Abstract

Objective

The objective of this article is to comprehensively review the scientific literature and summarize the available data regarding the outcome disparities of African American women with uterine cancer.

Methods

Literature on disparities in uterine cancer was systematically reviewed using the PubMed search engine. Articles from 1992-2012 written in English were reviewed. Search terms included endometrial cancer, uterine cancer, racial disparities, and African American.

Results

Twenty-four original research articles with a total of 366,299 cases of endometrial cancer (337,597 Caucasian and 28,702 African American) were included. Compared to Caucasian women, African American women comprise 7% of new endometrial cancer cases, while accounting for approximately 14% of endometrial cancer deaths. They are diagnosed with later stage, higher-grade disease, and poorer prognostic histologic types compared to their Caucasian counterparts. They also suffer worse outcomes at every stage, grade, and for every histologic type. The cause of increased mortality is multifactorial. African American and white women have varying incidence of comorbid conditions, genetic susceptibility to malignancy, access to care and health coverage, and socioeconomic status; however, the most consistent contributors to incidence and mortality disparities are histology and socioeconomics. More robust genetic and molecular profile studies are in development to further explain histologic differences.

Conclusions

Current studies suggest that histologic and socioeconomic factors explain much of the disparity in endometrial cancer incidence and mortality between white and African American patients. Treatment factors likely contributed historically to differences in mortality; however, studies suggest most women now receive equal care. Molecular differences may be an important factor to explain the racial inequities. Coupled with a sustained commitment to increasing access to appropriate care, on-going research in biologic mechanisms underlying histopathologic differences will help address and reduce the number of African American women who disproportionately suffer and die from endometrial malignancy.

Keywords: Uterine cancer, Race, Health disparities

Introduction

African Americans fare worse than whites across a spectrum of diseases, including diabetes, heart disease, and various malignancies. Gynecologic cancers are not immune to this phenomenon, as studies have universally shown poorer outcomes for African American women with endometrial, cervical, and ovarian malignancies [1]. Endometrial cancer exhibits particularly striking racial differences. Despite a 30% decreased incidence among African American patients, those who are diagnosed with endometrial cancer are 2.5 times more likely to die than their Caucasian counterparts [2]. Though the explanation for this is likely multi-factorial, histopathologic disparities, with aggressive subtypes more common in African Americans, and socioeconomic differences, causing decreased access to healthcare among minority patients, are often assigned the largest roles. Other studies have examined molecular and genetic alterations, increased prevalence of comorbidities, and inconsistencies in treatment patterns among different races in an attempt to explain the inequalities. The purpose of this review is to examine the current body of literature in order to identify clinical, biological, and socioeconomic areas where disparities exist and identify ways to address these inequalities. Forty-two studies were initially identified, and 24 were reviewed after exclusion of studies that did not specifically address the disparities between African Americans and Caucasians with endometrial cancer. The reviewed studies had a total of 366,299 cases of endometrial cancer (337,597 Caucasian and 28,702 African American) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cases of endometrial cancer by study and race

| Type of Study | Caucasian (N) | African American (N) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sherman et al. (6) | SEER (1992-1998) | 16,512 | 1,844 |

| Setiawan et al. (7) | Prospective cohort | 104 | 55 |

| Hicks et al. (9) | National Cancer Database (1988-1994) | 52,307 | 3,226 |

| Duong et al. (10) | National Program of Cancer Registries and SEER (1999-2006) | 143,406 | 10,969 |

| Wright et al. (11) | SEER (1988-2004) | 69,956 | 5,564 |

| Smotkin et al. (11) | Single-institution | 382 | 308 |

| Oliver et al. (13) | Department of Defense Tumor Registry (1990-2003) | 2,057 | 183 |

