Abstract

BACKGROUND:

This report assessed the proportion of US 10th graders (average age, 16) who saw a physician in the past year and were asked and given advice about their drinking. We hypothesized that advice would vary by whether students were asked about drinking and their drinking, bingeing, and drunkenness frequency.

METHODS:

A nationally representative sample of 10th graders in 2010 (N = 2519) were asked their past 30-day frequency of drinking, bingeing, and intoxication and whether, during their last medical examination, their drinking was explored and they received advice about alcohol’s risks and reducing or stopping.

RESULTS:

In the past month, 36% reported drinking, 28% reported bingeing, and 23% reported drunkenness (11%, 5%, and 7%, respectively, 6 or more times). In the past year, 82% saw a doctor. Of that group, 54% were asked about drinking, 40% were advised about related harms, and 17% were advised to reduce or stop. Proportions seeing a doctor and asked about drinking were similar across drinking patterns. Respondents asked about drinking were more often advised to reduce or stop. Frequent drinkers, bingers, and those drunk were more often advised to reduce or stop. Nonetheless, only 25% of them received that advice from physicians. In comparison, 36% of frequent smokers, 27% of frequent marijuana users, and 42% of frequent other drug users were advised to reduce or quit those behaviors.

CONCLUSIONS:

Efforts are warranted to increase the proportion of physicians who follow professional guidelines to screen and counsel adolescents about unhealthy alcohol use and other behaviors that pose health risks.

KEY WORDS: alcohol, advice, adolescence, physician practice patterns

What’s Known on This Subject:

Evidence regarding effectively screening and counseling adolescents about unhealthy alcohol use is accumulating. Young adults aged 18 to 24, those most at risk for excess alcohol consumption, are often not asked or counseled by physicians about unhealthy alcohol use.

What This Study Adds:

In 2010 among US 10th graders (age 16), 36% drank, 28% binged, and 23% were drunk in the past month; although 82% saw a doctor, 54% were asked about drinking but only 17% were advised to reduce or stop drinking.

Among adults, strong compelling evidence supports the need for and effectiveness of screening and brief intervention for unhealthy alcohol use.1–8 Unhealthy use is a spectrum of consumption, including binge drinking, abuse, and dependence, which poses health risks.5 Proactive guidelines recommend screening and physician advice to reduce this common cause of injury and premature death.8–13 In 2004 and 2012, the US Preventive Task Force recommended screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use by adults,14,15 but indicated that evidence regarding these practices for adolescents was insufficient. Accumulating evidence not reviewed in those reports supports brief interventions for adolescents, however.16–19 The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and American Academy of Pediatrics, which recommend child and adolescent alcohol screening,13 have recently published Alcohol Screening and Brief Intervention for Youth: A Practitioner’s Guide.20

In the United States, unhealthy alcohol use is the third leading preventable cause of death, shortening 79 000 lives annually by ∼30 years, on average.21 Unhealthy alcohol use is the fifth leading cause of disability for men and 11th for women.22 Unhealthy alcohol use cost the United States $224 billion in 2006, ∼$750 per person, with most costs being borne by federal, state, and local government and persons other than the unhealthy alcohol users.21 Of those costs ($24.6 billion), 12% resulted from underage drinking.21

Among youth, alcohol is by far the most widely used substance of abuse. It is often the first tried and used by the highest percentage.23 Dangerous binge drinking is common among youth. Adolescents drink less often but more heavily on drinking days than adults. Underage drinkers average ∼6 drinks per occasion ∼9 times per month.24 Of alcohol consumed by 12- to 14-year-olds, 92% is through binge drinking.23 NIAAA defines binge drinking as an adult man consuming ≥5 drinks and a woman consuming ≥4 drinks on an empty stomach over a 2-hour period, which produces in the average adult a blood alcohol content of 0.08%, the legal level of intoxication for adults nationwide.25 Being smaller, adolescents aged 12 to 15 years reach 0.08% blood alcohol content with only 3 to 4 drinks.26

Associated with the top 3 causes of adolescent death (unintentional injuries [usually car crashes], homicides, and suicides), underage drinking annually produces nearly 5000 deaths27,28 and contributes to unprotected sex, social problems, and poor academic performance.29 Earlier age of drinking onset is independently associated with increased risk of binge drinking30 and alcohol dependence,31 the latter observed in studies controlling for genetics.32,33 Earlier drinking onset is also associated with onset of dependence at a younger age,34 and among adults, injuring oneself or others after drinking in motor vehicle crashes and other ways.35

