Abstract

To study the change of maternal pulmonary function when ropivacaine and bupivacaine were used in spinal anesthesia for cesarean section, 40 ASA physical status I and II parturient scheduled to undergo cesarean section were randomly divided into bupivacaine and ropivacaine groups. Bupivacaine 9 mg and ropivacaine 14 mg were intrathecal injected respectively. FVC, FEV1 and PEFR were measured with spirometry before anesthesia and 2 h after intrathecal injection. Anesthesia level, the degree of motor block and VAS were also recorded. Results: The final level of sensory blockade was not different between groups. Forced vital capacity was significantly decreased with bupivacaine (3.0 ± 0.4 L to 2.7 ± 0.3 L, P < 0.05) and ropivacaine (2.9 ± 0.4 L to 2.5 ± 0.4 L, P < 0.05) while there were no difference between two groups. Forced expiratory volume during the first second and Peak expiratory flow rate were not decreased in each group. The degree of motor block in group R was less than group B at 2 h after intrathecal injection. Conclusions: Decreases in maternal pulmonary function tests were similar following spinal anaesthesia with bupivacaine or ropivacaine for cesarean section. The clinical maternal effects of these alterations appeared negligible.

Keywords: Bupivacaine, ropivacaine, anesthesia, pulmonary function, cesarean-section

Introduction

Spinal anesthesia is safer to parturient and new born babies which make it become the first choice in obstetric anesthesia [1]. Parturients would hardly feel discomfort when the sensory block level reaches T4 in cesarean section [2]. However, the high level block of sensory and motor nerve will restrict cough reflex and lung expansion. Bupivacaine was widely used in spinal anesthesia while it could remarkably reduce the postoperative pulmonary function [2,3]. Ropivacaine is a new long-acting amide local anesthetic agent with differential sensory-motor block. It was authorized to be used in subarachnoid space block recent years. The effect of motor block is weaker in ropivacaine than bupivacaine [4]. How is the effect of ropivacaine used in subarachnoid space on pulmonary function of parturients undergoing cesarean section and whether it is benefit to the recovery of pulmonary function postoperatively remain unknown. The aim of current investigation was to compare the influence of ropivacaine and bupivacaine used in spinal anesthesia on postoperative pulmonary function of parturients after cesarean section. Our working hypothesis was that pulmonary function would be recovered more quickly in ropivacaine group at 2 h after anesthesia.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval for this study was provided by the Ethical Committee of Obstetrics & Gynecology Hospital of Fudan University. After obtaining written informed consent, 40 parturients who tended to have cesarean section (ASA physical status I-II, age from 22 to 34) were randomized into two groups as directed by the contents of a sealed opaque envelope: Bupivacaine group (B) and Ropivacaine group (R). Exclusion criteria were BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2, contraindication in spinal anesthesia, history of cardiac or pneumonic diseases, history of smoke or history of upper respiratory tract infection in two weeks.

The day before surgery, anesthesiologists introduced Pony FX portable pulmonary function recorder (COSMED, Italy) to parturients through graphic. Method for measurement: each parturient in a left side dorsal position with 15-20° head-up. Forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) were recorded. Spirometry was conducted three times and the best measurement was used for further analysis. Patients received intravenous therapy with 500 ml RL routinely after transfer to the operating theatre. Blood pressure, pulse oxygen saturation of blood and electrocardiogram were monitored.

Parturients were performed combined spinal epidural anesthesia (CSEA) lying in the right lateral position. After identifying the epidural space at the L3-L4 interspace, we used a 25-G pencil point needle (Whitacre, BD company) to get into subarachnoid space through epidural space by needle in needle method. Patients in B group were administered 0.5% bupivacaine 1.8 ml which was diluted to 3 ml by cerebrospinal fluid and was administered in 10 seconds. Those in R group were administered 1% ropivacaine 1.4 ml which was diluted to 3 ml by cerebrospinal fluid and was administered in 10 seconds. Epidural catheter was threaded and fixed into epidural space. After parturient was turned on her back, the level of sensory and motor blockade was assessed every 3 minutes after medicine was administered into subarachnoid space until the level fixed. The assessment of sensory blockade used needle point method. The level at which pain disappeared was recorded. The blockade of movement was according to the modified Bromage score (0: no motor paralysis; 1: inability to raise extended leg, but able to move knee and foot; 2: inability to raise extended leg or to move knee, but able to move foot; 3: inability to raise extended leg or to move knee and foot). Anesthesiologists who performed assessment and measurement were blinded to the identity of the groups. Time between skin section and delivery as well as the Apgar score of new born baby were recorded. Parturients received intravenous Tramadol 100 mg and Flurbiprofen Axetil 50 mg after delivery to avoid postoperative pain and influence on pulmonary function by opioid medicine spinal administration. At post anesthesia care unit Spirometric measurements and VAS score were performed 1 h (T1), 1.5 h (T2) and 2 h (T3) after the subarachnoid space administration. The best measurements, the level of sensory blockade, Bromage score, mean arterial blood pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR) and SpO2 of each time point were recorded.

