Abstract

Long-term potentiation (LTP) of excitatory afferents to the dorsal striatum likely occurs with learning to encode new skills and habits, yet corticostriatal LTP is challenging to evoke reliably in brain slice under physiological conditions. Here we test the hypothesis that stimulating striatal afferents with theta-burst timing, similar to recently reported in vivo temporal patterns corresponding to learning, evokes LTP. Recording from adult mouse brain slice extracellularly in 1 mM Mg2+, we find LTP in dorsomedial and dorsolateral striatum is preferentially evoked by certain theta-burst patterns. In particular, we demonstrate that greater LTP is produced using moderate intraburst and high theta-range frequencies, and that pauses separating bursts of stimuli are critical for LTP induction. By altering temporal pattern alone, we illustrate the importance of burst-patterning for LTP induction and demonstrate that corticostriatal long-term depression is evoked in the same preparation. In accord with prior studies, LTP is greatest in dorsomedial striatum and relies on N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors. We also demonstrate a requirement for both Gq- and Gs/olf-coupled pathways, as well as several kinases associated with memory storage: PKC, PKA, and ERK. Our data build on previous reports of activity-directed plasticity by identifying effective values for distinct temporal parameters in variants of theta-burst LTP induction paradigms. We conclude that those variants which best match reports of striatal activity during learning behavior are most successful in evoking dorsal striatal LTP in adult brain slice without altering artificial cerebrospinal fluid. Future application of this approach will enable diverse investigations of plasticity serving striatal-based learning.

Keywords: LTP, striatum, theta, plasticity, learning

the dorsal striatum hosts an intersection of cognitive, limbic, motor, and reward systems which combine to impart neural changes underlying learning. Striatal activity is critical for instrumental learning (Graybiel 1995; Yin et al. 2005), motor skill development (Yin et al. 2009), cued action-selection (Packard and Teather 1997), and habit formation (Yin and Knowlton 2006). Distinct types and stages of learning differ in their engagement of medial and lateral dorsal striatal regions (Pauli et al. 2012; Yin et al. 2006). Observations in vivo and ex vivo suggest that changes in strength of connection between neurons underlie striatal learning and memory (Koralek et al. 2012; Pascoli et al. 2011; Pauli et al. 2012; Shen et al. 2011; Yin et al. 2009). Stimulation of glutamatergic and dopaminergic afferents to dorsal striatum leads to in vivo corticostriatal long-term potentiation (LTP), the strength of which correlates with learning speed (Charpier et al. 1999; Reynolds et al. 2001). Rotarod training reduces long-term depression (LTD) ex vivo in the dorsal striatum (Yin et al. 2009). Despite its importance in learning and memory, investigation of mechanisms underlying information storage in dorsal striatum has been limited by the difficulty in evoking reliable, long-lasting LTP in striatal brain slice under physiological conditions.

Consistency in predictably evoking unidirectional plasticity (either LTP or LTD) ex vivo is no doubt complicated by regional variation in striatal tissue composition mixed with disparity in experimental approach (Kreitzer and Malenka 2008; Reynolds and Wickens 2002). Two generally consistent approaches taken to evoke activity-dependent ex vivo corticostriatal plasticity are high-frequency stimulation (HFS) and spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP). Corticostriatal HFS typically evokes LTD in normal Mg2+ artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) (Kreitzer and Malenka 2005; Lovinger et al. 1993b; Walsh 1993; Xia et al. 2006), although it has also been reported to evoke plasticity of mixed direction (Akopian et al. 2000; Akopian and Walsh 2006; Spencer and Murphy 2000). The same HFS reliably evokes corticostriatal LTP in the absence of Mg2+, an ion natively conveying N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor voltage dependence (Arbuthnott et al. 2000; Calabresi et al. 1992b; Guan et al. 2010; Kerr and Wickens 2001). Drawbacks to HFS include use of unrealistically high frequencies for striatum and use of 0 Mg2+ which nullifies NMDA receptors as voltage-sensitive coincidence detectors, potentially blunting temporal sensitivity in calcium influx. STDP protocols employ lower, more reasonable frequencies to pair postsynaptic action potentials with precisely timed presynaptic stimulation in normal Mg2+, and in these regards STDP is more physiological than HFS. STDP can be used to evoke LTP or LTD as desired based on the relative timing of activity across the synapse (Fino et al. 2005) and whether GABAA receptors are blocked (Fino et al. 2010; Paille et al. 2013), but, as with HFS stimulation, STDP LTP is not consistently observed (Shindou et al. 2011). Because diverse induction paradigms invoke plasticity by way of distinct molecular mechanisms (Asrar et al. 2009; Lerner and Kreitzer 2012; Petersen et al. 2003; Ronesi and Lovinger 2004), it would be ideal to use normal magnesium solutions in combination with physiological, learning-like activity to induce long-lasting plasticity for the purpose of examining subcellular learning mechanisms.

Electrical recordings in vivo reveal associations between patterned neural activity in various brain regions and behavior. In hippocampus and striatum, activity at theta frequencies (5–11 Hz) is modulated with learning (Tort et al. 2008). For instance, in the dorsal striatum of behaving animals, neuron firing aligns more strongly to a theta rhythm during salient task points such as initiation, completion, and decision-making moments (DeCoteau et al. 2007; Tort et al. 2008). Theta-burst stimulation (TBS), which mimics a normal pattern of hippocampal activity, induces a robust LTP in hippocampal area CA1 (Abraham and Huggett 1997; Larson and Lynch 1986). The success of TBS to induced LTP in the hippocampus, together with the emergence of theta-rhythms in dorsal striatum during learning, suggests that similar protocols may induce physiologically realistic LTP in ex vivo striatum. In this study, we test the hypothesis that learning-related temporal patterns, in the form of TBS, will induce long-lasting striatal LTP. We find that delivering stimuli in physiological bursts at a behaviorally relevant theta-range frequency induces late-phase striatal LTP in adult tissue without altering ionic composition, and we identify molecular effectors serving striatal theta-burst LTP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All animal handling and procedures were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health animal welfare guidelines and were approved by the George Mason University IACUC. Male C57BL/6 mice (2–5 mo) were decapitated while anesthetized using isoflurane. Brains were extracted into ice-cold, oxygenated slicing solution (in mM: KCl 2.8, dextrose 10, NaHCO3 26.2, NaH2PO4 1.25, CaCl2 0.5, Mg2SO4 7, sucrose 210) and coronally sectioned at 350 μm using a vibratome (Leica VT 1000S). Slices were collected anterior to, and including the level of, the anterior commissure. Slices were bisected by hemisphere and placed in an incubation chamber containing aCSF (in mM: NaCl 126, NaH2PO4 1.25, KCl 2.8, CaCl2 2, Mg2SO4 1, NaHCO3 26.2, dextrose 11) at 33°C for 30 min, then removed to room temperature (21–24°C) for at least 90 min before use. All experiments used aCSF containing 1 mM Mg2+.

