficiently in vitro, we speculate that high CRS4C protein expression in SAMP1/YitFc mice may induce Paneth cell ER stress, perhaps increasing sensitivity to additional proinflammatory stimuli and initiating the ileitis.

The primary structures of the most abundant Paneth cell α-defensins in C57BL/6 mice differ from other mouse strains [90]. The genetic basis for C57BL/6 α-defensin proteome differences from other mouse strains was apparent by comparisons of the NIH C57BL/6 and Celera mixed-strain genomic assemblies, which are strikingly different. With regard to gene copy numbers, a repeated multigene cassette apparently unique to C57BL/6, and the orientation of several marker genes, the locus is highly divergent in the two genomic assemblies (Fig. 7). Also, although mice lack neutrophil α-defensins, both assemblies contain approximately 20 α-defensin pseudogenes that are unproductive vestiges of functional rat myeloid α-defensin genes [90].

Paneth cell secretory responses

α-Defensin secretion by Paneth cells constitutes a key source of antimicrobial peptide activity released into the lumen of isolated mouse small intestinal crypts [1, 31], and human Paneth cells also secrete α-defensin-rich granules when exposed to bacteria or their antigens [46, 157].

Paneth cells secrete granules in a dose-dependent manner following interaction with bacterial antigens and in response to pharmacologic stimulation [31, 158–160]. Although the sensors remain unknown, carbamyl choline and bacterial antigenic stimuli both induce increased cytosolic [Ca2+] in Paneth cells by mobilization of intracellular and extracellular Ca2+ stores [158, 161], which is inhibited by selective blockers of a Ca2+-activated intermediate conductance K+ channel KCa3.1, or KCNN4. Compelling evidence now shows that Paneth cell α-defensins both mediate enteric innate immunity and determine the composition of the small intestinal microbiome [47, 162].

α-Defensins and innate mucosal immunity

The contribution of Paneth cell α-defensins to enteric mucosal immunity is evident from the phenotype of mice that are transgenic for the human Paneth cell α-defensin, HD5 [DEFA5-transgenic (+/+)] [47]. DEFA5-transgenic (+/+) mice express a human minigene consisting of 3 kb of genomic DNA encompassing the two peptide-coding exons of the DEFA5 HD5 gene, and expression occurs only in Paneth cells and at levels similar the endogenous mouse genes [47]. The fidelity of HD5 transgene expression in DEFA5-transgenic (+/+) mice suggests that cis-acting β-catenin/TCF-4 sites in the human Paneth cell HD5 gene are conserved and sufficient to direct gene transcription with accuracy. When challenged with Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium by oral inoculation, DEFA5-transgenic (+/+) mice were immune to infection, causing little perceptible disease in DEFA5-transgenic (+/+) mice [47]. Thus, addition of one new α-defensin to Paneth cell secretions of DEFA5-transgenic (+/+) mice was sufficient to confer immunity to orally-administered pathogenic bacteria. As the DEFA5-transgenic (+/+) mouse phenotype illustrates, differential sensitivities of bacterial species to specific α-defensins suggests that peptide diversity may confer selective advantage [47].

α-Defensins secreted by Paneth cells shape the composition of the mouse small intestinal microbiome, apparently by selecting for peptide-tolerant resident microbial species in vivo [162]. For example, in the distal ileum of individual DEFA5-transgenic (+/+) mice, Firmicutes constituted 25.5% of bacterial species compared to 59% in FvB controls, the reference strain for the DEFA5 (+/+) transgenic animals. Also, Bacteroidetes made up 69.3% of bacterial species in DEFA5 (+/+) transgenic ileum, but in FvB controls, only 35% of species were in the Bacteroidetes group [162]. Thus, the ileal microflora of mice secreting a single added exogenous α-defensin was significantly different and genotype-dependent. Also, the distinct repertoire of C57BL/6 mouse Paneth cell α-defensins [90] appear to influence the ileal microbiome, because significant differences were found in the percent distribution of Firmicutes and Tenericutes species in C57BL/6 and FVB mice [162].

Paneth cell defects and host defense

In health, Paneth cells are anatomically restricted to the small intestine. However, during episodes of inflammation throughout the gastrointestinal tract, as in Barrett’s esophagus, gastritis, pancreatitis, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis, Paneth cells may appear ectopically [17, 163, 164]. In mice, crypt intermediate or granulo-mucous cells accumulate Paneth cell gene products in electron dense granules under proinflammatory conditions or in association with crypt dysbiosis. In mice with a transient Paneth cell deficiency [165], intermediate cells and granule-containing goblet cells increase in number and accumulate small, electron dense inclusions that contain both α-defensins and sPLA2 within electron lucent mucin granules [22, 165]. Intermediate cells with α-defensin-rich large dense core granules also appear dramatically in inflammation associated with nematode infection [166], and also when Paneth cell numbers increase in mice treated with anti-CD3 to induce systemic T cell activation [167]. The molecular events that regulate expansion of the Paneth cell compartment under proinflammatory conditions are unknown.

