Abstract

Purpose of review

The prevalence of nephrolithiasis has been on the rise over recent decades. There have also been extensive efforts to identify risk factors for chronic kidney disease (CKD). The purpose of this review is to highlight recent evidence on the association of nephrolithiasis with the development of CKD and end-stage renal disease (ESRD).

Recent findings

Several epidemiologic studies over the past decade assessed the relationship between history of nephrolithiasis and CKD. Across several studies, patients with nephrolithiasis had about a two-fold higher risk for decreased renal function or need for renal replacement therapy. This risk appears to be independent of risk factors for CKD that are common in stone formers such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus. Specific risk factors for CKD in stone formers include recurrent urinary tract infections, struvite and possibly uric acid stone composition, symptomatic stones, solitary kidney, ileal conduit, neurogenic bladder, and hydronephrosis.

Summary

Recent evidence has shown a consistent relationship between nephrolithiasis history and an increased risk of CKD and ESRD. Understanding the characteristics that predispose to CKD may better inform how to optimally manage patients with nephrolithiasis and prevent this complication.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, end-stage renal disease, glomerular filtration rate, nephrolithiasis

INTRODUCTION

Nephrolithiasis is an increasingly prevalent systemic disorder with substantial health and economic consequences [1–3]. The increase in nephrolithiasis is partially attributed to its strong association with features of the metabolic syndrome such as obesity, hypertension, and diabetes, which have also been steadily increasing [4]. Because the metabolic derangements linked with nephrolithiasis are risk factors for chronic kidney disease (CKD), identifying an independent relationship between nephrolithiasis and CKD can be challenging. Beyond the association, our understanding of the pathophysiologic mechanisms that link nephrolithiasis to adverse renal outcomes remains limited. The following discussion will review recent advances in our understanding of nephrolithiasis-associated kidney disease, highlighting recent findings for an association of nephrolithiasis with renal function loss and end-stage renal disease (ESRD). We also discuss putative risk factors for CKD that are more unique to patients with nephrolithiasis.

MECHANISMS OF NEPHROLITHIASIS-ASSOCIATED KIDNEY DAMAGE

A typical episode of nephrolithiasis usually entails a medical evaluation that includes a serum creatinine level. Depending on the characteristics and extent of stone burden, ureteral obstruction with hydronephrosis and subsequent elevation in creatinine may ensue. Similarly, if pyelonephritis complicates the stone episode, acute kidney injury may occur. These two main processes that culminate into acute kidney injury with an episode of nephrolithiasis are potential pathways for subsequent CKD. Our current understanding of how ureteral obstruction may lead to renal parenchymal damage comes from the extensive literature on unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) animal models. UUO has been associated with intense renal vasoconstriction with concomitant decline in glomerular filtrate rate (GFR) and renal blood flow (RBF) partially due to mechanisms of tubuloglomerular feedback in the setting of increased intratubular pressure [5]. When this process is prolonged, renal hypoperfusion and glomerulosclerosis may ensue. In addition, renal tissue of UUO models is characterized by increased interstitial volume, matrix deposition, monocyte infiltration, and fibroblast differentiation [6,7]. These processes are mediated by up-regulation in transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), both of which have been recognized to play an integral role in progression of tubulointerstitial inflammation and fibrosis. Similarly, chronic pyelonephritis due to an infected stone predisposes to tubulointerstitial inflammation and renal scarring [8,9]. As such, it is conceivable that recurrent, severe, or prolonged episodes of nephrolithiasis complicated by infection or obstruction may indeed lead to more permanent renal damage and CKD.

Another important aspect of nephrolithiasis-associated renal damage that warrants discussion is stone-specific injury. Elegant work by Evan et al. [10] utilized video imaging during percutaneous nephrolithotomy and cortical kidney biopsy to evaluate a group of brushite stone formers. They showed that brushite stones were associated with significant cortical fibrosis. The presence of interstitial apatite plaques (Randall’s plaque) in brushite stone formers was associated with duct plugging, collecting duct cell death, and inflammation. This process may explain the tubular atrophy and cortical fibrosis noted with brushite stones. The amount of stone burden may also contribute to the severity of parenchymal inflammation and fibrosis. In a sample of 50 patients from Thailand, where 90% had evidence of staghorn disease, renal biopsy evaluation revealed extensive inflammation with macrophage infiltration and evidence for mesenchymal epithelial cell transition [11]. These findings correlated with decreased kidney function and were consistent across the different stone compositions represented in that patient sample. Similar processes of inflammation and fibrosis have also been described with rare hereditary forms of nephrolithiasis. Primary hyperoxaluria, adenine phosphoribosyltransferase deficiency, cystinuria, and Dent’s disease have all been associated with crystal deposition at various sites within the renal parenchyma that may trigger subsequent inflammation [12]. Parenchymal crystal deposition, aggressive stone burden, frequent recurrence, and an increased need for procedural intervention all likely play a role in the increased risk of CKD among hereditary stone formers.

