Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate prevalence, types, and severity of potential adverse drug-drug interaction in medicine out-patient department.

Materials and Methods:

A single-point, prospective, and observational study was carried out in medicine OPD. Study began after obtaining approval Institutional Ethics Committee. Data were collected and potential drug-drug interactions (pDDIs) were identified using medscape drug interaction checker and were analyzed.

Result:

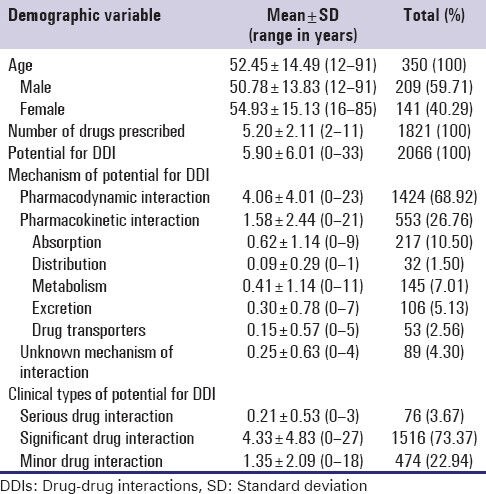

A total of 350 prescriptions with mean age 52.45 ± 14.49 years were collected over a period of 5 months. A total of 2066 pDDIs were recorded with mean of 5.90 ± 6.0. The prevalence of pDDI was 83.42%. Aspirin was most frequently prescribed drug in 185 (10.15%) out of total of 1821 drugs It was also the most frequent drug implicated in pDDI i.e. in 48.16%. The most common pDDI identified was metoprolol with aspirin in 126 (6.09%). Mechanism of interactions was pharmacokinetic in 553 (26.76%), pharmacodynamic in 1424 (68.92%) and 89 (4.30%) having an unknown mechanism. Out of all interactions, 76 (3.67%) were serious, 1516 (73.37%) significant, and 474 (22.94%) were minor interaction. Age of the patients (r = 0.327, P = 0.0001) and number of drugs prescribed (r = 0.714, P = 0.0001) are significantly correlated with drug interactions.

Conclusion:

Aspirin being the most common drug interacting. The use of electronic decision support tools, continuing education and vigilance on the part of prescribers toward drug selection may decrease the problem of pDDIs.

Keywords: Drug-drug interaction, medicine, outdoor patients, potential drug-drug interactions

Introduction

A drug interaction can be defined as an interaction between a drug and another substance that prevents the drug from performing as expected. This definition applies to interactions of drugs with other drugs (drug-drug interactions [DDIs]), as well as drugs with food (drug-food interactions) and other substances.[1]

If a country has more than 3500 drugs available for prescribing, any five of these drugs could be used in 5.2 × 1017 different combinations. Adding each drug combination increases chances of further DDI. DDIs represents a paramount and a masquerading source of medication errors. Special attention and thorough monitoring is needed for the patients who are predisposed to develop potential drug-drug interactions (pDDIs).[2]

Drug interactions can be pharmacodynamics or pharmacokinetic in nature. Pharmacodynamic interaction, involves receptor effects of different agents which interact to produce synergy or antagonism of drug effects. In pharmacokinetic interaction, the blood levels of given agents may be raised or lowered based on the type of interaction. When a therapeutic combination of drug could lead to an unexpected change in the condition of the patient, this would be described as an interaction of potential clinical significance.

Potential drug-drug interactions can be a very important ancillary factor for the occurrence of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and adverse drug events. DDIs are a subset of ADRs, accounting for about 3-5% of all ADRs, and ADRs can of course be harmful or fatal.[3] It is when the interaction leads to adverse consequences that it comes to the attention of the patient and physician. Due to this, the term “drug interaction” is frequently used incorrectly to refer to an adverse drug interaction.[4] The Boston collaborative Drug Surveillance program reported 83,200 drug exposures in almost 10,000 patients and found 3600 ADRs, of which 6.5% resulted from drug interactions.[5] These adverse DDIs have been shown to lead to increased hospitalization, increased length of hospital stay, morbidity, mortality, and increased financial costs up to U$1 billion per year to health care systems.[6] Drug factors contributing to higher rate of DDI are drugs with narrow therapeutic index, polypharmacy and sequence of drug administration. Patient related factors leading to higher DDI include age, gender, genetics, co-morbid condition, concurrent disease affecting drug clearance, and the number of physicians a patient visit can affect potential for adverse drug-drug interactions.

