Abstract

Acute pancreatitis is the acute inflammation of pancreas and peripancreatic tissues, and distant organs are also affected. The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of Urtica dioica extract (UDE) treatment on cerulein induced acute pancreatitis in rats. Twenty-one Wistar Albino rats were divided into three groups: Control, Pancreatitis, and UDE treatment group. In the control group no procedures were performed. In the pancreatitis and treatment groups, pancreatitis was induced with intraperitoneal injection of cerulein, followed by intraperitoneal injection of 1 ml saline (pancreatitis group) and 1 ml 5.2% UDE (treatment group). Pancreatic tissues were examined histopathologically. Pro-inflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor-α), amylase and markers of apoptosis (M30, M65) were also measured in blood samples. Immunohistochemical staining was performed with Caspase-3 antibody. Histopathological findings in the UDE treatment group were less severe than in the pancreatitis group (5.7 vs 11.7, p = 0.010). TNF-α levels were not statistically different between treated and control groups (63.3 vs. 57.2, p = 0.141). UDE treatment was associated with less apoptosis [determined by M30, caspase-3 index (%)], (1.769 vs. 0.288, p = 0.056; 3% vs. 2.2%, p = 0.224; respectively). UDE treatment of pancreatitis merits further study.

Keywords: Pancreatitis, urtica dioica

Introduction

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is the acute inflammation of pancreas and peripancreatic tissues, and distant organs are also affected. Despite all the advances in the treatment, morbidity and mortality associated with AP are still high. The main etiologic factors in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis are the activation of trypsinogen, quinine and complement system, and the effects of free oxygen radicals and cytokines which are secreted by inflammatory cells [1]. During inflammation, the most important pro-inflammatory cytokine, TNF-α is secreted by inflammatory cells and TNF-α plays a key role in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis. Additionally, the increase in TNF-α level stimulates the number of apoptotic cells in the tissue. The number of apoptotic cells in mild edematous pancreatitis is higher than that in necrotizing pancreatitis which prevents necrotic progression [2-5]. The pathophysiological events in acute pancreatitis are not completely understood and to date many drugs and herbal remedies have been used to treat acute pancreatitis clinically or in experimental models. Unfortunately, very few of them have been found effective for the treatment of acute pancreatitis and also for the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis in the literature.

Urtica dioica is a member of Urticaceae (nettle) family which grows in temperate regions. When fresh urtica dioica contacts with skin, irritant effects are observed depending on serotonin, acetylcholine and histamine release. The composition of the nettle plant includes plant enzymes, phenylpropans, coumarins, formic acid, high amounts of chlorophyl, flavonoids, plant sterols, plant lignans, terpenoids, potassium salts, vitamin C, polysaccharides and lectin. Urtica dioica was reported to have anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and immunoregulatory functions [6,7]. In our study, we aimed to investigate the effects of urtica dioica extract on inflammation and apoptosis in experimental cerulein induced acute pancreatitis model in rats for the first time. We also investigated M30 levels and Caspase-3 index to determine apoptosis in this acute pancreatitis model.

Material and methods

This study was performed at Diskapi Yildirim Beyazit Educational and Research Hospital’s animal laboratory by using Wistar Albino rats with at least 3 months of age and whose weight ranged between 200-250 grams. Randomly chosen 5 rats in each cage were kept at room temperature with water and food ad libitum, one week before the study.

The night before the start of the experimental procedure, the rats were allowed water ad libitum but no food for 12 hours. The study included 21 rats which were randomly divided into 3 groups, containing 7 rats in each group. After anesthesia, pancreatitis was induced with cerulein (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA; 50 mcg/kg dose given 4 times at one hour intervals) applied intraperitoneally according to the method described by Mazzon et al [15]. At the end of the experiment in the 12th hour after the last cerulein application, the rats were sacrificed under anesthesia. Their abdomens were opened with a midline incision approximately 4 cm in length and pancreases were removed. 10% formalin was used to transfer the pancreatic tissue to the pathology laboratory for histopathological examination and immunohistochemical studies which measured the apoptotic index. Blood samples were obtained via truncal main vascular access before the animals were sacrificed. The sera were stored at -80°C for biochemical analysis including TNF-α, amylase, M30 and M65. This experimental study was approved by the ethical committee of our hospital.