| Al-Wahab et al. (14) | Multi-institution | 65 | 107 |

| Fleury et al. (15) | Single-state population database | 4,173 | 989 |

| Risinger et al. (16) | Single-institution | 99 | 34 |

| Maxwell et al. (19) | Single-institution | 78 | 62 |

| Basil et al. (20) | Single-institution | 189 | 39 |

| Kohler et al. (21) | Single-institution | 129 | 47 |

| Clifford et al. (22) | Single-institution | 117 | 44 |

| Santin et al. (24) | Single-institution | 17 | 10 |

| Allard et al. (25) | Single-institution | 105 | 26 |

| Ferguson et al. (26) | Single-institution | 25 | 14 |

| Maxwell et al. (27) | Clinical trial data | 1,049 | 110 |

| Fedewa et al. (31) | National Cancer Database (2000-2001) | 30,495 | 3,071 |

| Madison et al. (32) | SEER (1990-1998) | 3,168 | 488 |

| Matthews et al. (33) | Single-institution | 153 | 229 |

| Olson et al. (35) | SEER-Medicare (2005-2005) | 11,610 | 958 |

| Trimble et al. (36) | SEER (1998) | 419 | 156 |

| Farley et al. (37) | Clinical trial data | 982 | 169 |

| Total | 366,299 | 337,597 | 28,702 |

Incidence

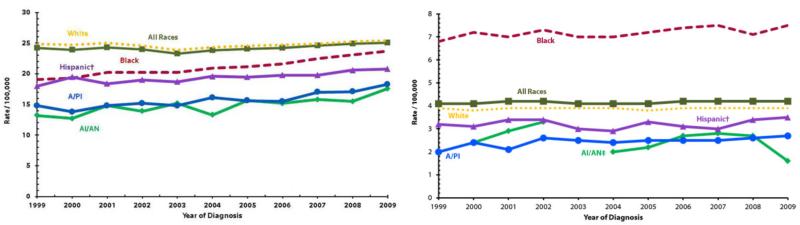

Though African American women have a 7% lower incidence rate of all cancers when compared to white women, their overall cancer-related death rate is 17% higher. This discrepancy is seen in a variety of cancers including breast cancer and colorectal cancer [3, 4]. In endometrial cancer, the disparity is considerably more pronounced, as the incidence in African Americans is 30% lower and the mortality rate 80% higher when compared to whites [1]. Figure 1 shows the trend in incidence and mortality of endometrial cancer in the United States over the last decade [5]. Several studies utilizing large databases have shown the disparate incidence of uterine cancer among different races. One study of SEER data from 1992-1998, including 1,844 African American and 16,512 Caucasian women, found the overall incidence of endometrial cancer in African Americans to be only 65% of that in Caucasians, while the incidence rates of more aggressive subtypes (serous and clear cell adenocarcinomas and sarcomas) in African American patients were 1.56 to 2.33 times those seen in whites [6]. The Multiethnic Cohort Study found overall incidence in African Americans to be 76% of that in whites but found African American rates of more aggressive subtypes to be over three times higher [7], confirming findings from other studies [8, 9]. A more recent study examining trends in endometrial cancer incidence from 1999 to 2006 found an even larger gap in incidence with African American women representing only 6.8% of all endometrial cancers and 17.4% of type II endometrial cancers [10]. This dramatic difference in incidence rates (when compared to other studies in this review) is presumably due to the 60.9% increase in incidence of type I endometrial cancer (where African Americans are under-represented) observed during the study period. Type II cancers (where African Americans are disproportionally represented) did not significantly increase during this time. A sustained increase in type I endometrial cancer will further widen the gap in incidence between Caucasian and African American populations.

Figure 1.

Uterine cancer incidence (left) and mortality (right) rates by race and ethnicity in the United States, 1999-2009. Rates are per 100,000 persons and are age-adjusted to the 2000 U.S. standard population (19 age groups – Census P25-1130). Incidence rates cover approximately 90% of the U.S. population.

† Hispanic origin is not mutually exclusive from race categories (white, black, A/PI = Asian/Pacific Islander, AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native). (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013)

Histopathologic Factors and Stage at Presentation

Five population-based studies and one large single-institution study documented the racial disparity in endometrial cancer histology and stage at presentation (Tables 2 and 3) [6, 7, 9, 11-13]. Though only one of these studies was a prospective analysis [7], all utilized large sample populations and reported similar rates of each cancer subtype across ethnic groups. They showed that African American patients are less likely than Caucasians to present with endometrioid histology and more likely to present with less favorable subtypes (sarcomas, clear cell carcinomas, serous carcinomas, and carcinosarcomas) and higher-grade tumors. In a 2003 study of 36,712 cases from the SEER database, African American patients were three times more likely to present with an unfavorable subtype when compared to Caucasians and had an associated five year survival 40-50% lower among patients with the endometrioid subtype. An analysis of SEER data (1998-2004) of 80,915 women found endometrioid histology in 85% of white women but only 62% of African American women. In contrast, African American patients were more likely than white patients to have uterine sarcomas (23% vs. 9%), clear cell carcinomas (3 vs. 2%) and serous carcinomas (12% vs. 5%) [11]. Similar rates were reported in the Multiethnic Cohort Study (1993-1996), with 91.4% of Caucasians presenting with more favorable histology, compared to 69.1% of African Americans [7].

Table 2.

Endometrial cancer by histopathological category among African Americans and Caucasians

| Study/Database/Histopathological Category | N (total) | African American | % | Caucasian | % | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sherman et al. | SEER (1992-1998) | 18,356 | 1,844 | 16,512 | <0.001 | ||

| Less aggressive1 | 1,100 | 60 | 13,989 | 85 | |||

| More aggressive2 | 627 | 34 | 2,039 | 12 | |||

| Setiawan et al. | Multiethnic Cohort Study (1993-1996) | 321 | 55 | 104 | <0.001 | ||

| Less aggressive1 | 38 | 69 | 95 | 91 | |||

| More aggressive3 | 17 | 31 | 9 | 9 | |||

| Hicks et al. | National Cancer Database (1988-1994) | 55,533 | 3,226 | 52,307 | <0.001 | ||

| Less aggressive4 | 2,254 | 70 | 42,816 | 82 | |||

| More aggressive5 | 355 | 11 | 1,569 | 3 | |||

| Wright et al. | SEER (1998-2004) | 80,915 | 5,564 | 69,956 | <0.001 | ||

| Less (aggressive1 | 3,450 | 62 | 59,519 | 85 | |||

| More aggressive2 | 2,114 | 38 | 10,437 | 15 | |||

| Smotkin et al. | Single institution review (1999-2009) | 984 | 308 | 382 | <0.001 | ||

| Less aggressive1 | 113 | 37 | 284 | 74 | |||

| More aggressive2 | 195 | 63 | 98 | 26 | |||

| Oliver et al. | Department of Defense Tumor Registry (1990-2003) | 2,198 | 176 | 2020 | <0.01 | ||

| Less aggressive6 | 92 | 52 | 1545 | 76 | |||

| More aggressive7 | 84 | 48 | 475 | 24 | |||

| TOTAL | 160,505 | 11,173 | 141,281 | <0.001 | |||

| Less aggressive | 7,047 | 63 | 118,248 | 84 | |||

| More aggressive | 4,126 | 37 | 23,033 | 16 | |||

Includes usual types of endometrial adenocarcinoma and endometrioid adenocarcinoma.

Includes serous/clear cell carcinoma, carcinosarcoma, and pure sarcoma.

