Abstract

This study uses intraindividual variability and change methods to test theoretical accounts of self-concept and its change across time and context, and the developmental implications of this variability. The five-year longitudinal study of 541 youth in a rural Pennsylvania community from 3rd through 7th grade included twice-yearly assessments of self-concept (academic and social), corresponding external evaluations of competence (e.g., teacher-rated academic skills, peer-nominated “likeability”), and multiple measures of youths' overall adjustment. Multiphase growth models replicate previous research, suggesting significant decline in academic self-concept during middle school, but modest growth in social self-concept from 3rd through 7th grade. Next, a new contribution is made to the literature by quantifying the amount of within-person variability (i.e., “lability”) around these linear self-concept trajectories as a between-person characteristic. Self-concept lability was found to associate with a general profile of poorer competence and adjustment, and to predict poorer academic and social competence at the end of 7th grade above and beyond level of self-concept. Finally, there was substantial evidence that wave-to-wave changes in youths' self-concepts correspond to teacher and peer evaluations of youths' competence, that attention to peer feedback may be particularly strong during middle school, and that these relations may be moderated by between-person indicators of youths' general adjustment. Overall, findings highlight the utility of methods sensitive to within-person variation for clarifying the dynamics of youths' self-system development.

Keywords: Self-concept, intraindividual variability, peers, early adolescence

The development of self-cognitions in childhood and adolescence is of enduring interest to developmental scientists because of its key role in motivational structures and behavioral choices (e.g., Bandura, 1997; Deci & Ryan, 2000). Existing studies have often focused on the development of self-concept in terms of increasing cognitive capacities or normative trajectories (e.g., Dweck, 2002; Jacobs, Lanza, Osgood, Eccles, & Wigfield, 2002). Yet theoretical accounts of self-concept formation suggest that, beyond average trajectories, self-concept may also fluctuate. For instance, multiple theories of self-concept posit that individuals incorporate others' evaluations of them into their own self-views, suggesting potential for within-person variability across time and contexts and between-person differences in this self-other correspondence (e.g., Cooley, 1922; Cairns & Cairns, 1988). Although some studies have examined predictors of short-term changes in self-concept (e.g., Gest, Rulison, Davidson, & Welsh, 2008), few have taken advantage of analytic methods sensitive to fluctuations across multiple measurement occasions. Moreover, recent research has demonstrated in several domains (e.g., cognition, affect, self-esteem) that quantification and study of the amount or structure of within-person variability provides a more complete picture of individuals' development (Nesselroade, 1991; Ram & Gerstorf, 2009). The purpose of this study is to delve into the developmental implications of within-person variability in self-concept by matching theories of self-concept and its potential to change across time and context to analytic methods that are sensitive to such changes. In this study, we examine long-term trends in academic and social self-concept from elementary to middle school, explore correlates and consequences of the amount of within-person variability around these trends, and identify attributes of youth and their environment that may account for fluctuations in self-concept.

In the present study, we focus on self-concept (i.e., perceptions of one's own competence) in two fundamental domains of development: academic and social (e.g., Dweck, 2002). Academic self-concept is critical in the development of academic motivation, contributing to school-related values, expectations, and achievement (e.g., Guay, Marsh, & Boivin, 2003). Social self-concept plays important roles in youths' social skill development, social status, peer affiliations, and several internalizing and externalizing symptoms (e.g., Hawley, 2003; Prinstein & La Greca, 2002). More broadly, as youth undergo major developmental and environmental transitions associated with early adolescence, academic and social self-cognitions are important in guiding the paths upon which youth embark (e.g., Bandura, 1997; Deci & Ryan, 2000).

Self-Concept Trajectories

A number of studies have demonstrated, using linear growth curves or other approaches, a normative developmental decline from middle childhood into adolescence across multiple self-concept domains (e.g., math, language arts, sports, and social activities) (e.g., Jacobs et al., 2002; Watt, 2004). Such changes are generally explained by increased cognitive abilities leading to increasingly realistic (and less idealistic) self-views (e.g., Dweck, 2002). Yet declines in self-concept may be especially pronounced during the transition to middle school, as several studies have demonstrated using piecewise linear growth curves (e.g., Midgley, Feldlaufer, & Eccles, 1989; Wigfield, Eccles, Mac Iver, Reuman, & Midgley, 1991). The transition to middle school frequently involves a shift in instructional practices that are mis-matched to early adolescents' developmental needs for competence, autonomy, and relatedness (Connell & Wellborn, 1991; Eccles et al., 1993). Middle school introduces harsher evaluative feedback, less teacher support, and greater focus on performance goals rather than mastery, in turn breeding unfavorable social comparisons and poor motivation, engagement, and learning. These contrasts to elementary school are seen as key sources of the decline in self-concept during middle school (e.g., Mac Iver, Young, & Washburn, 2002; Urdan & Midgley, 2003).

Self-Concept “Lability”

Beyond enduring, directional changes in self-concept, youth may also experience fluctuations in self-concept that are reversible and more rapid, resulting from shorter-term processes (e.g., Nesselroade, 1991). To the extent that the patterns of within-person variability differ across individuals, this can be an important between-person difference in itself worth exploring. For instance, one may measure and investigate “net within-person variability”, conceptualized as an individual's characteristic amount of lability (i.e., unstructured “ups and downs”), and typically operationalized as individually-calculated standard deviations or variances, then examined as a between-person variable (Ram & Gerstorf, 2009).

This idea of quantifying within-person variability and examining its implications has recently received substantial attention in various domains (e.g., Ram & Gerstorf, 2009). For instance, higher lability in cognitive performance has been related to declines in general intelligence and memory (Ram, Rabbitt, Stollery, & Nesselroade, 2005a), and greater lability in affect and psychological well-being has been linked to depression (Gable & Nezlek, 1998). In the self-system domain, global self-esteem lability has been identified as a risk factor for poorer mental health (e.g, Kim & Cicchetti, 2009; Roberts & Kassel, 1997), and linked to poorer overall self-worth and academic adjustment, including low motivation, maladaptive achievement goals, avoidance of challenges, and self-handicapping (Deci & Ryan, 1995; Newman & Wadas, 1997; Waschull & Kernis, 1996).

To date, though, little is known about youths' domain-specific self-concept lability or its relation to developmental correlates or outcomes in those domains. Given that level of self-concept tends to demonstrate reciprocal relations with actual performance and external feedback (e.g., Guay et al., 2003), an important question is raised about the meaning of lability in self-concept for performance and feedback. One study by Amorose (2001) found that lability in physical self-concept negatively predicted motivation toward physical activity. Similarly, day-to-day academic self-concept lability has predicted lower grades a year later (Tsai, 2008). Based upon these and related findings, it has been suggested that high lability (in the self-system and other domains) may be a marker of high vulnerability or reactivity to stressors, while stability may indicate resilience or robustness (e.g., Greve & Enzman, 2003; Waschull & Kernis, 1996).

As described above, between-person differences in lability may reflect an enduring characteristic of an individual child. As such, self-concept lability may be a marker of risk for academic and social adjustment, and may relate to other between-person differences. For instance, externalizing symptoms (e.g., aggression) may elicit mixed feedback from peers and internalizing symptoms (e.g., depression) may make youth particularly reactive to feedback or uncertain about their own abilities. Alternatively, high levels of lability may derive from the environment in which a child's self-views are developing. For instance, middle school introduces major shifts in the sources of external feedback and support, including a grade-level peer network instead of classroom-level, and interaction with multiple teachers per day instead of just one (e.g., Feldlaufer, Midgley, & Eccles, 1988). As such, the middle school transition may make youth particularly “vulnerable”.

Likely driven by both internal and external sources, instability (i.e., “lability”) of self-concept may have important implications for the development of youths' competencies. Self-concept is meant to form a coherent meaning system with values, expectations, and achievement during early adolescence (Dweck, 2002); a labile self-concept may hinder this process. For instance, inconsistent self-concepts may make it difficult for youth to form sound, realistic expectations of what challenges they can handle or how to do so. Similarly, to the extent that labile self-concepts correspond to or reflect actual fluctuations in youths' engagement, interest, and performance (Deci & Ryan, 1995; Harter, 1999), these various levels of cognitive, affective, and behavioral inconsistency may impede long-term skill development (Kernis, 2003). Thus far, we can only extrapolate from related literature; the tendency for self-concept to become more or less labile during middle school and the meaning of short-term fluctuations in self-concept for youths' longer-term skill development are largely unknown.

Self-Other Correspondence

Why might self-concept vary from occasion to occasion? The historical “looking glass self” perspective (Cooley, 1922) still endorsed in modern theories argues that self-views are formed in part by internalizing others' perceptions of oneself (e.g., Crocker & Knight, 2005). In other words, self-concept fluctuations may result from inconsistency across time or context in the external feedback that youth receive about their academic and social competence. This process may be particularly relevant during early adolescence: the cognitive capacity to incorporate others' perceptions into one's own self-concept develops at this time and coincides with a developmental peak in youths' concerns about how they are perceived (Bukowski, Sippola, & Newcomb, 2000; Dweck, 2002). Consistent with this notion, the majority of an adolescent sample in a study by Harter (1999) reported using a “looking glass self” orientation. From a developmental perspective, then, self-other correspondence that results from the incorporation of others' views into one's self-concept is particularly likely as youth begin adolescence.

