Abstract

Reactive oxygen species (ROS), including hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), are among the important second messengers in abscisic acid (ABA) signaling in guard cells. In this study, to investigate specific roles of H2O2 in ABA signaling in guard cells, we examined the effects of mutations in the guard cell-expressed catalase (CAT) genes, CAT1 and CAT3, and of the CAT inhibitor 3-aminotriazole (AT) on stomatal movement. The cat3 and cat1 cat3 mutations significantly reduced CAT activities, leading to higher basal level of H2O2 in guard cells, when assessed by 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein, whereas they did not affect stomatal aperture size under non-stressed condition. In addition, AT-treatment at the concentrations that abolish CAT activities, showed trivial affect on stomatal aperture size, while basal H2O2 level increased extensively. In contrast, cat mutations and AT-treatment potentiated ABA-induced stomatal closure. Inducible ROS production triggered by ABA was observed in these mutants and wild type as well as in AT-treated guard cells. These results suggest that the ABA-inducible cytosolic H2O2 elevation functions in ABA-induced stomatal closure, while constitutive raise of H2O2 did not caused stomatal closure.

Keywords: Abscisic acid, Catalase, Guard cells, Hydrogen peroxide

Introduction

Guard cells, which form stomatal pores in the epidermis of aerial parts of higher plants, respond to numerous biotic and abiotic stimuli (Schroeder et al., 2001; Hetherington and Woodward, 2003). The phytohormone, abscisic acid (ABA), which is synthesized in response to drought stress, is known to induce stomatal closure to reduce transpirational water loss (Iriving et al., 1992; Lee et al., 1999; Pei et al., 2000; Murata et al., 2001; Schroeder et al., 2001; Munemasa et al., 2007;2011; Islam et al., 2009; 2010a; b).

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is one of the major reactive oxygen species (ROS) and plays an important role as a second messenger in ABA-induced stomatal closure (Pei et al., 2000; Murata et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2001; Kwak et al., 2003; Bright et al., 2006; Miao et al., 2006). Genetic and pharmacological studies have demonstrated that the ROS production is mediated by NAD(P)H oxidases in ABA signaling in Arabidopsis guard cells (Pei et al., 2000; Kwak et al., 2003). The treatment with exogenous catalase (CAT) reduced H2O2 accumulation and inhibited ABA-induced stomatal closure (Zhang et al., 2001; Munemasa et al., 2007), consistent with the function of plasma membrane NAD(P)H oxidases in mediating stomatal closing (Kwak et al., 2003; Suhita et al., 2004). Direct application of ROS to guard cells is known to inhibit inward K+ channels and also to activate hyperpolarization-activated Ca2+-permeable ICa channels and stomatal closure (Pei et al., 2000; Murata et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2001). Therefore, accumulation of H2O2 is thought to function in ABA-induced stomatal closure.

However, the details of the active chemical species among ROS that functions in ABA signaling are not fully understood. Reactive oxygen species can be inter-transformable by several reactions, such as Fenton reaction, Harber-Weiss reaction, and SOD-catalyzed disproportionation. This may have hampered speciation of active chemical species among ROS in ABA signaling. Furthermore, spacio-temporal speciation of ROS function is not understood. In this study we focused on the specific H2O2-degrading enzyme CAT to dissect ROS species in ABA signaling.

Reactive oxygen species levels are controlled by antioxidant enzymes, such as catalases, peroxidases and superoxide dismutase in plants cooperating with ROS generating systems (Willekens et al., 1997; Corpas et al., 2001; Mittler, 2002; Apel and Hirt, 2004; Nyathi and Baker, 2006; Palma et al., 2009). The involvement of ascorbate peroxidase (APX) in stomatal function has been demonstrated but it was suggested that it was not involved in drought- or ABA-induced stomatal closure (Davletova et al., 2005). Catalase allows plant cells to remove H2O2 energy-efficiently because CAT decomposes H2O2 without consuming cellular reducing equivalents. Recently, it has been reported that Ca2+-dependent peroxisomal H2O2 catabolism is modulated by CAT in Arabidopsis guard cells (Costa et al., 2010).

The Arabidopsis genome contains three CAT genes, CAT1, CAT2 and CAT3, which are differentially expressed and can form up to six different isozymes (Frugoli et al., 1996). Catalase are highly specific to H2O2 over other chemical species of ROS, such as superoxide and hydroxyl radical. In this study, we examined the roles of constitutively accumulated H2O2 and ABA-inducible H2O2 in stomatal closure by examining cat mutants.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

