Abstract

The seed storage glycoprotein Arachis hypogea 1 (Ara h) 1 is a major allergen found in peanuts. The biochemical resistance of food proteins to protease digestion contributes to their allergenicity. The rapid proteolysis of Ara h 1 under gastric conditions challenges this model. Biophysical and in vitro digestion experiments were carried out to identify how Ara h 1 epitopes might survive digestion, despite its facile degradation. The bicupin core of Ara h 1 can be unfolded at low pH and reversibly folded at higher pH. Additionally, peptide fragments from simulated gastric digestion predominantly form non-covalent aggregates when transferred to base. Disulfide crosslinks within these aggregates occur in relatively low amounts only at early times and therefore play no role in shielding peptides from degradation. We propose that peptide fragments which survive gastric conditions form large aggregates in basic environments like the small intestine, making epitopes available for triggering an allergic response.

Keywords: Arachis hypogea 1, pH aggregation, digestion, allergy, peanut

INTRODUCTION

Food allergies are a major public health challenge, affecting six to eight percent of children under the age of four (www.niaid.nih.gov). The highest frequencies of sensitivities come from components in milk, eggs, fish, shellfish, soy, tree nuts, wheat and peanuts. Nuts, in particular, are among the leading cause of severe or fatal allergic reactions. The primary strategy for managing food allergies is avoidance, but accidental exposure is difficult to prevent. Food sensitivities are frequently caused by a specific set of proteins. Understanding how the physical and chemical properties of these proteins pertain to sensitization and elicitation of allergies is important when trying to develop effective treatments and therapies.

An unanswered question in the field of food allergy research is: why do certain proteins elicit an IgE-mediated immune response, while other proteins are tolerated? One compelling hypothesis is the existence of a link between digestability and allergenicity. Proteolysis of proteins into peptide fragments smaller than 3-5 kiloDaltons (kDa) can significantly reduce their ability to induce an immune response.1 Astwood and colleagues demonstrated that non-allergens such as spinach ribulose bis-phosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (rubisco), potato phosphofructokinase and barley β-amylase were significantly degraded in vitro in simulated gastric conditions within fifteen seconds. On the other hand, known food allergens such as soybean β-conglycinin and peanut Arachis hypogea (Ara h) 2 were stable for an hour or longer.2 However, several subsequent studies found poor or nonexistent correlations between protein digestibility and their classification as allergens or non-allergens.3-6 This hypothesis continues to be actively debated. To investigate the structural nature of allergens during digestion, we focus on a peanut vicilin – Ara h 1 (a seed storage protein) – because it is a key, immunodominant allergen recognized in over 90 % of peanut sensitive individuals.7 The vicilin proteins are primarily β-sheet proteins (Figure 1a). The β-sheets form a cup shaped six-stranded β-barrel called the cupin. The Ara h 1 monomer (62 kDa glycoprotein) consists of two tandem cupin folds (bicupin), where three bicupins assemble to form a highly stable Ara h 1 homotrimer. The oligomerization of bicupins into higher order assemblies is hypothesized to be the mechanism for stabilization with a trimerto-monomer dissociation at ~50 °C followed by full denaturation at 85 °C.8 In addition to interactions between bicupins, the homotrimer is stabilized by the coupling of small α-helical ‘handshake domains’ that pack through hydrophobic interactions.9 Deletion of these domains in a related species bean phaseolin was shown to completely disrupt trimerization.10 Many key IgE binding epitopes are found in this region, occluded by monomer-monomer contacts.11,12 Thus, oligomerization may play an important role in shielding these epitopes from proteolysis during gastric processing. Ara h 1 has been shown to form much larger oligomers which may have further implications for its allergenicity.13,14

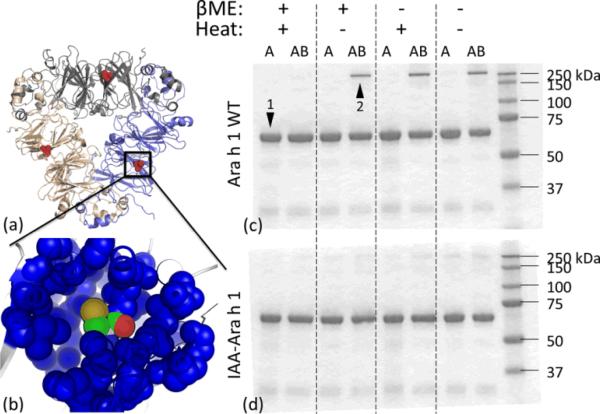

Figure 1.

