Abstract

HuR promotes myogenesis by stabilizing the MyoD, Myogenin and p21 mRNAs during the fusion of muscle cells to form myotubes. Here we show that HuR, via a novel mRNA destabilizing activity, promotes the early steps of myogenesis by reducing the expression of the cell cycle promoter nucleophosmin (NPM). Depletion of HuR stabilizes the NPM mRNA, increases NPM protein levels and inhibits myogenesis, while its overexpression elicits the opposite effects. NPM mRNA destabilization involves the association of HuR with the decay factor KSRP as well as the ribonuclease PARN and the exosome. The C-terminus of HuR mediates the formation of the HuR-KSRP complex and is sufficient for maintaining a low level of the NPM mRNA as well as promoting the commitment of muscle cells to myogenesis. We therefore propose a model whereby the downregulation of the NPM mRNA, mediated by HuR, KSRP and its associated ribonucleases, is required for proper myogenesis.

Introduction

Muscle differentiation, also known as myogenesis, represents a vital process that is activated during embryogenesis and in response to injury to promote the formation of muscle fibers 1,2. Myogenesis requires the activation of muscle-specific promyogenic factors that are expressed at specific steps of the myogenic process and act in a sequential manner. We and others have demonstrated that the expression of genes encoding some of these promyogenic factors such as MyoD, myogenin and the cyclin-dependent kinase p21, are not only regulated at the transcriptional level but are also modulated posttranscriptionally 3–8. Indeed, modulating the half-lives of these mRNAs plays an important role in their expression. The RNA-binding protein HuR, via its ability to bind specific AU-rich elements (AREs) in the 3′untranslated regions (3′UTRs) of these mRNAs, protects them from the AU-rich-mediated decay (AMD) machinery 4,5,7–9. This HuR-mediated stabilization represents a key regulatory step that is required for the expression of these promyogenic factors and proper myogenesis.

HuR, a member of the ELAV family of RNA binding proteins, specifically binds to AREs located in the 3′UTRs of its target transcripts8–12 leading to their stability that, which in turn enhances the expression of the encoded proteins 5,7. In addition to mRNA stability, HuR modulates the nucleocytoplasmic movement and the translation of target transcripts 13–16. Our previous data have indicated that HuR associates with MyoD, Myogenin and p21 transcripts only during the fusion step of myoblasts to form myotubes 5. This finding led to the conclusion that HuR promotes myogenesis by stabilizing these mRNAs specifically at this step. In the same study however, we showed that depleting HuR from proliferating myoblasts prevented their initial commitment to the differentiation process. These observations indicated that HuR promotes muscle fiber formation by also regulating the expression of target mRNAs during the early steps of myogenesis.

Recently, we discovered that HuR promotes myogenesis through a novel regulatory mechanism involving its caspase-mediated cleavage 4. As muscle cells are engaged in the myogenic process a progressive accumulation of HuR in the cytosol is triggered. In the cytoplasm, HuR is cleaved by caspase-3 at its 226th residue, an Asp (D), generating two cleavage products (HuR-CPs: -CP1, 24kDa and -CP2, 8kDa). These HuR-CPs, generated from ~50% of cytoplasmic HuR, are required for muscle fiber formation 4,8. Indeed, while wtHuR can rescue myogenesis in cells depleted of endogenous HuR, the non-cleavable HuRD226A mutant failed to do so 4,8. Additionally, HuR-CP1, by associating with import factor transportin 2 (TRN2), prevents HuR nuclear import promoting its cytoplasmic accumulation. While these data clearly establish that HuR-CP1 modulates the cellular movement of HuR during myogenesis, the role of HuR-CP2 remains unclear.

HuR is not the only RNA binding protein involved in the posttranscriptional regulation of promyogenic factors. The KH-type splicing regulatory protein (KSRP) is known to associate, in proliferating myoblasts, with the AREs of the Myogenin and p21 mRNAs leading to their rapid decay 3. By doing so, KSRP participates in ensuring the proliferation of myoblasts and prevents their premature commitment to the myogenic process. KSRP promotes mRNA decay in muscle cells by recruiting ribonucleases such as PARN and members of the exosome complex (e.g. EXOSC5) to ARE-containing mRNAs such as Myogenin and p21 3,17. It was also suggested that when myoblasts become competent for differentiation, KSRP releases Myogenin and p21 mRNAs leading to their stabilization. As a consequence, myoblasts enter myogenesis and fuse to form myotubes 3. Since at this same step HuR associates with and stabilizes these ARE-bearing mRNAs 5,7, we concluded that the induction of myogenesis involve both KSRP and HuR that modulate the expression of the same mRNAs in an opposite way but at different myogenic steps.

Surprisingly, however, here we report that in undifferentiated muscle cells HuR and KSRP do not compete but rather collaborate to downregulate the expression of a common target, the Nucleophosmin (NPM, also known as B23) mRNA. HuR forms a complex with KSRP that is recruited to a U-rich element in the 3′UTR of NPM mRNA. The HuR/KSRP complex, in collaboration with PARN and the exosome, then destabilizes the NPM mRNA leading to a significant reduction in NPM protein levels. Our data also provide evidence supporting the idea that the HuR/KSRP-mediated decrease of NPM expression represents one of the main events that helps myoblasts commit to the myogenic process.

Results

NPM is a HuR-mRNA target in undifferentiated muscle cells

We first identified the mRNAs that depend on HuR for their expression in undifferentiated, C2C12 cells. Endogenous HuR was depleted (siHuR) or not (siCtr) from these cells and total RNA was then prepared and hybridized to mouse arrays containing 17,000 probe sets of known and unknown expressed sequence tags.. Consistent with the fact that HuR acts as a stabilizer for many of its mRNA targets 10,12 we observed a significant decrease in the steady-state levels of 18 mRNAs in siHuR-treated cells. Surprisingly, however, we found that 12 mRNAs are significantly upregulated in these cells (Supplementary Table 1). While many of these transcripts do not have typical AREs and are not known to modulate myogenesis, these observations suggested that in muscle cells HuR, in addition to stabilizing some of its target mRNAs, could also be involved in the destabilization of other transcripts. Therefore, we investigated further this unexpected possibility and assessed whether this HuR destabilizing activity is part of its promyogenic function. To this end we chose to study, among these upregulated HuR mRNA targets, the nucleophosmin (NPM) mRNA. NPM was identified as a target of HuR in other cell systems 18 and its downregulation has been shown to be required for the differentiation of other cell models 19,20. Hence, moderating NPM expression in muscle cells could be one of the early events through which HuR promotes myogenesis.

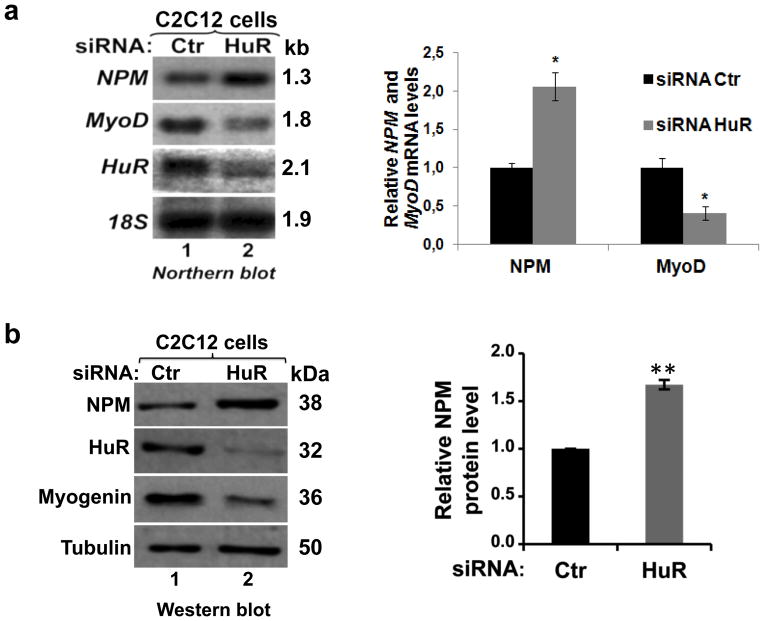

First, we validated the results of our microarray data using Northern blot analysis. The knockdown of HuR in C2C12 cells increased the level of NPM mRNA by two fold while, as previously described 5, it decreased the level of MyoD mRNA by >50% (Fig. 1a). Knocking down HuR in these cells also increased NPM protein levels, while Myogenin protein levels were reduced (Fig. 1b). Conversely, overexpressing GFP-HuR protein in C2C12 cells significantly decreased the levels of both NPM mRNA and protein, compared to cells transfected with GFP only (Supplementary Fig. 1). Together these observations establish that in undifferentiated muscle cells HuR prevents the overexpression of NPM mRNA and protein.

Figure 1. HuR regulates NPM expression in muscle cells.

Exponentially growing C2C12 myoblasts were transfected with the HuR or Control (Ctr) siRNAs. (a) RNA was prepared 48h after transfection with HuR or Ctr siRNAs. Northern blotting was performed using radiolabeled probes against NPM, MyoD, HuR mRNAs and 18S (loading control). The band intensities of NPM, MyoD mRNAs and 18S were determined using ImageQuant Software. The NPM and MyoD mRNA levels were normalized on 18S rRNA level. (b) Forty-eight h after transfection with HuR or Ctr siRNAs whole-cell extracts were prepared and Western blotting was performed using antibodies against NPM, HuR, myogenin and α-tubulin (loading control). ImageQuant was used to determine the NPM level, normalized on α-tubulin level. In the histograms, the siRNA HuR condition was plotted relative to the siRNA Ctr condition +/− the standard error of the mean (S.E.M.) of three independent experiments *P<0.01, **P<0.001 (t test).

