Summary

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are unique in that they have the capacity to differentiate into all of the cell types in the body. We know a lot about the complex transcriptional control circuits that maintain the naive pluripotent state under self-renewing conditions but comparatively less about how cells exit from this state in response to differentiation stimuli. Here, we examined the role of Otx2 in this process in mouse ESCs and demonstrate that it plays a leading role in remodeling the gene regulatory networks as cells exit from ground state pluripotency. Otx2 drives enhancer activation through affecting chromatin marks and the activity of associated genes. Mechanistically, Oct4 is required for Otx2 expression, and reciprocally, Otx2 is required for efficient Oct4 recruitment to many enhancer regions. Therefore, the Oct4-Otx2 regulatory axis actively establishes a new regulatory chromatin landscape during the early events that accompany exit from ground state pluripotency.

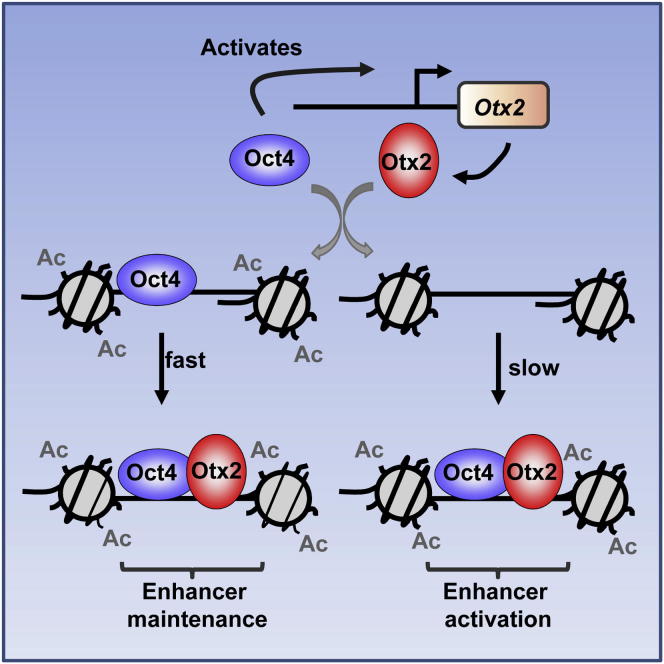

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Transcription factor Otx2 drives enhancer activation in differentiating mouse ESCs

-

•

Oct4 controls Otx2 expression levels

-

•

Otx2 collaborates with Oct4 in enhancer activation

-

•

Otx2 contributes to enhancer maintenance and de novo activation

The transcription factor Otx2 plays an important role in neural development and in the exit of embryonic stem cells from the pluripotent ground state. In this study, Yang et al. demonstrate that Otx2 drives enhancer activation and maintenance during the early cell-fate transition away from ground state pluripotency. Otx2 is involved in a regulatory partnership with Oct4 wherein Oct4 initially promotes Otx2 expression. Otx2 subsequently recruits Oct4 to a subset of enhancers and establishes a regulatory chromatin landscape.

Introduction

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are capable of generating all of the different cell types in the body. This unique property, termed naive pluripotency, is in part determined by their regulatory chromatin landscape that allows extracellular signals to trigger the induction of new gene expression programs that direct transition from this developmental ground state to lineage specification (reviewed in Nichols and Smith, 2012). Ultimately, this culminates in the establishment of new stable chromatin states that define the transcriptional program of differentiated cells (reviewed in Young, 2011, Armstrong, 2012). The transcriptional circuits that enable ESCs to maintain naive pluripotency have been extensively characterized. These involve a core set of transcription factors that include the well-studied Nanog, Klf4, Sox2, and Oct4, but also encompass an increasing number of other transcriptional and chromatin regulators (reviewed in Young, 2011). In comparison, less is known about the gene regulatory mechanisms that drive cells out of the pluripotent ground state toward commitment to differentiation although several recent studies have begun to address this issue (Yang et al., 2012, Davies et al., 2013, Betschinger et al., 2013, Leeb et al., 2014). One of the first events anticipated to occur during transition from the ground state is a re-organization of the chromatin landscape whereby some regulatory regions will be shut down, and new enhancers will become active. Such regulatory region switching is commonly observed during cellular differentiation and development (Nord et al., 2013) and is often driven by pioneering factors like FoxA transcription factors (reviewed in Zaret and Carroll, 2011). However, it is not clear when these events occur or which factors drive enhancer activation in ESCs. Previous studies have identified enhancers in ESCs and differentiated cell types derived from these (Creyghton et al., 2010, Xie et al., 2013, Gifford et al., 2013), but little attention has been given to how cells transit between these two states.

Mouse ESCs (mESCs) can be maintained in defined media that includes two kinase inhibitors (known as “2i”) to block the MEK/ERK and GSK3 signaling pathways (Ying et al., 2008; reviewed in Wray et al., 2010). Addition of cytokine leukemia inhibitory factor is not required for self-renewal in 2i; however, its addition reinforces the ground state through further upregulation of Klf4 and Tcfcp2l1 (Martello et al., 2013). Differentiation can be induced simply by withdrawing the 2i inhibitors and leukemia inhibitory factor (Betschinger et al., 2013). We previously conducted a genome-wide siRNA screen in mESCs to identify factors that regulate exit from ground state pluripotency upon withdrawal of the 2i inhibitors (Yang et al., 2012). More than 400 genes were identified that are important for this transition, many of which encode transcriptional or chromatin regulators. One of these encodes Oct4, which paradoxically is known to be important for maintaining pluripotency (reviewed in Young, 2011) and another encodes the homeodomain transcription factor Otx2. Otx2 has previously been implicated in development of the nervous system and is mutated in patients with brain abnormalities and ocular dysfunction. It also plays an oncogenic role in medulloblastoma (reviewed in Beby and Lamonerie, 2013). More recently, consistent with the results from our RNAi screen, Otx2 was shown to be important for the transition from the embryonic stem cell state to the postimplantation epiblast state (Acampora et al., 2013). Here we show that Otx2 is one of the earliest transcription factors whose expression is activated during exit from the ground state and that it is involved in early enhancer activation, in part through collaborative functional interactions with Oct4.