Includes squamous carcinoma, clear cell adenocarcinoma, serous adenocarcinoma, undifferentiated carcinoma, transitional cell carcinoma, and mullerian/mesodermal missed tumors.

Includes adenocarcinoma (not otherwise specified) and endometrioid carcinoma.

Includes squamous cell carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, and papillary serous cystadenocarcinoma.

Includes endometrioid adenocarcinoma.

Includes non-endometrioid adenocarcinoma.

Table 3.

Endometrial cancer by stage among African Americans and Caucasians

| Study | Database/Stage | N (total) | African American | % | Caucasian | % | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sherman et al | SEER (1992-1998) | 15,089 | 1,100 | 13,989 | |||

| Localized1 | 691 | 63 | 10,859 | 78 | <0.001 | ||

| Regional2 | 194 | 18 | 1,903 | 14 | 0.165 | ||

| Distant3 | 116 | 10 | 713 | 5 | 0.089 | ||

| Unstaged | 99 | 9 | 514 | 4 | 0.095 | ||

| Setiawan et al | Multiethnic Cohort Study (1993-1996) | 159 | 55 | 104 | |||

| Localized1 | 33 | 60 | 86 | 83 | 0.039 | ||

| Advanced4 | 21 | 38 | 15 | 16 | 0.134 | ||

| Unstaged | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | >0.100 | ||

| Hicks et al | National Cancer Database (1988-1994) | 54,067 | 3,142 | 50,925 | |||

| Localized1 | 1,601 | 51 | 34,357 | 67 | <0.001 | ||

| Regional2 | 711 | 23 | 8,063 | 16 | <0.001 | ||

| Distant3 | 382 | 12 | 2,294 | 5 | <0.001 | ||

| Unstaged | 448 | 14 | 6,211 | 12 | 0.238 | ||

| Wright et al | SEER (1988-2004) | 75,514 | 5,564 | 69,956 | |||

| Localized1 | 3,018 | 54 | 50,720 | 73 | <0.001 | ||

| Regional2 | 1,284 | 23 | 11,229 | 16 | <0.001 | ||

| Distant3 | 766 | 14 | 4,711 | 7 | <0.001 | ||

| Unstaged | 496 | 9 | 3,296 | 5 | 0.0029 | ||

| Oliver et al | Dept of Defense Tumor Registry (1990-2003) | 2,198 | 176 | 2,022 | 0.02 | ||

| Localized1 | 120 | 68 | 1,528 | 76 | 0.073 | ||

| Regional2 | 24 | 14 | 256 | 13 | 0.897 | ||

| Distant3 | 20 | 11 | 113 | 6 | 0.509 | ||

| Unstaged | 12 | 7 | 125 | 6 | 0.901 | ||

| Smotkin et al | Single Institution Review (1999-2009) | 690 | 308 | 382 | |||

| Localized1 | 169 | 55 | 288 | 75 | <0.001 | ||

| Regional2 | 83 | 27 | 61 | 16 | 0.107 | ||

| Distant3 | 48 | 16 | 26 | 7 | 0.223 | ||

| Unstaged | 8 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 0.912 | ||

| Total | 147,717 | 10,345 | 137,378 | ||||

| Localized | 5,632 | 54 | 97,838 | 71 | <0.001 | ||

| Regional | 2,296 | 22 | 21,512 | 16 | <0.001 | ||

| Distant | 1,332 | 13 | 7,857 | 6 | <0.001 | ||

| Unstaged | 1,064 | 10 | 10,156 | 7 | <0.001 | ||

Includes stage I disease.

Includes stage II and III disease.

Includes stage IV disease.

Includes stage II, III, and IV disease.

More aggressive histopathologic features may account for more advanced stage at presentation seen in African American women. The American Cancer Society reports that only 54% of African Americans present with more favorable, localized uterine cancer as opposed to 71% of white patients. While 39% of African American patients have regional or distant metastases at the time of presentation, only 26% of whites do [8]. In the Wright study, 73% of Caucasian women presented with stage I disease, while only 54% of African American patients did. In contrast, 14% of Caucasian patients presented with stage III or IV disease, while 27% of African Americans presented in these later stages [11].

African American patients are known to have poorer prognoses even when controlling for stage of disease. The Multiethnic Cohort Study noted that African Americans had higher grade and more aggressive tumors even when comparing patients with the same stage at diagnosis [7]. Similarly, a 1998 National Cancer Database analysis of 3,226 African American women and 52,307 white women from 1,491 hospitals showed that African American women were significantly less likely to have well-differentiated tumors when compared to whites (39% vs. 24%) [9]. While these authors argued that this difference in tumor grade pointed towards a biologic basis for the racial disparities in uterine cancer survival, African Americans remained less likely to survive their cancers when compared to whites, even when analyzing patients with similar grades and histologic subtypes.

The importance of histologic differences has been highlighted in studies of patients in equal access environments. Smotkin et al., in a single-institution study comparing patients of similar socioeconomic backgrounds, found that after stratifying based on histopathology, survival rates equalized between African American and Caucasian women [12]. Other single-institution retrospective studies with comparable patient populations have confirmed similar survival between African American and Caucasian women with uterine serous carcinoma [14, 15]. However, because African American patients in the U.S. are more likely than Caucasians to live in poverty, single-institution studies comparing patients of similar socioeconomic backgrounds do not diminish the role of economic disparities as the source of survival differences.

Little research has been done to determine why these histologic differences exist. While molecular analyses may reveal genetic predispositions in different ethnic groups that make them more likely to acquire non-endometrioid subtypes, more study should focus on risk factors and treatments for non-endometrioid subtypes of uterine cancer. This information could help to develop different screening mechanisms or treatment algorithms that may narrow the survival gap between Caucasian and African American patients.

