Abstract

Objective

The objective was to determine whether treatments with demonstrated efficacy for binge eating disorder (BED) in specialist treatment centers can be delivered effectively in primary care settings to racially/ethnically diverse obese patients with BED. This study compared the effectiveness of self-help cognitive-behavioral therapy (shCBT) and an anti-obesity medication (sibutramine), alone and in combination, and it is only the second placebo-controlled trial of any medication for BED to evaluate longer-term effects after treatment discontinuation.

Method

104 obese patients with BED (73% female, 55% non-white) were randomly assigned to one of four 16-week treatments (balanced 2-by-2 factorial design): sibutramine (N=26), placebo (N=27), shCBT+sibutramine (N=26), or shCBT+placebo (N=25). Medications were administered in double-blind fashion. Independent assessments were performed monthly throughout treatment, post-treatment, and at 6- and 12-month follow-ups (16 months after randomization).

Results

Mixed-models analyses revealed significant time and medication-by-time interaction effects for percent weight loss, with sibutramine but not placebo associated with significant change over time. Percent weight loss differed significantly between sibutramine and placebo by the third month of treatment and at post-treatment. After the medication was discontinued at post-treatment, weight re-gain occurred in sibutramine groups and percent weight loss no longer differed among the four treatments at 6- and 12-month follow-ups. For binge-eating, mixed-models revealed significant time and shCBT-by-time interaction effects: shCBT had significantly lower binge-eating frequency at 6-month follow-up but the treatments did not differ significantly at any other time point. Demographic factors did not significantly predict or moderate clinical outcomes.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that pure self-help CBT and sibutramine did not show long-term effectiveness relative to placebo for treating BED in racially/ethnically diverse obese patients in primary care. Overall, the treatments differed little with respect to binge-eating and associated outcomes. Sibutramine was associated with significantly greater acute weight loss than placebo and the observed weight-regain following discontinuation of medication suggests that anti-obesity medications need to be continued for weight loss maintenance. Demographic factors did not predict/moderate clinical outcomes in this diverse patient group.

Keywords: binge eating, eating disorders, obesity, cognitive-behavioral therapy, treatment, primary care, weight loss

Binge-eating disorder (BED), a formal diagnosis in the DSM-5 (APA, 2013), is defined by recurrent binge eating (i.e., eating unusually large quantities of food accompanied by subjective feelings of loss of control), marked distress about the binge eating, and the absence of extreme weight compensatory behaviors (e.g., purging) that characterize bulimia nervosa. BED is a prevalent clinical problem that is associated strongly with obesity (Hudson, Hiripi, Pope, & Kessler, 2007) and with high rates of biopsychosocial problems (Grilo, White, & Masheb, 2009; Hudson et al., 2007). BED shares features with, but is distinct from other eating disorders and obesity (Grilo, Crosby, et al., 2009; Grilo, Hrabosby, et al. 2008) and thus represents a clinical challenge (Wlison, Grilo, & Vitousek, 2007).

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is the best-established treatment for BED (NICE, 2004; Wilson et al., 2007). CBT has demonstrated “treatment specificity” (Grilo, Masheb, & Wilson, 2005) and produces robust improvements in binge eating, eating disorder psychopathology, and psychosocial functioning that are durable for 12-months (Grilo, Crosby, Wilson, & Masheb, 2011) to 48-months (Hilbert et al. 2012) following treatment. Although CBT generally produces remission rates of roughly 50%, weight loss tends to be minimal (Grilo, Masheb et al., 2011; Wilfley et al., 2002). Several medications have short-term efficacy relative to placebo (Reas & Grilo, 2008; Reas & Grilo, 2014), with specific anti-epileptic agents such topiramate (McElroy et al., 2007) and anti-obesity agents such as sibutramine (Appolinario et al., 2003; Wilfley et al. 2008) producing acute reductions in both binge eating and weight. Although BED is associated strongly with obesity (Hudson et al., 2007), and despite the well-known failure of CBT to reduce weight in obese persons with BED, only two studies to date have tested the additive strategy of combining medication known to produce weight loss with CBT methods (Claudino et al., 2007; Grilo, Masheb, & Salant, 2005). Both of those studies reported significant short-term benefits of combining specific medications and CBT to enhance weight losses in obese patients with BED suggesting the need for further research testing combined treatments and with expanded follow-up periods to determine the durability of outcomes (Reas & Grilo, 2008; Reas & Grilo, 2014).

Another pressing issue facing the eating disorder field concerns the need for research on disseminating effective treatment methods (Shafran et al., 2009; Wilson & Zandberg, 2012). Despite the existence of empirically-supported treatments (Wilson et al., 2007), few individuals with eating/weight concerns receive mental health services (Marques et al., 2011), and even fewer receive treatments that have demonstrated effectiveness (Hart et al., 2011; Wilson & Zanberg, 2012). There is a shortage of clinicians with specialized training in evidence-based methods such as CBT (Kazdin & Blase, 2011; Shafran et al., 2009) especially for eating disorders (Hart et al., 2011; Mussell et al., 2000).

One potential approach to broader dissemination of effective interventions involves the use of various forms of “guided” self-help and “pure” self-help CBT methods which have shown promise in emerging research (NICE, 2004; Sysko & Walsh, 2008; Wilson & Zandberg, 2012). “Guided” self-help CBT – i.e., with some guidance or facilitation by clinicians – has demonstrated efficacy for BED (Sysko & Walsh, 2008; Wilson & Zandberg, 2012), including “treatment-specificity” for guided self-help CBT compared to guided self-help behavioral weight loss (Grilo & Masheb, 2005). Much less is known, however, about the efficacy of “pure” self-help CBT – i.e., self-help purely self-directed and without guidance from clinicians. Across studies, findings generally indicate that pure self-self is less effective than guided-self-help CBT (Sysko & Walsh, 2008). Only three published studies, however, have directly tested pure self-help CBT for BED against no-self-help (i.e., wait-list) and these studies yielded mixed results. Carter and Fairburn (1998), in a community-based study in the UK, reported that self-help CBT was superior to a wait-list control. In two studies performed in specialist settings, one reported that pure self-help CBT was superior to a wait-list control (Peterson et al., 1998) whereas a recent and much larger study did not (Peterson et al., 2009). Thus, further research is needed on the effectiveness of self-help CBT for BED particularly across different health-care settings (Wilson & Zandberg, 2012).