Animals and grouping

First group was defined as the Sham Group (n = 7), second was the Pancreatitis Group (n = 7) in which 1 cc saline was injected intraperitoneally after 6 hours of the last dose of cerulein injection. The third group was the UDE Treatment Group (n = 7) in which 1 cc UDE was injected intraperitoneally at 6 hours after the last dose of cerulein.

Histopathological and immunohistochemical evaluation

Pancreatic tissue samples were embedded in paraffin after fixation within 10% formaldehyde solution and then 4-micrometer-thick sections were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The examination of tissues was performed by a single pathologist blinded to the groups. Pancreatitis was graded according to the modified criteria of Sporman’s [8]. Caspase-3 antibody (1:100; Thermo scientific, USA) was used for the immunohistochemical analysis. Cells were counted via nuclear staining with Caspase-3 through selecting 10 random areas at 400 X magnification under light microscopy.

Evaluation of biochemical parameters

ELISA kits (eBioscience, AUSTRIA) were used to measure TNF-α levels, and amylase, M30 and M65 levels were measured with (Cusabio biotech Co, LTD) ELISA kits. Normal ranges for TNF-α, amylase, M30 and M65 were 39.1-2500 pg/ml, 0-200 mIU/ml, 0.156-10 mIU/ml and 0.9-60 ng/ml; respectively.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 17.0 for Windows was used to analyze the data. The continuous variables were presented as mean, median and standard deviations; histograms and the “One-Sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test” were used to evaluate whether the continuous variables were distributed normally. The significance of the difference between the independent variables that were normally distributed was evaluated with the “Independent samples t-test”. The correlation between continuous variables was evaluated by “Spearman’s Correlation Test” and also Spearman’s Rho value is indicated as “r”. R values between 0-0.3 were accepted as low, 0.3 to 0.7 as moderate and 0.7 to 1 as high correlation. Statistical significance was defined as a p value of less than 0.05.

Results

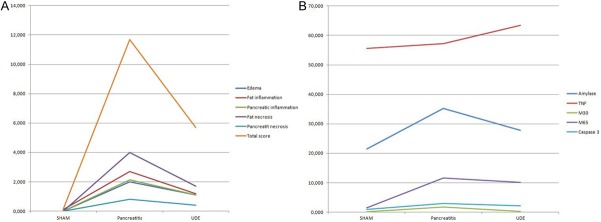

Histopathological scores of the groups and p values are shown in Table 1. We were unable to form a necrotizing pancreatitis model completely in the present study. Although parenchymal necrosis was not statistically significantly different between the sham group and the pancreatitis group (p = 0.147), the other histological scores were statistically significantly higher in the pancreatitis group compared with the sham group (p = <0.001). Except for pancreatic necrosis, all of the histopathological scores were better in the treatment group compared to the pancreatitis group and the difference was statistically significant (Figure 1A). Paranchymal necrosis was also less in the treatment group compared to the pancreatitis group, but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.552).

Table 1.

Mean values of pathologic scores in groups and comparison of groups

| Mean ± standard deviation | P values* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| SHAM | Pancreatitis | UDE | SHAM Pancreatitis | Pancreatitis UDE | |

| Edema | 0 | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | <0.001 | 0.007 |

| Fat inflammation | 0.1 ± 0.3 | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Pancreatic inflammation | 0 | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | <0.001 | 0.019 |

| Fat necrosis | 0 | 4.0 ± 2.2 | 1.7 ± 1.6 | <0.001 | 0.048 |

| Pancreatic necrosis | 0 | 0.8 ± 1.4 | 0.4 ± 1.1 | 0.147 | 0.552 |

| Total score | 0.1 ± 0.3 | 11.7 ± 4.4 | 5.7 ± 2.6 | <0.001 | 0.010 |

Independent samples t-test with 95% confidence interval.

Figure 1.

A: Pathologic scores in groups. B: Serum and tissue markers in groups.

Results of the biochemical tests of the groups are shown in Table 2 and Figure 1B. Amylase levels in the pancreatitis group were significantly higher than in the sham group (p = 0.002). Amylase levels in the treatment group were lower compared to the pancreatitis group, but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.073). No statistically significant difference in TNF-α levels were observed between the sham group and the pancreatitis group (p = 0.291), nor between the treatment group and the sham group (p = 0.141).

Table 2.