(a) Ara h 1 homology model after loop remodeling and molecular dynamics minimization techniques were used to generate missing regions in the crystal structure (PDB ID 3S7I) from the Protein Data Bank.19 The homology structure has an alignment RMSD of 0.9 Å with the crystal structure. A single Cys 435 (highlighted in red) is shielded by surrounding residues in the bicupin fold as shown in (b). SDS-PAGE at conditions +/- βME and +/- heat for Ara h 1 WT (c) and IAA-Ara h 1 (d) in acidic (A) and acidic-to-basic (AB)environment. Arrows highlight monomer (band 1) and stable protein aggregate (band 2). High molecular weight species is not present in cysteine-capped Ara h 1.

In this study, we examine the in vitro aggregation behavior of Ara h 1in environments that simulate a changing acidity levels that digesting food experience in passing from the acidic stomach to the basic intestines. It has been shown in multiple studies that Ara h 1 is rapidly proteolyzed into smaller fragments in in vitro conditions simulating gastric fluid. Therfore, a mechanism where the tertiary and quaternary protein structure prevents proteolysis and preserves epitopes does not apply in the case of peanut allergy. Instead, it has been suggested that aggregation of protein fragments during digestion may preserve immunogenic components. Aggregated peptides may be protected from complete digestion in the small intestine allowing their absorption, leading to sensitization or eliciting IgE-mediated allergic reactions.15,16 Food processing conditions like dry roasting or the boiling of peanuts result in different conformational changes in Ara h 1, and both processes cause protein aggregation.8,17 As the bicupin region of Ara h 1 is purportedly more stable against heat, this leaves the α-helices and unstructured domains of the protein more prone to unfolding and aggregation.18 In relation to the digestion of Ara h 1, peptide fragments with sizes < 2 kDa can aggregate to sizes of ~ 20 kDa, and these aggregates have sensitization capacity as shown in an animal model.16 These studies by Bogh, et al., are excellent as they provide insight into the survival of short peptides from the digestion process. In our study, we clarify the conditions under which such peptide fragments can survive via their potential to form aggregates. We also demonstrate that the bicupin core of Ara h 1 is not stable at low pH, and its ensuing unfolding is likely involved in rapid digestion of the protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Purification of Ara h 1 from peanuts

Peanuts of the Tifguard variety20 was provided by the USDA-ARS Peanut Research Laboratory, Dawson, GA. Mature Ara h 1 wild type (WT) was extracted and purified using the method of Maleki11 with minor modification. In brief, defatted peanut meal was stirred in extraction buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid, 200 mM sodium chloride (NaCl), 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and 1 mM phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride; pH 8.3] overnight at 4 °C. The mixture was clarified by centrifugation and then subjected to sequential protein precipitations at 70 and 100 % ammonium sulfate. The protein was recovered by centrifugation and dialyzed against 50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.3. Ara h 1 WT was purified by elution with 300 mM NaCl in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer on an anion exchange column (2.5 × 8.5 cm; MacroPrep High Q Support, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The protein was dialyzed against 20 mM sodium phosphate pH 8 buffer and stored at -20 °C. This method produced Ara h 1 WT with a purity >95%. Ara h 1 was confirmed by mass spectroscopy at the Biological Mass Spectroscopy Facility at Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ, and by N-terminal sequencing at The University of Texas Medical Branch, Biomolecular Resource Facility, Galveston, TX.

Preparation of iodoacetic acid (IAA)-Ara h 1

Ara h 1 WT was incubated with 6 M guanidine hydrochloride (GdHCl) and 20 mM dithithreitol (final mixture pH 8) for 30 minutes at 60 °C. IAA was added to the mixture (final concentration 40 mM; pH adjusted to 8), and the solution was incubated for 30 min at room temperature (RT). The solution was serially dialyzed against GdHCl (in decreasing concentrations: 2, 1, 0.5, 0.25, 0.1 and 0 M) in 20 mM sodium phosphate pH 8. The efficiency of cysteine capping in IAA-Ara h 1 was estimated at ~98% by mass spectrometry.

