Abstract

Losartan (Los) is a Food and Drug Administration-approved antihypertensive medication that has a well-tolerated side effect profile. We have demonstrated that treatment with Los immediately after injury was effective at promoting muscle healing and inducing an antifibrotic effect in a murine model of skeletal muscle injury. We initially investigated the minimum effective dose of Los administration immediately after injury and subsequently determined whether the timing of administering a clinically relevant dose of Los would influence its effectiveness at improving muscle healing after muscle injury. In the first part of this study, mice were administered 3, 10, 30, or 300 mg·kg−1·day−1 of Los immediately after injury, and the healing process was evaluated histologically and physiologically 4 wk after injury. In the second study, the clinically relevant dose of 10 mg·kg−1·day−1 was administered immediately or started at 3 or 7 days postinjury. The administration of 300 mg·kg−1·day−1 immediately following injury led to a significant increase in muscle regeneration, a significant decrease in fibrosis, and an improvement in muscle function. Moreover, we observed a significant decrease in fibrosis and a significant increase in muscle regeneration at 4 wk postinjury, when the clinically relevant dose of 10 mg·kg−1·day−1 was administered at 3 or 7 days postinjury. Functional evaluation also demonstrated a significant improvement compared with the injured untreated control when Los treatment was initiated 3 days after injury. Our study revealed accelerated muscle healing when the 300 mg·kg−1·day−1 of Los was administered immediately after injury and a clinically relevant dose of 10 mg·kg−1·day−1 of Los was administered at 3 or 7 days postinjury.

Keywords: losartan, contusion injury, fibrosis, regeneration

muscle injuries are a very common musculoskeletal problem encountered in sports medicine. In our laboratory, we have investigated several biological agents that provide benefit for accelerating the natural course of muscle injury healing. Specifically, we have focused our recent efforts on agents that inhibit muscle fibrosis via the inhibition of transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), a key cytokine in the fibrotic signaling pathway in skeletal muscle (23). Using decorin, suramin, relaxin, and γ-interferon, we have demonstrated that these therapies can decrease fibrosis and increase myofiber regeneration as well as functional recovery after skeletal muscle injury (3, 7, 8, 24, 32); however, the clinical use of these antifibrotic agents is hindered by a number of side effects including a lack of oral dosing formulations and, in the case of decorin, suramin, and relaxin, no Food and Drug Administration approval for human use. Losartan (Los), an angiotensin II (ANG II) receptor blocker, is a Food and Drug Administration-approved antihypertensive medication that has a well-tolerated side effect profile in humans. Our previous study using a murine model of skeletal muscle laceration injury revealed that Los treatment was effective for the promotion of muscle healing because of its antifibrotic effect; however, the optimal dosing and timing of Los was not evaluated (2). In the current study, we investigated the minimum dose of Los required to improve muscle healing when administered immediately after injury. We also tested the use of a clinically relevant dose of Los (10 mg·kg−1·day−1) administered at different time points after muscle injury.

In the current study we investigated the effect of administering a human-equivalent dose of Los on the expression profiles of myostatin (MSTN) and follistatin (FSTN) when administrated at different time points after muscle contusion injury. MSTN is a highly conserved TGF-β superfamily member that is expressed in skeletal muscle (28). Deletion of the MSTN gene in mice leads to muscle hypertrophy and hyperplasia with an approximate doubling of muscle mass (28). It is well known that MSTN stimulates the proliferation of muscle fibroblasts and the production of extracellular matrix protein both in vitro and in vivo (25), and in the absence or reduction of MSTN, muscle regenerates more quickly and completely following acute and chronic injury (26, 27, 44). FSTN is a molecule that has several different isoforms and is expressed by almost all the tissues of the body (34) and can effectively inhibit several members of the TGF-β superfamily, including MSTN (1, 9). Indeed, overexpression of FSTN induces a dramatic increase in satellite cells and muscle mass when overexpressed in a transgenic mouse model (22) or when delivered by an adeno-associated virus (9, 13).

METHODS

In Vitro Potential of ANG II and Los on C2C12 Myoblasts

Cell culture.

C2C12 myoblast cells, a well-known myoblast cell line, were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). C2C12 cells were plated at a density of 1.0 × 104 cells/well on 12-well plates and cultured with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen).

Effects of ANG II and Los on C2C12 myoblasts.

After a 24-h incubation period, the medium was removed and replaced with low serum-containing medium [Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 2% horse serum (HS); Invitrogen] containing different concentrations of human ANG II (10−10, 10−8, and 10−6 mol/l) or Los (10−10, 10−8, and 10−6 mol/l). The medium was replaced with fresh medium (containing the same concentrations of ANG II or Los) every 48 h and grown for a total of 5 days. To quantify the differentiation of the C2C12 cells, the cells were fixed in cold methanol for 2 min, washed twice in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 10 min at room temperature (RT), and finally incubated in blocking buffer (10% HS in PBS) for 30 min at RT. Cells were incubated overnight at 4°C with mouse monoclonal anti-skeletal fast myosin heavy chain antibodies (clone MY-32, Sigma) in 2% HS in PBS. After being washed with PBS, the samples were incubated with the secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 594 donkey anti-mouse IgG, Invitrogen) in 2% HS for 40 min at RT. Cell nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochroride (Sigma) for 10 min at RT. The fusion index (ratio of nuclei in myotubes to total nuclei) was also determined to evaluate the cell's myogenic differentiation capacity.

In vivo evaluation of the histological and physiological effects of Los on muscle healing in a contusion injury animal model.

The policies and procedures followed for all animal experimentation in this study were performed in accordance with those detailed by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the National Institutes of Health's Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Pittsburgh (protocol No. 0809009). Ninety normal mice (C57BL/6J, Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME; and National Cancer Institute at Frederick, Frederick, MD), age 8–10 wk, weighing 21.4 to 25.8 g, were used in these experiments. Six uninjured animals were used as controls to perform physiological analysis to set the normal baseline standard. A muscle contusion injury model was performed on the remaining 82 mice as previously described (4, 17, 33). Briefly, the mice were anesthetized with 1.0 to 1.5% isoflurane (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL) in 100% O2 gas. The animal's hindlimb was positioned by extending the knee and plantar flexing the ankle 90°. A 16.2-g, 1.6-cm stainless steel ball (Small Parts, Miami Lakes, FL) was dropped from a height of 100 cm onto an impactor that hit the mouse's tibialis anterior (TA) muscle. The muscle contusion made by this method was a high-energy blunt injury that created a large hematoma which was followed by muscle regeneration (4, 17), similar to what is observed in humans following a contusion injury (6). The mice were euthanized to evaluate the extent of healing at 1, 2, or 4 wk postinjury.

