Abstract

Sarcopenia and osteoporosis are important public health problems that occur concurrently. A bivariate genome-wide association study (GWAS) identified METTL21c as a suggestive pleiotropic gene for both bone and muscle. METTL21 family of proteins methylates chaperones involved in the etiology of both Inclusion Body Myositis with Paget's disease. To validate these GWAS results, Mettl21c mRNA expression was reduced with siRNA in a mouse myogenic C2C12 cell line and the mouse osteocyte-like cell line MLO-Y4. At day 3, as C2C12 myoblasts start to differentiate into myotubes, a significant reduction in the number of myocytes aligning/organizing for fusion was observed in the siRNA-treated cells. At day 5, both fewer and smaller myotubes were observed in the siRNA-treated cells as confirmed by histomorphometric analyses and immunostaining with Myosin Heavy Chain (MHC) antibody, which only stains myocytes/myotubes but not myoblasts. Intracellular calcium (Ca2+) measurements of the siRNA-treated myotubes showed a decrease in maximal amplitude peak response to caffeine suggesting that less Ca2+ is available for release due to the partial silencing of Mettl21c, correlating with impaired myogenesis. In siRNA-treated MLO-Y4 cells, 48 hours after treatment with dexamethasone, there was a significant increase in cell death, suggesting a role of Mettl21c in osteocyte survival. To investigate the molecular signaling machinery induced by the partial silencing of Mettl21c, we monitored with a real-time PCR gene array the activity of 10 signaling pathways. We discovered that Mettl21c knockdown modulated only the NFκB signaling pathway (i.e., Birc3, Ccl5 and Tnf). These results suggest that Mettl21c might exert its bone-muscle pleiotropic function via the regulation of the NFκB signaling pathway, which is critical for bone and muscle homeostasis. These studies also provide rationale for cellular and molecular validation of GWAS, and warrant additional in vitro and in vivo studies to advance our understanding of role of METTL21C in musculoskeletal biology.

Keywords: Genetic Research, Human Association Studies, Osteocytes, Skeletal Muscle, Bone-Muscle Interactions

Introduction

As the average lifespan in developed countries continues to increase due to significant advancements in medicine, the incidence and cost of treating age-related diseases, particularly muscle and bone diseases, has dramatically escalated. Sarcopenia, an age-related loss of muscle mass that leads to functional impairment, and osteoporosis, a disease manifested by reduced bone density, increased bone porosity, and higher risk of fractures, normally present as concurrent disorders of the musculoskeletal system during aging, and pose significant public health concerns (1) . Every year, the cost alone in the United States of treating osteoporosis is 14 billion dollars, and sarcopenia, which affects every individual over the age of 50 resulting in the loss of 1% to 2% of muscle mass each year (2, 3), has been estimated to generate 18 to 30 billion dollars of direct costs per year (4).

It is becoming ever more evident that bones and muscles are endocrine organs because they produce and secrete “hormone-like factors” that can mutually influence each other and other tissues (5-9). Recently, evidence has emerged that secreted factors from muscle cells can have profound influence on osteocytes in culture, and vice versa (6, 9-11), suggesting that muscle and bone communicate at a molecular level via biochemical factors that are reciprocally important for optimal function. However, these molecular factors remain largely unknown.

With the discovery of genes with biological effects on both muscle and bone traits it becomes necessary to understand potential mechanisms underlying musculoskeletal diseases. To identify genes with pleiotropic effects on bone and muscle traits, we performed a bivariate genome-wide association study (GWAS) using results from univariate meta-analyses of dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA)-derived bone and muscle traits, obtained by large consortia (12-14). One suggestive locus (with bivariate p = 2.3 ×10−7 for rs895999) from this bivariate GWAS study was identified as LOC196541, a.k.a. methyltransferase like 21C (METTL21C). METTL21C, located on 13q33.1, belongs to the METTL2 family of the methyltransferase superfamily and has protein-lysine N-methyltransferase activity (15). METTL21C appears to be highly expressed in muscle (see METTL21C expression in normal human tissues at http://www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=METTL21C) and important for meat quality traits in cattle (16). Of greater interest, a recent report revealed that the METTL21 family of proteins methylates valosin containing protein (VCP) chaperones, which themselves can harbor specific mutations that are causal to both Inclusion Body Myositis with Paget's Disease of bone (17). In the present study, siRNA knockdown in muscle and osteocyte cells, respectively, was used to validate in vitro the functional importance of Mettl21c for muscle differentiation and function and bone cell viability.

Materials and methods

Materials

Materials included αMEM media, DMEM high glucose media, penicillin-streptomycin (P/S) 10,000U/mL each and trypsin-EDTA 1× solution from Mediatech Inc. (Manassas, VA, USA); calf serum (CS), fetal bovine serum (FBS), horse serum (HS) and caffeine from Thermo Fischer Scientific Inc. (Waltham, MA, USA); Oligofectamine and OptiMEM from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA); Mettl21c siRNA (Antisense stand: 5’-UAUUGUAUUGAAGAUUUCCTA-3’) and All Star negative control siRNA from Qiagen (Valencia, CA, USA); bovine serum albumin, diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and dexamethasone from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA); trypan blue 0.4% solution from MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH, USA); rat tail collagen type I from BD Biosciences (Bedfort, MA, USA); 16% paraformaldehyde from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA, USA); GenMute siRNA transfection Reagent for C2C12 Cell from SignaGen Laboratories (Rockville, MD, USA); Tri reagent from Molecular Research Center, Inc. (Cincinnati, OH, USA); High capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA, USA); Mouse Signal Transduction PathwayFinder PCR Array; RT2 First Strand Kit and RT2 Real-TimeTM SYBR green/Rox PCR master mix from SABiosciences (Valencia, CA, USA); RNeasy Mini Kit from Qiagen (Valencia, CA, USA); anti-human myosin Heavy Chain Carboxyfluorescein (CFS)-conjugated mouse monoclonal anti-human Myosin Heavy Chain antibody from R&D Systems Inc. (Minneapolis, MN, USA); Fura-2/AM from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY, USA). C2C12 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA, USA).

Methods

Bivariate GWAS of bone and muscle phenotypes

We have already reported a bivariate GWAS analysis for pairs of bone geometry and muscle phenotypes using data from two consortia of human population-based studies (18). Hip geometry measures were derived from dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans using the Hip Structural Analysis program in 17,528 adult men and women from 10 cohorts in the Genetic Factors for Osteoporosis (GEFOS) consortium. Appendicular lean mass (aLM), combining upper and lower extremities, was obtained from participants of the Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology (CHARGE) consortium (22,360 adult men and women from 15 cohorts). GWAS was performed using a state-of-the-art methodology (19). First, study-specific analyses of ~2,500,000 genome-wide polymorphic markers (imputed based on CEU HapMap phase II panel) were performed for hip geometry and aLM, separately. An additive genetic effect model was applied with adjustment for age, sex, height, fat mass and ancestral genetic background. Second, meta-analyses of the individual genome-wide association studies were performed for hip geometry and aLM, separately, using a fixed-effects approach. Before performing meta-analysis, poorly imputed and less common polymorphisms (minor allele frequency < 1%) were excluded for each study. Markers present in less than three studies were removed from the meta-analysis yielding ~ 2.2 million polymorphisms. We then performed a bivariate analysis for bone geometry and aLM together by combining the univariate GWAS results, using our modification of O'Brien's combination of test statistics. We considered polymorphisms as potentially pleiotropic if their bivariate p-value of association was an order of magnitude more significant than both univariate p-values.

Cell cultures

For this study, C2C12 myoblasts were cultured following our own previously published protocols (9, 11). Briefly, cells were grown at 37°C in a controlled humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere in growth medium (GM), DMEM/high glucose +10% FBS (100U/mL P/S), and maintained at 40-70% cell density. Under these conditions, myoblasts proliferate, but do not differentiate into myotubes. During propagation, medium was changed every 48 h. To induce differentiation of myoblasts into myotubes, when cells reached 75% confluence, GM was replaced with differentiation medium (DM: DMEM/high glucose + 2% horse serum, 100U/mL P/S). Fully differentiated, functional, contracting myotubes were formed within 5-7 days.

