Abstract

Although oncomiR miR-21 is highly expressed in liver and overexpressed in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), its regulation is uncharacterized. We examined the effect of physiologically relevant nanomolar concentrations of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and DHEA sulfate (DHEA-S) on miR-21 expression in HepG2 human hepatoma cells. 10 nM DHEA and DHEA-S increase pri-miR-21 transcription in HepG2 cells. Dietary DHEA increased miR-21 in vivo in mouse liver. siRNA and inhibitor studies suggest that DHEA-S requires desulfation for activity and that DHEA-induced pri-miR-21 transcription involves metabolism to androgen and estrogen receptor (AR and ER) ligands. Activation of ERβ and AR by DHEA metabolites androst-5-ene-3,17-dione (ADIONE), androst-5-ene-3β,17β-diol (ADIOL), dihydrotestosterone (DHT), and 5α-androstane-3β,17β-diol (3β-Adiol) increased miR-21 transcription. DHEA-induced miR-21 increased cell proliferation and decreased Pdcd4 protein, a bona fide miR-21. Estradiol (E2) inhibited miR-21 expression via ERα. DHEA increased ERβ and AR recruitment to the miR-21 promoter within the VMP1/TMEM49 gene, with possible significance in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Keywords: microRNA, DHEA, HepG2 cells, estrogen receptor, androgen receptor

1. Introduction

Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), a precursor for adrenal androgen biosynthesis (Rainey and Nakamura 2008), and its sulfated form DHEA-S, are the most abundant endogenous circulating steroid hormones in humans. DHEA is commonly consumed as a nutritional supplement because of its reported anti- cancer, obesity, and aging activities at pharmacologic doses in experimental animals, although human studies do not fully support these claims and safety issues remain (Bovenberg et al., 2005; Goel and Cappola 2011; Traish et al., 2011). DHEA is metabolized to active androgens, including testosterone (T) and 5-dihydrotestosterone (DHT), in the adrenals, liver, and peripheral tissues. Androgens are metabolized to estradiol (E2) or estrone by aromatase (CYP19). Plasma DHEA-S and DHEA are highest ~ age 20 with concentrations of ~ 6 μM and 24 nM in women and 11 μM and 22 nM in men, respectively and decline to ~ 1 μM DHEA-S and 7 nM DHEA in women and 2.5 μM DHEA-S and 6 nM DHEA in men ages 60-80 (Labrie et al., 1997; Labrie et al., 2005). Over 90% of the estrogens in postmenopausal women and 30% of total androgens in men are derived from peripheral metabolism of DHEA-S (Labrie et al., 2005).

Rates of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) are 2-4 times higher in males than females (El-Serag 2011) and estrogens are considered protective in animal models (Shimizu 2003; Tejura et al., 1989), while high testosterone is considered a risk factor for HCC (Feng et al., 2011). Liver-specific ablation of androgen receptor (AR) significantly reduced the incidence of carcinogen-and HBV- induced HCC tumors in mice (Ma et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2010). The gender disparity in HCC was recently suggested to be due to loss of estrogen receptor α (ERα) expression, perhaps mediated by increased miR-22 in adjacent normal liver tissue, and upregulation of IL-1α in males compared to females (Jiang et al., 2011).

Under normal physiological conditions, the human adrenal secretes the bulk of DHEA-S (Rege et al., 2013). In the liver, DHEA and DHEA-S are interconverted, and DHEA is metabolized to active androgens, e.g., testosterone (T) and 5-dihydrotestosterone (DHT), in the adrenals, liver, and peripheral tissues. T is metabolized to E2 by aromatase (CYP19). In humans, DHEA levels peaks in the morning (Hammer et al., 2005). DHEA-S levels are reduced in patients with advanced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (Charlton et al., 2008; Tokushige et al., 2013). DHEA induces hepatocellular neoplasms in rats in a strain-, gender- , and dose-dependent manner (Mayer and Forstner 2004). Conversely, 100-200 μM DHEA induced growth arrest of HepG2 cells (Ho et al., 2008).

In addition to its metabolism to androgens and estrogens, DHEA binds cellular receptors (reviewed in (Traish et al., 2011)). DHEA binds pregnane X receptor/steroid and xenobiotic receptor (PXR/SXR, NR1I2) with a Kd ~ 50-100 μM (Webb et al., 2006), estrogen receptors α and β (ERα and ERβ) with Kd ~ 1.2 and 0.5 μM, respectively, and androgen receptor (AR) with a Kd ~ 1.1 μM (Chen et al., 2005), although higher and lower binding affinities have been reported (Supplemental Table 1). Others reported that DHEA (5 μM) activated the ligand binding domain (LBD) of ERβ but not ERα fused to the Gal4-DNA binding domain in a mammalian two hybrid-luciferase reporter assay in transiently transfected COS-1 cells (Chen et al., 2005). DHEA also binds and activates a DHEA-specific G-protein coupled receptor (GPR) in caveolae in the plasma membrane (PM) of vascular endothelial cells with a Kd ~ 49 pM leading to activation of MAPK and eNOS (Liu and Dillon 2002; Liu and Dillon 2004; Liu et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2010; Olivo et al., 2010; Simoncini et al., 2003).

Despite the considerable interest in the abundant expression of miR-21 in liver (Androsavich et al., 2012) and HCC (Connolly et al., 2010; Kawahigashi et al., 2009; Meng et al., 2007; Sun et al., 2013; White et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2012), no one has examined the effect of DHEA or its metabolites, including DHT and E2, on miR-21 or its targets in liver or HCC. In fact, there is only one report on DHEA regulation of miRNA (Paulin et al., 2011). That study showed that DHEA activated a GPR resulting in inhibition of constitutive STAT3 activation in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells which, in turn, relieved repression of miR-204 by STAT3 and increased Src (Paulin et al., 2011). In this study, we investigated DHEA regulation of miR-21 expression and DHEA regulation of a bone fide target of miR-21, i.e., Pdcd4 in HepG2 cells. Additionally, we examined how dietary DHEA affected miR-21 levels in mouse liver. Our results reveal opposite regulation of miR-21 transcription by DHEA and E2 in HepG2 cells and suggest mechanisms by which DHEA increases and E2 represses miR-21 expression through AR/ERβ and ERα, respectively.

2.Materials and Methods

2.1 Chemicals

Chemicals were purchased as follows: Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO): 17β-estradiol (E2), cycloheximide (CHX, translation inhibitor), 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT), finasteride (5α-reductase inhibitor), miconazole (general P450 inhibitor), exemestane (aromatase inhibitor), STX64 (steroid sulfatase inhibitor), 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), doxorubicin (Dox), actinomycin D (ActD, a transcriptional inhibitor), and flutamide (a selective androgen receptor modulator (SARM)); Tocris (Ellisville, MO): Fulvestrant (ICI 182, 780), 2,3-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)propionitrile (DPN), an ERβ-selective agonist; 4,4',4”-(4-Propyl-[1H]-pyrazole-1,3,5-triyl)trisphenol (PPT), an ERα-selective agonist; and 4-[2-Phenyl-5,7-bis(trifluoromethyl)pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-3-yl]phenol (PHTPP, an ERβ-selective inhibitor); Steraloids (Wilton, NH): dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), dihydrotestosterone (DHT), DHEA 3β-sulfate (DHEA-S), 5-androstene-3α,17α-diol (ADIOL), 5-androstene-3,17-dione (ADIONE), and 5α-androstane-3β,17β-diol (3β-Adiol). The SARM bicalutamide (Casodex) was generously provided by Astra Zeneca (Macclesfield, UK).

2.2. Animals and isolation of miRNA from mouse liver

Male C57BL/6 mice (10 weeks, C57BL/6NTac, Taconic Laboratories, Hudson, NY) were housed in an AAALAC-accredited facility and placed on an AIN76A diet (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN; AIN76A diet formula: http://www.harlan.com/products_and_services/research_models_and_services/laboratory_animal _diets/teklad_custom_research_diets/ain_formulas.hl) and water ad libitum for 1 week. Mice were subsequently randomized to either AIN76A diet +/− 0.45% DHEA (LabDiet, St. Louis, MO), with water ad libitum, for 7 days. Animals were monitored daily for any adverse effects of the DHEA diet and none were noted except for the phenomenon of peroxisome proliferation previously reported (Wu et al., 1989). Mice were terminated by CO2 asphyxiation and tissues removed by dissection prior to flash freezing with liquid nitrogen. All tissue samples were stored at −80 C. All manipulations were carried out in strict accordance with IACUC-approved protocols.

2.3. Cells and treatments

Human hepatocellular liver carcinoma HepG2 cells (from a male) were purchased from ATCC and were used within 9 passages. Cells were grown in DMEM (Cellgro, Manassas, VA) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C under an atmosphere of 5% CO2. Prior to ligand treatment, the medium was replaced with phenol red-free DMEM supplemented with 5% dextran-coated charcoal-stripped FBS (DCC-FBS) for 48 h (serum-starved/ serum starvation). The human bronchial epithelial cell (HBEC) HBEC2-KT cell line was originally described in (Ramirez et al. 2004). HBEC2-KT were maintained in keratinocyte-serum free medium supplemented with 2.5 μg recombinant human epidermal growth factor (EGF) and 25 mg bovine pituitary extract from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) (Ivanova et al., 2009). LY2 tamoxifen/fulvestrant-resistant human breast cancer cells were provided by Dr. Robert Clarke, Georgetown University, were used at p < 16 from this source, and were maintained as described in (Manavalan et al., 2011). MCF-7, T47D, and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells; and MCF-10A breast epithelial cells were purchased from ATCC and maintained as described (Riggs et al., 2006). H1793 human lung adenocarcinoma cells were purchased from ATCC and maintained as described (Dougherty et al., 2006). For hormone-treatment experiments, cells are routinely grown in medium + 5% DCC-FBS for 48 h (Need et al., 2012), 3 d (Madak-Erdogan et al., 2013), or 6 d (Di Leva et al., 2013) days prior to hormone treatment in order to examine transcriptional responses. Where indicated, HepG2 cells were pre-treated with 100 nM ICI 182,780, 100 nM exemestane (Brueggemeier 2002), or 5 μM miconazole (Michael Miller et al., 2013) for 6 h; 10 μM STX64 for 3 h (Foster et al., 2008); 1 μM finasteride (Sanna et al., 2004), 10 μM bicalutamide (Pinthus et al., 2007); or 10 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) (Bourdeau et al., 2008) for 1 h; before ligand treatment. Cells were treated with DMSO (vehicle control), 10 nM E2, or 10 nM DHEA, alone or after pre-treatment for 6 h.