Drug administration to evaluate the optimal dose of Los initiated immediately following injury: dosing study.

All injured mice were randomly assigned to 1 of 6 groups: 1) no injury and no treatment (uninjured group, n = 6); 2) injury with no Los treatment (control group, n = 6); 3) administration of 3 mg·kg−1·day−1 of oral Los, (Cozaar, Merck, Whitehouse Station, NJ), initiated immediately after injury (3-mg group, n = 6); 4) administration of 10 mg·kg−1·day−1 of oral Los, initiated immediately after injury (10-mg group, n = 6); 5) administration of 30 mg·kg−1·day−1 of oral Los, initiated immediately after injury (30-mg group, n = 6), and 6) administration of 300 mg·kg−1·day−1 of oral Los, initiated immediately after injury (300-mg group, n = 6) (Fig. 1). The control group was supplied with normal drinking water, whereas the other four treatment groups received commercially available Los diluted in the drinking water. These doses were calculated based on body weight and the average daily intake of fluid ad libitum by the mice which were monitored 1 wk before injury. All animals were caged separately and allowed access to the water or Los solutions ad libitum from the time of injury to death 4 wk after injury.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the in vivo experimental design. Dosing study: uninjured, no injury without losartan (Los) treatment (n = 6); control group, injured without Los treatment (n = 6); 3-mg group, 3 mg·kg−1·day−1 of Los administrated immediately after injury (n = 6); 10-mg group, 10 mg·kg−1·day−1 of Los administrated immediately after injury (n = 6); 30-mg group, 30 mg·kg−1·day−1 of Los administrated immediately after injury (n = 6); 300-mg group, 300 mg·kg−1·day−1 of Los administrated immediately after injury (n = 6). Timing study: uninjured, no injury without Los treatment (n = 6); control group, injured without Los treatment (n = 18); day 0 group, 10 mg·kg−1·day−1 of Los administrated immediately after injury (n = 18); day 3 group, 10 mg·kg−1·day−1 of Los administrated 3 days after injury (n = 18); day 7 group, 10 mg·kg−1·day−1 of Los administrated 7 days after injury (n = 12). All animals in the dosing study were euthanized 4 wk after injury (n = 6, respectively). Six animals in each group of the timing study were euthanized 1, 2, or 4 wk after injury. The date and specimen of the uninjured and control groups in the dosing study were the same as the timing study at 4 wk after injury. Also, the date and specimen of the 10 mg·kg−1·day−1 group in the dosing study were the same as the day 0 group at 4 wk postinjury. MSTN, myostatin; FSTN, follistatin.

Evaluation of the administration timing of a human-equivalent Los dosage: timing study.

The 10 mg·kg−1·day−1 dose of Los was used for the timing studies, which is equivalent to the clinical dose used for the treatment of high blood pressure (50–100 mg/day) in humans (38). All injured mice were randomly assigned to one of five groups: 1) no injury and no treatment (uninjured group, n = 6, same as dosing study); 2) injury with no Los treatment (control group, n = 18, included n = 6 same as control group in dosing study at 4 wk after injury); 3) administration of 10 mg·kg−1·day−1 of oral Los (Merck), initiated immediately after injury (day 0 group, n = 18, included n = 6 same as 10 mg group in dosing study at 4 wk after injury); 4) administration of 10 mg·kg−1·day−1 of oral Los, initiated at 3 days postcontusion injury (day 3 group, n = 18); and 5) administration of 10 mg·kg−1·day−1 of oral Los, initiated at 7 days post injury (day 7 group, n = 12) (see schematic representation of the in vivo experimental protocol in Fig. 1). Los was dissolved in drinking water, and the dose of 10 mg·kg−1·day−1 was calculated as described above for the dosing study. All animals were caged separately and allowed access to the water or Los solutions ad libitum from the time of injury to death 1, 2, or 4 wk after injury. The expression levels of MSTN and FSTN were evaluated at 1 and 2 wk after injury (timing study) and muscle regeneration, fibrosis, and strength were evaluated at 4 wk postinjury (dosing and timing studies).

Physiological evaluation of muscle strength.

Four weeks postinjury, physiological testing was performed bilaterally on the hindlimbs of all the treatment groups via an in vivo testing method previously described (5, 37). Briefly, animals were anesthetized with 2 to 3% isoflurane and maintained in a surgical plane during the procedure with 1.5% isoflurane. The hindlimbs were shaved, and incisions were made to expose the sciatic nerve. To mechanically isolate forces generated by the anterior crural muscles (which include the TA) from the posterior crural muscles, the tendons for the posterior crural muscles were severed at the most distal attachment points. The animal was placed on an in situ muscle physiology test apparatus (model 809-B, Aurora Scientific, Ontario, Canada), and each hind limb was secured and tested separately. The animal was placed in a supine position, and a post was placed below the knee acting as a pivot point and the body placed so the knee was positioned with 90° of flexion and the ankle was at 0° of flexion. To stabilize the hindlimb, the foot of the limb being tested was secured to the lever arm with cloth tape. Isometric twitch torque data were collected by stimulating the sciatic nerve with 20 V at 1 Hz for 1 s and resting 1 s and repeating 10 times using DMC software (Aurora Scientific), which was analyzed with DMA3.2 software (Aurora Scientific). The average of the 10 twitch torques was used to calculate overall twitch function. Isometric tetanic torque data were collected by stimulating the sciatic nerve three to four times with 20 V at 250 Hz for 2 s with 2 s rest between stimulations. The average torque (mean ± SD) output by the muscle was reported. The mice were then euthanized and the muscle was removed from the leg and weighed before being flash frozen in 2-metylbutane precooled with liquid nitrogen. Specimens were kept at −80°C until sectioning.

Histological evaluation of muscle regeneration and fibrosis formation.

At 4 wk postinjury, serial cryosections of 8-μm thickness were stained with hematoxylin and eosin to monitor the number of regenerating myofibers. The total number of centronucleated myofibers, which are the regenerating myofibers (15, 26, 39), within the injury site were quantified using 10 random 200× fields selected from each sample (7, 8, 30, 33). Results were compared between the control and each of the treatment groups.

