Abstract

To investigate the effects of Ulinastatin (UTI) in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury in rats and whether this effect might be related to Aquaporin 4 (AQP4), one hundred and eighty adult male Sprague Dawley (SD) rats, weighing 230-280 g, were randomly divided into 3 groups: sham (S) group, IR group and UTI (U) group. Every group was further divided into 3 sub-groups: 6 h group, 24 h group and 48 h group. The transient focal IR injury was induced by inserting a silicone-coater monofilament nylon suture (0.28 mm) from the right external carotid artery to the origin of the left middle cerebral artery. The suture was removed after 2 h to allow reperfusion. UTI treatment group was injected with UTI 100000 u/kg at the beginning of the reperfusion period, while S group and IR group were injected with the same volume of saline. Samples were taken according to the reperfusion time (6 h, 12 h and 24 h). Infract volume was measured by triphenyl tetrazolium chloride staining, and brain water content was determined by wet-dry weight method and neurological scores were checked with a five-point scale. Expression levels of AQP4 were checked with immunohistochemistry and Western blot. Results: Compared with S group, the infarct volume, water content, neurological scores and AQP4 levels in the rat brain tissues were significantly increased in IR group. Administration of UTI significantly decreased the infarct volume, water content of the brain tissue and neurological scores. Moreover, the expression levels of AQP4 were also down-regulated by UTI treatment. Conclusion: UTI improves cerebral IR injury in rats potentially via decreasing the expression levels of AQP4.

Keywords: Ulinastatin, cerebral ischemic reperfusion, brain edema, aquaporin 4

Introduction

Cerebral ischemia is among the diseases that most compromise the human species [1]. Occlusion of a cerebral artery impairs blood flow and will lead to neuronal death. Early reperfusion is necessary. However, reperfusion of the tissue is also associated with inflammation, increased reactive oxygen species, necrosis and apoptosis. These damages to the brain will continue even after the blood flow is restored and cause cerebral edema [2]. Thus, ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury is a complicated pathologic procedure [2]. Novel method to prevent the IR injury is highly needed [1,2].

Ulinastatin (urinary trypsin inhibitor, UTI) is a 67 kDa glycoprotein purified from the urine of healthy humans. With its anti-protease and anti-inflammatory effects, UTI has been widely used as a drug for patients with acute inflammatory disorders, such as disseminated intravascular coagulation, shock, and pancreatitis [3]. Some studies have reported that UTI protected against cerebral IR injury [4-6]. Aquaporin-4 (AQP4) is a water-channel protein enriched in the brain. It controls water fluxes into and out of the brain parenchyma and plays an important role in cerebral ischemia. In the present study, we aim to investigate the effects of UTI in cerebral IR injury and whether this effect might be related to AQP4.

Materials and methods

This study was conducted in accordance to the guidelines for the care and use of animals in research, and under the protocols approved by the Guangzhou University of Connecticut Animal Care and Use Committee.

Establishment of cerebral IR model in rat

One hundred and eighty adult male SD rats, weighing 230-280 g, obtained from the Experimental Animal Center of Guangdong was used in this study. These rats were randomly divided into 3 groups: Sham (S) group, IR group and UTI treatment (U) group. IR group and U group were further divided into 3 sub-groups: 6 h reperfusion group, 24 h reperfusion group and 48 h reperfusion group. Middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) was induced by intraluminal filament method as described previously [7]. Briefly, after the exposure of right common carotid artery (CCA), internal carotid artery (ICA) and the external carotid artery (ECA), a silicone-coater monofilament nylon suture (0.28 mm) was carefully inserted from the CCA into the ICA and was advanced towards to occlude the origin of the left middle cerebral artery (MCA) until a light resistance was felt (18-20 mm from CCA bifurcation). Two hours later, the suture was removed to allow reperfusion. U group was injected with UTI 100000 u/kg at the beginning of the reperfusion period, while S group and IR group were injected with the same volume of saline. Samples were taken according to the reperfusion time (6 h, 12 h and 24 h).