Molecular and Genetic Factors

African American women present with more aggressive subtypes of endometrial cancer and at more advanced stage compared to Caucasians. The increased incidence of serous and clear cell tumors and sarcomas accounts, at least in part, for more disseminated disease at presentation. Endometrioid endometrial cancer has a distinct genetic profile when compared to type II endometrial cancers. Racial differences in molecular and genetic factors may explain the histologic and survival discrepancy.

Microsatellite instability (MSI) and mutations in the tumor suppressor gene PTEN are more common in type I endometrial cancer, which portends more favorable prognosis [16-18]. In single-institution studies, PTEN mutations are less common in African American compared to Caucasian women; however, the evidence on MSI is conflicting [19]. In a study of 140 cases of endometrial adenocarcinoma, PTEN mutations were seen in 17 of 78 (22%) Caucasian patients compared to 3 out of 62 (5%) African American patients [19]. In this same sample, 9 of 55 (16%) Caucasian women had MSI compared to 6 of 45 (13%) of African American women. Another study of 229 endometrial carcinoma cases from a single institution showed that MSI-positive tumors were more common in Caucasian women compared with African American women (adjusted OR=3.18, 95% CI 1.16-8.67). Overall survival and recurrence between women with MSI-positive and MSI-negative tumors was not significantly different in this study [20].

In contrast, mutations in tumor suppressor gene p53 are more common in type II endometrial cancer and are associated with poorer prognosis. Three recent studies have found p53 expression to be more common in the tumors of African American patients [21-23]. These studies did not stratify for type I vs. type II endometrial cancer, and the differences in p53 expression could simply be due to the fact that African Americans are more likely to have type II tumors. While p53 expression may not explain the differences in survival between African Americans and Caucasians with similar tumor subtypes, several recent studies have attempted to uncover other differences in gene expression between races.

The HER2/neu oncogene has been associated with treatment resistance and poor survival in breast, ovarian, and endometrial cancers and may be more frequently up-regulated in the tumors of African Americans. A 2005 study of 27 women (10 African Americans/17 Caucasians) with uterine papillary serous carcinoma (UPSC) found heavy HER2/neu receptor expression in 70% of the African American women but only 24% of the white women [24]. When adjusted for race and age, heavy HER2/neu expression was associated with earlier death (adjusted HR 28.00, p-value=0.02) and presumably more aggressive disease. A summary of these studies is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Molecular studies of endometrial cancer in African Americans and Caucasians

| Study | Genetic Factor | N (total) | African American | % | Caucasian | % | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maxwell et al. | PTEN | 140 | 17/78 | 22 | 3/62 | 5 | 0.006 |

| MSI | 140 | 8/85 | 9 | 5/15 | 33 | 0.02 | |

| Basil et al. | MSI | 229 | 5/39 | 13 | 65/189 | 34 | 0.012 |

| Kohler et al. | p53 | 179 | 27/47 | 57 | 34/129 | 36 | 0.001 |

| Clifford et al. | p53 | 164 | 15/44 | 34 | 13/117 | 11 | 0.003 |

| Santin et al. | HER2/neu | 27 | 7/10 | 70 | 4/17 | 24 | 0.04 |

Differential expression of other genes has also been described. A recent study explored the candidate phospho-serine phosphatase-like gene (PSPHL) as a cause of genetic variation seen in endometrial cancer between African American and Caucasian women [25]. The study found higher PSPHL expression in stage and grade-matched cancers of African Americans. However, PSPHL expression was also more common in normal tissues from African Americans, and its expression was not associated with survival. This may mean that the PSPHL gene is simply found more often in African Americans and does not confer any differences in tissue phenotype. In short, the relationship between PSHPHL and endometrial cancer has not been established.

Other studies have shown no difference in the gene expression profiles of endometrial cancers from African American women. A 2006 study from Memorial-Sloan-Kettering concluded that molecular factors did not play a role in endometrial cancer's survival disparity, as they found no statistically significant differences in gene expression between groups of Caucasian and African American women [26]. Though sixteen genes were differentially expressed in African American patients, none of them reached statistical significance. The authors also failed to detect a difference in survival between African Americans and Caucasians. However, this small cohort of only 39 patients may not be representative of the population as a whole.

The racial disparity in endometrial cancer survival may be explained by genetic differences in the patients themselves, rather than by differences in their tumors. Differences in estrogen metabolism have been explored as a source of the disparity. This theory was best illustrated in a 2008 analysis by Maxwell et al., which examined racial disparities in endometrial cancer recurrence among women with early-stage disease [27]. This study found that African American women using estrogen replacement therapy (ERT) after surgical treatment for type I endometrial cancer had lower recurrence-free survival when compared to African Americans who did not use ERT after treatment (8.9% vs. 1.5%). This estrogen-related difference in risk was not observed among white patients, suggesting a racial difference in estrogen metabolism or estrogen effect. Since endometrial cancer is an estrogen-responsive condition, this has important implications for treatment of African American patients.

Molecular biology and genetic alterations in uterine cancer are new areas of study that may explain the increased prevalence of more aggressive endometrial cancer subtypes in African American women. Differential Her2/neu expression is a promising area of research, which may have important implications for targeted chemotherapeutic treatment of African Americans with uterine papillary serous cancer. Other studies have demonstrated alterations affecting the ERBB2 oncogene, which have been associated with poor outcomes and are more common in endometrial cancers from African American compared to Caucasian women [24]. Current genome wide association studies may also reveal more specific associations between certain histologic subtypes and gene alleles [28-30].

