Abstract

As multiparty interactions with single courses of coordinated action, workplace meetings place particular interactional demands on participants who are not primary speakers (e.g. not chairs) as they work to initiate turns and to interactively coordinate with displays of recipiency from co-participants. Drawing from a corpus of 26 hours of videotaped workplace meetings in a midsized US city, this article reports on multimodal practices – phonetic, prosodic, and bodily-visual – used for coordinating turn transition and for consolidating recipiency in these specialized speech exchange systems. Practices used by self-selecting non-primary speakers as they secure turns in meetings include displays of close monitoring of current speakers’ emerging turn structure, displays of heightened interest as current turns approach possible completion, and turn initiation practices designed to pursue and, in a fine-tuned manner, coordinate with displays of recipiency on the parts of other participants as well as from reflexively constructed ‘target’ recipients. By attending to bodily-visual action, as well as phonetics and prosody, this study contributes to expanding accounts for turn taking beyond traditional word-based grammar (i.e. lexicon and syntax).

Keywords: gaze, gesture, institutional interaction, interactional linguistics, meeting interaction, multimodality, multiparty interaction, turn taking

Introduction

Looking closely at turn taking in workplace meetings, this article focuses on multi-modal coordination between the actions of incipient speakers and those of their emerging recipients. In casual, non-institutional interaction, groups of four or more participants may schism into separate conversations (Egbert, 1997). Given that workplace meetings regularly include four or more participants sharing a single focus of action, institutionalized practices have developed for managing turn taking in such events (Boden, 1994; Drew and Heritage, 1992; Ford, 2008). In the interactional ecologies of workplace meetings, chairs command long periods of talk and, to some degree, manage the participation of others (Asmuß and Svennevig, 2009; Boden, 1994; Ford, 2008). Given the large number of potential speakers and recipients in meetings, and given the norm of a single focused sequence, meetings are characterized by long spates of single-party talk. These extended holds on the floor result in the requirement that other participants do specific kinds of work to gain speakership and to consolidate demonstrations of active recipiency on the parts of others. When such moves toward speakership are successful, other participants respond to the moves of incipient speakers by realigning their displays of recipiency (Ford, 2008; Mondada, 2007).1 Far from being a straightforward handing off of the floor, these realignments are fine-tuned interactional accomplishments.

Even for ordinary talk, as Harvey Sacks noted, simply beginning to speak does not entail having the floor in at least one understanding of that term:2

One wants to make a distinction between having the floor in the sense of being a speaker while others are hearers, and having the floor in a sense of being a speaker while others are doing whatever they please. One wants not merely to occupy the floor, but to have the floor while others listen. (Sacks, 1992: 683)

What are the interactional challenges that non-primary speakers in meetings face as they initiate turns in meetings? For our purposes, we would replace Sacks’s use of ‘hearers’ with ‘displayed recipients’, but like Sacks, we are interested in participants’ practices for pursuing visible displays of ‘hearing’ by others, and often particularly targeted others, in a meeting. In our data, self-selecting next speakers regularly employ mulitmodal practices as means for drawing such displays. Within split seconds in most cases, other participants respond to an incipient speaker with multimodal practices, practices that visibly embody shifts to new roles as now-attentive recipients of the new speaker’s talk. New speakers often, but not always, succeed in consolidating visible displays of recipiency within the first turn-constructional unit (TCU) of their turns. Incipient speakers and other meeting participants execute fine-tuned moves that result in changes in speakership, with the result being a seemingly seamless but actually collaborative and highly monitored management of turn transitions.

Pre-turn practices of potential next speakers include a constellation of vocal and bodily-visual moves, including displays of close monitoring of current speakers’ emerging turns; such displays by incipient speakers are interpretable as indicating heightened interest as current turns approach possible completion. Once a next turn by a non-primary speaker has been launched, these new speakers use additional practices to pursue displays of recipiency. In addition to work to consolidate recipiency from the group, new speakers often precisely index specific target addressees by means of the duration of the pursuits and by withholding smooth turn continuation until after a target recipient’s attention has been displayed.3 Building on the research of Charles Goodwin, in particular, the current article reports on multimodal practices for consolidating recipiency as employed by self-selecting new speakers in workplace meetings.

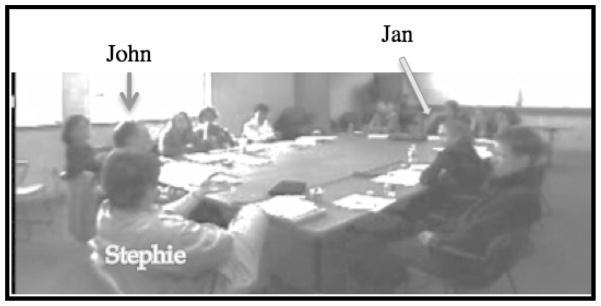

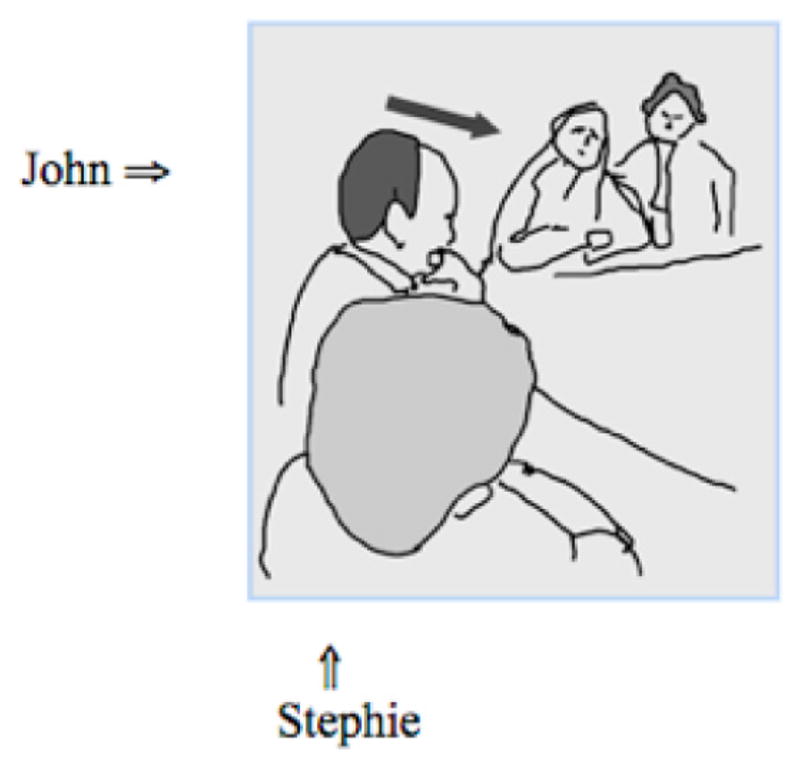

Before reviewing relevant literature and presenting our analyses, let us first address some key notions and terms we will use, as they may have different meanings for different readers. By referring to multimodal practices we mean to explicitly attend not only to lexico-grammatical forms, but also to phonetic, prosodic, and bodily-visual actions. We will at times use the expression floor as shorthand for a current but dynamic participation framework (Goodwin, 19904), an arrangement of participation roles at given points in the flow of a meeting. During the course of either the chair’s or another primary speaker’s turn, other participants may work to secure the floor, work that includes gaining displayed recipiency of particular other meeting participants. Figures 1 and 2, outline drawings of an interactional moment we examine later in this article, offer an initial sense of the change in displayed attention that new speakers work to achieve. In Figure 1, the participant John is gazing straight out in front of himself and slightly downward (gaze direction indicated by arrow) as Stephie begins speaking. In Figure 2, several seconds after Figure 1, we see that Stephie has secured a recipiency display from John: John has turned his head to gaze toward Stephie. As we will discuss later, the change in John’s gaze direction is occasioned by specific work by Stephie.

