Abstract

Trp63, founding member of the Trp53 family, contributes to epithelial differentiation and is expressed in breast neoplasia. Trp63 features two distinct promoters yielding specific mRNAs encoding two major TRP63 isoforms, a transactivating transcription factor and a dominant negative isoform. Specific TRP63 isoforms are linked to cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, survival and epithelial mesenchymal transition. Although TRP63 overexpression in cultured cells is used to elucidate functions, little is known about Trp63 regulation in normal and cancerous mammary tissue. This study used ChIP-seq to interrogate transcription factor binding and histone modifications of the Trp63 locus in mammary tissue and RNA-seq and immunohistochemistry to gauge gene expression. H3K4me2 and H3K4me3 marks coincided only with the proximal promoter, supporting RNA-seq data showing the predominance of the dominant negative isoform. STAT5 bound specifically to the Trp63 proximal promoter and Trp63 mRNA levels were elevated upon deleting STAT5 from mammary tissue, suggesting its role as a negative regulator. The dominant negative TRP63 isoform was localized to nuclei of basal mammary epithelial cells throughout reproductive cycles, and retained in a majority of the triple negative cancers generated from loss of full-length BRCA1. Increased expression of dominant negative isoforms was correlated with developmental windows of increased progesterone receptor binding to the proximal Trp63 promoter and decreased expression during lactation was correlated with STAT5 binding to the same region. TRP63 is present in the majority of triple negative cancers resulting from loss of BRCA1 but diminished in less differentiated cancer subtypes and in cancer cells undergoing epithelial mesenchymal transition.

Keywords: mammary gland, gene regulation, molecular genetics, oncogene, neoplasia

Introduction

The Trp63 (transformation related protein 63) gene encodes two major isoforms, which are encoded by distinct mRNAs originating from two unique promoters (Yao and Chen. 2012). The transactivating (TA) isoform carries an N-terminal acidic domain that is lacking in the more abundant dominant negative (ΔN) isoform. Both TA and ΔN transcripts undergo splicing events, generating additional isoforms, which differ at their COOH-terminus (Murray-Zmijewski et al. 2006). TRP63 along with TRP73 is a member of the TRP53 family of transcription factors. It binds and transactivates TRP53 target genes (Yang et al. 1998). TRP63 is required for epithelial tissue development, including mammary anlagen as well as limb and craniofacial development (Mills et al. 1999, Yang et al. 1999). TATrp63 isoforms are expressed before ΔNTrp63 isoforms during mouse embryogenesis (Yao and Chen. 2012). High levels of TRP63 are found in basal cells of many tissues including mammary myoepithelial (Nylander et al. 2002, Sbisa et al. 2006, Truong et al. 2006, Yang and McKeon. 2000, Yallowitz et al. 2014, Forster et al. 2014). Stem cells of epithelial tissues such as colon, urinary bladder, prostate and mammary gland express TRP63 where it appears to be essential for maintaining the proliferative and regenerative abilities of the stem cell pool in stratified epithelial structures (Pignon et al. 2013, Pellegrini et al. 2001, Senoo et al. 2007) and glandular mammary tissue (Yallowitz et al. 2014). TRP63 is reported to regulate cell survival (Pietsch et al. 2008, Liefer et al. 2000, Senoo et al. 2004, Yallowitz et al. 2014), epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) (Lindsay et al. 2011, Oh et al. 2011, Tran et al. 2013) and paracrine signaling in epidermis (Barton et al. 2010) and mammary gland (Forster et al. 2014). Different TRP63 isoforms have the ability, at least in overexpressing tissue culture cells, to regulate gene transcription and exhibit distinct and similar functions (Dohn et al. 2001, Koster et al. 2007). ΔNTRP63 isoforms are reported to have longer half-life than TATRP63 isoforms (Yao and Chen. 2012).

For a large percentage of target genes, ΔNTRP63 appears to be the primary regulator of expression, at least in epidermis (Barton et al. 2010). Consistent with this concept, in triple negative breast cancer cell lines both TA and ΔN isoforms have the ability to positively regulate caspase-1 and their co-expression is positively correlated with survival (Celardo et al. 2013). TA isoforms can prevent ΔNTRP63 isoforms from up-regulating expression of oncogenic miR-155, expression of which is linked to tumor growth and migration (Mattiske et al. 2013). TATRP63 and its target Sharp1 inhibit metastasis of triple-negative breast cancer cells via degradation of hypoxia-induced factors (Piccolo et al. 2013, Montagner et al. 2012). Expression of ΔNTRP63α inhibits EMT triggered by the ΔNTRP63γ isoform in normal mammary epithelial cells (Lindsay et al. 2011) and constrains EMT in bladder cancer cells (Oh et al. 2011). However, it has also been reported that ΔNTRP63α promotes EMT in normal keratinocytes (Tran et al. 2013). While it is known that TRP63 can be expressed in many types of cancer, the percentage of cancers within each type expressing TRP63 varies (Yao and Chen. 2012). In mammary tissue TRP63 has been shown to contribute to maintenance of parity-identified mammary epithelial cells (PI-MECs) (Yallowitz et al. 2014) and TRP63 haploinsufficiency reduces pregnancy-promoted ErbB2 tumorigenesis in transgenic mice expressing activated ErbB2 (Yallowitz et al. 2014).

Post-pubertal development of mammary tissue is typified by hormonally regulated cycles of epithelial cell proliferation, function and apoptosis during estrus (Fata et al. 2001), pregnancy (Li et al. 1997, Schorr et al. 1999), lactation and involution. During pregnancy the prolonged proliferative phase triggered by estrogen and progesterone signaling is followed by relative quiescence with lactation, and apoptosis during involution correlated with phosphorylation and activation of Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3). TRP63 in mammary myoepithelial cells is required for lobuloalveolar development during pregnancy (Forster et al. 2014) through controlling Nrg (Neuregulin) 1 and 2 expression (Forster et al. 2014, Yallowitz et al. 2014). NRG1 is a paracrine factor expressed in mammary myoepithelial cells required for normal ERBB4 and STAT5 activation in luminal mammary epithelium (Forster et al. 2014). STAT5 activation in mammary luminal progenitor cells is required for normal lobuloalveolar development (Liu et al. 1997, Cui et al. 2004, Yamaji et al. 2009). TRP63 also contributes to regulating involution. Germline loss of one Trp63 allele is sufficient to increase rates of apoptosis in during the first phase of involution, pointing to a role for TRP63 in promoting mammary epithelial cell survival (Yallowitz et al. 2014). In contrast apoptosis and involution proceed normally when both Trp53 alleles are absent from the germline (Li et al. 1996). STAT3 has been reported to activate ΔNTRP63alpha in Hep3B cells (Chu et al. 2008).

The presence of TRP63 is a proposed biomarker for basal cancer (Shekhar et al. 2013, Thike et al. 2010a) but not all investigations concur (Thike et al. 2013, Buckley et al. 2011). TRP63, KRT5 and smooth muscle actin (ACTA2) are expressed coordinately in normal basal mammary myoepithelial cells but are not invariably synchronously expressed in human breast cancers (Jumppanen et al. 2007, Laakso et al. 2005). Two different basal-like (BL) cancer subtypes are recognized, with BL2 but not BL1 demonstrating TRP63 expression with a poorer response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy as compared to BL1 (Lehmann et al. 2011, Masuda et al. 2013). In one study higher TRP63 expression levels were positively correlated with brain metastasis (Shao et al. 2011). Positive staining for TRP63 can be used to differentiate intraductal papilloma from ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) (Furuya et al. 2012, Moriya et al. 2009). TRP63 is required for collective invasion of breast cancer organoids in 3D culture even if the cells used for culturing were acquired from primary tumors characterized as luminal rather than myoepithelial (Cheung et al. 2013).

Breast Cancer Susceptibility gene1 (BRCA1) is reported to increase transcription of the ΔNTrp63 isoforms in tissue culture cells (Buckley et al. 2011, Buckley and Mullan. 2012) while in vivo the presence of Trp63 expression is correlated with decreased expression of BRCA1 in basal type breast cancers (Ribeiro-Silva et al. 2005). BRCA1 and ΔNTRP63 also co-regulate expression of Notch signaling in mammary basal cells and loss of Notch would result in increased expression of stem/progenitor pool, loss of markers for terminal differentiation and simultaneous increase in basal markers (Buckley and Mullan. 2012). Women, who carry BRCA1 mutations demonstrate an increase in the percentage of luminal progenitor cells, which are thought to represent precursor cells for basal-like triple negative breast cancers (Lim et al. 2009). Triple negative breast cancers are over-represented in women, who carry BRCA1 mutations as compared to women who develop breast cancer without BRCA1 mutation (Ribeiro-Silva et al. 2005, Liu et al. 2008). This predilection is modeled in genetically engineered mice with a mammary epithelial cell specific deletion of full-length Brca1 (Herschkowitz et al. 2007) allowing us to explore the impact of loss of full-length Brca1 on p63 expression levels.