As further support for “looking glass self” processes, two previous examinations of the dataset used in the present study have demonstrated (at a between-person level) that changes in academic self-concept can be uniquely predicted by previous-wave teacher ratings of academic skill and peer nominations of academic ability, termed peer academic reputation (or “PAR”) (Gest, Domitrovich, & Welsh, 2005b; Gest et al., 2008). Similarly, in other studies, changes in social self-concept have been predicted by teacher or parent ratings of youths' social competence and peer acceptance, as well as by indices of “likeability” and “social prominence” created from peers' reports of which classmates they like and dislike (Cillessen & Bellmore, 1999; Cole, 1991). The latter approach is viewed as the most ecologically valid assessment of youths' social status: likeability or Social Preference refers to the frequency of “liking nominations” relative to the frequency of “disliking” nominations, and social prominence or Social Impact represents the degree to which a child elicits strong reactions from peers, whether positive or negative (e.g., Coie, Dodge, & Coppotelli, 1982). These two key status dimensions have each been uniquely related to social self-concept (e.g., Newcomb & Bukowski, 1983; Lease, Musgrove, & Axelrod, 2002).

Typically, relations between self-concepts and external evaluations of youths' competence are viewed as reciprocal: while short-term changes in external feedback may drive changes in self-concept, it is also likely that fluctuations in feedback result from ups and downs in self-concept For instance, longstanding theories of achievement motivation and supporting evidence suggest that academic self-concept predicts achievement in school through its effects on youths' values and self-expectations. When youth have low expectations for success, they are less likely to pursue challenges that may help to improve their skills (e.g., Deci & Ryan, 1995; Eccles et al., 1983); in turn, skill development may suffer, as do teacher and peer perceptions of youths' skill level (Guay et al., 2003). Moreover, the normative grading systems typical of middle school heighten youths' awareness of how they “measure up” to their peers (e.g., Eccles et al., 1993; Mac Iver et al., 2002). To the extent that low self-concept manifests in youths' behaviors, peer perceptions of youths' competence are especially likely to match up with youths' self-concepts during this period. The “power” of self-concept to shape effort, achievement, and external feedback, then, provides another reason to expect covariation of these constructs over time. In sum, we expect self-other correspondence, likely resulting from bi-directional feedback loops between self-concept and observed competence, especially during middle school.

Though substantial evidence supports a link between self-concept and external indicators of competence, much potential also exists for between-person differences in the extent of self-other correspondence. Self-concept may manifest to varying degrees in observable behaviors, and evaluative feedback is filtered through potentially biased perceptions of that feedback (e.g., Harter, 1999; John & Robins, 1994). One such bias is referred to as “contingent” self-esteem, in which youths' self-worth is highly dependent upon external validation (Crocker & Knight, 2005). Contingent self-esteem involves heightened sensitivity to feedback and a tendency to perceive feedback as inconsistent; the result is more unstable self-views, avoidance of challenges, and poorer mental health (e.g., Deci & Ryan, 1995; Kernis, 2003). In other words, youth with this type of bias may be especially prone to self-concept lability and strong self-other correspondence. Alternatively, some youth may simply perceive others' reactions to them through consistently positive or negative lenses.

The final task, then, is to identify factors that may explain such “biases” or between-person differences in self-other correspondence. Some research suggests that girls tend to evaluate themselves more harshly, and are more likely than boys to view evaluative feedback as diagnostic of their ability (e.g., Pomerantz, Altermatt, & Saxon, 2002). Similarly, depression, ADHD, and other mental health problems are frequently linked to biased and/or more labile self-views, which are likely to affect both the “impact” of external feedback on self-concept and the ways others perceive and react to them (e.g., Hoza et al., 2004; Ward, Sylva, & Gresham, 2010). Given the existing evidence, we expect between-person differences in self-other correspondence, accounted for in part by gender and mental health indices.

The Present Study

In the present study, we use contemporary methods for examining within-person change, variability, and covariation to answer three questions. First, do youth, on average, experience a decline in self-concept over the middle school transition? Replicating previous research, we expected a linear decline in academic and social self-concept directly following entry to middle school. Second, does self-concept lability differ between elementary and middle school, and does it relate to youths' academic and social adjustment and overall mental health? We expect that self-concept lability will be greater following the transition to middle school. Further, we expect greater lability to be associated with a profile of poorer academic, social, and overall adjustment, and for self-concept lability to be uniquely predictive of lower competence in 7th grade. Third, do short-term fluctuations in self-concept correspond with fluctuations in teacher and peer evaluations, and is self-other correspondence moderated by school level (elementary versus middle school) and between-person differences? We expect self-other correspondence to be strongest during middle school, and to be moderated by gender and “proxies” of mental health, including self-worth, loneliness, poor attention, victimization, and aggression.

Methods

Data were drawn from a five-year (2001-2006) cohort-sequential longitudinal study investigating youths' peer networks and academic and social adjustment producing 10 waves (2 assessments per year) of data (see Gest et al., 2005b; 2008) for a complete description of the procedures).

Participants & Procedure

Participants were initially enrolled in grades 3, 4, or 5 in one elementary school located in a small, working-class community in central Pennsylvania (with all youth moving into the same middle school at the beginning of 6th grade). Beginning in the Fall of 2001, all students were assessed in October and May of each school year until completing 7th grade. Researchers sought parental consent at each assessment, providing parents with a form to sign and return if they did not want their child to participate. Students completed a survey administered in their classroom lasting approximately 45 minutes, while supervised by the researchers.

Across waves, 92 to 95% of students enrolled in the targeted grades provided data, yielding a sample of 541 students (251 girls). Attrition was minimal: of the full, N = 541 student sample, 459 provided data at three or more waves. Because each cohort of students began contributing data at a different grade level (i.e., 3rd, 4th, 5th), the number of waves of data varies per cohort; see Table 1 for sample sizes by cohort and grade level. Almost all students (99%) were Caucasian, reflecting demographics of the larger community. Distributions of standardized reading and math assessment scores for 5th graders at the school closely matched the distribution for 5th graders statewide. Rates of several social problems (such as poverty and school dropout) exceeded state averages. This profile is typical of rural communities (where nearly a third of U.S. children attend public school; Johnson & Strange, 2007).

Table 1. Sample Sizes Examined in the Present Study, Summarized by Cohort (Beginning in 3rd, 4th, and 5th grade, respectively) and Semester in School.

| 3rd | 4th | 5th | 6th | 7th | Total per cohort | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Fall | Spr | Fall | Spr | Fall | Spr | Fall | Spr | Fall | Spr | Present at any wave | |

| Cohort 1 | 141 | 141 | 150 | 146 | 149 | 141 | 166 | ||||

| Cohort 2 | 150 | 150 | 160 | 161 | 164 | 164 | 163 | 163 | 185 | ||

| Cohort 3 | 152 | 152 | 147 | 148 | 145 | 148 | 156 | 156 | 163 | 158 | 190 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Total per wave | 152 | 152 | 297 | 298 | 446 | 450 | 470 | 466 | 475 | 462 | 541 |

Measures

Self-report measures were used to assess youths' self-concepts, and were examined in relation to corresponding peer and teacher evaluations of competence. Several proxies of mental health and overall adjustment were also derived from peer, teacher, and self-reports. Summary descriptives are provided in Table 2.