In vitro partial digestion of Ara h 1 by pepsin

Ara h 1 (WT or IAA-modified) was incubated in 0.2 M hydrochloric acid (HCl)-potassium chloride (KCl) pH 2 at 4 °C for 1 hour, followed by the addition of pepsin A (Worthington Biochemical Corp., Lakewood, NJ) to give 1/200 pepsin units/μg Ara h 1. Aliquots of the mixture were inhibited with either pepstatin (3X dry weight pepsin; final pH ~2; acidic environment) or 0.2 M sodium bicarbonate (final pH ~8; acidic-to-basic environment) at time points of 0, 1, 2, 5, 10, 15 and 30 minutes.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

Digestion sample aliquots were prepared under non-reducing conditions [no β-mercaptoethanol (βME) and no heat] by mixing with equal volume of Laemelli sample buffer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). In addition, non-digested samples (t=0) were evaluated in the presence (+) or absence (-) of βME in Laemelli sample buffer and +/- heat (95 °C for 5 min). All samples were run on a precast polyacrylamide gel (Any kD™ Mini-PROTEAN TGX, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and stained with Coomassie blue (Life Technologies Corp., Grand Island, NY).

Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) of Ara h 1 digestion products

Digestion samples were separated using a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column on an AKTA FLPC system (GE Heathcare Lifesciences, Piscataway, NJ) that was equilibrated and eluted with either acidic (HCl-KCl, pH ~3) or basic (sodium phosphate, pH 8) buffer at 4 °C.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra of Ara h 1 at varying pH

Ara h 1 (WT or IAA-modified) was mixed with the following buffers for six hours minimum: pH 1–2 (0.2 M HCl-KCl), pH 3–5 (0.2 M citrate-phosphate), and pH 6–8 (0.2 M sodium phosphate). CD wavelength scans were performed on an AVIV model 420SF spectrophotometer (Aviv Biomedical, Lakewood, NJ) from 190–260 nm (single scan, 10 sec averaging) at 25 °C. Buffer blank subtraction was performed for each sample, and the molar residual ellipticity (MRE) was calculated by correcting for concentration, sequence length and cell path length. Spectral baselines were normalized at 250-260 nm where no signal was present.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Stable aggregates of Ara h 1 are formed in going from acidic to basic environment

To characterize the effect of changing acidity on Ara h 1 WT, we treated the protein with two environments: (i) pH 2 to simulate stomach acidity, and (ii) a change in acidity from pH 2 to a basicity of pH 8 to simulate solution expulsion from stomach to small intestines. The protein samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE under conditions of +/- βME and +/-heat (Figure 1c). Under reducing conditions (+βME/+heat), Ara h 1 WT is unfolded by heat and any disulfide bonds (if present) are reduced by βME. Additionally, all hydrophobic interactions in the protein are disrupted by the presence of SDS. The characteristic strong band for Ara h 1 monomer at 62 kDa is shown in the figure. The weak band at ~30 kDa is a fragment of Ara h 1 that is typically difficult to remove during purification, and all other weak bands are protein impurities. Under reducing conditions, there is no difference between the two environments of acid-only and acidic-to-basic. However, for non-reducing conditions (-βME/-heat), a relatively strong band at 250 kDa is observed for the acidic-to-basic environment. The existence of both protein bands imply that Ara h 1 WT, which is partially unfolded in acid, may form two subpopulations of aggregated species. The first – a relatively large aggregate subpopulation – is likely held together by hydrophobic interactions that can be disrupted by SDS (band at 62 kDa). The second is a smaller aggregate subpopulation that is likely crosslinked by disulfide bridges (band at 250 kDa). Further evidence for the aggregation states of the 62 and 250 kDa bands are given by SEC data (described later) and SDS-PAGE data on IAA-modified Ara h 1 (described below), respectively. N-terminal sequencing revealed that both protein bands had RSPPGE (single letter amino acid nomenclature) which is the starting sequence for mature Ara h 1. Finally, as the presence of the 250 kDa protein band at +βME/-heat and -βME/+heat is confounded we cannot determine whether heat or covalent crosslinking via Cys 435 is responsible for forming this stable aggregate.