A national survey of pediatricians and practitioners nearly a decade ago36 indicated that most do not screen adolescent patients for alcohol use, often citing lack of confidence in their alcohol management skills. Recently37 among persons aged 18 to 39 years surveyed nationwide, two-thirds saw a physician in the past year but only 14%, including those exceeding low-risk daily and weekly drinking guidelines,38 were asked and advised about risky drinking patterns. Persons aged 18 to 25 were most likely to exceed guidelines (68% vs 56%) but were least often asked about drinking (34% vs 54%). This study’s purpose is to determine what proportions of younger adolescents (10th graders) saw a physician in the past year and, of them, were asked about alcohol consumption and advised about related health risks and to reduce or stop drinking.

Methods

The NEXT Generation Health Study used a 3-stage stratified design to select a sample representative of 10th graders enrolled in public, private, and parochial high schools in the United States in 2010. School districts and groups of districts stratified across 9 US Census divisions were randomly sampled. Within districts, individual schools were randomly sampled, and within schools, 1 or more 10th-grade classes were randomly sampled. To provide adequate population estimates, African American students were oversampled. Among those provided with information about the study, only students with signed parental consent and student assent forms were enrolled. Participation was voluntary, and responses were confidential. Of recruited schools, 80 (58%) participated. Researcher-administered, in-school surveys were completed by 2524 (96.4%) of the 2619 (69%) of students providing both parental consent and assent forms in the baseline wave 1 of a 7-year longitudinal study. Of respondents (average age, 16.2 years), 55% were female, 43% were white, 34% were Hispanic, 18% were African American, 2% were American Indian/Alaskan Native, 2% were Asian, and 1% were Hawaiian/Pacific Islander individuals. Students were asked when they last had a routine checkup. Separate questions from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health39 assessed if, at their last checkup, a doctor or nurse asked whether they drink alcohol, smoke, use drugs, or exercise. Parallel questions assessed if, during that checkup, they were advised about risks associated with those behaviors and to reduce or stop drinking, smoking, or using drugs or to increase exercise.

Questions from the Monitoring the Future Study40 and frequently asked in international surveys41 included the following: In the last 30 days, how often do you drink anything alcoholic, such as beer, wine, and hard liquor? (Drinks were defined as a glass or bottle of beer, a glass of wine, a shot of liquor, or drinks mixed with liquors.) How many times did you get drunk, and have 5 or more drinks (male adolescents) or 4 or more drinks (female adolescents) on an occasion? Students were also asked about past-year frequency of marijuana and/or other drug use, past-month smoking,39 and the number of days (over the past week) they engaged in at least 60 minutes of physical activity (which gets you out of breath or sweating).42

Statistical analyses was performed by using SUDAAN software (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC) to account for weighting and cluster, and the multilevel survey design, explored the distributions of drinking, smoking, using drugs, and exercise, and whether, at their last checkup, respondents were asked about those behaviors. χ2 tests explored whether the percent of respondents who had a checkup in the past year, were asked about whether they drank alcohol, were given advice about the risk of drinking, and to reduce or stop (all yes/no) varied according to being asked about drinking and frequency of drinking, bingeing, and being drunk in the past 30 days (none, 1–5, and 6 or more times). Parallel analyses explored whether the percentages asked about smoking, use of various drugs, and exercise and given advice about health risks of substance use, lack of exercise, and to reduce or stop smoking and drug use or to exercise more frequently varied according to being asked and the frequency in which respondents engaged in those behaviors.

Then, logistic regression models assessed possible associations between whether respondents had routine checkups, were asked about drinking, were advised about the risk of drinking and to reduce or stop drinking, and the frequency of drinking, binge drinking, and being drunk, while controlling for potential confounders, including gender, race/ethnicity, family composition (mother with or without father, father only, other), how often parents encouraged not drinking, and respondents’ perception of how important not drinking was to parents. We derived adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to evaluate different levels of impact.