Figure 1.

John gazes frontward

Figure 2.

John’s gaze shifted toward Stephie

For our purposes, controlling the floor means having secured or consolidated displayed recipiency from other members of the meeting and/or from particular target recipients.

In the extracts we present, in addition to identifying chairs, we will also use the terms primary speaker and non-primary speaker to refer more generically to these interactionally constructed roles.5 While meeting chairs routinely produce long turns at talk, non-chairs may also become primary speakers, either through other-selection on the part of the chair or by self-selection. Our interest is in how participants who are not chairs and are not currently primary speakers secure the floor, as interpretable through responsive displays by recipients. It is the multimodal work that new speakers do to draw such recipiency displays that is the focus of our study.

Previous work related to turn taking and recipiency

A fundamental problem for social interactants involves how, on a moment-to-moment basis, they interactively and reflexively negotiate their roles as speakers and recipients. It is through fine-grained monitoring and negotiation that participants collaboratively achieve these fundamental and constantly shifting social positions in the local social organization of talk-in-interaction. The intricately managed interdependence of these roles has been demonstrated in myriad ways. First, that speakers’ turns are designed to project points of possible completion before they are reached, points that are simultaneously monitored and precisely acted upon by next speakers, is a core area of research on talk-in-interaction (De Ruiter et al., 2006; Jefferson, 1973; Levinson, in press; Sacks et al., 1974; Stivers et al., 2009). Beyond the precision of next speaker turn beginnings, it is significant that recipients of ongoing turns produce concurrent displays, verbal and visual actions, during the course of a turn’s unfolding. Research demonstrates that for the accomplishment of social action, that is, for interaction to occur, speech by one individual is not enough. At a minimum one recipient must be demonstrably constructing herself as a recipient (Goodwin, 1981, 2006; Goodwin and Goodwin, 2005; Heath, 1986; Mondada, 2007; Sacks, 1992). Verbal displays that evidence active recipiency include minimal lexical or verbal responses (Jefferson, 1984; Schegloff, 1982). In addition to lexico-grammatical practices, empirical research demonstrates that speakers employ a range of multimodal embodiments to elicit talk and/or displays of recipiency. Early studies on the import of prosodic and phonetic cues within the turn taking system include work by John Local, John Kelly, and Bill Wells, among others (Local and Kelly, 1986; Local et al., 1985, 1986). More recent research on phonetics and prosody in interaction can be found in collections by Barth-Weingarten et al. (2009, 2010) and Couper-Kuhlen and Ford (2004).

In a 1979 article, Charles Goodwin combined analysis of phonetics and gaze behavior to account for the interactive construction of a turn, thus moving CA in a decidedly multimodal direction. Since that time, gaze has received considerable attention in the field as a primary focus of inquiry (e.g. Goodwin, 1980, 1981; Rossano, 2006) and a supporting area for many other research agendas: gaze and children as recipients (Kidwell, 2005); in medical interactions (Frankel, 1983; Robinson, 1998); in reenactments (Sidnell, 2006); co-tellings (Hayashi et al., 2002). Likewise, bodily movements have been inspected in relation to displays of incipient speakership on the parts of recipients (e.g. Heath, 1984, 1986; Mondada, 2007; Streeck, 1993, 2009; Streeck and Knapp, 1992). Studies have established that speakers and recipients exhibit collaborative, multimodal displays as they formulate their talk and respond to one another (e.g. Hayashi, 2005; Lerner, 1991; Streeck, 1993; Streeck and Knapp, 1992). It has also been shown that in addition to pre-turn displays (pre-beginnings), turn-initial position is particularly consequential for achieving speakership and securing displayed recipiency (Jefferson, 1986; Schegloff, 1997; Streeck, 2009).

Recipient displays, both verbal and non-verbal, not only evidence recipients’ orientation to phases within an emerging turn, but they may also occasion or prompt changes to the current speaker’s turn trajectory (Goodwin, 1979, 1980, 1981; Schegloff, 1987). Upgraded and intensifying cues of recipiency may also serve, essentially, to hold the speaker accountable for talk; such actions demonstrate what Kidwell calls ‘recipient proactivity’ (1997).

For the current study of workplace meeting interaction, there is the added challenge that self-selecting next speakers must do special work to secure recipiency from other participants and, in some instances, what we term target recipients, within specialized speech exchange systems characterized by multiple participants focused on one course of action. Such specialized speech exchange systems include classrooms (Mortensen, 2009) and meetings (Deppermann et al., 2010; Ford, 2008; Mondada, 2007). Although the chair of a meeting normally has a degree of control over turn allocation, in our data, that control is not at all absolute. In the dynamics of workplace meetings there is increased potential for competition for attention between simultaneous self-selecting incipient speakers (Asmuß and Svennevig, 2009; Boden, 1994; Ford, 2008). Thus, their heightened demands are placed on incipient speakers as well as on other participants as they organize their recipiency displays.

For our current work, the key and most relevant research remains the work of Charles Goodwin (1979, 1980, 1981), whose research is, however, not focused on meeting interaction. In this article, we build on Goodwin’s foundational discoveries, demonstrating how, within the specialized speech exchange systems of meetings, hitches and repair initiators function alongside visible bodily movements to draw the attention of recipients and to provide fundamental resources for fine-tuned shifts in the organization of speakership and recipiency in these events. We contribute to a growing body of knowledge addressing how, in meeting interactions as well as in ordinary talk, speakers pursue recipiency displays through identifiable constellations of multimodal practices often within initial components of turns.

Data and approach

Our examples come from a corpus of 26 hours of videotaped workplace meetings in a mid-sized US city. The number of participants in meetings ranged from 7 to 19. All participants had been briefed as to the videotaping protocol and had provided written consent to being taped.

For our analyses, we have used the methods of conversation analysis (CA) (see Heritage and Atkinson, 1984) augmented by interactional linguistics (IL) (see Selting and Couper-Kuhlen, 2001).6 Our attention to phonetics and prosody was grounded first in auditory judgments.7 We followed up on our auditory judgments by performing acoustic measurements using PRAAT (Boersma and Weenink, 2010).

