Abstract

Background

Uncomplicated skin and soft tissue infections are among the most frequent indications for outpatient antibiotics. A detailed understanding of current prescribing practices is necessary to optimize antibiotic use for these conditions.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study of children and adults treated in the ambulatory care setting for uncomplicated cellulitis, wound infection, or cutaneous abscess between March 1, 2010 and February 28, 2011. We assessed the frequency of avoidable antibiotic exposure, defined as: use of antibiotics with broad gram-negative activity, combination antibiotic therapy, or treatment for 10 or more days. Total antibiotic-days prescribed for the cohort were compared to antibiotic-days in four hypothetical short-course (5 – 7 days), single-antibiotic treatment models consistent with national guidelines.

Results

364 cases were included for analysis (155 cellulitis, 41 wound infection, and 168 abscess). Antibiotics active against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus were prescribed in 61% of cases of cellulitis. Of 139 cases of abscess where drainage was performed, antibiotics were prescribed in 80% for a median of 10 (interquartile range 7 – 10) days. Of 292 total cases where complete prescribing data were available, avoidable antibiotic exposure occurred in 46%. This included use of antibiotics with broad gram-negative activity in 4%, combination therapy in 12%, and treatment for 10 or more days in 42%. Use of the short-course, single-antibiotic treatment strategies would have reduced prescribed antibiotic-days by 19 – 55%.

Conclusions

Nearly half of uncomplicated skin infections involved avoidable antibiotic exposure. Antibiotic use could be reduced through treatment approaches utilizing short courses of a single antibiotic.

Keywords: skin and soft tissue infection, cellulitis, abscess, uncomplicated skin and soft tissue infection, antimicrobial stewardship

Introduction

Antibiotic prescribing in the community is associated with antimicrobial resistance1–3 and adverse events.4,5 Prevention of unnecessary antibiotic use for common outpatient infections is therefore an essential component of efforts to prevent further antimicrobial resistance and improve patient safety. Uncomplicated skin and soft tissue infections such as cellulitis and cutaneous abscess are among the most frequent indications for outpatient antibiotic use. With the widespread emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) over the past decade, ambulatory care visits for skin infections have rapidly increased and now exceed 14 million visits per year.6,7

Despite the burden of skin infections on the health care system and their contribution to overall antibiotic use, knowledge of current antibiotic prescribing practices is incomplete. Additional details of antibiotic selection and duration of therapy for the various types of uncomplicated skin infection are necessary to develop interventions to optimize prescribing. We previously demonstrated that use of overly broad-spectrum antibiotic regimens and prolonged treatment durations were common in patients hospitalized with cellulitis and cutaneous abscess.8,9 However, the vast majority of skin infections are managed in the ambulatory setting. Our hypothesis was that, similar to hospitalized patients, a substantial amount of antibiotic exposure for outpatient skin infections is avoidable. The objectives of this study were to describe antibiotic prescribing practices in cases of uncomplicated skin and soft tissue infection in a large ambulatory care system and assess for opportunities to reduce antibiotic use.

Methods

Study setting and population

Denver Health is a vertically-integrated public safety net institution. Adults and children can access care at multiple sites including a 500-bed teaching hospital, emergency department, urgent care center, 8 federally qualified community health clinics, 16 school-based clinics, specialty clinics, and the public health department.10 The entire Denver Health system is served by a single laboratory and a unified electronic health record that contains both inpatient and outpatient records.

Study design

We performed a retrospective cohort study of adults and children presenting to the emergency department, urgent care center, or any outpatient clinic in the Denver Health system with a primary diagnosis of skin and soft tissue infection between March 1, 2010 and February 28, 2011. International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes (680, 681, 682, 683, 686, 035) were used to identify eligible cases. For patients with multiple infections during the study period, only the initial episode was included. Manual chart review was performed on a random sample of cases for diagnostic, treatment, and outcomes data using a standardized data collection instrument.

Patients less than 31 days or greater than 89 years old were excluded. Cases involving the following complicating factors were excluded: hospitalization at the time of the initial visit or within 30 days prior, deep tissue involvement, periorbital or perineal infection, presence of another infection requiring antibiotic therapy, infected ulcer, peripheral arterial disease, bacteremia, human or animal bite, recurrence of a skin infection treated within 90 days, post-surgical wound infection, and pregnancy. Cases were also excluded that involved superficial infection such as folliculitis or impetigo, odontogenic infection, miscoding, lack of sufficient medical record documentation to classify the case, and leaving against medical advice. All clinical encounters within a 30-day period following the initial visit were reviewed to assess outcomes. The study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Outcome measures and study definitions

Using clinical documentation at the initial visit, cases were categorized into three groups: (1) cellulitis, defined as a diffuse skin infection characterized by spreading areas of redness, edema, and/or induration without a draining wound; (2) wound infection, defined as drainage from a wound with surrounding redness, edema, and/or induration; and (3) cutaneous abscess, defined as a collection of pus within the dermis or deeper accompanied by redness, edema, and/or induration.11 A subset of cases of abscess were considered candidates for drainage without antibiotic therapy based on Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidance,12 including those where adequate drainage was achieved and the absence of: hand or face involvement, multiple foci of infection, diabetes mellitus, HIV infection, use of immunosuppressing medications, temperature >38.0 degrees Celsius, and age <3 or >75 years.

