Abstract

Background

In people with early autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) average total kidney volume (TKV) is three times normal and increases by an average of 5% per year despite seemingly normal glomerular filtration rate (GFR). We hypothesized that increased TKV would be a source of morbidity and diminished quality of life that would be worse in subjects with more advanced disease.

Study Design

Cross-sectional.

Setting & Participants

1043 subjects with ADPKD, hypertension and a baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) >20 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Predictors

1) eGFR 2) height-adjusted TKV (htTKV) in subjects with eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Outcomes

36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) and the Wisconsin Brief Pain Survey.

Measurements

Questionnaires were self- administered. eGFR was estimated from serum creatinine using the CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) equation. The htTKV was measured by MRI.

Results

Back pain was reported by 50% of subjects and 20% experienced it ‘often, usually, or always’. In subjects with early disease (eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2) there was no association between pain and htTKV, except in patients with large kidneys (htTKV >1000 mL/m). Comparing across eGFR levels and including patients with eGFR <60 mL/min/ 1.73 m2, patients with eGFR 20–44 mL/min/1.73 m2 were significantly more likely to report that pain impacted on their daily lives and had lower SF-36 scores than patients with eGFR 45–60 and ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Symptoms relating to abdominal fullness were reported by 20% of patients, and were significantly related with lower eGFR in women but not men.

Limitations

TKV and liver volume were not measured in subjects with eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2. The number of patients with eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 is small. Causal inferences are limited by cross-sectional design.

Conclusions

Pain is a common early symptom in the course of ADPKD, although it is not related to kidney size in early disease (eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2), except in individuals with large kidneys (htTKV >1000 mL/m). Symptoms relating to abdominal fullness and pain are greater in patients with more advanced (eGFR 20–45 mL/min/ 1.73 m2) disease and may be due to organ enlargement, especially in women. More research about the role of TKV in quality of life and outcomes of ADPKD patients is warranted.

Keywords: ADPKD, QoL, CKD, patient-reported outcomes, extrarenal symptoms, renal disease, activities of daily life

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is unique among forms of chronic kidney disease (CKD) for the growth of cysts and enlargement of the kidneys, which occur well before kidney function declines. Past studies show that more than 60% of adult patients and 35% of children with ADPKD report pain, often despite normal kidney function, i.e. decades before they reach End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) [1, 2]. There are many causes of pain in ADPKD, including cyst expansion under the renal capsule, traction on the renal pedicle, compression of nearby structures by kidney or liver cysts, or mechanical back pain that arises from an exaggerated pelvic tilt and increased lumbar lordosis [3]. The average rate of kidney growth among individuals with early disease (eGFR > 60 mL/min/1.73 m2), was estimated at 5.3%±4.0% per year in the Consortium for Radiologic Imaging for the Study of Polycystic Kidney Disease (CRISP) Study, and this has been consistent across studies [4–6]. The kidneys are estimate to double in size over eight years[7]. Liver cysts are very common, found in 85% of individuals >30 years of age in the CRISP cohort at baseline[8], and further contribute to abdominal distension and symptoms related to increased abdominal mass. The continuous enlargement of the kidneys and liver occurs well before reaching ESRD and can be the source of severe morbidity that is different than that associated with declining kidney function or its treatment.

Formal study of the impact of ADPKD on quality of life has been limited. While some studies have described symptoms [9–11], the impact on daily living and the changes that occur with disease progression have not been systematically characterized. The largest study to date consisted of 101 patients with preserved GFR (eGFR >70 mL/min/1.73 m2) who completed the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) and at the same time had TKV measured by MRI [12]. Results showed that SF-36 scores were well preserved and much better than those of other CKD patients, but did not correlate with TKV. However, this study was limited by its small sample size, the use of a generic HRQoL instrument only and the lack of selection for patients at high risk for progression to ESRD (e.g. presence of hypertension).

The HALT PKD Trials consist of two randomized clinical trials that are examining combination ACE inhibitor/ARB use as compared with ACE-I use alone in hypertensive patients with eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (Study A) and eGFR 25–60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (Study B) [13]. Participants completed the SF-36 [14] and a modified [9]version of the Wisconsin Brief Pain Survey[15], at baseline, prior to intervention. This provides a unique opportunity to describe the symptoms and their interference with daily living at early through to more advanced stages of ADPKD. We hypothesized that symptoms, including pain and mass effects, would be worse in individuals with larger kidneys. Kidney volume was measured by MRI at the time of questionnaire administration in Study A patients only. Even though total kidney volume (TKV) was not measured in Study B patients, we hypothesized that there would be a relationship of pain and symptoms with disease severity (as defined by eGFR) in Study B patients, given the known strong inverse correlation of GFR with TKV [7, 16, 17].

Methods

Study Population

The design and implementation of the HALT-PKD Trials and the baseline characteristics of this population have been reported in detail elsewhere [13]. Briefly, the HALT-PKD trials are two prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled multicenter interventional trials testing whether multilevel blockade of the RAAS using angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors plus angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) (lisinopril plus telmisartan) combination therapy will delay progression of kidney disease compared with ACEI (lisinopril plus placebo) monotherapy in studies A and B, and whether low blood pressure control (95–100/60–75 mmHg) will delay progression as compared with standard control (120–130/70–80 mmHg) in study A. In study A, patients are aged 15–49 years with eGFR >60 ml/min/1.73 m2, whereas in study B, patients are aged 18–64 years with eGFR of 20–60 ml/min/1.73 m2. All patients undergo a formal screening visit to verify eligibility, diagnosis of ADPKD, and assignment to study A or study B, based on eGFR. All HALT-PKD participants are hypertensive, as defined by current use of antihypertensive medications for blood pressure control or systolic blood pressure of >130 mmHg and/or a diastolic blood pressure of >80 mmHg on three separate readings within the past year.

HRQoL Measurement

Patients completed the SF-36 [18] and a modified version [9] of the Wisconsin Brief Pain Survey [15] while attending the baseline visit. The pain questionnaire consisted of questions that asked about the location, frequency and intensity of pain, treatments that had been used and their effectiveness in relieving pain and the degree to which pain interfered with activities of daily life. The patients completed the questionnaires without assistance from study staff.

Statistical Analyses

Patients were categorized into three groups based on their eGFR values. eGFR was estimated from the CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) creatinine equation standardized for a body surface area of 1.73 m2. The cutpoints for eGFR subgroups were 20–44, 45–60 and >60 ml/min/1.73 m2. Individual items on the pain questionnaire were primarily dichotomous (yes/no) and were analyzed as such. For questions that had Likert-type answers (never, rarely, sometimes, often, usually, always), the first two responses were consolidated as well as the last three, resulting in three distinct groups. Pain questionnaire items were compared across eGFR groups within genders using Fisher’s exact test or Kruskal-Wallis. SF-36 component scores were summarized by sample means and compared across the three eGFR groups within genders using the Kruskal-Wallis test. The relationship between pain and height-adjusted total kidney volume (htTKV) was quantified by computing the median htTKV for each answer of a particular pain question. Spearman rank correlations (r) were calculated between htTKV and each SF-36 component to investigate the relationship between quality of life and kidney enlargement. In addition, median SF-36 component scores were compared to age- and gender-matched median component scores from the general population. In addition to ‘within gender’ analyses, pain questionnaire responses were also compared between genders while collapsing across eGFR and htTKV categories. Due to the between-gender variability in htTKV, the analyses on kidney volume was conducted within and across genders. For analyses that compared more than two groups, Bonferroni-adjusted significance levels were used to account for pairwise comparisons.

