Abstract

Emerging viral infections can be identified by using a viral metagenomics approach for clinical human material. Diarrhea samples of patients with unexplained gastroenteritis from the Netherlands were analyzed by using viral metagenomics. Novel circular DNA viruses, bufaviruses, and genogroup III picobirnaviruses were identified. These data expand our knowledge of the human virome.

Keywords: diarrhea, idiopathic human diarrhea cases, viruses, circular DNA virus, circovirus, picobirnavirus, bufavirus, enteric infections, random amplification, next-generation sequencing, the Netherlands

The list of emerging viral pathogens is ever-changing. The recognition that an increasing number of diseases that were once unexplained are caused by infectious agents has increased substantially in recent years because of breakthroughs in the metagenomics field (1). The human gut is a reservoir of a wide variety of microorganisms. In industrialized countries, diarrheal diseases are a major cause of illness among persons of all age groups, and most gastroenteritis cases are caused by viruses (2). However, despite extensive diagnostic analysis, the cause of many diarrhea cases remains unresolved.

We analyzed stool samples from 27 patients in the Netherlands who had acute gastroenteritis of unknown etiology for (un)known viruses by using a metagenomics approach. Samples were obtained from patients with sporadic cases and from patients involved in outbreaks of diarrhea and vomiting, for which most common causes of gastroenteritis had been ruled out.

The Study

Thirteen diarrhea stool samples were obtained from patients with gastroenteritis during 2005–2009 whose infection was not identified despite extensive testing at the reference laboratory for viral gastroenteritis at the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, Bilthoven, the Netherlands (3). In addition, we obtained 14 stool samples from patients hospitalized during 7 gastroenteritis outbreaks in 2008 and 2009 (Table) (4). All procedures were performed in compliance with relevant laws (Medical Ethical Committee, University Medical Center Utrecht approval no. 07–310). Samples were analyzed by using a viral metagenomics approach and 169,305 trimmed reads were characterized according to BLAST searches as described (5).

Table. Detection of mammalian viral sequences in 27 patients with diarrhea by using viral metagenomics, the Netherlands, 2005–2009*.

| Patient no. | Age, y | Diarrhea type or source | Year of sampling | No. trimmed reads | No. trimmed viral reads | Virus species (no. reads; % nucleotide identity) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VS6600008 | 7 | Sporadic | 2008 | 7,851 | 271 | Human picobirnavirus (221; NA) |

| VS6600009 | 25 | Sporadic | 2008 | 8,079 | 10 | Bufavirus 1 (7; 67–94) |

| VS6600010 | 87 | Sporadic | 2008 | 3,237 | 1 | NA |

| VS6600011 | 66 | Sporadic | 2008 | 3,866 | 6 | NA |

| VS6600013 | 48 | Sporadic | 2008 | 2,849 | 19 | NA |

| VS6600014 | 40 | Sporadic | 2008 | 8,079 | 143 | Aichivirus (139; 98) |

| Human herpesvirus 4 (1; 91) | ||||||

| Anellovirus (3; 61–85) | ||||||

| VS6600015 | 84 | Sporadic | 2008 | 11,197 | 9 | Anellovirus (6; 81–97) |

| VS6600016 | 37 | Sporadic | 2008 | 7,333 | 1 | NA |

| VS6600017 | 62 | Sporadic | 2008 | 546 | 0 | NA |

| VS6600018 | <1 | Sporadic | 2008 | 3,936 | 4 | NA |

| VS6600019 | 30 | Sporadic | 2008 | 9,590 | 18 | NA |

| VS6600020 | 57 | Sporadic | 2009 | 10,389 | 37 | Porcine picobirnavirus (6; 57–80) |

| VS6600021 | 52 | Sporadic | 2009 | 4,587 | 0 | NA |

| VS6600022 | 27 | OB2005111 | 2005 | 4,877 | 113 | Fur seal–associated circular DNA virus (98; NA); |

| VS6600023 | 47 | OB2005111 | 2005 | 7,423 | 117 | Human picobirnavirus (91; 82–87) |

| VS6600024 | 47 | OB2005115 | 2005 | 6,852 | 338 | NA |

| VS6600025 | 6 | OB2005115 | 2005 | 8,949 | 34 | Human picobirnavirus (23; 75–84) |

