Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To examine recent national trends in psychotropic use for very young children at US outpatient medical visits.

METHODS:

Data for 2- to 5-year-old children (N = 43 598) from the 1994–2009 National Ambulatory and National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys were used to estimate the weighted percentage of visits with psychotropic prescriptions. Multivariable logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with psychotropic use. Time effects were examined in 4-year blocks (1994–1997, 1998–2001, 2002–2005, and 2006–2009).

RESULTS:

Psychotropic prescription rates were 0.98% from 1994–1997, 0.83% from 1998–2001, 1.45% from 2002–2005, and 1.00% from 2006–2009. The likelihood of preschool psychotropic use was highest in 2002–2005 (1994–1997 adjusted odds ratio [AOR] versus 2002–2005: 0.67; 1998–2001 AOR versus 2002–2005: 0.63; 2006–2009 AOR versus 2002–2005: 0.64), then diminished such that the 2006–2009 probability of use did not differ from 1994–1997 or from 1998–2001. Boys (AOR versus girls: 1.64), white children (AOR versus other race: 1.42), older children (AOR for 4 to 5 vs 2 to 3 year olds: 3.87), and those lacking private insurance (AOR versus privately insured: 2.38) were more likely than children from other groups to receive psychotropic prescriptions.

CONCLUSIONS:

Psychotropic prescription was notable for peak usage in 2002–2005 and sociodemographic disparities in use. Further study is needed to discern why psychotropic use in very young children stabilized in 2006–2009, as well as reasons for increased use in boys, white children, and those lacking private health insurance.

Keywords: psychotropic medications, stimulant medications, psychostimulants, very young children, preschoolers, behavioral disorders, mental health disorders, psychiatric disorders

What’s Known on This Subject:

Studies of psychotropic use in very young US children in the last decade have been limited by the regions, insurance types, or medication classes examined. There is a paucity of recent, nationally representative investigations of US preschool psychotropic use.

What This Study Adds:

In a national sample of 2 to 5 year olds, the likelihood of psychotropic prescription peaked in the mid-2000s, then stabilized in the late 2000s. Increased psychotropic use in boys, white children, and those lacking private health insurance was documented.

There is increasing recognition that significant mental health problems may occur in very young children.1,2 Epidemiologic studies have documented two- to threefold increases in psychotropic prescriptions for US preschool children during 1991–2001,3,4 even though few psychotropic medications are approved for this age group by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).5,6 However, there is a paucity of nationally representative studies investigating more recent trends in preschool psychotropic medication usage.7 The impact of more recent commercial developments (including new product releases)8 and scientific advisories (such as FDA “black box warnings” and public health advisories regarding psychotropic medications)9–11 is not well characterized for this age group.

Most previous studies of preschool psychotropic use have been demographically limited, focusing on Medicaid samples, region-specific managed-care health maintenance organization (HMO) populations, or privately insured children,3,4,12,13 whereas others have concentrated on a single medication class (eg, stimulants14,15 or atypical antipyschotics16). There is a need to understand better the sociodemographic trends in psychotropic use among very young children. For example, 2 studies have noted higher rates of psychotropic medication use during the 1990s in preschoolers enrolled in Medicaid compared with non-Medicaid groups, whereas 1 study did not.3,12,17 Other sociodemographic predictors may include gender and race/ethnicity. Previous studies in the late 1990s and early 2000s have revealed increased psychotropic prescription rates in preschool boys compared with girls,4,12 and in very young white compared with black children,4,17 but these samples were demographic group specific (Medicaid-only or region-specific HMO populations). The extent of differences in psychotropic prescription based on health insurance type, gender, and race have not been determined in updated, more sociodemographically diverse samples of very young children.

The current study examined trends in and sociodemographic predictors of psychotropic medication use among 2- to 5-year-old children in a US nationally representative sample of visits to office-based practices and hospital-based outpatient clinics over a 16-year period (1994–2009). We further examined trends in mental health diagnoses to determine which diagnoses were associated with the highest medication rates, and the relationship between changing rates of behavioral diagnoses and the likelihood of psychotropic medication receipt over time.

Methods

Data Source and Design

We used data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) and the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS), which collect data on patient visits to community, non–federally funded, office-based physician practices and hospital-based outpatient clinics throughout the United States.18 We did not include hospital-based emergency department data to maintain a focus on medication prescriptions at nonemergent visits. Thus, we analyzed data from office-based physician practice and hospital-based outpatient clinic visits (N = 43 598) between 1994 and 2009 for 2- to 5-year-old children.

The surveys use a multistate probability design as described previously.19 The NAMCS has a 3-stage sampling design, with sampling based on geographic location, physician practices within a geographic location (stratified by physician specialty), and visits within individual physician practices. The NHAMCS has a 4-stage sampling design, with sampling based on geographic area, hospitals within a geographic area, clinics within hospitals, and patient visits within clinics. Each visit is weighted to allow calculation of national estimates by using selection probability, adjustment for nonresponse, ratio adjustment to fixed totals, and weight smoothing.