Results

Study Participants

The SF-36 questionnaire and pain survey were completed at baseline by 552 of 558 (98.9%) and 555 of 558 (99.5%) of Study A patients, and 479 of 486 (98.6%) and 480 of 486 (98.8%) of Study B patients, respectively. Baseline characteristics of participants across eGFR levels are as described in Table 1 and in a prior publication [17]. Patients in the eGFR 20–44 mL/min/1.73 m2 subgroup were older, had a longer time interval since diagnosis of ADPKD, were more likely to be married and to have a college education, and were a little more likely to be retired or disabled. The mean eGFR values in the eGFR strata of 20–44, 45–60, and >60 mL/min/1.73 m2, respectively, were 36.8 ± 5.3 (standard deviation), 52.4 ± 4.5, and 84.7 ±18.3 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics Across eGFR Subgroups

| eGFR>60 (n=609) |

eGFR 45–60 (n=221) |

eGFR 20–44 (n=213) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 37.3 ± 9.3 | 47.0(7.8) | 49.1(8.2) | <0.001* |

| Years since diagnosis | 9.3(8.4) | 14.4(10.1) | 15.5(10.8) | <0.001* |

| Male sex | 303(49.8%) | 113(51.1%) | 107(50.2%) | 0.9 |

| Race | 0.9 | |||

| Caucasian | 562(92.7%) | 209(94.6%) | 199(93.9%) | |

| African American | 16(2.6%) | 5(2.3%) | 5(2.4%) | |

| Other | 28(4.6%) | 7(3.2%) | 8(3.8%) | |

| Highest education level | 0.03* | |||

| Some high school | 18(3.0%) | 1(0.5%) | 2(0.9%) | |

| Complete high school/equivalent | 69(11.4%) | 20(9.1%) | 28(13.2%) | |

| Some college | 138(22.8%) | 51(23.1%) | 55(25.9%) | |

| Completed college | 233(38.5%) | 77(34.8%) | 64(30.2%) | |

| Graduate studies | 148(24.4%) | 72(32.6%) | 63(29.7%) | |

| Marital status | <0.001* | |||

| Single | 168(27.7%) | 23(10.4%) | 23(10.9%) | |

| Married | 384(63.4%) | 166(75.1%) | 158(74.5%) | |

| Divorced/separated/widowed/other | 54 (8.9%) | 32(14.4%) | 40(18.8%) | |

| Working status | <0.001* | |||

| Full-time employment | 436(72.2%) | 154(71.0%) | 150(71.1%) | |

| Part-time employment | 69(11.4%) | 24(11.1%) | 23(10.9%) | |

| Student | 35(5.8%) | 2(0.9%) | 2(1.0%) | |

| Retired | 10(1.7%) | 14(6.5%) | 15(7.1%) | |

| Disabled/Other | 26(4.4%) | 6(2.7%) | 10(4.5%) | |

| Exercise | 0.2 | |||

| Aerobic activity ≥3 d/wk | 228(37.6%) | 87(39.7%) | 80(37.9%) | |

| Aerobic activity <3 d/wk | 72(11.9%) | 17(7.8%) | 15(7.1%) | |

| No regular aerobic activity | 307(50.6%) | 115(52.5%) | 116(55.0%) | |

| Family history of ADPKD | 524(86.0%) | 190(86.0%) | 189(88.7%) | 0.5 |

| Baseline eGFR | 84.7(18.3) | 52.4 (4.5) | 36.8 (5.3) | <.001* |

| TKV (mL) | 1198.0(711.1) (n=524) |

1821.0(1041.3) (n=15)^ |

--- | 0.002* |

| Height-adjusted TKV (mL/m) | 685.6(393.1) (n=512) |

1058.8(579.7) (n=15) |

--- | 0.002* |

| TLV (mL) | 1949.8(799.6) (n=530) |

2224.6(789.7) (n=16) |

--- | 0.09 |

| Height-adjusted TLV (mL/m) | 1119.7(457.4) (n=519) |

1330.1 (521.5) (n=15) |

--- | 0.04* |

Note: eGFRs expressed in mL/min/1.73 m2. Values for categorical variables are given as number (percentage); values for continuous variables, as mean ± standard deviation.

Abbreviations: eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate; TKV, total kidney volume; TLV, total liver volume;

ADPKD, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease

A small number of patients with baseline eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 underwent magnetic resonance imaging because their eGFR was above 60 mL/min at the screening visit (when study arm was assigned).

Pain and Effects on Daily Living Across eGFR Subgroups

Back pain was present in 51% of patients in the past 3 months, of whom 30% experienced it ‘sometimes’ and 21% experienced it ‘often, usually or always’ (Table 2). Back pain frequency over the past 3 months did not vary by eGFR subgroup in men or women. Abdominal pain was reported as ‘often, usually, or always’ by 14.6%, 11.2%, and 5.6% of men with eGFR of 20–44, 45–60, and >60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (p=0.05), respectively; there was no difference in women by eGFR subgroups. The intensity of back, radicular and abdominal pain on average or at their worst (data not shown) was also not associated with eGFR. Eighty of 450 (18%) subjects treated for pain were ‘completely or very dissatisfied’ with their physical ability to do what they wanted and this also did not vary by level of kidney function. Pain was, however, more likely to interfere with daily life among those with lower as compared with higher eGFR. More men with eGFR of 20–44 mL/min/1.73 m2 compared to men with 45–60 and >60 mL/min/1.73m2, respectively, reported that pain interfered moderately to extremely with work (14.0% vs. 3.8% vs. 10.2%; p=0.04), strenuous activity (25.5% vs. 14.2% vs. 14.3%; p=0.02), and social activities (12.5% vs. 1.9% vs. 7.5%; p=0.02). More women with eGFR of 20–44 mL/min/1.73 m2 reported moderate to extreme interference with walking due to pain than women with 45–60 and >60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (22.8% vs. 18.3% vs. 12.3%, respectively; p=0.03). Over the counter and prescription pain medications were not used with increased frequency among subjects with lower vs. higher eGFR. Women were more likely than men to experience pain, pain was more likely to interfere with daily activities, and use of pain medication was higher in women than men.

Table 2.

Pain and Impact on Daily Living Within the Past 3 Months by eGFR Level

| All (N=1043) |

Males (n=517) | Females (n=526) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eGFR>60 (n=303) |

eGFR 45–60 (n=108) |

eGFR 20–44 (n=106) |

All | p value ^ |

eGFR >60 (n=306) |

eGFR 45–60 (n=113) |

eGFR 20–44 (n=107) |

All | p value^ |

||

| Back pain frequency |

0.6 | 0.2 | |||||||||

| Never-rarely | 491(49.0%) | 155(54.0%) | 64(59.8%) | 54(52.4%) | 273(54.9%) | 138(47.1%) | 40(36.7%) | 40(38.8%) | 218(43.2 %) |

||

| Sometimes | 298(29.7%) | 85(29.6%) | 29(27.1%) | 28(27.2%) | 142(28.6%) | 83(28.3%) | 40(36.7%) | 33(32.0%) | 156(30.9 %) |

||

| Often-usually-always | 213(21.3%) | 47(16.4%) | 14(13.1%) | 21(20.4%) | 82(16.5%) | 72(24.6%) | 29(26.6%) | 30(29.1%) | 131(25.9 %) |

||

| Back pain intensity on average# |

2.0[1.0–3.0] (n=775) |

1.0(1.0–3.0) (n=218) |

2.0(1.0–3.0) (n=79) |

2.0(1.0–3.0) (n=80) |

2.0(1.0–3.0) (n=377) |

0.3b | 2.5(1.0–4.0) (n=222) |

2.0(1.0–4.0) (n=85) |

2.0(1.0–4.0) (n=91) |

2.0(1.0–4.0) (n=398) |

0.4b |

| Back pain associated with gross hematuria |

39(5.0%) | 12(5.5%) | 5(6.2%) | 4(4.9%) | 21(5.5%) | 0.9a | 10(4.5%) | 3(3.6%) | 5(5.5%) | 18(4.5%) | 0.8a |