This study now addressed the critical void in our understanding of in vivo regulation of Trp63 in mammary gland development and cancer. Specific objectives were to assess the impact of BRCA1 and understand the relationship with cancer cell differentiation and EMT.

Materials and Methods

Mouse Models

Female C57Bl/6 parental inbred and litter-mate control wild-type (WT), Brca1floxed exon 11 (f11)/f11/Mouse Mammary Tumor Virus (MMTV)-Cre/Trp53+/+, Brca1f11/f11/MMTV-Cre/Trp53+/−, Brca1f11/WT/MMTV-Cre/Trp53+/−, and Brca1WT/WT/MMTV-Cre/Trp53+/−/tet-op-CYP19A1/MMTV-rtTA mice were identified by PCR (Jones et al. 2005, Transnetyx, Cordova, USA), maintained in barrier zones in sterilized ventilated cages with corncob bedding and ad libitum access to water/chow under 12 hour dark/light cycles at Georgetown University (1–4 mice/cage) or NIH (1 mouse/cage), euthanized by CO2 narcosis, and tissues removed at necropsy under guidelines approved by GUACUC/NIHIACUC. Mammary glands from mice aged 2.5, 6, 8, 10, 16 and 24 weeks were isolated from nulliparous, pregnant (P) days 6,17 calculated from day of vaginal plug first appearance, lactation (L) days 1,10, involution (In) days 1,3,7) (n=6 nulliparous (n=3 qRTPCR/IHC; n=3 one mouse each estrus, proestrus, diestrus); n=4 P,L,In). Estrous cycle stages were identified by vaginal cytology. Mammary cancers were isolated from 10- to 12-month-old nulliparous Brca1f11/f11/MMT-Cre/Trp53+/−, Brca1f11/WT/MMTV-Cre/Trp53+/−, Brca1WT/WT/MMTV-Cre/Trp53+/−/tet-op-CYP19A1/MMTV-rtTA mice (n=12). Dissected abdominal mammary glands and minimum of one third of tissue/cancer isolated from surrounding normal tissue were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and a second gland/third fixed in 10% formalin and paraffin embedded.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Five μm sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or used for immunohistochemistry (IHC): TRP63, MS-1081-P, 1:200 (Neomarkers, Fremont, USA); TATRP63, sc-8608, 1:40; ΔNTRP63, sc-8609, 1:40; ESR1, sc-542; 1:750; PGR, sc-538; 1:750; Her2/neu, sc-284; 1:400 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, USA), ss DNA, ALX-804-192, 1:10 (Alexis Biochemicals, Farmingdale, USA); KRT5, PRB-160P, 1:1000 (Covance Lab, USA), ACTA2, 1184-1, 1:500 (Epitomics, Burlingame, CA). Cancers were classified as triple negative either by gene expression array analyses (Herschkowitz et al. 2007) and/or absence of ESR1, PGR and HER≤2+ on IHC. IHC specificity was tested by omission of the primary antibody. Digital images were generated using a Nikon Eclipse E800 Microscope using Nikon DMX1200 software (Nikon Instruments, Inc., Melville, USA).

Primary culture

Primary mammary epithelial cancer cells were isolated (EpiCult®-B (Mouse), STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, CA), divided and cultured either to maintain expression of epithelial differentiation markers (E) as conditionally reprogrammed cells (Liu et al. 2012) or under conditions promoting expression of genes mediating EMT (EpiCult®-B), removed, placed into standard Gibco Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, and 1% Pen/Strep (Life Technologies, Grand Island, USA) and cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 until 85% confluency (48–72 hrs), washed x3 with 1xGibco phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (Life Technologies), collected by scraping into 1.5 ml eppendorf tubes, washed with 1xPBS, sedimented by centrifugation at 1000rpm for 5 minutes following 1xPBS washing x3, and frozen in liquid nitrogen.

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, qRT-PCR, RT-PCR, RNA-seq, ChIP-seq and statistical analyses

For qRT-PCR RNA was extracted using Invitrogen PureLink Micro-to-Midi RNA Extraction Kit# 12183-018 (Carlsbad, CA) and Qiagen shredder kit# 79654 (Germantown, USA), integrity confirmed by presence of 18S and 28S bands after agarose gel electrophoresis, first strand cDNA synthesized, and expression levels of different p63 isoforms determined using Mm00495788_m1 for total Trp63 (inventoried assay) and custom designed assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA): SApSh3T-EDS for TATrp63 (Forward (F):CCCAGAGGTCTTCCAGCATATCT, Reverse (R):TCAACTCGATGGGCTGTACTG); SApSh3D-SpC for ΔNTrp63 (F:CCTGGAAAACAATGCCCAGACT, R:AGGAGCCCCAGGTTCGT); SApSh3A-ESCR for Trp63α (F: GGGCTGACCACCATCTATCA, R: GTCGGAACTGTTCAGGGATCTT); SApSh3G-EDDp for Trp63γ (F:CAGCACCAGCACCTACTTCA, R:GCTCCACAAGCTCATTCCTGAA) with expression levels were normalized to 18s (Hs99999901_s1). Means and standard errors were analyzed using Mann-Whitney (Graphpad Software, San Diego, USA). p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Trp63, TATrp63, ΔNTrp63, Trp63alpha, beta and gamma RT-PCR was performed using published primers and conditions (Kurita et al. 2005) with Actb as control. For RNAseq, RNA was isolated from frozen tissue or cell pellets (Trizol, Invitrogen, Grand Island, USA), purified (RNeasy Plus Mini Kit, Qiagen, Valencia, CA), analyzed (Nanodrop, ThermoScientific, Wilmington, USA; Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100, Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, USA), converted to cDNA (SuperScript II, Invitrogen), sequencing libraries prepared (TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Kit, Illumina, San Diego, USA), analyzed (Nanodrop, Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100) and paired-end sequencing performed (HiSeq 2000, Illumina). Read quality was determined (FastQC, http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/project/fastqc), contaminated adaptor portions trimmed (Trim Galore, http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/project/trim_galore), reads aligned to mouse reference genome mm9 assembly, TopHat, (Kim et al. 2013), abundance of transcripts (FPKM, Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads) estimated, mapped reads analyzed using Cuffdiff (Trapnell et al. 2010) and visualized (Integrative Genomics Viewer) (Robinson et al. 2011). GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) obtained Chip-seq (STAT5 and H3K4me3 (GSE40930 and GSE31578); PGR (GSE42887); H3K4me2 (GSE25105), and RNA-seq (GSE37646), data. ChIPseq data was reanalyzed using HOMER (http://homer.salk.edu/homer/) (Heinz et al. 2010, Kang et al. 2014a).

Results

Histone modifications and transcription factor binding at the Trp63 locus

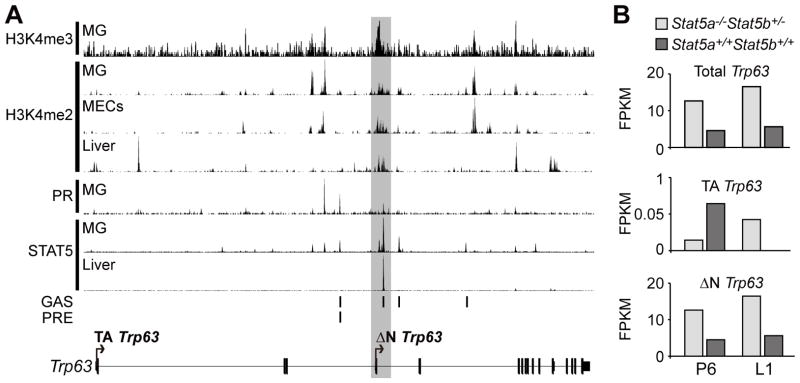

Regulatory features of the Trp63 gene in mouse mammary tissue were dissected by scanning the locus for pertinent histone modifications and binding of transcription factors STAT5 and PGR, known to control gene expression in mammary epithelium, through mining ChIP-seq and RNA-seq data from WT mammary gland (Yamaji et al. 2013, Zhang et al. 2012, Rijnkels et al. 2013, Kang et al. 2014) (Figure 1). H3K4me3 marks are indicative of active or poised promoters and H3K4me2 marks have been associated with enhancers. Definitive H3K4me3 and H3K4me2 marks were observed only over the proximal promoter that yields ΔNTrp63 transcripts (Figure 1A). H3K4me2 marks coincided with STAT5 binding at the proximal but not distal promoter. Binding of STAT5 at the same site in liver tissue supports the importance of this site. To explore a functional role for STAT5, RNA-seq was employed to analyze Trp63 levels in in the presence of different numbers of Stat5a/b alleles. In WT mammary tissue, carrying intact Stat5a and Stat5b alleles, Trp63 expression amounted to 5 FPKM at both P6 and L1 (Figure 1B). In contrast, Trp63 expression in the presence of only one Stat5b allele, which leads to an approximately 90% reduction of STAT5a/b, was above 10 FPKM at both P6 and L1. Levels of ΔNTrp63 isoforms were much higher than those of TATrp63 isoforms as predicted by the ChIP-seq. This genetic experiment indicated that STAT5 is a negative regulator of Trp63. PGR binding at the proximal, but not distal, promoter coincided with H3K4me2 marks during lactation (Figure 1A), however, in primary mammary epithelial cells from nulliparous mice weak H3K4me2 marks coincided with PGR binding to the distal promoter (data not shown). Both STAT5 and PGR are expressed at high levels in luminal mammary epithelial cells while ΔNTRP63 is localized to basal myoepithelial cells (Figure 2). This raises the possibility of STAT5 acting as negative regulator of ΔNTRP63 in luminal cells.