A Masson's Modified IMEB Trichrome Stain Kit (IMEB, Chicago, IL) was used to measure areas of fibrotic tissue within the injury sites. After the tissue was stained, the ratio of the fibrotic area to the total cross-sectional area of 10 random 100× fields was calculated to estimate fibrosis formation using Northern Eclipse software (Empix Imagine, Cheekatawaga, NY) in accordance with a previously described protocol (7, 8, 30, 33).

Immunofluorescent staining.

At 1 and 2 wk postinjury (timing study), immunohistochemistry was performed on the injured skeletal muscle to measure the expression of MSTN and FSTN in the control, day 0, day 3, and day 7 groups. The cryosectioned tissues were fixed in 4% formalin for 5 min, followed by two 10-min PBS washes. The sections were then blocked with 10% HS for 1 h at RT. Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies (MSTN, gdf8 antibody A300-401A, Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX; and FSTN, FSTN sc-23553, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) in 2% HS. After being washed in PBS, the samples were incubated with a secondary antibody (MSTN, donkey anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 594, Invitrogen; and FSTN, donkey anti-goat IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488, Invitrogen) in 2% HS for 1 h at RT. After the samples were washed in PBS, counterstaining was performed using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochroride.

The MSTN- or FSTN-positive (MSTN, red; and FSTN, green) areas were calculated using Northern Eclipse software (Empix Imaging). After the sections were stained, the total positive area to the total cross-sectional area of 10 randomly selected sections was calculated using a previously described protocol (7, 8, 17, 30).

Western blot analysis.

To determine the levels of MSTN and FSTN in the injured muscle, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), followed by Western blot analysis, was performed using techniques previously described (10, 11, 19, 43). Briefly, samples were minced and homogenized in one volume of an isolation buffer containing (in mM) 10 Tris·HCl, 10 NaCl, and 0.1 EDTA (pH 7.6). Protein concentrations in the homogenates were determined using a protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Bovine serum albumin (albumin from bovine serum A2153, Sigma) was used as the standard. Each sample was then solubilized in SDS sample buffer: 30% (vol/vol) glycerol, 5% (vol/vol) 2-mercaptoethanol, 2.3% (wt/vol) SDS, 62.5 mM Tris·HCl, 0.05% (wt/vol) bromophenol blue at pH 6.8, and 1 mg of protein was loaded on a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Electrophoresis was carried out at a constant current of 20 mA for 60 min according to the method of Laemmli (20). We investigated the expression of MSTN and FSTN in each of the muscles. Following SDS-PAGE, proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (pore size, 0.2 lm, Bio-Rad) using a mini trans-blot cell (Bio-Rad) at a constant voltage of 100 V for 60 min at 4°C. After the transfer, the polyvinylidene difluoride membranes were blocked for 1 h using a blocking buffer consisting of 3% BSA with 0.1% Tween-20 in Tris-buffered saline (pH 7.5). The membranes were then incubated overnight at 4°C with a polyclonal antibody (MSTN, gdf8 antibody A300-401A, Bethyl Laboratories; FSTN: sc-23553, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; and β-actin, sc-47778, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and then detected with a secondary antibody [MSTN, goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with alkaline phosphatase, Sigma; FSTN, rabbit anti-goat IgG conjugated with alkaline phosphatase, Sigma; and β-Actin, goat polyclonal secondary antibody to mouse IgG-H&L (HRP), ab6789, Abcam, Cambridge, MA] for 2 h. The membranes were subsequently reacted with bromochloroindolyl phosphate-nitroblue tetrazolium substrate. The bands on the immunoblots were quantified using computerized densitometry (SCION Image). The expression levels of MSTN and FSTN were divided by the respective β-actin expression levels to normalize total protein content of the samples. Each sample was also investigated in at least triplicate to ensure consistency to obtain a mean with a low standard error (10, 11, 19, 43).

Statistical analysis.

All of the results of this study were expressed as means ± SE. To determine the minimum effective dose of Los in vivo, we analyzed the results using Williams' multiple comparison (41, 46). Statistical significance of the data was analyzed, when necessary, by t-test or ANOVA with Scheffé's post hoc test. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

In Vitro Potential of ANG II and Los on C2C12 Myoblasts

Effects of ANG II and Los on myoblasts.

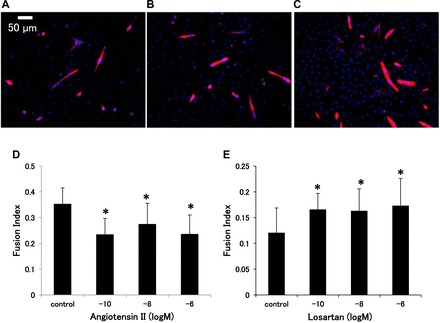

The fusion index of C2C12 cells in the groups exposed to 10−10, 10−8, and 10−6 mol/l of ANG II was significantly lower (0.23 ± 0.06, 0.27 ± 0.08, and 0.23 ± 0.06) than the control group (0.35 ± 0.07) (P < 0.05, respectively) (Fig. 2, A–D). On the other hand, groups-treated with Los (10−10, 10−8, and 10−6 mol/l) showed higher fusion indexes (0.17 ± 0.03, 0.16 ± 0.04, and 0.17 ± 0.05) than the control group (0.12 ± 0.04) (P < 0.05, respectively) (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

Immunocytochemical staining of C2C12 cells for fast myosin heavy chain 5 days after incubation with different concentration of ANG II or Los: control (A), 10−8 mol/l of ANG II (B), and 10−8 mol/l of Los (C). Myotubes are shown in red and nuclei are in blue (original magnification, ×200). D and E: comparison of fusion index of C2C12 differentiation with varied concentrations of ANG II or Los, respectively. *P < 0.05 vs. control by ANOVA.

In vivo evaluation of the histological and physiological effects of different doses of Los on muscle healing after contusion injury.

There were no significant differences in total body weights or in the harvested TA muscles' wet weights 4 wk postinjury among the four groups (3, 10, 30, and 300 mg·kg−1·day−1, data not shown).

High doses of Los improved muscle strength recovery after contusion injury.

Immediately after contusion injury, the TA muscles was severely damaged (data not shown). Two weeks after contusion injury, the peak isometric twitch and tetanic torque in the control group were 0.62 ± 0.12 and 2.35 ± 0.35 [(mN × mm)/mg TA weight], respectively. There were no significant differences among the 4 groups (control, day 0, day 3, and day 7 groups) in this pilot study (data not shown).

Dosing study.

