Summary

Levels of overweight and obesity across low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) have approached levels found in higher-income countries. This is particularly true in the Middle East and North Africa and in Latin America and the Caribbean. Using nationally representative samples of women aged 19–49, n = 815,609, this paper documents the annualized rate of increase of overweight from the first survey in early 1990 to the last survey in the present millennium. Overweight increases ranged from 0.31% per year to 0.92% per year for Latin America and the Caribbean and for the Middle East and North Africa, respectively. For a sample of eight countries, using quantile regression, we further demonstrate that mean body mass index (BMI) at the 95th percentile has increased significantly across all regions, representing predicted weight increases of 5–10 kg. Furthermore we highlight a major new concern in LMICs, documenting waist circumference increases of 2–4 cm at the same BMI (e.g. 25) over an 18-year period. In sum, this paper indicates growing potential for increased cardiometabolic problems linked with a large rightward shift in the BMI distribution and increased waist circumference at each BMI level.

Keywords: Low- and middle-income countries, obesity prevalence, obesity trends, waist circumference

Introduction

At a time when the globe faces major economic difficulties related to the great recession and major food price increases (1), it might seem surprising to find that we continue to experience a marked increase in overweight and obesity in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). While overweight and obesity continue to rise, evidence has shown that obesity is not increasing at the same rate among all persons. Rather, we are finding an increasing rightward shift in the body mass index (BMI) distribution with a disproportionate increase at the higher end, with those who are obese shifting to even higher BMI levels (2). Of particular concern, in several countries we are finding evidence for higher waist circumferences (WCs) at each BMI level, further accelerating the health consequences of overweight and obesity (3,4).

This overview draws on recent studies examining overweight and obesity across the globe and adds new analyses of nationally representative surveys from LMICs. We use a systematic direct analysis of all primary databases and present nationally weighted data representative of each country. Specifically we address three important issues relevant for understanding the cardiometabolic consequences of current and future obesity patterns. First, we demonstrate a rapid increase in overweight occurring across most LMICs, even in the midst of all the global food and economic crises. Second, we show a shift to increasingly higher BMI levels among those who are overweight. Third, we reveal that body composition shifts are occurring such that at the same overweight or obesity level WCs are increasing in China and Mexico. Taken together, these issues forecast major potential upward shifts in the cardiometabolic consequences of current and future obesity.

Rapid increase in overweight and obesity prevalence

Methods

Data

All data are from nationally representative two-stage sample designs except for China (representative of 43% of the provinces). Most results are from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) (5). These are nationally representative, repeated cross-sectional household surveys administered primarily in LMICs selected by the funding agency. Additionally we used the Indonesian Family Life Surveys (IFLS) (6), the Brazil national surveys that include anthropometry (7), the Vietnamese National Living Standards Surveys (8–10), and the China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS) (11). All surveys used standardized direct measurement of weight and height. Because of limitations on data availability, we used only data on women aged 19–49 years old in this paper. The overall sample size is 815,609.

Analysis and measures

Standard measures of underweight, overweight and obesity were calculated for all countries from measured weight and height (BMI < 18.5 kg m–2 is underweight, BMI ≥ 25 kg m−2 to <30 kg m−2 is overweight, and BMI ≥ 30 kg mr−2 is obese) (12). Although lower BMI thresholds demonstrate disease risk in some populations, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the BMI cutoff point of ≥25 for international comparisons of overweight (13). We calculated and present nationally representative results (Appendix 1). Because of variation as to what is considered urban or rural across the countries, urban–rural status is defined by each country’s statistical office at the time of each survey. National population and gross national product (GNP) per capita are taken from World Bank indicators (14).

