Abstract

The aim of the present study was to assess the objectivity and accuracy of a new system to evaluate pregnancy prognosis in tubal factor infertility (TFI) patients. Retrospective study in 469 TFI patients were pre- and postoperatively scored using the new system as mild, moderate or severe TFI, based on tubal adhesions, patency, morphology and structure. Follow-up was assessed to determine pregnancy outcomes. Laparoscopic salpingoplasty and hydrotubation, hysteroscopic-laparoscopic salpingoplasty and hydrotubation, and laparoscopic hydrotubation all decreased TFI scores to a similar extent. The pre- and postoperative TFI classification was significantly associated with intrauterine pregnancy (mild: 43.6% vs. moderate: 34.0% vs. severe: 19.4%, P < 0.0001) and live births (mild: 35.9% and moderate: 31.5% vs. severe: 16.8%, P = 0.0002) rates. Multivariate analysis showed that the preoperative disease course (P = 0.02), preoperative TFI score (P < 0.0001), and postoperative TFI score (P = 0.0007) were independently associated with the rate of intrauterine pregnancy rate. Multivariate analysis also showed that the postoperative TFI score (P = 0.001), pelvic inflammatory disease (P = 0.03) and age (P = 0.03) were independently associated with the rate of live births. Conclusion: We devised a new classification system for TFI prognosis. Salpingoplasty improved these scores. Both pre- and postoperative TFI assessments using this new system are associated with pregnancy prognosis in TFI patients.

Keywords: Tubal factor infertility, salpingoplasty, follow-up, retrospective analysis, tubal classification system

Introduction

Tubal factor infertility (TFI) is one of the most common causes of female infertility, accounting for 30-35% of cases [1]. The use of tubal classification systems can help to better evaluate the effects of salpingoplasty and pregnancy outcomes. However, many systems exist for tubal scoring [2-10], the most popular ones being the pelvic adhesions classification in the revised American Fertility Society (AFS-r) [2], the Hulka tubal classification system [3], the Hull & Rutherford classification system [4], and falloposcopy [10].

However, these systems are known to have a number of limitations [11-14]. Indeed, AFS-r only evaluates pelvic adhesions, and the Hulka and the Hull & Rutherford systems are too general. Finally, falloposcopy is not widely used domestically, and it can only diagnose and treat the inner diseases of fallopian tubes, and cannot evaluate the conditions of the pelvic cavity.

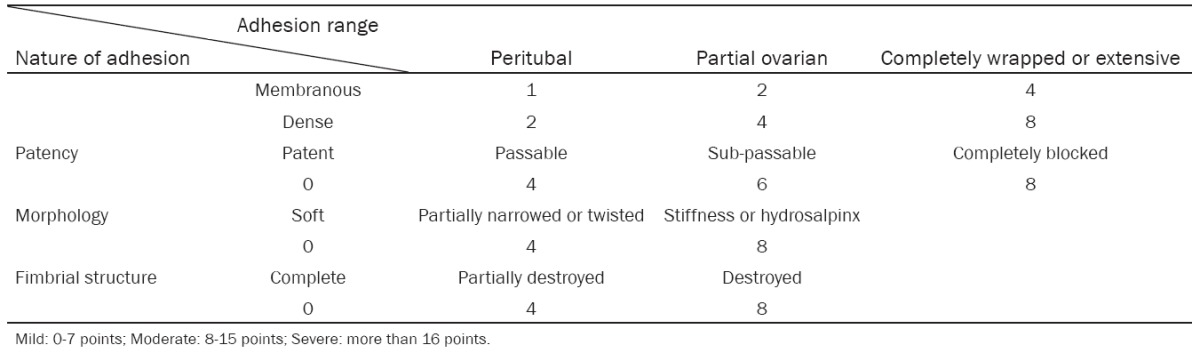

Nevertheless, there is an important need to be able to make a correct prognosis after tubal surgery in order to optimize the correct use of expensive resources [15-17]. Therefore, we devised a combined classification using the pelvic adhesions from the AFS-r, the observational items from the Hulka system, and the level descriptions from the Hull & Rutherford system, to which we added a new tubal classification system based on surgical records (Table 1). The aim of the present study was to assess the objectivity and accuracy of a new system to evaluate pregnancy prognosis in tubal factor infertility (TFI) patients. The ultimate aim was to assess the prognostic value of this new tubal classification using a system that is simple, logical and evidence-based.