Visit-Level Data

For each visit, participating physicians or their staff members provided patient sociodemographic and clinical information, including visit diagnoses and medications.20

Visit Diagnoses

Visit diagnoses were recorded on the basis of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification, codes. Up to 3 diagnoses were recorded for each visit. Mental health diagnoses were grouped into 8 categories: (1) attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)/hyperkinesis, (2) disruptive behavior disorders, (3) pervasive developmental disorders, (4) sleep problems, (5) anxiety disorders, (6) mood disorders, (7) adjustment disorders, and (8) psychosis (see Appendix 1).

Medications

Medications prescribed, supplied, administered, or continued at the visit were documented. Up to 5 medications were recorded per visit in 1994 and up to 6 medications per visit were recorded in 1995–2002. Starting in 2003, the maximum number of recorded medications per visit was increased to 8. Beginning in 2006, NAMCS/NHAMCS grouped all medications on the basis of Multum’s therapeutic classification system.20 NAMCS/NHAMCS-supplied code was used to convert pre-2006 medication information to Multum’s classification system before analysis.

Children were considered to have been taking a psychotropic if any medication from the following 6 classes was endorsed for the visit: (1) anxiolytics, sedatives, and hypnotics; (2) central nervous system stimulants; (3) antidepressants; (4) antipsychotics; (5) antiadrenergic agents; and (6) mood stabilizers. Appendix 2 lists medications within each class. We did not count antihistamines (eg, diphenhydramine and hydroxyzine) as psychotropic medications because they are used for a variety of nonpsychotropic purposes. Benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and mood stabilizers with indications for seizure treatment were counted as psychotropic medications only if the patient did not have a seizure diagnosis. Antiadrenergic agents were counted as psychotropic medications only if the patient did not have a hypertension diagnosis.

Primary Sources of Visit Payment

Visit payment primary source was designated in NAMCS/NHAMCS as private health insurance, Medicaid/SCHIP (State Children’s Health Insurance Program), self-pay, no charge/charity, or “other.” Because of low numbers of children receiving psychotropic medications in the self-pay, no charge/charity, or “other” groups (n = 70 for entire study period), these groups were combined with the Medicaid/SCHIP group into a single “other type” category for analysis.

Race

Child race was designated in NAMCS/NHAMCS as white, black/African American, Asian, native Hawaiian or Alaskan, or “more than one race reported.” Because of low numbers of children receiving psychotropic medications in the Asian, native Hawaiian or Alaskan, and “more than one race reported” groups (n = 38 for the entire study period), these groups were combined with black/African American patients into a single “nonwhite” category for analysis.

Data Analysis

To account for the complex survey design, sample weights and design variables were applied according to NAMCS/NHAMCS guidelines for all analyses.21–25 Analyses were performed by using SAS statistical software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Descriptive statistics on the rate of visits with at least 1 recorded psychotropic medication were calculated for the sample overall by year. To obtain more robust and reliable estimates for parametric analyses (such that estimates were based on >30 unweighted observations and relative standard error [SE] <30%20 unless otherwise specified), data were combined into 4-year periods (1994–1997, 1998–2001, 2002–2005, and 2006–2009), and rates of visits with any psychotropic medication use, any central nervous system stimulant use, and any coded behavioral diagnosis were reported by sociodemographic subgroup.

Multivariable logistic regression identified factors independently associated with psychotropic use, stimulant use, and behavioral diagnoses among 2- to 5-year-old children. Covariates in the multivariable logistic regression model were age, gender, race, health insurance status, and 4-year study period. The 2006–2009 period served as the reference category in the analyses to determine if the most recent rates of psychotropic usage or behavioral diagnosis differed from that of previous periods. Analyses using the period of highest psychotropic usage as the reference group were also conducted.

The institutional review board of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital determined this study to be exempt from review due to the use of deidentified data.

Results

Table 1 shows study population characteristics.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Nationally Representative Sample of US Outpatient Medical Visits by 2- to 5-Year-Old Children From 1994 to 2009

| n | Weighted Number of Visits (95% CI), in Millions | Weighted Percentage of Visits (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 23 243 | 367 (341–392) | 52.8 (51.9–53.7) |

| Female | 20 355 | 327 (304–351) | 47.2 (46.3–48.0) |

| Age | |||

| 2–3 years | 23 162 | 368 (342–393) | 52.9 (52.1–53.8) |

| 4–5 years | 20 436 | 327 (304–350) | 47.1 (46.2–47.9) |

| Race | |||

| White | 31 854 | 561 (521–602) | 80.9 (79.4–82.3) |

| Nonwhite | 11 744 | 133 (120–146) | 19.1 (17.7–20.6) |

| Health insurance statusa | |||

| Private | 19 125 | 421 (390–453) | 60.7 (58.8–62.6) |

| Other type | 22 968 | 252 (230–273) | 36.3 (34.4–38.1 |

Values do not sum to total due to missing data.