Determination of the neurological score

The neurological deficit score was assessed according to previous described [8]. At different time points of reperfusion, the animals were scored blindly based on a five-point scale: 0: normal; 1: drags forepaw, twisting when lifted; 2: circling spontaneously; 3: falls; 4: does not walk, comatose; 5: dead.

Measurement of cerebral infarct volume

At the end of the reperfusion period, animals were anesthetized with 10% chloral hydrate and the brain was separated and kept at -20°C for 30 min for uniform sectioning. The brain was sliced into 2 mm thick transverse sections and was allowed to thaw at room temperature. Each slice was incubated separately in 1% triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) (SIGMA Chemical Co., MO, USA) for 20 min at 37°C. TTC staining could discriminate infracted brain tissue (unstained and appearing white) from non-infarcted brain tissue (deep red). The cerebral infarction was expressed as the ratio of the infarct volume to total brain volume.

Calculation of brain water contents

Four days after MCAO, rats were killed and brains were removed. The pons and olfactory bulb were removed and the brains were weighted to obtain their wet weight (ww). Thereafter brains were dried at 110°C for 24 h for determining their dry weight (dw). Brain water content was calculated by using the following formula: (ww-dw)/ww × 100 as an index for brain edema.

Immunohistochemistry for AQP4 expression

Slices from the brain tissue were serially cut into 20 μm thick frontal sections. All sections were incubated in 30% H2O2 in Tris-buffered saline (PBS) for 30 min at room temperature to quench endogenous peroxidase. Sections were incubated with 5% fetal bovine serum (Fredensborg, Denmark, cat. no.: 04009-1B) for 30 min at room temperature to block non-specific binding. After that, sections were incubated with rabbit anti-AQP4 diluted at 1:200 overnight at 4°C (Alomone Labs Ltd., cat. no.: AQP-004). The primary antibody of AQP-4 was detected by using biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG diluted at 1:400 (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no.: 3275) for 30 min at room temperature followed by streptavidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (StreptABComplex/HRP, DAKO, DK, cat. no.: K377) prepared for 30 min at room temperature. The immunoreaction was visualized using 0.015% H2O2 in 3, 3-diaminobenzidine-tetrahydrochloride (DAB) as chromogen for 10 min at room temperature. The sections were counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin, and mounted, and then examined under an Axioskope microscope.

Western blot for AQP4 expression

Left parietal lobe cortex was homogenized in 10 mmol/L Tris homogenization buffer (pH 7.4) with protease inhibitors (1 tablet in 50 ml; Sigma, USA). The samples were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 20 min and the supernatant was collected for Western blot. After determining the protein concentrations of the supernatants (BCA method, standard BSA), 50 μg protein of each sample was loaded onto the 8% SDS gel, and was separated by electrophoresis and then was transferred to PVDF membrane. The membranes were incubated with rabbit anti-AQP4 polyclonal IgG (1:500, Boster, CHINA) or mouse anti-β-actin monoclonal IgG (1:1000, Boster, CHINA) overnight at 4°C. After being washed three times for 10 min with washing solution, the membranes were incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (1:2000, Boster, CHINA) or goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP (1:2000, Boster, CHINA). The immune-reactive bands were visualized by an ECL Western blotting detection kit (Pierce, USA) on light sensitive film.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the means ± SD. Differences among multiple groups were statistically analyzed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni test. Statistical significance was assumed if P < 0.05.

Result

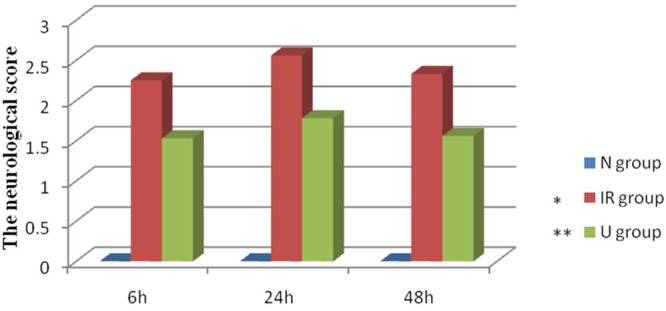

UTI improves the neurological score in cerebral IR

We investigated whether UTI could improve neurological scores in threats subjected to cerebral IR. As shown in Figure 1, compared with S group, the neurological scores of IR group significantly increased and reached a peak at 24 h. Administration of UTI could significantly reduce neurological scores in IR.