Socioeconomic Factors

Biologic factors do not solely explain the survival disparity seen in endometrial cancer, as African American death rates remain higher at every stage, type, and grade of disease [2]. African Americans are more likely than Caucasians to live in poverty and reside in underserved areas. They are less likely to receive higher education or possess private health insurance and are less likely to have regular primary healthcare. These factors could explain the higher stage at diagnosis in African American patients. Lower socioeconomic status and lack of healthcare funding could also explain a delay in definitive treatment, as time may be wasted while patients without private insurance await enrollment into government programs or referral to a gynecologic oncologist.

Due to these factors, socioeconomic disparities likely account for much of the remaining survival difference seen in endometrial cancer, though the effect is more difficult to quantify. All socioeconomic studies were retrospective, and most included a relatively small number of cases. Fedewa et al. studied the effect of insurance status on uterine cancer outcomes, examining 39,510 cases of uterine cancer over a two-year period [31]. In multivariate models adjusting for age and hospital characteristics, the authors found a statistically significant survival difference in African Americans compared to whites (HR=2.35, 95% CI 2.20-2.51). After adjusting for education, age, facility characteristics, grade, and histology, patients without insurance or with publicly-funded insurance had higher mortality risk, stage for stage, than those with private insurance: HR 1.6 (95% CI 1.21-2.13), 1.13 (95% CI 0.66-1.93), 1.31 (95% CI 0.99-1.73) for stage I, II, III uninsured women, respectively; and HR 1.95 (95% CI 1.54-2.48), 1.52 (95% CI 1.0-2.31), and 1.36 (95% CI 1.05-1.77) for stage I, II, III women on Medicaid. African Americans in the study were less likely to have privately-funded insurance. However, after adjusting for zip code, education level, clinical factors, and insurance status, the hazard ratio of death for African Americans dropped from 2.35 (95% CI 2.20-2.51) to 1.28 (95% CI 1.17-1.40). This suggests that healthcare access and socioeconomic status account for some, but not all, of the disparities observed in this population.

A 2004 study by Madison et al. also illustrates the effects of socioeconomic status on stage at diagnosis of uterine cancer [32]. This study of the Detroit-area SEER database from 1990-1998 found that African American women were more likely than white women to present with advanced-stage disease (adjusted OR=1.41, 95% CI 1.09-1.81). While aggressive histology (OR=2.62, 95% CI 1.93-3.55) and higher grade (OR=4.31, 95% CI 3.52-5.20) were associated with the highest risk for advanced-stage disease, higher family median income (OR=0.83, 95% CI 0.83-0.99) was associated with a decreased risk for advanced stage at presentation. When this overall increase in risk was adjusted for age, tumor grade, and histology, African American women remained 41% more likely to have advanced-stage disease at the time of presentation. Lower income may contribute to later stage at diagnosis, as controlling for biologic factors did not completely close this gap. After further analysis, this study found that the effect of socioeconomic status remained important only in women with the less aggressive endometrial histology. In women with aggressive endometrial tumors, race, age, and median family income were not associated with stage at diagnosis. This suggests that, while some cancers are too aggressive to catch in their early stages, there is a large group of patients with less aggressive tumors that could benefit from improved access to care and earlier diagnosis.

In attempt to control for differences in access to care, Oliver et al. evaluated racial disparities among 2,582 beneficiaries in the Department of Defense Military Health System [13]. The study did not analyze survival data but focused on the effect of an equal access environment on histologic subtype, grade, and stage at presentation. While African American women were more likely than Caucasian women to present with non-endometrioid histology (47.7% vs. 23.5%), this trend was confined to women over 50. Similarly, older African American women were more likely to present with poorly differentiated tumors (21.4% vs. 15.9%) and/or distant metastases (13.6% vs. 5.8%) when compared with age-matched white women. These associations were not observed in women under 50 years of age. Such results suggest that racial disparities in endometrial cancer are limited to postmenopausal women when access to care is equal. Because age limits restrict younger women from most government-funded insurance plans, healthcare access may play a larger role in this population and contribute disproportionately to the advanced disease presentation observed in this group. The presumed later presentation of disease among older African American women may reflect other social and cultural phenomena, including differential health education, familiarity and trust of the healthcare system.

Not all studies have shown an effect of socioeconomic factors on the survival disparity. However, the studies refuting this effect were relatively small studies from single institutions. While both study populations were ethnically diverse, their economic diversity is suspect and was not reported in either paper. Since people living in the same neighborhoods are likely to be in similar income brackets, neither of these study populations are representative of our nation as a whole, where economic standing varies markedly by race [12, 33].

In aggregate, the literature suggests that, while improved access to care would narrow the survival gap significantly, disparities in access to care cannot exclusively account for the racial inequities in endometrial cancer. For now, this is still an important area on which to focus, as changes in healthcare policy could significantly affect outcomes in many different cancer types.

Comorbid Factors

African Americans have higher rates of obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease and have worse health outcomes compared to other races in the United States. Some have argued that these comorbidities could explain the disparities found in this population, especially as these conditions also serve as risk factors for endometrial cancer.

In the Multiethnic Cohort Study of 46,933 women, Setiawan et al. found that endometrial cancer was positively associated with later age at menopause, unopposed estrogen use, and obesity and negatively associated with increasing parity and duration of oral contraceptive use. Compared to Caucasians, African Americans had lower incidence of endometrial cancer (incidence rate ratio (IRR) = 0.76, 95% CI 0.53-1.08) [7]. After adjusting for risk factors, African American women had a higher rate of advanced stage disease (IRR=1.57, 95% CI 0.75-3.29) and more aggressive histology (IRR=2.63, 95% CI 1.05-6.59), suggesting that risk factors in African American women do not account for the racial/ethnic disparities in aggressive histology or advanced stage disease [7].