Hemislice pairs were transferred to a submersion recording chamber (Warner Instruments) perfused with oxygenated aCSF (30–32°C) containing 50 μM picrotoxin at 2.5–3 ml/min. Pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass (Sutter P-2000) and filled with aCSF (resistance 3–6 MΩ). Raw data were recorded using an intracellular electrometer (IE-251A, Warner Instruments) and four-pole Bessel filter (Warner Instruments), sampled at 20 kHz and processed using a PCI-6251 and LabView (National Instruments). Population spikes were evoked by stimulating white matter overlaying striatum with a tungsten bipolar electrode at an intensity producing 40–60% of the peak signal amplitude on an input-output curve. In most recordings, the synaptically-evoked striatal population spike (N2) was preceded by a downward voltage deflection (N1), indicating afferent depolarization by applied current (Malenka and Kocsis 1988; Takag and Yamamoto 1978). Experiments in which N1 varied by more than 20% from baseline at any point in an experiment were excluded, and post hoc analysis of the optimal TBS group (50-Hz burst and 10.5 theta) shows no correlation between normalized N1 and N2 values 120 min postinduction (R2 = 0.058); thus, for analyzed experiments, change in population spike amplitude is not attributable to change in N1. Significant increase or decrease in population spike amplitude relative to average baseline amplitude indicates LTP or LTD, respectively. Population spikes were sampled at 0.033 Hz before and after induction. Population spike amplitude was extracted automatically from raw data using the software IGOR. Forty milliseconds of raw data are saved surrounding each test-pulse, within which the most negative voltage following the stimulation artifact is subtracted from the more positive of the following two features: either 1) mean voltage averaged over 1 ms immediately preceding the stimulation artifact, or else 2) the upward going peak dividing N1 and N2, as described in Lovinger et al. (1993a). The absolute value of this difference defines the population spike amplitude. During automated amplitude extraction, traces from each experiment were graphically displayed to be reviewed by eye, guarding against errors in data extraction.

All induction paradigms were matched in delivering a total of 400 stimuli (Fig. 1A). TBS consisted of 10 trains, each delivering 10 bursts of 4 stimuli. The “intraburst” parameter defined the frequency of stimuli within bursts and was set to either 50 Hz or 100 Hz. The “theta” parameter defined the frequency of bursts within trains and was set to 5 Hz, 8 Hz, or 10.5 Hz. Nonbursty stimulation consisted of 10 trains, each delivering 40 stimuli at 50 Hz. The intertrain interval for TBS and nonbursty stimulation was 15 s; thus the induction period lasted ∼2.5 min for both TBS and nonbursty stimulation. HFS consisted of 4 trains of 100 stimuli delivered at 100 Hz. Moderate-frequency stimulation (20 Hz) consisted of 4 trains of 100 stimuli delivered at 20 Hz. The intertrain interval for HFS and 20 Hz was 10 s. Thus the HFS induction required 34 s, and the 20 Hz induction required 50 s.

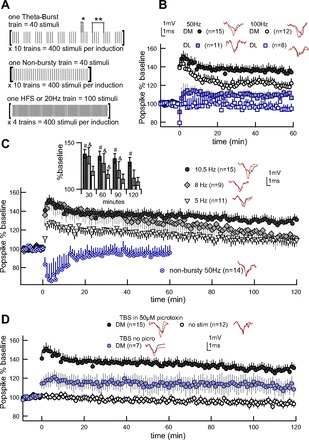

Fig. 1.

Long-term potentiation (LTP) depends on intraburst and theta-burst timing. Example traces from end of experiment (red) overlay traces from baseline (gray) in the insets. Error bars represent ± SEM. A: schematic of induction variants. For each induction paradigm employed in this paper, a single train of stimuli is illustrated in brackets and annotated to show stimuli number is matched across conditions. Theta-burst (*intraburst period, **theta period) and nonbursty trains (50 Hz) are delivered with a 15-s intertrain interval. High-frequency stimulation (HFS) (100 Hz) and 20-Hz trains are delivered with a 10-s intertrain interval. B: intraburst frequency of 50 Hz is more effective than 100 Hz, both dorsomedial (DM) and dorsolateral (DL). Theta-burst frequency is 10.5 Hz for all groups. C: burst timing is critical to LTP. Theta-burst frequency of 10.5 Hz produces stronger, longer-lasting potentiation than 5 or 8 Hz in DM striatum. Bar graph indicates difference from nonstimulated controls at significance of #P < 0.0001 or &P < 0.05. In the nonbursty condition, the 40 stimuli within each train are delivered at a constant 50 Hz, and neither LTP nor long-term depression (LTD) results. Nonbursty experiments ended at 60 min, since long-term plasticity was not induced. D: picrotoxin decreases but does not eliminate induction of LTP using the optimal theta-burst timing of 50-Hz intraburst and 10.5-Hz interburst. TBS, theta-burst stimulation.

In pharmacology experiments, TBS was delivered to one hemislice, and the other served as a nonstimulated control for nonspecific drug effects on signal size. Drugs were bath applied at least 20 min prior to induction and maintained throughout experiments. Salts were purchased from Fisher Scientific. Picrotoxin, chelerythrine chloride, PKI(14–22) amide, telenzepine dihydrochloride, and (RS)-1-aminoindan-1,5-dicarboxylic acid (AIDA) were purchased from Tocris Bioscience, and both 2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (APV) and SCH23390 were purchased from Enzo Life Science. All drugs were water soluble. Picrotoxin was weighed as a powder and added to aCSF daily as needed, while all other drugs were dissolved in water and stored in concentrated aliquots to be added to aCSF as needed.

Raw data analysis and figures were made in IGOR and statistical analysis utilized SAS (version 9.2) using the procedure GLM (general linear models); post hoc tests used LSmeans with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons. Statistical analysis was performed on the population spike amplitude averaged over a 10-min interval surrounding every 30-min increment recorded postinduction and normalized to the prestimulated baseline. Percent change from baseline is reported ± SEM. For graphs and statistical analysis, n is number of experiments, with not more than one experiment per slice, and not more than two identical treatments collected from the same animal.

RESULTS

Corticostriatal LTP is improved by approximating physiological frequencies.

Using field recordings in the dorsal striatum, we examined the efficacy of TBS paradigms to induce corticostriatal LTP in dorsomedial (DM) and dorsolateral (DL) striatum in adult mouse brain slice bathed in aCSF containing physiological Mg2+ (1 mM). GABAA activity was consistently blocked to isolate the striatal response to glutamatergic synapses. Distinct protocols to be compared were administered to neighboring coronal hemislices in a common chamber. Two temporal features of the induction pattern were varied: intraburst frequency and theta-burst frequency (Fig. 1A).

Intraburst frequencies of 50 and 100 Hz were compared while maintaining 10.5-Hz theta frequency. Our results indicate that 50-Hz intraburst produces stronger LTP than 100 Hz in both DM and DL regions (Fig. 1B). Both 50 and 100 Hz produced a significant LTP compared with nonstimulated controls. Statistical analysis of the results (Table 1) using repeated-measures GLM shows that 50-Hz LTP was significantly better than 100 Hz, with 50 Hz producing larger and longer lasting LTP than 100 Hz, and DM striatum supporting stronger potentiation than DL [at 60 min: intraburst F(2,57) = 11.55, P < 0.0001; region F(1,57) = 10.07, P = 0.003]. The more pronounced 50-Hz LTP was recorded out to 120 min (see Fig. 1C), by which time DM striatum was potentiated 129 ± 5% and differed significantly from nonstimulated controls (93%), while DL striatum, at 106 ± 4%, did not (data not shown) [at 120 min: GLM on intraburst F(2,37) = 21.37, P < 0.0001; LSmeans vs. nonstimulated controls: DM P < 0.0001, DL P = 0.1]. Since DM LTP was stronger than DL LTP, we subsequently focused on the DM striatum, using the more effective 50-Hz intraburst frequency.

Table 1.