Table 2. Means and Standard Deviations of Academic and Social Self-Concept and Self, Teacher, and Peer Reports Examined in Relation to Self-Concept.

| Child self-ratings | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic Self-Concept | Social Self-Concept | Self-worth | Loneliness | ||

|

|

|||||

| Fall of 3rd grade | 3.09 (.72) | 3.07 (.78) | 3.22 (.71) | 1.72 (.95) | |

| Spring of 3rd grade | 3.05 (.73) | 3.04 (.74) | 3.25 (.69) | 1.93 (1.14) | |

| Fall of 4th grade | 3.11 (.71) | 3.14 (.78) | 3.28 (.66) | 1.64 (.91) | |

| Spring of 4th grade | 3.19 (.74) | 3.20 (.78) | 3.31 (.67) | 1.71 (1.02) | |

| Fall of 5th grade | 3.11 (.74) | 3.21 (.75) | 3.34 (.69) | 1.66 (.92) | |

| Spring of 5th grade | 3.17 (.73) | 3.21 (.78) | 3.32 (.72) | 1.70 (.96) | |

| Fall of 6th grade | 3.18 (.73) | 3.28 (.74) | 3.38 (.66) | 1.62 (.91) | |

| Spring of 6th grade | 3.12 (.77) | 3.25 (.74) | 3.32 (.71) | 1.64 (.90) | |

| Fall of 7th grade | 3.13 (.73) | 3.28 (.74) | 3.39 (.66) | 1.64 (.85) | |

| Spring of 7th grade | 3.04 (.77) | 3.34 (.70) | 3.30 (.69) | 1.68 (.89) | |

|

| |||||

| Teacher ratings of child | |||||

| Academic Skills | Soc. Engagement | Aggression | Attention | ||

|

|

|||||

| Fall of 3rd grade | 3.66 (.92) | 4.06 (.79) | 1.42 (.79) | 3.74 (.98) | |

| Spring of 3rd grade | 3.76 (1.00) | 4.03 (.76) | 1.62 (.92) | 3.64 (1.05) | |

| Fall of 4th grade | 3.70 (.84) | 4.08 (.69) | 1.38 (.59) | 3.80 (.95) | |

| Spring of 4th grade | 3.76 (.93) | 4.24 (.67) | 1.39 (.58) | 3.77 (.98) | |

| Fall of 5th grade | 3.47 (.92) | 3.92 (.72) | 1.51 (.74) | 3.59 (1.00) | |

| Spring of 5th grade | 3.48 (.92) | 3.99 (.75) | 1.60 (.78) | 3.64 (.98) | |

| Fall of 6th grade | 3.71 (.98) | 4.24 (.76) | 1.46 (.74) | 3.80 (.99) | |

| Spring of 6th grade | 3.72 (.99) | 4.19 (.82) | 1.54 (.74) | 3.80 (.98) | |

| Fall of 7th grade | 3.26 (.70) | 3.56 (.63) | 1.60 (.70) | 3.51 (.85) | |

| Spring of 7th grade | 3.30 (.83) | 3.63 (.66) | 1.62 (.77) | 3.47 (.91) | |

|

| |||||

| Peer nomination scores | |||||

| Peer academic reputation | Social Preference | Social Impact | Aggression | Victimization | |

|

|

|||||

| Fall of 3rd grade | 0 (1.56) | 0 (1.61) | 0 (1.06) | 0 (.93) | 0 (.81) |

| Spring of 3rd grade | 0 (1.54) | 0 (1.58) | 0 (1.11) | 0 (.87) | 0 (.80) |

| Fall of 4th grade | 0 (1.55) | 0 (1.60) | 0 (1.06) | 0 (.90) | 0 (.80) |

| Spring of 4th grade | 0 (1.54) | 0 (1.61) | 0 (1.05) | .01 (.89) | 0 (.78) |

| Fall of 5th grade | 0 (1.51) | 0 (1.63) | 0 (1.03) | .01 (.92) | 0 (.88) |

| Spring of 5th grade | 0 (1.55) | 0 (1.65) | 0 (.97) | 0 (.89) | 0 (.85) |

| Fall of 6th grade | 0 (1.52) | .01 (1.43) | 0 (1.31) | 0 (.96) | 0 (.93) |

| Spring of 6th grade | 0 (1.54) | -.03 (1.50) | -.01 (1.26) | 0 (.93) | - .01 (.88) |

| Fall of 7th grade | 0 (1.43) | 0 (1.53) | -.02 (1.34) | 0 (.93) | 0 (.97) |

| Spring of 7th grade | 0 (1.46) | .03 (1.53) | .01 (1.31) | 0 (.94) | .01 (1.02) |

Note: Each cell presents the mean value, with standard deviations in parentheses

Self-reports

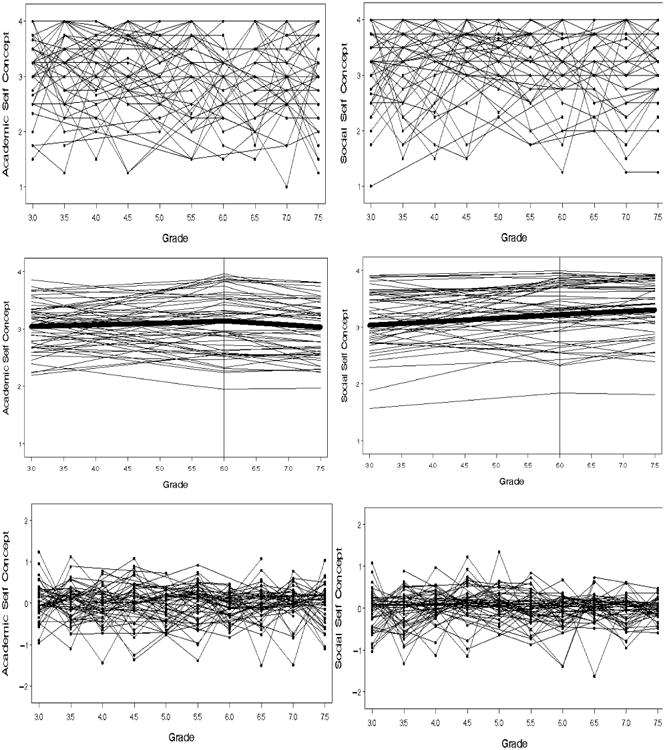

Students responded to items drawn from Harter's well-validated Self-Perception Profile for Children to assess academic self-concept, social self-concept, and general self-worth (Harter, 1982). Students chose which of two statements was “more true” for them, then indicated whether the statement was “sort of true” or “really true”. Items formed internally consistent composite scales within each wave1. The four statements corresponding to Academic Self-Concept were: feel very good at their school work; feel just as smart as other kids their age; almost always figure out the answers; and do very well in their class work (M=3.04 to 3.19 on the 1 to 4 scale; α = .57 to .85). The four Social Self-Concept items were: find it easy to make friends; have lots of friends; feel that most kids like them; popular with others their age (M=3.02 to 3.34; α = .65 to .84). The four Self-Worth items were: happy with the way they do things; happy with themselves most of the time; like the way they are leading their life; like the kind of person they are (M=3.21 to 3.39; α = .59 to .82). Raw data are plotted in the top panel of Figure 1, representing wave-to-wave changes in academic and social self-concept. Students also responded to three items selected from the ILQ (Asher, Hymel, and Renshaw, 1984) to assess Loneliness: “I feel alone”, “I feel lonely”, and “I feel left out of things”. Children indicated on a five-point scale how much each statement was true of themselves (ranging from “not true at all” to “always true”; M=1.62 to 1.93, α = .79 to .89 across waves).

Figure 1.

All figures represent within-person changes in academic self concept (left) and social self-concept (right) from 3rd through 7th grade for the same subsample of 50 youth, in the form of: raw data (Top); two phase linear growth curves, in which the bold lines represent the average linear growth trends, thin lines represent individuals' predicted linear growth trends, and the vertical line at the beginning of grade 6 represents the transition point tested (Middle); and individuals' residuals around their linear growth curves (Bottom).

Teacher ratings

Teachers rated the degree to which they agreed or disagreed with each of 32 statements describing students' adjustment (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Items assessing Academic Skills were expanded from a scale used in the ICS-TF (Cairns, Leung, Gest, & Cairns, 1995) to assess four core curricular areas of competence: good at reading; good at math; good at writing; good at science (M=3.26 to 3.76; α = .86 to .93 across waves). Good reliability (internal consistency and stability) and convergent and discriminant validity of this expanded version of the scale were demonstrated in our previous examination of the measure (see Gest et al., 2005b). Items assessing Social Engagement, Aggression, and Attention were all drawn from the well-validated and widely used Social Health Profile (CPPRG, 1999). Social Engagement items included: friendly; plays with others; avoids social contact (reversed); initiates interactions with peers; helpful to others; has social contact with others (M=3.56 to 4.24; α = .86 to .93). Aggression items included: teases classmates; breaks rules; harms others; trouble accepting authority; fights (M=1.38 to 1.62; α = .87 to .93). Attention items included: concentrates; completes assignments; easily distracted (reverse scored); doesn't pay attention (reverse scored); stays on task (M=3.48 to 3.80; α = .92 to .94).

Peer nominations

Students were asked to identify classmates that they “liked most” and “liked least”, and those that matched each of 12 behavioral descriptors. Following widely recommended practices used in the peer assessment literature (see Cillessen & Bukowski, 2000), students were provided with a class roster and were free to list as many or as few peers as they wished. Because students change classes throughout the day in middle school, these assessments were accompanied with a grade-level roster. Each item was standardized within classroom (or grade-level in middle school) and gender to account for varying peer network size and sex distribution; nominations thus represent each student's relative standing in his or her peer network, allowing comparisons across classrooms and grade levels (see Coie, Dodge, & Coppotelli, 1982; Gest et al., 2005b).