Mean values of parameters in groups and comparisons of groups

| Mean ± standard deviation | P values* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| SHAM | Pancreatitis | UDE | SHAM Pancreatitis | Pancreatitis UDE | |

| Amylase (mIU/ml) | 21.475 ± 4.385 | 35.184 ± 8.026 | 27.825 ± 5.824 | 0.002 | 0.073 |

| TNF-α (pg/ml) | 55.655 ± 3.166 | 57.233 ± 2.060 | 63.362 ± 10.094 | 0.291 | 0.141 |

| M30 (mIU/ml) | 0.160 ± 0.002 | 1.769 ± 1.839 | 0.288 ± 0.227 | 0.039 | 0.056 |

| M65 (ng/ml) | 1.551 ± 0.965 | 11.674 ± 2.065 | 10.068 ± 1.487 | <0.001 | 0.121 |

| Caspase-3 index (%) | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 3.0 ± 1.4 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 0.004 | 0.224 |

Independent samples t-test with 95% confidence interval.

Apoptosis markers were also compared. M30, M65 levels and apoptotic index (Caspase-3 index) were significantly higher in the pancreatitis group compared with the sham group (p = 0.039, p≤0.001, p = 0.004; respectively). M30, M65 levels and apoptotic index were lower in the treatment group compared to the pancreatitis group, but no statistically significant difference was found between the treatment group and pancreatitis group (p values; 0.056, 0.121, 0.224; respectively), (Table 2).

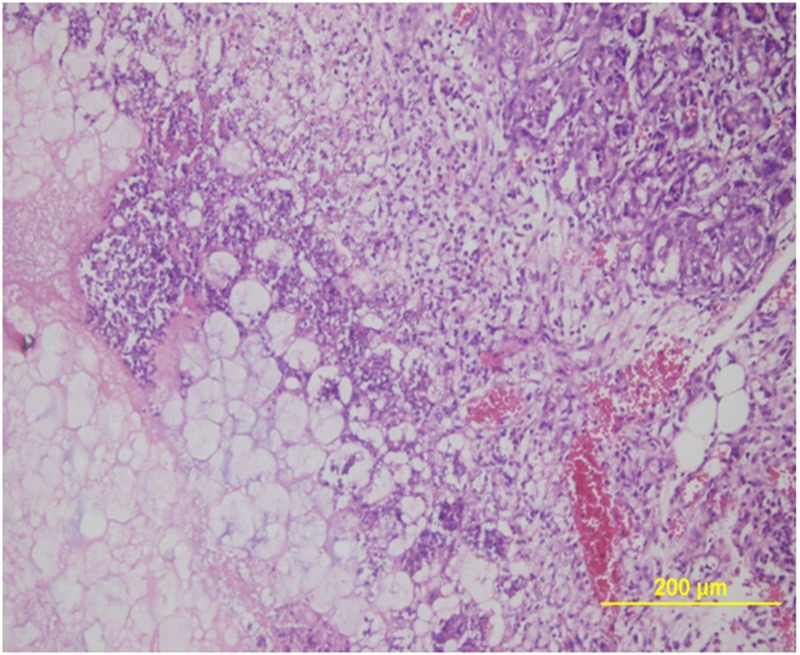

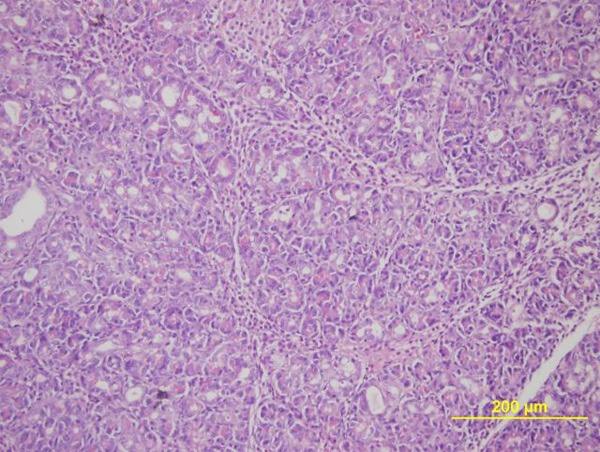

Correlation analyses of parameters among the groups are shown in Table 3. When we look at correlations of plasma markers, amylase has moderate correlations with M30, M65 and Caspase-3 index (r = 0.586, 0.619, 0.721; respectively). TNF-α has no correlations with M30, M65 or Caspase-3 index. M30 has high correlation with Caspase-3 index (p = 0.004, r = 0.596) and also has moderate correlations with M65 (p = 0.047, r = 0.439). M65 has moderate correlations with Caspase-3 index and M30 levels (r = 0.736, 0.439; respectively). Histopathological images with or without UDE treatment are shown in Figures 2 and 3.