Overall Patterns of Psychotropic Medication Use

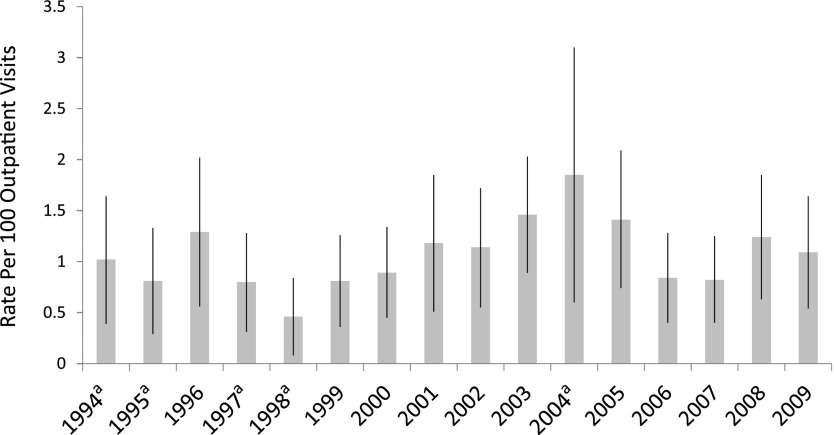

A psychotropic medication was prescribed at 1.07% of office-based medical visits between 1994 and 2009 for 2- to 5-year-old children. Annual rates of visits with psychotropic prescriptions varied from 0.46% in 1998 to 1.85% in 2004 (Fig 1). Rates of psychotropic prescription varied by time period (Table 2). The likelihood of psychotropic prescription was highest in 2002–2005, with the likelihood of treatment in other time periods 33% to 37% less. The 2006–2009 probability of psychotropic use was significantly lower than that in 2002–2005, and did not differ from that in 1994–1997 or 1998–2001 (Table 2). The likelihood of psychotropic use was higher in boys versus girls, in 4 to 5 year olds versus 2 to 3 year olds, in white versus nonwhite children, and in those lacking versus those with private health insurance (Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

Rate of psychotropic medication use (per 100 outpatient medical visits) by study year for 2- to 5-year-old US children. aUnweighted observations <30 or relative SE >30%.

TABLE 2.

Estimated Rates and AORs of Psychotropic Medication Use, CNS Stimulant Use, and Behavioral Diagnoses, by Study Period and Sociodemographic Group, at US Outpatient Medical Visits for 2- to 5-Year-Old Children

| One or More Psychotropic Medication Prescription | One or More CNS Stimulant Prescription | One or More Behavioral Diagnosis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted % (95% CI) [n] | AOR (95% CI) | Weighted % (95% CI) [n] | AOR (95% CI) | Weighted % (95% CI) [n] | AOR (95% CI) | |

| Overall | ||||||

| 1994–2009 | 1.07 (0.92–1.22) [958] | — | 0.58 (0.47–0.69) [390] | — | 1.56 (1.36–1.76) [1563] | — |

| Study Period | ||||||

| 1994–1997 | 0.98 (0.68–1.27) [191] | 1.04 (0.68–1.60) | 0.46 (0.25–0.66) [85] | 0.77 (0.44–1.37) | 1.24 (0.94–1.54) [351] | 0.65 (0.47–0.88) |

| 1998–2001 | 0.83 (0.57–1.09) [220] | 0.99 (0.65–1.50) | 0.34 (0.17–0.51) [86] | 0.64 (0.35–1.17) | 1.19 (0.80–1.58) [326] | 0.68 (0.46–1.00) |

| 2002–2005 | 1.45 (1.07–1.84) [297] | 1.56 (1.05–2.33) | 0.86 (0.54–1.18) [107] | 1.52 (0.89–2.59) | 1.79 (1.32–2.26) [407] | 0.92 (0.65–1.31) |

| 2006–2009 | 1.00 (0.73–1.26) [250] | Referencea | 0.62 (0.41–0.83) [112] | Referenceb | 1.94 (1.56–2.32) [479] | Reference |

| Age | ||||||

| 2–3 years | 0.45 (0.32–0.58) [317] | Reference | 0.15 (0.08–0.22) [63] | Reference | 0.80 (0.62–0.97) [501] | Reference |

| 4–5 years | 1.77 (1.50–2.04) [641] | 3.87 (2.79–5.37) | 1.06 (0.85–1.29) [327] | 7.11 (4.30–11.75) | 2.41 (2.06–2.77) [1062] | 3.12 (2.47–4.12) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 1.31 (1.09–1.53) [605] | 1.64 (1.20–2.25) | 0.86 (0.66–1.05) [281] | 3.14 (1.98–4.97) | 2.09 (1.77–2.41) [1084] | 2.30 (1.76–3.01) |

| Female | 0.80 (0.62–0.99) [353] | Reference | 0.27 (0.17–0.38) [109] | Reference | 0.96 (0.76–1.17) [479] | Reference |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 1.08 (0.91–1.26) [719] | 1.42 (1.04–1.93) | 0.56 (0.43–0.70) [277] | 1.12 (0.72–1.72) | 1.52 (1.29–1.74) [1112] | 1.13 (0.86–1.49) |

| Other | 1.02 (0.74–1.30) [239] | Reference | 0.66 (0.41–0.90) [113] | Reference | 1.74 (1.36–2.11) [451] | Reference |

| Insurance typec | ||||||

| Private | 0.73 (0.56–0.90) [308] | Reference | 0.35 (0.24–0.47) [112] | Reference | 1.01 (0.82–1.20) [491] | Reference |

| Other | 1.61 (1.30–1.92) [614] | 2.38 (1.74–3.27) | 0.97 (0.71–1.23) [271] | 2.89 (1.84–4.54) | 2.45 (2.05–2.84) [1021] | 2.53 (2.00–3.20) |

AORs are from model containing all variables shown in the table. CNS, central nervous system.

