Abstract

Adult skeletal muscle in mammals is a stable tissue under normal circumstances but has remarkable ability to repair after injury. Skeletal muscle regeneration is a highly orchestrated process involving the activation of various cellular and molecular responses. As skeletal muscle stem cells, satellite cells play an indispensible role in this process. The self-renewing proliferation of satellite cells not only maintains the stem cell population but also provides numerous myogenic cells, which proliferate, differentiate, fuse, and lead to new myofiber formation and reconstitution of a functional contractile apparatus. The complex behavior of satellite cells during skeletal muscle regeneration is tightly regulated through the dynamic interplay between intrinsic factors within satellite cells and extrinsic factors constituting the muscle stem cell niche/microenvironment. For the last half century, the advance of molecular biology, cell biology, and genetics has greatly improved our understanding of skeletal muscle biology. Here, we review some recent advances, with focuses on functions of satellite cells and their niche during the process of skeletal muscle regeneration.

I. INTRODUCTION: SATELLITE CELLS AS ADULT STEM CELLS IN MUSCLE

Skeletal muscle is a form of striated muscle tissue, accounting for ∼40% of adult human body weight. Skeletal muscle is composed of multinucleated contractile muscle cells (also called myofibers). During development, myofibers are formed by fusion of mesoderm progenitors called myoblasts. In neonatal/juvenile stages, the number of myofibers remains constant, but each myofiber grows in size by fusion of satellite cells, a population of postnatal muscle stem cells. Adult mammalian skeletal muscle is stable under normal conditions, with only sporadic fusion of satellite cells to compensate for muscle turnover caused by daily wear and tear. However, skeletal muscle has a remarkable ability to regenerate after injury. Responding to injury, skeletal muscle undergoes a highly orchestrated degeneration and regenerative process that takes place at the tissue, cellular, and molecular levels. This results in the reformation of innervated, vascularized contractile muscle apparatuses. This regeneration process greatly relies on the dynamic interplay between satellite cells and their environment (stem cell niche). During the last half century, advances in molecular biology, cell biology, and genetics has greatly improved our understanding of skeletal muscle regeneration. In particular, extensive research on satellite cells and their niche has elucidated many cellular and molecular mechanisms that underlie skeletal muscle regeneration. These studies have contributed to the development of therapeutic strategies. These strategies serve to alleviate the physiological and pathological conditions associated with poor muscle regeneration observed in sarcopenia and muscular dystrophy.

Here, we concentrate on the functions of satellite cells and the regulation of their niche during the process of skeletal muscle regeneration. We first describe the current understanding of satellite cells with respect to their characteristics, heterogeneity, and embryonic origin. We then provide an integrated view of the roles played by satellite cells during muscle regeneration and normal postnatal muscle growth. We also discuss the contribution of several nonsatellite cell populations in muscle regeneration and their lineage relationships with satellite cells. Next, we focus on the satellite cell niche with emphasis on the regulatory mechanisms associated with each niche component. We further review the links between malfunction of satellite cells and their niche factors during aging. This review focuses on satellite cells and their niche in mammalian models, paying limited attention to the studies of satellite cell biology in other model organisms.

A. A Brief History of Satellite Cells

Half a century ago, Alexander Mauro observed a group of mononucleated cells at the periphery of adult skeletal muscle myofibers by electron microscopy (329). These cells were named satellite cells due to their sublaminar location and intimate association with the plasma membrane of myofibers.

The direct juxtaposition of satellite cells and myofibers immediately raised a hypothesis that these cells may be involved in skeletal muscle growth and regeneration (329). Indeed, experiments by [3H]thymidine labeling and electron microscopy demonstrated that satellite cells undergo mitosis, assume a cytoplasm-enriched morphology, and contribute to myofiber nuclei (355, 437). Later on, [3H]thymidine tracing experiments indicated that satellite cells are mitotically quiescent in adult muscle but can quickly enter the cell cycle following muscle injury (499). The same study also demonstrated that satellite cells give rise to proliferating myoblasts (myogenic progenitors cells), which were previously shown to form multinucleated myotubes in vitro (276, 499, 574). More definitive evidence came from in vitro cultures of individually dissected myofibers, whereby the behaviors of single myofibers and their resident satellite cells during regeneration can be tracked by phase-contrast microscopy (51, 277). It was observed that myofiber necrosis is accompanied by satellite cell outgrowth, clonal expansion, and later fusion to form functional regenerated myotubes. These experiments support the notion that it is the satellite cell, rather than the myonuclei, that contribute to postnatal muscle growth and repair.

The pivotal function of the satellite cell in muscle regeneration stimulated research to determine their regulatory mechanisms. This started with the finding that quiescent satellite cells on single myofibers were activated to enter the cell cycle by a mitogen originating from crushed skeletal muscles (53). In search of this mitogen, it was found that the proliferation and differentiation of satellite cell-derived myoblasts cultured in vitro respond to various growth factors in a dose-dependent manner (10, 11). Numerous studies further revealed that the proliferation and differentiation of satellite cells during muscle regeneration is profoundly influenced by innervation, the vasculature, hormones, nutrition, and the extent of tissue injury (121, 224, 250, 332, 360, 410). Interestingly, satellite cells in contact with the plasma membrane of intact myofibers were found to have reduced sensitivity to mitogen stimulation (50). All of these findings led to an intriguing notion that satellite cells reside in a special microenvironment in vivo, which profoundly affects their behavior.

By definition, stem cells found in adult tissues can both replicate themselves (self-renew) and give rise to functional progeny (differentiate). Although the ability of satellite cells to differentiate into myofibers was clearly proven, their ability to self-renew was once questioned. The first evidence of satellite cell self-renewal came from a single myofiber transplantation assay. It was found that as few as seven satellite cells, when transplanted into irradiated regeneration-insufficient mice along with their resident single myofiber, can give rise to hundreds of satellite cells and thousands of myonuclei. Most importantly, transplanted satellite cells on a single myofiber were able to support subsequent rounds of muscle regeneration (105). These observations demonstrate that satellite cells are bona fide muscle stem cells.

Asymmetric division is a common manner of stem cell self-renewal. Close examination of satellite cell divisions on single myofibers revealed that satellite cells can undergo both asymmetric division and symmetric division (280). The fashion of symmetric versus asymmetric division largely depends on the relative position of the daughter cells in relation to the myofiber. This finding strongly argues that satellite cell self-renewal is governed by the structure and signaling present in their immediate niche (280). Further investigation has revealed an important role for noncanonical Wnt signaling in the regulation of satellite cell self-renewal (293).

The aforementioned observations, together with those from other studies, formed the basis of our current view of satellite cells as muscle stem cells whose functions are dictated by their surrounding niche.