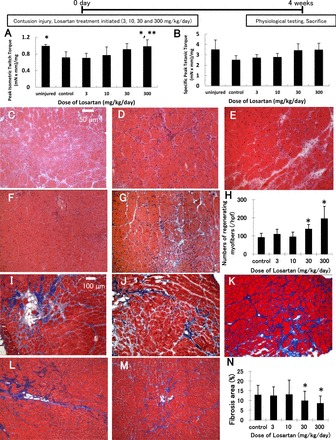

Results from the physiological evaluations in the dosing study groups performed at 4 wk postinjury are shown in Fig. 3, A and B. At 4 wk postinjury, the injured control group showed significantly less peak isometric twitch torque [0.71 ± 0.14 (mN × mm)/mg] when compared with the noninjured group [0.99 ± 0.04 (mN × mm)/mg]. The control group at 4 wk demonstrated improvements in peak isometric twitch and tetanic torque [2.52 ± 0.39 (mN × mm)/mg] compared with the 2-wk postinjury time point (data not shown). Peak isometric twitch torque in the 300 mg·kg−1·day−1 Los dosage group [0.98 ± 0.16 (mN × mm)/mg] was significantly greater than the control and 3 mg·kg−1·day−1 Los dosage [0.70 ± 0.11 (mN × mm)/mg] groups; however, the peak isometric twitch torque in the 3, 10, and 30 mg·kg−1·day−1 dosage groups [10, 30 mg·kg−1·day−1; 0.80 ± 0.20, 0.91 ± 0.14 (mN × mm)/mg] showed no improvement in muscle strength when compared with the control group (Fig. 3A). None of the losartan administered groups [3, 10, 30, and 300 mg·kg−1·day−1; 2.72 ± 0.30, 2.79 ± 0.34, 3.43 ± 0.63, and 3.49 ± 0.62 (mN × mm)/mg] demonstrated an improvement in peak tetanic torque when compared with the control group (Fig. 3B). The group-treated with 300 mg·kg−1·day−1 of Los showed the best muscle strength recovery for both peak twitch and tetanic torque among the groups, though it was only significantly better than the control and 3 mg·kg−1·day−1 groups for peak isometric twitch torque. In this study the only effective dose of Los tested that improved muscle force when injected immediately after injury was 300 mg·kg−1·day−1.

Fig. 3.

Los enhanced muscle force in a dose-dependent manner. Comparisons of peak isometric twitch (A) and tetanic (B) torque [(mN × mm)/mg tibialis anterior (TA) weight]. *P < 0.05 vs. control group and **P < 0.05, control and 3 mg·kg−1·day−1 groups by ANOVA. Histologic evaluation of regenerating myofibers and the formation of scar tissue at 4 wk after contusion injury by hematoxylin and eosin staining (C–G) of TA muscles-treated with different concentrations of Los: control (C), 3 mg·kg−1·day−1 (D), 10 mg·kg−1·day−1 (E), 30 mg·kg−1·day−1 (F), and 300 mg·kg−1·day−1 (G) initiated immediately after injury, or Masson's trichrome staining (I–M) (collagen, blue; myofibers, red; nuclei, black) of TA muscles-treated with different concentrations of Los: control (I), 3 mg·kg−1·day−1 (J), 10 mg·kg−1·day−1 (K), 30 mg·kg−1·day−1 (L), and 300 mg·kg−1·day−1 (M) initiated immediately after injury. Regenerating myofibers were defined by centronucleated myofibers (original magnification, ×200). The graph (H) depicts quantification in the number of regenerating myofibers in Los-treated animals compared with control animals. The ratio of the fibrotic area to the total cross-sectional area of 10 randomly selected sections was calculated to estimate the fibrosis formation (original magnification, ×100). The graph (N) depicts quantification of fibrotic area in Los-treated animals compared with control animals. Values are given as the means ± SE; n = 6 per group. hpf, high-power field. *P < 0.05 vs. control by ANOVA.

Timing study.

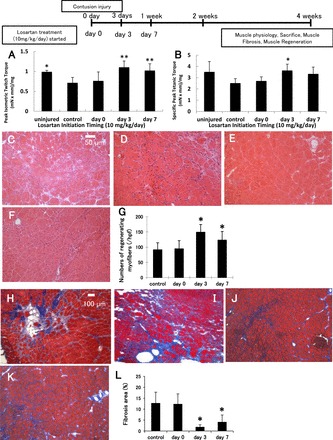

Results from the physiological evaluations of the timing study groups performed at 4 wk postinjury are shown in Fig. 4, A and B. Peak isometric twitch torque was significantly greater in mice when Los treatment (10 mg·kg−1·day−1) was initiated 3 and 7 days [3, 7 days; 1.10 ± 0.16, 1.02 ± 0.17 (mN × mm)/mg] after injury compared with the control and day 0 groups [control, day 0; 0.71 ± 0.14, 0.76 ± 0.22 (mN × mm)/mg]. The tetanic torque was only significantly greater in mice when Los treatment was initiated 3 days [3.64 ± 0.57 (mN × mm)/mg] after injury compared with the control group (2.52 ± 0.29 mN × m/mg, P < 0.05). Additionally, the day 3 and day 7 groups showed no appreciable differences in peak isometric twitch or peak tetanic torque from the uninjured group [peak twitch, 0.99 ± 0.04; and peak tetanic, 3.52 ± 0.92 (mN × mm)/mg]. The peak tetanic torque of the day 0 and day 7 groups were not significantly improved when compared with the control group [peak tetanic torque day 0, 2.71 ± 0.36; and peak tetanic peak twitch day 7, 3.34 ± 0.61 (mN × mm)/mg] (Fig. 4, A and B).

Fig. 4.

Los (10 mg·kg−1·day−1) administration enhanced muscle force in a time-dependent manner. Comparison of peak isometric twitch (A) and tetanic (B) torque [(mN × mm)/mg TA weight]. Values are given as means ± SE; n = 6 per group. *P < 0.05 vs. control group and **P < 0.05 vs. control and day 0 groups by ANOVA. Histological evaluation of regenerating myofibers and the formation of scar tissue at 4 wk after contusion injury by hematoxylin and eosin staining (C–F) of TA muscle-treated at different times after Los administration: control (C), day 0 (D), and day 3 (E), and day 7 (F) initiated after injury, or Masson's trichrome staining (H–K) (collagen, blue; myofibers, red; nuclei, black) of TA muscle-treated at different times after Los administration: control (H), day 0 (I), day 3 (J), and day 7 (K) initiated after injury. Regenerating myofibers were defined by centronucleated myofibers (original magnification, ×200). The graph (G) depicts quantification in the number of regenerating myofibers in Los-treated animals compared with control animals. *; P < 0.05 vs. control and day 0 by ANOVA. The ratio of the fibrotic area to the total cross-sectional area of 10 randomly selected slices was calculated to estimate the fibrosis formation (original magnification, ×100). The graph (L) depicts quantification of fibrotic area in Los-treated animals compared with control animals. Values are given as means ± SE; n = 6 per group. *P < 0.05 vs. control and day 0 by ANOVA.

