Abstract

4′-ethynyl-2-fluoro-2′-deoxyadenosine (EFdA) is a novel nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor with a unique mechanism of action and highly potent activity against both wild-type and clinically relevant drug resistant HIV-1 variants. Furthermore, in vivo efficacy and safety evaluations have shown EFdA to be a promising therapeutic candidate for use in the treatment of HIV infection. However, little is known about the pharmacokinetic and biopharmaceutical properties of EFdA. In this study, we evaluated cellular EFdA transport using Caco-2 and Madin-Darby Canine Kidney II (MDCKII) in vitro cell models. Studies using Caco-2 cell monolayers showed that EFdA efflux ratios were >2.0, suggesting that active drug transport mechanisms may play a role in EFdA flux. ABCB1 transporter (PGP1) inhibition was assessed using the acetomethoxy derivate of calcein (calcein-AM) as a fluorescent probe in both wild-type MDCKII and PGP1 overexpressing MDCKII cells. Nonetheless, our data showed that EFdA is not a substrate of PGP1. Additionally, comparative bidirectional flux of EFdA and Lucifer yellow (LY, a well-known paracellular marker) was studied over a range of EFdA concentrations. In MDCKII monolayers, EFdA had an apparent permeability coefficient (Papp) (a–b) of < 1×10−6 cm/s. The Papp values significantly increased in the presence of the paracellular permeability enhancer, indicating that EFdA primarily permeates via the paracellular route.

Keywords: EFdA, bidirectional flux, MDCKII, Caco-2, PGP1

1. Introduction

HIV impacts over 40 million people worldwide. An estimated 0.8% of adults aged 15–49 years are living with HIV worldwide, although the burden of the epidemic continues to vary considerably between by region and country (UNAIDS, 2012). So far, the most effective treatment for HIV is highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), which consists of a combination of several antiretroviral agents from at least two different classes, such as HIV protease inhibitors, entry inhibitors, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), and nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs). The latter class is generally used in first line treatment. While HAART dramatically improves the clinical outcomes for patients infected with HIV, drug side effects and the emergence of HIV resistance to these drugs remain serious issues. Thus, new drug substances are needed to maintain the therapeutic options for patients infected by HIV.

EFdA is a new NRTI with a novel mechanism of action which has shown highly potent antiretroviral activity and favorable toxicity profiles both in vitro (Nakata et al., 2007; Kawamoto et al., 2008; Michailidis et al., 2009 and 2013) and in vivo (Hattori et al., 2009; Murphey-Corb et al., 2012). EFdA thus shows promise as an antiretroviral drug candidate for HIV treatment.

In order to develop a suitable oral delivery system for EFdA, preformulation evaluations (analytical, physicochemical, pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical) are necessary to provide valuable preclinical data for future product development. However, little was known about the in vitro transport characteristics of EFdA. Active efflux into the intestinal lumen can drastically lower the bioavailability of orally administered drugs, which is primarily mediated by the ATP-binding cassette transporter superfamily. Among these transporters, PGP1 plays a very important role (Benet et al., 1996).

We conducted bidirectional transport studies of EFdA in Caco-2 monolayers to evaluate its transport characteristics. We also studied the in vitro cytotoxicity of EFdA and tested PGP1 inhibition using calcein-AM as the fluorescent probe in PGP1 overexpressing MDCKII and MDCKII cells.

It is well known that intestinal drug absorption occurs via either the transcellular or paracellular pathway (Deli, 2009). The preferred pathway for orally administered drugs is generally the transcellular route, which is governed by simple passive diffusion for lipophilic molecules or by carrier-mediated transport for certain compounds that can serve as substrates for intestinal transporters. In contrast, the paracellular route is typically restricted by the relatively small pore size of the aqueous channel and the presence of tight junctions that act as barriers to drug absorption. Despite these limitations, the paracellular pathway is also an important diffusion pathway for small hydrophilic drugs (Bourdet et al., 2007). Thus, it is pivotal to understand the potential intestinal absorption pathway for EFdA. To this end, a series of studies were conducted to evaluate the bidirectional flux of EFdA and LY at different concentrations across MDCKII monolayers in the absence and presence of the paracellular permeability enhancer.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

The EFdA was a generous gift from Yamasa Corp. (Chiba, Japan). BD Falcon cell culture inserts, methanol (HPLC grade), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) was purchased from Lonza (Walkersville, MD). Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) was obtained from Spectrum Chemical (Gardena, CA). Quinidine was obtained from Alfa Aesar® (Lancashire, UK). Ivermectin, LY and Triton X-100 were purchased from MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH). Calcein-AM was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences (Lausen, Switzerland). 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH7.4), Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) and penicillin-streptomycin were purchased from Mediatech (Manassas, VA).

2.2. High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis

An HPLC system (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA) equipped with an auto injector (model 717), a quaternary pump (model 600), and a photodiode array detector (model 2996), was used for quantitative analysis of EFdA. Empower 2 software was used to control the HPLC system. Liquid chromatography was carried out using a Zorbax Eclipse XDB C18 column (3.5μm, 100 × 4.6 mm). The mobile phase consisted of (A) 0.4% phosphoric acid in MilliQ water and (B) methanol using a gradient elution of 10–40% B at 0–5 min, 40–60% B at 5–10 min, and 60–10% B at 10–15 min at a flow rate of 0.8 ml/min. EFdA samples collected from the bidirectional flux studies were directly injected at a volume of 10μl, and EFdA was determined by ultraviolet detection at 260 nm. All experiments were performed at room temperature and the total area of peak was used to quantify EFdA (Zhang et al., 2013).

2.3. Cell culture

The Caco-2 cell line was provided by Dr. Charlene S. Dezzutti (Magee-Womens Research Institute, Pittsburgh, PA). Caco-2 cells were cultured in high glucose DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% non-essential amino acids, 1% L-glutamine and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. MDCKII was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and PGP1 overexpressing MDCKII was obtained from the Netherlands Cancer Institute. MDCKII and PGP1 overexpressing MDCKII cells were cultured in high glucose DMEM medium, supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% L-glutamine and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Both cell lines were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 under fully humidified conditions. The cells were grown to 90% confluence and harvested by trypsinization using a 0.25% trypsin and 0.02% EDTA solution.