B. Identification and Isolation of Satellite Cells

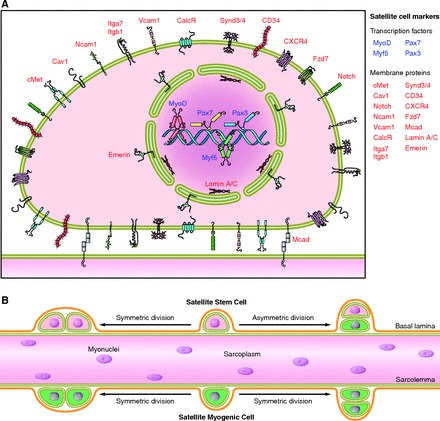

Classically, satellite cells were identified based on a unique anatomical location: beneath the surrounding basal lamina and outside the myofiber plasma membrane. This anatomical location gives satellite cells a “wedged” appearance when viewd by electrictron microscropy (329). This technique also revealed other morphological characteristics of satellite cells: large nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, few organelles, small nucleus, and condensed interphase chromatin. This morphology is in harmony with the notion that most satellite cells, in healthy unstressed muscles, are mitotically quiescent (in G0 phase) and transcriptionally inactive (472). In addition to electron microscopy, satellite cells can be identified by phase-contrast microscopy on single myofiber explants (53). Based on the same principle, the behaviors of satellite cells on single myofiber explants can be recorded by utilizing live cell imaging techniques (490). The identification of satellite cells by fluorescence microscopy relies on specific biomarkers (FIGURE 1). In adult skeletal muscle, all or most of satellite cells express the paired domain transcription factors Pax7 (478) and Pax3 (72), myogenic regulatory factor Myf5 (116), homeobox transcription factor Barx2 (336), cell adhesion protein M-cadherin (244), tyrosine receptor kinase c-Met (13), cell surface attachment receptor α7-intergin (73, 192), cluster of differentiation protein CD34 (37), transmembrane heparan sulfate proteoglycans syndecan-3 and syndecan-4 (113), chemokine receptor CXCR4 (429), caveolae-forming protein caveolin-1 (192, 552), calcitonin receptor (177), and nuclear envelope proteins lamin A/C and emerin (192). Of these, Pax7 is the canonical biomarker for satellite cells as it is specifically expressed in all quiescent and proliferating satellite cells (478) across multiple species, including human (334), monkey (334), mouse (478), pig (402), chick (216), salamander (353), frog (96), and zebrafish (219). Of note, some of the aforementioned satellite cell markers (e.g., α7-intergin, CD34) are also expressed on other cell types within skeletal muscle, and thus should not be utilized alone to unequivocally identify satellite cells. Satellite cells can be identified by fluorescence microscopy via combined immunofluorescence labeling of laminin and M-cadherin, which respectively label the basal lamina and plasma membrane of satellite cells contacting the myofibers (517). In vivo, satellite cell populations can be visualized with the aid of newly developed bioluminescence imaging techniques (454, 558).

Figure 1.

Characteristics of the satellite cell. A: numerous proteins are expressed in satellite cells and have been used as markers to distinguish between surrounding cell types within skeletal muscle. Due to heterogeneity in satellite cell populations, it is unlikely that all of these markers are expressed in a given satellite cell at a specific time. Nevertheless, this panel summarizes the cellular location of markers used to identify satellite cells. B: the satellite cell population is heterogeneous and can be classified in a hierarchical manner based on function and gene expression. Evidence from lineage tracing experiments identified a subpopulation of satellite cells having never expressed the myogenic transcription factor Myf5 (satellite stem cells) are placed hierarchically above satellite cells that have expressed Myf5 at some point during development (satellite myogenic cells). Satellite stem cells, upon asymmetric division (typically in a apical-basal orientation), will give rise to two daughter cells, only one of which has activated Myf5. Functional differences in regenerative potential exist between satellite stem cells and satellite myogenic cells. Following transplantation, satellite stem cells preferentially repopulate the satellite cell niche and contribute to long-term muscle regeneration. In contrast, satellite myogenic cells preferentially differentiate upon transplantation in vivo.

Multiple methodologies have been developed to isolate satellite cells from skeletal muscle. The choice of methods largely depends on the isolation scale and the subsequent experiment. In small scale, limited amounts of satellite cells can be released from single myofiber explants by physical trituration (446) or enzymatic digestion (107). In large scale, satellite cells can be isolated from skeletal muscles by fluorescent-activated cell sorting (FACS). In the latter method, single cells are released from muscle tissue chunks by enzymatic digestion, followed by immunofluorescence labeling of satellite cell-specific cell surface markers (positive selection) and definitive cell surface markers for nonsatellite cell populations (negative selection). As Pax7 is specifically expressed in satellite cells within skeletal muscle, satellite cells, in both quiescent and proliferating stages, can be FACS-sorted by fluorescent protein expression in tamoxifen-injected animals carrying both a Pax7CreER allele and a fluorescence Cre reporter allele (e.g., R26R-EYFP). In addition, two transgenic mouse strains, which carry fluorescence proteins driven by Nestin- or Pax7-regulatory elements, are also useful for isolating satellite cells by FACS (63, 127).

Protocols have been developed to isolate satellite cells in bulk utilizing their characteristic proliferation and adhesion characteristics under defined culturing conditions (144, 364, 425). It is noteworthy that the satellite cell progeny cultured on regular collagen-coated plastic dishes and under activation conditions, also called satellite cell-derived primary myoblasts, are molecularly and functionally distinct from the satellite cells freshly isolated from muscles (160, 177, 350). In addition, the gene expression profile of these cultured primary myoblasts differs from that of activated satellite cells in vivo (398). These essential differences are possibly due to the lack of a satellite cell niche in in vitro culturing conditions. One challenge in future studies is to understand the components and role of the satellite cell niche to better control and manipulate their quiescence, activation, proliferation, and differentiation.

C. Heterogeneity of Satellite Cell Population

Satellite cells were considered to be a homogeneous population of committed muscle progenitors (52). However, recent evidence demonstrated that the satellite cell population is heterogeneous and that satellite cells differ in their gene expression signatures, myogenic differentiation propensity, stemness, and lineage potential to assume nonmyogenic fates.

With regard to gene expression, it was first observed that only a subset of satellite cells expresses Pax3, a close paralog to Pax7 (350, 431). Although Pax3+ satellite cells tend to be associated with skeletal muscle of certain anatomical locations (e.g., diaphragm and truck muscles), the difference of Pax3 expression does not seem to correlate with their embryonic origins, metabolic fiber types, or types of innervating motor neurons. Examination of the expression of satellite cell markers CD34, M-cadherin, and Myf5 by immunofluorescence staining revealed that a subpopulation of satellite cells do not express these markers (37). Similarly, human satellite cells also manifest heterogeneity in their Pax7, neuronal cell adhesion molecule (NCAM), c-Met, and Dlk1 expression (311). By RT-qPCR, two recent studies showed that satellite cells from head or body muscles are distinct in their molecular signatures (225, 456). Notably, the heterogeneity of gene expression in single satellite cells was investigated in a recent study, wherein the expression of Pax7, Pax3, Myf5, and MyoD was interrogated by RT-qPCR for 40 individually FACS-isolated muscle stem cells (CD45−/CD11b−/CD31−/Sca-1−/α7-intergin+/CD34+) (454). All of these muscle stem cells express Pax7, indicating they are satellite cells. In addition to the varied expression of Pax3, it was also found that 25% of investigated satellite cells also express MyoD, a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor critical for myogenic commitment and differentiation. A recent study discovered a small subpopulation of satellite cells, characterized by their surface markers Sca-1+/ABCG2+ (as compared with Sca-1−/ABCG2− for most satellite cells), is able to exclude Hoechst 33342 dye and thus belongs to the skeletal muscle side population (satellite-SP cells) (518). After transplantation into damaged muscle, satellite-SP cells can both fuse to regenerating myofibers and return to quiescence in the satellite cell niche. However, by lineage tracing, ABCG2+ cells (including satellite-SP cells) seem to only have minor contribution to myofiber regeneration (146).

Satellite cells are also heterogenic in their differentiation potential. Satellite cells on single myofibers isolated from various skeletal muscle sources were transplanted into irradiated muscles of mdx/nude mice, which underwent repeated regeneration and were depleted of endogenous satellite cells (105). It was observed that the number of regenerated myofibers contributed by tibialis anterior (TA) originated grafts was significantly less than that derived from either extensor digitorum longus (EDL) or soleus muscle. Although the potential contribution from donor myofibers cannot be precisely evaluated, this observation strongly suggests inherent differences in proliferation/differentiation potential of satellite cells and/or composition of satellite cell subpopulations from various muscles. In line with this view, continuous BrdU labeling of satellite cells in vivo revealed two satellite cell populations that are distinct in terms of their mitotic rates (471). It was found that the majority (∼80%) of satellite cells readily enter the cell cycle (responsive population), whereas the remaining 20% of satellite cells (reserve population) do this in a much slower manner. It has been proposed that the reserve population maintains in the quiescent state at the beginning of muscle growth/regeneration and only moves into this proliferative state in response to the need for extensive muscle growth/regeneration (471). In line with this view, a recent study traced satellite cell divisions by a fluorescent dye PKH26, which revealed the minority of PKH26high slow-dividing satellite cells retained long-term self-renewal ability (388). Notably, a recent study thoroughly compared the gene expression profiles and proliferation/differentiation potential of satellite cells isolated from limb and facial muscles of adult and aged mice (387). This study revealed broad satellite cell heterogeneity at both the population and single-cell levels. Despite their heterogeneous gene expression profiles, satellite cells isolated from limb (EDL) and facial (masseter) muscles are comparable in their ability to repair a limb (TA) muscle injury after transplantation. This finding suggests that although satellite cells from various muscles have distinct gene expression and behaviors in vitro, their regeneration potential in vivo might be largely determined by host stem cell niche and microenvironment.