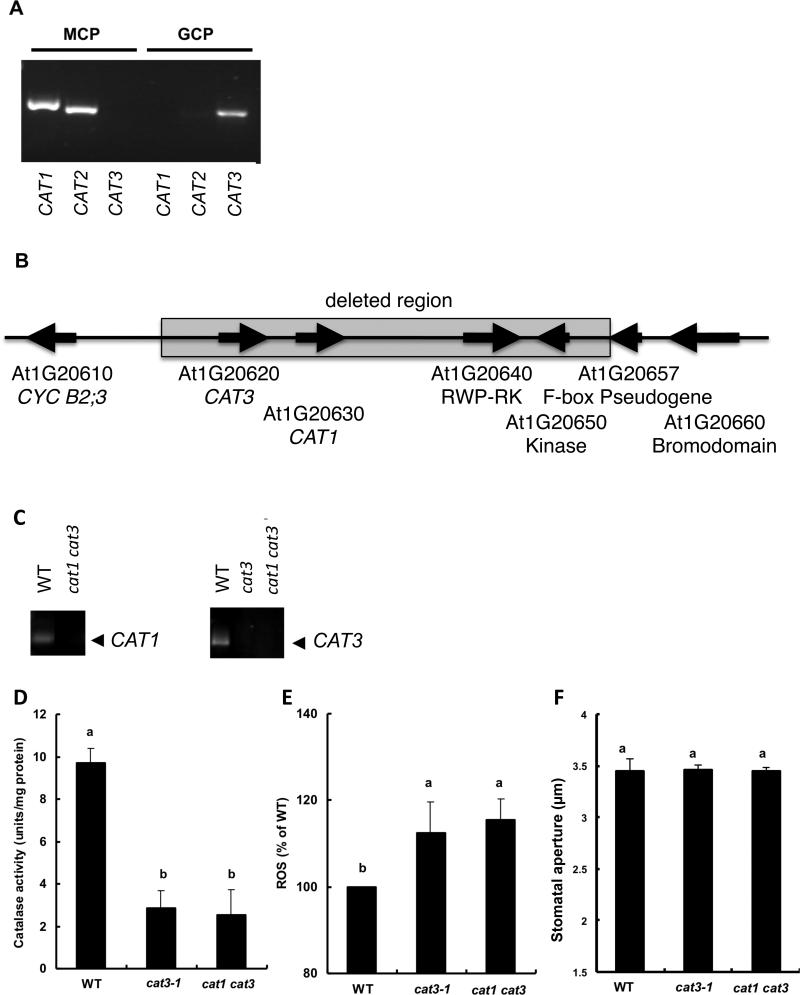

Arabidopsis thaliana wild type (Wassilewskija ecotype) and cat3-1, cat1 cat3 mutant lines were used. cat3-1 mutant possesses a T-DNA insertion in CAT3 locus of the Wassilewskija (Ws) accession and isolated by a genomic PCR screening of the pooled DNA from random T-DNA inserted populations provided by Ohio State University. The cat1 cat3 double mutant was iidentified in a poputation of Ws that had been subjected to fast neutron bonbardment. (J. Dangl, personal communication). To define the limits of the deletion, we developed PCR primers to amplify genes flanking the linked CAT1 (At1G20630) and CAT3 (At1G20620) loci. In addition to CAT1 and CAT3, the twi genes immediately downstream of CAT1, At1G20650 (encoding a RWP-RK family protein) and At1G20660 (encoding a protein serine threonine kinase) were missing, but the third gene, At1G20670 (encoding a putative bromo-domain containing protein), was retained. Similarly, the next gene upstream of CAT3, At1G20619 (Encoding CYCLIN B2;3), was also retained (Fig. 1B). We then designed primers to amplify across the deletion and determied the DNA sequence of the amplified fragment. The deletion eliminates 20,625 base pair (bp), from position 7141093, 2052 bp upstream of CAT3, to position 7161718, 1182 bp upstream (5’) of At1G220660 and 2574 bp downstream of At1G20670 (nucleotide numbers are based on the Col-0 reference genome).

Fig. 1.

Gene expression, catalase activities, ROS accumulation and stomatal aperture of wild type and cat mutants. A) Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis of CATALASE mRNAs; CAT1, CAT2 and CAT3 in guard cell protoplasts (GCP) and mesophyll cell protoplasts (MCP) of wild-type Arabidopsis (WS). B) Schematic representation of the deletion of the CAT3 and CAT1 loci in the fast neutron mutagenized cat1 cat3 mutant. The upper boxes indicate genomic organization of the reference sequence of the corresponding bacterial artificial chromosome clone sequence of the Arabidopsis (BAC clone#: F2D10). The bottom boxes indicate the genomic organization of the fast neutron mutagenized cat1 cat3 double deletion mutant. The grey box indicates the 20,625 bp deleted region in the mutant. Each arrow indicates open reading frame. In the mutant, two genes (RWP-RK and Kinase) are disrupted together with the tandem CAT1 and CAT3 genes. C) Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction analyses of CAT genes in cat3-1 and cat1cat3 mutants. Total RNA extracted from whole leaf was used for the template. D) Catalase activities of extracts from the low pH-treated epidermal fragments of wild type and, cat3-1 and cat1 cat3 mutants. E) Reactive oxygen species (ROS) production of guard cells in wild type, cat3-1 and cat1 cat3 mutants. The vertical scale represents the percentage of DCF fluorescent levels when fluorescent intensities of cat mutants were normalized to wild type value taken as 100% for each experiment. More than 50 guard cells were measured per experiment. F) Stomatal aperture of wild type and, cat3-1 and cat1 cat3 mutants in the absence of ABA. Each data was obtained from 60 stomatal aperture measurements. Figures having same letters do not differ significantly at the 5% level (one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test). Averages from three independent experiments are shown. Error bars represent standard deviation.

Plants were grown in soil in a plant growth chamber (LPH-350SP; Nihonika Co., Osaka, Japan) at 22°C under a 16-h-light/8-h-dark photoperiod at a photosynthetic photon flux density of 80 μmol m−2 s−1 and watered twice a week with Hyponex solution (0.1%).

Isolation of total RNA from whole leaf, guard cell protoplasts and mesophyll cell protoplasts

Total RNA from whole leaf was carried out with Trizole Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the producers manual. Guard cell protoplasts (GCP) and mesophyll cell protoplasts (MCP) were isolated by the method descrived by Kwak et al. (2002). Total RNA from GCP and MCP was isolated as same as from whole leaf.

