Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES:

Emergency department (ED) visits present an opportunity to deliver brief interventions (BIs) to reduce violence and alcohol misuse among urban adolescents at risk for future injury. Previous analyses demonstrated that a BI resulted in reductions in violence and alcohol consequences up to 6 months. This article describes findings examining the efficacy of BIs on peer violence and alcohol misuse at 12 months.

METHODS:

Patients (14–18 years of age) at an ED reporting past year alcohol use and aggression were enrolled in the randomized control trial, which included computerized assessment, random assignment to control group or BI delivered by a computer or therapist assisted by a computer. The main outcome measures (at baseline and 12 months) included violence (peer aggression, peer victimization, violence-related consequences) and alcohol (alcohol misuse, binge drinking, alcohol-related consequences).

RESULTS:

A total of 3338 adolescents were screened (88% participation). Of those, 726 screened positive for violence and alcohol use and were randomly selected; 84% completed 12-month follow-up. In comparison with the control group, the therapist assisted by a computer group showed significant reductions in peer aggression (P < .01) and peer victimization (P < .05) at 12 months. BI and control groups did not differ on alcohol-related variables at 12 months.

CONCLUSIONS:

Evaluation of the SafERteens intervention 1 year after an ED visit provides support for the efficacy of computer-assisted therapist brief intervention for reducing peer violence.

KEY WORDS: adolescents, youth violence, alcohol, emergency department

What's Known on This Subject:

Youth violence and alcohol misuse are a preventable public health problem. Previous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of brief interventions in the emergency department (ED) in reducing alcohol misuse and related consequences among older adolescents and adults.

What This Study Adds:

This study supports the efficacy of brief interventions in the ED in reducing peer aggression and victimization 12 months after ED visit. The previous reductions in alcohol consequences noted at 6 months follow-up were not sustained at 12 months.

Violence is a leading cause of death for adolescents,1 with alcohol use closely associated.2 The relationship between violent behaviors and alcohol use is theorized to be part of a problem behavior proneness during adolescence3–10 and is not simply due to acute intoxication effects.11 Among adolescents who report binge drinking, fighting is more severe and more frequent than among nondrinkers.12 Adolescent drinkers are at increased risk for injury13,14 and violence (eg, physical aggression),15 although the injuries may not necessarily occur while under the influence of alcohol. Intervention programs for youth violence are essential, because aggressive behaviors and alcohol use often show a developmental progression and are related to long-term problems.16,17

The emergency department (ED) is an important setting for medical care among adolescents, especially underinsured and uninsured patients.18,19 ED-based prevention programs may reach adolescents who lack a primary care physician or who do not attend school regularly. Recently, ED-based interventions for youth violence20–23 or alcohol use24–27 have increased in number. Findings from the SafERteens study, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of a brief intervention (delivered by a therapist with computer assistance [TBI] or delivered by computer alone [CBI]) among adolescents presenting to an urban ED who screened positive for violence and alcohol use, showed the brief interventions (BIs) positively changed alcohol and violence-related attitudes and self-efficacy.28 In addition, the TBI significantly reduced violent behaviors (eg, peer victimization, peer aggression, consequences of fighting), and both the TBI and CBI significantly reduced alcohol-related consequences up to 6 months after the ED visit.28,29 This current article extends previous findings by examining 12-month outcomes of the interventions.

Specifically, the objectives of this article were to determine the sustained efficacy of the SafERteens interventions on peer violence (ie, peer aggression, peer victimization, and violence consequences) and alcohol-related variables (alcohol misuse, binge drinking, alcohol-related consequences) at 12 months. It was hypothesized a priori that the BIs would result in significant decreases in peer violence and alcohol-related variables relative to the control condition at 12 months.

Methods

Study Setting

The SafERteens RCT took place at a level I trauma center, Hurley Medical Center, in Flint, Michigan. A National Institutes of Health Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained. Study procedures were approved by the study hospital in Flint as well as the University of Michigan Institutional Review Boards for Human Subjects.

Participants

Adolescent ED patients (14–18 years of age) presenting for medical illness or injury were eligible for screening. Adolescents seeking care for acute sexual assault or suicidal ideation, altered mental status precluding consent, or who were medically unstable (ie, abnormal vital signs) were excluded.