| Radiculopathy frequency |

0.08 | 0.1 | |||||||||

| Never-rarely | 814(81.9%) | 244(85.3%) | 94(90.4%) | 88(86.3%) | 426(86.6%) | 229(79.0%) | 82(74.5%) | 77(75.5%) | 388(77.3 %) |

||

| Sometimes | 125(12.6%) | 29(10.1%) | 9(8.7%) | 14(13.7%) | 52(10.6%) | 39(13.5%) | 14(12.7%) | 20(19.6%) | 73(14.5%) | ||

| Often-usually-always | 55(5.5%) | 13(4.5%) | 1(1.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 14(2.8%) | 22(7.6%) | 14(12.7%) | 5(4.9%) | 41(8.2%) | ||

| Radicular pain intensity# on average |

3.0(1.0–5.0) (n=336) |

3.0(1.0–5.0) (n=84) |

2.0(1.0–3.0) (n=28) |

3.5(1.5–6.5) (n=32) |

3.0(1.0–5.0) (n=144) |

0.08b | 4.0(2.0–6.0) (n=105) |

4.0(1.0–7.0) (n=41) |

4.0(2.0–6.0 (n=46) |

4.0(2.0–6.0) (n=192) |

0.9b |

| Abdominal pain frequency |

0.05* | 0.8 | |||||||||

| Never-rarely | 716(72.0%) | 239(83.9%) | 85(79.4%) | 81(78.6%) | 405(81.8%) | 181(62.4%) | 70(64.2%) | 60(59.4%) | 311(62.2 %) |

||

| Sometimes | 160(16.1%) | 30(10.5%) | 10(9.3%) | 7(6.8%) | 47(9.5%) | 62(21.4%) | 25(22.9%) | 26(25.7%) | 113(22.2 %) |

||

| Often-usually-always | 119(12.0%) | 16(5.6%) | 12(11.2%) | 15(14.6%) | 43(8.7%) | 47(16.2%) | 14(12.8%) | 15(14.8%) | 76(15.2%) | ||

| Abdominal pain intensity# on average |

2.0(1.0–3.0) (n=480) |

2.0(1.0–3.0) (n=97) |

1.0(1.0–3.0) (n=39) |

2.0(1.0–3.0) (n=47) |

2.0(1.0–3.0) (n=183) |

0.4b | 2.0(1.0–3.0) (n=175) |

2.0(1.0–4.0) (n=56) |

2.0(1.0–4.0) (n=66) |

2.0(1.0–4.0) (n=297) |

0.9b |

| Treatment for pain | |||||||||||

| No treatment | 586(56.5%) | 195(64.6%) | 75(70.1%) | 66(62.9%) | 336(65.4%) | 0.4 | 147(48.4%) | 54(47.8%) | 49(46.2%) | 250(47.8 %) |

0.9 |

| OTC Medications |

305(29.4%) | 62(20.5%) | 26(24.3%) | 30(28.6%) | 118(23.0%) | 0.2 | 110(36.2%) | 39(34.5%) | 38(35.9%) | 187(35.8 %) |

0.9 |

| Prescription pain medications |

125(12.0%) | 28(9.3%) | 6(5.6%) | 11(10.5%) | 45(8.7%) | 0.4 | 40(13.2%) | 20(17.7%) | 20(18.9%) | 80(15.3%) | 0.2 |

| Acupuncture, heat or cold, massage therapy |

113(10.8%) | 23(7.6%) | 7(6.5%) | 6(5.7%) | 36(7.0%) | 0.8 | 45(14.7%) | 17(15.0%) | 15(14.0%) | 77(14.6%) | 0.9 |

| Surgical procedure |

4(0.4%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0%) | --- | 2(0.7%) | 0(0.0%) | 2(1.9%) | 4(0.8%) | 0.2a |

| Pain affected physical ability to do what you want to |

0.2 | 0.4 | |||||||||

| Completely/very dissatisfied |

80(17.8%) | 16(16.2%) | 9(25.7%) | 8(19.5%) | 33(18.9%) | 27(17.1%) | 10(17.2%) | 10(16.9%) | 47(17.1%) | ||

| Somewhat dissatisfied |

79(17.6%) | 13(13.1%) | 5(14.3%) | 12(29.3%) | 30(17.1%) | 23(14.6%) | 11(19.0%) | 15(25.4%) | 49(17.8%) | ||

| Somewhat satisfied |

96(21.3%) | 20(20.2%) | 6(17.1%) | 8(19.5%) | 34(19.4%) | 39(24.7%) | 9(15.5%) | 14(23.7%) | 62(22.5%) | ||

| Completely/very satisfied |

195(43.3%) | 50(50.5%) | 15(42.9%) | 13(31.7%) | 78(44.6%) | 69(43.7%) | 28(48.3%) | 20(33.9%) | 117(42.5 %) |

||

| Pain interfered moderately to extremely with: |

|||||||||||

| Mood | 159(16.0%) | 41(14.4%) | 8(17.5%) | 14(14.1%) | 63(12.9%) | 0.1 | 55(18.8%) | 19(17.4%) | 22(21.8%) | 96(19.1%) | 0.7 |

| Relations with others |

103(10.4%) | 22(7.7%) | 5(4.7%) | 8(8.0%) | 35(7.19%) | 0.5 | 41(14.0%) | 11(10.0%) | 16(15.8%) | 68(13.5%) | 0.4 |

| Walking ability | 120(12.1%) | 25(8.8%) | 4(3.8%) | 12(12.0%) | 41(8.4%) | 0.1 | 36(12.3%) | 20(18.3%) | 23(22.8%) | 79(15.7%) | 0.03 * |

| Sleep | 206(20.8%) | 48(16.9%) | 13(12.4%) | 19(19.2%) | 80(16.4%) | 0.4 | 70(23.9%) | 29(26.6%) | 27(26.7%) | 126(25.1 %) |

0.7 |

| Work | 129(13.1%) | 29(10.2%) | 4(3.8%) | 14(14.0%) | 47(9.6%) | 0.04* | 47(16.5%) | 15(13.9%) | 20(20.2%) | 82(16.7%) | 0.4 |

| Strenuous physical activity |

198(21.1%) | 38(14.2%) | 15(14.3%) | 25(25.5%) | 78(16.6%) | 0.02* | 60(22.4%) | 29(28.4%) | 31(32.3%) | 120(25.7 %) |

0.1 |

| Social activities or hobbies |

107(11.5%) | 20(7.5%) | 2(1.9%) | 12(12.5%) | 34(7.3%) | 0.02* | 43(16.0%) | 13(12.9%) | 17(18.1%) | 73(15.8%) | 0.6 |

| Enjoyment of life |

140(14.2%) | 34(12.0%) | 10(9.4%) | 13(13.1%) | 57(11.7%) | 0.6 | 41(14.1%) | 19(17.4%) | 23(22.8%) | 83(16.6%) | 0.1 |

Note: Note: eGFRs expressed in mL/min/1.73 m2. Values for categorical variables are given as number (percentage); values for continuous variables, as median [interquartile range], with numbers of participants with data indicated.

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; OTC, over the counter.

Pain Intensity Score is based on a visual analog scale with 0 as “No pain” and 10 as “Pain as bad as you can imagine”.

