Abstract

Objective

Effects of progressive substitution of dietary n-3 fatty acids (FA) for saturated FA (SAT) on modulating risk factors for atherosclerosis have not been fully defined. Our previous reports demonstrate that SAT increased, but n-3 FA decreased, arterial lipoprotein lipase (LpL) levels and arterial LDL-cholesterol deposition early in atherogenesis. We now questioned whether incremental increases in dietary n-3 FA can counteract SAT-induced pro-atherogenic effects in atherosclerosis-prone LDL-receptor knockout (LDLR−/−) mice and have identified contributing mechanisms.

Methods and results

Mice were fed chow or high-fat diets enriched in SAT, n-3, or a combination of both SAT and n-3 in ratios of 3:1 (S:n-3 3:1) or 1:1 (S:n-3 1:1). Each diet resulted in the expected changes in fatty acid composition in blood and aorta for each feeding group. SAT-fed mice became hyperlipidemic. By contrast, n-3 inclusion decreased plasma lipid levels, especially cholesterol. Arterial LpL and macrophage levels were increased over 2-fold in SAT-fed mice but these were decreased with incremental replacement with n-3 FA. n-3 FA partial inclusion markedly decreased expression of pro-inflammatory markers (CD68, IL-6, and VCAM-1) in aorta. SAT diets accelerated advanced atherosclerotic lesion development, whereas all n-3 FA-containing diets markedly slowed atherosclerotic progression.

Conclusion

Mechanisms whereby dietary n-3 FA may improve adverse cardiovascular effects of high-SAT, high-fat diets include improving plasma lipid profiles, increasing amounts of n-3 FA in plasma and the arterial wall. Even low levels of replacement of SAT by n-3 FA effectively reduce arterial lipid deposition by decreasing aortic LpL, macrophages and pro-inflammatory markers.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, LDLR−/−, lipoprotein lipase, inflammation, n-3 fatty acids

1. INTRODUCTION

Many studies, including our own, have shown that dietary fatty acids (FA) affect pathways related to atherogenesis 1–3. We have reported that dietary saturated FA (SAT) increased arterial lipoprotein lipase (LpL) levels, and that this was associated with increased arterial LDL deposition before the development of atherosclerotic lesions 1, 4, 5. By contrast, n-3 FA-rich diets decreased arterial wall LDL deposition and LpL levels 4, 5. n-3 FA in in vivo and in vitro model systems have been shown to decrease pro-inflammatory markers that can slow atherosclerosis 3–7. Still, much of our information about the mechanisms underlying the role of dietary FA in atherogenesis is derived from laboratory studies using high-fat diets enriched in SAT, n-6 polyunsaturated FA, or n-3 FA only. In the United States, dietary fat intake usually includes SAT but with very low levels of n-3 FA 8, 9. Replacement of SAT by n-6 polyunsaturated FA may decrease risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) in part by decreasing blood levels of total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides (TG) and inflammatory markers in humans 10. Replacing SAT with n-3 may decrease the risk for CVD even more than n-6 alone 11. Although controversy continues on the effects of n-3 supplementation on human CVD 12, 13, little is known about the effects of progressively increasing dietary intake of n-3 FA on modulating arterial lipid deposition and atherosclerosis.

The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis has been studied in a number of animal species, such as monkeys, baboons, pigs, rabbits, hamsters, rats and mice. There are differences between species with respect to the influences of dietary n-3 FA on atherosclerosis 14. C57BL/6 and insulin resistant mouse models that we have used to demonstrate the effects of dietary FA on regulating arterial LDL uptake and LpL levels have some limitations 4, 5. For example, they do not develop atherosclerosis even on high-fat diets. The use of genetic knockout has created the mouse strains, such as apoE knockout (apoE−/−) and LDL-receptor knockout (LDLR−/−) mice, with altered lipoprotein profiles and susceptibility to atherosclerosis. However, none of the current mouse models develops the extensive lesions comparable to human atherosclerosis and acute cardiovascular events 15. Compared to LDLR−/− mice, apoE−/− mice exhibit a higher inflammatory state 16, 17, develop complex atherosclerotic lesion spontaneously 15 and respond poorly to n-3 FA intervention 18. Thus, in the current studies, we evaluated the regulatory effects of dietary SAT being replaced with n-3 FA on the progression of atherosclerosis and arterial LpL levels and localization in a mouse model for diet-inducible atherosclerosis, LDLR−/− mice. LDLR−/− mice were fed custom-made diets varying only in lipid composition; a low-fat chow diet or high-fat, high-cholesterol diet enriched in either saturated fats, n-3 fats, or a combination of SAT and n-3 fats in ratios of 3:1 or 1:1 for 12 weeks. Our data demonstrate that increasing replacement of SAT by n-3 FA intake abrogated the adverse effects mediated by SAT. Underlying responsible mechanisms relate to a) improved mouse plasma lipid profiles and lowered total and LDL cholesterol levels; b) reduced aortic macrophage-associated LpL; and c) decreased aortic macrophage markers and pro-inflammatory markers. The net result was a progressive decrease of atherosclerosis in LDLR−/− mice with increasing n-3 intake especially when compared with the SAT diet alone.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Detailed methods are available as Supplemental materials.

2.1. Feeding protocols

Feeding studies were repeated twice and conducted over two different time periods (a total of 150 nine-week-old male LDLR−/− mice, The Jackson Laboratory). In each set of studies, 75 mice LDLR−/− mice were fed custom-made eucaloric diets (Harlan Teklad); a low-fat chow diet or high-fat, high-cholesterol diet enriched in either saturated fats (coconut oil), n-3 fats (menhaden oil), or a combination of SAT and n-3 fats in ratios of 3:1 (25% n-3) or 1:1 (50% n-3) for 12 weeks. The low-fat chow and high-fat diets contained 50 g fat and 0.2 g cholesterol, and 185 g fat and 2 g cholesterol per kg of diet, respectively. Supplemental Tables I and II list the detailed composition of macronutrients and measured fatty acid profile of each diet, respectively. Fasting mouse plasma was collected monthly and measured for levels of free FA (FFA) (NEFA C kit, Wako), TG, and total cholesterol (Chol) (Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer’s procedures as previously detailed 19. The results from the two feeding studies were very similar. All experimental procedures were approved by the Columbia University Institutional Animal Care Committee.