Study Protocol

Adolescents were approached from 12 pm to 11 pm, 7 days per week (September 2006 to September 2009), excluding major holidays. Assent/consent by the adolescent, and the parent/guardian if the adolescent was <18 years old, was obtained.

Study Eligibility

After completing the 15-minute computerized survey, participants reporting past-year aggressive behaviors (see Measures) and alcohol consumption (ie, consumed alcohol >2 or 3 times in the past year)30 were eligible for the RCT.

RCT Procedures

After assent/consent for the RCT, participants who completed a computerized baseline assessment were randomly selected (stratified by gender and age: 14–15, 16–18 years), and assigned to 1 of the 3 study conditions (TBI, CBI, control) during the ED visit. The median time for the CBI intervention was 29 minutes, and median time for the TBI was 37 minutes. Participants assigned to the control received a trifold brochure with community resources.

Follow-Up Survey

The 12-month follow-up data were obtained via self-administered computer survey.31–33

Twelve-month surveys were completed in the same manner as the 3- and 6-month follow-ups, at the ED or at a convenient location (eg, home, library, or restaurant); remuneration was $35 for the 12-month survey.

Measures

Demographics

Questions included age, gender, race, ethnicity, and receipt of public assistance.30

Alcohol Use

Past-year alcohol misuse was assessed with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption (AUDIT-C)34,35; with a cutoff of ≥3 screening positive for alcohol misuse.36 In addition, the binge-drinking question (5 or more drinks)36 of the AUDIT-C was examined separately as a binary variable (no/yes).

Alcohol Consequences

Past-year alcohol-related consequences were measured by 17 items from the Problem Oriented Screening Instrument for Teenagers37 (eg, missed school, trouble getting along with friends because of drinking), with a cutoff of ≥2 screening positive for an alcohol use disorder.38

Peer Violence

Items from the conflict tactic scale39,40 assessed past-year severe aggression toward peers (eg, hit or punched, serious physical fighting, used a knife/gun, etc). Severe past-year peer aggression (4 items) was computed as a binary variable (no/yes).41 Past-year peer victimization (being a victim of moderate or severe peer violence) was assessed by collapsing the moderate and severe conflict tactic scale items into 2 items. A binary variable was then created to indicate if teens reported any peer victimization (no/ yes).

Violence Consequences

By use of a 7-item scale described in previous work,29 participants identified consequences of past-year fighting (ie, trouble at school, family or friends suggested you stop, arguments with family or friends, trouble getting along with friends, felt cannot control fighting). A violence consequences summary variable was created based on endorsing yes to any item (no/yes).

Visit Type

Current ED visit reason was abstracted from the medical chart as medical illness (eg, abdominal pain, asthma), or injury (International Classification of Diseases–Ninth Revision– intentional [E950–E969] or unintentional [E800–E869, E880–E929]). Chart reviews were audited for reliability by using established criteria.42

SafERteens BI

The intervention described previously28 was designed to be relevant for urban youth, who at this study site were ∼50% African American. The TBI was facilitated by a tablet computer that displayed screens to prompt sections of content for the therapist to deliver, including tailored feedback. The CBI was a stand-alone interactive program28 with touch screens and audio via headphones. Both delivery modes were based on principles of motivational interviewing,43,44

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed by using SAS Version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). First, descriptive statistics were computed for the total sample and by assigned condition. Second, for descriptive purposes, because outcomes were examined by using binary variables, percent change is presented. Third, models predicting 12-month outcomes were estimated by using generalized estimating equations (GEEs).45 GEE analyses use all data available for participants, including those lost to attrition, and allow for observed variable distributions (eg, logit). Because of initial differences in dropping out of school by condition, this variable was controlled for in analysis; however, findings did not differ so models are presented without this covariate. There were no significant differences between conditions on age, race, gender; therefore, these variables were not included in the GEE analysis. An intent-to-treat approach was used. All randomly assigned participants were included whether the intervention was received or not (>95% received their assigned intervention during the ED visit).