2.4. Site-directed mutagenesis within the miR-21 promoter

To determine the sites through which ER or AR activate the miR-21 promoter, the sequence 5000 bp upstream from the transcriptional start site of miR-21 was searched using the online tool ALGGEN (http://alggen.lsi.upc.edu/) and two new putative AR binding sites (androgen response elements, ARE) were identified at positions 117470-117478 (ARE2) and 117524-117532 (ARE3) (NCBI accession # AC004686). The miR-21 promoter contains several transcriptional start sites (Ribas and Lupold 2010; Ribas et al., 2009; Terao et al., 2011), so to avoid ambiguity, we used the translational start site as the reference position (+1). Thus, the putative AREs were at −3,703 (ARE1, reported by (Ribas et al., 2009)), −3,528 (ARE2), and −3,474 (ARE3) upstream from the translational start site (Fig. 4A). For the experiments examining the ability of DHEA and E2 to regulate miR-21 promoter activity, a luciferase reporter containing 1.5 kB of the human MIR21 promoter in the pGL3-basic vector (Promega) and a mutant within the estrogen response element (ERE)/retinoic acid response element (RARE) were generously provided by Dr. Enrico Garattini, di Ricerche Farmacologiche, “Mario Negri”, Italy (Terao et al., 2011). To generate mutants of each ARE, oligonucleotide primers AREMut1, AREMut2 and AREMut3 were designed to specifically disrupt putative AREs at each of these positions (Supplemental Table 2). Each mutation introduced a new PvuI restriction site to aid in identification of recombinant plasmids and to mutate the 3 putative AREs. Geneart® Site-Directed Mutagenesis System (#A13282, Invitrogen) was used in conjunction with specific primers (Supplemental Table 2) to introduce ARE mutations in the pGL3-MIR21 promoter construct according to the manufacturer's instructions. After mutant strand synthesis (using T4 DNA polymerase) and ligation, resultant plasmids were introduced into E. coli and transformants were selected using ampicillin resistance. Further restriction endonuclease PvuI (NEB#R0150S) analysis was performed to screen clones and the DNA sequence of all mutants was confirmed by sequencing.

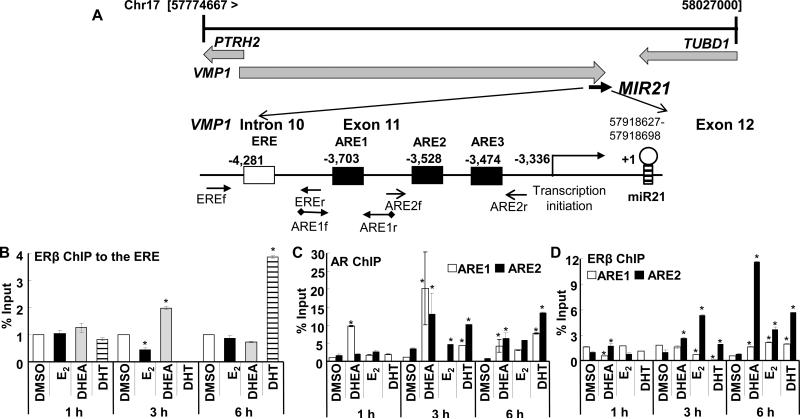

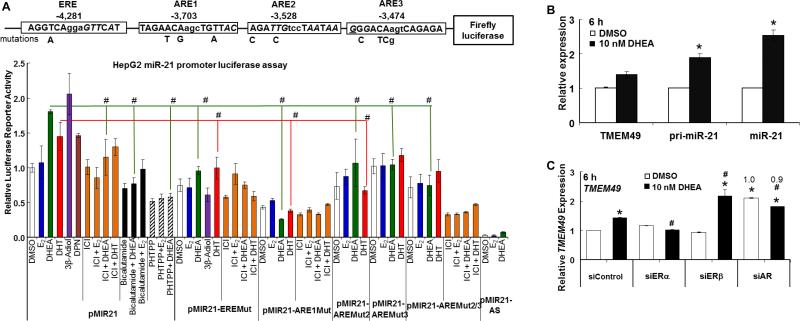

Fig. 4. DHEA increases AR and ERβ recruitment to the miR-21 promoter.

A, The diagram at the top shows the chromosomal location of the pri-miR-21 promoter within the VMP2/TMEM49 gene http://atlasgeneticsoncology.org/Genes/MIRN21ID44019ch17q23.html. The location and sequences of the ERE and AREs and the primers used for ChIP are indicated. Sequences of the ERE and AREs are in Fig. 6A. For B, C, and D, HepG2 cells were ‘serum-starved’ for 48 h and then treated with DMSO, 10 nM E2, 10 nM DHEA, or 10 nM DHT for 1, 3, or 6 h. ChIP was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Values are fold enrichment of the PCR product in the immunoprecipitated samples relative to input control. Values for ChIP of ERβ to the ERE (B) are from 4 separate experiments. Values for ChIP of ERβ and AR to the AREs (C and D) are from 2 separate experiments. Within each experiment, 3 replicates were run for each sample. *P < 0.05 versus DMSO.

2.5. Transient transfection and luciferase reporter assay

HepG2 cells were plated in 24-well plates at a density of 1.5×104 cells/well in antibiotic free DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS. Transient transfection was performed using FuGENE HD Transfection Reagent (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) with Opti-MEM® Reduced Serum Medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). For the indicated experiments examining miR-21 direct effects on PDCD4 translation/message stability, HepG2 cells were transfected with 100 ng of pGL3-pro luciferase reporter (Promega, Madison, WI) as a control and 10 ng of pRL-TK-Renilla luciferase reporter (Promega) containing the 3’-UTR of the PDCD4 gene (Wickramasinghe et al., 2009). Twenty-four hours after transfection, triplicate wells were starved with phenol red-free DMEM supplemented with 5% DCC-FBS for 24 h, then treated with DMSO (vehicle control), E2, or DHEA as indicated in the Fig. legend. For the experiments examining the ability of DHEA and E2 to regulate miR-21 promoter activity, a luciferase reporter containing 1.5 kB of the human MIR21 promoter in the pGL3-basic vector (Promega) and a mutant within the ERE/retinoic acid response element (RARE) were generously provided by Dr. Enrico Garattini, di Ricerche Farmacologiche, “Mario Negri”, Italy (Terao et al., 2011). Insertion of the nucleotide changes within ARE2, ARE3, and ARE2/ARE3, as well as the sequence of the MIR21-EREmut vector (Terao et al., 2011), were verified by DNA sequencing. Cells were transfected with 250 ng MIR21-promoter-FF-luciferase and 5 ng pGL4.74[hRluc/TK] vector (Promega) . For all reporter assays, the cells were harvested 24 h post-treatment using Passive Lysis buffer (Promega). Luciferase and Renilla luciferase activities were determined using a Dual Luciferase assay (Promega). For the Renilla-3’UTR assay, Renilla luciferase was normalized by firefly luciferase to correct for transfection efficiency. For the MIR21 promoter-firefly luciferase assay, firefly luciferase was normalized by Renilla luciferase. Relative expression (fold change) was determined by dividing the averaged normalized values from each treatment by the DMSO value for each transfection condition within that experiment. Values were averaged as indicated in the Fig. legends.

2.6. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR) analysis of miRNA and mRNA expression

Total RNA was isolated from HepG2 cells with the miRCURY™ RNA isolation Kit (Exiqon, Vedbaek, Denmark) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Mouse liver RNA was isolated using the Exiqon miRCURY tissue RNA isolation kit following the manufacturer's protocol. The quality and quantity of the isolated RNA was analyzed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer and Agilent Bioanalyzer. Quantification of miR-21 was performed using miRCURY LNA™ Universal RT microRNA PCR Kit (Exiqon) and SYBR Green master mix (Exiqon). RNU48 and 5S RNA were used for normalization of miRNA expression from cultured cells. For the mouse liver, 18S was used for normalization. For analysis of PDCD4, ESR1 (ERα), ESR2 (ERβ), primary miR-21 (pri-miR-21), and TMEM49/VMP1 mRNA expression, 1 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed by the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Inc., (ABI), Carlsbad, CA) and quantitation was performed using TaqMan primers and probes sets with Taqman Gene Expression Master Mix (ABI) and 18S was used for normalization. qPCR was run using either an ABI 7900HT Fast Real-Time or ViiA7 Real-time PCR Systems (Applied Biosystems) with each reaction run in triplicate. Analysis and fold change were determined using the comparative threshold cycle (Ct) method. The change in miRNA or mRNA expression was calculated as fold-change, i.e., relative to DMSO-treated (control).

2.7. RNA interference

HepG2 cells were grown to 70% confluency in six-well plates in DMEM supplemented with 5% DCC-FBS. Small interfering RNA (siRNA, Silencer Select) specific for ERα, ERβ, and AR were purchased from Ambion (Austin, TX). As a control, cells were transfected with negative control siRNA (Silencer Select Negative Control No. 1 from Ambion). Cells were transfected with 90 pmoles siRNA/well using 7 μl of RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) in antibiotic-free medium and incubated for 48 h. Cells were subsequently treated with DMSO (vehicle control), 10 nM DHEA, 10 nM E2, or 10 nM DHT for 6 h. RNA and protein lysates were prepared for qPCR and Western blot analysis.

2.8. Western blotting

Cells were treated as indicated in individual Fig. legends and whole cell extracts (WCE) were prepared in modified RIPA buffer (Sigma) with addition of protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche). Western analysis was performed and quantitated as described (Riggs et al., 2006). Proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA). Dual color precision protein MW markers (BioRad) were separated in parallel. Antibodies were purchased as follows: ERα (D-12, sc-8005), ERβ (sc-53494), Pdcd4 (sc-130545), from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); AR (#3202) from Cell Signaling Technology; β-actin from Sigma; and α-tubulin (MS-581-P1) from Thermo Scientific/Lab Vision (Fremont, CA). Chemiluminescent bands were visualized on a Carestream Imager using Carestream Molecular Imaging software (New Haven, CT).

2.9. Transfection of Anti-miR™ miRNA inhibitors and Pre-miR™ miRNA precursor

HepG2 cells were transfected with Anti-miR™ miR-21 inhibitor for hsa-miR-21, Anti-miR™ miRNA inhibitor negative control, Pre-miR™ miR-21 precursor, and Pre-miR™ miRNA negative control (Ambion, Austin, TX) using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, the medium was replaced with phenol red-free DMEM with 5% DCC-FBS for 48 h and the cells were treated with DMSO vehicle control, 10 nM E2, or 10 nM DHEA for 24 h. Total RNA was isolated using miRCURY™ RNA isolation Kit (Exiqon) for qPCR analysis, as above. WCE were prepared for western blot analysis, as above. Each experiment was repeated for a total of three biological replicates. Western blots were quantified as above and the ratio of each protein/α-tubulin in the negative control in DMSO-treated samples was determined.

2.10. MTT assays

MTT cell viability assays were performed using CellTiter96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay from Promega. Briefly, 1 × 103 HepG2 cells were plated per well in 96-well plates. Cells were treated with DMSO (vehicle control) or the compounds indicated in the Fig. legends for 48 h- 5 d, depending on the experiment. Absorbance was measured at 490 nm using a 96-well plate reader SpectraMax M2 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Each treatment was performed in quadruplicate within each experiment.