2.2. Fatty acid composition of mouse feed and aorta

Lipid extracts from mouse plasma, artery and mouse feed from each feeding group were analyzed for FA composition by gas-liquid chromatography (GLC) as previously described 20, 21. Results were normalized for weight percent of each FA.

2.3. Immunofluorescent studies

The localization of arterial LpL with aortic cells was examined by immunofluorescence (IFC) as described previously 5. Sections of proximal aorta and aortic root were co-incubated with primary goat anti-LpL, rat anti-EC (CD31) and rabbit anti-macrophage (CD68) antibodies for 24 h at 4 °C, followed by 1-h incubation of the mixture of corresponding fluorescent secondary. Fluorescence in the arterial wall was analyzed using a laser scanning confocal microscope (LSM-510 META). An argon laser (488 nm) and two helium-neon lasers (543 nm and 633 nm) were utilized for the excitation of Alexa 488, 546, and 647, respectively. Fluorescence of LpL and macrophages was quantitated as previously detailed 5, 22.

2.4. Laser capture microdissection (LCM)

Macrophages from the aortic root were extracted by LCM for LpL expression as previously described 23. Slides stained for macrophages were used to navigate and select macrophage-containing areas on the adjacent slides. Sequential slides with corresponding area of macrophages were stained with Harris modified hematoxylin and eosin and were used for microdissection using PALM MicroBeam IV (P.A.L.M. Microlaser Technologies). RNA extraction, amplification and analyses from collected aortic macrophages were performed following the manufacturer’s instructions (MicroRNA Isolation kit, Stratagene, and MessageAmp II aRNA Amplification Kit, Ambion).

2.5. Quantitative Real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from mouse proximal aorta with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Single strand cDNA was synthesized using iScript reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Quantitative real-time PCR was carried out on an iCycler (Bio-Rad) using SYBR PCR kit (Applied Biosystems). Results were analyzed by comparing the threshold crossing (Ct) of each sample after normalization to control genes (ΔCt) using the formula 2−ΔCt. Supplemental Table III lists the primer sequences.

2.6. Morphometric analyses of atherosclerosis

Atherosclerotic lesion development was measured at the aortic root. Sections of aortic valve were stained with Harris modified hematoxylin and Oil-Red-O (Fisher Scientific) 24. Aortic lesion formation in each animal was measured as total lesion area (μm2) per section from the point at which all three aortic valve leaflets first appeared according to the method by Paigen et al.24.

2.7. Statistical analyses

Student’s t-tests of group means were used to compare endpoints, and ANOVA was used to evaluate potential interactions between diets. The results from two sets of feeding studies were combined by normalizing to the mean of each chow-fed group and are expressed as the mean fold change±SE. Statistical significance was determined at the level of p<0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Body weight and plasma lipid levels

LDLR−/− mice were fed a regular rodent chow diet or diets enriched in only SAT, n-3 fats, or a combination of both SAT and n-3 fats in ratios of 3:1 (S:n-3 3:1) or 1:1 (S:n-3 1:1) for 12 weeks. All groups gained weight during the feeding period (supplemental Figure I): SAT and S:n-3 3:1 diet-fed mice had the highest increases, whereas chow-fed mice had the lowest increases in body weight (p<0.05). The average daily intake among each feeding group was similar (data not shown).

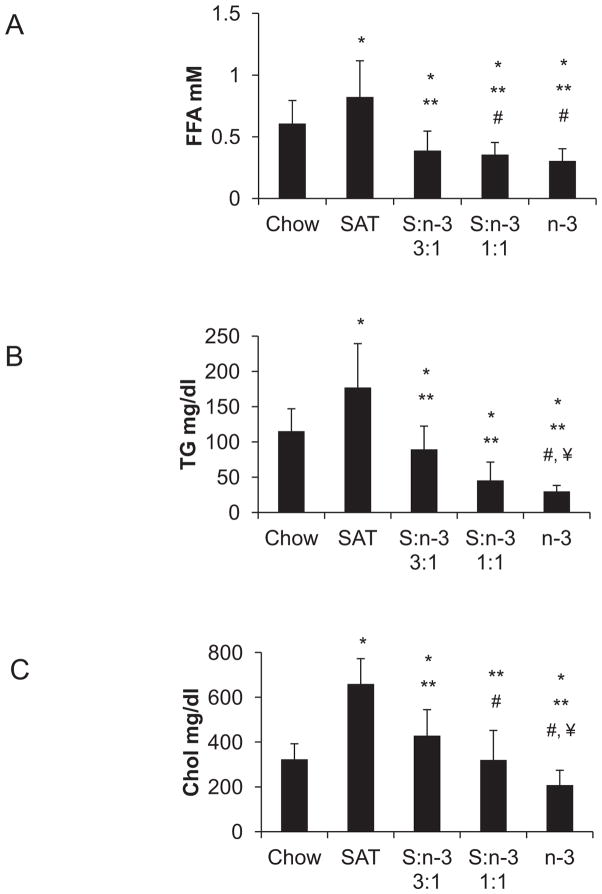

Plasma lipid profiles were determined in LDLR−/− mice at the end of 12-week feeding period. SAT diets led to a ~ 40% increase in plasma FFA and a > 50% increase in TG levels (p<0.01, Figure 1, A–B) when compared with the chow diets. Inclusion of n-3 FA in S:n-3 3:1 and 1:1 diets substantially decreased FFA and TG even when compared with chow-fed mice (Figure 1, A–B). LDLR−/− mice (on chow diet) had elevated plasma cholesterol levels when compared with those previously described in C57BL/6 mice 4, SAT-only feeding resulted in marked hypercholesterolemia in LDLR−/− mice. Mice fed the n-3-containing S:n-3 3:1 and 1:1 diets had much lower cholesterol levels than SAT-only fed-mice, comparable with chow-fed mice, while n-3-only diet-fed mice had the lowest plasma cholesterol levels (p<0.01, Figure 1C). Note that the cholesterol content in each of these high-fat diets is considerable (0.2%, w/w) when compared with the chow diet (0.02%, w/w). Therefore, we suggest that n-3 FA are effective in reducing plasma lipid levels, including cholesterol levels, in LDLR−/− mice, even when on high-cholesterol, high-fat diets.