Results

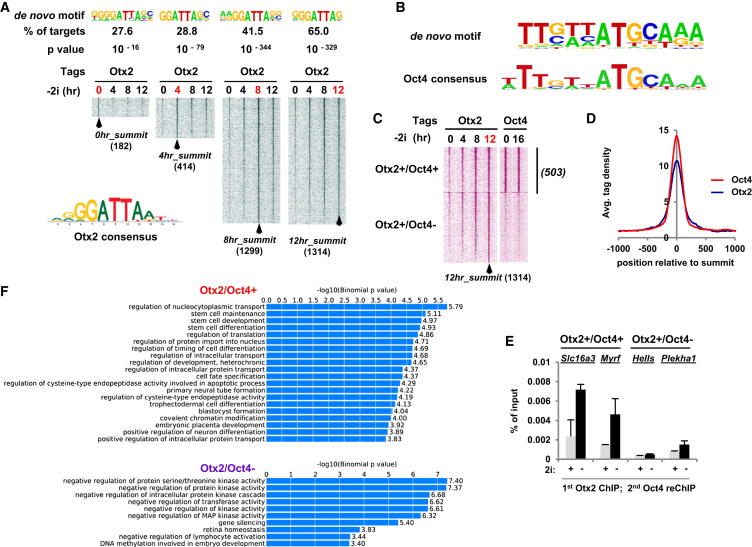

Otx2 and Oct4 Bind to Similar Regulatory Regions

To begin to understand how the gene regulatory landscape of mESCs changes as cells transition from ground state pluripotency, we investigated the potential role for Otx2 in regulatory region activation during this process. We used chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) to monitor the Otx2 genome-wide binding profile over a 12 hr window following release of mESCs from culturing in media containing 2i. Otx2 protein expression increases rapidly over this period (Figure S1A; see also Figure 2D). This increase in expression is accompanied by increasing numbers of genomic binding regions, culminating in 1,314 regions after 12 hr (Figure 1A). The majority of the binding regions exhibit Otx2 occupancy at multiple time points. Gene ontology analysis revealed that a large proportion of the Otx2 binding regions are associated with genes encoding transcriptional regulators that form a highly interconnected network (Figure S1B). Many of these transcriptional regulators such as Jarid2 and Utf1 have been implicated in efficient transition from pluripotency and subsequent differentiation (Yang et al., 2012, Pasini et al., 2010a, Kooistra et al., 2010), suggesting that Otx2 controls an important feed-forward hierarchal regulatory network. In this context, Otx2 might sit at the head of a network of transcriptional regulators that contribute to the gene expression and phenotypic changes accompanying exit from ground state pluripotency. Importantly, among the Otx2 targets were 28 genes that we previously identified in a siRNA screen as playing roles in efficient exit from ground state pluripotency (Yang et al., 2012). De novo motif analysis of the 200 base pairs (bp) surrounding the Otx2 binding summits identified a sequence centered on a core GGATTA motif as the most significant hit at all time points and this closely matches the Otx2 consensus binding motif (Figure 1A; Chatelain et al., 2006, Berger et al., 2008). Importantly, this motif is found in 65% of the targets at 12 hr, providing evidence for direct binding by Otx2 and validation of the quality of the ChIP-seq experiment. In addition to the Otx2 binding motif, we also discovered a motif that matched the Oct4 consensus binding sequence in the Otx2 binding regions, suggesting potential for cobinding of Otx2 and Oct4 (Figure 1B). Indeed, interrogation of Oct4 ChIP-seq data demonstrated that a large proportion of the Otx2 binding regions are also occupied by Oct4 in mESCs and commonly bound regions contain the Oct4 consensus binding motif (Figures 1C and S1C). This enabled us to split the data into two categories; regions bound by Otx2 and Oct4 at one or more time points (Otx2+/Oct4+) and by Otx2 in the absence of Oct4 binding (Otx2+/Oct4−; Figure S1D). In the Otx2+/Oct4+ subgroup, the summits of the Otx2 and Oct4 binding peaks are closely juxtaposed, indicating close association (Figure 1D). However, upon closer inspection, no composite binding motifs with conserved spacing were identified, suggesting co-occupancy but without obligatory direct interactions. Indeed, we were able to demonstrate co-occupancy of Oct4 and Otx2 using re-ChIP analysis by first precipitating Otx2 and then performing sequential ChIP with Oct4 antibodies (Figure 1E) but were unable to detect interactions between Otx2 and Oct4 in coimmunoprecipitation assays.

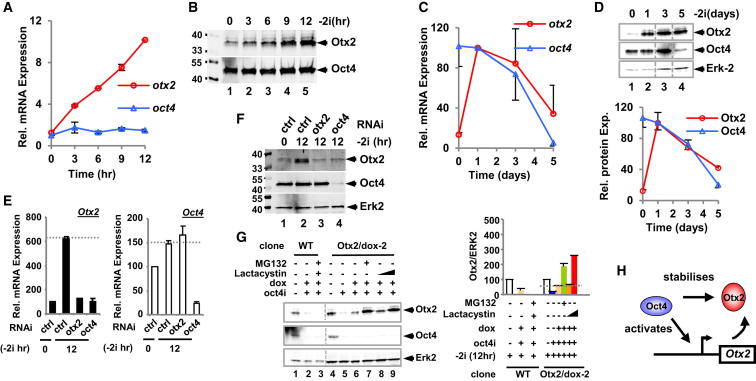

Figure 2.

Interplay between Oct4 and Otx2 Expression

(A and C) qRT-PCR analysis of Otx2 and Oct4 (also known as Pou5f1 but referred to here as Oct4 for clarity) mRNA expression in mouse ESCs (Rex1GFPd2) during the indicated time courses following “2i” withdrawal. Data are normalized by the geometric mean of two reference genes (Ppia and Gapdh) and are presented as means ± SEM and are the average of at least three biological replicates (n ≥ 3).

(B and D) Immunoblots showing Otx2 and Oct4 levels during the indicated time courses of “2i” withdrawal. Dotted lines in (D, upper) indicate where gels have been cut to remove irrelevant lanes and rejoined. Quantification of the data from (D) is shown below and are normalized for Erk2 levels and presented as means ± SEM (n = 3).

(E and F) The expression of Otx2 and Oct4 was analyzed after knockdown of Otx2, Oct4 or in the presence of a nontargeting control siRNA (ctrl) at the indicated times following “2i” withdrawal by qRT-PCR (E) or western blotting (F).

(G) Western blot of Otx2 and Oct4 levels in wild-type (Rex1GFPd2) mESCs and a clonally derived cell line containing a doxycyclin-inducible Otx2 transgene (Otx2/dox-2). Cells are released of, from “2i” for 12 hr. Oct4 depletion (oct4i), the presence (+) or absence (−) of doxycycline (dox) and the proteasome inhibitors, lactacystin and MG132, are indicated. Quantification is shown on the right and is normalized for Erk2 levels and presented as means ± SEM (n = 2).

(H) Model illustrating the impact of Oct4 on Otx2 expression at the RNA and protein levels.

See also Figure S2.

Figure 1.

Otx2 and Oct4 Bind to Similar Regulatory Regions

(A) Heatmap of tag densities of Otx2 binding over 12 hr following exit from pluripotency (−2i). In each heatmap, the Otx2 tag density at that time point (indicated in red) is plotted for 5 kb on either side of its binding peak summit, and the Otx2 tag densities at other time points are plotted on top of these summit coordinates. The most significant de novo motifs discovered in the Otx2 binding regions at each of the time points are shown above the heatmaps, and the consensus Otx2 binding motif is shown below.

(B) De novo motif discovery identifies an enriched motif in the Otx2 binding regions (top) that resembles the Oct4 consensus site (bottom).

(C) Heatmap of normalized Otx2 and Oct4 tag densities at the indicated times following exit from pluripotency (−2i), plotted onto 4 kb regions centered on the Otx2 peak summits at 12 hr. Data are partitioned based on whether there is co-occurrence of Otx2 and Oct4 binding (Otx2+/Oct4+) or Otx2 binding alone (Otx2+/Oct4−).

(D) Average tag density profiles of Otx2 and Oct4 ChIP-seq analyses mapped onto Oct4 binding region summits.

(E) Re-ChIP analysis of Otx2 (first ChIP) and Oct4 (second ChIP) at the indicated loci in the presence of 2i (+) or upon release for 12 hr (−). Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 2).

(F) Gene ontology terms enriched among the genes associated with either the Otx2+/Oct4+ or the Otx2+/Oct4− binding regions. Data are shown graphically according to their p values (x axis) and the associated category (y axis).

See also Figure S1.

Gene ontology analysis revealed that Otx2+/Oct4+ regions are associated with genes involved in various developmental processes including primary neural tube formation, consistent with previous known functions of Otx2 in the development of the nervous system (Figure 1F). However, other commonly overrepresented terms include stem cell differentiation/development consistent with a role in fate transition from ground state pluripotency. In contrast, Otx2+/Oct4− regions are associated with different GO terms, many of which contain genes that cause negative regulation of signaling pathways and gene activation (Figure 1F). Thus, we have defined two types of Otx2 binding region depending on whether Oct4 cobinding occurs and these two different categories of binding region are associated with genes involved in different biological processes.

Oct4 Controls Otx2 Levels

Having established that Otx2 and Oct4 potentially coregulate a large number of genes during exit from pluripotency, we next asked whether they influenced each other’s expression to create a regulatory switch. Otx2 expression at the protein and mRNA levels is rapidly induced over 12 hr as mESCs escape from ground state pluripotency following removal of 2i, whereas Oct4 levels remain relatively stable over the same period (Figures 2A and 2B). Otx2 levels peak at 1 day, and then both Otx2 and Oct4 levels subsequently decrease over an extended period of 5 days (Figures 2C and 2D). These temporal expression patterns suggest that Oct4 might act upstream of Otx2 to control its expression. Indeed depletion of Oct4 resulted in reduced Otx2 mRNA and protein levels, whereas Otx2 depletion had no effect on Oct4 expression (Figures 2E, 2F, S2A, and S2B). In contrast, none of the other pluripotency-associated transcription factors we tested affected Otx2 expression (Figures S2C–S2H), demonstrating the specificity of this effect. Inspection of our ChIP data suggest that the regulatory effect of Oct4 might be direct because Oct4 binding is detected at an enhancer region close to the Otx2 locus, and this region shows evidence of increased H3K27 acetylation as the Otx2 locus becomes activated (Figure S2I).

