Abstract

Oxidative stress plays an important role in the development of various disease processes and is a putative mechanism in the development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), the most common complication of extreme preterm birth. Glutathione, a major endogenous antioxidant and redox buffer, also mediates cellular functions through protein thiolation. We sought to determine if post-translational thiol modification of hemoglobin F occurs in neonates by examining erythrocyte samples obtained during the first month of life from premature infants, born at 23 0/7 - 28 6/7 weeks gestational age, who were enrolled at our center in the Prematurity and Respiratory Outcomes Program (PROP). Using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) we report the novel finding of in vivo and in vitro glutathionylation of γG and γA subunits of Hgb F. Through tandem mass spectrometry (nanoLC-MS/MS), we confirmed the adduction site as the Cys-γ94 residue and through high-resolution mass spectrometry determined that the modification occurs in both γ subunits. We also identified glutathionylation of the β subunit of Hgb A in our patient samples; we did not find modified α subunits of Hgb A or F. In conclusion, we are the first to report that glutathionylation of γG and γA of Hgb F occurs in premature infants. Additional studies of this post-translational modification are needed to determine its physiologic impact on Hgb F function and if sG-Hgb is a biomarker for clinical morbidities associated with oxidative stress in premature infants.

Keywords: glutathionylation, hemoglobin F, LC-MS, high resolution tandem MS, NanoLC-MS/MS, hemoglobin A, prematurity, oxidative stress

Introduction

Alterations in redox homeostasis can impact disease processes in adults and developing newborns. Oxidative stress is characterized by an imbalance between cellular prooxidants and antioxidant capacity resulting in production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Glutathione (γ-L-glutamyl-L-cysteinylglycine) is the main non-enzymatic intracellular antioxidant. It exists primarily in its reduced state (GSH) but also in an oxidized dimeric form (GSSG). The GSH/GSSG buffer system regulates cellular homeostasis and is believed to play an important role in protein synthesis and signal transduction through post-translational protein modifications1. There is evidence to suggest that protein glutathionylation is a reversible process, thereby serving as a protective mechanism against irreversible oxidation of regulatory thiol residues that may occur under conditions where redox homeostasis is altered1-6. However, it is unclear if this modification is protective or detrimental in conditions associated with whole-body oxidative stress1,6-8.

It has been demonstrated using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) that adult hemoglobin (Hgb A) in the presence of excess GSSG is glutathionylated in vitro at the Cys-β93 residue and that these levels increase in a more oxidized environment9,10. This spontaneous, covalent modification between sulfides has been observed to increase oxygen affinity, reduce cooperativity, and reduce the alkaline Bohr effect of Hgb A resulting in decreased oxygen delivery11,12. In sickle cell disease, glutathionylation of Hgb S has a potent anti-sickling effect on erythrocytes9. Several recent reports have found that levels of glutathionylated Hgb are increased in patients with hyperlipidemia, diabetes11,13, uremia undergoing dialysis14, and Friedreich's ataxia15 compared to healthy adults, suggesting that glutathionylated Hgb A may serve as a potential biomarker of oxidative stress.

Premature infants are at an especially increased risk for redox imbalance as a result of administration of supplemental oxygen, immature antioxidant defenses, infant and maternal infection and inflammation, and free iron, all of which contribute to a more oxidative state16,17. Reactive oxygen species generated as a result of redox imbalance cause reversible glutathionylation and uncoupling of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), thereby reducing the bioavailability of nitric oxide (NO), an important molecule involved in fetal and newborn lung development and function5. Oxidative stress is a putative mechanism in the development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) or chronic lung disease of prematurity, the most common complication of extreme preterm birth. Infants with BPD have increased mortality and long-term respiratory and neurologic morbidities compared with infants of comparable gestational age without BPD18,19.

Unlike in adults, the blood of premature infants is composed primarily of fetal hemoglobin (Hgb F). Hgb F exhibits a distinctively higher affinity for oxygen than Hgb A thereby facilitating delivery of O2 across the placenta to fetal red blood cells. Alterations in redox balance towards a more oxidized state could potentially result in modifications of Hgb F by glutathionylation in a manner similar to Hgb A and S. To date there are no in vivo studies that demonstrate if Hgb F is glutathionylated or if it may serve as a potential biomarker for oxidative stress in extremely premature infants.