Figure 1.

Effects of FA on plasma lipid profiles in LDLR−/− mice. Blood samples were determined for plasma free fatty acids (A, FFA), triglycerides (B, TG), and total cholesterol (C, Chol) at the end of 12-weeks of feeding with specific diets (n=20 from two separate but identical feeding studies, mean±SE). *, p<0.01, vs. chow; **, p<0.05, vs. SAT; #, vs. S:n-3 3:1; ¥ vs. S:n-3 1:1.

3.2. Effects of dietary FA on plasma and aortic fatty acid composition

Effects of dietary FA intake on fatty acid composition were evaluated in circulating plasma and in aorta using GLC in LDLR−/− mice after each feeding period. As shown in Table 1, n-6 FA-rich chow diet, which contained > 50% of its FA as linoleic acid (LA, 18:2) (supplemental Table II), proportionally raised LA levels in mouse plasma. Despite the fact that all high-fat diets contained ~8 % of LA, LA was decreased in both plasma and aorta in mice fed S:n-3 1:1 and n-3-only diets (Table 1). Although n-6 arachidonic acid (AA, 20:4) was not detected in the SAT diets, a significant amount of AA was present in both plasma and aorta in SAT-fed mice. SAT also increased saturated lauric acid (12:0) and myristic acid (14:0) in plasma and aorta (p<0.05). Mouse plasma and aortic α-linolenic acid (ALA 18:3) content was not affected by feeding the diets with different levels of ALA. On the other hand, progressive addition of n-3 fats in diets markedly and progressively increased arterial n-3 eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 20:5) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6) in mouse plasma (p<0.05) and artery (p<0.05), whereas saturated lauric and myristic acid were progressively decreased. DHA in the aorta increased much more than EPA in n-3-fed mice, although n-3 diets contained higher amounts of EPA when compared to DHA. Overall, each diet resulted in the expected changes in fatty acid composition in blood and aorta for each feeding group (supplemental Table II).

Table 1.

Plasma and aortic fatty acid composition in LDLR−/− mice (weight % of total fatty acids).

| Chow | SAT | S:n-3 3:1 | S:n-3 1:1 | n-3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plasma | aorta | plasma | aorta | plasma | aorta | plasma | aorta | plasma | aorta | |

| 12:0 | 0.00±0.00 | 0.00±1.23a | 1.21±0.19 | 7.65±1.23b | 0.23±0.16 | 6.06±0.91bc | 0.00±0.00 | 5.08±0.00c | 0.00±0.00 | 0.00±0.00a |

| 14:0 | 0.00±0.00 | 2.13±0.19a | 2.68±0.16 | 9.09±0.63b | 0.89±0.f35 | 8.30±0.26b | 1.31±0.18 | 8.01±0.53b | 0.42±0.26 | 4.06±1.08c |

| 16:0 | 20.44±0.29 | 26.71±0.97a | 20.87±1.17 | 18.40±0.97b | 21.95±1.47 | 19.99±2.53b | 21.87±2.04 | 22.00±1.49ab | 23.75±0.58 | 20.45±2.76b |

| 16:1 | 3.19±0.24 | 8.41±0.67 | 8.19±0.47* | 4.86±1.33 b | 7.95±0.93* | 4.44±1.43b | 5.80±0.50 | 4.48±0.69b | 5.01±0.17 | 4.56±1.36b |

| 18:0 | 7.93±0.07 | 6.37±0.36ac | 7.89±0.21 | 4.03±0.79b | 9.65±0.58 | 5.51±0.58ab | 11.20±0.84 | 7.20±0.50c | 9.81±0.28 | 9.73±0.07d |

| 18:1 (n-9) | 12.78±0.37 | 38.50±2.14a | 23.75±0.4* | 30.93±2.31b | 18.72±1.54*¥ | 27.35±0.37bc | 13.90±0.35#¥ | 24.25±1.04c | 8.70±0.44*# | 18.19±1.86d |

| 18:2 (n-6) | 36.44±0.58 | 13.28±1.18ac | 20.74.±0.73* | 19.93±1.66b | 20.95±0.63*¥ | 19.96±2.43b | 15.83±0.82*#¥ | 17.12±1.04ab | 11.71±0.38*# | 11.57±1.17c |

| 18:3 (n-3) | 0.93±0.03 | 0.71±0.09 | 0.46±0.02 | 0.87±0.60 | 0.00±0.00 | 1.09±0.55 | 0.26±0.26 | 1.69±0.18 | 0.00±0.00 | 1.60±0.92 |

| 20:3 (n-3) | 1.12±0.07 | 0.28±0.25a | 1.28±0.35 | 0.52±0.10ab | 0.28±0.17 | 0.39±00.06a | 0.10±0.15 | 0.40±0.01a | 0.42±0.27 | 0.89±0.06b |

| 20:4 (n-6) | 9.13±0.19 | 2.49±0.77ad | 10.49±0.72 | 2.47±0.68ad | 4.57±1.16*#¥ | 0.97±0.15bc | 6.96±0.67#¥ | 1.03±0.04c | 10.92±0.31 | 3.14±0.05d |

| 20:5 (n-3) | 2.73±0.08 | 0.00±0.00a | 1.14±1.14 | 0.00±0.00a | 9.12±2.55#¥ | 0.96±0.08ab | 14.38±1.41*# | 1.27±0.22b | 16.84±0.31*# | 3.51±0.74c |

| 22:4 (n-6) | 0.00±0.00 | 0.00±0.00 | 0.00±0.00 | 0.33±0.08 | 0.00±0.00 | 0.20±0.07 | 0.00±0.00 | 0.09±0.08 | 0.00±0.00 | 0.34±0.58 |

| 22:5 (n-3) | 0.00±0.00 | 0.12±0.12a | 0.00±0.00 | 0.14±0.04ab | 0.22±0.22 | 1.11±0.25ab | 0.00±0.00# | 1.51±0.31b | 0.37±0.23 | 3.91±0.65c |

| 22:6 (n-3) | 5.42±0.20 | 0.99±0.33a | 1.31±0.12* | 0.77±0.33a | 5.50±1.51#¥ | 3.68±0.70ab | 8.35±0.71#¥ | 5.87±0.48b | 12.35±0.40*# | 18.05±2.25c |

At the end of feeding period, mouse plasma (n=5) and aorta (n=3) from each group were analyzed for fatty acid composition using GLC as described in Methods. Results are expressed as mean weight percent ±SE. Different superscripts are significantly different, p<0.05.

vs. chow;

vs. SAT;

vs. n-3, p<0.05.