Defects in Paneth cell physiology and α-defensin biology may predispose individuals to infectious challenges. For example, MMP7-null mice are deficient in functional α-defensins due to defective intracellular proCrp processing, and their host defense to oral enteric infection is compromised in vivo [142]. Cystic fibrosis mice, null for the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator, accumulate undissolved Paneth cell secretory granules in mucus-occluded crypts, resulting in bacterial overgrowth of small bowel, mucus colonization, and overgrowth by Enterobacteriaceae [168, 169]. In CD1d-null mice, bacterial exposure of germ-free Cd1d–/– mice induces defective Paneth cell secretory granule ultrastructure which is accompanied by a deficit in degranulation, and bacterial colonization of the intestine is more rapid compared to wild-type mice under specific pathogen-free or germ-free conditions [170].

Expression of Paneth cell secretory proteins is tightly regulated during Wnt-driven lineage determination, but certain Paneth cell gene products are also newly induced in response to microbial colonization or to changes in the microflora. Examples include the increased abundance of bactericidal ribonuclease angiogenin-4 and the C-type lectin RegIIIγ in mice that are monocolonized with Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron relative to germ-free controls [171, 172]. Additionally, small intestinal expression of RegIIIγ, RegIIIβ, CRP-ductin, and RELMβ is induced in mice lacking the toll-like receptor adapter MyD88 by oral bacterial infection with Listeria monocytogenes [173]. In this model, signaling to maintain intestinal homeostasis in response to infection is mediated by Paneth cell MyD88 activation, not by activation of myeloid cells [173, 174]. Also, oral infection of mice with Toxoplasma gondii induces Tlr9 mRNA accumulation, increased type I interferon (IFN) mRNA levels, and elevated Crp3 and Crp5 mRNA expression in C57BL/6 mice [175]. In Tlr9 −/− mice, responses to T. gondii were replicated by administration of IFN-β and were abrogated in IFNAR −/− mice [175]. The T. gondii effects are mediated by Tlr9-dependent production of type I IFNs, but whether the induction of Crps 3 and 5 is a direct or paracrine Paneth cell response to IFN-β is not unknown. Because C57BL/6 mice have several Crp3 and Crp5 gene copies [90], distinguishing between enhanced transcription and posttranscriptional processing of already active genes or recruitment and activation of transcriptionally silent Crp genes during the infectious process is not feasible at this time.

The Paneth cell lineage is committed to the biosynthesis of secretory proteins as components of dense core granules (Figs. 1 and 2). Genetic defects that target secretory pathways or induce autophagy or ER stress have adverse effects on ER-rich Paneth cell homeostasis selectively and contribute to inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis. In mice hypomorphic for the autophagy gene Atg16l1, Paneth cells accumulate apparent failed autophagy vesicles and are defective in secretion [19]. Because this remarkable Paneth cell phenotype is dependent both on the Atg16l1 genetic defect and on infection by a specific strain of mouse norovirus [176], we have a definitive example showing that an individual with a predisposing IBD risk factor may be symptom-free until exposed to a specific infectious agent. Also, severe disruption of the unfolded protein response by selective deletion of Xbp1 in intestinal epithelial cells induces massive Paneth cell apoptosis and fulminant ileitis [20]. Thirdly, germline and inducible gene deletions of the protein disulfide isomerase, Anterior Gradient 2, results in goblet cell Mucin 2 deficiency [177], expansion of the Paneth cell compartment, and severe terminal ileitis and colitis associated with induced ER stress [21]. Thus, mutations that adversely affect Paneth cell homeostasis and alter the composition of their secretions could compromise mucosal immunity by reducing α-defensin production levels, impairing Paneth cell secretion, or by adversely affecting granule solubility and the availability of functional α-defensins and secretory proteins in the crypt microenvironment [21, 177]. Also, Paneth cell dysbiosis may create a local deficiency of Paneth cell-derived signaling molecules that are required to sustain the Lgr5+ crypt stem cell population and the integrity of the enteric barrier [22]. Judging from recent advances in the understanding of Paneth cell biology and complex mechanisms of enteric homeostasis, we can anticipate that these questions will be resolved in the near future.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH Grants DK044632 and AI059346.

Abbreviations

- AMP

Antimicrobial peptide

- CRIP

Cysteine-rich intestinal polypeptide

- Crp

Cryptdin, a term applied only to mouse Paneth cell α-defensins

- (6C/A)-Crp or (6C/A)-RMAD

Peptides in which all Cys residues of the parent peptide are substituted with Ala to eliminate the disulfide array

- CRS1C, CRS4C

Two cysteine-rich sequence, α-defensin-related peptide families of mice

- DEFA5-transgenic (+/+)

Mice transgenic for the human Paneth cell α-defensin HD5

- ER

Endoplasmic reticulum

- HD5 and HD6

Human defensin 5 and 6, the two human Paneth cell α-defensins

- HNP

Human neutrophil defensin

- IL-17

Interleukin-17

- LL-37

The human cathelicidin peptide

- MMP7

Matrix metalloproteinase-7

- NK

Natural killer cells

- NMR

Nuclear magnetic resonance

- NP-

Rabbit neutrophil α-defensin

- proHD5

The HD5 precursor

- RegIII-γ

Pancreatitis-associated protein 3 or regenerating islet-derived protein III-gamma