2.4. Bidirectional flux of EFdA in Caco-2 cell monolayers

Caco-2 cells were seeded at a density of 2.0 × 105 cells onto each polycarbonate insert (1.12 cm2, 0.4μm, Corning) in 12-well tissue culture plates and were allowed to grow and differentiate for 21 days. The cell growth medium was changed every other day. The quality of the monolayers grown on the permeable membrane was assessed by measuring the transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) of the monolayers using a Millicell-ERS (electrical resistance system) apparatus (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Only Caco-2 monolayers displaying TEER values > 600 Ωcm2 were used in this study. Bidirectional transport of EFdA, apical-to-basolateral (a–b) and basolateral-to-apical (b-a), was performed using Caco-2 cell monolayers. The incubation medium was HBSS buffered with 25mM HEPES (pH 7.4). EFdA was dissolved in the incubation medium by sonication.

Before each experiment, the monolayers were washed twice with HBSS, and then the monolayers were incubated at 37°C for 20 min with HBSS, followed by the measurement of TEER values. In order to investigate the bidirectional transport of EFdA across Caco-2 monolayers, 0.75 ml of incubation medium containing EFdA (25, 100, or 400 μM) was added to the apical side, and 1.5 ml of incubation medium without EFdA was added to the basolateral side. Conversely, for determination of b-a transport, 1.5 ml of incubation medium containing EFdA (25, 100, or 400 μM) was added to the basolateral side, and 0.75 ml of incubation medium without the drug substance was added on the apical side. The cell monolayers were incubated at 37°C for 2 h with gentle shaking. 200 μl of medium was withdrawn from each donor or receptor compartment at specific time points (0, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90 and 120 min), and then the same volume of fresh incubation medium was replenished. TEER values were measured at each time point to monitor the change in integrity of monolayers. EFdA in all samples was analyzed using HPLC as described above.

The apparent permeability coefficient (Papp; cm/s) of EFdA was determined from the amount of compound transported over time. Papp was calculated according to the following equation:

| (1) |

where dQ/dt is the initial linear flux (μmol/s), A is the surface area of exposure (cm2) and C0 is the initial concentration in the donor chamber (μM). The ratio of the transport in the b-a direction to that in the a–b direction was calculated in order to highlight any asymmetry in the bidirectional transport of the compounds. The efflux ratio was calculated using the following equation:

| (2) |

2.5. In vitro cytotoxicity

MDCKII and PGP1 overexpressing MDCKII cells were seeded separately at a density of 5 × 103 per well in 96-well plates. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2, the growth medium was replaced with 200 μl medium containing the different compounds with a series of concentrations. After 48 h incubation, cell survival was then measured using an MTT assay (Zhang et al., 2013). 180 μl of fresh growth medium and 20 μl of MTT (5 mg/ml) solution were added to each well. The plate was incubated for an additional 4 h at 37°C. After removal of the mixture, 200 μl of DMSO was added to each well to dissolve the purple formazan crystals. The plates were vigorously shaken before measuring the relative color intensity. The absorbance at 595 nm of each well was measured by a microplate reader (DTX 880, Beckman Coulter, Brea, USA).

2.6. PGP1 inhibition test

The calcein-AM uptake assay was performed in 96-well plates as reported earlier (Weiss et al., 2003). Briefly, all incubation steps and the cell lysis were conducted at 37°C on a rotary shaker with moderate speed. MDCKII and PGP1 overexpressing MDCKII cells were separately seeded at a density of 5 × 103 per well in 96-well plates. After 24 h incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2, the cells were washed with pre-warmed HBSS supplemented with 10 mM HEPES (HBSSH) and pre-incubated with HBSSH for 30 min and, subsequently, with the test compounds for 10 min. After pre-incubation, calcein-AM was added (final concentration, 1 μM) and the cells were incubated at 37°C for another 60 min. After incubation, the supernatant was removed, and the cells were washed with ice-cold HBSSH twice and lysed with 1% Triton X-100 for 30 min at 37°C with moderate shaking. The fluorescence of calcein generated within the cells was analyzed in a fluorescence microplate reader (DTX 880, Beckman Coulter, Brea, USA) with 485-nm excitation and 535-nm emission filters. Calcein fluorescence in the tested groups was normalized by the fluorescence of calcein in the negative control group (calcein-AM alone). Control experiments determined that EFdA had no impact on calcein fluorescence.

2.7. Bidirectional flux of EFdA and LY in MDCKII monolayers with or without EDTA treatment

For the bidirectional flux study of EFdA and LY in MDCKII monolayers, MDCKII cells were seeded at a density of 2.0 × 105 cells onto each polycarbonate insert (1.12 cm2, 0.4μm, Corning) in 12-well culture plates and were allowed to grow and differentiate for 7 days. The cell growth medium was changed every other day. The quality of the monolayers grown on the permeable membrane was assessed by measuring the TEER of the monolayers using a Millicell-ERS apparatus. Only MDCK II monolayers displaying TEER values > 200 Ωcm2 were used in this study. The bidirectional flux of EFdA and LY was conducted as described in the Section 2.4. LY was used as a control in this study (Coyuco et al., 2011). LY fluorescence intensity was measured using a fluorescence microplate reader with λex = 485 nm and λem = 535 nm. EFdA, in all samples, was analyzed using HPLC as described above. In order to explore the potential paracellular route of EFdA, a solution of 5 μM EDTA in HBSS (without Ca2+/Mg2+) was used as a paracellular permeability enhancer to modulate the tight junction proteins. The solution containing EDTA was applied both to the apical and basolateral sides of cell monolayers for 5 min at 37°C to open the tight junctions transiently. After EDTA treatment, the solution was removed immediately and the cells were washed twice with HBSS containing Ca2+/Mg2+. The bidirectional flux of EFdA and LY after alteration of the tight junction barrier was also conducted as described above.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by Student’s t-test for two groups. All results were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. A P value < 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Bidirectional flux of in Caco-2 cell monolayers