| VS6600026 | 12 | OB2006097 | 2006 | 6,879 | 52 | Otarine picobirnavirus (42; 70–88) |

| VS6600027 | 13 | OB2006097 | 2006 | 9,481 | 32 | NA |

| VS6600028 | 52 | OB2008169 | 2008 | 5,222 | 74 | NA |

| VS6600029 | 32 | OB2008169 | 2008 | 1,568 | 4 | Human picobirnavirus (3; 86) |

| VS6600030 | 26 | OB2008190 | 2008 | 7,377 | 57 | NA |

| VS6600031 | 10 | OB2008190 | 2008 | 4,541 | 14 | NA |

| VS6600032 | 90 | OB2008217 | 2008 | 4,185 | 13 | Fur seal–associated circular DNA virus (4; NA) |

| VS6600033 | 97 | OB2008217 | 2008 | 3,299 | 11 | NA |

| VS6600034 | 89 | OB2009024 | 2009 | 14,797 | 168 | Human picobirnavirus (115;68%–77%) |

| VS6600035 | 91 | OB2009024 | 2009 | 2,256 | 8 | Human picobirnavirus (3; 70%) |

*Classification of sequences was based on taxonomic origin of the best-hit sequence and was performed by using MEGAN version 4.40.4 (http://ab.inf.uni-tuebingen.de/software/megan/) with E cutoff values of 0.001 and 10–10 for BLASTn and BLASTx searches (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), respectively (5,6). NA, not applicable; OB, outbreak

Mammalian viral sequences were detected in stool samples from 13 of 27 patients (Table). Anelloviruses that displayed ≈60%–91% nt identities with known anelloviruses were obtained from patients VS6600014 and VS6600015. Because anelloviruses are endemic worldwide, present in many different tissues, and were found in ≈0.05% of the total number of reads, we did not consider it likely that they played a causative role in the gastroenteritis of the patients. Patient VS6600014 was infected with human herpesvirus 4 and an aichivirus; the aichivirus is associated with diarrhea (6) and constituted ≈1.7% of the total number of reads. A partial viral protein 2 nucleotide sequence (336 bp covered by 7 reads; KJ206565) of a bufavirus was detected in patient VS6600009. This sequence, which aligned with corresponding sequences of a recently described bufavirus in children with diarrhea in Burkina Faso (7), was phylogenetically analyzed and showed 67%–73% nt identity (Technical Appendix Figure 1). Attempts to obtain more sequences from this virus were unsuccessful, and results for real-time PCRs specific for a nonstructural protein 1 gene remained negative, probably because of low virus titers in the sample. New picobirnaviruses and circular DNA viruses were identified and further characterized.