Details of antibiotic treatment were obtained from provider documentation, medication lists, or pharmacy prescription fill data. Prescribing data were recorded based on the provider’s intent at the initial visit, irrespective of patient adherence to the treatment. The primary endpoint was the frequency of avoidable antibiotic exposure, defined as: (1) use of antibiotics with a broad spectrum of gram-negative activity; (2) combination antibiotic therapy; and (3) treatment for 10 or more days. The primary endpoint analysis was limited to cases with complete documentation of antibiotics prescribed (when applicable) and duration of therapy. Antibiotics with a broad spectrum of gram-negative activity were defined as β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations, 2nd, 3rd, or 4th generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, carbapenems, or aminoglycosides. Combination therapy was defined as prescription of two or more concurrent antibiotics. Pre-specified secondary endpoints included the proportion of cases of cellulitis where an antibiotic with activity against MRSA was prescribed, the proportion of drained abscesses where an antibiotic was prescribed, and factors associated with avoidable antibiotic exposure by multivariate analysis.

Clinical failure was a composite endpoint of treatment failure, recurrent infection, or change in therapy due to an adverse drug event within 30 days of the initial visit. Treatment failure was defined as any unplanned drainage procedure, change in antibiotic regimen, hospitalization for treatment, or extension of planned duration of therapy due to inadequate clinical response. Recurrent infection was defined as signs or symptoms of skin infection that required reinitiation of antibiotics.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each variable as appropriate. Stepwise multivariate logistic regression was conducted to determine factors associated with avoidable antibiotic exposure. Entry into the multivariate model was limited to factors with a p-value for univariate association of less than 0.25 or those deemed to be of clinical significance.

In order to estimate total antibiotic use for the entire study cohort, antibiotic-days for each case were first calculated as follows: (1) when antibiotics were prescribed for a known duration, the calendar days of each individual antibiotic prescribed were summed; (2) when antibiotics were prescribed but the duration of therapy was unknown, the median value of antibiotic-days in cases with a known duration of therapy was imputed; (3) when antibiotic therapy was not prescribed (e.g., drained abscesses), antibiotic-days were recorded as zero. Total antibiotic-days for the study cohort were then estimated by summing the antibiotic-days for all cases. To illustrate the opportunity to reduce antibiotic use, we compared total antibiotic-days in the study cohort to total antibiotic-days that would have been prescribed if each of four short-course, single-antibiotic treatment strategies consistent with IDSA guidance12 were applied to the cohort: (1) 7-day course of a single antibiotic for all cases; (2) no antibiotic therapy for abscesses meeting criteria for drainage alone and a 7-day course of a single antibiotic for all other cases; (3) 5-day course of a single antibiotic for all cases; and (4) no antibiotic therapy for abscesses meeting criteria for drainage alone and a 5-day course of a single antibiotic for all other cases. All analyses were conducted using SAS v.9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

