Abstract

Over the past two decades, new anti-immigration policies and laws have emerged to address the migration of undocumented immigrants. A systematic review of the literature was conducted to assess and understand how these immigration policies and laws may affect both access to health services and health outcomes among undocumented immigrants. Eight databases were used to conduct this review, which returned 325 papers that were assessed for validity based on specified inclusion criteria. Forty critically appraised articles were selected for analysis; thirty articles related to access to health services, and ten related to health outcomes. The articles showed a direct relationship between anti-immigration policies and their effects on access to health services. In addition, as a result of these policies, undocumented immigrants were impacted by mental health outcomes, including depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Action items were presented, including the promotion of cultural diversity training and the development of innovative strategies to support safety-net health care facilities serving vulnerable populations.

Keywords: Access to health services, Health outcomes, Health status, Anti-immigration policies and laws, Undocumented immigrants

Introduction

Due to vastly different living standards caused by large income disparities between developed and developing countries, people have been moving to more promising and developed regions throughout history [1–3]. We have seen signs of this phenomenon in the 1990s when Africans crossed the Sahara desert and climbed barbed wire fences in the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla in order to enter the European Union. During this time, the number of sub-Saharan undocumented immigrants to Europe started to rise, prompted by the rapidly changing political map of sub-Saharan Africa, which ultimately caused people to escape political instability and economic decline [4, 5].

Another important moment in the history of mass migration occurred in 1980 and in August 1994 in Communist Cuba. In 1980, the economic and political pressure placed on Cubans living in the island had reached a breaking point. In the midst of this distress, more than 10,000 Cubans flooded the Peruvian Embassy seeking asylum. The Cuban government responded by opening the port of Mariel to those wishing to leave the country while also taking advantage of the situation to “clean up” the Cuban penitentiary system by expelling hundreds of imprisoned homosexuals and other individuals with criminal records. As a result of this mass exodus, more than 125,000 Cuban refugees arrived in Miami in what became known as the “Mariel boatlift” [6, 7]. Again in August 1994, the Cuban balseros, or rafter crisis, occurred in which more than 35,000 people fled the island toward Florida in the span of a few weeks [8, 9].

Ironically, these two examples of the migration of Sub-Saharan Africans to Europe and Cubans to the US resulted in radically different responses from the receiving nations: Cubans were granted refugee status in the US, while Africans struggling with similar economic and political conditions did not receive the same treatment from European nations [10, 11]. Refugee status for Cubans allowed them greater access to health services in the US, which was not the case for undocumented Africans in the European Union. Together, these two cases point to the complexity of immigration laws and policies and how they relate to access to health services and health outcomes. In this paper, we consider this complexity and offer a critical analysis of immigration laws and policies and how they impact access to health services and health outcomes among undocumented immigrants and their families, an area of research which merits greater scholarly attention.

There are several factors that lead to the implementation of immigration policies aimed at curbing “illegal immigration,” including political, racial, terrorism, and economic factors. However, economic crisis and financial instability can lead governments to respond with stricter immigration laws, and oftentimes, undocumented immigrants are invoked as the scapegoats for these economic and financial crises. The world has gone through major financial crises before, including the Great Depression in 1929–1933, when the US lost one-third of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) [12, 13]. Similarly, Japan, which had a dynamic economy, was weakened considerably and ended up in stagnation for more than a decade starting in the 1980s [14]. Argentina’s economy shrunk by 20 % in 2001–2002, leading to a period of economic turmoil and instability plaguing the entire region of Latin America [15,16]. Interestingly, these global financial crises did not result in the implementation of harsher immigration policies. However, the current financial crisis across the globe has incentivized receiving nations to respond to waves of migration by targeting undocumented immigrants and illegal immigration through various laws and policies. The current global financial crisis has also led to the emergence of draconian immigration policies and laws that have had a tremendous impact on immigrants’ access to critical health services and health outcomes, including access to HIV and STI screenings and care. Understanding this impact in different countries will help develop appropriate solutions to address the wide range of health issues affecting undocumented immigrants. Our main objective is to advocate responsible positions on undocumented immigrants’ health and on immigration policy relating to health care for the benefit of the public, our patients, and the medical profession as a whole.

Undocumented Immigrants

Immigrant is a term used to describe foreign nationals who enter a country for purposes of permanent resettlement. In most countries, the immigration laws, including in the United States and Canada, do not classify “temporary workers” as immigrants. However, when temporary workers decide to settle permanently in their new nations, they are then reclassified as immigrants. In general, there are three broad categories of immigrants: (1) voluntary migrants who come to join relatives already settled in the receiving nation or to fill particular jobs for which expertise may be lacking among nationals; (2) refugees and asylum seekers who enter the country to avoid persecution; and (3) undocumented immigrants who enter the country illegally.

The term undocumented immigrant has been operationalized using certain factors: (1) legally entered the nation state or territory but remained in the country after their visa/permit expired; (2) received a negative decision on their refugee/asylee application but remained in the country; (3) experienced changes in their socioeconomic position and could not renew residence permit but remained in the country; (4) used fraudulent documentation to enter the country or territory; or (5) unlawfully entered the country or territory, including those who were smuggled.

In this systematic review, we focus on the third category of immigrants, undocumented immigrants, due to the vulnerability of this particular community and the existing research establishing health disparities among this group when compared to other subcategories of immigrants, including documented immigrants [17–19]. Undocumented immigrants originate from countries with long-term war or civil unrest, or in some cases they migrate for particular economic, cultural, social, and political reasons. Undocumented immigrants have often experienced multiple pre-and-post migration stressful events, including imprisonment, rape, ethnic cleansing, physical violence, economic distress, torture, and many others. These unique challenges make them prone to higher rates of morbidity and mortality [20–24].

Methods

A multiple streams (MS) model of policy process was used to conceptualize the policy process regarding immigration policies targeting undocumented immigrants. MS is a framework that explains how policies are made by national governments under conditions of ambiguity. It theorizes at the systemic level, and it incorporates an entire system or a separate decision as the unit of analysis. The MS model views the policy process as composed of three streams of actors and processes: a problem stream, consisting of problems and their proponents; a policy stream, containing a variety of policy solutions and their proponents; and a political stream, consisting of public officials and elections. These streams often operate independently except during windows of opportunities, when some or all of the streams may intersect and cause substantial policy change [25–27].

In addition, we designed and reported this systematic review according to the PRISMA statement which ensures the highest standard in systematic reviewing [28]. The PRISMA statement consists of an evidence-based checklist of 27 items and a four-phase flow diagram. The checklist includes items deemed essential for transparent reporting of a systematic review. Articles were critically appraised according to the methodology by O’Rourke [29] and Portney [30]. The articles were assessed for validity based on sampling bias by analyzing the subjects and inclusion criteria; internal validity was determined by analyzing the design and methods used in the study; reliability was assessed by analyzing the procedures used; and attrition bias by reviewing the data analysis sections, including qualitative and quantitative methods. Each article received a grade according to its ability to meet these criteria. Policy analysis manuscripts were further assessed based on the legal framework used to conduct the analysis.

Article Selection

The timeframe chosen was 1990–2012, as the results aimed to be as relevant as possible to the current global state of affairs regarding immigration policies and health status as well as health outcomes among undocumented immigrants. A total of eight databases were used to search relevant papers, including three legal and four health and medical databases (Pegaus-Columbia Law Library’s online catalog, CLIO Beta, LexisNexis, Westlaw, JAMA and Archives, MEDLINE, PsychINFO, PubMed).