Compared with 2002–2005 as the reference category (AOR for 1994–1997: 0.67; 95% CI: 0.44–1.01; AOR for 1998–2001: 0.63; 95% CI: 0.41–0.97; AOR for 2006–2009: 0.64; 95% CI: 0.43–0.95).

Compared with 2002–2005 as the reference category (AOR for 1994–1997: 0.51: 95% CI: 0.28–0.94; AOR for 1998–2001: 0.42; 0.23–0.78; AOR for 2006–2009: 0.67; 95% CI: 0.39–1.23.

Values do not sum to total due to missing data.

Stimulants were the most commonly prescribed psychotropic medication class in all study periods. The stimulant use pattern over time was similar to that of overall psychotropic use, with stimulant prescription likelihood during the 1994–1997 and 1998–2001 periods 49% to 58% lower than that in 2002–2005, whereas the 2006–2009 likelihood of use did not differ from any previous time period (Table 2). No medication class other than stimulants had estimates for all time periods meeting our predetermined level of reliability (>30 unweighted observations and relative SE <30%, see Supplemental Table 4). Estimates for rates of combined psychopharmacology (use of >1 psychotropic class) also fell below our reliability criteria (see Supplemental Table 4).

Patterns of Behavioral Diagnosis

From 1994 to 2009, the overall rate of having ≥1 behavioral diagnosis at office-based medical visits for 2 to 5 year olds was 1.56%, with rates showing a relative increase of 56% from the first study interval to the last (Table 2). The likelihood of having a behavioral diagnosis increased during each 4-year study interval in a stepwise fashion. Boys, older children (4–5 years old), and those lacking private insurance were more likely than children from other groups to have behavioral diagnoses (Table 2). From 1994 to 2009, ADHD was the most common diagnosis with a rate of 0.78%, followed by disruptive behavior, pervasive developmental, sleep, anxiety, mood, and adjustment disorders (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Estimated Rate of Behavioral Diagnoses in the Full Sample and Rate of Psychotropic Medication Use Among Those With Each Diagnosis at US Outpatient Medical Visits for 2- to 5-Year-Old Children From 1994 to 2009

| Rate of Diagnosis, Weighted % (95% CI) [n] | Rate of Psychotropic Medication Receipt for Those With Diagnosis, Weighted % (95% CI) [n] | |

|---|---|---|

| Any behavioral diagnosis | 1.56 (1.36–1.76) [1563] | 35.89 (31.50–40.27) [505] |

| ADHD | 0.78 (0.64–0.91) [694] | 57.79 (51.70–63.88) [370] |

| Disruptive behavior | 0.28 (0.21–0.36) [341] | 26.43 (18.54–34.32) [81] |

| Pervasive developmental disorder | 0.28 (0.20–0.37) [284] | 15.64 (11.08–20.21) [74] |

| Sleep disorder | 0.16 (0.10–0.22) [126] | 16.41 (3.79–29.03)a [26] |

| Anxiety disorder | 0.12 (0.08–0.17) [210] | 26.25 (14.83–37.68) [48] |

| Mood disorder | 0.09 (0.05–0.14) [85] | 65.69 (41.67–89.72) [41] |

| Adjustment disorder | 0.06 (0.03–0.09) [117] | 21.40 (2.56–40.25)a [15] |

| Psychosis | 0.01 (0–0.02)a [7] | 97.05 (81.38–100)a [6] |

| No behavioral diagnosis | 98.44 (98.24–98.64) [42 035] | 0.52 (0.41–0.63) [453] |

Raw number <30 or relative SE of estimate >30%.

Psychotropic Medication Use Among Children With Behavioral Diagnoses

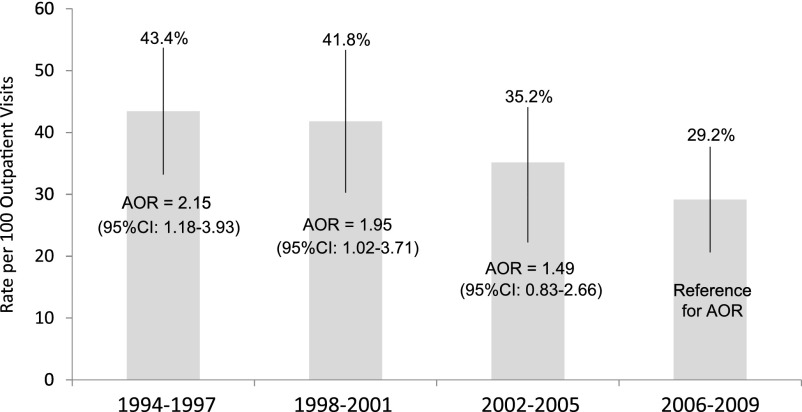

Among children with ≥1 behavioral diagnosis, the psychotropic medication rate during the 1994–2009 study period was 35.9% compared with 0.5% among children without behavioral diagnoses (Table 3). Psychotropic prescription rates were highest for children with ADHD and mood disorder diagnoses (57.8% to 65.7%) (Table 3). Psychotropic usage rates among children with behavioral diagnoses decreased over the study period from 43.4% in 1994–1997 to 29.2% in 2006–2009 (Fig 2). In fact, the likelihood of psychotropic use among children with a behavioral diagnosis in 1994–1997 was more than double that of 2006–2009 (Fig 2).