To attempt to circumvent this regulatory effect of Oct4, we created a mESC line (Otx2/dox-2) harboring a doxycycline-inducible Otx2 transgene. However, although Otx2 mRNA levels were rescued by ectopic Otx2 expression following Oct4 depletion (Figure S2J), incomplete rescue was observed at the protein level (Figure 2G; compare lanes 4 and 6). This suggested that Oct4 might also be required for Otx2 protein stability. Indeed, inclusion of the proteasome inhibitors, MG132 or lactacystin restored Otx2 protein to levels observed upon release from 2i (Figure 2G, lanes 7–9) whereas Oct4 levels were unaffected (Figure S2K). Altogether, these results demonstrate that Oct4 is required for Otx2 transcription and also contributes to stabilizing Otx2 at the protein level (Figure 2H).

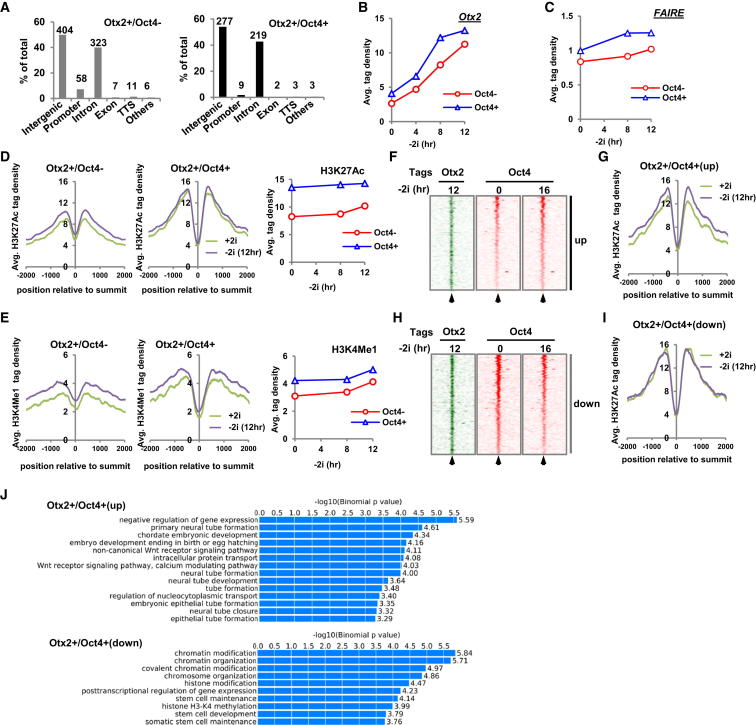

Otx2+/Oct4− and Otx2+/Oct4+ Binding Regions Exhibit Different Functional Properties

Next, we investigated whether there are any potential functional and regulatory differences between regions occupied by Otx2 alone (Otx2+/Oct4−) or in combination with Oct4 (Otx2+/Oct4+). First, we examined the genomic distributions of the two types of binding region. In both cases, the vast majority of binding peaks are associated with intergenic and intronic regions, suggestive of enhancer activity, although significantly more Otx2+/Oct4− peaks are associated with promoter regions (Figure 3A). Both Otx2+/Oct4− and Otx2+/Oct4+ binding regions show increased occupancy by Otx2 over 12 hr following release from 2i, but the Otx2+/Oct4+ binding regions exhibit more rapid occupancy that begins to plateau at 8 hr (Figures 3B and S3A). Furthermore, FAIRE-seq analysis demonstrates that both types of binding region exhibit increased chromatin opening, which also occurs more rapidly in the Otx2+/Oct4+ group (Figures 3C and S3A). These results suggest more rapid establishment of open Otx2-bound enhancer regions in the Otx2+/Oct4+ data set potentially due to the presence of initial Oct4 occupancy. To provide more evidence for enhancer-like properties, we examined H3K4me1 (a general enhancer mark) and H3K27Ac (indicative of active enhancers) around Otx2 binding regions. Both histone marks were found in the nucleosomal regions surrounding the Otx2 binding peaks (Figures 3D and 3E). In mESCs maintained in 2i, higher H3K27Ac levels were observed at regions that become bound by both Otx2 and Oct4 (Otx2+/Oct4+) than those eventually bound by Otx2 alone (Figure 3D), suggesting that these regions represented active enhancers in the ground state. Consistent with this idea, little change in H3K27Ac levels was observed around the Otx2+/Oct4+ binding regions (Figure 3D), but in contrast, enhanced H3K27Ac was observed in the Otx2+/Oct4− binding regions as cells exited from pluripotency. This increase in acetylation is indicative of enhancer activation and this effect is even more dramatic when the Otx2+/Oct4− subcategory is divided in two based on fold changes in H3K27Ac levels, indicating that there is a large subset of enhancers that shows big increases in H3K27Ac, consistent with their activation, and another subset that changes minimally (Figure S3B). Importantly, the increase in H3K27Ac at Otx2-bound enhancers was not due to a generic effect because no global increases in this acetylation event are observed around Oct4-bound regions or other genomic regions (Figures S3C and S3D). H3K4me1 levels were initially higher in Otx2+/Oct4+ binding regions but in contrast to the differential effects seen with H3K27Ac, both Otx2+/Oct4+ and Otx2+/Oct4− binding regions showed an increase in H3K4me1 upon exit from ground state pluripotency (Figure 3E). Together, these results indicate that Otx2 binding correlates with the acquisition of enhancer-like properties, and that de novo enhancer activation occurs preferentially at regions where Otx2 binds in the absence of coassociated Oct4.

Figure 3.

Differential Properties of Otx2+/Oct4− and Otx2+/Oct4+ Binding Regions

(A) Distribution of Otx2 ChIP-seq regions relative to the indicated genomic features. Otx2 binding regions are partitioned into Oct4− (left) and Oct4+ (right) subgroups. The promoter-specific association of Otx2+/Oct4− subgroups is statistically significant (p < 0.01).

(B and C) The average normalized tag densities from Otx2 ChIP-seq (B) or FAIRE-seq (C) analyses (y axes) associated with the summit of Otx2 binding regions from the Otx2+/Oct4− and Otx2+/Oct4+ subgroups are shown for the indicated times following “2i” withdrawal (x axes).

(D and E) Average tag density profiles of H3K27Ac- (D) and H3K4me1-ChIP-seq (E) analyses mapped onto Otx2 binding region summits in the presence of 2i or following 2i withdrawal for 12 hr. The Otx2 peaks are partitioned into Oct4− (left) and Oct4+ (middle) categories. The right images show the average normalized tag densities of K3K27Ac (D) and H3K4me1 (E) ChIP-seq data (y axis) associated with the summit of Otx2 binding regions from the Otx2+/Oct4− and Otx2+/Oct4+ subgroups for the indicated times following “2i” withdrawal (x axis).

(F and H) Heatmaps of Otx2 and Oct4 ChIP-seq tag densities in the 4 kb regions surrounding the summit of Otx2 binding regions at the indicated times following exit from pluripotency (−2i). Data are partitioned into regions showing increased (up; F) or decreased (down; H) binding of Oct4 at 16 hr after 2i withdrawal.

(G and I) Tag density profiles of H3K27Ac ChIP-seq data mapped onto the summits of Otx2 binding regions showing increased (G) or decreased (I) Oct4 binding (see F and H) in the presence of 2i or following 2i withdrawal for 12 hr.

(J) Gene ontology terms enriched among the genes associated with either the Otx2+/Oct4+(up) or the Otx2+/Oct4+(down) binding regions. Data are shown graphically according to their p values (x axis) and the associated functional category (y axis).

See also Figure S3.

Next, to examine a potential contribution of Oct4 in enhancer activation, we further partitioned the Otx2+/Oct4+ binding regions into those which exhibited increased Oct4 binding (Oct4 up) or no change/decreased Oct4 binding (Oct4 down) 16 hr after release from 2i (Figures 3F, 3H, andS3E). The latter group represents regions already occupied by Oct4 in 2i conditions. Interestingly, enhanced H3K27Ac was observed in the Oct4 (up) group as cells exited from ground state pluripotency whereas little change was seen in the Oct4 (down) group (Figures 3G and 3I). As observed with the Otx2+/Oct4− group, further partitioning of the Otx2+/Oct4+(up) subcategory on the basis of fold changes in H3K27Ac levels, indicating that there are large subset of enhancers which show big increases in H3K27Ac, consistent with their activation and another subset that changes minimally (Figure S3F). Furthermore, increased FAIRE-seq signal and H3K4me1 was observed in the Oct4 (up) group whereas relatively little change was seen in the Oct4 (down) group (Figure S3G). Thus, where Otx2 binding coincides with enhanced Oct4 binding, the binding of Otx2 correlates with the acquisition of marks associated with active enhancers (i.e., de novo enhancer formation), whereas pre-existing Oct4 binding correlates with the retention of active enhancer marks (i.e., enhancer maintenance). To examine whether these two types of enhancer regions are associated with genes involved in distinct biological processes, we performed gene ontology analysis on genes associated with the Otx2+/Oct4+(up) and Otx2+/Oct4+(down) subcategories. A clear distinction in GO terms was observed with enhanced Oct4 binding being associated with the Wnt signaling pathway and neuronal development, whereas regions where Oct4 binding is either maintained or reduced are associated with stem cell maintenance and chromatin modification (Figure 3J).