In these GEE analyses, a significant group by time interaction effect indicated that the intervention condition significantly differed from the control condition over time in the outcome examined. Regarding effect size, the number needed to treat is presented, indicating the number of participants in the BI, relative to the control, who would need to receive the BI to prevent that outcome in 1 youth. At 3 and 6 months, the effects were noted in dichotomous treatment of the variables and not the continuous variables. The analyses focused on evaluating if effects noted at 6 months were sustained at 12 months; therefore, only dichotomous outcomes were examined. The analyses presented were adequately powered to detect differences in outcomes between each BI condition (TBI and CBI) and the control condition, not between the TBI and CBI conditions.

Results

Flow Chart

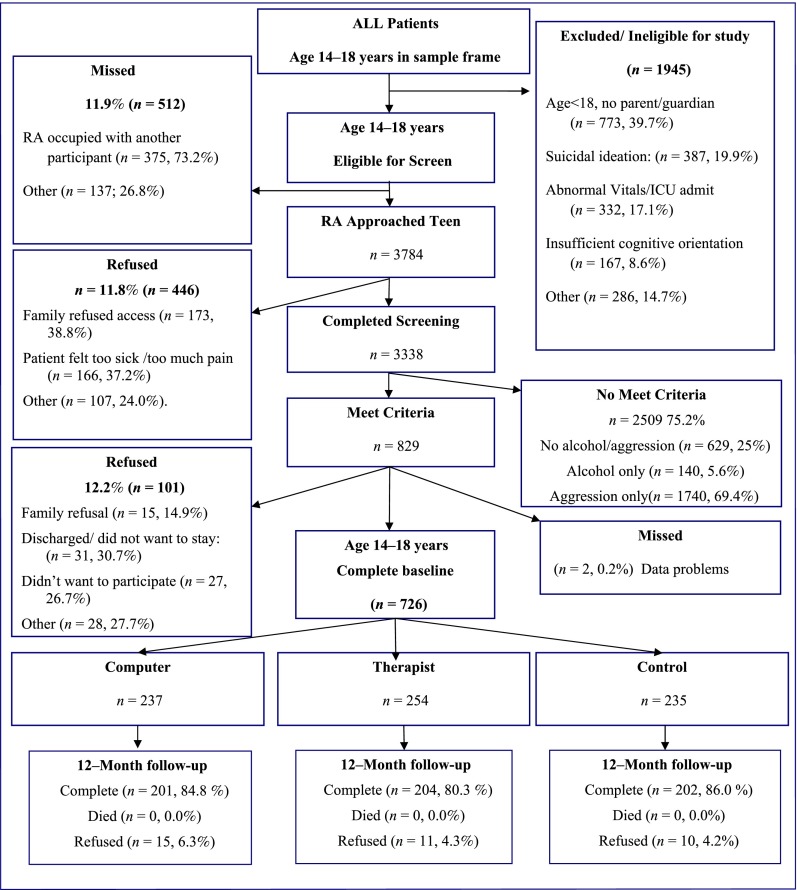

During the trial, 88.1% (n = 3784) of the 4296 potentially eligible patients were approached; 3338 completed screening; 829 met study criteria; and 726 completed the baseline survey (see ref 29 for additional details; Fig 1). Of these, the 12-month follow-up rate was 83.6% (n = 607/726).

FIGURE 1.

SafERteens flow chart (September 2006 to September 2009).

Sample Description

Details regarding the sample characteristics are presented elsewhere (see ref 29 for additional details. In brief, the sample was 43.5% male and 55.9% African American (39.1% white; 5.0% other; 6.5% Hispanic ethnicity). The mean age was 16.8 (SD = 1.3). More than half of the sample (57.4%) received public assistance, and 10.1% dropped out of school. Regarding the ED chief presenting compliant, 26.8% was for injury, 7.5% for intentional injury, and 65.7% for a medical condition; 93.0% were discharged on the day of recruitment.

Participants in the TBI condition showed a 43% reduction in severe peer aggression in comparison with 26% reductions in both the CBI and control conditions (Table 1). Participants in the TBI condition showed a 23% reduction in peer victimization in comparison with 17% and 12% reductions in the CBI and control conditions, respectively. Participants in the TBI condition showed a 36.1% reduction in violence consequences, whereas the CBI and control conditions showed ∼31% reductions.

TABLE 1.