- (R/K)-Crp or (R/K)-RMAD

Peptides in which all Arg residue positions of the parent molecule are substituted with Lys

- RMAD

Rhesus myeloid α-defensin

- RT-PCR

Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor-α

References

- 1.Porter EM, Bevins CL, Ghosh D, Ganz T. The multifaceted Paneth cell. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59:156–170. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8412-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng H, Merzel J, Leblond CP. Renewal of Paneth cells in the small intestine of the mouse. Am J Anat. 1969;126:507–525. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001260409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng H. Origin, differentiation and renewal of the four main epithelial cell types in the mouse small intestine. IV. Paneth cells. Am J Anat. 1974;141:521–535. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001410406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng H, Leblond CP. Origin, differentiation and renewal of the four main epithelial cell types in the mouse small intestine. V. Unitarian Theory of the origin of the four epithelial cell types. Am J Anat. 1974;141:537–561. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001410407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng H, Leblond CP. Origin, differentiation and renewal of the four main epithelial cell types in the mouse small intestine. I. Columnar cell. Am J Anat. 1974;141:461–479. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001410403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng H, Leblond CP. Origin, differentiation and renewal of the four main epithelial cell types in the mouse small intestine. III. Entero-endocrine cells. Am J Anat. 1974;141:503–519. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001410405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clevers H. Searching for adult stem cells in the intestine. EMBO Mol Med. 2009;1:255–259. doi: 10.1002/emmm.200900034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fre S, Huyghe M, Mourikis P, Robine S, Louvard D, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. Notch signals control the fate of immature progenitor cells in the intestine. Nature. 2005;435:964–968. doi: 10.1038/nature03589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okamoto R, Tsuchiya K, Nemoto Y, Akiyama J, Nakamura T, Kanai T, Watanabe M. Requirement of Notch activation during regeneration of the intestinal epithelia. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G23–G35. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90225.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Es JH, Jay P, Gregorieff A, van Gijn ME, Jonkheer S, Hatzis P, Thiele A, van den Born M, Begthel H, Brabletz T, Taketo MM, Clevers H. Wnt signalling induces maturation of Paneth cells in intestinal crypts. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:381–386. doi: 10.1038/ncb1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bjerknes M, Cheng H. The stem-cell zone of the small intestinal epithelium. IV. Effects of resecting 30% of the small intestine. Am J Anat. 1981;160:93–103. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001600108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Flier LG, Clevers H. Stem cells, self-renewal, and differentiation in the intestinal epithelium. Annu Rev Physiol. 2009;71:241–260. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bastide P, Darido C, Pannequin J, Kist R, Robine S, Marty-Double C, Bibeau F, Scherer G, Joubert D, Hollande F, Blache P, Jay P. Sox9 regulates cell proliferation and is required for Paneth cell differentiation in the intestinal epithelium. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:635–648. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mori-Akiyama Y, van den Born M, van Es JH, Hamilton SR, Adams HP, Zhang J, Clevers H, de Crombrugghe B. SOX9 is required for the differentiation of Paneth cells in the intestinal epithelium. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:539–546. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stappenbeck TS. Paneth cell development, differentiation, and function: new molecular cues. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:30–33. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takahashi N, Vanlaere I, de Rycke R, Cauwels A, Joosten LA, Lubberts E, van den Berg WB, Libert C. IL-17 produced by Paneth cells drives TNF-induced shock. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1755–1761. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ouellette AJ. Paneth cells and innate mucosal immunity. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26:547–553. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32833dccde. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGuckin MA, Eri RD, Das I, Lourie R, Florin TH. ER stress and the unfolded protein response in intestinal inflammation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;298:G820–G832. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00063.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cadwell K, Liu JY, Brown SL, Miyoshi H, Loh J, Lennerz JK, Kishi C, Kc W, Carrero JA, Hunt S, Stone CD, Brunt EM, Xavier RJ, Sleckman BP, Li E, Mizushima N, Stappenbeck TS, HWt Virgin. A key role for autophagy and the autophagy gene Atg16l1 in mouse and human intestinal Paneth cells. Nature. 2008;456:259–263. doi: 10.1038/nature07416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaser A, Lee AH, Franke A, Glickman JN, Zeissig S, Tilg H, Nieuwenhuis EE, Higgins DE, Schreiber S, Glimcher LH, Blumberg RS. XBP1 links ER stress to intestinal inflammation and confers genetic risk for human inflammatory bowel disease. Cell. 2008;134:743–756. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao F, Edwards R, Dizon D, Afrasiabi K, Mastroianni JR, Geyfman M, Ouellette AJ, Andersen B, Lipkin SM. Disruption of Paneth and goblet cell homeostasis and increased endoplasmic reticulum stress in Agr2-/- mice. Dev Biol. 2010;338:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sato T, van Es JH, Snippert HJ, Stange DE, Vries RG, van den Born M, Barker N, Shroyer NF, van de Wetering M, Clevers H. Paneth cells constitute the niche for Lgr5 stem cells in intestinal crypts. Nature. 2010;469:415–418. doi: 10.1038/nature09637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tomasinsig L, Zanetti M. The cathelicidins—structure, function and evolution. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2005;6:23–34. doi: 10.2174/1389203053027520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lehrer RI, Ganz T. Cathelicidins: a family of endogenous antimicrobial peptides. Curr Opin Hematol. 2002;9:18–22. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200201000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sorensen OE, Borregaard N. Cathelicidins—nature’s attempt at combinatorial chemistry. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2005;8:273–280. doi: 10.2174/1386207053764602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lehrer RI, Selsted ME, Szklarek D, Fleischmann J. Antibacterial activity of microbicidal cationic proteins 1 and 2, natural peptide antibiotics of rabbit lung macrophages. Infect Immun. 1983;42:10–14. doi: 10.1128/iai.42.1.10-14.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Selsted ME, Brown DM, DeLange RJ, Lehrer RI. Primary structures of MCP-1 and MCP-2, natural peptide antibiotics of rabbit lung macrophages. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:14485–14489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Selsted ME, Ouellette AJ. Mammalian defensins in the antimicrobial immune response. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:551–557. doi: 10.1038/ni1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ganz T. Defensins: antimicrobial peptides of vertebrates. C R Biol. 2004;327:539–549. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ganz T, Selsted ME, Szklarek D, Harwig SS, Daher K, Bainton DF, Lehrer RI. Defensins. Natural peptide antibiotics of human neutrophils. J Clin Invest. 1985;76:1427–1435. doi: 10.1172/JCI112120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ayabe T, Satchell DP, Wilson CL, Parks WC, Selsted ME, Ouellette AJ. Secretion of microbicidal alpha-defensins by intestinal Paneth cells in response to bacteria. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:113–118. doi: 10.1038/77783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghosh D, Porter E, Shen B, Lee SK, Wilk D, Drazba J, Yadav SP, Crabb JW, Ganz T, Bevins CL. Paneth cell trypsin is the processing enzyme for human defensin-5. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:583–590. doi: 10.1038/ni797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scheetz T, Bartlett JA, Walters JD, Schutte BC, Casavant TL, McCray PB., Jr Genomics-based approaches to gene discovery in innate immunity. Immunol Rev. 2002;190:137–145. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065X.2002.19010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garcia AE, Osapay G, Tran PA, Yuan J, Selsted ME. Isolation, synthesis, and antimicrobial activities of naturally occurring theta-defensin isoforms from baboon leukocytes. Infect Immun. 2008;76:5883–5891. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01100-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tran D, Tran PA, Tang YQ, Yuan J, Cole T, Selsted ME. Homodimeric theta-defensins from rhesus macaque leukocytes: isolation, synthesis, antimicrobial activities, and bacterial binding properties of the cyclic peptides. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3079–3084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109117200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tang YQ, Yuan J, Osapay G, Osapay K, Tran D, Miller CJ, Ouellette AJ, Selsted ME. A cyclic antimicrobial peptide produced in primate leukocytes by the ligation of two truncated alpha-defensins. Science. 1999;286:498–502. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leonova L, Kokryakov VN, Aleshina G, Hong T, Nguyen T, Zhao C, Waring AJ, Lehrer RI. Circular minidefensins and posttranslational generation of molecular diversity. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;70:461–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Funderburg N, Lederman MM, Feng Z, Drage MG, Jadlowsky J, Harding CV, Weinberg A, Sieg SF. Human-defensin-3 activates professional antigen-presenting cells via Toll-like receptors 1 and 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:18631–18635. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702130104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Biragyn A, Coscia M, Nagashima K, Sanford M, Young HA, Olkhanud P. Murine beta-defensin 2 promotes TLR-4/MyD88-mediated and NF-kappaB-dependent atypical death of APCs via activation of TNFR2. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:998–1008. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1007700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Candille SI, Kaelin CB, Cattanach BM, Yu B, Thompson DA, Nix MA, Kerns JA, Schmutz SM, Millhauser GL, Barsh GS. A beta-defensin mutation causes black coat color in domestic dogs. Science. 2007;318:1418–1423. doi: 10.1126/science.1147880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmutz SM, Berryere TG. Genes affecting coat colour and pattern in domestic dogs: a review. Anim Genet. 2007;38:539–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2007.01664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tollner TL, Yudin AI, Tarantal AF, Treece CA, Overstreet JW, Cherr GN. Beta-defensin 126 on the surface of macaque sperm mediates attachment of sperm to oviductal epithelia. Biol Reprod. 2008;78:400–412. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.064071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tollner TL, Yudin AI, Treece CA, Overstreet JW, Cherr GN. Macaque sperm coating protein DEFB126 facilitates sperm penetration of cervical mucus. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:2523–2534. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taylor K, Clarke DJ, McCullough B, Chin W, Seo E, Yang D, Oppenheim J, Uhrin D, Govan JR, Campopiano DJ, MacMillan D, Barran P, Dorin JR. Analysis and separation of residues important for the chemoattractant and antimicrobial activities of beta-defensin 3. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:6631–6639. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709238200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang D, Biragyn A, Hoover DM, Lubkowski J, Oppenheim JJ. Multiple roles of antimicrobial defensins, cathelicidins, and eosinophil-derived neurotoxin in host defense. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:181–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cunliffe RN, Rose FR, Keyte J, Abberley L, Chan WC, Mahida YR. Human defensin 5 is stored in precursor form in normal Paneth cells and is expressed by some villous epithelial cells and by metaplastic Paneth cells in the colon in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2001;48:176–185. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.2.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salzman NH, Ghosh D, Huttner KM, Paterson Y, Bevins CL. Protection against enteric salmonellosis in transgenic mice expressing a human intestinal defensin. Nature. 2003;422:522–526. doi: 10.1038/nature01520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu Z, Ericksen B, Tucker K, Lubkowski J, Lu W. Synthesis and characterization of human alpha-defensins 4–6. J Pept Res. 2004;64:118–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.2004.00179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.White SH, Wimley WC, Selsted ME. Structure, function, and membrane integration of defensins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1995;5:521–527. doi: 10.1016/0959-440X(95)80038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Selsted ME, Harwig SS. Determination of the disulfide array in the human defensin HNP-2. A covalently cyclized peptide. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:4003–4007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Selsted ME, Tang YQ, Morris WL, McGuire PA, Novotny MJ, Smith W, Henschen AH, Cullor JS. Purification, primary structures, and antibacterial activities of beta-defensins, a new family of antimicrobial peptides from bovine neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:6641–6648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zimmermann GR, Legault P, Selsted ME, Pardi A. Solution structure of bovine neutrophil beta-defensin-12: the peptide fold of the beta-defensins is identical to that of the classical defensins. Biochemistry. 1995;34:13663–13671. doi: 10.1021/bi00041a048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Skalicky JJ, Selsted ME, Pardi A. Structure and dynamics of the neutrophil defensins NP-2, NP-5, and HNP-1: NMR studies of amide hydrogen exchange kinetics. Proteins. 1994;20:52–67. doi: 10.1002/prot.340200107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pardi A, Zhang XL, Selsted ME, Skalicky JJ, Yip PF. NMR studies of defensin antimicrobial peptides. 2. Three-dimensional structures of rabbit NP-2 and human HNP-1. Biochemistry. 1992;31:11357–11364. doi: 10.1021/bi00161a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hill CP, Yee J, Selsted ME, Eisenberg D. Crystal structure of defensin HNP-3, an amphiphilic dimer: mechanisms of membrane permeabilization. Science. 1991;251:1481–1485. doi: 10.1126/science.2006422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Szyk A, Wu Z, Tucker K, Yang D, Lu W, Lubkowski J. Crystal structures of human alpha-defensins HNP4, HD5, and HD6. Protein Sci. 2006;15:2749–2760. doi: 10.1110/ps.062336606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pazgier M, Li X, Lu W, Lubkowski J. Human defensins: synthesis and structural properties. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13:3096–3118. doi: 10.2174/138161207782110381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tanabe H, Ouellette AJ, Cocco MJ, Robinson WE., Jr Differential Effects on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication by alpha-defensins with comparable bactericidal activities. J Virol. 2004;78:11622–11631. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.21.11622-11631.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jing W, Hunter HN, Tanabe H, Ouellette AJ, Vogel HJ. Solution structure of cryptdin-4, a mouse Paneth cell alpha-defensin. Biochemistry. 2004;43:15759–15766. doi: 10.1021/bi048645p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rosengren KJ, Daly NL, Fornander LM, Jonsson LM, Shirafuji Y, Qu X, Vogel HJ, Ouellette AJ, Craik DJ. Structural and functional characterization of the conserved salt bridge in mammalian Paneth cell alpha-defensins: solution structures of mouse cryptdin-4 and (E15D)-cryptdin-4. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:28068–28078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604992200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McManus AM, Dawson NF, Wade JD, Carrington LE, Winzor DJ, Craik DJ. Three-dimensional structure of RK-1: a novel alpha-defensin peptide. Biochemistry. 2000;39:15757–15764. doi: 10.1021/bi000457l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kamdar K, Maemoto A, Qu X, Young SK, Ouellette AJ. In vitro activation of the rhesus macaque myeloid alpha-defensin precursor proRMAD-4 by neutrophil serine proteinases. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:32361–32368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805296200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maemoto A, Qu X, Rosengren KJ, Tanabe H, Henschen-Edman A, Craik DJ, Ouellette AJ. Functional analysis of the alpha-defensin disulfide array in mouse cryptdin-4. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:44188–44196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406154200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hadjicharalambous C, Sheynis T, Jelinek R, Shanahan MT, Ouellette AJ, Gizeli E. Mechanisms of alpha-defensin bactericidal action: comparative membrane disruption by cryptdin-4 and its disulfide-null analogue. Biochemistry. 2008;47:12626–12634. doi: 10.1021/bi800335e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zou G, de Leeuw E, Li C, Pazgier M, Li C, Zeng P, Lu WY, Lubkowski J, Lu W. Toward understanding the cationicity of defensins: Arg and Lys versus their noncoded analogs. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:19653–19665. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611003200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wu Z, Hoover DM, Yang D, Boulegue C, Santamaria F, Oppenheim JJ, Lubkowski J, Lu W. Engineering disulfide bridges to dissect antimicrobial and chemotactic activities of human beta-defensin 3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8880–8885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533186100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rajabi M, de Leeuw E, Pazgier M, Li J, Lubkowski J, Lu W. The conserved salt bridge in human alpha-defensin 5 is required for its precursor processing and proteolytic stability. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21509–21518. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801851200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Llenado RA, Weeks CS, Cocco MJ, Ouellette AJ. Electropositive charge in alpha-defensin bactericidal activity: functional effects of Lys-for-Arg substitutions vary with the peptide primary structure. Infect Immun. 2009;77:5035–5043. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00695-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mitchell DJ, Kim DT, Steinman L, Fathman CG, Rothbard JB. Polyarginine enters cells more efficiently than other polycationic homopolymers. J Pept Res. 2000;56:318–325. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3011.2000.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lehrer RI, Ganz T. Defensins of vertebrate animals. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:96–102. doi: 10.1016/S0952-7915(01)00303-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schneider T, Kruse T, Wimmer R, Wiedemann I, Sass V, Pag U, Jansen A, Nielsen AK, Mygind PH, Raventos DS, Neve S, Ravn B, Bonvin AM, De Maria L, Andersen AS, Gammelgaard LK, Sahl HG, Kristensen HH. Plectasin, a fungal defensin, targets the bacterial cell wall precursor Lipid II. Science. 2010;328:1168–1172. doi: 10.1126/science.1185723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schmitt P, Wilmes M, Pugniere M, Aumelas A, Bachere E, Sahl HG, Schneider T, Destoumieux-Garzon D. Insight into invertebrate defensin mechanism of action: oyster defensins inhibit peptidoglycan biosynthesis by binding to lipid II. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:29208–29216. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.143388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sass V, Schneider T, Wilmes M, Korner C, Tossi A, Novikova N, Shamova O, Sahl HG. Human beta-defensin 3 inhibits cell wall biosynthesis in Staphylococci. Infect Immun. 2010;78:2793–2800. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00688-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lehrer RI, Barton A, Daher KA, Harwig SS, Ganz T, Selsted ME. Interaction of human defensins with Escherichia coli. Mechanism of bactericidal activity. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:553–561. doi: 10.1172/JCI114198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lambert PA, Hammond SM. Potassium fluxes, first indications of membrane damage in micro-organisms. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1973;54:796–799. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(73)91494-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Orlov DS, Nguyen T, Lehrer RI. Potassium release, a useful tool for studying antimicrobial peptides. J Microbiol Methods. 2002;49:325–328. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7012(01)00383-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tincu JA, Menzel LP, Azimov R, Sands J, Hong T, Waring AJ, Taylor SW, Lehrer RI. Plicatamide, an antimicrobial octapeptide from Styela plicata hemocytes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:13546–13553. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211332200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shanahan MT, Vidrich A, Shirafuji Y, Dubois CL, Henschen-Edman A, Hagen SJ, Cohn SM, Ouellette AJ. Elevated expression of Paneth cell CRS4C in ileitis-prone SAMP1/YitFc mice: regional distribution, subcellular localization, and mechanism of action. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7493–7504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.083220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hristova K, Selsted ME, White SH. Interactions of monomeric rabbit neutrophil defensins with bilayers: comparison with dimeric human defensin HNP-2. Biochemistry. 1996;35:11888–11894. doi: 10.1021/bi961100d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hristova K, Selsted ME, White SH. Interactions of monomeric rabbit neutrophil defensins with bilayers: comparison with dimeric human defensin HNP-2. Biochemistry. 1996;35:11888–11894. doi: 10.1021/bi961100d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Satchell DP, Sheynis T, Kolusheva S, Cummings J, Vanderlick TK, Jelinek R, Selsted ME, Ouellette AJ. Quantitative interactions between cryptdin-4 amino terminal variants and membranes. Peptides. 2003;24:1795–1805. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2003.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Satchell DP, Sheynis T, Shirafuji Y, Kolusheva S, Ouellette AJ, Jelinek R. Interactions of mouse Paneth cell alpha-defensins and alpha-defensin precursors with membranes: prosegment inhibition of peptide association with biomimetic membranes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:13838–13846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212115200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hristova K, Selsted ME, White SH. Critical role of lipid composition in membrane permeabilization by rabbit neutrophil defensins. J. Biol Chem. 1997;272:24224–24233. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zeya HI, Spitznagel JK. Antimicrobial specificity of leukocyte lysosomal cationic proteins. Science. 1966;154:1049–1051. doi: 10.1126/science.154.3752.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zeya HI, Spitznagel JK. Cationic proteins of polymorphonuclear leukocyte lysosomes. II. Composition, properties, and mechanism of antibacterial action. J Bacteriol. 1966;91:755–762. doi: 10.1128/jb.91.2.755-762.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zeya HI, Spitznagel JK. Antibacterial and enzymic basic proteins from leukocyte lysosomes: separation and identification. Science. 1963;142:1085–1087. doi: 10.1126/science.142.3595.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yount NY, Wang MS, Yuan J, Banaiee N, Ouellette AJ, Selsted ME. Rat neutrophil defensins. Precursor structures and expression during neutrophilic myelopoiesis. J Immunol. 1995;155:4476–4484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ganz T, Sherman MP, Selsted ME, Lehrer RI. Newborn rabbit alveolar macrophages are deficient in two microbicidal cationic peptides, MCP-1 and MCP-2. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985;132:901–904. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1985.132.4.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Eisenhauer PB, Lehrer RI. Mouse neutrophils lack defensins. Infect Immun. 