Number of raw nominations received for “liked most” ranged from 0 to 20, with an average of 3.6 nominations; number of nominations received for “liked least” ranged from 0 to 67, with an average of 2.21. Following standard practice (see Coie et al., 1982), standardized peer nominations were used to compute two indices of social status. Social Preference scores were calculated as the difference between the standardized “liked most” and “liked least” scores, representing how well-liked a student is overall (e.g., do positive nominations outnumber negative?) To also account for the difference between neglected youth (i.e., no nominations of liking or disliking) and controversial youth (i.e., many nominations of each type), we also computed Social Impact scores as the sum of standardized “liked most” and “liked least” scores, to represent youths' prominence in his or her network. While raw nominations of one type (i.e., liking or disliking) cannot be usefully interpreted without the other, each composite score represents a conceptually meaningful and distinct aspect of social experience. Moreover, computing composite peer scores from oppositely highly skewed “liked most” and “liked least” scores produces indices that are relatively normally distributed and thus conform well to standard assumptions of most analyses. Social Preference scores ranged from -9.36 to 4.36, and Social Impact scores range from -3.15 to 7.71; both, by definition, with a mean score of 0.

Peer Academic Reputation (PAR) scores were similarly calculated from four of the peer-nominated behavioral descriptor items: Good at reading (mean number of nominations = 2.27, ranging from 0 to 21 nominations), Not good at reading (M=1.42, range = 0 to 21), Almost always knows the right answer when the teacher asks a question (M=1.93, range = 0 to 23), and Almost never knows the right answer when the teacher asks a question (M=1.18, range = 0 to 16 nominations). Following standard practice (see Gest et al., 2005b), the two negatively worded and two positively worded items were each averaged separately, and standardized within classroom and gender. Consistent with the approach used to calculate Social Preference scores, composite PAR scores were computed as the difference between the positive and negative reputation scores, producing a nearly normally distributed index. PAR scores ranged from -7.48 to 6.82.

Victimization scores were derived from peer nomination items: “gets hit or pushed a lot” (M=.63, ranging from 0 to 57 nominations) and “gets picked on a lot” (M =.92, range = 0 to 59); and Peer-nominated Aggression scores were derived from the peer nomination items: “starts fights” (M=1.26, range = 0 to 55); “picks on other kids a lot” (M=1.16, range = 0 to 50). After standardizing nominations within class (or grade) and gender, items were averaged to create composite Victimization (range = -1.36 to 10.55), and Aggression scores (range = 1.34 to 6.97).

Data Analysis

To address our research questions about within-person change and variability in self-concept we used a variety of analytic methods for examining longitudinal data, including multilevel models of change (i.e, growth models), intraindividual residual variances, and linear regression analyses. All models were fit to the data using SAS (e.g., Proc Mixed and Proc GLM). Incomplete data were treated according to standard missing at random assumptions in the growth curve models and analyses of self-other correspondence, and as missing completely at random (MCAR) in the calculation of lability scores. Importantly, the main reason for missing data was the research design (e.g., not measuring all cohorts in 3rd grade because access to participants was not available when the older students were in 3rd grade), not because of participants' characteristics, further justifying the MCAR treatment (Little & Rubin, 1987). Additional tests for possible cohort effects provided no evidence that the cohorts differed in a meaningful way during the overlapping spans of observation.

Self-concept trajectories

A two-phase growth model was used to address our first research question: we examine long-term within-person changes in self-concept and a hypothesized decline during middle school. Time – or semester in school (fall of 3rd through spring of 7th grade) – was entered to examine linear and quadratic change. Interactions of a dichotomous “middle school” variable with both time variables were entered to test the possible difference of rates of change between the elementary and middle school years.

Self-concept lability

The second research question focused on correlates of academic and social self-concept lability. For each individual, we examined the residuals from the growth curves fit above. Intraindividual standard deviations of these residuals were used to quantify each child's self-concept lability (a new between-person difference variable). A t-test was computed to determine whether self-concept lability differed between elementary and middle school. Overall lability scores were then correlated with individual mean levels of self-concept, corresponding teacher and peer evaluations of competence, and the mental health proxy variables. Finally, lability scores were used in regression equations to predict academic and social competence at the end of 7th grade, after controlling for youths' average self-concept.

Self-other correspondence

To address the third research question, teacher and peer evaluations of academic and social adjustment were added as time-varying predictors to the growth curve model described above. Self-other correspondence was quantified as the extent of association between the ongoing evaluations of competence and individuals' self-concepts. Semester (fall or spring of 3rd through 7th grade) and school-level (elementary or middle school) were interacted with the time-varying indices to examine change in correspondence over time. Lastly, gender, mean levels of external evaluations, and mental health indicators were examined as potential moderators of the self-other correspondence.

Results

Self-concept trajectories

The first2 task of the present study was to identify the normative long-term developmental trends in academic and social self-concept from middle childhood through early adolescence, and to test whether the transition to middle school (at fall of Grade 6) coincided with a decline in youths' self-concept trajectories. A growth curve (i.e., multilevel) model, in which academic and social self-concept are modeled as a function of semester (i.e., linear and quadratic change over time), school-level, and an interaction of school-level with both time variables, was used to model between-person differences in within-person change. The interaction of the school-level with each of the time variables was included to capture potential differences in the rate of change in self-concept associated with the middle school transition. The model is effectively a two-phase growth model, specified as:

| Level 1 |

where Self-Conceptti, child i's self-concept at time t, is a function of an individual-specific intercept parameter that captures their level of self-concept, β0i, at gradeti = 0, here centered at fall of 6th grade (entry to middle school), individual-specific slope parameters that capture associations of grade and school level with self concept, β1i through β5i, and residual error, eti. Consistent with standard growth modeling procedures (McArdle, 2009; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002; Singer & Willet, 2003), individual specific intercepts and slopes from Level 1 were modeled at Level 2 as:

In these models, γ00 is the average intercept, γ10 and γ20 are the average linear and quadratic change, respectively, γ30 is the average main effect of middle school, γ40 and γ50 are the average linear and quadratic time × middle school interaction effects, respectively, and u0i through u5i are individual-specific deviations from those means. After initial fitting, non-significant effects were trimmed for parsimony. According to standard assumptions of multilevel models, interindividual differences were assumed normally distributed, correlated with each other, and uncorrelated with the residual errors.

Using this two-phase linear growth model of development, we assessed evidence for an overall developmental trend in children's self-concept across the observation period, differences in this developmental trend between elementary and middle school, and the extent of interindividual differences in these trends. Parameter estimates and fit statistics for final models are presented in Table 3. All quadratic terms were non-significant3, and were therefore trimmed from the final models. We discuss the specific parameters most relevant to interpretation of developmental changes here. See middle panels of Figure 1 for plots of the average linear trajectory as well as predicted individual linear trajectories for academic and social self-concept among a subsample of 50 youth. In line with expectations and past research using piecewise growth curves, there was evidence of a significant (though modest) deflection from a flat to a downward trajectory in academic self-concept upon entry to middle school, as represented by the significant time × middle school interaction (γ30 = -.10, p< .01). Further, there were significant interindividual differences in the extent of this deflection (σ2u3 = .12; p< .001), with some individuals greatly affected by the transition and others less so. For social self-concept, there was a significant (though modest) linear increase, on average, across the full span of the study (γ10 = .06, p< .01), with no significant effects of the transition to middle school on average developmental trajectory (γ30 = -.01). However, there were again significant interindividual differences in the extent of deflection to individuals' trajectories (σ2u3 = .12; p< .001).

Table 3. Two-Phase Growth Curve Models for Academic and Social Self-Concept Representing Development from 3rd through 7th Grade and across the Middle School Transition.

| Academic Self-Concept | Social Self-Concept | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | |

| Fixed effects estimates | ||||

| Intercept, γ00 | 3.13* | .04 | 3.22* | .04 |

| Grade in School, γ10 | .03 | .02 | .06* | .02 |

| Middle School, γ20 | .01 | .03 | <.01 | .03 |

| (Grade in School)(Middle School), γ30 | -.10* | .03 | -.01 | .03 |

| Random effects estimates | ||||

| Variance intercept, σ2u0 | .41* | .03 | .41* | .03 |

| Variance grade in school, σ2u1 | .05* | .01 | .05* | <.01 |

| Variance (grade)(middle school), σ2u3 | .12* | .03 | .12* | <.01 |

| Covariance intercept, grade in school, σu0u1 | .08* | .01 | .06* | .01 |

| Covariance intercept, (grade)(middle school), σu0u3 | -.13* | .03 | -.12* | .03 |

| Covariance grade, (grade)(middle school), σu1u3 | -.06* | .01 | -.05* | .02 |

| Residual variance, σ2e | .22* | .01 | .21* | .01 |

| -2 Log Likelihood (-2LL) | 5700.2 | 5653.8 | ||

Note6: SE = standard error;