Percent reporting violence and alcohol outcomes at baseline and 12 months

| Peer Violence | Baseline n (%) | 12-Month Follow-up n (%) | % Change From Baseline to 12 mo |

|---|---|---|---|

| Severe peer aggression | |||

| Therapist group | 210 (82.7) | 79 (39.3) | −43.4 |

| Computer group | 179 (75.5) | 98 (49.3) | −26.2 |

| Control group | 183 (77.9) | 104 (52.0) | −25.9 |

| Peer victimization | |||

| Therapist group | 121 (47.6) | 50 (24.9) | −22.7 |

| Computer group | 103 (43.5) | 52 (26.1) | −17.4 |

| Control group | 99 (42.3) | 60 (30.0) | −12.3 |

| Violence consequences | |||

| Therapist | 213 (83.9) | 96 (47.8) | −36.1 |

| Computer | 183 (77.2) | 92 (46.2) | −31.0 |

| Control | 195 (83.0) | 103 (51.5) | −31.5 |

| Any binge drinking | |||

| Therapist group | 134 (52.8) | 79 (38.7) | −14.1 |

| Computer group | 115 (48.5) | 61 (30.3) | −18.2 |

| Control group | 127 (54.0) | 73 (36.1) | −17.9 |

| Alcohol misuse: AUDIT-C ≥3 | |||

| Therapist group | 127 (50.0) | 76 (37.3) | −12.7 |

| Computer group | 108 (45.6) | 58 (28.9) | −16.7 |

| Control group | 112 (47.7) | 70 (34.7) | −13.0 |

| Alcohol consequences ≥2 | |||

| Therapist | 122 (48.0) | 42 (20.6) | −27.4 |

| Computer | 102 (43.0) | 40 (19.9) | −23.1 |

| Control | 102 (43.4) | 35 (17.3) | −26.1 |

GEE Models Predicting 12-Month Violence and Alcohol Outcomes

As shown in Table 2, TBI participants were less likely to report severe peer aggression at 12 months in comparison with controls (group by time interaction χ2 = 10.82, P < .01). TBI participants were also less likely to report peer victimization at 12 months in comparison with controls (group by time interaction χ2 = 4.05; P = .04). The group by time interaction effect was not significant for the TBI in comparison with controls for violence consequences at 12 months. No significant group by time interaction effects were observed for the CBI participants in comparison with the controls on any of the violence variables examined. As shown in Table 3, no significant group by time interactions effects were found for TBI or CBI in comparison with control for any of the alcohol related variables examined.

TABLE 2.

GEE Models Examining 12-Month Violence Outcomes by Intervention Condition

| Estimate (SE) | P | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Severe peer aggression a | |||

| Time | −1.12 (0.19) | <.001 | 0.33 (0.22–0.47) |

| Computer group | −0.13 (0.22) | .55 | 0.88 (0.57–1.34) |

| Therapist group | 0.30 (0.23) | .18 | 1.36 (0.87–2.12) |

| Computer group × time | −0.06 (0.26) | .83 | 0.94 (0.56–1.58) |

| Therapist group × time | -0.91 (0.27) | <.01 | 0.40 (0.23–0.69) |

| Peer victimization b | |||

| Time | −0.52(0.18) | <.01 | 0.60 (0.42–0.85) |

| Computer group | 0.05 (0.19) | .76 | 1.06 (0.73–1.52) |

| Therapist group | 0.22 (0.18) | .22 | 1.25 (0.87–1.79) |

| Computer group × time | −0.27 (0.27) | .32 | 0.77 (0.45–1.30) |

| Therapist group × time | −0.51 (0.26) | .04 | 0.60 (0.36–0.99) |

| Violence consequences c | |||

| Time | −1.51 (0.19) | <.001 | 0.22 (0.15–0.32) |

| Computer group | −0.36 (0.23) | .12 | 0.70 (0.44–1.10) |

| Therapist group | 0.06 (0.24) | .79 | 1.07 (0.66–1.72) |

| Computer group × time | 0.16 (0.26) | .53 | 1.17 (0.71–1.95) |

| Therapist group × time | −0.21(0.27) | .43 | 0.81 (0.47–1.38) |

CI, confidence interval.

χ2 = 10.82; P < .01.

χ2 = 4.05; P = .04.

χ2 = 0.62; P = .43.

TABLE 3.