Plasticity by region and induction variant

| Region | Intraburst, Hz | Theta, Hz | Four Train, Hz | %Baseline 60 min | %Baseline 120 min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DM/L† | 95 ± 3 | 93 ± 4 | |||

| DM | 50 | 10.5 | 135 ± 5 | 129 ± 5 | |

| DM | 100 | 10.5 | 119 ± 4 | ||

| DL | 50 | 10.5 | 110 ± 4 | 106 ± 4 | |

| DL | 100 | 10.5 | 95 ± 4 | ||

| DM | 50 | 8 | 128 ± 10 | 112 ± 9 | |

| DM | 50 | 5 | 116 ± 5 | 108 ± 4 | |

| DM | 50‡ | 10.5‡ | 114 ± 9 | 110 ± 7 | |

| DM | 50* | 12.5* | 97 ± 7 | ||

| DM | 100 | 109 ± 6 | |||

| DM | 20 | 80 ± 7 | |||

| DL | 100 | 96 ± 6 | |||

| DL | 20 | 68 ± 5 |

Values are means ± SE. DM, dorsomedial; DL, dorsolateral.

Nonstimulated controls. These did not differ regionally; thus DM and DL controls were pooled for analysis.

No picrotoxin was used. 50 μM picrotoxin is present under all other conditions.

The nonbursty induction variant.

Working in the DM striatum, we tested the effect of three different frequencies spanning the theta range (5–11 Hz): 5 Hz, 8 Hz, and 10.5 Hz. Repeated-measures GLM shows significant effects of theta frequency [F(3,46) = 10, P < 0.0001 at 120 min] and time [F(3,96) = 23.25, P < 0.0001] with higher theta frequencies inducing the greatest and longest lasting potentiation (Fig. 1C). Post hoc analysis indicates that the 10.5-Hz group, which produced late-phase LTP by maintaining 129 ± 5% potentiation 120 min postinduction, differs significantly from nonstimulated controls (LSmeans vs. controls, P < 0.0001). The same analysis reveals that LTP evoked by 8-Hz theta is not well maintained, losing significance by 120 min (at 60 min: 128 ± 10%, P = 0.001; at 120 min: 112 ± 9%, P = 0.05), and that the small LTP evoked by 5-Hz theta (at 60 min: 116 ± 5%, P = 0.04) has dissipated by 120 min (108 ± 4%, P = 0.13). These differences in LTP strength cannot be attributed to different initial amplitude, as average baseline population spike amplitude did not differ among the four DM theta-burst paradigms and nonstimulated controls [GLM, F(4,77) = 1.49, P = 0.21]. In summary, the optimal TBS (50 Hz intraburst; 10.5 Hz theta) is the only protocol that produces a long-lasting LTP and thus is used for the remainder of our investigations.

Burstiness is critical to striatal TBS LTP.

We find that lower intraburst and higher theta frequencies are more effective for LTP induction; however, as theta frequency increases, the pause separating bursts is reduced. We therefore tested the importance of burst-patterning by eliminating the theta component of our induction protocol by decreasing the interburst pause from 35 ms (using the optimal 10.5-Hz theta) to 20 ms. In other words, we delivered trains of stimuli at an unbroken 50 Hz in a “nonbursty” induction variant in which train number, intertrain interval, and the number of stimuli delivered remained matched to TBS protocols (Fig. 1A). Despite close temporal similarity to the optimal TBS, the nonbursty stimulation failed to evoke LTP (Fig. 1C, Table 1). Statistical analysis implicates burstiness as a significant factor contributing to LTP induction [repeated-measures GLM, F(2,34) = 13.89, P < 0.0001]. Post hoc analysis indicates significant difference between TBS and nonbursty groups (LSmeans, P < 0.05) and no difference between nonbursty stimulation and nonstimulated controls (LSmeans, P > 0.05). The 35-ms pause between bursts when using the optimal 10.5-Hz theta frequency provides a mere 15-ms increase relative to the 20-ms break dividing 50-Hz stimuli within nonbursty trains. Our data identify this brief pause as a critical feature enabling long-lasting TBS LTP.

TBS LTP is present, although less consistent, when GABAA inputs remain active.

To isolate the contribution of glutamatergic synapses onto medium spiny neurons, TBS optimization was carried out in 50 μM picrotoxin, eliminating GABAergic interneuron and medium spiny collateral influence. Thus, to assess the effect of GABAergic inputs on TBS-induced synaptic plasticity, the optimal TBS was administered to the DM striatum as before, but picrotoxin was omitted from the aCSF. In the absence of picrotoxin, the net effect of TBS remains LTP (Fig. 1D, Table 1). On average, population response following TBS in the absence of picrotoxin remained larger than nonstimulated controls [GLM, F(1,18) = 4.59, TBS without picrotoxin at 60 min: 114 ± 9% vs. controls 95 ± 3%, P = 0.02; TBS without picrotoxin at 120 min: 110 ± 7% vs. controls 93 ± 4%, P = 0.01]. However, isolation of glutamatergic influence on medium spiny neurons using picrotoxin improves consistency in TBS-evoked LTP; therefore, picrotoxin was used in all subsequent investigations.

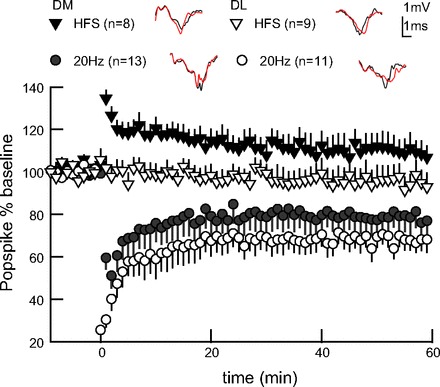

Bidirectional plasticity is obtained through temporal pattern.

We tested the ability of our preparation to express bidirectional plasticity to validate the utility of our theta-burst paradigm for evaluating how temporal pattern influences plasticity. First, we applied HFS (see Fig. 1A) commonly used to induce corticostriatal LTD in the presence of Mg2+ (Lerner and Kreitzer 2011), although in some instances it evokes LTP (Fino et al. 2005) or variable plasticity (Akopian et al. 2000; Akopian and Walsh 2006; Spencer and Murphy 2000). Applying the HFS protocol, we induced a small, transient increase in signal size dorsomedially (Fig. 2, Table 1) and induced no plasticity dorsolaterally (Fig. 2, Table 1). A variant of this protocol in which stimulation intensity during HFS is increased produced a similar result (data not shown). In summary, HFS did not produce a significant difference from nonstimulated controls at 30 min [GLM, F(1,29) = 0.01, P = 0.93].

Fig. 2.

LTD confirms bidirectional plasticity in adult dorsal striatal slice. Four trains of moderate-frequency stimulation (20 Hz), but not HFS (100 Hz), evokes LTD, both DM and DL. Example traces from end of experiment (red) overlay baseline traces (gray). Error bars represent ± SEM.

Next we evaluated a more moderate frequency induction paradigm, as this has shown success in promoting striatal LTD (Lerner and Kreitzer 2012; Ronesi and Lovinger 2004). In both striatal regions, we delivered pulses in the same four-train structure as HFS, but employed a moderate 20-Hz frequency within trains (see Fig. 1A). Four trains of 20 Hz evoked LTD, with DL showing greater LTD than DM striatum [Fig. 2; repeated-measures GLM, F(2,49) = 16.46, region P = 0.03, stimulation P < 0.0001]. The ability of the 20-Hz stimulation to evoke LTD dorsomedially demonstrates the capacity of our adult tissue preparation to reliably display LTD, as well as LTP, through manipulation of temporal pattern alone.

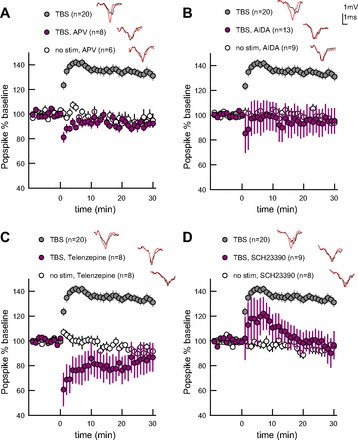

Theta-burst LTP requires NMDA and Gq- and Gs/olf-coupled receptors.