Article abstracts were recommended for full-length initial review if the abstract subject pertained to immigration policies and access to health services and health outcomes, and met the following conditions: (1) mentioned the terms “undocumented immigrants”, “refugees”, “asylees”, “immigration laws”, “immigration policies”, “anti-immigration rhetoric”, “access to health care”, “health outcomes”, or “health disparities”; and (2) established association between immigration policies and access to health services or health outcomes. The authors selected the search terms based on a preliminary test search. The search was further refined by including the terms “methodology”, “outcome”, and “intervention”.

The authors excluded articles that did not feature a title or abstract. They also excluded articles that were book chapters, conference abstracts, had no listed authors, or were not available in English or Spanish. Articles that did not include undocumented immigrants in their analysis were excluded. In addition, articles that did not describe a research project or study were excluded. Articles were included for full-length final review if they fit the following criteria: (1) the immigrant population included was undocumented as opposed to documented immigrants; (2) access to health services and health outcomes were the primary focus of the study; (3) the study reported quantitative or qualitative results or rigorous policy analysis; and (5) articles were published in English or Spanish.

Results

Immigration Policies and Laws

Using the multiple streams (MS) model of policy process, we were able to deconstruct the framework that explains how immigration policies are made and implemented (Table 1). The passage of anti-immigration policies through the legislative, executive, and judicial branches, as exemplified in our review, was fueled in most cases by an anti-illegal immigration rhetoric that came about as a result of “economic and social problems” in the country. As shown by the cases of Australia [31], United States [17,32], Spain [33], and France [34] to mention a few, undocumented immigrants are being negatively perceived by many policymakers and powerful interest groups and scapegoated as causing domestic economic downturn. Our review also found that most of these anti-illegal immigration initiatives were proposed under a “policy” or “political” umbrella to attract voters in certain localities with strong “anti-immigration” sentiments.

Table 1.

Policy process

| Streams | Description |

|---|---|

| Problem stream |

Given the various conditions that exist regarding illegal migration, policy makers and political stakeholders define these as problems using a number of criteria such as statistics based on independent research determining that undocumented immigrants are not only a burden to the state but also to the federal governments or the existence of dramatic events or crises as a result of illegal migration, including refugee crises, existence of drug cartels, and border health and criminal history. |

| Policy stream |

Immigration policies are generated by various groups or stakeholders including think tanks, bureaucrats, congressional staff, politicians, and academics. Immigration policies are usually drafted by considering the level of technical and implementation feasibility as well as their acceptable value. As is the case with most strict immigration policies, they are usually effectively introduced in localities with high levels of anti-immigration sentiments. |

| Political stream |

The political consists of the “national mood” or the overall sentiment of a country or region that may change at any given time due to pressure from campaigns created by particular interest groups with a political agenda, and administrative or legislative turnover where new administrative staff is likely to create an environment of change regarding immigration policies. |

In addition, using the MS model led us to further understand how the sources of immigration enforcement power vary by country and jurisdiction. Countries use the judiciary, legislative, or executive branches to enforce these powers. Powers come through a complex body of statutes, rules, and case law governing entry into a particular country. However, there is a general consensus that immigration control is an exercise of the executive power; that is, it is exercised by the executive arm of the government. A unique characteristic encountered in the field of immigration law is the retention of discretion, which is less amenable to control than the application of specific rules and standards. A subjective approach is introduced with discretion and issues such as discrimination, bias, and prejudice might be present. Hence, the discretionary nature of immigration law is at the root of much of the criticism that has been directed against these laws.

In the United States, for example, one can easily see the intersection of the different branches of government as they each relate to immigration law. There are two sources of immigration powers in the United States: (1) the enumerated powers which are reflected through the Commerce Clause, Migration or Importation Clause, Naturalization Clause and the War Clause and (2) Implied Constitutional Powers. However, several states including Arizona, Alabama, Indiana, North Carolina, and others have recently tried to implement statewide immigration laws, even though Supreme Court precedents grant only the federal government the power to control immigration law. For well over a century, since Congress first passed comprehensive immigration legislation, it has been firmly established that the federal government has exclusive reign over immigration and nationality law. As the Court stated unequivocally in De Canas v. Bica (1976), “[p]ower to regulate immigration is unquestionably exclusively a federal power.” Therefore, the US government enforces immigration laws without interference from the states.

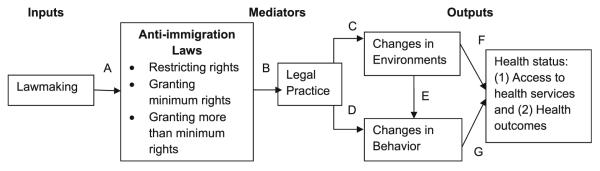

A casual diagram presenting how anti-immigration policies affect access to health services and health outcomes has also been developed as a result of the application of the MS methodology (Fig. 1). The way anti-immigration laws and policies influence health status is illustrated in this figure. In general, the independent variable will be an aspect of lawmaking (Path A) guided by any of the policy streams (i.e., problem, policy or political). Anti-immigration laws and policies are the outcome variables and political and other jurisdictional characteristics are often the key explanatory variables tested.

Fig. 1.

Influence of Anti-immigration Policies and Laws on Health Status

Path B and C examine key mediators in the causal chain linking anti-immigration laws and health. Laws and policies may vary considerably in the degree to which they are effectively implemented. Paths C and D involve studying the effect of law on environments and health behaviors. The term environment does not only refer to the physical environment, but also to social structures and institutions such as private and federally-funded health clinics and not-for-profits. Anti-immigration laws and their implementation affect social institutions and environments by increasing or decreasing available resources or expanding or reducing rights. Laws may affect health behaviors both directly (Path D) and by shifting the environmental conditions that make particular behavioral choices more or less attractive (Path C-E). Ultimately, changes in environments and behaviors lead to changes in health status (e.g., access to health services and heath outcomes) leading to changes in population-level morbidity and mortality.

Systematic Review

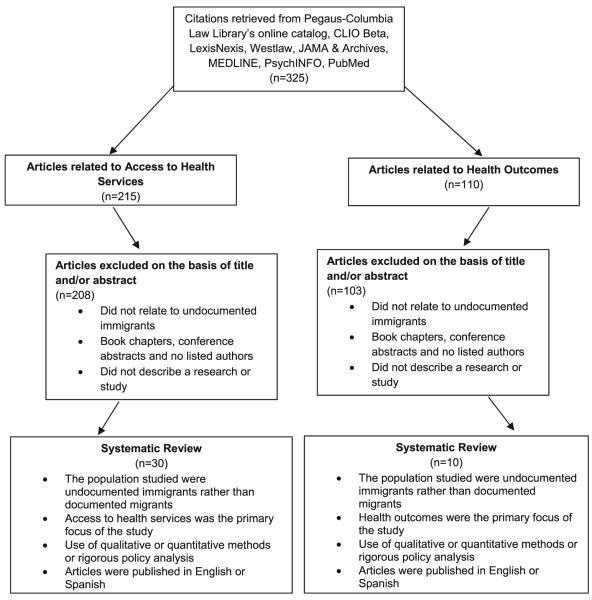

A search produced a total of 325 titles across the eight databases (Fig. 2). A total of 215 titles related to access to health services and 110 to health outcomes. The majority of the exclusions were based on either the fact that the population group in the study was not “undocumented” or the study did not include an actual “immigration policy or law.” A total of 40 peer-reviewed manuscripts and articles were selected for critical appraisal; 30 related to access to health services and 10 to health outcomes (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Search strategy and results

Table 2.