Results

Of respondents, 82% saw a doctor in the past year, with little variability by demographic characteristics, drinking, smoking, and drug use (Table 1). In the past month, 36% of respondents drank (11% drank 6 or more times), 28% binged (5% did so 6 or more times), and 23% were drunk (7% at least 6 times).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of 10th-Grade Students in the United States Who Saw a Doctor in the Past Year (NEXT Generation Health Study Survey, 2010)

| Sample | N | Students Who Saw a Doctor in Past Year | Significance, χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | N | |||

| Total | 2519 | 82 | 2066 | |

| Male gender | 1132 | 81 | 917 | |

| Female gender | 1387 | 83 | 1151 | NS |

| White | 1092 | 84 | 917 | |

| Hispanic | 802 | 75 | 602 | |

| African American | 456 | 85 | 388 | |

| Other | 161 | 81 | 130 | NS |

| Single parenta | ||||

| Yes | 350 | 85 | 298 | |

| No | 1597 | 82 | 1310 | NS |

| Highest parent educationa | ||||

| >High school | 205 | 69 | 141 | |

| High school | 440 | 79 | 348 | |

| Some college | 728 | 83 | 604 | |

| College+ | 525 | 86 | 452 | NS |

| Drinking in past 30 d, times | ||||

| 0 | 1733 | 81 | 1405 | |

| 1–5 | 563 | 86 | 462 | |

| 6+ | 202 | 86 | 163 | P = .03 |

| Binge drinking in past 30 d, times | ||||

| 0 | 1923 | 82 | 1566 | |

| 1–5 | 468 | 86 | 392 | |

| 6+ | 87 | 83 | 70 | NS |

| Drunk in past 30 d, times | ||||

| 0 | 2059 | 83 | 1672 | |

| 1–5 | 336 | 82 | 275 | |

| 6+ | 107 | 86 | 85 | NS |

| Smoking in past 30 d, times | ||||

| 0 | 2145 | 83 | 1739 | |

| 1–5 | 186 | 89 | 158 | |

| 6+ | 168 | 78 | 133 | NS |

| Marijuana use in past year, times | ||||

| 0 | 1912 | 83 | 1563 | |

| 1–5 | 297 | 81 | 236 | |

| 6+ | 277 | 84 | 226 | NS |

| Other drug use in past year, times | ||||

| 0 | 2265 | 82 | 1829 | |

| 1–5 | 161 | 83 | 133 | |

| 6+ | 99 | 90 | 81 | NS |

| Physical activity: How often do you exercise? | ||||

| Infrequently (≤1 time per month) | 283 | 69 | 207 | |

| 1 time per week | 299 | 74 | 232 | |

| 2–3 times per week | 717 | 86 | 584 | |

| 4 or more times per week | 1223 | 85 | 1019 | P = .001 |

NS, not significant.

Not all respondents answered these questions.

At their last examination, 54% were asked about drinking, 40% were advised about related health risks, and 17% were advised to reduce or stop drinking. Whether respondents saw a doctor in the past year, and if so, were asked about their drinking and advised about related health risks did not consistently vary according to past-month frequency of drinking, bingeing, or being drunk (Table 2). In contrast, respondents who reported drinking, bingeing, and being drunk 6 or more times per month versus never were more likely to be advised about stopping or reducing drinking (25% vs 13%, P < .01; 21% vs 13%, P < .01; and 24% vs 14%, P = .04, respectively) (Table 2). Nonetheless, of respondents advised about alcohol’s health risks but not to reduce or stop drinking, one-third reported past-month drinking, bingeing, and intoxication.

TABLE 2.

Proportions of 10th-Grade Students in the United States Asked About Alcohol and Other Substance Use at Their Last Checkup and Given Advice About Health Risks and Stopping (NEXT Generation Health Study Survey, 2010): Respondents Who Had a Checkup in the Past Year

| Variable | Prevalence | Doctor Asked | Doctor Advised About Health Risks | Doctor Advised to Stop or Reduce | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Drinking in past 30 d, times | ||||||||