In the remainder of this article, we focus on four cases in which non-primary speakers and primary speakers deploy multimodal practices as they work to consolidate displayed recipiency.

Securing displayed recipiency

As reviewed above, participants regularly use a range of multimodal practices prior to the launching turns. In many of the instances we have analyzed in workplace meetings, recipients engage in visible and/or hearable turn-preparatory actions before launching a speaking turn. At precise points during the course of current speakers’ turns, recipients may engage in visual and vocal actions indicating possible preparation to speak. Such actions include gaze behavior, torso movement, hand gestures, and vocalizations. Some of these recipient activities simultaneously increase recipients’ visual access to the current speaker, that is, they display a recipient’s close monitoring of the current speaker’s developing turn and its progression toward completion. Because current speakers as well as other meeting participants are monitoring actions of the group, viewed together, the work of incipient speakers and the work of other participants form jointly achieved and reflexively organized relationships leading up to and precisely enacting coordinated shifts in participant organization. Although our focus here is on multimodal practices of speakers and recipients that emerge as a verbal turn is initiated, our extracts include pre-turn work as well, and we note this in our discussion of the extracts. Such pre-turn work is ultimately of a piece with and inseparable from the organization of turn taking in these meetings.

Extract 1: Stress and bodily-visual practices draw recipient gaze

Our first example involves finely orchestrated bodily-visual practices during the first TCU of an incipient speaker’s turn. The target recipient, in this instance as in others in our collection, executes a temporally precise coordinated responsive change in the direction of his bodily-visual orientation.

Extract 1 is from a meeting in which members of a medical group are reviewing current research on the treatment of osteoporosis. Ned, the meeting participant with the greatest expertise on osteoporosis, has been co-constructed as the leader of the group, the primary speaker, during this hour-long meeting. As 1 begins, Ned has been explaining the methodology for post-mortem bone density measurement in a study by a large pharmaceutical company. As he reports on the study, he expresses doubts about the research methods. In lines 7 through 9, Ned articulates concern about the exclusion of the head from the bone density measurement: ‘I find that kind of worrisome.’ After elaborating on the problematic nature of excluding the cranial bone (lines 11–15), Ned reasserts his negative assessment: ‘it just smells bad’ (line 16). It is the coordination of Gwen’s turn beginning with Ned’s responsive behavior that is our focus.

There is nothing in Ned’s talk or bodily-visual behavior that selects Gwen as next speaker, nor is there any specific knowledge distribution that might be at play. However, before she speaks, Gwen has engaged in bodily movements that display a heightened attentiveness. In the first TCU of her verbal turn (line 18), Gwen skillfully employs gesture and stress to secure a display of recipiency from Ned.

During Ned’s extended turn, Gwen begins to display visible interest through torso and head movements at line 4, just as Ned articulates decapitate, and at line 10, just after Ned has negatively assessed the pharmaceutical company’s methodology as worrisome. As Ned’s extended turn nears possible completion (lines 15–16), Gwen maintains a forward leaning position, holding her gaze on Ned. As Ned completes his extended turn, he moves both hands down toward the table and starts to gaze in the direction of his notes (i.e. not toward Gwen). It is at that point that Gwen speaks up (line 18). It is not just the fact of her speaking but also her artful use of both stress and hand gestures that occasion Ned’s precise responsive shift in displayed engagement:

(1) Medical meeting: Gwen drawing Ned’s gaze8 1 Ned: you can measure the right ha:nd, you can 2 measure the right a:rm, you can measure 3 the head, or you dec↑api#tate folks. (0.7) 4 Gwen: #head up, forward lean, gaze toward N 5 Ned: And #that’s what they did. So they did= 6 Gwen: #head down, gaze toward papers on table 7 Ned: =densitometric decapitation in this and in 8 the female study. (0.7) I find that kind of 9 worrisome, in that the #cranium is a big= 10 Gwen: #head up, forward lean, gaze toward Ned (Figure 3) 11 Ned: =reservoir of cortical bone, and there’s 12 still this issue that we’ll come to 13 about, are we robbing Peter to pay 14 Paul,=are we taking cortical bone 15 to put it into the tribecular component, 16 #and it-(.)it just smells ba:d. 17 Ned: #hands down toward table, gaze to notes on table (Figure 4) 18⇒ Gwen: # >Does it<# #↑scient#if#ically make #↑sense#to decapitate? [ ] [ [ ] [ ] 19 Gwen: #right hand up # # out & #down (1)# # down(2) # [ 20 Ned: #“cuts off” # trajectory of arms,/head/face # turns gaze toward G (Figure 5) 21 Ned: ((clears throat)) Well, they justify it by saying that we’ve 22 got all this other stuff, in our mouth, and certainly 23 [for people like me, that’s true. 24 Gwen: [∘oh∘

Though there is much to note in Gwen’s embodied actions before her speaking turn, our interest here is in the multimodal work she does to gain displayed recipiency from Ned (as well as others) when she speaks (lines 18–19). Gwen maintains a forward lean and gaze direction (toward Ned) from lines 10 through 16. As Ned completes his extended turn, he begins to move his arms toward the table and his gaze toward the papers in front of him. It is during the course of these movements by Ned that Gwen speaks. As only one person in a field of 14 potential speakers, in order to gain the floor Gwen must not only speak, but she must also secure the displayed recipiency of her addressee, Ned. The prosodic pattern of her emerging turn (changes in loudness, duration, and pitch height) places stress on scientifically and sense. Within the modality of sound, then, Gwen’s stress on these words constitutes a prosodic method for drawing recipient attention.

Simultaneous with her verbal action, Gwen moves her right hand both outward (toward the middle of the table) and downward, literally reaching into Ned’s visual field. Her two right hand motions reach their full extensions toward the table with each stressed word. Thus, by working with the visual and auditory fields together, Gwen formulates a strong bid for a recipiency display by Ned, her target addressee.

Indeed, before Gwen completes the word scientifically, Ned begins to move his body in a coordinated responsive display. Recall that as Ned finished his extended turn, he began to move his arms and his gaze direction toward the papers on the table in front of him (line 16–17; Figure 4). Importantly, it is not Gwen’s first vocal signal that occasions Ned’s shift in attention display. Rather, as Gwen articulates the first syllable of scientifically, Ned abruptly halts the trajectory of his hands and the movement of his gaze. Ned cuts off the projectable course of the embodied action he set in motion in lines 16–17. In a reversal of his action trajectory, Ned shifts his gaze up and to his left, toward Gwen. Ned’s embodied movements formulate a visual cut off of the ‘next movement due’ in his ongoing action, a cut off akin to the familiar delay of next item due associated with verbal repair initiation (Schegloff et al., 1977). Thus, Ned visibly abandons the body movements he started as he completed his extended turn, and he performs a visible redirection of his body and gaze to display a new orientation, that of a recipient of Gwen’s turn-in-progress.

Figure 4.