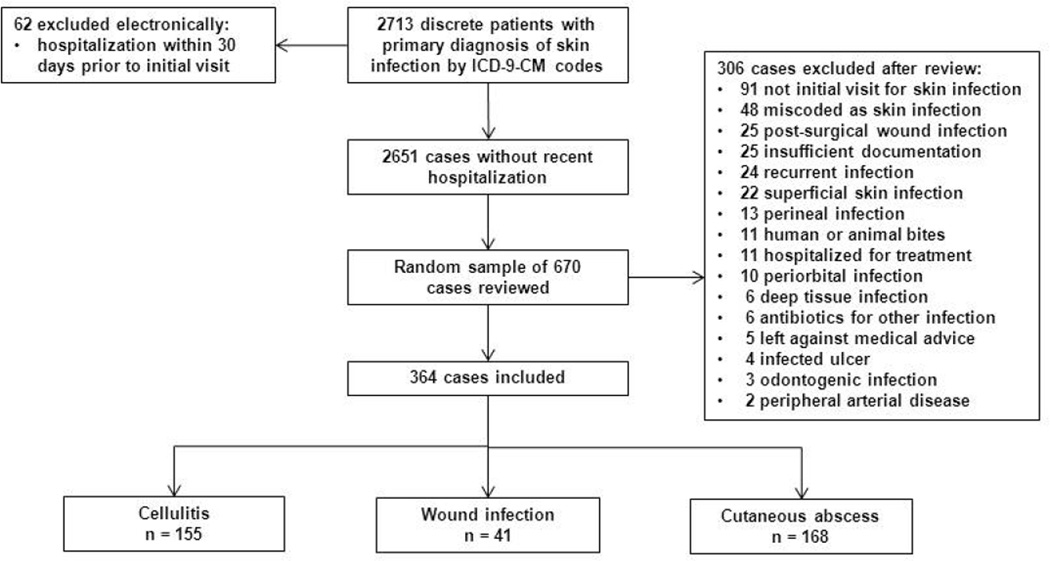

2713 discrete patients had a visit with a primary diagnosis of skin infection by ICD-9-CM codes (Figure 1). Of a random sample of 670 cases reviewed, 306 were excluded for reasons detailed in Figure 1. The remaining 364 cases of uncomplicated skin infection were included in the study: 155 were classified as cellulitis, 41 as wound infection, and 168 as cutaneous abscess.

Figure 1.

Study schematic

The median age of the cohort was 38 years (Table 1); 61 (17%) were 18 years old or younger. Diabetes mellitus (48, 13%) and a prior skin infection (75, 21%) were common risk factors. The majority of infections involved upper (114, 31%) or lower (121, 33%) extremities.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

| Cellulitis n = 155 |

Wound infection n = 41 |

Abscess n = 168 |

Total n = 364 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 37 (21 – 53) | 38 (26 – 53) | 38 (26 – 53) | 38 (24 – 53) |

| Male | 76 (49) | 22 (54) | 87 (52) | 185 (51) |

| Comorbid condition / risk factor a | 66 (43) | 17 (41) | 93 (55) | 176 (48) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 21 (14) | 5 (12) | 22 (13) | 48 (13) |

| Injection drug use | 1 (1) | 3 (7) | 19 (11) | 23 (6) |

| Alcohol abuse or dependence | 19 (12) | 9 (22) | 33 (20) | 61 (17) |

| Lymphedema | 15 (10) | 1 (2) | 0 | 16 (4) |

| Chronic venous stasis | 4 (3) | 0 | 0 | 4 (1) |

| Immunosuppressing medications | 2 (1) | 0 | 4 (2) | 6 (2) |

| HIV infection | 2 (1) | 0 | 3 (2) | 5 (1) |

| Cirrhosis | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 | 2 (1) |

| Dialysis dependence | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Prior skin infection | 23 (15) | 3 (7) | 49 (29) | 75 (21) |

| Prior MRSA infection or colonization | 5 (3) | 0 | 12 (7) | 17 (5) |

| Anatomical location | ||||

| Head and neck | 23 (15) | 3 (7) | 22 (13) | 48 (13) |

| Upper extremity | 46 (30) | 15 (37) | 53 (32) | 114 (31) |

| Lower extremity | 66 (43) | 21 (51) | 34 (20) | 121 (33) |

| Trunk | 16 (10) | 2 (5) | 41 (24) | 59 (16) |

| Buttock | 5 (3) | 0 | 20 (12) | 25 (7) |

| Multiple distinct areas of infection | 9 (6) | 0 | 17 (10) | 26 (7) |

| Duration of symptoms prior to presentation, median days (IQR) | 3 (2– 7) | 4 (2 – 7) | 6 (3 – 7) | 4 (2 – 7) |

| Temperature ≥38°Celsius | 2 (1) | 0 | 3 (2) | 5 (1) |

| White blood cell count >10,000 cells/mm3 | 13/37 (35) | 1/3 (33) | 11/28 (39) | 25/68 (37) |

| Site of initial visit | ||||

| Emergency department | 33 (21) | 7 (17) | 50 (30) | 90 (25) |

| Urgent care | 72 (46) | 20 (49) | 76 (45) | 168 (46) |

| Outpatient clinic | 50 (32) | 14 (34) | 42 (25) | 106 (29) |

Note: Data presented as n (%) unless noted otherwise. IQR, interquartile range.

No cases involved active malignancy, connective tissue disease or vasculitis, or leg vein harvest

Specimens for microbiological culture were obtained in 108 (30%) cases, of which 85 (79%) were abscess cultures (Table 2). Out of the 68 cases with a positive culture, S. aureus or streptococci were present in 65 (96%). Methicillin-susceptible S. aureus was identified more frequently than MRSA (50% vs. 35%), including in cases of abscess (47% vs. 40%). Gram-negative and anaerobic organisms were identified infrequently.

Table 2.