Collaborative signaling by neurotransmitters glutamate, acetylcholine, and dopamine is critical to striatal learning and plasticity (Lerner and Kreitzer 2011). Glutamate at active NMDA receptors provides calcium influx supporting learning and LTP. Metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR) on medium spiny neurons have demonstrated involvement in LTP using 0 Mg2+ HFS (Gubellini et al. 2003). Theta-burst may optimize acetylcholine release (Zhang et al. 2010), potentially activating Gq-coupled signaling pathways in common with mGluR (Calabresi et al. 1998, 1999). Dopamine acting at Gs/olf-coupled D1-type (D1 and D5) dopamine receptors is critical to LTP in both populations of medium spiny neurons (Kerr and Wickens 2001; Pawlak and Kerr 2008). We bath applied antagonists specific to these receptors to evaluate their role in TBS LTP. Simultaneous recordings from paired hemislices, one nonstimulated and one TBS stimulated, controlled for nonspecific drug effects. A contemporaneously interleaved cohort of drug-free TBS (50 Hz intraburst, 10.5 Hz theta) is used for comparison.

Figure 3 illustrates the effects of receptor antagonists on TBS-induced plasticity. The NMDA-type glutamate receptor antagonist APV (50 μM) fully prevents TBS LTP [Fig. 3A, Table. 2; GLM, F(2,33) = 48.85, P < 0.0001], confirming a requirement for NMDA receptor activation. Next, we independently block m1 type metabotropic acetylcholine (m1 AChR) and group I glutamate (mGluR1/5) receptors. Both the m1 AChR antagonist AIDA (100 μM) and mGluR1/5 antagonist telenzepine (300 nM) individually abolish TBS LTP without affecting unstimulated control slices [Fig. 3, B and C, Table 2; AIDA: GLM, F(2,41) = 14.04, P < 0.0001; telenzepine: GLM, F(2,35) = 28.93, P < 0.0001]. This suggests that Gq activation is needed through both glutamate and acetylcholine, as neither is sufficient to support TBS LTP alone. Bath application of an antagonist selective for Gs/olf-coupled dopamine receptors, SCH23390 (10 μM), abolishes TBS LTP by 30 min without affecting unstimulated control slices [Fig. 3D, Table 2; SCH23390: GLM, F(2,36) = 26.02, P < 0.0001], confirming a requirement for dopamine activation of Gs/olf-coupled pathways. Post hoc analysis for each of the above antagonists shows no difference in population spike amplitude over time between nonstimulated and TBS-treated slices in the presence of drug (LSmeans, P > 0.9). These results confirm that TBS LTP shares receptor dependence with striatal learning and established plasticity.

Fig. 3.

TBS LTP requires N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), group I metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR), m1 metabotropic acetylcholine receptors (AChR), and dopamine D1-type receptors. The drug-free TBS group (DM, 50 Hz intraburst, 10.5 Hz theta) was collected interleaved with pharmacology experiments and thus is different than the analogous TBS group in Fig 2. Example traces from end of experiment (red) overlay baseline traces (gray). Error bars represent ± SEM. A: NMDA receptor antagonist 2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (APV) blocks LTP. B: group I mGluR antagonist (RS)-1-aminoindan-1,5-dicarboxylic acid (AIDA) blocks LTP. C: m1 AChR antagonist telenzepine blocks LTP. D: D1-type dopamine receptor antagonist SCH23390 blocks LTP.

Table 2.

Pharmacology indicating LTP effectors

| Drug Name | Inhibits | %Baseline 30 min, TBS | %Baseline 30 min, No Stimulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| APV | NMDA receptor | 91 ± 2 | 95 ± 4 |

| AIDA | Group I mGluR | 95 ± 10 | 96.3 ± 6 |

| Telenzepine | m1 receptor | 85 ± 12 | 92 ± 4 |

| SCH23990 | D1/5 receptor | 97 ± 6 | 94 ± 3 |

| CHE | PKC | 92 ± 10 | 89 ± 4 |

| PKI | PKA | 105 ± 8 | 92 ± 4 |

| CHE+PKI | PKC and PKA | 86 ± 15 | 93 ± 7 |

| U-0126 | ERK | 97 ± 9 | 101 ± 6 |

Values are means ± SE. See text for definition of acronyms.

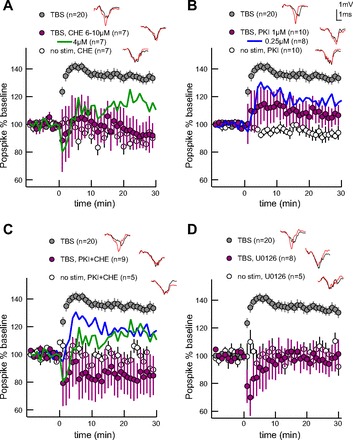

Theta-burst LTP requires PKC, PKA, and ERK.

Next we tested several kinases downstream of these implicated receptors to identify further effectors serving TBS LTP. The combination of NMDA-derived calcium and Gq-signaling creates the potential for activating protein kinase C (PKC), a kinase which may serve striatal LTP (Calabresi et al. 1998; Gubellini et al. 2004). Gs/olf-signaling elevates cAMP and activates protein kinase A (PKA), a second kinase with a likely role in striatal LTP (Spencer and Murphy 2002). Extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) is a kinase activated downstream of either PKC or PKA and has important roles in memory, drug addiction, and long-lasting plasticity (Mazzucchelli et al. 2002; Shiflett and Balleine 2011). We bath applied antagonists to these kinases during TBS experiments, again recording from paired hemislices, one nonstimulated and one TBS stimulated, to control for nonspecific drug effects.

Figure 4 illustrates the effects of kinase antagonists on TBS-induced plasticity. Bath-applied PKC antagonist, chelerythrine (6–10 μM), significantly reduces TBS LTP without affecting unstimulated control slices [Fig. 4A, Table 2; GLM, F(2,33) = 37.27, P < 0.0001]. Similarly, bath-applied cell-permeant PKA inhibitor peptide, PKI (1 μM), significantly reduces TBS LTP without affecting unstimulated control slices [Fig. 4B, Table 2; GLM, F(2,39) = 25.28, P < 0.0001]. Since PKI did not completely block LTP, we evaluated its effect in combination with chelerythrine. We used reduced concentrations of both antagonists, each showing reduced efficacy to block LTP (Fig. 4; reduced chelerythrine at 30 min: 114 ± 10; reduced PKI at 30 min: 117 ± 10). This reduced concentration combination fully prevents TBS LTP [Fig. 4C, Table 2; GLM, F(2,33) = 15.31, P < 0.0001], demonstrating that PKC and PKA cooperatively support striatal LTP. Bath-applied MAPK/ERK kinase (MEK) inhibitor U-0126 (30 μM) prevents MEK from activating ERK and fully blocks TBS LTP [Fig. 4D, Table 2; GLM, F(2,32) = 18.4, P < 0.0001]; this effect is similar to the combination of antagonists to PKA and PKC, either of which can act upstream of ERK. Our results newly implicate PKC in activity-dependent striatal LTP and agree with prior studies implicating PKA and ERK (Calabresi et al. 1992b; Kerr and Wickens 2001). These results further suggest that PKC and PKA cooperatively serve LTP, which could occur through coactivation of ERK.

Fig. 4.