Summary of articles

| Authors | Year | Title | Journal | Study type | Country | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zambrana, R. E., Ell, K., Dorrington, C., Wachsman, L., and Hodge, D |

1994 | The relationship between psychosocial status of immigrant Latino mothers and use of emergency pediatric services. |

Health and social work | Policy analysis |

United States |

N/A |

| Asch, S., Leake, B., and Gelberg, L. | 1994 | Does fear of immigration authorities deter tuberculosis patients from seeking care? |

The Western Journal Of Medicine |

Quantitative | United States |

313 |

| Sorensen, W., Lopez, L., and Anderson, P. | 2001 | Latino AIDS Immigrants in the Western Gulf States: A Different Population and the Need for Innovative Prevention Strategies. |

Journal Of Health and Social Policy |

Policy analysis |

United States |

N/A |

| Berk, M., and Schur | 2001 | The effect of fear on access to care among undocumented Latino immigrants. |

Journal Of Immigrant Health |

Quantitative | United States |

973 |

| Hagan, J., Rodriguez, N., Capps, R., and Kabiri, N. | 2003 | The Effects of Recent Welfare and Immigration Reforms on Immigrants’ Access to Health Care. |

International Migration Review |

Quantitative | United States |

N/A |

| Manfellotto, D. | 2003 | Case study 5: From misinformation and ignorance to recognition and care: immigrants and homeless in Rome, Italy. |

Health Systems Confront Poverty |

Policy analysis |

Italy | N/A |

| Romero-Ortuño, R. | 2004 | Access to health care for illegal immigrants in the EU: should we be concerned?. |

European Journal Of Health Law |

Policy analysis |

European Union |

N/A |

| Davidovich, N., and Shvarts, S. | 2004 | Health and Hegemony: Preventive Medicine, Immigrants and the Israeli Melting Pot. |

Israel Studies | Policy analysis |

Israel | N/A |

| Limia Redondo, S., Alonso Blanco, C., and Salvadores Fuentes, P. |

2005 | The rights of immigrants to healthcare. | Metas De Enfermerá | Policy analysis |

Spain | N/A |

| Oxman-Martinez, J., Hanley, J., Lach, L., Khanlou, N., Weerasinghe, S., and Agnew, V. |

2005 | Intersection of Canadian policy parameters affecting women with precarious immigration status: a baseline for understanding barriers to health. |

Journal of Immigrant Health |

Policy analysi |

Canada | N/A |

| Oxman-Martinez, J., Hanley, J., Lach, L., Khanlou, N., Weerasinghe, S., and Agnew, V. |

2005 | Intersection of Canadian policy parameters affecting women with precarious immigration status: a baseline for understanding barriers to health |

Journal Of Immigrant Health |

Policy analysis |

Canada | N/A |

| McSherry, B., and Dastyari, A. | 2007 | Providing Mental Health Services and Psychiatric Care to Immigration Detainees: What Tort Law Requires. |

Psychiatry, Psychology and Law |

Policy analysis |

Australia | N/A |

| Moya, E., and Shedlin, M. | 2008 | Policies and laws affecting Mexican-origin immigrant access and utilization of substance abuse treatment: obstacles to recovery and immigrant health. |

Substance Use And Misuse |

Qualitative | United States- Mexico Border |

30 |

| Venters, H. D., McNeely, J., and Keller, A. S. | 2009 | HIV screening and care for immigration detainees | Health and Human Rights: An International Journal |

Policy analysis |

United States |

N/A |

| Oucho, O. J., and Ama, N. O. | 2009 | Immigrants’ and Refugees’ Unmet Reproductive Health Demands in Botswana: Perceptions of Public Health Providers. |

South African Family Practice |

Quantitative | Botswana | 851 |

| Okolec, J. E. | 2009 | Health Care for the Undocumented: Looking for a Rationale. |

Journal Of Poverty | Policy analysis |

United States |

N/A |

| Ducci, M., and Symmes, L. | 2010 | La pequeña Lima: Nueva cara y vitalidad para el centro de Santiago de Chile. |

Eure | Policy analysis |

Chile | N/A |

| Stead, K. | 2010 | Critical condition: using asylum law to contest forced medical repatriation of undocumented immigrants. |

Northwestern University Law Review |

Policy analysis |

United States |

N/A |

| Weiss, R. | 2011 | France: recent immigration-related developments affecting persons suffering from serious illnesses. |

HIV/AIDS Policy and Law Review/Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network |

Policy analysis |

France | N/A |

| Aponte-Rivera, V. R., and Dunlop, B. W. | 2011 | Public Health Consequences of State Immigration Laws. |

Southern Medical Journal |

Policy analysis |

United States |

N/A |

| da Lomba, S. | 2011 | Irregular migrants and the human right to health care: a case-study of health-care provision for irregular migrants in France and the UK. |

International Journal Of Law In Context |

Policy analysis |

France and the UK |

N/A |

| Aponte-Rivera, V. R., and Dunlop, B. W. | 2011 | Public Health Consequences of State Immigration Laws. |

Southern Medical Journal |

Policy analysis |

United States |

N/A |

| Martinez, O., Dodge, B., Reece, M., Schnarrs, P. W., Rhodes, S. D., Goncalves, G., and… Fortenberry, J. |

2011 | Sexual health and life experiences: voices from behaviourally bisexual Latino men in the Midwestern USA. |

Culture, Health and Sexuality |

Qualitative | United States |

25 |

| Chavez, L. | 2012 | Undocumented immigrants and their use of medical services in Orange County, California. |

Social Science and Medicine |

Quantitative | United States |

805 |

| Larchanché, S. | 2012 | Intangible obstacles: Health implications of stigmatization, structural violence, and fear among undocumented immigrants in France. |

Social Science and Medicine |

Ethnographic | France | N/A |

| Konczal, L., and Varga, L. | 2012 | Structural violence and compassionate compatriots: immigrant health care in South Florida. |

Ethnic and Racial Studies |

Qualitative | United States |

20 |

| Celone, M. | 2012 | Undocumented and unprotected: solutions for protecting the health of America’s undocumented Mexican migrant workers. |

Journal Of Contemporary Health Law and Policy |

Policy analysis |

United States |

N/A |

| Baker, D., and Chappelle, D. | 2012 | Health Status and Needs of Latino Dairy Farmworkers in Vermont. |

Journal Of Agromedicine |

Quantitative and qualitative |

United States |

120 |

| Hardy, L., Getrich, C., Quezada, J., Guay, A., Michalowski, R., and Henley, E. |

2012 | A Call for Further Research on the Impact of State- Level Immigration Policies on Public Health. |

American Journal Of Public Health |

Qualitative | United States |

60 |

| Berlinger, N., and Raghavan, R. | 2013 | The Ethics of Advocacy for Undocumented Patients. |

Hastings Center Report | Policy analysis |

United States |

N/A |

| Nickerson, A., Bryant, R. A., Brooks, R., Steel, Z., and Silove, D. |

2009 | Fear of Cultural Extinction and Psychopathology Among Mandaean Refugees: An Exploratory Path Analysis. |

CNS Neuroscience and Therapeutics |

Quantitative | Australia | 315 |

| Dettlaff, A.J., Vidal de Haymes, M., Velazquez, S., Mindell, R., Bruce, L. |

2009 | Emerging issues at the intersection of immigration and child welfare: results from a transnational research and policy forum. |

Child Welfare | Policy analysis |

United States |

N/A |

| Johnston, V. | 2009 | Australian asylum policies: have they violated the right to health of asylum seekers? |

