Abstract

Pediatricians should consider the costs and benefits of preventing rather than treating childhood diseases. We present an integrated developmental approach to child and adult health that considers the costs and benefits of interventions over the life cycle. We suggest policies to promote child health that are currently outside the boundaries of conventional pediatrics. We discuss current challenges to the field and suggest avenues for future research.

KEY WORDS: health, prevention, remediation, capabilities, technology of capability formation

Modern medicine focuses on treatment rather than prevention. Scientists have made great strides in finding effective cures for many pediatric illnesses. They have developed novel drugs and innovative treatments. Policy makers have expanded child health-insurance coverage and implemented vaccination programs that have almost eliminated many formerly common and serious diseases. Pediatricians can be justly proud of these important advances, but we believe that the field can do even better.

A growing body of knowledge about the origins of childhood disease exists but this knowledge has not made its way into mainstream pediatric practice. Strategies currently well outside today’s accepted boundaries of medicine might be the key to further progress in preventing illness and promoting health.

By many indicators of child health, the United States has not kept up with progress in other industrialized countries. One leading example is infant mortality.1 The United States used to have one of the lowest rates of infant mortality in the world. Today we are not even in the top 10. For this and other childhood conditions, strategies currently well outside the boundaries of medicine can be effective in preventing illness and promoting health.

Recent evidence from both the biological and social sciences points to the importance of the early years in building the foundations for lifelong health.2 We now recognize that human development is a dynamic process that starts in the womb3 and that early-life conditions affect the emergence and evolution of human traits,4 which affect a variety of adult outcomes, including health.5–7 Later life environmental influences on development also matter, as does resilience in response to adversity.

For the purposes of public policy, however, it is not enough to know that early-life conditions matter. It is important to know the costs and benefits of remediating early-life deficits at different stages of the life cycle.

A developmental focus suggests new channels for policy influence. Early childhood interventions that enrich the environments of disadvantaged children can be effective policy tools to prevent disease and promote health. An integrated developmental approach to health, starting before conception, is needed to analyze synergies in producing health, cognition, and other mental and behavioral traits and to model the economic, social, and biological mechanisms that produce health over the life course and transmit it across generations.

The Long-lasting Effects of Early Life Experiences

The contribution of the social and economic circumstances of early childhood to health throughout the life course is now well documented.8,9 Some of the most compelling evidence on the consequences of early maternal and social deprivation comes from children raised in the adverse settings of Romanian orphanages of the 1980s and 1990s. The most recent research shows a high degree of persistence until 15 years of age of cognitive impairments, suboptimal physical development, and behavioral problems.10 Researchers have found that early-life adverse rearing conditions have detrimental effects on physical health and behavioral development even in nonhuman primates.11,12 Environmental enrichment later in life can partially remediate consequences arising in part from adverse early environments, both in animals10,13,14 and in humans, even after severe deprivation.15 Notably, in every study, the timing of the intervention is a crucial factor. The earlier the intervention, the higher the probability of remediating early disadvantage.

In recent years, we have begun to gain a much more sophisticated understanding of how the circumstances in which children are born and raised “get under the skin” and affect the biological development of the brain and of the rest of the body. Studies of stress response pathways, allostatic load, neuronal development, and, more recently, epigenetic mechanisms, have shown that the environment can become biologically embedded in the body in ways that can affect (also through latent pathways) health across the life course. However, the exact mechanisms through which the environment operates and the nature of the biological embedding are just beginning to be understood. The current state of knowledge suggests that adverse conditions early in life induce changes in brain structure and functions and that these environmental stressors can affect epigenetic programming of long-term changes in neural development and behaviors.16 The temporal nature of brain development implies that environmental exposures at different ages will affect different areas of the brain. However, we are just beginning to understand the exact mechanisms through which the environment operates to change the structure of different areas of the brain. We still do not know how epigenetic marks translate from a transient state to lasting cellular memory. Experimental evidence for rhesus monkeys suggests that early adversity gets under the skin and establishes stable marks early and independently of cumulative exposures.17 Comparable evidence for humans finds persistent epigenetic differences associated with early adversity.18 However, the quantitative importance and the causal nature of these biological changes need to be rigorously established.