To resolve the issue of whether the 250 kDa aggregate is due to heat or disulfide bridging, we irreversibly alkylated the sulfhydryl groups of all cysteine residues in the protein solution using IAA. The IAA-Ara h 1 was then subjected to acidic and acidic-to-basic environments. The resulting SDS-PAGE demonstrates the absence of the 250 kDa band (Figure 1d). We conclude that the stable aggregate is formed from covalent bonding between cysteine residues. Since each mature Ara h 1 monomer contains only one cysteine, protein dimerization is possible.

Ara h 1 is partially unfolded in acidic environment

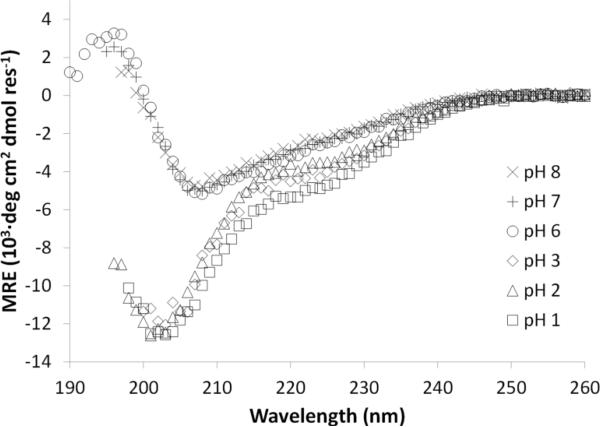

Ara h 1 WT is known to exist as a stable trimer at pH 7–8 and may remain in this conformation at pH 2 for short times.11,12 Therefore, we measured the secondary structure of Ara h 1 WT at RT under varying pH for times greater than six hours (Figure 3), and observed the following changes. At pH 6–8, the structure is similar to literature spectra of the native form, where the CD data manifest a main negative peak at 208 nm and slight negative shoulder peak at ~219 nm.8 Peak locations from our CD data were determined by multi-peak curve fitting with Igor Pro software (Wavemetrics Inc., Lake Oswego, OR). In contrast, Ara h 1 WT in an acidic environment at pH 1–3 shows partial unfolding of its secondary structure, a strong negative peak is manifest at 202 nm with a pronounced negative shoulder peak at 222 nm. These spectra are typical of proteins having a mixture of only α-helices and random coils. CD spectra deconvolution gave estimates of 33±3 % α-helix and 67±3 % random coil. The absence of β-sheet implies that acid disrupts the bicupin. No CD spectra were obtained for pH 4–5 due to protein precipitation that occurs near its isoelectric point (pI ~4.5). Interestingly, the secondary structure changes described above were different from chemical denaturation of Ara h 1 in urea, where both pH and urea unfolding of the protein were reversible (Figures S1 and S2; Supplementary Material).

Figure 3.

The native secondary structure of Ara h WT occurs at pH 6–8. Partial protein unfolding occurs in acidic environment (pH 1–3). No CD spectra were obtained for pH 4–5 due to precipitation of the protein.

We also investigated whether the secondary structure of IAA-Ara h 1 was different from the WT. The structure of the cysteine-capped protein is perturbed relative to WT as shown by overlaying the two CD spectra (Figure S3; Supplementary Material). Although the overall shapes of both curves appear similar, this does not imply that both proteins have similar bicupin and α-helical regions that would allow IAA-Arah1 to form stable trimers. Both proteins possess different retention times as measured by SEC in pH 8 buffer (no prior exposure to acid). The retention time for Ara h 1 WT homotrimer is ~16.2 min. The retention time for IAA-Ara h 1 is ~11.7 min, which indicates a much larger structure. Interestingly, this retention time is similar to aggregated Ara h 1 (compare to t=0 in Figure 4 and Figure S3 in Supplementary Material). The partial unfolding of WT and IAA-modified Ara h 1 in acid appears similar with a few notable exceptions (compare spectra in Figure 3 with Figure S4 in Supplementary Material). First, CD scans at pH 6 could not be obtained as protein precipitation prevented measurement indicating that the pI of IAA-Ara h 1 may have shifted from 4.5 to a value of 5–6. Second, peak locations were different: (i) for IAA-Ara h 1 at pH 7–8, there is a main negative peak at ~210 nm (similar to WT) and slight negative shoulder peak at ~231 nm, and (ii) for IAA-Ara h 1 at pH 1–3, there is a strong negative peak at ~203 nm (similar to WT) and a pronounced negative shoulder peak at ~241 nm. Despite these perturbations in structure, SEC measurements reveal that both proteins have similar size in acidic and acidic-to-basic environments (compare t=0 samples in Figure 4 versus Figure S5 in Supplementary Material). Any major structural differences in WT versus IAA-modified Ara h 1 may be abolished when the protein is acidified, as well as later when the solution is changed back to basic.