= p< .05

Self-concept lability

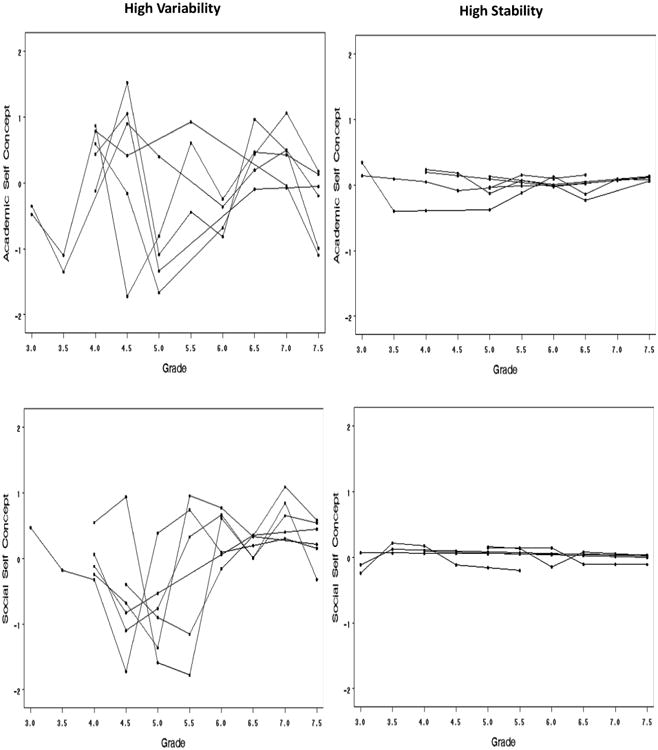

The second task of the present study was to test whether self-concept lability differed between elementary and middle school, and to examine relations between self-concept lability and external indicators of youths' adjustment. In the above analysis, we in essence extracted long-term linear trends associated with development and the middle school transition (Figure 1, middle) from the raw within-person changes in academic and social self-concept (Figure 1, top). The “leftover” or residual changes across time are shown in Figure 1 (bottom). We quantified the amount of within-person variability in “leftover” changes (for anyone who provided at least three waves of data) for each child as the standard deviation of their residuals. We used this quantification to operationalize between-person differences in self-concept lability. Examples of between-person differences are highlighted by the purposively selected subsample of six relatively labile and six relatively stable youth shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

A subsample of six highly variable (left) and six highly stable youth (right) for academic self-concept (top) and social self-concept (bottom) were selected to depict the range of between-person differences in within-person self-concept “lability”. These figures replicate the concept represented in the bottom panel of Figure 1 (individual residuals around their own linear growth curves), but display a handpicked subsample of youth who best demonstrate the between-person differences.

To test whether lability was greater during middle school, we used the same approach described above to compute self-concept lability separately for elementary and middle school. Contrary to expectations, average academic self-concept lability scores from comparable samples4 of elementary (M=.31, SD=.21) and middle school (M=.28, SD=.20) students did not significantly differ (t=1.30, p>.05; correlation between elementary and middle school academic self-concept lability scores were r=.15, p>.10). However social self-concept lability was, on average, greater in elementary school (M=.28, SD=.21) than in middle school (M=.21, SD=.18) (t=3.69, p<.05; correlation between elementary and middle school social self-concept lability scores were r=.17, p<.05).

Next, we examined whether between-person differences in self-concept lability (assessed over the full data stream; elementary + middle school) were related to other indicators of youths' adjustment. Table 4 presents correlations between academic and social self-concept lability and (a) mean levels of academic and social adjustment, and (b) mean levels on the mental health proxy indicators. Consistent with our hypotheses, greater lability in academic self-concept was associated with overall lower academic adjustment (mean academic self-concept, r = -.20, p<.001; mean teacher-rated skills, r = -.17, p<.001; mean PAR, r = -.22, p<.001). Moreover, correlations between academic self-concept lability and several of the mental health proxy variables, including self-worth (r=-.16, p<.001), loneliness (r=.15, p<.01), peer victimization (r=.15, p<.01), and teacher-rated attention (r= -.15, p<.001) suggest that academic self-concept lability is also a marker of poorer overall adjustment or mental health. Similarly, lability in social self-concept was associated with lower mean social self-concept (r = -.28, p<.001), teacher-rated social engagement (r = -.13, p<.001), and social preference (r = -.21, p<.001), and to lower self-worth (r=-.22, p<.001), poorer attention (r= -.10, p<.05), and higher levels of loneliness (r=.24, p<.001) and peer victimization (r=.15, p<.01)5. Overall, as hypothesized, greater self-concept lability was associated with a profile of poorer adjustment.

Table 4. Correlations of Self-Concept Lability with Mean Levels of Self-Concept, External Evaluations of Competence, and Mental Health Proxy Variables.

| Academic Competence | Social Competence | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| 1. Self-Concept iLability | 2. Self-Concept iMean | 3. Teacher-rated Academic Skills iMean | 4. Peer Academic Reputation iMean | 1. Self-Concept iLability | 2. Self-Concept iMean | 3. Teacher-ratedSocial Engagement (iMean) | 4. Peer-nominated Social Preference iMean | 5. Peer-nominated Social Impact iMean | |

| Competence | |||||||||

| Mean Levels (iMean) | |||||||||

| 2. Self-Concept | -.20* | -- | -.28* | -- | |||||

| 3. Teacher-rated Competence | -.17* | .52* | -- | -.13* | .31* | -- | |||

| 4. Peer-nominated (PAR/Social Preference) | -.22* | .50* | .76* | -- | -.21* | .43* | .47* | -- | |

| 5. Peer-nominated (Social Impact) | -.05 | .10* | .18* | -.02 | -- | ||||

| Mental health “proxy” | |||||||||

| Mean Levels (iMean) | |||||||||

| Self-worth | -.16* | .75* | .33* | .33* | -.22* | .69* | .29* | .27* | .08 |

| Self-rated Loneliness | .15* | -.45 | -.20* | -.26* | .24* | -.60* | -.22* | -.36* | .01 |

| Peer-nominated Victimization | .15* | -.14* | -.19* | -.40* | .15* | -.35* | -.24* | -.69* | .40* |

| Peer-nominated Aggression | .06 | -.14* | -.22* | -.30* | .04 | .01 | -.08 | -.34* | .50* |

| Teacher-rated Aggression | .03 | -.25* | -.40* | -.37* | .05 | -.07 | -.33* | -.39* | .23* |

| Teacher-rated Attention | -.15* | .49* | .75* | .71* | -.10* | .21* | .52* | .48* | -.06 |

Note: Correlations are between lability and mean levels of self-concept and competence in academic domain (top left), social domain (top right), and mental health (bottom); “iMean” = individual-level within-subject mean across time, “iLability” = individual-level lability, calculated as the within-subject standard deviation of residuals around each child's own growth curve; Bolded values are used to highlight the correlations of self-concept lability with mean levels of self-concept, competence, and mental health variables;

= p<.05.

Having established these associations, we tested whether between-person differences in amount of self-concept lability were predictive of between-person differences in teacher and peer evaluations of competence at the end of 7th grade (the final wave of the study) above and beyond prediction by mean self-concept. Specifically, we regressed each of these 7th grade “outcomes” on the self-concept lability scores, controlling for individuals' mean self-concept. As shown in Table 5, academic self-concept lability was negatively predictive of teacher ratings of academic skills (β =-.82, p< .01) and PAR (β =-1.99, p< .001) at the end of 7th grade, even after controlling for individuals' mean levels of academic self-concept (β =.13, p< .001; β =.26, p< .001, respectively). Similarly, social self-concept lability negatively predicted social preference (β = -1.38, p<.001), social impact (β = -.87, p<.01), and social engagement (β = -.63, p<.001) at the end of 7th grade, also after controlling for individuals' mean self-concept (β =.30, β =.10, β =.06, respectively). Results provide further evidence that greater self-concept lability is associated with multiple indicators of poorer social and academic competence.

Table 5. Regression Models Predicting Evaluations of Competence at the End of 7th Grade from Self-Concept Mean and Lability.

| Dependent Variables: | Estimate | Standard Error |

|---|---|---|

| Academic Competence | ||

|

| ||

| Teacher-rated Academic Skills (7th grade) | ||

|

| ||

| Intercept | 3.10* | .15 |

| Within-person “Mean” Academic Self-Concept | .13* | .04 |

| Within-person “Lability” in Academic Self-Concept | -.82* | .25 |

|

| ||

| Peer Academic Reputation (7th grade) | ||

|

| ||

| Intercept | -.30 | .25 |

| Within-person “Mean” Academic Self-Concept | .26* | .06 |

| Within-person “Lability” in Academic Self-Concept | -1.99* | .40 |

|

| ||

| Social Competence | ||

|

| ||

| Teacher-rated Social Engagement (7th grade) | ||

|

| ||

| Intercept | 3.61* | .12 |

| Within-person “Mean” Social Self-Concept | .06 | .03 |

| Within-person “Lability” in Social Self-Concept | -.63* | .18 |

|

| ||

| Peer-nominated Social Preference (7th grade) | ||

|

| ||

| Intercept | -.62* | .26 |

| Within-person “Mean” Social Self-Concept | .30* | .07 |

| Within-person “Lability” in Social Self-Concept | -1.38 | .40 |

|

| ||

| Peer-nominated Social Impact (7th grade) | ||

|

| ||

| Intercept | -.07 | .23 |

| Within-person “Mean” Social Self-Concept | .10 | .06 |

| Within-person “Lability” in Social Self-Concept | -.87* | .35 |

Note: Bolded values were used to highlight for the reader the terms of greatest relevance to the research questions (i.e., the self-concept lability terms);

= p< .05.