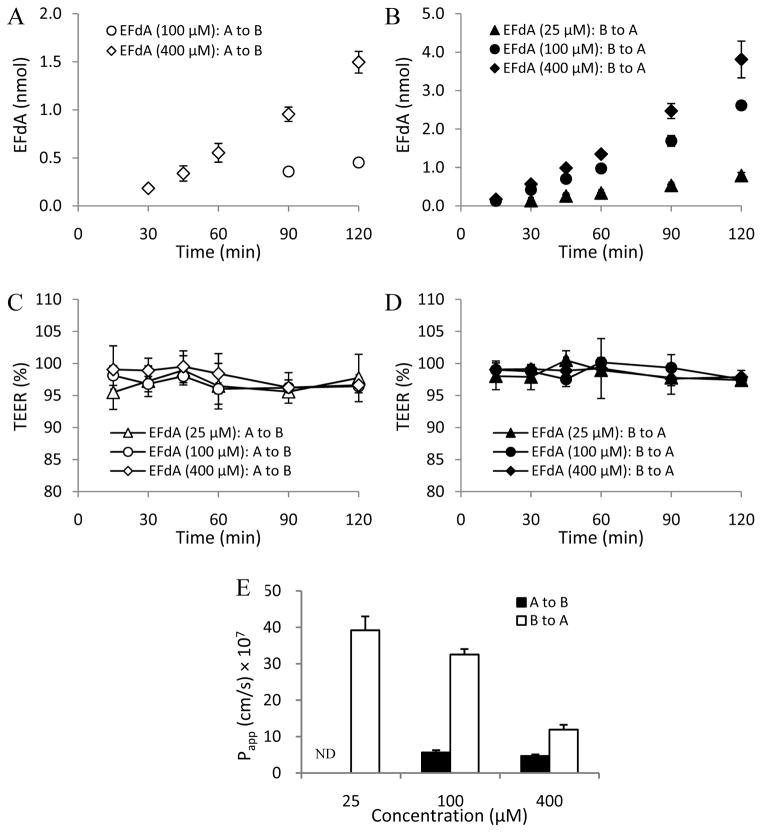

Figs. 1A and 1B show the linear transport profiles of EFdA across the Caco-2 cell monolayers from either the (a–b) or the (b-a) side. Interestingly, the cumulative transported amounts of EFdA among the concentration groups were much higher in the (b-a) direction than in the (a–b) direction. As shown in Figs. 1C and 1D, no obvious change in TEER value was observed among the concentration groups of EFdA during the 2h experimental exposure, suggesting the integrity of the cell monolayers. It is noteworthy that the Papp (b-a) values for EFdA in the medium (100 μM) and high (400 μM) concentration groups were found to be much higher than those of Papp (a–b) (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1E). Due to a limitation of the analytical method (Figs. 1A and 1E), Papp (a–b) values for EFdA in the low (25 μM) concentration group could not be obtained.

Fig. 1.

EFdA transport from apical to basolateral [A to B] and from basolateral to apical [B to A] in Caco-2 monolayers at different concentrations (A and B); TEER measurement over 2h in Caco-2 monolayers during the apical to basolateral (C) and basolateral to apical (D) flux of EFdA; Papp values obtained from bidirectional flux of EFdA across Caco-2 monolayers at different concentrations (E) (n = 3). ND denotes not detectable.

It was also found that the efflux ratios for the medium and high concentration groups of EFdA decreased from 5.7 to 2.5 as the concentration of EFdA increased from 100 to 400 μM, suggesting the possibility of a saturable process for the transport of EFdA. Additionally, the high efflux ratio (> 2) observed in this study suggested that EFdA may be a substrate for efflux transporters overexpressed on the apical side of Caco-2 cells, such as PGP1, which can participate in the efflux process, resulting in lower concentrations of EFdA in the receptor compartment (The International Transporter Consortium, 2010).

3.2. In vitro cytotoxicity

EFdA and two well-known PGP1 inhibitors (quinidine and ivermectin) were tested with MTT assay for possible cytotoxic effects in MDCKII and PGP1 overexpressing MDCKII cell lines. The test compounds were dissolved in DMSO. The DMSO concentration in the assays never exceeded 1% (v/v), a concentration which was not found to impact the results of the assays (Storch et al., 2007). The half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values obtained for each test compound are shown in Table 1. Only concentrations below the IC50 were acceptable for use in further PGP1 inhibition studies. Therefore, 0.005–200 μM, 0.005–100 μM and 0.005–10 μM were used as the test concentrations for EFdA, quinidine and ivermectin, respectively.

Table 1.

IC50 values of quinidine, ivermectin and EFdA in MDCKII and PGP1 overexpressing MDCKII cells (n = 8).

| Compound | IC50 (μM) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| MDCKII | PGP1 overexpressing MDCKII | |