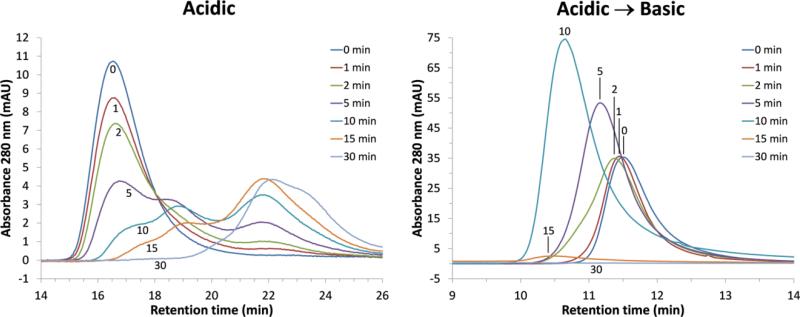

Figure 4.

Elution profiles of Ara h 1 by SEC after various digestion times followed by acidic (left) and acidic-to-basic (right) treatment. Shorter retention times indicate larger aggregate formation in going from acid to base.

Characterization of early digestion fragments of Ara h 1

The early stages of digestion of Ara h 1 (WT and IAA-modified) were examined under conditions that slowed down the rate of proteolysis. These conditions included the use of low temperature (4 °C) and a small pepsin-to-protein ratio that was not clinically relevant, but allowed a determination of how the protein was methodically digested into peptide fragments. In fact, even under these stringent conditions, Ara h 1 digestion remained relatively rapid.

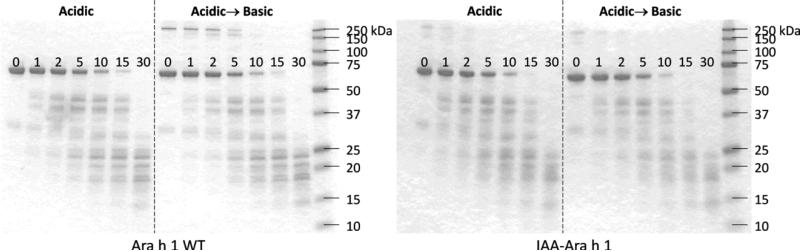

The SDS-PAGE of partially digested Ara h 1 (WT and IAA-modified) demonstrates transient accumulation of peptide fragments at the different times of digestion (Figure 2). For example, the peptide band at ~37 kDa reaches its peak intensity at 5–10 min and becomes undetectable by 30 min. There is no major difference in digestibility between WT and IAA-modified protein. However, the two observations were made: (i) in acidic-to-basic environment, cross-linked aggregates at 250 kDa appear much weaker in intensity or are absent for IAA-modified protein compared to the WT, and (ii) the rate of digestion of IAA-Ara h 1 appears somewhat faster as the 62 kDa protein bands are difficult to visualize at 15 min compared to the WT. The digestion of Ara h 1 WT after 30 min (under these slow proteolytic conditions) destroyed any ability of the protein to form stable aggregates as evidenced by the non-existence of the 250 kDa band at this time for acidic-to-basic environment. We conclude that no stable crosslinked aggregate will be formed under clinically relevant pepsin digestion.

Figure 2.

Non-reducing SDS-PAGE shows Ara h 1 dissociated into monomer (62 kDa) and the presence of larger aggregates (~250 kDa) formed in acidic-to-basic environment. Ara h 1 is digested at low pH at time points shown (in minutes), followed by pepsin inhibition with pepstatin (Acidic) or with sodium bicarbonate (Acidic→Basic). Refer to text for details.