RISK OF CHRONIC KIDNEY DISEASE DUE TO NEPHROLITHIASIS

It is important to discuss the challenges in studying the relationship between nephrolithiasis and CKD. First, the independent contribution of nephrolithiasis to CKD can be difficult to detect because of the high prevalence of comorbid conditions (such as metabolic syndrome) in stone formers that portend to a higher risk for CKD. Second, details of the stone disease in terms of urine metabolic abnormalities, frequency of stone events, symptomatic vs. asymptomatic stones, and stone composition are often not available in reported investigations. Third, evidence would suggest that reduction in GFR may in fact be protective against nephrolithiasis because low GFR is associated with decreased urine calcium and decreased supersaturation for calcium oxalate and calcium phosphate crystals [13▪]. Finally, most studies have been retrospective and the overlapping diagnostic evaluation of nephrolithiasis and CKD can inflate the strength of association [14▪▪]. Still, there have been an increasing number of studies investigating the relationship between nephrolithiasis and CKD as reviewed in this next section.

One of the earlier studies was by Vupputuri et al. [15] in North Carolina. In a case–control study of 548 chart-confirmed cases of newly diagnosed CKD [defined by International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 codes and creatinine greater than 1.5 mg/dl] and 514 matched community controls, patients were interviewed for a self-reported history of kidney stones [15]. After adjusting for comorbid conditions associated with CKD, the likelihood of CKD was two-fold higher among persons with history of kidney stones [odds ratio (OR) 1.9].

A study of the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey evaluated the relationship of stone history with GFR [16]. They assessed estimated GFR (eGFR) of 15 005 adult patients who had creatinine measurements and completed a survey to ascertain if they had history of kidney stones. Those who reported a history of kidney stones (6%) were older, more likely to be men and non-African American, and have a history of coronary artery disease. Moreover, those with history of kidney stones had higher BMI than those without stone history (27.9 vs. 26.9 kg/m2). Stone formers were noted to have 3.4 ml/min/1.73 m2 lower eGFR compared to nonstone formers.

A population-based cohort study that evaluated the association of kidney stones with CKD risk was performed in Olmsted County utilizing the Rochester Epidemiologic Project [17]. Nephrolithiasis was detected by diagnostic codes and subsequent CKD was evaluated by three different methods: diagnostic codes, chronically elevated serum creatinine, and chronically reduced eGFR (<60 ml/min/ 1.73 m2). The stone formers (n = 4066) compared to the reference group (n = 10 150) were more likely to have cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, and obesity. Stone formers had a 51–68% increased risk of CKD when defined by ICD-9 codes and 25–44% increased risk when defined by chronically elevated serum creatinine levels. It would appear that the use of diagnostic codes to detect CKD may over-estimate the risk of CKD due to detection bias. Alternatively, diagnostic codes detect CKD characterized by proteinuria in patients with normal serum creatinine levels. The risk of CKD by either definition was independent of age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or obesity. This study highlights that the relationship between nephrolithiasis and CKD cannot be simply attributed to the increased prevalence of CKD risk factors present in patients with nephrolithiasis.

A study in England and Wales evaluated predictors of CKD risk in a large cohort (n = 1 574 749) of adults [18]. The purpose of the study was to develop a prediction tool to estimate risk of moderate-to-severe CKD. History of kidney stone was considered as one of the candidate predictors for CKD risk. As detected, only 0.68% of patients had a diagnostic code/or operative procedure consistent with kidney stone, which is substantially lower than the 5% known prevalence of stone disease [2]. Nonetheless, the adjusted risk for moderate-to-severe CKD was 1.27 (1.11, 1.46) among women with history of kidney stones, whereas an association was not evident among men.