2.11. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

HepG2 cells were serum-starved for 48 h, as above, and then treated for 1, 3, or 6 h with DMSO (vehicle control), 10 nM E2, 10 nM DHEA, or 10 nM DHT before crosslinking with 1% formaldehyde for 5 min. ChIP was performed using MAGnify ChIP (Invitrogen). Lysates were incubated with anti-AR (N-20, sc-816, Santa Cruz), anti-ERα (HC-20, sc-543, Santa Cruz), anti-ERβ (HC-150, sc-8974, Santa Cruz), or mouse IgG (Invitrogen). Immunoprecipitated DNA was amplified by quantitative PCR using the following primers for the miR-21 promoter : ERE1-F: 5’-CCAGAAGTTAGGGATATGTTAGCA-3’; ERE1-R: 5’-TACCTCCAGGGTTCAAGTGATTCT-3’; ChIP negative controls (12,038 at 3’ end of VMP1/TMEM49): Neg-F: 5’-ATTGGCTATCTTTGTGTGCCTTG-3’; Neg-R: 5’-TGCTCAATAAAACACATTGTTCTTCAT-3’; ARE-1F: 5’-TCCCAATCATCTCAGAACAAGCT-3; ARE-1R: 5’-TGCACAGAAACTCCAGTACATTAGTAAC-3’; ARE-2F 5’-GGATGACGCACAGATTGTCCTA-3’; ARE-2R: 5’-AAAGAAACTGCCCGCCCTCT-3’. Each ChIP was performed in triplicate, and each PCR was amplified in triplicate. Quantitation was performed as described in (Mattingly et al., 2008). For IP of ERα, ERβ, and AR with IgG, CT was “undetermined”; for ERβ with ERE1 in DHEA- and E2- treated cells (3 h), CT values were 32.1 ± 0.51 and 34.2 ± 0.51, respectively.

2.12. Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using Student's t-test in Excel or one-way ANOVA followed by Dunn's multiple comparison test using GraphPad Prism (San Diego, CA).

3. RESULTS

3.1. DHEA increases miR-21 expression

DHEA and its sulfated form DHEA-S are abundant steroid hormones that are metabolized in liver and other tissues (Labrie et al., 2005; Traish et al., 2011; Webb et al., 2006). miR-21 is one of the ten most abundant miRNAs in human and mouse liver (34), but its regulation in liver is uncharacterized. To determine if DHEA regulates miR-21 expression, HepG2 cells were ‘serum-starved’, i.e., treated with phenol-red free DMEM + 5% DCC-stripped FBS, for 48 h to reduce basal hormone-related activities (Madak-Erdogan et al., 2013)and then treated with 0.1-1000 nM DHEA or DHEA-S or 1-100 nM E2 for 6 h. Both DHEA and DHEA-S increased, whereas E2 inhibited, miR-21 expression in a concentration-dependent manner in HepG2 cells (Fig. 1A). DHEA also increased miR-21 expression in HBEC2-KT human bronchial epithelial cells, H1793 human lung adenocarcinoma cells; MCF-7, T47D, and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, but not LY2 endocrine-resistant breast cancer cells or MCF-10A breast epithelial cells (Supplemental Fig. 1). These data suggest that the increase in miR-21 by DHEA is cell line-specific. To examine the mechanism for DHEA-induced miR-21, we focused on HepG2 cells.

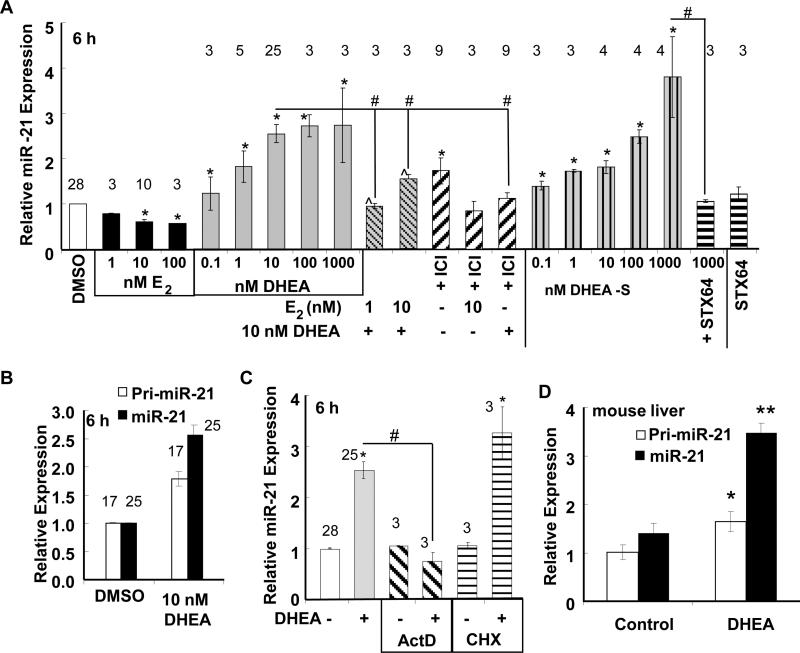

Fig. 1. DHEA increases miR-21 expression in HepG2 cells.

A, B, and C, HepG2 cells were ‘serum-starved’ for 48 h prior to treatment as indicated for 6 h. Where indicated in A and C cells were pre-incubated with inhibitors: 100 nM ICI 182,780 (ICI), 10 μg/ml actinomycin D (ActD), 10 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) prior to 6 h treatment with 10 nM DHEA. B, Pri-miR-21 was normalized to 18S. For A, B, and C, qPCR was used to examine miR-21 expression relative to RNU48 and calculated as fold-change normalized to DMSO-treated cells (vehicle control). Values are the average of the number of separate experiments given by the numerical values over the bars ± SEM. Within each experiment, each sample was run in triplicate. * p < 0.05 versus DMSO vehicle; # p < 0.05 versus 10 nM DHEA. D, Male C57BL/6 mice were fed AIN76A diet +/− 0.45% DHEA for 1 week. Pri-miR-21 and miR-21 are expressed relative to 18S. Vales are the mean ± SEM of 2 control and 4 DHEA-treated mice, respectively. With each sample run in 2 independent experiments. * p < 0.05 control versus DMSO; ** p < 0.005 control versus DMSO.

DHEA increased both the primary miR-21 transcript (pri-miR-21) as well as mature miR-21 (Fig. 1B). DHEA-S-induced miR-21 expression was blocked by STX64, an inhibitor of steroid sulfatase (Foster et al., 2008), suggesting that DHEA-S requires de-sulfation to increase miR-21 expression (Fig. 1A). The dose-dependent inhibition of miR-21 by E2 was similar to findings reported by us and others in MCF-7 breast cancer cells (Klinge 2012; Maillot et al., 2009; Wickramasinghe et al., 2009). E2 suppressed DHEA-induced miR-21 transcript expression. The ER antagonist fulvestrant (ICI 182,780, ICI) reduced miR-21 induction by DHEA, and reduced the inhibition of miR-21 by E2 (Fig. 1A), suggesting ER involvement in both DHEA and E2 responses. Fulvestrant alone increased miR-21 expression, an effect possibly mediated by GPER in HepG2 cells (Ikeda et al., 2012; Santolla et al., 2012). HepG2 cells express ERα and ERβ(Solakidi et al., 2005) (Supplemental Fig. 2A) and we observed that serum starvation (increased ERα and AR, but not ERβ, proteins (Supplemental Fig. 2A and 2B). Serum starvation did not affect basal pri-miR-21 or miR-21 transcript levels (Supplemental Fig. 3).

3.2. DHEA increases miR-21 transcription

DHEA-induced miR-21 expression was inhibited by transcriptional inhibitor actinomycin D, but not by protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide, suggesting a primary transcriptional response (Fig. 1C).

3.3. Dietary DHEA increases miR-21 in mouse liver

To determine if DHEA increases miR-21 in liver in vivo, male C57Bl/6 mice were fed an AIN76A diet +/− 0.45% DHEA for 1 wk. Dietary DHEA significantly increased both pri-miR-21 and miR-21 transcript levels in mouse liver after 7 days (Fig. 1D).

3.4. DHEA inhibition of Pdcd4 expression is mediated by miR-21

Programmed Cell Death 4 (Pdcd4/PDCD4) is a bona fide target of miR-21 (Lu et al., 2008; Wickramasinghe et al., 2009). We examined if the induction of miR-21 by DHEA in HepG2 cells would result in a decrease in PDCD4 expression. DHEA reduced and E2 increased Pdcd4 protein (Fig. 2A) and mRNA expression (Fig. 2B) in concordance with miR-21 stimulation and inhibition, respectively. To determine if DHEA regulation of Pdcd4 protein expression is mediated by the miR-21 seed element in the 3’UTR of the PDCD4 transcript, HepG2 cells were transiently transfected with a Renilla luciferase reporter with the PDCD4 3’-UTR cloned downstream of Renilla and the cells were co-transfected with the pGL3-pro firefly Luciferase reporter for normalization. E2 increased and DHEA inhibited Renilla luciferase from the PDCD4-full length 3’UTR reporter (Fig. 2C). Co-transfection with antisense-miR-21 (AS-miR-21) increased basal luciferase from the Renilla reporter and ablated the inhibition by DHEA and the induction by E2. Knockdown of miR-21 expression was confirmed (Supplemental Fig. 4). These results agree with the increase in miR-21 expression by DHEA and down-regulation of miR-21 by E2 in HepG2 cells (Fig. 1A) after 6 h and indicate that the reduction of Pdcd4 protein levels by DHEA (Fig. 2A) is mediated by the increase in miR-21.

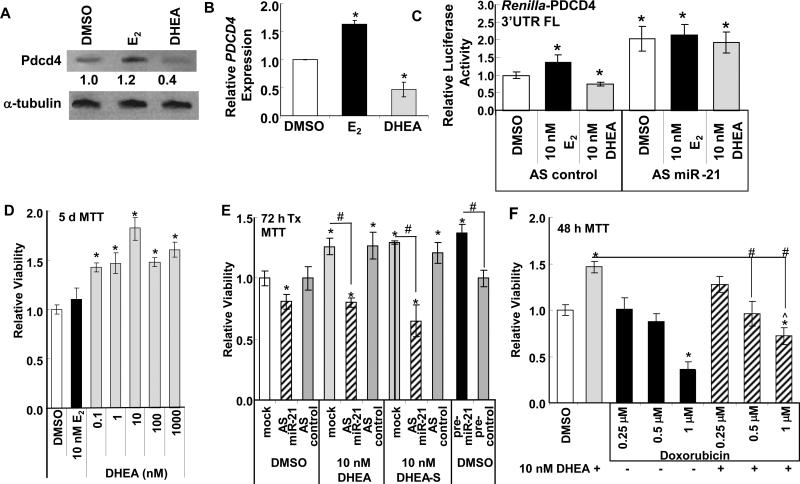

Fig. 2. DHEA reduces miR-21 target PDCD4 expression and increases cell viability.