Australian and New Zealand Journal Of Public Health |

Policy analysis |

Australia | N/A |

| Hacker, Karen, Jocelyn Chu, Carolyn Leung, Robert Marra, Alex Pirie, Mohamed Brahimi, Margaret English, Joshua Beckmann, Dolores Acevedo-Garcia, and Robert, P. Marlin |

2010 | The impact of Immigration and Customs Enforcement on immigrant health: Perceptions of immigrants in Everett, Massachusetts, USA. |

Social Science and Medicine |

Qualitative | United States |

52 |

| Androff, D. K., Ayon, C. C., Becerra, D. D., Gurrola, M. M., Salas, L. L., Krysik, J. J., and Segal, E. E. |

2011 | US immigration policy and immigrant children’s well-being: The impact of policy shifts. |

Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare |

Policy analysis |

United States |

N/A |

| Fountain C, Bearman P. | 2011 | Risk as Social Context: Immigration Policy and Autism in California. |

Sociological Forum | Quantitative | United States |

2,421,339 |

| Steel, Z., Liddell, B. J., Bateman-Steel, C. R., and Zwi, A. B. | 2011 | Global Protection and the Health Impact of Migration Interception. |

Plos Medicine | Policy Analysis |

Global | N/A |

| Steel, Z., Momartin, S., Silove, D., Coello, M., Aroche, J., and Tay, K. |

2011 | Two year psychosocial and mental health outcomes for refugees subjected to restrictive or supportive immigration policies. |

Social Science and Medicine |

Quantitative | Australia | 104 |

| Viruell-Fuentes, E.A.; Miranda, P.Y., and Abdulrahim, S. | 2012 | More than culture: Structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health. |

Social Science and Medicine |

Policy analysis |

United States |

N/A |

| Arbona C, Olvera N, Rodriguez N, Hagan J, Linares A, Wiesner M. |

2012 | Acculturative Stress among Documented and Undocumented Latino Immigrants in the United States. |

Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences |

Quantitative | United States |

261 |

| Law or Immigration Policy | Length | Results | Domains |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immigration Policies | N/A | This article focuses on consistent empirical evidence which has shown that lowincome Latino populations tend to underutilize health care services and do not have a usual source of care. There has been an increasing recognition of the need to collect data on the fastest growing segment of the US population. A major social problem is the welfare of young children, especially the plight of poor and minority children. Institutional barriers, such as high cost of medical care, lack of bilingual or bicultural personnel, discrimination, and immigration laws, have also contributed to low use or inappropriate use of health services. A complex set of social and psychological factors influence a mother’s decision to seek pediatric services, including work status of the mother, multiple symptoms in the child, marital status, culture, and emotional status. In addition, organizational or structural characteristics of the current health care delivery system present barriers to appropriate use of services for Latino women and children. Several studies have concluded that racism and discrimination are endemic in the delivery, administration, and planning of health care services. |

Access to health services |

| State law requiring health care professionals, laboratories, and governmental agencies to report all suspected and confirmed cases of tuberculosis in Los Angeles |

From April to September 1993 |

Most patients (71 %) sought care for symptoms rather than as a result of the efforts of public health personnel to screen high-risk groups or to trace contacts of infectious persons. At least 20 % of respondents lacked legal documents allowing them to reside in the United States. Few (6 %) feared that going to a physician might lead to trouble with immigration authorities. Those who did were almost 4 times as likely to delay seeking care for more than 2 months, a period of time likely to result in disease transmission. Patients potentially exposed an average of 10 domestic and workplace contacts during the course of the delay. Any legislation that increases undocumented immigrants’ fear that health care professionals will report them to immigration authorities may exacerbate the current tuberculosis epidemic. |

Access to health services |

| Immigration Policy | N/A | By weaving together immigration and AIDS epidemiological patterns, the impact of tightening immigration policy, and masked sexual behaviors, the authors express concern for a lack of communication with, and lack of health care access for, Latinos in the Western Gulf Coast. To combat this deficit, health care and social workers need to be aware of different social, cultural, and behavioral contexts in Latino populations. Policy makers should support efforts to provide health care workers with skills through appropriate language and cultural sensitivity workshops. |

Access to health services |

| California’s Proposition 187 | From October 1996 to July 1997 |

The study was found that 39 % of the undocumented immigrants expressed fear about receiving medical services because of undocumented status. Those reporting fear were likelier to report inability acquiring medical and dental care, prescription drugs, and eyeglasses. Hence it can be concluded that concern about immigration status decreases the likelihood of receiving care. |

Access to health service |

| Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act and the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act |

From 1997 to 1999 | The study presents findings of interviews with public agency officials, directors of community-based organizations, and members of 500 households during two research phases, 1997–1998 and 1998–1999. In the household sample, 20 % of US citizens and 30 % of legal permanent residents who reported having received Medicaid during the five years before they were interviewed also reported losing the coverage during the past year. Some lost coverage because of welfare reform restrictions on noncitizen eligibility or because of changes in income or household size, but many eligible immigrants also withdrew from Medicaid “voluntarily.” |

Access to health services |

| Immigration Policies | N/A | The article presents a case study of immigrants and homeless people in Rome, Italy. It stresses that the poor experience difficulties in accessing the social as well as public health networks. |

Access to health services |

| Immigration Policies | N/A | Evaluates the access to health care for illegal immigrants in the European Union (EU). Efforts of EU Member States to control illegal immigration; Need for national legislations and implementation practices to be upgraded in order to grant illegal immigrants effective access to health care; Declarations on the Human Rights laws; Limitations of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. |

Access to health services |

| Immigration Policy | N/A | Issues of prejudice, racial discrimination, and access to health services are part of this discourse. The state of Israel provides a unique case study for immigration and health issues, and this article focuses on Israeli health and immigration policy in the 1950’s. Health and illness are rare topics in studies relevant to the history of Israeli society. |

Access to health services |

| Immigration Law for Aliens | N/A | The paper presents a review of the laws governing immigration in our country from the time the first regulation in relation to this subject entered into effect in 1994—the so called “Immigration Law for Aliens”-which was rather simple in its contents, to the “Organic Law on Rights and Freedom of the Immigrants in Spain and their social integration”, published in January 2000, as well as the Deontological Code of Nursing in Spain. The aim of this paper is to attempt to ascertain the type of healthcare type that these immigrants have the right to receive, whether their rights should be the same as those immigrants who are legally living in Spain, and what the Deontological Nursing Code with regards to immigrant patients establishes in relation to immigrant patients. |

Access to health services |

| Federal Immigration Policy | N/A | Federal immigration and health policies create direct barriers to health through regulation of immigrants’ access to services as well as unintended secondary barriers. |

Access to health services |

| 2001 Immigration and Refugee Protection Act |

N/A | Federal immigration and health policies create direct barriers to health through regulation of immigrants’ access to services as well as unintended secondary barriers. These direct and secondary policy barriers intersect with each other and with socio-cultural barriers arising from the migrant’s socio-economic and ethno-cultural background to undermine equitable access to health for immigrant women living in Canada. |

Access to health services |

| Immigration Policy | NA | In S v Secretary, Department of Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs [2005] FCA 549, Justice Paul Finn held that the Commonwealth had breached its duty to ensure that reasonable care was taken of two Iranian detainees, ‘S’ and ‘M’, in relation to the treatment of their respective mental health problems. The lack of proper psychiatric care at Baxter Detention Centre was also highlighted in the Palmer Inquiry into the detention of Cornelia Rau. This article analyses the Commonwealth Government’s legal duty to provide adequate levels of mental health services and psychiatric care to immigration detainees as well as the implications of the cases brought on behalf of a child refugee, Shayan Badraie and an Iranian man, Parvis Yousefi against the Department of Immigration and Citizenship and the detention centre operators. |