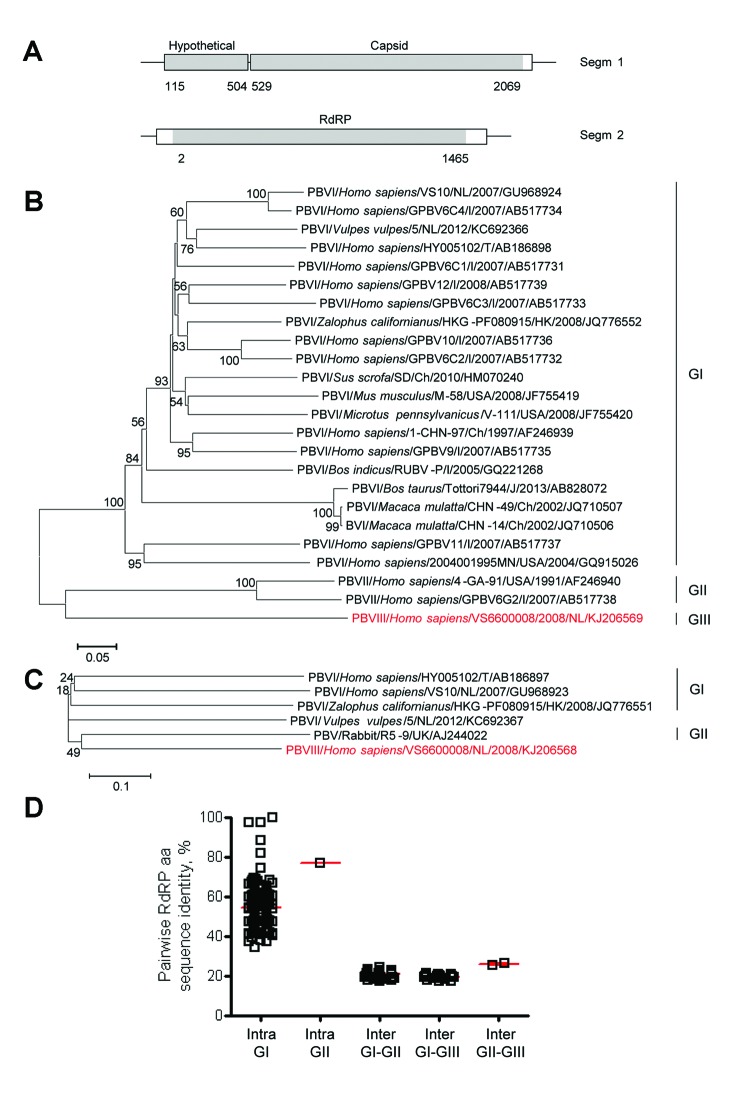

Figure 1.

Genome organization and phylogenetic analysis of human picobirnavirus (PBV) VS6600008 isolated in the Netherlands, 2005–2009. A) Putative schematic genome organization of human PBV VS6600008. Locations of major open reading frames are indicated in white and sequences obtained by next-generation sequencing are indicated in gray. Segm, segment; RdRP, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. B) Phylogenetic neighbor-joining tree with p-distances and 1,000 bootstrap replicates of amino acid sequences of partial RdRP genes corresponding to aa 80–377 of reference PBV strain HY005102; AB186898, PBV VS6600008, and representative PBVs. Alignments were created by using ClustalX 2.0 (http://www.clustal.org/). Viruses are shown as virus/host species/strain/country/year/GenBank accession no. (if available). Virus isolated in this study is indicated in red. Genogroups are indicated on the right. Scale bar indicates amino acid substitutions per site. NL, the Netherlands; I, India; T, Thailand; Ch, China; USA, United States; UK, United Kingdom; J, Japan; HK, Hong Kong. C) Phylogenetic neighbor-joining tree with p-distances and 1,000 bootstrap replicates of the amino acid sequences of the partial capsid genes corresponding to aa 1–220 of reference PBV strain HY005102; AB186897, PBV VS6600008, and representative PBVs. Alignments were created by using ClustalX 2.0. Virus isolated in this study is indicated in red. Genogroups are indicated on the right. Scale bar indicates amino acid substitutions per site. D) Pairwise intragenogroup (Intra) and intergenogroup (Inter) amino acid sequence identities determined by using Bioedit 7.0.9.0 (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/bioedit/bioedit.html) between the partial RdRP sequences (corresponding to amino acids 80–377 of reference PBV strain HY005102; AB186898). Each square represents pairwise RdRP amino acid sequence identity between viruses in panel B. Red bars indicate mean and SEM.

Picobirnaviruses are highly variable, double-stranded RNA viruses with a bisegmented genome. Segment 1 (2.2–2.7 kb) encodes the capsid (Cap) protein and potential hypothetical protein(s), and segment 2 (1.2–1.9 kb) encodes the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP). On the basis of sequence diversity in RdRP, picobirnaviruses are classified into 2 genogroups (8). They have been detected in humans and a wide range of animals (8) and might be opportunistic enteric pathogens (8,9). Stool samples from 7 patients had virus sequences with relatively high homology with known group I picobirnaviruses (Table; Technical Appendix Figure 2). A near-complete highly divergent picobirnavirus genome was obtained by 454-sequencing (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) of samples from patient VS6600008 (GenBank accession nos. KJ206568 and KJ206569). The genome organization is highly similar to that of picobirnaviruses (Figure 1, panel A).