We have developed an LC-MS method for the detection of glutathionylated Hgb F and Hgb A obtained from whole blood of premature infants, involving HPLC separation of intact protein isoforms and numerical deconvolution of the multiple charge state mass spectral information. Furthermore, we have utilized a tandem mass spectrometry approach to show that glutathionylation of Hgb F occurs (both in vitro and in vivo) on the lone cysteine-containing γG and γA subunits of Hgb F.

EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

Subjects

IRB approval was obtained for collection of all human blood samples. Informed consent was obtained from parents of 108 premature infants, 23 0/7 - 28 6/7 weeks gestational age, who were enrolled in the Prematurity and Respiratory Outcomes Program (PROP), a multicenter study funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The blood samples were obtained twice during the first post-natal week after study enrollment and at 14 and 28 days.

Preparation and Processing of Human Blood Samples

Premature infants’ blood (2.5 mL) was collected in an EDTA polypropylene tube and placed on ice for immediate processing. A 15 uL aliquot of whole blood was diluted in 485 uL of distilled/deionized water to lyse the red blood cells, and then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at room temperature to remove cellular debris. The supernatant (hemolysate) was transferred to a clean polypropylene microcentrifuge tube and placed on ice for immediate LC-MS analysis or stored at -80 °C in ~100 uL aliquots until analysis (no longer than one month). If hemolysate sample had been frozen, it was thawed at room temperature for 10-15 minutes and gently vortexed prior to further processing. Next, hemolysate (20 uL) was diluted to 100 uL with reconstitution solvent [water:acetonitrile (98:2) containing 0.2% acetic acid], and transferred into a 250 uL polypropylene polyspring insert in a 2 mL clear silanized glass autosampler vial (National Scientific, Rockwood, TN). Samples were vortexed and placed in the autosampler at 5 °C and analyzed within one hour.

Hemoglobin Incubated with Oxidized Glutathione

An aliquot (100 uL) of a hemolysate sample was spiked with 4 mM GSSG. The reaction mixture was vortexed and placed in an incubator at 37 °C. At various time points (up to 7 days), a subsample of 20 uL was extracted after gentle vortexing and added to 80 uL reconstitution solvent and placed in the autosampler for immediate analysis via LC-MS.

Reduction of Glutathionylated Hemoglobin

Hemolysate samples incubated with GSSG (as described above) were spiked with 45 or 100 mM DTT, gently vortexed and allowed to stand at room temperature to reduce disulfide bonds. At 15 min and 60 min, the samples were gently vortexed and 40 uL were added to 60 uL of reconstitution solvent, vortexed again and then placed in the autosampler for immediate analysis via LC-MS.

LC-coupled ESI-MS Analysis of Hgb

Routine LC-MS analyses were performed on a Waters Synapt Q-TOF instrument. LC analyses were carried out using a Waters Acquity UPLC (Waters Corp., Milford, MA) system consisting of a binary solvent manager, refrigerated sample manager, and a thermostated column heater. The LC system was equipped with a Waters Symmetry Shield 300™ C18 3.5um reverse phase column, 2.1 × 100 mm. Mobile phases consisted of 0.05% TFA (v/v) and 0.2% formic acid (v/v) in solution A (H2O/CH3CN, 90:10) and in solution B [2-Propanol/CH3CN/H2O (50:40:10)]. The flow rate was set to 300 uL/min. The column was not thermostated. Gradient conditions were as follows: 0-1 min, 0% B; 1-13 min, 0-100% B; 13-15 min, 100% B; 15-16 min, 100-0% B; 16-20 min, 0% B. The total run time per sample was 20 min. The injection volume for all samples was 10 μL each. The autosampler injection valve and sample injection needle were flushed and washed sequentially with mobile phase B (1 mL) and mobile phase A (1.5 mL) between each injection. Thorough cleaning of the injection system and column with mobile phase B was done daily prior to analysis. The autosampler tray was maintained at 5 °C.