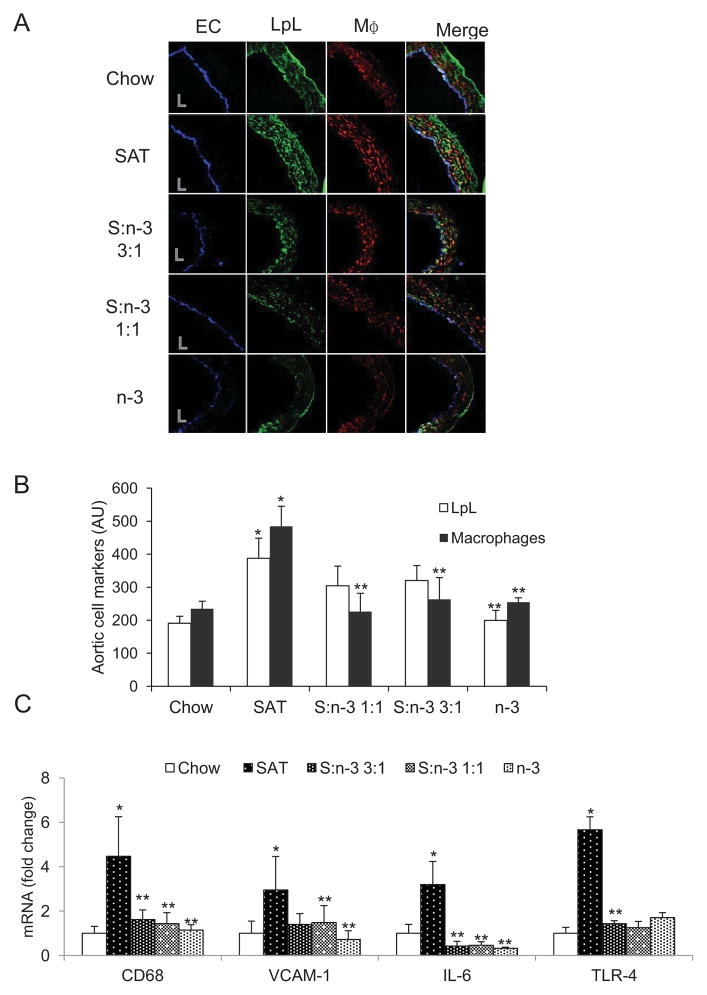

3.3. Aortic LpL, macrophages and inflammatory mediators in LDLR−/− mice

As described in our previous studies 4, 5, SAT diets increased, but n-3 diets decreased, LpL in the proximal aorta in wild-type C57BL/6 mice and insulin resistant mice; increases in arterial LpL levels were linked to aortic macrophage number 4, 5. In the current studies, while using endothelial cell (EC) staining for orientation of aorta sections and as a positive control, immunofluorescent images showed that SAT diets increased, whereas n-3 decreased, arterial LpL and macrophages in the proximal aorta (Figure 2, A–B, p<0.05). Although LpL increased, non-significantly, in the proximal aorta of mice fed the high-fat, high-cholesterol S:n-3 3:1 and 1:1 diets when compared with chow-fed mice, all high-fat diets containing n-3 FA markedly reduced aortic macrophages when compared with the SAT diet, and in fact were comparable with the low-fat, low-cholesterol chow diet (Figure 2B). Quantitative immunofluorescence of EC did not change with changes in dietary FA content (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Effects of diet on LpL, macrophages and inflammatory markers in proximal aorta in LDLR−/− mice. (A). Representative images of proximal artery sections stained for endothelial cells (EC), LpL and macrophages (MΦ) in LDLR−/− mice that were fed the specific diets for 12 weeks. “L” indicates lumen. (B). Immunofluorescence of aortic LpL (open bars) and macrophages (filled bars) quantitated for each group. Mean±SE, n=3–4. (C) mRNA analyses of arterial pro-inflammatory markers. Proximal aorta homogenates of LDLR−/− mice (n=5) were analyzed for mRNA of CD68, VCAM-1, IL-6 and TLR-4 in each group. Data are expressed as mean±SE. *, SAT vs. chow; **, vs. SAT, p<0.05.

In aorta, we compared how different SAT and n-3 FA-rich diets regulate gene expression of selected markers that are involved in the inflammatory responses. SAT diets also significantly increased macrophage CD68 and pro-inflammatory interleukin-6 (IL-6), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR-4) several fold higher than in the chow-fed group (Figure 2C, p<0.05). In contrast to SAT, diets containing n-3 FA, even the S:n-3 3:1 diets in which the n-3 FA diet comprised as little as 25% fish oil of the total fat content, led to substantially decreased gene expression of those pro-inflammatory markers (p<0.05). Expression of TLR-4 downstream signaling factor (NF-κB) and its target gene (TNF-α) was also decreased by n-3 diets (data not shown). A tendency for mild increases in mRNA gene expression of anti-inflammatory IL-10 was found in the n-3 fed group (data not shown). Note that decreased expression of pro-inflammatory markers in aorta after feeding with n-3-containing diets was consistent with decreases in plasma pro-inflammatory molecules: all high-fat, n-3-containing diets reduced plasma monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) and IL-6 levels in LDLR−/− mice by more than 30% and 50%, respectively, when compared with chow- or SAT-fed mice (data not shown).