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed as follows: Single strand complementary RNA was synthesized with MMLV reverse transcriptase according to the manufacturer's manual from total RNA isolated GCP, MCP and whole rosette leaves of 4-6-weak-old Arabidopsis plants. Polymerase chain reaction was carried out using gene-specific primer pairs as listed in supplemental Table 1 with a 30-cycles reaction steps: 94°C for 30 s, 53°C for 30 s and 72°C for 60 s. BIOTAQ DNA polymerase (Bioline, Bio-21040) was used.

Catalase activity measurements in whole leaves

For measurement of CAT activity leaves were homogenized in 5 volumes of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) supplemented with 0.5 mM EDTA, and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride with a mortar and a pestle. The homogenate was centrifuged at 15,000×g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was used for CAT activity measurement.

Catalase activity measurements in guard cells

For measurement of CAT activity in guard cells, live guard cells in epidermis were prepared as follows: Excised rosette leaves from 5-week-old plants were blended for 40 s with a Waring Commercial Blender and epidermis fragments were collected. The epidermis fragments were exposed to pH 4.5 for 90 min in 10 mM citrate buffer. This mild acid treatment was reported as a highly effective method of destroying all cells apart from the guard cells in epidermal preparation, in which guard cells apparently remained fully functional (Squire and Mandfield, 1972). The epidermis fragments were rinsed in distilled deionized water for 5 min. For ABA treatment, the epidermis fragment were then treated with 10 μM ABA or 0.02% ethanol (solvent control) for 30 min. The peels were collected and ground with a mortar and a pestle in liquid nitrogen to burst the guard cells. The homogenate was then mixed with 5 volumes of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) supplemented with 0.5 mM EDTA, and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The homogenate was centrifuged at 15,000×g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was used as the crude enzyme sample for CAT activity measurement.

Catalase activity was assayed according to the method of Aebi (1984). The reaction mixture consisted of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 0.5 mM EDTA, 20 mM H2O2 and 50 μL crude enzyme sample. The reaction was started by the addition of H2O2. The activity was calculated from the decline in absorbance at 240 nm for 60 s. The extinction coefficient was 39.4 M−1cm−1. Protein contents were measured as described by Bradford (1976) using bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Stomatal aperture measurements

Stomatal aperture was measured as described previously (Murata et al., 2001; Munemasa et al., 2007; Saito et al., 2008; Islam et al., 2009; 2010a; b). Excised rosette leaves from 4-6-week-old plants were floated on the medium containing 5 mM KCl, 50 μM CaCl2 and 10 mM MES-Tris (pH 6.15) for 2 h in the light (80 μmol m−2 s−1) to fully open stomata, followed by the addition of 10 μM ABA or solvent control (0.1% ethanol). Leaves incubated for 2 h were blended for 30 s with a Waring Commercial Blender and epidermal peels were collected. Width of stomatal aperture was immediately measured with a microscope after blending. Twenty stomatal apertures were measured on each preparation from a leaf. Number of biological repeats is designated in figure legends. For time course experiments, stomatal apertures were measured at each indicated time after ABA application.

Detection of ROS

Reactive oxygen species production was examined with 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCF-DA) as previously described (Pei et al., 2000; Murata et al., 2001; Munemasa et al., 2007; 2011; Saito et al., 2008; Islam et al., 2009; 2010a). Epidermal tissues were isolated from 4-6-week-old plants by blending with a Waring Commercial Blender and incubated for 2 h in the medium containing 5 mM KCl, 50 μM CaCl2, and 10 mM MES-Tris (pH 6.15) in the light. To load the dye to guard cells, epidermal tissue was incubated in the 50 μM H2DCF-DA-containing medium for 30 min. The excess dye was removed by washing with distilled deionized water on a piece of nylon mesh. Then, the dye-loaded tissues were treated either 10 μM ABA or 0.1% ethanol for 20 min. Fluorescent images of guard cells were captured in 8-bt gray scale with Adobe Photoshop program (Adobe Systems Inc.). The fluorescence intensity of the guard cell pair was determined using Image J software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA), the fluorescence intensity increase was expressed as percentage of the control.

Statistical Analysis

Significance of differences between mean values was assessed by Student's t-test or one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's test. Differences at p < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Catalase gene expression and identification of cat3 and cat1 cat3 mutants

Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using total RNA from guard cell protoplasts (GCP) and mesophyll cell protoplasts (MCP) as the template showed that only CAT3 was expressed in GCP (Fig. 1), while CAT1 and CAT2 were expressed in MCP (n=2). The expression of CAT1 was observed in GCP in only one of three experiments (Supplementary Fig. S1). Therefore we looked for cat1 and cat3 single mutants. Unfortunately, a cat1 single mutant was not available in the same ecotype background (Ws). Since CAT3 is reproducibly expressed in GCP in our study, we feel that demonstrating the cat1 cat3 double disruption mutant phenotype is satisfactory to discuss the role of H2O2 by altering the accumulation pattern in the cell. No apparent difference in general morphology was found among plants under the growth condition used in this study (data not shown), while RT-PCR analyses showed no transcripts in the mutants (Fig. 1C).

Catalase activities and ROS accumulation in the catalase mutants

To elucidate roles of endogenous H2O2 in ABA signaling of guard cells, we assessed stomata of CAT mutants, cat3-1 and cat1 cat3. First, we examined CAT activities of the cat3-1 and cat1 cat3 mutants. The cat3-1 mutation (p < 0.0005) and the cat1 cat3 mutation (p < 0.001) significantly reduced CAT activities in guard cell-enriched epidermis (see Materials and Methods) (Fig. 1D). These results indicate disruption of CAT in the guard cell of mutants.