FIGURE 2.

Among 2- to 5-year-old US children with ≥1 behavioral diagnosis, rate (per 100 outpatient medical visits) and AOR of psychotropic medication use by study interval.

Discussion

This study provides the first evaluation, to our knowledge, of changes in psychotropic medication rates in a nationally representative sample of very young children from the 1990s to the later 2000s. The likelihood of psychotropic medication use in 2 to 5 year olds was higher in the early 2000s (2002–2005) compared with the 1990s, but then stabilized such that the 2006–2009 likelihood did not differ from that of the 1994–1997 and 1998–2001 periods. In contrast, the likelihood of receiving a behavioral diagnosis increased throughout the study interval. Surprisingly, increased diagnosis was not accompanied by an increased propensity toward psychotropic prescription, because the likelihood of psychotropic use in 2006–2009 was half that of the 1994–1997 period among those with a behavioral diagnosis.

The temporal trends in psychotropic prescription we observed were consistent with those of previous non–nationally representative studies documenting a substantial increase in preschool psychotropic use from 1991 to 2001.3,4 The psychotropic usage stabilization we found in the late 2000s was also observed in a study in privately insured, very young children13 and in a nationally representative sample that limited its examination to psychostimulants.15 The overall psychotropic prescription rates we documented were generally comparable to those of previous US preschool samples. Our 1994–1997 and 1998–2001 psychotropic prescription rates were within the ranges found in previous studies of these time intervals (0.8% to 1.8%7,17 and 0.3% to 2.3%,4,12,13 respectively). Our 2002–2005 psychotropic usage rate was higher than that of a North Carolina cohort (0.3%) during this time period,26 with the discrepancy likely explained by our relatively older sample (2 to 5 years old compared with 0 to 4 years old) or by state-specific variation in use, because previous studies have documented substantial region-specific variation in psychotropic prescription rates.27–29 Our 2006–2009 psychotropic prescription rate was somewhat lower than the rate (1.5%) documented in a privately insured sample.13 The reasons for this discrepancy are unclear, but may be due to differences in sample racial compositions (because privately insured samples tend to have higher proportions of whites compared with nationally representative samples30–32) or additional medications being counted as psychotropic medications in the previous study (ie, the previous study does not specify whether hydroxyzine or diphenhydramine were included, whereas we excluded them).

Stimulants were the most commonly prescribed psychotropic class in ours as well as previous studies in this age group.3,4,12,13 Our 1994–1997, 1998–2001, and 2006–2009 stimulant prescription rates were all within the ranges observed previously in these time intervals.3,4,7,13–15,17 Our 2002–2005 stimulant prescription rate was somewhat higher than the 2002–2003 rate (0.3%) observed by Zuvekas and Vitiello,15 with the discrepancy likely explained by our use of a relatively older sample (2 to 5 years old versus 0 to 5 years old).

We found that the probability of receiving a behavioral diagnosis increased in a stepwise fashion in each successive study interval, with a 55% higher likelihood observed in the last study interval compared with the first. There is a paucity of data on rates of behavioral diagnoses at nationally representative preschool outpatient medical visits. Some studies in regional and privately insured samples are available, although their methodology differed from our own. A 1997–1998 study of preschool regional HMO visits documented a somewhat higher rate (2%) for emotional/behavior symptoms and/or diagnoses, whereas our rate during this time period included only coded diagnoses.12 Consistent with our findings, Olfson et al13 found an increasing rate of behavioral diagnosis coding from 1999–2001 (3.2%) to 2007 (3.9%), with diagnostic rates at both time points higher than our observations, possibly because unlike the previous study, we did not count mental retardation and communication/learning disorders as behavioral diagnoses. Our study aligned with previous preschool samples in that ADHD was the most common behavioral diagnosis.12,13

Our findings reveal not only a stabilization of overall psychotropic use over time in very young children but a diminished likelihood of psychotropic use for those with behavioral diagnoses. This finding may be explained in part by public response to US FDA warnings on psychotropic medications in the mid- to late-2000s, including the 2004 black box warning on antidepressant medications regarding child and adolescent suicidality risk,33 the 2005 Public Health Advisory regarding potential for serious cardiovascular events with amphetamines,9 the 2005 black box warning on atomoxetine regarding potential sudden death and suicidal ideation,10 the 2006 FDA Advisory Committee recommendation for a black box warning on psychostimulants (which was later reversed),11,34 and the 2007 directive to ADHD medication manufacturers to notify patients about adverse cardiovascular events and psychiatric symptoms.11 Indeed, although not focused on preschoolers, several previous studies have shown that rates of pediatric antidepressant use were significantly decreased after the 2004 FDA black box warnings,35–37 which is congruent with the antidepressant usage pattern we observed (see Supplemental Table 4). However, this phenomenon did not occur uniformly across psychotropic classes; similar to 3 previous studies, only 1 of which looked at 0 to 5 year olds separately from older children,15,34,38 we did not find that the likelihood of stimulant prescription was significantly different in the periods before and after the FDA stimulant warnings.