HuR-mediated NPM mRNA destabilization promotes myogenesis

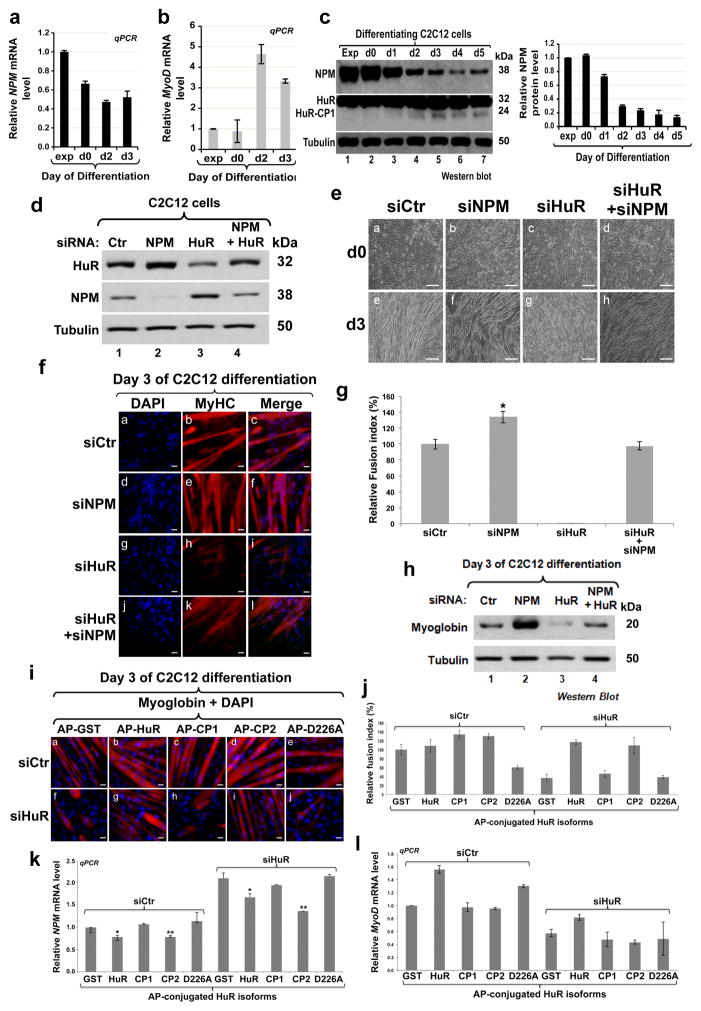

If downregulating NPM levels represent an important event during the early steps of myogenesis, decreasing its expression levels in C2C12 cells should promote their ability to enter this process. To investigate this possibility, we assessed NPM mRNA and protein levels during muscle cell differentiation. We observed that although, as expected 21, MyoD mRNA levels increased during this process, the abundance of the NPM mRNA and protein significantly decreased as soon as myogenesis was initiated (Figs. 2a–c). To determine whether decreasing NPM expression is required for the initiation of myogenesis, we tested the impact that NPM knockdown (Fig. 2d) could have on the ability of C2C12 cells, expressing or not HuR, to enter this process. We observed that the depletion of endogenous NPM by siRNA not only triggered the formation of more and larger muscle fibers when compared to siCtr-treated cells, but also reestablished myogenesis in HuR-knockdown C2C12 cells (Figs. 2d–h and Supplementary Fig 2). These observations, together with the fact that overexpressing GFP-NPM prevented myogenesis (Supplementary Fig. 3), clearly demonstrate that one way by which HuR promotes the early steps of muscle fibers formation is by downregulating NPM expression.

Figure 2. Reducing NPM level is required for the commitment of muscle cells into the myogenic process.

(a–b) Total RNA was isolated from exponentially growing (exp) or confluent C2C12 myoblasts (day 0) and during the differentiation process (days 1 to 3). (a) NPM and (b) MyoD mRNA levels, determined by RT-qPCR, were standardized against GAPDH mRNA and expressed relative to the exponential condition. Values were plotted +/− the S.E.M. of three independent experiments. (c) Total cell extracts were prepared from growing (exp) as well as differentiating C2C12 myoblasts (days 1 to 5) and used for Western blotting with antibodies against NPM, HuR or α-tubulin (loading control). The NPM protein level was determined using the Imagequant software, standardized against tubulin levels and plotted relative to the exponential condition +/− the S.E.M. of three independent experiments. (d–h) Knockdown of HuR, NPM and NPM+HuR was performed in C2C12 cells and differentiation was induced 48 hours post treatment with siRNAs. (d) Total cell lysates were prepared 48 hours posttransfection and used for Western blotting with antibodies against NPM, HuR, and α-tubulin. (e) Phase contrast pictures showing the differentiation status at d0 and d3. Bars, 50μm. (f) Immunofluorescence (IF) experiments were performed using the anti-My-HC antibody and DAPI staining. Images of a single representative field were shown. Bars, 10μm. (g) The fusion index (calculated from three independent experiments) was determined for muscle fibers shown in (f). (h) Total cell extracts were prepared from the cells described above and used for Western blotting analysis using antibodies against myoglobin and α-tubulin. (i–l) C2C12 cells depleted or not of HuR were treated twice (see Methods) with 50nM AP-GST, -HuR-GST, -CP1-GST, -CP2-GST or -HuRD226A-GST and 24h after the second treatment with these chimera they were induced for differentiation. (i) Immunofluorescent images and (j) fusion index of fibers fixed on day 3 of differentiation process. Bars, 10μm. (k–l) NPM (k) and MyoD (l) mRNA levels in confluent myoblasts treated as described above. mRNA levels were plotted relative to the GST-and siCtr-treated conditions +/− the S.E.M. of three independent experiments. For histograms in Figures 2g,k *P<0.01, **P<0.001 (t test).

We have previously shown that HuR is cleaved during muscle cell differentation into two cleavage products HuR-CP1 (24 kDa) and HuR-CP2 (8 kDa). Our data also indicated that HuR cleavage is a key regulatory event required for proper muscle fiber formation 4. Since our data (Fig. 2c) have shown that the cleavage of HuR during myogenesis correlates with a decrease in NPM expression, we decided to investigate the effect of HuR-CPs on NPM expression in muscle cells. As expected we observed that in muscle cells depleted of endogenous HuR, the wild type (wt-HuR) but not the non-cleavable isoform of HuR (HuRD226A) was able to reestablish myogenesis as well as the downregulation of the steady state level of the NPM mRNA. Surprisingly however, HuR-CP2 but not HuR-CP1 was also able to reestablish, in these cells, the downregulation of NPM mRNA levels and myogenesis similarly to wt-HuR (Figs. 2i–l). While these results suggest a correlation between HuR cleavage and the HuR-mediated downreglation of the NPM transcript, they clearly indicate that the C-terminus of HuR could play an important role in this effect.

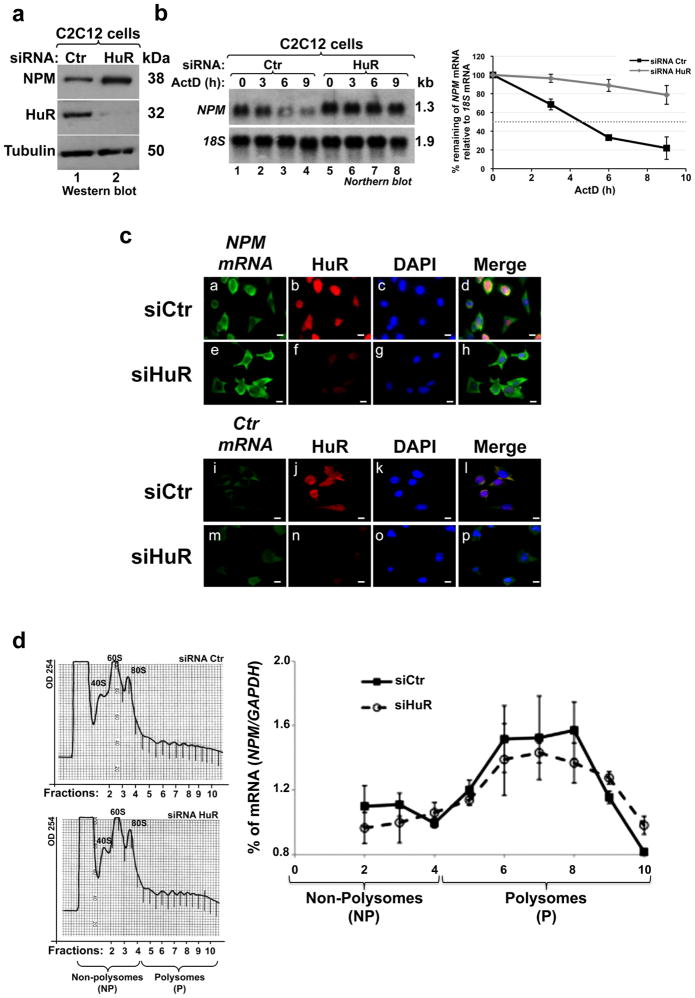

In order to identify the mechanisms responsible for the decreased expression of NPM mRNA during myogenesis (Fig. 2a), we first performed a nuclear run-on assay 22 to assess whether this decrease is due to a change in transcription. Since we did not observe any change in the transcription rate during myogenesis (Supplementary Fig. 4), we concluded that the HuR-mediated downregulation of NPM mRNA expression is likely to occur at the level of mRNA stability. Indeed, a pulse-chase experiment 23 using the RNA polymerase II inhibitor Actinomycin D (ActD), showed that depleting HuR in C2C12 cells significantly increased, from ~5h to >9 h, the half-life of the NPM mRNA (Fig. 3a–b). Of note, treatment of cells with ActD did not affect their viability (Supplementary Fig. 5). These results, together with the fact that HuR does not affect the localization or the translation of the NPM mRNA (Figs. 3c–d), indicates that HuR promotes the formation of muscle fibers by destabilizing the NPM mRNA.

Figure 3. HuR regulates the stability of the NPM mRNA.

(a) Total extracts from C2C12 myoblasts treated with siRNA HuR or siRNA Ctr were used for western blot analysis to detect NPM, HuR, and α-tubulin (loading control). Representative gel of three independent experiments. (b) RNA was prepared from C2C12 transfected with HuR or Ctr siRNAs (for 48h), and then treated with ActD for 0, 3, 6 or 9 hours. Northern blot analysis was performed using radiolabeled probes against NPM mRNA and 18S rRNA (loading control). NPM and 18S band intensities were measured using ImageQuant and the stability of NPM mRNA was determined relative to the 18S for each time point. NPM signal in each one of these time points was compared to NPM level at 0h of ActD treatment, which is considered 100%. These percentages were then plotted +/− S.E.M of three independent experiments. (c) C2C12 cells transfected with siRNA HuR or siRNA Ctr were fixed, permeabilized, and incubated with digoxigenin-labeled in vitro transcribed antisense probe to detect NPM mRNA (panels a, e) and with sense RNA probe (panels i, m) as a control (Ctr probe). IF staining with anti-HuR antibody (panels b, f, j and n) and with DAPI was performed. A single representative field for each cell treatment is shown. Bars, 10μm. (d) 48h posttransfection of exponentially growing C2C12 cells with siRNA HuR or Ctr, polysomes were fractionated through sucrose gradients (15–50% sucrose). Absorbance at wavelength 254 nm was measured in order to determine the profile of polysome distribution. 10 fractions were collected and divided in two groups to non-polysome (NP, fractions 1–4) and polysome (P, fractions 5–10, contain mRNAs engaged in translation) (left panel). RT-qPCR was performed on each fraction using specific primers for NPM and GAPDH mRNAs (right panel). NPM mRNA level was standardized against GAPDH mRNA in each fraction and plotted +/− S.E.M of three independent experiments.