Significant p value of ≤0.05

P values across eGFR groups

Early Satiety and Abdominal Fullness Across eGFR Subgroups

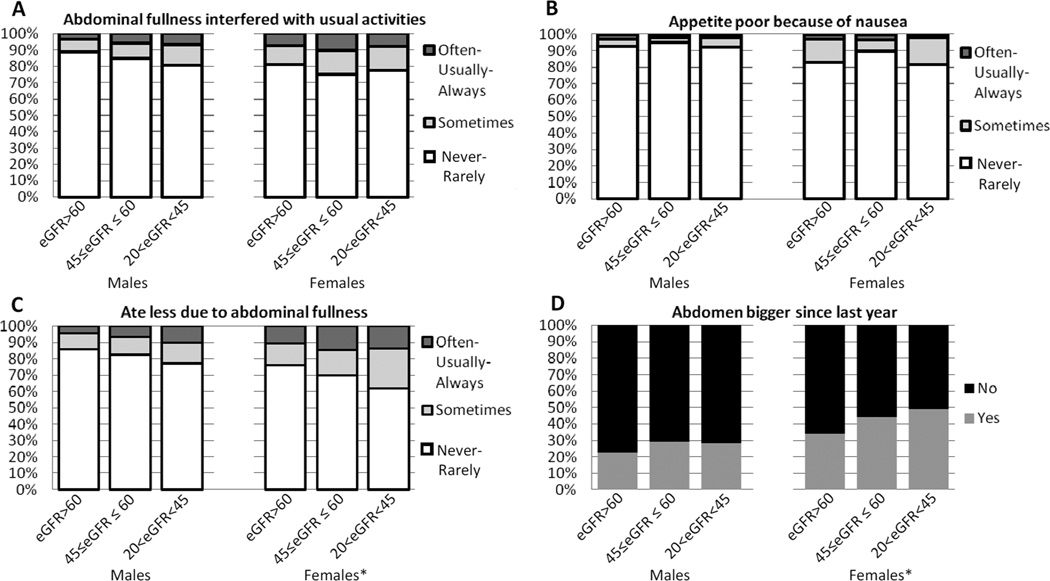

Approximately 20% of participants (varied across items) experienced symptoms relating to abdominal fullness (Figure 1A–D; Table S1, available as online supplementary material). Women experienced more abdominal fullness symptoms than men at all levels of eGFR. Women in the eGFR 20–44 mL/min/1.73 m2 subgroup were more likely than those in the 45–60 and >60 mL/min/1.73 m2 subgroups to report that their abdomens had gotten bigger in the past year (49.0%, 44.0% and 33.8%, respectively; p=0.01) and that they ate less “sometimes, often, usually or always”, due to abdominal fullness (39.2%, 30.3% and 24.2%, respectively; p=0.05). More men in the eGFR 20–44 mL/min/1.73 m2 subgroup as compared with the 45–60 and >60 mL/min/1.73 m2 subgroups reported that abdominal fullness interfered with usual activities ‘somewhat, often, usually or always’ (20.6%, 15.3%, and 11.1%, respectively; p=0.2) and early satiety (22.8%, 17.5% and 13.9%, respectively; p=0.2), but these differences did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 1. ADPKD patients’ reports of frequency of abdominal symptoms.

1A There were no statistically significant differences in the frequency at which abdominal fullness interfered with usual activities across eGFR strata in men or women. 1B Women with eGFR 20–44 mL/min/1.73 m2 were more likely than women with GFR 45–60 or >60 mL/min/1.73 m2 to report that they ate less due to abdominal fullness (p=0.05). No differences by eGFR were seen in men. *Significant p-value <0.05 when comparing across eGFR groups

1C There were no statistically significant differences in the frequency at which patients reported that their appetite was poor due to abdominal fullness across eGFR strata in men or women.

1D Women with eGFR 20–44 mL/min/1.73 m2 were more likely than women with eGFR 45–60 or >60 mL/min/ 1.73 m2 to report that their abdomen had gotten bigger over the past year (p=0.01). No differences by eGFR were seen in men.

*Significant p-value <0.05 when comparing across eGFR groups

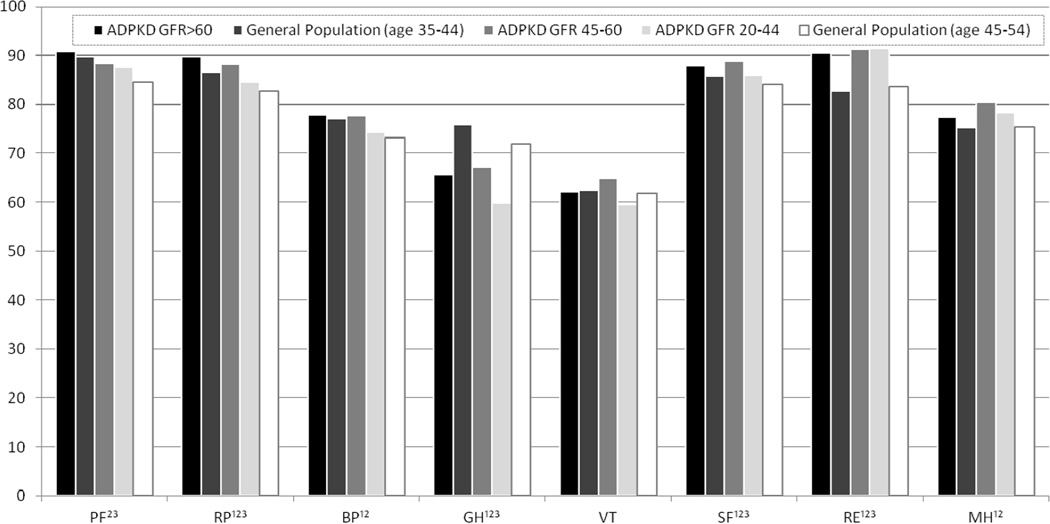

SF-36 Scores By eGFR

SF-36 scores were lower among patients with eGFR of 20–44 mL/min/1.73 m2 than among patients with higher eGFRs for Physical Functioning, Role Physical, General Health, Vitality, and the Physical Component Summary Scores (Table 3). Per Figure 2, SF-36 scores in ADPKD patients with eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2 were the same as or higher than their age-matched general population for all but the General Health domain. The same pattern was found for SF-36 scores among ADPKD patients with eGFR of 45–60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and 20–44 mL/min/1.73 m2 as compared with the age-matched general population.

Table 3.

SF-36 Scores by eGFR Level

| All (N=1043) | Males (n=517) | Females (n=526) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eGFR >60 (n=303) |