1992;60:3446–3447. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.8.3446-3447.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shanahan MT, Tanabe H, Ouellette AJ. Strain-specific polymorphisms in Paneth cell alpha-defensins of C57BL/6 mice and evidence of vestigial myeloid alpha-defensin pseudogenes. Infect Immun. 2011;79:459–473. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00996-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mackewicz CE, Yuan J, Tran P, Diaz L, Mack E, Selsted ME, Levy JA. Alpha-defensins can have anti-HIV activity but are not CD8 cell anti-HIV factors. AIDS. 2003;17:F23–F32. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200309260-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chalifour A, Jeannin P, Gauchat JF, Blaecke A, Malissard M, N’Guyen T, Thieblemont N, Delneste Y. Direct bacterial protein PAMPs recognition by human NK cells involves TLRs and triggers alpha-defensin production. Blood. 2004;104:1778–1783. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Obata-Onai A, Hashimoto S, Onai N, Kurachi M, Nagai S, Shizuno K, Nagahata T, Matsushima K. Comprehensive gene expression analysis of human NK cells and CD8(+) T lymphocytes. Int Immunol. 2002;14:1085–1098. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxf086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Agerberth B, Charo J, Werr J, Olsson B, Idali F, Lindbom L, Kiessling R, Jornvall H, Wigzell H, Gudmundsson GH. The human antimicrobial and chemotactic peptides LL-37 and alpha-defensins are expressed by specific lymphocyte and monocyte populations. Blood. 2000;96:3086–3093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ouellette AJ, Satchell DP, Hsieh MM, Hagen SJ, Selsted ME. Characterization of luminal Paneth alpha-defensins in mouse small intestine. J. Biol Chem. 2000;275:33969–33973. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004062200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ouellette AJ, Darmoul D, Tran D, Huttner KM, Yuan J, Selsted ME. Peptide localization and gene structure of cryptdin 4, a differentially expressed mouse Paneth cell alpha-defensin. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6643–6651. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.12.6643-6651.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Selsted ME, Miller SI, Henschen AH, Ouellette AJ. Enteric defensins: antibiotic peptide components of intestinal host defense. J Cell Biol. 1992;118:929–936. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.4.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Porter EM, Liu L, Oren A, Anton PA, Ganz T. Localization of human intestinal defensin 5 in Paneth cell granules. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2389–2395. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2389-2395.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhao C, Wang I, Lehrer RI. Widespread expression of beta-defensin hBD-1 in human secretory glands and epithelial cells. FEBS Lett. 1996;396:319–322. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)01123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ouellette AJ, Satchell DP, Hsieh MM, Hagen SJ, Selsted ME. Characterization of luminal Paneth cell alpha-defensins in mouse small intestine. Attenuated antimicrobial activities of peptides with truncated amino termini. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33969–33973. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004062200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Condon MR, Viera A, D’Alessio M, Diamond G. Induction of a rat enteric defensin gene by hemorrhagic shock. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4787–4793. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4787-4793.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Jones DE, Bevins CL. Paneth cells of the human small intestine express an antimicrobial peptide gene. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:23216–23225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tanabe H, Yuan J, Zaragoza MM, Dandekar S, Henschen-Edman A, Selsted ME, Ouellette AJ. Paneth cell alpha-defensins from rhesus macaque small intestine. Infect Immun. 2004;72:1470–1478. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.3.1470-1478.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ouellette AJ, Bevins CL. Paneth cell defensins and innate immunity of the small bowel. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001;7:43–50. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200102000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jones DE, Bevins CL. Defensin-6 mRNA in human Paneth cells: implications for antimicrobial peptides in host defense of the human bowel. FEBS Lett. 1993;315:187–192. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81160-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ouellette AJ, Hsieh MM, Nosek MT, Cano-Gauci DF, Huttner KM, Buick RN, Selsted ME. Mouse Paneth cell defensins: primary structures and antibacterial activities of numerous cryptdin isoforms. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5040–5047. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.5040-5047.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mastroianni JR, Ouellette AJ. Alpha-defensins in enteric innate immunity: functional Paneth cell alpha-defensins in mouse colonic lumen. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:27848–27856. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.050773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Darmoul D, Brown D, Selsted ME, Ouellette AJ. Cryptdin gene expression in developing mouse small intestine. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:G197–G206. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.1.G197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bry L, Falk P, Huttner K, Ouellette A, Midtvedt T, Gordon JI. Paneth cell differentiation in the developing intestine of normal and transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10335–10339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Mallow EB, Harris A, Salzman N, Russell JP, DeBerardinis RJ, Ruchelli E, Bevins CL. Human enteric defensins. Gene structure and developmental expression. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:4038–4045. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.8.4038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Salzman NH, Polin RA, Harris MC, Ruchelli E, Hebra A, Zirin-Butler S, Jawad A, Martin Porter E, Bevins CL. Enteric defensin expression in necrotizing enterocolitis. Pediatr Res. 1998;44:20–26. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199807000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ayabe T, Satchell DP, Pesendorfer P, Tanabe H, Wilson CL, Hagen SJ, Ouellette AJ. Activation of Paneth cell alpha-defensins in mouse small intestine. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5219–5228. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109410200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Quayle AJ, Porter EM, Nussbaum AA, Wang YM, Brabec C, Yip KP, Mok SC. Gene expression, immunolocalization, and secretion of human defensin-5 in human female reproductive tract. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:1247–1258. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Svinarich DM, Wolf NA, Gomez R, Gonik B, Romero R. Detection of human defensin 5 in reproductive tissues. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:470–475. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(97)70517-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Frye M, Bargon J, Dauletbaev N, Weber A, Wagner TO, Gropp R. Expression of human alpha-defensin 5 (HD5) mRNA in nasal and bronchial epithelial cells. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53:770–773. doi: 10.1136/jcp.53.10.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Com E, Bourgeon F, Evrard B, Ganz T, Colleu D, Jegou B, Pineau C. Expression of antimicrobial defensins in the male reproductive tract of rats, mice, and humans. Biol Reprod. 2003;68:95–104. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.005389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Grandjean V, Vincent S, Martin L, Rassoulzadegan M, Cuzin F. Antimicrobial protection of the mouse testis: synthesis of defensins of the cryptdin family. Biol Reprod. 1997;57:1115–1122. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod57.5.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wu ER, Daniel R, Bateman A. RK-2: a novel rabbit kidney defensin and its implications for renal host defense. Peptides. 1998;19:793–799. doi: 10.1016/S0196-9781(98)00016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Bateman A, MacLeod RJ, Lembessis P, Hu J, Esch F, Solomon S. The isolation and characterization of a novel corticostatin/defensin-like peptide from the kidney. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10654–10659. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Patil A, Hughes AL, Zhang G. Rapid evolution and diversification of mammalian alpha-defensins as revealed by comparative analysis of rodent and primate genes. Physiol Genomics. 2004;20:1–11. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00150.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ouellette AJ, Cordell B. Accumulation of abundant messenger ribonucleic acids during postnatal development of mouse small intestine. Gastroenterology. 1988;94:114–121. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(88)90618-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ouellette AJ, Pravtcheva D, Ruddle FH, James M. Localization of the cryptdin locus on mouse chromosome 8. Genomics. 1989;5:233–239. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(89)90051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ouellette AJ, Miller SI, Henschen AH, Selsted ME. Purification and primary structure of murine cryptdin-1, a Paneth cell defensin. FEBS Lett. 1992;304:146–148. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80606-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Salzman NH, Underwood MA, Bevins CL. Paneth cells, defensins, and the commensal microbiota: a hypothesis on intimate interplay at the intestinal mucosa. Semin Immunol. 2007;19:70–83. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Schneider T, Sahl HG. Lipid II and other bactoprenol-bound cell wall precursors as drug targets. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2010;11:157–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Bruhn O, Paul S, Tetens J, Thaller G. The repertoire of equine intestinal alpha-defensins. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:631. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Sparkes RS, Kronenberg M, Heinzmann C, Daher KA, Klisak I, Ganz T, Mohandas T. Assignment of defensin gene(s) to human chromosome 8p23. Genomics. 1989;5:240–244. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(89)90052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Ouellette AJ, Greco RM, James M, Frederick D, Naftilan J, Fallon JT. Developmental regulation of cryptdin, a corticostatin/defensin precursor mRNA in mouse small intestinal crypt epithelium. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:1687–1695. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.5.1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Selsted ME, Ouellette AJ. Defensins in granules of phagocytic and non-phagocytic cells. Trends Cell Biol. 1995;5:114–119. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(00)88961-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Linzmeier R, Michaelson D, Liu L, Ganz T. The structure of neutrophil defensin genes. FEBS Lett. 1993;321:267–273. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80122-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Ganz T. Biosynthesis of defensins and other antimicrobial peptides. Ciba Found Symp. 1994;186:62–71. doi: 10.1002/9780470514658.ch4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wei X, Eisman R, Xu J, Harsch AD, Mulberg AE, Bevins CL, Glick MC, Scanlin TF. Turnover of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR): slow degradation of wild-type and delta F508 CFTR in surface membrane preparations of immortalized airway epithelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 1996;168:373–384. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199608)168:2<373::AID-JCP16>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Huttner KM, Selsted ME, Ouellette AJ. Structure and diversity of the murine cryptdin gene family. Genomics. 1994;19:448–453. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Ouellette AJ. Paneth cell alpha-defensin synthesis and function. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;306:1–25. doi: 10.1007/3-540-29916-5_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]