A and B, HepG2 cells were ‘serum-starved’ for 48 h and treated with DMSO, 10 nM E2, or 10 nM DHEA for 24 h (A) or 6 h (B). Whole cell lysates (20 μg protein) were immunoblotted for Pdcd4 protein. The membrane was stripped and re-probed with α-tubulin for normalization. Values are Pdcd4/α-tubulin normalized to DMSO. B, qPCR for PDCD4 relative to 18S rRNA. Values are the mean ± SEM of 3 separate experiments. * p < 0.01 versus DMSO control. C, HepG2 cells were transiently transfected with pGL3-pro-luciferase and pRenilla-Luciferase-TK containing the full length (FL) 3’UTR of the PDCD4 gene cloned in the 3’UTR as described in (31). Cells were serum-starved for 48 h and treated with DMSO, 10 nM E2, or 10 nM DHEA for 24 h. Renilla luciferase was normalized by firefly luciferase to correct for transfection efficiency. Relative luciferase activity was determined by dividing the averaged normalized values from each treatment by the DMSO value for each transfection condition within that experiment. * p < 0.05 versus DMSO AS control.. D, HepG2 cells were ‘serum-starved’ for 48 h prior to addition of the indicated concentrations of E2 or DHEA for 5 days. E, HepG2 cells were transfected with anti-sense (AS) control or AS-miR-21 for 24 h prior to serum starvation (48 h) and then 72 h treatment as indicated. * p < 0.05 versus DMSO control; # p < 0.05 from identical treatment without inhibitor, AS, or pre-miR-21, as indicated. F, HepG2 cells were treated with DMSO, PBS, E2, or DHEA alone or with the addition of the indicated concentrations of doxorubicin for 48 h. * p < 0.05 versus DMSO or PBS control; # p < 0.05 from identical treatment (DHEA or E2) without doxorubicin, as indicated. For panels B, C, D, E, and F, values are the average of 3 separate MTT assays ± SEM.

3.5. DHEA increases HepG2 viability

Transfection of HepG2 and other HCC cell lines with precursor miR-21 increased cell proliferation and transfection with antisense miR-21 reduced cell proliferation (Meng et al., 2007). Since DHEA and its metabolites increased endogenous miR-21 in HepG2 cells, we hypothesized that DHEA would stimulate HepG2 cell proliferation. Although pharmacological doses of DHEA (1-200 μM) were reported to inhibit HepG2 viability and induce apoptosis (Jiang et al., 2005), we observed that physiological levels of DHEA increased HepG2 viability (Fig. 2D). To determine if the increase in cell viability was mediated by the DHEA-induced increase in miR-21, HepG2 cells were transfected with anti-sense (AS) control or anti-miR-21 inhibitor for 24 h prior to serum starvation (48 h) and then treated for 72 h (Fig. 2E). Knockdown of miR-21 was confirmed by qPCR (Supplemental Fig. 4). AS-miR-21 inhibited basal HepG2 viability (Fig. 2E). Conversely, transfection of HepG2 cells with pre-miR-21 increased cell viability (Fig. 2E). Supplemental Fig. 4 shows that HepG2 cells transfected with pri-miR-21 showed increased miR-21 expression at the time of the MTT assay. The DHEA- and DHEA-S- induced increase in HepG2 viability was inhibited by AS-miR-21 (Fig. 2E), suggesting that DHEA-stimulated miR-21 expression plays a role in DHEA-induced cell viability.

Doxorubicin is routinely and widely used to treat HCC (Abou-Alfa et al., 2010). Transfection of HepG2 cells with pre-miR-21 resulted in chemoresistance to IFNα and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) (Tomimaru et al., 2010). We examined if treatment of HepG2 cells with DHEA affects the sensitivity of HepG2 cells to doxorubicin. Doxorubicin reduced HepG2 cell viability in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2F). DHEA reduced the 1 μM doxorubicin inhibition by ~ 50 %, suggesting that DHEA induced partial doxorubicin resistance.

3.6. Knockdown of ERβ and AR ablates DHEA-induced pri-miR-21 expression

The ER antagonist fulvestrant inhibited the reduction in miR-21 by E2 and the increase in miR-21 by DHEA (ICI, Fig. 1A). DHEA is converted to AR ligands (Granata et al., 2009; Green et al., 2012; Mo et al., 2006; Provost et al., 2000; Rege and Rainey 2012; Rijk et al., 2012; Vollmer et al., 2012), directly activates AR in mouse brain and recombinant AR in vitro (Lu et al., 2003), and directly activates mutant ARs in prostate cancer (Mizokami et al., 2004; Tan et al., 1997). Thus, we evaluated the roles of ERα, ERβ, and AR in regulating pri-miR-21 and mature miR-21 expression in HepG2 cells. HepG2 cells were transfected with siControl, siERα, siERβ, or siAR for a total of 72 h with serum starvation during the final 48 h (to reduce endogenous ligand activation of these receptors). The cells were treated with DMSO, 10 nM E2, 10 nM DHEA, or 10 nM DHT for 6 h. siERα reduced ERα protein ~ 40-60%, siERβ reduced ERβ protein ~ 30-40%, and siAR reduced AR protein ~ 90% (Fig. 3A).

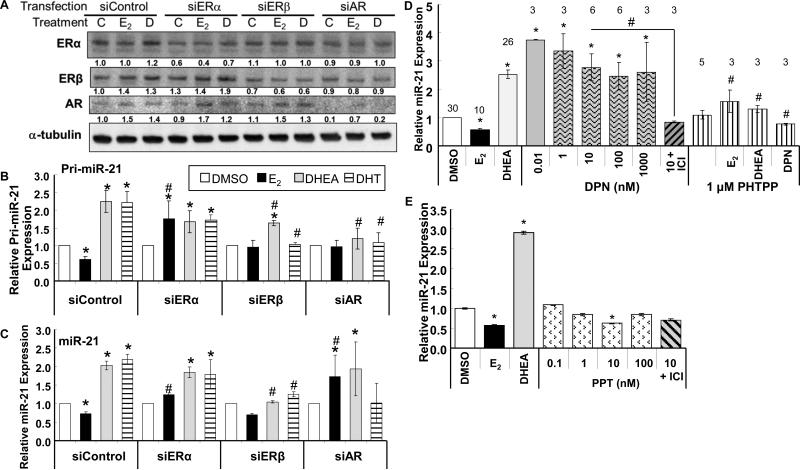

Fig. 3. Knockdown of ERβ and AR implicates DHEA activation of ERβ and AR in upregulating pri-miR-21 transcription.

A, B, and C, HepG2 cells were transfected with 90 pmol of siControl, siERα, siERβ, or siAR. 48 h after transfection, the cells were treated with DMSO (vehicle control (C in panel A)), 10 nM DHEA (D), 10 nM E2 for 6 h. A, WCE (25 μg protein) were immunoblotted with antibodies against the indicated proteins. Blots were stripped and re-probed for α-tubulin. The values below each blot are the ratio of that protein to α-tubulin and normalized to siControl-C-treatment. Pri-miR-21 (B) and miR-21 (C) expression was determined by qPCR relative to RNU48 in HepG2 cells treated for 6 h. Values in DMSO treated samples were set to one. values are the mean ± SEM of 5, 3, 4, and 3 separate determinations for siControl, siERα, siERβ, and siAR, respectively. * p < 0.05 versus the same hormone treatment in siControl transfected cells. D, HepG2 were ‘serum-starved’ for 48 h and then treated with DMSO, 10 nM E2, 10 nM DHEA, or the indicated concentrations of DPN or 1 μM PHTPP +/− 10 nM E2, DHEA, or DPN. E, HepG2 were ‘serum-starved’ for 48 h and then treated with DMSO, 10 nM E2, 10 nM DHEA, or the indicated concentrations of PPT +/− 100 nM ICI 182,780 (ICI). Values are the mean ± SEM of triplicate determinations within one experiment. For B, C, D, and E: * P < 0.05 versus DMSO siControl or DMSO vehicle control. For B, C, and D: # P < 0.05 versus the same treatment + siControl or the same treatment alone.

Both DHEA and DHT increased whereas E2 repressed pri-miR-21 and miR-21 transcript levels (Fig. 3B and 3C). Knockdown of ERα ablated the E2 repression of pri-miR-21 and miR-21 expression, implicating ERα in the repression of pri-miR-21 expression by E2. Knockdown of ERα had no effect on DHEA or DHT-induced pri-miR-21 or miR-21 expression. Knockdown of ERβ had no significant effect on pri-miR-21 or miR-21 expression in E2-treated cells. However, ERβ knockdown significantly inhibited DHEA- and DHT-induced pri-miR-21 and miR-21 expression, suggesting a role for ERβ in the regulation of pri-miR-21 transcription in response to DHEA and DHT. Knockdown of AR ablated the E2, DHEA, and DHT-dependent transcriptional effects on pri-miR-21. However, AR knockdown did not block DHEA-induced miR-21 expression and promoted an E2-dependent increase in miR-21. These data suggest a role for AR in the regulation of pri-miR-21 transcription in response to DHEA and DHT and a possible role in processing or accumulation of mature miR-21 that will require further investigation. AR was reported to stimulate the processing of the pri-miR-23127a24-2 cluster to mature miR-27a in LNCaP prostate cancer cells (Fletcher et al., 2012).

To further examine the role of ERβ in DHEA stimulation of miR-21 expression, HepG2 cells were treated with DPN, an ERβ-selective agonist (Meyers et al., 2001), and PHTPP, an ERβ-selective antagonist (Compton et al., 2004) (Fig. 3D). DPN increased miR-21 transcript levels, commensurate with its ERβ-agonist activity (EC50 = 0.9 nM) (Meyers et al., 2001), and the DPN-induced increase was inhibited by ICI. PHTPP inhibited DHEA-stimulated miR-21 expression ~ 50%, in agreement with the ERβ knockdown results (Fig. 3D). PHTPP inhibited DPN-stimulated miR-21 expression ~ 70%, a positive control. PHTPP blocked the E2-reduction of miR-21 expression. In contrast, ERα-selective agonist PPT significantly inhibited miR-21 transcript expression at 10 nM (Fig. 3E). The lack of inhibition at 100 nM PPT may be due to PPT's activation of ERβ at concentrations of 100 and 1000 nM (Stauffer et al., 2000). Together with the ERβ and AR knockdown experiments (Fig. 3B and 3C), these data support a role for ligand-occupied ERβ and AR stimulating and E2-ERα in inhibiting pri-miR-21 transcription in HepG2 cells.