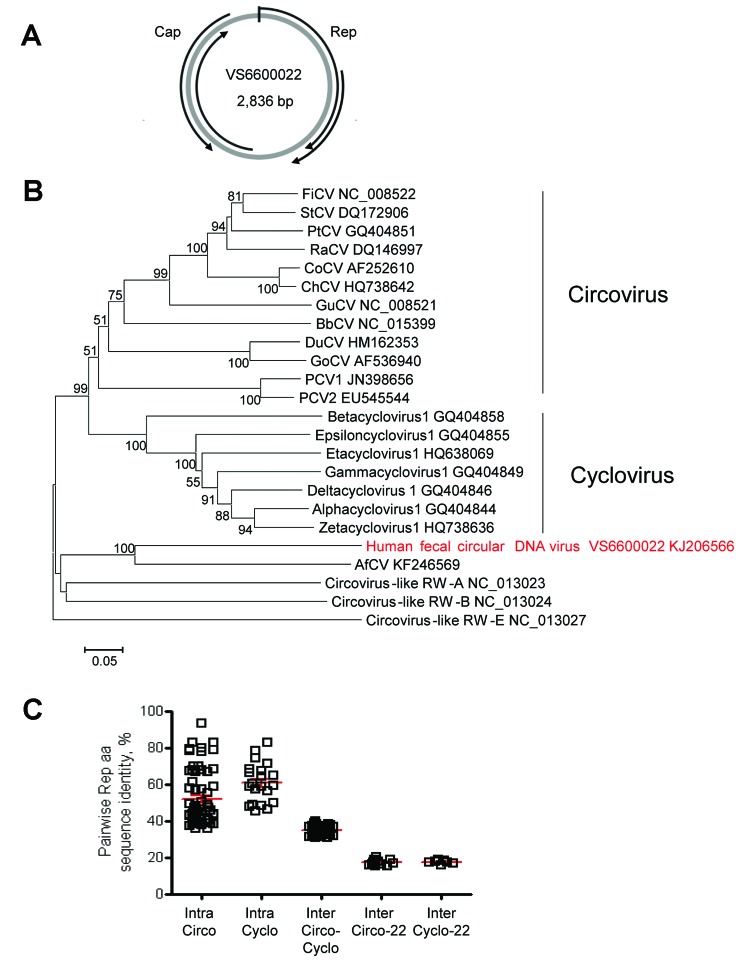

Figure 2.

Genome organization and phylogenetic analysis of human fecal circular DNA virus VS6600022, the Netherlands, 2005–2009. A) Putative schematic genome organization. Arrows indicate major open reading frames. Cap, capsid; Rep, rolling circle replication initiator protein. B) Phylogenetic neighbor-joining tree with p-distances and 1,000 bootstrap replicates created with MEGA5 of amino acid sequences of the Rep genes of human fecal circular DNA virus VS6600022 and representative circoviruses that were aligned by using ClustalX2.0 (http://www.clustal.org/). Virus isolated in this study is indicated in red. Scale bar indicates amino acid substitutions per site. FiCV, finch circovirus; StCV, starling circovirus; PtCV, Pan troglodytes circovirus; RaCV, raven circovirus; CoCV, columbid circovirus; ChCV, chicken circovirus; GuCV, gull circovirus; PCV, porcine circovirus; BbCV; Barbus barbus circovirus; DuCV, duck circovirus; GoCV, goose circovirus; AfCV, Arctocephalus forsteri circovirus. C) Pairwise intraspecies (Intra) and interspecies (Inter) amino acid sequence identities determined by using Bioedit 7.0.9.0 (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/bioedit/bioedit.html) between the Rep protein sequences of VS6600022 and representative species in the genera Circovirus (Circo) and Cyclovirus (Cyclo). Each square represents the pairwise RdRP amino acid sequence identity between the viruses in panel B. Red bars indicate mean and SEM.