Access to health services |

| Immigration Policy | 2007 | Qualitative, semi-structured interviews were implemented to assess the dynamic social and economic factors that affect the delivery and utilization of treatment services, with emphasis on the impact of recent immigration-related laws and policies. The research provides initial data for evidence-based intervention and reinforces the need for culturally and gender appropriate treatment services for poor immigrants and their families. |

Access to health services |

| Immigration Policies | N/A | The authors conclude that the system of immigration detention in the US fails to adequately screen detainees for HIV and delivers a substandard level of medical care to those with HIV. |

Access to health services |

| Immigration Policies | N/A | Majority of the health providers indicated that the most important reproductive health needs of the immigrants and refugees, namely, pregnancy related (Prenatal, Obstetrics, Postnatal conditions), STI treatment, HIV/AIDS treatment and counseling, and family planning were not different from those of the locals. However, some major differences noted between the local population and the foreigners were (1) that ARV treatments and PMTCT were never accessible to the non-citizens; (2) that while treatments and other health services were free to Batswana (citizens of Botswana), a fee was charged to non-citizens. The major reasons for inability to access these services were: (1) The immigrants and refugees have to pay higher fees to access the reproductive health services (2) Once an immigrant or refugee is identified as HIV positive, there are no further follow-ups on the patient such as detecting the immune status using CD4 count or testing the viral load (3) The immigrants and refugees do not have referral rights to referral clinics/hospitals for follow-ups in case of certain health conditions (4) The immigrants and refugees are required to enlist in the Medical Aids scheme which can help offset part of the costs for the desired services. |

Access to health services |

| Immigration Policy | N/A | The plight of the undocumented in the United States elicits strong feelings on both sides of the debate. One viewpoint takes a strict immigration policy perspective and opposes the ability of the undocumented to access publicly financed programs and services including access to healthcare. Without the sanction of law, those taking a more flexible view must find persuasive arguments to permit the access to public services. The choice of arguments includes reframing the concept of citizenship; accepting the premise of basic human needs that invokes a human rights perspective and concerns about social justice; developing an ethic of care; or invoking a “common good” perspective that acknowledges the role of public health. |

Access to health services |

| Immigration Policy | N/A | The recent migrations to Chile are an unprecedented social phenomenon in the country. This work focuses on the impact of Peruvian migrants, as the major migrant group in Santiago’s downtown, and their recovery of semi-abandoned places and shops, creating a “Little Lima”. This is an area where migrants look for work, eat and enjoy themselves. The study reveals the positive effects of this phenomenon in the recovery and revitalization of central areas, and in reinvigorating trade and the use of public spaces. It also recognizes the precarious nature of migrant dwelling in older housing in the center, which creates problems of overcrowding, and access to health and education, which—given the absence of social policies aimed at immigration—can (and is starting to) create short-term conflicts. |

Access to health services |

| Asylum Policies | N/A | The article explores the use of asylum law to contest forced medical repatriation of undocumented immigrants. |

Access to health services |

| Immigration Law of 2011 | N/A | France enacted a new immigration law on 16 June 2011. Among other things, the law changes the criteria for issuing residence permits on medical grounds. Foreigners with a medical condition who apply for a residence permit must now show that treatment and care are unavailable in their country of origin. It is no longer sufficient to show a lack of effective access to such treatment or care. |

Access to health services |

| Illegal Immigration Reform and Enforcement Act of 2011 |

N/A | They argue that the Illegal Immigration Reform and Enforcement Act of 2011 adopted by Georgia has a potential effect on the overall health of the public and immigrants. The authors comment that the enforcement of the law can harm the public health in various ways including reduction in the prevention of illnesses, relocation of illegal immigrants, and increase of illegal healthcare services. |

Access to health services |

| Immigration Policy | N/A | With this in mind, this article considers the significance of a human rights approach to access to health care and undertakes a comparative study of health-care provision for irregular migrants in France and the UK. Irregular migrants are ineligible for national membership because they have breached immigration laws. Consequently their right to health care may only arise from international human rights law. This comparative study, however, shows that states resist the idea of a right to health care for people they regard as a threat to national sovereignty. Yet the author posits that the exercise of the government’s immigration power may be reconciled with the realisation of irregular migrants’ human right to health care. |

Access to health services |

| Illegal Immigration Reform and Enforcement Act of 2011 |

N/A | The authors reflect on the impact of the state immigration laws to public health in the US They argue that the Illegal Immigration Reform and Enforcement Act of 2011 adopted by Georgia has a potential effect on the overall health of the public and immigrants. The authors comment that the enforcement of the law can harm the public health in various ways including reduction in the prevention of illnesses, relocation of illegal immigrants, and increase of illegal healthcare services. |

Access to health services |

| Indiana Senate Bill 590 | From May 2010 to January 2011 | Men described their unique migration experiences as behaviourally bisexual men in this area of the USA, as well as related sexual risk behaviours and health concerns. Lack of culturally congruent public health and community resources for behaviourally bisexual men in the Midwestern USA were identified as significant barriers. As in other studies, familial and community relationships were significant for the participants, especially in terms of the decision to disclose or not disclose their bisexuality. Additionally, alcohol and other drugs were often used while engaging in sexual behaviours particularly with male and transgender, as well as female, partners. |

Access to health services |

| US Immigration Policies | From January 4 to January 30, 2006. | Findings show that undocumented immigrants had relatively low incomes and were less likely to have medical insurance; experience a number of stresses in their lives; and underutilize medical services when compared to legal immigrants and citizens. Predictors of use of medical services are found to include undocumented immigration status, medical insurance, education, and gender. Undocumented Latinos were found to use medical services less than legal immigrants and citizens, and to rely more on clinic-based care when they do seek medical services. |

Acces to health services |

| Finance Act of 2011 | From March 2007 to July 2008 | The paper analyzes how interaction among intangible factors— namely social stigmatization, precarious living conditions, and the climate of fear and suspicion generated by increasingly restrictive immigration policies—hinders undocumented immigrants’ access to health care rights and, furthermore, minimizes immigrants’ sense of entitlement to such rights in this European context. Intangible factors such as fear and suspicion have powerful “subjectivation” effects, which influence how both undocumented immigrants and their interlocutors (i.e., healthcare providers) think about “deservingness.” Medical anthropology is in a unique position to demonstrate and theorize these factors and effects, which inform contemporary debates about migration and “health ethics.” |

Access to health services |

| Immigration Policy | From 2009 to 2010 | Immigrants in South Florida often avoid primary health care even when offered freely and legally. This is because of bewilderment about bureaucratic requirements, fear of deportation and bills, and cultural folkways. |

Access to health services |

| Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) of 1986 and Case law |

N/A | Specifically, this Comment explores the implementation of the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) of 1986 and case law that has had a profound effect on the interpretation of the interaction between federal immigration laws and benefits for undocumented immigrants. This Comment discusses the social, health, and economic impacts that affect the United States when undocumented immigrants are precluded from receiving health care. |

Access to health services |

| Immigration Policies | 2012 | The study found, similar to other studies, the majority of workers were young, male Mexicans. However, the workers in this study, as compared toothers, originated farther south in Mexico and there were significant regional differences in educational attainment. Workers defined health in terms of their ability to work and the majority believed themselves to be in good health. The majority felt that moving to the United States has not changed their health status. The most common health issue reported was back/neck pain, followed by dental and mental health issues. Workers are both physically and linguistically isolated and reported isolation as the most challenging aspect of dairy farm work. Fear of immigration law enforcement was the primary barrier to care. |