Figure 1.

Ulinastatin improves the neurological score in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion. Neurological scores of all groups. Date are expressed as Mean ± SEM (n = 5). *P < 0.05 vs. S group; **P < 0.05 vs. IR group.

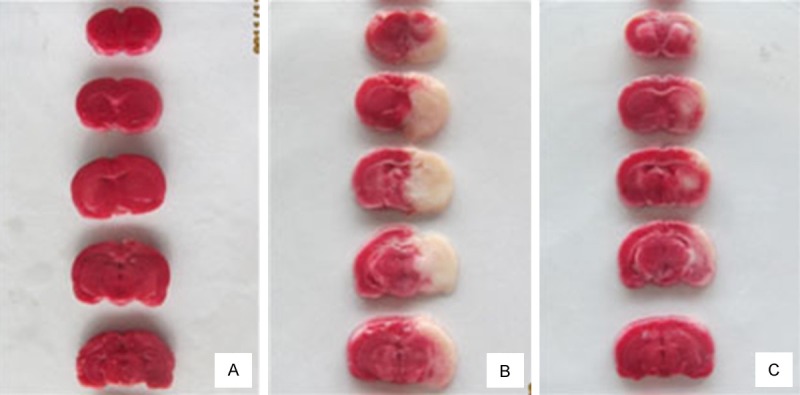

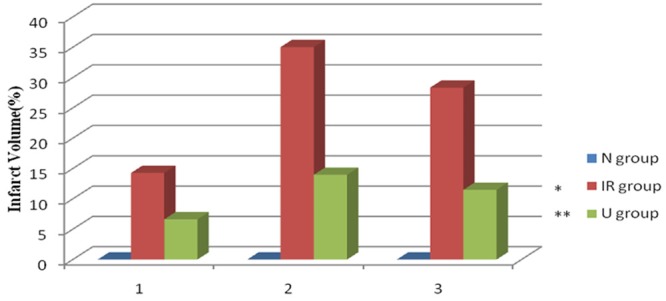

UTI decreases cerebral infarct volume in cerebral IR

To determine the cerebral infarct volume, TTC staining was used in the present study. The infarcted tissue of MCAO rats appeared white, whereas the normal non-infarcted tissue was red. Consistent with the results of neurological deficits, IR induced obvious infarct (Figure 2), indicating that an exacerbated brain damage occurred. Interestingly, UTI treatment also decreased cerebral infarct volume in rat subjected to IR (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Representative pictures of TTC staining. A: Infarct volume of Sham (S) group. B: Infarct volume of ischemia-reperfusion (IR) group. C: Infarct volume of Ulinastatin (U) treatment group.

Figure 3.

Ulinastatin decreases cerebral infarct volume in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion. Infarct volume of three groups. Date are expressed as Mean ± SEM (n = 5). *p < 0.05 vs. S group; **P < 0.05 vs. IR group.

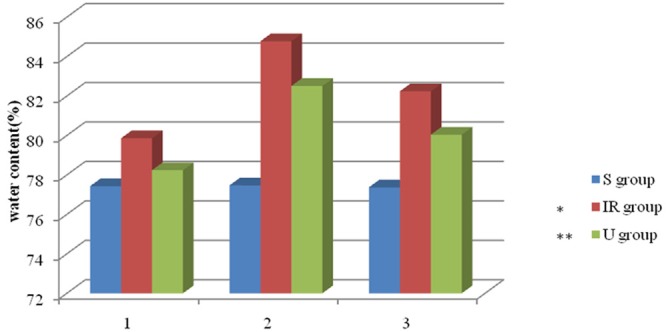

UTI reduces brain water contents in cerebral IR

The brain water content was used to evaluate cerebral edema. IR significantly increased the water content of the ischemic hemisphere and reached a peak at 24 h (Figure 4), whereas the water content of non-ischemic hemisphere remained unchanged. Administration of UTI at the beginning of reperfusion period significantly reduced the water content of the right hemisphere (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Ulinastatin reduces brain water contents in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion. Water content alterations after MCAO and reperfusion. Date are expressed as Mean ± SE (n = 5), *P < 0.05 vs. S Group; **P < 0.05 vs. IR group.