Nearly all of the treatment literature for BED is based on trials performed in specialist research clinics and comprised mostly of white participants (Franko et al., 2012) and may not generalize adequately to generalist clinical settings or to more ethnically and racially diverse patient groups. Franko and colleagues (2012), for example, using pooled data from 11 treatment trials of CBT for BED, found significant ethnic/racial differences in BED symptoms that existed even after adjusting for differences in BMI and education. The three RCTs that have tested pure self-help CBT for BED consisted of nearly all white patients – i.e. 96% in Peterson et al. (1998) and 97% in both of the other studies (Carter & Fairburn, 1998; Peterson et al., 2009) – which contrasts sharply with epidemiologic findings regarding the relatively comparable distribution of BED across ethnic/racial groups (Alegria et al., 2007; Marques et al., 2011). Thompson-Brenner and colleagues (2013) reported significant associations for race and education with some treatment outcomes in specialty clinic trials: lower level of education predicted greater frequency of binge eating at posttreatment and Africian Americans had greater reductions in eating disorder psychopathology than did Caucasians. Moreover, minority groups with eating disorders have lower utilization rates of mental health services than whites and tend to receive most of their health care from primary care settings (Marques et al., 2011). Thus, treatment research for BED needs to be performed in general clinic settings with more diverse patient groups and include analyses testing demographic features as predictors and moderators of outcomes (Grilo, Masheb, & Crosby, 2012).

Concerns about the generalization of findings from specialist to generalist settings are neither merely “academic” nor are they limited to CBT interventions. For example, in the treatment literature for bulimia nervosa, we note the striking discrepancy between findings from a RCT testing self-help CBT methods and fluoxetine performed in a specialty clinic (Mitchell et al. 2001) versus those performed in a primary care setting (Walsh, Fairburn, Mickley, Sysko, & Parides, 2004). Whereas Mitchell and colleagues (2001) found that both shCBT and fluoxetine were effective, Walsh and colleagues (2004) found that both guided-self-help CBT and fluoxetine had very high dropout rates and poor outcomes when delivered in primary care (i.e., only 30.8% completed treatment and only 12.2% and 15.9% achieved remission in the guided-self-help and fluoxetine conditions, respectively) when delivered in primary care.

BED is associated with heightened service utilization in primary care settings (Johnson, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001) but continues to be infrequently identified by general healthcare providers (Mond, Myers, Crosby, Hay, & Mitchell, 2010). Thus, this RCT was designed to determine whether treatments with demonstrated efficacy for binge eating disorder (BED) in specialist treatment centers can be delivered effectively by generalists in primary care settings to racially/ethnically diverse obese patients with BED. Specifically, this study compared the effectiveness of (pure) self-help CBT and an anti-obesity medication (sibutramine), alone and in combination, as initiated by generalist primary care physicians, as potential “first-step” interventions for BED. These two treatments were selected both for their demonstrated efficacy and for their potential ease of use in primary care. The medication, sibutramine, chosen for this study was FDA-approved for the treatment of obesity during the design and initiation of this trial. Two RCTs, specifically with obese patients with BED, reported significant reductions in both binge eating and weight for sibutramine relative to placebo (Appolinario et al., 2003; Wilfley et al., 2008). Based on emerging concerns and findings from the SCOUT study (James et al., 2010), the manufacturer withdrew sibutramine from the market in 2010 (Reas & Grilo, in press), at which time enrollment in this RCT was stopped. However, the present study nonetheless provides important information about the effectiveness of sibutramine and the potential benefits of combining an anti-obesity agent with shCBT. This is only the second study to date testing the additive effects of combining an anti-obesity medication with CBT (Grilo et al., 2005) and is only the second RCT for BED to report follow-up data for any medication-only strategy following acute treatment and discontinuation (Grilo, Crosby, et al., 2012; see Reas & Grilo, 2008). Lastly, but quite importantly, even if the sibutramine/placebo findings are deemed irrelevant in light of the withdrawal from the market, they provide a powerful comparison condition for interpreting the shCBT (Freedland et al., 2011) including important advantages over the wait-list controls in the relevant self-help trials (Carter & Fairburn, 1998; Peterson et al., 1998; Peterson et al., 2009).

Methods

Participants

Participants were 104 obese patients who met DSM-5 criteria for BED and were randomized to treatment. The participants were respondents for a treatment study for binge eating being performed in primary care settings in a large university-based medical health-care center in an urban setting. Recruitment consisted of placing posters and flyers throughout the primary care settings in addition to mailings and referrals initiated by the primary care physicians. Participants were required to be aged 18 to 65 years, obese (body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 and < 50), and exceed DSM-5 criteria for BED (the stricter duration criterion of 6 months from the DSM-IV-TR was used, as opposed to three months)1.

Recruitment for this study was intended to enhance generalizability and relatively few exclusionary criteria were applied. Exclusion criteria included current use of antidepressant medication (a contraindication to starting sibutramine), current use of medication known to influence eating/weight, few select severe psychiatric problems (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and current substance use disorder), severe medical problems (cardiac disease, liver disease), and uncontrolled hypertension, thyroid disease, or diabetes. Full IRB review and approval was obtained at Yale and all participants provided written informed consent prior to procedures.

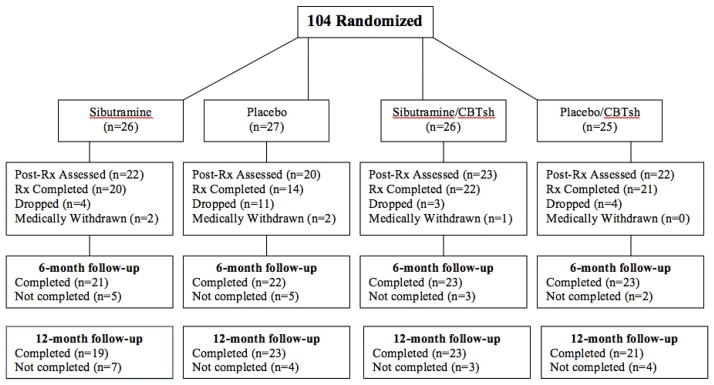

Figure 1 summarizes the flow of participants throughout the study. One thousand one-hundred and thirty individuals (recruited and identified in primary care settings) made telephone inquiries and 940 were screened. One hundred sixty-two passed screening performed by research assistants and were scheduled for in-person assessments to determine eligibility. Of these, 104 individuals were interested in participating, met eligibility requirements, completed baseline assessments, and were randomized blindly to one of the four 4-month treatment conditions.

Figure 1.

Participant flow throughout the study.

Overall, participants had a mean age of 43.9 years (SD = 11.2) and a mean BMI of 38.3 kg/m2 (SD = 5.6); 70.2% (N=73) were female. In terms of race/ethnicity, 45.2% (N=47) were Caucasian, 34.6% (N=36) were African-American, 13.5% (N=14) were Hispanic-American, and 6.7% (N=7) were of “other” minority/ethnic groups.

Diagnostic Assessments and Repeated Measures

Diagnostic and assessment procedures were performed by trained doctoral-level research-clinicians. BED and co-existing DSM-IV psychiatric disorder diagnoses were based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I/P; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1996). Participants were given $50 for completing the post-treatment assessment and $100 for the follow-up assessments.