The pairwise amino acid identity of the partial RdRP of the human picobirnavirus PBVIII/Homo sapiens/VS6600008/2008/NL/KJ206569 and that of other representative picobirnaviruses was determined (Figure 1, panels B–D). The intragenogroup amino acid identity between picobirnavirus species ranged from 34.5% to 99.7% in RdRP (Figure 1, panel D). The intergenogroup amino acid identity between genogroup I and II picobirnaviruses ranged from 17.5% to 24.1% (Figure 1, panel D). PBVIII/Homo sapiens/VS6600008/2008/NL/KJ206569 showed low amino acid identity (19.4%–26.1%) in the intergenogroup range with genogroup I and II picobirnaviruses (Figure 1, panels B–D), which justifies the placement of this virus in a new genogroup III. Only a few Cap sequences of picobirnaviruses are available; these sequences show <25% amino acid identity to each other, and a clear genogroup division cannot be distinguished (Figure 1, panel C). A picobirnavirus VS6600008-specific real time PCR was performed on the total sample set with primers VS791 (5′-CGATGGATCTTTATGTTCCCG-3′), VS792 (5′-GTAGTTGAAATGTTGATCCATTT-3′), and VS793 (5′-CAAACTTTCCAGCAACCGCTT-3′) labeled with 6-carboxy-fluorescein and 6-carboxy-tetramethyl-rhodamine as described (10). Only the sample from patient VS6600008 had a positive result (cycle threshold 25.1).

Novel circular small DNA viruses containing a rolling circle replication initiator protein gene (Rep) have been discovered at increasing rates from animals and humans (11). These viruses are extremely diverse and encode at least Cap protein and Rep protein located in opposite genomic orientations and separated by 2 intergenic regions. On the basis of genome organization and amino acid sequence identity of Rep proteins, novel circular DNA viruses seem most closely related to others viruses of the family Circoviridae (11). A complete circular virus genome (2,836 nt) was obtained from patient VS6600022 by rolling circle amplification and 454-sequencing (KJ206566) (Table). The genome showed an ambisense organization and 2 major inversely arranged open reading frames encoding the Rep and Cap proteins (Figure 2, panel A). A stem-loop structure with the conserved circovirus nonanucleotide motif (5′-TAGTATTAC-3′) was found in the 5′-intergenic region. However, genome size, presence of 2 putative other open reading frames with no sequence homology to any sequence in GenBank, and deviations in WWDGY, DDFYGW, DRYP, FTLNN, TPHLQG, and CSK motifs in the Rep protein, which are ordinarily conserved, indicate that this virus is different from characteristic circoviruses.

Pairwise amino acid identity between the Rep protein of virus VS6600022 and other representative circovirus-like viruses was determined, and a phylogenetic tree was generated (Figure 2, panel B and C). The Rep protein of VS6600022 showed <20% aa identity with all circoviruses and was most closely related to a circular DNA virus from feces of a New Zealand fur seal (33% identity) (12). A similar phylogenetic relationship was observed in the Cap protein.

A partial viral genome was identified in patient VS6600032 (KJ206567), and the partial Rep protein of this virus was most closely related to that of VS6600022 (45% aa identity). The cellular host for the novel circular DNA viruses from patients with diarrhea cannot be deduced, and although replication in human cells is conceivable, these viruses might also originate from the diet of the patient. A VS6600022-specific real-time PCR was performed on the total sample set with primers VS794 (5′-ATCGAAGRWCAYCCTGGAAC-3′), VS795 (5′-TKRCACAGGGTACTTGTATC-3′), and VS796 (5′-ACTGTCCTCGTGTACATTGGCAA-3′) labeled with 6-carboxy-fluorescein and 6-carboxy-tetramethyl-rhodamine as described (13). Only the sample from patient VS6600022 had a positive result (cycle threshold 34.8).

Conclusions

Viral metagenomics of patients samples from unexplained diarrhea cases in Netherlands identified viruses of the families Anelloviridae, Picobirnaviridae, Herpesviridae, and Picornaviridae, some of which might be associated with development of gastroenteritis (6–8,14,15). The discoveries of a new genogroup III picobirnavirus and circular DNA virus from human diarrhea samples expands our knowledge of virus diversity in the human gut. We also showed that recently identified bufaviruses are present beyond the boundaries of Africa (7). Mammalian viral sequences were detected in patients with sporadic gastroenteritis and in persons during outbreaks in relatively equal proportions. In addition, specific viral infections were not identified in samples from the same gastroenteritis outbreaks. On the basis of these findings, we cannot conclude or rule out that these viruses cause disease. Further studies are needed to clarify the epidemiology and possible pathogenicity of these viruses in humans.