On the other hand, we do know that the family environments in which children are being raised have been worsening over time.19 Divorce rates have been on the rise, and less-educated women tend to be single parents. They also tend to work in lower-wage jobs and invest less in their children than do more educated women.20 The economic recession and the financial stress coming with it has been a primary contributor to family conflict. Furthermore, for the first time in >30 years, mental health problems have displaced physical conditions as the leading causes of disabilities in US children.21 It is hard to believe that the rise of developmental disorders such as ADHD, which are caused by multiple and complex genetic and environmental factors, might be due entirely to better diagnostic tools or thresholds. Nonetheless, this change in the epidemiology of child illness finds the pediatric system unprepared, and there is the risk of incurring huge costs in the future if they are not properly faced. Child mental health problems affect a wider variety of adult outcomes than physical conditions, ranging from reduced educational attainment to increase in the probability of engaging in unhealthy behaviors.22,23

This evidence suggests that inequalities in endowments and environments present at birth can affect the biology of the body, propagate throughout childhood, and persist into adulthood. It also reveals promising avenues for interventions by enriching the nurturing environments of children born in disadvantaged families and allowing them to develop their full potential. However, despite a large body of evidence on the beneficial effects of such policies,6,24 early childhood programs still are not considered an option in pediatric practice. Before reviewing evidence from interventions, we present a life cycle developmental framework to conceptualize and interpret it.

The Biology and Economics of Health and Human Development

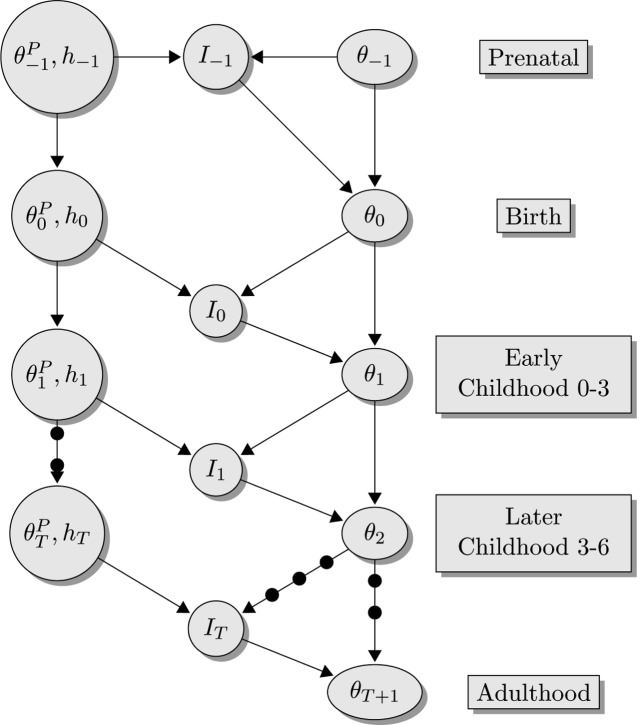

Heckman25 and Cunha and Heckman26 developed a framework for analyzing the expression and evolution of capabilities, from conception through adulthood that links early-life conditions to late-life outcomes by accounting for intervening mechanisms and a variety of exposures at different levels. This framework recognizes the multiple natures of capabilities, the synergies across them, and the need to consider the child in her entirety by developing her cognitive potential together with her physical and mental health. Hence, the different aspects of the well-being of the child can be written in terms of the capability vector , which can have different components, such as cognition

, which can have different components, such as cognition  , mental health

, mental health  , and physical health

, and physical health  . Capabilities are the capacities to function effectively in economic and social life. There are many capabilities. These capabilities of the child can have different weights in affecting adult outcomes, so that a shortfall in one dimension can be compensated by a greater strength in another. Other capabilities, instead, can have a great degree of specificity. Some of these traits might operate as determinants of choices, whereas others operate through purely biological mechanisms.* These capabilities are not solely genetically determined. They are produced early in the life of the child, and their evolution over time can be represented by the following dynamics of capability formation25:

. Capabilities are the capacities to function effectively in economic and social life. There are many capabilities. These capabilities of the child can have different weights in affecting adult outcomes, so that a shortfall in one dimension can be compensated by a greater strength in another. Other capabilities, instead, can have a great degree of specificity. Some of these traits might operate as determinants of choices, whereas others operate through purely biological mechanisms.* These capabilities are not solely genetically determined. They are produced early in the life of the child, and their evolution over time can be represented by the following dynamics of capability formation25:

|

This equation captures the notion that the development of child health and other capabilities in subsequent periods depends on the stock already present, as well as on parental traits, environments, and investments,† starting with the initial endowments determined at conception  , which are function of maternal investments in pregnancy

, which are function of maternal investments in pregnancy  . It also embeds the idea that capabilities at one age enhance capabilities at later ages.