Hydrogen peroxide accumulation was examined using the fluorescence dye, H2DCF-DA in the absence of ABA. Fluorescence intensity of guard cells of the mutants was brighter than that of wild type, indicating higher constitutive H2O2 accumulation level under non-stressed condition (Fig. 1E). This result was in a good agreement with lack of CAT activities in the mutant guard cells.

It has been reported that exogenously added H2O2 induces stomatal closure and endogenous ROS/H2O2 elevation is involved in ABA-induced stomatal closure. Thus, we examined stomatal aperture width of the mutants in the absence of ABA. Interestingly, the constitutively elevated H2O2 level in mutants’ guard cells did not resulted in reduced aperture size (Fig. 1F).

Effects of the catalase mutation on ABA-induced stomatal closure and ABA-induced ROS accumulation

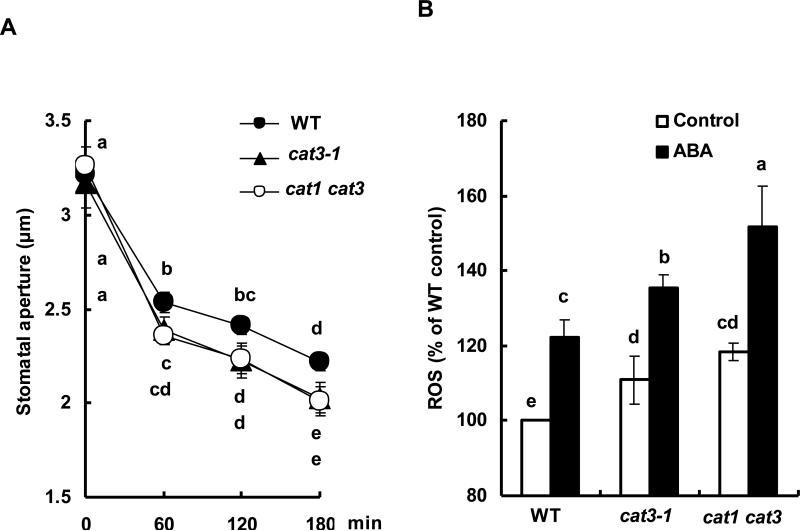

Abscisic acid-induced stomatal closure is associated with ROS production (Pei et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2001). Furthermore, molecular genetic evidences for the contribution of ROS in guard cell ABA signaling have been unambiguously presented (Murata et al., 2001; Mustilli et al., 2002; Kwak et al., 2003; Sirichandra et al., 2009). Thus, we examined ABA-induced stomatal closure and H2O2 production in the cat3-1 and cat1 cat3 mutants and wild type plants (Fig. 2). Application of ABA induced stomatal closure in a time dependent manner in all lines. At 180 min after ABA treatment, stomatal apertures were decreased by 31.0 % in wild type, 36.0 % in the cat3-1 mutant, and 38.4 % in the cat1 cat3 mutant (Fig. 2A). A statistic analysis suggested significant differences in stomatal apertures between these mutants and wild type (p < 0.03 for cat3-1; p < 0.02 for cat1 cat3).

Fig. 2.

Abscisic acid-induced stomatal closure and ROS accumulation of wild type and cat mutants. A) The time-course of stomatal closure in wild type (filled circle), cat3-1 (filled triangle) and cat1 cat3 (open circle) treated with 10 μM ABA. Each data was obtained from 60 stomatal aperture measurements. B) Reactive oxygen species production treated with 0.1% ethanol (as solvent control) and 10 μM ABA in guard cells of wild type and, cat3-1 and cat1 cat3 mutants. The vertical scale represents the percentage of DCF fluorescent levels when fluorescent intensity of wild type control value taken as 100%, and other values were expressed in relation to wild type control for each experiment. Each data was obtained from more than 50 guard cells. Figures having same letters do not differ significantly at the 5% level (one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test). Averages from three independent experiments are shown. Error bars represent standard deviation.

The H2O2 level in guard cells of the cat3-1 (p < 0.05) and cat1 cat3 (p < 0.0002) plants were higher than that in wild-type guard cells in the absence of ABA treatment (Fig. 2B), as essentially the same as seen in Fig. 1E. Consistent with previous reports (Pei et al., 2000; Murata et al., 2001; Bright et al., 2006; Munemasa et al., 2007; 2011; Islam et al., 2010a), ABA induced H2O2 production in wild type guard cells (p < 0.002) (Fig. 2B). In mutant guard cells, the H2O2 level was also elevated by ABA treatment (cat3-1, p < 0.006; cat1 cat3, p < 0.008) (Fig. 2B). Compared with wild type, the accumulation of H2O2 in guard cells was significantly higher in cat3-1 mutant guard cells (p < 0.02) and cat1 cat3 mutant guard cells (p < 0.02) (Fig. 2B).

To test the possibility that H2O2 accumulation by ABA in guard cell is mediated with inhibition of CAT activity with ABA in guard cells, CAT activity in guard cells-enriched epidermis after ABA treatment was examined. Essentially no difference in CAT activity in guard cells was observed with and without of ABA treatment for 30 min (Supplementary Fig. S2). Ten μM ABA was added to extracts from guard cell-enriched epidermis to examine direct effect of ABA on CAT activity. No significant difference in the activity was observed compared to the solvent control (data not shown).

These results suggest that stomatal closure is associated with inducible ROS production, rather than constitutive elevation of ROS level, and that downregulation of CAT is not involved in ABA-induced ROS elevation.