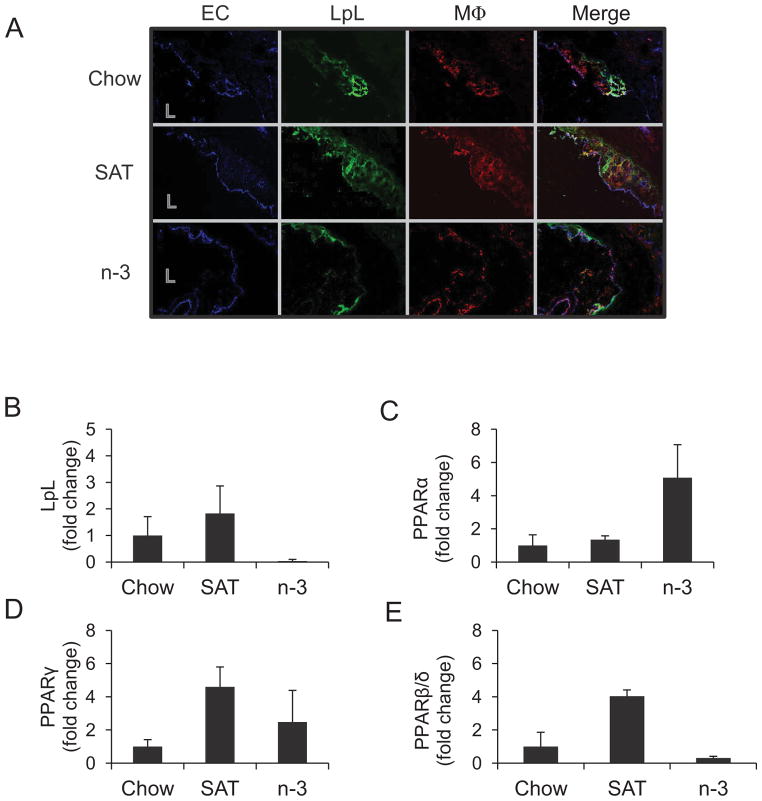

Next, we examined LpL and macrophages in atherosclerotic lesions at the aortic origin (Figure 3), where the atherosclerotic lesions usually initially develop in mouse models. Most LpL that was present in atherosclerotic lesions colocalized with macrophages among each feeding group (Figure 3A). Fluorescent staining of LpL and macrophages increased with an increase in lesion area and severity of atherosclerosis. SAT-fed mice with the extensive lesions had the highest numbers of macrophages as well as higher levels of LpL in the aortic root compared with mice fed the n-3 diets that showed lower levels of fluorescence for LpL and macrophages.

Figure 3.

Effects of diet on LpL and macrophage localization and LpL/PPAR mRNA at the aortic origin in LDLR−/− mice. (A) Images shown are the colocalization of aortic EC, LpL, and macrophages (MΦ) in LDLR−/− mice fed a chow, SAT, or n-3 diet for 12 weeks. L=lumen. Aortic macrophages were collected by LCM and pooled (n=3–5)for measuring mRNA expression of LpL (B), PPARα (C), γ (D), and β/δ (E) with triplicate runs (mean±SE) in each group as described in Methods.

Macrophages from the atherosclerotic lesions at aortic root in LDLR−/− mice were extracted by laser capture microdissection (LCM) and then were pooled for gene amplification for each group. Gene expression analyses show that LpL levels were indeed increased in aortic macrophages from SAT-fed mice, while n-3 markedly decreased LpL mRNA (Figure 3B). Binding of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR) to the peroxisome proliferator response element (PPRE) consensus sequence on LpL promoter is shown to induce LpL gene expression. We sought to examine the expression of three isoforms of PPARs, PPARα, PPARγ and PPARβ/δ, in isolated macrophages by LCM (Figure 3, C–E). The data show that expression of PPARα and PPARγ tended to increase in SAT- and n-3-fed compared to chow-fed mice, whereas expression of PPARβ/δ increased by SAT but decreased by n-3 diets (Figure 3D–E). Changes in expression of PPARβ/δ mediated by dietary FA may link to macrophage-LpL expression in macrophages.