Effect of Los on myofiber regeneration after contusion injury.

The number of centronucleated regenerating myofibers (15, 26, 39) present in the contusion-injured muscle were counted and compared among the groups 4 wk after injury in both the dosing and timing studies (Figs. 3, C–G, and 4, C–F, respectively).

In the dosing study, the group-treated with 300 mg·kg−1·day−1 of Los showed the greatest number of centrally nucleated myofibers compared with the other groups [194.5 ± 68.2/high-powered fields (hpf)] (Fig. 3H). The effect of Los on myofiber regeneration decreased gradually with reductions in the dose of Los. The minimum effective dose of Los on muscle regeneration was 30 mg·kg−1·day−1 (137.4 ± 25.3/hpf) compared with the control group (91.32 ± 23.0/hpf, P < 0.05). There were no significant differences between the lower dosage groups (3 and 10 mg·kg−1·day−1; 108.8 ± 27.8 and 94.47 ± 26.6/hpf) and the control group.

In the timing study with 10 mg·kg−1·day−1 of Los, we observed significant increases in the number of centronucleated myofibers in the day 3 and day 7 groups (149.0 ± 25.4, 123.3 ± 28.3/hpf) compared with the other groups (control group, 91.32 ± 23.0/hpf; and day 0 group, 94.47 ± 26.6/hpf, P < 0.05 respectively, Fig. 4G). There were no significant differences between the day 3 and day 7 groups. There was also no significant difference between the day 0 and control group (injured, no treatment).

Effect of Los on muscle fibrosis after contusion injury.

The areas of fibrotic scar tissue in the contusion injured muscle were analyzed and compared among the groups 4 wk after contusion injury in the dosing and timing studies (Figs. 3, I–M, and 4, H–K, respectively).

In the dosing study, the mean fibrotic area of the control group within the zone of injury was 12.8 ± 5.0%. The higher Los dosage groups (30 and 300 mg·kg−1·day−1) had significantly less fibrosis (9.82 ± 4.9 and 8.48 ± 3.8%) when compared with the control group (P < 0.05 respectively), whereas the lower Los dosage groups (3 and 10 mg·kg−1·day−1; 12.4 ± 4.6 and 13.0 ± 7.5%) did not show any significant difference compared with the untreated control group (Fig. 3N).

In the timing study, the day 3 and day 7 groups had significantly less fibrosis (1.87 ± 1.0 and 4.17 ± 3.1%, respectively) compared with the control and day 0 groups (12.8 ± 5.0, 12.4 ± 4.6%, P < 0.05, respectively, Fig. 4L). There was no significant difference between the day 3 and day 7 groups. There was also no significant difference between the day 0 and control groups.

Los enhanced expression of FSTN and MSTN in the timing study.

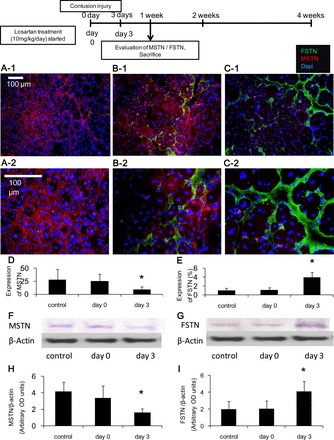

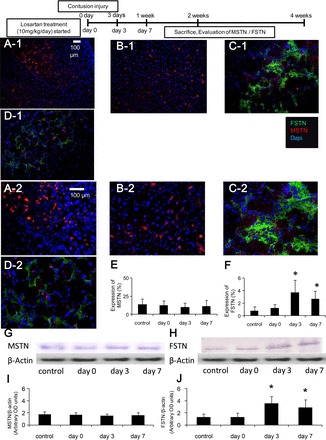

Immunohistochemical staining was performed to detect FSTN and MSTN expression in the contusion injured TA muscles 1 and 2 wk after injury (FSTN, green area; and MSTN, red area; Figs. 5, A–C, and 6, A–D). The 1-wk time point only contains data from three groups (control, day 0 and day 3), because of the fact that Los treatment had just been initiated for the day 7 group (i.e., 1 wk postinjury). The MSTN-positive areas were measured and compared between the various treatment groups. Expression of MSTN in the day 3 group (8.80 ± 5.5%) was significantly lower than in the control and day 0 groups (28.1 ± 20.1, 24.9 ± 14.2%, respectively) 1 wk after injury (P < 0.05 respectively, Fig. 5D). Two weeks after injury, there were no significant differences between the groups (control, 13.6 ± 7.5; day 0, 12.5 ± 6.5; day 3, 9.79 ± 6.0; and day 7, 11.1 ± 8.5%, Fig. 6E). The FSTN-positive areas were measured and compared between the various treatment groups. Expression of FSTN in the day 3 group (3.98 ± 1.2%) was significantly greater than the control and day 0 groups (1.04 ± 0.56, 1.20 ± 0.46%) 1 wk after injury (P < 0.05, respectively, Fig. 5E). The day 3 and day 7 groups (3.70 ± 1.9, 2.70 ± 1.3%) were significantly greater than the control and day 0 groups (0.82 ± 0.6, 1.22 ± 0.56%) 2 wk after injury (P < 0.05, respectively, Fig. 6F).

Fig. 5.

Los effect on MSTN and FSTN expression in the injured skeletal muscle 1 wk after injury. Immunohistochemical evaluation of MSTN and FSTN expression by immunofluorescence staining of the TA muscles. The sections were immunostained with MSTN (red), FSTN (green), and cell nuclei (blue): control (A-1 and A-2), day 0 (B-1 and B-2), and day 3 (C-1 and C-2); original magnification, ×200 (A-1, B-1, and C-1); and ×400 (A-2, B-2, and C-2). The ratio of the MSTN- or FSTN-positive area to the total cross-sectional area of 10 randomly selected slices was calculated. The graph depicts quantification of the MSTN (D)- or FSTN (E)-positive areas in Los-treated animals compared with each group. Los reduced the expression of MSTN (F and H) and enhanced FSTN expression (G and I) when measured by Western blot analysis. Values are means ± SE; n = 6 per group. *P < 0.05 vs. control and day 0 by ANOVA.