Results

Most recent prevalence of underweight and overweight status

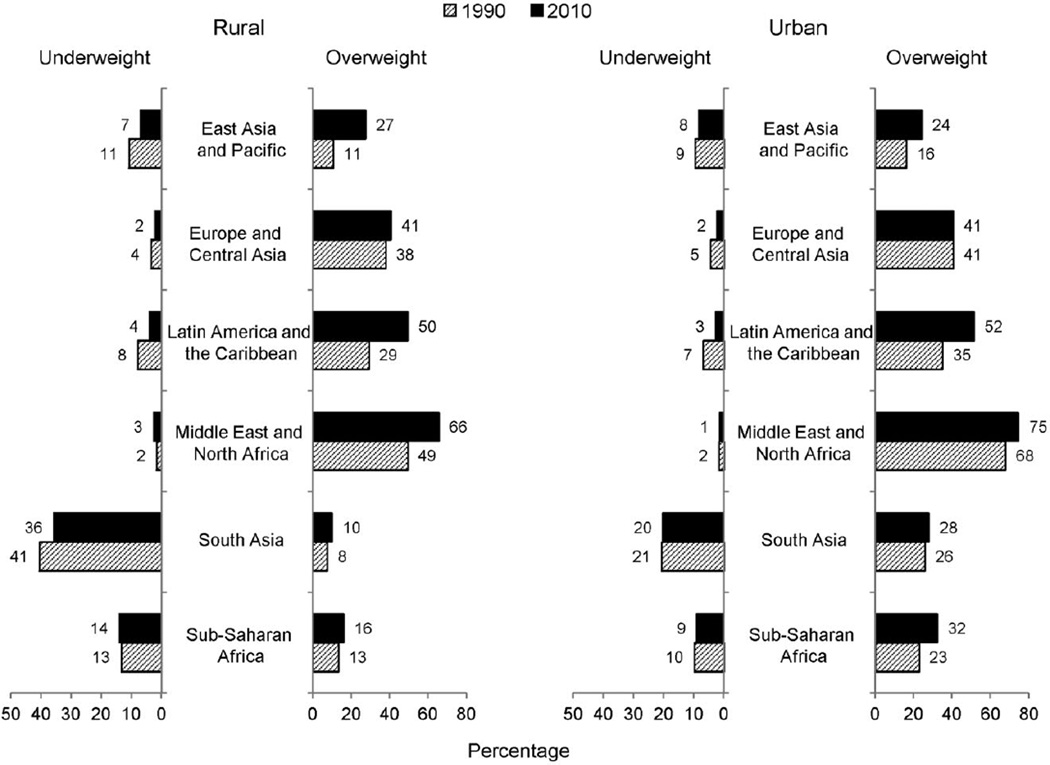

Overweight continues to increase across the LMICs, whereas underweight is declining. Figure 1 provides average overweight and underweight in the earliest year close to 1990 and the most recent year of data for each country by WHO regional classifications. These data indicate that over two-thirds of women in North Africa and the Middle East are overweight or obese, followed by Latin America and the Caribbean, where half the women are overweight or obese.

Figure 1.

Shifts in underweight and overweight across the low- and middle-income world, 1990–2010

*Data are weighted by each country’s population and based on nationally representative surveys of women aged 19–49 (n = 815,609).

Body mass index (BMI) 18.5< is underweight. BMI ≥ 25 is overweight. Data come from the year closest to 1990 and 2010 for each country.

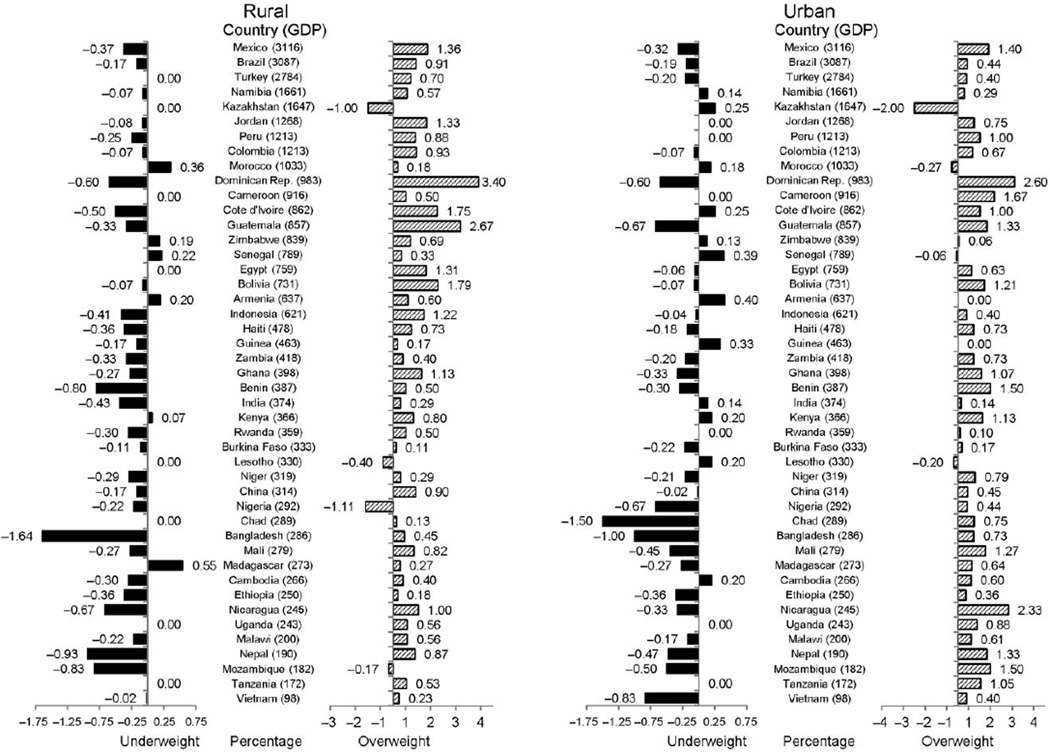

In Fig. 2, we present the same results stratified by urban and rural status. For many regions, overweight status is quite comparable in urban and rural areas. The major exceptions are South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. The higher underweight status in rural areas is especially marked for South Asia. It is important to note that the Indian and Vietnamese surveys were from the first years of the 20th century. Subsequently, India has experienced major economic growth with a subsequent decline in maternal undernutrition.

Figure 2.

Shifts in the prevalence of underweight and overweight across the low- and middle-income world, 1990–2010.

*Data are weighted by each country’s population and based on nationally representative surveys of women aged 19–49 (n= 815,609).