Line 18, does it

In this first example, we see that Gwen uses stress and gesture in her first TCU as a means to draw the displayed attention of her target recipient. Gwen’s multimodal production quickly and efficiently draws a temporally coordinated responsive display from Ned, whose head, gaze, arm/hand movement, and torso direction were clearly not aimed toward Gwen at the outset of her verbal turn. Ned’s observable reversal in the visible trajectory of his embodied action supports our proposal that it is Gwen’s precise use of stress and gesture within the first TCU of her turn, not just her turn initiation in itself, that guides the local restructuring of participant roles such that she, an erstwhile non-primary speaker, is constructed as taking a socially ratified turn in the meeting.

In our next example, we explore the precision with which a specific kind of marked phonetic production is deployed to guide a local change in display of participant roles.

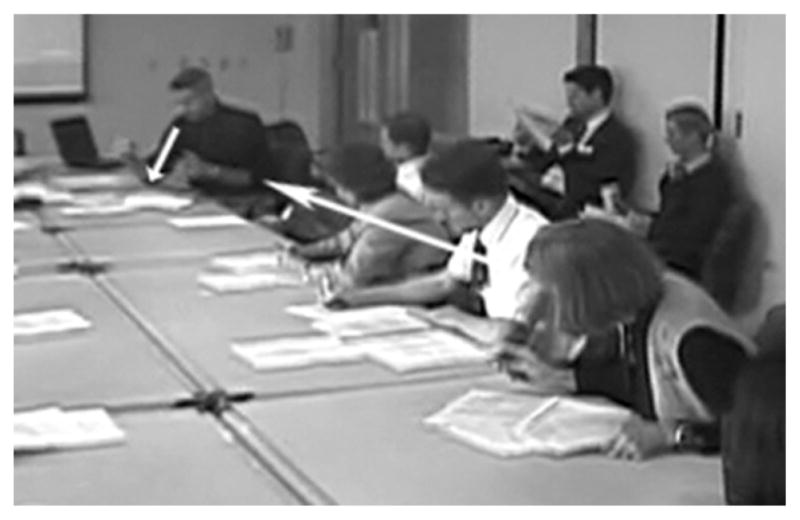

Extract 2: Turn-initial sound stretch draws recipient gaze

Our next case involves the deployment of an extended phonetic production/articulation during the first TCU of a new speaker’s turn. The target recipient executes a coordinated responsive change in the direction of her bodily-visual orientation, and she displays recipiency to the new speaker. Extract 2 is from a meeting of a university committee on diversity. As part of the university’s commitment to hiring more women and persons of color, the committee has been considering ways to improve search committee protocols. Jan, the committee chair, is sharing strategies for diversifying hiring. Beth, the non-primary speaker immediately to Jan’s left, has demonstrated heightened interest in key points of Jan’s report. Beth’s embodied practices up to the point where our extract begins have not developed into explicit bids of speakership. What we attend to in this extract is the way in which, when Beth does speak, she works to gain displayed recipiency from Jan.

As the extract begins, Jan has been speaking for over four and a half minutes. Pam, across the table and to the right of Jan, produces a barely audible assessment (line 5), overlapping with Jan (line 4). Jan produces an open-class repair initiator in line 6, ‘hm:::?’ (Drew, 1997), followed by a candidate understanding of Pam’s turn (line 6). Pam responds (line 7) with a repeat of her original assessment. In what follows this sequence, Jan moves to close the topic and the agenda item, introducing a summative move with ‘and so’ (Jucker and Ziv, 1998; Schiffrin, 1987). With a steady decline in pitch and loudness, Jan’s prosody indicates she is nearing the possible end of this TCU.9 In the bodily-visual modality, as she produces this TCU, she gazes toward the agenda sheet on the table in front of her. At this point, Beth displays interest by moving her body closer to Jan’s and holding her gaze direction toward Jan (line 9). However, Jan’s facing direction remains downward toward her meeting agenda (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Beth gazes toward Jan (line 9)

(2) Diversity Committee: Beth drawing Jan’s gaze 1 Jan: so that (.) i-if you become a little aware of 2 these issues then maybe you can sorta fight 3 against these prejudices an an and the:n ah 4 accountability is a [( ) 5 Pam: [∘∘It’s a splendid idea,∘∘ 6 Jan: hm:::? (Do) you like [that? 7 Pam: [∘It’s a splendid idea.∘ 8 Jan: and so for that #I’m going to work with Maya= 9 Beth: # turns toward J (Fig. 6) 10 Jan: =on that ∘this summ[er∘ I #think that’ll∘] 11⇒Beth: [s::o(w)#Valian ]talked about= 12⇒Jan: #gazes to B, eyebrows up (Fig. 7) 13 Beth:=accountability: [An’ an’ did- have data on:: 14 Jan: [Yeah,

At line 11, beginning in overlap with Jan on the final syllable of summer, Beth initiates a turn. During the course of Beth’s extended production of the sibilant on her first word, so, Jan initiates and completes a turn of her head toward Beth. There is a tight coordination of Beth’s turn initiation and Jan’s responsive abandonment of the course of her projected action, with the change in Jan’s lexico-grammatical and visual orientations (lines 10, 12; Figures 6 and 7). Based upon our auditory judgments we note that the [s] in Beth’s turn-initial so is produced with a significant sound stretch. The lengthening of this sound works as a possible repair initiation, creating a hearable delay of the next item due (here the next sound due beyond the [s]). Beth’s extended articulation of this sound serves to draw Jan’s displayed recipiency.10 Furthermore, in a coordinated manner, Beth withholds continuation of her TCU until Jan’s gaze is secured.

Figure 7.

Jan turns toward Beth (line 12)

In order to further ground our auditory impression that Beth’s [s] is extended, we measured this [s] and found the duration to be 0.464 seconds. This duration is four times the average length of the deployment reported for [s] natural speech as reported by Lieberman and Blumstein (1988). We then looked at how Beth’s production of [s] in this instance compares with her production of the sound in other instances, based on a collection of 73 additional word initial [s] articulations in recordings of Beth’s speech. Our measurements of these cases supports our auditory judgment that this [s] is particularly long for Beth. Among the other cases, Beth produces instances of word-initial [s] with durations between 0.027 an 0.249 seconds, with a median of 0.0165 seconds).11

A more appropriate comparison of initial [s] productions would focus not just on word-initial [s] but specifically on [s] in turn initial position. In the larger collection, we isolated four instances that were not only word initial but also turn initial. The measurements of those four turn initial productions of [s] are uniformly much shorter in duration than Beth’s turn initial [s] in extract 2, line 11, ranging from 0.040 to 0.135 seconds, as compared with the focal instance, which has a duration of whereas 0.464 seconds. This more interactionally relevant comparison provides strong support for our observation that the duration of Beth’s turn-initial [s] in line 11 is salient and capable of serving as a practice for precisely guiding and securing the displayed recipiency of a specific participant, the meeting chair, Jan. As noted above, Jan indeed executes a split second response to Beth’s extended articulation of the sibilant [s]. As Beth produces the [s] in so, Jan rotates her head 90 degrees, aligning her gaze with Beth’s, while raising her eyebrows (Figure 7). Once Jan’s display of recipiency is thus secured, Beth continues her projected turn (lines 11 and 13).