| Total | 2030 | 36 | 1185 | 54 | 886 | 40 | 370 | 17 |

| 0 | 1405 | 64 | 830 | 55 | 602 | 38 | 228 | 13 |

| 1–5 | 462 | 25 | 271 | 53 | 204 | 40 | 98 | 22 |

| 6+ | 163 | 11 | 84 | 51 (NS) | 80 | 53 (NS) | 44 | 25 (P = .001) |

| Binge drinking in the past 30 d, times | ||||||||

| Total | 2018 | 28 | 1178 | 54 | 880 | 40 | 369 | 17 |

| 0 | 1556 | 72 | 934 | 56 | 680 | 39 | 258 | 13 |

| 1–5 | 392 | 23 | 210 | 51 | 171 | 44 | 91 | 26 |

| 6+ | 70 | 5 | 34 | 42 (P = .02) | 29 | 39 (NS) | 20 | 21 (P = .01) |

| Drunk in past 30 d, times | ||||||||

| Total | 2032 | 23 | 1184 | 54 | 886 | 40 | 370 | 17 |

| 0 | 1672 | 77 | 990 | 55 | 715 | 39 | 281 | 14 |

| 1–5 | 275 | 16 | 147 | 45 | 128 | 43 | 68 | 26 |

| 6+ | 85 | 7 | 47 | 60 (NS) | 43 | 52 (NS) | 21 | 24 (P = .04) |

| Smoking in past 30 d, times | ||||||||

| Total | 2030 | 19 | 1238 | 57 | 914 | 42 | 379 | 17 |

| 0 | 1739 | 81 | 1066 | 58 | 770 | 41 | 293 | 15 |

| 1–5 | 158 | 10 | 90 | 49 | 77 | 43 | 31 | 17 |

| 6+ | 133 | 9 | 82 | 58 (NS) | 67 | 46 (NS) | 55 | 36 (P = .03) |

| Marijuana use in past year, times | ||||||||

| Total | 2025 | 25 | 1204 | 55 | 890 | 40 | 353 | 16 |

| 0 | 1563 | 75 | 949 | 56 | 676 | 39 | 250 | 13 |

| 1–5 | 236 | 11 | 125 | 48 | 116 | 44 | 48 | 19 |

| 6+ | 226 | 14 | 130 | 53 (NS) | 98 | 45 (NS) | 55 | 27 (P = .02) |

| Other drug use in past year, times | ||||||||

| Total | 2043 | 13 | 1213 | 55 | 898 | 40 | 357 | 16 |

| 0 | 1829 | 87 | 1087 | 55 | 791 | 39 | 293 | 14 |

| 1–5 | 133 | 8 | 82 | 51 | 66 | 39 | 37 | 20 |

| 6+ | 81 | 5 | 44 | 56 (NS) | 41 | 54 (NS) | 27 | 42 (P = .01) |

| Physical activity: How often do you exercise? | ||||||||

| Total | 2042 | NA | 1531 | 72 | 1101 | 49 | 786 | 35 |

| Infrequently (≤1 time per month) | 207 | 8 | 143 | 66 | 114 | 53 | 99 | 43 |

| 1 time per week | 232 | 10 | 172 | 71 | 132 | 55 | 122 | 50 |

| 2–3 times per week | 584 | 27 | 436 | 74 | 339 | 56 | 254 | 41 |

| 4 or more times per week | 1019 | 55 | 780 | 72 (NS) | 516 | 46 (NS) | 311 | 28 (P = .001) |

NS, not significant.

By way of comparison, at their last examination, 72% were asked how often they exercised, with little variation between infrequent (once a month or less; 8% of the sample) and frequent exercisers (at least 4–6 times per week; 55% of the sample). Of infrequent exercisers, 43% were advised to engage in more exercise, compared with 28% of frequent exercisers (P < .001). Of respondents, 19% smoked. At their last examination, 57% were asked about smoking and 42% were advised about health risks, with no differences according to smoking frequency. Seventeen percent were advised not to smoke (36% of frequent smokers [at least 6 times monthly] versus 15% of nonsmokers [P = .03]) (Table 2).

In the past year, 25% smoked marijuana. At their last examination, 55% were asked about marijuana and other drug use, with little variation according to frequency of use of marijuana, Ecstasy, amphetamines, opiates, cocaine, glue sniffing, lysergic acid diethylamide(LSD), steroids, or other drugs (Table 2). Forty percent were advised about health risks associated with drug use, with no significant variation according to frequency of marijuana or most other drug use. Sixteen percent were given advice about reducing or stopping use, and frequent users of marijuana and other drugs (6+ times in the past year) were more likely to have been so advised (27% vs 13%; P = .02 and 42% vs 14%; P = .01).