. It also embeds the idea that capabilities at one age enhance capabilities at later ages.

For example, a healthy child who is able to pay attention in class learns more and increases his cognitive ability. This capability can, in turn, have positive effects on his mental and physical health. This framework also recognizes that the productivity of investments depends on the age at which they are made, so that it is easier to develop certain capabilities at certain ages. An investment’s success depends on the plasticity of the organs that govern the functions underlying these capabilities. If investment effects are especially strong in one period, it is called a sensitive period. If investments are productive in only 1 period, it is called a critical period. An important feature of this framework is the complementarity of capabilities with investments, that is, the fact that investments are more productive in children with higher stocks of capabilities. This not only implies that providing early nurturing environments to children affects their health and development but also that early-life interventions have to be followed up with quality schooling and health care for them to be effective in the long-term.

Figure 1 summarizes the framework graphically. Progress has been made in estimating some of the linkages displayed in this figure, but most remain unknown.‡ The figure suggests both opportunities and dangers. Investments and environments shape capabilities. There are many stages and strategies for intervention. Understanding at which stages investments are most effective for shaping which capabilities will inform health policy. To make wise policy choices, it is necessary to have a deeper understanding of the mechanisms, both social and biological, displayed in Fig 1. Knowing that early-life conditions causally affect adult health does not tell us the channels through which they operate or the mechanisms through which effective remediation might occur. Early-life conditions might trigger a series of later-life events that shape the capabilities that produce adult outcomes. Perhaps later-life interventions are highly effective and later-life remediation is effective. Alternatively, early-life conditions might affect biology in an irreversible way. In this case, early-life interventions are essential. The current literature offers only hints at answers to these questions. When the causal links of Fig 1 are fleshed out, analysts will be better able to suggest effective, age-graded policies for promoting child health and development. Surely our ability to design effective policies will increase as evidence from the biological sciences on windows of plasticity for specific organs sharpens. However, even at this point, we can review some promising interventions on the basis of available evidence, as we do in the following section.

FIGURE 1.

A life cycle framework for the development of capabilities.

Policies to Promote Child Health and Development

In this section, we review recent evidence on the effectiveness of interventions at different stages of childhood, which compensate, in part, for the risks arising from growing up in disadvantaged environments.

Early Interventions

We first consider research focusing on the earlier channels of influence displayed in Fig 1. The most reliable evidence on the effectiveness of early interventions comes from experiments that substantially enriched the early environments of children born in disadvantaged families. We consider 2 iconic interventions, the Perry Preschool Project (PPP) and the Carolina Abecedarian Project (ABC), because they have been evaluated by the method of random assignment, have long-term follow-ups, and their health effects have recently been investigated.

The High/Scope PPP is a social experiment designed to evaluate the impact of the novel Perry curriculum on highly disadvantaged African American children aged 3 to 5 years. It was administered to 5 cohorts of children during the early to mid-1960s in the district of the Perry Elementary School in Ypsilanti, Michigan. The intervention consisted of 2.5 hours of classes each day for 5 days per week during the regular school year and included weekly home visits lasting 1 to 1.5 hours. The curriculum was based on the concept of active learning, which is centered around play, based on problem solving, and placed within a structured daily routine. The final sample consisted of 123 children over 5 entry cohorts.

The ABC is a social experiment designed to test if an intellectually stimulating environment could prevent the development of mild mental retardation for disadvantaged children. The intervention was much more intense than the PPP. It was year-round and full day. It consisted of a 2-stage treatment: a preschool treatment targeting early childhood education (from 2 months until 5 years), and a subsequent school-age treatment targeting initial schooling (from 5 to 8 years). It used a systematic curriculum specially developed by Sparling and Lewis27,28 that consisted of a series of “learning games” but also included a nutritional and health care component.§ It was administered to 4 cohorts of children born between 1972 and 1977 and living in or near Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Eligibility was based on a High-Risk Index computed from 13 socioeconomic factors capturing disadvantage. The final sample consisted of 111 children recruited over a 5-year period, resulting in 4 cohorts. Unlike PPP, ABC provided access to full health services to participants as well as adequate nutrition.