Figure 1. Histone modification and transcription factor binding to the Trp63 locus.

(A) Available STAT5, PGR, H3K4me2 and H3K4me3 ChIP-seq data of mammary gland and liver were reanalyzed to unveil usage of proximal and distal Trp63 promoters. The seven tracks illustrated are (top to bottom): H3K4me3: MG,L1: H3K4me2: MG,L8; H3K4me2: MECs, nulliparous-diestrus; H3K4me2: Liver, L8; PGR: MG, ovariectomized nulliparous treated E 24 hrs then E+Pr 6 hrs; STAT5a: MG,L1; STAT5b: Liver, nulliparous. (B) Bar graphs illustrating relative FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped) reads of Trp63, TATrp63 and ΔNTrp63 in mammary glands from genetically engineered STAT5 deficient (STAT5a−/−STAT5b+/−) (light grey) and WT (STAT5a+/+STAT5b+/+) (dark grey) mice at P6 and L1 as estimated by RNA-seq. Signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT); Progesterone Receptor (PGR); Mammary gland (MG); Mammary epithelial cells (MECs); Gamma interferon-activated sequence (GAS); Progesterone receptor binding element (PRE); Lactation day 1 (L1); Lactation day 8 (L8); Pregnancy day 6 (P6); E (17β-Estradiol,100ng); Pr (Progesterone,2.5ug).

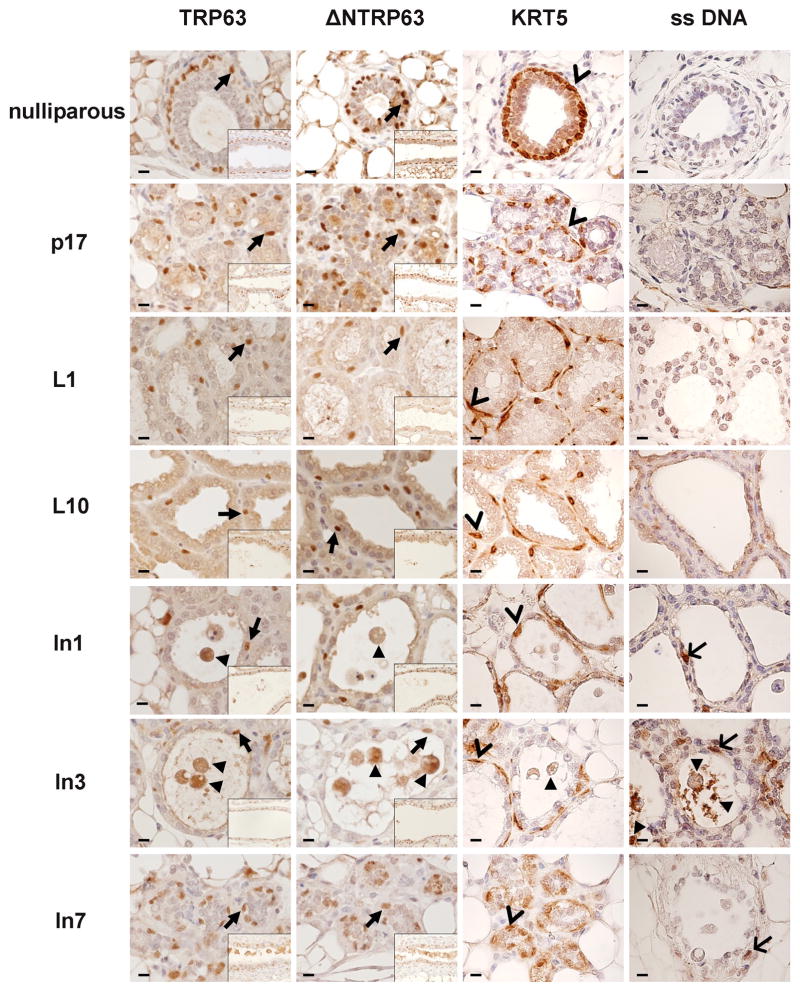

Figure 2. Immunohistochemical staining of distinct biological phases of post-pubertal mammary gland development and involution.

Representative images illustrating expression patterns of total TRP63, ΔNTRP63, KRT5 and ss (single-stranded) DNA in mammary gland from nulliparous, P17 (Pregnancy day 17), L1 (Lactation day 1), L10 (Lactation day 10), In1 (Involution day 1), In3 (Involution day 3) and In7 (Involution day 7). Images shown in large panels are small ducts (nulliparous, In7) and alveoli (P17, L1, L10, In1, In3). Images shown in insets are large ducts. TRP63, ΔNTRP63: Arrows point to representative cells with nuclear-localized TRP63 and ΔNTRP63 expression. Closed arrowheads point to representative cells shed into the lumen demonstrating TRP63 and ΔNTRP63 expression. KRT5: Open arrowheads point to representative cells with KRT5 expression. Closed arrowhead points to representative cell shed into the lumen demonstrating KRT5 expression. ss DNA: Arrows point to representative cells with a myoepithelial cell localization with reactivity for ss DNA. Closed arrowheads point to representative cells shed into the lumen with reactivity for ss DNA. Large panels taken at 60x magnification, insets at 20x magnification. Scale bar = 10 μm

TRP63 and ΔNTRP63 were localized to basal mammary epithelial cell nuclei throughout reproductive development

IHC for both TRP63 and ΔNTRP63 was performed in mammary tissue taken from WT mice that were nulliparous, pregnant, lactating or undergoing involution to determine if tissue or cellular localization changes during reproduction. KRT5 IHC was used as an independent marker for basal myoepithelial cells (Bankfalvi et al. 2004) and single stranded (ss) DNA IHC was performed to identify apoptotic cells (Frankfurt. 2004). Basal myoepithelial cells were the most prominent cell type expressing TRP63 and ΔNTRP63 in all samples with nuclear-localization throughout the cycle (Figure 2). Both small (large panels) and large (insets) ducts and alveoli (large panels) were examined with localization of TRP63 and ΔNTRP63 to myoepithelial cells throughout. The relatively contiguous arrangement of basal myoepithelial cells expressing nuclear-localized TRP63 and ΔNTRP63 in mammary gland from nulliparous mice evolved to a more dispersed pattern in late pregnancy (p17) and lactation, returning to the pattern found in nulliparous mice by involution day 7 (In7). Myoepithelial cells appeared to undergo apoptosis during involution, defined by their location within tissue and the presence of TRP63, ΔNTRP63, and KRT5 staining in cells shed into the lumen. During the first three days of involution apoptotic mammary epithelial cells are shed into the alveolar lumen (Schorr and Furth. 2000). Experiments indicated that patterns of Trp63 and ΔNTrp63 expression measured in total mammary gland are primarily derived from basal myoepithelial cells at all stages of reproductive development.