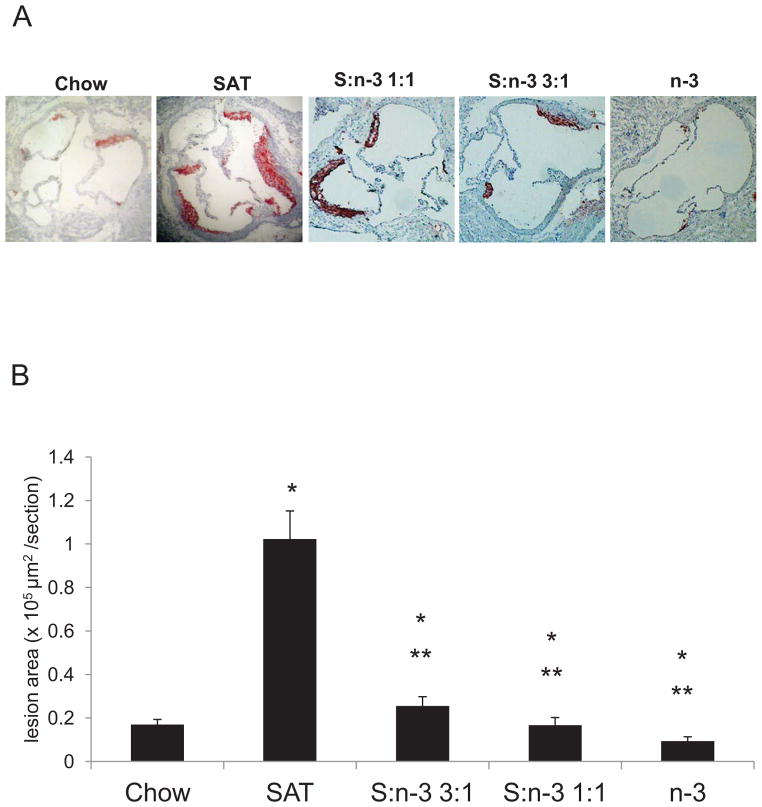

3.4. Dietary n-3 FA reduce atherosclerosis in SAT-fed mice

We examined the effects of incremental increases in n-3 FA on the progression of atherosclerotic lesions in LDLR−/− mice after 12 weeks of feeding (Figure 4). In chow-fed LDLR−/− mice, modest fatty streaks developed in the sections of the aortic valve (Figure 4A). Advanced complex plaques with substantial lipid deposition were observed in all SAT-fed mice as indicated by staining of hematoxylin and Oil-Red-O. Diets that contained 25% n-3 fats (S:n-3 3:1) or 50% (S:n-3 1:1) on a background of high SAT effectively inhibited atherosclerotic lesion development in LDLR−/− mice. Mice fed the high-fat, high-cholesterol S:n-3 3:1 diet had reduced lesion development comparable to low-fat, low-cholesterol chow-fed mice. There were no or only small fatty streaks found in n-3-only-fed mice (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Atherosclerotic lesion development in LDLR−/− mice after feeding with different diets. At the end of each feeding period, aorta of LDLR−/− mice were collected as described in Methods. Representative images of the aortic origin stained with hematoxylin and Oil-Red-O (A). (B) Quantitation of atherosclerosis in the aortic origin in LDLR−/− mice (n=8–10 for each group). The results are expressed as mean lesion area (μm2) ±SE. *, vs. chow; **, S:n-3 3:1/1:1/n-3 vs. SAT, p<0.01.

The extent of the atherosclerosis was quantitated for each feeding group (Figure 4B). Mean lesion area mass was 16.88±0.10 mm2 (~ 5 % per total aortic area) in chow-fed LDLR−/− mice. Atherosclerotic lesion size was significantly increased in SAT-fed LDLR−/− mice (p<0.01). LDLR−/− mice fed the n-3-only diets had the lowest levels of atherosclerotic lesion formation (p<0.01, Figure 4B). Mice fed the S:n-3 3:1 or 1:1 diet had much less of an increase in lesion size, comparable with chow-fed mice.

4. DISCUSSION

Dietary FA play an important role in influencing pathways of atherogenesis at an early stage, where arterial LDL and LDL-cholesterol deposition contributes to the initiation of atherosclerotic lesion formation 4, 5. Effects of progressive substitution of dietary n-3 FA for SAT on modulating risk factors for atherosclerosis are not fully understood. In the studies described here, on a background of high-SAT and high-cholesterol intakes, we explored the effects of incremental increases of dietary n-3 FA on atherogenic markers and on the extent and severity of atherosclerosis in LDLR−/− mice. As expected, when LDLR−/− mice were fed the high-SAT diets, their plasma FFA and TG levels were markedly elevated. They were also hypercholesterolemic and developed advanced atherosclerosis. Progressive replacement of SAT with n-3 markedly inhibited pro-atherogenic contributors to atherosclerosis including elevated plasma lipids, plasma and aortic pro-inflammatory markers, aortic LpL and macrophages, resulting in decreased atherosclerotic lesion development.

Our data indicate that high levels of saturated FA alter recruitment of different cell populations to the arterial wall, particularly accumulation of macrophages that secrete LpL, and thus favor the development of atherosclerosis. Increased arterial LpL in SAT-fed LDLR−/− mice might be associated with increasing arterial lesions by mediating uptake, binding, and retention of LDL in aorta 1, a key step in initiating atherosclerosis. Increased arterial LpL might also lead to increased local TG hydrolysis to supply extra energy for aortic cells (i.e., metabolically active macrophages in the arterial wall) resulting in accelerated atherosclerotic lesion formation. Tissue-specific expression of LpL contributes to differences in the role of LpL in mediating atherosclerosis. For example, systemic overexpression of LpL suppressed diet-induced atherosclerosis in LDLR−/− mice 25 and apoE−/− mice 26. By contrast,, heterozygous LpL deficiency diminished the retention of atherogenic lipoproteins in LDLR−/− 27. Also, macrophage overexpressing LpL into LDLR−/− mice markedly increased atherosclerosis 28. The latter two studies are in agreement with our findings that dietary n-3 FA intake reduces arterial LpL levels, which in turn leads to reduced atherosclerosis. We postulate that increased LpL in response to SAT was locally produced by arterial cells- macrophages and, possibly smooth muscle cells (SMC). However, in our previous studies, we did not find significant changes in SMC-LpL mediated by dietary FA in C57BL/6 mice by immunofluorescence; SMC accounted for only small amounts of arterial wall LpL protein (Chang, Deckelbaum, unpublished data). Note that in n-3-fed LDLR−/− mice, LpL mRNA was decreased in isolated aortic macrophages extracted by LCM (Figure 3). Therefore, we suggest that dietary FA influence arterial LpL transcription and expression in a cell-specific manner and that these changes in arterial wall LpL are largely associated with modulation of aortic macrophage-LpL. Decreased number of arterial macrophages with the apparent decrease in macrophage-LpL expression is, we suggest, an important mechanism underlying the reduced levels of aortic LpL mediated by n-3 feeding. Decreased numbers of arterial macrophages after n-3 feeding likely link to anti-inflammatory pathways associated with n-3 FA 29. Other mechanisms underlying the differential regulation of dietary FA on inflammatory responses could include the alteration of monocyte trafficking and macrophage retention in the arterial wall. It has been shown that n-3 FA reduced inflammatory Ly6Chi monocytes and monocyte infiltration that decreased atherosclerosis in LDLR−/− mice 30.

There is considerable evidence suggesting roles for PPARs in mediating multiple biological events related to atherosclerosis. FA and their derivatives (e.g., eicosanoids) are endogenous ligands for PPARs 31. The interaction of LpL and PPARs has been examined elsewhere 32, 33, and indicates that different PPARs can affect LpL levels. In addition, incubation of macrophages with PPAR agonists has been shown to affect inflammatory gene expression 33–35, which could also contribute to changes in arterial LpL levels and activity. Our findings show PPARα and PPARγ expression levels were increased by both SAT and n-3 FA, whereas PPARβ/δ was increased by SAT, but decreased by n-3 diets. We speculate that PPARβ/δ may have a role in mediating FA-induced atherogenic effects by regulating LpL expression involved in arterial lipid deposition and inflammatory responses. While sample size was small in examining macrophage-specific LpL and PPARs by LCM, the data points towards underlying mechanisms that may contribute to an understanding of effects mediated by n-3 vs. SAT diets.