Comparing the function and outcome to Gwen’s multimodal work to gain Ned’s displayed recipiency in extract 1, we see another constellation of multimodal practices in Beth’s turn initiation in extract 2. Beth effectively uses the movement of her trunk position and gaze direction, leaning toward Jan as she launches her turn. Beth also employs a hearable and interactionally consequential turn-initial sound stretch to effectively draw Jan’s gaze. Beth continues her extended articulation of the initial voiceless sibilant, the first sound in her turn, precisely until Jan completes her head turn and her gaze is clearly toward, and as such acts to summons, her targeted recipient.

With extract 2, we see again that a self-selecting non-primary speaker speaks up and successfully draws the gaze of a non-gazing primary speaker. In this exchange, the phonetic articulation of the initial sound of the turn is produced such that the progressivity of the TCU is delayed until the target recipient has responsively reoriented her body to display recipiency to the new speaker’s turn.

We will look at two further variations in the contingent reorientation of speakership, from the same diversity committee meeting as in extract 2. We first look at a case where, once again, phonetic modulation attracts the gaze of a non-gazing recipient.

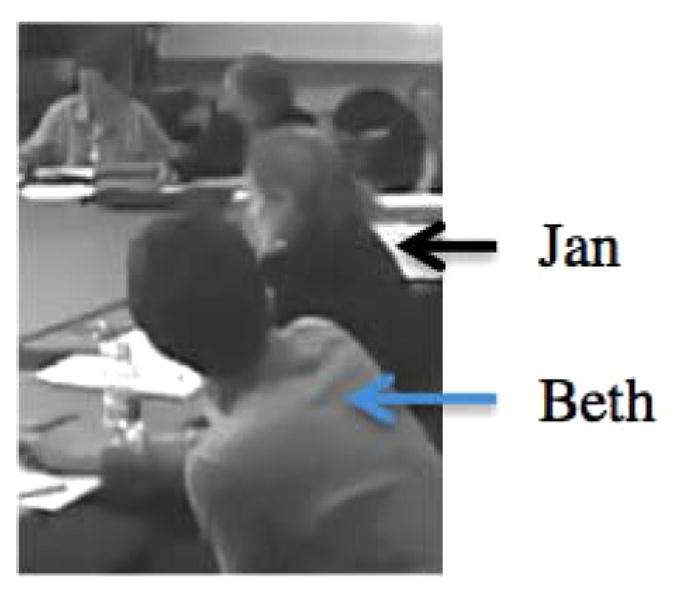

Extract 3: Cut-off and restart draw recipient gaze

In the next extract, the current speaker, Mary, is not the chair, but she has been granted an extended turn by the chair and has, consequently, been constructed as the current primary speaker. At line 9, she comes to a point of possible completion and a pause ensues. At lines 9 and 10, both Mary and another participant, Pam, self-select, with Mary starting first. Having begun speaking in overlap with Mary, Pam uses a classic restart repair both to manage the overlap and to successfully draw Mary’s displayed recipiency:

(3) Diversity Committee: Pam drawing Mary’s gaze 1 Mary: I’ve begun to call: (.) folks, I mean six out of the 2 six people I have contacted expressed interest in 3 the twenty-four hours, and so, I’m really enthusiastic, 4 I mean I’ll start tomorrow morning, and u:m, we have 5 <forty women>, # who agreed to do it in the next= 6 Beth: #((3 subdued hand claps)) 7 Mary: =few weeks, ∘so$∘, (($= creaky voice)) 8 (.) 9 Mary: ∘(all)[>(s #Bev is # )< m::∘ 10⇒Pam: [Dy-#>D’you #have< specific questions you’re asking, 11 Mary: #Fig. 8 → #Fig. 9 12 Mary: We: have a protocol. 13 (.) 14 Mary: Flor has a copy, (∘ to share, if you’re interested.∘)

Mary, in the role of local primary speaker (though not chair), has negotiated an extended turn in which she has reported her progress with setting up interviews with women colleagues in order to gain information relevant to the committee’s charge. Mary reaches possible completion of her news report (line 7) through a trail off on the quiet and creaky-voiced production of so (Local and Kelly, 1986). However, at that juncture there is no immediate uptake. After a micropause (line 8), Mary starts to extend her talk, but Pam also starts up, launching her turn one syllable into Mary’s continuation (lines 9–10). Of interest for the study of multimodal practices for securing recipiency in meetings are Pam’s cut-off repair and Mary’s immediately responsive gaze movement (Figures 8 and 9).

Figure 8.

Dy#

Figure 9.

>D’you

In line with Goodwin’s findings on hitches used to draw the gaze of non-gazing recipients, Pam cuts off her sound production at the beginning of her turn. Different from Goodwin’s cases from ordinary (albeit multiparty) interaction, Pam is a meeting participant and is 1 among 12 possible next speakers. Unlike Beth, in extract 2, Pam has done no previous visible or hearable pre-beginning work to indicate her interest in speaking. Nevertheless, Pam’s cut-off and restart quickly and successfully result in Mary’s responsive head and gaze movement along with an accompanying trail off of Mary’s ongoing utterance (indecipherable because of its low volume and Pam’s overlapping talk). Given that Pam initiates her turn in overlap with Mary’s continuation, Pam’s restart repair does double-duty: it not only works toward resolving what is developing into a significant overlap (Schegloff, 2000), but it also consolidates displayed recipiency, the latter being of interest for the current study.

With extracts 1 through 3, we have demonstrated how current non-primary speakers use multimodal practices, both visible and hearable, to draw displays of recipiency from non-gazing participants within initial TCUs. In our final case, we illustrate how a new speaker may find it necessary to work beyond an initial TCU in order to consolidate recipiency. In this case, the continued work also reflexively constructs one specific meeting participant as the new speaker’s target recipient.