3.7. DHEA increases ERβ and AR recruitment to the pri-miR-21 promoter

ChIP assays were performed to examine ERα, ERβ, and AR recruitment to the pri-miR-21 promoter in cells treated for 1, 3, or 6 h with 10 nM E2, 10 nM DHEA, or 10 nM DHT (Fig. 4). The ERE (Bhat-Nakshatri et al., 2009) and ARE1 (Ribas et al., 2009) were previously characterized. Transfac analysis identified two additional possible AREs (ARE2 and ARE3 in Fig. 4A and 5A) with ARE3 also a putative progesterone or glucocorticoid RE, consistent with the similar DNA binding domains of AR, PR, and GR (Beato 1991). There was no recruitment of any of ERα, ERβ, or AR to the negative control region in the VMP1/TMEM49 gene and no amplification of PCR products in ChIP reactions using IgG (data not shown, CT undetermined or > 38). No PCR product (CT undetermined) was identified in ERα ChIP assays for any of the primer pairs at the three time points. DHEA significantly increased, whereas E2 significantly inhibited, ERβ recruitment to the ERE 3 h after treatment (Fig. 4B). DHT increased ERβ recruitment to the ERE at 6 h. No ERβ recruitment was detected at 3 h of DHT treatment. AR was not recruited to the ERE (CT undetermined). DHEA increased AR recruitment to both the previously characterized ARE1 and a region containing two imperfect, putative AREs (Fig. 4C). DHT increased AR recruitment to the AREs with 3 and 6 h of treatment (Fig. 4C). E2 had no significant effect on AR recruitment to ARE and increased AR recruitment to ARE2. DHEA increased AR recruitment to ARE1 at all 3 time points (Fig. 4C). ERβ was recruited to the ARE2/3 region after 3 and 6 h of E2 (Fig. 4D). More ERβ recruitment was detected using the ARE2/3 primers after 3 and 6 h of DHEA treatment. (Fig. 4D). Together with the ERβ and AR knockdown data (Fig. 3B and 3C), we suggest that DHEA increases ERβ and AR recruitment to the miR-21 promoter through interaction with the ERE and AREs.

Fig. 5. DHEA directly activates the miR-21 promoter in a reporter assay and increases miR-21 transcription independent of TMEM49.

A, The diagram shows the ERE and ARE sequences within the 5’ flanking region of MIR21 and differences from their consensus sequences are italicized. The nucleotides below the consensus sequence indicate mutations introduced to disrupt each respective response element. HepG2 cells were transfected with firefly luciferase reporter constructs driven by the 5′-flanking region of human MIR21 in the sense or antisense (AS) orientation (Terao et al., 2011) and with mutations in the ERE, ARE1, ARE2, or ARE3. The cells were treated with DMSO, 10 nM E2, 10 nM DHEA, 10 nM DHT, 10 nM 3β-Adiol, or 10 nM DPN (ERβ-selective agonist) +/- a 6 h pre-treatment with 100 nM ICI 182,780 (ICI), 100 nM bicalutamide, or 100 nM PHTPP. Total treatment time with added steroids was 24 h. The results are expressed relative to DMSO in the full-length MIR21-reporter following normalization with Renilla luciferase (mean ± SEM., 34 replicate transfections, each performed in triplicate within each experiment). # p < 0.05 versus the same steroid treatment on the MIR21 wildtype (wt) promoter. B, HepG2 cells ‘serum-starved’ for 48 h and then treated with DMSO or 10 nM DHEA. Values are the mean ± SEM of 6 separate experiments. * Significantly different from fold induction of TMEM49, p < 0.05. C, HepG2 cells were transfected with 90 pmol of siControl, siERα, siERβ, or siAR. 48 h after transfection, the cells were treated with DMSO or 10 nM DHEA for 6 h. Values are the average of 3 separate experiments. * P < 0.05 versus siControl-DMSO treated samples. # p < 0.05 versus the same treatment in siControl transfected cells. Numbers above the siAR data are the fold relative to DMSO in siAR-transfected cells.

3.8. DHEA directly upregulates the miR-21 promoter

To determine if DHEA activates the promoter of miR-21 through the ERE and AREs characterized above, HepG2 cells were transiently transfected with a 1.5 kB miR-21-promoter-luciferase pGL-3 Basic reporter or constructs in which the retinoic acid response element/estrogen response element (RARE-1/ERE) was mutated (EREmut in Fig. 5) (Terao et al., 2011), or with mutations in ARE1, putative ARE2 and ARE3, individually or in combination (Fig. 5). DHEA increased luciferase reporter activity from the full length promoter and the reverse orientation of the miR-21 promoter was inactive, confirming a previous report (Terao et al., 2011). E2 had no significant effect on miR-21 promoter activity. Mutation of the ERE, ARE1, ARE2, and ARE3 sites reduced basal luciferase activity. Mutation of the ERE, ARE1, ARE2, or ARE3 sites inhibited DHEA-induced luciferase activity. Treatment with DHT, 3β-Adiol, or DPN also increased luciferase reporter activity. Fulvestrant (ICI) and PHTPP inhibited DHEA-induced reporter activity. Bicalutamide inhibited DHEA-induced reporter activity. DHT-induced miR-21 reporter activity was inhibited by mutation of the ERE, ARE1, and ARE2. The DHT activation of luciferase from the EREmut and AREmut2/3 constructs was inhibited by fulvestrant (data not shown). Together with the results of the ChIP assays, these data suggest that ERβ and AR recruitment to the ERE and AREs are involved in DHEA-induced pri-miR-21 transcription in HepG2 cells.

3.9. DHEA upregulates pri-miR-21 transcription independent of TMEM49/VMP1 transcript expression

MiR-21 is encoded within the 3’ UTR of TMEM49/VMP1 http://atlasgeneticsoncology.org//Genes/MIRN21ID44019ch17q23.html and miR-21 was initially reported to be regulated independently of TMEM49 (Fujita et al., 2008). However, there is evidence of read-through of TMEM49 increasing miR-21 expression (Inaki et al., 2011; Mudduluru et al., 2011) and that TMEM49 and miR-21 are expressed “in the same direction” in some tissues, e.g., lung adenocarcinoma tumors and normal lung (Seike et al., 2009). There are conflicting data regarding the precise location of the miR-21 promoter (Ribas and Lupold 2010). Most studies of miR-21 regulation have not evaluated TMEM49 expression in parallel with pri-miR-21 and miR-21. DHEA increased TMEM49 expression ~ 1.4-fold in HepG2 cells (Fig. 5B). As recently reported for T3 regulation of miR-21 transcription in HepG2 cells (Huang et al., 2013), the significant differences in fold change of pri-miR-21 and miR-21 versus TMEM49 in DHEA-treated cells indicate direct regulation of pri-miR-21 transcription by DHEA rather than coregulation with TMEM49. Further, whereas knockdown of ERβ and AR, but not ERα, attenuated DHEA-induced pri-miR-21 transcript expression (Fig. 3B), siERα and siAR inhibited DHEA-induced TMEM49 transcript levels (Fig. 5C). Together, these data indicate separate mechanisms regulating TMEM49 and miR-21 transcription in HepG2 cells. As reported previously for MCF-7 cells (Wickramasinghe et al., 2009), E2 did not alter TMEM49 expression in HepG2 cells (data not shown).

3.10. Stimulation of miR-21 transcription by DHEA involves metabolism

DHEA is metabolized into androgens and estrogens (Traish et al., 2011). Because fulvestrant (Fig. 1A), ERβ and AR knockdown (Fig. 3B and 3C), and ERβ-selective antagonist PHTPP (Fig. 3D) inhibited DHEA-induced miR-21 expression, we tested whether inhibition of enzymes that metabolize DHEA into androgens and estrogens (Fig. 6A) would affect DHEA-induced miR-21 expression. Miconazole, a general P450 inhibitor (Fitzpatrick et al., 2001), reduced DHEA-stimulated miR-21 expression, but did not affect E2-suppression of miR-21 (Fig. 6B, and data not shown). These data suggest that DHEA may be metabolized by a P450 enzyme(s) for miR-21 stimulation whereas E2 itself appears to suppress miR-21 expression.

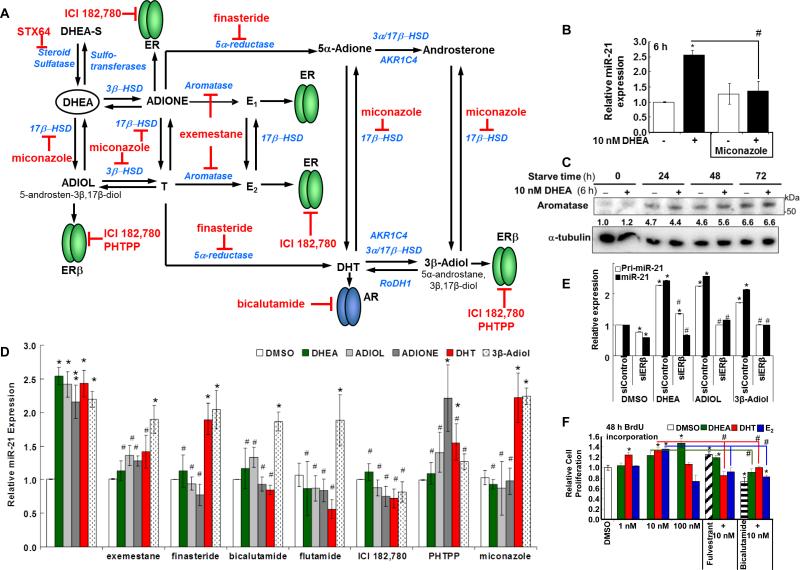

Fig. 6. DHEA metabolites increase miR-21 expression.

A, Model of DHEA metabolites that may activate AR and ERs. This model shows selected aspects of DHEA metabolism and metabolites studied in this report. Inhibitors of enzyme steps (blue) or receptor specific antagonists, e.g ., bicalutamide for AR, ICI for ERα and ERβ, and PHTPP for ERβ, used in this study are indicated in red. DHEA is converted to ADIOL and ADIONE that capable of activating ERs. 3β-Adiol, derived from DHT, is a preferred ERβ ligand (Muthusamy et al., 2011). Further information on the synthesis and metabolism of DHEA is reviewed in (Kihel 2012; Labrie et al., 2005; Miller et al., 2004; Rainey and Nakamura 2008). For B, D, and E, HepG2 cells were ‘serum-starved’ for 48 h prior to treatment as indicated for 6 h. B, Where indicated, cells were pre-incubated with 5 μM miconazole for 1 h prior to 6 h treatment with 10 nM DHEA. Values are the average of 4 separate experiments ± SEM in which each sample was run in triplicate. * p < 0.05 versus DMSO vehicle; # p < 0.05 versus 10 nM DHEA. C, HepG2 cells were grown in ‘serum starvation’ medium for the indicated time. Cells were treated with 10 nM DHEA or DMSO for 6 h. Protein input: 25 μg/lane. The PVDF membranes were probed with antibodies against the indicated proteins. The values below each blot are the ratio of that protein normalized to α-tubulin relative to the time zero serum-starved DMSO treated cells. D, HepG2 cells were treated with DMSO, 10 nM DHEA, 10 nM ADIOL, 10 nM ADIONE, 10 nM DHT, or 10 nM 3β-Adiol +/- the indicated inhibitors for 6 h. Values are the average ± SEM of 25, 13, 13, 11, and 11 separate experiments for DHEA, ADIOL, ADIONE, DHT, and 3β-Adiol, respectively. For the inhibitor studies, values are the average ± SEM of 7, 8, 5, 3, 5, 5,and 5 separate experiments for exemestane, finasteride, bicalutamide, flutamide, ICI 182,780; PHTPP, and miconazole, respectively. Within each experiment, each sample was run in triplicate. *p < 0.05 versus DMSO control. # p < 0.05 versus the same treatment without inhibitor. E, HepG2 cells were transfected with 90 pmol of siControl or siERβ. 48 h after transfection, the cells were treated with DMSO, 10 nM DHEA, 10 nM ADIOL, or 10 nM 3β-Adiol for 6 h. Values are the average of triplicate determinations within one experiment. *p < 0.05 versus siControl/DMSO. # p < 0.05 versus the same treatment without siNR.