|

|

||

| Quinidine | 267.37 ± 89.11 | 102.77 ± 29.43 |

| Ivermectin | 20.01 ± 2.91 | 12.20 ± 0.87 |

| EFdA | 377.21 ± 79.47 | 484.59 ±49.09 |

3.3. PGP1 inhibition

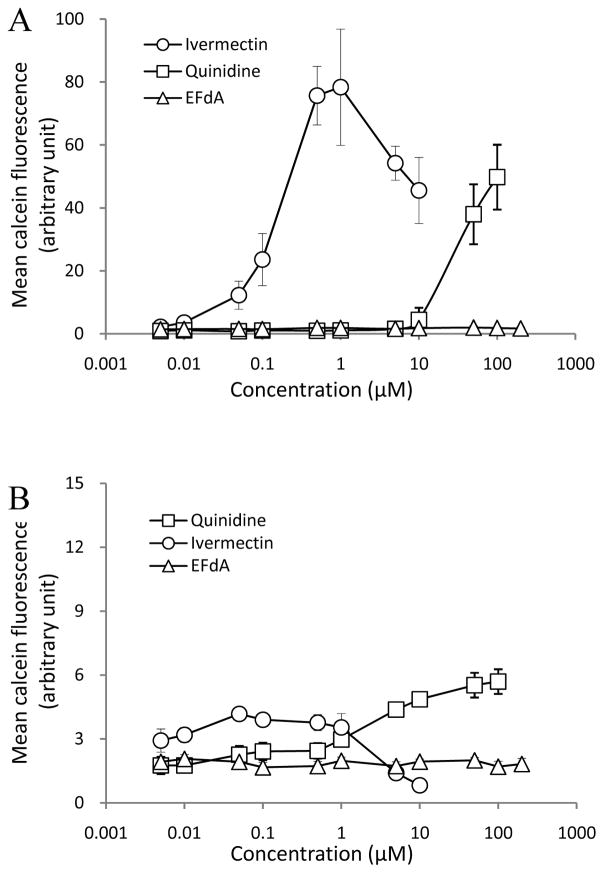

As shown in Fig. 1E, a net flux ratio of EFdA > 2 was found in the bidirectional flux assay in Caco-2 cell monolayers. In order to investigate whether EFdA is a potential PGP1 substrate, a PGP1 inhibition study was conducted using calcein-AM as the molecular probe. Quinidine and ivermectin (well-known PGP1 inhibitors) were used as the positive controls. Calcein-AM is a highly lipophilic dye that rapidly penetrates the plasma membrane. Inside the cell, endogenous esterases cleave the ester bonds, producing a hydrophilic and fluorescent dye, calcein, which cannot leave the cell via the plasma membrane due to its the high hydrophilicity. Since calcein-AM is a known substrate of PGP1 and calcein is not a PGP1 substrate, cells overexpressing high levels of PGP1 rapidly extrude non-fluorescent calcein-AM from the plasma membrane, thus preventing accumulation of fluorescent calcein inside the cytosol (Holló et al., 1996). Moreover, the calcein fluorescence is bright, insensitive to pH or Ca2+ and Mg2+ concentrations, and generally not susceptible to quenching (Homolya et al., 1996). We also confirmed that none of the three compounds used in the present study (EFdA, quinidine, and ivermectin) were subject to quenching over the concentration range tested (data not shown).

As depicted in Fig. 2A, a concentration-dependent PGP1 inhibitory effect was observed for quinidine and ivermectin in PGP1 overexpressing MDCKII cells, as evidenced by the increase in calcein fluorescence with increasing concentrations of PGP1 inhibitors. While some decline in fluorescence was noted at the highest doses of ivermectin, this was probably due to compound-induced cytotoxicity at these levels (Figs. 2A and 2B). However, EFdA showed no inhibition of PGP1 in PGP1 overexpressing MDCKII cells (Fig. 2A), suggesting that EFdA was not a substrate of PGP1. Additionally, as for the control groups, no obvious PGP1 inhibitory response was observed for quinidine and ivermectin in MDCKII cells because of the absence of PGP1 expression (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Concentration dependent effects of quinidine, ivermectin and EFdA on calcein fluorescence in PGP1 overexpressing MDCKII (A) and MDCKII cells (B) (n = 8).