We found that very young children who were older, male, white, and lacking private insurance were more likely to receive psychotropic medications. This finding is consistent with previous studies documenting higher rates of psychotropic use in older compared with younger,4,12 male compared with female,4,7,12 and white compared with African American preschool children.4,17 Our finding that children lacking private insurance were more likely than those with private insurance to take psychotropic medications confirmed results of 2 previous preschool samples3,12 and a US nationally representative 1996 survey of 0 to 18 year olds,7 but contrasted with findings from a 1996 preschool sample.17 Additional study is needed to determine why certain groups of very young children are more likely to receive psychotropic medications and to determine the appropriateness of these prescriptions. Possible reasons for sociodemographic disparities in use may include factors such as certain groups having higher rates of behavioral disorders (due to increased exposure39,40 or susceptibility41 to mental health risk factors), a bias toward higher rates of disorder identification,42 more favorable attitudes toward psychotropic medication use,43 or diminished access to or acceptability of behavioral interventions.44

Our study has several limitations. The relatively small number of 2- to 5-year-old children receiving psychotropic medications makes it difficult to provide reliable yearly usage estimates and prohibits the reliable estimation of rates for each medication class separately for the 4-year time intervals, with the exception of the psychostimulants. Specifically, changes in antidepressant, atypical antipsychotic, antiadrenergic, and mood stabilizer usage over time are of substantial interest, but we cannot make definitive comments on them. Due to the low numbers of preschool children using >1 psychotropic class, we also cannot draw firm conclusions about trends in psychotropic polypharmacy in this age group over time. In addition, NAMCS and NHAMCS medication data were recorded by physicians or their office staff. We were unable to cross-check data with pharmacy records or patient/family reports of use, so it is not known if psychotropic prescriptions were actually filled and administered. Data are also limited in the number of medications (5–8) and diagnoses (3) recorded for each visit, so if children had psychotropic medications and behavioral diagnoses that were listed more distally in their records, they would not have been recorded. In addition, data on diagnoses reflect physicians’ coding practices, but children did not have standardized diagnostic assessments to determine the validity of their diagnoses.

Conclusions

Despite public concern about an inexorable increase in pediatric psychotropic medication use, we found that the likelihood of psychotropic medication prescription in nationally representative office medical visits for 2- to 5-year-old children peaked in 2002–2005, and then stabilized such that the 2006–2009 likelihood did not differ from that of the 1994–1997 and 1998–2001 periods. Stabilization of psychotropic prescriptions cannot be explained by a diminished emphasis on mental health issues during preschool medical visits, because the likelihood of receiving a behavioral diagnosis increased over time. In fact, among those with behavioral diagnoses, psychotropic usage decreased over time from 43% in 1994–1997 to 29% in 2006–2009. Future study is needed to determine why boys, white children, and those lacking private insurance had an increased likelihood of psychotropic use, and to design interventions to ensure that differences in use are congruent with well-informed family goals and preferences. In addition, our findings underscore the need to ensure that doctors of very young children who are diagnosing ADHD, the most common diagnosis, and prescribing stimulants, the most common psychotropic medications, are using the most up-to-date and stringent diagnostic criteria and clinical practice guidelines.45 Furthermore, given the continued use of psychotropic medications in very young children and concerns regarding their effects on the developing brain, future studies on the long-term effects of psychotropic medication use in this age group are essential.46

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Ms Heather Matheson for her technical assistance in data acquisition and institutional review board protocol submission.

Glossary

- ADHD

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- AOR

adjusted odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- HMO

health maintenance organization

- NAMCS

National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey

- NHAMCS

National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey

APPENDIX 1.

ICD-9-CM Codes Used to Identify Behavioral Diagnoses

| Category | ICD-9-CM codes |

|---|---|

| ADHD | 314, 314.0–314.9 |

| Disruptive behavior disorders | 309.3, 312, 312.0–312.23, 312.3–312.35, 312.4–312.9, 313.81, 313.89 |

| Pervasive developmental disorders | 299, 299.0–299.91 |

| Sleep problems | 307.40–307.42, 307.45–307.49, 327, 327.0–327.19, 327.3–327.8, 780.50, 780.52, 780.54–780.56, 780.58–780.59 |

| Anxiety disorders | 293.84, 300, 300.0–300.02, 300.09, 300.2, 300.20–300.23, 300.29, 300.3, 300.7, 308.0–308.9, 309.21, 309.24, 309.81, 312.39, 313.0, 313.21, 313.23 |

| Mood disorders | 296, 296.0–296.99, 300.4, 301.13, 309.0, 311 |

| Adjustment disorders | 309, 309.1–309.9 except for 309.21 and 309.81 |

| Psychosis | 295, 295.0-295.95, 297, 297.0-297.9, 298, 298.0-298.9, 301.2-301.22 |

ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification.