The Setiawan study found little decrease in aggressive histologies after accounting for risk factors (RR 2.96 decreased to RR 2.63). A previous study by Weiss et al. found similar risk factors present in both non-aggressive and aggressive subtypes of endometrial cancer [34]. The Multiethnic Cohort study concluded that the incidence of risk factors in different ethnic groups did not account for the racial/ethnic disparities in the prevalence of early or advanced stage endometrial cancer [7]. Importantly, diabetes, which is more common in African American women, was not associated with the highly aggressive subtypes that disproportionately affect this population.

Though comorbid factors may not explain the discrepancy in incidence of endometrial cancer among different groups, several studies have examined the influence of comorbid conditions on survival with mixed results. Madison et al. showed that African American women had increased overall adjusted mortality compared to Caucasian women after controlling for advanced age, aggressive histology, treatment, and income, especially for younger African American women [32]. However, racial differences in survival were not observed in endometrial cancer specific mortality (14.2 months for African Americans vs. 14.7 months for Caucasians), while they were observed for death from non-cancer causes (16.7 months for African Americans vs. 32.3 months for Caucasians). In another SEER database study, Olsen et al. analyzed a cohort of 11,610 Caucasian and 958 African American women diagnosed with endometrial cancer between 2000 and 2005. They found that African American women had worse survival than Caucasian women for overall (HR1.19, 95% CI 1.06-1.35) and disease-specific survival (HR1.27, 95% CI 1.08-1.49) after adjusting for clinical and sociodemographic characteristics. While African Americans were more likely to have diabetes and/or hypertension, diabetes was only associated with poorer outcomes in Caucasian women. This study confirmed that, while comorbid conditions do affect overall survival, they do not explain differences in disease-specific survival [35].

Comorbid conditions could also contribute to disease-related mortality by preventing women from receiving curative surgical treatment. As discussed below, previous studies have found that African American women are less likely to undergo definitive surgery at every stage of endometrial cancer. However, it is difficult to determine whether comorbid conditions are at the root of the discrepancy due to limitations of popular databases, which do not always collect data on comorbid conditions or surgical risks. Current research does not support that comorbidity increases disease specific mortality from endometrial cancer.

Overall, comorbid factors contribute minimally to the disparity in endometrial cancer incidence. Few studies have examined risk factors for highly aggressive uterine cancers, but none have found novel risk factors that explain the higher proportion of African American women diagnosed with highly aggressive uterine cancers [34]. If there are risk factors that predispose African Americans to more aggressive subtypes, these factors have yet to be elucidated. The alternative theory that comorbid factors might influence surgical treatment or surgery-related mortality associated with uterine cancers in African Americans has not borne out in the literature. Recent studies have found no difference in surgical management between African American and Caucasian patients and have also failed to show any differences in peri-operative mortality between races. Though we believe that factors such as obesity and heart disease may play a role in the lower rates of minimally invasive techniques for African American patients, the surgical mortality rates surrounding these procedures are not statistically different. It is more plausible that comorbid factors contribute to the survival gap by increasing all-cause mortality in African American women while having little to no effect on disease-specific mortality.

Treatment Factors

Treatment factors have been suggested as a reason for the mortality disparity among African American women with endometrial cancer. Recent studies have examined the rates of definitive surgery and appropriate treatment for various ethnic groups. In an analysis of data from the National Cancer Database from 1988-1994, Hicks et al. found that African American women were less likely to undergo definitive surgery at every stage of disease. Even for stage I disease, 7.7% of African American women did not receive the standard of care compared to 2.2% of whites [9]. Madison et al. analyzed data from 1990-1998 and found that 95.6% of white women received hysterectomy while only 89.1% of African American women did. The reasons for this discrepancy were not analyzed thoroughly in these reports, but other studies have found similar discrepancies in surgical intervention in ovarian and cervical cancer, as well [32].

Encouragingly, the treatment inequities between the two groups appear to be improving. An analysis of 1998 SEER data by Trimble et al. examined treatment of 711 incident endometrial cancer cases in women with no prior history of cancer [36]. They found no race-based differences in recommended therapy for women with stage-matched uterine adenocarcinoma. Wright's analysis of SEER data from 1999 to 2004 found similar rates of comprehensive surgical staging with lymphadenectomy in both whites and African Americans (48% vs. 45%) [11]. Most recently, in a 2011 study of 5470 women from a statewide population database, Fleury et al. found that African American patients were actually more likely to have their surgeries performed by high volume surgeons (adjusted OR=1.27, 95% CI: 1.09–1.49) and were no less likely than white patients to undergo lymphadenectomy (OR=1.13, 95% CI: 0.98–1.30) [15].