The association of CKD with specific stone compositions has been previously studied. In a retrospective analysis of stone composition and urine chemistries, GFR below 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 was associated with lower urine pH and uric acid stones, whereas calcium phosphate stones were more prevalent in patients with GFR at least 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 [19]. This is indeed an intriguing observation and integrates the concept of hyperuricemia and its association with the metabolic syndrome with nephrolithiasis-associated CKD risk. It should be noted that these findings were consistent with another study from Taiwan that showed that patients with noncalcium-based nephrolithiasis (struvite and uric acid) were more likely to have eGFR less than 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 [20]. The association with struvite stones has been attributed to recurrent urinary tract infections.

RISK OF END-STAGE RENAL DISEASE DUE TO NEPHROLITHIASIS

An association between nephrolithiasis and ESRD is of particular interest given the significant morbidity and mortality. Characterizing an association of nephrolithiasis with ESRD is more challenging as the majority of patients with CKD outlive their kidney disease with only a minority progressing to ESRD. The indolent course of nephrolithiasis-associated CKD can make a clear association with ESRD difficult to detect. Common comorbidities in patients with nephrolithiasis, such as diabetes and hypertension, are widely recognized as primary causes of ESRD, whereas nephrolithiasis is often viewed as diagnosis of exclusion.

A study in France carefully evaluated the cause of ESRD in a cohort of 1391 patients with ESRD starting hemodialysis [21]. They identified 45 patients (3.2%) with nephrolithiasis as the exclusive or primary cause of ESRD and estimated an incidence rate of nephrolithiasis-associated ESRD of 3.1 cases per million populations per year. Two main observations were noted: struvite and calcium were the most common stone compositions of those that developed ESRD, and more women had nephrolithiasis-related ESRD than did men. This is one of the few studies that characterized cases of nephrolithiasis-associated ESRD from individual chart reviews. These findings are in contrast to the United States Renal Data System (USRDS) survey, where 0.2% of ESRD cases were attributed to kidney stones; however, the USRDS survey had limitations in ascertaining primary causes of ESRD [22].

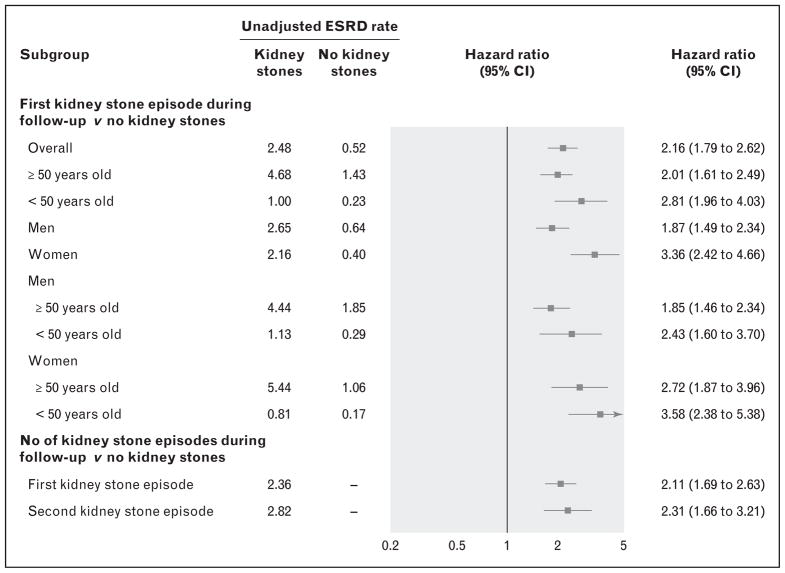

A recent study from Canada utilized the Alberta Kidney Disease Network database and evaluated the association of kidney stones with ESRD in a large cohort from the general population (n = 3 089 194) [23▪▪]. Nephrolithiasis cases (only 0.8% of the sample) were identified by diagnostic codes as well as physician claims. They showed that any kidney stone episode during up to 11 years of follow-up was associated with an increased risk of subsequent ESRD (hazard ratio 2.16), CKD (hazard ratio 1.74), or doubling of serum creatinine (hazard ratio 1.94) (Fig. 1). These associations were independent of other comorbid conditions. Interestingly, they also observed a significant modification by sex such that among women, nephrolithiasis had a stronger association with ESRD among women than among men. The strength of the association of nephrolithiasis with ESRD was consistent with other studies, and the predisposition of women to nephrolithiasis-associated ESRD reproduced findings of prior studies [18,21].

FIGURE 1.

Forest plot of multivariable adjusted hazard ratios for ESRD risk with nephrolithiasis in various subgroups. Adapted with permission [23▪▪]. ESRD, end-stage renal disease.