Self-other correspondence

In our final analysis, we examined within-person relations between self-concept and external evaluations of competence, and how this correspondence was moderated by grade-level, school-level, gender, and between-person differences in external evaluations of competence and multiple proxy indicators of mental health. To set up the model, we computed time-invariant (person-level) mean or “overall” scores for each academic and social competence variable to represent between-person differences, and time-varying (occasion-level) deviation or “occasion-specific” scores to represent within-person variation in indices of academic and social competence (see Hoffman & Stawski, 2009). Specifically, overall scores for teacher-rated academic skills and social engagement, and peer nomination-based PAR, social preference, and social impact were computed as youths' intraindividual means across assessments, and centered at the sample means. Occasion-specific scores were then computed as individuals' deviations from their own mean (once again centered at the sample mean). Overall scores were also computed for self-worth, loneliness, attention, victimization, and teacher and peer evaluations of aggressive behavior.

All of these scores were introduced into the original two-phase linear growth model. Within-person predictors were added at Level 1. For academic self-concept, occasion-specific academic skills and PAR were included to test whether wave-to-wave fluctuations in academic self-concept coincide with occasion-specific external feedback from teachers and peers. Similarly, for social self-concept, occasion-specific social engagement, social preference, and social impact were added to Level 1 to examine covariation of social self-concept with teacher and peer scores. Each occasion-specific score was then interacted with grade-level and school-level to test changes over time in self-other correspondence. Thus, Level 1 was specified as:

such that β4i represents the within-person correspondence between self- and teacher perceptions of competence, β5i (and an additional β6i in the social self-concept model, to represent the second peer score) represent the self-peer correspondence in perceptions of competence, and β6i through β9i (with an additional β10i and β11i in the social self-concept model) represent the moderation of self-other correspondence by grade-level and school-level.

At Level 2, between-person predictors (gender and overall competence and mental health scores) were added to control for the role of between-person differences in explaining youths' levels of self-concept, and to test for moderators of growth and the self-other correspondence. Thus, Level 2 was specified as:

In these Level 2 equations, γ00 through γ90 represent the sample mean of each coefficient described above, γ01 through γ51 represent the moderation of each effect by gender, γ02 through γ52 represent moderation of the effects by overall teacher ratings, γ03 through γ53 represent moderation by overall peer nominations, and γ04- γ08 through γ54– γ58 represent moderation by overall mental health scores. Lastly, u0i through u9i indicate that each of these coefficients was allowed to vary across individuals (under the usual multivariate normal assumptions).

The multilevel modeling approach described above allows us to focus on associations or “self-other correspondence” between within-person changes in self-concepts and within-person changes in external evaluations. In other words, because the across-time mean-level scores represent all of the between-person variation, the time-varying predictor variables are left to explain only within-person variation (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). We are then also able to examine how between-person differences moderate the self-other correspondence. Given the large number of parameters, particularly interactions, all final models were – after thorough examination – trimmed down to highlight the significant fixed and random effects.

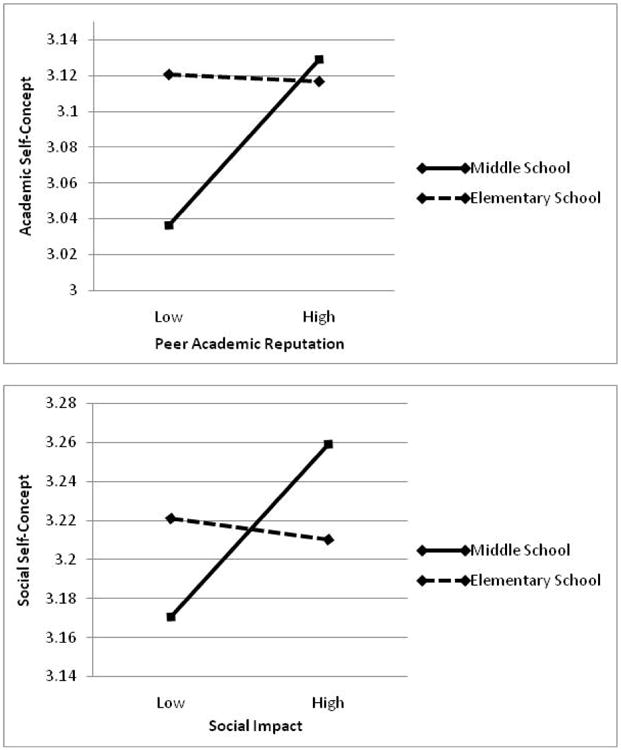

Parameter estimates and fit statistics for final, trimmed models for self-other correspondence in academic and social self-concept are given in Table 6. As hypothesized, results suggest that, on average, academic self-concept covaried significantly as a function of occasion-specific teacher ratings (γ40 =.08, p<.001). Also consistent with hypotheses, covariation between academic self-concept and occasion-specific PAR was significantly moderated by school-level (γ60 =.06, p<.05), such that there is a noteworthy positive correspondence between PAR and academic self-concept during middle school, while no covariation is evident during elementary school (see top of Figure 4). In addition, the correspondence between PAR and academic self-concept was weakly but significantly moderated by overall teacher-rated academic skills (γ51= .07, p<.01) and attention (γ52= -.05, p<.05). The former interaction suggests that highly academically skilled (but not lower skilled youth) experience a “boost” in academic self-concept at occasions when they have a high PAR. The latter interaction suggests that covariation between academic self-concept and PAR is strongest among youth with attention problems. In sum, self-peer correspondence emerges during middle school, and is more prominent for some youth than others, while self-teacher correspondence is a relatively consistent phenomenon.

Table 6. Multilevel Models Depicting Self-Concept Development in 3rd through 7th Grade and Self-Other Correspondence.

| Academic Self-Concept | Social Self-Concept | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Parameter | Estimate | SE | Parameter | Estimate | SE |

| Fixed effects estimates | Fixed effects estimates | ||||

| Intercept, γ00 | 3.12* | .03 | Intercept, γ00 | 3.22* | .02 |

| Grade in School, γ10 | .04* | .02 | Grade in School, γ10 | .06* | .01 |

| Middle School, γ20 | -.04 | .03 | Middle School, γ20 | <.01 | .02 |

| (Grade in School)(Middle School), γ30 | -.08* | .03 | |||

| Academic Skills, γ40 | .08* | .02 | Social Engagement, γ30 | .01 | .02 |

| Peer Academic Reputation (PAR), γ50 | <.01 | .02 | Social Preference, γ40 | .05* | .01 |

| Social Impact, γ50 | <.01 | .02 | |||

| (PAR)(Middle School), γ60 | .06* | .03 | (Social Impact)(Middle School), γ60 | .04* | .02 |

| iMean Academic skills, γ01 | .16* | .03 | iMean Social Engagement, γ01 | .09* | .04 |

| iMean Social Preference, γ02 | .05* | .02 | |||

| iMean Social Impact, γ03 | <.01 | .03 | |||

| iMean Self-worth, γ02 | .71* | .03 | iMean Self-worth, γ04 | .59* | .04 |

| iMean Attention, γ03 | .15* | .04 | iMean Attention, γ05 | -.10* | .03 |

| iMean Teacher-Rated Aggression, γ04 | .08* | .04 | iMean Peer-Nominated Aggression, γ06 | .10* | .03 |

| iMean Victimization, γ07 | -.22* | .05 | |||

| iMean Loneliness, γ08 | -.21* | .03 | |||

| (iMean Academic skills)(iMean Attention), γ05 | .05* | .03 | (iMean Social Preference)(iMean Self-worth), γ09 | -.04* | .02 |

| (iMean Social Preference)(iMean Victimization), γ0,10 | -.10* | .02 | |||

| (iMean Social Impact)(iMean Peer-Nominated Aggression), γ0,11 | -.05* | .02 | |||

| (iMean Social impact)(iMean Victimization), γ0,12 | -.11* | .03 | |||

| (PAR)(iMean Academic skills), γ51 | .07* | .03 | (Social engagement)(iMean Self-worth), γ31 | .07* | .03 |

| (PAR)(iMean Attention), γ52 | -.05* | .02 | (Social impact)(iMean Social preference), γ41 | -.03* | .01 |

| (Social impact)(iMean Victimization), γ42 | -.04* | .02 | |||

| Random effects estimates | Random effects estimates | ||||

|

| |||||

| Variance intercept, σ2u0 | .09* | .01 | Variance intercept, σ2u0 | .10* | .02 |

| Variance grade in school, σ2u1 | .04* | .01 | Variance grade in school, σ2u1 | .02* | <.01 |

| Variance (grade)(middle school), σ2u3 | .08* | .03 | Variance middle school, σ2u2 | .08* | .04 |

| Variance social preference, σ2u3 | <.01* | <.01 | |||

| Covariance intercept, grade in school, σu0u1 | .04* | .01 | Covariance intercept, grade in school,σu0u1 | <.01 | .01 |

| Covariance intercept, (grade)(middle school), σu0u3 | -.05* | .02 | Covariance intercept, middle school, σu0u2 | -.05 | .03 |

| Covariance grade, (grade)(middle school), σu1u3 | -.05* | .01 | Covariance intercept, social preference, σu0u3 | -.02* | .01 |

| Covariance grade, middle school, σu1u2 | <.01 | .01 | |||

| Covariance grade, social preference, σu1u3 | <.01 | <.01 | |||

| Covariance middle school, social preference, σu2u3 | .02* | .01 | |||

Note6: Bolded values were used to highlight for the reader the terms of greatest relevance to the research questions;

= p<.05

Figure 4.