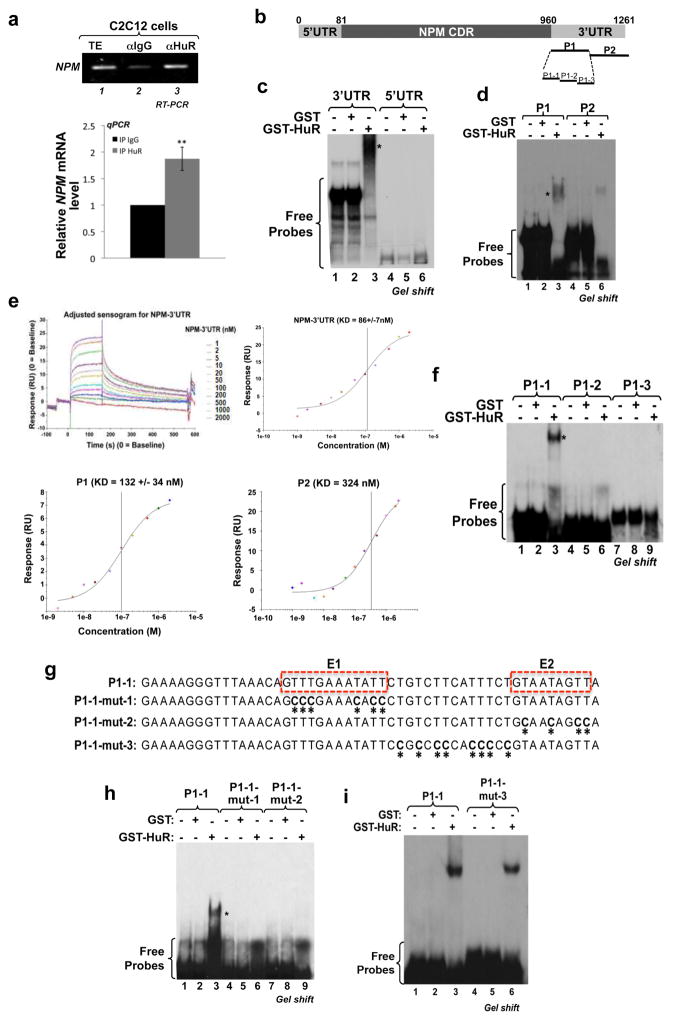

HuR destabilizes the NPM mRNA via U-rich elements in the 3′UTR

HuR is known to regulate its mRNAs targets by interacting with AU-/U-rich elements in their 3′UTRs 9,24. Therefore, to define the molecular mechanism by which HuR destabilizes the NPM mRNA, we first assessed whether HuR and NPM mRNA associate in muscle cells. Immunoprecipitation (IP) (Fig. 4a) followed by RT-PCR (upper panel) or RT-qPCR (lower panel) analyses 23,25 showed that HuR and the NPM mRNA coexist in the same complex in muscle cells. In order to determine whether this association is direct or indirect, we performed RNA electromobility shift assays (REMSAs) 23 using recombinant GST or GST-HuR proteins and radiolabeled RNA probes corresponding to the entire 5′ or 3′ UTRs of NPM mRNA (Fig. 4b). We observed that GST-HuR forms a complex only with the 3′ but not the 5′ UTR of NPM mRNA (Fig. 4c). To further define the binding site(s) of HuR, we divided the NPM 3′UTR into 2 probes, P1 and P2 (Fig. 4b) and observed a strong association of GST-HuR with only the P1 probe (Fig. 4d). Using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis, we confirmed these associations and showed that GST-HuR bound to the NPM-3′UTR and P1 probe with higher affinity (dissociation constants (KD) of 86 × 10−9 M and 132 × 10−9 M respectively) than the P2 probe (KD = 324 × 10−9 M) (Fig. 4e). In addition, further subdivision of P1 and 2 probes into three smaller regions, P1/2-1, -2 and -3, showed that HuR only binds to the P1-1 region of NPM-3′UTR (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Figs.6a–b). Analysis of the secondary structure of the P1-1 region, using the mfold prediction software for mRNA folding 26 indicated the existence of two U-rich elements (E1 and E2) similar to HuR cis-binding motifs previously identified in other mRNA targets 11,23,26 (Supplementary Fig. 6c). To determine whether E1 and/or E2 elements mediate the binding of HuR to the NPM 3′UTR, we mutated each one of their uracils (Us; shown as Ts) as well as those of the element separating E1 and E2 to cytosine (C) (Fig. 4g) and performed REMSA experiments as described above. Since mutating each site separately (P1-1-mut-1 or -mut-2) but not those of the hinge element (P1-1-mut-3), equally disrupted the P1-1/HuR complex (Figs. 4h–i), we concluded that the E1 and E2 elements together constitute the minimum U-rich-element required for the direct binding of HuR to the NPM-3′UTR.

Figure 4. HuR binds to the NPM mRNA via two U-rich sequences within the 3′UTR.

(a) IP experiments were performed using the monoclonal HuR antibody (3A2), or IgG as a control, on total cell lysates (TE) from C2C12 cells. RNA was isolated from the immunoprecipitate, and RT-PCR or RT-qPCR was performed using primers specific for NPM and RPL32 mRNAs. The agarose gel (Upper panel) shown is representative of three independent experiments. For RT-qPCR (lower panel), NPM mRNA levels were standardized against RPL32 mRNA levels. The normalized NPM mRNA levels were plotted relatively to the IgG IP condition +/− S.E.M. of three independent experiments **P<0.001 (t test). (b) Schematic representation of the NPM mRNA sequence. The probes covering the NPM 3′UTR (P1, P2, P1-1 to P1-3) used to generate radiolabeled RNA probes for RNA eletromobility shift assays are indicated (black lanes). (c–d, f and h–i) Gel-shift binding assays were performed by incubating 500 ng of purified GST or GST-HuR protein with the radiolabeled cRNA (c) 3′UTR and 5′UTR, (d) P1 and P2, (f) P1-1 to P1-3, (h) P1-1, P1-1-mut1 and P1-1-mut2, (i) P1-1 and P1-1-mut3 probes. These gels are representative of three independent experiments. (e) BIACORE, a surface plasmon resonance (SPR)-based biosensor technology, was used for a kinetic binding study between GST-HuR and NPM 3′UTR, P1 or P2 probes. GST-HuR was captured on a Series S CM5 chip and increased concentrations of NPM cRNA probes, as indicated, were injected over the surface. Injections were performed for 150s, to measure association, followed by a 400s flow of running buffer to assess dissociation. The association/dissociation ratio of GST-HuR to NPM 3′UTR is shown in the sensorgram (top left panel). The binding affinity (KD) of GST-HuR to NPM 3′UTR (top right panel), P1 or P2 (bottom panels) cRNA probes is also shown. (g) Nucleotide sequence of probe P1-1 showing the thymidine (T) residues that were mutated to cytidine (C) residues (identified by asterisks) to generate the P1-1-mut1, P1-1-mut2 and P1-1-mut3. The sequences highlighted by the dashed boxes as E1 and E2 are the single-strand AU-rich sequences identified using mfold software. * shown in panels 4c, f and h indicate the location of shifted complex.

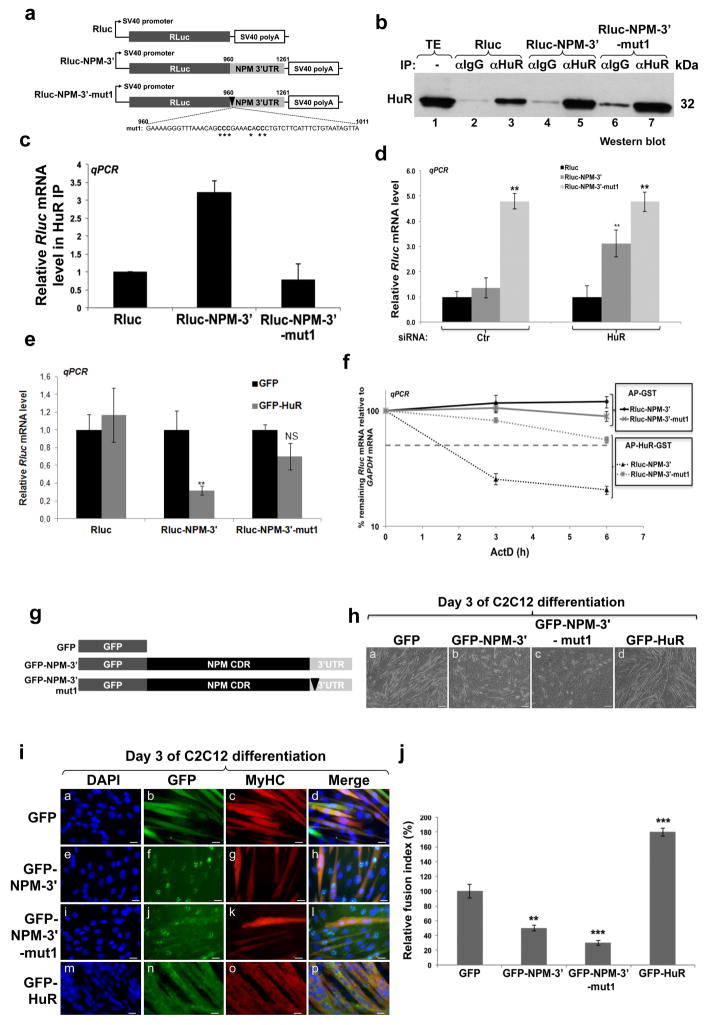

Next, we tested whether these U-rich elements are involved in the HuR-mediated destabilization of the NPM mRNA in muscle cells. We generated reporter cDNA plasmids expressing the Renilla Luciferase (Rluc) in which we inserted, at the 3′end, either the wild type NPM 3′UTR (Rluc-NPM-3′) or the NPM 3′UTR mutant 1 (Rluc-NPM-3′-mut1, deficient in its ability to bind HuR) (Fig. 4h and 5a). An IP/RT-qPCR experiment showed that the association between HuR and the Rluc-NPM-3′ mRNA is significantly higher than its association with the control reporters Rluc or Rluc-NPM-3′-mut1 (Figs. 5b–c). We next assessed the impact of depleting endogenous HuR on the expression of the Rluc-NPM-3′ mRNA. siCtr- or siHuR-treated C2C12 cells were transfected with the Rluc, Rluc-NPM-3′ or Rluc-NPM-3′-mut1 plasmids (Supplementary Fig. 7a) and the steady state levels of these mRNAs were determined by RT-qPCR analysis. While we observed a 3.5 fold increase in the level of the Rluc-NPM-3′ mRNA in cells depleted of HuR but not in those treated with siCtr, the levels of Rluc-NPM-3′-mut1 remained high in both cell types (Fig. 5d). On the other hand, overexpressing GFP-HuR in C2C12 cells decreased the level of the Rluc-NPM-3′ mRNA by >65% but had no significant effect on the levels of Rluc or Rluc-NPM-3′-mut1 mRNAs (Fig. 5e, Supplementary Fig. 7c). The effect of knocking down or overexpressing HuR on luciferase activity (which is proportional to Rluc protein levels) was similar to those seen for the mRNA levels (Supplementary Figs.7b,d). Next, we investigated the functional relevance of these HuR binding sites on NPM mRNA stability. We performed ActD pulse-chase experiments on C2C12 cells expressing the various Rluc reporters described above and treated or not with 50nM of recombinant HuR conjugated to the cell-permeable peptide Antenapedia (AP) 14 (Fig. 5f). We observed that the half-life of the Rluc-NPM-3′ mRNA was significantly reduced (<2h) only in cells treated with AP-HuR-GST but not in those treated with AP-GST (>6h). However, the Rluc-NPM-3′-mut1 mRNA remained stable under all treatments (half-life >6h). While these results clearly demonstrate that an intact HuR binding sites is required for HuR-induced destabilization of the NPM mRNA, it does not provide any indication on their relevance during myogenesis. To address this question, we generated GFP-conjugated full-length wild type (GFP-NPM-3′) or mutated (GFP-NPM-3′-mut1) isoforms of NPM (Fig. 5g). These NPM isoforms were then overexpressed in C2C12 cells and 48h later these cells were induced for differentiation during 3 days. Our experiments showed that overexpressing GFP-NPM-3′ reduced the efficiency of muscle fiber formation by ~50% when compared to GFP alone (Figs. 5h–j). Interestingly, the overexpression of the GFP-NPM-3′-mut1 isoform, that does not bind HuR, provided a much higher inhibition of myogenesis efficiency than GFP-NPM-3′ (>70%). Together these results show that the recruitment of HuR to the E1 and E2 U-rich elements of NPM 3′UTR is required for NPM downregulation and the promotion of myogenesis.

Figure 5. An intact P1-1 element is required for HuR-mediated regulation of NPM expression.