Ara h 1 digestion fragments form aggregates in going from acidic to basic environment

One disadvantage of using SDS-PAGE to analyze digestion products is that SDS disrupts higher order structures such as aggregates. SEC was therefore used to qualitatively determine the relative sizes of protein/peptide species present during digestion in acid, as well as the relative species sizes of aggregates formed when changing from acid to base. The digestion profiles of Ara h 1 WT under these two environments are shown in Figure 4. The retention time for undigested Ara h 1 WT in acid is ~16.5 min, which is similar to the retention time of ~16.2 min for the stable homotrimer at pH 8 with no previous acid exposure. The disappearance of this peak during digestion corresponds to the appearance and growth of peptide fragment peaks at longer retention times (Figure 4; left plot). Longer retention times indicate smaller peptide fragments, but it is difficult to determine which peaks correspond to the bands observed by SDS-PAGE (Figure 2) without analyzing fractions by mass spectroscopy. In contrast, Ara h 1 WT and its digestion products aggregate when the environment is changed from acidic to basic (Figure 4; right plot). The short retention time of 11.5 min for Ara h 1 WT (t=0 min; Acidic→Basic) indicates very large structures relative to the homotrimer. In addition, the aggregate peaks shift to the left from 11.5 to 10.6 min indicating continued growth. The increase in relative peak absorbance as they shift to the left may result from a change in the absorption coefficient of the fragmented peptides. The low absorbance at times >10 min is due to very large aggregates >1300 kDa (which is the SEC column exclusion limit) becoming trapped on the column. This protein mass was washed off the column with acidic buffer indicating that the re-solubilized aggregates could be held together by non-covalent forces, such as hydrophobic interactions.

The retention times for IAA-Ara h 1 digestion products determined by SEC are similar to those of WT (Figure S5; Supplementary Material). These results support the finding that disulfide bridging does not seem to play major role in aggregating digested peptides.

Model for Ara h 1 digestion

Ara h 1 is a rapidly digestible protein yet it still has the capability to cause sensitization and IgE mediated allergic reactions in humans. We investigated the structural changes of Ara h 1 in acid and found that the purportedly stable bicupin core is readily unfolded, but can be refolded in base back to its tertiary structure with concomitant formation of soluble aggregates. This interesting behavior underlies an important observation – that partially digested peptide fragments can also aggregate in going from acid to base, forming even larger structures than intact aggregated protein. It is conceivable that the inner mass of such structures can be protected from further digestion in the small intestines.

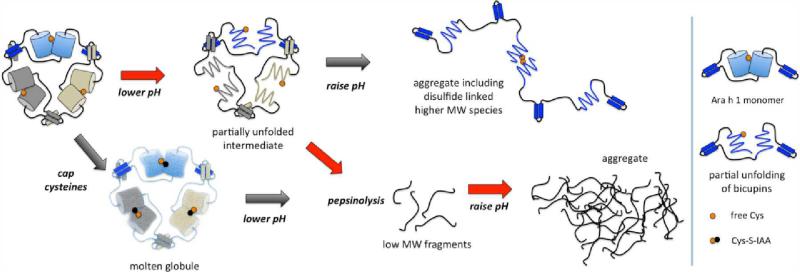

Structural insight into how peptide fragments aggregate during digestion is crucial for developing a molecular-level understanding of food allergy. These experimental studies support a model where Ara h 1 becomes partially unfolded at low pH leading to rapid pepsinolysis. Subsequent raising of the pH drives aggregation of the fragments (Figure 5). The partially unfolded state does not denature completely under acidic conditions in the absence of pepsin, and the protein can be refolded by raising the pH. In order to promote disulfide formation at low pH, it is necessary to heat the samples to drive full denaturation. The presence of partial °-helical structure at low pH suggests the helical handshake domains are kept intact under these conditions. The bicupin beta-sheet region is easily perturbed, as shown by chemical modification of Cys, which results in a molten globule–like state under neutral conditions where secondary structure is maintained, but the volume of the complex as assessed by SEC is increased.21 Preventing disulfide linked complexes from forming does not affect digestion, indicating that preventing crosslinking of this food protein is not a viable method for improving food safety, as has been found for other food-derived allergens.22

Figure 5.

Model for Ara h 1 degradation. A summary of the changes in higher order structures of Ara h 1 under conditions of changing pH, digestion, and residue modification. Red arrows indicate path modeling natural digestion.

Several questions remain unanswered including how to determine the extent of protection of these peptide fragments (i.e., what is the structure of the aggregates), how can peptides escape from the aggregate to be absorbed in Peyer's patches, and whether short sequences in Ara h 1 can be engineered to act as aggregate disrupters. We can also examine a wide range of proteins for their propensity to form aggregates from digestion products to ascertain any structural differences between allergenic and non-allergenic proteins.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr. Haiyan Zheng for assistance with mass spectroscopy analysis and Dr. Ti Wu for assistance with SEC, both at the Center for Advanced Biotechnology and Medicine at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey.