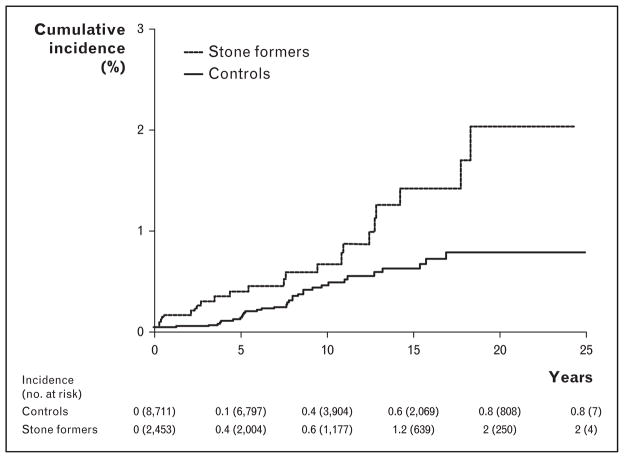

A population-based matched cohort study in Olmsted County evaluated this association with up to 25 years of follow-up [14▪▪]. A unique strength of this study is that they evaluated the association of kidney stones utilizing diagnostic codes (n = 6911), and in a subset, manual chart review to validate symptomatic stone formers (n = 2457). Several important observations were noted: the risk of incident ESRD based on the validated subset of symptomatic stone formers was again about twofold higher compared to controls (hazard ratio 1.98) (Fig. 2); after adjusting for comorbidities and baseline CKD, the risk of ESRD remained; stone formers who developed ESRD were more likely to have recurrent urinary tract infections, an ileal conduit, a neurogenic bladder, or hydronephrosis compared to ESRD patients in the control group; and the attributable risk of ESRD from nephrolithiasis was calculated at 5%. This 5% attributable risk of ESRD from nephrolithiasis suggests that kidney stones with their associated urological disease are a small but non-negligible contribution to the burden of ESRD.

FIGURE 2.

The cumulative ESRD incidence in symptomatic stone formers compared to controls. Adapted with permission [14▪▪]. ESRD, end-stage renal disease.

NEPHROLITHIASIS-ASSOCIATED RISK FACTORS FOR CHRONIC KIDNEY DISEASE

In addition to the interplay between metabolic syndrome, nephrolithiasis, and CKD, several stone-specific risk factors for nephrolithiasis-associated CKD have been identified. The putative risk factors for nephrolithiasis-associated CKD are as follows:

-

Metabolic

Hypertension

Diabetes

Obesity

Microalbuminuria

-

Anatomic

Ileal conduit

Neurogenic bladder

Solitary kidney

Hydronephrosis

-

Stone-specific

Struvite

Uric acid

Symptomatic

-

Infectious

Struvite stones

Recurrent urinary tract infections

-

Others

Female sex.

Among potential kidney donors, those with past symptomatic kidney stones were more likely to have albuminuria, whereas among those with only asymptomatic stones there was no increased risk of albuminuria [24] Naganuma et al. [25] evaluated 102 patients in Japan who had undergone an ileal conduit urinary diversion for bladder malignancy and identified characteristics for those who developed CKD. They identified nephrolithiasis as more common among those who developed CKD. Moreover, this association was independent of older age, hypertension, or prior history of hydronephrosis.

An Olmsted County population-based matched case–control study identified risk factors for 53 patients with nephrolithiasis and CKD compared to 106 controls with nephrolithiasis and no CKD [26]. Patients with nephrolithiasis and CKD were more likely to have hypertension, diabetes, frequent urinary tract infections, struvite stones, and allopurinol use. On multivariate analysis, however, only diabetes, frequent urinary tract infections, and the use of allopurinol therapy were independent risk factors for CKD in patients with nephrolithiasis.

A potentially important risk factor for CKD is the surgical management of stone disease. Several studies have assessed for an association of percutaneous nephrolithotomy with long-term risk of CKD. One of the earlier studies evaluated 16 patients with baseline creatinine above 1.4 mg/dl and followed them for a mean of 51 months after nephrolithotomy [27]. Three patients progressed to ESRD requiring dialysis after the procedure, all of whom had diabetes and one had a solitary kidney. In a larger study of 177 patients with CKD who underwent percutaneous nephrolithotomy and were followed for a mean of 43 months, renal function deterioration was noted in only 16.4% [28▪]. The majority of patients with CKD undergoing nephrolithotomy had the same or improved renal function after at least 1 year of follow-up. In another study, the independent risk factors predictive of CKD progression after percutaneous nephrolithotomy were diabetes and urinary tract infections [29]. Bilen et al. [30] evaluated the effect of percutaneous nephrolithotomy on eGFR at 3 months after procedure in a cohort of patients with eGFR below 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 and identified only 5 patients out of 130 who had worsening eGFR, but none requiring dialysis. They also confirmed that urinary tract infections were a predictor for worsening kidney function. Therefore, it appears that percutaneous nephrolithotomy is generally well tolerated, but as with other nephrolithiasis patients, concurrent diabetes and urinary tract infections are risk factors for CKD progression.