MLO-Y4 cells, a murine long bone-derived osteocytic cell line, were cultured as previously described (20). Briefly, cells were seeded onto type I collagen-coated plates and cultured in αMEM + 2.5% FBS + 2.5% CS (100U/mL P/S). Cells were maintained at ~60% confluence throughout the culture period.

siRNA treatment of C2C12 myoblast cells and MLO-Y4 cells

C2C12 cells were plated in 6-well plates, 7.5×104/well, and allowed to attach and grow overnight. Cells were transfected following the manufacturer's instructions. C2C12 cells were treated with 40nM Mettl21c siRNA+ 4μl GenMute siRNA transfection Reagent (Mettl21csiRNA-treated cells), while negative control cells were treated with 40nM All Star negative control siRNA + 4μl GenMute siRNA Transfection Reagent for C2C12 Cell. This negative control has a scrambled sequence and is also tagged with a fluorescent probe, allowing monitoring of transfection efficiency. We further employed a vehicle control by treating the cells with transfection reagent for C2C12 cells without siRNA. After 24h of transfection, cells were cultured in DM and allowed to differentiate for 7 days.

MLO-Y4 cells were plated in 6 well plates, 6.5×103 cells/cm2, allowed to attach and grow overnight. Transfection was conducted following manufacturer's instructions. Controls were treated with the 200nM All Star negative control siRNA + 6μl oligofectamine (negative control), while Mettl21c-siRNA-treated cells were transfected with 200nM Mettl21c siRNA + 6μl oligofectamine. Oligofectamine-only vehicle treated cells were used as a vehicle control.

RNA isolation and Real time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) for Mettl21c and Gene Arrays

General Methods

Total RNA was extracted from the cells using the Tri reagent according to manufacturer's protocol, quantified in a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA) by determining absorbance at 260nm in triplicate. RNA purity was indicated by the A260/280 nm absorbance ratio of 1.9-2.1 and A260/230 nm absorbance ratio ≥ 1.8. Using 0.5μg of RNA, each sample was reverse transcribed in a 20μl reaction volume.

Mettl21c

After 24h of transfection, total RNA was isolated as aforementioned and the RNeasy Mini Kit was then employed to purify the RNA. cDNA was synthesized by using high capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit. RT-qPCR was performed using RT2 Real-TimeTM SYBR green/Rox PCR master mix.

RT-qPCR primers were: Forward: 5’-AGGAGCTCAAGTCACAGCAACAGA-3’, Reverse: 5’-AGAGGCCAGCACGTAGTCATAACA-3’. qPCR was run in a 25μl reaction volume on 96-well plates using a StepOnePlus instrument. Data were analyzed using RT2 Profiler™ PCR Array Data Analysis (SABiosciences); CT values were normalized to Gadph (Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) as a reference gene (RT-qPCR primers of Gadph gene were: Forward: 5’-TGCGATGGGTGTGAACCACGAGAA -3’, Reverse: 5’-GAGCCCTTCCACAATGCCAAAGTT-3’). Gene expression was determined as up/down regulation of the gene of interest compared to the controls. All reactions were done in duplicate and all experiments were repeated at least three times.

RT-PCR Gene Arrays

The Mouse Signal Transduction PathwayFinder PCR Array from SABiosciences was used to simultaneously detect gene expression changes of 10 signaling pathways (see details in Results). cDNA was synthesized using the RT2 First Strand Kit and the PCR Array was run according to manufacturer's protocol including a threshold of 0.25 and validation of each gene tested by the identification of single peaks in melting curves. As above, data were analyzed using RT2 Profiler™ PCR Array Data Analysis Software; CT values were normalized to built-in six reference house-keeping genes, genomic DNA control, reverse transcription control, and positive PCR control. We used this analytical software to set the statistical significance of up/down regulation of all tested genes at 2-fold difference.

Cell morphology and cell area measurements

Phase contrast images were taken with 10X and 20X LEICA Phase/FLUO objectives, in a LEICA DMI-4000B inverted microscopy equipped with a 14-BIT Snap Cool CCD camera, using the LEICA LAS imaging software for calibration. Number and area of early (Day 3) and mature (Day 5) myotubes were measured after differentiation and quantitated using the LEICA Application Suite: Advanced Fluorescence software and ImageJ software. Myotubes are defined as muscle cells containing at least 3 nuclei. These experiments were repeated 3-4 times and 3-5 areas per sample (N = 300-500 cells) were randomly selected for the measurements.

Immunostaining

Experiments were performed following our published protocols (11, 21). Briefly, C2C12 cells were fixed with neutral buffered formalin and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100. Myosin Heavy Chain (MHC) was detected with anti-human Myosin Heavy Chain-CFS (1:50) at room temperature for 30 minutes and counter stained with DAPI. Images were taken using a 20X LEICA FLUO objective with the LEICA system described above.

Fusion index

To quantify myogenic differentiation of C2C12 cells after treatment, we calculated the Fusion Index (FI), defined as: (nuclei within MHC-expressing myotubes/total number of myogenic nuclei) × 100 (22).

Intracellular Ca2+ measurements

A Photon Technology International (PTI) imaging system was used to measure intracellular calcium transients produced by the stimulation of calcium release from sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) with 20mM caffeine. Each myotube imaged was loaded with Fura-2, a ratiometric calcium dye. Calcium transients’ analyses were performed using PTI's Felix 32 Photometry system. Experiments included 3-4 repetitions, resulting in 15-18 cells analyzed per group (21, 23).

Determination of MLO-Y4 cell viability

The osteocytic MLO-Y4 cells were chosen as an in vitro model to examine whether Mettl21C affects bone cell viability. MLO-Y4 cells were transfected with 200nM All Star negative control siRNA by using oligofectamine as the transfecting vehicle. Twenty four hours after transfection, images were taken, and the percentage of fluorescent positive cells (All Star negative control siRNA transfected cells) among total cells was detected. As osteocytes are very long-lived bone cells and osteocyte viability affects bone remodeling and repair, MLO-Y4 cells from all groups were treated with dexamethasone (Dex) known to induce osteocyte apoptosis. The percentage of MLO-Y4 cell death following Dex treatment was quantified using the trypan blue exclusion assay and the nuclear fragmentation assay after siRNA transfection following previously published procedures (11, 24, 25). Briefly, after transfection cells were cultured for 48 h and then exposed to phenol red-free culture media with or without dexamethasone (1μM) for 6h. Adherent cells were trypsinized and combined with non-adherent cells. Cells were incubated for 10min with 0.1% trypan blue. A Neubauer hemocytometer was used to count viable, non-stained cells, and dead or dying cells that demonstrate blue staining throughout the whole cell body. Results from the trypan blue assay were validated using the nuclear fragmentation assay. Cells were fixed for 10 min at 4°C in 2% neutrally buffered paraformaldehyde and after treatment nuclei were stained with DAPI (0.25mg/mL) for 5min. The percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by counting cells with impaired nuclear membrane that demonstrate nuclear “blebbing” versus non-impaired cells. All aforementioned experiments were repeated 3-4 times and on average 100 cells per replicate were counted.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). Comparisons were made using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test for multiple comparisons. P value < 0.05 was considered as being significantly different.

Results

Bivariate GWAS of bone and muscle phenotypes

Our GWAS analyses yielded a number of genome-wide significant (bivariate p < 5×10−8) and suggestive (bivariate p < 5×10−6) scoring genes. Several were well known to be associated with bone mass, such as LRP5 and RSPO3, or with anthropometric traits (e.g. ADAMTSL3, LYPLAL1). One of the genome-wide suggestive genes, METTL21C, with bivariate GWAS p = 2.3×10−7 (for variant rs895999), was chosen for validation based on an early observation showing this gene is highly expressed in muscle (http://www.genecards.org/cgibin/carddisp.pl?gene=METTL21C), played a role in bovine muscle characteristics (16), and sequence homology suggested it should function as a methyltransferase (17). In addition, this candidate gene has been found to localize in the nucleus, and its close homologue, METTL21D was found to bind to the chaperone VCP, known to play a role in a muscle specific disease (i.e., Inclusion Body Myopathy) associated with a bone-specific disease (i.e., Paget's Disease) (17).