(a) Schematic diagram of the renilla luciferase reporters used in the experiments described in Figs.5a–f. (b–c) Exponentially growing C2C12 cells were transfected with plasmids expressing Rluc, Rluc-NPM-3′ or Rluc-NPM-3′-mut1. Total extracts from these cells were prepared 24 h after transfection and used for IP using the anti-HuR antibody (3A2) or IgG as a control. (b) Western blotting analysis with the anti-HuR antibody was performed using these IP samples. (c) Rluc mRNA associated with the immunoprecipiated HuR was determined by RT-qPCR. The relative Rluc RNA levels from Rluc-NPM-3′ and Rluc-NPM-3′-mut1 were plotted relatively to the Rluc RNA reporter +/− S.E.M. of three independent experiments. (d–e) The expression levels of these Rluc RNA reporters were also determined by RT-qPCR in C2C12 cells depleted or not of HuR (d) or overexpressing GFP or GFP-HuR (e). The expression levels of the Rluc mRNAs were normalized over total Rluc DNA transfected as described 59 and then standardized against GAPDH mRNA level +/− S.E.M. of three independent experiments *P<0.01, **P<0.001, NS: Non significant (t test). (f) C2C12 cells were transfected with the Rluc reporter RNA described above in the presence of AP-GST or AP-HuR-GST proteins. The stability of these reporter Rluc mRNAs was determined by AcD pulse-chase experiments. The percentages shown were plotted +/− S.E.M of three independent experiments. (g) Schematic diagram of GFP or the GFP-conjugated full-length NPM isoforms: WT NPM (GFP-NPM-3′) and the NPM 3′UTR with the first AU rich sequence mutated (GFP-NPM-3′-mut1). The coding region of NPM is shown as NPM CDR. (h–j) C2C12 cells expressing these isoforms or the GFP-HuR protein were fixed on day 3 of muscle cell differentiation. (h) Phase contrast images of the myotubes described above. (i) IF (using the anti-My-HC antibody) images of these myotubes were used to calculate the fusion index +/− S.E.M. (j) of three independent experiments **P<0.001, ***P<0.0001, (t test). Images of a single representative field are shown. Bars, 50μm for (h) and 10μm for (i).

HuR destabilizes the NPM mRNA in a KSRP dependent manner

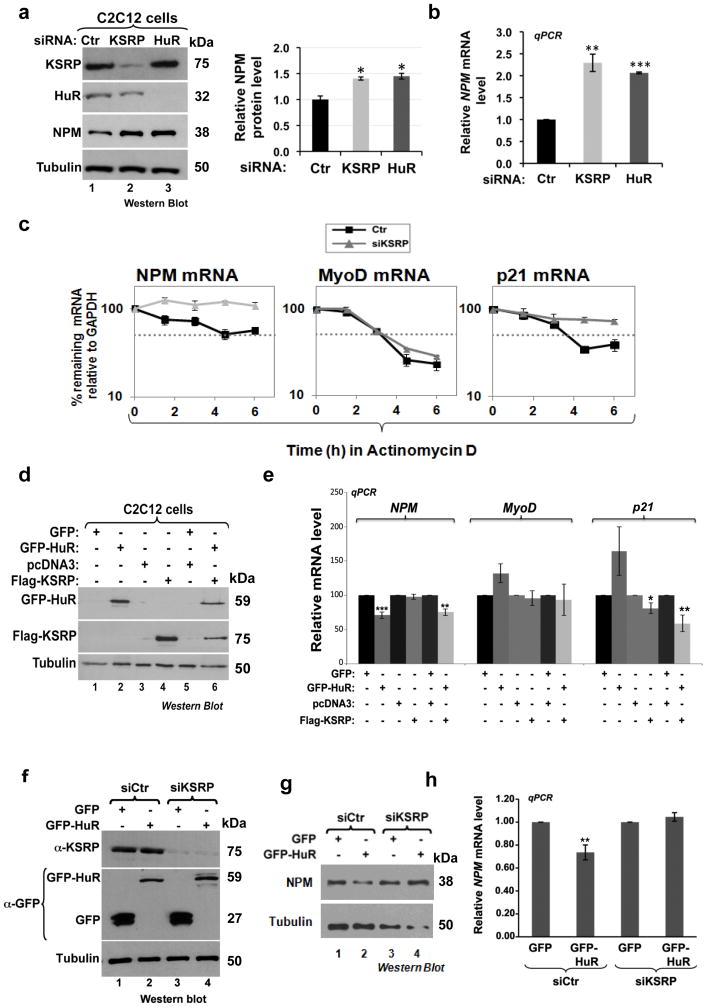

It has been shown that during myogenesis transcripts such as Myogenin and p21 but not MyoD are destabilized by KSRP in proliferating myoblasts 3. However, at later stages (fusion step) these mRNAs are stabilized by HuR, leading to an increase in their expression levels and to the promotion of myotube formation 5,7. Therefore, since KSRP and HuR target common transcripts in muscle cells 3,5,7 and our observation showed that depleting the expression of either of these two proteins in C2C12 cells equally prevented myogenesis (Supplementary Fig. 8), we tested whether KSRP could be implicated in the HuR-mediated destabilization of the NPM mRNA in proliferating C2C12 cells. We first determined the effect KSRP depletion could have on the expression level of the NPM mRNA and protein. We showed that, similarly to HuR depletion, the knockdown of KSRP significantly increased the expression levels of NPM mRNA (>2 fold) and protein (>1.5 fold) (Figs. 6a–b). Additionally, ActD pulse chase experiments indicated that the knocking down KSRP increased the half-life of NPM mRNA to a similar extent than HuR (compare Fig. 3b to 6c). However, as expected 3, KSRP knockdown had no effect on the stability of the MyoD mRNA, while it increased the half-life of p21 mRNA from ~3.6h to >6h (Fig. 6c). Altogether, these data show that both HuR and KSRP decrease the expression level of the NPM protein by shortening the half-life of the NPM mRNA. Surprisingly we additionally observed that overexpressing KSRP alone in C2C12 cells, unlike HuR, does not affect NPM mRNA or protein levels (Figs. 6d–e) despite promoting the decreased expression of p21. Since knocking down KSRP by >90% prevented the HuR-mediated decrease of the NPM mRNA and protein (Figs. 6f–h), we concluded that although KSRP alone is not able to destabilize NPM mRNA, KSRP is required for the HuR-mediated down-regulation of NPM level in muscle cells.

Figure 6. KSRP is required for the HuR-mediated destabilization of NPM mRNA.

(a–b) Exponentially growing C2C12 cells were treated with siRNA Ctr or siRNA against HuR or KSRP. Total cell (a) or RNA (b) extracts from these cells were prepared 48 hours after transfection. (a) Western blotting analysis was performed using antibodies to detect KSRP, NPM, HuR and α-tubulin (loading control). (b) RT-qPCR analysis was performed to assess NPM mRNA levels which were standardized against GAPDH mRNA. The levels of NPM protein (a) or mRNA (b) in cells depleted of HuR or KSRP were plotted relative to the siRNA Ctr condition +/− the S.E.M. of three independent experiments. (c) The stability of the NPM, MyoD and p21 mRNA in C2C12 depleted or not of KSRP was determined by AcD pulse-chase experiments. RT-qPCR analysis was performed using specific primers for these three mRNAs. mRNA levels were then standardized against GAPDH mRNA and plotted +/− S.E.M of three independent experiments. (d–e) Exponentially growing C2C12 cells were transfected with the pcDNA3, pcDNA-Flag-KSRP, GFP and GFP-HuR. (d) Total cell extracts or (e) RNA extracts from these cells were prepared 24h posttransfection. (d) Western blotting was performed using antibodies against Flag, HuR, or α-tubulin (loading control). (e) RT-qPCR analysis was performed as described above in 6c and mRNA levels were plotted relative to their levels in control cells +/− the S.E.M. of three independent experiments. (f–h) GFP and GFP-HuR plasmids were transfected in C2C12 cells depleted or not of KSRP. 24 h later total protein extracts and RNA were prepared. (f–g) Western blotting analysis was performed with antibodies against (f) KSRP, GFP and (g) NPM. α-tubulin levels were assessed as a loading control in both (f) and (g). (h) RT-qPCR analysis was performed as described above. NPM mRNA levels were standardized against GAPDH mRNA level. In each condition the level of NPM mRNA in siKSRP treated cells was plotted relative to its levels in siRNA Ctr-treated and GFP-transfected cells +/− the S.E.M. of three independent experiments. In the histograms presented in Figures 6a,b,e,h *P<0.01, **P<0.001, ***P<0.0001 (t test).

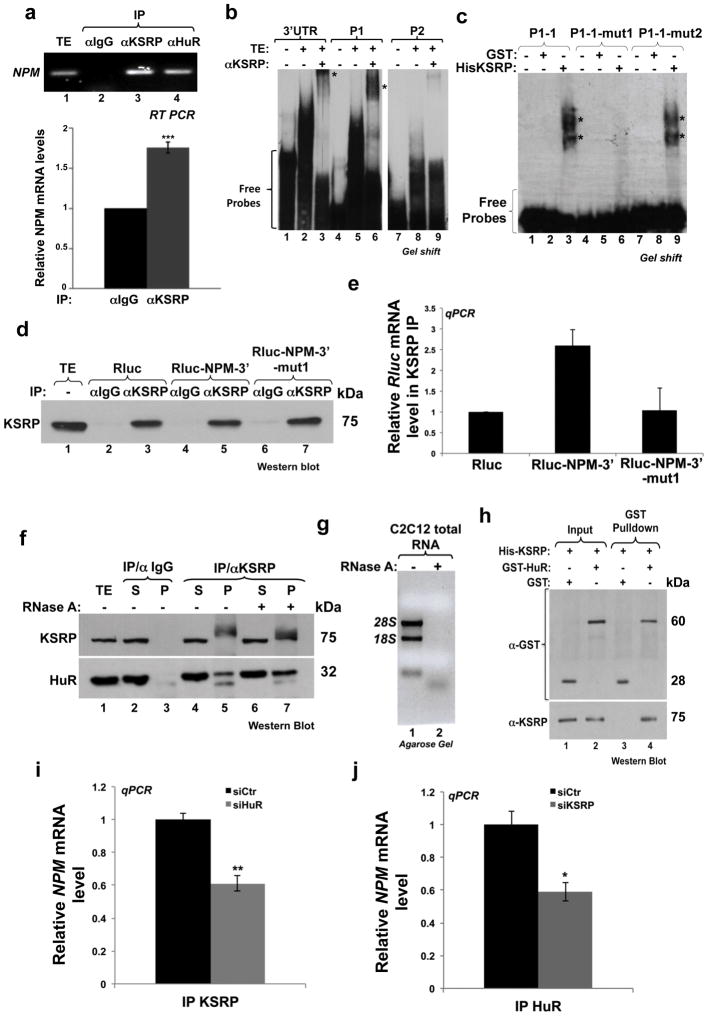

To gain insight into the molecular mechanisms by which HuR and KSRP affect the fate of NPM mRNA in muscle cells, we first determined whether KSRP also associates with this transcript. IP experiments using the anti-KSRP antibody 17 followed by RT-PCR and -qPCR analyses showed that KSRP binds to the NPM mRNA similarly to HuR (Figs. 7a and 4a). REMSA using total extracts prepared from C2C12 cells that were incubated with radiolabeled NPM-3′UTR or the P1 or P2 probes (Fig. 4b) and with the anti-KSRP antibody showed that, similarly to HuR (Fig. 4), KSRP associates with the 3′UTR of NPM through the P1 but not the P2 region (Fig. 7b). To determine the KSRP binding site(s) in the NPM 3′UTR, we incubated the recombinant KSRP with intact or mutated radiolabeled P1 probes and performed the same REMSA experiments described in Figure 4. KSRP formed complexes with P1-1 and P1-1-mut2 but not with P1-1-mut1 (mut-E1) probes (Fig. 7c). In addition, IP experiments with anti-KSRP antibody were performed on cells expressing the Rluc-reporters described in Fig. 5a. We observed that while KSRP associated with the Rluc-NPM-3′ mRNA and Rluc-NPM-3′-mut2, it failed to interact with the Rluc-NPM-3′-mut1 message (Figs. 7d–e and Supplementary Fig. 9). Therefore, together these results show that KSRP directly associates with the NPM mRNA through the E1 element that is also one of the sites that mediates HuR binding.