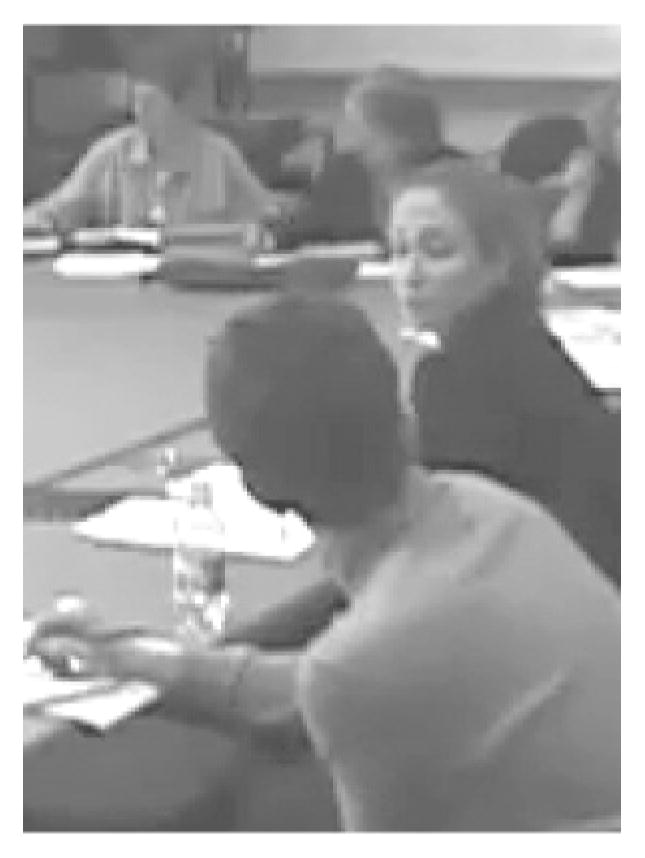

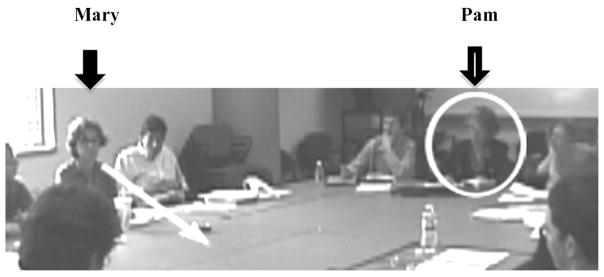

Extract 4: Repair initiation beyond first TCU draws target recipient gaze

In extract 4, Stephie, a self-selecting speaker not previously acting as a primary speaker, engages in rather elaborate work to delay her turn continuation until she secures the gaze of one specific participant. By the end of her first TCU, Stephie has quickly and effectively drawn recipiency displays from multiple other participants in the meeting, including the meeting chair. However, Stephie proceeds to produce cut-offs and delays until she has successfully drawn the gaze of John, seated directly to her left.

In this meeting of the diversity committee, among the 13 participants a subset of three are from the same college, the College of Applied Sciences (see Figure 10).12 John, the person Stephie constructs as a primary or target recipient, is the dean of her college while Stephie is a faculty member of one among several departments in the college. Of relevance to this extract is the fact that Stephie’s department stands out for using social science methodologies, whereas all the other departments use methods more typically associated with engineering and physical sciences. This is essential ethnographic background for interpreting Stephie’s insider reference to the other side of the college (lines 8–9), which prompts laughter from John (line 10) but from no one else at the meeting.

Figure 10.

Seating of participants of interest in extract 4

Note: Jan = Committee chair of meeting, professor of Microbiology; Stephie = Professor in a department within the College of Applied Sciences; John = Dean, College of Applied Sciences.

As the extract begins, Stephie, an erstwhile non-primary speaker, moves into speakership in part through multiple multimodal actions before she begins her lexico-grammatical turn. These practices include an audible in-breath and a hand raise at the beginning of line 5:

(4) Diversity Committee: Stephie draws gaze from John

1 J: Summer school. >∘anyway.∘< (.)It’ll be fun

2 to work ou:t, I think.

4 (0.3)

5 S: # .hh # Can I make a- (.)brief comment on tha:t,

# hand raise #

6 I- yuh- uhm:

7 (1.0)

8 S: Being on the other side of the

9 co(h)lleg(h)[e, (0.6)

10 J: [huh eh heh

11 S: ↑We’ve never had a ↑search committee

12 in our ∘(department).∘

In her first TCU, one that projects a multi-unit turn, she produces a single hitch with make a-. As she continues into her second TCU, she cuts off and restarts twice (I- yuh-) and then produces a hesitation token, which is itself stretched (uhm:). Given what we know about the effectiveness of such hitches at consolidating displayed recipiency, we would expect that Stephie would have gained such displays by the end of line 6. Indeed, by that point, most of the other meeting participants, including the meeting chair (Jan), are gazing toward Stephie. However, John, seated just to Stephie’s left, is still gazing toward the middle of the table (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

John’s gaze at end of line 6

At line 7, Stephie pauses for a full second. It is only during this pause, this yet further delay of the next item due, that John orients as a recipient. During the pause, John finally turns his head and gazes toward Stephie. Just as John’s gaze reaches her, Stephie proceeds further with her projected turn, producing a laugh-infused reference to the other side of the co(h)lleg(h)e (lines 8–9). Her (0.6) delay at line 9 comes as she and John maintain gaze contact and as John laughs in response to the insider reference to the different sides of the college of which John is dean (as noted above).13

Only after she secures John’s display of attention, one particular target recipient’s gaze, does Stephie continue her turn. This reflexively constructs John as a key recipient, perhaps the unique participant, for whom Stephie is building this turn. As her turn continues beyond what we are able to examine here, it becomes clear why John’s recipiency is important to Stephie: Stephie develops her turn into an action specifically disaffiliative with a proposal John has just made and which would very directly and exclusively affect the College of Applied Sciences.14

In extract 4, we see how another non-primary speaker moves to a speaker role through multiple means. In addition, we see that securing the displayed recipiency of multiple other participants, including the meeting chair, is not treated as sufficient to construct the floor or participant framework that Stephie is evidently pursuing. Only when she has John’s displayed recipiency does she move forward with the ‘brief comment’ she projected had at line 5. By her delays and hitches, her repair initiations, and by extending them until she secures John’s gaze, Stephie constructs John as a target recipient. Not only is speaking up in itself treated as insufficient, but the work of the new speaker in coordination with recipient(s) again demonstrates fine-tuned monitoring and coordination as the participation format is shifted and displayed recipiency is secured.

What we hope to have shown through the four extracts we have analyzed is that multimodal practices – mutually elaborating combinations of lexico-grammar, prosody, and embodied action – are well-adapted for the crucial work of securing recipiency in meetings. Our first extract illustrates a new speaker’s use of prosodic stress, upper body movement, and gesture within the visual field of her target recipient, all of these working together to consolidate recipiency display. Extracts 2–4 further demonstrate how repair initiation practices and their temporal deployment to prompt recipient gaze are usefully adapted for meetings wherein non-primary speakers must do special work to establish their control of the floor. In all cases where displayed recipiency is at issue, we find tight coordination between verbal and bodily actions of both speakers and potential recipients. Incipient speakers closely monitor the displayed attention of recipients, and recipients work responsively to display that they are positioning themselves as attentive addressees. Securing recipiency is accomplished interactionally in a fine-grained and tight temporally coordinated manner.

Conclusion

Our goal in this article has been to contribute to a multimodal account for interactionally distributed and tightly temporally organized practices of securing recipiency in work-place meetings. An omnirelevant task for interactants is the management of speakership, including turn taking and displays of recipiency. The mere fact that one person begins to speak does not ensure she has the floor (Sacks, 1992), and the dynamics of workplace meetings bring this issue into particular relief. Meetings are specialized institutional activities comprising multiple persons with one focus; they have controlled agendas and special turn-taking roles for leaders as opposed to other participants. These factors affect the distribution, coordination, and negotiation of speakership. In examining the work that non-primary speakers do in reflexive coordination with other participants (emerging recipients), we find that practices used to attract co-gazing recipients in ordinary interaction are well-adapted for the more specialized speech exchange systems of meetings.