Most importantly, recent studies revealed satellite cell heterogeneity in terms of their stemness and indicate that only a small percentage of satellite cells are true stem cells (109, 280, 489). By immunofluorescence staining of freshly isolated single myofibers from Myf5-nLacZ mice, our group demonstrated that 13% of quiescent satellite cells on EDL muscles are LacZ−, making them distinct from the LacZ+ satellite cells (280). As Myf5 is a myogenic regulatory factor, the absence of Myf5 expression suggests a less committed cell fate for those LacZ− satellite cells. Moreover, by the Cre-LoxP based lineage tracing technique, our group further discovered that 10% of satellite cells in Myf5Cre;R26R-YFP mice do not express YFP (Pax7+/YFP− satellite cells), indicating that this small percent of satellite cells have never expressed Myf5 as did the majority of satellite cells (Pax7+/YFP+). Remarkably, these two distinct satellite cell subpopulations also differ in terms of their regenerative potential: the Pax7+/YFP− satellite cells were able to reconstitute the stem cell niche and repaired muscles in a sustainable manner, whereas the Pax7+/YFP+ satellite cells directly underwent myogenic differentiation when transplanted in regenerating muscles of Pax7−/− mice. We further demonstrated that only Pax7+/YFP− satellite cells could undergo asymmetric cell divisions, giving rise to a Pax7+/YFP− satellite stem cell and a Pax7+/YFP+ satellite committed progenitor cell. These findings indicate that a hierarchical lineage progression from the Pax7+/YFP− (satellite stem cell) to the Pax7+/YFP+ (satellite committed progenitors) exists within the total satellite cell population. Consistent with this notion, multiple studies reported that only a subset of satellite cells undergo asymmetric division in vivo or in vitro (108, 109, 489). For example, Numb, an inhibitor of Notch signaling and a cell-fate determinant, was found to asymmetrically distribute in some but not all satellite cell divisions (108, 489). By pulse labeling or tandem pulse labeling of growing/regenerating muscles with halogenated thymidine analogs, it was further discovered that all “older” chromosomes (the template chromosome during DNA replication during S phase) cosegregate into the more stemlike daughter cell, whereas “younger” chromosomes are inherited by the more differentiated daughter cell during asymmetric divisions of satellite cells both in vivo and in vitro (109, 489). According to the “immortal DNA strand” hypothesis (75), this preferential retention of “older” chromosomes protects stem cells against the accumulation of mutations introduced during DNA replications (109, 489). Alternatively, it has been also proposed that the nonrandom segregation of sister chromatids, and hence their different epigenetic states, is essential to the gene expression patterns and cellular fates of satellite stem cells and satellite progenitor cells (289). In summary, the aforementioned findings support satellite cell heterogeneity whereby the existence of a hierarchy delineates a small population of true stem cells (satellite stem cells) from a more committed myogenic progenitor population of satellite cells. The satellite stem cells are less committed to the myogenic lineage and tend to retain older template DNA during division. Through asymmetric division, satellite stem cells self-renew to replenish the stem cell pool and produce more committed myogenic progenitors that participate in skeletal muscle growth and regeneration.

Satellite cells also exhibit heterogeneity in respect to their cell fate potential. Our group first revealed that satellite cells have an intrinsic potential to differentiate into multiple mesenchymal lineages (23). When cultured on solubilized basement membrane matrix (matrigel), satellite cells from single myofibers spontaneously differentiate into myocytes, adipocytes, and osteocytes. This finding indicates that satellite cells functionally resemble bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. This notion is substantiated by another study wherein satellite cells were found to assume the adipocyte lineage, which can be enhanced upon oxygen-rich culture conditions (120). By clonal analysis, it was found that myogenic and adipogenic satellite cells are two separate populations in the satellite cell compartment, although both populations express the myogenic marker Pax7 as well as the adipogenic markers peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors γ (PPARγ) and CCAAT/enhancer binding proteins (C/EBPs) (485). This similar molecular signature may reflect a common developmental origin of satellite cells and adipogenic progenitors in embryonic somites (discussed in sect. IIE). Satellite cell heterogeneity with regard to myogenic and nonmyogenic potential was thoroughly investigated by in vitro differentiation and in vivo transplant assays (486). In this study, myofiber-associated satellite cells were isolated from undamaged skeletal muscle by a two-step enzymatic digestion and sorted by FACS based on their differential expression of cell surface markers, CD45 and Sca-1. It was found that the vast majority of myogenic satellite cells are within the CD45−/Sca-1− population and exhibited no in vitro differentiation potential into fibroblasts or adipocytes. In contrast, the minor population of CD45−/Sca-1+ satellite cells can differentiate into both fibroblasts and adipocytes in culture, a similarity that is shared with CD45−/Sca-1+ mesenchymal stem cells found in multiple tissues (316, 401, 417, 441, 509, 519). Despite the plasticity of satellite cells in vitro, it is important to note that myogenesis is the predominant fate of satellite cells in vivo as fibrosis or adipose infiltration is not normally observed in young healthy muscle. Furthermore, recent studies indicate that intramuscular adipocytes and fibroblasts can also arise from fibrocyte/adipocyte progenitors (FAPs), which reside in the muscle interstitium (252, 541; and discussed in sect. IIIB1). Indeed, lineage tracing experiments indicate that adipocytes derived from myofibers isolated from MyoDiCre;R26R-EYFP mice have never transcribed MyoD (507). As the vast majority of adult satellite cells were permanently labeled with EYFP in this experiment, this finding argues that most satellite cells from myofiber cultures do not spontaneously differentiate into adipocytes. Further investigation with more definitive lineage tracing (e.g., Pax7CreER;R26R-EYFP) methods would clarify the exact contribution of satellite cells to other nonmyogenic lineages both in vitro and in vivo.

As discussed here, multiple lines of evidence demonstrate that satellite cells represent a heterogeneous population. However, our understanding of this heterogeneity is far from complete. First, although several markers can separate the total satellite cell population into functional subpopulations, it is still unknown whether these subpopulations are homogeneous in their function and gene expression. Further studies to identify additional satellite markers will potentially help distinguish the various satellite cell lineages. Moreover, future investigations should attempt to identify the intrinsic differences between satellite cell subpopulations at the molecular and functional levels during muscle regeneration. Such findings would elucidate regulatory mechanisms governing the transition between different satellite cell subpopulations and potentially distinct roles of satellite cell subpopulations during muscle regeneration. In addition, it would be of great importance to understand the dynamics of satellite cell heterogeneity in response to various environmental cues with regard to research in muscle regeneration and disease.

D. Variance of Satellite Cells Number and Location

In addition to the heterogeneity of satellite cells, the quantity of satellite cells differs between muscles, myofiber types, developmental stages, and species. In general, satellite cells account for 30–35% of the sublaminal nuclei on myofibers in early postnatal murine muscles, and this number declines to 2–7% in adult muscles (9, 227, 450, 469). In adults, the percentage of satellite cells in soleus muscle is generally two- to fourfold higher than that in tibialis anterior muscle or EDL muscle (190, 466, 500). Within the same muscle, the number of satellite cells found on slow muscle myofibers (type I) is generally higher than those on fast myofibers (type IIa and type IIb) (190, 324, 383). The biological meaning and the potential regulatory mechanisms underlying these phenomena are poorly understood. However, it is conceivable that these variances may reflect intrinsic heterogeneity of satellite cells on different myofibers and implicate a potential role of myofibers as a niche factor in regulating the homeostasis of their resident satellite cells.

Along a myofiber, the distribution of satellite cells is not random. It has been reported that the density of satellite cells is higher at the ends of the myofibers, where the longitudinal growth of skeletal muscles happens (14). A higher incidence of satellite cells has been observed at perisynaptic regions compared with that at extrasynaptic regions (190, 269, 567). Moreover, satellite cells have been observed in close proximity to capillaries (100, 466). In fact, 88% of satellite cells in adult human muscles were observed to be located within a 21-μm distance of a capillary (100). This tight association with capillaries seemed to be compromised by denervation (130). These observations indicate that homing of satellite cells is influenced by their niche, both by local motor neurons and blood vessels (discussed in sect. IIIB).