eGFR 45–60 (n=108) |

eGFR 20–44 (n=106) |

All | p value ^a |

eGFR >60 (n=306) |

eGFR 45–60 (n=113) |

eGFR 20–44 (n=107) |

All | p value^a |

||

| Physical functioning |

89.66 ± 17.99 (n=1032) |

91.57 (17.79) (n=301) |

90.66 (16.96) (n=105) |

90.13 (16.28) (n=105) |

91.09 (17.30) (n=511) |

0.03* | 90.14 (17.31) (n=303) |

86.23 (21.17) (n=113) |

85.04 (18.56) (n=105) |

88.27 (18.56) (n=521) |

0.0003* |

| Role-physical | 88.37 (21.19) (n=1026) |

91.31 (20.35) (n=300) |

91.65 (18.77) (n=104) |

88.16 (18.98) (n=104) |

90.74 (19.77) (n=508) |

0.006* | 88.18 (20.87) (n=302) |

85.04 (23.22) (n=112) |

80.89 (24.38) (n=104) |

86.04 (22.27) (n=518) |

0.002* |

| Bodily pain | 77.09 (21.85) (n=1029) |

80.44 (20.65) (n=300) |

82.98 (18.94) (n=105) |

77.24 (22.88) (n=105) |

80.30 (20.84) (n=510) |

0.2 | 75.27 (22.25) (n=301) |

72.83 (21.83) (n=113) |

71.28 (23.21) (n=105) |

73.93 (22.38) (n=519) |

0.1 |

| General health | 64.77 (19.92) (n=1032) |

66.90 (19.79) (n=301) |

67.76 (19.01) (n=105) |

62.00 (19.11) (n=105) |

66.07 (19.57) (n=511) |

0.05* | 64.35 (19.99) (n=303) |

66.58 (18.98) (n=113) |

57.69 (21.08) (n=105) |

63.49 (20.20) (n=521) |

0.004* |

| Vitality | 62.19 (19.63) (n=1030) |

64.42 (18.43) (n=300) |

68.51 (18.16) (n=105) |

64.40 (17.49) (n=105) |

65.26 (18.23) (n=510) |

0.04* | 59.81 (20.88) (n=302) |

61.67 (20.12) (n=113) |

54.64 (19.17) (n=105) |

59.17 (20.49) (n=520) |

0.01* |

| Social functioning | 87.69 (19.88) (n=1030) |

89.75 (18.91) (n=300) |

92.62 (15.76) (n=105) |

88.33 (18.20) (n=105) |

90.05 (18.18) (n=510) |

0.1 | 86.13 (21.07) (n=302) |

85.07 (21.77) (n=113) |

83.57 (20.90) (n=105) |

85.38 (21.17) (n=520) |

0.3 |

| Role-emotional | 90.84 (18.32) (n=1026) |

91.56 (17.66) (n=299) |

93.02 (14.67) (n=105) |

92.94 (14.74) (n=105) |

92.14 (16.49) (n=509) |

0.8 | 89.31 (19.73) (n=300) |

89.82 (21.21) (n=113) |

89.98 (19.09) (n=104) |

89.56 (19.90) (n=517) |

0.4 |

| Mental health | 78.27 (14.69) (n=1030) |

78.44 (14.18) (n=300) |

81.43 (14.10) (n=105) |

78.81 (14.84) (n=105) |

79.13 (14.32) (n=510) |

0.1 | 76.44 (15.61) (n=302) |

79.53 (14.94) (n=113) |

77.98 (13.02) (n=105) |

77.42 (15.00) (n=520) |

0.06 |

| PCS | 51.33 (7.88) (n=1028) |

52.70 (7.28) (n=300) |

52.58 (7.33) (n=105) |

50.87 (7.34) (n=105) |

52.29 (7.32) (n=510) |

0.02* | 51.45 (7.85) (n=301) |

49.85 (8.05) (n=113) |

47.87 (9.24) (n=104) |

50.38 (8.30) (n=518) |

<0.001* |

| MCS | 51.39 (8.90) (n=1028) |

51.58 (8.26) (n=300) |

53.48 (7.85) (n=105) |

52.23 (7.72) (n=105) |

52.11 (8.09) (n=510) |

0.07 | 50.18 (9.81) (n=301) |

51.78 (10.02) (n=113) |

50.92 (8.38) (n=104) |

50.68 (9.59) (n=518) |

0.02* |

Note: eGFRs expressed in mL/min/1.73 m2. Values are given as mean ± standard deviation, with numbers of participants with data indicated.

PCS, physical component summary; MCS, mental component summary; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; SF-36, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey.

P value across eGFR groups

Significant p-value

Kruskal-Wallis test

Wilcoxon test

Figure 2. SF-36 Scores in ADPKD Patients Compared with Age-Matched Healthy Controls.

SF-36 scores in ADPKD patients with eGFR>60 mL/min/1.73 m2 were the same as or higher than their age-matched general population for all but GH. The same pattern was found for SF-36 scores among ADPKD patients with eGFR 45–60 and 20–44 mL/min/1.73 m2 as compared with the age-matched general population. Abbreviations: PF physical functioning; RP role physical; BP bodily pain; GH general health; VT vitality; SF social functioning; RE role emotional; MH mental health

1 significant difference between general population (age 35–44 y) and ADPKD GFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2 population

2 significant difference between general population (age 45–54 y) and ADPKD eGFR 45–60 mL/min/1.73 m2 population

3significant difference between general population (age 45–54 y) and ADPKD eGFR 20–44 mL/min/1.73 m2 population

^ General population scores are based on respondents of the 1989 and 1990 General Social Survey (GSS), conducted by the National Opinion Research Center [14]

Relationship of htTKV With Pain and Effects on Daily Living in Early Disease

Among patients with eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2, htTKV was not related to the frequency or intensity of back, abdominal or radicular pain in females or males (Table S2). A relatively large proportion of patients reported that pain interfered with mood (17%), relations with others (11%), walking ability (11%), sleep (20%), work (13%), strenuous physical activity (18%), social activities (12%) and enjoyment of life (13%), although htKTV was not higher among those reporting these interferences as compared with those who did not. Findings were consistent in males and females.

There were 101 of 540 (19%) patients with eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and htTKV >1000 mL/m, 70% of whom were male. We found that more of these patients reported back pain in the past 3 months than in the full population with eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2, although a sizable proportion (approximately40%) never or rarely experienced it. As shown in Table 4, htTKV was greater in patients experiencing more frequent back pain (1373 vs. 1167 mL/m for ‘often-always’ vs. ‘never-rarely’, resepectively; p=0.08), greater intensity of back pain (1349 vs. 1073 mL/m2 for ‘3’ vs. ‘0’ pain on a Likert scale, respectively; p=0.03), and/or who reported that pain interfered moderately to extremely with their mood (1471 vs. 1246 mL/m for ‘yes’ vs. ‘no’, respectively; p=0.007) and/or relations with others (1496 vs. 1282 mL/m for ‘yes’ vs. ‘no’, respectively; p=0.02) than those who do not have these symptoms or interferences. For other pain questions, patients experiencing greater pain or pain impact had greater htTKV, but these findings were not statistically significant.

Table 4.

Median htTKV Values by Pain Survey Responses in Particpants with eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73m2 and htTKV >1000 mL/m

| All (N=101) | Males (n=70) | Females (n=31) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Median htTKV (mL/m) |

p | n (%) | Median htTKV (mL/m) |

p | n (%) | Median htTKV (mL/m) |

p | |

| Back pain frequency | 0.08 | 0.7 | 0.04* | ||||||

| Never-rarely | 41 (42.3%) | 1167 | 27 (40.9%) | 1296 | 14 (45.2%) | 1111 | |||

| Sometimes | 34 (35.1%) | 1330 | 26 (39.4%) | 1316 | 8 (25.8%) | 1371 | |||

| Often-usually-always | 22 (22.7%) | 1373 | 13 (19.7%) | 1365 | 9 (29.0%) | 1496 | |||

| Back pain Intensity on average | 0.03* | 0.04* | 0.3 | ||||||

| 0 | 8 (11.0%) | 1073 | 8 (15.4%) | 1073 | 0 (0.00%) | --- | |||

| 1–2 | 37 (50.7%) | 1305 | 31 (59.6%) | 1327 | 6 (28.6%) | 1134 | |||

| ≥3 | 28 (38.4%) | 1349 | 13 (25.0%) | 1318 | 15 (71.4%) | 1380 | |||

| Radiculopathy frequency | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.7 | ||||||