Diagnostic tests and microbiology

| Cellulitis n = 155 |

Wound infection n = 41 |

Abscess n = 168 |

Total n = 364 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory study performed | 37 (24) | 3 (7) | 28 (17) | 68 (19) |

| White blood cell count | 37 (24) | 3 (7) | 28 (17) | 68 (19) |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | 16 (10) | 1 (2) | 12 (7) | 29 (8) |

| C-reactive protein | 18 (12) | 2 (5) | 15 (9) | 35 (10) |

| Imaging study performed | 39 (25) | 7 (17) | 26 (15) | 72 (20) |

| Plain film radiograph | 27 (17) | 6 (15) | 15 (9) | 48 (13) |

| Ultrasound | 14 (9) | 2 (5) | 11 (7) | 27 (7) |

| Computed tomography (CT) scan | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (0.3) |

| Microbiological specimen obtained | 19 (12) | 4 (10) | 85 (51) | 108 (30) |

| Surface culture | 13 (8) | 3 (7) | 2 (1) | 18 (5) |

| Abscess culture | 1 (1) a | 0 | 81 (48) | 82 (23) |

| Blood culture | 5 (3) | 0 | 4 (2) | 9 (2) |

| Other culture b | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Microorganisms identified c | 7 (5) | 4 (10) | 57 (34) | 68 (19) |

| Methicillin-susceptible S. aureus | 4 (57) | 3 (75) | 27 (47) | 34 (50) |

| Methicillin-resistant S. aureus | 0 | 1 (25) | 23 (40) | 24 (35) |

| Streptococci | 2 (29) | 0 | 5 (9) | 7 (10) |

| S. aureus or streptococci | 6 (86) | 4 (100) | 55 (96) | 65 (96) |

| S. aureus or streptococci only | 6 (86) | 3 (75) | 51 (89) | 59 (88) |

| Anaerobe(s) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Gram-negative organismsd | 1 (14) | 1 (25) | 4 (7) | 6 (9) |

| Enterococci | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

case classified as cellulitis at initial visit, abscess had formed by follow-up visit

includes aspirate (2) and operative tissue culture (1)

denominator for proportion of each individual microorganism is cases with a microorganism identified

includes Proteus mirabilis (2), Eikenella corrodens (2), Klebsiella pneumoniae (1), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (1)

Antibiotic regimens with activity against MRSA were prescribed in the majority of cases of cellulitis, wound infection, and abscess (61%, 58%, and 93%, respectively) (Table 3). For cases of abscess, incision and drainage was performed in 139 (83%). Of those 139 cases, antibiotic therapy was prescribed in 111 (80%) for a median of 10 (interquartile range [IQR] 7 – 10) days. Eighty (48%) cases of abscess were candidates for drainage alone by IDSA guidance; of those, 59 (74%) were treated with antibiotics for a median of 10 (IQR 7 – 10) days. For the entire cohort, combination therapy with a β-lactam plus an MRSA-active antibiotic was prescribed in 55 (15%) cases, including 25 (16%) cases of cellulitis, 11 (27%) wound infections, and 19 (11%) abscesses.

Table 3.

Drainage procedures and antibiotic therapy

| Cellulitis n = 155 |

Wound infection n = 41 |

Abscess n = 168 |

Total n = 364 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drainage or debridement performed | 0 | 4 (10) | 139 (83) | 143 (39) |

| Intravenous antibiotic administered at initial visit | 12 (8) | 4 (10) | 9 (5) | 25 (7) |

| Antibiotic regimen prescribed at discharge | 153 (99) | 38 (93) | 134 (80) | 325 (89) |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) | 40 (26) | 7 (17) | 71 (42) | 118 (32) |

| Cephalexin | 49 (32) | 13 (32) | 7 (4) | 69 (19) |

| Doxycycline | 26 (17) | 2 (5) | 25 (15) | 53 (15) |

| β-lactam plus MRSA-active agent a | 25 (16) | 11 (27) | 19 (11) | 55 (15) |

| Clindamycin | 3 (2) | 1 (2) | 8 (5) | 12 (3) |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate | 4 (3) | 0 | 2 (1) | 6 (2) |

| Dicloxacillin | 4 (3) | 2 (5) | 0 | 6 (2) |

| Fluoroquinolone | 1 (1) | 2 (5) | 0 | 3 (1) |

| Other combination | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 3 (1) |

| MRSA-active therapy b, c | 94/153 (61) | 22/38 (58) | 125/134 (93) | 241/325 (74) |

| Duration of therapy prescribed, median days (IQR) d | 7 (7–10) | 7 (7–10) | 7 (5–10) e | 7 (7–10) |

| 5 days | 8 (7) | 0 | 6 (4) | 14 (5) |

| 7 days | 51 (44) | 17 (52) | 44 (31) | 112 (38) |

| 10 days | 53 (46) | 12 (36) | 52 (36) | 117 (40) |

| 14 or more days | 1 (1) | 0 | 4 (3) | 5 (2) |

| Other duration f | 1 (1) | 1 (3) | 3 (2) | 5 (2) |

MRSA, methicillin-resistant S. aureus. IQR, interquartile range.