For routine analysis of patient samples, full scan mass spectrometric detection was performed using a Waters Synapt, quadrupole/oa-Tof high-resolution mass spectrometer equipped with a dual channel ESI ion source. The instrument was calibrated weekly over a mass range of m/z 500 to m/z 3000 with a solution of sodium iodide using the manufacturer's recommended calibration procedure. CHAPS (m/z = 615.4037) was used as a lock channel mass. The MS conditions were as follows: positive ionization mode, desolvation gas (N2) 800 L/h at 350 °C, capillary voltage 2.25 kV, sampling cone voltage 40 V, extraction cone voltage 4 V, source temperature 125°C. The instrument was operated in the V-mode, with a nominal mass resolution of 10,000 [(peak width at half-height)−1 × m/z]. The mass spectral acquisition was performed at a scan speed of 2 s with a mass range of m/z 500 - 3000. Deconvolution of the ESI charge state mass spectra of the intact proteins was performed using the MaxEnt 1 algorithm in the MassLynx software (output range 14,800 – 16,400 Da, input range of m/z 650 – 1200 with a resolution 0.20 Da/channel). Data collection and processing were controlled by MassLynx V4.1 SCN639 software (Waters Corp.). The levels of glutathionylated hemoglobin (sG-Hgb) subunits were expressed as a ratio (percentage) of the peak height (spectral counts per second) of the modified form to that of the native hemoglobin subunit based on the following equation: Relative Intensity (RI) % = (sG-Hgb subunit spectral intensity / native Hgb subunit spectral intensity) × 100 %.

Ultra High-Resolution LC-MS Analysis of Intact Hgb F

For accurate mass assignments of intact Hgb gamma subunits, 20 uL of hemolysate was loaded onto reverse-phase C18 UPLC column (Acquity BEH300, 1.7 μm, 2.1 × 50mm). Gradient conditions were as follows: 0-1 min, 0% B; 1-20 min, 0-100% B. Eluted proteins were mass analyzed on a LTQ Orbitrap mass spectrometer, equipped with a standard electrospray ionization source (Thermo Scientific).

Full scan spectra of 2000-3000 m/z were acquired in positive ion FTMS mode (three microscans, resolution 100,000) with a skimmer offset (source CID) of 10 V. The full scan MS AGC target value in the Orbitrap was set to 1 × e6, the maximum inject time was 500 ms. The Orbitrap was calibrated daily over a mass range of 100-3000 using a solution of cesium iodide (0.5 mg/mL in i-PrOH/H2O).

NanoLC-MS/MS Proteomic Analysis of Digested Hgb F

Hemolysate samples were collected from multiple patients, and after incubation at 37 °C with or without GSSG (as described above), samples were digested and analyzed via LCMS/MS to identify the site of glutathione adduction on hemoglobin gamma. First, hemolysate samples were resolved via SDS-PAGE (4-12% Bis-tris gel), proteins were stained with colloidal Coomassie, and hemoglobin bands of interest were excised from the gel. Bands were sliced into 1mm3 gel pieces, and proteins were reduced (45 mM DTT), alkylated (100 mM iodoacetamide), and digested with trypsin (10 ng/uL) in 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate at 37 °C for 18 h. Peptides were extracted from the gel by dehydration with 60% MeCN, 0.1% TFA and dried by speed-vac centrifugation.

Peptides were reconstituted in 0.1% formic acid and loaded onto a capillary reverse phase analytical column (360 μm O.D. × 100 μm I.D.) using an Eksigent NanoLC Ultra HPLC and autosampler. The analytical column was equipped with a laser-pulled emitter tip and packed with 20cm of C18 reverse phase material (Jupiter, 3μm beads, 300Å, Phenomenex). Peptides were gradient-eluted at a flow rate of 500 nL/min, and the mobile phase solvents consisted of 0.1% formic acid, 99.9% water (solvent A) and 0.1% formic acid, 99.9% acetonitrile (solvent B). A 90-minute gradient was performed, consisting of the following: 0-10 min (sample loading), 2% B; 10-50 min, 2-35% B; 50-60 min, 35-90% B; 60-65 min, 90% B, 65-70 min 90-2% B, and 70-90 min (column equilibration), 2% B.