TBS LTP requires protein kinase C (PKC), protein kinase A (PKA), and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK). The drug-free TBS group (DM, 50 Hz intraburst, 10.5 Hz theta) was collected interleaved with pharmacology experiments and thus is different than the analogous TBS group in Fig 2. Example traces from end of experiment (red) overlay baseline traces (gray). Error bars represent ± SEM. A: PKC inhibitor chelerythrine (CHE) blocks LTP. Reduced drug concentration reduces amplitude without completely blocking LTP (green). B: PKA inhibitor PKI blocks LTP. Reduced drug concentration reduces amplitude without completely blocking LTP (blue). C: reduced concentrations of PKC and PKA inhibitors fully block LTP when combined. Mean effect from independent reduced concentration inhibitors are overlaid. D: preventing ERK activation with MAPK/ERK kinase inhibitor U-0126 blocks LTP.

DISCUSSION

Learning correlates with theta frequency neural activity in the dorsal striatum, suggesting a theta-burst induction paradigm might evoke behaviorally relevant LTP in striatum. Our results support this hypothesis by showing that TBS evokes LTP which is more pronounced when using temporal parameters with better correspondence to striatal physiology. We further determine that a critical induction feature for LTP is burstiness, which is intriguing since medium spiny neuron up-state potentials observed in organotypic culture and in vivo may facilitate the burst firing that has demonstrated importance for striatal network function and behavior (Kerr and Plenz 2002; Miller et al. 2008; Stern et al. 1997). Importantly, reliance on in vivo striatal theta rhythms rather than altered ionic composition or pharmacology makes TBS LTP a convincing ex vivo model for plasticity, serving learning, memory, and motor adaptation. Indeed, we confirm involvement of several receptors and kinases previously implicated in striatal plasticity, as well as learning and memory. The success of TBS LTP across dorsal striatal regions in adult brain slice presages its utility in combination with future behavioral studies.

Although both 50-Hz and 100-Hz stimulation frequencies have been applied to evoke plasticity, the striatal medium spiny neurons comprising 95% of striatal cells are not likely to be engaged by high-frequency activation in vivo. These neurons receive input from layer V cortical neurons, which fire with an average rate of 5–10 Hz (Fellous et al. 2003; Wilson and Groves 1981). Furthermore, recordings from behaving mice and rats have shown medium spiny neurons fire below 5 Hz on average, with the maximum spontaneous firing rate in vivo no greater than 50 Hz (Barnes et al. 2005; Miller et al. 2008). In anesthetized rat, single striatal neurons are successfully entrained to moderate (20 Hz), but not to high-frequency (100 Hz) cortical afferent stimulation (Schulz et al. 2011). Given these observations in the literature, we expected and indeed obtained the greatest plasticity through use of more moderate induction frequencies.

Theta frequency is a physiologically significant parameter in activity-based LTP induction as dorsal striatal local field potentials recorded in vivo demonstrate neuronal population coherence at theta-range frequencies (5–11 Hz). Importantly, these theta rhythms are modulated in an activity-dependent manner during learning (Buzsaki 2005; Koralek et al. 2012; Tort et al. 2008). Depolarizing potentials in medium spiny neurons occur at 5 Hz as a result of 5 Hz coherence in firing among hundreds of convergent afferents from layer V cortex in anesthetized rat (Charpier et al. 1999). Higher theta-range frequencies may dominate in wakeful animals, or during learning, since recent studies in awake, behaving subjects indicate that learning-related theta centers around 7–11 Hz in dorsal striatum (DeCoteau et al. 2007; Tort et al. 2008). Nonetheless, we initially used 5-Hz because 5-Hz TBS evokes robust LTP in hippocampal slice (Larson et al. 1986; Nie et al. 2007), and striatal STDP pairings paced at 5 Hz evoke LTP in young animals (Shen et al. 2008). While 5 Hz indeed evoked a modest LTP, we found the amplitude and duration were greatly improved by using higher frequency theta-bursts. This result suggests that LTP processes may be tuned to subtly different frequencies in striatum vs. hippocampus. In light of the recent in vivo work mentioned, this result supports the idea that striatal neurons are tuned to promote LTP in response to temporal patterns emerging with learning behavior.

In optimizing a theta-burst protocol, we eliminated fast actions of intrastriatal GABA release which are present in vivo to provide certainty that TBS potentiates the response of medium spiny neurons to glutamatergic afferents rather than depressing the fast GABAergic inhibition of striatal response. This is a valid concern because GABAergic synapses within striatum are more sensitive to endocannabinoid-dependent depression than are glutamatergic synapses (Adermark and Lovinger 2009). Although most corticostriatal plasticity studies are carried out with GABAA blocked (Akopian and Walsh 2006; Gubellini et al. 2003; Kerr and Wickens 2001; Shen et al. 2008), native GABAA transmission must shape striatal plasticity.

Indeed, the direction of STDP is reversed by the presence of GABAA antagonists. Specifically, corticostriatal synapses onto medium spiny neurons are potentiated when presynaptic release precedes postsynaptic depolarization (Hebbian LTP) only when GABAA is blocked; when GABAA is not blocked, pre-post pairing is depressing, and LTP is instead evoked when postsynaptic depolarization preceded presynaptic release (anti-Hebbian) (Fino et al. 2010). Several mechanisms have been proposed to account for reversal of STDP by GABAA, such as altered ratio of NMDA to L-type calcium influx in dendrites (Paille et al. 2013) or Hebbian potentiation of feed-forward inhibition (Fino et al. 2008). Alternatively, increased dopamine release may be responsible for switching STDP direction (Shen et al. 2008; Shindou et al. 2011), since GABAA antagonists increase activity-dependent intrastriatal dopamine release (Juranyi et al. 2003). Any of these mechanisms, altered calcium source, potentiation of feed-forward inhibition, or lowered dopamine release, may contribute to reduce TBS LTP amplitude in the absence of picrotoxin.

The optimal TBS protocol induces robust DM LTP lasting multiple hours, yet no plasticity results if the brief pause separating bursts is omitted. This demonstrates that the 35-ms pause between bursts is critical to LTP, since no plasticity is induced if this pause is reduced to 20 ms (so that pulses run together into nonbursty, 50-Hz stimuli). Note that TBS variations with lower intraburst or higher interburst frequencies cannot be tested while conserving pulse number per burst, as these adjustments would encroach on the already small interburst pause, eliminating burstiness. The requisite pause may enable LTP through phasic activation of neuromodulators, given that salient behavioral stimuli produce burst firing of cholinergic interneurons (Aosaki et al. 1994) which in turn enhances dopamine release (Threlfell et al. 2012). This may be tested using voltammetry to compare dopamine release resulting from TBS and its nonbursty counterpart. Alternatively, the pause may enable resensitization of critical plasticity effectors. For instance, a brief break in stimulation may relieve inactivation of NMDA receptors, or else it might relieve desensitization of mGluR, dopamine receptors, or AChR implicated in this study. Investigating the requisite pause may shed light on a mechanism for the resilience of TBS LTP in the absence of GABAA antagonist.

Striatal sensitivity to temporal pattern is most meaningful if both LTP and LTD can be evoked in the same preparation; therefore, we sought to induce LTD by varying temporal pattern alone. HFS is commonly used to evoke LTD in Mg2+ containing aCSF (Adermark and Lovinger 2009; Choi and Lovinger 1997; Wang et al. 2006; Yin et al. 2009), yet four-train, 100-Hz HFS does not evoke lasting plasticity in our preparation. This may be related to animal age, which is known to influence evoked striatal plasticity (Partridge et al. 2000), and at least one report notes that 100-Hz HFS does not reliably produce LTD in adult animals (Hopf et al. 2010), while other studies report a mixture of LTP and LTD as a result of HFS in adults (Akopian et al. 2000; Akopian and Walsh 2006; Spencer and Murphy 2000). Our preparation demonstrates reliable LTD across regions when stimulation is delivered at a moderate, 20-Hz frequency, similar to protocols used previously (Lerner and Kreitzer 2012; Yin and Lovinger 2006). In addition to being more effective, 20 Hz is more physiological than 100 Hz, given the moderate native firing frequencies in cortical afferents and striatal medium spiny neurons (Schulz et al. 2011). Capacity for bidirectional plasticity in both DM and DL striatum through manipulation of stimuli timing alone argues against our preparation being skewed toward generating LTP. This strengthens our findings that temporal features of TBS, such as frequency-tuning and burstiness, can modulate LTP strength.