Table 1.

Our new tubal classification system

|

Material and methods

Patients

This was a retrospective study performed in all TFI cases (n = 1290) from the Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital of Fudan University (Shanghai, China) who underwent salpingoplasty between 2003 and 2007 and who had available follow-up data (final n = 469).

Scoring

All 469 patients were stratified using our new score (Table 1), both pre- and post-operatively, based on available data from the medical charts, and according to Mild (0-7 points), Moderate (8-15 points) or Severe (> 16 points) TFI. Pregnancy outcomes (intrauterine pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, live birth and infertility rates) were compared across these scores.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Mann-Witney U tests, Wilcoxon rank sum tests, χ2 tests and binary logistic regression analysis, as appropriate. SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to perform all statistical analyses. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics of the 469 included patients according to TFI grading according to our new scoring system. Patients in the moderate TFI group were slightly younger. The number of past pregnancies was the same, but patients in the mild TFI group had a higher number of ectopic pregnancies (mild: 23.1% vs. moderate: 5.0% and severe: 4.3%, P < 0.0001) and a higher frequency of ovarian tumors (mild: 3.9% vs. moderate: 0% and severe: 1.3%, P = 0.03).

Table 2.

Patients’ baseline characteristics

| Disease course | Level 1 of the preoperative scoring | Level 2 of the preoperative scoring | Level 3 of the preoperative scoring | All | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 78 (16.6) | 159 (33.9) | 232 (49.5) | 469 | |

| Age | 30.00 ± 6.00 | 28.00 ± 6.00 | 30.00 ± 6.00 | 29.00 ± 5.00 | 0.0099 |

| Disease course (duration of infertility) | 3.00 ± 4.00 | 3.00 ± 2.00 | 3.00 ± 4.00 | 3.00 ± 4.00 | 0.0338 |

| Number of pregnancies | 1.00 ± 2.00 | 1.00 ± 2.00 | 1.00 ± 2.00 | 1.00 ± 2.00 | 0.5843 |

| History of ectopic pregnancy | |||||

| Yes | 18 (23.1) | 8 (5.0) | 10 (4.3) | 36 (7.7) | < .0001 |

| No | 60 (76.9) | 151 (95.0) | 222 (95.7) | 433 (92.3) | |

| History of operation | |||||

| Yes | 12 (15.4) | 14 (8.8) | 28 (12.1) | 54 (11.5) | 0.3069 |

| No | 66 (84.6) | 145 (91.2) | 204 (87.9) | 415 (88.5) | |

| Ovarian tumors | |||||

| With | 3 (3.9) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.3) | 6 (1.3) | 0.0337 |

| Without | 75 (96.1) | 159 (100.0) | 229 (98.7) | 463 (98.7) | |

| PID | |||||

| With | 8 (10.3) | 18 (11.3) | 30 (12.9) | 56 (11.9) | 0.7847 |

| Without | 70 (89.7) | 141 (88.7) | 202 (87.1) | 413 (88.1) | |

| Surgery | |||||

| Laparoscopic salpingoplasty + hydrotubation | 66 (84.6) | 134 (84.3) | 199 (85.8) | 399 (85.1) | 0.9123 |

| Hysteroscopic-laparoscopic salpingoplasty + hydrotubation | 12 (15.4) | 24 (15.1) | 31 (13.4) | 67 (14.3) | |

| Hydrotubation | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (0.9) | 3 (0.6) |

PID: pelvic inflammatory disease.

Impact of surgery on TFI grade

Table 3 shows the effects of the three types of surgery used in our center to correct TFI. Using laparoscopic salpingoplasty and hydrotubation, the score decreased from 15 ± 12 to 4 ± 5 (P < 0.0001). Using hysteroscopic-laparoscopic salpingoplasty and hydrotubation, the score decreased from 14 ± 10 to 4 ± 8 (P < 0.0001). Finally, using laparoscopic hydrotubation, the score decreased from 20 ± 10 to 5 ± 10 (P = 0.04).

Table 3.