includes cephalexin/TMP-SMX (48), cephalexin/doxycycline (1), cephalexin/clindamycin (1), amoxicillin-clavulanate/TMP-SMX (3), penicillin/TMP-SMX (1), dicloxacillin/TMP-SMX (1)

denominator includes only patients who were treated with antibiotics

treatment regimen included vancomycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, doxycycline, or clindamycin

analysis limited to 292 cases with known duration of therapy

includes cases where no antibiotic was given; when limited to the 134 cases where an antibiotic was prescribed, the median increased to 10 (IQR 7 – 10) days

includes 1 day (1), 6 days (1), and 9 days (3)

For the 292 cases with complete prescribing documentation, avoidable antibiotic exposure occurred in 135 (46%) and was common for all three types of uncomplicated skin infection (Table 4). Avoidable antibiotic exposure was most frequently due to use of combination therapy (35, 12%) or treatment for 10 or more days (122, 42%). Only 5 (2%) cases were treated for longer than 10 days. By multivariate logistic regression, the only factor independently associated with avoidable antibiotic exposure was type of infection (cellulitis or wound infection versus abscess: odds ratio 1.7, 95% confidence interval 1.1 – 2.8)

Table 4.

Avoidable antibiotic exposure in 292 cases with complete prescribing data a

| Cellulitis n = 116 |

Wound infection n = 33 |

Abscess n = 143 |

Total n = 292 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cases with avoidable antibiotic exposure | 60 (52) | 17 (52) | 58 (41) | 135 (46) |

| Antibiotics with a broad spectrum of gram-negative activity | 5 (4) | 3 (9) | 3 (2) | 11 (4) |

| Combination antibiotic therapy | 15 (13) | 8 (24) | 12 (8) | 35 (12) |

| Treatment for 10 or more days | 54 (47) | 12 (36) | 56 (39) | 122 (42) |

analysis excludes 72 cases where an antibiotic was prescribed but the duration of therapy could not be determined

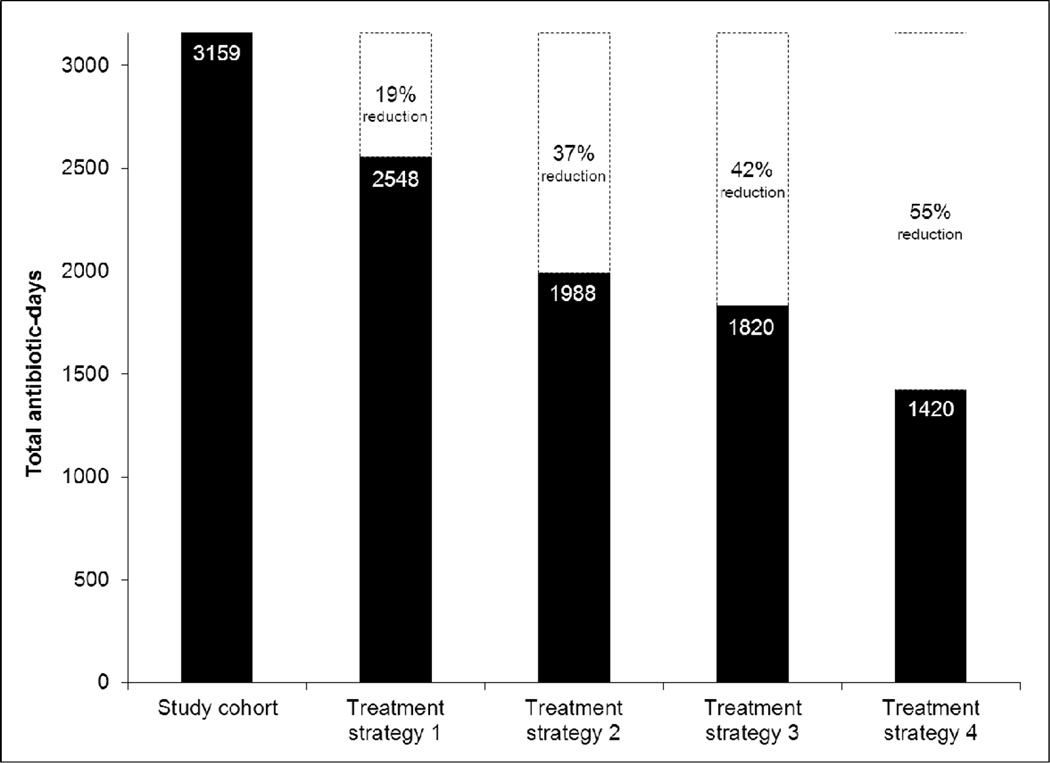

For the entire study cohort, an estimated 3159 antibiotic-days were prescribed (Figure 2). Utilization of the four short-course, single-antibiotic treatment strategies would have resulted in 1420 to 2548 antibiotic-days, representing 19 to 55% reductions in antibiotic use compared with the study cohort. In total, clinical failure occurred in 52 (14%) cases (Table 5). The rate of clinical failure was 14% in cases involving avoidable antibiotic exposure and 11% in all others (p = 0.34).