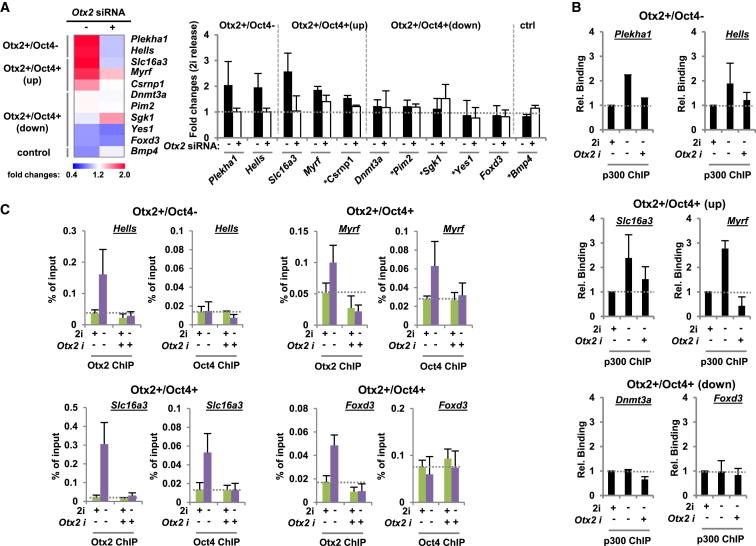

To establish whether Otx2 is required for enhancer activation, we depleted Otx2 and examined H3K27Ac levels at candidate loci representative of the Otx2+/Oct4+ and Otx2+/Oct4− binding regions. First, we investigated five loci where increases in H3K27Ac were observed following release from 2i and in all cases, these increases were reduced upon Otx2 depletion (Figure 4A). In contrast, at five other active enhancer regions where high levels of H3K27Ac were initially observed, no reductions in acetylation levels were observed following Otx2 depletion (Figure 4A). In all cases, Otx2 depletion caused a reduction in Otx2 ChIP signal as expected (Figures 4C and S4A–S4C). H3K27Ac is deposited by the p300 histone acetyltransferase (Pasini et al., 2010b). We detected p300 in Otx2 immunoprecipitates with mass spectrometry in four of five experiments (data not shown). We therefore asked whether Otx2 is required for p300 recruitment. Enhanced p300 binding is observed upon 2i withdrawal at regions exhibiting increased H3K27Ac levels such as the Plekha1 and Myrf loci but is unaffected at regions where acetylation levels remain stable (eg Foxd1 locus; Figure 4B). However, upon depletion of Otx2, reductions in p300 binding were seen at all loci where inducible p300 binding was observed (e.g., Plekha1 and Myrf loci) but little effect was seen where p300 binding was stably maintained. Thus, Otx2 is required for the inducible recruitment of p300.

Figure 4.

Otx2 Is Required for Enhanced H3K27Ac and Oct4 Cobinding at a Subset of Its Binding Regions

(A–C) ChIP-qPCR analysis of H3K27Ac levels (A), p300 binding (B), or Otx2 and Oct4 binding (C) to genomic regions associated with the indicated genes in mouse ESCs. Cells were maintained in 2i or cultured in the absence of 2i for 12 hr in the presence of siRNAs against Otx2 or control duplexes. Data in (A) are presented as a heatmap (left) or bar chart (right) and depict the fold change in H3K27Ac levels following release from culture in 2i in the presence or absence of siRNAs against Otx2. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 3 or n = 2 [indicated by ∗] in A and C and n = 2 in B).

See also Figure S4.

Next we examined whether Otx2 might also be required for the increased Oct4 binding observed at the Otx2+/Oct4+(up) regions. Consistent with this hypothesis, depletion of Otx2 reduced the Oct4 levels associated with several enhancer regions including those associated Myrf and Slc16a3 loci (Figure 4C). In contrast, the Oct4 ChIP signal at regions exhibiting little Oct4 binding or preassociated Oct4 in the ground state such as the Foxd3 and Dnmt3a loci (Figures 4C and S4B), were unaffected by Otx2 depletion.

Collectively, these data are consistent with a model whereby Otx2 associates with enhancer regions and at a subset of these is required for Oct4 binding and enhancer activation by p300 recruitment as mESCs transition from ground state pluripotency.

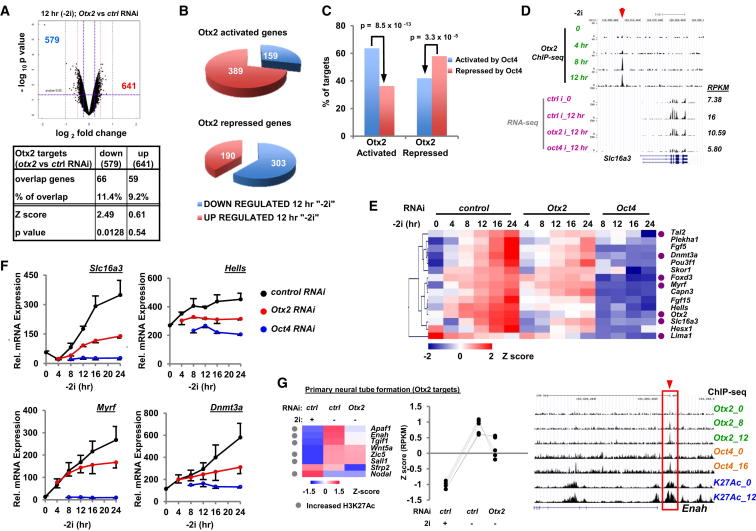

Coregulation of Target Gene Expression by Otx2 and Oct4

Having established that Otx2 and Oct4 commonly occupy many enhancer regions and that Otx2 contributes to their activation, we next wished to determine the regulatory outcomes in terms of target gene expression. First, we performed microarray and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis on mESCs treated with siRNAs against Otx2 or control duplexes, and then either maintained them in the pluripotent ground state or allowed them to exit by 2i withdrawal for 12 hr. More than 4,500 genes changed their expression over this period (Figure S5A). Importantly, > 500 genes were either up- or downregulated following Otx2 depletion 12 hr after release from 2i, and ∼10% of these genes are potential direct targets because they are associated with Otx2 binding regions (Figure 5A). Consistent with a role in exit from pluripotency, genes that were upregulated upon release from 2i, were predominantly downregulated by Otx2 depletion (ie activated by Otx2) and the reciprocal observed for genes that were downregulated upon release from 2i (Figures 5B and S5B). Next, we examined whether the Otx2 regulated genes are also potentially coregulated by Oct4 by comparing the Otx2 depletion data with RNA-seq data from mESCs depleted for Oct4 and released from ground state pluripotency. A statistically significant overlap was observed between genes either activated or repressed by both Otx2 and Oct4 (Figure 5C) and this association was maintained when the data were partitioned to examine their effects on genes whose expression changed during exit from pluripotency such as Slc16a3 (Figures S5C and 5D). To further substantiate these results, we examined the expression of a panel of genes over 24 hr following 2i withdrawal in the presence or absence of either Otx2 or Oct4 depletion. Genes exhibited expression profiles consistent with our RNA-seq analysis (Figures 5E, 5F, and S5D–S5G). Fifteen different direct Otx2 target genes exhibited robust upregulation following exit from pluripotency, and this increase was dampened upon Otx2 depletion and even more so by Oct4 depletion (Figures 5E, 5F, and S5D). These results are consistent with a coregulatory effect of Otx2 and Oct4 on gene expression. However, this was not a generic effect because other genes where Otx2 loss reduces their expression exhibited upregulation upon Oct4 depletion and vice versa, suggesting alternative roles for Otx2 and Oct4 in these contexts (Figures S5E–S5G).

Figure 5.