| Never-rarely | 74 (77.9%) | 1242 | 49 (76.6%) | 1282 | 25 (80.7%) | 1167 | |||

| Sometimes | 14 (14.7%) | 1363 | 11 (17.2%) | 1360 | 3 (9.7%) | 1443 | |||

| Often-usually-always | 7 (7.4%) | 1318 | 4 (6.3%) | 1367 | 3 (9.7%) | 1315 | |||

| Abdominal pain frequency | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.1 | ||||||

| Never-rarely | 73 (75.3%) | 1296 | 53 (80.3%) | 1326 | 20 (64.5%) | 1112 | |||

| Sometimes | 16 (16.5%) | 1314 | 10 (15.2%) | 1289 | 6 (19.4%) | 1356 | |||

| Often-usually-always | 8 (8.3%) | 1587 | 3 (4.6%) | 1381 | 5 (16.1%) | 1793 | |||

| Abdominal pain Intensity on Average | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.08 | ||||||

| 0 | 5 (10.9%) | 1282 | 5 (19.2%) | 1282 | 0 (0.0%) | --- | |||

| 1–2 | 24 (52.2%) | 1336 | 13 (50.0%) | 1427 | 11 (55.0%) | 1167 | |||

| ≥3 | 17 (37.0 %) | 1380 | 8 (30.8%) | 1373 | 9 (45.0%) | 1380 | |||

| Medications for Pain | |||||||||

| OTC Pain Medications | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.3 | ||||||

| No | 75 (75.0%) | 1296 | 52 (75.4%) | 1300 | 23 (74.2%) | 1171 | |||

| Yes | 25 (25.0%) | 1340 | 17 (24.6%) | 1340 | 8 (25.8%) | 1310 | |||

| Prescription pain medications | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.09 | ||||||

| No | 93 (93.0%) | 1296 | 64 (92.8%) | 1307 | 29 (93.55%) | 1171 | |||

| Yes | 7 (7.0%) | 1381 | 5 (7.3%) | 1305 | 2 (6.45%) | 1801 | |||

| Acupuncture, heat or cold, massage | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.3 | ||||||

| No | 87 (86.1%) | 1282 | 61 (87.1%) | 1296 | 26 (83.9%) | 1169 | |||

| Yes | 14 (13.9%) | 1339 | 9 (12.9%) | 1318 | 5 (16.1%) | 1443 | |||

| Pain affected physical ability to do what You want to^ |

0.9 | 0.5 | 0.8 | ||||||

| Completely/very satisfied | 13 (31.7%) | 1222 | 6 (21.43%) | 1212 | 7 (53.85%) | 1332 | |||

| Somewhat satisfied | 12 (29.3%) | 1297 | 10 (35.71%) | 1297 | 2 (15.38%) | 1417 | |||

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 6 (14.6%) | 1317 | 4 (14.29%) | 1367 | 2 (15.38%) | 1243 | |||

| Completely/very dissatisfied | 10 (24.4%) | 1354 | 8 (28.57%) | 1354 | 2 (15.38%) | 1406 | |||

| Pain interfered moderately to extremely with: |

|||||||||

| Mood | 0.007* | 0.1 | 0.02* | ||||||

| No | 78 (81.3%) | 1246 | 54 (83.1%) | 1296 | 24 (77.4%) | 1130 | |||

| Yes | 18 (18.8%) | 1471 | 11 (16.9%) | 1446 | 7 (22.6%) | 1496 | |||

| Relations with others | 0.02* | 0.4 | 0.02* | ||||||

| No | 85 (88.5%) | 1282 | 61 (93.9%) | 1305 | 24 (77.4%) | 1130 | |||

| Yes | 11 (11.5%) | 1496 | 4 (6.2%) | 1596 | 7 (22.6%) | 1496 | |||

| Walking ability | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.2 | ||||||

| No | 84 (87.5%) | 1303 | 57 (87.7%) | 1326 | 27 (87.1%) | 1167 | |||

| Yes | 12 (12.5%) | 1310 | 8 (12.3%) | 1300 | 4 (12.9%) | 1405 | |||

| Sleep | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.09 | ||||||

| No | 74 (77.1%) | 1296 | 49 (75.4%) | 1326 | 25 (80.6%) | 1167 | |||

| Yes | 22 (22.9%) | 1338 | 16 (24.6%) | 1269 | 6 (19.4%) | 1618 | |||

| Work | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.08 | ||||||

| No | 81 (84.4%) | 1282 | 55 (84.6%) | 1296 | 26 (83.9%) | 1153 | |||

| Yes | 15 (15.6%) | 1360 | 10 (15.4%) | 1339 | 5 (16.1%) | 1496 | |||

| Strenuous physical activity | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.1 | ||||||

| No | 73 (82.0%) | 1259 | 49 (80.3%) | 1318 | 24 (85.7%) | 1130 | |||

| Yes | 16 (18.0%) | 1332 | 12 (19.7%) | 1332 | 4 (14.3%) | 1485 | |||

| Social activities or hobbies | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | ||||||

| No | 83 (91.2%) | 1259 | 57 (91.9%) | 1296 | 26 (89.7%) | 1153 | |||

| Yes | 8 (8.8%) | 1371 | 5 (8.1%) | 1381 | 3 (10.3%) | 1315 | |||

| Enjoyment of life | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.09 | ||||||

| No | 80 (86.0%) | 1289 | 54 (84.4%) | 1315 | 26 (89.7%) | 1153 | |||

| Yes | 13 (13.9%) | 1318 | 10 (15.6%) | 1307 | 3 (10.3%) | 1793 | |||

Note: P value is for difference in htTKV between categories.

eGFR, estimated glomerular filatrion rate; ht-TKV, height-adjusted total kidney volume. OTC, over-the-counter.

This question is filled out only by subset of subjects who reported they required treatment for pain in prior question.

Significant p value

Relationship of htTKV With Symptoms of Abdominal Fullness in Early Disease

In early disease (eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2), htTKV was higher (1011 mL/m) among men reporting that abdominal fullness interfered ‘often, usually or always’ with usual activities and eating, as compared with those reporting less (624.2 mL/m) or no interference (692.6 mL/m), but the number of severely affected men was small and the differences were not statistically significant (Table S3). No associations were found between htTKV and symptoms relating to abdomen fullness in women with eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2. When restricted to the individuals with htTKV>1000 mL/m, there were no differences in statistical significance of relationships of htTKV and abdominal fullness symptoms from those shown in the full population with eGFR>60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (data not shown).

Relationship of TLV With Pain and Abdominal Fullness in Early Disease

There were 69 of 540 (13%) patients with eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and total liver volume (TLV) >2500 mL, 34 (49%) of whom were female. We found no relationship of TLV with responses to pain items in these patients (data not shown). Similarly there were no differences in the relationship of TLV with abdominal mass symptoms (data not shown), from those found with htTKV (Table S3) with the exception that for “ate less due to abdominal fullness” in males, there was a statistically significant relationship of increasing TLV (p=0.03), while it was borderline significant with htTKV (p=0.06).

Correlation of htTKV With SF-36 Scores in Early Disease

Correlations between htTKV values and SF-36 domain scores were weak and none were statistically significant within men or women with eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (Table S4).