Eating Disorder Examination Interview (EDE; Fairburn & Cooper 1993), a semi-structured, investigator-based interview, was administered to assess eating disorder psychopathology and to confirm the BED diagnosis. The EDE was re-administered at post-treatment and at both follow-ups performed 6- and 12-months after treatment completion. The EDE focuses on the previous 28 days except for diagnostic items, which are rated for DSM-based duration stipulations. The EDE assesses the frequency of objective bulimic episodes (OBE; i.e., binge-eating defined as unusually large quantities of food with a subjective sense of loss of control), which corresponds to the DSM-based definition of binge-eating. The EDE also comprises four subscales which are averaged to produce a total global score reflecting overall severity. The EDE has good validity (Grilo, Masheb, & Wilson, 2001) and has demonstrated good inter-rater and test-retest reliability in BED (Grilo, Masheb, Lozano-Blanco, & Barry, 2004) and with diverse obese patient groups (Grilo, Lozano, & Elder, 2005). In the present study, inter-rater (N=34 ratings of taped interviews) reliability of the EDE was excellent. Inter-rater reliability intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) were 0.83 for OBE episodes, 0.90 for OBE days, and 0.93 for EDE global score.

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck & Steer, 1987) 21-item version is a well-established self-report (Beck, Steer, & Garbin, 1998) measure of symptoms of depression. The BDI was administered at baseline, bi-monthly during treatment, at post-treatment, and at 6- and 12-month follow-ups.

Weight and height were measured at baseline and weight was measured monthly throughout treatment, at post-treatment, and at 6- and 12-month follow-ups using a large capacity digital scale. These measurements were obtained in a standardized manner by the research staff during monthly assessments.

Randomization to Treatments and Maintaining Treatment Blindness

Randomization to treatment assignment occurred in the exact order following completion of all assessments and medical approval and was performed independently from the investigators by a research-pharmacist at a separate Yale facility using a computer-generated schedule generated by a biostatistician. Participants were randomly assigned with stratification by BED status (i.e., full DSM-IV-TR criteria which required twice-weekly binge frequency during the past 6 months or subthreshold DSM-IV-TR criteria reduced to once-weekly binge criteria during the past 6 months; both requirements exceed DSM-5 criteria for BED). Randomization was to one of four treatment conditions following a balanced 2-by-2 factorial design for 16 weeks: (1) sibutramine (15mg/day); (2) placebo; (3) shCBT plus sibutramine (15mg/day); or shCBT plus placebo. Within each stratum, randomization was performed in blocks of 12 to obviate any secular trends. To ensure concealment of the randomization, medication (sibutramine or placebo) was prepared in identical-appearing capsules. The double-blind medication status was not broken until after post-treatment completion and discontinuation of treatment when participants were notified; however, the notification procedure maintained the blind for both the investigators and evaluators until after all participants had completed all assessments including the 12-month follow-up visits. The assessments were performed independently by doctoral research evaluators at our research clinic who were blinded to both the medication status and to whether participants received the shCBT.

Treatment Conditions

Self-Help Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (shCBT)

Half the patients were randomly assigned to receive shCBT. These patients were given Overcoming Binge Eating (Fairburn, 1995), a self-help book which follows the professional CBT therapist program (Fairburn, Marcus, & Wilson, 1993) considered to be the “treatment of choice” for BED (NICE, 2004; Wilson et al., 2007). This self-help CBT book was used in the Carter & Fairburn (1998) community-based effectiveness trial with non-specialist clinicians and is used in controlled trials at specialist centers using guided-self-help (e.g., Grilo & Masheb, 2005; Grilo, Masheb, & Salant, 2005; see review by Sysko & Walsh, 2008).

The self-help CBT (Fairburn, 1995) book has three stages. First, the CBT model (including the structure, goals, and methods) is described; information about binge eating, dieting, and health is provided; and self-monitoring and behavioral techniques for normalizing eating patterns are explained. The second stage consists of maintaining the normalized eating patterns, continuing to self-monitor, integrating cognitive procedures, and learning new coping skills for triggers of maladaptive eating. The final stage focuses on maintaining changes and learning relapse prevention techniques.

Primary care physicians, who did not have any specific training as mental health professionals or with eating disorders, instructed the participants assigned to shCBT to read the book and to focus on following the self-help program described in Part II of Overcoming Binge Eating (Fairburn, 1995). With respect to part II, participants also were encouraged to follow the program’s suggestions for record keeping and goal setting. The primary care physicians were provided brief training and a script to assist them in delivering this two-step message in a standard manner to participants.

Medication (Sibutramine or Placebo)

Half the patients were randomly assigned to receive, in double-blind fashion, either sibutramine or placebo in matching capsules that were visually identical. Sibutramine, a serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, was given using a 15 mg per day fixed-dose throughout the four months. The 15mg/day dosing has been demonstrated to produce weight loss in obese patients (Wadden et al., 2005) and to reduce both binge eating and weight in BED (Appolinario et al., 2003; Wilfley et al., 2008). Sibutramine was FDA-approved for obesity until 2010 when the manufacturer withdrew it from the market at which time enrollment in this study was stopped. The Wadden et al (2005) study demonstrated the specific efficacy of combining sibutramine with behavioral treatment for reducing weight in obese patients supporting our study design. Primary care physicians provided the medication to the participants along with information about sibutramine, including its potential mechanisms and effects on eating/weight, and potential side-effects, and instructed participants how to take it. The physicians instructed the participants to contact them (and the research staff) if any concerns arose. Physicians were available to meet with patients as needed to discuss any ongoing medication issues, side-effects, and their management.

Thus, the medication conditions were delivered with the same minimal contact (exactly matched) as the shCBT to remove any potential “non-specific” attention effects. Moreover, these procedures closely resemble the manner in which medications are generally delivered in “real-world” primary care settings which involves far less physician contact than research trials (Wadden et al., 2005; Wilfley et al., 2008).

Statistical Analyses

Analyses designed to compare treatments were performed for all randomized patients (intent-to-treat). Baseline characteristics (demographic, psychiatric, and clinical variables) for the treatment groups were compared using chi-square analyses for categorical variables and ANOVAs for continuous measures.

The two primary treatment outcome variables were binge eating and weight loss, which were analyzed using complementary approaches. “Remission” from binge eating (zero binges (OBEs) during previous 28 days on the EDE) and “percent weight loss” were defined separately at each of the post-treatment and 6- and 12-month follow-ups. For calculation of “remission,” for treatment dropouts and instances of missing data, pre-treatment baseline data were carried forward. Treatment groups were compared using generalized estimating equations (GEE), which account for correlations within individuals, for “remission” and mixed models (SAS PROC MIXED) that use all available data throughout the study without imputation for “percent weight loss.” Post-hoc treatment comparisons were performed at each time point.