Situations as follows were withdrawn from the investigation: failure to perform CSEA; surgery duration above 1 hour; haemorrhage more than 1000ml; epidural bolus was needed.

The sample size estimated for this study (n = 36) was determined a priori to detect a 15% difference in FEV1 between two groups at α = 0.05, 1-β = 0.80. Statistical analysis was performed by using the SPSS 13.0 software package. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (x̅ ± s). An unpaired two-tailed Student’s test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for normally distributed variables. For not normally distributed behavioral data, a nonparametric analysis approach Kruskal-Wallis test was used to assess group effects. A probability level of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The protocol was completed in 36 of the 40 parturients who were enrolled in the study. Reasons for study exclusion were failure to perform CSEA (n = 1 in each group) and epidural bolus (n = 1 in each group).

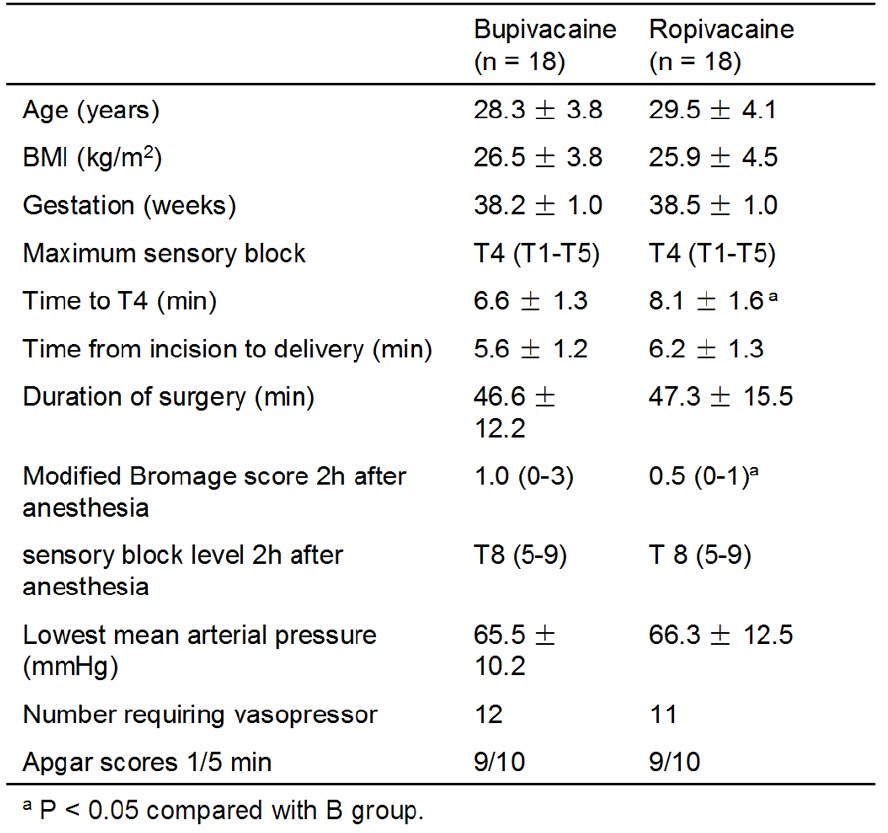

The two groups did not differ with respect to age, BMI, pregnant week, time between skin section and delivery, Apgar score of new born baby, MAP, HR and SpO2. The maximum sensory block level was T4 and the time reached that level were 6.6 minutes and 8.1 minutes after subarachnoid space administration respectively. The degree of motor block in group R was less than group B at 2 h after intrathecal injection. There was no difference in sensory blockade at 2 h after intrathecal injection. (Table 1) Although the median sensory block height appears to be T4 as assessed by pinprick, no patients experienced discomfort during surgery.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and outcome of spinal anaesthesia