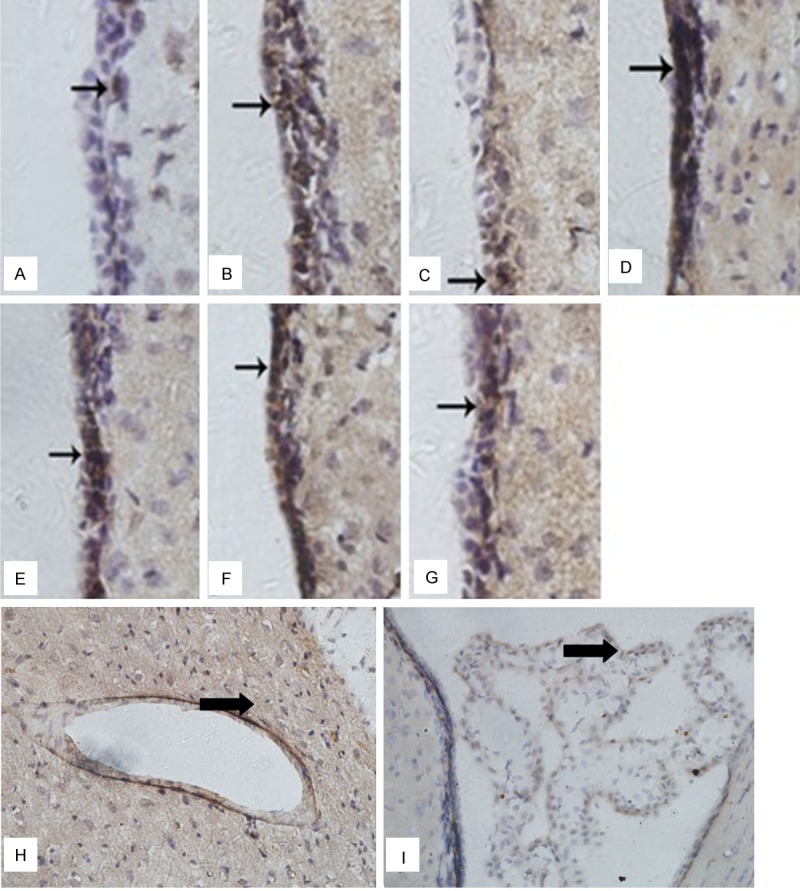

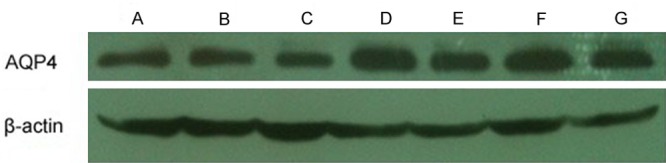

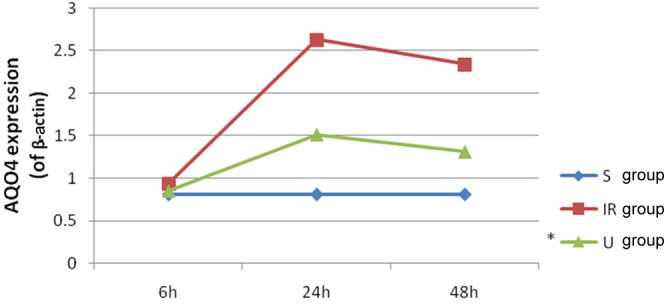

UTI down-regulates the expression level of AQP4 in cerebral IR

Immunohistochemistry and Western blot analysis were used to investigate the AQP4 expression patterns. Both methods consistently showed that IR reduced the expression level of AQP4 while it was suppressed by administration of UTI (Figures 5, 6 and 7), indicating that UTI might improve cerebral IR injury in rats potentially via decreasing the expression levels of AQP4.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemistry of Aquaporin-4 (AQP4) expressions in ependyma, choroid plexus and blood capillary. A: Sham (S) group. B: Ischemia-reperfusion (IR) 6 h group. C: Ulinastatin (U) 6 h group. D: IR 24 h group. E: U 24 h group. F: IR 48 h group. G: U 48 h group. H: Blood capillary. I: Choroid plexus. Expression of AQP4 was found in ependyma appeared clay bank. Date are expressed as Mean ± S.E.M (n = 5). IR group vs. S group, P < 0.05. U group vs. IR group, P < 0.05.

Figure 6.

Representative western blotting of AQP4 expression. A: Sham (S) group; B: Ischemia-reperfusion (IR) 6 h group; C: Ulinastatin (U) 6 h group; D: IR 24 h group; E: U 24 h group; F: IR 48 h group; G: U 48 h group.

Figure 7.

Ulinastatin down-regulates the expression level of AQP4 in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion. Date are expressed as Mean ± S.E.M (n = 5). IR group vs. S group, P < 0.05. U group vs IR group, P < 0.05.

Discussion

The major findings of the present study are as follows. Firstly, UTI improves the neurological score in cerebral IR. Secondly, UTI decreases cerebral infarct volume in cerebral IR. Thirdly, UTI reduces brain water contents in cerebral IR. Finally, UTI down-regulates the expression level of AQP4 in cerebral IR.

AQP water-channel proteins are a family of membrane channels that serve as selective pores through which water crosses the plasma membranes of many human tissues and cell types [9-12]. To date, 13 mammalian AQPs have been cloned and identified in human.Among them, AQP4 is a water-selective transporter originally cloned in 1994 from lung tissue and has been shown to be enriched in the