Otx2 and Oct4 Coregulate Target Gene Expression

(A) Volcano plot of microarray data showing gene expression changes in mESCs (Rex1GFPd2) cells 12 hr after “2i” withdrawal following Otx2 depletion or treatment with control siRNAs (top). The table depicts the intersection between expression microarray and Otx2 ChIP-seq data sets (bottom).

(B) Pie charts showing the proportion of genes up or downregulated upon withdrawal of 2i from ESCs for 12 hr, for subcategories of genes that are either activated (top) or repressed (bottom) by Otx2.

(C) Summary of gene expression changes affected by Otx2 and Oct4 depletion observed 12 hr after 2i release. p Values are calculated from a hypergeometric distribution.

(D) UCSC genome browser view of Otx2 binding profiles and RNA-seq tags associated with the Slc16a3 locus. Data are shown for the indicated times following release from 2i and for the RNA-seq data, treatment with control (ctrl) or the indicated RNAi (i) duplexes. RPKM values for each time point are shown on the right.

(E and F) Heatmap (E) and selected examples (F) of qRT-PCR analysis with the Fluidigm system of mRNA expression of the indicated genes over 24 hr following 2i withdrawal. Cells were treated with control, Otx2, or Oct4 siRNAs where indicated. Data in (E) are row Z score normalized and are presented in (F) as means ± SD (n ≥ 3). Genes associated with Oct4 binding regions are indicated by purple dots.

(G) Expression analysis of the genes in the “primary neural tube formation” gene ontology category that are direct targets of Otx2 and Oct4, either in 2i conditions or upon withdrawal from 2i for 12 hr in the presence of control (ctrl) or Otx2 siRNAs. Data are from RNA-seq analysis and are shown as a heatmap (row Z-normalized; left) and the individual profiles of the top six genes in the heatmap are shown graphically (middle). A UCSC genome browser view of the ChIP profiles across the Enah locus is shown on the right.

See also Figure S5.

Our GO term analysis indicated that genes in the “primary neural tube formation” category constituted one of the most significant terms associated with Otx2+/Oct4+ binding regions (Figure 3J). This was of interest because Otx2 has previously been implicated in controlling various aspects of neuronal differentiation (reviewed in Beby and Lamonerie, 2013). We therefore examined whether Otx2 might play a role in regulating the expression of these genes at this very early time point in the differentiation process. Interestingly, six of the Otx2 target genes in this category exhibited upregulation upon exit from the ESC state, and Otx2 depletion reduced the activation of three of these, Apaf1, Enah, and Tgif1 (Figure 5G). These three genes also exhibit evidence of increased coassociated H3K27Ac and hence enhancer activation (e.g., Enah; Figure 5G, right). Thus, Otx2 is implicated in specifying subsequent developmental processes at a very early stage.

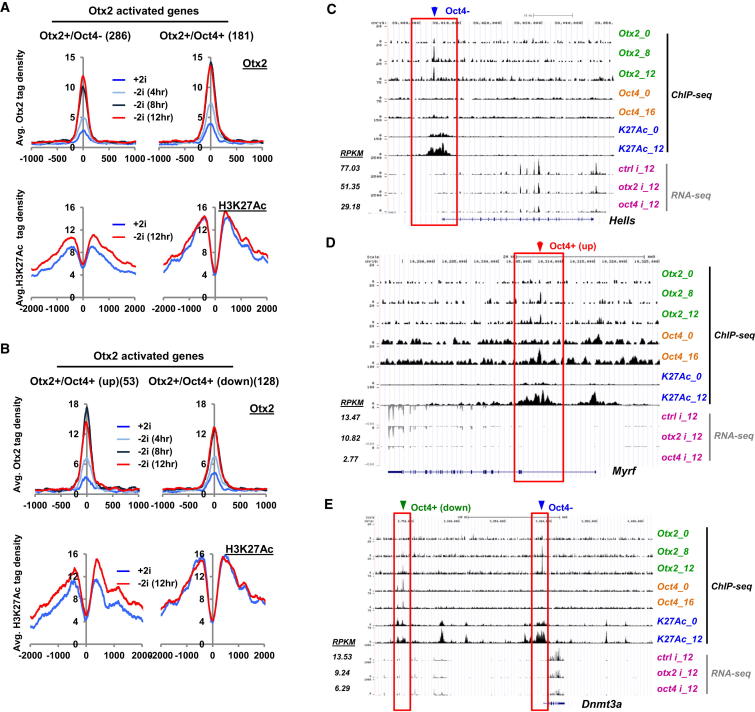

Next, we asked whether the changes we observed in enhancer activation correlated more generally with Otx2-mediated gene activation, and examined the changes in histone marks and chromatin structure at enhancer regions associated with genes showing upregulation during transition from naive pluripotency and dependency on Otx2 presence. Low initial levels of H3K27Ac were observed at enhancers bound by Otx2 alone (Otx2+/Oct4−), which subsequently increased as cells exited from pluripotency and is indicative of enhancer activation (Figures 6A and S6A). This is illustrated clearly in regions associated with the Hells and Dnmt3a loci (Figures 6C and 6E). This increase was not apparent at Otx2+/Oct4+ regions. However, increased levels of H3K4Me1 and FAIRE-seq signal were observed at both Otx2+/Oct4+ and Otx2+/Oct4− regions, suggestive of de novo enhancer production (Figure S6A). This was more apparent for the regions bound by Otx2 alone. When the Otx2+/Oct4+ regions were further partitioned according to either enhanced or decreased/no change in Oct4 binding upon exit from pluripotency, increased H3K27Ac was preferentially observed at enhancers exhibiting enhanced Oct4 binding (Otx2+/Oct4+ up; Figure 6B) such as the Myrf locus (Figure 6D) rather than where Oct4 binding is maintained (e.g., Dnmt3a locus; Figure 6E). These changes are indicative of enhancer activation, but only moderate increases in H3K4Me1 levels were observed (Figure S6B), suggesting that this represents activation of pre-established poised enhancers.

Figure 6.

Enhancer Activation Correlates with Otx2 Target Gene Activation

(A and B) Average tag density profiles showing indicated ChIP-seq data mapped onto the 2 or 4 kb regions surrounding the summits of Otx2 binding regions associated with Otx2 activated genes and from the Otx2+/Oct4− and Otx2+/Oct4+ subgroups (A) or associated with Otx2 binding regions showing increased (up) or decreased/no change (down) in Oct4 binding in the presence of 2i or for the indicated times following 2i withdrawal (B). Numbers in brackets represent the number of binding regions in each subgroup.

(C–E) UCSC genome browser views of Otx2, Oct4, and H3K27Ac binding profiles and RNA-seq signals associated with the Hells (C), Zfp42 (D), and Dnmt3a (E) loci. Otx2 binding regions are boxed. RPKM values for the RNA-seq data are shown adjacent to the relevant lanes.

See also Figure S6.

Collectively, these data therefore demonstrate that Otx2 is required for enhancer activation and associated target gene activation, and at a subset of these regions promotes the same regulatory events through stimulating Oct4 recruitment.