|

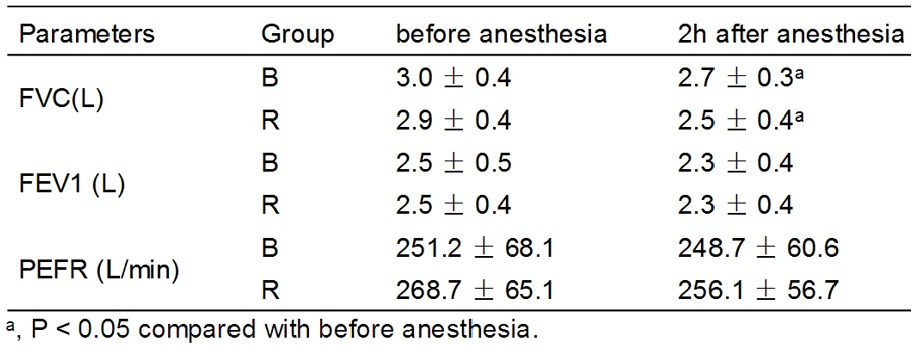

Forced vital capacity was significantly decreased with bupivacaine (3.0 ± 0.4 L to 2.7 ± 0.3 L, P < 0.05) and ropivacaine (2.9 ± 0.4 L to 2.5 ± 0.4 L, P < 0.05) while there were no difference between two groups. Forced expiratory volume during the first second and Peak expiratory flow rate were not decreased in each group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of FVC, FEV1 and PEFR before anesthesia and 2h after anesthesia in two groups (n = 18)

|

Discussion

There was a paper reported that parturients presenting for cesarean section had a higher risk of pulmonary atelectasis than those had experienced vaginal delivery [5]. Differences in partal physiology and influences of spinal anesthesia on pulmonary function were main reasons. The high level blockade needed for surgery would reduce the lung volume and respiratory drive of patients by affecting abdominal muscles and intercostal muscles [6,7]. Our results documented that spinal administration of either ropivacaine or bupivacaine was associated with statistically significant decreases in respiratory variables along with past investigations [6,7]. In our previous study (unpublished data), modified bromage score was not significantly improved until 2 h after intrathecal injection with bupivacaine or ropivacaine. So we choose this time point to test the parturients’ pulmonary function. Our hypothesis that pulmonary function would be recovered more quickly in ropivacaine group at 2 h after anesthesia was not meet. No difference was found between bupivacaine and ropivacaine in pulmonary function variables. However, the clinical importance of this finding remains unclear. The propensity of ropivacaine to cause motor block is thought to be less than that of bupivacaine. One reason for this differential block may be preferential blockade of sodium channels specific for nociceptive neurones by ropivacaine [8]. A recent investigation in parturients undergoing elective cesarean section found that intrathecal ropivacaine was shown to cause less intense and shorter-lasting motor block than bupivacaine [9]. However, Camorcia et al postulated that the differences in motor block among local anesthetics were less distinctive when used for spinal than for epidural anesthesia [10].

It has been shown that the ropivacaine/bupivacaine motor blocking potency ratio was 0.66 (95% CI 0.52~0.82) [11]. Camorcia et al reported [10] that the ratio of ropivacaine/bupivacaine intrathecal ED50 for motor block was 0.59. The dosage of ropivacaine and bupivacaine we used for spinal anesthesia was 14 mg and 9 mg respectively by considering these references.

There were several investigations focused on the effect of bupivacaine spinal administration on respiratory function [2,6,12,13] while similar investigations were lacking for ropivacaine. Ropivacaine is a new long-acting amide local anesthetic agent. It was authorized to be used in subarachnoid space block recent years. The effect of motor block is weaker in ropivacaine than bupivacaine [4]. Lirk et al [14] observed pulmonary function of parturients undergoing spinal anesthesia using either bupivacaine 10 mg or ropivacaine 20 mg. The results showed that FVC and PEFR decreased 3-6% and 6-13% respectively in both groups.