Treatment groups were also compared on “frequency” of binge eating (OBEs during previous 28 days on the EDE) and “percent weight loss.” Mixed models compared treatments on “frequency” of binge eating (baseline, post-treatment, and at 6- and 12-month follow-ups) and percent weight loss (based on weight measured every two weeks throughout treatments, and at post-treatment, 6- and 12-month follow-ups). We provide BMI data in the Tables for descriptive purposes (i.e., it is a useful measure of obesity, is a good estimate of body fat and gauge of medical risk, and can be used for most men and women) in addition to weight data. We report analyses for percent weight loss for their “clinical usefulness” (although analyses of percent BMI loss yielded the same exact findings). Secondary outcomes, which included continuous measures of eating disorder psychopathology (EDE global score) and depression levels (BDI total score) at post-treatment and 6- and 12-month follow-ups, were also compared across treatments using mixed models.

In each mixed model, fixed effects of shCBT (yes, no), medication (sibutramine, placebo), time (with the relevant time points for each measure as described above), all possible interactions, and random subject-level effects were considered. Distributions of all data were examined and transformations were applied if necessary to satisfy model assumptions (e.g., OBE (binge) frequency data were log-transformed) although the tables show untransformed values. For each model, different variance-covariance structures (unstructured, autoregressive with and without heterogeneous variances, compound symmetry with and without heterogeneous variances) were evaluated and the best-fitting structure was selected based on Schwartz Bayesian criterion (BIC).

Lastly, given recent findings regarding the potential prognostic significance of demographic factors (Thompson et al., 2013), we performed analyses to examine selected demographic variables (age, sex, race, and education) as predictors and moderators of clinical outcomes (binge eating and eating disorder psychopathology, and percent weight loss). GEE was used to analyze the binary binge eating remission variable at post-treatment and at the two follow-ups. Mixed model analyses were used to analyze the continuous outcome variables (binge-eating frequency, eating disorder psychopathology (EDE global score), and percent weight loss). In each mixed model, the fixed effects of shCBT (yes, no), sibutramine (yes, no), time (all assessment points), the potential predictor/moderator variable (age, sex, race, or education), and all possible interactions were tested. All data for all participants were used in these analyses, except for the analysis of race effects which was restricted to African American (N=36) and White (N=47) participants (given the relatively small number of Hispanic (N=14) participants).

Results

Randomization and Patient Characteristics

Of the 104 randomized patients, 26 received sibutramine, 27 received placebo, 26 received shCBT+sibutramine, and 25 received shCBT+placebo. Overall, 74% (N=77/104) of patients completed treatments; completion rates across treatments were: 76.6% (N=20/26) for sibutramine, 51.9% (N=14/27) for placebo, 84.6% (N=22/26) for shCBT+sibutramine, and 95.5% (N=21/25) for shCBT+placebo. Chi-square analyses revealed significant differences in treatment completion across conditions (X2(3)=9.83, p=0.02), with the placebo-only condition having higher dropout than other treatments. Post-treatment assessments were obtained for 84% of patients and follow-up assessments were obtained for 83% of patients at the 6-month follow-up and for 86% of patients at the 12-month follow-up (Figure 1). Chi-square analyses revealed no significant differences or trends in assessment rates for the treatment groups at any post-treatment or follow-up time point. Treatment groups did not differ significantly in age, gender, race/ethnicity, or psychiatric variables (Table 1) or on pretreatment levels of any outcome variables (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the 104 Randomized Patients Across the Four Treatments

| Variable | Placebo (N= 27) | Sibutramine (N= 26) | shCBT + Placebo (N= 25 ) | shCBT+ Sibutramine (N= 26) | Test statistic | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 43.2 (12.4) | 41.2 (10.3) | 45.7 (12.4) | 45.6 (9.4) | F(3,100)=0.97 | .41 |

| Female, N (%) | 18 (66.7) | 19 (73.1) | 20 (80.0) | 16 (61.5) | X2(3)=2.34 | .50 |

| Ethnicity, N (%) | ||||||

| Caucasian | 12 (44.4) | 13 (50.0) | 12 (48.0) | 10 (38.5) | X2(9)=4.98 | .84 |

| African-American | 12 (44.4) | 8 (30.8) | 6 (24.0) | 10 (38.5) | ||

| Hispanic-American | 2 ( 7.4) | 4 (15.4) | 4 (16.0) | 4 (15.4) | ||

| Other | 1 ( 3.7) | 1 ( 3.8) | 3 (12.0) | 2 ( 7.7) | ||

| Education, N (%) | X2(3)=7.95 | .05 | ||||

| College degree | 5 (18.5) | 11 (42.3) | 14 (56.0) | 10 (38.5) | ||

| No college degree | 22 (81.5) | 15 (57.7) | 11 (44.0) | 16 (61.5) | ||

| DSM-IV co-morbidity, N (%) | ||||||

| Mood disorders | 14 (51.9) | 11 (42.3) | 11 (44.0) | 12 (46.2) | X2(6)=4.55 | .60 |

| Anxiety disorders | 11 (40.7) | 8 (30.8) | 9 (36.0) | 9 (34.6) | X2(6)=0.84 | .91 |

| Substance use disorders | 7 (25.9) | 6 (23.1) | 5 (20.0) | 5 (19.2) | X2(6)=3.49 | .76 |

| Age onset BED, mean (SD) | 25.5 (11.1) | 25.7 (11.2) | 25.7 (15.1) | 29.1 (13.3) | F(3, 97)=0.48 | .70 |

Note: Test statistic = chi-square for categorical variables and ANOVAs for dimensional variables. P values are for two-tailed tests.

SD = standard deviation. N = number. BED = binge eating disorder.

Table 2.

Clinical Variables Across the Four Treatments at the Major Assessment Points

| Variable | Pre-treatment | Post-treatment | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (N=26) | Sibutramine (N=27) | shCBT + Placebo (N=26) | shCBT + Sibutramine (N=25) | Placebo (N=22) | Sibutramine (N=20) | shCBT + Placebo (N=23) | shCBT + Sibutramine (N=22) | |||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Binge episodes/month (EDE) | 21.1 | 19.2 | 22.4 | 19.0 | 14.6 | 12.8 | 16.9 | 13.0 | 5.3 | 9.9 | 5.0 | 11.4 | 6.4 | 7.6 | 3.6 | 8.0 |

| EDE Global Score | 2.6 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 0.9 | 2.5 | 0.8 | 2.1 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 0.8 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 0.9 |

| Depression (BDI) | 13.6 | 11.2 | 12.8 | 8.1 | 17.0 | 11.6 | 14.0 | 7.2 | 9.6 | 11.3 | 7.9 | 7.7 | 9.8 | 9.7 | 9.3 | 6.2 |

| Body mass index | 39.3 | 5.5 | 39.4 | 6.6 | 36.5 | 5.3 | 37.8 | 4.6 | 39.6 | 5.7 | 38.4 | 7.2 | 35.9 | 5.6 | 35.6 | 4.6 |

| Weight (pounds) | 244.5 | 41.4 | 254.8 | 53.4 | 229.6 | 41.9 | 234.5 | 37.5 | 246.6 | 42.0 | 250.0 | 61.4 | 226.2 | 40.4 | 220.9 | 35.6 |