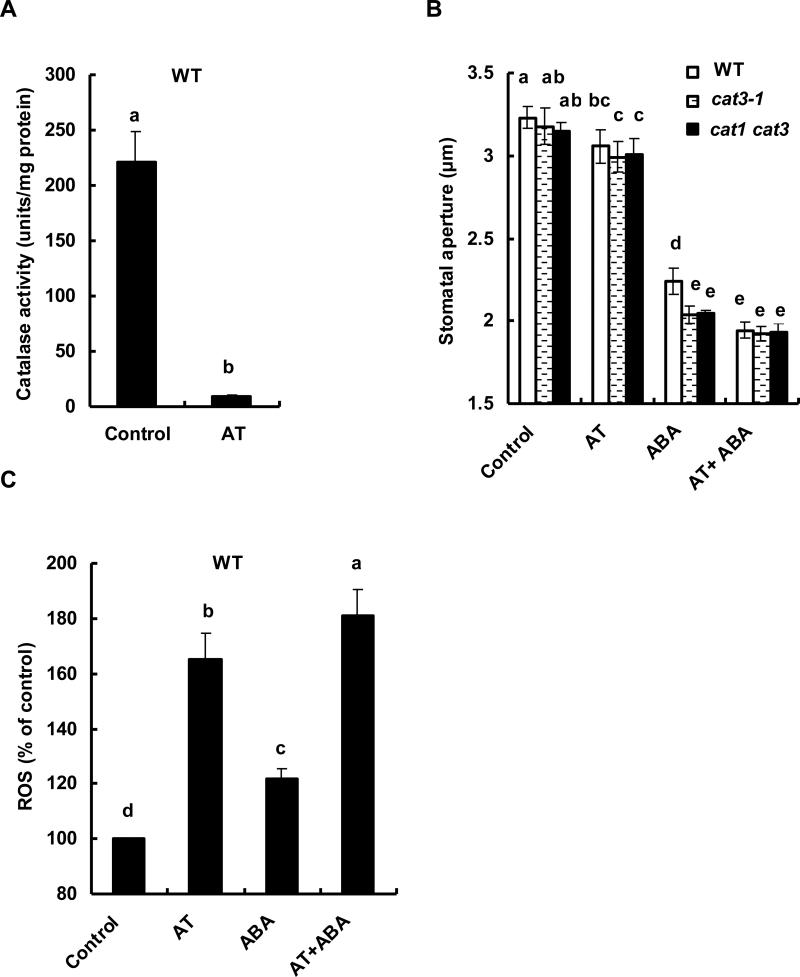

Effects of the catalase inhibitor, 3-aminotriazole (AT), on ABA-induced stomatal closure

To further examine the involvement of CATs in ABA-induced stomatal closure, we used the CAT inhibitor, AT. Application of AT reduced CAT activity in wild type plants to a negligible level in whole leaves (p < 0.0003) (Fig. 3A). The treatment with AT showed a very minor but statistically significant effect on stomatal aperture in the absence of ABA (Fig. 3B). Since cat mutants did not show any apparent effects on stomatal aperture in the absence of ABA (Fig. 1F), the effect of AT may be attributed to a sudden decrease of CAT activity by AT application, which is potentially associated with an artificial induction of a rapid H2O2 accumulation. According to the gene expression profiling results in Fig. 1A and Supplementary Fig. S1, cat1 cat3 mutant guard cell lack CAT activity. The observed minor, but significant effect of AT on stomatal apperture in the absence of ABA (Fig. 3B) in the mutants might be attributed to H2O2 supply from peripheral cells, such as mesophyll cells, which possess CAT2, to a minor adverse effect of AT, or to trace CAT2 expression, undetectable with RT-PCR, activity in guard cell.

Fig. 3.

Catalase activities, ABA-induced stomatal closure and ROS production in plants pre-treated with CAT inhibitor 3-aminotriazole (AT). A) Catalase activities of extracts from the whole leaves of wild type treated with 20 mM AT. Leaves were incubated for 2 h with 20 mM AT. B) Abscisic acid-induced stomatal closure in guard cells in the presence of AT. Rosette leaves of wild type (white bar), cat3-1 (dotted bar) and cat1 cat3 (black bar) were treated with 20 mM AT for 30 min, followed by 10 μM ABA treatment for 2 h. Each data was obtained from 60 stomatal aperture measurements. C) Abscisic acid-induced ROS production of guard cells in wild type in the presence of AT. Guard cells were treated with 20 mM AT for 30 min, followed by 10 μM ABA. The vertical scale represents the percentage of DCF fluorescent levels when fluorescent intensity of wild type control value taken as 100% and other values were expressed in relation to wild type control for each experiment. Each data was obtained from more than 50 guard cells. Figures having same letters do not differ significantly at the 5% level (one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test). Averages from three independent experiments are shown. Error bars represent standard deviation.

In wild type, ABA-induced stomatal closure was enhanced by AT (p < 0.005) and reached a similar level to cat mutants (Fig. 3B). The effect of AT was not significant in cat3-1 and cat1 cat3 mutants, suggesting the apparent effect of AT was due to the inhibition of CAT, rather than to other non-specific effects.

Treatment with AT significantly increased ROS accumulation in ABA-untreated (p < 0.0003) and -treated (p < 0.0002) wild type guard cells in accordance with cat mutants (Fig. 3C).

Taken together with previous findings, these data suggest that ABA-induced production of ROS is not simple ROS elevation, but instead represents temporal-spatial specific ROS signature that plays a role in guard cell ABA signaling (Fig. 4 and Discussion). This study examining disruption mutants or inhibition of the H2O2 specific degrading enzyme, CAT, suggests that among ROS at least intracellular H2O2 have some roles in ABA signaling.