In this article, then, we have looked at turn initiations in meetings as particular sites in which self-selecting incipient speakers, specifically non-chairs or non-primary speakers, must do special work to gain the displayed recipiency of others, and sometimes particular others, among a range of potential next speakers. Among the observations we have illustrated in our analyses are the following:

Notions of primary speakership and non-primary speakership (i.e. not just the role of meeting chair) are interactionally consequential in accounts for turn taking in meetings. Given that multiple participants are non-primary speakers, meetings demand particular interactional work when a non-primary speaker self-selects and attempts to gain ratified speakership.

Self-selecting, non-primary speakers make effective use of specific bodily-visual actions to pursue displayed attention from recipients, often doing so within the first TCU of their turn.

Self-selecting, non-primary speakers make effective use of phonetic and/or lexico-grammatical practices associated with repair to introduce delays, delays extended precisely to coordinate with responsive actions on the parts of recipients. Delays end when recipiency is secured.

Self-selecting, non-primary speakers are capable of skillfully delaying smooth continuation of projected turns in such a way as to require some notion of the reflexive construction of a target recipient in accounts of turn construction in meeting interaction.

With this article, we hope to have expanded multimodal accounts of interaction in workplace meetings (Asmuß and Svennevig, 2009). In addition, by attending to participants’ coordination of bodily-visual actions, phonetics, and prosody, our study contributes to expanding accounts for turn taking beyond traditional word-based grammar (i.e. lexicon and syntax).

Figure 3.

Line 10, Gwen leans forward and looks toward Ned

Figure 5.

Line 18, scient#if#

Figure 12.

John’s gaze shift during pause at line 7

Acknowledgments

Our thinking for this project has benefitted from input from members of data sessions and collegial discussions, particularly from Veronika Drake, Barbara Fox, Junko Mori, and Doug Maynard. Jan Svennevig guided our project from the beginning, and we received valuable comments from Mie Femø Nielsen and an anonymous reviewer. We hope that these colleagues see the imprint of their suggestions, but we remain responsible for the ultimate product.

Funding

This publication was made possible by R01GM088477 from the National Institutes of Health. The project and material is also based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under award number 0123666. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of either funding source.

Biographies

Cecilia E. Ford is Professor of English and Sociology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and an affiliate of Gender and Women’s Studies, Second Language Acquisition, and the Women in Science and Engineering Leadership Institute. Her longstanding research agenda involves broadening our understanding of language to account for its inextricable interconnectedness with social structuring. She is also committed to interdisciplinary research and application aimed at social equity.

Trini G. Stickle is a doctoral student in English Language and Linguistics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her current interests include using conversation analysis in tandem with interactional linguistic methods, to discover how participants in multiparty talk use multimodal means as they construct one another as knowing or unknowing participants entitled to talk and with rights and responsibilities regarding both the topics and the actions of their talk.

Footnotes

Also see Mortensen (2009) on initiating turns in classroom interaction.

See Edelsky (1981) for an early sociolinguistic interpretation of the concept of ‘floor’ in a workplace meeting.

Our observations regarding repair initiation in pursuit of recipient gaze is directly in line with Goodwin’s now classic discovery of prosodic work in pursuit of recipient gaze (Goodwin, 1979, 1980).

Marjorie Goodwin’s use of this notion builds on Goffman’s (1979) notion of footing. However, her approach develops a more contingent and dynamic perspective on the locally coordinated nature of interaction.

We note that not only chairs but also others with authority in an institution may construct themselves and be reciprocally constructed by others as having entitlement, an interactional right-of-way, to self-select with minimal work beyond simply speaking up. Space limitations preclude discussion of such cases here.

For CA scholars the commitment is most strongly related to accounting for social actions (Heritage and Atkinson, 1984). IL scholars also focus on the connections between social actions and linguistic forms. More specifically, they look to naturally occurring language to inform linguistic theory and to further their understanding of linguistic typology.

Exemplar studies of phonetics and prosody for conversation include Couper-Kuhlen (1993) and Kelly and Local (1989), and studies collected in Barth-Weingarten et al. (2010), Couper-Kuhlen and Ford (2004), and Couper-Kuhlen and Selting (1996). For methodological ‘imperatives’, see Local and Walker (2005, 2008).

Jeffersonian transcription symbols are used, with the addition of hatch marks (‘#’) at points where analytically relevant bodily visual movement is described. Descriptions are in the line below the talk and are in italicized, Times New Roman font. Where multiple embodied actions occur with a span of talk, slash marks (‘/’) are inserted to mark their beginnings.

See Raymond (2004) on stand-alone so.

It is worth noting that [s] itself is one of the most phonetically turbulent English phonemes: an unvoiced alveolar fricative, the sibilant [s], making it a good sound for prompting co-participants’ attention.

A single, phrase-medial [s] measuring 0.383 seconds, comes closest in duration to our focal. This [s] occurs in the word see and is produced with added emphasis on the [s] rather than the vowel in the following phrase: ‘but that’s just the sort to s::ee what’s going on in the university’.

Pseudonym for college name.

No one else laughs, though the associate dean of the same college does smile.

For more extensive discussion of this case, see Ford (2008) and Ford and Fox (n.d.).

Reprints and permission: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

References

- Asmuß B, Svennevig J. Meeting talks: An introduction. Journal of Business Communication. 2009;46(1):3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Barth-Weingarten D, Dehé N, Wichmann A, editors. Where Prosody Meets Pragmatics. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Barth-Weingarten D, Rebar E, Selting M, editors. Prosody in Interaction. Amsterdam: Benjamins; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Boden D. The Business of Talk: Organizations in Action. Cambridge: Polity Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Boersma P, Weenink D. Praat: Doing phonetics by computer. Computer program, Version 5.2. 2010 Available at: http://www.praat.org/

- Couper-Kuhlen E. English Speech Rhythm: Form and Function in Everyday Verbal Interaction. Amsterdam: John Benjamins; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Couper-Kuhlen E, Ford CE, editors. Sound Patterns in Interaction. Amsterdam: John Benjamins; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Couper-Kuhlen E, Selting M, editors. Prosody in Conversation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Deppermann A, Schmitt R, Mondada L. Agenda and emergence: Contingent and planned activities in a meeting. Journal of Pragmatics. 2010;42:1700–1718. [Google Scholar]

- de Ruiter JP, Mitterer H, Enfield NJ. Projecting the end of a speaker’s turn: A cognitive cornerstone of conversation. Language. 2006;82:515–535. [Google Scholar]

- Drew P. ‘Open’ class repair initiators in response to sequential sources of trouble in conversation. Journal of Pragmatics. 1997;28:69–101. [Google Scholar]