Access to health services |

| Law Enforcement and Safe Neighborhoods Act, |

From May 2010 to June 2010 | Findings from the study suggest that the law changed health-seeking behaviors of residents of a predominantly Latino neighborhood by increasing fear, limiting residents’ mobility, and diminishing trust of officials. These changes could exacerbate barriers to healthy living, limit access to care, and affect the overall safety of the neighborhood. |

Access to health services |

| Immigration Policy | N/A | Providing health care to these residents is an everyday concern for the clinicians and health care organizations who serve them. Uncertain how to proceed in the face of severe financial constraints, clinicians may improvise remedies-a strategy that allows our society to avoid confronting the clinical and organizational implications of public policy gaps. There is no simple solution-no quick fix-that will work across organizations (in particular, hospitals with emergency departments) in states with different concentrations of undocumented immigrants, varying public and private resources for safety-net health care, and differing approaches to law and policy concerning the rights of immigrants. However, every hospital can help its clinicians by addressing access to health care for undocumented immigrants as an ethical issue. |

Access to health services |

| Australia’s immigration policies. | 2006–2007 | Results indicated that trauma and living difficulties impacted indirectly on fear of cultural extinction, while PTSD (and not depression) directly predicted levels of anxiety about the Mandaean culture ceasing to exist. The current findings indicate that past trauma and symptoms of posttraumatic stress contribute to fear of cultural extinction. Exposure to human rights violations enacted on the basis of religion has significant mental health consequences that extend beyond PTSD. The relationship between perception of threat, PTSD, and fear of cultural extinction is considered in the context of cognitive models of traumatic stress. |

Health outcomes |

| US Immigration Policies | N/A | In July 2006, the American Humane Association and the Loyola University Chicago School of Social Work facilitated a roundtable to address the emerging issue of immigration and its intersection with child welfare systems. More than 70 participants from 10 states and Mexico joined the roundtable, representing the fields of higher education, child welfare, international immigration, legal practice, and others. This roundtable created a transnational opportunity to discuss the emerging impact of migration on child welfare services in the United States and formed the basis of a continued multidisciplinary collaboration designed to inform and impact policy and practice at the local, state, and national levels. This paper presents the results of the roundtable discussion and summarizes the emerging issues that participants identified as requiring attention by child welfare systems to facilitate positive outcomes of child safety, permanency, and well-being. |

Health outcomes |

| Asylum Policies | N/A | Findings reveal that Australian asylum policies of detention, temporary protection and the exclusion of some asylum seekers from Medicare rights have been associated with adverse mental health outcomes for this population. This is attributable to the impact of these policies on accessing health care and the underlying determinants of health for aslyum seekers. |

Health outcomes |

| Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996, and the creation of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) |

N/A | Documented and undocumented immigrants reported high levels of stress due to deportation fear, which affected their emotional wellbeing and their access to health services. |

Health outcomes |

| Immigration Policies | N/A | Immigrant children face many problems, including economic insecurity, barriers to education, poor health outcomes, the arrest and deportation of family members, discrimination, and trauma and harm to their communities. These areas of immigrant children’s economic and material well-being are examined in light of restrictive and punitive immigration policies at the federal and local level. |

Health outcomes |

| Proposition 187 | N/A | Using a population-level data set of 1992–2003 California births linked to 1992–2006 autism case records, the authors show that the effects of state and federal policies toward immigrants are visible in the rise and fall of autism risk over time. The common epidemiological practice of estimating risk on pooled samples is thereby shown to obscure patterns and mis-estimate effect sizes. Finally, we illustrate how spatial variation in Hispanic autism rates reflects differential vulnerability to these policies. This study reveals not only the spillover effects of immigration policy on children’s health, but also the hazards of treating individual attributes like ethnicity as risk factors without regard to the social and political environments that give them salience. |

Health outcomes |

| Immigration Policies | N/A | The article explores the international immigration policy, highlighting the impact of immigration interception practices on public health. It examines the interception strategies used by states to prevent movement of irregular migrants, particularly the immigration detention and visa restrictions, which are inferred to pose serious threat to migrants’ health and welfare. The humanitarian outcomes promoted by interception practices are discussed. |

Health outcomes |

| Mandatory Detention Provision | 2003–2004 | The results indicated that TPVs had higher baseline scores than PPVs on the HTQ PTSD scale, the HSCL scales, and the GHQ. ANCOVA models adjusting for baseline symptom scores indicated an increase in anxiety, depression and overall distress for TPVs whereas PPVs showed improvement over time. PTSD remained high at follow-up for TPVs and low amongst PPVs with no significant change over time. The TPVs showed a significant increase in worry at follow-up. TPVs showed no improvement in their English language skills and became increasingly socially withdrawn whereas PPVs exhibited substantial language improvements and became more socially engaged. TPV holders also reported persistently higher levels of distress in relation to a wide range of post-migration living difficulties whereas PPVs reported few problems in meeting these resettlement challenges. The data suggest a pattern of growing mental distress, ongoing resettlement difficulties, social isolation, and difficulty in the acculturation process amongst refugees subject to restrictive immigration policies. |

Health outcomes |

| US Immigration Policies | N/A | In this paper, the authors highlight the shortcomings of cultural explanations as currently employed in the health literature, and argue for a shift from individual culture-based frameworks, to perspectives that address how multiple dimensions of inequality intersect to impact health outcomes. Based on the review of the literature, the authors suggest specific lines of inquiry regarding immigrants’ experiences with day-to-day discrimination, as well as on the roles that place and immigration policies play in shaping immigrant health outcomes. The paper concludes with suggestions for integrating intersectionality theory in future research on immigrant health. |

Health outcomes |

| Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act |

N/A | Undocumented immigrants reported higher levels of the immigration challenges of separation from family, traditionality, and language difficulties than documented immigrants. Both groups reported similar levels of fear of deportation. Results also indicated that the immigration challenges and undocumented status were uniquely associated with extrafamilial acculturative stress but not with intrafamilial acculturative stress. Only fear of deportation emerged as a unique predictor of both extrafamililal and intrafamilial acculturative stress. |

Health outcomes |

Access to Health Services

In terms of access to health services, a total of 215 articles were identified and met the inclusion criteria for the initial review. The authors identified thirty critically appraised articles to be included in this review. Researchers and think tanks have used a wide range of methodologies to assess the relationship between immigration policies and access to health services among undocumented immigrants. Mixed-methods approaches have been used with the inclusion of both qualitative and quantitative approaches [35, 36]. However, the use of focus groups and quantitative questionnaires to measure perceived discrimination and access to health services—along with the critical understanding of immigration laws through legislative reviews—seem to be the most appropriate mixed-method approach used [37, 38].

Immigration laws and policies explicitly provide or restrict access to health services. Three categories were identified regarding access to health services: (1) laws and policies restricting rights to access health services, (2) laws and policies granting minimum rights to health services, and (3) laws and policies granting more than minimum rights to health services. Several laws prohibited or restricted immigrants from accessing basic health services, including emergency care. In particular, these policies explicitly stated that undocumented immigrants could not seek health services or contained clauses that prevented them from seeking health services and mandated professionals to report documentation status. Hence, being “undocumented” was used as a means of exclusion from vital services (e.g., HIV and STI services, prenatal care services) provided by governmental agencies or non-profit organizations receiving government funding [37, 39].