There are very limited numbers of DDI studies which focus on type, severity of potential for adverse drug-drug interactions so we decided to evaluate prevalence, types and severity of possible DDI in Medicine outpatient department.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional and observational study was carried out in medicine outpatient department of a tertiary teaching care hospital after obtaining ethical approval from institutional ethics committee. Study began after obtaining written informed consent from the patient. Demographic data, clinical history, and complete prescription details were recorded in case record form. Study was carried out over a period of 5 months. Only those patients included in the study whose medication profile contained at least two drugs. Drugs and formulations, which were not mentioned in the prescription were obtained from commercial publications like Indian drug review-2012[7] and CIMS online.[8] The undesirable drug interactions were identified by the online Medscape drug interaction checker.[9] This software has the appropriate sensitivity and specificity to detect possible drug interactions. DDI also checked with the help some standard text books of pharmacology.

The drug interactions were grouped into pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions. Using this drug interaction checker, the pharmacokinetic interactions were further categorized at the level of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion. The drug interactions were further categorized into serious, significant, minor (nonsignificant). Serious meant use alternative, significant meant monitor closely and minor (nonsignificant) meant continue in therapy. Potential for drug-drug interactions was analyzed for variables like age, co-morbid conditions, number of drugs prescribed, and days of hospital stay.

Statistical analysis

All the data was recorded in Microsoft excel 2010 spread sheet®. Analyses was done using SPSS version 21.0®, IBM Corporation. P < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant obtained from two-tailed tests. A bivariate analysis to identify potential factors associated with DDIs was performed using the Chi-square test. Statistically significant associations and plausible variables were included in logistic regression model using the enter method to control confounding effects. Logistic regression analysis was used to determine the adjusted odd's ratio.

Result

Demographic characteristics

A total of 350 prescriptions were included from the medicine department of a tertiary care teaching hospital with the aim to analyze potential for drug-drug interactions within prescriptions. The mean age in years was 52.45 ± 14.49. The majority of the patient in the present study belonged to age group of 51-60 years. 209 (59.71%) were females and rest were males. Most frequent co-morbid condition was hypertension 169 (48.28%), type 2-diabetes mellitus 78 (22.28%), ischemic heart disease (IHD) in 83 (23.71%) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in 6 (1.71%). Majority of the patients complained of giddiness in 38 (10.85%) and chest pain 27 (7.71%) patients.

Drugs use pattern

The total number of drug prescribed were 1821. Mean number drugs prescribed in patients is of 5.20 ± 2.11. Number of drugs prescribed was positively correlated with increasing age (Pearson correlation coefficient r = 0.351, P = 0.0001). The most frequently prescribed drug was aspirin in 185 (10.15%) followed by losartan in 159 (8.73%). Multivitamins were commonly prescribed in large number of prescriptions in 226 (12.41%) patients. The most frequently prescribed fixed dose combination was clopidogrel and aspirin in 43 (12.28%) prescriptions.

Drug interactions

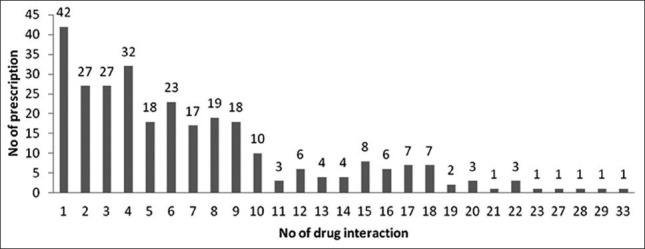

Two hundred and ninety two (83.42%) prescriptions out of 350 had the pDDIs. The total number of pDDIs was 2066 with mean number of 5.90 ± 6.01. Nature of pDDI and demographic variables are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1. Most common drug implicated in pDDIs was aspirin in 48.16%. Most common pDDI was seen with beta-blocker-metoprolol and low dose anti-platelet-aspirin 126 (6.09%). Other frequently prescribed drug pairs responsible for pDDIs were aspirin + losartan, aspirin + telmisartan and aspirin + clopidogrel.

Table 1.