| Variable | 6-month follow-up | 12-month follow-up | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (N=22) | Sibutramine (N=21) | shCBT + Placebo (N=23) | shCBT + Sibutramine (N= 23) | Placebo (N= 23) | Sibutramine (N=18) | shCBT + Placebo (N=21) | shCBT + Sibutramine (N=23) | |||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Binge episodes/month (EDE) | 5.7 | 10.0 | 4.9 | 6.1 | 3.6 | 6.4 | 3.9 | 9.5 | 6.7 | 13.9 | 5.8 | 8.7 | 4.9 | 8.5 | 3.0 | 7.4 |

| EDE Global Score | 1.8 | 1.0 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 1.0 |

| Depression (BDI) | 8.7 | 9.9 | 9.7 | 8.5 | 10.3 | 10.6 | 9.8 | 6.7 | 7.5 | 6.9 | 10.1 | 8.3 | 10.5 | 9.1 | 10.3 | 7.3 |

| Body mass index | 38.8 | 5.1 | 38.7 | 6.2 | 35.3 | 5.2 | 36.0 | 5.0 | 39.5 | 5.9 | 39.3 | 7.7 | 35.4 | 5.9 | 36.5 | 5.3 |

| Weight (pounds) | 239.9 | 38.0 | 246.8 | 46.2 | 223.4 | 40.4 | 221.8 | 39.1 | 246.0 | 44.2 | 251.5 | 53.4 | 220.5 | 42.7 | 223.6 | 40.2 |

Note: Entries are actual raw data without any transformation or imputation. M = mean. SD = standard deviation. EDE = Eating Disorder Examination. BDI = Beck Depression Inventory.

Binge Eating Remission and Frequency

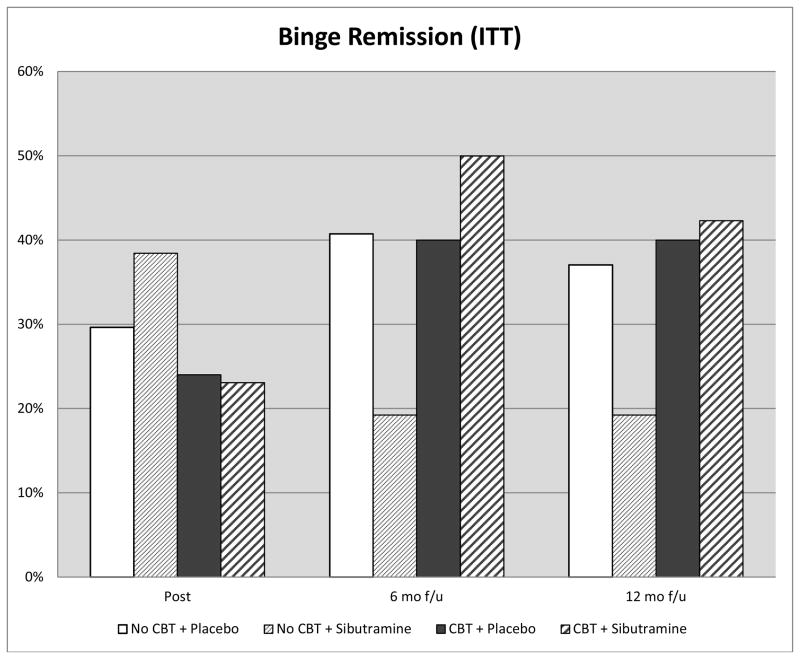

Figure 2 shows “remission” rates across the treatment conditions at post-treatment and 6- and 12-month follow-ups. In GEE analyses, there was a significant 2-way interaction between shCBT and time (X2(2)=7.22, p=0.03), none of the post-hoc tests, however, were significant. A parallel set of GEE analyses comparing the four specific treatment groups on remission rates also revealed no significant effects. At post-treatment, remission rates which were 29.6% (for placebo-only), 38.5% (for sibutramine-only), 24% (for shCBT+placebo), and 23.1% (for shCBT+sibutramine) did not differ significantly across treatments (X2(3)=1.89, p=0.60, phi=0.14). At 6-month follow-up, remission rates which were 40.7% (for placebo-only), 19.2% (for sibutramine-only), 40% (for shCBT+placebo), and 50.0% (for shCBT+sibutramine), did not differ significantly across treatments (X2(3)=5.62, p=0.13, phi=0.23). At 12-month follow-up, remission rates which were 37.0% (for placebo-only), 19.2% (for sibutramine-only), 40% (for shCBT+placebo), and 42.3% (for shCBT+sibutramine), did not differ significantly across treatments (X2(3)=3.79, p=0.29, phi=0.19).

Figure 2.

Percentage of participants across the four conditions who achieved remission from binge eating at post-treatment and at 6-month and 12-month follow-up assessments after treatment discontinuation (i.e., 10- and 16-months after randomization). Data are for all randomized participants (N=104). Remission was defined at zero binge eating episodes (OBE) for the past month based on the Eating Disorder Examination interview.

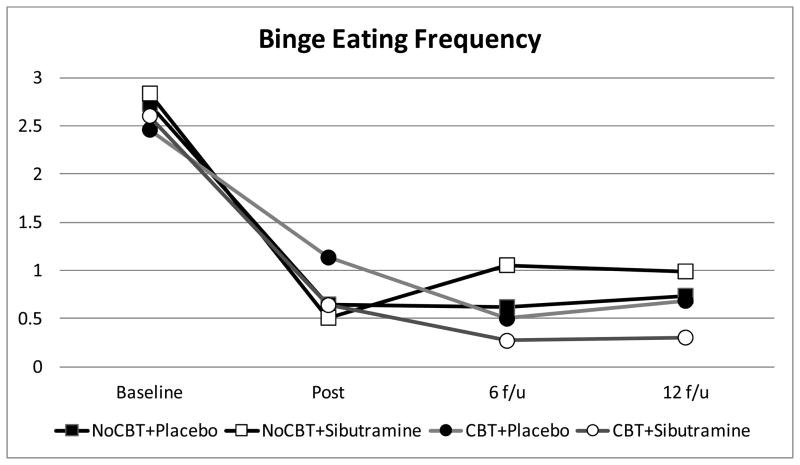

Table 2 summarizes binge eating frequency (actual monthly raw values without imputation) based on the EDE interview for the four treatment conditions across the main study time-points (baseline, post-treatment, and 6- and 12-month follow-ups). Figure 3 summarizes monthly frequency of binge eating across the four conditions across time-points based on estimated marginal means (derived from mixed models analyses) of log-transformed OBE data for all participants. Mixed models analysis revealed a significant main effect of time (F(3,126)=109.4, p<0.0001) and a marginal but not statistically significant interaction between shCBT and time (F(3,126)=2.6, p=0.055). Posthoc tests revealed that participants receiving shCBT had lower frequency of binge eating at 6-month follow-up (F(1,103)=4.5, p=0.04) but not at the other time points.