Both the PPP and the ABC interventions show consistent patterns of successful outcomes for treatment group members compared with control group members for both boys and girls.29,30 Although among PPP participants, an initial increase in IQ gradually faded out in the 4 years after the intervention, at the oldest age studied (age 40), treated individuals had attained higher levels of education, earned higher wages, and were less likely to be on welfare or to commit crime than the control subjects.

Heckman et al31 show that the effects of the intervention on life outcomes operate primarily through the program’s reduction in children’s externalizing behaviors. Previous attempts at analyzing the effects of these programs on health and risk behaviors32,33 have not accounted for the variety of statistical challenges that these small sample randomized controlled trials pose, have not investigated gender differences in the treatment effects, and have not considered health effects across the whole life course of the subjects. Conti et al34 overcame all these limitations and carried out an extensive analysis by taking advantage of all the health information available in the ABC and PPP samples since early childhood and including newly collected unique biomedical data. They found statistically significant and economically important program effects for both male and female participants that were not uncovered in the pooled gender analysis and that survive when simultaneously tackling all the statistical challenges. Both ABC and PPP participants had significantly fewer behavioral risk factors (eg, smoking, drinking, drug use, adhering to safe traffic practices) and higher health care coverage. The ABC participants also had a leaner physical constitution in childhood;‖ additionally, the analysis of the biomeasures recently collected for this sample reveal that they were also in better physical health by the time they reached their mid-30s. See Table 1 for an overview of the results. Other studies, such as the Nurse-Family Partnership,35 which visits pregnant girls and teaches them prenatal health practices and parenting, also provide evidence of a variety of positive health effects from early environmental enrichment (J. Heckman, M. Holland, T. Oey, D. Olds, R. Pinto, M. Rosales. A reanalysis of the nurse family partnership program: The Memphis randomized control trial, unpublished manuscript, 2012). Prenatal home visiting programs such as the NFP or the doula¶ are also particularly appealing, both because they reach at-risk families as early as possible and because they intervene at the same time on children and adolescent mothers by affecting those traits still amenable to change during adolescence.36

TABLE 1.

Health Effects From the PPP and the ABC Interventions—Selected Results

| PPP | ABC | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Control mean | Diff. means | Asym. P value | IPW P value | Variable | Control mean | Diff. means | Asym. P value | IPW P value |

| Behavioral risk factors | |||||||||

| Never drunk without permission by age 15 (F) | 0.682 | 0.152 | .140 | .040 | Started smoking by age 15 (parent report) (M) | 0.190 | −0.114 | .127 | .064 |

| Never smoked marijuana by age 27 (F) | 0.364 | 0.156 | .146 | .089 | First tried marijuana before age 17 (F) | 0.393 | −0.233 | .031 | .053 |

| Drinks alcohol never or once in a while at age 27 (F) | 0.773 | 0.107 | .169 | .013 | First drink before age 17 (F) | 0.571 | −0.291 | .016 | .047 |

| Non-smoker at age 27 (M) | 0.462 | 0.119 | .164 | .080 | Started smoking regularly before age 17 (M) | 0.304 | −0.189 | .052 | .030 |

| Always wears a seat belt at age 40 (M) | 0.618 | 0.182 | .057 | .080 | Always wears a seatbelt at age 21 (F) | 0.500 | 0.220 | .052 | .028 |

| Nonsmoker at age 40 (M) | 0.472 | 0.161 | .098 | .020 | Has drank and driven in past month at age 21 (F) | 0.222 | −0.102 | .170 | .042 |

| Any change in diet in past 15 y at age 40 | 0.229 | 0.151 | .097 | .018 | Physical activity in past week at age 21 (F) | 0.071 | 0.249 | .010 | .012 |

| Health care coverage | |||||||||

| Covered by health insurance in past 15 y at age 40 (F) | 0.682 | 0.068 | .308 | .044 | Covered by health insurance at age 30 (M) | 0.476 | 0.228 | .057 | .088 |

| Health | |||||||||

| Never classified as mentally impaired by age 19 (F) | 0.636 | 0.280 | .010 | .036 | BSI Depression score at age 21 (F) | 59.643 | −5.601 | .026 | .002 |