Patients’ preoperative and postoperative scorings (median ± interquartile). Comparison of the three surgical methods in the new tubal classification system (mean)

| Preoperative | Postoperative | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laparoscopic salpingoplasty + hydrotubation | 15 ± 12 | 4 ± 5 | < 0.0001 |

| Hysteroscopic-laparoscopic salpingoplasty + hydrotubation | 14 ± 10 | 4 ± 8 | < 0.0001 |

| Laparotomic hydrotubation | 20 ± 10 | 5 ± 10 | 0.0424 |

Pregnancy outcomes

Table 4 shows the 2-year pregnancy outcomes of the patients according to their preoperative TFI score. More patients in the severe TFI group were still infertile 2 years after surgery (severe: 70.7% vs. mild: 46.2% and moderate: 49.1%, P < 0.0001). Significantly more intrauterine pregnancies were observed in the mild and moderate TFI groups (mild: 43.6% vs. moderate: 34.0% vs. severe: 19.4%, P < 0.0001). No difference in the rate of ectopic pregnancies was observed (P = 0.15). Significantly more live births were obtained in patients with mild and moderate TFI (mild: 35.9% and moderate: 31.5% vs. severe: 16.8%, P = 0.0002).

Table 4.

Pregnancy outcomes according to the preoperative TFI grading system

| Outcome | All | Mild | Moderate | Severe | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 469 | 78 (16.6) | 159 (33.9) | 232 (49.5) | |

| Infertility within 2 years | 278 (59.3) | 36 (46.2) | 78 (49.1) | 164 (70.7) | <0.0001 |

| Intrauterine pregnancy within 2 years | 133 (28.4) | 34 (43.6) | 54 (34.0) | 45 (19.4) | <0.0001 |

| Ectopic pregnancy within 2 years | 60 (12.8) | 9 (11.5) | 27 (17.0) | 24 (10.3) | 0.1454 |

| Live birth | 117 (24.9) | 28 (35.9) | 50 (31.5) | 39 (16.8) | 0.0002 |

Table 5 shows the same analysis, but according to postoperative TFI grade. More patients in the moderate and severe TFI groups were still infertile 2 years after surgery (moderate: 73.6% vs. severe: 100.0% vs. mild: 54.5%, P = 0.0004). Significantly more intrauterine pregnancies were observed in the mild and moderate TFI groups (mild: 32.4% vs. moderate: 16.0% vs. severe: 0%, P = 0.0002). No difference in the rate of ectopic pregnancies was observed (P = 0.46). Significantly more live births were obtained in patients with mild and moderate TFI (mild: 28.5% vs. moderate: 14.2% vs. severe: 0%, P = 0.005).

Table 5.

Pregnancy outcomes according to the postoperative TFI grading system

| Outcome | All | Mild | Moderate | Severe | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 469 | 358 (76.3) | 106 (22.6) | 5 (1.1) | |

| Infertility within 2 years | 278 (59.3) | 195 (54.5) | 78 (73.6) | 5 (100.0) | 0.0004 |

| Intrauterine pregnancy within 2 years | 133 (28.4) | 116 (32.4) | 17 (16.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0017 |

| Ectopic pregnancy within 2 years | 60 (12.8) | 49 (13.7) | 11 (10.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.4620 |

| Live birth | 117 (24.9) | 102 (28.5) | 15 (14.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0048 |

Factors affecting the rate of intrauterine pregnancy

Table 6 shows the univariate analysis of factors involved in the rate of intrauterine pregnancies. Preoperative disease course (HR = 0.89, 95% CI: 0.78-0.98, P = 0.02), preoperative TFI score (severe TFI: HR = 0.44, 95% CI: 0.28-0.68, P < 0.0001) and postoperative TFI score (moderate TFI: HR = 0.41, 95% CI: 0.25-0.69, P = 0.0007) had an impact on the rate of intrauterine pregnancies.

Table 6.

Univariate analyses of factors affecting the rate of intrauterine pregnancies

| Factors | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.96 (0.92-1.00) | 0.0506 | |

| Preoperative disease course | 0.87 (0.78-0.98) | 0.0167 | |

| Number of pregnancies | 1.02 (0.87-1.19) | 0.8075 | |

| Ectopic pregnancy | Yes vs. No | 0.61 (0.30-1.27) | 0.1869 |

| Other operations | Yes vs. No | 0.95 (0.55-1.66) | 0.8679 |

| Ovarian tumors | Yes vs. No | 1.43 (0.35-5.79) | 0.6155 |

| PID | Yes vs. No | 1.55 (0.97-2.48) | 0.0659 |

| Surgery | |||

| Laparoscopic salpingoplasty + hydrotubation | 1.0 | ||

| Hysteroscopic-laparoscopic salpingoplasty + hydrotubation | 1.01 (0.62-1.67) | 0.9597 | |

| Hydrotubation | --- | --- | |

| Preoperative scoring | Mild | 1.0 | |

| Moderate | 0.86 (0.55-1.33) | 0.4888 | |

| Severe | 0.44 (0.28-0.68) | 0.0003 | |

| Postoperative scoring | Mild | 1.0 | |

| Moderate | 0.41 (0.25-0.69) | 0.0007 | |

| Severe | --- | --- | |

PID: pelvic inflammatory disease.