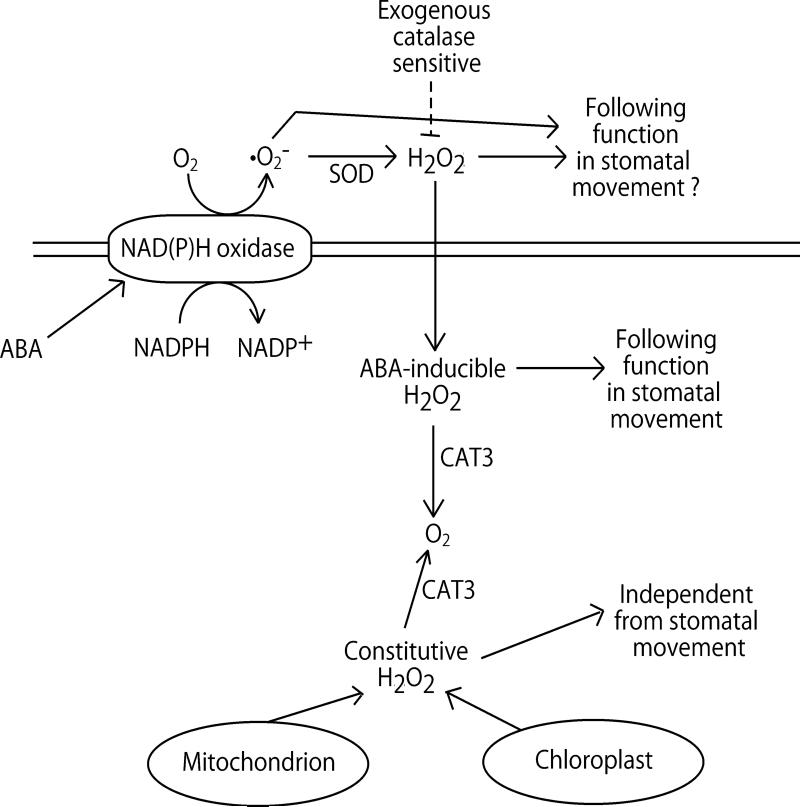

Fig. 4.

A proposed model showing the roles of constitutive- and ABA-inducible cytosolic H2O2 accumulation in ABA signaling in guard cells.

Arrows indicate positive regulation, and open blocks indicate negative regulation. In the absence of ABA, constitutive H2O2 is generated from mitochondria and chloroplast, which is independent from stomatal movement. In a wild type guard cell, CAT3 decomposes the constitutive H2O2 to O2. In the presence of ABA, ABA activates NAD(P)H oxidases in the plasma membrane that produces superoxide anion (•O −2) by consuming the reduction potential of NADPH in the cell. Superoxide dismutases in the apoplastic space convert •O −2 to H2O2, which is sensitive to exogenously added CATs. The extracellularly converted H2O2 migrates into cytosolic space across the plasma membrane, raises cytosolic H2O2 concentration (ABA-inducible H2O2) and functions for following stomatal movement signaling in the cell. The ABA-inducible H2O2 are also decomposed into O2 by CAT3 for downregulating the signal. Thus, disruption of CAT3 causes a slight increase of ABA sensitivity of stomata. Note that this model does not necessarily deny functions of extracellular •O −2 and H2O2 in stomatal movements. At present, at least two targets of H2O2 are postulated, i.e. ABI2 and ICa channels (see text). However, differential roles of extracellular and cytosolic ABA-inducible H2O2 to the downstream signal components have not been clarified, yet.

Discussion

Abscisic acid induces stomatal closure along with ROS accumulation in guard cells, which is an essential ABA signaling component in guard cells (Pei et al., 2000; Kwak et al., 2003). However, temporal and chemical speciation of ROS in guard cell ABA signaling has not been examined. In the present study, in order to assess the role of H2O2, we employed reverse genetic and a pharmacological approaches using Arabidopsis thaliana. We showed that CAT3 is the predominantly expressed CAT in guard cells, while expression of CAT1 can be observed occasionally. Catalase mutants, cat3-1 and cat1 cat3 demonstrated no corresponding transcript and reduced CAT activity. The CAT inhibitor, 3-aminotriazole (AT), also reduced CAT activity. Decreasing CAT activity by mutations and the inhibitor resulted in the constitutive H2O2 accumulation in Arabidopsis guard cells. However, the constitutive ROS accumulation did not affect stomatal aperture in the absence of ABA. The CAT mutations and the CAT inhibitor enhanced ABA-induced stomatal closure and also promoted ABA-induced ROS production. In addition, ABA induced stomatal closure equivalently in wild type and both mutants in the presence of AT at the concentration, which completely inhibited CAT activities. The genetic and pharmacological approaches in this study suggest that inducible ROS production, but not constitutive ROS accumulation, are closely involved in stomatal closure. This may imply that temporal-spatial specific, presumably also chemical species specific, ROS production signatures play a critical role in the signal discrimination in plant cell signaling (Fig. 4).

Arabidopsis glutathione peroxidase (GPX) isoenzymes, AtGPX1, −2, −3, −5 and −6, function to reduce H2O2 and hydroperoxide using thioredoxin but not glutathione as an electron donor (Iqbal et al., 2006; Miao et al., 2006). Glutathione peroxidase function in detoxifying organic hydroperoxides as well as H2O2, and may functionally different from CAT in guard cells . AtGPX3 play dual roles in H2O2 homeostasis via the 2C-type protein phosphatase ABA INSENSITIVE2 (ABI2), acting as a general scavenger and specifically relaying the H2O2 signal as an oxidative signal transducer in ABA signaling (Miao et al., 2006). Interestingly, plant GPX is shown not to use glutathione as the substrate, instead it uses NADPH (Iqbal et al., 2006). On the other hand, involvement of glutathione in ABA signaling is suggested by a glutathione synthesis-deficient mutant (Jahan et al., 2008). ASCORBATE PEROXIDASE 1 (APX1) is involved in light-dark cycle transition response of stomata, but not in ABA response (Pnueli et al. 2003). ASCORBATE PEROXIDASE 1 localizes in cytosol and mainly decomposes cytosolic super oxide. This difference in substrate preferance may be one of the reasons for the phenotypic difference between CAT3 and APX1. Taken together, it is reasonable that APX1 has a distinct function in guard cell redox signaling from CAT.