In addition to confirming a requirement for NMDA receptors, our experiments demonstrate that TBS LTP requires Gq-coupled metabotropic receptors responding to glutamate and AChR, and Gs/olf-coupled dopamine receptors. Gq effectors interact with calcium influx to generate 2-arachidonyl glycerol, an endocannabinoid implicated in LTD, and also lead to PKC activation. PKC has been implicated in plasticity, memory, and in striatal chemical LTP (Diez-Guerra 2010; Gubellini et al. 2004) and is a critical intermediary for neuromodulation of NMDA and AMPA receptors within striatum (Ahn and Choe 2010; Calabresi et al. 1998). We find that independently blocking group I mGluR, m1 AChR receptors, or PKC is sufficient to fully prevent TBS LTP, suggesting that coordinated glutamate and acetylcholine transmission is needed to generate LTP-supportive PKC. The neurotransmitter dopamine acts at Gs/olf-coupled D1-type receptors (D1 and D5) expressed on several cell classes within striatum, including both classes of medium spiny neuron (Rivera et al. 2002; Surmeier et al. 1996). D1-type dopamine receptors (along with A2A adenosine receptors) are Gs/olf coupled, leading to elevations in cyclic AMP and PKA. PKA has demonstrated a role in learning and is believed to serve striatal LTP by enhancing medium spiny neuron responsiveness (Dudman et al. 2003; Tseng et al. 2007). Our finding that D1-type dopamine receptor antagonist blocks LTP is consistent with studies of striatal LTP induced using either four-train HFS in 0 Mg2+ or STDP (Calabresi et al. 1992a; Fino et al. 2010; Kerr and Wickens 2001; Pawlak and Kerr 2008; Shen et al. 2008). Indeed, D1-type receptor antagonism blocks 0 Mg2+ LTP equally well in all patched medium spiny neurons, with the same time course we show (Calabresi et al. 2000; Kerr and Wickens 2001). Thus D1/D5 receptor activity likely increases PKA within medium spiny neurons, which we demonstrate contributes to LTP. Activation of PKA has been demonstrated to accelerate degradation of Gq proteins needed to generate endocannabinoids and active PKC (Lerner and Kreitzer 2012); thus the requirement for two sources of Gq may stem from the need to overcome PKA obstructing PKC activation. Together our results demonstrate that neither Gq nor Gs/olf signaling is independently sufficient to support TBS LTP, and that both contribute.

Persistent memory, late-phase plasticity, and long-lasting TBS LTP are each reliant on the kinase and transcriptional regulator ERK (Adams et al. 2000; Valjent et al. 2001). ERK is important for striatal learning, especially that associated with drug addiction (Shiflett and Balleine 2011; Valjent et al. 2006). It is noteworthy that both kinases PKC and PKA are capable of raising ERK phosphorylation and activity (Mao et al. 2005; Shiflett and Balleine 2011). Thus the cooperativity we see when combining low concentrations of PKC and PKA antagonists may result from concomitant reduction in these two sources of ERK phosphorylation. Two possibilities can be distinguished in future works by measuring the effect of PKA and PKC inhibitors on TBS LTP from identified D1 and D2 medium spiny neurons: PKC and PKA may act together upstream of ERK in each medium spiny neuron; or else PKC and PKA may be differentially critical to ERK activation between medium spiny neuron classes. Identifying roles for effectors known to be critical to learning and long-term memory storage strengthens TBS as a model for behaviorally relevant plasticity.

We find DM striatum more prone to potentiation and DL more prone to depression, agreeing with numerous reports (Partridge et al. 2000; Smith et al. 2001; Wickens et al. 2007). Striatal regional gradients exist for several plasticity effectors. For instance, LTD-required endocannabinoid receptors are denser laterally (Hilario et al. 2007). An established medial-to-lateral gradient in NMDA receptor subunit composition and distribution (Chapman et al. 2003; Yin et al. 2009) may cause regional differences in calcium-dependent plasticity effectors, including endocannabinoids and PKC. Dorsolaterally, greater dopamine innervation paired with higher density Gi/o-coupled D2-type dopamine receptors (Doucet et al. 1986; Yin et al. 2009) could limit LTP-supportive PKA in this region. The trend toward greater LTP in DM relative to DL striatum is maintained whether or not GABAA is blocked (Smith et al. 2001); and our use of picrotoxin rules out regional differences in plasticity of GABAA transmission. Whatever the reasons for greater LTP magnitude and duration dorsomedially, the current utility of TBS LTP in either region (albeit reduced laterally) will be valuable for investigating learning, since dorsal striatal regions serve distinct styles and phases of learning (Pauli et al. 2012; Yin et al. 2006).

Importantly, dorsal striatum expresses long-lasting potentiation in response to physiological activity patterns similar to those occurring with learning, namely TBS. The extensive duration of DM TBS LTP will accommodate evaluation of late-phase LTP in this region. Utility in adult tissue will benefit behavioral approaches to striatal research, since working with adult animals avoids developmental confounds. Moreover, we have success with TBS LTP in tissue from adult Long Evans rat, a more versatile model for behavior than mice (Hawes et al. 2012). Thus TBS improves on existing LTP protocols in its capacity to merge plasticity with behavioral studies, generating exciting opportunity for advancing knowledge of striatal neurobiology serving learning and memory.