3.4. Bidirectional flux of EFdA and LY in MDCKII monolayers

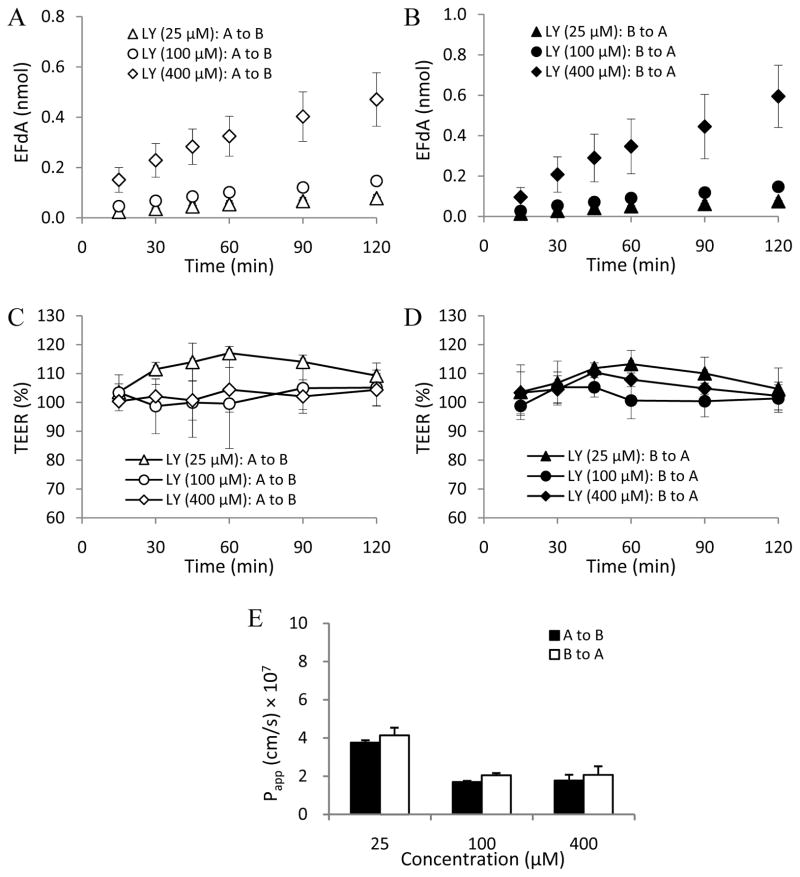

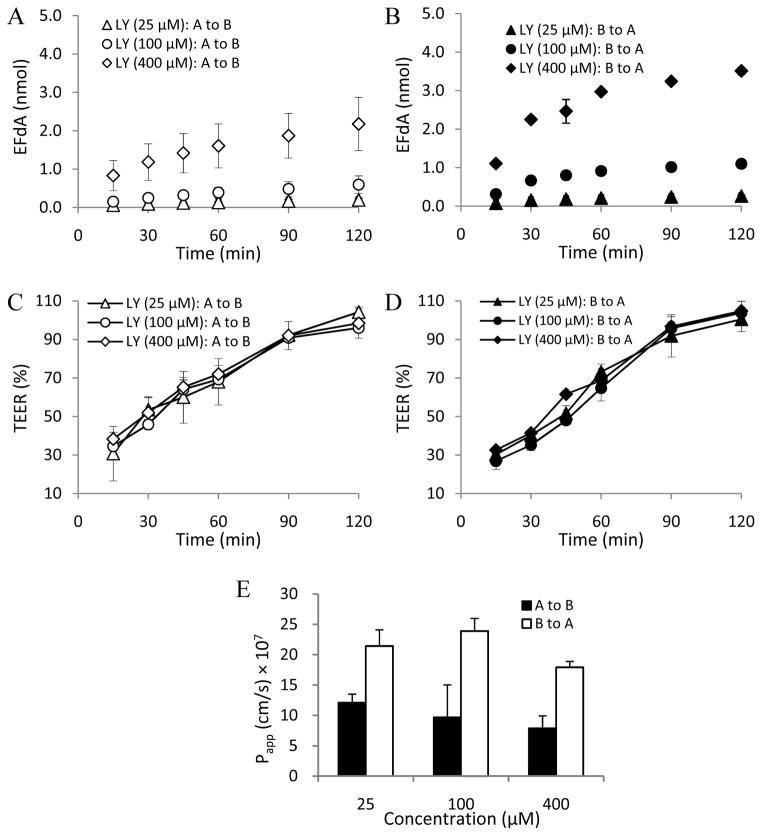

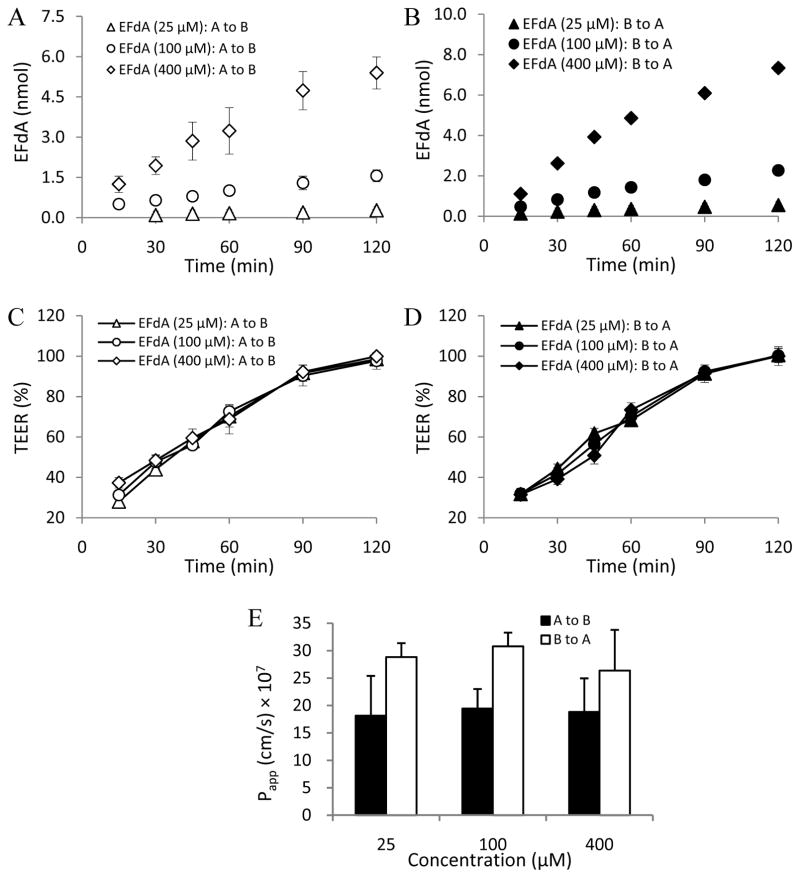

In this study, MDCKII cell monolayers were used as an in vitro cell model to investigate the EFdA paracellular permeability profile (Angelow et al., 2006; Fisher et al., 2010). LY (Mw: 457.2 Da), a known hydrophilic fluorescent paracellular marker (Inokuchi et al., 2009; Coyuco et al., 2011), was used as the positive control. As shown in Figs. 3C, 3D, 4C and 4D, no obvious change in TEER value was observed in the different concentration groups of EFdA and LY in the absence of EDTA treatment during the 2h experimental exposure, indicating the integrity of MDCKII cell monolayers.

Fig. 3.

LY flux across MDCKII monolayers from apical to basolateral [A to B] and from basolateral to apical [B to A] in the absence of EDTA treatment at different concentrations (A and B); TEER measurement over 2h in MDCKII monolayers during the apical to basolateral (C) and basolateral to apical (D) flux of LY in the absence of EDTA treatment; Papp values obtained from bidirectional flux of LY across MDCKII monolayers in the absence of EDTA treatment at different concentrations (E) (n = 3).

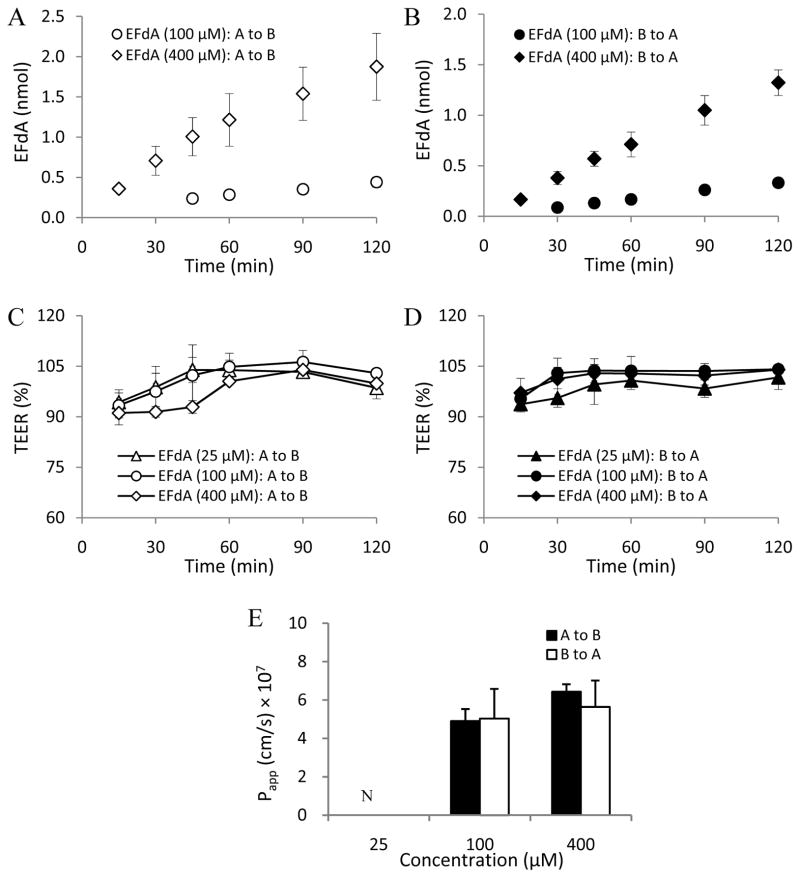

Fig. 4.

EFdA flux across MDCKII monolayers from apical to basolateral [A to B] and from basolateral to apical [B to A] in the absence of EDTA treatment at different concentrations (A and B); TEER measurement over 2h in MDCKII monolayers during the apical to basolateral (C) and basolateral to apical (D) flux of EFdA in the absence of EDTA treatment; Papp values obtained from bidirectional flux of EFdA across MDCKII monolayers in the absence of EDTA treatment at different concentrations (E) (n = 3). ND denotes not detectable.