Figure 2.

Estimated total antibiotic-days prescribed in the study cohort and in four hypothetical short-course, single-antibiotic treatment models. Treatment strategy 1: 7-day course of a single antibiotic for all cases. Treatment strategy 2: no antibiotic therapy for cases of abscess meeting IDSA criteria for drainage alone, 7-day course of a single antibiotic for all other cases. Treatment strategy 3: 5-day course of a single antibiotic for all cases. Treatment strategy 4: no antibiotic therapy for cases of abscess meeting IDSA criteria for drainage alone, 5-day course of a single antibiotic for all other cases. Dashed boxes indicate the relative reduction in total antibiotic-days that would be achieved utilizing each respective treatment strategy compared with the study cohort.

Table 5.

Clinical outcomes

| Cellulitis n = 155 |

Wound infection n = 41 |

Abscess n = 168 |

Total n = 364 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up visit within 30 days | 72 (46) | 22 (54) | 100 (60) | 194 (53) |

| Clinical failure | 24 (15) | 4 (10) | 24 (14) | 52 (14) |

| Treatment failure | 19 (12) | 3 (7) | 24 (14) | 46 (13) |

| Unplanned drainage procedure | 5 (3) | 1 (2) | 18 (11) | 24 (7) |

| Change in antibiotic | 14 (9) | 3 (7) | 17 (10) | 34 (9) |

| Hospitalization for treatment | 6 (4) | 0 | 5 (3) | 11 (3) |

| Extension of planned duration of therapy | 5 (3) | 0 | 1 (1) | 6 (2) |

| Recurrence | 7 (5) | 0 | 1 (1) | 8 (2) |

| Change in antibiotic due to adverse drug event | 2 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 | 3 (1) |

Discussion

Skin and soft tissue infections are one of the most frequent indications for antibiotic use in the ambulatory care setting. In this cohort of patients with uncomplicated skin infection, avoidable antibiotic exposure occurred in nearly half of cases, most often related to use of combination therapy or treatment for 10 or more days. Over 60% of cases of cellulitis were prescribed a regimen with activity against MRSA. Antibiotics were prescribed in approximately three quarters of cases of abscess that were candidates for drainage alone according to IDSA guidance. A treatment approach utilizing short courses of a single antibiotic (or drainage alone for low-risk abscesses) would have reduced antibiotic exposure by 19 to 55%.

Previous population-based studies of outpatient skin infections demonstrated an increase in use of antibiotics with MRSA activity and a decrease in use of β-lactam agents during the emergence of CA-MRSA from 2000 to 2005.6,7 The present study is a comprehensive evaluation that provides both an update on antibiotic prescribing practices as the CA-MRSA epidemic has evolved and additional details regarding antibiotic selection and duration of therapy. Such information may inform the prioritization and development of outpatient antimicrobial stewardship interventions.

A number of aspects of the treatment of uncomplicated skin infections are controversial. The three elements of our composite primary endpoint of avoidable antibiotic exposure therefore warrant further discussion. First, use of antibiotics with a broad spectrum of gram-negative activity is perhaps the most straight forward of the three since the vast majority of uncomplicated skin infections are caused by gram-positive pathogens13,14 and national guidelines recommend antibiotics targeting these organisms.12,15 Thus, prevention of the use of agents with a broad spectrum of gram-negative activity is one approach to reducing unnecessary antibiotic exposure. Fortunately, in contrast to the treatment of inpatient skin infections,8,9 we found use of agents with broad gram-negative activity in the ambulatory care setting to be relatively uncommon.

Second, we believe that combination antibiotic therapy such as a β-lactam plus an MRSA-active agent is avoidable in most cases of uncomplicated skin infection. Although current IDSA guidance presents combination therapy as an option “if coverage for both β-hemolytic streptococci and CA-MRSA is desired,”12 it is noted that the need for such coverage is controversial. Since publication of the guideline, the only randomized trial to date evaluating combination therapy for uncomplicated cellulitis demonstrated that cephalexin plus trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole did not improve clinical response compared with cephalexin alone.16 A larger randomized trial evaluating the same antibiotic regimens for uncomplicated cellulitis is nearing completion.17 In the case of cutaneous abscess, adjunctive antibiotic therapy provides little, if any, incremental benefit over drainage alone,18,19 and S. aureus is the overwhelmingly predominant pathogen. Consequently, there is no reason to expect that adding a β-lactam to an MRSA-active agent would substantially improve outcomes. On the other hand, it certainly has the potential to increase adverse events. Despite the lack of evidence supporting a role for combination therapy in any type of uncomplicated skin infection, we found that use of a β-lactam plus an MRSA-active agent was relatively common across all three types. Pending the results of additional studies, our opinion is that based on currently available evidence, use of combination therapy in uncomplicated skin infections should be discouraged.