GEE Models Examining 12-Month Alcohol Outcomes by Intervention Condition

| Estimate (SE) | P | Odds Ratio (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any binge drinking a | |||

| Time | −0.68 (0.18) | <.001 | 0.51 (0.36–0.72) |

| Computer group | −0.19 (0.18) | .31 | 0.83 (0.58–1.19) |

| Therapist group | −0.05 (0.18) | .77 | 0.95(0.66–1.36) |

| Computer group × time | −0.11 (0.26) | .67 | 0.89 (0.54–1.49) |

| Therapist group × time | 0.14 (0.24) | .55 | 1.15 (0.72–1.86) |

| Alcohol misuse: AUDIT-C ≥3b | |||

| Time | −0.48 (0.17) | <.01 | 0.62 (0.44–0.87) |

| Computer group | −0.05 (0.18) | .79 | 0.95 (0.66–1.37) |

| Therapist group | 0.09 (0.18) | .61 | 1.09 (0.77–1.56) |

| Computer group × time | −0.25 (0.25) | .32 | 0.78 (0.48–1.27) |

| Therapist group × time | 0.01 (0.23) | .98 | 1.01 (0.63–1.59) |

| Alcohol consequences ≥2d | |||

| Time | −1.48 (0.19) | <.001 | 0.23 (0.16–0.33) |

| Computer group | −0.02 (0.19) | .94 | 0.99 (0.68–1.42) |

| Therapist group | 0.19 (0.18) | .31 | 1.21 (0.84–1.72) |

| Computer group × time | 0.16 (0.26) | .52 | 1.18 (0.71–1.95) |

| Therapist group × time | −0.06 (0.26) | .81 | 0.94 (0.56–1.57) |

CI, confidence interval.

χ2 = 1.36, P = .51.

χ2 = 0.84, P = .66.

χ2 = 1.02, P = .60.

Discussion

Previous analyses from the SafERteens study demonstrated that universal computerized screening and BIs for multiple risk behaviors (ie, violence and alcohol misuse) are feasible, well received, and effective at reducing severe peer violence outcomes up to 6 months post-ED visit among adolescents ages 14 to 18 years of age.28,29 Data presented here provide additional support that the effects of the TBI on reducing peer aggression and victimization were maintained at 12 months. Clinically, 8 at-risk adolescents would need to receive the therapist intervention in the ED to prevent 1 adolescent from experiencing severe peer aggression. In addition, 20 at-risk adolescents would need to receive the TBI to prevent 1 adolescent from experiencing peer victimization. This reduction in violence over a 1-year period may be due to the focus on increasing motivation and self-efficacy, improving skills for anger management and conflict resolution, avoiding potentially violent situations, and potential to reach goals. Also, it may be that other risk or promotive influences (eg, increased involvement with community resources because of referrals made, including positive leisure activities, psychosocial services, etc) may have been affected by the TBI that may have reduced violence over the longer term. Future research is needed to identify such potential moderators of outcome as well as to identify what factors contributed to the efficacy of the therapist intervention that were not transferred to the computer platform. It may be that key components of BI, such as empathy, are not easily transferrable to computerized platforms. Alternatively, a therapist may be able to provide more complex reflections and elicit change talk more easily than a computerized tailored intervention could accomplish. Nonetheless, given that the technology for computerized tailoring has improved substantially in the 5 years since this computer intervention was created, it may be that efficacious computer interventions for substance use and violence could be developed in the future.

A challenge for targeting multiple risk behaviors in an ED setting is balancing the need for brevity with effective coverage of the complexity of risk factors associated with alcohol misuse and violent behaviors. Potential strategies for overcoming this challenge among technology-savvy youth are the use of tailoring technology46 and use of computers.47 Although the CBI alone did not reduce peer violence at 12 months, the computer played a role in the TBI. Specifically, the assessments were self-administered on a computer, and, during the TBI, tailored content was presented on the computer for the therapist to deliver. This approach is consistent with recent recommendations for standardization of BIs to increase the likelihood of translation for busy clinical settings such as the ED.48,49 Although additional trials are needed to assess generalizability of findings to other clinical settings, this approach of computerized screening and standardizing the TBI for violence prevention has potential to be an effective platform in other EDs as well as primary care clinics. It is important to note that the peer aggression reduction noted here is in the “severe” category scale (ie, hit or punched, serious physical fighting, used a knife/gun). It is unknown whether the severity of the violence gives the BI a salience that allows for a more effective therapist intervention, or if youth with more severe violence were more motivated to change. Research is needed to look further into mediators and moderators of intervention outcomes. Regardless of the mechanism, the BI’s effect on reducing severe aggressive events lends credence to the idea that other severe risk behaviors may be amendable given a similar intervention approach. However, this supposition requires additional study.