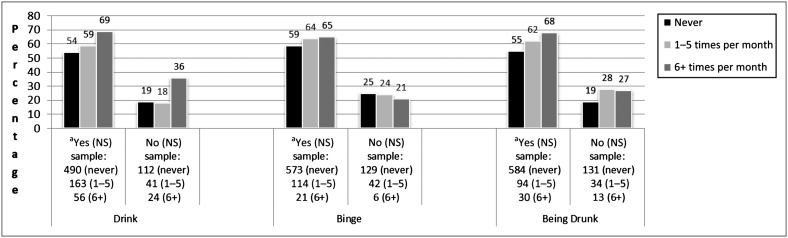

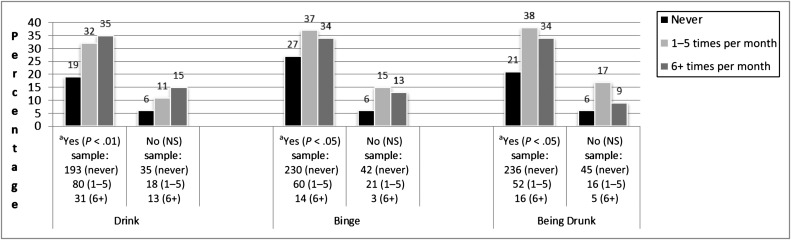

Of note, compared with those not asked, respondents asked about their drinking were more often advised about alcohol-related health risks and to reduce or stop drinking (Figs 1 and 2). Among those asked, the more frequently respondents drank, binged, or were drunk, the greater the percentage advised about the risks of drinking and to stop drinking; however, even among those asked about drinking, only approximately two-thirds of those who drank, binged, or were drunk 6 or more times in the past month were advised about drinking risks, and just more than one-third were advised to reduce or stop drinking.

FIGURE 1.

Doctor advised respondent at his or her last checkup about risk of drinking according to whether the doctor asked about drinking and past-month frequency of drinking, bingeing, and being drunk. aDoctor asked about drinking (with χ2 test across drinking frequency). NS, not significant.

FIGURE 2.

Doctor advised respondent at his or her last checkup to reduce or stop drinking according to whether the doctor asked about drinking and past-month frequency of drinking, bingeing, and being drunk. aDoctor asked about drinking (with χ2 test across drinking frequency). NS, not significant.

Respondents asked about drug use and smoking were advised more often about related health risks and to reduce or stop those behaviors (P < .01). Among those asked at their last examination about these behaviors, the more frequently respondents used drugs or smoked, the greater the percentages advised about related risks and to reduce or stop (P < .01). Among those asked and who smoked or used drugs 6 or more times in the past 30 days, two-thirds were advised about related risks and 44% and 56%, respectively, were advised to reduce or stop. Persons asked about frequency of exercising were also more often given advice about risks of no exercise and to exercise more, particularly infrequent exercisers. Among those asked, 69% who exercised once a month or less were advised about the risk of no exercise, and 57% were advised to exercise more (Tables 3 and 4).

TABLE 3.

Doctor Advised Respondent at Last Checkup About Risk of Drug Use, Smoking, and No Exercise, According to Whether the Doctor Asked About These Behaviors and Frequency of These Behaviors

| Doctor Asked About | Drug Use | Smoking | Exercise | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | N | % | Frequency | N | % | Frequency | N | % | |

| Yes | Never | 535 | 53 | Never | 630 | 56 | <1 time per month | 102 | 69 |

| 1–5 times per year | 98 | 61 | 1–5 times per 30 d | 57 | 61 | Once per week | 116 | 65 | |

| 6+ times per year | 93 | 68 | 6+ times per 30 d | 58 | 70 | 2+ times per week | 778 | 63 | |

| NSa | NSa | P < .05 | |||||||

| No | Never | 119 | 22 | Never | 140 | 21 | <1 time per month | 12 | 21 |

| 1–5 times per year | 33 | 20 | 1–5 times per 30 d | 20 | 26 | Once per week | 16 | 32 | |

| 6+ times per year | 20 | 17 | 6+ times per 30 d | 9 | 12 | 2+ times per week | 77 | 17 | |

| NSa | NSa | NSa | |||||||

NS, not significant.

χ2 test across frequency.

TABLE 4.

Doctor Advised Respondent at Last Checkup to Reduce or Quit Drug Use and Smoking and to Increase Exercise, According to Whether the Doctor Asked About These Behaviors and Frequency of These Behaviors

| Doctor Asked About | Drug Use | Smoking | Exercise | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | N | % | Frequency | N | % | Frequency | N | % | |

| Yes | Never | 198 | 19 | Never | 247 | 21 | <1 time per month | 89 | 57 |

| 1–5 times per year | 47 | 29 | 1–5 times per 30 d | 26 | 26 | Once per week | 107 | 62 | |

| 6+ times per year | 57 | 44 | 6+ times per 30 d | 47 | 56 | 2+ times per week | 512 | 42 | |

| P < .01a | P < .01a | P < .01a | |||||||

| No | Never | 41 | 6 | Never | 46 | 6 | <1 time per month | 10 | 13 |

| 1–5 times year | 7 | 6 | 1–5 times per 30 d | 5 | 8 | Once per week | 15 | 22 | |

| 6+ times per year | 7 | 7 | 6+ times per 30 d | 8 | 9 | 2+ times per week | 53 | 10 | |

| NSa | NSa | NSa | |||||||

NS, not significant.