It is noteworthy that some reported variation in satellite cell numbers may be partially due to techniques or statistical analysis employed in satellite cell counting. For example, satellite cell counting based on immunofluorescence labeling of satellite cell specific markers relies on the comparable expression levels of these markers on all satellite cells under investigation. As such, special caution should be taken into account when interpreting data between independent experiments.

E. Origins of Adult Satellite Cells

1. Embryonic origins

By classic techniques of developmental biology, it has long been established that skeletal muscles within both the adult trunk and limbs develop from embryonic somites (462). However, the exact origin of adult satellite cells was obscure until recently.

Early experiments using a quail-chick chimera technique suggested a somitic origin of satellite cells in amniotes (18). Embryonic somites are segments of paraxial mesoderm formed on both sides of the body axis. In this experiment, somites from donor quail embryos were transplanted into host chick embryos. After embryonic development, the contribution of quail cells to the chick satellite cell compartment was determined using Feulgen staining, which distinguishes quail-specific interphase nuclei from those of chick. It was found that donor cells from quail somites integrated into the chick limb and contributed to both terminally differentiated muscle fibers and satellite cells. This finding indicated a common somitic origin for all myogenic cell lineages, including satellite cells. However, the progenitor cell types at the origin and the developmental route remain unknown.

Advances in mouse genetics, particularly the generation of Pax3 and Pax7 knock-in reporter alleles, allows precise tracing of Pax3/Pax7-expressing myogenic progenitor cells during muscle development in a temporal and spatial manner (265, 326, 350, 432, 433). These reporters together with labeling of cells by electroporation (40, 203), retrovirus (464), Cre-LoxP based lineage tracing (263, 300, 464), and traditional quail-chick transplantation (203, 464), jointly shed light on the embryonic origins of adult satellite cells. Accumulating evidence indicates that adult satellite cells originate from the dermomyotome (203, 265, 434, 464), an epithelial structure formed on the dorsal part of the somite. The dermomyotome contains multipotent progenitor cells, which eventually give rise to multiple adult tissues/cell types including dermal fibroblasts, endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle, brown fat tissue, and all skeletal muscles of the trunk and limbs (71). The cell fate decisions largely depend on the relative position of these multipotent progenitor cells with respect to adjacent tissues such as the notochord, neural tube, dorsal ectoderm, and myotome (71).

Embryonic muscle development takes place in two successive stages. During the first stage, a group of postmitotic mononucleated myocytes, expressing Myf5 and Mrf4, migrate out from the border regions of the dermomyotome and form primitive muscles beneath the dermomyotome (204, 261). These primitive muscles constitute the primary myotome and are the source of fetal and adult trunk muscles. During the second stage of muscle growth, the central portion of the dermomyotome undergoes an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). During EMT, tightly packed epithelial cells tease apart and turn in a loose mesenchymal state prior to assuming different developmental fates: cells in the medial dermomyotome will develop into brown fat, dermis, and trunk muscle, while cells in the lateral dermomyotome will give rise to endothelia and limb muscles. The different cell fates assumed by the same group of progenitor cells are proposed to be due to asymmetric cell division (40, 101). EMT is accompanied by the extensive cell migration (203, 265, 434, 464). With the breakdown of dermomyotome, a group of proliferating progenitor cells, expressing both Pax3 and Pax7, migrate from the central region of the dermomyotome into the previously formed primary myotome. Upon arrival, some progenitor cells continue to proliferate and replenish the progenitor pool. These cells, which were absent from the primary myotome at earlier stages, count for the majority of all proliferating cells in embryonic/fetal trunk muscles (203, 434). Some of the proliferating Pax3+/Pax7+ progenitor cells persist into late fetal development stages and are enveloped beneath the basal lamina of developing myofibers (203, 434). These cells, which reside in the satellite cell compartment, are presumed to subsequently become the postnatal satellite cells in trunk muscles. Besides proliferation, progenitor cells also exit the cell cycle and begin differentiating into embryonic/fetal truck muscles. Cell cycle withdrawal is concomitant with the expression of the myogenic regulatory factors MyoD and Myf5 (453).

During EMT, another group of proliferating progenitor cells, expressing Pax3 (but not Pax7 in mouse), delaminate from the ventral-lateral border of the dermomyotome and migrate to the limb bud mesenchyme (265, 392, 464). These progenitor cells still maintain their multipotency as they give rise to the limb vascular, lymphatic endothelia, and limb muscles (226, 264). At E11.5 of mouse embryo development, some progenitor cells start to express Pax7 in the anterior limb buds (433). The expression of Pax7 specifies these cells to the myogenic lineage (242). Similar to the myotome-located progenitors, these Pax3+/Pax7+ progenitor cells in limb buds undergo proliferation/differentiation while a portion withdraw from cell cycle and become satellite cells.

All together, these observations indicate that Pax3+/Pax7+ embryonic progenitor cells are the major source of adult satellite cells in truck and limb muscles; it is, however, noteworthy that the aforementioned observations from lineage tracing and immunofluorescence labeling experiments cannot exclude the possibility that some adult satellite cells may originate from other sources during fetal and postnatal muscle development. For example, embryonic dorsal aorta explants, when cultured and disaggregated in vitro, can efficiently give rise to myogenic precursors (129). These myogenic precursors are similar to satellite cells in their gross morphology and expression of molecular markers. Given that adult satellite cells also express endothelial markers, it was proposed that some adult satellite cells originated from the embryonic dorsal aorta (129). However, recent studies revealed that both skeletal muscles and smooth muscles found in dorsal aorta are derived from the same Pax3+ cell population in the paraxial mesoderm (155). Thus it is also possible that the observed similarities are merely reminiscent of a common embryonic origin before myogenic specification.

Distinct from trunk and limb muscles, head muscles have multiple embryonic origins. The majority of head muscles, including branchiomeric muscles and most extraocular muscles, arise from the cranial paraxial mesoderm (CPM) (225, 540). Posterior neck muscles and tongue develop from occipital somites. Similar to progenitor cells migrating to limb buds, the progenitor cells for tongue delaminate from the ventral-lateral border of occipital somites. A small fraction of extraocular muscles also arise from the prechordal mesoderm (PM). On the basis of observations from lineage tracing experiments, it has been found that adult satellite cells of the various head muscles originate from their corresponding embryonic muscles and express distinct combinations of signature genes (225). Unlike trunk and limb progenitors, most progenitor cells for head muscles (except for tongue) express MesP1 rather than Pax3.

2. Alternative origins of adult satellite cells

Accumulating evidence indicates that some adult satellite cells may have alternative origins other than dermomyotome-derived Pax3+/Pax7+ progenitor cells.

First, multiple studies have demonstrated that several types of nonsatellite cells can reconstitute the satellite cell niche and turn into bona fide satellite cells (Pax7-expressing myogenic cells) after transplantation into regenerating skeletal muscles (for details, see sect. IID). It remains, however, largely unknown to what extent these cells contribute to the adult satellite cell pool and muscle development under physiological conditions. Notably, a recent study utilizing TN-APCreERT2 and VE-cadherinCreERT2 alleles showed that alkaline phosphatase (ALPL) expressing pericytes, but not VE-cadherin-expressing endothelial cells, can develop into postnatal satellite cells and participate in normal development of limb muscles (135).

It is noteworthy that some adult satellite cells in mammals may be derived from dedifferentiation of fetal/adult myofibers. It has long been established that the dedifferentiation of “terminally” differentiated multinucleated myofibers occurs in injured skeletal muscle of urodele amphibians, such as the newt (69). Nevertheless, it remains controversial as to whether mammalian myotubes in vitro or myofibers in vivo can undergo a similar dedifferentiation process. Studies utilizing immortalized murine myoblast cell lines (e.g., C2C12 or pmi28 cells) have shown that some myotubes formed by these cells can dedifferentiate into mononucleated myogenic cells in the presence of protein extract from regenerating newt muscles (331), bioactive compounds like myoseverin or its derivatives (149, 443), ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) (95), or by genetic manipulations such as overexpression of Msx1 (379), Twist1 (232), Barx2 (335), or knockdown of Rb1 in conjunction with a deficiency for Cdkn2a (p16Ink4a) (395). By a novel fusion-dependent lineage tracing technique, two recent studies reported that differentiated myotubes formed by satellite cell-derived primary myoblasts (397) or muscle-derived cells (MDCs) (359) can dedifferentiate into Pax7-expressing mononucleated myogenic cells in vitro in response to an inhibitor cocktail (a tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor plus an apoptosis inhibitor) or within regenerating muscle in vivo. Although still not experimentally tested on myofibers formed during development, these intriguing observations jointly suggest that some adult satellite cells may be “recycled” from multinucleated myofibers in vivo during postnatal muscle growth or regeneration. Future studies may employ the fusion-dependent lineage tracing technique in chimeric mice to investigate the physiological relevance of this alternative source of satellite cells.