Fig. 6.

Los effect on MSTN and FSTN expression at 2 wk after injury. Immunohistochemical evaluation of the expression of MSTN and FSTN by immunofluorescent staining of the TA muscles. The sections were immunostained with MSTN (red), FSTN (green), and cell nuclei (blue): control (A-1 and A-2), day 0 (B-1 and B-2), day 3 (C-1 and C-2), and day 7 (D-1 and D-2); original magnification, ×200 (A-1, B-1, C-1, and D-1) and ×400 (A-2, B-2, C-2, and D-2). The ratio of the MSTN- or FSTN-positive area to the total cross-sectional area of 10 randomly selected slices was calculated. The graph depicts quantification of the MSTN (E)- or FSTN (F)-positive area in Los-treated animals compared with each groups. Los reduced the expression of MSTN (G and I) and increased FSTN expression (H and J) when measured by Western blot analysis. Values are means ± SE; n = 6 per group. *P < 0.05 vs. control and day 0 by ANOVA.

These immunohistochemical findings were further confirmed using Western blot analysis. Expression of MSTN in the day 3 group [1.61 ± 0.5 arbitrary optical density (OD) units] was significantly lower than in the untreated control and day 0 groups (4.14 ± 1.2, 3.36 ± 1.5 arbitrary OD units) 1 wk after injury (P < 0.05, Fig. 5, F and H); however, 2 wk after injury, there was no significant difference between the groups (control, 1.77 ± 0.2; day 0, 1.66 ± 0.4; day 3, 1.52 ± 0.3; and day 7, 1.62 ± 0.4 arbitrary OD units) (Fig. 6, G and I). Expression of FSTN in the day 3 group (4.09 ± 1.2 arbitrary OD units) was significantly greater than the control and day 0 groups (1.97 ± 1.0, 2.04 ± 1.0 arbitrary OD units) 1 wk after injury (P < 0.05, Fig. 5, G and I). The day 3 and day 7 groups (3.54 ± 1.2, 2.88 ± 1.3 arbitrary OD units) were also significantly greater than the control and day 0 groups (1.31 ± 0.5, 1.28 ± 0.7 arbitrary OD units) 2 wk after injury (P < 0.05, Fig. 6, H and J).

DISCUSSION

The functional recovery of skeletal muscle after injury is the most important parameter for the clinical translation of the therapy described in this paper. Our results demonstrated that Los accelerated the healing of injured muscle when administered immediately following injury; however, the minimum dose of Los used to obtain these results was 300 mg·kg−1·day−1, which is 30 times the equivalent dose for use in human patients suffering from hypertension. Additionally, this study demonstrated that the timing of Los administration is critical for obtaining optimal results when using a clinically relevant safe human dose of Los (10 mg·kg−1·day−1 initiated 3 days postinjury).

The role of ANG II in muscle fibrosis formation after injury is well documented in the cardiac literature, in which the antagonism of ANG II with ANG II receptor blockers is noted to significantly improve cardiac contractility and cardiac output (12). We demonstrated that Los could enhance skeletal muscle healing by reducing fibrosis and enhancing muscle regeneration (2). It was previously reported that Los diminished ANG II-induced type I collagen overexpression via the TGF-β signaling pathway that is mediated by the ANG II type 1 (AT1) receptor (42). We also reported that the expression of AT1 was elevated in the zone of injury and was more densely distributed within the extracellular matrix induced fibrotic tissue, indicating that AT1 upregulation is related to the deposition of fibrous scar tissue (2). Furthermore, it has been previously reported that ANG II protects endothelial cells against apoptosis, and high doses of Los are able to completely block this antiapoptotic effect (31). Moreover, ANG II plays a critical role in inducing proliferation, differentiation, and inflammation after skeletal muscle injury via AT1, through the release of mitogen-activating protein kinase (16, 29, 35).

Skeletal muscle development and regeneration are highly organized processes that are under tightly balanced regulation. MSTN, which is a member of the TGF-β superfamily, is expressed in adult skeletal muscle, heart, and adipose tissues (40) and acts as a negative regulator of tissue growth (47). MSTN is expressed during embryogenesis and in adult skeletal muscles during regeneration. High levels of MSTN are detected within necrotic fibers and connective tissue during the degenerative phase of muscle repair. On the other hand, regenerating myotubes contain low levels of MSTN during maturation (18). This expression profile suggests that MSTN acts as an inhibitor of muscle growth, perhaps via the repression of satellite cell proliferation during the process of muscle regeneration. It has been shown that MSTN inhibits cell proliferation and protein synthesis in C2C12 muscle cells (44), including the expression of myoblast determination protein and Pax3 (21).

Administration of Los 3 and 7 days after contusion injury, using a clinically relevant human dose equivalent for treating hypertension (10 mg·kg−1·day−1), effectively leads to the downregulation of endogenous MSTN at 1 wk postinjury. We also observed an increase in the number of centronucleated myofibers, a decrease in the area of fibrosis, and an enhancement in muscle strength when Los was administered 3 or 7 days after muscle injury, though significant improvement in peak tetanic torque was only observed in the day 3 group. Wang et al. (45) have demonstrated that Los significantly blocked the increase of the MSTN protein by blocking ANG II, which indicates that ANG II increases MSTN expression through the AT1 receptor. These results suggest that Los administrated 3 or 7 days after injury can diminish ANG II-induced MSTN deposition of type I collagen mediated by the AT1 signaling pathway, which would then accelerate muscle cell proliferation and regeneration. In addition, the expression of FSTN was observed to be upregulated in the day 3 and 7 groups up to 2 wk after injury. It is well known that FSTN, a secreted protein, is able to bind and neutralize the actions of many members of the TGF-β superfamily of proteins. FSTN was first implicated in the regulation of follicle-stimulating hormone secretion in the pituitary and subsequently in other regions of the adult body associated with reproductive function (34). In skeletal muscle, FSTN stimulates satellite cell proliferation (9); moreover, FSTN gene therapy has shown promise for treating the diseased muscles of mdx mice (a mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy) through the inhibition of MSTN, which thereby increases muscle size, reduces fibrosis, and increases muscle strength (36). Our results support these latter findings since injured muscle-treated with Los shows an increase in FSTN expression, a decrease in MSTN expression, an increase in muscle regeneration, and a decrease in fibrosis formation; however, it remains unclear whether Los treatment acts directly by enhancing FSTN and inhibiting MSTN or whether it is completely through the upregulation of FSTN which then inhibits the action of MSTN, or possibly a combination of both.