The factors identified using univariate analyses with a P-value < 0.10 were added to a multivariate model. Results showed that preoperative score (P = 0.02), postoperative score (P = 0.02), pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) (P = 0.04) and preoperative disease course (P = 0.02) were all independently involved in the rate of intrauterine pregnancies (Table 7).

Table 7.

Multivariate analyses of factors affecting the rate of intrauterine pregnancies

| Factors | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative scoring | 0.75 (0.59-0.95) | 0.0155 | |

| Postoperative scoring | 0.53 (0.31-0.91) | 0.0203 | |

| PID | Yes vs. No | 1.64 (1.03-2.63) | 0.0387 |

| Preoperative disease course | 0.88 (0.78-0.98) | 0.0232 | |

PID: pelvic inflammatory disease.

Table 8 shows the univariate analysis of factors involved in the rate of live births. Age (HR = 0.95, 95% CI: 0.91-1.00, P = 0.03), PID (HR = 1.71, 95% CI: 1.05-2.78, P = 0.03), preoperative TFI score (severe TFI: HR = 0.49, 95% CI: 0.30-0.80, P = 0.004) and postoperative TFI score (moderate TFI: HR = 0.44, 95% CI: 0.26-0.76, P = 0.003) had an impact on the rate of live births.

Table 8.

Univariate analyses of factors affecting the rate of live births

| Factors | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.95 (0.91-1.00) | 0.0333 | |

| Preoperative disease course | 0.90 (0.80-1.00) | 0.0573 | |

| Number of pregnancies | 0.94 (0.79-1.12) | 0.4915 | |

| Ectopic pregnancy | Yes vs. No | 0.56 (0.25-1.22) | 0.1453 |

| Other operations | Yes vs. No | 1.12 (0.64-1.96) | 0.6910 |

| Ovarian tumors | Yes vs. No | 0.75 (0.10-5.35) | 0.7714 |

| PID | Yes vs. No | 1.71 (1.05-2.78) | 0.0301 |

| Surgery | |||

| Laparoscopic salpingoplasty + hydrotubation | 1.0 | ||

| Hysteroscopic-laparoscopic salpingoplasty + hydrotubation | 1.10 (0.66-1.85) | 0.7078 | |

| Hydrotubation | --- | --- | |

| Preoperative scoring | Mild | 1.0 | |

| Moderate | 0.99 (0.62-1.60 | 0.9788 | |

| Severe | 0.49 (0.30-0.80) | 0.0044 | |

| Postoperative scoring | Mild | 1.0 | |

| Moderate | 0.44 (0.26-0.76) | 0.0032 | |

| Severe | --- | --- | |

PID: pelvic inflammatory disease.

The factors identified using univariate analyses with a P-value < 0.10 were added to a multivariate model. Results show that postoperative score (P = 0.001), PID (P = 0.03) and age (P = 0.03) were all independently involved in the rate of live births (Table 9).

Table 9.

Multivariate analysis of factors affecting the rate of live births

| Factors | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Postoperative scoring | 0.41 (0.24-0.70) | 0.0012 | |

| PID | Yes vs. No | 1.74 (1.07-2.83) | 0.0255 |

| Age | 0.95 (0.90-0.99) | 0.0311 | |

PID: pelvic inflammatory disease.

Discussion

The present study was motivated by the need for a better prognosis system for TFI patients who undergo tubal surgery. Our results showed that all three surgical approaches used in our centre (laparoscopic salpingoplasty and hydrotubation, hysteroscopic-laparoscopic salpingoplasty and hydrotubation, and laparoscopic hydrotubation) improved the TFI score. Our results also showed that the preoperative and postoperative TFI score classifications were significantly associated with pregnancy outcomes. Multivariate analysis showed that the preoperative disease course, the preoperative TFI score and the postoperative TFI score were independently associated with the rate of intrauterine pregnancies. Multivariate analysis also showed that the postoperative TFI score, PID and age were independently associated with the rate of live births.