Low or moderate intake of n-3 FA (250~500 mg/day) may decrease risk for CVD events 36, 37. In these studies, progressive addition of n-3 fats in diets progressively increased n-3 EPA, docosapentaenoic acid (DPA) and DHA in artery (Table 1). We postulate that changes in aortic fatty acid composition can affect a number of pathways related to atherogenesis. It has been reported that n-3 incorporation into cell membrane phospholipids modulated membrane fluidity by altering the properties of lipid rafts and caveolae, leading to modulation of membrane-associated proteins and receptor activities 38,. Membrane incorporation of n-3 FA decreased the generation of intracellular reactive oxygen species with a subsequent diminished activation of redox-sensitive transcription factors, such as nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) 39. n-3 FA signaling through a G-protein coupled receptor, GPR120, is reported to modulate inflammation and insulin-sensitizing effects in monocytes and macrophages 40.

Increased polyunsaturated n-6 FA intake is associated with reduced risk of CVD 41. However, concerns have been raised regarding high n-6 intake may accelerate the conversion of n-6 18: 2 LA into 20:4 AA, which is a major substrate of pro-inflammatory eicosanoids and cytokines. Although there are inconsistent findings of protective effects of n-3 FA on atherogenesis in animal models 30, 42, lower ratios of n-6/n-3 FA intakes are still favorable toward reducing atherosclerosis 43, 44. Might our results be related to the effects of the different diets on n-6 FA intake? We suggest this is not the case for the following reasons. In our studies, all high-fat diets utilized in our feeding studies contained n-6 LA at much lower but equivalent levels (~8% LA in total FA, supplemental Table II) when compared with the chow diet (50% LA). However, increasing n-3 fish oil intake decreased LA levels in mouse plasma and artery when compared with SAT (Table 1). In fact, all diets containing n-3 FA reduced plasma lipids and significantly reduced atherosclerosis even when compared with the SAT or n-6-rich chow diet. Therefore, we suggest that it is n-3 FA, rather than n-6 FA, that accounted for improving plasma lipid profiles and slowing atherosclerosis.

In our previous studies, we have showed that dietary intake of n-3 FA inhibited factors that initiate atherosclerosis such as elevated cholesterol levels and arterial LDL deposition, even before the appearance of the atherosclerotic lesions 4, 5. Our current studies carried out in an atherosclerosis-prone mouse model demonstrate directly that, even in the setting of a high-total fat, high-cholesterol, SAT-enriched diet, n-3 FA were effective in reducing atherosclerotic lesion formation. We suggest a number of mechanisms underlying protection from arterial lipid deposition and atherosclerosis by dietary n-3 FA. These include effects on ameliorating adverse plasma lipid profiles and reducing aortic macrophages, macrophage-associated LpL and pro-inflammatory markers. While some controversy continues in the recent literature showing inconsistent effects of n-3 FA on reducing CVD mortality after a cardiac event 12, 13. Potential reasons for different results in human n-3 trials have been reviewed elsewhere 13, 45, 46. Still, many mechanistic studies indicate beneficial effects of n-3 FA in preventing adverse outcomes in the pathogenesis of CVD. We now provide additional evidence and describe underlying pathways that highlight the role of n-3 FA as part of strategic approaches to decrease risks for CVD in humans.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Incremental increasing n-3 fatty acids reduce atherosclerosis in LDLR−/− mice.

Low n-3 fatty acid intakes abrogate saturated fatty acid-mediated dyslipidemia.

Saturated fats increase macrophages that secret LpL, and accelerate atherogenesis.

Dietary n-3 fatty acid inclusion decreases aortic inflammatory cells and LpL.

Acknowledgments

We thank Inge H. Hansen for assisting in the analyses included in this paper.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant HL40404 (R.J.D.), T32 DK007647/HL007343 (C.L.C.), and a fellowship from the International Nutrition Foundation/Ellison Medical Foundation (C.T.).