II. FUNCTIONS OF SATELLITE CELLS IN MUSCLE REGENERATION

Skeletal muscles consist of myofibers, neurons, vasculature networks, and connective tissues, of which the structural and functional element of skeletal muscle is the myofiber. Each myofiber is surrounded by the endomysium (also called the basement membrane or basal lamina). Bundles of myofibers are surrounded by the perimysium, while the entire muscle is contained within the epimysium. Each myofiber is anchored at its extremities to tendons or tendon-like fascia at the myotendinous junctions (MTJs) (531). Myofibers are composed of actin and myosin myofibrils repeated as a sarcomere, which is the basic functional unit of skeletal muscle. Responding to the signals from motor neurons, myofibers depolarize and release calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). This drives the movement of actin and myosin filaments relative to one another and leads to sarcomere shortening and muscle contraction.

Based on their physiological properties, skeletal muscle fibers can be grouped into a slow-contracting/fatigue-resistant type and a fast-contracting/fatigue-susceptible type. Myofibers also vary in terms of their myosin heavy chain (MyHC) isoforms (fast or slow) and metabolism types (oxidative or glycolytic). The choice of myosin gene expression is under the dynamic regulation of thyroid hormone and work load (reviewed in Ref. 28). Recent studies demonstrated that the specification of myosin expression is also regulated by intronic microRNAs within MyHC genes (545, 546).

Mammalian skeletal muscle during adulthood is a stable postmitotic tissue with infrequent turnover of myonuclei (467). Minor lesions inflicted by day-to-day wear and tear can be repaired without causing cell death, inflammatory responses, or histological changes. For instance, local plasma membrane damage caused by spontaneous eccentric muscle contractions can be efficiently repaired by recruiting intracellular vesicles to patch the damaged membrane (30, 508). This repair process involves dysferlin and caveolin-3 (30, 181), and mutations of these genes cause limb girdle muscular dystrophy 2B (LGMD-2B) (36, 314) and 1C (LGMD-1C) (344), respectively. In contrast, severe muscle injuries due to either traumatic lesions (e.g., extensive physical activity such as resistance training, or exposure to myotoxin) or genetic defects (e.g., muscular dystrophies) are accompanied by myofiber necrosis, inflammatory responses, activation of satellite cells, proliferation, and differentiation of satellite cell-derived myoblasts (FIGURE 2). This process, starting from myofiber necrosis and ending with new myofiber formation, is called muscle regeneration. It should be stressed that satellite cells play a pivotal role during muscle regeneration under either physiological conditions (e.g., extensive exercise) (400, 457) or pathological conditions (e.g., myotoxin induced injury) (301, 361, 457). This notion is clearly supported by the findings that ablation of the total satellite cell pool (all Pax7+ cells) in adulthood completely abolished muscle regeneration (301, 361, 457). It has been reported that several types of nonsatellite cells can undergo myogenic differentiation and contribute to muscle regeneration after transplantation into regenerating muscle (24, 210, 287, 345, 413). Nevertheless, the contribution of these cells to adult muscle regeneration seems to be negligible compared with satellite cells, implying the physiological relevance of nonsatellite cell-based myogenesis might depend on Pax7 expression and/or the existence of considerable numbers of satellite cells.

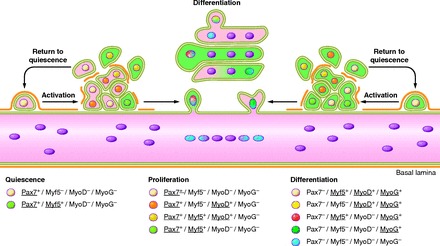

Figure 2.

Satellite cell activation, differentiation, and fusion. The myogenic program is orchestrated by key transcription factors that dictate the progression from quiescence, activation, proliferation, and differentiation/self-renewal of satellite cells. This results in the transformation of individual satellite cells into a syncytial contractile myofiber. Initially satellite cells are mitotically quiescent (G0 phase) and reside in a sublaminar niche. Quiescent satellite cells are characterized by their expression of Pax7 and Myf5 but not MyoD or Myogenin. Damage to the environment surrounding satellite cells results in the deterioration of the basal lamina and their exit from the quiescent state (satellite cell activation). Proliferating satellite cells and their progeny are often referred to as myogenic precursor cells (MPC) or adult myoblasts. Adult myoblasts express the myogenic transcription factors MyoD and Myf5. Following proliferation, adult myoblasts begin differentiation by downregulating Pax7. The initiation of terminal differentiation and fusion begins with the expression of Myogenin, which in concert with MyoD will activate muscle specific structural and contractile genes. During regeneration, activated satellite cells have the capability to return to quiescence to maintain the satellite cell pool. This ability is critical for long-term muscle integrity.

In this section, we examine the extensive cellular and molecular dynamics during muscle regeneration, with emphasis on satellite cell. We also review the potential of nonsatellite cell lineages on muscle regeneration. At the end of this section, we briefly describe the function of satellite cells in normal postnatal muscle development, and compare and contrast this with muscle regeneration in adulthood.

A. An Introduction to Muscle Regeneration

Muscle regeneration occurs in three sequential but overlapping stages: 1) the inflammatory response; 2) the activation, differentiation, and fusion of satellite cells; and 3) the maturation and remodeling of newly formed myofibers.

Muscle degeneration begins with necrosis of damaged muscle fibers. This event is initiated by dissolution of the myofiber sarcolemma, which leads to increased myofiber permeability. Disruption of myofiber integrity is reflected by increased plasma levels of muscle proteins and microRNAs, such as creatine kinase (17) and miR-133a (292), which are usually restricted to the myofiber cytosol. Similarly, the compromised sarcolemmal integrity also allows the uptake of low-molecular-weight dyes, such as Evans blue or procion orange, by the damaged myofiber, which is a reliable indication of sarcolemmal damage associated with extensive exercise and muscle degenerative diseases (218, 328, 396). Moreover, myofiber necrosis is accompanied by increased calcium influx or calcium release from the SR, which in turn activates calcium-dependent proteolysis and drives tissue degeneration (reviewed in Refs. 7, 19, 39). In this process, calpain, a calcium-activated protease, has been shown to cleave myofibrillar and other cytoskeletal proteins (reviewed in Ref. 145). Myofiber necrosis also activates the complement cascade and induces inflammatory responses (389). Subsequent to inflammatory responses, chemotactic recruitment of circulating leukocytes occurs at local sites of damage (reviewed in Ref. 530). Neutrophils are the first inflammatory cells to infiltrate the damaged muscle, with a significant increase in their number being observed as early as 1–6 h after myotoxin- or exercise-induced muscle damage (168). Following neutrophil infiltration, two distinct subpopulations of macrophages sequentially invade the injured muscle and become the predominant inflammatory cells (91). The early invading macrophages, characterized by the surface markers CD68+/CD163−, reach their highest concentration in damaged muscle at ∼24 h after the onset of injury and thereafter rapidly decline. These CD68+/CD163− macrophages secrete proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin (IL)-1, and are responsible for the phagocytosis of cellular debris. A second population of macrophages, characterized by the surface markers CD68−/CD163+, reach their peak at 2–4 days after injury. These macrophages secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-10, and persist in damaged muscle until the termination of inflammation. Notably, the CD68−/CD163+ macrophages also reportedly facilitate the proliferation and differentiation of satellite cells (80, 81, 303, 341, 503).