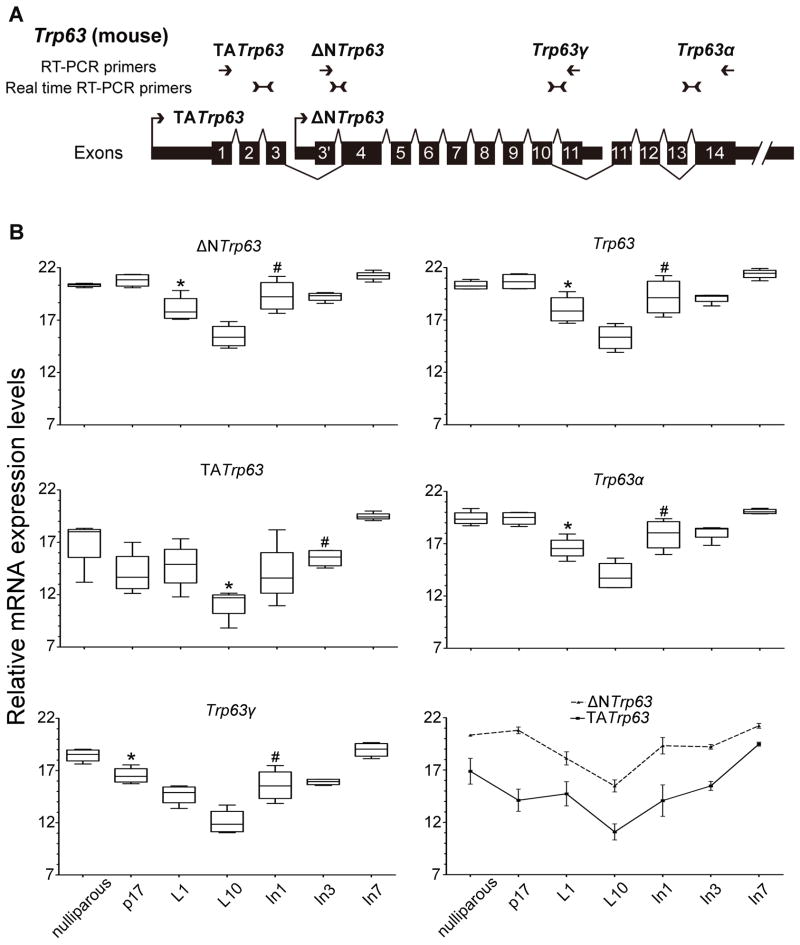

Trp63 expression was regulated during mammary gland reproductive development

Real-time RT-PCR was used to characterize expression levels of ΔNTrp63, total Trp63, TATrp63, Trp63alpha and Trp63gamma throughout the reproductive cycle (Figure 3). For comparison, locations of the real-time RT-PCR primers used for detection of different spliced forms during reproduction and the RT-PCR primers used to analyze expression in cancers are both indicated here along with exon structure, locations of the TATrp63 and ΔNTrp63 promoters and 3′ termini of the Trp63alpha and Trp63gamma splice forms (Figure 3A). It was not possible to design primers to specifically detect the Trp63beta spliced form. The higher sensitivity of the real-time RT-PCR compared to levels of sequencing used for the RNAseq (Figure 1B) enabled detection of both ΔNTrp63 and TATrp63 spliced forms (Figure 3B). Expression levels of both spliced forms were lowest at L10 but the kinetics of change differed. ΔNTrp63 expression was significantly lower at L1 (p<0.05, Mann Whitney compared to nulliparous, P17) while expression levels of TATrp63 dropped significantly only at L10 (p<0.05, Mann Whitney compared to nulliparous, P17, L1). Likely due to the overall higher expression levels of ΔNTrp63 compared to TATrp63, the significant drop in total Trp63 occurred at L1 (p<0.05, Mann Whitney compared to nulliparous, P17) as shown specifically for ΔNTrp63. Trp63alpha forms also dropped significantly at L1 (p<0.05, Mann Whitney compared to nulliparous, P17) while Trp63gamma forms showed a different pattern dropping significantly at P17 (p<0.05, Mann Whitney compared to nulliparous). Expression of ΔNTrp63, total Trp63, Trp63alpha, and Trp63gamma all rose significantly at Involution day 1 (In1) (all p<0.05, Mann Whitney compared to L1) but again the pattern of TATrp63 was unique, rising significantly only at In3. Line graphs indicated that expression of ΔNTrp63 was higher than TATrp63 throughout reproduction. When studying gene expression during mammary gland development, interpretations of significant expression drops during lactation must include consideration of the high levels of milk protein RNAs produced at that time that could produce a dilution effect. While highest levels of milk protein RNAs may be at L10, milk protein RNA expression is present at L1 and In1. It is possible lower levels of Trp63 expression were correlated with a change in cell type percentages in the mammary gland during lactation as milk-producing luminal cells were relatively more numerous than the more dispersed TRP63-expressing basal myoepithelial cells during lactation (Figure 2). Finally expression levels of phosphorylated STAT5, which appeared to act as a negative transcription factor (Figure 1), are highest during lactation (Liu et al. 1996). RNAseq data from WT nulliparous mice sampled during the estrous cycle demonstrated a doubling in Trp63 expression from 4 FPKM during estrus to 10 and 11 FPKM, respectively, during proestrus and diestrus, confirming regulated gene expression during a second type of reproductive cycle.

Figure 3. Changes in expression levels of Trp63 isoforms during normal mammary gland development.

(A) Structure of the Trp63 gene. Splicing (lines) and alternative promoters (arrows) are indicated. Locations of primers used for real time RT-PCR (B) and RT-PCR (Figure 5) are illustrated. (B) Box and whisker plots demonstrating changes in relative expression levels of ΔNTrp63, total Trp63, TATrp63, Trp63α (alpha), and Trp63γ (gamma) in mammary gland tissue from nulliparous, P17 (Pregnancy day 17), L1 (Lactation day 1), L10 (Lactation day 10), In1 (Involution day 1), In3 (Involution day 3) and In7 (Involution day 7) are shown along with line graphs comparing the relative expression levels of ΔNTrp63 and TATrp63 across these reproductive stages. Expression levels of Trp63 isoforms normalized to 18S. * indicates the earliest stage with a statistically significant drop in expression after the nulliparous stage (p<0.05, Mann Whitney). # indicates the earliest stage with a statistically significant increase in expression level after L10 (p<0.05, Mann Whitney).

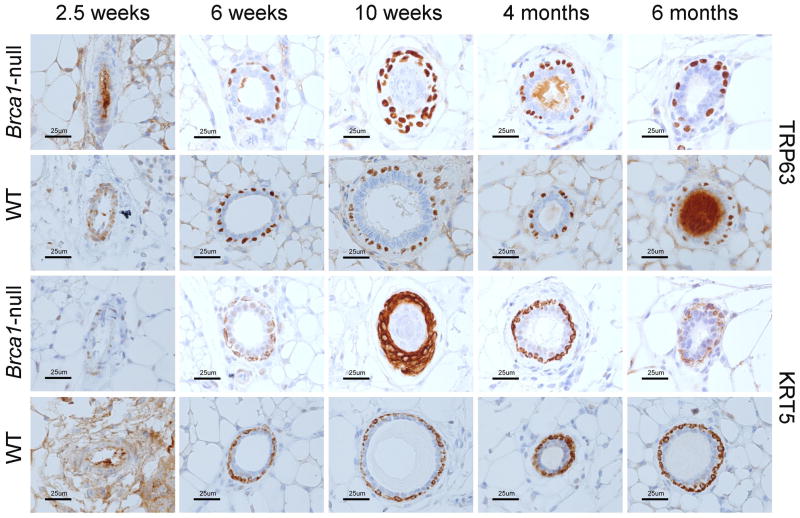

Disruption of full-length Brca1 expression in mammary epithelium did not alter TRP63 expression patterns during mammary gland development

Trp63 is required for establishment of mammary placodes (Yang et al. 1999). Brca1 is expressed in mammary epithelium before puberty (Marquis et al. 1995) and reported to positively regulate Trp63 expression (Buckley et al. 2011). To determine if loss of full-length BRCA1 disrupted the pattern of TRP63 expression or myoepithelial cell differentiation, expression patterns of TRP63 and KRT5 determined by IHC were compared in mammary tissues from WT mice and Brca1-null mice with loss of full-length Brca1 targeted to mammary epithelial cells (Brca1f11/f11/MMTV-Cre/Trp53+/+ mice) (Figure 4). Expression patterns of TRP63 in Brca1-null mice resembled those found in WT mice, clearly detectable as nuclear-localized in basally located cells by 6 weeks of age and continuing without change at 10 weeks, 4 and 6 months of age. Cytoplasmically located KRT5 showed a similar pattern, also expressed at significant levels in basal myoepithelial cells by 6 weeks of age. The data indicated that full-length BRCA1 does not play an essential role in regulating TRP63 expression during normal development in vivo.

Figure 4. Immunohistochemical staining of TRP63 and KRT5 in mammary tissue from mice with and without expression of full-length Brca1.

Representative images illustrating expression patterns of total TRP63 and KRT5 in mammary gland from nulliparous Brca1-null (Brca1f11/f11/MMTV-Cre/Trp53+/+) and WT mice at ages 2.5, 6 and 10 weeks and 4 and 6 months. Images taken at 40X magnification. Scale bar = 25 μm.