Body mass index (BMI) 18.5< is underweight. BMI ≥ 25 is overweight. Data come from the year closest to 1990 and 2010 for each country.

Annualized trends in prevalence changes of underweight and overweight

In Fig. 3, we show that almost all countries have increased prevalence of overweight in urban and rural areas and, in contrast, reduced prevalence of maternal underweight. Urban areas in all countries examined, except for four small countries (Kazakhstan, Morocco, Senegal, Lesotho), have increased overweight with an annualized change in prevalence of 0.75–1.0 percentage points. Similar increases are seen in rural areas.

Figure 3.

Annualized change in the prevalence of overweight and underweight in the 1990s–2000s sorted by gross national product (GNP) per capita.

Based on nationally representative surveys of women 19–45 (n= 815,609).

Body mass index (BMI) 18.5< is underweight. BMI ≥ 25 is overweight. Data come from the year closest to 1990 and 2010 for each country.

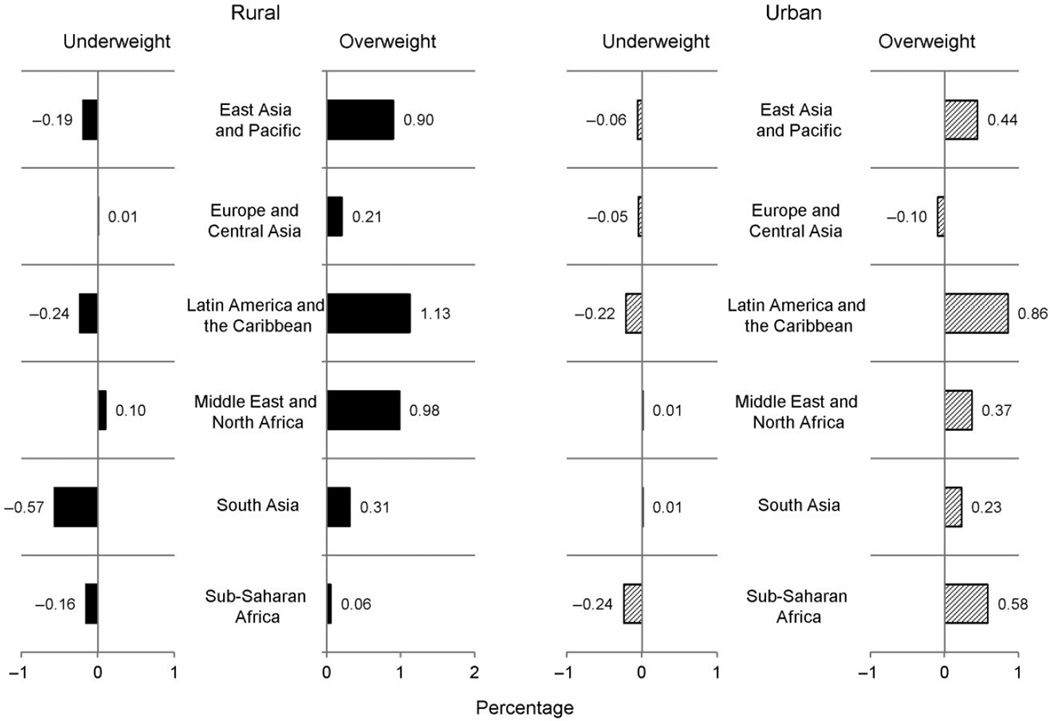

Figure 4 shows the shifts in underweight and overweight in urban and rural regions weighted by the country’s population. Here differential shifts between urban and rural areas become apparent, with greater annual increases in prevalence in rural areas in most regions except sub-Saharan Africa.

Figure 4.

Annualized change regional population-weighted percent underweight and overweight – in the 1990s and 2000s, rural/urban.

*Data are weighted by each country’s population and based on nationally representative surveys of women aged 19–49 (n= 815,609).

Body mass index (BMI) 18.5< is underweight. BMI ≥ 25 is overweight. Data come from the year closest to 1990 and 2010 for each country.

Increased BMI levels among overweight and obese populations

Methods

Data

We use the same data on adult women aged 19–49 described earlier.

Quantile regression

Using quantile regression, we examine shifts in BMI levels at the 95th percentile (results are comparable for the 85th percentile). Quantile regression approximates the median or other quantiles of the response relationship (15) and provides a statistically robust method for examining the BMI distribution using both the central tendency and the statistical dispersion. Quantile regression is capable of providing a more complete statistical analysis of the stochastic relationships among random variables. The figures presented are based on the actual BMI data regressed against age and, for some models, age squared based on appropriate model fit. The quantile regression equation was then used to create a predicted BMI level for the selected ages.