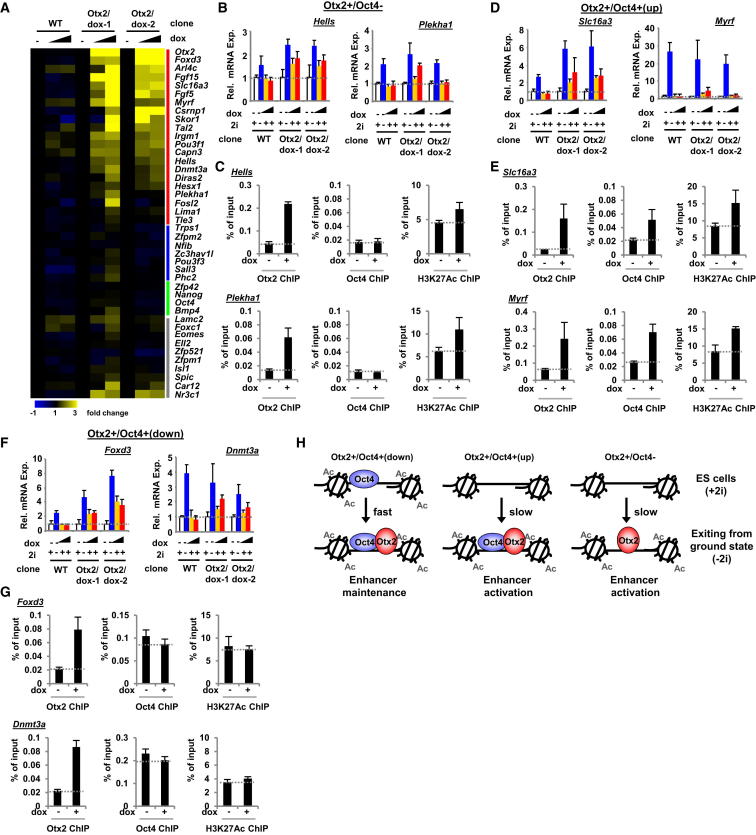

Otx2 Drives Enhances Activation, Oct4 Recruitment, and Target Gene Expression

To establish whether Otx2 plays a causative role in activating enhancers and associated gene expression, we induced Otx2 from a doxycycline-regulated expression cassette in cells maintained in the pluripotent ground state through culturing in 2i and asked if this was sufficient to drive downstream regulatory events. Importantly, we obtained Otx2 expression levels that are similar to those observed after 2i withdrawal (Figures S7A and S7B). First, we tested whether Otx2 could drive gene expression changes by testing a panel of its target genes. We were able to demonstrate that Otx2 was able to drive the expression of a large number of its target genes, despite the cells being held in the pluripotent state (Figure 7A). Importantly, this effect was largely limited to those genes identified as activated by Otx2 through our siRNA analysis (Figure 7A; genes bracketed by red bar). Otx2-driven transcription was observed on targets belonging to the Otx2+/Oct4− (Figure 7B) and the Otx2+/Oct4+ categories (Figures 7D and 7F). This was not a generic effect because Otx2 expression had little effect on other control genes and other Otx2 binding targets whose expression was not Otx2-dependent under normal differentiation conditions (Figures 7A and S7C). The levels of target gene expression were variable and did not attain the levels seen during exit from ground state pluripotency; however, this is not surprising given the fact that Otx2 likely collaborates with many other additional factors during ESC differentiation.

Figure 7.

Otx2 Drives Enhancer Activation, Oct4 Recruitment, and Target Gene Expression

(A–G) Heatmap (A) and selected examples (B, D, and F) of qRT-PCR analysis with the Fluidigm system of mRNA expression of the indicated genes in wild-type (Rex1GFPd2), mESCs and two clonally derived cell lines, Otx2/dox-1 and Otx2/dox-2, containing a doxycyclin-inducible Otx2 transgene. Cells were maintained in 2i media and either left untreated or treated with increasing concentrations (10 and 100 ng/ml) of doxycycline (dox) for 24 hr. Data in (A) are row Z score normalized and are presented in (B, D, and F) as means ± SEM (n = 3). The vertical color bars represent the following categories of genes based on siRNA depletion experiments; Otx2 upregulated (red), Otx2 downregulated (blue), control nontargets (green), and not regulated by Otx2 (gray). Gene expression following release from 2i for 12 hr is also shown in (B, D, and F). ChIP-qPCR analysis of H3K27Ac levels or Otx2 and Oct4 binding to genomic regions associated with the indicated genes in Otx2/dox-3 mESCs (C, E, and G). Cells were maintained in 2i either in the presence or absence of doxycycline (dox) treatment for 24 hr. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 3).

(H) Model illustrating the impact of Otx2 on enhancer activation during early stem cell commitment.

See also Figure S7.

Next, we examined whether Otx2 expression was sufficient to activate the enhancer regions associated with its regulated genes, and hence provide a more direct link between enhancer activation and transcriptional upregulation. First we tested binding regions where Otx2 either bound independently from Oct4 (Otx2+/Oct4−) or where it was required for Oct4 binding (Otx2+/Oct4+[up]) because these regions showed the characteristic of enhanced H3K27Ac during exit from ground state pluripotency (Figure 3). All of the tested regions showed evidence of Otx2-driven increases in K3K27Ac (Figures 7C and 7E). However, Otx2 was unable to drive increases in H3K27Ac at regions from the Otx2+/Oct4+(down), which we demonstrated to contain preactive enhancers whose H3K27Ac levels do not change during differentiation (Figure 7G). Moreover, we also tested Oct4 occupancy at the same loci and demonstrated that Otx2 is sufficient to drive enhanced Oct4 occupancy but only at regions from the Otx2+/Oct4+(up) category (Figures 7C, 7E, and 7G), which we demonstrated to exhibit Otx2-dependent increased Oct4 occupancy during normal differentiation (Figure 4C).

Together, these data demonstrate that Otx2 is sufficient to drive enhancer activation, and associated gene expression, and at a subset of regions, promotes Oct4 recruitment. Together with our loss-of-function analysis, these data demonstrate that Otx2 plays a significant role in driving these regulatory processes.

Discussion

Previous studies established that Otx2 plays an important role in the early stage of ESC differentiation (Acampora et al., 2013). Here we have revealed how Otx2 drives this process through collaboration with Oct4 and enhancer activation. Otx2 binds to hundreds of enhancer regions and these can be subcategorized into three broad types (Figure 7H). First, there are enhancers that are prebound by Oct4 in the ground state, show rapid Otx2 binding, and possess active enhancer marks that do not change upon Otx2 binding. This is consistent with a role in enhancer maintenance. Second, there are enhancers that show increased Otx2 occupancy, Otx2-dependent enhanced Oct4 occupancy, and enhanced histone activation marks. Third, there are enhancers that bind Otx2 in the absence of detectable Oct4 binding and are also characterized by increases in “active” chromatin marks. Importantly, the latter two types of enhancers exhibit Otx2-dependent activation marks but show slower Otx2 occupancy consistent with a role for prebound Oct4 in promoting more rapid Otx2 recruitment. At the apparent “Oct4”-independent sites, it is likely that Otx2 collaborates with as-yet unidentified prebound transcription factors or additional proteins that are induced as cells transition from pluripotency. Biologically, different enhancer subclasses are associated with genes involved in distinct biological processes, demonstrating that the mechanistic differences we uncover likely relate to distinct downstream events in the differentiation process. For example, enhancers bound by Otx2 in the absence of Oct4 are associated with genes involved in negative regulation of signaling, suggesting a role for Otx2 in rewiring the signaling networks as cells exit ground state pluripotency. For example, target genes Dusp6 and Spry4 in the GO term category “negative regulation of MAP kinase activity” might influence ERK pathway signaling, which plays an important role as cells initiate differentiation (Ying et al., 2008). Whereas Otx2 is involved in enhancer maintenance with Oct4, associated genes are involved in stem cell maintenance and chromatin organization. In contrast, when Otx2 and Oct4 come together to activate enhancers, the associated genes are involved in neural development and Wnt pathway signaling. This is consistent with the known role of Otx2 in neural development (Beby and Lamonerie, 2013) and suggests that this is initiated in collaboration with Oct4 at a very early stage.

We previously identified Oct4 as a candidate determinant of exit from ground state pluripotency (Yang et al., 2012). Here, we demonstrate an important role for Oct4 in collaboration with Otx2 in controlling the activity of genomic regulatory regions during the early stages of exit from ground state pluripotency. This complements other recent work that demonstrated that artificial manipulation of Oct4 levels can influence reprogramming and exit from pluripotency (Radzisheuskaya et al., 2013). Oct4 has been proposed to be important for promoting mesendodermal differentiation (Thomson et al., 2011) and part of this mechanism might be explained by switching binding partners from Sox2 to Sox17 (Aksoy et al., 2013). It is not clear whether partner switching occurs with an Otx2-related protein and this remains a possibility, but the de novo recruitment of Oct4 in an Otx2-dependent manner suggests the formation of new regulatory complexes, at least a subset of enhancers. It remains unclear as to how Otx2 promotes Oct4 recruitment because we have been unable to detect protein-protein interactions and no composite binding motifs are apparent. This suggests a more indirect recruitment mechanism, perhaps through enhancer opening and activation, because we generally find Otx2-dependent H3K27Ac coincident with enhanced Oct4 binding. It also remains possible that Oct4 recruitment contributes to these increases in enhancer activation. However, further studies are required to uncover the critical molecular events required for promoting Oct4 binding and its potential role in enhancer activation. We were unable to detect any other strongly over-represented binding motifs in the Otx2-bound regions that lacked Oct4 binding, suggesting that this is the most common combinatorial binding mode used by Otx2. However, a small proportion of regions contained Nanog binding motifs (Figure S1D), although co-occupancy appears unlikely given their mutually exclusive expression profiles. It is probable that Otx2 will collaborate with other heterologous transcription factors to activate enhancers and drive target gene activation. Indeed, this is likely to occur even at the Otx2+/Oct4+ regulatory elements and will provide enhancer-specific activities.