brain [9-12]. The role of AQP4 in brain edema is still on debate [13,14]. One study has showed that mortality after acute water intoxication and ischemic stroke was markedly reduced in AQP4-null mice, which was associated with reduced blood-brain barrier water permeability and decreased rate of water flow into the brain parenchyma. However, another study has showed that AQP4-null mice had more brain swelling compared with wild-type mice after cortical freeze injury and brain tumor implantation [14]. In the present study, a predominant expression of AQP4 was identified in ependyma, choroid plexus and blood capillary by immunocytochemistry. The results of our study indicate that AQP4 is expressed at the membrane, which adjust water in the brain, while it is much less expressed in cerebral parenchyma. We also found that in MACO model, infarct sizes and brain water contents were positively correlated with the expression of AQP4. It is speculated that over-expression of AQP4 enhances a rapid influx of water and is responsible for the infarct of brain tissue after focal brain ischemia. However, Western blot showed no difference of AQP4 expression between 6 h IR group and S group. Another report also indicated that in the early stage of cerebral edema, AQP4 was not increased, and was even reduced following the exacerbation of brain [15]. The reduction of AQP4 expression prevents water fluxed into cerebral cell to protect brain tissue. Thus, it may be a self-protection of the brain.

The main objective of this study was to characterize the effects of UTI in cerebral IR injury and whether this effect might be related to AQP4. UTI is a human urinary trypsin inhibitor. A previous study has showed that UTI offered a protective effect against cerebral IR injury [16]. However, in our study, we identified the downregulation of AQP4 in a rat MCAO model in UTI treatment group accompanied by an obvious reduction in cerebral edema. Meanwhile, in the UTI treatment group, infarct sizes and brain water contents were also decreased. It is speculated that AQP4 down-regulation may alleviate cerebral edema. Thus, suppressing expression of AQP4 in the early stage of IR injury might be an alternative way for brain protection.