Calcium-permeable channels activated by ROS is shown to function in the ABA signaling network in Arabidopsis guard cells (Pei et al., 2000; Murata et al., 2001; Mori et al., 2006). Increases in cytosolic calcium are triggered by ROS production during ABA signaling (Kwak et al., 2003), suggesting a tight link of ROS generation and Ca2+ oscillation. Similar to H2O2, constitutive Ca2+ elevations (Ca2+ plateau) in guard cells does not induce stomatal closure contrasting with Ca2+ oscillations (Young et al., 2006; Siegel et al., 2009). From these facts one can reasonably speculate that spatio-temporal specific ROS elevation pattern function together in a harmonized way with Ca2+ oscillation in mediating ABA-induced stomatal closing.

It was shown that NAD(P)H oxidase generates superoxide anion extracellularly (Kwak et al. 2003). Extracellular application of membrane impermeable CAT inhibits ABA-induced stomatal closure (Zhang et al., 2001; Munemasa et al., 2007). Our results, which showed partial enhancement of stomatal closure in CAT disruption or inhibition, suggests, at least, partial involvement of intracellular H2O2 in the process. Taken together these observations, we propose a model for ROS function in ABA signaling in guard cell (Fig. 4). Furthermore, the present study provides evidence that transient ROS production rather than constitutive ROS accumulation modulated by CAT1 and CAT3 are important for stomatal closure in Arabidopsis guard cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists and Grants for Scientific Research on Priority Areas from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan to Y.M., Nissan Science Foundation to I.C.M., and early stages of this research by I.C.M. were supported by the NIH (GM060396-ES010337) to J.I.S.