Alcohol is a consistently observed risk factor for violence across of range of samples and study methodologies.12–14,50 Previous trials of adolescents and adults in the ED show that TBIs are effective at reducing alcohol-related injuries/consequences with time frames ranging from 3 to 12 months.25,29,51,52 In this study, however, we did not find that significant reductions in alcohol-related consequences reported previously in the TBIs and CBIs at 6 months29 were maintained at 12 months. Furthermore, our BIs did not affect alcohol consumption. This null finding may be a result of the low level of alcohol use required for study inclusion (any alcohol use, even 1 drink), with recent reviews noting that positive BI effects are typically found with greater baseline consumption levels,53 with researchers calling for additional research into consumption levels and other potential markers of positive alcohol reductions post-BI. An alternate hypothesis for the null effect on consumption is that, in this population, the primary concern of the participant during the intervention may have been their violence and not their low-level alcohol consumption (any alcohol use). In addition, although it was beyond the scope of this intervention to address other common drugs used by this urban sample, namely marijuana or other illicit drug use, future BI addressing violence should consider also addressing drug use.

Additional ED studies are needed with other samples and settings (eg, Hispanics, suburban/rural settings) to evaluate generalizability. Findings may not generalize to patient groups not included in this study (eg, acute suicidal ideation/attempt, sexual assault, presenting on overnight shifts). Although reliance on self-report is a potential limitation of this study, recent reviews suggest that the reliability and validity of self-report data are increased when privacy/confidentiality is assured, when staff are blind to condition assignment, and when participants self-administer sensitive information on computers.54–58 Finally, although attrition was low (14%) and an intent to treat analysis was conducted, it is always possible that those lost to follow-up may have biased results.

Conclusions

Data presented in this article suggest that the effects of a BI delivered by a therapist in the ED in reducing peer violence and peer victimization among adolescents are maintained 1 year later. The facilitation of the TBI by a computer to tailor content, efficiently cover multiple risk behaviors, and standardize delivery may be a promising strategy for future translation studies of BIs in the ED. To mitigate morbidity and mortality associated with youth violence, future research is needed to replicate these findings in other ED settings and to determine the best strategies for effective translation BIs for violence when delivered as part of routine clinical care.

Acknowledgments

We thank Carrie Smolenski MS LLP and Annette Solomon PsyD for their work on the project; also, we thank Linping Duan MS for statistical support. Finally, special thanks are owed to the patients and medical staff at Hurley Medical Center for their support of this project.

Glossary

- AUDIT-C

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption

- BI

brief intervention

- CBI

computer-based brief intervention

- ED

emergency department

- GEE

generalized estimating equations

- RCT

randomized control trial

- TBI

therapist-administered brief intervention

Footnotes

Drs Cunningham and Walton had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis; Drs Cunningham, Walton, and Chermack were responsible for the acquisition of data; Drs Walton, Cunningham, Chermack, Shope, Bingham, Zimmerman, and Blow conceptualized the study and are investigators on the grant funding this work; Drs Walton, Cunningham, and Chermack were responsible for the statistical analysis plan and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript; Drs Shope, Bingham, Zimmerman, and Blow provided critical feedback and revision of the manuscript; and all authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

This trial has been registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (identifier NCT00251212).