Figure 7. HuR and KSRP form a complex and bind to the same element in the NPM 3′UTR.

(a) IP coupled to RT-PCR (upper panel) or RT-qPCR (lower panel) experiments were performed to determine the association of KSRP and HuR with the NPM mRNA in C2C12 cells. For RT-qPCR, NPM mRNA levels are shown +/− S.E.M. of three independent experiments ***P<0.0001 (t test). (b) Supershift binding assay was performed to demonstrate that the radiolabelled NPM 3′UTR as well as the P1 cRNA probe, unlike the P2 probe, can associate to a complex containing KSRP (indicated by an asterisk (*)). (c) Gel-shift binding assay was performed with 500 ng of purified GST or His-KSRP proteins and the indicated radiolabeled cRNA probes. (d–e) IP experiments were performed on C2C12 cells expressing Rluc, Rluc-NPM-3′ and Rluc-NPM-3′-mut1 using the KSRP or IgG antibody. Immunoprecipitation of KSRP (d) and association with reporter RNAs (e) were determined as described in Figure 5b–c. (f) C2C12 extracts treated or not with RNase A were used for IP experiments with the anti-KSRP or -IgG antibodies. The binding of HuR to KSRP was then assessed by western blot. For unknown reasons, we observed a shift in the molecular weight of KSRP that we believe could be due to the immunoprecipitation of a posttranslationally modified KSRP isoform. (g) Agarose gel demonstrating effectiveness of RNAse treatment. (h) In vitro GST pull-down assay demonstrating that HuR directly interacts with KSRP. Input lanes account for 10% of the reaction performed in the assay. (i–j) IP coupled to RT-qPCR experiments were performed using anti-KSRP (i) or HuR (3A2) (j) antibodies on total extract (TE) from C2C12 cells treated with siHuR (i) or siKSRP (j). NPM mRNA levels in the immunoprecipitates were standardized (as described in the Methods) and normalized to the corresponding IgG and input sample. The NPM mRNA levels in siHuR or siKSRP conditions were plotted relative to siCtr conditions +/− S.E.M. of three independent experiments, *P<0.01, **P<0.001 (t test). All gels/blots shown in the figure are representative of three independent experiments (except for the gel shown in 7b which is representative of two). * shown on gel indicates the location of shifted complexes.

Next we investigated whether HuR and KSRP can form a complex. IP experiments on cell extracts treated or not with 100μg/ml RNAse A indicated that HuR and KSRP associate in C2C12 cells in an RNA-independent manner (Figs. 7f–g). However, this RNA independent interaction between HuR and KSRP was not seen using a lower dose of RNAseA (12.5μg/ml). Moreover, GST-pulldown experiments, using recombinant His-KSRP and GST-HuR, further confirmed this direct interaction (Fig. 7h). We then assessed whether the association between the NPM mRNA and HuR or KSRP requires an intact HuR/KSRP complex. IP/RT-qPCR experiments showed that depleting HuR from C2C12 cells significantly decreased (>40%) the amount of NPM mRNA that binds to KSRP (Fig. 7i). Similarly, although knocking down KSRP in C2C12 cells did not affect the binding of HuR to the myogenin and p21 mRNAs (Supplementary Fig. 10), it decreased its association with the NPM mRNA (Fig. 7j). Taken together, these data suggest that in muscle cells the HuR/KSRP complex assembles in an RNA-independent manner and is recruited to the P1-1 element thus promoting the rapid destabilization of the NPM mRNA.

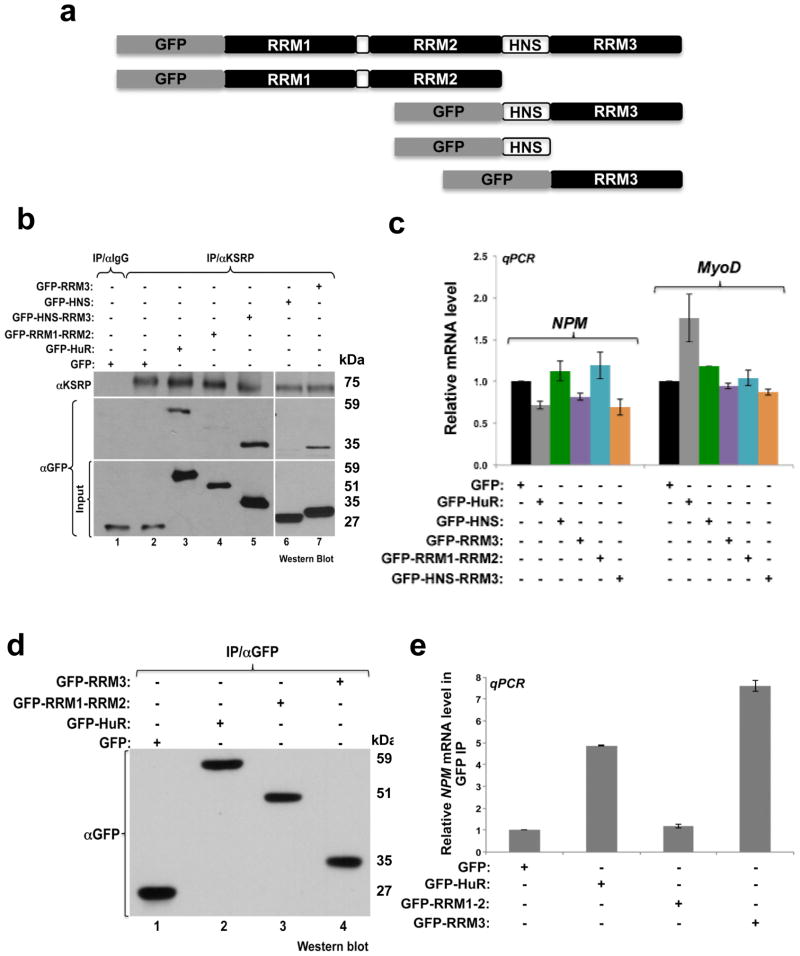

To gain insight into the mechanism by which HuR executes these functions, we first determined the HuR domain responsible for this activity. We generated plasmids expressing GFP-tagged wild-type HuR or various deletion mutants of HuR (Fig. 8a). Each one of these isoforms was then expressed in C2C12 cells that were subsequently used for IP experiments with the anti-KSRP antibody. Western blotting analysis with the anti-GFP antibody has shown that similarly to wt HuR, polypeptides harboring the RRM3 motif (GFP-HNS-RRM3 and GFP-RRM3), but not those harboring RRM1-2 or HNS alone, were able to associate with KSRP (Fig. 8b) and promote a significant decrease in NPM mRNA level (Fig. 8c). In addition, an IP/RT-qPCR experiment on cells expressing GFP-HuR, -RRM1-2 or -RRM3 indicated that while RRM1-2 did not show a strong association with the NPM mRNA, RRM3 associated with more NPM message than wt-HuR (Fig. 8d–e). Since, during myogenesis cytoplasmic HuR undergoes caspase-mediated cleavage generating HuR-CP1 (24 kDa, RRM1-RRM2-ΔHNS1) and HuR-CP2 (8 kDa, ΔHNS2-RRM3) 4 (Fig. 2c and Supplemental Fig. 12a), we next verified the effect of these CPs on NPM expression. Our data confirmed that HuR-CP2, which harbors the RRM3 motif, but not HuR-CP1, associated with KSRP and the NPM mRNA and was also able to form a complex with the HuR/KSRP binding element in the NPM 3′UTR (the P-1-1 probe) (Supplementary Figs.11b–g). In addition, similarly to GFP-RRM3 (Fig. 8c), we observed that the overexpression of HuR-CP2 promoted a significant decrease in NPM mRNA the steady-state levesl and that this effect is KSRP-mediated (Supplementary Figs.11h–i). Together, these results strongly indicate that the RRM3 motif of HuR plays a key role in mediating the formation of the HuR/KSRP in differentiating muscle cells.

Figure 8. The HuR RRM3 motif is required for the formation of KSRP/HuR complex.

(a) Schematic diagram depicting the primary structure of HuR protein shows the three RNA binding domains (RRM1-3) and the HuR Nucleocytoplasmic Shuttling domain (HNS). Also shown are the different HuR isoforms conjugated to the GFP tag. (b–e) Exponentially growing C2C12 muscle cells were transfected with GFP, GFP-HuR, GFP-RRM1-RRM2, GFP-HNS-RRM3, GFP-HNS or GFP-RRM3 plasmids. Total cell extracts (b and d) or total RNA (c and e) were prepared from these cells 24 hours posttransfection. (b) IP experiments on these cell extracts were performed using the KSRP antibody or IgG as a control. The input (10% of the total extract) and the immunoprecipitate were analyzed by western blot using antibodies against GFP. (c) RT-qPCR analysis on total RNA prepared from these cells was performed using specific primers for NPM, MyoD and GAPDH mRNAs. NPM and MyoD mRNA levels were standardized against GAPDH mRNA and plotted relative to the GFP control condition +/− the S.E.M. of three independent experiments. (d) IP experiments were performed using the GFP antibody on extracts from the C2C12 cells expressing GFP, GFP-HuR, GFP-RRM1-RRM2 or GFP-RRM3 and analyzed by western blot using the GFP antibody. (e) RNA was isolated from the IP described in (d) and RT-qPCR were performed using primers specific for NPM and RPL32 mRNAs. NPM mRNA levels were standardized against RPL32 mRNA levels. For each IP sample, NPM mRNA levels were normalized as described in Figure 5 and plotted relative to the GFP IP +/− S.E.M. of three independent experiments.