Academic self-concept (top) and social self-concept (bottom) as a function of peer nomination-based scores (PAR above, social impact below). Both graphs demonstrate significantly stronger within-person covariation between peer nomination scores and self-concept during middle school (with little to no covariation evident in elementary school). The findings represented by these graphs are consistent with the idea that features of the middle school environment may heighten youths' awareness of and sensitivity to how they “measure up” to their peers and how their peers perceive them.

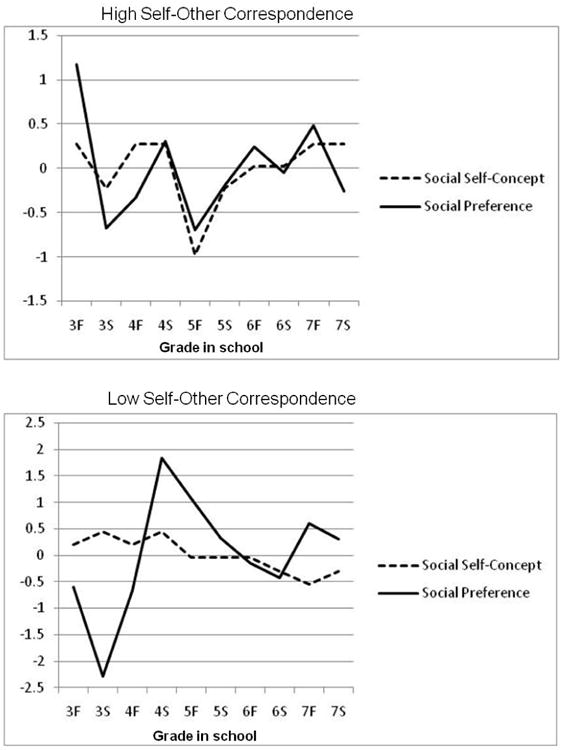

Similarly, as hypothesized, social self-concept significantly covaried with occasion-specific social preference (γ40 = .05, p<.001); and among youth high in self-worth, social self-concept covaried with occasion-specific social engagement (γ31=.08, p<.05). Also consistent with hypotheses, occasion-specific social impact positively related to social self-concept only during middle school (γ60 = .04, p<.05) (see bottom of Figure 4). An interaction between occasion-specific social impact and overall social preference (γ41 = -.03, p<.01) suggests that youth who tend to be low on social preference experience a “boost” in self-concept on occasions when they are also high on social impact, but this relation is reversed among youth high in social self-preference. Lastly, the difference in social self-concept between victimized and non-victimized youth appears to be greater on occasions when youth are high in social impact than when they are low in social impact (γ42 = -.04, p<.05). A significant random effect for occasion-specific social preference (u3i =.01, p<.05) suggests that there remain unaccounted for between-person differences in the covariation between social self-concept and social preference. A visual, conceptual example of how significant between-person differences manifest in the data is shown in Figure 3. The individual in the top panel is characterized by high self-other correspondence (i.e., covariation) and the individual in the bottom panel is characterized by low self-other correspondence. Overall, results of these final models suggest that self-concepts are more likely to “accurately reflect” external evaluations among well-adjusted youth.

Figure 3.

Representation of significant between-person differences in covariation between social self-concept and peer-nominated social preference across fall of 3rd grade through spring of 7th grade. One example of a child whose social self-concept strongly covaries with his or her social preference score over time (top), and one child whose social self-concept does not covary with his or her social preference score over time (bottom).

Discussion

Theories of self-concept development emphasize external feedback processes that likely fluctuate across time and contexts, yet existing empirical studies have more often focused on longer-term developmental trends. In the present study, we extend previous research by focusing attention on the within-person variability around youths' linear trajectories of academic and social self-concept development from 3rd through 7th grade – a concept that has received little attention in the literature thus far. We began by replicating developmental trajectories identified in previous studies: we found, on average, a modest but significant decline in academic self-concept during middle school. The average developmental growth trend for social self-concept, on the other hand, slowly increased across time with no apparent deflection at the middle school transition. We then made a new contribution to the literature by quantifying the amount of within-person variability around individuals' linear trajectories – self-concept lability. Results did not substantiate the expected increase in lability during middle school. Consistent with hypotheses, however, greater academic and social self-concept lability was associated with a general profile of poorer competence and several “proxies” of poorer mental health. We also demonstrate the unique predictive utility of self-concept lability scores: between-person differences in academic and social “success” at the end of 7th grade were negatively predicted by between-person differences in the respective domains of self-concept lability, even after accounting for mean self-concept. We additionally examine the within-person covariation over time between self-concept and others' perceptions of youths' competence – self-other correspondence. In line with expectations, self-peer correspondence across both competence domains was strongest during middle school, while self-teacher correspondence appears relatively consistent over time. Finally, moderation by several between-person differences suggests that self-other correspondence may be weaker among youth with poorer mental health.

Self-concept trajectories

We began with a replication of previous findings, using two-phase growth models to extract normative trends in self-concept. Consistent with the existing literature (e.g., Midgley et al., 1989; Wigfield et al., 1991), the present study indicates a shift from a relatively flat trend in academic self-concept across elementary school to a slight downward trend during middle school. As noted earlier, middle school can present a stark contrast to elementary school, with sudden shifts in teaching practices and educational climate that fit poorly with early adolescents' developmental needs, tending to undermine motivation, learning, and self-concept (e.g., Connell & Wellborn, 1991; Feldlaufer et al., 1988). Contrary to hypotheses, we found, on average, a modest increase in social self-concept across waves. Possible explanations include the fact that the items used to assess and track changes in social self-concept in the present study prompt children to consider how many friends they have and how easy it is to make friends (Harter, 1982). Perhaps youth are better able to make friends as the pool of potential friends grows to an entire grade cohort in middle school.

Self-concept lability

Beyond the long-term developmental trends noted above, both academic and social self-concept exhibited substantial within- and between-person variability across the transitional years from elementary to middle school. Bringing attention to this heterogeneity, we quantified the amount of within-person variability around youths' linear self-concept trajectories, and explored the developmental correlates and consequences of this lability. The present study is among the first to consider academic and social self-concept lability over a span of multiple years, and to examine its relation to actual competence in these domains.

Researchers exploring other domains of lability (e.g., self-esteem) have suggested that greater lability may represent a form of vulnerability, while stability indicates robustness (e.g., Greve & Enzmann, 2003; Roberts & Kassel, 1997). Our results correspond to the general notion of lability as a marker of risk: both academic and social self-concept lability were associated with a profile of poorer competence and overall adjustment. Results did not support the hypothesis that self-concept lability would be greater during middle school. As expected, however, greater academic self-concept lability related to lower overall academic self-concept, teacher ratings of academic skills, and peer academic reputation (PAR); and social self-concept lability was negatively related to youths' overall social self-concept, teacher ratings of social engagement, and peer nomination-based social preference. Greater lability in both domains of self-concept also consistently related to indicators of poorer mental health. Lastly, self-concept lability showed unique predictive utility: even after controlling for youths' average self-concept, between-person differences in self-concept lability negatively predicted between-person differences in academic and social competence at the end of 7th grade.

Taken together, the present findings consistently suggest that an unstable self-concept is maladaptive. One explanation for this result may be that self-concept lability reflects some type of psychological or environmental turmoil (e.g., Crocker & Knight, 2005). For instance, youth with depressive symptoms (e.g., low self-worth) may be prone to doubting and re-calibrating their self-concepts each time they are faced with new evaluative feedback; as such, recent successes or failures (e.g., a test grade) may tend to “override” previous demonstrations of ability. Similarly, certain behavioral problems such as aggression may elicit inconsistent feedback from peers (i.e., reinforcement by some but disliking from others), while youth with attention problems may struggle to maintain consistency in academic performance. These are just a few examples of ways in which poor mental health may generate a labile self-concept. More research will be needed to clarify the mechanisms that explain the relations observed in the present study, and to consider additional explanations for the observed lability. For instance, future research should consider features of youths' environment – such as an unstable home life or school climate, or changes over time in social and instrumental support from teachers and parents – that may account for some lability.