Partial knockdown of Mettl21c inhibited myoblast differentiation

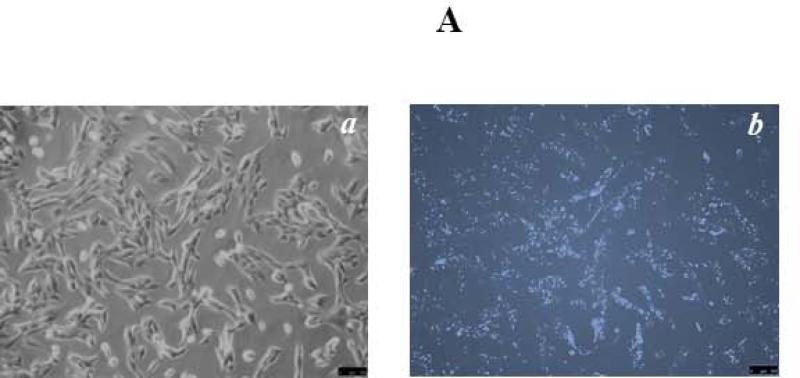

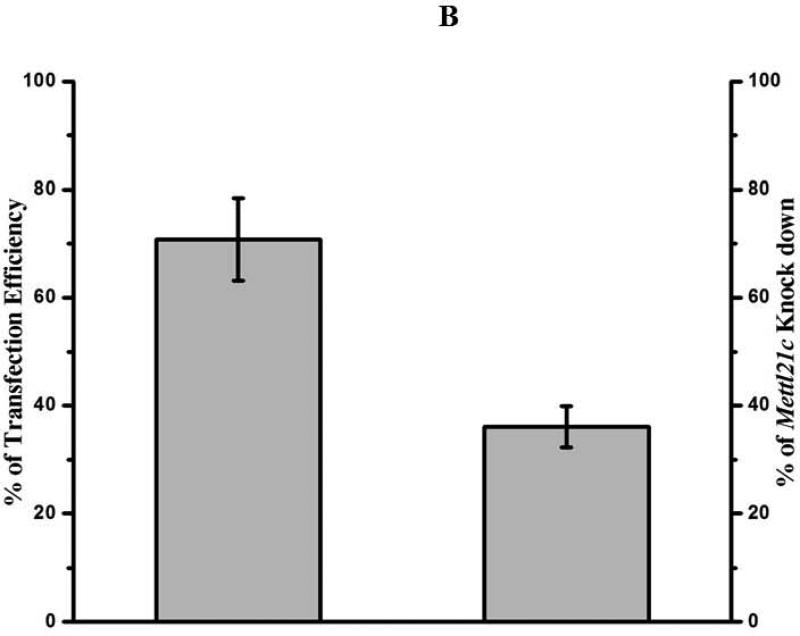

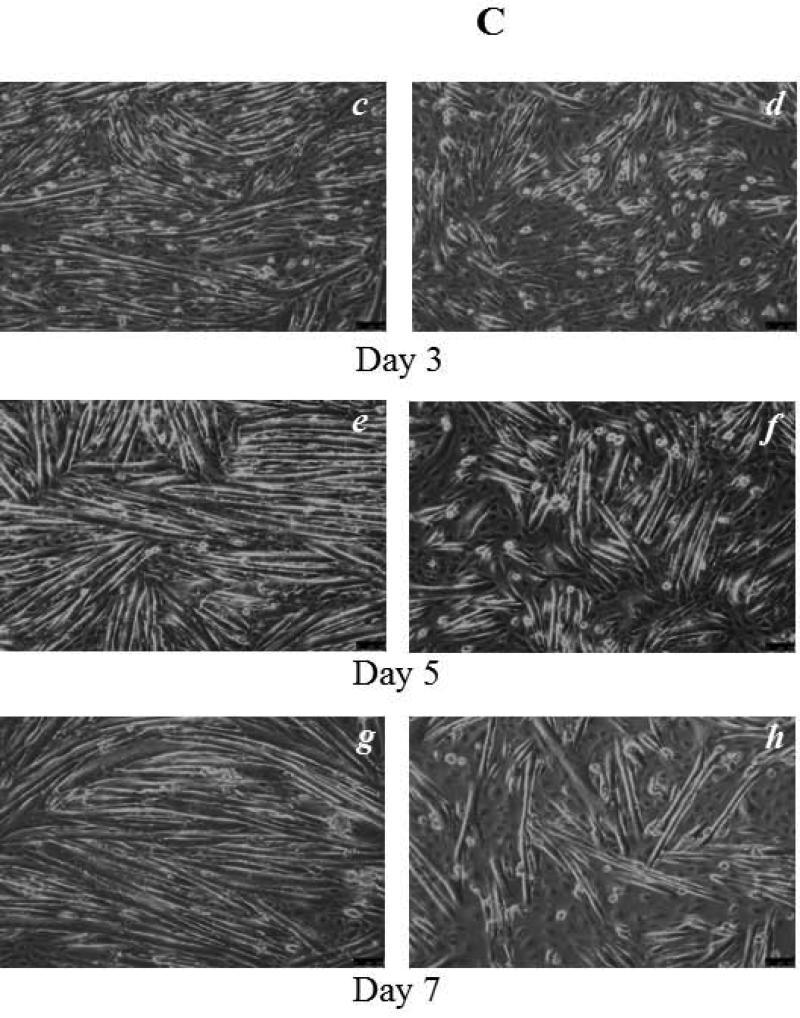

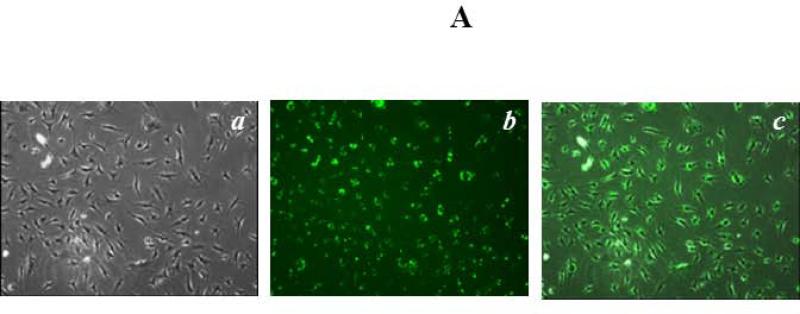

To explore the possible roles of Mettl21c in myogenesis, C2C12 myoblasts were used. Upon FBS starvation and switch to horse serum, C2C12 myoblasts fuse to form multinucleated myotubes (26). To determine siRNA transfection efficiency, C2C12 myoblasts were transfected with 40nM All Star negative control siRNA by using GenMute siRNA Transfection Reagent for C2C12 cell. Twenty four hours after transfection, images were taken (Fig. 1A), and the percentage of fluorescent positive cells was determined. The result showed a siRNA transfection efficiency of C2C12 myoblasts of 70.8 ± 7.6% (Fig. 1B). RT-qPCR was conducted to examine the effectiveness of Mettl21c knockdown by Mettl21c siRNA on gene expression. The results indicated that the relative Mettl21c mRNA expression in the siRNA-treated cells was 36.1 ± 4.0% less than the negative control cells when normalized to expression of Gapdh, which was not altered by the negative control, vehicle control or siRNA treatments (Fig. 1B-C). To explore Mettl21c function in C2C12 myoblast differentiation, we observed control and siRNA treated cells daily for potential phenotypic changes and systematically analyzed them at days 3 and 5 of differentiation (Fig. 1C, panels’ c-f). At day 3 of differentiation, a reduced number of myocytes for fusion was observed in the Mettl21c-siRNA-treated group compared to both negative control and vehicle control groups, while there was no detectable difference between the two control groups (Fig. 1C, c-d). At day 5 of differentiation, fewer, shorter, and smaller myotubes were observed in the Mettl21c-siRNA-treated group compared to negative control and vehicle control (Fig. 1C, e-f). By differentiation day 7, fully matured and developed myotubes were observed in negative control and vehicle control, but not in the Mettl21c-siRNA-treated group. The Mettl21csiRNA-treated group had fewer, shorter, and smaller myotubes (Fig. 1C, g-h). Quantitative data for the number of myotubes at differentiation day 3 and day 5 are summarized in Table 1. Four random image areas were used for all quantifications. The number of myotubes observed in Mettl21c-siRNA-treated group was much less (30.8 ± 3.6/per random image area, PRIA) compared to negative control (61.8 ± 7.4/PRIA) and vehicle control (61.5 ± 6.4/PRIA) (p < 0.05) at day 3. At day 5, the number of myotubes observed in Mettl21c-siRNA-treated cells was 51.5 ± 6.9/PRIA compared to negative control (79.8 ± 8.0/PRIA) and vehicle control (80.8 ± 8.0/PRIA) (p < 0.05). At both day 3 and day 5, there was no difference between negative control and vehicle control.

Fig 1. Partial Knockdown of Mettl21C Alters the Morphological Phenotype of C2C12 Myoblasts during Myogenic Differentiation Indicating Impaired Myogenesis.