Using the AFS-r system, patients classified with the worst adhesions had no pregnancy at all, while the pregnancy rate was 42.9% in the best adhesion level [18]. The Hulka tubal classification system is a system assessing the tubal conditions according to the degrees of adnexal adhesions [3]. The evaluation is based on: 1) extent of ovarian involvement in adhesive disease, 2) nature of the adhesions, 3) fimbrial patency, and 4) isthmic patency. This system was used in 177 patients undergoing laparoscopic salpingoplasty: the postoperative pregnancy rate was 13.6% and live birth rate was only 9%, while the ectopic pregnancy rate was 3.4%; however, this study favored patients with relatively severe tubal diseases [19]. A retrospective cohort study using the Hull & Rutherford system classified tubal injuries into three levels: level I was mild tubal adhesions; level II was unilateral severe tubal injuries; and level III was bilateral severe tubal injuries. The study revealed that ectopic pregnancy rate was associated with the injury level, but not infertility; the postoperative live birth rates of the three levels were 69%, 48% and 9%, respectively [20]. Their multivariate analysis showed that the hazard ratios between levels III and I, and between levels III and II were 13.7 and 6.54, respectively. Therefore, this system could be used to determine the prognosis of tubal surgery into good, general or poor [21]. These study showed that the Hull & Rutherford system was effective, but that it also subjective in the assessment of the three levels.

Falloposcopy allows the direct observation of the inner tubal condition and to classify it using evaluations of mucosal adhesions between the folds, extensive adhesions between mucosa layers, appearance of scattered smooth regions and complete losses of mucosal structures. Marana et al. [10] observed in 51 patients with adnexal adhesions (24 cases) or hydrosalpinxes (27 cases) who had undergone laparoscopic tubo-ovarian adhesiolysis or salpingoplasties/falloposcopy that, based on AFS, the full-term birth rates of patients with normal fallopian mucosa in tubo-ovarian adhesiolysis was 71% and 64% in salpingoplasty patients, and that there were no intrauterine pregnancies in patients with severe intrafallopian injuries. Comparing the falloposcopic results with AFS assessments, it could be seen that AFS was not clearly related with postoperative outcomes.

In the present study, salpingoplasty significantly decreased the postoperative TFI scores. Furthermore, the postoperative TFI score was associated with both the intrauterine pregnancy and live births rates. Using this system, both pre- and postoperatively could improve the prognosis determination. However, TFI prognosis was most closely related with the postoperative scores.

In the present study, all three surgical approaches decreased TFI scores to a similar extent. Turjacanin-Pantelic et al [21] retrospectively analyzed 66 patients who had undergone salpingoplasty and observed that the prognosis of the laparotomic approach was not significantly different from the laparoscopic approach. Mossa et al [22] randomly assigned 224 patients with distal tubal occlusions to laparotomic microsurgery or laparoscopic surgery. After 24 months, the pregnancy rates between the two approaches were similar (43.7% vs. 41.6%). Ahmad et al [23] compared laparoscopy and laparotomy for distal tubal surgeries using a meta-analysis and found that there was no difference between the two approaches.

Based on the relationships between the preoperative TFI scores and prognosis, postoperative pregnancy outcomes in mild TFI patients were obviously higher than those of moderate and severe TFI patients, and that the infertility rate of severe TFI patients was obviously higher than in moderate TFI patients. Therefore, these results indicate that the scoring system can preliminarily evaluate prognosis. However, according to our observation, discrepancies between scores and prognosis could be due to differences in surgeons’ skills, and to different improvements in tubal conditions resulting from different surgical approaches. The long-term significance of the postoperative score will be presented in the prospective part of our studies.

At present, the new tubal classification system is unable to estimate the rate ectopic pregnancy. In addition, the present study may suffer from some limitations, which are mainly due to the retrospective nature of the study. Indeed, we had to work with the data already collected in the medical charts, but a prospective trial could allow us determining new factors that could be associated with prognosis. Furthermore, our sample size was small. Multicentre studies could allow us to strengthen the observed associations.