Demographic variables and nature of potential for adverse DDIs (n=350)

Figure 1.

Number of drug interaction in a prescription in medicine outpatient department

Out of the total pDDI identified, 1424 (68.92%) were pharmacodynamic interactions, 553 (26.76%) were pharmacokinetic interactions and 89 (4.30%) interacted having an unknown mechanism of drug interaction.

The most frequently occurring pharmacodynamic drug interaction was that of aspirin and AT1 receptor blocker losartan in 123 (8.63%) patients. The most frequently occurring drug interaction at the level of absorption was aspirin + cyanocobalamin 52 (23.96%). As far as drug interaction at the level of distribution was concerned aspirin with second generation sulfonylureas glimepiride showed a maximum of 26 (81.25%) drug interactions. The most frequently occurring drug interaction at level of metabolism was proton pump inhibitor rabeprazole with antiplatelet clopidogrel 23 (15.86%). At the level of excretion thiazide diuretic hydrochlorothiazide with aspirin 14 (13.21%) comprised of most frequently occurring drug interaction. The most frequently occurring drug interaction at the level of p-glycoprotein was aldosterone antagonist spironolactone with HMG CoA-reductase inhibitor atorvastatin in 17 (32.07%) prescriptions. Aspirin with glimepiride was also responsible for majority of drug interactions 26 (29.21%) with unknown mechanism

The most frequently occurring serious pDDI according to the class of the drug was proton pump inhibitors + antiplatelet with 26 (34.21%) drug interactions, other most frequently noted serious drug interactions were niacin + atorvastatin, rabeprazole + digoxin and ramipril + losartan.

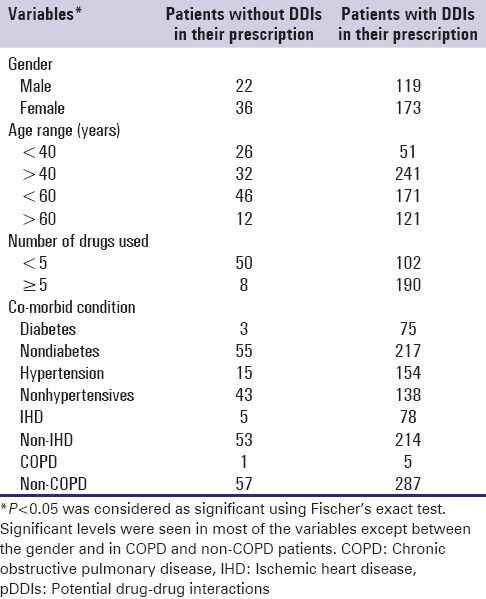

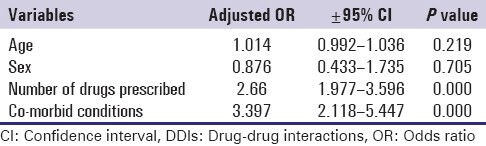

In our study, pDDIs were correlated with different variables as shown in Table 2. pDDIs were positively correlated with age (r = 0.327, P = 0.0001) and number of drugs prescribed (r = 0.714, P = 0.0001). Risk of DDIs increased significantly if patients age was >40 years (P = 0.0001), if more than five drugs were prescribed to a single patient (P = 0.0001), associated co-morbid conditions like diabetes (P = 0.0002), hypertension (P = 0.0002), and IHD (P = 0.002). Gender did not correlate with increased risk of pDDI. The factors significantly associated with having one or more PDDIs in the binary logistic regression model as shown in Table 3 includes: Co-morbid conditions (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]: 3.397, 95% confidence intervals [CI]: 2.118-5.447, P = 0.000) and increasing number of drugs prescribed (aOR: 2.66, 95% CI: 1.977-3.596, P = 0.000).

Table 2.

Different variables and pDDIs (n=350)

Table 3.

Binary logistic regression analysis for factors associated with DDIs

Discussion

Our study was aimed to analyze potential for drug-drug interaction in outpatient department of medicine unit.

In the present study, out of 350 patients enrolled, majority of the patient belonged to age group of 51–60 years, which was similar to other studies.[10,11] Most frequent co-morbid condition was hypertension, diabetes mellitus, IHD, and COPD. Mean drugs prescribed was similar to previous study.[12]

The most frequently prescribed drug to cause pDDI with other drugs was aspirin, which is attributed to its It is a known fact that aspirin is acidic in nature, extensive plasma protein binding, and its irreversible inhibition of platelets function and inhibition of the prostaglandin production.