A) Representative image of C2C12 myoblasts 24 hours after transfection by All Star negative control siRNA (40nM). a) Phase contrast image, b) Fluorescent image, both images taken from the same representative area. For quantification, 4 different areas (~400 cells) were used from 5 different experiments. B) Under these experimental conditions (see Methods for details) transfection efficiency equaled 70.8 ± 7.6%, leading to a decrease of 36.1 ± 4.0% in Mettl21c expression as detected by RT-qPCR. C) Each pair of images (c-d, e-f, g-h) shows representative high resolution 14-BIT CCD camera phase contrast images of the negative control and Mettl21csiRNA-treated C2C12 cells, at 3, 5, and 7 days of differentiation, respectively. Significantly less in number and smaller myotubes are observed in Mettl21c-siRNA-treated C2C12 cells during differentiation. Vehicle control results were essentially identical to the negative control (See Table 1). Calibration bar = 100μm.

Table 1.

Number of myotubes in Mettl21c-siRNA-treated, negative control and mock control C2C12 cultures at differentiation days 3 and 5 (N =4).

| Treatment | Mettl21c siRNA | Negative control | Vehicle control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differentiation day 3 | 30.8 ± 3.6* | 61.8 ± 7.4 | 61.5 ± 6.4 |

| Differentiation day 5 | 51.5 ± 6.9* | 79.8 ± 8.0 | 80.8 ± 8.0 |

p < 0.05 versus negative control and vehicle control

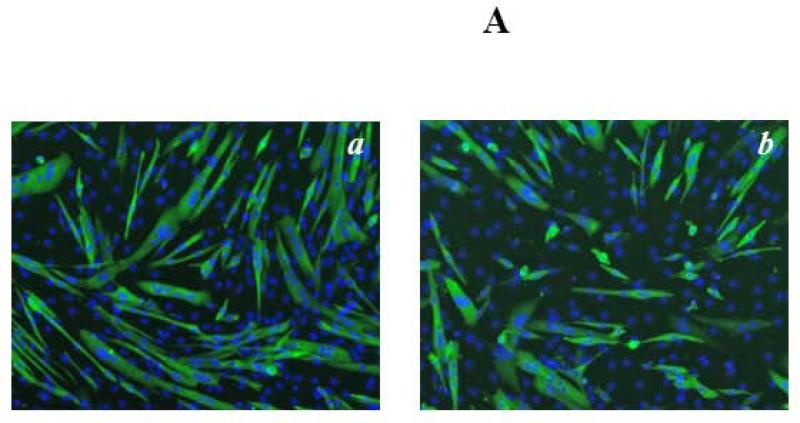

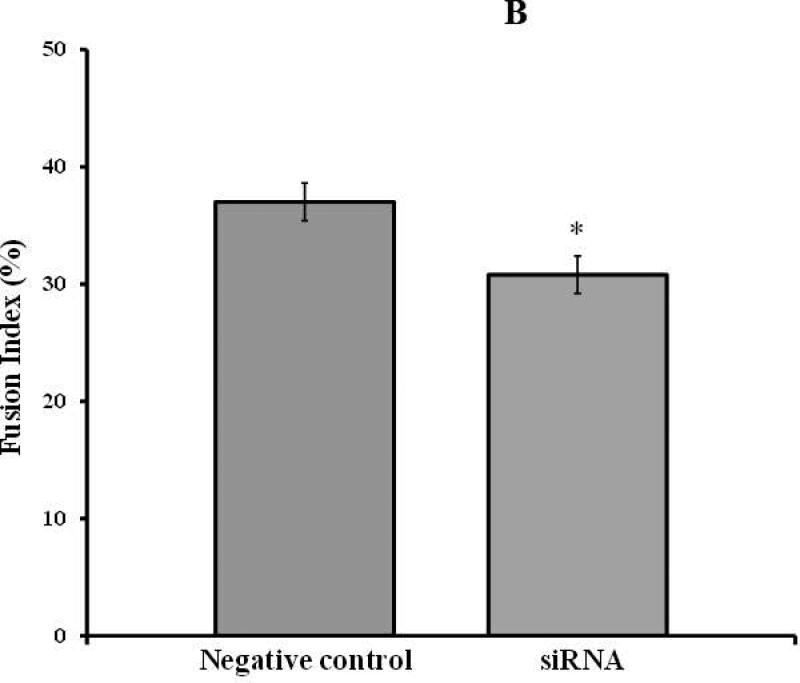

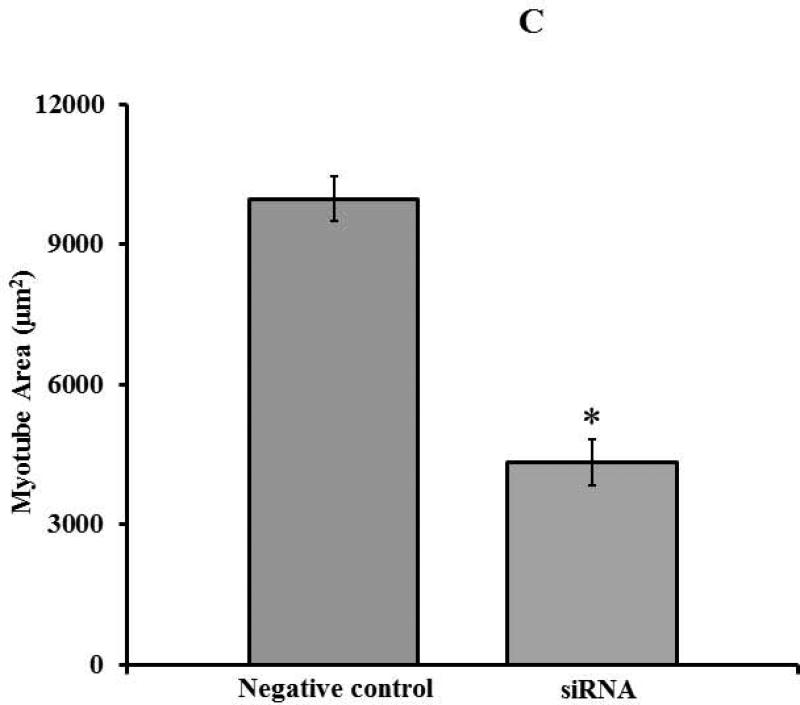

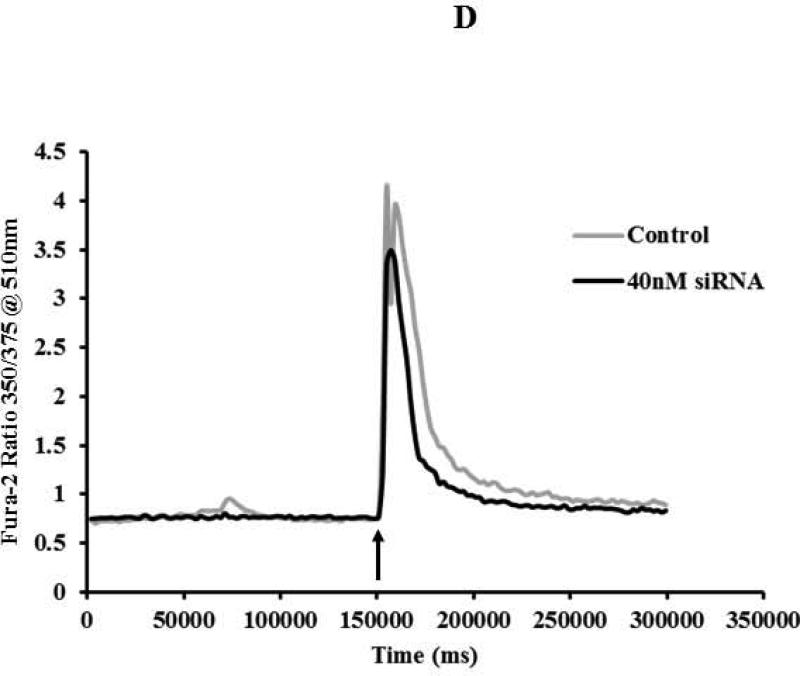

Partial knockdown of Mettl21c reduces Fusion Index and myotube Cell Area, which correlates with blunted caffeine induced calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum

To confirm and expand on our aforementioned histomorphometric observations, Mettl21c-siRNA-treated cells and control cells were stained with anti-human Myosin Heavy Chain-CFS antibody which only stains maturing myocytes/myotubes but not myoblasts (Fig 2A). In agreement with our microscopy studies, we found a significant reduction in the Fusion Index of Mettl21c-siRNA-treated cells (30.8 ± 1.6%) as compared with the negative control cells (37.0 ± 1.4%, p < 0.05) (Fig. 2B). Also this finding was further confirmed by measuring myotube area (9971 ± 471.7μm2 negative control vs. 4324 ± 497.8 μm2 for Mettl21c-siRNA-treated myotubes, n=100, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2C). Since calcium homeostasis is very important in myoblast differentiation (27), and is a major surrogate of skeletal muscle function (23, 27, 28), we determined if SR calcium release was influenced by the partial silencing of Mettl21c by monitoring Fura-2 intracellular calcium transients in response to caffeine-induced SR Ca2+ release. In Mettl21csiRNA-treated C2C12 myotubes at day 5 of differentiation, compared to negative control, the amplitude peak Ca2+ response to caffeine decreased 16.1% (2.78 ± 0.03 vs. 3.31 ± 0.03, respectively, mean ± SEM) and the relaxation phase (i.e., time to return from peak to baseline) of caffeine-induced calcium transients was 23.0% shorter (110802 ± 597ms vs. 85298 ± 395ms, respectively, mean ± SEM) (Fig. 2D).