For patients who undergo chemotherapy or radiation, differences in response rates could affect overall survival. A 2010 study reviewed data from four GOG randomized treatment trials for FIGO stage III, IV, or recurrent endometrial cancers. All patients received doxorubicin and cisplatin and had good performance status (0 to 2) [37]. African American patients had only a 35% response rate, while 43% of Caucasians responded to treatment. The relative dose, relative time, and relative dose intensities were the same between the two groups. Forty-five percent of white patients compared to 40% of African American patients completed at least seven cycles. Most patients who stopped chemotherapy did so because of on-treatment disease progression. A significant portion of both African American and white patients (29% vs. 23%) discontinued therapy because of toxicities, but there was no difference in the incidence of grade 3-4 toxicities between the two groups. Overall, African American and white patients received identical treatment and completed therapy at similar rates; however, African American patients had an increased risk of death when compared to whites (HR = 1.26, 95% CI 1.06-1.51). This may be further evidence that molecular or genetic factors are the source of racial disparities in survival.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The survival disparity in African American women with endometrial cancer is multifactorial, and its complexity highlights the need for continued research in this area. Despite having a lower incidence of endometrial cancer, African American women have almost twice the disease-specific mortality rate [34]. Our analysis suggests that histopathologic factors play the largest role in the disparity, with African Americans experiencing higher rates of aggressive histologic subtypes, poorly differentiated tumors, and distant metastases when compared to Caucasians. However, African American women experience poorer prognosis at every stage and grade as well as with every histologic type. This highlights the potential influence of socioeconomic, cultural, and treatment factors on the survival disparity. The Affordable Care Act will address healthcare insurance for many without coverage, of which a disproportionate number are African American and minority. Increasing awareness and education among women regarding the signs and symptoms of uterine cancer and the appropriate referral from primary care providers to oncologists remain vital components in reducing the gap in survival. The effect of racial predispositions toward genetic traits and variants in oncogenic pathways also cannot be overlooked. By clarifying the potential molecular differences in carcinogenesis, more appropriate treatments may be developed to decrease mortality rates. National and governmental organizations have focused on eliminating racial inequities in health outcomes by expanding insurance coverage, recruiting providers to practice in underserved communities, and encouraging research in healthcare disparities. Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic cancer among American women, and equalizing diagnostic and prognostic differences among minority women will continue to be a priority.

Highlights.

▶ Compared to Caucasian women, African American women have lower incidence of uterine cancer but almost twice the mortality rates.

▶ Treatment outcome disparities are not explained fully by differences in comorbidities and access to care.

▶ Further research is necessary to eliminate racial disparities in uterine cancer.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest or financial relationships to disclose.

References

- 1.Farley J, Risinger JI, Rose GS, Maxwell GL. Racial disparities in blacks with gynecologic cancers. Cancer. 2007;110:234–43. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexander DD, Waterbor J, Hughes T, Funkhouser E, Grizzle W, Manne U. African-American and Caucasian disparities in colorectal cancer mortality and survival by data source: an epidemiologic review. Cancer Biomark. 2007;3:301–13. doi: 10.3233/cbm-2007-3604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerend MA, Pai M. Social determinants of Black-White disparities in breast cancer mortality: a review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:2913–23. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [2013 February 22];Uterine Cancer Rates by Race and Ethnicity. 2013 Jan 13; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/uterine/statistics/race.htm.