Conclusion

We devised a new classification system for TFI prognosis. Salpingoplasty improved these scores. Both pre- and post-operative TFI assessment using this new system associated with pregnancy prognosis.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Miller JH, Weinberg RK, Canino NL, Klein NA, Soules MR. The pattern of infertility diagnoses in women of advanced reproductive age. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:952–957. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70331-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guzick DS, Silliman NP, Adamson GD, Buttram VC Jr, Canis M, Malinak LR, Schenken RS. Prediction of pregnancy in infertile women based on the American Society for Reproductive Medicine’s revised classification of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:822–829. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(97)81392-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hulka JF, Omran K, Berger GS. Classification of adnexal adhesions: a proposal and evaluation of its prognostic value. Fertil Steril. 1978;30:661–665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rutherford AJ, Jenkins JM. Hull and Rutherford classification of infertility. Hum Fertil (Camb) 2002;5:S41–45. doi: 10.1080/1464727022000199911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caspi E, Halperin Y, Bukovsky I. The importance of periadnexal adhesions in tubal reconstructive surgery for infertility. Fertil Steril. 1979;31:296–300. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)43877-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boer-Meisel ME, te Velde ER, Habbema JD, Kardaun JW. Predicting the pregnancy outcome in patients treated for hydrosalpinx: a prospective study. Fertil Steril. 1986;45:23–29. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)49091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mage G, Pouly JL, de Joliniere JB, Chabrand S, Riouallon A, Bruhat MA. A preoperative classification to predict the intrauterine and ectopic pregnancy rates after distal tubal microsurgery. Fertil Steril. 1986;46:807–810. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)49815-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu CH, Gocial B. A pelvic scoring system for infertility surgery. Int J Fertil. 1988;33:341–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marana R, Rizzi M, Muzii L, Catalano GF, Caruana P, Mancuso S. Correlation between the American Fertility Society classifications of adnexal adhesions and distal tubal occlusion, salpingoscopy, and reproductive outcome in tubal surgery. Fertil Steril. 1995;64:924–929. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)57903-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marana R, Catalano GF, Muzii L, Caruana P, Margutti F, Mancuso S. The prognostic role of salpingoscopy in laparoscopic tubal surgery. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:2991–2995. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.12.2991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buttram VC Jr. Evolution of the revised American Fertility Society classification of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1985;43:347–350. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)48429-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Revised American Fertility Society classification of endometriosis: 1985. Fertil Steril. 1985;43:351–352. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)48430-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canis M, Bouquet De Jolinieres J, Wattiez A, Pouly JL, Mage G, Manhes H, Bruhat MA. Classification of endometriosis. Baillieres Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;7:759–774. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3552(05)80462-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hull MG, Fleming CF. Tubal surgery versus assisted reproduction: assessing their role in infertility therapy. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 1995;7:160–167. doi: 10.1097/00001703-199506000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lilford RJ, Watson AJ. Has in-vitro fertilization made salpingostomy obsolete? Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1990;97:557–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1990.tb02540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winston RM, Margara RA. Microsurgical salpingostomy is not an obsolete procedure. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1991;98:637–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1991.tb13448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singhal V, Li TC, Cooke ID. An analysis of factors influencing the outcome of 232 consecutive tubal microsurgery cases. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1991;98:628–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1991.tb13447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alborzi S, Motazedian S, Parsanezhad ME. Chance of adhesion formation after laparoscopic salpingo-ovariolysis: is there a place for second-look laparoscopy? J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10:172–176. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(05)60294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dyer SJ, Tregoning SK. Laparoscopic reconstructive tubal surgery in a tertiary referral centre--a review of 177 cases. S Afr Med J. 2000;90:1015–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akande VA, Cahill DJ, Wardle PG, Rutherford AJ, Jenkins JM. The predictive value of the “Hull & Rutherford” classification for tubal damage. BJOG. 2004;111:1236–1241. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turjacanin-Pantelić D, Bojović-Jović D, Arsić B, Garalejić E. [Results of modem tuboperitoneal infertility treatment] Vojnosanit Pregl. 2009;66:57–62. doi: 10.2298/vsp0901057t. [Article in Serbian] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mossa B, Patella A, Ebano V, Pacifici E, Mossa S, Marziani R. Microsurgery versus laparoscopy in distal tubal obstruction hysterosalpingographically or laparoscopically investigated. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2005;32:169–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahmad G, Watson AJ, Metwally M. Laparoscopy or laparotomy for distal tubal surgery? A meta-analysis. Hum Fertil (Camb) 2007;10:43–47. doi: 10.1080/14647270600977820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]