ESCs cultured in 2i conditions closely resemble the naive epiblast of the preimplantation mouse embryo (Boroviak et al., 2014). Transition from this ground state proceeds in a defined in vitro differentiation protocol upon simple withdrawal of the 2i inhibitors and consequent activation of the MEK/ERK pathway and GSK3 ensues. Oct4 expression remains relatively constant whereas Otx2 is robustly induced. This mirrors formation of the egg cylinder in the postimplantation embryo (Acampora et al., 2013). Indeed, it has recently been shown that Otx2 is required for efficient differentiation of ESCs in vitro and conversely that loss of Otx2 destabilizes the differentiated state. Our results therefore provide mechanistic insight into underlying this cell-fate transition.

In summary, we have identified Otx2 as a key player in driving the establishment of a gene regulatory landscape as mESCs transition from ground state pluripotency. Future studies will determine the molecular mechanisms that enable Otx2 and other factors to create this environment.

Experimental Procedures

Tissue Culture, RNA Interference, and RT-PCR

Mouse Rex1GFPd2 ESCs and the Otx2/dox1-3 derivatives (containing a doxycycline-inducible transgene; see the Supplemental Experimental Procedures for more details) were maintained as described previously in NDiff N2B27 media containing 2i inhibitors (CHIR99021 and PD0325901; Yang et al., 2012). Where indicated, cells were treated with the proteosome inhibitors, MG132 (1 μM) and clasto-lactacystin-β-lactone (1 and 10 μM), and doxycycline (100 ng/ml). RNAi was performed as described previously (Yang et al., 2012)

Real time qRT-PCR was carried out as described previously (O’Donnell et al. 2008). Data were normalized for the geometric mean expression of the control genes gapdh and ppia. Expression analysis using the Fluidigm BioMark HD system was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocols. In brief, RNA samples were reverse-transcribed into cDNA using Superscript III (Invitrogen). Specific target amplification using primers for the genes to be analyzed was performed to increase the number of copies of target cDNA, before analysis on the Fluidigm system. Prior to qPCR reactions, the specific target amplification reaction was treated with exonuclease I to eliminate the carryover of unincorporated primers. The primer-pairs used for RT-PCR are listed in Table S1.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blotting was carried out with the primary antibodies; Erk2 (137F5; Cell Signaling Technology, 4695), Otx2 (ProteinTech, 13497-1-AP), and Oct4 (Oct-3/4; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-8628). All experiments were carried out in 12-well plates. The lysates were directly harvested in 2× SDS sample buffer (100 mM TrisCl [pH 6.8], 4% SDS, 20% glycerol, 200 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.2% bromophenol blue) followed by sonication (Bioruptor, Diagenode). The proteins were detected using a LI-COR Odyssey Infrared Imager as described previously (Yang et al., 2012).

ChIP Assays

ChIP assays using Otx2 (ProteinTech., 13497-1-AP), Oct4 (Oct-3/4; Santa Cruz, sc-8628), p300 (Upstate, 05-257), H3K27Ac (Abcam, ab8895), and H3K4me1 (Abcam, ab4729) were performed essentially as described previously (Lee et al. 2006) with 1 μg antibodies and 1 × 106 ESCs for a transcription factor ChIP and 2.5 μg antibodies and 0.2 × 106 ESCs for a histone ChIP. Bound regions were detected by quantitative PCR with the Fluidigm system. Prior to loading onto the BioMark HD platform (Fluidigm), ChIP samples were preamplified for 10 cycles with 2× TaqMan PreAmp Master Mix (Applied BioSystems).

For re-ChIP assays, 3 × 106 cells were used with anti-Otx2 (first antibody) at 4°C overnight and continued as for the ChIP assay. After the 1× TE wash, immunoprecipitated complexes were twice eluted gently in 15 μl 10 mM dithiothreitol for 30 min at 37°C. Combined eluates were added to 1 ml IP buffer and incubated with the anti-Oct4 (second antibody) overnight at 4°C.

ChIP-Seq, FAIRE-Seq, and RNA-Seq Assays

ChIP for ChIP-seq assays was performed as described above except that we used 2.5 μg antibodies and 1.5 × 107 ESCs for a transcription factor ChIP and 10 μg antibodies and 0.75 × 107 ESCs for a histone ChIP. The ChIPed and input DNA libraries were generated and sequencing was performed on an Illumina GAIIx or Hi-seq genome analyzer according to the manufacturer’s protocols. FAIRE-seq assays were essentially performed as described previously (Simon et al. 2012) with 2 × 106 ESCs per condition. Libraries for RNA-seq were generated with a SENSE mRNA-seq library kit (Lexogen) and sequencing was performed on an Illumina GAIIx genome analyzer according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

Expression Microarray Analysis

mRNA was isolated and the labeling and expression profiling using Affymetrix arrays (genechip mouse genome 430 2.0 array) was performed as described previously (Boros et al. 2009). Duplicate experiments were performed in each condition.

Bioinformatics and Statistical Analysis

All software was run in default settings unless otherwise indicated. Sequences from the ChIP-seq (using 36 bp for Otx2, 50 bp for H3K4me1 and H3K27Ac), FAIRE-seq (using 100 bp), and RNA-seq (using 100 bp) were aligned against National Center for Biotechnology Information build 37/mm9 of mouse genome using Bowtie (Langmead et al. 2009), allowing up to two mismatches. Only reads that were uniquely mapped to the genome were preserved. The reads mapped to the mitochondrial genome were removed.

For ChIP-seq experiments, ChIP data were compared to input chromatin and peaks were called by MACS (version 1.4.1; Zhang et al. 2008) and Homer software (version 4.1; Heinz et al. 2010). The intersection (1 bp overlap) of called peaks was subsequently annotated using bedTools (version 2.17.0; Quinlan and Hall, 2010). Only peaks identified in both peak callers were retained for the further analysis. Motif discovery and the significance of discovered motifs was performed by Homer with the sequences within ± 100 bp around the binding region summits, with the default background setting; i.e., sequences randomly selected from the genome with the same GC content as the target sequences.

Nearest genes were assigned to peaks by Homer software and GREAT (McLean et al. 2010). For the gene ontology analyses, nearest genes were assigned by GREAT. For the expression analysis, genes were initially assigned by both Homer and GREAT. Due to the ambiguity of the annotation, the changes in gene expression upon Otx2 depletion were also considered in selecting the most likely of multiple options of gene-peak assignment. Genomic distributions were determined using Homer.

The peak overlaps between Otx2 and Oct4 ChIP-seq data sets were carried out with bedTools with a setting that at least 10% of reciprocal peaks intersect. The normalized tag density profiles were generated using annotatePeak.pl (Homer) and were plotted using Excel. Heatmaps of ChIP-seq data set were generated with Java treeview (Eisen et al. 1998) and heatmaps of expression data were generated by Multiexperiment Viewer (MeV 4_7_4; Saeed et al. 2003). For constructing networks, lists of gene names were uploaded into ingenuity pathway analysis software (Ingenuity Systems).

For microarray analysis, data were normalized with RMA and analyzed by limma (Partek Genomics Suite, Bioconductor; Smyth, 2004). Genes were taken as significantly up or downregulated with an expression change of at least 1.2-fold and a p value < 0.05. For RNA-seq analysis, data were analyzed using TopHat and Cufflinks as described previously (Trapnell et al., 2012) and genes were taken as significantly up or downregulated with an expression change (RPKM) of at least 1.5-fold.

The significance of overlaps between expression array and ChIP-seq data sets was calculated as described previously (Boros et al., 2009). The significance of differences between the genomic distributions of promoter-associated Otx2 binding regions was calculated using a Pearson’s chi-square test with Yates continuity correction, assuming an expected association of 1.1%.

Acknowledgments

We thank Karren Palmer for excellent technical assistance; Andy Hayes and Ian Donaldson in the Genomic Technologies and Bioinformatics facilities; Namshik Han and Aaron Webber for advice; and Nicoletta Bobola, Hilary Ashe, Xi Chen, and members of our laboratories for comments on the manuscript and stimulating discussions. This work was funded by the Wellcome Trust. A.S. is a Medical Research Council Professor.

Published: June 12, 2014

Footnotes

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/).