APPENDIX 2.

Classes of Psychotropic Medications

| Anxiolytics/ Sedatives/ Hypnotics | CNS Stimulants | Antidepressants | Antipsychotics | Antiadrenergic Agents | Mood Stabilizersa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alprazolam | Amphetamine | Amitriptyline | Aripiprazole | Clonidine | Carbamazepine |

| Buspirone | Amphetamine-dextroamphetamine | Amoxapine | Chlorpromazine | Guanfacine | Divalproex |

| Chloral hydrate | Atomoxetine | Bupropion | Fluphenazine | Gabapentin | |

| Clonazepam | Benzphetamine | Citalopram | Haloperidol | Lamotrigine | |

| Clorazepate | Caffeine | Desipramine | Lithiumb | Oxcarbazepine | |

| Diazepam | Dexmethylphenidate | Escitalopram | Loxapine | Topiramate | |

| Doxepin | Dextroamphetamine | Fluoxetine | Olanzapine | Valproic acid | |

| Ethchlorvynol | Diethylpropion | Fluvoxamine | Pimozide | ||

| Lorazepam | Lisdexamphetamine | Imipramine | Prochlorperazine | ||

| Midazolam | Methylphenidate | Mirtazapine | Quetiapine | ||

| Pentobarbital | Pemoline | Nefazodone | Risperidone | ||

| Phenobarbital | Phendimetrazine | Nortriptyline | Thioridazine | ||

| Oxazepam | Phentermine | Paroxetine | Ziprasidone | ||

| Zaleplon | Sertraline | ||||

| Zolpidem | Trazodone | ||||

| Venlafaxine |

CNS, central nervous system.

The Mood Stabilizers class is a subset of medications drawn from the Anticonvulsant category of Multum’s therapeutic classification system (the drug classification system used by the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey [NAMCS and NHAMCS]).

As per Multum’s therapeutic classification system, lithium was included in the antipsychotic class.

Footnotes

Dr Chirdkiatgumchai conceptualized and designed the study, acquired the data, analyzed and interpreted the data, and drafted and revised the initial manuscript; Ms Xiao acquired the data, analyzed the data, and participated in manuscript revision; Dr Fredstrom acquired the data, analyzed and interpreted the data, and participated in manuscript revision; Dr Adams analyzed and interpreted the data and participated in manuscript revision; Drs Epstein, Brinkman, and Kahn participated in data analysis and interpretation and manuscript revision; Dr Shah participated in data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation and revised the manuscript; Dr Froehlich conceptualized and designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and drafted and revised the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported by the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center Division of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics and the National Institute of Mental Health grants K23 MH083881 (T.E.F.) and K23 MH083027 (W.B.B.). Data analyzed for this investigation were collected by the National Center of Health Statistics. All analyses, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and not the National Center of Health Statistics, which is responsible only for the initial data.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Connor DF. Preschool attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a review of prevalence, diagnosis, neurobiology, and stimulant treatment. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2002;23(1 suppl):S1–S9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keenan K, Wakschlag LS. More than the terrible twos: the nature and severity of behavior problems in clinic-referred preschool children. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2000;28(1):33–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zito JM, Safer DJ, dosReis S, Gardner JF, Boles M, Lynch F. Trends in the prescribing of psychotropic medications to preschoolers. JAMA. 2000;283(8):1025–1030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zito JM, Safer DJ, Valluri S, Gardner JF, Korelitz JJ, Mattison DR. Psychotherapeutic medication prevalence in Medicaid-insured preschoolers. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2007;17(2):195–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fanton J, Gleason MM. Psychopharmacology and preschoolers: a critical review of current conditions. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2009;18(3):753–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenhill LL. The use of psychotropic medication in preschoolers: indications, safety, and efficacy. Can J Psychiatry. 1998;43(6):576–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olfson M, Marcus SC, Weissman MM, Jensen PS. National trends in the use of psychotropic medications by children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(5):514–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Food and Drug Administration. Drugs@FDA: FDA approved drug products. Available at: www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm?CFID=9212717&CFTOKEN=65c9d32a63c480ae-2C707AA2-C85D-03EE-ECDFC78E6B2A19D7. Accessed April 3, 2013

- 9.US Food and Drug Administration. US Food and Drug Administration Public Health Advisory for Adderall and Adderall XR. Published 2005. Available at: www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/DrugSafetyInformationforHeathcareProfessionals/PublicHealthAdvisories/ucm051672.htm. Accessed March 12, 2013

- 10.US Food and Drug Administration. US Food and Drug Administration Public Health Advisory: suicidal thinking in children and adolescents being treated with atomoxetine. Published 2005. Available at: www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/DrugSafetyInformationforHeathcareProfessionals/PublicHealthAdvisories/ucm051733.htm. Accessed March 11, 2013

- 11.US Food and Drug Administration. US Food and Drug Administration directs ADHD drug manufacturers to notify patients about cardiovascular adverse events and psychiatric adverse events. Published 2007. Available at: www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/2007/ucm108849.htm. Accessed March 9, 2013