The mechanism responsible for the dramatic differences observed in muscle healing between the day 3 treatment group and the other groups remains unclear, i.e., why does initiating the administration of 10 mg·kg−1·day−1 of Los at day 0 verses day 3 or day 7 postinjury have such a dramatic effect on the expression of FSTN in the skeletal muscle signaling pathways, with the day 3 group being significantly better than the control and day 0 groups at 1 wk and the days 3 and 7 group being better that these groups at 2 wk? In the current study, we considered the stages associated with the healing process of injured skeletal muscle to determine the timing of Los administration. The process of muscle healing includes degeneration and inflammation, which overlap in their timing, followed by muscle regeneration and finally with fibrosis deposition at the injury site (14); therefore, we decided to administer Los on day 0 (preinflammation), day 3 (early postinflammation), and day 7, which marks the beginning of the fibrotic stage. We posit that the regulation of MSTN is very important for muscle healing in the early stages of the process for proper skeletal muscle healing; hence, the timing of administering Los, using a safe human dose, is important for properly regulating MSTN expression after injury. We also suggest that there are some healing signals during the inflammation stage after muscle injury such as mitogen-activating protein kinase expression (16, 29, 35), so administering Los immediately after injury would interfere with this signaling pathway which is involved in the healing process; however, administering Los after the inflammation stage at 3 and 7 days postinjury would not interfere with this signaling pathway but would reduce MSTN expression later in the skeletal muscle healing process thereby inhibiting fibrosis formation. Additional investigation is essential to determine the exact mechanisms involved in the skeletal muscle healing process induced via Los muscle regenerative therapy.

Finally, one of the limitations of the current study was the physiological testing approach we chose to use since we could not completely separate the forces generated by the TA from the extensor digitorum longus; however, we believe it is more clinically relevant to measure the function of dorsi ankle flexion than only measuring the length of the TA muscle.

In summary, we have demonstrated that the administration of a high dose (300 mg·kg−1·day−1) of Los immediately after injury could accelerate muscle healing, but not when a human-equivalent dose, used for the treatment of hypertension (10 mg·kg−1·day−1), was administered immediately following injury. Interestingly, administering 10 mg·kg−1·day−1 of Los 3 or 7 days after skeletal muscle contusion injury could significantly enhance the structural and functional healing of skeletal muscle in mice. This study demonstrated that Los administered at a human-equivalent dosage concentration used to treat hypertension in humans can directly mediate the inhibition of MSTN and/or via the upregulation of FSTN, which then inhibits MSTN, or through a combination of both. This study suggests that the use of Los to expedite the muscle healing process could also be applied to other types of acute muscle injuries and may also be useful for the treatment of degenerative fibrotic muscle disorders.

GRANTS

Funding support was provided by Department of Defense Grants W81XWH-06-1-0406 and AFIRM: W81XWH-08-2-0032.

DISCLOSURES

Johnny Huard receives remuneration for consultancy and royalties from Cook Myostie, Inc.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

T.K., K.U., S.O., K.T., F.A., J.H.C., S.T., F.H.F., and J.H. conception and design of research; T.K., K.U., S.O., K.T., F.A., and S.T. performed experiments; T.K., K.U., S.O., K.T., F.A., J.H.C., S.T., and J.H. analyzed data; T.K., K.U., S.O., K.T., F.A., J.H.C., S.T., F.H.F., and J.H. interpreted results of experiments; T.K. and S.T. prepared figures; T.K., J.H.C., and J.H. drafted manuscript; T.K., K.U., S.O., K.T., F.A., J.H.C., S.T., F.H.F., and J.H. edited and revised manuscript; T.K., K.U., S.O., K.T., F.A., J.H.C., S.T., F.H.F., and J.H. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for the technical assistance of Nick Oyster, Bing Wang, Ying Tang, Jessica Tebbets, Michelle Witt, Ricardo Ferrari, Arvydas Usas, Yong Li, and Burhan Gharaibeh.