Last, we believe that even though the optimal duration of therapy for uncomplicated skin infection has not been definitively established, treatment durations of 10 or more days represent an opportunity to reduce antibiotic use. We acknowledge that a 10-day treatment course is within IDSA guideline recommendations for 5 to 10 days of therapy for outpatient cellulitis.12 However, treatment durations of 5 or 6 days appear to be as effective as 10 days.20,21 Our data demonstrate that providers uncommonly treat cellulitis for only 5 days (7% of cases) but treat for 10 days in nearly half of cases. Regardless of whether one considers a 10-day course of therapy to be appropriate, shifting prescribing practices to shorter durations (i.e., 5 – 7 days) has the potential to substantially reduce antibiotic exposure while adhering to national guidelines.

With respect to the optimal duration of therapy in cases of cutaneous abscess, whether adjunctive antibiotics are needed after abscess drainage remains controversial.22,23 IDSA guidance recommends drainage alone for simple abscesses without complicating factors.12 In the present study, antibiotics were prescribed in nearly three quarters of such cases highlighting the discordance between current guidelines and clinical practice. It is also notable that when antibiotics were prescribed after abscess drainage, the duration of therapy was 10 or more days in close to half of cases. Since drainage alone is sufficient to cure most abscesses,18,19 use of shorter courses of therapy – when antibiotics are prescribed – seems rational. The results of an ongoing large, randomized trial should help to clarify the role of adjunctive antibiotic therapy in the management of cutaneous abscess.17 In the meantime, our findings suggest that much of current antibiotic exposure is avoidable through drainage alone or use of shorter treatment courses when antibiotics are prescribed.

Despite the CA-MRSA epidemic, treatment targeted toward β-hemolytic streptococci (i.e., β-lactams) continues to be effective for cellulitis13,24–26 and may result in fewer adverse events than antibiotics with MRSA activity.25 We found that MRSA-active agents – most commonly trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole – were prescribed in approximately 60% of uncomplicated cellulitis cases. This suggests a lack of understanding of the microbiology of cellulitis or may simply reflect discomfort in not covering for MRSA. Unfortunately, this practice may put patients at risk for poor outcomes, as Elliott and colleagues demonstrated an increased risk of treatment failure with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole compared with β-lactams in non-purulent skin infections.24 Future interventions to optimize prescribing for uncomplicated skin infections should therefore include efforts to educate providers regarding the appropriate spectrum of antibiotic therapy for cellulitis.

Extrapolating data from our cohort to the entire Denver Health ambulatory care system, utilizing one of the proposed short-course, single-antibiotic treatment strategies would have avoided between 2419 and 6881 antibiotic-days (6.6 to 18.9 antibiotic-years!) during the one-year period. Foregoing antibiotic therapy for low-risk abscesses and treating the remainder of uncomplicated skin infections with 5 days of a single antibiotic, a treatment approach concordant with IDSA guidance,12 would have cut antibiotic use by over half. This degree of potentially avoidable antibiotic exposure and the frequency of uncomplicated skin infections highlight the importance of focusing antimicrobial stewardship resources to these infections.

Our study had several important limitations. First, it was performed at a single institution; however, the inclusion of children and adults and diverse sites within a large ambulatory care system increase the generalizability. Second, due to the retrospective nature of the study, we could not determine the duration of therapy in 20% of cases where an antibiotic was prescribed and therefore excluded such cases from the primary endpoint analysis. It is also possible that antibiotics were prescribed, but not documented, in some cases. This could explain the apparent non-treatment of several cases of cellulitis and wound infections. Overall, this study underestimates the true burden of skin infections and resultant antibiotic use in our ambulatory care system as we excluded presentations for a non-first episode or secondary diagnosis of skin infection and those with limited documentation. Finally, the most recent IDSA guideline addressing the management of uncomplicated skin infections was not published until the last month of the study period.12 It is therefore important to point out that this study was not an evaluation of adherence to guideline recommendations. Rather, the recommendations are discussed to provide context to the observed prescribing practices and highlight the opportunity to decrease antibiotic use.

In summary, uncomplicated skin infections are frequently associated with avoidable antibiotic exposure. Total antibiotic use could be substantially reduced through utilization of a short-course, single-antibiotic treatment approach. Skin infections are therefore a high-yield target for antimicrobial stewardship interventions aimed at preventing unnecessary antibiotic exposure. Based on our findings, we are planning an initiative involving an institutional treatment guideline, provider education, and peer-champion advocacy to improve prescribing.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Departments of Medicine and Patient Safety and Quality, Denver Health Medical Center. Dr. Jenkins was supported by NIAID at NIH (K23 AI099082). Conflicts of interest: All authors, no conflicts.