Discussion

This is to our knowledge the largest comprehensive study of the experiences in daily living among individuals with ADPKD and eGFR >20 mL/min/1.73 m2, with comparisons across htTKV and eGFR levels. As has been previously reported, pain is common and, even early in disease (eGFR>60 mL/min/1.73 m2), pain affects a relatively high proportion of patients with basic activities, such as walking (11%) and sleep (20%). However, we found that pain is not related to kidney size in early disease, except in individuals with the largest kidneys (htTKV >1000 mL/m). Our findings show that pain interferes with daily activities more in patients with eGFR <45 mL/min/1.73 m2 as compared with patients at higher eGFR levels. Moreover, we observed that symptoms relating to abdominal fullness are greater among subjects at lower vs. higher eGFR levels, but this was statistically significant only in women. The implication of these findings for research is that a minimum htTKV should be part of the eligibility criteria for clinical trials testing cyst-reducing therapies in early disease, as effects on pain and HRQoL will be more likely to be found in patients with larger kidneys. Both pain and symptoms of abdominal fullness are correlated with eGFR at lower eGFR levels (20–44 mL/min/1.73 m2). If organ enlargement is the reason for these symptoms, then a therapy that reduces cyst growth, if applied early enough in the course of disease, may reduce the later development of these symptoms.

The absence of a strong association between kidney size and pain in early disease is unexpected, but is consistent with a prior study that showed no relationship of TKV with SF-36 bodily pain scores in a cohort of individuals with a mean eGFR of 65.1±33.1 mL/min/1.73 m2 [3]. One possible explanation for this is that cyst size and location is more important than the total number of cysts or total kidney size in causing pain. It is also possible that more patients experience pain, but do not recognize it until after they have had cyst reduction surgeries. Our study includes nearly 500 individuals with eGFR <60 mL/ min/ 1.73 m2 who would be expected to have a higher htTKV than those represented in the prior study, given the strong inverse correlation between eGFR and TKV [7, 16, 17]. We still do not find a strong relationship of disease stage (defined by eGFR) with patients’ report of pain frequency at eGFR <60 mL/min/ 1.73 m2, although we observed an increase in reported interference by pain on daily activities in subjects with eGFR of 20–44 vs. 45–60 and >60 mL/min/1.73 m2. This might suggest that patients are restricting their activities, but they do not realize that it is because of pain. We believe that the increase in interference with daily activities with lower eGFR is a reflection of symptoms due to organ enlargement (pain + abdominal fullness symptoms) and is an extension of the relationship of htTKV and pain found in the patients with early disease (eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2) and htTKV >1000 mL/m. Another possible explanation, other than organ enlargement, is that a patient’s ability to cope with pain or abdominal fullness symptoms is reduced because of older age and/or reduced kidney function.

The finding of a relationship of abdominal fullness symptoms with lower eGFR in females but not males may be due to larger liver size in females, which has been previously observed and is attributed to estrogen responsiveness of liver cysts [8]. Unfortunately, we cannot confirm this hypothesis as liver volumes were not measured in subjects with eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2. That the enlarged organs as opposed to reduced kidney function are the cause of symptoms is supported by studies that show dramatic relief of symptoms and improvement in HRQoL after organ reduction therapy or removal [19–22]. Even modest reductions in liver volume (4.95% ± 6.77%) with one-year treatment with octreotide in a blinded study, led to improvements in bodily pain and role emotional scales of the SF-36 [23]. More recently, a large randomized trial involving patients with eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2 has shown that treatment with tolvaptan was associated with a significant reduction in the rate of htTKV growth (2.8% vs. 5.5% per year) and episodes of severe pain (defined by need for hospitalization, narcotics or surgical intervention) [6]. The prevalence of less severe pain and quality of life at baseline or in response to treatment (to compare with this study) were not reported.

Our study would suggest that at the stages of disease represented here (largely CKD stages 1–3), most patients have symptoms but they do not greatly interfere with daily living. The absence of an effect on HRQoL, despite the high frequency of pain, suggests that in most patients these symptoms are mild or that patients have a tremendous resilience to adapt to their physical discomfort. This may be because they are comparing themselves to their family members with ADPKD who are on dialysis or have died, and thus view their current life circumstances favorably relative to them. The experience among individuals with CKD stage 4, which is not well represented here, and beyond, has not been systematically studied. Case reports of patients referred for organ reduction therapies or removal (most of whom have reached ESRD) indicate a high degree of morbidity from the enlarged organs including reduced mobility, imbalance , dyspnea, and progressive anorexia[21, 22]. The number of patients who experience severe morbidity and have not reached the need for renal replacement therapy is unknown, as we do not have large studies of the natural history, but, if significant, would justify a medical therapy that reduced cyst growth even if it had no effect on the rate of kidney function decline.

A final observation that warrants brief comment is the finding that females had more pain and reported greater interference with daily life than males for almost all of the pain questionnaire items. Numerous studies have shown differences in pain perception across genders exposed to the same painful stimulus, with results showing pain tolerance is greater in men[24, 25]. An alternate explanation is that women actually experience more pain and abdominal fullness symptoms, which may again be due to larger total organ mass (liver + kidney). Another possibility is that symptoms experienced with monthly menstrual cycles (bloating, cramps, pain), may be heighted by the presence of enlarged ADPKD organs.

A major limitation of this study is that it is based on participants of a clinical trial who may not be representative of the ADPKD population at large. Prior kidney cyst reduction surgery was an exclusion criterion and patients with pain and debility generally do not involve themselves in clinical trials, particularly where travel is involved. Thus, these results may underestimate the true incidence of pain. We did not have TKV or TLV measurements in subjects with eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and thus, we are unable to be certain whether the increase in abdominal fullness symptoms and pain interference at lower vs. higher eGFR level is due to organ enlargement. The pain questionnaire used in this study has not been previously validated in an ADPKD population. If this instrument lacks reliability and validity in this population, stronger relationships of pain with htTKV and eGFR may exist than were reported here. Patients who did not speak English were not enrolled in the study, thus these results may not generalize to non-English speaking patients. The cohort largely represents patients with early disease. Individuals with eGFR <20 mL/min/1.73 m2 including patients who have reached ESRD are excluded from this study and it is likely that much more significant morbidity is seen in these patients. Finally, the cross-sectional nature of the data precludes making causal inferences.

In conclusion, in subjects with early disease (GFR >60 mL/min/ 1.73 m2) pain is common, although it is not related to htTKV, except at htTKV >1000 mL/m. Symptoms relating to abdominal fullness were greater among patients with reduced eGFR, especially women, and may be related to organ enlargement. Further studies, with measurement of htTKV and htTLV in people with eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2, are needed to better understand the role of organ enlargement in ADPKD with symptoms and HRQoL.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The HALT-PKD Study Team Members are as follows: Theodore Steinman, MD, Jesse Wei, MD, Peter Czarnecki, MD (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center); William Braun, MD, Saul Nurko, MD, Erick Remer, MD (Cleveland Clinic Foundation); Arlene Chapman, MD, Diego Martin, MD PhD, Frederic Rahbari-Oskoui, MD, MS (Emory University); Vicente Torres, MD, PhD, Marie C. Hogan, MD, PhD, Peter Harris, PhD, James Glockner, MD, PhD, Bernard King Jr, MD (Mayo Clinic); Ronald Perrone, MD, Neil Halin, DO, Dana Miskulin, MD (Tufts Medical Center); Robert Schrier, MD, Godela Brosnahan, MD (University of Colorado); Franz Winklhofer, MD, Jared Grantham, MD, Connie Wang, MD, Louis Wetzel, MD (University of Kansas Medical Center); Charity Moore, PhD, MSPH, Kyongtae Bae, MD, Kaleab Abebe, PhD (University of Pittsburgh); Josephine Briggs, MD, Michael Flessner, MD, Robert Star, MD (National Institutes of Health [NIH]).

The HALT-PKD Study Group is indebted to the study participants for taking part in the study, the Research Program Coordinators and Program Managers at Washington University (Gigi Flynn and Robin Woltman) and University of Pittsburgh (Susan Spillane and Patty Smith), and the study coordinators at the clinical centers (Darlene Baker, Sabira Bacchus, Julie Driggs, Maria Fishman, Stacie Hitchcock, Andee Jolley, Pamela Lanza, Bonnie Maxwell, Pamela Morgan, Kristine Otto, Heather Ondler, Linda Perkins, Gertrude Simon, Rita Spirko, Veronika Testa, and Diane Watkins) who make this research possible.