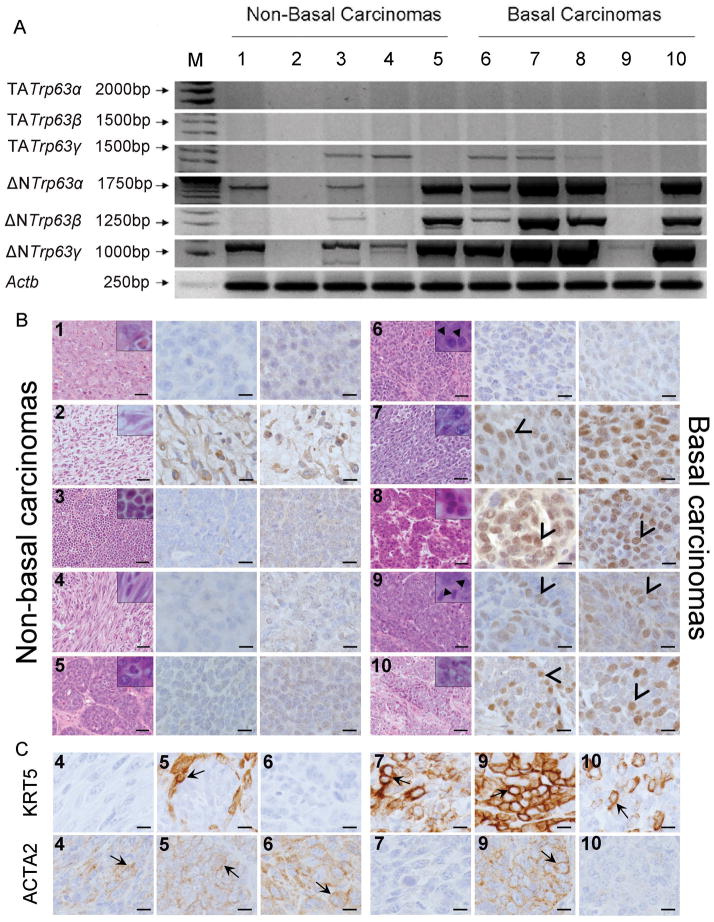

Expression levels of Trp63 in cancer were positively correlated with differentiation and intact Brca1

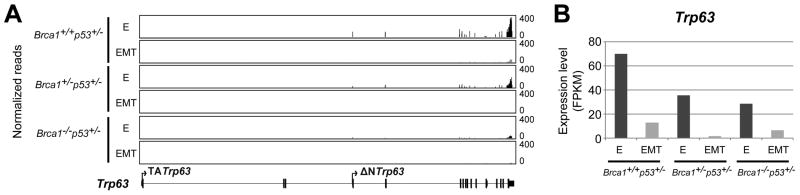

Triple negative mammary cancers develop in nulliparous mice with loss of full-length Brca1 targeted to mammary epithelial cells when one copy of germ-line Trp53 is disrupted (Jones et al. 2005). To assess Trp63 expression in mammary cancer cells in the absence of full-length BRCA1, a set of ten triple negative mammary carcinomas from Brca1f11/f11/MMTV-Cre/Trp53+/− mice were evaluated by RT-PCR and IHC (Figure 5). The set included non-basal and basal sub-types defined by cDNA array analyses and included eight adenocarcinomas (1,3,5–10) and two spindloid cancers (2,4) (Herschkowitz et al. 2007). In general ΔNTrp63 spliced forms were expressed at higher levels than TATrp63 spliced forms with highest levels found in more differentiated adenocarcinomas and predominantly nuclear localization of TRP63 and ΔNTRP63 (Figure 5). However, cytoplasmic location and additional Trp63 splice variants have also been reported in human cancers. Here the spindloid cancers showed a different pattern with undetectable RNA expression in one correlated with cytoplasmic staining (2) and relatively equal TA and ΔN Trp63gamma expression levels in the other (4). It is possible the cancer with cytoplasmic staining expressed an aberrant splice variant undetectable with the PCR primers used, or, the staining pattern is somehow artifactual, even when appropriately controlled. Brca1f11/f11/MMTV-Cre/Trp53+/− mice exhibit histologic tumor heterogeneity (Nakles et al. 2013), which is the simplest explanation for disconnects in RNA and protein expression levels seen (6,9), but altered regulation of TRP63 translation cannot be excluded. Cytokeratin 5 (KRT5) and smooth muscle actin (ACTA2) are basal cell markers (Sarrio et al. 2008, Abd El-Rehim et al. 2004, Thike et al. 2010b). Protein expression localized to cancer cells was evaluated using IHC (Figure 5C). Cancers classified as basal sub-type demonstrating TRP63 also showed expression for KRT5 but not invariably ACTA2. KRT5 expression in non-basal sub-type classified cancers with lower levels of TRP63 expression did not demonstrate KRT5 expression while one of the cancers with higher levels of ΔNTrp63 expression demonstrated KRT5 expression localized to cells in a ring-like pattern surrounding KRT5 negative cells. Some cancers that did not demonstrate KRT5 expression showed ACTAA2 expression. Primary mammary cancer cell lines derived from triple negative adenocarcinomas with two intact Brca1 alleles (Brca1+/+Trp53+/−) from Brca1WT/WT/MMTV-Cre/Trp53+/−/tet-op-CYP19A1/MMTV-rtTA mice, one intact Brca1 allele (Brca1+/− Trp53+/−) from Brca1f11/WT/MMTV-Cre/Trp53+/− mice, and two disrupted Brca1 alleles (Brca−/− Trp53+/−) from Brca1f11)/f11/MMTV-Cre/Trp53+/− mice were used to test if loss of full-length BRCA1 reduced Trp63 expression. Because Trp63 expression was higher in more differentiated cancers, the cell cultures were divided and cultured under two conditions: conditional reprogramming (Liu et al. 2012) that maintained epithelial cuboidal morphology (E) or EpiCult®-B (STEMCELL Technologies), permissive for EMT, and then harvested for analysis of gene expression by RNAseq. Significantly higher fold expression of mammary epithelial cell differentiation genes (Krt5, >2000-fold, Krt8, >2-fold, Krt1,4 >40-fold, Krt18, >2-fold) were documented in E cells compared to EMT cells while significantly higher fold expression of genes linked to EMT (Vim, >3-fold, Snail1, >8-fold, Twist1, >4-fold, Twist2, >7-fold) were found in EMT cells as compared to E cells (Cuffdiff, p<0.05). ΔNTrp63 were the dominant isoforms expressed across genotypes and culture conditions (Figure 6A). Disruption of Brca1 reduced Trp63 expression levels approximately 2-fold in both E and EMT cells (Figure 6B). Significantly, Trp63 expression levels were at least 4-fold higher in E cells of all genotypes (Figure 6B). These in vitro results paralleled the in vivo expression differences in the adenocarcinomas as compared to spindloid cancers and indicate that Trp63 is intrinsically down regulated during the process of EMT. Because loss of TRP63 has been linked to lower expression levels of Nrg1 (Forster et al. 2014, Yallowitz et al. 2014), expression levels were compared in the different cell lines. Expression levels were similar in E and EMT cells with one disrupted Brca1 allele (9 and 10 FPKM, respectively) but reduced >3-fold in EMT (4 FPKM) as compared to E (13 FPKM) cells with two disrupted Brca1 alleles (Cuffdiff, p<0.05).

Figure 5. Expression levels of different Trp63 isoforms and basal markers in mammary carcinomas developing in Brca1f11/f11/MMTV-Cre/Trp53+/− mice classified as either non-basal or basal.

(A) Relative expression levels of TATrp63α (alpha) (2043bp), TATrp63β (beta) (1664bp). TATrp63γ (gamma) (1407bp), ΔNTrp63α (alpha) (1761 bp), ΔNTrp63β (beta) (1382 bp), ΔNTrp63γ (gamma) (1125bp) and Actb (beta actin control) (244bp) in mammary carcinomas classified as non-basal (1–5) or basal (6–10) carcinomas by cDNA array analysis. Size of DNA ladder bands indicated in M (marker) lane. (B) Representative images of histology (H&E) and expression patterns of TRP63 and ΔNTRP63 in the same non-basal (1–5) and non-basal carcinomas analyzed in (A). (C) Representative images illustrating expression patterns of cytokeratin 5 (KRT5) and smooth muscle actin (ACTA2) from basal and non-basal carcinomas corresponding to lanes illustrated in panel A. H&E: large panels taken at 10X magnification, insets at 40X magnification. Scale bar = 50 μM. TRP63 and ΔNTRP63 panels taken 40X magnification. Scale bar = 10uM. Arrows indicate cells with representative immunohistochemical staining.

Figure 6. Expression of Trp63 isoforms in primary cell lines established from mouse mammary cancers with mutated Brca1 and Trp53 genes.

(A) Normalized read coverage across the Trp63 locus viewed through the integrative genomics viewer illustrates the relative expression levels of different exons of the Trp63 gene in primary cancer cells from mice with two intact Brca1 alleles (Brca1+/+Trp53+/−; Brca1WT/WT/MMTV-Cre/Trp53+/−/tet-op-CYP19A1/MMTV-rtTA mice), one intact Brca1 allele (Brca1+/−Trp53+/−; Brca1f11/WT/MMTV-Cre/Trp53+/− mice), and two disrupted Brca1 alleles (Brca−/−Trp53+/−; Brca1f11/f11/MMTV-Cre/Trp53+/− mice) cultured under conditions maintaining epithelial cell differentiation (E) or permissive for epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT). Note that exons demonstrating expression are all contained within ΔNTrp63 spliced forms. (B) Bar graphs illustrating relative FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped) Trp63 reads in the primary cancer cells with varying numbers of Brca1 alleles (A) cultured under conditions favoring epithelial cell differentiation (dark grey) or permissive for EMT (light grey).