Acute and chronic renal dysfunction after shock wave lithotripsy due to renal contusions has been proposed based on evidence of parenchymal injury in animal studies [31]; however, clinical studies in humans do not confirm any significant loss of renal function with long-term follow-up after the procedure [32]. This finding also applies to patients with solitary kidneys [33]. Nephrectomy for nephrolithiasis does reduce kidney function as expected [34].

CONCLUSION

Cohort and case-control studies during the past decade have demonstrated an increased risk of CKD with nephrolithiasis. Nephrolithiasis is significantly associated with two-fold higher risk of CKD and ESRD independent of other known CKD risk factors. Nephrolithiasis-related comorbidities, such as urinary tract infections, may specifically cause renal parenchymal damage. Further studies are needed to better define and characterize nephrolithiasis-associated CKD and the patients at increased risk for this complication.

KEY POINTS.

Nephrolithiasis is associated with about a two-fold higher risk of ESRD.

The risk of CKD with nephrolithiasis is independent of other well established CKD risk factors, such as diabetes and hypertension, that are common among stone formers.

Characteristics of patients with nephrolithiasis that are associated with an increased risk of CKD include recurrent urinary tract infections, symptomatic stones, struvite or uric acid stone composition, and diabetes mellitus.

Other than nephrectomy, there is little evidence that stone removal surgery contributes to progressive CKD.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (Mayo Clinic O’Brien Urology Research Center DK83007) and made possible by the Rochester Epidemiology Project (AG034676) from the National Institutes of Health, U.S. Public Health Service.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

▪ of special interest

▪▪ of outstanding interest

Additional references related to this topic can also be found in the Current World Literature section in this issue (p. 491).