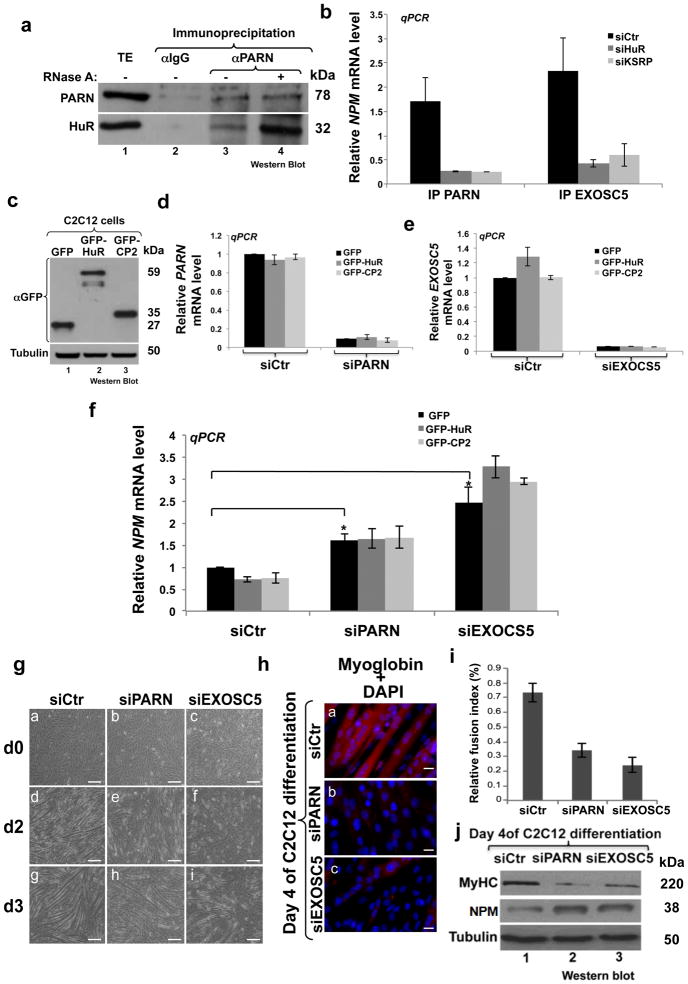

Since KSRP has been shown to promote mRNA decay by recruiting the ribonuclease PARN and components of the exosome such as EXOSC5 3,17 we investigated whether enzymes could play a role in the HuR/KSRP-mediated destabilization of NPM mRNA. Our IP experiments showed that HuR associates with both PARN and EXOSC5 in an RNA independent manner (Fig. 9a and Supplementary Fig. 12). Interestingly, although both PARN and EXOSC5 interact with the NPM mRNA in C2C12 cells, this association is lost in HuR or KSRP depleted cells (Fig. 9b). To assess whether PARN and/or EXOSC5 play a role in the HuR/KSRP-medited effect on NPM expression, we expressed GFP-HuR or GFP-HuR-CP2 in C2C12 cells depleted or not of these two ribonucleases (Fig. 9c) and the the expression level of the NPM mRNA was determined using RT-qPCR. Our data showed that while knocking down PARN (Fig. 9d) or EXOSC5 (Fig. 9e) in C2C12 cells increased the expression of the NPM mRNA, the absence of these ribonucleases prevented the HuR- or HuR-CP2-mediated NPM mRNA decay (Fig. 9f). The fact that the depletion of XRN1 (a 5′-3′ exoribonuclease component of the decapping complex) 27 did not have a major effect on NPM mRNA expression (Supplementary Fig. 13) suggests that only ribonucleases that are recruited by KSRP such as PARN and EXOSC5 take part in this destabilization activity. Interestingly, we also demonstrate that knocking down PARN and EXOSC5 totally prevented C2C12 cells from entering the differentiation process (Figs. 9g–i) and the depletion of NPM in these cells partially reestablished their myogenic potential (Supplementary Fig. 14). Of note, the weak rescue of myogenesis in cells depleted of both EXOSC5 and NPM suggests that EXOSC5 targets other messages in muscle cells. Together, our data indicate that during early myogenesis the formation of the HuR/KSRP complex leads to the recruitment of ribonucleases such as PARN and EXOSC5 which in turn destabilize the NPM mRNA thus promoting muscle fiber formation.

Figure 9. The HuR/KSRP-mediated decay activity requires PARN and EXOSC5 to destabilize NPM mRNA and promote muscle fiber formation.

(a) IP experiments using the anti-PARN antibody were performed on total cell extracts prepared from proliferating C2C12 cells treated or not with RNase A. The precipitates were used for Western blotting analysis with anti-PARN and –HuR antibodies. The blots shown are representative of two independent experiments. (b) IP coupled to RT-qPCR experiments were performed using the PARN or the EXOSC5 antibodies on total extract (TE) from C2C12 cells treated with siHuR or siKSRP. The NPM mRNA in the immunoprecipitate was standardized and normalized as described in Figs.7i,j. The PARN- or EXOSC5- associated NPM mRNA levels in siHuR or siKSRP treated C2C12 cells were plotted relative to siCtr conditions +/− S.E.M. of three independent experiments *P<0.01 (t test). (c–f) GFP, -HuR and -CP2 proteins were expressed in C2C12 cells treated or not with siRNA-PARN or -EXOSC5. 24h later protein extracts and total RNA were prepared. (c) Western blotting analysis was performed using antibodies against GFP and α-tubulin (loading control). (d–f) RT-qPCR analysis was performed using primers specific for GAPDH as well as PARN (d), EXOSC5 (e), NPM (f) mRNAs. The levels of PARN, EXOSC5 and NPM mRNAs were normalized against GAPDH mRNA level and were plotted relatively to the siRNA Ctr-treated and GFP-transfected cells +/− the S.E.M. of three independent experiments *P<0.01 (t test). (g–j) Confluent C2C12 depleted of PARN or EXOSC5 were induced for differentiation for up to 4 days. (g) Phase contrast pictures showing the differentiation status of these cells at day (d) d0 (panels a–c), d2 (panels d–f), and d3 (panels g–i). Bars, 50μm. (h) These cells, on day 4 of muscle cell differentiation, were also fixed and used for IF with anti-Myoglobin antibody and DAPI staining. Images of a single representative field were shown. Bars, 10μm. (i) The fusion index was determined as described in Methods. (j) Total extracts from these cells were prepared and used for western blotting analysis with antibodies against My-HC, NPM and α-tubulin (loading control).

Discussion

In this work we delineate the molecular mechanisms by which muscle cells down regulate NPM expression and show that this events represents a key regulatory step required for their commitment to myogenesis. Though previous studies have indicated that lowering the expression of NPM is required for the differentiation of a variety of cells such as HL60 and K562 19,20, the molecular mechanism and the players behind this reduction remained elusive. Here we show that the decrease in NPM expression involves the destabilization of its mRNA via a mechanism mediated by the RNA-binding protein HuR. This observation was unexpected since HuR has been previously shown to stabilize the NPM mRNA in intestinal cells undergoing stress 18. In undifferentiated muscle cells the depletion of endogenous HuR results in the stabilization of the NPM mRNA and its increased expression, while HuR overexpression elicits the opposite effects. This mRNA destabilization activity of HuR involves its association, via the HuR-RRM3 motif, with KSRP and the ribonucleases PARN and EXOSC5 17. Together, our data support a model whereby in response to a myogenic signal HuR forms a complex with KSRP, PARN and the exosome, which in turn is recruited to a U-rich element in the 3′UTR leading to the destabilization of the NPM mRNA and the promotion of the early steps of myogenesis.

Although a NPM overexpression was previously linked to the inhibition of the differentiation of human promyelocytic leukemia HL60 cells and megakaryocytic K562 cells 19,20, our work provides the first demonstration that NPM is implicated in muscle fiber formation. NPM is highly expressed in a variety of cell lines and tissues and has been involved in many cellular processes such as cell proliferation and stress response 28,29. In fact, manipulating the abundance of NPM has a dramatic effect on cell fate and on embryogenesis. Npm −/− mice do not complete their embryonic development and die between embryonic days E11.5 and E16.5 due to a severe anemia caused by a defect in primitive hematopoiesis 30. On the other hand, a high expression level of NPM is involved in cell transformation and tumour progression 29,31–33. NPM levels significantly decrease in response to a variety of stimuli, among them those known to trigger cell cycle arrest and cell differentiation 19,20,29. These data and the fact that NPM and HuR are both essential for the development of numerous cell lines and tissues 12,28,29,34–36, highlight the importance of delineating the mechanism(s) by which HuR down regulates NPM expression.

Previously, other and we have demonstrated that HuR plays a prominent role during muscle cell differntiation by increasing the stability of promyogenic mRNAs at the later stages of this process 5,7. Here we show that HuR is also involved in the early stages of myogenesis by degrading the NPM mRNA in a KSRP dependent manner. Since previous reports have indicated that during myogenesis HuR and KSRP affect the half-lives of the same promyogenic transcripts, but in opposite ways, their collaboration to degrade a common target mRNA in undifferentiated muscle cells was unexpected. Indeed, it has been shown that KSRP plays a key role in maintaining low levels of p21 and Myogenin mRNAs in undifferentiated muscle cells by promoting their rapid decay 3. The fact that HuR does not associate with these mRNAs in these cells 5 could explain why these transcripts became available to KSRP and the KSRP-associated decay machinery. However, during the step where muscle cells fuse to form myotubes, p38MAPK phosphorylates KSRP leading to the release of p21 and Myogenin mRNAs from this decay machinery 3. These findings, together with the data outlined in this manuscript, confirm the importance of HuR during muscle fiber formation and indicate that the functional consequences and the binding specificity of HuR to its target mRNA could change from one myogenic step to another depending on the nature of its protein ligand.

It is not surprising that HuR exerts different/opposite functions on its target transcripts. Numerous reports have indicated that depending on extra- or intracellular signals and/or the trans- or the cis-binding partners, HuR either activates or represses the turnover or translation of its mRNA targets10,16,37,38. Indeed, the Steitz laboratory has shown that HuR mediates the decay of the viral small nuclear RNA (snRNA) Herpesvirus saimiri U RNA 1 (HSUR 1) in an ARE-dependent manner 39,40. Recently, HuR has been associated with the destabilization of the p16 mRNA both in HeLa and in IDH4 cells 38. HuR participates in the decay of this message by forming a complex with AUF1 and Argonaute, two well-known mRNA decay factors 38,41–43. Our data uncover a novel mechanism by which HuR mediate the decay of its mRNA target leading to muscle fiber formation. This mRNA decay-promoting activity of HuR depends on its association with KSRP, a factor known to promote the decay of AU-rich containing mRNAs 17,44. Interestingly, besides a difference in the way they form, the HuR/AUF1 and HuR/KSRP complexes also show a difference in their functional outcome. While in muscle cells HuR/KSRP assemble in a RNA-independent manner prior to their recruitment to the same U-rich element in the NPM 3′UTR, the formation of the HuR/AUF1 complex in HeLa cells is RNA-dependent and occurs via the binding of each one of these two proteins with a different element in the p16 3′UTR 38. Likewise, unlike the HuR/AUF1 complex that promotes the proliferation of HeLa and IDH4 cells 38, the HuR/KSRP complex triggers the differentiation of muscle cells, an event linked to a cell cycle withdrawal 21.

Besides the association with different protein ligands, we still do not know whether other processes such as posttranslational modifications are also involved in the functional switch of HuR during myogenesis. It has been shown that phosphorylation on various serine residues could impact the association of HuR with some of its target mRNAs such as p21 45–47. While the implication of phosphorylation in HuR-mediated effects in muscle cells is still elusive, we recently showed that caspase-mediated cleavage modulates plays a key role in modulating the promyogenic function of 4,8. Although our data indicated that HuR-CP1 promotes the cytoplasmic accumulation of HuR during the myoblast-to-myotube fusion 4, the function of HuR-CP2 remained unclear. Here, we demonstrate that HuR-CP2 associates with KSRP and is sufficient to downregulate the expression of NPM mRNA in muscle cells (Supplementary Fig. 11). Interestingly we also show that, unlike the non-cleavable isoform of HuR (HuRD226A), HuR-CP2 can reestablish the myogenic potential of C2C12 cells depleted of endogenous HuR (Figs. 2i–l). While additional experiments are needed to confirm the role of this cleavage product in the promyogenic function of HuR, these observations raise the possibility of its implication in maintaining a low expression of levels of NPM during myogenesis. While these and likely other modifications modulate HuR function in muscle cells, the data described above establish that HuR, through its ability to promote the decay of target mRNAs, acquires more flexibility to use different ways to impact important processes such as muscle fiber formation. Therefore, since a change in HuR function and associated partners has been linked to chronic and deadly diseases such as cancer and muscle wasting 48–50, delineating the molecular mechanisms behind the HuR-mediated mRNA decay activity could identify novel targets that help design effective strategies to treat these patients.