χ2 test across frequency.

Logistic regression analyses controlling for potential confounders revealed no significantly increased odds of frequent drinkers, binge drinkers, or persons frequently drunk seeing a doctor or being asked about drinking. Persons who reported drinking at least 6 times in the past 30 days, however, had a higher odds of being advised about risks associated with drinking (OR = 1.8; 95% CI = 1.1–3.0) and to reduce or stop drinking (OR = 2.3; 95% CI = 1.2–4.2). Persons who binged 3 to 5 and 6 to 9 times in the past month were more often asked to stop or reduce drinking (OR = 2.9; 95% CI = 1.3–6.4 and OR = 2.0; 95% CI = 1.0–5.8, respectively). Persons drunk 6 or more times in the past month also had a higher odds of being asked to reduce or stop drinking (OR = 2.0; 95% CI = 1.0–4.5).

Discussion

This national survey of 10th-grade students (average age, 16.2 years) indicated a majority saw a physician in the past year but a minority were asked and given advice about drinking alcohol. At their last examination, 54% of 10th graders reported being asked about drinking, and 40% were advised about health-related risks. Only 17% were advised to reduce or stop drinking. Among frequent binge drinkers, only 21% were advised to stop or reduce. Importantly, physician advice was more often provided to more frequent substance users, drinkers, bingers, and persons frequently drunk, especially those asked about those behaviors at their last checkup, suggesting that when physicians asked about substance use they were able to identify higher-risk youth. Physicians queried just more than half of adolescent patients about drinking and other substance use, but a smaller percent of frequent-drinking patients received advice about reducing or stopping drinking than frequent users of most other substances received about curtailing use of those substances. Even among frequent drinkers, bingers, or those frequently intoxicated asked about drinking, only approximately one-quarter were advised to reduce or stop, a significantly smaller percentage than the 42% (P = .02) of frequent drug users (other than marijuana) and 36% (P = .02) of smokers asked to stop those behaviors. Nevertheless, notably physicians more often advised more frequent than less frequent drinkers.

In comparison, of those who saw a physician, more than two-thirds were asked about vigorous exercise. Also, a higher proportion of patients who rarely engaged in vigorous exercise were given advice about increasing exercise than frequent heavy drinkers were advised about reducing or stopping drinking.

Projecting from this national survey, among 16-year-olds who saw a doctor, greater numbers who drank, binged, or were drunk in the past month than who smoked or used drugs were not given physician advice to reduce or stop those respective behaviors. We project among 16-year-olds nationwide that 3 501 000 saw a physician in the past year. In the past month, of the 1 275 000 of them who drank, 981 000 who binged, and 795 000 who were drunk, 985 000, 746 000, and 594 000, respectively, were not advised to reduce or stop. In comparison, of the 666 000 who saw a doctor and smoked in the past month, 530 000 were not advised to reduce or stop. Of the 1 018 000 who saw a doctor and used any drugs (marijuana or other), 587 000 were not advised to reduce or stop.

Per clinical practice recommendations, alcohol screening should be universal. Patients with unhealthy alcohol use patterns are less likely to be detected when screening is not routine. Given the teen drinking health burden and increased likelihood of adolescent drinkers engaging in unhealthy alcohol use as adults, it is important to explore why fewer than 1 in 4 persons aged 16 who, in the past 30 days, drank, binged, or was drunk 6 or more times were advised during their last medical care visit about reducing or stopping drinking and why fewer were advised to do so than were informed about alcohol’s health risks. It is illegal in all states to sell alcohol to persons younger than age 21, and binge drinking typically produces blood alcohol levels that reach the legal level of intoxication for adults in every state.