Some jurisdictions only provided health care to undocumented immigrants in detention centers [40–42]. Other countries have explicit laws and policies in which undocumented immigrants are entitled only to emergency care or care specified in terms such as “immediate or urgent” [43]. However, in many cases, even though these services were available to undocumented immigrants, they were hesitant to go to health centers or to receive emergency care due to potential retaliation and fear of deportation. A few countries had laws and policies that entitled undocumented immigrants access to health care beyond emergency care, in particular primary and secondary care [44]. However, this entitlement often involved administrative procedures, including the completion of applications and forms, that when put into practice, impaired access to care to a certain extent.

Perceived fear of deportation and harassment from authorities correlated to lack of access to a wider range of health services. Immigrants perceived these policies as a threat not only to them but also to their families and as sources of criminalization. In addition, in countries with explicit laws prohibiting undocumented immigrants from access to health services, we found that institutions such as law enforcement agencies and health care establishments discriminated against undocumented immigrants. In this way, undocumented immigrants not only feared deportation but also felt discriminated against and harassed by other governmental and non-governmental institutions. In particular, police checkpoints and immigration raids perpetuated the fear of and isolation from health services [38].

It is important to note the clear association between immigration policies and access to HIV services and care coordination services for HIV-positive, undocumented immigrants, including LGBT individuals. Timely entry into HIV care is critical for early initiation of therapy, immunological recovery, and improving chances of survival. However, undocumented Latinos are more likely to enter HIV care late in the disease course. Receiving a diagnosis of AIDS coupled with the presence of anti-immigration policies serve as major barriers to accessing adequate care. Participants not only felt threatened by anti-immigration policies and felt that they prevented them from accessing HIV services, but they also felt that the general lack of health care accessibility and bureaucratic requirements served as barriers to receiving care [38, 45].

In California, where there has been a long-established pattern of migration from China, Mexico, and Central America, a more profound relationship between immigration policies and access to health services has been established. Several California immigration and health department policies were implemented during the 1990s to criminalize undocumented immigrants and prevent their use of health services, including HIV and STI screening services [17]. From a historical perspective, these policies seem to have had a profound impact on the current undocumented immigrant population in California. Undocumented immigrants in that state underutilize medical services when compared to legal immigrants and citizens; the main predictor of utilization of medical services is undocumented immigration status [17]. Recently, we have seen other states in the United States following the same path taken by California in the 1990s, including Indiana and North Carolina, where undocumented immigrants are prevented from using vital health services such as HIV screening and prenatal care by creating barriers including scrutiny of asking for documentation before accessing health services and the use of police checkpoints in front of health departments [38].

Other nations have adopted extreme mandatory detention policies, such as the one implemented in Australia in 1992, where detention is not predicated on merit-based assessments (such as the likelihood of absconding or suspected criminal intent) but follows automatically from the mode of arrival [46]. Detainees are generally denied the right to appeal to an independent judicial body or tribunal to challenge their detention. These particular detention policies have caused a tremendous fear among undocumented immigrants and increased persecution and prosecution of vulnerable populations, creating a major barrier to accessing health services. In addition, studies have documented that when these detention policies are enforced, even access to basic HIV medication and care are denied [47] .

The presence of anti-immigration rhetoric also impacted health providers’ attitudes and behaviors towards serving the health needs of undocumented immigrants. Some providers, in localities where these anti-immigration policies were implemented, discriminated against undocumented immigrants by denying services and saw them as the “other,” serving this as another critical barrier to access to care. Institutional prejudice and discrimination as well as cultural differences were also reported by undocumented immigrants deterring them from seeking and receiving needed services [34, 38].

Most of the studies looking at the effect of immigration policies on access to health services seem to have been conducted in developed nations with the resources and infrastructure available to carry out this type of empirical research. However, as new migration patterns and trends are being seen from developing nations to new emerging developed countries such as Brazil, India, and China, more research is needed in these countries to better understand the relationship between immigration policies and access to health services. In addition, health professionals and politicians need to work with these newly developed nations to develop resources and healthcare infrastructure in order to address and respond to the unique needs and challenges of undocumented immigrants.

Health Outcomes

In terms of health outcomes, a total of 110 articles were identified for the initial review and the authors selected ten critically appraised, peer-reviewed manuscripts for review. Immigration policies and migration interception practices implemented by receiving nations are a major global determinant of health. In particular, such policies and practices have a tremendous effect on mental health outcomes among undocumented immigrants, refugees, and vulnerable immigrants, including sex workers and LGBT individuals.

The majority of the studies established a clear association between immigration policies and mental health outcomes such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [48]. For example, a clear correlation was shown to exist between conditions in immigration detention centers and increased anxiety, depression, and overall stress [31, 49]. Screening instruments used to measure depression also found that undocumented immigrants are at highest risk of depressive symptoms and are disproportionately impacted by PTSD, anxiety, and depression when compared to other documented immigrants and citizens [49]. In particular, in localities and jurisdictions with anti-immigration policies, the prevalence of negative mental health outcomes is even higher when compared to locations and jurisdictions in the same country with neutral or welcoming policies towards immigrants, including “sanctuary cities.”

Mental health concerns including depression, anxiety, and PTSD were not only identified among adult undocumented immigrants, but also among undocumented children [49–51]. Undocumented children experience significant trauma, and studies particularly point to the development of symptoms of PTSD among this affected group [51]. In addition, undocumented children faced unique challenges including barriers to education along with anxiety over arrest, incarceration, and imprisonment of family members due to immigration status, leading to increased child trauma and harm [52]. In addition to mental health outcomes, a population-level data set from California birth records from 1992–2003 compared to 1992–2006 autism case records shows that the effects of state and federal policies toward immigrants are related to the rise and fall of autism risk over time [53]. However, it is also important to note the limited research and epidemiological data establishing the association between immigration policies and physical health outcomes such as autism, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, low birth weight, and prematurity. Further longitudinal research is needed to further establish these connections.

Not only were immigration policies identified as factors affecting the health outcome of immigrants, but also other social determinants were identified as well. These included specific environmental conditions such as pollution and contamination of water, as well as pre-and-post migration experiences ranging from rape, sexual assault, and abuse to extortion and several other specific geopolitical and economic factors [34, 48].

Gaps in the Literature

Immigration policies have led to a set of dilemmas and issues associated with the delivery of care to immigrants by providers, practitioners, and health promoters. However, little is known about the most recent immigration policies across the world and their potential impact on services and health outcomes among undocumented immigrants. Some of the most recent immigration policies use highly subjective standards for enforcement, which make it easier for immigration officers and personnel to enforce these policies, but in turn have the potential to expose immigrants to increased profiling and potential discrimination.

For instance, Section 287(g) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) in the United States, added in 1996, authorizes the US Immigration and Custom Enforcement (ICE) to enter into agreements with state and local law enforcement agencies to enforce federal immigration law during their regular, daily law-enforcement activities. The original intent was to “target and remove undocumented immigrants convicted of violent crimes, human smuggling, gang/organized crime activity, sexual-related offenses, narcotics smuggling and money laundering” [54]. In its first decade, there was relatively little use of Section 287(g) authority, but over the past five years its use has accelerated at an alarming rate. Nationally, over 72 jurisdictions have implemented Section 287(g) agreements in 23 states. More than 1,240 active 287(g) officers have been trained and certified; and since 2006, federal funding to facilitate 287(g) agreements has increased dramatically every year, growing from $5 million allocated in 2006 to more than $68 million in 2010. The Section 287(g) program has been criticized for its unintended infringement on individual rights and civil liberties. According to reports, local officials are using this authority more for minor or petty offenses (such as traffic violations) than for serious crimes as intended [54].