The dynamic pulmonary function tests were affected to different degrees by spinal anesthesia. In our study, FVC was negatively influenced by spinal anesthesia using bupivacaine and ropivacaine, which is in accord with previous investigations [2,13]. More specifically, FEV1 did not decrease significantly in each of the study groups, which is consistent in other studies with bupivacaine [6,13]. By contrast, Kelly et al found significant decreases in FEV1 after spinal anesthesia [2], but their results could have been confounded by an open abdomen, which has been previously shown to substantially influence pulmonary function [13]. PEFR is an important indicator for the effectiveness of cough [12]. Adequate cough postoperatively plays an essential role in preventing respiratory complications. We did not detect a significant deterioration of PEFR after spinal anaesthesia for cesarean delivery, which is in accord with previous investigations [13]. While Kelly et al [2] reported statistically significant decreases. This disparity may be explained by different doses of bupivacaine: Kelly et al. gave a dose of 12.5 mg, compared to our 9 mg. In addition, Kelly measured pulmonary function before spinal anesthesia and during surgery, when the abdomen was open, which may further compromise ventilation [2].

Some factors may interfere with the measurement of pulmonary function including compliance of patients, position for assessment, pain of uterine contraction or skin section. The protocol used in current study chose to the same position, repeated measurement with the best result, VAS score was controlled less than 3 to make parturients feel free of pain. All the assessments were performed by the same anesthesiologist. Efforts were done to make the data recorded reliable.

High level blockade in spinal anesthesia influences respiratory function after cesarean section greatly. Although the ratio of pulmonary complication happened in healthy parturients was minor, serious concern should take towards parturients with history of cardiac and pulmonary diseases and obese patients. Medicine with few influence and quick recovery properties on respiratory function is important in order to reduce the pulmonary complication and accelerate the function recovery. In conclusion, both of ropivacaine and bupivacaine administered in spinal anesthesia could decrease postoperative pulmonary function of parturients who experienced cesarean section. There was no significant difference in the effect of function recovery between two medicines.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Obstetric Anesthesia. Practice guidelines for obstetric anesthesia: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Obstetric Anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:843–63. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000264744.63275.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelly MC, Fitzpatrick KT, Hill DA. Respiratory effects of spinal anaesthesia for cesarean section. Anaesthesia. 1996;51:1120–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1996.tb15046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Ungern-Sternberg BS, Regli A, Bucher E, Reber A, Schneider MC. Impact of spinal anaesthesia and obesity on maternal respiratory function during elective cesarean section. Anaesthesia. 2004;59:743–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.03832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simpson D, Curran MP, Oldfield V, Keating GM. Ropivacaine: a review of its use in regional anaesthesia and acute pain management. Drugs. 2005;65:2675–717. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200565180-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meira MN, Carvalho CR, Galizia MS, Borges JB, Kondo MM, Zugaib M, Vieira JE. A telectasis observed by computerized tomography after Cesarean section. Br J Anaesth. 2010;104:746–50. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrop-Griffiths AW, Ravalia A, Browne DA, Robinson PN. Regional anaesthesia and cough effectiveness. A study in patients undergoing cesarean section. Anaesthesia. 1991;46:11–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1991.tb09304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Troyer A, Kirkwood PA, Wilson TA. Respiratory action of the intercostal muscles. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:717–56. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00007.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oda A, Ohashi H, Komori S, Iida H, Dohi S. Characteristics of ropivacaine block of Na+ channels in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Anesth Analg. 2000;91:1213–20. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200011000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whiteside JB, Burke D, Wildsmith JA. Comparison of ropivacaine 0.5% (in glucose 5%) with bupivacaine 0.5% (in glucose 8%) for spinal anaesthesia for elective surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2003;90:304–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeg077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Camorcia M, Capogna G, Berritta C, Columb MO. The relative potencies for motor block after intrathecal ropivacaine, levobupivacaine, and bupivacaine. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:904–7. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000256912.54023.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lacassie HJ, Columb MO, Lacassie HP, Lantadilla RA. The relative motor blocking potencies of epidural bupivacaine and ropivacaine in labor. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:204–8. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200207000-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gamil M. Serial peak expiratory flow rates in mothers during Cesarean section under extradural anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 1989;62:415–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/62.4.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conn DA, Moffat AC, McCallum GD, Thorburn J. Changes in pulmonary function tests during spinal anaesthesia for cesarean section. Int J Obstet Anesth. 1993;2:12–4. doi: 10.1016/0959-289x(93)90023-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lirk P, Kleber N, Mitterschiffthaler G, Keller C, Benzer A, Putz G. Pulmonary effects of bupivacaine, ropivacaine, and levobupivacaine in parturients undergoing spinal anaesthesia for elective cesarean delivery: A randomised controlled study. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2010;19:287–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]