Discussion

These studies, for the first time, provide insight into the chromatin landscape of the Trp63 locus in mouse mammary epithelium and provide genetic evidence that STAT5 is a negative regulator of this gene. Two classes of Trp63 isoforms had been reported, the long TA and short ΔN forms, which are derived from transcripts originating from the distal and proximal promoter, respectively. Based on ChIP-seq data, H3K4me2 and H3K4me3 activating chromatin marks are associated almost exclusively with the proximal promoter encoding the ΔNTrp63 spliced forms portending the significantly higher levels of ΔNTrp63 as compared to TATrp63 documented by RNAseq and RT-PCR across normal development and many of the cancers. ΔNTRP63 isoforms are shown to act as survival factors in normal and cancer cells of epithelial origin (Dugani et al. 2009, Lee et al. 2006, Mills et al. 1999, Rocco et al. 2006) compatible with a role for ΔNTRP63 in promoting cancer cell survival in cancers that express it. However, it is clear both in human breast cancers (Jumppanen et al. 2007, Laakso et al. 2005, Yao and Chen. 2012, Lehmann et al. 2011, Masuda et al. 2013, Shekhar et al. 2013, Thike et al. 2010b, Shao et al. 2011, Furuya et al. 2012, Moriya et al. 2009) and in mammary cancers that develop in Brca1f11/f11/MMTV-Cre/Trp53+/− mice (shown here, Nakles et al. 2013) that not all cancers express ΔNTRP63, indicating it is not absolutely required for cancer development.

Breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease and the Brca1f11/f11/MMTV-Cre/Trp53+/− mice develop a spectrum of triple negative breast cancer subtypes (Herschkowitz et al. 2007). Percentages of cancers showing nuclear-localized TRP63 reported here parallel previously reported results with approximately 50% of the cancers showing strong protein expression on IHC that is can be associated with concomitant KRT5 expression (Nakles et al. 2013) but is more variably accompanied by ACTA2 expression. This expression pattern is different from normal mature myoepithelial cells where all three of these markers are expressed synchronously but parallels results from human breast cancers where discordant expression is also found (Jumppanen et al. 2007, Laakso et al. 2005). Newly reported here is that the TRP63 detected in the cancers represents predominantly ΔNTRP63 isoform expression, confirming that the Brca1f11/f11/MMTV-Cre/Trp53+/− mice model the same pattern of TRP63 and ΔNTRP63 isoform expression described in human breast cancers (Su et al. 2013). This is the form most closely linked to mammary epithelial cell survival (Yallowitz et al. 2014), compatible with it mediating a role in cancer cell survival in this model. TRP63 also has been linked to maintenance of PI-MECs that in turn can have an impact on extent of pregnancy induced ErbB2 cancer development (Yallowitz et al. 2014). Here cancers were studied from nulliparous Brca1f11/f11/MMTV-Cre/Trp53+/− mice but it remains possible that TRP63 contributed to survival of cancer progenitor cells. The RNA studies provide novel information on expression of spliced forms of Trp63 in cancers, illustrate that they are not all identical in cancers (even developing within one genetically engineered mouse model), and establish the higher sensitivity of RNA for detection of gene activity. The spectrum of Trp63 expression in the different histologic cancer types developing in this model and the fact that cancers develop in nulliparous mice at high frequency suggest it would be a suitable preclinical model for the next set of investigations exploring the impact of Trp63 deletion on cancer pathophysiology and therapeutic outcome. Nrg1 is expressed in the primary cell lines developed from the cancers with one and two disrupted Brca1 alleles, providing linked in vivo and in vitro models for study of a possible role for Nrg1 in cancer development linked to loss of Brca1 function. A similar approach to develop cell lines from human breast cancers with mutated Brca1 alleles could be used to develop parallel human models (Liu et al. 2012). In both humans with mutated BRCA1 and mice with disrupted Brca1 alleles, accumulation of altered luminal progenitor cells is suggested to represent the population from which eventual cancer cells are derived (Lim et al. 2009, Smart et al. 2011).

STAT5 emerged as a negative regulator of Trp63 with genetic reduction of STAT5 levels resulting in increased Trp63 levels, a new finding. This negative regulation is consistent with the cellular localization of TRP63 to basal myoepithelial cells while STAT5 is primarily expressed in mammary luminal cells. This expands upon the interplay between TRP63 and activated STAT5 in mammary epithelium mediated by Nrg1 (Forster et al. 2014). TRP63 expression in mammary myoepithelial cells is required for activation of STAT5 in luminal cells but then STAT5 might act to repress Trp63 expression in these luminal cells. Similar to other studies, these results demonstrate TRP63 expression throughout all post-pubertal mammary gland development phases with ΔNTRP63 expression predominating (Yallowitz et al. 2014, Forster et al. 2014, Parsa et al. 1999) but extend them by documenting the expression patterns of all six different isoforms and showing that loss of Brca1 does not alter the basic pattern of nuclear localization in myoepithelial cells. PGR binding was also localized to ΔNTrp63 promoter region and interactions between STAT5 and PGR are reported. PGR also is expressed primarily in luminal mammary cells and may also be a negative regulator of ΔNTrp63, but this hypothesis needs to be directly tested in vivo. Experiments confirmed that BRCA1 is not essential for Trp63 expression but, in agreement with previous literature, showed increased Trp63 expression was associated with higher levels of full-length Brca1. Expression of TRP63 and ΔNTRP63 in basal myoepithelial cells first appears during normal mammary gland pubertal differentiation. This study showed that expression of Trp63 also is linked positively to differentiation in mammary cancers, both in vivo and in vitro. Significantly prevalence of TRP63 detection in cancers developing in Brca1f11/f11/MMTV-Cre/Trp53+/− mice is increased from 50% to 92% by treatment with efatutazone, a differentiating agent that is a ligand for Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) and demonstrated a lower prevalence of TRP63 expression in spindloid as compared to more differentiated cancer subtypes (Nakles et al. 2013). Here we showed that transcriptional regulatory mechanisms activated during EMT (Lindsay et al. 2011) include Trp63 down regulation.

It is challenging to assign RNA expression patterns to a specific cell type when working with whole tissue. Experiments here demonstrated that TRP63 and ΔNTRP63 remained nuclear-localized to basal myoepithelial cells across different stages of reproductive development. RNA expression levels can be measured by a variety of methods. Here we showed that the RT-PCR technology used was more sensitive than the conditions employed for RNA-seq (40 – 100 million reads) for detection of the TATrp63 isoforms. The lower levels of Trp63 expression found here during lactation as compared to nulliparous mice may be secondary to the lower percentage of myoepithelial as compared to luminal cells at that timepoint as expression of Trp63 in isolated luminal cells is very low and not significantly changed in isolated basal cells between those two timepoints (Forster et al. 2014). Expression does consistently appear to be increased with differentiation when changes in cell population types is not a factor as seen with the increase during the estrus cycle and with differentiation in cell culture as shown here.

In conclusion, this study contributes new information on the regulation of Trp63, implicating STAT5 and defining the role of BRCA1 and demonstrating the impact of differentiation. RNA isoform and protein expression patterns across normal mammary gland development, including reproductive cycles were explicitly defined, illustrating a predominant role for the ΔNTRP63 isoforms. A validated genetically engineered mouse model suitable for further studies investigating the impact of TRP63 in mammary disease and therapy was presented.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Research performed here supported in part by NIH NCI RO1 CA112176 (P.A.F.), DOD W81XWH-07-1-058 (P.A.F.), NIH IG20RR025828 (Rodent Barrier Facility Equipment), NIH NCI 5P30CA051008 (Histology and Tissue, Genomics and Epigenomics, and Animal Shared Resources). Part of this research was funded by the Intramural Research Program of NIDDK/NIH.

We thank M. Carla Cabrera and Sarah L. Millman for acquisition of immunohistochemistry images (Figure 4).

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

There are no conflicts of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Author contribution

S.A.^, K.K.^ (^ equal contributions), L.H. and P.A.F. designed, performed, and analyzed experiments, prepared figures, and wrote the manuscript. S.G., A.M.A. and X.L. cultured primary cells. S.A.D. prepared RNAseq libraries.