Fig 2. Partial Silencing of Mettl21c Reduces Fusion Index, Myotube Cell area, and Calcium Release from the Sarcoplasmic Reticulum.

A) Representative fluorescence images of DAPI-stained nuclei (blue) and myosin heavy chain antibody (MHC, green) of C2C12 at 3 days of differentiation after transfection. a) Negative control and b) Mettl21c-siRNA-treated C2C12 cells. B) Summary data show that the Fusion Index in Mettl21c-siRNA-treated C2C12 cells decreased significantly compared to negative control (p<0.05). C) Summary data show that myotube cell area in Mettl21c-siRNA-treated C2C12 cells drastically decreased compared to negative control (p<0.0001). D) Representative calcium transients induced by 20mM caffeine (arrow) on C2C12 myotubes loaded with Fura-2/AM. In Mettl21c-siRNA-treated C2C12 myotubes at day 5 of differentiation, compared to negative control, the amplitude peak calcium response to caffeine was significantly decreased and the relaxation phase of the transient was shorter (p<0.01).

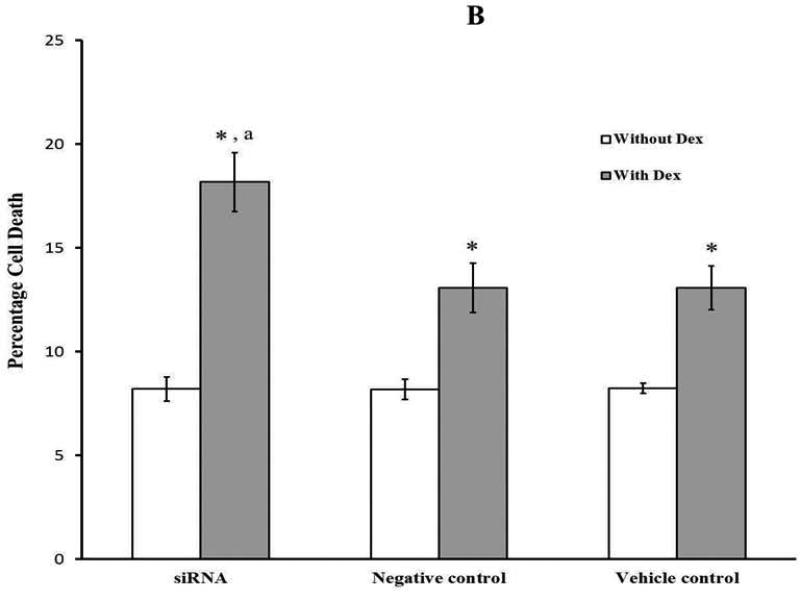

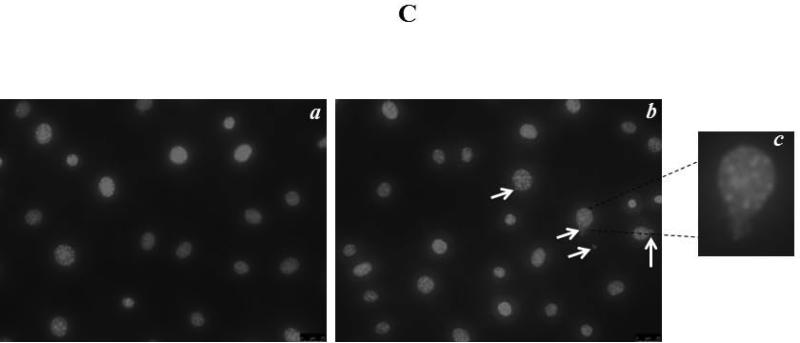

Knockdown of Mettl21c mRNA in MLO-Y4 osteocyte cells increased cell death induced by dexamethasone

MLO-Y4 cells were transfected with 200nM All Star negative control siRNA by using oligofectamine as the transfecting vehicle. Twenty four hours after transfection, images were taken, and the percentage of fluorescent positive cells (All Star negative control siRNA transfected cells) among total cells was detected. The result revealed that the siRNA transfection efficiency of MLO-Y4 cells was 69.3 ± 7.4%, similar to that of the C2C12 myoblasts (Fig. 3A). Compared to negative and vehicle controls, no obvious differences in cell number or cell morphology were observed in siRNA treated MLO-Y4 cells. MLO-Y4 cells from all groups were treated with dexamethasone (Dex) known to induce osteocyte apoptosis. Fig. 3B summarizes results showing that without Dex treatment, there was no significant difference between the three experimental groups. In contrast, with Dex treatment, the percentage of cell death in Mettl21c-siRNA-treated cells (18.17 ± 1.41%) increased significantly (p < 0.05) compared to negative control (13.06 ± 1.18%) and vehicle control (13.07 ± 1.05%) groups. Furthermore, this result was also confirmed by using the nuclear fragmentation assay (p < 0.05) that is illustrated in Fig. 3C.

Fig 3. Partial Knockdown of Mettl21c in MLO-Y4 osteocytes increased cell death induced by dexamethasone.

A) Representative image of MLO-Y4 osteocytes 24 hours after transfection of All Star negative control siRNA (200nM). a) Phase contract image, b) Fluorescent image of tagged siRNA; Both images were taken from the same area; c) Merging of a) and b). B) Summary data of cell death in MLO-Y4 cells transfected with Mettl21C siRNA, with and without dexamethasone (Dex) treatment. Cell death was detected 48h after treatment by trypan blue exclusion assay (*Dex increased cell death under all conditions; and aMettl21c knockdown induced cell death levels higher than Dex alone, p < 0.05). C) The Nuclear fragmentation assay shows the a) absence of nuclear blebbing in control MLO-Y4 cells as compared with the b) enhanced blebbing in the siRNA-treated MLO-Y4 osteocytes; c) The enlarged image clearly shows the blebbing process in siRNA-treated MLO-Y4 osteocytes.

Modulation of the NFκB signaling pathway by partial knockdown of Mettl21c

To study the potential mechanism of Mettl21c gene function in the inhibition of C2C12 myoblast differentiation, we used the Mouse Signal Transduction PathwayFinder PCR Array to detect the difference of gene expression between the control and the siRNA-treated C2C12 cells. This gene array monitored 10 different pathways, detailed in Table 2. Among all these genes, we found that the expression of only three genes (Birc3, Ccl5 and Tnf) was significantly altered. In Mettl21c-siRNA-treated C2C12 cells, compared to negative control, the expression of Birc3 and Ccl5 was increased by 3.65 fold and 3.07 fold, respectively, while the expression of Tnf decreased by 4.11 fold. As detailed above, these three genes are directly associated with the NFκB Pathway. This result indicated that Mettl21C may function through the NFκB pathway to regulate C2C12 myoblast differentiation, since none of the other pathways tested were affected by the specific knockdown of Mettl21c.

Table 2.