GRANTS

Support from Office of Naval Research Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative Grant N00014-10-1-0198 and NIAAA R01 is gratefully acknowledged.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: S.L.H. and K.T.B. conception and design of research; S.L.H., F.G., R.C.E., and E.A.B. performed experiments; S.L.H., F.G., and K.T.B. analyzed data; S.L.H. and K.T.B. interpreted results of experiments; S.L.H. prepared figures; S.L.H. drafted manuscript; S.L.H. and K.T.B. edited and revised manuscript; S.L.H., F.G., R.C.E., and K.T.B. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Abraham WC, Huggett A. Induction and reversal of long-term potentiation by repeated high-frequency stimulation in rat hippocampal slices. Hippocampus 7: 137–145, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams JP, Roberson ED, English JD, Selcher JC, Sweatt JD. MAPK regulation of gene expression in the central nervous system. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Warsz) 60: 377–394, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adermark L, Lovinger DM. Frequency-dependent inversion of net striatal output by endocannabinoid-dependent plasticity at different synaptic inputs. J Neurosci 29: 1375–1380, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn SM, Choe ES. Alterations in GluR2 AMPA receptor phosphorylation at serine 880 following group I metabotropic glutamate receptor stimulation in the rat dorsal striatum. J Neurosci Res 88: 992–999, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akopian G, Musleh W, Smith R, Walsh JP. Functional state of corticostriatal synapses determines their expression of short- and long-term plasticity. Synapse 38: 271–280, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akopian G, Walsh JP. Pre- and postsynaptic contributions to age-related alterations in corticostriatal synaptic plasticity. Synapse 60: 223–238, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aosaki T, Graybiel AM, Kimura M. Effect of the nigrostriatal dopamine system on acquired neural reponses in the striatum of behaving monkeys. Science 265: 412–415, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuthnott GW, Ingham CA, Wickens JR. Dopamine and synaptic plasticity in the neostriatum. J Anat 196: 587–596, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asrar S, Zhou Z, Ren W, Jia Z. Ca(2+) permeable AMPA receptor induced long-term potentiation requires PI3/MAP kinases but not Ca/CaM-dependent kinase II. PLos One 4: e4339, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes TD, Kubota Y, Hu D, Jin DZ, Graybiel AM. Activity of striatal neurons reflects dynamic encoding and recoding of procedural memories. Nature 437: 1158–1161, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsaki G. Theta rhythm of navigation: link between path integration and landmark navigation, episodic and semantic memory. Hippocampus 15: 827–840, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabresi P, Centonze D, Gubellini P, Bernardi G. Activation of M1-like muscarinic receptors is required for the induction of corticostriatal LTP. Neuropharmacology 38: 323–326, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabresi P, Centonze D, Gubellini P, Pisani A, Bernardi G. Endogenous ACh enhances striatal NMDA-responses via M1-like muscarinic receptors and PKC activation. Eur J Neurosci 10: 2887–2895, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabresi P, Gubellini P, Centonze D, Picconi B, Bernardi G, Chergui K, Svenningsson P, Fienberg AA, Greengard P. Dopamine and cAMP-regulated phosphoprotein 32 kDa controls both striatal long-term depression and long-term potentiation, opposing forms of synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci 20: 8443–8451, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabresi P, Maj R, Mercuri NB, Bernardi G. Coactivation of D1 and D2 dopamine receptors is required for long-term synaptic depression in the striatum. Neurosci Lett 142: 95–99, 1992a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabresi P, Pisani A, Mercuri NB, Bernardi G. Long-term potentiation in the striatum is unmasked by removing the voltage-dependent magnesium block of NMDA receptor channels. Eur J Neurosci 4: 929–935, 1992b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman DE, Keefe KA, Wilcox KS. Evidence for functionally distinct synaptic NMDA receptors in ventromedial versus dorsolateral striatum. J Neurophysiol 89: 69–80, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charpier S, Mahon S, Deniau JM. In vivo induction of striatal long-term potentiation by low-frequency stimulation of the cerebral cortex. Neuroscience 91: 1209–1222, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Lovinger DM. Decreased probability of neurotransmitter release underlies striatal long-term depression and postnatal development of corticostriatal synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94: 2665–2670, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCoteau WE, Thorn C, Gibson DJ, Courtemanche R, Mitra P, Kubota Y, Graybiel AM. Oscillations of local field potentials in the rat dorsal striatum during spontaneous and instructed behaviors. J Neurophysiol 97: 3800–3805, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez-Guerra FJ. Neurogranin, a link between calcium/calmodulin and protein kinase C signaling in synaptic plasticity. IUBMB Life 62: 597–606, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doucet G, Descarries L, Garcia S. Quantification of the dopamine innervation in adult rat neostriatum. Neuroscience 19: 427–445, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudman JT, Eaton ME, Rajadhyaksha A, Macias W, Taher M, Barczak A, Kameyama K, Huganir R, Konradi C. Dopamine D1 receptors mediate CREB phosphorylation via phosphorylation of the NMDA receptor at Ser897-NR1. J Neurochem 87: 922–934, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellous JM, Rudolph M, Destexhe A, Sejnowski TJ. Synaptic background noise controls the input/output characteristics of single cells in an in vitro model of in vivo activity. Neuroscience 122: 811–829, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fino E, Deniau JM, Venance L. Cell-specific spike-timing-dependent plasticity in GABAergic and cholinergic interneurons in corticostriatal rat brain slices. J Physiol 586: 265–282, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fino E, Glowinski J, Venance L. Bidirectional activity-dependent plasticity at corticostriatal synapses. J Neurosci 25: 11279–11287, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fino E, Paille V, Cui Y, Morera-Herreras T, Deniau JM, Venance L. Distinct coincidence detectors govern the corticostriatal spike timing-dependent plasticity. J Physiol 588: 3045–3062, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graybiel AM. Building action repertoires: memory and learning functions of the basal ganglia. Curr Opin Neurobiol 5: 733–741, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan X, Wang L, Chen CL, Guan Y, Li S. Roles of two subtypes of corticotrophin-releasing factor receptor in the corticostriatal long-term potentiation under cocaine withdrawal condition. J Neurochem 115: 795–803, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubellini P, Centonze D, Tropepi D, Bernardi G, Calabresi P. Induction of corticostriatal LTP by 3-nitropropionic acid requires the activation of mGluR1/PKC pathway. Neuropharmacology 46: 761–769, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubellini P, Saulle E, Centonze D, Costa C, Tropepi D, Bernardi G, Conquet F, Calabresi P. Corticostriatal LTP requires combined mGluR1 and mGluR5 activation. Neuropharmacology 44: 8–16, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawes SL, Gillani F, Blackwell KT. Striatal LTP mechanisms and connection to learning. Program No. 790.16. In: 2012 Neuroscience Meeting Planner New Orleans, LA: Society for Neuroscience, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Hilario MR, Clouse E, Yin HH, Costa RM. Endocannabinoid signaling is critical for habit formation. Front Integr Neurosci 1: 6, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopf FW, Seif T, Mohamedi ML, Chen BT, Bonci A. The small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel is a key modulator of firing and long-term depression in the dorsal striatum. Eur J Neurosci 31: 1946–1959, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juranyi Z, Zigmond MJ, Harsing LG., Jr. [3H]dopamine release in striatum in response to cortical stimulation in a corticostriatal slice preparation. J Neurosci Methods 126: 57–67, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr JN, Plenz D. Dendritic calcium encodes striatal neuron output during up-states. J Neurosci 22: 1499–1512, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr JN, Wickens JR. Dopamine D-1/D-5 receptor activation is required for long-term potentiation in the rat neostriatum in vitro. J Neurophysiol 85: 117–124, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koralek AC, Jin X, Long JD, Costa RM, Carmena JM. Corticostriatal plasticity is necessary for learning intentional neuroprosthetic skills. Nature 483: 331–335, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreitzer AC, Malenka RC. Dopamine modulation of state-dependent endocannabinoid release and long-term depression in the striatum. J Neurosci 25: 10537–10545, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreitzer AC, Malenka RC. Striatal plasticity and basal ganglia circuit function. Neuron 60: 543–554, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson J, Lynch G. Induction of synaptic potentiation in hippocampus by patterned stimulation involves two events. Science 232: 985–990, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson J, Wong D, Lynch G. Patterned stimulation at the theta frequency is optimal for the induction of hippocampal long-term potentiation. Brain Res 368: 347–350, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner TN, Kreitzer AC. Neuromodulatory control of striatal plasticity and behavior. Curr Opin Neurobiol 21: 322–327, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner TN, Kreitzer AC. RGS4 is required for dopaminergic control of striatal ltd and susceptibility to Parkinsonian motor deficits. Neuron 73: 347–359, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovinger DM, Tyler E, Fidler S, Merritt A. Properties of a presynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptor in rat neostriatal