A highly orchestrated regeneration process follows muscle degeneration. A hallmark of this stage is extensive cell proliferation. Blocking cell proliferation by colchicine treatment (411) or irradiation (423) drastically reduced muscle regenerative capacity. Experiments by [3H]thymidine labeling have clearly demonstrated that the proliferation of satellite cells and their progeny provide a sufficient source of new myonuclei for muscle repair (498, 499, 554; reviewed in Ref. 79 and discussed in sect. IIB). It is commonly agreed that following proliferation, myogenic cells differentiate and fuse to existing damaged fibers or fuse with one another to form myofibers de novo. This process, in many but not all respects, recapitulates embryonic myogenesis.

Muscle regeneration can be characterized by a series of morphological characteristics based on histological and immunofluorescence staining. On muscle cross-sections, newly formed myofibers can be readily distinguished by their small caliber and centrally located myonuclei. These myofibers are often basophilic in the beginning of regeneration due to protein synthesis and the expression of embryonic/developmental forms of MyHC (217, 562). On muscle longitudinal sections and on isolated single myofibers, the centrally localized myonuclei were observed in discrete segments of regenerating myofibers or along the entire new myofiber, which suggests that cell fusion during regeneration happens in a focal, rather than diffuse, manner (58). Occasionally, concentrated regenerative processes may appear as local protrusions (also called budding) on myofibers. Muscle regeneration can often lead to architectural changes of the regenerated myofibers, which are presumably due to incomplete fusion of regenerating fibers within the same basal lamina (57, 58, 64, 465). Newly formed myotubes may not fuse to each other, resulting in clusters of small caliber myofibers within the same basal lamina. Alternatively, they may fuse only at one end, leading to the formation of forked (also called branching or splitting) myofibers. Myofiber branching was commonly observed in muscles from patients suffering neuromuscular diseases, in hypertrophied muscles, and in aging muscles, suggesting this phenotype may relate to abnormal muscle regenerative capacity (59, 90). Small regenerating myofibers may also form outside the basal lamina in the interstitium, due to migration of satellite cells or other types of myogenic cells. Finally, the reconstitution of myofiber integrity may be prevented by scar tissue that separates the two regenerative sites, leading to the formation of a new myotendinous junction.

At the end of muscle regeneration, newly formed myofibers increase in size, and myonuclei move to the periphery of the muscle fiber. Under normal conditions, the regenerated muscles are morphologically and functionally indistinguishable from undamaged muscles.

B. Satellite Cell Activation and Differentiation

In intact muscle, satellite cells are sublaminal and mitotically quiescent (G0 phase). Quiescent satellite cells are characterized by their expression of Pax7 but not MyoD or Myogenin (116). Examination of β-galactosidase activity in Myf5-LacZ mice indicated that the Myf5 locus is active in ∼90% of quiescent satellite cells, which suggests most satellite cells are committed to the myogenic lineage (37).

Upon exposure to signals from a damaged environment, satellite cells exit their quiescent state and start to proliferate (satellite cell activation). Proliferating satellite cells and their progeny are often referred to as myogenic precursor cells (MPC) or adult myoblasts. Satellite cell activation is governed by multiple niche factors and signaling pathways (discussed in detail in sect. IIIA). Satellite cell activation is not only restricted to the site of muscle damage. In fact, localized damage at one end of a muscle fiber leads to the activation of all satellite cells along the same myofiber and migration of these satellite cells to the regeneration site (473). Satellite cell activation is also accompanied by extensive cell mobility/migration. It has been observed that satellite cells can migrate between myofibers and even muscles across barriers of basal lamina and connective tissues during muscle development, growth, and regeneration (241, 251, 557). Recently, sialomucin CD34, whose expression is high on quiescent satellite cells but dramatically reduced during satellite cell activation, was demonstrated to act as an antiadhesive molecule to facilitate migration and promote the proliferation of satellite cells at very early stages of muscle regeneration (8). In addition, dynamic regulation of Eph receptors and ephrin ligands in activated satellite cells and regenerating myofibers have been shown to direct satellite cell migration (506).

Unlike quiescent satellite cells, myogenic precursor cells are characterized by the rapid expression of myogenic transcription factors MyoD (111, 114, 116, 175, 207, 497, 572, 585) and Myf5 (111, 116). Of note, the presence of MyoD, desmin, and Myogenin in satellite cells was observed as early as 12 h after injury, which is before any noticeable sign of satellite cell proliferation (426, 497). This early expression of MyoD is proposed to be associated with a subpopulation of committed satellite cells, which are poised to differentiate without proliferation (426). In contrast, the majority of satellite cells express either MyoD or Myf5 by 24 h following injury (111, 116, 585) and subsequently coexpress both factors by 48 h (111, 116). The ability of satellite cells to upregulate either MyoD or Myf5 suggests these two transcription factors may have different functions in adult myogenesis.

First, MyoD−/− mutant mice display markedly reduced muscle mass (338). This atrophy phenotype is reportedly due to delayed myogenic differentiation (564, 573). Similarly, muscle regeneration is also impaired in MyoD−/− mice, resulting in an increased number of myoblasts within the damaged area (338). These MyoD−/− myoblasts persist for extended periods of time, fail to differentiate, and do not fuse into myotubes. This is consistent with the notion that MyoD−/− myoblasts, when cultured in myogenic differentiation conditions, continue to proliferate and eventually give rise to a decreased number of differentiated mononucleated myocytes (114, 452, 573). Intriguingly, transplanted MyoD−/− myoblasts have been reported to survive and engraft into MyoD+/+ regenerating muscles with improved efficacy (compared with wild-type myoblasts). This phenotype is reportedly due to their increased stem cell characteristics and repressed apoptotic potential (22, 231). After regeneration, these transplanted MyoD−/− myoblasts not only give rise to myonuclei but also contribute to the satellite cell pool (22). On the other hand, ectopic expression of MyoD in NIH-3T3 and C3H10T1/2 fibroblasts is sufficient to activate the complete myogenic program in these cells (234). Taken together, these observations indicate that expression of MyoD is an important determinant of myogenic differentiation, and in the absence of MyoD, activated myoblasts have a propensity for proliferation and self-renewal (452). In contrast to the MyoD−/− mice, Myf5−/− mutant mice show a myofiber hypertrophy phenotype (187), and the proliferation of Myf5−/− myoblasts is compromised (187, 542). Together, these results implicate a distinct role for Myf5 in adult myoblast proliferation, while MyoD is essential for differentiation. Notably, the disparate functions of Myf5 and MyoD in adult muscle regeneration parallel the proposed roles for these transcription factors throughout the development of distinct myogenic lineages during embryogenesis (188, 213, 256–259; reviewed in Ref. 260). Together, the aforementioned observations suggest a hypothesis that satellite cells enter different myogenic programs depending on whether Myf5 or MyoD expression predominates (450). Predominance of MyoD expression would drive the program toward early differentiation, as exemplified by the behavior of Myf5−/− myoblasts (349). In contrast, predominance of Myf5 expression would direct the program into enhanced proliferation and delayed differentiation, as shown by the behavior of MyoD−/− myoblasts (452). Finally, myoblasts coexpressing both Myf5 and MyoD would exhibit the intermediate growth and differentiation propensities as shown by most of satellite cell-derived myoblasts. This hypothesis is consistent with the observation that MyoD and Myf5 have different expression profiles throughout the cell cycle. MyoD expression peaks in mid G1, whereas Myf5 expression is maximal at the G0 and G2 phases of the cell cycle (273). Therefore, disruptions to the MyoD/Myf5 ratio may determine the choice of myogenic programs. This hypothesis also explains the spectrum of proliferation and differentiation potential observed in different primary myoblast clones cultured in vitro.

Several studies have revealed that MyoD expression in proliferating myoblasts is positively regulated by serum response factor (SRF), which binds to the serum response element (SRE) within the MyoD regulatory region (186, 285). In proliferating myoblasts, SRF only drives low levels of MyoD expression (286), whose activity is inhibited by cyclin D1 induced cyclin dependent kinase 4 (Cdk4) (587). However, the induction of MEF2 expression prior to differentiation enables MEF2 to out-compete SRF for the SRE binding site and leads to high levels of MyoD expression and initiation of differentiation (286). This function of MEF2 is further regulated by a member of the myocardin family of transcription factors, MASTR, whose expression is upregulated in response to muscle injury (348).