References

- 1.Hicks LA, Chien YW, Taylor TH, Jr, et al. Outpatient antibiotic prescribing and nonsusceptible Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States, 1996–2003. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2011 Oct;53(7):631–639. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson L, Sabel A, Burman WJ, et al. Emergence of fluoroquinolone resistance in outpatient urinary Escherichia coli isolates. The American journal of medicine. 2008 Oct;121(10):876–884. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun L, Klein EY, Laxminarayan R. Seasonality and temporal correlation between community antibiotic use and resistance in the United States. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2012 Sep;55(5):687–694. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shehab N, Patel PR, Srinivasan A, et al. Emergency department visits for antibiotic-associated adverse events. Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Sep 15;47(6):735–743. doi: 10.1086/591126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benson L, Song X, Campos J, et al. Changing epidemiology of Clostridium difficile-associated disease in children. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007 Nov;28(11):1233–1235. doi: 10.1086/520732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hersh AL, Chambers HF, Maselli JH, et al. National trends in ambulatory visits and antibiotic prescribing for skin and soft-tissue infections. Arch Intern Med. 2008 Jul 28;168(14):1585–1591. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.14.1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pallin DJ, Egan DJ, Pelletier AJ, et al. Increased US emergency department visits for skin and soft tissue infections, and changes in antibiotic choices, during the emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Ann Emerg Med. 2008 Mar;51(3):291–298. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jenkins TC, Sabel AL, Sarcone EE, et al. Skin and soft-tissue infections requiring hospitalization at an academic medical center: opportunities for antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2010 Oct 15;51(8):895–903. doi: 10.1086/656431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jenkins TC, Knepper BC, Sabel AL, et al. Decreased antibiotic utilization after implementation of a guideline for inpatient cellulitis and cutaneous abscess. Arch Intern Med. 2011 Jun 27;171(12):1072–1079. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gabow P, Eisert S, Wright R. Denver Health: a model for the integration of a public hospital and community health centers. Ann Intern Med. 2003 Jan 21;138(2):143–149. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-2-200301210-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) [Accessed 6 February 2013];Draft guidance for industry: acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections—developing drugs for treatment. 2010 Aug; Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm071185.pdf.

- 12.Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the infectious diseases society of america for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children: executive summary. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2011 Feb 1;52(3):285–292. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeng A, Beheshti M, Li J, et al. The role of beta-hemolytic streptococci in causing diffuse, nonculturable cellulitis: a prospective investigation. Medicine. 2010 Jul;89(4):217–226. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181e8d635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moran GJ, Krishnadasan A, Gorwitz RJ, Methicillin-resistant S, et al. aureus infections among patients in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2006 Aug 17;355(7):666–674. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft-tissue infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Nov 15;41(10):1373–1406. doi: 10.1086/497143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pallin DJ, Binder WD, Allen MB, et al. Clinical trial: comparative effectiveness of cephalexin plus trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole versus cephalexin alone for treatment of uncomplicated cellulitis: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2013 Jun;56(12):1754–1762. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. [Accessed 8 August 2013]; ClinicalTrials.gov: A Service of the U.S. National Institutes of Health ( NCT00729937) Available at: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/.

- 18.Schmitz GR, Bruner D, Pitotti R, et al. Randomized controlled trial of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for uncomplicated skin abscesses in patients at risk for community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. Annals of emergency medicine. 2010 Sep;56(3):283–287. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duong M, Markwell S, Peter J, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of antibiotics in the management of community-acquired skin abscesses in the pediatric patient. Annals of emergency medicine. 2010 May;55(5):401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hepburn MJ, Dooley DP, Skidmore PJ, et al. Comparison of short-course (5 days) and standard (10 days) treatment for uncomplicated cellulitis. Arch Intern Med. 2004 Aug 9–23;164(15):1669–1674. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.15.1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prokocimer P, De Anda C, Fang E, et al. Tedizolid phosphate vs linezolid for treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections: the ESTABLISH-1 randomized trial. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2013 Feb 13;309(6):559–569. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spellberg B, Boucher H, Bradley J, et al. To treat or not to treat: adjunctive antibiotics for uncomplicated abscesses. Annals of emergency medicine. 2011 Feb;57(2):183–185. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hankin A, Everett WW. Are antibiotics necessary after incision and drainage of a cutaneous abscess? Annals of emergency medicine. 2007 Jul;50(1):49–51. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elliott DJ, Zaoutis TE, Troxel AB, et al. Empiric antimicrobial therapy for pediatric skin and soft-tissue infections in the era of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Pediatrics. 2009 Jun;123(6):e959–e966. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madaras-Kelly KJ, Remington RE, Oliphant CM, et al. Efficacy of oral beta-lactam versus non-beta-lactam treatment of uncomplicated cellulitis. Am J Med. 2008 May;121(5):419–425. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wells RD, Mason P, Roarty J, et al. Comparison of initial antibiotic choice and treatment of cellulitis in the pre- and post-community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus eras. Am J Emerg Med. 2009 May;27(4):436–439. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]