- 6.Sherman ME, Devesa SS. Analysis of racial differences in incidence, survival, and mortality for malignant tumors of the uterine corpus. Cancer. 2003;98:176–86. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Setiawan VW, Pike MC, Kolonel LN, Nomura AM, Goodman MT, Henderson BE. Racial/ethnic differences in endometrial cancer risk: the multiethnic cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:262–70. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Murray T, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hicks ML, Phillips JL, Parham G, Andrews N, Jones WB, Shingleton HM, Menck HR. The National Cancer Data Base report on endometrial carcinoma in African-American women. Cancer. 1998;83:2629–37. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19981215)83:12<2629::AID-CNCR30>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duong LM, Wilson RJ, Ajani UA, Singh SD, Eheman CR. Trends in endometrial cancer incidence rates in the United States, 1999-2006. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2011;20:1157–63. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright JD, Fiorelli J, Schiff PB, Burke WM, Kansler AL, Cohen CJ, Herzog TJ. Racial disparities for uterine corpus tumors: changes in clinical characteristics and treatment over time. Cancer. 2009;115:1276–85. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smotkin D, Nevadunsky NS, Harris K, Einstein MH, Yu Y, Goldberg GL. Histopathologic differences account for racial disparity in uterine cancer survival. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127:616–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oliver KE, Enewold LR, Zhu K, Conrads TP, Rose GS, Maxwell GL, Farley JH. Racial disparities in histopathologic characteristics of uterine cancer are present in older, not younger blacks in an equal-access environment. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;123:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Wahab Z, Ali-Fehmi R, Cote ML, Elshaikh MA, Ibrahim DR, Semaan A, Schultz D, Morris RT, Munkarah AR. The impact of race on survival in uterine serous carcinoma: a hospital-based study. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121:577–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleury AC, Ibeanu OA, Bristow RE. Racial disparities in surgical care for uterine cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121:571–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Risinger JI, Hayes K, Maxwell GL, Carney ME, Dodge RK, Barrett JC, Berchuck A. PTEN mutation in endometrial cancers is associated with favorable clinical and pathologic characteristics. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:3005–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maxwell GL, Risinger JI, Alvarez AA, Barrett JC, Berchuck A. Favorable survival associated with microsatellite instability in endometrioid endometrial cancers. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:417–22. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)01165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maxwell GL, Risinger JI, Gumbs C, Shaw H, Bentley RC, Barrett JC, Berchuck A, Futreal PA. Mutation of the PTEN tumor suppressor gene in endometrial hyperplasias. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2500–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maxwell GL, Risinger JI, Hayes KA, Alvarez AA, Dodge RK, Barrett JC, Berchuck A. Racial disparity in the frequency of PTEN mutations, but not microsatellite instability, in advanced endometrial cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2999–3005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Basil JB, Goodfellow PJ, Rader JS, Mutch DG, Herzog TJ. Clinical significance of microsatellite instability in endometrial carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;89:1758–64. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001015)89:8<1758::aid-cncr16>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kohler MF, Carney P, Dodge R, Soper JT, Clarke-Pearson DL, Marks JR, Berchuck A. p53 overexpression in advanced-stage endometrial adenocarcinoma. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1246–52. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clifford SL, Kaminetsky CP, Cirisano FD, Dodge R, Soper JT, Clarke-Pearson DL, Berchuck A. Racial disparity in overexpression of the p53 tumor suppressor gene in stage I endometrial cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:S229–32. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70380-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alkushi A, Lim P, Coldman A, Huntsman D, Miller D, Gilks CB. Interpretation of p53 immunoreactivity in endometrial carcinoma: establishing a clinically relevant cut-off level. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2004;23:129–37. doi: 10.1097/00004347-200404000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santin AD, Bellone S, Siegel ER, Palmieri M, Thomas M, Cannon MJ, Kay HH, Roman JJ, Burnett A, Pecorelli S. Racial differences in the overexpression of epidermal growth factor type II receptor (HER2/neu): a major prognostic indicator in uterine serous papillary cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:813–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.10.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allard JE, Chandramouli GV, Stagliano K, Hood BL, Litzi T, Shoji Y, Boyd J, Berchuck A, Conrads TP, Maxwell GL, Risinger JI. Analysis of PSPHL as a Candidate Gene Influencing the Racial Disparity in Endometrial Cancer. Front Oncol. 2012;2:65. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferguson SE, Olshen AB, Levine DA, Viale A, Barakat RR, Boyd J. Molecular profiling of endometrial cancers from African-American and Caucasian women. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101:209–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maxwell GL, Tian C, Risinger JI, Hamilton CA, Barakat RR, Study GOG. Racial disparities in recurrence among patients with early-stage endometrial cancer: is recurrence increased in black patients who receive estrogen replacement therapy? Cancer. 2008;113:1431–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buys TP, Cantor SB, Guillaud M, Adler-Storthz K, Cox DD, Okolo C, Arulogon O, Oladepo O, Basen-Engquist K, Shinn E, Yamal JM, Beck JR, Scheurer ME, van Niekerk D, Malpica A, Matisic J, Staerkel G, Atkinson EN, Bidaut L, Lane P, Benedet JL, Miller D, Ehlen T, Price R, Adelwole IF, Macaulay C, Follen M. Optical Technologies and Molecular Imaging for Cervical Neoplasia: A Program Project Update. Gend Med. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spurdle AB, Thompson DJ, Ahmed S, Ferguson K, Healey CS, O'Mara T, Walker LC, Montgomery SB, Dermitzakis ET, Fahey P, Montgomery GW, Webb PM, Fasching PA, Beckmann MW, Ekici AB, Hein A, Lambrechts D, Coenegrachts L, Vergote I, Amant F, Salvesen HB, Trovik J, Njolstad TS, Helland H, Scott RJ, Ashton K, Proietto T, Otton G, Tomlinson I, Gorman M, Howarth K, Hodgson S, Garcia-Closas M, Wentzensen N, Yang H, Chanock S, Hall P, Czene K, Liu J, Li J, Shu XO, Zheng W, Long J, Xiang YB, Shah M, Morrison J, Michailidou K, Pharoah PD, Dunning AM, Easton DF, Group ANECS. Group NSoECG Genome-wide association study identifies a common variant associated with risk of endometrial cancer. Nat Genet. 2011;43:451–4. doi: 10.1038/ng.812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Long J, Zheng W, Xiang YB, Lose F, Thompson D, Tomlinson I, Yu H, Wentzensen N, Lambrechts D, Dörk T, Dubrowinskaja N, Goodman MT, Salvesen HB, Fasching PA, Scott RJ, Delahanty R, Zheng Y, O'Mara T, Healey CS, Hodgson S, Risch H, Yang HP, Amant F, Turmanov N, Schwake A, Lurie G, Trovik J, Beckmann MW, Ashton K, Ji BT, Bao PP, Howarth K, Lu L, Lissowska J, Coenegrachts L, Kaidarova D, Dürst M, Thompson PJ, Krakstad C, Ekici AB, Otton G, Shi J, Zhang B, Gorman M, Brinton L, Coosemans A, Matsuno RK, Halle MK, Hein A, Proietto A, Cai H, Lu W, Dunning A, Easton D, Gao YT, Cai Q, Spurdle AB, Shu XO. Genome-wide association study identifies a possible susceptibility locus for endometrial cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:980–7. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fedewa SA, Lerro C, Chase D, Ward EM. Insurance status and racial differences in uterine cancer survival: a study of patients in the National Cancer Database. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;122:63–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Madison T, Schottenfeld D, James SA, Schwartz AG, Gruber SB. Endometrial cancer: socioeconomic status and racial/ethnic differences in stage at diagnosis, treatment, and survival. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:2104–11. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matthews RP, Hutchinson-Colas J, Maiman M, Fruchter RG, Gates EJ, Gibbon D, Remy JC, Sedlis A. Papillary serous and clear cell type lead to poor prognosis of endometrial carcinoma in black women. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;65:206–12. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1997.4617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiss JM, Saltzman BS, Doherty JA, Voigt LF, Chen C, Beresford SA, Hill DA, Weiss NS. Risk factors for the incidence of endometrial cancer according to the aggressiveness of disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:56–62. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olson SH, Atoria CL, Cote ML, Cook LS, Rastogi R, Soslow RA, Brown CL, Elkin EB. The impact of race and comorbidity on survival in endometrial cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:753–60. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trimble EL, Harlan LC, Clegg LX, Stevens JL. Pre-operative imaging, surgery and adjuvant therapy for women diagnosed with cancer of the corpus uteri in community practice in the United States. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;96:741–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farley JH, Tian C, Rose GS, Brown CL, Birrer M, Risinger JI, Thigpen JT, Fleming GF, Gallion HH, Maxwell GL. Chemotherapy intensity and toxicity among black and white women with advanced and recurrent endometrial cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Cancer. 2010;116:355–61. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]