- Drew P, Heritage J. Talk at Work. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Egbert MM. Schisming: The collaborative transformation from a single conversation to multiple conversations. Language and Social Interaction. 1997;30(1):1–51. [Google Scholar]

- Edelsky C. Who’s got the floor? Language in Society. 1981;10(3):383–421. [Google Scholar]

- Ford CE. Women Speaking Up: Getting and Using Turns in Workplace Meetings. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ford CE, Fox BA. Reference and repair in participant alignment practices. Department of English, University of Wisconsin-Madison; n.d. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Frankel RM. The laying on of hands: Aspects of the organization of gaze, touch, and talk in a medical encounter. In: Fisher S, Todd AD, editors. The Social Organization of Doctor–Patient Communication. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics; 1983. pp. 19–54. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Footing. Semiotica. 1979;25:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin C. The interactive construction of a sentence in natural conversation. In: Psathas G, editor. Everyday Language: Studies in Ethnomethodology. New York: Irvington; 1979. pp. 97–121. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin C. Restarts, pauses, and the achievement of a state of mutual gaze at turn beginning. Sociological Inquiry. 1980;50:272–302. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin C. Conversational Organization: Interaction between Speakers and Hearers. New York: Academic Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin C. Retrospective and prospective orientation in the construction of argumentative moves. Text & Talk. 2006;26(4):443–462. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin C, Goodwin MH. Participation. In: Duranti A, editor. A Companion to Linguistic Anthropology. Oxford: Blackwell; 2005. pp. 222–244. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin MH. He-Said-She-Said: Talk as Social Organization among Black Children. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi M. Joint turn construction through language and the body: Notes on embodiment in coordinated participation in situated activities. Semiotica. 2005;156(1/4):21–53. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi M, Mori J, Takagi T. Contingent achievement of co-tellership in a Japanese conversation: An analysis of talk, gaze, and gesture. In: Ford CE, Fox BA, Thompson SA, editors. The Language of Turn and Sequence. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. pp. 81–122. [Google Scholar]

- Heath C. Talk and recipiency: Sequential organization in speech and body movement. In: Atkinson JM, Heritage J, editors. Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1984. pp. 247–265. [Google Scholar]

- Heath C. Body Movement and Speech in Medical Interaction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Heritage J, Atkinson JM. Introduction. In: Atkinson JM, Heritage J, editors. Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1984. pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson G. A case of precision timing in ordinary conversation: Overlapped tag-positioned address terms in closing sequences. Semiotica. 1973;9(1):47–96. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson G. Notes on some orderlinesses of overlap onset. In: d’Urso V, Leonardi P, editors. Discourse Analysis and Natural Rhetoric. Padua: Cleup Editore; 1984. pp. 11–38. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson G. Notes on ‘latency’ in overlap onset. Human Studies. 1986;9(2/3):153–183. [Google Scholar]

- Jucker AH, Ziv Y. Discourse Markers: Descriptions and Theory. Amsterdam: Benjamins; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J, Local J. Doing Phonology. Manchester: Manchester University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kidwell M. Demonstrating recipiency: Knowledge displays as a resource for the unaddressed participant. Issues in Applied Linguistics. 1997;8:85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kidwell M. Gaze as social control: How very young children differentiate ‘The Look’ from a ‘Mere Look’ by their adult caregivers. Research on Language and Social Interaction. 2005;38(4):417–449. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner G. On the syntax of sentences in progress. Language in Society. 1991;20:441–458. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson SC. Action formation and ascription. In: Sidnell J, Stivers T, editors. Handbook of Conversation Analysis. Oxford: Blackwell; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman P, Blumstein SE. Speech Physiology, Speech Perception, and Acoustic Phonetics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Local J, Kelly J. Projection and ‘silences’: Notes on phonetic and conversational structure. Human Studies. 1986;9:185–204. [Google Scholar]

- Local J, Walker G. Methodological imperatives for investigating the phonetic organisation and phonological structures of spontaneous speech. Phonetica. 2005;62:120–130. doi: 10.1159/000090093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Local J, Walker G. Stance and affect in conversation: On the interplay of sequential and phonetic resources. Text & Talk. 2008;28(7):723–747. [Google Scholar]

- Local J, Kelly J, Wells B. Towards a phonology of conversation: Turn-taking in Tyneside English. Journal of Linguistics. 1986;22(2):411–437. [Google Scholar]

- Local J, Wells B, Sebba M. Phonology for conversation: Phonetic aspects of turn delimitation in London Jamaican. Journal of Pragmatics. 1985;9:309–330. [Google Scholar]

- Mondada L. Multimodal resources for turn-taking: Pointing and the emergence of possible next speakers. Discourse Studies. 2007;9:194–225. [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen K. Establishing recipiency in pre-beginning position in the second language classroom. Discourse Processes. 2009;46:491–515. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond G. Prompting action: The stand-alone ‘so’ in ordinary conversation. Research on Language and Social Interaction. 2004;37:185–218. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JD. Getting down to business: Talk, gaze and bodily orientation during openings of doctor–patient consultations. Human Communication Research. 1998;25:97–123. [Google Scholar]

- Rossano F. When the eyes meet: Using gaze to mobilize response. Paper presented at International Conference on Conversation Analysis; Helsinki, Finland. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks H. Lectures on Conversation: Volume 1. Oxford: Blackwell; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks H, Schegloff EA, Jefferson G. A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language. 1974;50:696–735. [Google Scholar]

- Schegloff EA. Discourse as an interactional achievement: Some uses of ‘uh huh’ and other things that come between sentences. In: Tannen D, editor. Analyzing Discourse: Text and Talk. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press; 1982. pp. 71–93. [Google Scholar]

- Schegloff EA. Analyzing single episodes of interaction: An exercise in conversation analysis. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1987;50:101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Schegloff EA. Practices and actions: Boundary cases of other-initiated repair. Discourse Processes. 1997;23:499–545. [Google Scholar]

- Schegloff EA. Overlapping talk and the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language in Society. 2000;29:1–63. [Google Scholar]

- Schegloff EA, Jefferson G, Sacks H. The preference for self-correction in the organization of repair in conversation. Language. 1977;53:361–382. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffrin D. Discourse Markers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Selting M, Couper-Kuhlen E, editors. Studies in Interactional Linguistics, Grammar and Discourse. Amsterdam: John Benjamins; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sidnell J. Coordinating gesture, talk, and gaze in reenactments. Research on Language and Social Interaction. 2006;39(4):377–409. [Google Scholar]

- Stivers T, Enfield NJ, Brown P, et al. Universals and cultural variation in turn-taking in conversation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106(26):10587–10592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903616106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streeck J. Gestures as communication: Its coordination with gaze and speech. Communication Monographs. 1993;60:275–299. [Google Scholar]

- Streeck J. Forward-gesturing. Discourse Processes. 2009;46(2/3):161–179. [Google Scholar]

- Streeck J, Knapp ML. The interaction of visual and verbal features in human communication. In: Poyatos F, editor. Advances in Nonverbal Communication. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]