We examined the expression of aromatase protein and CYP19A transcript expression in HepG2 cells (Fig. 6C and Supplemental Fig. 5). Aromatase protein levels were increased in HepG2 cells grown in ‘serum-starve’ (5% DCC-stripped FBS) medium for 24-71 h. DHEA appeared to increase aromatase protein after 48 h of serum starvation. CYP19 mRNA transcript levels were increased after 48 h of serum starvation and were unaffected by DHEA (Supplemental Fig. 5). Similarly, serum starvation increased aromatase in MCF-7 breast cancer cells (Sikora et al., 2009). These findings suggest that the serum-starve conditions used prior to our treatment of the HepG2 cells with DHEA increase aromatase which may convert T and DHT to E1 and E2, respectively (Fig. 6A).

We then examined the effect of DHEA metabolites ADIOL, ADIONE, DHT, and 3β-Adiol, all at 10 nM, on miR-21 expression (Fig. 6D). All four DHEA metabolites increased miR-21 transcript expression. Miconazole inhibited the ability of DHEA, but not DHT or 3β-Adiol, to increase miR-21 expression. The aromatase inhibitor exemestane inhibited DHEA, ADIOL, ADIONE, and DHT-induced miR-21 expression, but not 3β-Adiol-induced miR-21 transcript expression. The increase in miR-21 by ADIOL and ADIONE was, like DHEA, inhibited by 5α-reductase inhibitor finasteride, and by the SARMs bicalutamide and flutamide, suggesting activation of AR is involved. DHT-induced miR-21 was inhibited by bicalutamide and flutamide, but not by finasteride, commensurate with AR-stimulation of miR-21 in prostate cancer cells (Ribas and Lupold 2010; Ribas et al., 2009; Waltering et al., 2011). Neither bicalutamide nor flutamide inhibited 3β-Adiol-induced miR-21 transcript expression. Fulvestrant inhibited the increase in miR-21 expression by DHEA, ADIOL, ADIONE, DHT, and 3β-Adiol, suggesting ER involvement. The ERβ-selective antagonist PHTPP inhibited DHEA, ADIOL, DHT, and 3β-Adiol-induced miR-21 expression, suggesting ERβ-involvement. Confirming this suggestion, ERβ knockdown inhibited DHEA-, ADIOL-, and 3β-Adiol- induced pri-miR-21 and miR-21 expression (Fig. 6E). These data are compatible with the Kd values for ADIOL, ADIONE, and 3β-Adiol for ERβ, AR, and ERα, (Supplemental Table 1). The inability of PHTPP to inhibit ADIONE-stimulated miR-21 expression while fulvestrant inhibits this activity suggests ERα involvement, although the mechanism appears different from E2-ERα repression of miR-21 transcription. Taken together, we suggest that DHEA is metabolized to ligands that activate AR and ERβ. We suggest that ADIOL and 3β-Adiol act through ERβ while DHT appears to act through both AR and ERβ to increase miR-21 transcription.

3.11. Inhibition of AR, not ER inhibits DHEA-induced HepG2 cell proliferation

BrdU incorporation assays revealed that DHEA and DHT increased HepG2 cell proliferation (Fig. 6F). E2 did not significantly increase BrdU incorporation. Fulvestrant alone increased HepG2 cell proliferation. However , fulvestrant inhibited BrdU incorporation in cells treated with either DHT or E2, suggesting a role for ER in DHT-induced cell proliferation. Bicalutamide inhibited basal BrdU incorporation and none of the steroids blocked this inhibition, suggesting a role for AR in basal HepG2 cell proliferation.

4. DISCUSSION

miR-21 is one of the ten most abundant miRNAs in human and mouse liver (Androsavich et al., 2012) and miR-21 expression is elevated in HCC (Connolly et al., 2010; Kawahigashi et al., 2009; Meng et al., 2007; Sun et al., 2013; White et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2011), but mechanisms regulating miR-21 expression in liver are undefined. The overall goal of our study was to determine if DHEA regulates miR-21 expression in HCC cells. Here we demonstrated that DHEA increased pri-miR-21 transcription in HepG2 cells and in mouse liver, demonstrating in vivo activation of miR-21 expression by DHEA. The physiological relevance of this study is that the human liver is a major site for metabolism, conjugation, and catabolism of steroids mediated by key enzymes including 17β-HSD, 5α-reductase, and aromatase (Granata et al., 2009). DHEA is converted to higher affinity androgens and estrogens (Fig. 6A) depending on tissue- and cell- specific expression of metabolizing enzymes (Labrie 2010; Labrie et al., 2005; Traish et al., 2011). HepG2 cells express aromatase, 17β-HSD, 5α- and 5β-reductases, and 3β-HSD (Granata et al., 2009). The gender disparity and role of sex steroids in hepatocellular cancer have been reviewed, implicating active AR in augmenting HCC risk (Yeh and Chen 2010) whereas E2 suppression of IL-6 lowers HCC risk in females (Dorak and Karpuzoglu 2012). Estrogens suppress chemical hepatocarcinogenesis in rats (Shimizu 2003) and reduce hepatic steatosis in aromatase knockout mice (Nemoto et al., 2000).

The studies reported here are unique from the past literature because we used DHEA concentrations, i.e., ~ 10 nM, that are physiologically relevant for men and women 40-60 years of age (Labrie 2010; Labrie et al., 1997) and low for young adults. We observed that nM concentrations of E2 repressed, whereas DHEA increased, pri-miR-21 transcription and miR-21 expression in HepG2 cells. Likewise, DHEA increased miR-21 in HBEC2-KT, H1793 lung adenocarcinoma; MCF-7, T47D, and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell lines, but not in LY2 endocrine-resistant breast cancer cells or MCF-10A normal breast epithelial cells, suggesting cell line-specific differences in miR-21 regulation which require further study. Stimulation of miR-21 transcription by DHEA in HepG2 cells was independent of the expression of TMEM49/VMP1, in which it is encoded, and appears to be mediated by DHEA metabolites that activate ERβ and AR, as indicated by the ability of ERβ and AR knockdown, the 5α-reductase inhibitor finasteride, the SARMs bicalutamide and flutamide, the ER antagonist fulvestrant, and the ERβ-selective antagonist PHTPP to inhibit DHEA-stimulated pri- and miR-21 transcription. DHEA stimulated ERβ and AR recruitment to the miR-21 promoter in HepG2 cells, consistent with enhanced pri-miR-21 transcription. Mutational analysis of the miR-21 promoter indicates roles for an ERE and three AREs in DHEA-induced promoter activity in transient transfection assays. In contrast, E2 inhibited pri-miR-21 transcription and reduced levels of mature miR-21 in HepG2 cells in an ERα-dependent manner, consistent with findings in MCF-7 breast cancer cells (Wickramasinghe et al., 2009). miR-21 is lower in ERβ negative breast tumors (Paris et al., 2012), suggesting a possible positive role for ERβ in miR-21 expression. These observations agree with our observation that 3β-Adiol, which has higher affinity for ERβ than ERα or AR (Supplemental Table 1), stimulates miR-21 transcription by activating ERβ, and that DHEA metabolites such as ADIOL, ADIONE, and DHT activate AR and ERβ to increase miR-21 transcription.

DHEA stimulated AR recruitment to the AREs in the miR-21 promoter and knockdown of AR inhibited DHEA-induced pri-miR-21 transcript levels, suggesting that AR directly increases pri-miR-21 transcription. This observation agrees with reports that AR upregulates miR-21 expression in prostate cancer cells (Ribas and Lupold 2010; Ribas et al., 2012; Ribas et al., 2009). A recent study showed that miR-21 and AR form a positive feedback loop, upregulating each other's expression in prostate cancer cell lines (Mishra et al., 2013). ERβ appears to be required for both DHEA-stimulated pri-miR-21 transcription and mature miR-21 expression. ERβ blocked ERα binding to the Drosha complex by heterodimerizing with ERα and thus relieving ERα's repression of miRNA processing (Paris et al., 2012).

DHT increased pri-miR-21 expression in an AR-dependent manner, e.g., inhibited by siAR and by SARMs bicalutamide and flutamide. However, ER antagonist fulvestrant and the ERβ-selective antagonist PHTPP inhibited not only DHEA- but also DHT- activated miR-21 expression, suggesting that DHT is either directly activating ERβ, a suggestion reflecting DHT's Kd of ~ 79 nM for ERβ(Supplemental Table 1), or that DHT is metabolized to an estrogen, e.g., 3β-Adiol (Fig. 6A) (Kuiper et al., 1997; Weihua et al., 2002).

The interactions between AR and ERs have yet to be fully characterized. Full length AR interacted with the LBD of ERα, but not ERβ, in a mammalian two-hybrid assay (Panet-Raymond et al., 2000). ERα, not ERβ, selectively inhibited AR transcriptional activity in a reporter assay in transfected CV-1 cells (Panet-Raymond et al., 2000). Conversely, AR inhibited ERα, not ERβ, transcriptional activity on an ERE-driven reporter in the same cell system (Panet-Raymond et al., 2000). However, the interaction of AR and ERs may depend on cell-specific factors since while ERα and AR proteins were coimmunoprecipitated in MCF-7 cells, ERβ interacted with AR in LNCaP prostate cancer cells (Migliaccio et al., 2005). Here our inhibitor and ChIP data suggest that DHEA increases ERβ and AR recruitment to the miR-21 promoter. Although AR has a wider range of DNA binding sites than ERα and AR binds EREs (Peters et al., 2009), we did not detect AR recruitment to the ERE in the miR-21 promoter, whereas we detected ERβ recruitment to the ARE-containing region. This observation is consistent with ERβ interaction with AP-1 transcription factors bound to AP-1 elements (Grober et al., 2011; Vivar et al., 2010) which are located in the pri-miR-21 promoter (Fujita et al., 2008). While ChIP-seq has revealed genomic and transcriptional cross-talk between AR and ERα signaling in ZR-75-a breast cancer cells (Need et al., 2012), there appear to be no studies directly examining ERβ-AR crosstalk at the level of chromatin binding.