Figure 3.

Monthly frequency of binge eating by participants across the four conditions at baseline, post-treatment, and 6- and 12-month follow-ups after treatment discontinuation (i.e., 10- and 16-months after randomization). The data shown are based on estimated marginal means (derived from mixed models analyses) of log-transformed binge eating (OBE frequency) data for all N=104 participants based on the Eating Disorder Examination interview.

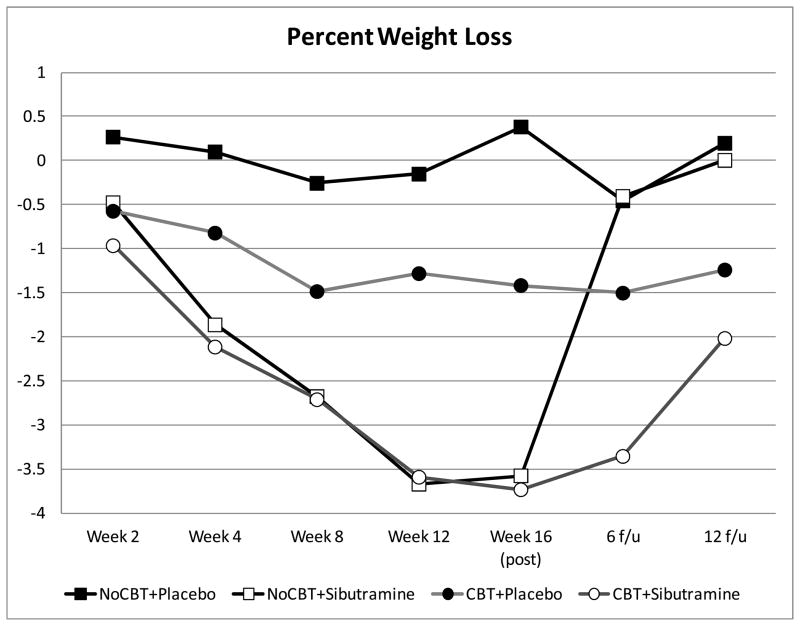

Percent Weight Loss

Figure 4 displays the percent weight loss data shown monthly throughout treatment and at post-treatment and follow-up assessments, and Table 2 summarizes weight (and BMI) data at the four major assessment points (baseline, post-treatment, and 6- and 12-month follow-ups).

Figure 4.

Percentage weight loss by participants across the four conditions at throughout treatment, post-treatment, and 6- and 12-month follow-ups after treatment discontinuation (i.e., 10- and 16-months after randomization).

Mixed models revealed a significant time effect (F(6,182)=5.7, p<0.0001 and a significant interaction effect between sibutramine and time (F(6,182)=4.0, p=0.0009). Percent weight loss over time was statistically significant for subjects receiving sibutramine (F(6,253)=9.7, p<0.0001) but not for subjects receiving placebo (F(6,251)=0.2, p=0.98). Differences between sibutramine and placebo were statistically significant at months 1, 2, 3, and 4 (at post-treatment); weight regain occurred after treatment and the different conditions no longer differed significantly by 6- and 12-month follow-ups.

Associated Eating Disorder Psychopathology and Depression Levels

Table 2 shows the continuous measure of eating disorder psychopathology (EDE global score) and depression (BDI) levels across treatments at the major assessment points. Mixed models analyses revealed significant time effects (improvements) for eating disorder psychology (F(3,249)=37.6, p<0.0001) and depression (F(6,482)=13.0, p<0.0001) but no significant differences among the treatments.

Testing Demographic Variables as Predictors/Moderators of Clinical Outcomes

GEE and mixed models analyses revealed no significant effects for age, sex, race, or education as either predictors or moderators for any of the main clinical outcomes (binge-eating remission, binge-eating frequency, eating-disorder psychopathology (EDE global), and percent weight loss).

Discussion

The objective was to determine whether treatments with demonstrated efficacy for binge eating disorder (BED) in specialist treatment centers can be delivered effectively in primary care settings to racially and ethnically diverse group of obese patients with BED. This study compared the effectiveness of self-help cognitive behavioral therapy (shCBT) and an anti-obesity medication (sibutramine), alone and in combination, and it is only the second placebo-controlled trial of any medication for BED to evaluate longer-term effects after treatment discontinuation. Our findings suggest that pure self-help CBT and sibutramine did not show longer-term effectiveness relative to placebo for treating BED in racially/ethnically diverse obese patients in primary care. Overall, the treatments differed little with respect to binge-eating and associated outcomes. Sibutramine was associated with significantly greater acute weight loss than placebo and the observed weight-regain following discontinuation of medication suggests that anti-obesity medications need to be continued for weight loss maintenance. Demographic factors did not significantly predict or moderate clinical outcomes in this diverse patient group.

Binge-eating remission rates were not significantly different across treatments (29.6% for placebo-only, 38.5% for sibutramine-only, 24% for shCBT+placebo, and 23.1% for shCBT+sibutramine). The substantial placebo-response among patients with BED has been previously noted in placebo-controlled trials for sibutramine (Wilfley et al., 2008) and across trials testing various other medications (Reas & Grilo, 2008). Reas & Grilo (2008), in a meta-analysis of 14 placebo-controlled trials, reported a 28.5% remission rate for placebo across studies. Two previous controlled trials in specialist centers testing sibutramine (Appolinario et al., 2003; Wilfley et al., 2008) reported a statistical advantage relative to placebo for reducing binge-eating frequency and one trial (Wilfley et al., 2008) reported that sibutramine was associated with significantly higher remission rate than placebo. Specifically, Wilfley et al (2008) reported remission rates (defined as two weeks without any binge-eating episodes) of 44.1% for patients receiving sibutramine and 30.3% for patients receiving placebo. Thus, our observed remission rate (defined as four weeks without any binge-eating episodes) of 38.5% (for sibutramine) is only slightly lower and 29.6% (for placebo) is nearly identical to those reported by Wilfley et al (2008). In our trial, the completion rates of 76.6% of patients receiving sibutramine and 51.9% of patients receiving placebo were comparable to the rates of 66.1% and 57.2% in the Wilfley et al (2008) study. The statistically significant advantage in remission rates for sibutramine over placebo (i.e., 12.8% difference) in the Wilfley et al (2008) study perhaps reflects the statistical power afforded by the much larger sample (i.e., N=304); from a clinical perspective, however, the magnitude of the effect was small.