Notably, our group recently revealed a pro-proliferation function of MyoD in myoblasts (191). We found that the γ isoform of p38 kinase (p38γ) phosphorylates MyoD, which negates the transcriptional activation potential of MyoD and leads to a repressive MyoD complex occupying the Myogenin promoter (191). This positive effect of p38γ on myoblast proliferation is also supported by the observation that Myogenin is prematurely expressed in p38γ-deficient muscle, which displays markedly reduced myoblast proliferation (191). These results also support the notion that the functional state of MyoD depends on cofactors present in the MyoD transcriptional complex.

Moreover, multiple studies demonstrated that MyoD expression does not always warrant myogenic commitment. Monitoring satellite cell lineage progression revealed that some Pax7+/MyoD+ proliferating myoblasts could retract back to a Pax7+/MyoD− state and eventually return to quiescence (127, 216, 584; discussed in sect. IIC). In addition, the reciprocal inhibition of Pax7 with MRFs (MyoD and Myogenin) has been revealed in C3H10T1/2 fibroblasts and MM14 myoblasts in vitro (385). It was found that Pax7 decreases MyoD transcription activity and stability, whereas Myogenin represses Pax7 transcription likely via the HMGB1-RAGE axis (385, 438). Based on these observations, it was proposed that the ratio of Pax7 and MyoD activities are critical for satellite cell fate determination (385). A high ratio of Pax7 to MyoD (as seen in quiescent satellite cells) keeps satellite cells in their quiescent state. An intermediate ratio of Pax7 to MyoD allows satellite cells to proliferate, but not differentiate. Satellite cells with a low Pax7-to-MyoD ratio begin to differentiate, and further reduction in Pax7 levels are observed following activation of Myogenin.

After limited rounds of proliferation, the majority of satellite cells enter the myogenic differentiation program and begin to fuse to damaged myofibers or fuse to each other to form new myofibers. The initiation of terminal differentiation starts with the expression of Myogenin and Myf6 (also called Mrf4) (114, 116, 207, 497, 572). The induction of Myogenin expression primarily depends on MyoD and is proposed to enhance expression of a subset of genes previously initiated by MyoD (83). Target genes of MyoD and Myogenin have been revealed by candidate approaches (405), ChIP-on-chip experiments (44, 56, 83), and more recently by ChIP-Seq analysis (84). These investigations jointly reveal a convoluted hierarchical gene expression circuitry centered on MyoD and its immediate downstream targets: Myogenin and Mef2 transcription factors (Mef2s). Based on the temporal expression pattern of MyoD, Myogenin and Mef2s, a feed-forward regulatory circuit is proposed. In this hypothesis, myogenic differentiation is an irreversible procedure and is driven by the sequential expression of key transcription factors (master regulators), which are destined to transduce gene expression signals to their target genes (45, 405). A large portion of target genes induced by MyoD, Myogenin, and Mef2s are muscle-specific structural and contractile genes, such as those encoding actins, myosins, and troponins. The expression of these genes is essential for the proper formation, morphology, and function of skeletal muscle and thus they are regulated by multiple mechanisms (41).

First, the transcriptional activities of MyoD, Myogenin, and Mef2s are regulated by posttranscriptional modifications (reviewed in Ref. 420). The α and β isoforms of p38 kinase (p38-α/β) have an important role in the expression of muscle-specific genes (405) and in muscle terminal differentiation (571). The function of p38-α/β is at least partially responsible for the phosphorylation of Mef2s as inhibition of p38-α/β disrupts the transcriptional activities of Mef2s. In contrast, the expression of constitutively active forms of p38-α/β promotes myogenesis (117, 221, 390, 420, 571, 589). p38-α/β activity stimulates the binding of MyoD and Mef2s to the promoters of muscle-specific genes, leading to the recruitment of chromatin remodeling complexes, and ultimately the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme (405, 424, 491). Similarly, the transcriptional activity of Myogenin is regulated by protein kinase A (PKA) (308) and protein kinase C (PKC)(309). Protein inhibitors of MRFs also control myogenic gene expression. The transcriptional activity of MRFs relies on heterodimerization with E proteins (ITF1, ITF2, E12, E47) (291, 362, 363). This heterodimerization is negatively regulated by a group of inhibition of DNA binding proteins (Ids: Id1, Id2, Id3, and Id4), which are also helix-loop-helix proteins but lack the basic DNA-binding domain (42, 43). Id proteins heterodimerize with E proteins and prevent their association with MRFs, thus abrogating myogenic gene expression (43). Similar results occur when Mist1 directly interacts with MyoD and prevents MyoD from binding E-boxes (298). MyoD activity can be further inhibited by the sequestration of E proteins, by Twist (504). Finally, the transcriptional activity of MyoD is also determined by specific cofactors present on the promoters of myogenic genes (reviewed in Ref. 450). In vitro, MyoD associates with histone acetyltransferases (HATs) p300 and p300/CBP (CREB-binding protein)-associated factor (PCAF) on E-box motifs of its target genes (419). This association is presumed to induce histone acetylation and transcriptional activation (45). MyoD also interacts with histone deactylases (HDACs), which negatively regulate the transcriptional activity of MyoD either directly (325) or in a Mef2-dependent manner (319).

Besides MRFs and their regulators, other factors have been shown to be involved in myogenic differentiation. MicroRNAs are 20–22nt noncoding small RNAs, which function to repress translation and reduce the stability of their target mRNAs. Recent studies demonstrated that MRFs, such as Myf5, MyoD, and Myogenin, activate the expression of a collection of myogenic microRNAs (e.g., miR-1, miR-133, miR-206 together called MyomiRs). These myogenic microRNAs, in conjunction with other microRNAs, modulate the expression levels of key myogenic transcription factors and regulators, such as Pax3 (119, 196, 231), Pax7 (94, 139), SRF (93), c-Met (526, 577), and Dek (98) during satellite cell activation/proliferation and differentiation (also reviewed in Refs. 374, 565). Furthermore, recent studies have demonstrated the requirement for caspase-3 and its activation of CAD (caspase-activated DNase) in initiating myoblasts differentiation in vitro (164, 290). Activation of CAD by caspase-3 induces double-stranded DNA breaks (DSBs) in the genome and the association of CAD with various target promoters. One such promoter is the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor p21(Waf1/Cip1) which following binding by CAD is activated (290). MyoD also induces the expression of p21(Waf1/Cip1) (209, 215) and subsequent permanent cell cycle arrest. p21 is known to dephosphorylate the retinoblastoma protein (Rb) and cause the inactivation of the Rb-associated E2F family of transcription factors known to activate S-phase genes (reviewed in Ref. 559). Thus, through this pathway, MyoD induces permanent cell cycle withdrawal in myoblasts. Consistently, myoblasts in p21−/− mice are defective in cell cycle arrest and myotube formation, leading to increased apoptosis (555, 588). Similarly, Rb-deficient myoblasts cannot complete cell cycle withdrawal and arrest during both S and G2 phases of the cell cycle (378).

After exiting the cell cycle, myogenic cells undergo cell-to-cell fusion to repair damaged myofibers or form nascent multinucleated myofibers. The cellular events in this complex process have been extensively studied (274, 312, 418, 428, 553). Akin to embryonic myogenesis, de novo formation of myofibers during muscle regeneration happens in two stages. In the first stage, individual differentiated myoblasts fuse to one another and generate nascent myotubes with few nuclei. In the second phase, additional myoblasts incorporate into the nascent myotubes, forming a mature myofiber with increased size and expression of contractile proteins. In recent years, studies in myoblast fusion in vitro have identified a cadre of cell surface, extracellular, and intracellular molecules, which are important for these two stages of myogenic cell fusion (reviewed in Ref. 238). For example, cell membrane proteins β1-integrin (474), VLA-4 integrin (445), integrin receptor V-CAM (445), caveolin-3 (180), and transcription factor FKHR (Forkhead in human rhabdomyosarcoma, also called FOXO1a) have been shown to act in myoblast-to-myoblast fusion. Whereas the cytokine IL-4 (238) and calcium and calmodulin activated NFATC2 (nuclear factor of activated T cell isoforms C2) pathway (237) is critical for the fusion of myoblasts with nascent myotubes.