Peptides were analyzed on a LTQ Orbitrap Velos (Thermo Scientific) mass spectrometer, equipped with a nanoelectrospray ionization source. The instrument was operated using a data-dependent method with dynamic exclusion enabled. Full scan (m/z 300 - 2000) spectra were acquired with the Orbitrap as the mass analyzer (resolution 60,000), and the top twelve most abundant ions in each MS scan were selected for fragmentation in the LTQ. An isolation width of 2 m/z, activation time of 10ms, and 35% normalized collision energy were used to generate MS/MS spectra. The MSn automatic gain control (AGC) target value was set to 1 × e4, and the maximum injection time was 100 ms. Dynamic exclusion parameters included exclusion duration time of 15 seconds and an exclusion list size of 500.

For peptide identification, tandem mass spectra were converted into DTA files using Scansifter and searched against a Homo sapiens subset of the UniprotKB (www.uniprot.org) protein database. Database searches were performed using a custom version of Sequest (Thermo Scientific) on the Vanderbilt ACCRE Linux cluster, and results were assembled in Scaffold 3 (Proteome Software). All searches were configured to include variable modifications of oxidation of methionine, carbamidomethylation on cysteine, and glutathione adduction on cysteine. To determine the relative abundance of the glutathionylated γ peptide present in the different hemolysate samples, accurate mass measurements acquired in the Orbitrap were used to generate extracted ion chromatograms (XICs). A window of 10ppm around the theoretical monoisotopic m/z values of the observed precursor ions was utilized for making XICs for the unmodified and glutathionylated peptide forms. Using Qual Browser, the integrated area under each XIC peak was determined, and the percent relative abundance of the glutathionylated peptide was calculated as a percentage of the total area under the curve (AUC) obtained for both the glutathionylated and unmodified forms of the γ peptide.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Alterations in cellular redox potential towards a more oxidized state has been described in preterm infants early in life20,21 and has been observed to be associated with later development of BPD22. An increase in the circulating levels of oxidized GSH (GSSG) or a decrease in the GSH/GSSG ratio is often interpreted as an indicator of heightened oxidative stress during the first week of life23. Measurement of free radicals can be quite difficult due to their short half-lives, whereas determination of protein adducts, particularly Hgb adducts, has proven to be a more practical approach to measure intracellular redox potentials due in part to the chemical stability of the reaction products24. There are numerous reports of increased circulating levels of glutathionylated Hgb A (β subunit) in adults with various disease processes associated with oxidative stress, but little is known about post-translational modifications of Hgb in premature infants. In 1986, the Cys-β93 was identified as the adduction site for glutathionylation of Hgb A and S9,12; no subsequent reports have addressed if glutathionylation of Hgb F occurs. The γG and γA subunits of Hgb F are each composed of 147 amino acids with nearly identical peptide sequences (Table 1). They differ in only one amino acid at position 139, consisting of a glycine and an alanine, in γG and γA, respectively. Of interest, there is only one Cys at position 94 in each protein sequence that could potentially serve as an adduction site resulting in a covalent disulfide bond between the γsubunit and the thiol of the Cys residue of GSH25.

Table 1.

The γG and γA subunits of Hgb F each composed of 147 amino acids with nearly identical peptide sequences.