Our results are compatible with studies showing that T (1 nM) was metabolized to ADIONE, epiandrosterone, etiocholan-3α-ol-17-one, etiocholan-3β-ol-17-one, 19-OH-ADIONE, and E2-sulfate in HepG2 cells with 24 h treatment (Granata et al., 2009). The authors concluded that aromatase was responsible for conversion of 50% of T in HepG2 cells (Granata et al., 2009). Another study followed the disappearance of 10 μM DHEA in HepG2 cells and reported a nonsignificant 18% decrease at 24 h, but a significant decrease at 48 h with no DHEA remaining at 72 h (Pall et al., 2009). Studies in male bovine liver slices revealed that 17-24% of input DHEA was metabolized to ADIONE, 7α-OH-DHEA, ADIOL, 7-oxo-DHEA, and other hydroxylor oxo- metabolites (Rijk et al., 2012), similar to findings in male rat liver with 12 h treatment (Miller et al., 2004). In A549 lung adenocarcinoma cells, ~ 69% of DHEA was metabolized in 24 h, but significant (~ 30%) conversion to ADIOL, ADIONE, and T was detected after 8 h, whereas DHT showed more rapid metabolism (~ 40% by 2 h and 75% by 5 h) (Provost et al., 2000). In MCF-7 human breast cancer cells, DHEA was metabolized to estrone, E2, T, DHT, ADIONE, and ADIOL after 40 h (Le Bail et al., 2002). Although our studies used nM DHEA for 6 h in HepG2 cells, thus not allowing direct comparison to the time course of metabolites formed, our results using metabolic inhibitors, ER and AR antagonists, and siRNA knockdown of ERα, ERβ, and AR led us to propose the model shown in Fig. 7 for ERβ and AR activation. DHEA metabolites stimulate recruitment of ERβ and AR to the pri-miR-21 promoter, thereby increasing transcription with commensurate downstream effects of miR-21 repression of Pdcd4 protein expression and increased cell viability.

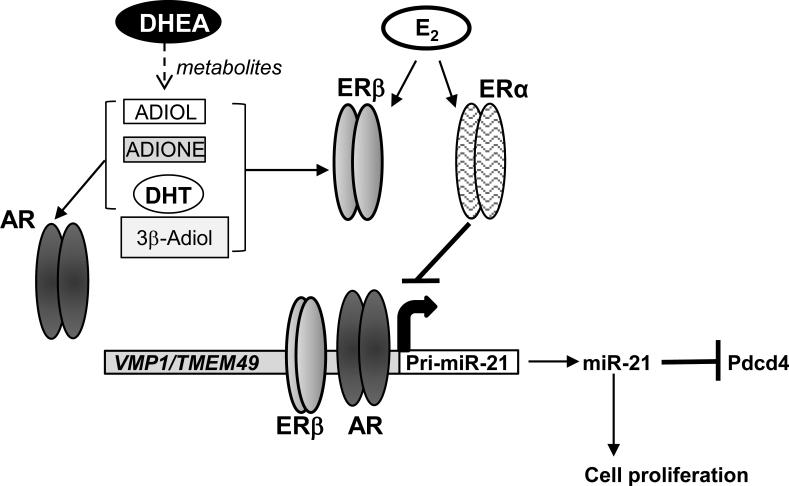

Fig. 7. Model of DHEA metabolism to ligands that activate AR and ERβ which increase pri-miR-21 transcription in HepG2 cells.

The data presented here suggest that DHEA is metabolized to ligands that activate AR and ERβ and increase their recruitment to the pri-miR-21 promoter and stimulate miR-21 expression. We show that ADIOL, ADIONE, DHT, and 3β-Adiol stimulate pri-miR-21 transcription by acting as ligands for AR and ERβ. In turn, miR-21inhibits Pdcd4 mRNA and protein expression and increases cell proliferation. We show that the aptamer AS1411, an inhibitor of nucleolin which is involved in miR-21 processing (Pichiorri et al., 2013), inhibits DHEA-induced miR-21 expression, not pri-miR-21 transcription. In contrast, E2 activation of ERα inhibits miR-21 expression by its interaction with p68/Drosha complex inhibiting processing of the pri-miR-21 transcript.

DHEA is reversibly sulfated by sulfotransferases primarily in the adrenals, liver, and small intestine. We showed that DHEA-S, like DHEA, increased miR-21 expression in HepG2 cells. Notably, the steroid sulfatase inhibitor STX64, developed for the treatment of hormone-dependent breast cancer (Purohit et al., 2011), blocked DHEA-S, not DHEA, induction of miR-21. These data indicate that DHEA-S does not induce miR-21 expression until it is converted to DHEA and subsequently metabolized to androgens that induce miR-21 expression through AR. Interestingly, SULT2A1 mRNA and protein expression is reduced in HCC tumors, a result that would be expected to increase local androgen levels (Huang et al., 2005).

Tumor suppressor Pdcd4 protein levels are lower in human hepatomas compared to normal human liver tissue samples whereas miR-21 is higher in hepatomas than normal liver (Zhu et al., 2012). Here we observed that DHEA reduced Pdcd4 protein and PDCD4 mRNA levels. Further, DHEA reduced luciferase activity from a PDCD4 3’UTR reporter in transiently transfected HepG2 cells and this was blocked by transfection with AS miR-21. Together, these data indicate that the increase in miR-21 in DHEA-treated HepG2 cells functions to reduce Pdcd4 protein levels.

Previously reported results showed that DHEA and DHEA-S inhibited HepG2 cell proliferation at 24- 72 h, but 1-200 μM concentrations were used (Jiang et al., 2005). The doses of DHEA and DHEA-S used throughout the present study, ranging from 0.1 nM to 1 μM, were based on serum concentrations in healthy adults, i.e., ~ 20 nM DHEA (Labrie 2010). We observed that DHEA increased HepG2 cell viability and BrdU incorporation and anti-miR-21 inhibited the stimulation of cell viability, suggesting that stimulation of miR-21 expression plays a role mediating the growth stimulatory effects of these sterols. Our data implicate AR in particular and secondarily ER in DHEA-induced cell proliferation in BrdU incorporation assays, although which ER is involved will require further study. miR-21 is known to play a role in invasion based on its ability to downregulate PDCD4 (Asangani et al., 2008), RECK and TIMP3 (Gabriely et al., 2008) (Zhu et al., 2008), and SULF1 (Bao et al., 2013). A recent study reported higher miR-21 in invasive ERα+/PR+, but not ERα-/PR−, breast tumors (Petrović et al., 2014). Another study reported that thyroid hormone (T3) stimulated cell migration and invasion of HepG2 cells stably expressing thyroid hormone receptors α1 (TRα1) and TRβ1 by down regulating TIAM1 (Huang et al., 2013). An important follow-up study will be to examine whether DHEA downregulates TIAM1 in HepG2 cells and increases Wnt-β-catenin signaling and cell migration and invasion.

In summary, this study revealed that DHEA increases pri-miR-21 transcription and the increase in mature miR-21 transcription downregulates PDCD4 and stimulates HepG2 cell viability in a miR-21 responsive manner. Our studies suggest that the mechanism by which DHEA increases miR-21 appears to involve conversion of DHEA to estrogens that activate ERβ and androgens that activate AR, resulting in recruitment of ERβ and AR to the pri-miR-21 promoter. In contrast to the stimulation by DHEA, E2-ERα inhibits miR-21 transcript levels, commensurate with previous studies by us and other investigators in breast cancer cells (reviewed in (Klinge 2012)).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

DHEA increases pri-miR-21 transcription independent of VMP1/TMEM49 transcription

DHEA-regulated miR-21 reduces Pdcd4 protein in HepG2 cells

DHEA increases AR and ERβ recruitment to the 5’ promoter of MIR21

DHEA-induced HepG2 cell viability is mediated in part by increased miR-21

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by NIH grant R01 CA138410 to C.M.K. We thank Dr. Boaz Robinzon for his suggestions for experiments. We thank Dr. Enrico Garattini for providing the MIR21-promoter luciferase reporters and Dr. Zhemin Lei for providing flutamide. We thank Jake D. Bell and Brandie N. Radde for performing some experiments included in this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ADIONE

androst-5-ene-3,17-dione

- ADIOL

androst-5-ene-3β,17β-diol

- 3β-Adiol

5α-androstane-3β,17β-diol

- AR

androgen receptor

- ARE

androgen response element

- ChIP

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

- CHX

cycloheximide

- DHEA

dehydroepiandrosterone

- DHEA-S

DHEA sulfate

- DHT

dihydrotestosterone

- Dox

doxorubicin

- E2

estradiol

- ERα

estrogen receptor α

- ERβ

ERβ

- ERE

estrogen response element

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- 5-FU

5-fluorouracil

- ICI 182, 780; ICI

Fulvestrant

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- LBD

ligand binding domain

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- PXR/SXR, NR1I2

pregnane X receptor/steroid and xenobiotic receptor

- qPCR

quantitative Real-Time PCR

- RARE

retinoic acid response element

- 4-OHT

4-hydroxytamoxifen

- T

testosterone

- SARM

selective androgen receptor modulator

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

YT, LML, MMI, RAP, BJC, and CMK have nothing to declare

Disclosures: The authors have nothing to declare.