| BMI z score at 60m (M) | 0.601 | −0.695 | .009 | .026 | |||||

BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory; F, female; IPM, inverse probability weighting; M, male. This table includes 2 panels, the left panel for the PPP, the right panel for the ABC. Each panel comprises 5 columns: (1) the first column describes the variable of interest, the age at which the information was collected, and the child’s gender. PPP: “Any change in diet” is in relation to health reasons. ABC: “Wearing a seatbelt” refers to when riding in a car driven by someone else. “Physical activity” is defined as exercise or participation in sports activities for at least 20 min on 4 or more of the past 7 d at age 21. The BMI z score is computed by using the 2000 Centers for Disease Control growth charts. (2) The second column shows the mean of the control group, that is, the group that was not administered the intervention. (3) The third column shows the unconditional difference in means between the treatment and the control group. (4) The fourth column presents the asymptotic P value of the 1-sided single hypothesis based on the t statistic associated with the unconditional difference in means in (3). (5) The fifth column presents the 1-sided single hypothesis constrained permutation P value based on the IPW t-statistic associated with the difference in means between treatment and control groups. We implement conditional inference to account for any compromise to the randomization protocol. We use permutation-based inference to account for the small size of the samples. By constrained permutation, we mean that permutations are done within strata defined by the preprogram variables used in the randomization protocol. We use IPW to account for nonrandom attrition. Note all these treatment effects survive correction for multiple hypothesis testing. See Conti et al (2012) for details.

Later-Life Interventions

Although the economic benefits to early interventions are substantial,37 at the same time, we cannot abandon the children who have had no access to this foundational opportunity and adults who did not have such opportunities as children. We now consider the effectiveness of later channels of influence displayed in Fig 1.

The key to successful remediation is to invest in carefully designed programs that address those capabilities amenable to change. On one hand, although the reversibility of structural and functional changes in the brain after early life adverse conditions has not been systematically investigated, recent research in humans is beginning to document the effects of specific interventions in adults to reduce stress and promote mental well-being.38 On the other hand, although environmental enrichment in puberty has shown positive effects in both animals41 and humans,39 the optimal timing and duration and the most effective components of these interventions are not yet well understood. Nonetheless, knowledge is accumulating rapidly, and designing and implementing biologically based interventions is the key to promoting the health of the future generation and not abandoning the current one.

Here we consider in particular one later intervention: education. Is education policy a promising avenue for promoting child health? Specifically, what is the effect of education in the adolescent years on health and healthy behaviors? Enhanced capabilities promote schooling and also health and healthy behaviors, both beyond their direct effects on education and through the effects of education on health.41 Although gaps in cognitive ability emerge early and persist strongly, those in other mental traits are less persistent. The fluidity of personality traits over the adolescent years is associated with the slowly emerging prefrontal cortex.42 At current levels of practice, adolescent remediation for cognitive deficits has proved largely ineffective. Adolescent interventions in personality are more promising, although there is less evidence on these to date.5,43–45 Traits beyond cognition have been shown to play a fundamental role in understanding disparities in health and health behaviors by education.23,41

Yet what is the relative importance of education compared with factors formed before the adolescent years? Figure 2, based on British data analyzed by Conti et al,41 shows the effect (by gender) of attendance beyond compulsory schooling on health and healthy behaviors measured at age 30. The height of the bars (including both the light and dark portions) displays mean differences in a variety of outcomes between those who stop their education at the minimum compulsory schooling level and those who continue. It is clear that more educated individuals are better off in a variety of dimensions.

FIGURE 2.

Mean differences in outcomes due to early life factors versus the causal effect of education.

However, the crucial question is the extent to which education actually causes the difference between more and less educated individuals, which would bear on whether increasing the educational level of the population would be an effective health policy. If the more educated individuals are in better health simply because they have better capabilities developed during the early years, which are associated with both increased education and better health outcomes, then early intervention is a more effective strategy to promote health not only in childhood but throughout the life course. To answer this question, Fig 2 decomposes the drivers of a variety of outcomes by gender. The dark portion of each bar in the graph is the causal contribution of education, and the light portion quantifies the contribution of early capabilities (cognition, mental and physical health traits) shaped by family investments and environments. It shows that these early-life factors account for at least a half of the adult disparities in poor health, depression, and obesity. In addition, these early-life traits promote education, which has independent effects on outcomes, in particular on healthy behaviors.

Finally, capabilities developed in early childhood can also affect health in the next generation, both directly and by affecting education and the choices that the mothers make while pregnant. Conti et al47 studied the determinants of newborn health outcomes as a crucial link in the intergenerational transmission of disadvantage, using British data on a cohort of women born in 1958 (the National Child Development Study).