Pathways and genes in Mouse Signal Transduction PathwayFinder PCR Array

| Signaling Pathways | Genes |

|---|---|

| TGFβ Pathway | Atf4, Cdkn1b (p27Kip1), Emp1, Gadd45b, Herpud1, Ifrd1, Myc, Tnfsf10 |

| WNT Pathway | Axin2, Ccnd1, Ccnd2, Dab2, Fosl1 (Fra-1), Mmp7 (Matrilysin), Myc, Ppard, Wisp1 |

| NFκB Pathway | Bcl2a1a (Bfl-1/A1), Bcl2l1 (Bcl-x), Birc3 (c-IAP1), Ccl5 (Rantes), Csf1 (Mcsf), Icam1, Ifng, Stat1, Tnf. |

| JAK/STAT Pathway | |

| JAK1, 2 / STAT1 | Irf1 |

| STAT3 | Bcl2l1 (Bcl-x), Ccnd1, Cebpd, Lrg1, Mcl1, Socs3 |

| STAT5 | Bcl2l1 (Bcl-x), Ccnd1, Socs3 |

| JAK1, 3 / STAT6 | Fcer2a, Gata3 |

| p53 Pathway | Bax, Bbc3, Btg2, Cdkn1a (p21Cip1/Waf1), Egfr, Fas (Tnfrsf6), Gadd45a, Pcna, Rb1 |

| Notch Pathway | Hes1, Hes5, Hey1, Hey2, Heyl, Id1, Jag1, Lfng, Notch1 |

| Hedgehog Pathway | Bcl2, Bmp2, Bmp4, Ptch1, Wnt1, Wnt2b, Wnt3a, Wnt5a, Wnt6 |

| PPAR Pathway | Acsl3, Acsl4, Acsl5, Cpt2, Fabp1, Olr1, Slc27a4, Sorbs1 |

| Oxidative Stress | Fth1, Gclc, Gclm, Gsr, Hmox1, Nqo1, Sqstm1, Txn1, Txnrd1 |

| Hypoxia | Adm, Arnt, Car9, Epo, Hmox1, Ldha, Serpine1 (PAI-1), Slc2a1, Vegfa |

Discussion

The synchrony of musculoskeletal development supports the notion that bones and muscles are governed by genes with pleiotropic functions (29-32), and several GWAS in humans have confirmed these observations (14, 33). From our bivariate GWAS (18), METTL21C was identified as a suggestive pleiotropic gene for bone and muscle phenotypes.

METTL21C is a member of the seven-β-strand methyltransferase superfamily (34), and also has recently been identified as a member of a new group of distantly related lysine methyltransferases, which preferentially interact with chaperones to regulate their activity. In the case of METTL21C, the 70-kDa heat shock protein (Hsp70) has been shown to be the major interacting chaperone (17). Hsp70s are central components of the cellular network of molecular chaperones and folding catalysts that assist a wide range of folding processes, including the folding and assembly of newly synthesized proteins, refolding of misfolded and aggregated proteins, membrane translocation of organelle and secretory proteins, and control of the activity of regulatory proteins (35).

To begin to identify more precise molecular machinery responsible for this effect, we found a link between Mettl21c and the nuclear factor-kappa B (NFκB) signaling pathway. NFκB is one of the most important signaling pathways linked to the loss of skeletal muscle mass in normal physiological and pathophysiological conditions (36). The activation of NFκB, activator protein-1 (AP-1), p53, Foxo, and p38 mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways lead to skeletal muscle atrophy (37). Although muscle atrophy might involve differential activation of multiple cell signaling pathways, recent evidence suggest that NFκB is one of the most important signaling systems, the activation of which leads to skeletal muscle loss. Accumulating literature suggests that NFκB is essential for myoblast proliferation and for their maintenance in undifferentiated state. NFκB inhibits myogenic differentiation presumably by stimulating cyclin D1 accumulation and cell cycle progression (38, 39). The activation of NFκB was effective in blocking the differentiation of myoblasts into myotubes (40).

It is also possible that METTL21C could play a role in bone and muscle formation and function through the methylation of the Hsp70 chaperone, since it was recently shown to specifically bind and methylate Hsp70 (17). This is a tantalizing hypothesis since Hsp70 has significant functional roles in both cardiac and skeletal muscles, including hypoxia, hypoxia/reperfusion, muscle fatigue and aging and it is thought to act on intracellular calcium homeostasis (41-44). In fact, previous reports have suggested that the maintenance of normal intracellular calcium concentration is vital to myocyte gene expression and differentiation (45). Furthermore, HSP70 has been established an important modulator of the NFκB signaling pathway (46-50).

Our results showing that intracellular calcium homeostasis was altered in Mettl21c-siRNA-treated myotubes is consistent with the inhibition of myocyte differentiation and a potential role of modification of heat shock proteins through METTL21C. On the other hand, a simpler explanation is that the alteration of intracellular calcium homeostasis is a secondary effect of differentiation inhibition and in depth studies will be required to pin-point the roles of METTL21C in skeletal muscle excitation–contraction coupling.

Using the Mouse Signal Transduction PathwayFinder PCR Array (Table 2), we found that the expression of three protein coding genes (Birc3, Ccl5 and Tnf) was significantly altered. Birc3 (baculoviral IAP repeat-containing 3), is located on mouse chromosome 9. Birc3 is involved in the NFκB pathway (51, 52) and is part of the IAP (inhibitors of apoptosis proteins) family, known for their role in anti-cell death mediation (53). Ccl5, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5, is located on murine Chromosome 11. Ccl5 is a downstream gene of NFκB (54). Corti et al. showed that Ccl5 increased myoblast migratory activity; this was the first evidence that chemokines may act on skeletal muscle cells (55). During muscle regeneration, macrophage infiltration, and the expression of cytokines (IL-1β, inducible NO synthase, TGF-β1, IL-10) and chemokines (CCL2, CCL3, CCL5) were all increased after injury in muscles from normal, wild type mice (56). De Paepe et al. found that in Duchenne muscular dystrophy, up-regulation of CCL5 expression by cytotoxic macrophages may regulate myofiber necrosis (57).

Tnf (tumor necrosis factor, also known as Tnf-α) is located on murine chromosome 17. It has been reported that mechanical stimulation leads to release of TNF by myoblasts, which is necessary for myogenic differentiation (58). TNF is known to be one of the key regulators of skeletal muscle cell responses to injury. Whereas physiological levels of Tnf are transiently up-regulated during myoblast regenerative responses to injury and stimulate differentiation (59), sustained high levels of TNF are associated with chronic inflammatory diseases and especially with muscle pathology associated with impairment of differentiation and muscle wasting (60). Tnf has been found to exert many of its effects on skeletal muscle through nuclear factor NFκB signaling (36). Therefore, the upregulation of Birc3 and Ccl5 might suggest a role in inhibition of myotube formation or myotube cell death, while the four-fold downregulation of Tnf might suggest a compensatory mechanism by itself and serve as a modulator of cell response. On the other hand, the partial knockdown of Mettl21c might lead to a complex modulation of the NFκB signaling pathway that will require future studies beyond the scope of our current study. Intriguingly, a TNF-BIRC3 crosstalk has been linked to C2C12 apoptosis (61, 62). Irrespective of plausible interpretations, there is no doubt that changes in the activity of this essential signaling pathway might be seen as the molecular foundation for the phenotypic changes observed in both the C2C12 muscle cells and MLO-Y4 osteocytes.

The osteocyte is the most abundant cell type in bone, constituting 90% to 95% of all bone cells, and is a key cell that is indispensable in orchestrating bone remodeling by regulating both osteoblast and osteoclast function. This cell is multifunctional and appears to integrate hormonal and mechanical signals in the regulation of bone mass (8) necessary for the normal function of the skeleton. Our findings that knockdown of Mettl21c increased dexamethasone-mediated osteocyte apoptosis in MLO-Y4 cells indicates Mettl21c has a potential role in maintaining osteocyte viability upon exposure to apoptotic agents such as dexamethasone. This protection against glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in osteocytes might be directly related to Birc3, since this NFκB related gene is an anti-apoptotic gene (53). Increased osteocyte apoptosis has been shown to play an important role in the decreased skeletal strength observed with glucocorticoid treatment (63), and it was recently reported that the bone loss observed in Crohn's Disease was associated with increased osteocyte death and decreased bone remodeling (64). Apoptotic bodies released by MLO-Y4 cells and primary osteocytes support osteoclast formation (65). Furthermore, NFκB signaling mediates RANK ligand-induced osteoclastogenesis and this pathway is also thought to be a center of inflammatory responses and is considered a potent mediator of inflammatory osteolysis (for a review see Abu-Amer (66)) and being critical for overall bone remodeling (67).