Results

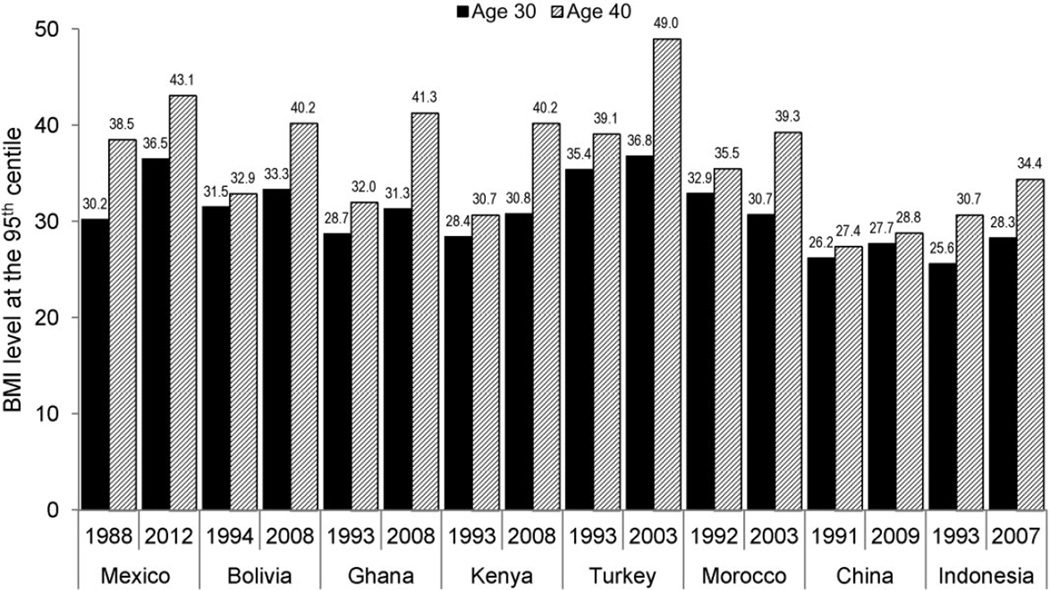

We examined the shifts in BMI levels at the 5th, 50th and 95th percentiles in all the DHS countries. In general we find a marked increase in BMI levels at each percentile across the globe, particularly the 95th. Here we present data for eight countries that highlight the large increases in BMI at the 95th percentile among those aged 30–40 in Mexico (1988 and 2011–2012), Bolivia (1994 and 2008), Ghana (1993 and 2008), Kenya (1989 and 2008), Turkey (1993 and 2003), Morocco (1992 and 2003), China (1991 and 2009) and Indonesia (1993 and 2007; see Fig. 5). Results from these eight countries provide a sense of the shifts occurring across Latin America and the Caribbean, sub-Saharan Africa, North Africa and the Middle East, and Asia. While the size of the increase in BMI level varies by age and country, these results are indicative of the dramatic shift rightward in the BMI distribution.

Figure 5.

Predicted body mass index (BMI) increases across selected countries at the 95th centile in age 30- and 40-year-old women.

*Data are weighted by each country’s population and based on nationally representative surveys of women aged 19–49 (n= 815,609).

BMI 18.5< is underweight. BMI ≥ 25 is overweight. Data come from the year closest to 1990 and 2010 for each country.

To place these results in perspective, a 1 BMI-unit increase for a woman 1.6 m tall is about 3 kg of weight. As such, the 6–7 BMI-unit increase at the 95th percentile observed in Mexico converts to about 10 kg of weight gain.

Essentially in the African and Latin American and Middle East/North African sample countries, mean BMI at age 40 for women was at or over 40 BMI units. Only in Asia were must lower levels founds at the 95th centile. In related work we are doing for Mexico and China, we see similar shifts in the BMI distribution at both the 5th and 50th centiles, denoting a major rightward shift in the BMI distribution for both countries (3,4).

Potential obesity phenotype changes

Methods

Data

Very few LMIC countries collect data on WC. China (1993 and 2009) collected WC data for over a decade as a part of national surveys. We present select results on China that allows us to examine WC–BMI relationships for both genders.

Analysis

Regression models were run with samples combined for 1993 and 2009 to allow us to test that the time interaction with BMI was significant. We examined the WC/BMI ratio and the impact of BMI on WC in ordinary least squares regressions for selected age subpopulations: 12–18, 19–39 and 40–59. We tested for linearity in the age relationship using both LOWESS (locally weighted scatterplot smoothing) regressions and testing BMI and BMI squared. We found linear relationships within the age groups selected for both sets of outcomes (WC/BMI as a function of time period, age and WC as a function of BMI, time period, age and interactions of time with the other exposures). We examined WC shifts by age and BMI level.

Results

WCs are rising at each BMI level and at all ages in China (see Table 1). We show the changes for 40-year-old men and women as part of a larger study. These more detailed papers are coming out with the full results across an array of age groups. We present here a few of the Chinese preliminary results just for adults 40–59 in this table. The changes range from 2 cm for adolescent to 3–4 cm for adults across all age groups with slightly smaller changes among adolescents (16).

Table 1.

Waist circumference (cm) changes for selected BMIs: China*

| Age/gender | 1993 | 2009 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI level | 18.5 | 25 | 28 | 18.5 | 25 | 28 |

| Men 40 | 69.4 | 83.9 | 90.5 | 72.2 | 87.6 | 94.7 |

| Women 40 | 67.6 | 80.7 | 86.8 | 69.2 | 83.2 | 89.6 |

China Health and Nutrition Survey 1993 and 2009. All results for changes between 1993 and 2009 are statistically significant at the P < 0.01 level.