Support: This study was supported by cooperative agreements (grants DK62408, DK62401, DK62410, DK62402, and DK62411) with the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH, the National Center for Research Resources General Clinical Research Centers (RR000039 Emory University, RR00585 Mayo Clinic, RR000054 Tufts University, RR000051 University of Colorado, RR23940 Kansas University, and RR024296 Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center), and the Centers for Translational Science Activities at the participating institutions (RR025008 Emory University, RR024150 Mayo Clinic, RR025752 Tufts University, RR025780 University of Colorado, and RR024989 Cleveland Clinic). Support for the study enrollment phase was also provided by grants to the Publications and Communications Committees from the PKD Research Foundation. Study drugs were donated by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc (telmisartan and placebo) and Merck & Co Inc (lisinopril).

Financial Disclosure: Dr Torres is an investigator and Chair of the Steering Committee for several Otsuka studies on ADPKD, is an investigator in a clinical trial for ADPKD sponsored by Novartis Pharmaceuticals, and has served as consultant for Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Hoffman-La Roche Inc, and Primrose Therapeutics. Drs Perrone and Chapman are each an investigator and member of the Steering Committee for several Otsuka studies on ADPKD. The other authors declare that they have no other relevant financial interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

N SECTION: Because a quorum could not be reached after those editors with potential conflicts recused themselves from consideration of this manuscript, the peer-review and decision-making processes were handled entirely by an Associate Editor (Kamyar Kalantar-Zadeh, MD, MPH, PhD) who served as Acting Editor-in-Chief. Details of the journal’s procedures for potential editor conflicts are given in the Editorial Policies section of the AJKD website.

Supplementary Material

Table S1: Symptoms of abdominal fullness in past 3 months by eGFR.

Table S2: htTKV values by pain survey responses in participants with eGFR >60.

Table S3: htTKV values and symptoms of abdominal fullness in participants with eGFR >60.

Table S4: Spearman correlations of SF-36 with htTKV overall and by sex.

Note: The supplementary material accompanying this article (doi:______) is available at www.ajkd.org

References

- 1.Gabow PA. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. New Engl J Med. 1993;329(5):332–342. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307293290508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Granthum JJ, Chapman AB, T VE. Volume Progression in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease: The Major Factor Determining Clinical Outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:148–157. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00330705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bajwa ZH, Gupta S, Warfield CA, S TI. Pain management in polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2001;60(5):1631–1644. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grantham JJ, Torres VE, Chapman AB, Guay-Woodford LM, Bae KT, King BF, Wetzel LH, Baumgarten DA, Kenney PJ, Harris PC, Klahr S, Bennett WM, Hirschman GN, Meyers CM, Zhang X, Zhu F, Miller JP. Volume progression in polycystic kidney disease. New Engl J Med. 2006;354(20):2122–2130. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Serra AL, Poster D, Kistler AD, Krauer F, Raina S, Young J, Rentsch KM, Spanaus KS, Senn O, Kristanto P, Scheffel H, Weishaupt D, W RP. Sirolimus and Kidney Growth in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. New Engl J Med. 2010;363:820–829. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torres VE, Chapman AB, Devuyst O, Gansevoort RT, Grantham JJ, Higashihara E, Perrone RD, Krasa HB, Ouyang J, Czerwiec FS. Tolvaptan in Patients with Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. New Engl J Med. 2012;367:2407–2418. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapman AB, Bost JE, Torres VE, Guay-Woodford LM, Bae KT, Landsittel D, Li J, King BF, DIego M, Wetzel LH, Lockhart ME, Harris PC, Moxey-Mimms M, Flessner M, Bennett WM, Grantham JJ. Kidney Volume and Functional Outcomes in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(3):479–486. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09500911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bae KT, Zhu F, Chapman AB, Torres VE, Grantham JJ, Guay-Woodford LM, Baumgarten DA, King BF, Wetzel LH, Kenney PJ, Brummer ME, Bennett WM, Klahr S, Meyers CM, Zhang X, Thompson PA, Miller JP. Magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of hepatic cysts in early autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease: the Consortium for Radiologic Imaging Studies of Polycystic Kidney Disease cohort. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(1):64–69. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00080605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bajwa ZH, Sial KA, Malik AB, Steinman TI. Pain patterns in patients with polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2004;66(4):1561–1569. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heiwe S, Bjuke M. "An evil heritage": interview study of pain and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Pain Management Nursing. 2009;10(3):134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hogan MC, Norby SM. Evaluation and management of pain in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Advances in Chronic Kidney Disease. 2010;17(3):e1–e16. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rizk D, J C, Veledar E, Bagby S, Baumgarten DA, Rahbari-Oskoui F, Steinman T, Chapman AB. Quality of life in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease patients not yet on dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:560–566. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02410508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chapman AB, Torres VE, Perrone RD, Steinman TI, Bae KT, Miller JP, Miskulin DC, Rahbari Oskoui F, Masoumi A, Hogan MC, Winklhofer FT, Braun W, Thompson PA, Meyers CM, Kelleher C, Schrier RW. The HALT polycystic kidney disease trials: design and implementation. Clinical Journal of The American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2010;5(1):102–109. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04310709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey: manual and interpretation guide. Lincoln, RI: Quality Metric Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain Assessment: Global Use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Annals of Acad Med. 1994;23:129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fick-Brosnahan G, Belz M, McFann K, Johnson A.a, Schrier R. Relationship between renal volume growth and renal function in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a longitudinal study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:1127–1134. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.33379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King BF, Reed JE, Bergstralh EJ, Sheedy PF, Torres VE. Quantification and longitudinal trends of kidney, renal cyst, and renal parenchyma volumes in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:1505–1511. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1181505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med.Care. 1992;30(6):473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schnelldorfer T, Torres VE, Zakaria S, Rosen CB, Nagorney DM. Polycystic liver disease: a critical appraisal of hepatic resection, cyst fenestration, and liver transplantation. Annals of Surgery. 2009;250(1):112–118. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181ad83dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ubara Y. New therapeutic option for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease patients with enlarged kidney and liver. Ther Apher Dial. 2006;10(4):333–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-9987.2006.00386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee DI, Andreoni CR, Rehman J, Landman J, Ragab M, Yan Y, Chen C, Shindel A, Middleton W, Shalhav A, McDougall EM, Clayman RV. Laparoscopic cyst decortication in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: impact on pain, hypertension, and renal function. J Endourol. 2003;17(6):345–354. doi: 10.1089/089277903767923100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takei R, Ubara Y, Hoshino J, Higa Y, Suwabe T, Sogawa Y, Nomura K, Nakanishi S, Sawa N, Katori H, akemoto FT, Hara S, Takaichi K. Percutaneous transcatheter hepatic artery embolization for liver cysts in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49(6):744–752. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hogan MC, Masyuk TV, Page LJ, Kubly VJ, Bergstralh EJ, Li X, Kim B, King BF, Glockner J, Holmes DRr, Rossetti S, Harris PC, LaRusso NF, Torres VE. Randomized clinical trial of long-acting somatostatin for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney and liver disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010:1052–1061. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009121291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goolkasian P. Phase and sex effects in pain perception: a critical review. Psychol Women Q. 1985;9:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Otto MW, Dougher MJ. Sex differences and personality factors in responsivity to pain. Percept Mot Skills. 1985;61:383–390. doi: 10.2466/pms.1985.61.2.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.