Abbreviations

- ABA

abscisic acid

- APX

ascorbate peroxidase

- AT

3-aminotriazole

- CAT

catalase

- GCP

guard cell protoplast

- GPX

glutathione peroxidase

- H2DCF-DA

2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate

- ICa channel

plasma membrane Ca2+-permeable channel

- MCP

mesophyll cell protoplast

- MES

2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

References

- Aebi H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1984;105:121–6. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(84)05016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apel K, Hirt H. Reactive oxygen species: metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2004;55:373–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–54. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bright J, Desikan R, Hancock JT, Weir IS, Neill SJ. ABA-induced NO generation and stomatal closure in Arabidopsis are dependent on H2O2 synthesis. Plant J. 2006;45:113–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corpas FJ, Barroso JB, del Río LA. Peroxisomes as a source of reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide signal molecules in plant cells. Trends Plant Sci. 2001;6:145–50. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(01)01898-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa A, Drago I, Behera S, Zottini M, Pizzo P, Schroeder JI, et al. H2O2 in plant peroxisomes: an in vivo analysis uncovers a Ca2+-dependent scavenging system. Plant J. 2010;62:760–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davletova S, Rizhsky L, Liang H, Shengqiang Z, Oliver DJ, Coutu J, et al. Cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase 1 is a central component of the reactive oxygen gene network of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2005;17:268–81. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.026971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frugoli JA, Zhong HH, Nuccio ML, McCourt P, McPeek MA, Thomas TL, et al. Catalase is encoded by a multigene family in Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. Plant Physiol. 1996;112:327–36. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.1.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington AM, Woodward FJ. The role of stomata in sensing and driving environmental change. Nature. 2003;424:901–8. doi: 10.1038/nature01843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal A, Yabuta Y, Takeda T, Nakano Y, Shigeoka S. Hydroperoxide reduction by thioredoxin-specific glutathione peroxidase isoenzymes of Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS J. 2006;273:5589–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving HR, Gehring CA, Parish RW. Changes in cytosolic pH and calcium of guard cells precede stomatal movements. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1790–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam MM, Tani C, Watanabe-Sugimoto M, Uraji M, Jahan MS, Masuda C, et al. Myrosinases, TGG1 and TGG2, redundantly function in ABA and MeJA signaling in Arabidopsis guard cells. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009;50:1171–5. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam MM, Munemasa S, Hossain MA, Nakamura Y, Mori IC, Murata Y. Roles of AtTPC1, vacuolar two pore channel 1, in Arabidopsis stomatal closure. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010a;51:302–11. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam MM, Hossain MA, Jannat R, Munemasa S, Nakamura Y, Mori IC, et al. Cytosolic alkalization and cytosolic calcium oscillation in Arabidopsis guard cells response to ABA and MeJA. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010b;51:1721–30. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janan MS, Ogawa K, Nakamura Y, Shimoishi Y, Mori IC, Murata Y. Deficient glutathione in guard cells facilitates abscisic acid-induced stomatal closure but does not affect light-induced stomatal opening. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2008;10:2795–8. doi: 10.1271/bbb.80407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak JM, Moon J-H, Murata Y, Kuchitsu K, Leonhardt N, DeLong A, Schroeder JI. Disruption of a guard cell-expressed protein phosphatase 2A regulatory subunit, RCN1, confers abscisic acid insensitivity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2002;14:2849–61. doi: 10.1105/tpc.003335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak JM, Mori IC, Pei ZM, Leonhardt N, Torres MA, Dangl JL, et al. NADPH oxidase AtrbohD and AtrbohF genes function in ROS-dependent ABA signaling in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 2003;22:2623–33. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Choi H, Suh S, Doo I-S, Oh K-Y, Choi EJ, Taylor ATS, et al. Oligogalacturonic acid and chitosan reduce stomatal aperture by inducing the evolution of reactive oxygen species from guard cells of tomato and Commelina communis. Plant Physiol. 1999;121:147–52. doi: 10.1104/pp.121.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao Y, Lv D, Wang P, Wang X-C, Chen J, Miao C, Song C-P. An Arabidopsis glutathione peroxidase functions as both a redox transducer and a scavenger in abscisic acid and drought stress responses. Plant Cell. 2006;18:2749–66. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.044230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R. Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7:405–10. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(02)02312-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori IC, Murata Y, Yang Y, Munemasa S, Wang Y-F, Andreoli S, et al. CDPKs CPK6 and CPK3 function in ABA regulation of guard cell S-type anion- and Ca2+-permeable channels and stomatal closure. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:1749–62. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munemasa S, Oda K, Watanabe-Sugimoto M, Nakamura Y, Shimoishi Y, Murata Y. The coronatine-insentitive 1 mutation reveals the hormonal signaling interaction between abscisic acid and methyl jasmonate in Arabidopsis guard cells. Specific impairment of ion channel activation and second messenger production. Plant Physiol. 2007;143:1398–407. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.091298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munemasa S, Hossain MA, Nakamura Y, Mori IC, Murata Y. The Arabidopsis calcium-dependent protein kinase, CPK6, functions as a positive regulator of methyl jasmonate signaling in guard cells. Plant Physiol. 2011;155:553–61. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.162750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata Y, Pei ZM, Mori IC, Schroeder JI. Abscisic acid activation of plasma membrane Ca2+ channels in guard cells requires cytosolic NAD(P)H and is differentially disrupted upstream and downstream of reactive oxygen species production in abi1-1 and abi2-1 protein phosphatase 2C mutants. Plant Cell. 2001;13:2513–23. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustilli A-C, Merlot S, Vavasseur A, Fenzi F, Giraudat J. Arabidopsis OST1 protein kinase mediates the regulation of stomatal aperture by abscisic acid and acts upstream of reactive oxygen species production. Plant Cell. 2002;14:3089–99. doi: 10.1105/tpc.007906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyathi Y, Baker A. Plant peroxisomes as a source of signalling molecules. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:1478–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palma JM, Corpas FJ, del Río LA. Proteome of plant peroxisomes: new perspectives on the role of these organelles in cell biology. Proteomics. 2009;9:2301–12. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei ZM, Murata Y, Benning G, Thomine S, Klűsener B, Allen GJ, et al. Calcium channels activated by hydrogen peroxide mediate abscisic acid signalling in guard cells. Nature. 2000;406:731–4. doi: 10.1038/35021067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pnueli L, Liang H, Rozenberg M, Mittler R. Growth suppression, altered stomatal responses, and augmented induction of heat shock proteins in cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase (Apx1)-deficient Arabidopsis plants. Plant J. 2003;34:187–203. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito N, Munemasa S, Nakamura Y, Shimoishi Y, Mori IC, Murata Y. Roles of RCN1, regulatory a subunit of protein phosphatase 2A, in methyl jasmonate signaling and signal crosstalk between methyl jasmonate and abscisic acid. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008;49:1396–401. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JI, Allen GJ, Hugouvieux V, Kwak JM, Waner D. Guard cell signal transduction. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 2001;52:627–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.52.1.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RS, Xue S, Murata Y, Yang Y, Nishimura N, Wang A, Schroeder JI. Calcium elevation-dependent and attenuated resting calcium-dependent abscisic acid induction of stomatal closure and abscisic acid-induced enhancement of calcium sensitivities of S-type anion and inward-rectifying K+ channels in Arabidopsis guard cells. Plant J. 2009;59:207–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirichandra C, Gu D, Hu H-C, Davanture M, Lee S, Djaoui M, et al. Phosphorylation of the Arabidopsis AtrbohF NADPH oxidase by OST1 protein kinase. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:2982–6. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suhita D, Agepati S, Raghavendra AS, Kwak JM, Vavasseur A. Cytoplasmic alkalization precedes reactive oxygen species production during methyl jasmonate- and abscisic acid-induced stomatal closure. Plant Physiol. 2004;134:1536–45. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.032250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire GR, Mansfield TA. A simple method of isolating stomata on detached epidermis by low pH treatment: observations of the importance of the subsidiary cells. New Phytol. 1972;71:1033–43. [Google Scholar]

- Willekens H, Chamnongpol S, Davey M, Schraudner M, Langebartels Montagu MV, et al. Catalase is a sink for H2O2 and is indispensable for stress defence in C3 plants. EMBO J. 1997;16:4806–16. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.16.4806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JJ, Mehta S, Israelsson M, Godoski J, Grill E, Schroeder JI. CO2 signaling in guard cells: Calcium sensitivity response modulation, a Ca2+-independent phase, and CO2 insensitivity of the gca2 mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7506–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602225103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Zhang L, Dong F, Gao J, Galbraith DW, Song CP. Hydrogen peroxide is involved in abscisic acid-induced stomatal closure in Vicia faba. Plant Physiol. 2001;126:1438–48. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.4.1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.