In conclusion, UTI improves cerebral IR injury in rats potentially via decreasing the expression levels of AQP4. Administration of UTI might be a novel way for cerebral protection.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the grants from Guangzhou Medical University (HS. Huang).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Colli BO, Tirapelli DP, Carlotti CG Jr, Lopes Lda S, Tirapelli LF. Biochemical evaluation of focal non-reperfusion cerebral ischemia by middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2008;66:725–730. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2008000500023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu D, Du W, Zhao L, Davey AK, Wang J. The neuroprotective effects of isosteviol against focal cerebral ischemia injury induced by middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Planta Med. 2008;74:816–821. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1074557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen CC, Wang SS, Lee FY. Action of antiproteases on the inflammatory response in acute pancreatitis. JOP. 2007;8:488–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abe H, Sugino N, Matsuda T, Kanamaru T, Oyanagi S, Mori H. Effect of ulinastatin on delayed neuronal death in the gerbil hippocampus. Masui. 1996;45:38–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yano T, Anraku S, Nakayama R, Ushijima K. Neuroprotective effect of urinary trypsin inhibitor against focal cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:465–473. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200302000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koga Y, Fujita M, Tsuruta R, Koda Y, Nakahara T, Yagi T, Aoki T, Kobayashi C, Izumi T, Kasaoka S, Yuasa M, Maekawa T. Urinary trypsin inhibitor suppresses excessive superoxide anion radical generation in blood, oxidative stress, early inflammation, and endothelial injury in forebrain ischemia/reperfusion rats. Neurol Res. 2010;32:925–932. doi: 10.1179/016164110X12645013515133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kikuchi K, Kawahara KI, Tancharoen S, Matsuda F, Morimoto Y, Ito T, Biswas KK, Takenouchi K, Miura N, Oyama Y, Nawa Y, Arimura N, Iwata M, Tajima Y, Kuramoto T, Nakayama K, Shigemori M, Yoshida Y, Hashiguchi T, Maruyama I. The free-radical scavenger edaravone rescues rats from cerebral infarction by attenuating the release of high-mobility group box-1 in neuronal cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329:865–874. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.149484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Longa EZ, Weinstein PR, Carlson S, Cummins R. Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion without craniectomy in rats. Stroke. 1989;20:84–91. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hasegawa H, Ma T, Skach W, Matthay MA, Verkman AS. Molecular cloning of a mercurial-insensitive water channel expressed in selected water-transporting tissues. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:5497–5500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang B, Ma T, Verkman AS. cDNA cloning, gene organization, and chromosomal localization of a human mercurial insensitive water channel. Evidence for distinct transcriptional units. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22907–22913. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.39.22907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nielsen S, Nagelhus EA, Amiry-Moghaddam M, Bourque C, Agre P, Ottersen OP. Specialized membrane domains for water transport in glial cells: high-resolution immunogold cytochemisty of aquaporin-4 in rat brain. J Neurosci. 1997;17:171–180. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00171.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jung JS, Bhat RV, Preston GM, Guggino WB, Baraban JM, Agre P. Molecular characterization of an aquaporin cDNA from brain: canidate osmoreceptor and regulator of water balance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:13052–13056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.13052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manley GT, Fujimura M, Ma T, Noshita N, Filiz F, Bollen AW, Chan P, Verkman AS. Aquaporin-4 deletion in mice reduces brain edema after acute water intoxication and ischemic stroke. Nat Med. 2000;6:159–163. doi: 10.1038/72256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papadopoulos MC, Manley GT, Krishna S, Verkman AS. Aquaporin-4 facilitates reabsorption of excess fluid in vasogenic brain edema. FASEB J. 2004;18:1291–1293. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1723fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeng XN, Xie LL, Liang R, Sun XL, Fan Y, Hu G. AQP4 Knockout Aggravates Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury in Mice. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012;18:388–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2012.00308.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yano T, Anraku S, Nakayama R, Ushijima K. Neuroprotective effect of urinary trypsin inhibitor against focal cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury in rats. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:465–473. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200302000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]