In order to investigate the potential paracellular permeability of EFdA, EDTA (5 μM) was used to transiently open the functional barrier of tight junctions (Ménez et al., 2007). After exposure of both apical and basolateral sides of MDCKII cell monolayers to 5 μM EDTA in HBSS without Ca2+/Mg2+ for 5 min at 37°C, the TEER at 15 min decreased to about 30% in all tested groups and then reverted to the normal level gradually within 2 h in both LY and EFdA treatment groups, suggesting the reversibility of tight junction function in the cell monolayers and the safe concentration of EDTA applied (Figs. 5C and 5D; Figs. 6C and 6D).

Fig. 5.

LY flux across MDCKII monolayers from apical to basolateral [A to B] and from basolateral to apical [B to A] in the presence of EDTA treatment at different concentrations (A and B); TEER measurement over 2h in MDCKII monolayers during the apical to basolateral (C) and basolateral to apical (D) flux of LY in the presence of EDTA treatment; Papp values obtained from bidirectional flux of LY across MDCKII monolayers in the presence of EDTA treatment at different concentrations (E) (n = 3).

Fig. 6.

EFdA flux across MDCKII monolayers from apical to basolateral [A to B] and from basolateral to apical [B to A] in the presence of EDTA treatment at different concentrations (A and B); TEER measurement over 2h in MDCKII monolayers during the apical to basolateral (C) and basolateral to apical (D) flux of EFdA in the presence of EDTA treatment; Papp values obtained from bidirectional flux of EFdA across MDCKII monolayers in the presence of EDTA treatment at different concentrations (E) (n = 3).

Papp (a–b) values of LY without EDTA treatment for the three concentration groups (25, 100, and 400 μM) were (3.76 ± 0.12) × 10−7cm/s, (1.70 ± 0.06) × 10−7cm/s, and (1.77 ± 0.31) × 10−7cm/s, respectively. The corresponding Papp (b-a) values of LY were found to be (4.14 ± 0.40) × 10−7cm/s, (2.05 ± 0.12) × 10−7cm/s, and (2.07 ± 0.46) × 10−7cm/s, respectively. We found that the Papp (a–b) or (b-a) values of LY for the three concentration groups increased from 3.2 to 11.6 times after EDTA treatment compared to the non-EDTA treatment groups (Figs. 3 and 5), confirming that LY is a good paracellular permeability marker.

As illustrated in Figs. 4 and 6, a similar EDTA-dependent permeability profile was observed for EFdA. As for the low concentration group (25 μM) of EFdA in the absence of EDTA treatment, none of the drug substance was detected in the donor and receptor compartment because of the limitation of detection of the analytical method (Figs. 4A and 4B). However, in the presence of EDTA treatment, Papp (a–b) and (b-a) values of EFdA in the low concentration group (25 μM) were found to be (1.82 ± 0.73) × 10−6 cm/s and (2.88 ± 0.26) × 10−6 cm/s, respectively, indicating that many more EFdA molecules permeated through MDCKII cell monolayers after the transient opening of tight junctions (Figs. 4A and 4B; Figs. 6A and 6B). Moreover, we found that the Papp values of EFdA for the medium (100 μM) and high (400 μM) concentration groups increased 2.9 to 6.1 times after EDTA treatment compared to the non-EDTA treatment groups (Fig. 2D). In addition, Papp (a–b) and (b-a) values for EFdA in the medium (100 μM) and high (400 μM) concentration groups without EDTA treatment were found to be nearly 2.5 to 3.5 times higher than those of LY (P < 0.05), probably attributable to the smaller molecular weight of EFdA as compared to LY (293.3 vs. 457.2).

The significant increase in EFdA flux with a concomitant increase in LY flux was observed when the bidirectional experiment was conducted in the presence of EDTA. This is indicative of paracellular passive diffusion as the primary pathway for the permeability of EFdA across the cell monolayers (Gan et al., 2008).

4. Discussion

Since the emergence of multidrug resistance during HAART in clinical trials, new treatment options for salvage therapy are of considerable importance and novel anti-HIV agents with unique mechanisms of action are greatly needed (Hughes et al., 2008). So far, all FDA-approved NRTIs are nucleoside analogs lacking a 3′-hydroxyl group. Thus upon incorporation of an NRTI into growing viral DNA, further DNA chain extension is terminated (Sohl et al., 2012).

We have been evaluating a novel experimental NRTI, EFdA, which possesses a 3′-hydroxyl moiety yet functions as a chain terminator by a novel mechanism of action (Michailidis et al., 2009). EFdA thus may be a very promising drug candidate for use both in HIV therapeutic and prevention modalities. Since EFdA works by interfering with the viral replication cycle, it should be noted that EFdA needs to permeate across the intestinal, vaginal, cervical or rectal epithelial barrier and reach the underlying target cell populations to take pharmacological action after systemic or topical delivery. Thus, it is important to understand the mechanism of EFdA transport across epithelial cells.

In our previous preformulation study, the solubility of EFdA was found to be pH dependent. An increase in pH from 3 to 6 resulted in a significant decrease in EFdA solubility (from 1508.7 to 799.2 μg/ml), while no obvious change in solubility was observed for EFdA with pH from 6 to 9. We therefore investigated the effect of intestinal pH (from 5.5 to 7.4) on the transport of EFdA across the Caco-2 monolayers. We found that the transport of EFdA was independent of pH within the range studied (Zhang et al., 2013). Thus, the pH of the apical and basolateral medium in the bidirectional flux of EFdA across Caco-2 monolayers was maintained at 7.4 in this study.

Our results confirmed that the high efflux ratio of EFdA found in the bidirectional flux assay in Caco-2 cell monolayers is more than likely to be due to factors other than PGP1-mediated efflux given the lack of observed PGP1 inhibitory effect for EFdA in PGP1 overexpressing MDCKII cells, even at the concentration of 200 μM. The data presented suggest that there is active transport of EFdA from the Caco-2 cell monolayers tested that cannot be explained by PGP1- mediated efflux. Other mechanisms might be involved in the transport of EFdA across the Caco-2 cell monolayers.