They analyzed the role of maternal endowments and investments (education and smoking in pregnancy) on the probability of having a baby who is small for gestational age. They estimated the total impact of maternal endowments on birth outcomes and analyzed the mechanisms through which they operate. These authors found that cognition affects the health of the newborn primarily through education, personality traits mainly operate by changing smoking behavior, and the physical fitness of the mother has a direct, “biological” effect on being born small for gestational age. Additionally, they estimate the causal effects of maternal choices, and find significant variability in the effects of education and smoking in pregnancy along the distribution of maternal physical traits, which suggests that women with a less healthy physical constitution should be the primary targets of prenatal interventions.

Such evidence shows that the capabilities developed in early childhood may have long-lasting benefits, not only in adulthood but also into the next generation. It also underscores the importance of going beyond a mere collection of treatment effects or correlations between early-life conditions and later-life outcomes to understand the mechanisms through which these interventions operate and their benefits emerge.

Lessons for Health Policy

Three important lessons emerge from this research that should shape future policies to improve the health of the children.

Lesson 1: Develop the Whole Child

To promote the health of children, pediatricians and policy makers should consider their overall well-being by viewing the child in her entirety as a human being in fieri. Currently, health policy in the United States focuses primarily on extending health insurance coverage. Although universal health insurance is an important ingredient in promoting the health of children, it is not the only one. We must also improve the conditions in which children live and promote the diverse capabilities (not only health but also cognition and character traits) that will allow children to become highly adaptive, productive, and healthy adults.

In their quest for accountability in public investments, policy makers must hold themselves accountable for developing the whole child and evaluating progress based on measurements that reflect the full range of capabilities that are essential for success in life and that are highly valued in the labor market. Policy makers have to go beyond tests of cognition as the indicator of child development. They should develop more inclusive measures. A neglected avenue of investigation to promote health is interventions that form these capabilities by exploiting the synergisms among diverse policies. A good health policy may be a good family policy. This argument goes beyond just considering education or nutrition but is consistent with both and integrates these more specialized emphases into a general framework.

Lesson 2: Start Early in Life

We live in an era of substantial and growing social and economic inequality. A large body of research confirms that the accident of birth is a primary source of inequality. Families play a powerful role in creating adult outcomes by shaping the capabilities of children. Health inequalities between the advantaged and the disadvantaged open up early in the lives of children, well before they enter school. Such inequalities are already visible at birth. In fact, they can be detected even before birth. Parental choices and family environments are major causal factors.

Family environments in the United States have deteriorated over the past 40 years. A greater fraction of children is being born into disadvantaged families with fewer parenting resources. At the same time, parents in the top-earning families invest far more in their children than ever before. Because of the growing inequality in parental resources and child-rearing environments, the disparity of resources between the haves and the have-nots has increased substantially. If this trend is not reversed, it will create greater economic and social polarization and health disparities in the next generation. Supplementing at-risk families with quality early childhood development resources can help stem this inequality and promote health.20

Lesson 3: Prevention, Not Remediation

Early intervention is far more effective than later remediation. The capabilities that matter can be created. Child health is not determined solely by family income but also by the parenting resources (the attachment, guidance, and supervision accorded to children, as well as the quality of the schools, neighborhoods, and hospitals surrounding them). Investments in early childhood development can improve cognitive and character traits and the health of disadvantaged children. Such early efforts promote schooling, reduce crime, foster workforce productivity, reduce teenage pregnancy, and develop healthy behaviors. The rates of return on these investments are higher than stock market returns, even in normal times.

The substantial benefit from early investments arises because life cycle skill formation is dynamic in nature. Capabilities cross-foster each other. Early health is critical to this developmental process. A healthy child is ready to engage, will learn more, and is more likely to be a healthy and productive adult. The longer society waits to intervene in the life of a disadvantaged child, the more costly it is to remediate disadvantage in the form of public job training, convict rehabilitation programs, adult literacy programs, or treatment of chronic health conditions. There is no equity-efficiency trade-off for early interventions for the disadvantaged.

Conclusions

Acting on this knowledge requires a paradigm shift. The pediatric health system, developed >50 years ago primarily to cure acute infectious diseases, has to interface and interact with families, schools, and local communities. A shift to primary prevention will require pediatricians to go beyond the current “siloed” policies that provide short-term fixes using separated and limited budgets, toward an integrated approach to child and adult health and development.