FUNDING

This work was funded by a grant from the NIH R21 AI-088627-01.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- βME

beta mercaptoethanol

- CD

circular dichroism

- Cys

cysteine

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- GdHCl

guanidine hydrochloride

- HCl

hydrochloric acid

- IAA

iodoacetic acid

- KCl

potassium chloride

- kDa

kilodaltons

- LC-MSMS

liquid chromatography tandem mass spectroscopy

- MRE

mean residual ellipicity

- NaCl

sodium chloride

- RT

room temperature

- SDS

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- SEC

size exclusion chromatography

- Tris

tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE

Unfolding of Ara h 1 WT in urea; reversibility of Ara h 1 WT in urea and in acid; characteristics of Ara h 1 (WT and IAA-modified): secondary structure by CD and estimated size by SEC; measurement of secondary structure if IAA-Ara h 1 at varying pH; measurement of IAA-Ara h 1 digestion fragments by SEC; standard protocol for LC-MSMS. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.van Beresteijn EC, Meijer RJ, Schmidt DG. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995;96:365. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(95)70056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Astwood JD, Leach JN, Fuchs RL. Nat Biotechnol. 1996;14:1269. doi: 10.1038/nbt1096-1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fu TJ, Abbott UR, Hatzos C. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:7154. doi: 10.1021/jf020599h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodman RE, Vieths S, Sampson HA, Hill D, Ebisawa M, Taylor SL, van Ree R. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:73. doi: 10.1038/nbt1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herman RA, Woolhiser MM, Ladics GS, Korjagin VA, Schafer BW, Storer NP, Green SB, Kan L. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2007;58:125. doi: 10.1080/09637480601149640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor SL. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:5183. doi: 10.1021/jf030375e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viquez OM, Konan KN, Dodo HW. Mol Immunol. 2003;40:565. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koppelman SJ, Bruijnzeel-Koomen CA, Hessing M, de Jongh HH. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:4770. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.4770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woo EJ, Dunwell JM, Goodenough PW, Marvier AC, Pickersgill RW. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:1036. doi: 10.1038/80954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ceriotti A, Pedrazzini E, Fabbrini MS, Zoppe M, Bollini R, Vitale A. Eur J Biochem. 1991;202:959. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maleki SJ, Kopper RA, Shin DS, Park CW, Compadre CM, Sampson H, Burks AW, Bannon GA. Journal of Immunology. 2000;164:5844. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.11.5844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shin DS, Compadre CM, Maleki SJ, Kopper RA, Sampson H, Huang SK, Burks AW, Bannon GA. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:13753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Boxtel EL, van Beers MM, Koppelman SJ, van den Broek LA, Gruppen H. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:7180. doi: 10.1021/jf061433+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Boxtel EL, van den Broek LA, Koppelman SJ, Vincken JP, Gruppen H. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:8772. doi: 10.1021/jf071585k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bogh KL, Barkholt V, Rigby NM, Mills EN, Madsen CB. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:2934. doi: 10.1021/jf2052306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bogh KL, Kroghsbo S, Dahl L, Rigby NM, Barkholt V, Mills EN, Madsen CB. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:1611. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blanc F, Vissers YM, Adel-Patient K, Rigby NM, Mackie AR, Gunning AP, Wellner NK, Skov PS, Przybylski-Nicaise L, Ballmer-Weber B, Zuidmeer-Jongejan L, Szepfalusi Z, Ruinemans-Koerts J, Jansen AP, Bernard H, Wal JM, Savelkoul HF, Wichers HJ, Mills EN. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2011;55:1887. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201100251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Breiteneder H, Mills EN. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:14. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chruszcz M, Maleki SJ, Majorek KA, Demas M, Bublin M, Solberg R, Hurlburt BK, Ruan SB, Mattisohn CP, Breiteneder H, Minor W. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286:39318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.270132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holbrook CC, Timper P, Culbreath AK, Kvien CK. Journal of Plant Registrations. 2008;2:92. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohgushi M, Wada A. FEBS Lett. 1983;164:21. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(83)80010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buchanan BB, Adamidi C, Lozano RM, Yee BC, Momma M, Kobrehel K, Ermel R, Frick OL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:5372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.