Alternatively, “causality” may go in the reverse direction: fluctuations in self-concept may contribute over time to poorer competence and adjustment. Our findings that self-concept instability across the elementary and middle school years predicted lower competence at the end of 7th grade are consistent with similar research (e.g., Tsai, 2008; Waschull & Kernis, 1996) in suggesting that self-concept lability may temporally precede poorer competence. A labile self-concept translates to a lack of coherent, realistic, or self-assured views of one's abilities and what challenges one can handle effectively. As such, a labile self-concept may lead to inconsistent effort and avoidance of the challenges needed to build academic or social skills; longer-term development of skills and problem-solving strategies are thus likely to suffer (Deci & Ryan, 1995; Kernis, 2003). More broadly, the present findings highlight the usefulness and importance of considering both level and lability as both cause and consequence in future examinations of self-concept and its relation to other constructs.

Self-other correspondence

Previous analyses of the present data suggested reciprocal relations between self-concept and external feedback: between-person differences in both teacher and peer feedback predicted later academic and social self-concept, and vice versa (Gest et al., 2005b; 2008). The present study strengthens this evidence, by establishing relations at the within-person level and across both academic and social domains of competence (e.g., Cillessen & Bellmore, 1999; Denissen, Zarrett, & Eccles, 2007). On average, youth reported an academic self-concept above or below their own average at waves when teachers' ratings of their academic skills were also above or below their own average. Similarly, semester-to-semester changes in social self-concept tracked occasion-specific levels of social preference. The present analyses do not allow us to determine the causal directionality of the relations between self-concepts and external feedback, but past research suggests that the self-other correspondence observed in the present study is likely bi-directional. Self-concept is found to be an important determinant of youths' effort and achievement in a particular domain and how others will perceive them (e.g., Guay et al., 2003; Eccles et al., 1983). Conversely, past achievement and feedback experiences are believed to form the basis of youths' self-concepts. A common theme across theories of self-concept has been the idea of a “looking glass self”: individuals see themselves the way they believe others see them (Cooley, 1922; Cairns & Cairns, 1988; James, 1890). This process may be particular relevant during early adolescence, which marks a developmental peak in youths' interest in and anxiety about what peers think of them, and development of the cognitive capacity to accurately assess and incorporate external evaluations into self-views (Bukowski et al., 2000; Dweck, 2002).

It is likely that third variables unavailable to us in the present study would also help to explain the within-person variability and covariation we have extracted. For instance, pubertal timing is known to influence self-perceptions and a variety of behavioral outcomes (e.g., Weisner & Ittel, 2002) and thus may explain observed shifts in both self-concept and performance. Similarly, environmental factors are likely to influence levels of self-concept, achievement, and their covariation. The quality of relationships with peers, parents, or teachers (e.g., parents' disciplinary tendencies), teaching practices (e.g., opportunities for active learning, harsh grading), and school climate (e.g., students' feelings of safety and support in the school) are just a few examples of important factors likely to affect youths' social and academic development. Further work, such as experimental studies, will be necessary to obtain a more honed picture of when and how self-other correspondence processes unfold over time.

Consistent with the idea that features of the environment can impact the degree of self-other correspondence, two forms of self-peer correspondence were only evident during middle school: covariation between academic self-concept and PAR, and covariation between social self-concept and social impact. Entry to middle school introduces numerous changes that may heighten youths' attention to social comparisons and sensitivity to external feedback from peers, such as normative grading systems and increased emphasis on performance goals rather than mastery. Thus, youth are especially attuned to relative skill levels and assessing how their peers view them during middle school (e.g., Dweck, 2002). These processes likely converge to produce stronger self-peer correspondence during middle school, as seen in the present study.

Though there are numerous reasons to expect correspondence between self-concepts and external feedback, both historical and recent theories also highlight between-person differences in this process, identifying a variety of biased “lenses” through which youth may perceive, interpret, and internalize evaluative information. For instance, youth may place particularly high value on particular evaluations, or tend to view evaluative information through a consistently negative lens (e.g., Crocker & Knight, 2005; John & Robins, 1994). The present study can be interpreted as further substantiating these ideas, providing evidence for several between-person moderators of self-other correspondence. For instance, an interaction of occasion-specific social impact with overall social preference suggests that strong peer reactions – even when negative – are more beneficial to social self-concept than neglect (i.e., a lack of peer attention). In contrast, high social impact among well-liked youth appears to be “harmful”; this is consistent with some evidence suggesting that being highly prominent or “popular” in one's social network tends to elicit strong reactions from peers, both positive and negative (e.g., de Bruyn & Cillessen, 2010). Moreover, the present findings suggest an important role of mental health. Within-person relations between academic self-concept and PAR were stronger among youth with attention problems, but these youth tended, on average, to have less “accurate” self-perceptions of their academic skills (as rated by teachers). The within-person correspondence between teacher ratings of social engagement and social self-concept was weaker among youth with low self-worth, and occasion-specific social impact seemed to have little effect on the low overall social self-concepts of victimized youth. Taken together, these findings suggest that poorly adjusted youth tend to have less “accurate” self-views, which in some cases may be negatively biased.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

This study has several strengths that contribute to the literature on early adolescent self-concept development. The longitudinal design with high participation rates and low attrition, allowed us to examine developmental processes; and the relatively large number of assessments (up to 10 occasions) allowed us to go beyond the usual between-person investigations. The present study thus strengthens results from previous research, demonstrating these relations within-person with stricter tests that control for between-person differences. Moreover, this study is among the first to apply within-person variability methods (Ram & Gerstorf, 2009) to the study of youths' self-concept and to examine domain-specific self-concept lability in relation to corresponding domains of competence. Within-person variability methods are typically applied to data collected at much faster time scales (i.e., multiple assessments obtained over minutes or days). Here, we extend previous work by applying this method to a period of months and years, reaching conclusions similar to those of other studies: greater lability is associated with poorer adjustment. These findings are unique in drawing attention to individual differences in youths' characteristic amount of lability around their longer-term self-concept trajectories, and highlighting self-concept lability as an important phenomenon worth continued consideration.

A strength of our homogeneous sample is the elimination of potential unobserved moderators that may blur the phenomena of interest. However, with a sample of students from only one rural, racially homogeneous school district, we cannot generalize our findings to the larger population. Future investigations should attempt to replicate our findings across more representative samples, both within and outside of rural communities, to learn more about how other individual, family, school, and community-level factors impact the self-concept development and lability processes explored here. For instance, youth attending schools in larger or more racially heterogeneous communities are likely encounter different factors (such as racial stereotypes; e.g., Steele & Aronson, 1995) that shape their self-concept.

Some aspects of the initial design of the study limited our ability to fully capture within-person variability and potential correlates. For instance, the procedures used to obtain “peer evaluations of competence” required a shift in measurement from elementary classroom-level nominations to middle school grade-level nominations. Although this shift in measurement conceptually matches with the actual shift in size of youths' “peer network” as they move into middle school, it raises concerns faced by many measures in developmental research as to whether the meaning of the measure remains consistent across this transition. Further, self-concept development is known to vary substantially across domains (e.g., Jacobs et al., 2002), including variations across specific school subjects (e.g., math, reading), but only the broad measures were available here. Future work should examine if and how more fine-grained domains of self-concept lability are related, and/or are coupled to other factors. It is likely that occasion-specific changes in self-concept and the tendency for a youth's self-concept to be particularly labile could be more thoroughly explained by numerous individual and environmental variables to which we did not have access in the present dataset. For instance, other individual differences (e.g., personality or more direct indices of mental health), relatively temporary developmental phases (e.g., level of a youth's physical or psychological maturation), and multiple features of the environment in which a child's self-views are developing (e.g., the stability of youths' home lives or school climate, consistency of support from teachers and parents, or significant life events such as parents' divorce) would undoubtedly help to account for some of the within- and between-person variability observed in this study.

Having established the need for research to consider both long-term developmental changes and shorter-term “ups and downs” in self-concept, an important next step for future research will be to dig deeper into the within- and between-person processes that account for self-concept lability. Self-concept lability may be largely a product of youths' environments (e.g., inconsistent teaching practices), it may represent an enduring characteristic of an individual (e.g., sensitivity to external events), or it may reflect a more temporary phase of development (e.g., late pubertal timing). To this end, a person-centered approach may be a useful future step, allowing us to identify “profiles” of youth who are more labile or more stable. For instance, a latent profile analysis could help us to pin down the risk factors associated with self-concept lability. Perhaps labile youth are consistently characterized by low self-esteem, internalizing symptoms (e.g., depression, anxiety), or behavior problems; or perhaps external stressors such as a chaotic home life or low socioeconomic status are the primary variables that distinguish labile youth from more stable youth. Our use of mental health “proxy” variables was a valuable first step in this direction, but more direct indices of mental health and environmental risk factors as well as focused person-oriented analyses will be needed to gain a clear picture of who these more labile youth are.