Glossary

- ABC

Carolina Abecedarian Project

- BSI

Brief Symptom Inventory

- IPW

inverse probability weighting

- PPP

High/Scope Perry Preschool Project

Footnotes

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the funders or persons named here.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported in part by the American Bar Foundation; the J.B. and M.K. Pritzker Family Foundation; the Buffett Early Childhood Fund; the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grants R37HD065072, R01HD54702) to the Human Capital and Economic Opportunity Global Working Group, an initiative of the Becker Friedman Institute funded by the Institute for New Economic Thinking; and an anonymous funder. We acknowledge the support of a European Research Council grant hosted by University College Dublin (DEVHEALTH 269874).

For example, an obese child is likely to become an obese adult because the metabolic rate is set early in life.

The latter include investments made by parents, teachers, and doctors in the health and development of the child.

Estimates reveal sensitive periods in early life (before age 10) for cognitive capabilities and sensitive periods for behavioral traits through adolescence (Cunha et al 201024).

The treated children had breakfast, lunch, and an afternoon snack at the child-care center and were also given pediatric care.

Childhood health measures are not available for the PPP sample.

Doulas are trained mentors from the community who help young expectant mothers by encouraging healthy prenatal practices, offering support during labor and delivery, and fostering bonds between babies and their parents (Klaus et al 199346).

References

- 1.Heisler EJ. The U.S. Infant Mortality Rate: International Comparisons, Underlying Factors, and Federal Programs (Congressional Research Service Report). Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service; 2012

- 2.Knudsen EI, Heckman JJ, Cameron JL, Shonkoff JP. Economic, neurobiological, and behavioral perspectives on building America’s future workforce. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(27):10155–10162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gluckman PD, Hanson MA. Developmental Origins of Health and Disease. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conti G, Heckman JJ. The Economics of Child Well-Being (Technical Report) Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Almlund M, Duckworth A, Heckman JJ, Kautz T. Personality psychology and economics. In: Hanushek EA, Machin S, Wößmann L, eds. Handbook of the Economics of Education, vol. 4 Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier; 2011:1–181 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Almond D, Currie J. Human capital development before age five. In: Ashenfelter O, Card D, eds. Handbook of Labor Economics. Vol 4B. North Holland, the Netherlands: Elsevier; 2011:1315–1486 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conti G, Heckman JJ. Understanding the early origins of the education-health gradient: A framework that can also be applied to analyze gene-environment interactions. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2010;5(5):585–605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anda RF, Croft JB, Felitti VJ, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and smoking during adolescence and adulthood. JAMA. 1999;282(17):1652–1658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Danese A, Moffitt TE, Pariante CM, Ambler A, Poulton R, Caspi A. Elevated inflammation levels in depressed adults with a history of childhood maltreatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(4):409–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rutter M. Deprivation-Specific Psychological Patterns: Effects of Institutional Deprivation Boston, MA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng X, Wang L, Yang S, et al. Maternal separation produces lasting changes in cortisol and behavior in rhesus monkeys. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(34):14312−14317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Conti G, Hansman C, Heckman J, Novak M, Ruggiero A, Suomi S. Primate evidence on the late health effects of early-life adversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(23):8866−8871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Francis D, Diorio J, Plotsky P, Meaney M. Environmental enrichment reverses the effects of maternal separation on stress reactivity. J Neurosci 2002;22(18)7840−7843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Champagne FA, Francis DD, Mar A, Meaney MJ. Variations in maternal care in the rat as a mediating influence for the effects of environment on development. Physiol Behav. 2003;79(3):359–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheridan M, Fox N, Zeanah C, McLaughlin K, Nelson C. Variation in neural development as a result of exposure to institutionalization early in childhood. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(32):12927–12932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murgatroyd C, Patchev AV, Wu Y, et al. Dynamic DNA methylation programs persistent adverse effects of early-life stress. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12(12):1559–1566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cole SW, Conti G, Arevalo JM, Ruggiero AM, Heckman JJ, Suomi SJ. Transcriptional modulation of the developing immune system by early life social adversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(50):20578–20583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heijmans BT, Tobi EW, Stein AD, et al. Persistent epigenetic differences associated with prenatal exposure to famine in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(44):17046–17049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.McLanahan S. Diverging destinies: how children are faring under the second demographic transition. Demography. 2004;41(4):607–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heckman JJ. Schools, skills and synapses. Econ Inq. 2008;46(3):289–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Slomski A. Chronic mental health issues in children now loom larger than physical problems. JAMA. 2012;308(3):223–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodman A, Joyce R, Smith J. The long shadow cast by childhood physical and mental problems on adult life. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011;108(15):6032−6037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Conti G, Hansman C. Personality and the education-health gradient: A note on “Understanding differences in health behaviors by education” [published online ahead of print October 9, 2012]. J Health Econ. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2012.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cunha F, Heckman JJ, Lochner LJ, Masterov DV. Interpreting the evidence on life cycle skill formation. In: Hanushek EA, Welch F, eds. Handbook of the Economics of Education. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: North-Holland; 2006:697–812 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heckman JJ. The economics, technology, and neuroscience of human capability formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(33):13250–13255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cunha F, Heckman JJ. The technology of skill formation. Am Econ Rev. 2007;97(2):31–47 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sparling J, Lewis I. LearningGames for the First Three Years: A Guide to Parent/Child Play. New York, NY: Berkley Books; 1979 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sparling J, Lewis I. LearningGames for Threes and Fours. New York, NY: Walker and Company; 1984 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heckman JJ, Moon SH, Pinto R, Savelyev PA, Yavitz AQ. The rate of return to the High/Scope Perry Preschool Program. J Public Econ. 2010;94(1–2):114–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Campbell FA, Wasik B, Pungello E, et al. Young adult outcomes of the Abecedarian and CARE early childhood educational interventions. Early Child Res Q. 2008;23(4):452–466 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heckman JJ, Pinto R, Savelyev PA. Understanding the mechanisms through which an influential early childhood program boosted adult outcomes. Am Econ Rev 2012, In press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Muennig P, Schweinhart L, Montie J, Neidell M. Effects of a prekindergarten educational intervention on adult health: 37-year follow-up results of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(8):1431–1437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muennig P, Robertson D, Johnson G, Campbell F, Pungello EP, Neidell M. The effect of an early education program on adult health: the Carolina Abecedarian Project randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(3):512–516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Conti G, Heckman JJ, Moon S, Pinto R. The Long-Term Health Effects of Early Childhood Interventions Unpublished manuscript, University of Chicago, Department of Economics, 2012