Numerous barriers discourage alcohol screening and brief interventions among adolescents. The first impediment is a lack of knowledge about how to effectively address alcohol in brief intervention. NIAAA has developed manuals to assist physicians in alcohol in brief intervention,10,20 including a recent manual for adolescent counseling developed with the American Academy of Pediatrics.20 Second, because it is illegal to sell alcohol to persons younger than age 21, many physicians may not believe drinking needs to be explored. Yet, although smoking and other drug use are also illegal, similar proportions are queried and higher proportions advised about reducing or stopping use of other substances. Third, screening and advising patients takes time. New research indicates use of computers in screening may further adolescent screening and enhance patient satisfaction.18 Fourth, alcohol treatment services for youth may be perceived to be scarce.43 Fifth, physicians may feel uncomfortable giving advice about drinking if their own adolescence may have included alcohol use before age 21. Finally, reimbursement has been an issue in the past; however, progress has been made in recent years such that, with proper Current Procedural Terminology and International Classification of Diseases coding, it is now possible to be reimbursed for screening and brief intervention.20 See the latest American Academy of Pediatrics publication titled Coding for Pediatrics44 for up-to-date, detailed information.

Limitations of this study should be noted. First, results were derived from adolescents’ survey self-report. Some respondents who saw a physician in the past year may have been asked and advised about potentially unhealthy drinking levels but failed to recall such interaction. Respondents’ physicians did not corroborate respondents’ answers; however, even if respondents were counseled, if they could not recall being counseled, it is doubtful that their knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, behavior, and health were influenced.

Second, the survey did not specify primary care practices, the setting in which alcohol screening and counseling have shown the most beneficial results. Emergency care and specialized practitioners also have opportunities to screen. Identifying specific types of health care providers could help target future educational efforts to increase screening and advice to patients.

Third, only 10th graders were surveyed. Younger adolescents also warrant study. In summary, most 10th graders in this national survey saw a physician in the past year. Just more than half were asked about drinking, and 40% were advised about related health risks, but only 17% were given advice about reducing or stopping, and one-fourth or less of those who drank, binged, or were drunk 6 or more times in the past month were given advice about reducing or stopping. This paper reports on the first national survey to explore these issues in a sample of 10th graders aged 16. Future research needs to explore younger age groups and to identify and test whether removing barriers to screening and counseling about drinking will enable a higher percentage of physicians of patients this age to follow professional practice guidelines to routinely screen for and counsel adolescents about unhealthy alcohol use.

Glossary

- CI

confidence interval

- NIAAA

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

- OR

odds ratio

Footnotes

Dr Hingson conceptualized and designed the study, drafted the initial article, and approved the final article as submitted; Dr Zha conducted the data analysis, critically reviewed the article, and approved the final article as submitted; Dr Iannotti designed the survey questionnaire, oversaw data collection, critically reviewed and revised the article, and approved the final article as submitted; and Dr Simons-Morton conceptualized and designed the study, designed the survey questionnaire, oversaw data collection, critically reviewed and revised the article, and approved the final article as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: This project (contract number HHSN267200800009C) was supported in part by the intramural research program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; and the Maternal and Child Health Bureau of the Health Resources and Services Administration, with supplemental support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