| γG | ||||||

| 1 | MGHFTEEDKA | TITSLWGKVN | VEDAGGETLG | RLLVVYPWTQ | RFFDSFGNLS | |

| 51 | SASAIMGNPK | VKAHGKKVLT | SLGDAIKHLD | DLKGTFAQLS | ELHCDKLHVD | |

| * | ||||||

| 101 | PENFKLLGNV | LVTVLAIHFG | KEFTPEVQAS | WQKMVTGVAS | ALSSRYH | |

| γA | ||||||

| 1 | MGHFTEEDKA | TITSLWGKVN | VEDAGGETLG | RLLVVYPWTQ | RFFDSFGNLS | |

| 51 | SASAIMGNPK | VKAHGKKVLT | SLGDAIKHLD | DLKGTFAQLS | ELHCDKLHVD | |

| * | ||||||

| 101 | PENFKLLGNV | LVTVLAIHFG | KEFTPEVQAS | WQKMVTAVAS | ALSSRYH |

We began by employing a LC-MS approach to determine the levels of glutathionylated Hgb A and F from a fraction of whole blood samples obtained during the first month of life from extremely premature infants who were enrolled in PROP. Using a Waters Synapt LC-MS system, we detected the targeted proteins, α and β subunits of Hgb A and α, γG, and γA subunits of Hgb F, from the hemolysate of infant erythrocytes. Hgb subunits were separated over a twenty-minute gradient through use of a Waters Symmetry Shield 300™ C18 3.5um reverse phase column. The total ion chromatogram (TIC) is shown in the supplement (Fig. S1a), as well as extracted ion chromatograms (XIC) for the proteins: αβγG, and γA (Fig. S1b-e). The various Hgb subunits were chromatographically resolved; their relative peak areas were consistent with their known relative abundances determined by other analytical methods. Mass spectra were deconvoluted using the MaxEnt 1 algorithm, and calculated intact masses of the β subunit of Hgb A and the γG and γA subunits of Hgb F were consistent with their respective molecular weights, minus the terminal amino acid methionine, of 15,126 Da, 15,865 Da, 15,995 Da, and 16,009 Da, respectively (Fig. S2). The full mass spectrum (m/z 600- 3000) showing the charge state distribution of the proteins analyzed can be found in Fig. S3.

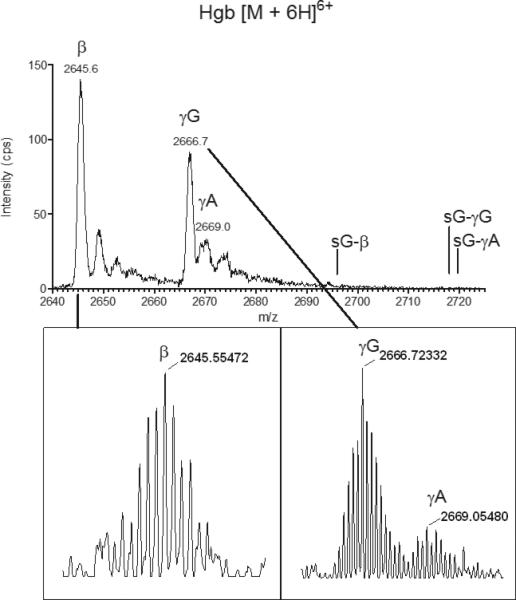

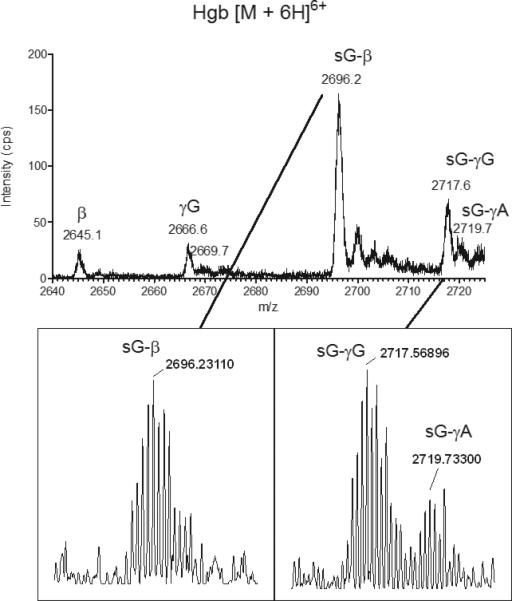

We then sought to determine if Hgb A and F found in premature infants can be modified by glutathionylation, as has been reported to occur in vitro and in vivo in adults on the β subunit of Hgb A. LC-MS analysis of a hemolysate sample obtained from a premature infant before and after GSSG incubation is shown in Figures S1 and S4, respectively. The TICs and XICs are shown for native and glutathionylated α, β, γG, and γA subunits. Figure 1 gives an expanded view of the [M+6H]6+ charge state of the unmodified β, γG, and γA subunits with m/z values of 2645, 2667 and 2669 respectively. There are no identifiable peaks consistent with glutathionylated Hgb in this patient sample prior to the addition of exogenous GSSG. After GSSG incubation, new chromatographic peaks are observed that are consistent with the adduction of hemoglobin (β and γ subunits) by GSH (Fig. S4b-e). The observed [M+6H]6+ charge states of the modified species, as shown in Figure 2, have m/z values of 2696, 2718, and 2720 for β, γG, and γA subunits, respectively. Charge state spectra were deconvoluted and intact masses of the β subunit of Hgb A and the γG and γA subunits of Hgb F were found to be shifted by 305 Da, consistent with the addition of one equivalent of GSH (Fig. S5). Addition of reducing agent, dithiothreitol (DTT), to the GSSG incubated samples completely reversed the GSH modification of β, γG, and γA subunits (data not shown). Calculated m/z values of unmodified and glutathionylated Hgb subunits at various charge states can be found in the supplement (Table S1). We did not identify detectable levels of glutathionylated α subunits of Hgb A or Hgb F in our premature patient samples. This is consistent with published adult hemoglobin studies that reported the α subunit of Hgb A is not modified by glutathionylation, in vitro or in vivo.