slices. J Neurophysiol 69: 1236–1244, 1993a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovinger DM, Tyler EC, Merritt A. Short- and long-term synaptic depression in rat neostriatum. J Neurophysiol 70: 1937–1949, 1993b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malenka RC, Kocsis JD. Presynaptic actions of carbachol and adenosine on corticostriatal synaptic transmission studied in vitro. J Neurosci 8: 3750–3756, 1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao L, Yang L, Tang Q, Samdani S, Zhang G, Wang JQ. The scaffold protein Homer1b/c links metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 to extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase cascades in neurons. J Neurosci 25: 2741–2752, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzucchelli C, Vantaggiato C, Ciamei A, Fasano S, Pakhotin P, Krezel W, Welzl H, Wolfer DP, Pages G, Valverde O, Marowsky A, Porrazzo A, Orban PC, Maldonado R, Ehrengruber MU, Cestari V, Lipp HP, Chapman PF, Pouyssegur J, Brambilla R. Knockout of ERK1 MAP kinase enhances synaptic plasticity in the striatum and facilitates striatal-mediated learning and memory. Neuron 34: 807–820, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BR, Walker AG, Shah AS, Barton SJ, Rebec GV. Dysregulated information processing by medium spiny neurons in striatum of freely behaving mouse models of Huntington's disease. J Neurophysiol 100: 2205–2216, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie T, McDonough CB, Huang T, Nguyen PV, Abel T. Genetic disruption of protein kinase A anchoring reveals a role for compartmentalized kinase signaling in theta-burst long-term potentiation and spatial memory. J Neurosci 27: 10278–10288, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packard MG, Teather LA. Double dissociation of hippocampal and dorsal-striatal memory systems by posttraining intracerebral injections of 2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid. Behav Neurosci 111: 543–551, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paille V, Fino E, Du K, Morera-Herreras T, Perez S, Kotaleski JH, Venance L. GABAergic circuits control spike-timing-dependent plasticity. J Neurosci 33: 9353–9363, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge JG, Tang KC, Lovinger DM. Regional and postnatal heterogeneity of activity-dependent long-term changes in synaptic efficacy in the dorsal striatum. J Neurophysiol 84: 1422–1429, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoli V, Besnard A, Herve D, Pages C, Heck N, Girault JA, Caboche J, Vanhoutte P. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate-independent tyrosine phosphorylation of NR2B mediates cocaine-induced extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation. Biol Psychiatry 69: 218–227, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauli WM, Clark AD, Guenther HJ, O'Reilly RC, Rudy JW. Inhibiting PKMzeta reveals dorsal lateral and dorsal medial striatum store the different memories needed to support adaptive behavior. Learn Mem 19: 307–314, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak V, Kerr JN. Dopamine receptor activation is required for corticostriatal spike-timing-dependent plasticity. J Neurosci 28: 2435–2446, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen JD, Chen X, Vinade L, Dosemeci A, Lisman JE, Reese TS. Distribution of postsynaptic density (PSD)-95 and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II at the PSD. J Neurosci 23: 11270–11278, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds JN, Hyland BI, Wickens JR. A cellular mechanism of reward-related learning. Nature 413: 67–70, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds JN, Wickens JR. Dopamine-dependent plasticity of corticostriatal synapses. Neural Netw 15: 507–521, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera A, Alberti I, Martin AB, Narvaez JA, de la Calle A, Moratalla R. Molecular phenotype of rat striatal neurons expressing the dopamine D5 receptor subtype. Eur J Neurosci 16: 2049–2058, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronesi J, Lovinger DM. Induction of striatal long-term synaptic depression by moderate frequency activation of cortical afferents in rat. J Physiol 562: 245–256, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz JM, Pitcher TL, Savanthrapadian S, Wickens JR, Oswald MJ, Reynolds JN. Enhanced high-frequency membrane potential fluctuations control spike output in striatal fast-spiking interneurones in vivo. J Physiol 589: 4365–4381, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H, Moussawi K, Zhou W, Toda S, Kalivas PW. Heroin relapse requires long-term potentiation-like plasticity mediated by NMDA2b-containing receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108: 19407–19412, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W, Flajolet M, Greengard P, Surmeier DJ. Dichotomous dopaminergic control of striatal synaptic plasticity. Science 321: 848–851, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiflett MW, Balleine BW. Molecular substrates of action control in cortico-striatal circuits. Prog Neurobiol 95: 1–13, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindou T, Ochi-Shindou M, Wickens JR. A Ca(2+) threshold for induction of spike-timing-dependent depression in the mouse striatum. J Neurosci 31: 13015–13022, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R, Musleh W, Akopian G, Buckwalter G, Walsh JP. Regional differences in the expression of corticostriatal synaptic plasticity. Neuroscience 106: 95–101, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer JP, Murphy KP. Bi-directional changes in synaptic plasticity induced at corticostriatal synapses in vitro. Exp Brain Res 135: 497–503, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer JP, Murphy KP. Activation of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase is required for long-term enhancement at corticostriatal synapses in rats. Neurosci Lett 329: 217–221, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern EA, Kincaid AE, Wilson CJ. Spontaneous subthreshold membrane potential fluctuations and action potential variability of rat corticostriatal and striatal neurons in vivo. J Neurophysiol 77: 1697–1715, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surmeier DJ, Song WJ, Yan Z. Coordinated expression of dopamine receptors in neostriatal medium spiny neurons. J Neurosci 16: 6579–6591, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi M, Yamamoto C. Suppressing action of cholinergic agents on synaptic transmissions in the corpus striatum of rats. Exp Neurol 62: 433–443, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Threlfell S, Lalic T, Platt NJ, Jennings KA, Deisseroth K, Cragg SJ. Striatal dopamine release is triggered by synchronized activity in cholinergic interneurons. Neuron 75: 58–64, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tort AB, Kramer MA, Thorn C, Gibson DJ, Kubota Y, Graybiel AM, Kopell NJ. Dynamic cross-frequency couplings of local field potential oscillations in rat striatum and hippocampus during performance of a T-maze task. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105: 20517–20522, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng KY, Snyder-Keller A, O'Donnell P. Dopaminergic modulation of striatal plateau depolarizations in corticostriatal organotypic cocultures. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 191: 627–640, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjent E, Caboche J, Vanhoutte P. Mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase induced gene regulation in brain: a molecular substrate for learning and memory? Mol Neurobiol 23: 83–99, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjent E, Corbille AG, Bertran-Gonzalez J, Herve D, Girault JA. Inhibition of ERK pathway or protein synthesis during reexposure to drugs of abuse erases previously learned place preference. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 2932–2937, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh JP. Depression of excitatory synaptic input in rat striatal neurons. Brain Res 608: 123–128, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Kai L, Day M, Ronesi J, Yin HH, Ding J, Tkatch T, Lovinger DM, Surmeier DJ. Dopaminergic control of corticostriatal long-term synaptic depression in medium spiny neurons is mediated by cholinergic interneurons. Neuron 50: 443–452, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickens JR, Budd CS, Hyland BI, Arbuthnott GW. Striatal contributions to reward and decision making: making sense of regional variations in a reiterated processing matrix. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1104: 192–212, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson CJ, Groves PM. Spontaneous firing patterns of identified spiny neurons in the rat neostriatum. Brain Res 220: 67–80, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia JX, Li J, Zhou R, Zhang XH, Ge YB, Ru YX. Alterations of rat corticostriatal synaptic plasticity after chronic ethanol exposure and withdrawal. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 30: 819–824, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin HH, Knowlton BJ. The role of the basal ganglia in habit formation. Nat Rev Neurosci 7: 464–476, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin HH, Knowlton BJ, Balleine BW. Inactivation of dorsolateral striatum enhances sensitivity to changes in the action-outcome contingency in instrumental conditioning. Behav Brain Res 166: 189–196, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin HH, Lovinger DM. Frequency-specific and D2 receptor-mediated inhibition of glutamate release by retrograde endocannabinoid signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 8251–8256, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin HH, Mulcare SP, Hilario MR, Clouse E, Holloway T, Davis MI, Hansson AC, Lovinger DM, Costa RM. Dynamic reorganization of striatal circuits during the acquisition and consolidation of a skill. Nat Neurosci 12: 333–341, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin HH, Ostlund SB, Knowlton BJ, Balleine BW. The role of the dorsomedial striatum in instrumental conditioning. Eur J Neurosci 22: 513–523, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Lin SC, Nicolelis MA. Spatiotemporal coupling between hippocampal acetylcholine release and theta oscillations in vivo. J Neurosci 30: 13431–13440, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]