References

- 1.Solberg LI, Maciosek MV, Edwards NM. Primary care intervention to reduce alcohol misuse—ranking its health impact and cost effectiveness. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(2):143–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaner EF, Beyer F, Dickinson HO, et al. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;Issue 2. Art. No.:CD004148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larimer ME, Cronce JM. Identification, prevention, and treatment revisited: individual-focused college drinking prevention strategies 1999-2006. Addict Behav. 2007;32(11):2439–2468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LA, Carey MP, et al. Individual-level interventions to reduce college student drinking: a meta-analytic review. Addict Behav. 2007;32(11):2469–2494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schaus JF, Sole ML, McCoy TP, et al. Screening for high-risk drinking in a college student health center: characterizing students based on quantity, frequency, and harms. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2009;Suppl 16:34–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleming MF, Balousek SL, Grossberg PM, et al. Brief physician advice for heavy drinking college students: a randomized controlled trial in college health clinics. J Stud Alcohol. 2010;71(1):23–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Babor TF, Caetano R, Casswell S, et al. Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity: Research and Public Policy. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, USA; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. 2nd ed. Alexandria, VA: International Medical Publishing; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Institute of Medicine Broadening the Base of Treatment for Alcohol Problems: Report of a Study by a Committee of the Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much: A Clinician’s Guide. Updated 2005 edition. NIH publication no. 07-3769. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Council on Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association AMA Guidelines for Physician Involvement in the Care of Substance Abusing Patients. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 1979 [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Society of Addiction Medicine Public policy statement on screening for addiction in primary care settings, 1997. Available at: www.asam.org/docs/publicy-policy-statements/1screening-for-addiction-rev-10-97.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed December 12, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Academy of Pediatrics Policy statement—alcohol use by youth and adolescents: a pediatric concern. Pediatrics. 2010;125(5):1078–1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse. Available at: www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsdrin.htm. Accessed September 24, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Jonas DE, Garbutt JC, Amick HR, et al. Behavioral counseling after screening for alcohol misuse in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [published online ahead of print September 25, 2012]. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(9):645–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jensen CD, Cushing CC, Aylward BS, et al. Effectiveness of motivational interviewing interventions for adolescent substance use behavior change: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79(4):433–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tripodi SJ, Bender K, Litschge C, et al. Interventions for reducing adolescent alcohol abuse: a meta-analytic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(1):85–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walton MA, Chermack ST, Shope JT, et al. Effects of a brief intervention for reducing violence and alcohol misuse among adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304(5):527–535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris SK, Csémy L, Sherritt L, et al. Computer-facilitated substance use screening and brief advice for teens in primary care: an international trial. Pediatrics. 2012;129(6):1072–1082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol Screening and Brief Intervention for Youth: A Practitioner’s Guide. NIH publication no. 11-7805. Bethesda, MD: Department of Health and Human Services; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bouchery EE, Harwood HJ, Sacks JJ, et al. Economic costs of excessive alcohol consumption in the U.S., 2006. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(5):516–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKenna MT, Michaud CM, Murray CJ, et al. Assessing the burden of disease in the United States using disability-adjusted life years. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(5):415–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Report to Congress on the Prevention and Reduction of Underage Drinking. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation Drinking in America: Myths, Realities, and Prevention Policy. Calverton, MD: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Alcohol development and youth: a multi-disciplinary overview. Alcohol Res Health. 2004-2005;28(3):175 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donovan JE. Estimated blood alcohol concentrations for child and adolescent drinking and their implications for screening instruments. Pediatrics. 2009;123(6). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/content/123/6/e975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention QuickStats: percentage of deaths from leading causes among teens aged 15–19 years—National Vital Statistics System, United States, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(45):1234 [Google Scholar]

- 28.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Reduce Underage Drinking. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown SA, Donovan JE, McGue MK, et al. Youth alcohol screening workgroup II: determining optimal secondary screening questions. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34(suppl 2):267A [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. J Subst Abuse. 1997;9:103–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hingson R, Heeren T, Jamanka A, et al. Age of drinking onset and unintentional injury involvement after drinking. JAMA. 2000;284(12):1524–1533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grant JD, Scherrer JF, Lynskey MT, et al. Adolescent alcohol use is a risk factor for alcohol and drug dependence: evidence from a twin design. Psychol Med. 2006;36(1):109–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agrawal A, Sartor CE, Lynskey MT, et al. Evidence for an interaction between age at first drink and genetic influences on DSM-IV alcohol dependence symptoms. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33(12):2047–2056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: age at onset, duration, and severity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(7):739–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hingson RW, Zha W. Age of drinking onset, alcohol use disorders, frequent heavy drinking, and unintentionally injuring oneself and others after drinking. Pediatrics. 2009;123(6):1477–1484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Millstein SG, Marcell AV. Screening and counseling for adolescent alcohol use among primary care physicians in the United States. Pediatrics. 2003;111(1):114–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hingson RW, Heeren T, Edwards EM, et al. Young adults at risk for excess alcohol consumption are often not asked or counseled about drinking alcohol. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(2):179–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Rethinking Drinking: Alcohol and Your Health. NIH publication no. 09-3770. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 39.University of North Carolina Carolina Population Center. Add Health: Social, Behavioral, and Biological Linkages Across the Life Course. Available at: www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth. Accessed April 24, 2012

- 40.Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, et al. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975-2008., Vol. I: Secondary School Students. NIH publication no. 09-7402. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Currie C, Nic Gabhainn S, Godeau E, et al. The Health Behaviour in School-aged Children: WHO Collaborative Cross-National (HBSC) study: origins, concept, history and development 1982-2008. Int J Public Health. 2009;54(suppl 2):131–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prochaska JJ, Sallis JF, Long B. A physical activity screening measure for use with adolescents in primary care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(5):554–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Hook S, Harris SK, Brooks T, et al. The “Six T's”: barriers to screening teens for substance abuse in primary care. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(5):456–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.American Academy of Pediatrics Coding for Pediatrics. 16th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2011 [Google Scholar]