Figure 1.

Positive ion LC-ESI/MS spectra of native intact Hgb [M+6H]6+ (range 2640–2725 m/z) from an untreated patient hemolysate sample. The presence of Hgb γ A and Hgb γ G was confirmed by high-resolution LCESI/ MS (resolving power 100 000, see inset). The most abundant isotopes with m/z 2669.05480 (γA), m/z 2666.72332 (γ G) and 2645.55472 (β) were measured with 1.0 ppm, 0.7 ppm and 0.1 ppm mass error, respectively, relative to theoretical m/z values.

Figure 2.

Positive ion LC-ESI/MS spectra of native intact Hgb [M+6H] 6+ (range 2640-2725 m/z) from a patient hemolysate sample incubated with GSSG. The spectral behavior is altered in a manner that is consistent with protein modification by GSH. The presence of glutathionylated (sG) γA, γG, and β was confirmed by high resolution LC-ESI/MS (resolving power 100,000, see inset). The most abundant isotopes with m/z 2719.73300 (sG-γA), 2717.56896 (sG-γG), and 2696.23110 (sG-β) were measured with 0.7 ppm, 1.0 ppm, and 0.3 ppm mass error, respectively, relative to theoretical m/z values.

A high resolution LC-MS approach was employed to confirm glutathionylation of both γsubunits. Aliquots of hemolyzed erythrocytes from our patient cohort and GSSG incubated samples were analyzed by LC-MS on a high resolution LTQ Orbitrap mass spectrometer (resolution 100,000) so that intact protein isoforms could be measured with high mass accuracy. Figure 1 and 2 insets show the observed [M+6H]6+ charge states of intact glutathionylatedγG and γA of Hgb F. The most abundant isotopes were measured at less than 1.0 ppm mass error relative to the theoretical glutathionylated protein species (Table S1).