It is well known that nucleoside transporter systems are generally divided into two classes (Kong et al., 2004): human equilibrative nucleoside transporters (ENT) and concentrative nucleoside transporters (CNT). The former are responsible for the facilitated diffusion of physiologic nucleosides and comprise four isoforms (ENT 1–4). The latter are sodium-dependent active transport systems and comprise three isoforms (CNT 1–3). Because some nucleosides and their derivatives are hydrophilic, their availability within cells and in the extracellular environment can be facilitated by nucleoside transporter proteins such as CNT and ENT (Young et al., 2013). It has also been reported that CNT and ENT are ubiquitously expressed on intestinal cells and transport some nucleoside analogs, such as NRTIs (Kis et al., 2009). For example, transport of zidovudine and lamivudine by CNT1 and ENT2 has been demonstrated in vitro (Cano-Soldado et al., 2004; Yao et al., 2001). EFdA is a nucleoside analog with reported potent activity against diverse wild-type and drug-resistant HIV-1 strains in vitro (Michailidis et al., 2009 and 2013). ENT1 and ENT2 have been found to be expressed in Caco-2 cell monolayers (Sun et al., 2003; Ward et al., 1999; Phua et al., 2013), which might be related to the transport of EFdA from the basolateral to the apical side across Caco-2 cell monolayers.

Although some limitations exist, the paracellular transport route plays an important role in the oral absorption of hydrophilic compounds such as some nutrients and many small, water-soluble drugs which are not actively transported by carrier-mediated pathways (Zhou et al., 1999). The average molecular size cutoff for the paracellular route of passive diffusion is approximately 500 Da (He et al., 1998).

Thus, based on our previous preformulation data for EFdA (solubility in water: 1mg/ml; Log Po/w: −1.2; Papp obtained from three separate human ectocervical tissues: < 1 × 10−6 cm/s) (Zhang et al., 2013), we hypothesized that EFdA will permeate across intestinal epithelial cells by the paracellular route. To this end, we applied EDTA, a known modulator of paracellular permeability via the opening of tight junctions, in our bidirectional flux study of EFdA and LY. Given the similarity in permeation profiles observed between EFdA and LY, with or without cell exposure to EDTA (Figs. 3–6), EFdA flux across the cell monolayers was, at least in part, due to the simple passive diffusion through the paracellular route. This is inferred due to the fact that EDTA treatment has no influence on the transcellular flux of lipophilic compounds (Ménez et al., 2007) while small hydrophilic solutes primarily permeate through the paracellular pathway, which consists of small aqueous channels and pores within the discontinuous or interrupted lipid membrane (Sassi et al., 2004). Additionally, as shown in Fig. 4, efflux ratios for EFdA at different concentrations in MDCKII cell monolayers, in the absence of EDTA treatment, were found to be about 1.0, indicating no involvement of active transport in the MDCKII cell monolayers. Surprisingly, after EDTA treatment, the efflux ratios for both EFdA and LY became higher in all test groups compared to those of non-EDTA treatment groups (Figs. 5E and 6E). This observation is consistent with previous results showing permeation of hydrophilic compounds through epithelial monolayers to be enhanced by basolateral application of EDTA as opposed to apical application (Noach et al., 1993), which is probably due to differences in the structure of tight junctional proteins on apical and basolateral sides of cell monolayers (Noach et al., 1993; El-Sayed et al., 2003).

Taken together, our studies suggest that active transport processes may play some role in the transport of EFdA in Caco-2 cell monolayers. However, PGP1 inhibition studies using MDCKII and PGP1 overexpressing MDCKII cells suggest that EFdA is not a substrate of PGP1. Additionally, it was found that EFdA permeates across cell monolayers such as MDCKII primarily by the paracellular route.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported, in part, by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI076119, AI079801, and TR000146). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors also would like to acknowledge Bruce Campbell for his detailed and helpful comments to the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Angelow S, Kim KJ, Yu AS. Claudin-8 modulates paracellular permeability to acidic and basic ions in MDCKII cells. J Physiol. 2006;571:15–26. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.099135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benet LZ, Wu CY, Hebert MF, Wacher VJ. Intestinal drug metabolism and antitransport process: a potential paradigm shift in oral drug delivery. J Control Release. 1996;39:139–143. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdet DL, Pollack GM, Thakker DR. Intestinal absorptive transport of the hydrophilic cation ranitidine: a kinetic modeling approach to elucidate the role of uptake and efflux transporters and paracellular vs. transcellular transport in Caco-2 cells. Pharm Res. 2006;23:1178–1187. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-0204-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano-Soldado P, Lorráyoz IM, Molina-Arcas M, Casado FJ, Martinez-Picado J, Lostao MP, Pastor-Anglada M. Interaction of nucleoside inhibitors of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase with the concentrative nucleoside transporter-1 (SLC 28A1) Antivir Ther. 2004;9:993–1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyuco JC, Liu YJ, Tan BJ, Chiu GN. Functionalized carbon nanomaterials: exploring the interactions with Caco-2 cells for potential oral drug delivery. Int J Nanomedicine. 2011;6:2253–2263. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S23962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deli MA. Potential use of tight junction modulators to reversibly open membranous barriers and improve drug delivery. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1788:892–910. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sayed M, Rhodes CA, Ginski M, Ghandehari H. Transport mechanisms of poly (amidoamine) dendrimers across Caco-2 cell monolayers. Int J Pharm. 2003;265:151–157. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(03)00391-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher SJ, Swaan PW, Eddington ND. The ethanol metabolite acetaldehyde increase paracellular drug permeability in vitro and oral bioavailability in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;332:326–333. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.158642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan LS, Niederer T, Eads C, Thakker D. Evidence for predominantly paracellular transport of thyrotropiin-releasing hormone across Caco-2 cell monolayers. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;197:771–777. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori S, Ide K, Nakata H, Harade H, Suzu S, Ashida N, Kohgo S, Hayakawa H, Mitsuya H, Okada S. Potent activity of a nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, 4′-ethynyl-2-fluoro-2′-deoxyadenosine, against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in a model using human peripheral blood mononuclear cell-transplanted Nod/SCID janus kinase 3 knockout mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:3887–3893. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00270-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He YL, Murby S, Warhurst G, Gifford L, Walker D, Ayrton J, Eastmond R, Rowland M. Species differences in size discrimination in the paracellular pathway reflected by oral bioavailability of poly (ethylene glycol) and D-peptides. J Pharm Sci. 1998;87:626–633. doi: 10.1021/js970120d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holló Z, Homolya L, Hegedus T, Sarkadi B. Transport properties of the multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRP) in human tumour cells. FEBS Lett. 1996;383:99–104. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homolya L, Holló Z, Müller M, Mechetner EB, Sarkadi B. A new method for quantitative assessment of P-glycoprotein-related multidrug resistance in tumor cells. Br J Cancer. 1996;73:849–855. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes A, Barber T, Nelson M. New treatment options for HIV salvage patients: an overview of second generation PIs, NNTRIs, integrase inhibitors and CCR5 antagonists. J Infect. 2008;57:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inokuchi H, Takuto T, Aikawa K, Shimizu M. The effect of hyperosmosis on paracellular permeability in Caco-2 cell monolayers. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2009;73:80538-1-7. doi: 10.1271/bbb.80538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto A, Kodama E, Sarafianos SG, Sakagami Y, Kohgo S, Kitano K, Ashida N, Iwai Y, Hayakawa H, Nakata H, Mitsuya H, Arnold E, Matsuoka M. 2′-Deoxy-4′-C-ethynyl-2-halo-adenosines active against drug-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:2410–2420. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kis O, Robillard K, Chan GN, Bendayan R. The complexities of antiretroviral drug-drug interactions: role of ABC and SLC transporters. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;31:22–25. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong W, Engel K, Wang J. Mammalian nucleoside transporters. Curr Drug Metab. 2004;5:63–84. doi: 10.2174/1389200043489162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ménez C, Buyse M, Dugave C, Farinotti R, Barratt G. Intestinal absorption of miltefosine: contribution of passive paracellular. Pharm Res. 2007;24:546–554. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9170-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michailidis E, Marchand B, Kodama EN, Singh K, Matsuoka M, Kirby KA, Ryan EM, Sawani AM, Nagy E, Mitsuya H, Parniak MA, Sarafianos SG. Mechanism of inhibition of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase by 4′-ethynyl-2-fluoro-2′-deoxyadenosine triphosphate, a translocation defective reverse transcriptase inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:35681–35691. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.036616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michailidis E, Singh K, Ryan EM, Hachiya A, Ong YT, Kirby KA, Marchand B, Kodama EN, Mitsuya H, Parniak MA, Sarafianos SG. Effect of translocation defective reverse transcriptase inhibitors on the activity of N3481, a connection subdomain drug resistant HIV-1 reverse transcriptase mutant. Cell Mol Biol. 2013;58:187–195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphey-Corb M, Rajakumar P, Michael H, Nyaundi J, Didier PJ, Reeve AB, Mitsuya H, Sarafianos SG, Parniak MA. Response of simian immunodeficiency virus to the novel nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor 4′-ethynyl-2-fluoro-2′-deoxyadenosine in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:4707–4712. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00723-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakata H, Amano M, Koh Y, Kodama E, Yang G, Bailey CM, Kohgo S, Hayakawa H, Matsuoka M, Anderson KS, Cheng YC, Mitsuya H. Activity against human immunodeficiency virus type 1, intracellular metabolism, and effects on human DNA polymerases of 4′-ethynyl-2-fluoro-2′-deoxyadenosine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:2701–2708. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00277-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noach ABJ, Kurosaki Y, Blom-Roosemalen MCM, de Boer AG, Breimer DD. Cell-polarity dependent effect of chelation on the paracellular permeability of confluent Caco-2 cell monolayers. Int J Pharm. 1993;90:229–237. [Google Scholar]