BMI, body mass index.

Discussion

The most recent global data provide a rather consistent picture of weight status trends in LMICs. The trends include larger increases in overweight and obesity than reductions in underweight status, and a potentially greater upward shift in the BMI level among those who are overweight and obese (rightward shift in the right tail of the BMI distribution). Additionally higher WCs among overweight and obese women and men in selected countries suggest that these recent increases in overweight and obesity, at least in the countries examined and possibly in many more, may be linked with greater risks of other significant cardiometabolic problems.

A number of recent studies have addressed global overweight status (17). Most studies, however, have focused on attempting to understand if the burden of overweight status has affected the populations with higher or lower socioeconomic status (SES), measured by either education or a combined DHS wealth index. Five major studies have undertaken this work. The earliest by C. A. Monteiro and colleagues found that a lower SES was a protective factor against obesity (they did not analyse overweight and obesity combined), but that countries with GNP per capita above $2,500 had a greater risk of obesity among lower SES women (there was inadequate data on men to make major clear generalizations) (18,19). J. C. Jones-Smith studied national trends in overweight using both the DHS wealth index and education and found that 27 of 37 countries showed a positive SES–overweight prevalence, but that higher per capita GNP and greater equity were both linked with greater overweight among lower SES groups (20–22). The most convincing Jones-Smith study was a longitudinal analysis in China of the shift over time of a higher burden of overweight from women with higher education to women with lower education. Using cross-sectional data, Subramanium et al. found for 52 of 54 countries a positive SES–overweight status (23). Their results of a positive SES–overweight relationship globally differ from several studies by Monteiro et al. (using just obesity) and Jones-Smith et al. (using overweight plus obesity), which found that with increased national wealth, the burden of overweight and obesity shifts to lower-educated subpopulations (18–22).

Both our study and a recent excellent study support a potential upward shift in the BMI level among those who are overweight and obese (2). F. Razak et al. similarly show that the BMI levels among women of childbearing age at the 95th percentile are growing more rapidly relative to those at the fifth percentile (2). This study also used Q–Q plots to compare two probability distributions by plotting their quantiles against each other. Q–Q plots to show that for 37 DHS LMICs, mean BMI increases are occurring disproportionately among groups with already high baseline BMI levels (2). This is comparable with an earlier paper we published that showed this result for children and adults across sets of low- and middle-income and high-income countries (24).

Extending this work presented here, we use quantile regression to show marked increases in BMI levels at each point in the distribution, with larger shifts at the higher BMI levels for the United States, Mexico and the United Kingdom (3,4). At the 95th percentile, the shifts in BMI levels for countries from each LMIC region equate to weight increases of 5–10 kg. These represent a significant upward shift in weight among those who are overweight and obese and a subsequent greater impact on health and well-being.

Finally, our results in China suggest a potentially important increase in the implications for cardiometabolic problems accompanying the increasing WCs among the overweight and obese (3,4). In China, where the WC cutoff is established for women as 80 cm and men as 90 cm, this reflects major increases in cardiometabolic risk for those overweight with a BMI of 25 and even lower (25). Other unpublished research suggests similar findings for Mexico, the United States and the United Kingdom (3,4). There is no universally accepted cutoff for high WCs in China; however, 80 for women and 94 for men are suggested (26). Important segments of the adult Chinese overweight and obese population are above this threshold. Unfortunately WC and/or skin-fold data are collected in far too few countries to allow systematic analysis of this shift across a large number of LMICs. Janssen showed a similar trend of increasing WC among the obese in Canada (27). It remains unclear why this shift is occurring. It may be that reductions in physical activity are linked with increased WC, as several studies suggest that increased physical activity can reduce visceral fat and WC (28,29). It is also possible that increases in sugar intake and the effects of fructose on visceral fat explain these shifts; however, this link is far from being widely accepted (30–39). Or it might be other dietary factors (40,41).

There are limitations to this work. Unfortunately we do not have adequate data on adult men overweight and obesity across the globe to present meaningful patterns and trends for them. Whereas recall data exist for adult men and older women, their use is not recommended in LMIC settings, because scales are not commonly used and doctor visits are much more infrequent, particularly for lower-income populations.

In summary, this paper indicates growing potential for increased cardiometabolic problems among women in LMICs linked with a large rightward shift in the BMI distribution and increased WC at each BMI level. The major question generated in this paper is the extent to which this phenotype change of higher WC at overweight and obesity cutoff points found in China exists across all regions of the world in women and how much of this change is also found among men. To the extent that these patterns are generalizable, the increased overweight estimates indicate a far greater future cardiometabolic disease, disability and overall welfare burden for the globe than is reflected in current burden of disease estimates (42–46).

Acknowledgements

The Rockefeller Foundation and its Bellagio Conference Center are thanked for exceptional support for this conference. We also thank the Nutrition Transition Program of the University of North Carolina for additional financial support for this publication and related activities and Bloomberg Philanthropies for supporting all phases of final paper preparation. We thank the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01-HD30880, DK056350, 5 R24 HD050924, and R01-HD38700) for financial support. We also wish to thank Ms Frances L. Dancy for administrative assistance, Mr Tom Swasey for graphics support, and Dr Phil Bardsley and Ms Amanda Lyerley for programming support.