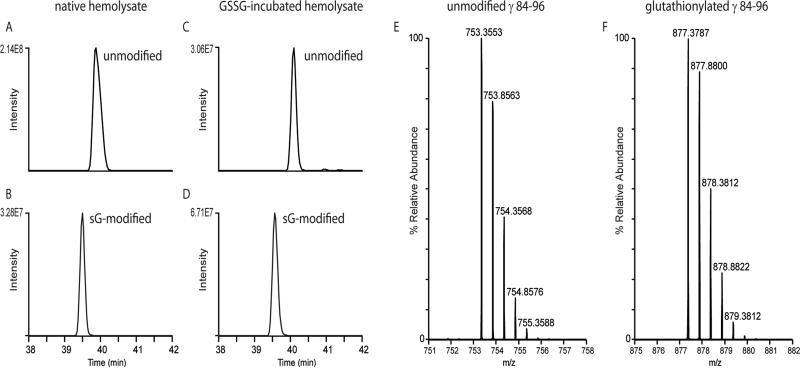

We proceeded to validate that Cys-94 was in indeed the site of glutathionylation on the γ subunits of Hgb F. Aliquots of hemolyzed erythrocytes from our patient cohort as well as GSSG incubated samples were proteolytically digested with trypsin, and peptides were analyzed by LC-MS/MS on a LTQ Orbitrap Velos mass spectrometer. Following database searching of the tandem mass spectra, we were able to obtain an average of greater than 90% sequence coverage of the Hgb γ subunit. Of significance, we identified both the unmodified and the glutathionylated Hgb γ peptide, GTFAQLSELHCDK (residues 84-96). Figure 3 shows the extracted ion chromatograms (XICs) of the observed precursor ions for the unmodified (Fig. 3a and 3c) and the glutathionylated (Fig. 3b and 3d) γ peptide from a native (Fig. 3a and 3b) and a GSSG incubated (Fig. 3c and 3d) hemolysate sample. XICs were generated using a mass tolerance of 10 ppm around the theoretical monoisotopic m/z values of the doubly- and triply-protonated unmodified (m/z 753.3563, m/z 502.5733) and glutathionylated (m/z 877.3796, 585.2555) precursor ions. The mass spectra in Figure 3e and 3f show the [M+2H]2+ peptide ions of the unmodified and glutathionylated Cys94-containing γpeptides identified in a representative native hemolysate sample. Observed peptide precursors were within 1.3 and 1.0 ppm, respectively, relative to theoretical m/z values. After calculating the integrated area for each XIC peak, the relative abundance of the glutathione-modified peptide could be determined for the hemolysate samples analyzed. As shown in Fig. 3d, the glutathione-modified peptide identified in the GSSG incubated sample was more abundant than the unmodified peptide, and it had a relative abundance of 70.1%. In the native hemolysate, without incubation with GSSG, the glutathionylated peptide was readily detectable as shown in Fig. 3e, and a percentage of 7.7% relative abundance was calculated for the modified peptide in this representative hemolysate sample. These approaches enabled us to unequivocally confirm glutathionylation of the Cys-94 residue of both γ subunits of Hgb F.

Figure 3.

LC-MS extracted ion chromatograms (XICs) of the observed precursor ions for unmodified (A, C) and glutathionylated (B, D) γ peptide, GTFAQLSELHCDK (residues 84–96). Panels A and B show XICs for peptides observed in the control hemolysate, while panels C and D show peptides observed in the GSSG incubated hemolysate sample. A window of 10 ppm around the theoretical monoisotopic m/z values of the doubly and triply protonated unmodified (m/z 753.3563, m/z 502.5733) and glutathionylated (m/z 877.3796, 585.2555) precursor ions was used for generating XICs. Note the available Cys residue of the unmodified peptide is carbamidomethylated during sample preparation, and the observed m/z values and mass spectra are consistent with this modification performed during sample processing. Mass spectra of the [M+2H]2+ precursor ions of the unmodified (E) and glutathionylated (F) γ peptides are also shown. Observed peptide precursors were within 1.3 and 1.0 ppm, respectively, relative to theoretical m/z values.