REFERENCES

- 1. Amthor H, Nicholas G, McKinnell I, Kemp CF, Sharma M, Kambadur R, Patel K. Follistatin complexes myostatin and antagonises myostatin-mediated inhibition of myogenesis. Dev Biol 270: 19–30, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bedair HS, Karthikeyan T, Quintero A, Li Y, Huard J. Angiotensin II receptor blockade administered after injury improves muscle regeneration and decreases fibrosis in normal skeletal muscle. Am J Sports Med 36: 1548–1554, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chan YS, Li Y, Foster W, Horaguchi T, Somogyi G, Fu FH, Huard J. Antifibrotic effects of suramin in injured skeletal muscle after laceration. J Appl Physiol 95: 771–780, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Crisco JJ, Jokl P, Heinen GT, Connell MD, Panjabi MM. A muscle contusion injury model. Biomechanics, physiology, and histology. Am J Sports Med 22: 702–710, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Criswell TL, Corona BT, Ward CL, Miller M, Patel M, Wang Z, Christ GJ, Soker S. Compression-induced muscle injury in rats that mimics compartment syndrome in humans. Am J Pathol 180: 787–797, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Diaz JA, Fischer DA, Rettig AC, Davis TJ, Shelbourne KD. Severe quadriceps muscle contusions in athletes. A report of three cases. Am J Sports Med 31: 289–293, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Foster W, Li Y, Usas A, Somogyi G, Huard J. Gamma interferon as an antifibrosis agent in skeletal muscle. J Orthop Res 21: 798–804, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fukushima K, Badlani N, Usas A, Riano F, Fu F, Huard J. The use of an antifibrosis agent to improve muscle recovery after laceration. Am J Sports Med 29: 394–402, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gilson H, Schakman O, Kalista S, Lause P, Tsuchida K, Thissen JP. Follistatin induces muscle hypertrophy through satellite cell proliferation and inhibition of both myostatin and activin. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 297: E157–E164, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goto K, Honda M, Kobayashi T, Uehara K, Kojima A, Akema T, Sugiura T, Yamada S, Ohira Y, Yoshioka T. Heat stress facilitates the recovery of atrophied soleus muscle in rat. Jpn J Physiol 54: 285–293, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goto K, Okuyama R, Sugiyama H, Honda M, Kobayashi T, Uehara K, Akema T, Sugiura T, Yamada S, Ohira Y, Yoshioka T. Effects of heat stress and mechanical stretch on protein expression in cultured skeletal muscle cells. Pflügers Arch 447: 247–253, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gremmler B, Kunert M, Schleiting H, Ulbricht LJ. Improvement of cardiac output in patients with severe heart failure by use of ACE-inhibitors combined with the AT1-antagonist eprosartan. Eur J Heart Fail 2: 183–187, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Haidet AM, Rizo L, Handy C, Umapathi P, Eagle A, Shilling C, Boue D, Martin PT, Sahenk Z, Mendell JR, Kaspar BK. Long-term enhancement of skeletal muscle mass and strength by single gene administration of myostatin inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 4318–4322, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huard J, Li Y, Fu FH. Muscle injuries and repair: current trends in research. J Bone Joint Surg Am 84-A: 822–832, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hurme T, Kalimo H. Activation of myogenic precursor cells after muscle injury. Med Sci Sports Exerc 24: 197–205, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Karalaki M, Fili S, Philippou A, Koutsilieris M. Muscle regeneration: cellular and molecular events. In Vivo 23: 779–796, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kasemkijwattana C, Menetrey J, Somogyl G, Moreland MS, Fu FH, Buranapanitkit B, Watkins SC, Huard J. Development of approaches to improve the healing following muscle contusion. Cell Transplant 7: 585–598, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kirk S, Oldham J, Kambadur R, Sharma M, Dobbie P, Bass J. Myostatin regulation during skeletal muscle regeneration. J Cell Physiol 184: 356–363, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kobayashi T, Goto K, Kojima A, Akema T, Uehara K, Aoki H, Sugiura T, Ohira Y, Yoshioka T. Possible role of calcineurin in heating-related increase of rat muscle mass. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 331: 1301–1309, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227: 680–685, 1970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Langley B, Thomas M, Bishop A, Sharma M, Gilmour S, Kambadur R. Myostatin inhibits myoblast differentiation by down-regulating MyoD expression. J Biol Chem 277: 49831–49840, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee SJ, McPherron AC. Regulation of myostatin activity and muscle growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 9306–9311, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li Y, Huard J. Differentiation of muscle-derived cells into myofibroblasts in injured skeletal muscle. Am J Pathol 161: 895–907, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li Y, Negishi S, Sakamoto M, Usas A, Huard J. The use of relaxin improves healing in injured muscle. Ann NY Acad Sci 1041: 395–397, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li ZB, Kollias HD, Wagner KR. Myostatin directly regulates skeletal muscle fibrosis. J Biol Chem 283: 19371–19378, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McCormick KM, Schultz E. Role of satellite cells in altering myosin expression during avian skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Dev Dyn 199: 52–63, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McCroskery S, Thomas M, Platt L, Hennebry A, Nishimura T, McLeay L, Sharma M, Kambadur R. Improved muscle healing through enhanced regeneration and reduced fibrosis in myostatin-null mice. J Cell Sci 118: 3531–3541, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McPherron AC, Lawler AM, Lee SJ. Regulation of skeletal muscle mass in mice by a new TGF-beta superfamily member. Nature 387: 83–90, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mendias CL, Bakhurin KI, Faulkner JA. Tendons of myostatin-deficient mice are small, brittle, and hypocellular. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 388–393, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Menetrey J, Kasemkijwattana C, Fu FH, Moreland MS, Huard J. Suturing versus immobilization of a muscle laceration. A morphological and functional study in a mouse model. Am J Sports Med 27: 222–229, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mezzano SA, Ruiz-Ortega M, Egido J. Angiotensin II and renal fibrosis. Hypertension 38: 635–638, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Negishi S, Li Y, Usas A, Fu FH, Huard J. The effect of relaxin treatment on skeletal muscle injuries. Am J Sports Med 33: 1816–1824, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nozaki M, Li Y, Zhu J, Ambrosio F, Uehara K, Fu FH, Huard J. Improved muscle healing after contusion injury by the inhibitory effect of suramin on myostatin, a negative regulator of muscle growth. Am J Sports Med 36: 2354–2362, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Patel K. Follistatin. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 30: 1087–1093, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Petersen MC, Greene AS. Angiotensin II is a critical mediator of prazosin-induced angiogenesis in skeletal muscle. Microcirculation 14: 583–591, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rodino-Klapac LR, Haidet AM, Kota J, Handy C, Kaspar BK, Mendell JR. Inhibition of myostatin with emphasis on follistatin as a therapy for muscle disease. Muscle Nerve 39: 283–296, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rossi CA, Flaibani M, Blaauw B, Pozzobon M, Figallo E, Reggiani C, Vitiello L, Elvassore N, De Coppi P. In vivo tissue engineering of functional skeletal muscle by freshly isolated satellite cells embedded in a photopolymerizable hydrogel. FASEB J 25: 2296–2304, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sasaki M, Uehara S, Ohta H, Taguchi K, Kemi M, Nishikibe M, Matsumoto H. Losartan ameliorates progression of glomerular structural changes in diabetic KKAy mice. Life Sci 75: 869–880, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schultz E, McCormick KM. Skeletal muscle satellite cells. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 123: 213–257, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sharma M, Kambadur R, Matthews KG, Somers WG, Devlin GP, Conaglen JV, Fowke PJ, Bass JJ. Myostatin, a transforming growth factor-beta superfamily member, is expressed in heart muscle and is upregulated in cardiomyocytes after infarct. J Cell Physiol 180: 1–9, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tamhane AC, Hochberg Y, Dunnett CW. Multiple test procedures for dose finding. Biometrics 52: 21–37, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tharaux PL, Chatziantoniou C, Fakhouri F, Dussaule JC. Angiotensin II activates collagen I gene through a mechanism involving the MAP/ER kinase pathway. Hypertension 36: 330–336, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Uehara K, Goto K, Kobayashi T, Kojima A, Akema T, Sugiura T, Yamada S, Ohira Y, Yoshioka T, Aoki H. Heat-stress enhances proliferative potential in rat soleus muscle. Jpn J Physiol 54: 263–271, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wagner KR, Liu X, Chang X, Allen RE. Muscle regeneration in the prolonged absence of myostatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 2519–2524, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang BW, Chang H, Kuan P, Shyu KG. Angiotensin II activates myostatin expression in cultured rat neonatal cardiomyocytes via p38 MAP kinase and myocyte enhance factor 2 pathway. J Endocrinol 197: 85–93, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Williams DA. A test for differences between treatment means when several dose levels are compared with a zero dose control. Biometrics 27: 103–117, 1971 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhu X, Topouzis S, Liang LF, Stotish RL. Myostatin signaling through Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4 is regulated by the inhibitory Smad7 by a negative feedback mechanism. Cytokine 26: 262–272, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]