In conclusion, using the in silico bivariate GWAS approach, we discovered a suggestive pleiotropic gene - METTL21C - regulating hip geometry and muscle mass of the extremities. Such “bridging” between in silico discovery and in vitro validation is rarely done to follow up GWAS signals. In vitro studies using C2C12 myoblasts/myotubes and MLO-Y4 osteocyte-like cells confirmed that Mettl21c played roles in myogenesis and calcium homeostasis in muscle cells, and in osteocyte viability and resistance to apoptosis. These changes in bone and muscle cells can be explained by the modulation of the NFκB signaling pathway by Mettl21c. To our knowledge, these are the first in vitro studies aimed at validating potential bone-muscle pleiotropic genes as well as the first studies to directly link Mettl21c with the NFκB signaling pathway. As no previous studies have validated potentially pleiotropic genes in mammalian models, our study it the first to provide a compelling framework for future studies aimed to biologically validate findings from multi-trait GWAS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was directly supported by NIH-NIA P01 AG039355 (LB, MB), the Thompson Endowment Fund (MB), R01 AR057118 (DK), and R01 AR/AG 41398 (DPK). We also acknowledge and in debt to the CHARGE Consortium Musculoskeletal Working Group (depts.washington.edu/chargeco/wiki/) and the GEFOS/GENOMOS Consortium (www.gefos.org and www.genomos.eu) for providing full access to the aggregate results of a genome-wide association study meta-analysis. The full list of individuals and grants providing support for the joint work through these two consortia is available in an online Supplement.