Table 3.

Spearman correlation of plasma markers

| Amylase | TNF-α | M30 | M65 | Caspase-3 index | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amylase | r | 0.254 | 0.586** | 0.619** | 0.721** | |

| p | 0.266 | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.000 | ||

| TNF-α | r | 0.254 | -0.139 | 0.385 | 0.166 | |

| p | 0.266 | 0.548 | 0.085 | 0.473 | ||

| M30 | r | 0.586** | -0.139 | 0.439* | 0.596** | |

| p | 0.005 | 0.548 | 0.047 | 0.004 | ||

| M65 | r | 0.619** | 0.385 | 0.439* | 0.736** | |

| p | 0.003 | 0.085 | 0.047 | 0.000 | ||

| Caspase-3 index | r | 0.721** | 0.166 | 0.596** | 0.736** | |

| p | 0.000 | 0.473 | 0.004 | 0.000 | ||

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two tailed).

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (two tailed).

Figure 2.

Microscopic image of the severe pancreatitis characterized by pancreatic necrosis, an intense inflammatory cell infiltration and edema (H&E, X40).

Figure 3.

Microscopic image of the mild pancreatitis after treatment with urtica dioica extract (H&E, X40).

Discussion

The results of the present study demonstrate significantly less severe histopathological findings in cerulein induced experimental acute pancreatitis model with UDE treatment. Apoptosis was less with treatment, as shown by lower levels of M30, M65 and also by Caspase-3 index.

The pathophysiology of acute pancreatitis has not been clearly elucidated and many factors have been implicated. Recently, nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-kB) has been suggested to have a role in the pathogenesis of AP. NF-kB is a nuclear transcription factor which plays a role in the regulation and transcription of several genes associated with immunity, inflammation and apoptosis. When high levels of TNF-α induces NF-kB, apoptotic caspases reduces, which inhibits apoptosis [9-13]. TNF-α is the main inflammatory cytokine in acute pancreatitis and high levels of it inhibit apoptosis with the explained mechanism resulting in severe pancreatitis. Although TNF-α levels in our study were slightly higher in the AP models compared with controls, which is in accordance with the literature, we did not find a correlation with histopathological scores and TNF-α levels. We also did not find the regression in TNF-α levels with the histopathological improvement. This finding suggests that pathways other than that of TNF-α may be involved.

Apoptosis is one of the most important pathophysiological mechanisms in determining the severity of AP. The most important group of membrane receptors in apoptosis are the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) family. After interaction with TNF-α, acinar cell apoptosis occurs, this is considered to be a protective mechanism against progression to necrotizing pancreatitis [2,14]. Furthermore, in acute pancreatitis models in TNF-α receptor-deficient animals, apoptosis was not observed [3]. Also, it was reported that serum TNF-α levels in severe pancreatitis were higher than in mild pancreatitis [5] suggesting that TNF-α is closely related with the severity of acute pancreatitis. In addition, Zhang et al [4] reported that low concentrations of TNF-α induce apoptosis and decrease inflammation, and high concentrations of it cause acinar cell necrosis. In contrast to previous studies, in this experimental AP model, our results indicate that increased apoptosis is associated with an increased histopathological score. Additionally, we identified that the increase in apoptosis markers such as M30, Caspase-3 index are correlated with the severity of AP. Moreover, serum M30 levels in the present study were positively correlated with caspase-3 staining which indicates the increased apoptosis demonstrated in immunohistochemical examinations. Amylase levels were also correlated with the severity of AP (Table 4). We suggest that the reduction of apoptosis may be targeted in the course of AP and also serum levels of M30 may be used to determine apoptosis in acute pancreatitis in the follow-up, in daily practice.

Table 4.

Spearman correlation of plasma markers and histopathological scores

| Amylase | TNF-α | M30 | M65 | Caspase 3 index | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edema | r | 0.709** | 0.314 | 0.587** | 0.883** | 0.715** |

| p | 0.000 | 0.165 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Fat inflammation | r | 0.563** | 0.023 | 0.584** | 0.812** | 0.632** |

| p | 0.008 | 0.920 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.002 | |

| Pancreatic inflammation | r | 0.668** | 0.318 | 0.420 | 0.777** | 0.602** |

| p | 0.001 | 0.160 | 0.058 | 0.000 | 0.004 | |

| Fat necrosis | r | 0.309 | 0.197 | 0.480* | 0.673** | 0.503* |

| p | 0.173 | 0.392 | 0.028 | 0.001 | 0.020 | |

| Pancreatic necrosis | r | 0.053 | 0.079 | 0.191 | 0.327 | 0.274 |

| p | 0.820 | 0.734 | 0.408 | 0.148 | 0.229 | |

| Total score | r | 0.491* | 0.210 | 0.525* | 0.790** | 0.615** |

| p | 0.024 | 0.361 | 0.015 | 0.000 | 0.003 |

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two tailed).