CONCLUSIONS

LC-MS strategies enabled identification of in vivo glutathionylation of γG and γA subunits of Hgb F; nanoLC-MS/MS analysis of proteolytically digested Hgb F confirmed the adduction site to be the Cys-γ94 residue. Ultra high-resolution mass spectrometry demonstrated that the adduction of GSH occurs on both γ subunits, G and A. Similar to previous studies of adult Hgb, we confirmed that glutathionylation of the β subunit of Hgb A occurs in premature infants. We did not detect modified forms of the α subunits of Hgb A and F. In conclusion, we report the novel finding of glutathionylated γG and γA of Hgb F in premature infants. Additional studies of this post-translational modification are needed to determine the physiologic impact on Hgb F function, including oxygen affinity, cooperativity, and alkaline Bohr effect, and if sG-Hgb γcan serve as a biomarker for clinical morbidities associated with oxidative stress in premature infants.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was funded in part by NHLBI through U01 HL101456 and VUMC38785-R to Judy L. Aschner, MD, through a PROP Scholar grant to David C. Ehrmann, MD (U01 HL101794), and through the Vanderbilt Center for Molecular Toxicology (P30 ES000267). REDCap database was utilized for data collection and analysis through CTSA award No. UL1 TR000445 from NCATS/NIH. The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health. We acknowledge Brian C. Hachey for his assistance in performing the accurate mass analysis of intact proteins.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mieyal JJ, Gallogly MM, Qanungo S, Sabens EA, Shelton MD. Molecular mechanisms and clinical implications of reversible protein S-glutathionylation. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2008;10:1941–88. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallogly MM, Mieyal JJ. Mechanisms of reversible protein glutathionylation in redox signaling and oxidative stress. Current opinion in pharmacology. 2007;7:381–91. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klatt P, Lamas S. Regulation of protein function by S-glutathiolation in response to oxidative and nitrosative stress. European journal of biochemistry / FEBS. 2000;267:4928–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martinez-Ruiz A, Cadenas S, Lamas S. Nitric oxide signaling: classical, less classical, and nonclassical mechanisms. Free radical biology & medicine. 2011;51:17–29. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen CA, Wang TY, Varadharaj S, et al. S-glutathionylation uncouples eNOS and regulates its cellular and vascular function. Nature. 2010;468:1115–8. doi: 10.1038/nature09599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dulce RA, Schulman IH, Hare JM. S-glutathionylation: a redox-sensitive switch participating in nitroso-redox balance. Circulation research. 2011;108:531–3. doi: 10.1161/RES.0b013e3182147d74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fu RH, Chiu TH, Chiang MC, et al. Lower erythrocyte glutathione peroxidase activity in bronchopulmonary dysplasia in the first week of neonatal life. Neonatology. 2008;93:269–75. doi: 10.1159/000112209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chatterjee A. Reduced glutathione: a radioprotector or a modulator of DNA-repair activity? Nutrients. 2013;5:525–42. doi: 10.3390/nu5020525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garel MC, Domenget C, Caburi-Martin J, Prehu C, Galacteros F, Beuzard Y. Covalent binding of glutathione to hemoglobin. I. Inhibition of hemoglobin S polymerization. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1986;261:14704–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pastore A, Mozzi AF, Tozzi G, et al. Determination of glutathionyl-hemoglobin in human erythrocytes by cation-exchange high-performance liquid chromatography. Analytical biochemistry. 2003;312:85–90. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(02)00500-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niwa T, Naito C, Mawjood AH, Imai K. Increased glutathionyl hemoglobin in diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidemia demonstrated by liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry. Clinical chemistry. 2000;46:82–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Craescu CT, Poyart C, Schaeffer C, Garel MC, Kister J, Beuzard Y. Covalent binding of glutathione to hemoglobin. II. Functional consequences and structural changes reflected in NMR spectra. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1986;261:14710–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niwa T. Protein glutathionylation and oxidative stress. Journal of chromatography B, Analytical technologies in the biomedical and life sciences. 2007;855:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takayama F, Tsutsui S, Horie M, Shimokata K, Niwa T. Glutathionyl hemoglobin in uremic patients undergoing hemodialysis and continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Kidney international Supplement. 2001;78:S155–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.59780155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piemonte F, Pastore A, Tozzi G, et al. Glutathione in blood of patients with Friedreich's ataxia. European journal of clinical investigation. 2001;31:1007–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2001.00922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maltepe E, Saugstad OD. Oxygen in health and disease: regulation of oxygen homeostasis--clinical implications. Pediatric research. 2009;65:261–8. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31818fc83f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lavoie JC, Chessex P. Gender and maturation affect glutathione status in human neonatal tissues. Free radical biology & medicine. 1997;23:648–57. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jobe AH. The New BPD. NeoReviews. 2006;7:e531–e45. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson PJ, Doyle LW. Neurodevelopmental outcome of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Seminars in perinatology. 2006;30:227–32. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis JM, Auten RL. Maturation of the antioxidant system and the effects on preterm birth. Seminars in fetal & neonatal medicine. 2010;15:191–5. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shim SY, Kim HS. Oxidative stress and the antioxidant enzyme system in the developing brain. Korean journal of pediatrics. 2013;56:107–11. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2013.56.3.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chessex P, Watson C, Kaczala GW, et al. Determinants of oxidant stress in extremely low birth weight premature infants. Free radical biology & medicine. 2010;49:1380–6. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vento M, Moro M, Escrig R, et al. Preterm resuscitation with low oxygen causes less oxidative stress, inflammation, and chronic lung disease. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e439–49. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tornqvist M, Fred C, Haglund J, Helleberg H, Paulsson B, Rydberg P. Protein adducts: quantitative and qualitative aspects of their formation, analysis and applications. Journal of chromatography B, Analytical technologies in the biomedical and life sciences. 2002;778:279–308. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(02)00172-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rubino FM, Verduci C, Giampiccolo R, Pulvirenti S, Brambilla G, Colombi A. Characterization of the disulfides of bio-thiols by electrospray ionization and triplequadrupole tandem mass spectrometry. Journal of mass spectrometry : JMS. 2004;39:1408–16. doi: 10.1002/jms.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.