Appendix 1

Nationally representative data on women aged 19–49 overweight and underweight from the years closest to 1990 and 2010 for each country and regional averages*

| Country | Years | Region | 1990 Underweight |

1990 Overweight/ Obesity |

2010 Underweight |

2010 Overweight/ Obesity |

1990 Sample |

2010 Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| East Asia and Pacific | Weighted Avg. | 10.3 | 12.6 | 7.9 | 26.5 | |||

| Cambodia | 2000, 2010 | 1 | 19 | 7 | 17 | 12 | 5,884 | 7,648 |

| Timor-Leste | 2009 | 1 | 25 | 6 | 7,069 | |||

| China | 1991, 2011 | 1 | 8.6 | 12.5 | 6.2 | 27.2 | 3,058 | 3,106 |

| Indonesia | 1993, 2007 | 1 | 14.3 | 17.7 | 10.4 | 31.2 | 3,873 | 10,285 |

| Vietnam | 1992, 2002 | 1 | 28.0 | 1.9 | 25.5 | 4.7 | 2,890 | 31,592 |

| Central Asia | Weighted Avg. | 4.0 | 39.2 | 2.3 | 40.5 | |||

| Albania | 2008 | 2 | 2 | 44 | 6,015 | |||

| Armenia | 2000, 2005 | 2 | 3 | 46 | 4 | 47 | 4,984 | 5,170 |

| Azerbaijan | 2006 | 2 | 4 | 53 | 6,615 | |||

| Kazakhstan | 1995, 1999 | 2 | 6 | 44 | 7 | 37 | 2,834 | 1,852 |

| Kyrgyz Republic | 1997 | 2 | 5 | 33 | 2,642 | |||

| Moldova | 2005 | 2 | 4 | 47 | 5,947 | |||

| Turkey | 1993, 2003 | 2 | 3 | 53 | 2 | 58 | 1,646 | 1,998 |

| Uzbekistan | 1996 | 2 | 8 | 26 | 2,878 | |||

| Latin America/Caribbean | Weighted Avg. | 7.2 | 33.9 | 3.2 | 56.7 | |||

| Bolivia | 1994, 2008 | 3 | 3 | 36 | 1 | 56 | 798 | 10,879 |

| Colombia | 1995, 2010 | 3 | 4 | 40 | 3 | 51 | 2,190 | 34,371 |

| Dominican Republic | 1991, 1996 | 3 | 9 | 29 | 6 | 43 | 1,521 | 5,744 |

| Guatemala | 1995, 1998 | 3 | 3 | 44 | 2 | 51 | 1,615 | 901 |

| Guyana | 2009 | 3 | 8 | 53 | 3,218 | |||

| Honduras | 2005 | 3 | 3 | 53 | 12,152 | |||

| Haiti | 1994, 2005 | 3 | 17 | 17 | 13 | 26 | 916 | 3,198 |

| Nicaragua | 1998, 2001 | 3 | 4 | 49 | 2 | 55 | 8,529 | 8,378 |

| Peru | 1992, 2000 | 3 | 2 | 45 | 1 | 52 | 2,732 | 17,805 |

| Brazil | 1989, 2008 | 3 | 7.2 | 33.2 | 3.6 | 43.0 | 3,462 | 8,458 |

| Mexico | 1988, 2012 | 3 | 10.2 | 32.0 | 2.4 | 65.3 | 12,095 | 20,027 |

| Middle East/N Africa | 1.6 | 58.3 | 1.7 | 70.6 | ||||

| Egypt, Arab Republic | 1992, 2008 | 4 | 1 | 66 | 0 | 82 | 2,564 | 11,291 |

| Jordan | 1997, 2009 | 4 | 2 | 64 | 1 | 75 | 1,791 | 3,086 |

| Morocco | 1992, 2003 | 4 | 3 | 40 | 6 | 41 | 1,713 | 12,603 |

| South Asia | 35 | 12.2 | 39.2 | 16.8 | ||||

| Bangladesh | 1996, 2007 | 5 | 45 | 7 | 27 | 15 | 1,064 | 6,798 |

| India | 1998, 2005 | 5 | 34 | 13 | 31 | 18 | 56,485 | 80,034 |

| Maldives | 2009 | 5 | 7 | 48 | 3,737 | |||

| Nepal | 1996, 2011 | 5 | 28 | 4 | 15 | 18 | 223 | 3,745 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 12.4 | 16.2 | 12.1 | 22.2 | ||||