Our observed 24% binge-eating remission rate for shCBT+placebo is slightly higher than the 17.9% remission rate for shCBT reported by Peterson and colleagues (2009) in a specialist setting and lower than the 43% rate reported by Carter and Fairburn (1998) in a community-based setting. Our remission rate for shCBT falls within the range reported by various controlled studies comparing it to “guided-” and therapist-administered CBT methods (see Sysko & Walsh, 2008). Our findings regarding the lack of effectiveness for shCBT relative to placebo for BED is consistent with the Peterson et al (2009) trial in which shCBT was not superior to wait-list control, although two smaller earlier studies did report an advantage for shCBT relative to wait-list. Our finding that sibutramine did not enhance shCBT binge-eating outcomes is consistent with the existing literature in that all previous controlled trials failed to find a significant “additive” effect for reducing binge-eating by combining medication and a behavioral treatment (Claudino et al., 2007; Devlin et al., 2005; Grilo, Crosby, et al. 2012; Grilo, Masheb, & Salant, 2005; Grilo, Masheb, & Wilson, 2005).

In terms of weight loss, we observed statistically significant percent weight loss for patients receiving sibutramine but not for those receiving placebo and that sibutramine was significantly superior to placebo for achieving weight loss after one month and continuing throughout the course of treatment. These findings are consistent with those previously reported by two trials (Appolinario et al., 2003; Wilfley et al., 2008) and the weight loss trajectories are nearly identical to those reported in the Wilfley et al (2008) trial. We also found that once medication is stopped, weight regain occurred and the treatment conditions no longer differed significantly by 6- and 12-month follow-ups. These findings suggest that anti-obesity medications likely need to be continued over longer periods of time for weight loss maintenance as is the treatment approach in the obesity field (Wadden et al., 2005). Our finding that sibutramine enhanced shCBT weight loss outcomes is consistent with two previous studies reporting significant “additive” effects by combining certain specific medications with weight-loss effects (e.g., orlistat, topiramate) and “guided” CBT treatments for BED (Claudino et al., 2007; Grilo, Masheb, & Salant, 2005).

Comparisons with the existing treatment literature, as offered descriptively for context above, can only be made cautiously given potentially important differences between generalist and specialist treatment settings and providers. For example, we note striking differences in findings from two RCTs testing self-help CBT methods and fluoxetine treatments for bulimia nervosa performed in specialty (Mitchell et al., 2001) versus in primary care (Walsh et al., 2004) settings, with the latter study reporting much higher dropout and much poorer outcomes than the former study. Second, we highlight that our patient group had much greater racial and ethnic diversity than the previous trials (see Franko et al., 2012). Thompson-Brenner et al (2013) reported that, for CBT treatments, lower education predicted poorer binge-eating outcomes and African Americans had greater reductions in eating disorder psychopathology than did Caucasian, although most analyses revealed non-significant findings for demographic features as predictors of outcomes. Grilo, Masheb, & Crosby (2012) reported that several demographic variables (age, sex, and education) predicted and/or moderated a number of clinical outcomes in a trial performed in a specialty clinic testing anti-depressant medication and CBT. In the present study, demographic variables (age, sex, race, and education) did not predict or moderate the various main clinical outcomes tested. These null findings for demographic factors are unlikely attributable to limited variability given the diversity of our participants on most variables but could perhaps reflect limited power to detect smaller effects. Alternatively, the findings might simply suggest that demographic factors play little role in predicting outcomes from these low intensity treatments that differed little from one another in generalist settings. Further research with larger diverse study groups and more intensive treatments is needed to examine these issues.

We note several potential limitations of our study as further context for our findings. We acknowledge the possible issue of limited statistical power to detect significant small differences between treatments; however, clinical inspection of the binge-eating outcomes suggests no meaningful separation between treatments. Our study tested the anti-obesity medication sibutramine, which has been withdrawn from the market. The findings, however, have heuristic and clinical value. Our follow-up period after medication discontinuation demonstrated that anti-obesity medication likely requires on-going dosing as is the case in the obesity field (e.g., Wadden et al., 2005) but is not reflected in the BED field (e.g., Grilo et al., 2012). The findings highlight the need for medication trials for BED to include follow-up designs in order to determine maintenance effects to inform clinical prescription. Additionally, even if the sibutramine/placebo findings are “clinically” irrelevant they represent a powerful methodological active comparison condition for interpreting the effects shCBT (Freedland et al., 2011).

In closing we conclude that pure shCBT may not suffice as a “front-line” intervention for BED for obese patients in primary care. Future studies should test guided self-help methods for delivering CBT in such generalist settings. Future research should address both scalability of treatments and training methods for delivering treatments.

Highlights.

RCT testing anti-obesity medication (sibutramine) and self-help CBT for binge eating disorder in primary care.

Racially- and ethnically-diverse obese patients with binge eating disorder.

Self-help CBT and sibutramine did not show long-term effectiveness relative to placebo for treating BED.

Demographic factors did not predict or moderate clinical outcomes.

Future studies should test more intensive guided-self-help.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 DK073542. Dr. Grilo was also supported by NIH grant K24 DK070052. Dr. Barnes was also supported by NIH grant K23 DK092279.

Footnotes

When this study was designed, the DSM-5 criteria for BED were well researched but not yet finalized. In order to be able to address both criteria for DSM-IV-TR and the likely criteria for DSM-5, we included both the longer duration criterion (six months or greater) and both frequency criteria (i.e., at least twice weekly from the DSM-IV-TR and at least once weekly anticipated for the DSM-5). This provided us the ability to stratify randomization by meeting DSM-IV-TR “full” criteria (binge-eating frequency at least twice weekly) and “subthreshold” criteria (binge-eating frequency at least once weekly) which was consistent with the literature at the time and ultimately allowed us to meet DSM-5 criteria.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alegria M, Woo M, Cao Z, Torres M, Meng XL, Striegel-Moore RH. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in Latinos in the United States. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40(suppl):S15–21. doi: 10.1002/eat.20406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. (DSM-5) [Google Scholar]