References

- Abd El-Rehim DM, Pinder SE, Paish CE, Bell J, Blamey RW, Robertson JF, Nicholson RI, Ellis IO. Expression of luminal and basal cytokeratins in human breast carcinoma. The Journal of Pathology. 2004;203:661–671. doi: 10.1002/path.1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankfalvi A, Ludwig A, De-Hesselle B, Buerger H, Buchwalow IB, Boecker W. Different proliferative activity of the glandular and myoepithelial lineages in benign proliferative and early malignant breast diseases. Modern Pathology. 2004;17:1051–1061. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton CE, Johnson KN, Mays DM, Boehnke K, Shyr Y, Boukamp P, Pietenpol JA. Novel p63 target genes involved in paracrine signaling and keratinocyte differentiation. Cell Death & Disease. 2010;1:e74. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2010.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley NE, Conlon SJ, Jirstrom K, Kay EW, Crawford NT, O’Grady A, Sheehan K, Mc Dade SS, Wang CW, McCance DJ, Johnston PG, Kennedy RD, Harkin DP, Mullan PB. The DeltaNp63 proteins are key allies of BRCA1 in the prevention of basal-like breast cancer. Cancer Research. 2011;71:1933–1944. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley NE, Mullan PB. BRCA1--conductor of the breast stem cell orchestra: the role of BRCA1 in mammary gland development and identification of cell of origin of BRCA1 mutant breast cancer. Stem Cell Reviews. 2012;8:982–993. doi: 10.1007/s12015-012-9354-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celardo I, Grespi F, Antonov A, Bernassola F, Garabadgiu AV, Melino G, Amelio I. Caspase-1 is a novel target of p63 in tumor suppression. Cell Death & Disease. 2013;4:e645. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung KJ, Gabrielson E, Werb Z, Ewald AJ. Collective Invasion in Breast Cancer Requires a Conserved Basal Epithelial Program. Cell. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu WK, Dai PM, Li HL, Chen JK. Transcriptional activity of the DeltaNp63 promoter is regulated by STAT3. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283:7328–7337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800183200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y, Riedlinger G, Miyoshi K, Tang W, Li C, Deng CX, Robinson GW, Hennighausen L. Inactivation of Stat5 in mouse mammary epithelium during pregnancy reveals distinct functions in cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2004;24:8037–8047. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.18.8037-8047.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohn M, Zhang S, Chen X. p63alpha and DeltaNp63alpha can induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis and differentially regulate p53 target genes. Oncogene. 2001;20:3193–3205. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugani CB, Paquin A, Fujitani M, Kaplan DR, Miller FD. p63 antagonizes p53 to promote the survival of embryonic neural precursor cells. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29:6710–6721. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5878-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fata JE, Chaudhary V, Khokha R. Cellular turnover in the mammary gland is correlated with systemic levels of progesterone and not 17beta-estradiol during the estrous cycle. Biology of Reproduction. 2001;65:680–688. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod65.3.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster N, Saladi SV, van Bragt M, Sfondouris ME, Jones FE, Li Z, Ellisen LW. Basal Cell Signaling by p63 Controls Luminal Progenitor Function and Lactation via NRG1. Developmental Cell. 2014;28:147–160. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankfurt OS. Immunoassay for single-stranded DNA in apoptotic cells. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2004;282:85–101. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-812-9:085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furey TS. ChIP-seq and beyond: new and improved methodologies to detect and characterize protein-DNA interactions. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2012;13:840–852. doi: 10.1038/nrg3306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuya C, Kawano H, Yamanouchi T, Oga A, Ueda J, Takahashi M. Combined evaluation of CK5/6, ER, p63, and MUC3 for distinguishing breast intraductal papilloma from ductal carcinoma in situ. Pathology International. 2012;62:381–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2012.02811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, Bertolino E, Lin YC, Laslo P, Cheng JX, Murre C, Singh H, Glass CK. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Molecular Cell. 2010;38:576–589. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herschkowitz JI, Simin K, Weigman VJ, Mikaelian I, Usary J, Hu Z, Rasmussen KE, Jones LP, Assefnia S, Chandrasekharan S, Backlund MG, Yin Y, Khramtsov AI, Bastein R, Quackenbush J, Glazer RI, Brown PH, Green JE, Kopelovich L, Furth PA, Palazzo JP, Olopade OI, Bernard PS, Churchill GA, Van Dyke T, Perou CM. Identification of conserved gene expression features between murine mammary carcinoma models and human breast tumors. Genome Biology. 2007;8:R76. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-5-r76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones LP, Li M, Halama ED, Ma Y, Lubet R, Grubbs CJ, Deng CX, Rosen EM, Furth PA. Promotion of mammary cancer development by tamoxifen in a mouse model of Brca1-mutation-related breast cancer. Oncogene. 2005;24:3554–3562. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jumppanen M, Gruvberger-Saal S, Kauraniemi P, Tanner M, Bendahl PO, Lundin M, Krogh M, Kataja P, Borg A, Ferno M, Isola J. Basal-like phenotype is not associated with patient survival in estrogen-receptor-negative breast cancers. Breast Cancer Research: BCR. 2007;9:R16. doi: 10.1186/bcr1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang K, Yamaji D, Yoo KH, Robinson GW, Hennighausen L. Mammary-Specific Gene Activation Is Defined by Progressive Recruitment of STAT5 during Pregnancy and the Establishment of H3K4me3 Marks. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2014;34:464–473. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00988-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, Salzberg SL. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biology. 2013;14:R36. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koster MI, Dai D, Marinari B, Sano Y, Costanzo A, Karin M, Roop DR. p63 induces key target genes required for epidermal morphogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:3255–3260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611376104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurita T, Cunha GR, Robboy SJ, Mills AA, Medina RT. Differential expression of p63 isoforms in female reproductive organs. Mechanisms of Development. 2005;122:1043–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laakso M, Loman N, Borg A, Isola J. Cytokeratin 5/14-positive breast cancer: true basal phenotype confined to BRCA1 tumors. Modern Pathology: An Official Journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 2005;18:1321–1328. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lain AR, Creighton CJ, Conneely OM. Research resource: progesterone receptor targetome underlying mammary gland branching morphogenesis. Molecular Endocrinology (Baltimore, Md) 2013;27:1743–1761. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HO, Lee JH, Choi E, Seol JY, Yun Y, Lee H. A dominant negative form of p63 inhibits apoptosis in a p53-independent manner. Biochemical & Biophysical Research Communications. 2006;344:166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann BD, Bauer JA, Chen X, Sanders ME, Chakravarthy AB, Shyr Y, Pietenpol JA. Identification of human triple-negative breast cancer subtypes and preclinical models for selection of targeted therapies. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2011;121:2750–2767. doi: 10.1172/JCI45014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Hu J, Heermeier K, Hennighausen L, Furth PA. Apoptosis and remodeling of mammary gland tissue during involution proceeds through p53-independent pathways. Cell Growth & Differentiation: The Molecular Biology Journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 1996;7:13–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Liu X, Robinson G, Bar-Peled U, Wagner KU, Young WS, Hennighausen L, Furth PA. Mammary-derived signals activate programmed cell death during the first stage of mammary gland involution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:3425–3430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liefer KM, Koster MI, Wang XJ, Yang A, McKeon F, Roop DR. Down-regulation of p63 is required for epidermal UV-B-induced apoptosis. Cancer Research. 2000;60:4016–4020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim E, Vaillant F, Wu D, Forrest NC, Pal B, Hart AH, Asselin-Labat ML, Gyorki DE, Ward T, Partanen A, Feleppa F, Huschtscha LI, Thorne HJ, kConFab, Fox SB, Yan M, French JD, Brown MA, Smyth GK, Visvader JE, Lindeman GJ. Aberrant luminal progenitors as the candidate target population for basal tumor development in BRCA1 mutation carriers. Nature Medicine. 2009;15:907–913. doi: 10.1038/nm.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay J, McDade SS, Pickard A, McCloskey KD, McCance DJ. Role of DeltaNp63gamma in epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286:3915–3924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.162511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Fan Q, Zhang Z, Li X, Yu H, Meng F. Basal-HER2 phenotype shows poorer survival than basal-like phenotype in hormone receptor-negative invasive breast cancers. Human Pathology. 2008;39:167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Ory V, Chapman S, Yuan H, Albanese C, Kallakury B, Timofeeva OA, Nealon C, Dakic A, Simic V, Haddad BR, Rhim JS, Dritschilo A, Riegel A, McBride A, Schlegel R. ROCK inhibitor and feeder cells induce the conditional reprogramming of epithelial cells. American Journal of Pathology. 2012;180:599–607. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Robinson GW, Hennighausen L. Activation of Stat5a and Stat5b by tyrosine phosphorylation is tightly linked to mammary gland differentiation. Molecular Endocrinology. 1996;10:1496–1506. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.12.8961260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Robinson GW, Wagner KU, Garrett L, Wynshaw-Boris A, Hennighausen L. Stat5a is mandatory for adult mammary gland development and lactogenesis. Genes & Development. 1997;11:179–186. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewe RP. Combinational usage of next generation sequencing and qPCR for the analysis of tumor samples. Methods (San Diego, Calif) 2013;59:126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquis ST, Rajan JV, Wynshaw-Boris A, Xu J, Yin GY, Abel KJ, Weber BL, Chodosh LA. The developmental pattern of Brca1 expression implies a role in differentiation of the breast and other tissues. Nature Genetics. 1995;11:17–26. doi: 10.1038/ng0995-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda H, Baggerly KA, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Meric-Bernstam F, Valero V, Lehmann BD, Pietenpol JA, Hortobagyi GN, Symmans WF, Ueno NT. Differential response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy among 7 triple-negative breast cancer molecular subtypes. Clinical Cancer Research: An Official Journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2013;19:5533–5540. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattiske S, Ho K, Noll JE, Neilsen PM, Callen DF, Suetani RJ. TAp63 regulates oncogenic miR-155 to mediate migration and tumour growth. Oncotarget. 2013;4:1894–1903. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills AA, Zheng B, Wang XJ, Vogel H, Roop DR, Bradley A. p63 is a p53 homologue required for limb and epidermal morphogenesis. Nature. 1999;398:708–713. doi: 10.1038/19531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montagner M, Enzo E, Forcato M, Zanconato F, Parenti A, Rampazzo E, Basso G, Leo G, Rosato A, Bicciato S, Cordenonsi M, Piccolo S. SHARP1 suppresses breast cancer metastasis by promoting degradation of hypoxia-inducible factors. Nature. 2012;487:380–384. doi: 10.1038/nature11207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriya T, Kozuka Y, Kanomata N, Tse GM, Tan PH. The role of immunohistochemistry in the differential diagnosis of breast lesions. Pathology. 2009;41:68–76. doi: 10.1080/00313020802563544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray-Zmijewski F, Lane DP, Bourdon JC. p53/p63/p73 isoforms: an orchestra of isoforms to harmonise cell differentiation and response to stress. Cell Death & Differentiation. 2006;13:962–972. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakles RE, Kallakury BV, Furth PA. The PPARgamma agonist efatutazone increases the spectrum of well-differentiated mammary cancer subtypes initiated by loss of full-length BRCA1 in association with TP53 haploinsufficiency. The American Journal of Pathology. 2013;182:1976–1985. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylander K, Vojtesek B, Nenutil R, Lindgren B, Roos G, Zhanxiang W, Sjostrom B, Dahlqvist A, Coates PJ. Differential expression of p63 isoforms in normal tissues and neoplastic cells. Journal of Pathology. 2002;198:417–427. doi: 10.1002/path.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh JE, Kim RH, Shin KH, Park NH, Kang MK. DeltaNp63 protein triggers epithelial-mesenchymal transition and confers stem cell properties in normal human keratinocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286:38757–38767. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.244939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsa R, Yang A, McKeon F, Green H. Association of p63 with proliferative potential in normal and neoplastic human keratinocytes. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 1999;113:1099–1105. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini G, Dellambra E, Golisano O, Martinelli E, Fantozzi I, Bondanza S, Ponzin D, McKeon F, De Luca M. p63 identifies keratinocyte stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:3156–3161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061032098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccolo S, Enzo E, Montagner M. p63, Sharp1, and HIFs: master regulators of metastasis in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Research. 2013;73:4978–4981. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietsch EC, Sykes SM, McMahon SB, Murphy ME. The p53 family and programmed cell death. Oncogene. 2008;27:6507–6521. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pignon JC, Grisanzio C, Geng Y, Song J, Shivdasani RA, Signoretti S. p63-expressing cells are the stem cells of developing prostate, bladder, and colorectal epithelia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:8105–8110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221216110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro-Silva A, Ramalho LN, Garcia SB, Brandao DF, Chahud F, Zucoloto S. p63 correlates with both BRCA1 and cytokeratin 5 in invasive breast carcinomas: further evidence for the pathogenesis of the basal phenotype of breast cancer. Histopathology. 2005;47:458–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijnkels M, Freeman-Zadrowski C, Hernandez J, Potluri V, Wang L, Li W, Lemay DG. Epigenetic modifications unlock the milk protein gene loci during mouse mammary gland development and differentiation. PloS One. 2013;8:e53270. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdottir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, Mesirov JP. Integrative genomics viewer. Nature Biotechnology. 2011;29:24–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocco JW, Leong CO, Kuperwasser N, DeYoung MP, Ellisen LW. p63 mediates survival in squamous cell carcinoma by suppression of p73-dependent apoptosis. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarrio D, Rodriguez-Pinilla SM, Hardisson D, Cano A, Moreno-Bueno G, Palacios J. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer relates to the basal-like phenotype. Cancer Research. 2008;68:989–997. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sbisa E, Mastropasqua G, Lefkimmiatis K, Caratozzolo MF, D’Erchia AM, Tullo A. Connecting p63 to cellular proliferation: the example of the adenosine deaminase target gene. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:205–212. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.2.2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schorr K, Furth PA. Induction of bcl-xL expression in mammary epithelial cells is glucocorticoid-dependent but not signal transducer and activator of transcription 5-dependent. Cancer Research. 2000;60:5950–5953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schorr K, Li M, Bar-Peled U, Lewis A, Heredia A, Lewis B, Knudson CM, Korsmeyer SJ, Jager R, Weiher H, Furth PA. Gain of Bcl-2 is more potent than bax loss in regulating mammary epithelial cell survival in vivo. Cancer Research. 1999;59:2541–2545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senoo M, Manis JP, Alt FW, McKeon F. p63 and p73 are not required for the development and p53-dependent apoptosis of T cells. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:85–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senoo M, Pinto F, Crum CP, McKeon F. p63 Is essential for the proliferative potential of stem cells in stratified epithelia. Cell. 2007;129:523–536. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao MM, Liu J, Vong JS, Niu Y, Germin B, Tang P, Chan AW, Lui PC, Law BK, Tan PH, Tse GM. A subset of breast cancer predisposes to brain metastasis. Medical Molecular Morphology. 2011;44:15–20. doi: 10.1007/s00795-010-0495-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shekhar MP, Kato I, Nangia-Makker P, Tait L. Comedo-DCIS is a precursor lesion for basal-like breast carcinoma: identification of a novel p63/Her2/neu expressing subgroup. Oncotarget. 2013;4:231–241. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart CE, Wronski A, French JD, Edwards SL, Asselin-Labat ML, Waddell N, Peters K, Brewster BL, Brooks K, Simpson K, Manning N, Lakhani SR, Grimmond S, Lindeman GJ, Visvader JE, Brown MA. Analysis of Brca1-deficient mouse mammary glands reveals reciprocal regulation of Brca1 and c-kit. Oncogene. 2011;30:1597–1607. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su X, Chakravarti D, Flores ER. p63 steps into the limelight: crucial roles in the suppression of tumorigenesis and metastasis. Nature Reviews. Cancer. 2013;13:136–143. doi: 10.1038/nrc3446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thike AA, Cheok PY, Jara-Lazaro AR, Tan B, Tan P, Tan PH. Triple-negative breast cancer: clinicopathological characteristics and relationship with basal-like breast cancer. Modern Pathology. 2010a;23:123–133. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thike AA, Iqbal J, Cheok PY, Chong AP, Tse GM, Tan B, Tan P, Wong NS, Tan PH. Triple negative breast cancer: outcome correlation with immunohistochemical detection of basal markers. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2010b;34:956–964. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181e02f45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thike AA, Iqbal J, Cheok PY, Tse GM, Tan PH. Ductal carcinoma in situ associated with triple negative invasive breast cancer: evidence for a precursor-product relationship. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2013;66:665–670. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2012-201428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran MN, Choi W, Wszolek MF, Navai N, Lee IL, Nitti G, Wen S, Flores ER, Siefker-Radtke A, Czerniak B, Dinney C, Barton M, McConkey DJ. The p63 protein isoform Np63 inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human bladder cancer cells: role of MIR-205. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2013;288:3275–3288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.408104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, Salzberg SL, Wold BJ, Pachter L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nature Biotechnology. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong AB, Kretz M, Ridky TW, Kimmel R, Khavari PA. p63 regulates proliferation and differentiation of developmentally mature keratinocytes. Genes & Development. 2006;20:3185–3197. doi: 10.1101/gad.1463206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yallowitz AR, Alexandrova EM, Talos F, Xu S, Marchenko ND, Moll UM. p63 is a prosurvival factor in the adult mammary gland during post-lactational involution, affecting PI-MECs and ErbB2 tumorigenesis. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2014;21:645–654. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaji D, Kang K, Robinson GW, Hennighausen L. Sequential activation of genetic programs in mouse mammary epithelium during pregnancy depends on STAT5A/B concentration. Nucleic Acids Research. 2013;41:1622–1636. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaji D, Na R, Feuermann Y, Pechhold S, Chen W, Robinson GW, Hennighausen L. Development of mammary luminal progenitor cells is controlled by the transcription factor STAT5A. Genes & Development. 2009;23:2382–2387. doi: 10.1101/gad.1840109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang A, Kaghad M, Wang Y, Gillett E, Fleming MD, Dotsch V, Andrews NC, Caput D, McKeon F. p63, a p53 homolog at 3q27-29, encodes multiple products with transactivating, death-inducing, and dominant-negative activities. Molecular Cell. 1998;2:305–316. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80275-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang A, McKeon F. P63 and P73: P53 mimics, menaces and more. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2000;1:199–207. doi: 10.1038/35043127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang A, Schweitzer R, Sun D, Kaghad M, Walker N, Bronson RT, Tabin C, Sharpe A, Caput D, Crum C, McKeon F. p63 is essential for regenerative proliferation in limb, craniofacial and epithelial development. Nature. 1999;398:714–718. doi: 10.1038/19539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao JY, Chen JK. Roles of p63 in epidermal development and tumorigenesis. Biomedical Journal. 2012;35:457–463. doi: 10.4103/2319-4170.104410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Laz EV, Waxman DJ. Dynamic, sex-differential STAT5 and BCL6 binding to sex-biased, growth hormone-regulated genes in adult mouse liver. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2012;32:880–896. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06312-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]