Drug combination

The most frequently co-prescribed drug was aspirin with metoprolol. Aspirin decreases metoprolol action by blunting its anti-hypertensive effect. This could probably be due to prostaglandin inhibition resulting in reduced renal sodium excretion.[13] There is also a documented pharmacokinetic interaction between the two drugs as metoprolol may also increase peak plasma-salicylate concentrations.[14] Over and above there is increased risk of hyperkalemia when both the drugs are co-administered.[9]

Drug interactions

In our study, which included 350 patients a total of 2066 pDDI were recorded with mean of 5.90 ± 6.01. There were 292 (83.42%) prescriptions, which had at least one identifiable pDDI, which was in accordance with previous studies.[12,15]

Previous two studies on pDDIs also suggested higher number of pharmacodynamic mechanism of pDDI similar to our study. The more number of pharmacodynamics interactions are probably due to the fact that enhanced efficacy is desired in some disease conditions by the prescriber using drug combination. As rightly stated “Dramatic unintended interactions excite most, but they should not distract attention from the many intended interactions that are the basis of polytherapy e.g. multidrug treatment of tuberculosis.”[16]

Most frequent drug pairs in potential drug-drug interactions

Most common drug pair to cause pharmacodynamic interaction was identified as aspirin with losartan. Aspirin blocks the production of prostaglandins which cause vasodilation and natriuresis. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can cause fluid retention, which also affects blood pressure.[13] Due to hyperkalemia, the combination of NSAIDs and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors also can produce marked bradycardia leading to syncope, especially in the elderly More clinical data needs to be generated in this direction.

Aspirin with glimepiride was the most frequent pDDI identified at the level of distribution. This interaction could be a plasma protein displacement interaction with aspirin displacing glimepride from its binding site on albumin. Aspirin can also reduce the excretion of glimepiride predisposing to hypoglycemia this interaction at the level of renal tubular secretion. Hence glimepiride dosage (s) may require adjustment if an interaction is suspected. Patients should be apprised of the signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia.

At the level of metabolism rabeprazole with clopidogrel was the most commonly identified pDDI. PPIs inhibit CYP2C19 enzyme that could lead to therapeutic ineffectiveness of clopidogrel as enzyme is needed for its bio-activation. PPIs should be reserved only for high risk patients such as those patients on dual antiplatelet therapy, patients on anticoagulant therapy and patients with prior gastrointestinal bleeding or ulcers, weighing risk benefit ratio.

Aspirin with hydrochlorothiazide-the most common DDI at the level of excretion was hydrochlorothiazide will increase the level of aspirin by acidic drug competition for renal tubular clearance.

In our study, pDDI increased as the age advanced and this was statistically significant (P = 0.0001). This was comparable to an earlier study.[15] The possible reason of increased chances of pDDIs in increasing age is increased number of drugs as a result of associated co-morbidities. Gender was not identified as predictor of pDDIs. This is similar to the work done in previous study.[17] In our study, co-morbid conditions like diabetes, hypertension, IHD were implicated in higher chances of pDDI, hypertension is a known predictor for pDDI.[18] Number of drugs prescribed was directly correlated with pDDI and was a predictor for pDDI. As the number of prescribed drugs ascends up the potential for drug-drug interaction increases which was also suggested by work done by Doubova et al.[12] Cardiovascular drugs constituted the most common drug pairs, which was similar to earlier study.[19]

Strengths of our study were that it filled the lacunae as far as generation of local data regarding pDDIs was concerned. The study provided the baseline data, future studies of similar nature in inpatient or outpatient in different departments can be carried out. The results regarding occurrence of pDDIs in this study will be notified to the prescribers in order to sensitize them.