Authors’ roles: Study design: DK, DPK, MB and YHH. Study conduct: YHH, JH and CM. Data collection: YHH, JH, CM and EA. Data analysis: YHH, JH, EA and DK. Data interpretation: DK, MB, LB and DPK. Drafting manuscript: JH, MB and EA. Revising manuscript: JH, YHH, CM, EA, DPK, LB, MB and DK. Approving final version of manuscript: JH, MB and DK. MB and DK take responsibility for the integrity of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Disclosures: All authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bijlsma AY, Meskers CG, Westendorp RG, Maier AB. Chronology of age-related disease definitions: osteoporosis and sarcopenia. Ageing Res Rev. 2012;11(2):320–4. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buford TW, Anton SD, Judge AR, Marzetti E, Wohlgemuth SE, Carter CS, et al. Models of accelerated sarcopenia: critical pieces for solving the puzzle of age-related muscle atrophy. Ageing Res Rev. 2010;9(4):369–83. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brotto M, Abreu EL. Sarcopenia: pharmacology of today and tomorrow. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;343(3):540–6. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.191759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janssen I, Shepard DS, Katzmarzyk PT, Roubenoff R. The healthcare costs of sarcopenia in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(1):80–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karsenty G, Ferron M. The contribution of bone to whole-organism physiology. Nature. 2012;481(7381):314–20. doi: 10.1038/nature10763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pedersen BK. Muscles and their myokines. J Exp Biol. 2011;214(Pt 2):337–46. doi: 10.1242/jeb.048074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamrick MW. A role for myokines in muscle-bone interactions. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2011;39(1):43–7. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e318201f601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dallas SL, Prideaux M, Bonewald LF. The Osteocyte: An Endocrine Cell and More. Endocr Rev. 2013 doi: 10.1210/er.2012-1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mo C, Romero-Suarez S, Bonewald L, Johnson M, Brotto M. Prostaglandin E2: from clinical applications to its potential role in bone-muscle crosstalk and myogenic differentiation. Recent Pat Biotechnol. 2012;6(3):223–9. doi: 10.2174/1872208311206030223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chien KR, Karsenty G. Longevity and lineages: toward the integrative biology of degenerative diseases in heart, muscle, and bone. Cell. 2005;120(4):533–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jahn K, Lara-Castillo N, Brotto L, Mo CL, Johnson ML, Brotto M, et al. Skeletal muscle secreted factors prevent glucocorticoid-induced osteocyte apoptosis through activation of beta-catenin. Eur Cell Mater. 2012;24:197–209. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v024a14. discussion -10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu Y, Chen X, Zillikens C, Estrada K, Demissie S, Liu C, Zhou Y, Karasik D, Murabito J, Uitterlinden A, Cupples L, Rivadeneira F, Kiel D, editors. Multi-Phenotype Genome-Wide Association Meta-Analysis on both Lean Body Mass and BMD Identified Novel Pleiotropic Genes that Affected Skeletal Muscle and Bone Metabolism in European Descent Caucasian Populations. J Bone Min Res. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo YF, Zhang LS, Liu YJ, Hu HG, Li J, Tian Q, et al. Suggestion of GLYAT gene underlying variation of bone size and body lean mass as revealed by a bivariate genome-wide association study. Hum Genet. 2013;132(2):189–99. doi: 10.1007/s00439-012-1236-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta M, Cheung CL, Hsu YH, Demissie S, Cupples LA, Kiel DP, et al. Identification of homogeneous genetic architecture of multiple genetically correlated traits by block clustering of genome-wide associations. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(6):1261–71. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kernstock S, Davydova E, Jakobsson M, Moen A, Pettersen S, Maelandsmo GM, et al. Lysine methylation of VCP by a member of a novel human protein methyltransferase family. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1038. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tizioto PC, Decker JE, Taylor JF, Schnabel RD, Mudadu MA, Silva FL, et al. Genome scan for meat quality traits in Nelore beef cattle. Physiol Genomics. 2013;45(21):1012–20. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00066.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cloutier P, Lavallee-Adam M, Faubert D, Blanchette M, Coulombe B. A newly uncovered group of distantly related lysine methyltransferases preferentially interact with molecular chaperones to regulate their activity. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(1):e1003210. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsu YH, Chen X, Estrada K, Demissie S, Richards JB, Zillikens MC, et al. Bivariate genome-wide association analysis identifies novel candidate genes for cross-sectional bone geometry and appendicular lean mass: The GEFOS and CHARGE consortia. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(Suppl 1) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koller DL, Zheng HF, Karasik D, Yerges-Armstrong L, Liu CT, McGuigan F, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide studies identifies WNT16 and ESR1 SNPs associated with bone mineral density in premenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(3):547–58. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kato Y, Windle JJ, Koop BA, Mundy GR, Bonewald LF. Establishment of an osteocyte-like cell line, MLO-Y4. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12(12):2014–23. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.12.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen J, Yu WM, Brotto M, Scherman JA, Guo C, Stoddard C, et al. Deficiency of MIP/MTMR14 phosphatase induces a muscle disorder by disrupting Ca(2+) homeostasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11(6):769–76. doi: 10.1038/ncb1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Filigheddu N, Gnocchi VF, Coscia M, Cappelli M, Porporato PE, Taulli R, et al. Ghrelin and des-acyl ghrelin promote differentiation and fusion of C2C12 skeletal muscle cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(3):986–94. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-05-0402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao X, Weisleder N, Thornton A, Oppong Y, Campbell R, Ma J, et al. Compromised store-operated Ca2+ entry in aged skeletal muscle. Aging Cell. 2008;7(4):561–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00408.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahuja SS, Zhao S, Bellido T, Plotkin LI, Jimenez F, Bonewald LF. CD40 ligand blocks apoptosis induced by tumor necrosis factor alpha, glucocorticoids, and etoposide in osteoblasts and the osteocyte-like cell line murine long bone osteocyte-Y4. Endocrinology. 2003;144(5):1761–9. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-221136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitase Y, Barragan L, Qing H, Kondoh S, Jiang JX, Johnson ML, et al. Mechanical induction of PGE2 in osteocytes blocks glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis through both the beta-catenin and PKA pathways. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(12):2657–68. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yaffe D, Saxel O. Serial passaging and differentiation of myogenic cells isolated from dystrophic mouse muscle. Nature. 1977;270(5639):725–7. doi: 10.1038/270725a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thornton AM, Zhao X, Weisleder N, Brotto LS, Bougoin S, Nosek TM, et al. Store-operated Ca(2+) entry (SOCE) contributes to normal skeletal muscle contractility in young but not in aged skeletal muscle. Aging (Albany NY) 2011;3(6):621–34. doi: 10.18632/aging.100335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park KH, Brotto L, Lehoang O, Brotto M, Ma J, Zhao X. Ex vivo assessment of contractility, fatigability and alternans in isolated skeletal muscles. J Vis Exp. 2012;(69):e4198. doi: 10.3791/4198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Szulc P, Beck TJ, Marchand F, Delmas PD. Low skeletal muscle mass is associated with poor structural parameters of bone and impaired balance in elderly men--the MINOS study. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20(5):721–9. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.041230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dowthwaite JN, Scerpella TA. Skeletal geometry and indices of bone strength in artistic gymnasts. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2009;9(4):198–214. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamrick M. JMNI Special Issue: Basic Science and Mechanisms of Muscle-Bone Interactions. JMNI Special Issue: J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2010;10(1):1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perrini S, Laviola L, Carreira MC, Cignarelli A, Natalicchio A, Giorgino F. The GH/IGF1 axis and signaling pathways in the muscle and bone: mechanisms underlying age-related skeletal muscle wasting and osteoporosis. J Endocrinol. 2010;205(3):201–10. doi: 10.1677/JOE-09-0431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo L, Tang K, Quan Z, Zhao Z, Jiang D. Association Between Seven Common OPG Genetic Polymorphisms and Osteoporosis Risk: A Meta-Analysis. DNA Cell Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1089/dna.2013.2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petrossian TC, Clarke SG. Uncovering the human methyltransferasome. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10(1):M110, 000976. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.000976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mayer MP, Bukau B. Hsp70 chaperones: cellular functions and molecular mechanism. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62(6):670–84. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4464-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li H, Malhotra S, Kumar A. Nuclear factor-kappa B signaling in skeletal muscle atrophy. J Mol Med (Berl) 2008;86(10):1113–26. doi: 10.1007/s00109-008-0373-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guttridge DC. Signaling pathways weigh in on decisions to make or break skeletal muscle. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2004;7(4):443–50. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000134364.61406.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guttridge DC, Albanese C, Reuther JY, Pestell RG, Baldwin AS., Jr. NF-kappaB controls cell growth and differentiation through transcriptional regulation of cyclin D1. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(8):5785–99. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mitin N, Kudla AJ, Konieczny SF, Taparowsky EJ. Differential effects of Ras signaling through NFkappaB on skeletal myogenesis. Oncogene. 2001;20(11):1276–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Langen RC, Schols AM, Kelders MC, Wouters EF, Janssen-Heininger YM. Inflammatory cytokines inhibit myogenic differentiation through activation of nuclear factor-kappaB. FASEB J. 2001;15(7):1169–80. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iwaki K, Chi SH, Dillmann WH, Mestril R. Induction of HSP70 in cultured rat neonatal cardiomyocytes by hypoxia and metabolic stress. Circulation. 1993;87(6):2023–32. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.6.2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mestril R, Chi SH, Sayen MR, Dillmann WH. Isolation of a novel inducible rat heat-shock protein (HSP70) gene and its expression during ischaemia/hypoxia and heat shock. Biochem J. 1994;298(Pt 3):561–9. doi: 10.1042/bj2980561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nosek TM, Brotto MA, Essig DA, Mestril R, Conover RC, Dillmann WH, et al. Functional properties of skeletal muscle from transgenic animals with upregulated heat shock protein 70. Physiol Genomics. 2000;4(1):25–33. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.2000.4.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Broer L, Demerath EW, Garcia ME, Homuth G, Kaplan RC, Lunetta KL, et al. Association of heat shock proteins with all-cause mortality. Age (Dordr) 2013;35(4):1367–76. doi: 10.1007/s11357-012-9417-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Porter GA, Jr., Makuck RF, Rivkees SA. Reduction in intracellular calcium levels inhibits myoblast differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(32):28942–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203961200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guzhova IV, Darieva ZA, Melo AR, Margulis BA. Major stress protein Hsp70 interacts with NF-kB regulatory complex in human T-lymphoma cells. Cell Stress Chaperones. 1997;2(2):132–9. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(1997)002<0132:msphiw>2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Molle W, Wielockx B, Mahieu T, Takada M, Taniguchi T, Sekikawa K, et al. HSP70 protects against TNF-induced lethal inflammatory shock. Immunity. 2002;16(5):685–95. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00310-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ran R, Lu A, Zhang L, Tang Y, Zhu H, Xu H, et al. Hsp70 promotes TNF-mediated apoptosis by binding IKK gamma and impairing NF-kappa B survival signaling. Genes Dev. 2004;18(12):1466–81. doi: 10.1101/gad.1188204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen H, Wu Y, Zhang Y, Jin L, Luo L, Xue B, et al. Hsp70 inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced NF-kappaB activation by interacting with TRAF6 and inhibiting its ubiquitination. FEBS Lett. 2006;580(13):3145–52. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.04.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Senf SM, Dodd SL, McClung JM, Judge AR. Hsp70 overexpression inhibits NF-kappaB and Foxo3a transcriptional activities and prevents skeletal muscle atrophy. FASEB J. 2008;22(11):3836–45. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-110163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jin HS, Lee DH, Kim DH, Chung JH, Lee SJ, Lee TH. cIAP1, cIAP2, and XIAP act cooperatively via nonredundant pathways to regulate genotoxic stress-induced nuclear factor-kappaB activation. Cancer Res. 2009;69(5):1782–91. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sarkar SA, Kutlu B, Velmurugan K, Kizaka-Kondoh S, Lee CE, Wong R, et al. Cytokine-mediated induction of anti-apoptotic genes that are linked to nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-kappaB) signalling in human islets and in a mouse beta cell line. Diabetologia. 2009;52(6):1092–101. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1331-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang CY, Mayo MW, Korneluk RG, Goeddel DV, Baldwin AS., Jr. NF-kappaB antiapoptosis: induction of TRAF1 and TRAF2 and c-IAP1 and c-IAP2 to suppress caspase-8 activation. Science. 1998;281(5383):1680–3. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5383.1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Genin P, Algarte M, Roof P, Lin R, Hiscott J. Regulation of RANTES chemokine gene expression requires cooperativity between NF-kappa B and IFN-regulatory factor transcription factors. J Immunol. 2000;164(10):5352–61. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.10.5352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Corti S, Salani S, Del Bo R, Sironi M, Strazzer S, D'Angelo MG, et al. Chemotactic factors enhance myogenic cell migration across an endothelial monolayer. Exp Cell Res. 2001;268(1):36–44. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang CY, Fu WJ, Xi H, Zhou LL, Jiang H, Du J, et al. [Busulfan, cyclophosphamide and etoposide as conditioning for autologous stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2013;34(4):313–6. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2727.2013.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.De Paepe B, Creus KK, Martin JJ, De Bleecker JL. Upregulation of chemokines and their receptors in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: potential for attenuation of myofiber necrosis. Muscle Nerve. 2012;46(6):917–25. doi: 10.1002/mus.23481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhan M, Jin B, Chen SE, Reecy JM, Li YP. TACE release of TNF-alpha mediates mechanotransduction-induced activation of p38 MAPK and myogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2007;120(Pt 4):692–701. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen SE, Jin B, Li YP. TNF-alpha regulates myogenesis and muscle regeneration by activating p38 MAPK. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292(5):C1660–71. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00486.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Langen RC, Schols AM, Kelders MC, Van Der Velden JL, Wouters EF, Janssen-Heininger YM. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibits myogenesis through redox-dependent and - independent pathways. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;283(3):C714–21. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00418.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mahoney DJ, Cheung HH, Mrad RL, Plenchette S, Simard C, Enwere E, et al. Both cIAP1 and cIAP2 regulate TNFalpha-mediated NF-kappaB activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(33):11778–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711122105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tolosa L, Morla M, Iglesias A, Busquets X, Llado J, Olmos G. IFN-gamma prevents TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis in C2C12 myotubes through down-regulation of TNF-R2 and increased NF-kappaB activity. Cell Signal. 2005;17(11):1333–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.O'Brien CA, Jia D, Plotkin LI, Bellido T, Powers CC, Stewart SA, et al. Glucocorticoids act directly on osteoblasts and osteocytes to induce their apoptosis and reduce bone formation and strength. Endocrinology. 2004;145(4):1835–41. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oostlander AE, Bravenboer N, Sohl E, Holzmann PJ, van der Woude CJ, Dijkstra G, et al. Histomorphometric analysis reveals reduced bone mass and bone formation in patients with quiescent Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(1):116–23. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kogianni G, Mann V, Noble BS. Apoptotic bodies convey activity capable of initiating osteoclastogenesis and localized bone destruction. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23(6):915–27. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Abu-Amer Y. NF-kappaB signaling and bone resorption. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(9):2377–86. doi: 10.1007/s00198-013-2313-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xiong J, O'Brien CA. Osteocyte RANKL: new insights into the control of bone remodeling. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(3):499–505. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.