Supplemental Information includes Supplemental Experimental Procedures, seven figures, and one table and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2014.05.037.

Accession Numbers

The ArrayExpress accession numbers for the microarray, RNA-seq, FAIRE-seq, Otx2, H3K27Ac and H3K4me1, and Oct4 ChIP-seq data reported in this paper are E-MTAB-2239, E-MTAB-2245, E-MTAB-2283, E-MTAB-2281 and E-MTAB-2282, and E-MTAB-2490, respectively.

Supplemental Information

References

- Acampora D., Di Giovannantonio L.G., Simeone A. Otx2 is an intrinsic determinant of the embryonic stem cell state and is required for transition to a stable epiblast stem cell condition. Development. 2013;140:43–55. doi: 10.1242/dev.085290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aksoy I., Jauch R., Chen J., Dyla M., Divakar U., Bogu G.K., Teo R., Leng Ng C.K., Herath W., Lili S. Oct4 switches partnering from Sox2 to Sox17 to reinterpret the enhancer code and specify endoderm. EMBO J. 2013;32:938–953. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong L. Epigenetic control of embryonic stem cell differentiation. Stem Cell Rev. 2012;8:67–77. doi: 10.1007/s12015-011-9300-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beby F., Lamonerie T. The homeobox gene Otx2 in development and disease. Exp. Eye Res. 2013;111:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger M.F., Badis G., Gehrke A.R., Talukder S., Philippakis A.A., Peña-Castillo L., Alleyne T.M., Mnaimneh S., Botvinnik O.B., Chan E.T. Variation in homeodomain DNA binding revealed by high-resolution analysis of sequence preferences. Cell. 2008;133:1266–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betschinger J., Nichols J., Dietmann S., Corrin P.D., Paddison P.J., Smith A. Exit from pluripotency is gated by intracellular redistribution of the bHLH transcription factor Tfe3. Cell. 2013;153:335–347. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boros J., O’Donnell A., Donaldson I.J., Kasza A., Zeef L., Sharrocks A.D. Overlapping promoter targeting by Elk-1 and other divergent ETS-domain transcription factor family members. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:7368–7380. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boroviak T., Loos R., Bertone P., Smith A., Nichols J. The ability of inner-cell-mass cells to self-renew as embryonic stem cells is acquired following epiblast specification. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014;16:516–528. doi: 10.1038/ncb2965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatelain G., Fossat N., Brun G., Lamonerie T. Molecular dissection reveals decreased activity and not dominant negative effect in human OTX2 mutants. J. Mol. Med. 2006;84:604–615. doi: 10.1007/s00109-006-0048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creyghton M.P., Cheng A.W., Welstead G.G., Kooistra T., Carey B.W., Steine E.J., Hanna J., Lodato M.A., Frampton G.M., Sharp P.A. Histone H3K27ac separates active from poised enhancers and predicts developmental state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:21931–21936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016071107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies O.R., Lin C.Y., Radzisheuskaya A., Zhou X., Taube J., Blin G., Waterhouse A., Smith A.J., Lowell S. Tcf15 primes pluripotent cells for differentiation. Cell Rep. 2013;3:472–484. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen M.B., Spellman P.T., Brown P.O., Botstein D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford C.A., Ziller M.J., Gu H., Trapnell C., Donaghey J., Tsankov A., Shalek A.K., Kelley D.R., Shishkin A.A., Issner R. Transcriptional and epigenetic dynamics during specification of human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2013;153:1149–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz S., Benner C., Spann N., Bertolino E., Lin Y.C., Laslo P., Cheng J.X., Murre C., Singh H., Glass C.K. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol. Cell. 2010;38:576–589. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooistra S.M., van den Boom V., Thummer R.P., Johannes F., Wardenaar R., Tesson B.M., Veenhoff L.M., Fusetti F., O’Neill L.P., Turner B.M. Undifferentiated embryonic cell transcription factor 1 regulates ESC chromatin organization and gene expression. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1703–1714. doi: 10.1002/stem.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., Trapnell C., Pop M., Salzberg S.L. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T.I., Johnstone S.E., Young R.A. Chromatin immunoprecipitation and microarray-based analysis of protein location. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:729–748. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeb M., Dietmann S., Paramor M., Niwa H., Smith A. Genetic exploration of the exit from self-renewal using haploid embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:385–393. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martello G., Bertone P., Smith A. Identification of the missing pluripotency mediator downstream of leukaemia inhibitory factor. EMBO J. 2013;32:2561–2574. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean C.Y., Bristor D., Hiller M., Clarke S.L., Schaar B.T., Lowe C.B., Wenger A.M., Bejerano G. GREAT improves functional interpretation of cis-regulatory regions. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:495–501. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols J., Smith A. Pluripotency in the embryo and in culture. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012;4:a008128. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nord A.S., Blow M.J., Attanasio C., Akiyama J.A., Holt A., Hosseini R., Phouanenavong S., Plajzer-Frick I., Shoukry M., Afzal V. Rapid and pervasive changes in genome-wide enhancer usage during mammalian development. Cell. 2013;155:1521–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell A., Yang S.H., Sharrocks A.D. MAP kinase-mediated c-fos regulation relies on a histone acetylation relay switch. Mol. Cell. 2008;29:780–785. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasini D., Cloos P.A., Walfridsson J., Olsson L., Bukowski J.P., Johansen J.V., Bak M., Tommerup N., Rappsilber J., Helin K. JARID2 regulates binding of the Polycomb repressive complex 2 to target genes in ES cells. Nature. 2010;464:306–310. doi: 10.1038/nature08788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasini D., Malatesta M., Jung H.R., Walfridsson J., Willer A., Olsson L., Skotte J., Wutz A., Porse B., Jensen O.N., Helin K. Characterization of an antagonistic switch between histone H3 lysine 27 methylation and acetylation in the transcriptional regulation of Polycomb group target genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:4958–4969. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan A.R., Hall I.M. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:841–842. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radzisheuskaya A., Chia Gle.B., dos Santos R.L., Theunissen T.W., Castro L.F., Nichols J., Silva J.C. A defined Oct4 level governs cell state transitions of pluripotency entry and differentiation into all embryonic lineages. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013;15:579–590. doi: 10.1038/ncb2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed A.I., Sharov V., White J., Li J., Liang W., Bhagabati N., Braisted J., Klapa M., Currier T., Thiagarajan M. TM4: a free, open-source system for microarray data management and analysis. Biotechniques. 2003;34:374–378. doi: 10.2144/03342mt01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon J.M., Giresi P.G., Davis I.J., Lieb J.D. Using formaldehyde-assisted isolation of regulatory elements (FAIRE) to isolate active regulatory DNA. Nat. Protoc. 2012;7:256–267. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth G.K. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2004;3:e3. doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson M., Liu S.J., Zou L.N., Smith Z., Meissner A., Ramanathan S. Pluripotency factors in embryonic stem cells regulate differentiation into germ layers. Cell. 2011;145:875–889. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C., Roberts A., Goff L., Pertea G., Kim D., Kelley D.R., Pimentel H., Salzberg S.L., Rinn J.L., Pachter L. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat. Protoc. 2012;7:562–578. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray J., Kalkan T., Smith A.G. The ground state of pluripotency. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2010;38:1027–1032. doi: 10.1042/BST0381027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W., Schultz M.D., Lister R., Hou Z., Rajagopal N., Ray P., Whitaker J.W., Tian S., Hawkins R.D., Leung D. Epigenomic analysis of multilineage differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2013;153:1134–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S.H., Kalkan T., Morrisroe C., Smith A., Sharrocks A.D. A genome-wide RNAi screen reveals MAP kinase phosphatases as key ERK pathway regulators during embryonic stem cell differentiation. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1003112. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying Q.L., Wray J., Nichols J., Batlle-Morera L., Doble B., Woodgett J., Cohen P., Smith A. The ground state of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nature. 2008;453:519–523. doi: 10.1038/nature06968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young R.A. Control of the embryonic stem cell state. Cell. 2011;144:940–954. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaret K.S., Carroll J.S. Pioneer transcription factors: establishing competence for gene expression. Genes Dev. 2011;25:2227–2241. doi: 10.1101/gad.176826.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Liu T., Meyer C.A., Eeckhoute J., Johnson D.S., Bernstein B.E., Nusbaum C., Myers R.M., Brown M., Li W., Liu X.S. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS) Genome Biol. 2008;9:R137. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.