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: This project was supported by a grant 014889 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. WISQARS Leading Causes of Death Reports, 1999–2002. Available at: www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars/fatal/help/causes_icd10.htm Accessed December 21, 2005

- 2.Ellickson PL, Tucker JS, Klein DJ. Ten-year prospective study of public health problems associated with early drinking. Pediatrics. 2003;111(5 pt 1):949–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gabriel RM, Hopson T, Haskins M, Powell KE. Building relationships and resilience in the prevention of youth violence. Am J Prev Med. 1996;12(5 suppl):48–55 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jessor R, Donovan JE, Costa FM. Beyond Adolescence: Problem Behavior and Young Adult Development. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donovan JE, Jessor R, Costa FM. Syndrome of problem behavior in adolescence: a replication. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(5):762–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baumrind D. A developmental perspective on adolescent risk taking in contemporary America. In: Irwin CE, ed. Adolescent Social Behavior and Health: New Directions for Child Development. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass; 1987:93–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Irwin CE. Adolescent Social Behavior and Health: New Directions for Child Development. vol. 37 San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass; 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irwin CE, Jr, Millstein SG. Biopsychosocial correlates of risk-taking behaviors during adolescence. Can the physician intervene? J Adolesc Health Care. 1986;7(suppl 6):82S–96S [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jessor R. Problem behavior and developmental transition in adolescence. J Sch Health. 1982;52(5):295–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem Behavior and Psychological Development: A Longitudinal Study of Youth. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1977 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chermack ST, Giancola PR. The relation between alcohol and aggression: an integrated biopsychosocial conceptualization. Clin Psychol Rev. 1997;17(6):621–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenblatt JC. Patterns of Alcohol Use Among Adolescents and Associations With Emotional and Behavior Problems. Washington, DC: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brewer RD, Swahn MH. Binge drinking and violence. JAMA. 2005;294(5):616–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swahn MH, Simon TR, Hammig BJ, Guerrero JL. Alcohol-consumption behaviors and risk for physical fighting and injuries among adolescent drinkers. Addict Behav. 2004;29(5):959–963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swahn MH, Donovan JE. Correlates and predictors of violent behavior among adolescent drinkers. J Adolesc Health. 2004;34(6):480–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White HR, Bates ME, Buyske S. Adolescence-limited versus persistent delinquency: extending Moffitt’s hypothesis into adulthood. J Abnorm Psychol. 2001;110(4):600–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zucker RA, Donovan JE, Masten AS, Mattson ME, Moss HB. Early developmental processes and the continuity of risk for underage drinking and problem drinking. Pediatrics. 2008;121(suppl 4):S252–S272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernstein E, Bernstein JA, Stein JB, Saitz R. SBIRT in emergency care settings: are we ready to take it to scale? Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(11):1072–1077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pitts SR, Niska RW, Xu J. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2006 Emergency Department Summary. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng TL, Wright JL, Markakis D, Copeland-Linder N, Menvielle E. Randomized trial of a case management program for assault-injured youth: impact on service utilization and risk for reinjury. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24(3):130–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnston BD, Rivara FP, Droesch RM, Dunn C, Copass MK. Behavior change counseling in the emergency department to reduce injury risk: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2002;110(2 pt 1):267–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Posner JC, Hawkins LA, Garcia-Espana F, Durbin DR. A randomized, clinical trial of a home safety intervention based in an emergency department setting. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6):1603–1608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zun LS, Downey L, Rosen J. The effectiveness of an ED-based violence prevention program. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24(1):8–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maio RF, Shope JT, Blow FC, et al. Adolescent injury in the emergency department: opportunity for alcohol interventions? Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35(3):252–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monti PM, Colby SM, Barnett NP, et al. Brief intervention for harm reduction with alcohol-positive older adolescents in a hospital emergency department. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67(6):989–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monti PM, Barnett NP, Colby SM, et al. Motivational interviewing versus feedback only in emergency care for young adult problem drinking. Addiction. 2007;102(8):1234–1243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spirito A, Monti PM, Barnett NP, et al. A randomized clinical trial of a brief motivational intervention for alcohol-positive adolescents treated in an emergency department. J Pediatr. 2004;145(3):396–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cunningham RM, Walton MA, Goldstein A, et al. Three-month follow-up of brief computerized and therapist interventions for alcohol and violence among teens. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(11):1193–1207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walton MA, Chermack ST, Shope JT, et al. Effects of a brief intervention for reducing violence and alcohol misuse among adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304(5):527–535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris K, Florey F, Tabor J, Bearman P, Jones J, Udry J. The national longitudinal study of adolescent health: research design. 2003. Available at: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design Accessed May 21, 2008