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (two tailed).

In some countries, urtica dioica extract is used in the adjuvant treatment of rheumatic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis. Some studies showed that urtica dioica extract reduced the levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1 beta [6]. Another study showed the anti-inflammatory effects of urtica dioica extract through a reduction in TNF-α levels [7]. Before the present study, no data have been available regarding the use of urtica dioica extract in acute pancreatitis. Our study also suggests that UDE administration may provide improvement in acute pancreatitis.

In conclusion, our study showed that apoptosis is reduced and histopathological improvement is achieved with UDE treatment, in a cerulein induced acute pancreatitis model. Further experimental and clinical studies are needed for evaluating the effects of urtica dioica in acute pancreatitis.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the scientific research project fund of Diskapi Yildirim Beyazit Education and Research Hospital. The study was performed according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and it was approved by the local ethics review committee.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Skipworth JR, Pereira SP. Acute pancreatitis. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2008;14:172–178. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3282f6a3f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhatia M. Apoptosis versus necrosis in acute pancreatitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;286:G189–196. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00304.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gukovskaya AS, Gukovsky I, Zaninovic V, Song M, Sandoval D, Gukovsky S, Pandol SJ. Pancreatic acinar cells produce, release, and respond to tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Role in regulating cell death and pancreatitis. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:1853–1862. doi: 10.1172/JCI119714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang YH, Zhou L, Huang LM. Role of apoptosis and TNF in pathogenesis of rat acute pancreatitis. Guizhou Med. 2004;28:1081–1083. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen K, liang J, Tang B, Ye WT, Wang WM, Zhu B. Determination of serum TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-8 contents in acute pancreatitis patients. Shanghai J Immunol. 2000;20:169–171. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Konrad A, Mahler M, Arni S, Flogerzi B, Klingelhöfer S, Seibold F. Ameliorative effect of IDS 30, a stinging nettle leaf extract, on chronic colitis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2005;20:9–17. doi: 10.1007/s00384-004-0619-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Genc Z, Yarat A, Tunali-Akbay T, Sener G, Cetinel S, Pisiriciler R, Caliskan-Ak E, Altıntas A, Demirci B. The effect of stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) seed oil on experimental colitis in rats. J Med Food. 2011;14:1554–1561. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2011.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spormann H, Sokolowski A, Letko G. Effect of temporary ischemia upon development and histological patterns of acute pancreatitis in the rat. Pathol Res Pract. 1989;184:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(89)80143-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunn JA, Li C, Ha T, Kao RL, Browder W. Therapeutic modification of nuclear factor kappa B binding activity and tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene expression during acure biliary pancreatitis. Am Surg. 1997;63:1036–1043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gukovsky I, Gukovskaya AS, Blinman TA, Zaninovic V, Pandol SJ. Early NF-kappa B activation is associated with hormoneinduced pancreatitis. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:G1402–1414. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.275.6.G1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bai XW, Sun B. Severe acute pancreatitis and nuclear factor. J Harbin Med Univ. 2004;38:488–489. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Satoh A, Shimosegawa T, Fujita M. Inhibition of nuclear factor-kB activation improves the survival of rats with taurocholate pancreatitis. Gut. 1999;44:253–258. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.2.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weber CK, Adler G. From acinar cell damage to systemic inflammatory response: current concepts inpancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2001;1:356–362. doi: 10.1159/000055834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shang D, Yang PM, Xin Y, Chen HL, Liu Z. Role of pancreatic acinar cell apoptosis in course of rat with acute pancreatitis and expression of apoptosis controlling gene. J Hepatopancreatobil Surg. 2001;13:152–155. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazzon E, Genovese T, Di Paola R, Muia C, Crisafulli C, Malleo G, Esposito E, Meli R, Sessa E, Cuzzocrea S. Effects of 3-aminobenzamide, an inhibitor of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase, in a mouse model of acute pancreatitis induced by cerulein. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;549:149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]