As discussed here, activation of satellite cells following muscle injury results in the expansion of the myogenic cell pool and leads to the initiation of the myogenic program. This program, orchestrated by key transcription factors, dictates the balance between proliferation and differentiation and drives the functional transformation from individual proliferating myogenic cells to a syncytial contractile myofiber. Although numerous studies have shed light on this complex process, there are still many interesting questions that remain to be answered. For example, what are the intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms that determine the scale of satellite cell proliferation in vivo, which essentially generate sufficient but not excessive numbers of myogenic cells for muscle regeneration? Similarly, what mechanisms regulate the magnitude of muscle regeneration in response to variable levels of damage and eventually prevent muscle atrophy or hypertrophy? With the recent advances in high-throughput sequencing and system biology, is it possible to elucidate a core regulatory network of myogenic gene expression and employ such knowledge on directing myogenic determination and differentiation from multipotent cells? The answers to these questions will improve our understanding of muscle regeneration and facilitate future development of therapeutic approaches to cure muscle diseases.

C. Satellite Cell Self-Renewal

A hallmark of stem cells is the ability to self-renew. Stem cells can divide and self-renew in two fashions: asymmetric cell division and symmetric cell division. In asymmetric cell division, one parental stem cell gives rise to two functionally different daughter cells: one daughter stem cell and another daughter cell destined for differentiation. In symmetric cell division, one parental stem cell divides into two daughter stem cells of equal stemness. In either fashion, the number of stem cells is maintained at a constant level. Stem cell self-renewal by asymmetric cell division is exemplified by neuronal stem cells (590). Stem cell self-renewal by symmetric cell division is frequently observed in hematopoietic stem cells and mammalian male germline stem cells (spermatogonia) (570).

The self-renewing capability of satellite cells is clearly demonstrated by their remarkable ability to sustain the capacity of muscle to regenerate. For example, in a single myofiber transplantation experiment (105), 7–22 satellite cells together with their intact myofibers were transplanted into irradiated muscles of immunodeficient dystrophic (scid-mdx) mice. It was found that one grafted myofiber can give rise to over 100 new myofibers, which contain ∼25,000–30,000 differentiated myonuclei. In addition, the grafted satellite cells can undergo a 10-fold expansion via self-renewal. The expanded satellite cells are functional as they can be activated and support further rounds of muscle regeneration (105). Similarly, the self-renewing capability of satellite cells was further proven by single satellite cell transplantation experiments (454). In this study, single Lin−/α7-integrin+/CD34+ cells freshly isolated by FACS were transplanted into irradiated muscles of scid-mdx mice. It was observed that progeny from these single cells not only generated myofibers, but also migrated to the satellite cell niche and persisted in host muscles (454).

An intriguing question is how satellite cells renew themselves. By using the Cre-LoxP based permanent lineage tracing technique (Myf5Cre;R26R-loxP-stop-loxP-YFP), our group first demonstrated that satellite cells can undergo both asymmetric and symmetric divisions within their natural niche environment in mildly damaged EDL muscle (280). The choice of asymmetric versus symmetric division is largely correlated to the mitotic spindle orientation relative to the longitude axis of the myofiber. Asymmetric divisions are only observed for Pax7+/Myf5− satellite cells, which give rise to one satellite stem cell (Pax7+/Myf5−) and one satellite myogenic (Pax7+/Myf5+) cell. Asymmetric division predominantly happens when the mitotic spindle is perpendicular to the myofiber axis (apical-basal division) with the satellite stem cell (Pax7+/Myf5−) in close contact with the basal lamina (basal) and the Pax7+/Myf5+ satellite myogenic cell adjacent to the myofiber plasma membrane (apical). Occasionally, it was observed that Pax7 expression is dampened in the apical satellite cell, suggesting a progression towards terminal differentiation. Furthermore, the asymmetric nature of this kind of division is also underscored by the observation that the apical Pax7+/Myf5+ cells express higher levels of the Notch ligand Delta-1, whereas the basal Pax7+/Myf5− satellite cells express higher levels of the Notch-3 receptor. Symmetric divisions were observed for both Pax7+/Myf5− satellite cells and Pax7+/Myf5+ satellite cells and in either case the mitotic spindle was frequently parallel to the myofiber axis (planar division) and both daughter cells were in contact with the myofiber plasma membrane and the basal lamina.

When both satellite stem cells and satellite myogenic cells are freshly sorted and transplanted into Pax7−/− muscles lacking any functional endogenous satellite cell, both cell types can colonize the host muscle. However, only Pax7+/Myf5− satellite cells can efficiently reconstitute the satellite cell compartment (∼7-fold more efficient than Pax7+/Myf5+). These observations indicate that Pax7+/Myf5− satellite cells represent a bona fide stem cell population, which can undergo self-renewal by both asymmetric division and symmetric division (280).

Although asymmetric self-renewal may be sufficient under physiological conditions, satellite stem cells may favor symmetric self-renewal divisions to replenish and expand their population in response to acute need for a large number of satellite cells after injury or disease state (354). Indeed, it was observed that Pax7+/Myf5− satellite stem cells represent ∼10% of total satellite cells in intact muscles, whereas this percentage increases to ∼30% at 3 wk after injury (280). In search of intrinsic and extrinsic cues regulating Pax7+/Myf5− satellite stem cell self-renewal, our group further revealed that symmetric self-renewal is promoted by a niche factor, Wnt7a, during muscle regeneration (293; discussed in sect. IIIA1a). Therefore, the mode of satellite cell self-renewal is governed by the satellite cell niche.

With regards to activated satellite cells returning to quiescence, observations on the dynamic expression of Pax7, MyoD, and Myogenin in ex vivo cultured single myofibers suggest it is possible (127, 216, 584). After myofiber isolation (the isolation procedure per se is a form of injury to initiate muscle regeneration), satellite cells are activated and rapidly start to express MyoD (572, 584). It has been observed that almost all myoblasts express MyoD after ∼24 h of in vitro culture (584). While most of these proliferating Pax7+/MyoD+ myoblasts differentiate into Pax7−/MyoD+/Myogenin+ cells after 72 h of culture, some Pax7+/MyoD+ myoblasts (also called reserve cells) nonetheless have been observed to repress MyoD expression and maintain Pax7 expression and eventually withdraw from the cell cycle (216, 584). These Pax7+/MyoD− satellite cells acquired the quiescence marker Nestin, albeit at a much later (3–4 wk in culture) stage (127). These observations suggest that quiescent satellite cells renew by lineage regression from committed myogenic cells at least in vitro, and this renewal may be promoted by Pax7 (584). In addition, the capability of activated satellite cells to generate reserve cells may be an important mechanism to maintain the size of the satellite cell pool, as reduction of such capability was suggested to lead to decreased numbers of satellite cells with age (128). Intriguingly, this lineage regression has also been recently observed in vivo (482). Sprouty-1, a negative regulator of receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) signaling, plays a critical role in satellite cell renewal (482). Sprouty-1 is expressed in quiescent but not proliferating satellite cells (177, 482). Upon injury, released fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) act through the RTK/ERK pathway to stimulate satellite cell proliferation (482). Most satellite cells entered the cell cycle during regeneration as indicated by BrdU labeling. It was confirmed that some satellite cell-derived myogenic progenitors withdrew from the cell cycle, returned to the satellite cell compartment, and regained Sprouty-1 expression, indicative of satellite cell renewal in vivo. In the absence of Sprouty-1, it was observed that satellite cell-derived myogenic progenitors proliferate and differentiate normally, but markedly reduced numbers of satellite cells exist after regeneration. Further investigations revealed that Sprouty-1 is required only for a distinct subset of myogenic progenitors to return to their quiescence state (482). These results indicate that Sprouty-1 is essential for some satellite cells to regain quiescence following regeneration. The function of Sprouty-1 in this process is most likely due to its inhibitory effect on the ERK pathway and subsequent enhanced cell cycle withdrawal. It should be stressed that this renewal of satellite cells at a population level and the aforementioned self-renewal of satellite cells at a single-cell level are not mutually exclusive but rather represent two different perspectives of the same regeneration process. Future studies are needed to identify the essential differences between Sprouty-1-dependent and Sprouty-1-independent populations and understand whether these differences reflect any other functional distinction. In addition, it would be interesting to investigate the regulatory mechanisms governing Sprouty-1 expression, for example, whether the reappearance of Sprouty-1 is regulated by Pax7 or Wnt signaling.

D. Contributions and Therapeutic Potential of Nonsatellite Cells in Trauma-Induced Muscle Regeneration

1. Bone marrow stem cells