- 1.Lotan Y. Economics and cost of care of stone disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2009;16:5–10. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stamatelou KK, Francis ME, Jones CA, et al. Time trends in reported prevalence of kidney stones in the United States. Kidney Int. 2003;63:1817–1823. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sakhaee K, Maalouf NM, Sinnott B. Clinical review. Kidney stones 2012: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:1847–1860. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sakhaee K. Nephrolithiasis as a systemic disorder. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2008;17:304–309. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3282f8b34d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaudio KM, Siegel NJ, Hayslett JP, Kashgarian M. Renal perfusion and intratubular pressure during ureteral occlusion in the rat. Am J Physiol. 1980;238:F205–209. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1980.238.3.F205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klahr S. Urinary tract obstruction. Semin Nephrol. 2001;21:133–145. doi: 10.1053/snep.2001.20942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klahr S, Morrissey J. Obstructive nephropathy and renal fibrosis: the role of bone morphogenic protein-7 and hepatocyte growth factor. Kidney Int Suppl. 2003;87:105–112. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.64.s87.16.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larsson PA, Cano M, Grenabo L, et al. Morphological lesions of the rat urinary tract induced by inoculation of mycoplasmas and other urinary tract pathogens. Urol Int. 1989;44:210–217. doi: 10.1159/000281506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta M, Bolton DM, Gupta PN, Stoller ML. Improved renal function following aggressive treatment of urolithiasis and concurrent mild to moderate renal insufficiency. J Urol. 1994;152:1086–1090. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)32509-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evan AP, Lingeman JE, Coe FL, et al. Crystal-associated nephropathy in patients with brushite nephrolithiasis. Kidney Int. 2005;67:576–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.67114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boonla C, Krieglstein K, Bovornpadungkitti S, et al. Fibrosis and evidence for epithelial-mesenchymal transition in the kidneys of patients with staghorn calculi. BJU Int. 2011;108:1336–1345. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.10074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evan AP, Coe FL, Lingeman JE, et al. Renal crystal deposits and histopathology in patients with cystine stones. Kidney Int. 2006;69:2227–2235. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13▪.Gershman B, Sheth S, Dretler SP, et al. Relationship between glomerular filtration rate and 24-h urine composition in patients with nephrolithiasis. Urology. 2012;80:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.12.019. Lower quintiles of GFR are associated with decreased urine calcium and decreased urine saturation for calcium based kidney stones. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14▪▪.El-Zoghby ZM, Lieske JC, Foley RN, et al. Urolithiasis and the risk of ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:1409–1415. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03210312. Populaton-based matched cohort study showing two-fold higher risk of ESRD among symptomatic stone formers. Stone formers who developed ESRD were likely to have other urological disease. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vupputuri S, Soucie JM, McClellan W, Sandler DP. History of kidney stones as a possible risk factor for chronic kidney disease. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14:222–228. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(03)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gillen DL, Worcester EM, Coe FL. Decreased renal function among adults with a history of nephrolithiasis: a study of NHANES III. Kidney Int. 2005;67:685–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.67128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rule AD, Bergstralh EJ, Melton LJ, 3rd, et al. Kidney stones and the risk for chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:804–811. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05811108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C. Predicting the risk of chronic kidney disease in men and women in England and Wales: prospective derivation and external validation of the QKidney Scores. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kadlec AO, Greco KA, Fridirici ZC, et al. Effect of renal function on urinary mineral excretion and stone composition. Urology. 2011;78:744–747. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chou YH, Li CC, Hsu H, et al. Renal function in patients with urinary stones of varying compositions. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2011;27:264–267. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jungers P, Joly D, Barbey F, et al. ESRD caused by nephrolithiasis: prevalence, mechanisms, and prevention. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44:799–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collins AJ, Foley RN, Herzog C, et al. US Renal Data System 2010 Annual Data Report. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57 (A8):e1–e526. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23▪▪.Alexander RT, Hemmelgarn BR, Wiebe N, et al. Kidney stones and kidney function loss: a cohort study. Br Med J. 2012;345:e5287. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5287. Large retrospective cohort study showing consistent two-fold higher risk of CKD, ESRD, and doubling of serum creatinine among patients with nephrolithiasis over an 11-year follow-up period. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lorenz EC, Lieske JC, Vrtiska TJ, et al. Clinical characteristics of potential kidney donors with asymptomatic kidney stones. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:2695–2700. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naganuma T, Takemoto Y, Maeda S, et al. Chronic kidney disease in patients with ileal conduit urinary diversion. Exp Ther Med. 2012;4:962–966. doi: 10.3892/etm.2012.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saucier NA, Sinha MK, Liang KV, et al. Risk factors for CKD in persons with kidney stones: a case-control study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55:61–68. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuzgunbay B, Gul U, Turunc T, et al. Long-term renal function and stone recurrence after percutaneous nephrolithotomy in patients with renal insufficiency. J Endourol. 2010;24:305–308. doi: 10.1089/end.2009.0362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28▪.Akman T, Binbay M, Aslan R, et al. Long-term outcomes of percutaneous nephrolithotomy in 177 patients with chronic kidney disease: a single center experience. J Urol. 2012;187:173–177. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.09.038. An analysis of CKD patients who underwent percutaneous nephrolithotomy and were followed for over 12 months showed that eGFR remained stable or improved in 83% of patients. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ozden E, Mercimek MN, Bostanci Y, et al. Long-term outcomes of percutaneous nephrolithotomy in patients with chronic kidney disease: a single-center experience. Urology. 2012;79:990–994. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.10.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bilen CY, Inci K, Kocak B, et al. Impact of percutaneous nephrolithotomy on estimated glomerular filtration rate in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Endourol. 2008;22:895–900. doi: 10.1089/end.2007.0435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evan AP, Willis LR, Lingeman JE, McAteer JA. Renal trauma and the risk of long-term complications in shock wave lithotripsy. Nephron. 1998;78:1–8. doi: 10.1159/000044874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eassa WA, Sheir KZ, Gad HM, et al. Prospective study of the long-term effects of shock wave lithotripsy on renal function and blood pressure. J Urol. 2008;179:964–968. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.10.055. discussion 968–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.el-Assmy A, el-Nahas AR, Hekal IA, et al. Long-term effects of extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy on renal function: our experience with 156 patients with solitary kidney. J Urol. 2008;179:2229–2232. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carvalho M, Martin RL, Passos RC, Riella MC. Nephrectomy as a cause of chronic kidney disease in the treatment of urolithiasis: a case-control study. World J Urol. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00345-012-0845-x. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]