Furthermore, there is a legitimate concern that people who are potentially subject to 287(g) enforcement, whether documented or undocumented, may refrain from seeking vital services, including medical services, from any local government or private agency—even agencies unrelated to law enforcement—for fear of exposing themselves or their family members to legal sanctions or harassment. However, the extent and impact of such perceptions and behaviors is unclear. More research is needed to understand the impact of federally enforced immigration policies on health outcomes and access to health. In addition, in April 2012, Arizona legislators passed the Support Our Law Enforcement Safe Neighborhoods Act (SB 1070). SB 1070 makes it a crime to fail to possess immigration documents, and it also expands police power to detain individuals on a “reasonable suspicion” basis and detain persons “suspected” of being in the United States illegally. An assessment of the long-term impact of this law and similar state-level immigration policies for public health is urgently needed. A call for action at the national level has been made to better understand these phenomena through research and advocacy work [55].

Another telling example is found in the case of Spain. The immigrant population in Spain, whether documented or not, has been entitled to health services and care since 2000. However, under Royal Decree 16/2012, which was issued in April 2012, most undocumented immigrants are no longer eligible to receive free medical treatment. Only undocumented individuals under 18 or pregnant women could receive emergency care. In addition, Royal Decree 16/2012 might have a profound impact on HIV prevention and treatment initiatives because undocumented immigrants’ access to HIV medications and services will be negatively impacted [56, 57].

Aside from specific immigration policies, there is also much debate in the United States over the potential impact of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 on access to health services for undocumented immigrants [58]. The sweeping legislation designed to ensure that almost all Americans can obtain health insurance may reduce access to care for many undocumented immigrants by isolating them from the general, formerly uninsured, population. In addition, healthcare safety net hospitals and clinics, which are the main providers of health care and services for undocumented immigrants, might face funding and reimbursement challenges by ACA, making it impossible to continue providing services to undocumented immigrants. ACA’s exclusion and denial of participation of undocumented immigrants may lead to further marginalization of undocumented immigrants and alienation from health services, which could result in difficulties in monitoring infectious diseases. In addition, this exclusion could impact clinics’ services and overall operations since, under the ACA, clinics will not be reimbursed for providing the broad-based screening services related to sexual health and disease prevention (e.g., STI prevention counseling for high risk adults and sexually active adolescents, herpes vaccination for all adults, syphilis screening for high risk adults and pregnant women, HPV DNA testing for 30+ women, tobacco cessation counseling) to undocumented immigrants.

Discussion

The volume of international travel and cross-border migration places pressure on states to maintain orderly migration systems. Some nation states have responded with tough immigration policies or departmental initiatives to address the issue of illegal migration. Some strategies, such as immigration detention and the use of check points to target undocumented immigrants, pose a serious threat to accessing health services as well as potentially negative mental health outcomes for this vulnerable population. Other policies have a large impact on immigrants’ health and welfare by forcing people to remain in situations where they face a greater chance of persecution, isolation, and discrimination leading to major health consequences and outcomes.

The presence of anti-immigration policies at the local level had a significant effect on access to health services among undocumented immigrants. Undocumented immigrants, including LGBT individuals at higher risk of HIV acquisition, were often barred access to vital health services, including HIV prevention and care coordination services. In addition, undocumented Latinas have been denied access to or chosen not to seek out prenatal care services because they feel that accessing these services would potentially expose them to discrimination from providers as well as put them at risk for deportation or other negative immigration consequences. Therefore, more research and policies are needed to address these concerns at the community level, particularly among groups at higher risk of HIV acquisition, including sex workers, and LGBT and transgender individuals.

Anti-immigration policies and departmental policies with anti-immigrant rhetoric are a major global determinant of health, particularly mental health. Undocumented immigrants were more likely to screen for depression, anxiety, and PTSD when compared to other documented immigrants and citizens in localities with anti-immigration policies. Our study shows that there is a growing evidence base to incorporate mental health into a global public health agenda and collective efforts to serve undocumented immigrants. Given that mental disorders are among the leading causes of diminished human productivity and impaired social functioning, a call for action is gravely needed. In fact, mental disorders contribute as much to a lifetime of disability as do cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, surpassing all types of cancers and HIV. Therefore, healthcare professionals, stakeholders, think tanks, policymakers, and advocates must remain engaged in discussions over migration and humanitarian protection to ensure a broader consideration of immigration policies, as well as the way such policies impact the mental health outcomes of undocumented immigrants and other vulnerable populations.

It is important to mention that while some developing nations are struggling with the financial crisis, income per capita has been on the rise in China, India, and Brazil, and these quickly developing nations are experiencing a new flow of migration. This new migration flow merits attention as these countries’ responses through legislative bills, laws, and policies might have a significant impact on immigrants’ health. Most of the research thus far has documented the health outcomes and impact of immigrants migrating from the developing to the developed world; however, these new migration patterns merit further scholarly research and policy analysis.

Potential policy actions identified to address the complex and critical findings of this systematic review include: the presence of anti-immigration policies or laws as a perceived barrier to accessing vital health services and the negative impact of these policies on mental health outcomes including PTSD, anxiety, and depression. These policy action items have been developed based on fundamental human rights and social justice premises. Social justice requires fairness and equality in the treatment and care of people, which includes how individuals are treated in a health care setting and the accessibility and provision of health services. In addition, social justice requires the fair distribution of resources, the preservation of human dignity, and the showing of equal respect for the interests of all members of the community [59, 60]. The standard of human rights requires governments to recognize the right of everyone to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health [60, 61].

Promoting a National and Local Culture of Access to Health for All

Relying on the findings related to immigration policies as barriers to access to health services, we have developed action items that should be taken into consideration to promote access to health for all, regardless of documentation status. Our action items have been developed recognizing that the improvement of the health and well-being of people is the ultimate aim of social and economic development.

Access to health care for immigrants is a global health issue and needs to be addressed with global policies and established conceptual frameworks.

Access to health care for immigrants is a national issue and should be addressed with a national policy on health care for noncitizen and undocumented immigrants.

- National immigration policy should recognize the public health risks associated with undocumented persons not receiving medical care.

- Increased access to comprehensive primary care, prenatal care, and chronic disease management may make better use of the public health funding by alleviating the need for costly emergency care.

- National immigration policy should encourage all residents to obtain clinically effective vaccinations and screening for prevalent infectious diseases.

Strengthening health care service provision by building new strategies: volunteer interpreter services and culturally and linguistically appropriate programs.

Countries should develop new and innovative strategies to support safety-net health care facilities, such as community health centers, qualified health centers, public health agencies, and hospitals that provide a disproportionate share of care for patients who are uninsured and from low socioeconomic status. All patients should have access to appropriate outpatient care, inpatient care, and emergency services.

Eliminating Discrimination in Health Care Settings

Anti-immigrant rhetoric impacted the health profession and providers’ attitudes towards immigrants and disenfranchised groups becoming another critical barrier to access to care.

Health care providers have an ethical and professional obligation to care for the sick. Immigration policies and laws should not interfere with the ethical obligation to provide care for all.

Health care providers should encourage and promote cultural diversity and linguistic competency training and education for health professionals, which should include awareness, respect, evidence-based research, and capacity-building components.

Health care providers should encourage and promote programs in continuing education at the local and national levels that assist health professionals in their efforts to better serve the needs of underserved populations.

Health care providers should build referral systems with other organizations in the community to provide better information to immigrants, in particular about life in the United States, their legal right, becoming a citizens, and educational opportunities.

Global Call for Action