Phylogenetic analysis of human bufavirus VS6600009 and a subset of human picobirnaviruses with relatively high homology with known picobirnaviruses, the Netherlands.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by the European Community Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007–2013) under the project “European Management Platform for Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Disease Entities” European Commission agreement no. 223498, the Virgo Consortium, and the Netherlands Organization for Health research and Development TOP project 91213058.

Biography

Dr Smits is a senior scientist at the Department of Viroscience, Erasmus Medical Center, and at Viroclinics Biosciences B.V. in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Her primary research interest is virus discovery.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Smits SL, Schapendonk CME, van Beek J, Vennema H, Schürch AC, Schipper D, et al. New viruses in idiopathic human diarrhea cases, the Netherlands. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2014 Jul [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2007.140190

References

- 1.Fauci AS, Morens DM. The perpetual challenge of infectious diseases. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:454–61 . 10.1056/NEJMra1108296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glass RI, Bresee J, Jiang B, Gentsch J, Ando T, Fankhauser R, et al. Gastroenteritis viruses: an overview. Novartis Found Symp. 2001;238:5–19, discussion 19–25. 10.1002/0470846534.ch2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Svraka S, Duizer E, Vennema H, de Bruin E, van der Veer B, Dorresteijn B, et al. Etiological role of viruses in outbreaks of acute gastroenteritis in The Netherlands from 1994 through 2005. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:1389–94 . 10.1128/JCM.02305-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friesema IH, De Boer RF, Duizer E, Kortbeek LM, Notermans DW, Smeulders A, et al. Aetiology of acute gastroenteritis in adults requiring hospitalization in The Netherlands. Epidemiol Infect. 2012;140:1780–6. 10.1017/S0950268811002652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bodewes R, van der Giessen J, Haagmans BL, Osterhaus AD, Smits SL. Identification of multiple novel viruses, including a parvovirus and a hepevirus, in feces of red foxes. J Virol. 2013;87:7758–64. 10.1128/JVI.00568-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reuter G, Boros A, Pankovics P. Kobuviruses: a comprehensive review. Rev Med Virol. 2011;21:32–41. 10.1002/rmv.677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phan TG, Vo NP, Bonkoungou IJ, Kapoor A, Barro N, O’Ryan M, et al. Acute diarrhea in West African children: diverse enteric viruses and a novel parvovirus genus. J Virol. 2012;86:11024–30 . 10.1128/JVI.01427-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganesh B, Banyai K, Martella V, Jakab F, Masachessi G, Kobayashi N. Picobirnavirus infections: viral persistence and zoonotic potential. Rev Med Virol. 2012;22:245–56. 10.1002/rmv.1707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giordano MO, Martinez LC, Rinaldi D, Guinard S, Naretto E, Casero R, et al. Detection of picobirnavirus in HIV-infected patients with diarrhea in Argentina. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998;18:380–3. 10.1097/00042560-199808010-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoek RA, Paats MS, Pas SD, Bakker M, Hoogsteden HC, Boucher CA, et al. Incidence of viral respiratory pathogens causing exacerbations in adult cystic fibrosis patients. Scand J Infect Dis. 2013;45:65–9. 10.3109/00365548.2012.708942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delwart E, Li L. Rapidly expanding genetic diversity and host range of the Circoviridae viral family and other Rep encoding small circular ssDNA genomes. Virus Res. 2012;164:114–21. 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.11.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sikorski A, Dayaram A, Varsani A. Identification of a novel circular DNA virus in New Zealand fur seal (Arctocephalus forsteri) fecal matter. Genome Announc. 2013;1:e00558–13.http:// [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Bodewes R, van de Bildt MW, Schapendonk CM, van Leeuwen M, van Boheemen S, de Jong AA, et al. Identification and characterization of a novel adenovirus in the cloacal bursa of gulls. Virology. 2013;440:84–8. 10.1016/j.virol.2013.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jartti T, Hedman K, Jartti L, Ruuskanen O, Allander T, Soderlund-Venermo M. Human bocavirus: the first 5 years. Rev Med Virol. 2012;22:46–64. 10.1002/rmv.720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okamoto H. History of discoveries and pathogenicity of TT viruses. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2009;331:1–20. 10.1007/978-3-540-70972-5_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Phylogenetic analysis of human bufavirus VS6600009 and a subset of human picobirnaviruses with relatively high homology with known picobirnaviruses, the Netherlands.