Methods

Plasmid construction

The pYX-Asc plasmid containing the full-length mouse NPM cDNA (Accession Number: BC054755) was purchased from Open Biosystems (Catalogue Number: MMM1013-9497870). To generate the GFP-NPM plasmid, full-length mouse NPM was amplified by PCR using the pYX-Asc plasmid as template and the following primers: forward 5′GGC AAG CTT CGT CTG TTC TGT GGA ACA GGA-3′ and reverse 5′-CGG GATC CGG GAA AGT TCT CAC TTT GCA TT-3′. The pAcGFP1-C1 (Clontech) and the PCR products were digested by HindIII and BamHI restriction enzymes (NE Biolabs). To generate the pRL-SV40-NPM plasmid, the full-length 3′UTR of mouse NPM was amplified by PCR using the pYX-Asc plasmid as template and the following primers: forward 5′-GCT CTA GAG AAA AGG GTT TAA ACA GTT TGA-3′ and reverse 5′-CCG GCG GCC GCA CTT TAT TAA AAT ACT GAG TTT ATT-3′. The pRL-SV40 vector (Promega) and the PCR products were digested by XbaI and NotI restriction enzymes (NE Biolabs). PCR inserts were ligated into the plasmids using the T4 DNA ligase (NE Biolabs) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. pRL-SV40-NPMmut1 and mut2 plasmid was generated by Norclone Biotech Laboratories, Kingston, ON, Canada (as described in text). The GFP and GFP-HuR plasmids were generated and used as described in 51.

Cell culture and transfection

C2C12 muscle cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were grown in media containing 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen) in DMEM (Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium from Invitrogen). In order to induce muscle cell differentiation, cells were switched to a media containing DMEM, 2% horse serum, penicillin/streptomycin antibiotics (Invitrogen), and 50mM HEPES, pH 7.4 (Invitrogen) when their confluency reached 100%5,6.

For the generation of stable cell lines, C2C12 cells were transfected with GFP, GFP-HuR and GFP-NPM plasmids, and 24 hours posttransfection G418 (1 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the media. The stable cell lines were selected with G418 for 2 weeks and then sorted by flow cytometry (FACS) to select clones with equal expression levels. Transfections with siRNAs specific for HuR were performed using jetPEI (Polyplus Transfection) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For DNA plasmid transfections, C2C12 cells at 70% confluency were transfected in 6-well plates with 1.5 μg of plasmid DNA using Lipofectamine and Plus reagents (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were subsequently incubated at 37°C for 24 hours before harvesting and analysis.

siRNA

siRNA oligonucleotides against HuR (5′-AAG CCU GUU CAG CAG CAU UGG-3′ 5), NPM (5′-CAU CAA CAC CGA GAU CAA A dT dT -3′) (Dharmacon, USA), KSRP (5′-GGA CAG UUU CAC GAC AAC G dT dT-3′ 3), and the siRNA Ctr (5′-AAG CCA AUU CAU CAG CAA UGG-3′) 5, were synthesized by Dharmacon, USA. siRNA PARN (5′-GGA UGU CAU GCA UAC GAU Utt- 3′ ), EXOSC5 (5′-UCU UCA AGG UGA UAC CUC Utt- 3′) and XRN1 (5′-GAG GUG UUG UUU CGA AUU Att- 3′) were acquired from Ambion USA.

Preparation of cell extracts and immunoblotting

Total cell extracts were prepared 52 and western blotting was performed using antibodies against HuR (3A2, 1:10,000) 53, NPM (anti-B23 clone FC82291, Sigma-Aldrich,1:30000), My-HC (Developmental studies Hybridoma5,1:1000), Myoglobin (DAKO,1:500), α–tubulin (Developmental studies Hybridoma Bank, 1:1000), GFP (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA, 1:1000), and KSRP (affinity-purified rabbit serum 17, 1:3000), anti-myogenin (F5D, obtained from Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, 1:250) and caspase 3 cleavage product (Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1000).

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence5 was performed to detect GFP expression as well as to visualize myotubes using antibodies against My-HC (1;1000) and Myoglobin (1:500). Staining with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was employed to visualize nuclei.

Fusion Index

The fusion index5 indicating the efficiency of C2C12 differentiation was determined by calculating the number of nuclei in each microscopic field in relation to the number of nuclei in myotubes in the same field

Northern blot analysis and actinomycin D pulse-chase experiments

The extraction of total RNA from C2C12 cells was performed using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Northern blot analysis23 was performed using probes specific for MyoD, HuR, 18S 48, and NPM (Supplementary Table 2). These probe RNAs were generated using the PCR Purification Kit (GE Healthcare) and radiolabeled with α32P dCTP using Ready-to-Go DNA labelling beads (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The stability of NPM mRNA was assessed by the addition of the transcriptional inhibitor actinomycin D (5 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich)48 for the indicated periods of time.

RT-qPCR

1μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed using the M-MuLV RT system. A 1/80 dilution of cDNA was used to detect the mRNAs using SsoFast™ EvaGreen® Supermix (Bio-Rad). Expression of NPM, MyoD, p21, myogenin and RLuc was standardized using GAPDH as a reference (see primers in supplemental Materials and Methods), and relative levels of expression were quantified by calculating 2−ΔΔCT, where ΔΔCT is the difference in CT (cycle number at which the amount of amplified target reaches a fixed threshold) between target and reference.

Genomic DNA extracts and analysis with RT-qPCR

Cell pellets are resuspended in the digestion buffer (100 mM NaCl; 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8; 25 mM EDTA, pH 8; 0.5% SDS; 0.1 mg/ml proteinase K) and incubated at 50°C overnight. gDNA is extracted with phenol chloroform (invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RT-qPCR experiment was performed as described above starting from 16 pg of extracted gDNA.

Immunoprecipitation

Cell extracts were prepared in the lysis buffer (50mM Tris, pH 8; 0.5% Triton X-100; 150mM NaCl; complete protease inhibitor (Roche)). When indicated, cell extracts were digested for 30 min at 37°C with RNase A (100 μg/ml). Two μl of the anti-KSRP serum (affinity purified rabbit serum 17) was incubated with 50μl of proteinA-Sepharose slurry beads (washed and equilibrated in cell lysis buffer) for 1h at 4°C. Beads were washed three times with cell lysis buffer and incubate with 300μg of cell extracts overnight at 4°C. Beads were washed three times with cell lysis buffer and co-immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed by western blotting. HuR, PARN and EXOSC5 immunoprecipitation were performed3,5,54 using antibodies against HuR (3A2), PARN (Cell Signaling, USA), EXOSC5 (Abcam, USA) and IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, USA).

Preparation of mRNA (mRNP) complexes and analysis with RT-PCR

Purified RNA from mRNP complexes5,54 was resuspended in 10 μl of water and 4 μl was reverse transcribed using the M-MuLV RT system (NE Biolabs) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Subsequently, 2 μl of cDNA was amplified by PCR or qPCR using NPM specific primers (Supplementary Table 2). When analysed by qPCR, a 1/20 dilution of cDNA was used to detect the mRNAs using SybrGreen (SsoFast™ EvaGreen® Supermix). The mRNA levels associated with these mRNP complexes were then standardized against RPL32 mRNA levels (used as a reference) and compared to mRNA levels in the IgG control. In experiments transfected with Rluc reporter constructs, the Rluc mRNA associated with immunoprecipiated HuR was determined by RT-qPCR, standardized against RPL32 mRNA levels and then the steady-state levels for each treatment. These standardized Rluc mRNA levels were then compared to Rluc mRNA levels in the IgG IP.

cDNA array analysis

Microarray experiments were performed using mouse array, which contain probe sets of characterized and unknown mouse ESTs from 17,000 genes 55. RNAs from siHuR- and siCtr-treated C2C12 cells extracts were prepared 56, processed and hybridized on the cDNA arrays. The data were processed using the Array Pro software (Media Cybernetics, Inc.), then normalized by Z-score transformation55 and used to calculate differences in signal intensities. Significant values were tested using a two-tailed Z-test and a P of ≤0.01. The data were calculated from two independent experiments.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

The fluorescence in situ hybridization experiments were performed57 using a DNA fragment of ~500 bp corresponding to the coding region of mouse NPM. The fragment was amplified by PCR using the following primers fused to either a T7 or T3 minimal promoter sequence: NPM forward, 5′-TAA TAC GAC TCA CTA TAG GGA CGG TTG AAG TGT GGT TCA G -3′, and NPM reverse, 5′-AAT TAA CCC TCA CTA AAG GAA CTT GGC TTC CAC TTT GG -3′. The PCR product was used as the template for in vitro transcription of the NPM probe needed for fluorescence in situ hybridization. The antisense (T3) and sense (T7) probes were prepared using digoxigenin-RNA labeling mix (Roche Diagnostics). The RNA probes were quantified, denatured, and incubated with permeabilized cells57. After the hybridization, the cells were used for immunofluorescence to detect HuR57.

Polysome fractionation

4×107 myoblasts were grown and treated with siRNAs as described above. Briefly, the cytoplasmic extracts obtained from lysed myoblast cells were centrifuged at 130,000 × g for 2 h on a sucrose gradient (10–50% w/v)58. RNA was extracted using Trizol LS (Invitrogen), and was then analyzed on an agarose gel. The levels of NPM and GAPDH mRNAs were determined using RT-qPCR.

RNA electrophoretic mobility shift assays

The NPM cRNA probes were produced by in vitro transcription59. The accession number in the NCBI database of the NPM mRNA sequence used to generate these probes is NM_008722. The NPM probes 5′UTR, 3′UTR, P1, and P2 were generated by PCR amplification using a forward primer fused to the T7 promoter (Supplementary Table 2) as well as pYX-Asc-NPM expression vector as the template. For smaller probes (P1-1 to P2-3, P1-1-mut1, P1-1-mut2, P1-1-mut1-2), oligonucleotide sense and anti-sense (see supplemental Materials and Methods) were directly annealed and used for in vitro transcription. The RNA binding assays23 were performed using 500 ng purified recombinant protein (GST or GST-HuR) incubated with 50 000 cpm of 32P-labelled cRNAs. Supershift experiments were also performed with 10 μg total C2C12 cell extract (TE) incubated with 50 000 cpm of 32P-labelled cRNAs. An anti-KSRP antibody was then added to the reaction to supershift the RNP/cRNA complex containing KSRP.

Luciferase activity

The activity of Renilla luciferase was measured using a Renilla luciferase assay system (Promega) with a luminometer following the manufacturer’s instructions.