- Appolinario JC, Bacaltchuk J, Sichieri R, Claudino AM, Godoy-Matos A, Morgan C, Zanella MT, Coutinho W. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of sibutramine in the treatment of binge-eating disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:1109–1116. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.11.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes RD, Blomquist KK, Grilo CM. Exploring pretreatment weight trajectories in obese patients with binge eating disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2011;52:312–318. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer R, Garbin M. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: 25 years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review. 1998;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer R. Manual for revised Beck Depression Inventory. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Carter JC, Fairburn CG. Cognitive-behavioral self-self for binge eating disorder: A controlled effectiveness study. Journal Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:616–623. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claudino AM, de Oliveira IR, Appolinario JC, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy guided self-help and orlistat for the treatment of binge eating disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;57:1193–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin MJ, Goldfein JA, Petkova E, Jiang H, Raizman PS, Wolk S, Mayer L, Carino J, Bellace D, Kamenetz C, Dobrow I, Walsh BT. Cognitive behavioral therapy and fluoxetine as adjuncts to group behavioral therapy for binge eating disorder. Obesity Research. 2005;13:1077–1088. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. The Eating Disorder Examination. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge eating: nature, assessment, and treatment. 12. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 317–360. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Marcus MD, Wilson GT. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for binge eating and bulimia nervosa: a comprehensive treatment manual. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge eating: nature, assessment, and treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 361–404. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders - patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Franko DL, Thompson-Brenner H, Thompson DR, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in adults in randomized clinical trials of binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:186–195. doi: 10.1037/a0026700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedland KE, Mohr DC, Davidson K, Schwartz JE. Usual and unusual care: existing practice control groups in randomized controlled trials of behavioral interventions. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2011;73:323–335. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318218e1fb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Crosby RD, Masheb RM, White MA, Peterson CB, Wonderlich SA, Engel SJ, Crow SJ, Mitchell JE. Overvaluation of shape and weight in binge eating disorder, bulimia nervosa, and sub-threshold bulimia nervosa. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47:692–696. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Crosby RD, Wilson GT, Masheb RM. 12-Month follow-up of fluoxetine and cognitive behavioral therapy for binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:1108–1113. doi: 10.1037/a0030061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Hrabosky JI, White MA, Allison KC, Stunkard AJ, Masheb RM. Overvaluation of shape and weight in binge eating disorder and overweight controls: refinement of BED as a diagnostic construct. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:414–419. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Lozano C, Elder KA. Inter-rater and test-retest reliability of the Spanish Language Version of the Eating Disorder Examination Interview: Clinical and research implications. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2005;11:231–240. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200507000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Lozano C, Masheb RM. Ethnicity and sampling bias in binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2005;38:257–262. doi: 10.1002/eat.20183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM. A randomized controlled comparison of guided self-help cognitive behavioral therapy and behavioral weight loss for binge eating disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43:1509–1525. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Crosby RD. Predictors and moderators of response to cognitive behavioral therapy and medication for the treatment of binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:897–906. doi: 10.1037/a0027001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Lozano-Blanco C, Barry DT. Reliability of the Eating Disorder Examination in patients with binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2004;35:80–85. doi: 10.1002/eat.10238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Salant SL. Cognitive behavioral therapy guided self-help and orlistat for the treatment of binge eating disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57:1193–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. A comparison of different methods for assessing the features of eating disorders in patients with binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:317–322. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy and fluoxetine for the treatment of binge eating disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled comparison. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT, Gueorguieva R, White MA. Cognitive- behavioral therapy, behavioral weight loss, and sequential treatment for obese patients with binge-eating disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:675–685. doi: 10.1037/a0025049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, White MA, Masheb RM. DSM-IV psychiatric disorder comorbidity and its correlates in binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2009;42:228–234. doi: 10.1002/eat.20599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart LM, Granillo MT, Jorm AF, Paxton SJ. Unmet need for treatment in the eating disorders: a systematic review of eating disorder specific treatment seeking among community cases. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31:727–735. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbert A, Bishop M, Stein R, Wilfley DE. Long-term efficacy of psychological treatments for binge eating disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;200:232–237. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.089664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survery Replication. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61:348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James WP, Caterson ID, Coutinho W, et al. SCOUT investigators. Effect of sibutramine on cardiovascular outcomes in overweight and obese subjects. New England Journal of Medicine. 363:905–917. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. Health problems, impairment and illnesses associated with bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder among primary care and obstetric gynaecology patients. Psychological Medicine. 2001;31:1455–66. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Blase SL. Rebooting psychotherapy research and practice to reduce the burden of mental illness. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2011;6:21–37. doi: 10.1177/1745691610393527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques L, Alegria M, Becker AE, Chen CN, Fang A, Chosak A, Diniz JB. Comparative prevalence, correlates of impairment, and service utilization for eating disorders across US ethnic groups: implications for reducing ethnic disparities in health care access for eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2011;44:412–420. doi: 10.1002/eat.20787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JE, Fletcher L, Hanson K, Mussell MP, Seim H, Crosby RD, Al-Banna M. The relative efficacy of fluoxetine and manual-based self-help in the treatment of outpatients with bulimia nervosa. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2001;21:298–304. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200106000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mond JM, Myers TC, Crosby RD, Hay PJ, Mitchell JE. Bulimic eating disorders in primary care: hidden mortality still? Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2010;17:56–63. doi: 10.1007/s10880-009-9180-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) NICE Clinical Guideline No. 9. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence; 2004. Eating Disorders – Core Interventions in the treatment and management of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, related eating disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CB, Mitchell JE, Crow SJ, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA. The efficacy of self-help group treatment and therapist-led group treatment for binge eating disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:1347–1354. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09030345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CB, Mitchell JE, Engbloom S, Nugent S, Mussell MP, Miller JP. Group cognitive-behavioral treatment of binge eating disorder: a comparison of therapist-led versus self-help formats. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1998;24:125–136. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199809)24:2<125::aid-eat2>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reas DL, Grilo CM. Review and meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy for binge-eating disorder. Obesity. 2008;16:2024–2038. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reas DL, Grilo CM. Current and emerging drug treatments for binge eating disorder. Expert Opinion on Emerging Drugs. 2014;19:99–142. doi: 10.1517/14728214.2014.879291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricca V, Mannucci E, Mezzani B, Moretti S, Di Bernardo M, Bertelli M, et al. Fluoxetine and fluvoxamine combined with individual cognitive-behaviour therapy in binge eating disorder: a one-year follow-up study. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2001;70:298–306. doi: 10.1159/000056270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafran R, Clark DM, Fairburn CG, et al. Mind the gap: improving the dissemination and implementation of CBT. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47:902–909. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sysko R, Walsh BT. A critical evaluation of the efficacy of self-help interventions for the treatment of bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2008;41:97–112. doi: 10.1002/eat.20475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson-Brenner H, Franko DL, Thompson DR, Grilo CM, Boisseau CL, Roehrig JP, Wilson GT. Race/ethnicity, education, and treatment parameters as moderators and predictors of outcome in binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013 doi: 10.1037/a0032946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadden TA, Berkowitz RI, Womble LG, Sarwer DB, Phelan S, Cato RK, Hesson LA, Osei SY, Kaplan R, Stunkard AJ. Randomized trial of lifestyle modification and pharmacotherapy for obesity. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353:2111–2120. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh BT, Fairburn CG, Mickley DE, Sysko R, Parides MK. Treatment of bulimia nervosa in a primary care setting. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:556–561. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilfley DE, Crow SJ, Hudson JI, Mitchell JE, Berkowitz RI, Blakesley V, Walsh BT Sibutramine Binge Eating Disorder Research Group. Efficacy of sibutramine for the treatment of binge eating disorder: A randomized multi-center placebo-controlled double-blind study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:51–58. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06121970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Grilo CM, Vitousek KM. Psychological treatments of eating disorders. American Psychologist. 2007;62:199–216. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Zandberg LJ. Cognitive-behavioral guided self-help for eating disorders: effectiveness and scalability. Clinical Psychology Review. 2012;32:343–357. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]