- Phua LC, Mal M, Koh PK, Cheah PY, Chan ECY, Ho HK. Investigating the role of nucleoside transporters in the resistance of colorectal cancer to 5-fluorouracil therapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;71:817–823. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-2054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassi AB, Mccullough KD, Cost MR, Hillier SL, Rohan LC. Permeability of tritiated water through human cervical and vaginal tissue. J Pharm Sci. 2004;93:2009–2016. doi: 10.1002/jps.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohl CD, Singh K, Kasiviswanathan R, Copeland WC, Mitsuya H, Sarafianos SG, Anderson KS. Mechanism of interaction of human mitochondrial DNA polymerase γ with the novel nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor 4′-ethynyl-2-fluoro-2′-deoxyadenosine indicates a low potential for host toxicity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1630–1634. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05729-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch CH, Theile D, Lindenmaier H, Haefeli WE, Weiss J. Comparison of the inhibitory activity of anti-HIV drugs on P-glycoprotein. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2007;73:1573–1581. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D, Lennernas H, Welage LS, Barnett JL, Landowski CP, Foster D, Fleisher D, Lee KD, Amidon GL. Comparison of human duodenum and Caco-2 gene expression profiles for 12,000 gene sequences tags and correlation with permeability of 26 drugs. Pharm Res. 2002;19:1400–1416. doi: 10.1023/a:1020483911355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The International Transporter Consortium. Membrane transporters in drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:215–236. doi: 10.1038/nrd3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. Global Report: UNAIDS report on the Global AIDS Epidemic 2012. UNAIDS; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ward JL, Tse CM. Nucleoside transport in human colonic epithelial cell lines: evidence foe two Na+-independent transport systems in T84 and Caco-2 cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1419:15–22. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss J, Dormann S-MG, Martin-Facklam M, Kerpen CJ, Ketabi-Kiyanvash N, Haefeli WE. Inhibition of P-glycoprotein by newer antidepressants. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305:197–204. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.046532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao SY, Ng AM, Sundaram M, Cass CE, Baldwin SA, Young JD. Transport of antiviral 3′-deoxy-nucleoside drugs by recombinant human and rat equilibrative, nitrobenzylthioinosine (NBMPR)-insensitive (ENT2) nucleoside transporter proteins produced in xenopus oocytes. Mol Memr Biol. 2001;18:161–167. doi: 10.1080/09687680110048318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JD, Yao SY, Baldwin JM, Cass CE, Baldwin SA. The human concentrative and equilibrative nucleoside transporter families, SLC28 and SLC29. Mol Aspects Med. 2013;34:529–547. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Parniak MA, Mitsuya H, Sarafianos SG, Graebing PW, Rohan LC. Preformulation studies of EFdA, a novel nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor for HIV prevention. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2013 doi: 10.3109/03639045.2013.809535. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou SY, Piyapolrungroj N, Pao L, Li C, Liu G, Zimmermann E, Fleisher D. Regulation of paracellular absorption of cimetidine and 5-amino salicylate in rat intestine. Pharm Res. 1999;99:2166–2175. doi: 10.1023/a:1018974519984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]