| Burkina Faso | 1992, 2010 | 6 | 16 | 12 | 13 | 16 | 1,171 | 3,684 |

| Benin | 1996, 2006 | 6 | 14 | 15 | 8 | 25 | 446 | 7,743 |

| Burundi | 2010 | 6 | 15 | 10 | 1,837 | |||

| Congo, Dem. Rep. | 2007 | 6 | 16 | 14 | 2,177 | |||

| Central Africa Republic | 1994 | 6 | 15 | 10 | 451 | |||

| Congo, Rep. Brazzaville | 2005 | 6 | 11 | 31 | 4,073 | |||

| Conte d’Ivoire | 1994, 1998 | 6 | 8 | 19 | 8 | 24 | 907 | 1,669 |

| Cameroon | 1998, 2004 | 6 | 6 | 24 | 5 | 35 | 566 | 2,783 |

| Ethiopia | 2000, 2011 | 6 | 29 | 5 | 24 | 8 | 7,527 | 8,006 |

| Gabon | 2000 | 6 | 6 | 32 | 1,395 | |||

| Ghana | 1993, 2008 | 6 | 12 | 18 | 7 | 36 | 498 | 2,799 |

| Guinea | 1999, 2005 | 6 | 13 | 17 | 12 | 19 | 1,212 | 1,877 |

| Kenya | 1993, 2008 | 6 | 9 | 17 | 10 | 32 | 1,387 | 4,728 |

| Comoros | 1996 | 6 | 10 | 24 | 183 | |||

| Liberia | 2007 | 6 | 9 | 26 | 3,788 | |||

| Lesotho | 2004, 2009 | 6 | 4 | 49 | 4 | 48 | 2,047 | 2,571 |

| Madagascar | 1997, 2008 | 6 | 21 | 5 | 24 | 9 | 576 | 4,507 |

| Mali | 1995, 2006 | 6 | 16 | 13 | 11 | 24 | 807 | 5,901 |

| Mauritania | 2000 | 6 | 11 | 44 | 4,482 | |||

| Malawi | 1992, 2010 | 6 | 11 | 10 | 6 | 23 | 790 | 3,379 |

| Mozambique | 1997, 2003 | 6 | 12 | 14 | 8 | 19 | 736 | 5,800 |

| Nigeria | 1999, 2008 | 6 | 13 | 32 | 9 | 27 | 741 | 16,889 |

| Niger | 1992, 2006 | 6 | 22 | 9 | 17 | 17 | 1,061 | 1,853 |

| Namibia | 1992, 2006 | 6 | 11 | 27 | 12 | 33 | 1,098 | 6,335 |

| Rwanda | 2000, 2010 | 6 | 7 | 15 | 5 | 20 | 4,379 | 3,437 |

| Sierra Leone | 2008 | 6 | 11 | 33 | 2,013 | |||

| Senegal | 1992, 2010 | 6 | 15 | 21 | 19 | 26 | 1,090 | 2,907 |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 2008 | 6 | 8 | 39 | 1,381 | |||

| Swaziland | 2006 | 6 | 2 | 59 | 3,165 | |||

| Chad | 1996, 2004 | 6 | 24 | 7 | 22 | 8 | 1,109 | 1,087 |

| Togo | 1998 | 6 | 9 | 19 | 592 | |||

| Tanzania | 1991, 2010 | 6 | 10 | 13 | 9 | 28 | 1,517 | 5,099 |

| Uganda | 1995, 2011 | 6 | 9 | 14 | 9 | 25 | 974 | 1,259 |

| Zambia | 1992, 2007 | 6 | 11 | 17 | 8 | 26 | 1,217 | 3,327 |

| Zimbabwe | 1994, 2010 | 6 | 3 | 28 | 5 | 37 | 747 | 5,248 |

Regional averages are based on the weighted average of each country in the total sample of country populations for this region (body mass index [BMI] < 18.5 kg mr−2 is underweight, BMI ≥ 25 kg mr−2 is used for overweight plus obesity).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- 1.von Braun J, Ahmed A, Asenso-Okyere K, et al. High food prices: the what, who, and how of proposed policy actions. In: IFPRI, editor. Policy Brief. Washington DC: IFPRI; 2008. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Razak F, Corsi DJ, Sv S. Change in the body mass index distribution for women: analysis of surveys from 37 low- and middle-income countries. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001367. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albrecht S, Barquera S, Rivera J, Popkin B. Secular changes in obesity phenotype in Mexican origin populations: a comparative analysis of Mexico and the U.S. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Popkin B, Albrecht S, Stern D, Gordon-Larsen P, Adair L. Secular changes in obesity-waist circumference patterns: China, Mexico, the United Kingdom and the United States. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 5.DHS M, editor. ICF International. Measure DHS: Demographic and Health Surveys. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.RAND. Indonesian Family Life Survey. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 7.IBGE – Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Pesquisa de orçamentos familiares. Pesquisa de orçamentos familiares, 2008–2009: análise do consumo alimentar pessoal no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro. 2011:1–150. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. [Google Scholar]

- 8.General Statistical Office. Vietnam Living Standards Survey, 1992–1993. 1994 Hanoi. [Google Scholar]

- 9.General Statistical Office. Vietnam Living Standards Survey 1997–1998. 2000 Hanoi. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuan NT, Tuong PD, Popkin BM. Body mass index (BMI) dynamics in Vietnam. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008;62:78–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Popkin BM, Du S, Zhai F, Zhang B. Cohort profile: the China Health and Nutrition Survey – monitoring and understanding socioeconomic and health change in China, 1989–2011. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:1435–1440. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO/FAO. Expert Consultation on Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases Report of the joint WHO/FAO expert consultation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363:157–163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Bank. [accessed 30 March 2013];World Development Indicators. 2013 [WWW document]. URL http://data.worldbank.org/indicator.