- 35.Kitzman H, Olds DL, Henderson CR, Jr, et al. Effect of prenatal and infancy home visitation by nurses on pregnancy outcomes, childhood injuries, and repeated childbearing. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1997;278(8):644–652 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heckman JJ, Moon SH, Pinto R. The Effects of Early Intervention on Abilities and Social Outcomes: Evidences From the Carolina Abecedarian Study Unpublished manuscript, University of Chicago; 2010

- 37.Brown MS, Hurlock JT. Mothering the mother. Am J Nurs. 1977;77(3):438–441 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davidson R, McEwen B. Social influences on neuroplasticity: stress and interventions to promote well-being. Nature Neurosci. 15(5):689–695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Imanaka A, Morinobu S, Toki S, et al. Neonatal tactile stimulation reverses the effect of neonatal isolation on open-field and anxiety-like behavior, and pain sensitivity in male and female adult Sprague-Dawley rats. Behav Brain Res. 2008;186(1):91–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fisher PA, Stoolmiller M, Gunnar MR, Burraston BO. Effects of a therapeutic intervention for foster preschoolers on diurnal cortisol activity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32(8–10):892–905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Conti G, Heckman JJ, Urzúa S. The education-health gradient. Am Econ Rev. 2010;100(2):1–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steinberg L. A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Dev Rev. 2008;28(1):78–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heckman JJ, Kautz T. Hard evidence on soft skills. Labour Econ. 2012;19(4):451–464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heckman JJ, Humphries JE, Kautz T. The GED and the Role of Character in American Life Unpublished manuscript, University of Chicago, Department of Economics; 2012

- 45.Borghans L, Duckworth AL, Heckman JJ, and ter Weel B. The economics and psychology of personality traits. J Human Resources 2008;43:972–1059

- 46.Klaus MH, Kennell JH. The doula: an essential ingredient of childbirth rediscovered. Acta Paediatr 1997;86:1034–1036 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Conti G, Heckman JJ, Pinger P, Zanolini A. Intergenerational Transmission of Inequality: Maternal Endowments, Investments, and Birth Outcomes Unpublished manuscript, University of Chicago, Department of Economics; 2012.