- 12.DeBar LL, Lynch F, Powell J, Gale J. Use of psychotropic agents in preschool children: associated symptoms, diagnoses, and health care services in a health maintenance organization. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(2):150–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olfson M, Crystal S, Huang C, Gerhard T. Trends in antipsychotic drug use by very young, privately insured children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(1):13–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zuvekas SH, Vitiello B, Norquist GS. Recent trends in stimulant medication use among U.S. children. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):579–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zuvekas SH, Vitiello B. Stimulant medication use in children: a 12-year perspective. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(2):160–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel NC, Crismon ML, Hoagwood K, et al. Trends in the use of typical and atypical antipsychotics in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(6):548–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zito JM, Safer DJ, DosReis S, et al. Psychotropic practice patterns for youth: a 10-year perspective. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(1):17–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About the ambulatory health care surveys. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/about_ahcd.htm. Accessed August 20, 2012

- 19.Shah SS, Wood SM, Luan X, Ratner AJ. Decline in varicella-related ambulatory visits and hospitalizations in the United States since routine immunization against varicella. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29(3):199–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About the ambulatory health care surveys. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/ahcd_questionnaires.htm. Accessed August 20, 2012

- 21.McCaig LF, Burt CW. Understanding and interpreting the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: key questions and answers. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(6):716–721, e711 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Cherry D. Understanding and using NAMCS and NHAMCS data: data tools and basic programming techniques. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/ppt/ahcd/Cherry_30.ppt. Accessed April 9, 2012

- 23.Hsiao CJ. Understanding and using NAMCS and NHAMCS data: data tools and basic programing techniques. Published 2010. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/ppt/nchs2010/03_Hsiao.pdf. Accessed February 23, 2012

- 24.Nawar E. Understanding and using NAMCS and NHAMCS data: part 2—using public-use files. Published 2006. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/ppt/duc2006/Nawar_41.ppt. Accessed January 26, 2012

- 25.McCaig L, Woodwell D. Overview of NAMCS and NHAMCS. Published 2008. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/ppt/ahcd/McCaigWoodwell_20.ppt. Accessed April 9, 2012

- 26.Ellis AR. The administration of psychotropic medication to children ages 0-4 in North Carolina: an exploratory analysis. N C Med J. 2010;71(1):9–14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cox ER, Motheral BR, Henderson RR, Mager D. Geographic variation in the prevalence of stimulant medication use among children 5 to 14 years old: results from a commercially insured US sample. Pediatrics. 2003;111(2):237–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bokhari F, Mayes R, Scheffler RM. An analysis of the significant variation in psychostimulant use across the U.S. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14(4):267–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fulton BD, Scheffler RM, Hinshaw SP, et al. National variation of ADHD diagnostic prevalence and medication use: health care providers and education policies. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(8):1075–1083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flores G, Olson L, Tomany-Korman SC. Racial and ethnic disparities in early childhood health and health care. Pediatrics. 2005;115(2):e183–e193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cornelius LJ. Barriers to medical care for white, black, and Hispanic American children. J Natl Med Assoc. 1993;85(4):281–288 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Newacheck PW, Hughes DC, Cisternas M. Children and health insurance: an overview of recent trends. Health Aff (Millwood). 1995;14(1):244–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.US Food and Drug Administration. US Food and Drug Administration post-marketing drug safety information for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Published 2004. Available at: www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/DrugSafetyInformationforHeathcareProfessionals/PublicHealthAdvisories/ucm161679.htm. Accessed March 11, 2013

- 34.Barry CL, Martin A, Busch SH. ADHD medication use following FDA risk warnings. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2012;15(3):119–125 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Libby AM, Brent DA, Morrato EH, Orton HD, Allen R, Valuck RJ. Decline in treatment of pediatric depression after FDA advisory on risk of suicidality with SSRIs. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):884–891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clarke G, Dickerson J, Gullion CM, DeBar LL. Trends in youth antidepressant dispensing and refill limits, 2000 through 2009. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2012;22(1):11–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nemeroff CB, Kalali A, Keller MB, et al. Impact of publicity concerning pediatric suicidality data on physician practice patterns in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(4):466–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kornfield R, Watson S, Higashi AS, et al. Effects of FDA advisories on the pharmacologic treatment of ADHD, 2004-2008. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(4):339–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Larson K, Russ SA, Kahn RS, Halfon N. Patterns of comorbidity, functioning, and service use for US children with ADHD, 2007. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):462–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Froehlich TE, Lanphear BP, Auinger P, et al. Association of tobacco and lead exposures with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):e1054–e1063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Froehlich TE, Anixt JS, Loe IM, Chirdkiatgumchai V, Kuan L, Gilman RC. Update on environmental risk factors for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13(5):333–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gaub M, Carlson CL. Gender differences in ADHD: a meta-analysis and critical review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(8):1036–1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brinkman WB, Epstein JN. Treatment planning for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: treatment utilization and family preferences. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011;Jan 17(5):45–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berkoff MC, Leslie LK, Stahmer AC. Accuracy of caregiver identification of developmental delays among young children involved with child welfare. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2006;27(4):310–318 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wolraich M, Brown L, Brown RT, et al. Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management . ADHD: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):1007–1022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Coyle JT. Psychotropic drug use in very young children. JAMA. 2000;283(8):1059–1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.