Though all the efforts were made to make this study very scientific and objective, it could be suffering from some of the inherent limitations. The study showed the potential for pDDIs in the prescriptions. Whether they actually occurred in the patients could not be determined because the study was a single point cross-sectional and out-patient based. However, despite the above limitations, the study clearly showed that it is possible to carry out studies on pDDIs and actual occurrence DDIs in future. National drug monitoring center and safety monitoring system is non-existing in developing countries. Continuous medical education programs, Computer based access, automated prescription alerts to doctor can be used. Also guidelines for pharmacist can be made similar to other countries.[20]

Conclusion

Our study gives a preliminary data regarding an extent of pDDIs in medicine out patient; it provides a backbone on which further studies on pDDI can be planned focusing on particular drug groups frequently identified as culprits to adverse drug interactions. Drug-disease interactions are another potential area of study. Knowledge of pDDIs could aid in developing preventive practices and policies that allow public health services to better manage this situation. Finally to conclude, the most important factor to mitigate the patients harm is the recognition by the prescriber of a potential interaction followed by appropriate action.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Drug Interactions by Pharmacist Ome Ogbru by MedicineNet.com. [Last accessed on 2013 Jul 18]. Available from: http://www.medicinenet.com/drug_interactions/article.htm#what .

- 2.Bista D, Palaian S, Shankar PR, Prabhu MM, Paudel R, Mishra P. Understanding the essentials of drug interactions: A potential need for safe and effective use of drugs. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ) 2007;5:421–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adverse Drug Reactions and Drug-Drug Interactions: Consequences and Costs-By: AMFS Pharmocology Expert. [Last accessed on 2013 Jul 18]. Available from: http://www.amfs.com/resources/medical-legal-articles-by-our-experts/350/adverse-drug-reactions-and-drug-drug-interactions-consequences-and-costs .

- 4.Carruthers S, Hoffman B, Melmon K, Nierenberg D, Melmon KL, Hoffman BB, et al. 4th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2000. Melmon and Morrelli's Clinical Pharmacology; pp. 1259–67. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Helms RA, Quan DJ, Herfindal ET. 8th ed. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2006. Textbook of Therapeutics: Drug and Disease Management; pp. 47–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lubinga SJ, Uwiduhaye E. Potential drug-drug interactions on in-patient medication prescriptions at Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital (MRRH) in western Uganda: Prevalence, clinical importance and associated factors. Afr Health Sci. 2011;11:499–507. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malik A, Malik S. 1st ed. India: Mediworld Publications; 2012. Indian Drug Review Compendium. [Google Scholar]

- 8.CIMS India. [Last accessed on 2013 Jul 18]. Available from: http://www.cimsasia.com/

- 9.Multi-Drug Interaction Checker-Medscape Reference. [Last accessed on 2013 Jul 18]. Available from: http://www.reference.medscape.com/drug-interactionchecker .

- 10.Reis AM, Cassiani SH. Prevalence of potential drug interactions in patients in an intensive care unit of a university hospital in Brazil. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2011;66:9–15. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322011000100003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cruciol-Souza JM, Thomson JC. Prevalence of potential drug-drug interactions and its associated factors in a Brazilian teaching hospital. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2006;9:427–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doubova Dubova SV, Reyes-Morales H, Torres-Arreola Ldel P, Suárez-Ortega M. Potential drug-drug and drug-disease interactions in prescriptions for ambulatory patients over 50 years of age in family medicine clinics in Mexico City. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:147. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katzung B, Masters S, Trevor A. 12th ed. USA: McGraw-Hill; Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. 36th ed. China: Pharmaceutical Press; 2009. Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aparasu R, Baer R, Aparasu A. Clinically important potential drug-drug interactions in outpatient settings. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2007;3:426–37. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennett PN, Brown MJ, Sharma P. 11th ed. Spain: Elsevier; Clinical Pharmacology. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kapp PA, Klop AC, Jenkins LS. Drug interactions in primary health care in the George subdistrict, South Africa: A cross-sectional study. S Afr Fam Pract. 2013;55:78–84. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chelkeba L, Alemseged F, Bedada W. Assessment of potential drug-drug interactions among outpatients receiving cardiovascular medications at Jimma University specialized hospital, South West Ethiopia. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol. 2013;2:144–52. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Köhler GI, Bode-Böger SM, Busse R, Hoopmann M, Welte T, Böger RH. Drug-drug interactions in medical patients: Effects of in-hospital treatment and relation to multiple drug use. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2000;38:504–13. doi: 10.5414/cpp38504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ansari J. Drug interaction and pharmacist. J Young Pharm. 2010;2:326–31. doi: 10.4103/0975-1483.66807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]