- 15.Koenker R, Hallock KF. Quantile regression. J Econ Perspect. 2001;15:143–156. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stern D, Duffey K, Barquera S, Rivera-Dommarco J, Popkin B. Sugar sweetened beverage sales and consumption trends in Mexico: 1999–2012. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang L. Summary Report of China Nutrition and Health Survey 2002. Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monteiro CA, Conde WL, Lu B, Popkin BM. Obesity and inequities in health in the developing world. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:1181–1186. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monteiro CA, Moura EC, Conde WL, Popkin BM. Socioeconomic status and obesity in adult populations of developing countries: a review. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:940–946. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones-Smith J, Gordon-Larsen P, Siddiqi A, Popkin B. Emerging disparities in overweight by educational attainment in Chinese adults (1989–2006) Int J Obes. 2012;36:866–875. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones-Smith J, Gordon-Larsen P, Siddiqi A, Popkin B. Is the burden of overweight shifting to the poor across the globe [quest]. Time trends among women in 39 low- and middle-income countries (1991–2008) Int J Obes. 2012;36:1114–1120. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones-Smith JC, Gordon-Larsen P, Siddiqi A, Popkin BM. Cross-national comparisons of time trends in overweight inequality by socioeconomic status among women using repeated cross-sectional surveys from 37 developing countries, 1989–2007. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:667–675. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Subramanian SV, Perkins JM, Ozaltin E, Davey Smith G. Weight of nations: a socioeconomic analysis of women in low- to middle-income countries. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:413–421. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.004820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Popkin BM. Recent dynamics suggest selected countries catching up to US obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:284S–288S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28473C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stern D, Smith LP, Zhang B, Gordon-Larsen P, Popkin BM. Changes in waist circumfrence relative to BMI in China adults from 1993 to 2009. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wildman RP, Gu D, Reynolds K, Duan X, He J. Appropriate body mass index and waist circumference cutoffs for categorization of overweight and central adiposity among Chinese adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:1129–1136. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.5.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janssen I, Shields M, Craig C, Tremblay M. Changes in the obesity phenotype within Canadian children and adults, 1981 to 2007–2009. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20:916–919. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ismail I, Keating S, Baker MK, Johnson N. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of aerobic vs. resistance exercise training on visceral fat. Obes Rev. 2012;13:68–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maersk M, Belza A, Stødkilde-Jørgensen H, et al. Sucrose-sweetened beverages increase fat storage in the liver, muscle, and visceral fat depot: a 6-mo randomized intervention study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95:283–289. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.022533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stanhope KL, Havel PJ. Fructose consumption: recent results and their potential implications. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1190:15–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05266.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sondergaard E, Gormsen LC, Nellemann B, Jensen MD, Nielsen S. Body composition determines direct FFA storage pattern in overweight women. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;302:E1599–E1604. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00015.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stanhope KL, Havel PJ. Fructose consumption: considerations for future research on its effects on adipose distribution, lipid metabolism, and insulin sensitivity in humans. J Nutr. 2009;139:1236S–1241S. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.106641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stanhope KL. Role of fructose-containing sugars in the epidemics of obesity and metabolic syndrome. Annu Rev Med. 2012;63:329–343. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-042010-113026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stanhope KL. Consuming fructose-sweetened, not glucose-sweetened, beverages increases visceral adiposity and lipids and decreases insulin sensitivity in overweight/obese humans. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1322–1334. doi: 10.1172/JCI37385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stanhope KL, Havel PJ. Fructose consumption: potential mechanisms for its effects to increase visceral adiposity and induce dyslipidemia and insulin resistance. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2008;19:16–24. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3282f2b24a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tchernof A, Despres JP. Pathophysiology of human visceral obesity: an update. Physiol Rev. 2013;93:359–404. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00033.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tappy L, Le KA, Tran C, Paquot N. Fructose and metabolic diseases: new findings, new questions. Nutrition. 2010;26:1044–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lustig RH. Fructose: it’s ‘alcohol without the buzz’. Adv Nutr. 2013;4:226–235. doi: 10.3945/an.112.002998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lustig RH, Schmidt LA, Brindis CD. Public health: the toxic truth about sugar. Nature. 2012;482:27–29. doi: 10.1038/482027a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parikh S, Pollock NK, Bhagatwala J, et al. Adolescent fiber consumption is associated with visceral fat and inflammatory markers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E1451–E1457. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Souza RJ, Bray GA, Carey VJ, et al. Effects of 4 weight-loss diets differing in fat, protein, and carbohydrate on fat mass, lean mass, visceral adipose tissue, and hepatic fat: results from the POUNDS LOST trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95:614–625. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.026328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2224–2260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2197–2223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salomon JA, Vos T, Hogan DR, et al. Common values in assessing health outcomes from disease and injury: disability weights measurement study for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2129–2143. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61680-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2163–2196. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]