- 31.Metzger DS, Koblin B, Turner C, et al. HIVNET Vaccine Preparedness Study Protocol Team Randomized controlled trial of audio computer-assisted self-interviewing: utility and acceptability in longitudinal studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(2):99–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murphy DA, Durako S, Muenz LR, Wilson CM. Marijuana use among HIV-positive and high-risk adolescents: a comparison of self-report through audio computer-assisted self-administered interviewing and urinalysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(9):805–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LD, Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280(5365):867–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(16):1789–1795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders identification Test (AUDIT):WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chung T, Colby SM, Barnett NP, Monti PM. Alcohol use disorders identification test: factor structure in an adolescent emergency department sample. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26(2):223–231 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rahdert ER. Problem oriented screening instrument for teenagers. In: Rahdert ER, ed. The Adolescent Assessment Referral System Manual. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse, US Department of Health and Human Services, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration ; 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knight JR, Sherritt L, Shrier LA, Harris SK, Chang G. Validity of the CRAFFT substance abuse screening test among adolescent clinic patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(6):607–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sieving RE, Beuhring T, Resnick MD, et al. Development of adolescent self-report measures from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. J Adolesc Health. 2001;28(1):73–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Straus, M.A. (1979). Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The conflict tactics scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 41(1), 75–88

- 41.Straus MA, Gelles RJ. New scoring methods for violence and new norms for the conflict tactics scale. In: Smith Ewtao C, ed. Physical Violence in American Families: Risk Factors and Adaptations to Violence in 8,145 Families. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers; 1999:529–535 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gilbert EH, Lowenstein SR, Koziol-McLain J, Barta DC, Steiner J. Chart reviews in emergency medicine research: where are the methods? Ann Emerg Med. 1996;27(3):305–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing. Preparing People to Change Addictive Behavior. New York: The Guilford Press; 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller WR, Sanchez VC. Motivating young adults for treatment and lifestyle change. In: Howard GS, Nathan PE, eds. Alcohol Use and Misuse by Young Adults. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrics. 1986;42(1):121–130 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strecher V, Wang C, Derry H, Wildenhaus K, Johnson C. Tailored interventions for multiple risk behaviors. Health Educ Res. 2002;17(5):619–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Skinner HA. Promoting Health Through Organizational Change. San Francisco, CA: Benjamin Cummings; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barry KL. Brief interventions and brief therapies for substance abuse. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 34. 1999. Available at: http://ncadi.samhsa.gov/govpubs/BKD341/ Accessed September 24, 2009

- 49.Academic ED SBIRT Research Collaborative The impact of screening, brief intervention, and referral for treatment on emergency department patients’ alcohol use. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50(6):699–710, 710.e1–e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.DuRant RH, Kahn J, Beckford PH, Woods ER. The association of weapon carrying and fighting on school property and other health risk and problem behaviors among high school students. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151(4):360–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Havard A, Shakeshaft A, Sanson-Fisher R. Systematic review and meta-analyses of strategies targeting alcohol problems in emergency departments: interventions reduce alcohol-related injuries. Addiction. 2008;103(3):368–376; discussion 377–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nilsen P, Baird J, Mello MJ, et al. A systematic review of emergency care brief alcohol interventions for injury patients. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;35(2):184–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bernstein E, Bernstein J. Effectiveness of alcohol screening and brief motivational intervention in the emergency department setting. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51(6):751–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gray TA, Wish ED. Substance Abuse Need for Treatment Among Arrestees (SANTA) in Maryland. College Park, MD: Center for Substance Abuse Research; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thornberry TP, Krohn MD. The self-report method of measuring delinquency and crime. In: Duffee D, ed. Measurement and Analysis of Crime and Justice: Criminal Justice 2000. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs; 2000:33–83 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Buchan BJ, L Dennis M, Tims FM, Diamond GS. Cannabis use: consistency and validity of self-report, on-site urine testing and laboratory testing. Addiction. 2002;97(suppl 1):98–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dennis M, Titus JC, Diamond G, et al. C. Y. T. Steering Committee The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) experiment: rationale, study design and analysis plans. Addiction. 2002;97(suppl 1):16–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brener ND, Billy JO, Grady WR. Assessment of factors affecting the validity of self-reported health-risk behavior among adolescents: evidence from the scientific literature. J Adolesc Health. 2003;33(6):436–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]