In vitro pull-down experiments

GST pull-down assay4 were performed using GST-HuR and recombinant His-KSRP. The interaction of the His-KSRP with the pulled-down GST-HuR was analyzed by western blotting using the GST and KSRP antibodies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. C. von Roretz for critical review of this manuscript and insightful discussion. We are grateful to Veronique Sauve and Dr. Kalle Gehring for their help with the BIACORE experiments. AC is a recipient of the Canderal scholarship for PDFs (2010–2011) as well as the Peter Quinlan Fellowship in Oncolgy (2011–2012). VDR is a Research Fellow of the Terry Fox foundation through an award from the Canadian Cancer Society (former National Cancer Institute of Canada). This work was supported by a CIHR (MOP-89798) operating grant to I.G. MG is supported by the NIA-IRP, NIH. R.G. is supported by grants from AIRC (IG 2010-2012) and AICR (#10-0527) to R.G. IG is a recipient of a TierII Canada Research Chair.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

A.C. designed, carried out, analysed and interpreted all of the experiments in the manuscript. B.S., V.D., X.J.L., K.V. and J.M. assisted with some of the immuno/northern blots as well as RT-qPCR experiments described in the manuscript. I.L. and M.G. designed and carried out the microarray experiments described in Supplementary Table 1. M.G. and R.G. helped with the immunoprecipitation experiment described in Fig. 7F. R.G. also helped with the design of experiments described in Figs. 6 and 7 and, provided reagents. C.W., J.R. and S.M. provided technical expertise and helped in the design of some of the experiments. S.D. helped in the design of several experiments in the manuscript. S.D. also participated in the writing and editing the manuscript. I.E.G. conceived and helped design all experiments in the manuscript, aided in the analysis of the data and wrote the manuscript.

Competing Financial Interests

We declare that the authors have no competing interests as defined by Nature Publishing Group, or other interests that might be perceived to influence the results and/or discussion reported in this article.

Accession Codes

Microarray data has been deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE57113.

References

- 1.Tallquist MD, Weismann KE, Hellstrom M, Soriano P. Early myotome specification regulates PDGFA expression and axial skeleton development. Development. 2000;127:5059–5070. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.23.5059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jun JI, Lau LF. The matricellular protein CCN1 induces fibroblast senescence and restricts fibrosis in cutaneous wound healing. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:676–685. doi: 10.1038/ncb2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Briata P, et al. p38-Dependent Phosphorylation of the mRNA Decay-Promoting Factor KSRP Controls the Stability of Select Myogenic Transcripts. Mol cell. 2005;20:891–903. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beauchamp P, et al. The cleavage of HuR interferes with its transportin-2-mediated nuclear import and promotes muscle fiber formation. Cell death and differentiation. 2010 doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Giessen K, Di-Marco S, Clair E, Gallouzi IE. RNAi-mediated HuR depletion leads to the inhibition of muscle cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:47119–47128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308889200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Giessen K, Gallouzi IE. Involvement of transportin 2-mediated HuR import in muscle cell differentiation. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:2619–2629. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-02-0167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Figueroa A, et al. Role of HuR in skeletal myogenesis through coordinate regulation of muscle differentiation genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:4991–5004. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.14.4991-5004.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.von Roretz C, Beauchamp P, Di Marco S, Gallouzi IE. HuR and myogenesis: being in the right place at the right time. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2011;1813:1663–1667. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.von Roretz C, Gallouzi IE. Decoding ARE-mediated decay: is microRNA part of the equation? J Cell Biol. 2008;181:189–194. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdelmohsen K, Kuwano Y, Kim HH, Gorospe M. Posttranscriptional gene regulation by RNA-binding proteins during oxidative stress: implications for cellular senescence. Biol Chem. 2008;389:243–255. doi: 10.1515/BC.2008.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lopez de Silanes I, Zhan M, Lal A, Yang X, Gorospe M. Identification of a target RNA motif for RNA-binding protein HuR. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:2987–2992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306453101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brennan CM, Steitz JA. HuR and mRNA stability. CMLS. 2001;58:266–277. doi: 10.1007/PL00000854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallouzi IE, Brennan CM, Steitz JA. Protein ligands mediate the CRM1-dependent export of HuR in response to heat shock. RNA. 2001;7:1348–1361. doi: 10.1017/s1355838201016089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gallouzi IE, Steitz JA. Delineation of mRNA export pathways by the use of cell-permeable peptides. Science. 2001;294:1895–1901. doi: 10.1126/science.1064693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdelmohsen K, Srikantan S, Kuwano Y, Gorospe M. miR-519 reduces cell proliferation by lowering RNA-binding protein HuR levels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:20297–20302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809376106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim HH, et al. HuR recruits let-7/RISC to repress c-Myc expression. Genes & development. 2009 doi: 10.1101/gad.1812509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gherzi R, et al. A KH domain RNA binding protein, KSRP, promotes ARE-directed mRNA turnover by recruiting the degradation machinery. Mol cell. 2004;14:571–583. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zou T, et al. Polyamine depletion increases cytoplasmic levels of RNA-binding protein HuR leading to stabilization of nucleophosmin and p53 mRNAs. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:19387–19394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602344200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsu CY, Yung BY. Over-expression of nucleophosmin/B23 decreases the susceptibility of human leukemia HL-60 cells to retinoic acid-induced differentiation and apoptosis. Int J Cancer. 2000;88:392–400. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20001101)88:3<392::aid-ijc11>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsu CY, Yung BY. Involvement of nucleophosmin/B23 in TPA-induced megakaryocytic differentiation of K562 cells. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1320–1326. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charge SB, Rudnicki MA. Cellular and molecular regulation of muscle regeneration. Physiological reviews. 2004;84:209–238. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00019.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia-Martinez J, Aranda A, Perez-Ortin JE. Genomic run-on evaluates transcription rates for all yeast genes and identifies gene regulatory mechanisms. Molecular cell. 2004;15:303–313. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dormoy-Raclet V, et al. The RNA-binding protein HuR promotes cell migration and cell invasion by stabilizing the beta-actin mRNA in a U-rich-element-dependent manner. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:5365–5380. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00113-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barreau C, Paillard L, Osborne HB. AU-rich elements and associated factors: are there unifying principles? Nucleic acids research. 2005;33:7138–7150. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanduja S, Kaza V, Dixon DA. Aging. 2009;1:803–817. doi: 10.18632/aging.100086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drury GL, Di Marco S, Dormoy-Raclet V, Desbarats J, Gallouzi IE. FasL expression in activated T lymphocytes involves HuR-mediated stabilization. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:31130–31138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.137919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Long RM, McNally MT. mRNA decay: x (XRN1) marks the spot. Mol cell. 2003;11:1126–1128. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00198-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frehlick LJ, Eirin-Lopez JM, Ausio J. New insights into the nucleophosmin/nucleoplasmin family of nuclear chaperones. Bioessays. 2007;29:49–59. doi: 10.1002/bies.20512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grisendi S, Mecucci C, Falini B, Pandolfi PP. Nucleophosmin and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:493–505. doi: 10.1038/nrc1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grisendi S, et al. Role of nucleophosmin in embryonic development and tumorigenesis. Nature. 2005;437:147–153. doi: 10.1038/nature03915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gubin AN, Njoroge JM, Bouffard GG, Miller JL. Gene expression in proliferating human erythroid cells. Genomics. 1999;59:168–177. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feuerstein N, Randazzo PA. In vivo and in vitro phosphorylation studies of numatrin, a cell cycle regulated nuclear protein, in insulin-stimulated NIH 3T3 HIR cells. Experimental cell research. 1991;194:289–296. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(91)90367-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dergunova NN, et al. A major nucleolar protein B23 as a marker of proliferation activity of human peripheral lymphocytes. Immunol Lett. 2002;83:67–72. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(02)00085-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katsanou V, et al. The RNA-binding protein Elavl1/HuR is essential for placental branching morphogenesis and embryonic development. Mol Cell Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1128/MCB.01393-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katsanou V, et al. HuR as a negative posttranscriptional modulator in inflammation. Mol Cell. 2005;19:777–789. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Papadaki O, et al. Control of thymic T cell maturation, deletion and egress by the RNA-binding protein HuR. J Immunol. 2009;182:6779–6788. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhattacharyya SN, Habermacher R, Martine U, Closs EI, Filipowicz W. Relief of microRNA-mediated translational repression in human cells subjected to stress. Cell. 2006;125:1111–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang N, et al. HuR uses AUF1 as a cofactor to promote p16INK4 mRNA decay. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:3875–3886. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00169-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fan XC, Myer VE, Steitz JA. AU-rich elements target small nuclear RNAs as well as mRNAs for rapid degradation. Genes & development. 1997;11:2557–2568. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.19.2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Myer VE, Fan XC, Steitz JA. Identification of HuR as a protein implicated in AUUUA-mediated mRNA decay. EMBO J. 1997;16:2130–2139. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.8.2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DeMaria CT, Brewer G. AUF1 binding affinity to A+U-rich elements correlates with rapid mRNA degradation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12179–12184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.21.12179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomas M, Lieberman J, Lal A. Desperately seeking microRNA targets. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2011;17:1169–1174. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parker R, Sheth U. P bodies and the control of mRNA translation and degradation. Mol cell. 2007;25:635–646. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gherzi R, et al. The RNA-binding protein KSRP promotes decay of beta-catenin mRNA and is inactivated by PI3K-AKT signaling. PLoS Biol. 2006;5:e5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 45.Masuda K, et al. Global dissociation of HuR-mRNA complexes promotes cell survival after ionizing radiation. EMBO J. 2011;30:1040–1053. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abdelmohsen K, Lal A, Kim HH, Gorospe M. Posttranscriptional orchestration of an anti-apoptotic program by HuR. Cell cycle. 2007;6:1288–1292. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.11.4299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lafarga V, et al. p38 Mitogen-activated protein kinase- and HuR-dependent stabilization of p21(Cip1) mRNA mediates the G(1)/S checkpoint. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:4341–4351. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00210-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Di Marco S, et al. NF-(kappa)B-mediated MyoD decay during muscle wasting requires nitric oxide synthase mRNA stabilization, HuR protein, and nitric oxide release. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6533–6545. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.15.6533-6545.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lopez de Silanes I, et al. Global analysis of HuR-regulated gene expression in colon cancer systems of reducing complexity. Gene Expr. 2004;12:49–59. doi: 10.3727/000000004783992215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lopez de Silanes I, Lal A, Gorospe M. HuR: post-transcriptional paths to malignancy. RNA Biol. 2005;2:11–13. doi: 10.4161/rna.2.1.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mazroui R, et al. Caspase-mediated cleavage of HuR in the cytoplasm contributes to pp32/PHAP-I regulation of apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:113–127. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200709030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.von Roretz C, Gallouzi IE. Protein kinase RNA/FADD/caspase-8 pathway mediates the proapoptotic activity of the RNA-binding protein human antigen R (HuR) J Biol Chem. 2010;285:16806–16813. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.087320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gallouzi IE, et al. HuR binding to cytoplasmic mRNA is perturbed by heat shock. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:3073–3078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tenenbaum SA, Lager PJ, Carson CC, Keene JD. Ribonomics: identifying mRNA subsets in mRNP complexes using antibodies to RNA-binding proteins and genomic arrays. Methods. 2002;26:191–198. doi: 10.1016/S1046-2023(02)00022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cheadle C, Vawter MP, Freed WJ, Becker KG. Analysis of microarray data using Z score transformation. J Mol Diagn. 2003;5:73–81. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60455-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lopez de Silanes I, et al. Identification and functional outcome of mRNAs associated with RNA-binding protein TIA-1. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:9520–9531. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9520-9531.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lian XJ, Gallouzi IE. Oxidative Stress Increases the Number of Stress Granules in Senescent Cells and Triggers a Rapid Decrease in p21waf1/cip1 Translation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:8877–8887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806372200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cammas A, et al. Cytoplasmic relocalization of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 controls translation initiation of specific mRNAs. Molecular biology of the cell. 2007;18:5048–5059. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-06-0603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gallouzi IE, et al. A novel phosphorylation-dependent RNase activity of GAP-SH3 binding protein: a potential link between signal transduction and RNA stability. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3956–3965. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.3956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.