References

- Abou-Alfa GK, Johnson P, Knox JJ, Capanu M, Davidenko I, Lacava J, Leung T, Gansukh B, Saltz LB. Doxorubicin Plus Sorafenib vs Doxorubicin Alone in Patients With Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;304:2154–2160. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Androsavich J, Chau B, Bhat B, Linsley P, Walter N. Disease-linked microRNA-21 exhibits drastically reduced mRNA binding and silencing activity in healthy mouse liver. RNA. 2012;18:1510–1526. doi: 10.1261/rna.033308.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asangani IA, Rasheed SAK, Nikolova DA, Leupold JH, Colburn NH, Post S, Allgayer H. MicroRNA-21 (miR-21) post-transcriptionally downregulates tumor suppressor Pdcd4 and stimulates invasion, intravasation and metastasis in colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:2128–2136. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao L, Yan Y, Xu C, Ji W, Shen S, Xu G, Zeng Y, Sun B, Qian H, Chen L, Wu M, Chen J, Su C. MicroRNA-21 suppresses PTEN and hSulf-1 expression and promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression through AKT/ERK pathways. Cancer Lett. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beato M. Transcriptional control by nuclear receptors. The FASEB Journal. 1991;5:2044–2051. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.5.7.2010057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat-Nakshatri P, Wang G, Collins NR, Thomson MJ, Geistlinger TR, Carroll JS, Brown M, Hammond S, Srour EF, Liu Y, Nakshatri H. Estradiol-regulated microRNAs control estradiol response in breast cancer cells. Nucl. Acids Res. 2009;37:4850–4861. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdeau V, Deschenes J, Laperriere D, Aid M, White JH, Mader S. Mechanisms of primary and secondary estrogen target gene regulation in breast cancer cells. Nucl. Acids Res. 2008;36:76–93. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovenberg SA, van Uum SH, Hermus AR. Dehydroepiandrosterone administration in humans: evidence based? Neth. J. Me. 2005;63:300–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brueggemeier RW. Overview of the pharmacology of the aromatase inactivator exemestane. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2002;74:177–85. doi: 10.1023/a:1016121822916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton M, Angulo P, Chalasani N, Merriman R, Viker K, Charatcharoenwitthaya P, Sanderson S, Gawrieh S, Krishnan A, Lindor K. Low circulating levels of dehydroepiandrosterone in histologically advanced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2008;47:484–492. doi: 10.1002/hep.22063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Knecht K, Birzin E, Fisher J, Wilkinson H, Mojena M, Moreno CT, Schmidt A, Harada S.-i, Freedman LP, Reszka AA. Direct Agonist/Antagonist Functions of Dehydroepiandrosterone. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4568–4576. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton DR, Sheng S, Carlson KE, Rebacz NA, Lee IY, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. Pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidines: estrogen receptor ligands possessing estrogen receptor beta antagonist activity. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:5872–93. doi: 10.1021/jm049631k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly EC, Van Doorslaer K, Rogler LE, Rogler CE. Overexpression of miR-21 Promotes an In vitro Metastatic Phenotype by Targeting the Tumor Suppressor RHOB. Mol. Cancer Res. 2010;8:691–700. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Leva G, Piovan C, Gasparini P, Ngankeu A, Taccioli C, Briskin D, Cheung DG, Bolon B, Anderlucci L, Alder H, Nuovo G, Li M, Iorio MV, Galasso M, Ramasamy S, Marcucci G, Perrotti D, Powell KA, Bratasz A, Garofalo M, Nephew KP, Croce CM. Estrogen Mediated-Activation of miR-191/425 Cluster Modulates Tumorigenicity of Breast Cancer Cells Depending on Estrogen Receptor Status. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003311. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorak MT, Karpuzoglu E. Gender Differences in Cancer Susceptibility: An Inadequately Addressed Issue. Frontiers in Genetics. 2012;3:268. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty SM, Mazhawidza W, Bohn AR, Robinson KA, Mattingly KA, Blankenship KA, Huff MO, McGregor WG, Klinge CM. Gender difference in the activity but not expression of estrogen receptors alpha and beta in human lung adenocarcinoma cells. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2006;13:113–134. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:1118–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng H, Cheng ASL, Tsang DP, Li MS, Go MY, Cheung YS, Zhao G.-j, Ng SS, Lin MC, Yu J, Lai PB, To KF, Sung JJY. Cell cycle–related kinase is a direct androgen receptor–regulated gene that drives β-catenin/T cell factor–dependent hepatocarcinogenesis. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2011;121:3159–3175. doi: 10.1172/JCI45967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick JL, Ripp SL, Smith NB, Pierce WM, Jr., Prough RA. Metabolism of DHEA by cytochromes P450 in rat and human liver microsomal fractions. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2001;389:278–87. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher CE, Dart DA, Sita-Lumsden A, Cheng H, Rennie PS, Bevan CL. Androgen-regulated processing of the oncomir MiR-27a, which targets Prohibitin in prostate cancer. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012;21:3112–3127. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster PA, Chander SK, Newman SP, Woo LWL, Sutcliffe OB, Bubert C, Zhou D, Chen S, Potter BVL, Reed MJ, Purohit A. A New Therapeutic Strategy against Hormone-Dependent Breast Cancer: The Preclinical Development of a Dual Aromatase and Sulfatase Inhibitor. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008;14:6469–6477. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita S, Ito T, Mizutani T, Minoguchi S, Yamamichi N, Sakurai K, Iba H. miR-21 Gene Expression Triggered by AP-1 Is Sustained through a Double-Negative Feedback Mechanism. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;378:492–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriely G, Wurdinger T, Kesari S, Esau CC, Burchard J, Linsley PS, Krichevsky AM. MicroRNA 21 Promotes Glioma Invasion by Targeting Matrix Metalloproteinase Regulators. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008;28:5369–5380. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00479-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel RM, Cappola AR. Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate and postmenopausal women. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2011 doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e3283461818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granata OM, Cocciadifero L, Campisi I, Miceli V, Montalto G, Polito LM, Agostara B, Carruba G. Androgen metabolism and biotransformation in nontumoral and malignant human liver tissues and cells. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2009;113:290–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green SM, Mostaghel EA, Nelson PS. Androgen action and metabolism in prostate cancer. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2012;360:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.09.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grober O, Mutarelli M, Giurato G, Ravo M, Cicatiello L, De Filippo M, Ferraro L, Nassa G, Papa M, Paris O, Tarallo R, Luo S, Schroth G, Benes V, Weisz A. Global analysis of estrogen receptor beta binding to breast cancer cell genome reveals an extensive interplay with estrogen receptor alpha for target gene regulation. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer F, Subtil S, Lux P, Maser-Gluth C, Stewart PM, Allolio B, Arlt W. No Evidence for Hepatic Conversion of Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) Sulfate to DHEA: In Vivo and in Vitro Studies. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005;90:3600–3605. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho HY, Cheng ML, Chiu HY, Weng SF, Chiu DT. Dehydroepiandrosterone induces growth arrest of hepatoma cells via alteration of mitochondrial gene expression and function. Int. J. Oncol. 2008;33:969–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L-R, Coughtrie MWH, Hsu H-C. Down-regulation of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfotransferase gene in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2005;231:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y-H, Lin Y-H, Chi H-C, Liao C-H, Liao C-J, Wu S-M, Chen C-Y, Tseng Y-H, Tsai C-Y, Lin S-Y, Hung Y-T, Wang C-J, Lin CD, Lin K-H. Thyroid Hormone Regulation of miR-21 Enhances Migration and Invasion of Hepatoma. Cancer Res. 2013;73:2505–2517. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda Y, Tajima S, Izawa-Ishizawa Y, Kihira Y, Ishizawa K, Tomita S, Tsuchiya K, Tamaki T. Estrogen Regulates Hepcidin Expression via GPR30-BMP6-Dependent Signaling in Hepatocytes. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e40465. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaki K, Hillmer AM, Ukil L, Yao F, Woo XY, Vardy LA, Zawack KFB, Lee CWH, Ariyaratne PN, Chan YS, Desai KV, Bergh J, Hall P, Putti TC, Ong WL, Shahab A, Cacheux-Rataboul V, Karuturi RKM, Sung W-K, Ruan X, Bourque G, Ruan Y, Liu ET. Transcriptional consequences of genomic structural aberrations in breast cancer. Genome Res. 2011;21:676–687. doi: 10.1101/gr.113225.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova MM, Mazhawidza W, Dougherty SM, Minna JD, Klinge CM. Activity and intracellular location of estrogen receptors [alpha] and [beta] in human bronchial epithelial cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2009;205:12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang R, Deng L, Zhao L, Li X, Zhang F, Xia Y, Gao Y, Wang X, Sun B. miR-22 Promotes HBV-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma Development in Males. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011;17:5593–5603. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Miyazaki T, Honda A, Hirayama T, Yoshida S, Tanaka N, Matsuzaki Y. Apoptosis and inhibition of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway in the anti-proliferative actions of dehydroepiandrosterone. J. Gastroenterol. 2005;40:490–497. doi: 10.1007/s00535-005-1574-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahigashi Y, Mishima T, Mizuguchi Y, Arima Y, Yokomuro S, Kanda T, Ishibashi O, Yoshida H, Tajiri T, Takizawa T. MicroRNA profiling of human intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma cell lines reveals biliary epithelial cell-specific microRNAs. Journal of Nihon Medical School = Nihon Ika Daigaku zasshi. 2009;76:188–97. doi: 10.1272/jnms.76.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kihel LE. Oxidative metabolism of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and biologically active oxygenated metabolites of DHEA and epiandrosterone (EpiA) – Recent reports. Steroids. 2012;77:10–26. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinge CM. miRNAs and estrogen action. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2012;23:223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper GG, Carlsson B, Grandien J, Enmark E, Haggblad J, Nilsson S, Gustafsson J-A. Comparison of the ligand binding specificity and transcript tissue distribution of estrogen receptors α and β. Endocrinology. 1997;138:863–870. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.3.4979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrie F. DHEA, Important Source of Sex Steroids in Men and Even More in Women. In: Luciano M, editor. Prog. Brain Res. Elsevier; 2010. pp. 97–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrie F, Bélanger A, Cusan L, Gomez J-L, Candas B. Marked Decline in Serum Concentrations of Adrenal C19 Sex Steroid Precursors and Conjugated Androgen Metabolites During Aging. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1997;82:2396–2402. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.8.4160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrie F, Luu-The V, Bélanger A, Lin S-X, Simard J, Pelletier G, Labrie C. Is dehydroepiandrosterone a hormone? J. Endocrinol. 2005;187:169–196. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bail JC, Lotfi H, Charles L, Pepin D, Habrioux G. Conversion of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate at physiological plasma concentration into estrogens in MCF-7 cells. Steroids. 2002;67:1057–1064. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(02)00064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Dillon JS. Dehydroepiandrosterone Activates Endothelial Cell Nitric-oxide Synthase by a Specific Plasma Membrane Receptor Coupled to Galpha i2,3. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:21379–88. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200491200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Dillon JS. Dehydroepiandrosterone stimulates nitric oxide release in vascular endothelial cells: evidence for a cell surface receptor. Steroids. 2004;69:279–89. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Iruthayanathan M, Homan LL, Wang Y, Yang L, Wang Y, Dillon JS. Dehydroepiandrosterone Stimulates Endothelial Proliferation and Angiogenesis through Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase 1/2-Mediated Mechanisms. Endocrinology. 2008;149:889–898. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, O'Leary B, Iruthayanathan M, Love-Homan L, Perez-Hernandez N, Olivo HF, Dillon JS. Evaluation of a novel photoactive and biotinylated dehydroepiandrosterone analog. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2010;328:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S-F, Mo Q, Hu S, Garippa C, Simon NG. Dehydroepiandrosterone upregulates neural androgen receptor level and transcriptional activity. J. Neurobiol. 2003;57:163–171. doi: 10.1002/neu.10260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z, Liu M, Stribinskis V, Klinge CM, Ramos KS, Colburn NH, Li Y. MicroRNA-21 Promotes Cell Transformation by Targeting the Programmed Cell Death 4 Gene. Oncogene. 2008;27:4373–9. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma WL, Hsu CL, Wu MH, Wu CT, Wu CC, Lai JJ, Jou YS, Chen CW, Yeh S, Chang C. Androgen Receptor Is a New Potential Therapeutic Target for the Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:947–955. e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.05.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madak-Erdogan Z, Charn TH, Jiang Y, Liu ET, Katzenellenbogen JA, Katzenellenbogen BS. Integrative genomics of gene and metabolic regulation by estrogen receptors alpha and beta, and their coregulators. Mol Syst Biol. 2013;9:676. doi: 10.1038/msb.2013.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maillot G, Lacroix-Triki M, Pierredon S, Gratadou L, Schmidt S, Benes V, Roche H, Dalenc F, Auboeuf D, Millevoi S, Vagner S. Widespread Estrogen-Dependent Repression of microRNAs Involved in Breast Tumor Cell Growth. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8332–8340. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]