ABBREVIATIONS

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- FA

fatty acid

- IL

interleukin

- LDLR

LDL receptor

- LpL

lipoprotein lipase

- n-3

omega-3

- PPAR

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- SAT

saturated fatty acid

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Seo T, Qi K, Chang C, Liu Y, Worgall TS, Ramakrishnan R, Deckelbaum RJ. Saturated fat-rich diet enhances selective uptake of LDL cholesteryl esters in the arterial wall. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2214–2222. doi: 10.1172/JCI24327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Pascale C, Avella M, Perona JS, Ruiz-Gutierrez V, Wheeler-Jones CP, Botham KM. Fatty acid composition of chylomicron remnant-like particles influences their uptake and induction of lipid accumulation in macrophages. FEBS J. 2006;273:5632–5640. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sudheendran S, Chang CC, Deckelbaum RJ. N-3 vs. saturated fatty acids: effects on the arterial wall. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2010;82:205–209. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang CL, Seo T, Matsuzaki M, Worgall TS, Deckelbaum RJ. n-3 fatty acids reduce arterial LDL-cholesterol delivery and arterial lipoprotein lipase levels and lipase distribution. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:555–561. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.182287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang CL, Seo T, Du CB, Accili D, Deckelbaum RJ. n-3 Fatty acids decrease arterial low-density lipoprotein cholesterol delivery and lipoprotein lipase levels in insulin-resistant mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:2510–2517. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.215848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jung UJ, Torrejon C, Tighe AP, Deckelbaum RJ. n-3 Fatty acids and cardiovascular disease: mechanisms underlying beneficial effects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:2003S–2009S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.6.2003S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Caterina R. n-3 fatty acids in cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2439–2450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1008153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calder PC, Yaqoob P. Understanding omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Postgrad Med. 2009;121:148–157. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2009.11.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kennedy ET, Bowman SA, Powell R. Dietary-fat intake in the US population. J Am Coll Nutr. 1999;18:207–212. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1999.10718853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris WS, Mozaffarian D, Rimm E, Kris-Etherton P, Rudel LL, Appel LJ, Engler MM, Engler MB, Sacks F. Omega-6 fatty acids and risk for cardiovascular disease: a science advisory from the American Heart Association Nutrition Subcommittee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation. 2009;119:902–907. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramsden CE, Hibbeln JR, Majchrzak SF, Davis JM. n-6 fatty acid-specific and mixed polyunsaturate dietary interventions have different effects on CHD risk: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Nutr. 2010;104:1586–1600. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510004010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rizos EC, Ntzani EE, Bika E, Kostapanos MS, Elisaf MS. Association between omega-3 fatty acid supplementation and risk of major cardiovascular disease events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2012;308:1024–1033. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris WS. Are n-3 fatty acids still cardioprotective? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2013;16:141–149. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32835bf380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.von Schacky C. Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2004;7:131–136. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200403000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daugherty A, Whitman SC. Quantification of atherosclerosis in mice. Methods Mol Biol. 2003;209:293–309. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-340-2:293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ali K, Middleton M, Pure E, Rader DJ. Apolipoprotein E suppresses the type I inflammatory response in vivo. Circ Res. 2005;97:922–927. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000187467.67684.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laskowitz DT, Lee DM, Schmechel D, Staats HF. Altered immune responses in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J Lipid Res. 2000;41:613–620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asset G, Bauge E, Fruchart JC, Dallongeville J. Lack of triglyceride-lowering properties of fish oil in apolipoprotein e-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:401–406. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.3.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qi K, Seo T, Al-Haideri M, Worgall TS, Vogel T, Carpentier YA, Deckelbaum RJ. Omega-3 triglycerides modify blood clearance and tissue targeting pathways of lipid emulsions. Biochemistry. 2002;41:3119–3127. doi: 10.1021/bi015770h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oliveira FL, Rumsey SC, Schlotzer E, Hansen I, Carpentier YA, Deckelbaum RJ. Triglyceride hydrolysis of soy oil vs fish oil emulsions. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1997;21:224–229. doi: 10.1177/0148607197021004224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lepage G, Roy CC. Improved recovery of fatty acid through direct transesterification without prior extraction or purification. J Lipid Res. 1984;25:1391–1396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swayne TC, Boldogh IR, Pon LA. Imaging of the cytoskeleton and mitochondria in fixed budding yeast cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;586:171–184. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-376-3_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trogan E, Choudhury RP, Dansky HM, Rong JX, Breslow JL, Fisher EA. Laser capture microdissection analysis of gene expression in macrophages from atherosclerotic lesions of apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2002;99:2234–2239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042683999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paigen B, Morrow A, Holmes PA, Mitchell D, Williams RA. Quantitative assessment of atherosclerotic lesions in mice. Atherosclerosis. 1987;68:231–240. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(87)90202-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimada M, Ishibashi S, Inaba T, Yagyu H, Harada K, Osuga JI, Ohashi K, Yazaki Y, Yamada N. Suppression of diet-induced atherosclerosis in low density lipoprotein receptor knockout mice overexpressing lipoprotein lipase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:7242–7246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yagyu H, Ishibashi S, Chen Z, Osuga J, Okazaki M, Perrey S, Kitamine T, Shimada M, Ohashi K, Harada K, Shionoiri F, Yahagi N, Gotoda T, Yazaki Y, Yamada N. Overexpressed lipoprotein lipase protects against atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. J Lipid Res. 1999;40:1677–1685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Semenkovich CF, Coleman T, Daugherty A. Effects of heterozygous lipoprotein lipase deficiency on diet-induced atherosclerosis in mice. J Lipid Res. 1998;39:1141–1151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Babaev VR, Patel MB, Semenkovich CF, Fazio S, Linton MF. Macrophage lipoprotein lipase promotes foam cell formation and atherosclerosis in low density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26293–26299. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002423200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calder PC. The role of marine omega-3 (n-3) fatty acids in inflammatory processes, atherosclerosis and plaque stability. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2012;56:1073–1080. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201100710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown AL, Zhu X, Rong S, Shewale S, Seo J, Boudyguina E, Gebre AK, Alexander-Miller MA, Parks JS. Omega-3 fatty acids ameliorate atherosclerosis by favorably altering monocyte subsets and limiting monocyte recruitment to aortic lesions. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2012;32:2122–2130. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.253435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rader DJ, Pure E. Lipoproteins, macrophage function, and atherosclerosis: beyond the foam cell? Cell Metab. 2005;1:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Michaud SE, Renier G. Direct regulatory effect of fatty acids on macrophage lipoprotein lipase: potential role of PPARs. Diabetes. 2001;50:660–666. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.3.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jung UJ, Torrejon C, Chang CL, Hamai H, Worgall TS, Deckelbaum RJ. Fatty acids regulate endothelial lipase and inflammatory markers in macrophages and in mouse aorta: a role for PPARgamma. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:2929–2937. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee CH, Chawla A, Urbiztondo N, Liao D, Boisvert WA, Evans RM, Curtiss LK. Transcriptional repression of atherogenic inflammation: modulation by PPARdelta. Science. 2003;302:453–457. doi: 10.1126/science.1087344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plutzky J. Medicine. PPARs as therapeutic targets: reverse cardiology? Science. 2003;302:406–407. doi: 10.1126/science.1091172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mozaffarian D, Rimm EB. Fish intake, contaminants, and human health: evaluating the risks and the benefits. JAMA. 2006;296:1885–1899. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.15.1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang C, Harris WS, Chung M, Lichtenstein AH, Balk EM, Kupelnick B, Jordan HS, Lau J. n-3 Fatty acids from fish or fish-oil supplements, but not alpha-linolenic acid, benefit cardiovascular disease outcomes in primary- and secondary-prevention studies: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:5–17. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen W, Jump DB, Esselman WJ, Busik JV. Inhibition of cytokine signaling in human retinal endothelial cells through modification of caveolae/lipid rafts by docosahexaenoic acid. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:18–26. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Massaro M, Basta G, Lazzerini G, Carluccio MA, Bosetti F, Solaini G, Visioli F, Paolicchi A, De Caterina R. Quenching of intracellular ROS generation as a mechanism for oleate-induced reduction of endothelial activation and early atherogenesis. Thromb Haemost. 2002;88:335–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oh DY, Talukdar S, Bae EJ, Imamura T, Morinaga H, Fan W, Li P, Lu WJ, Watkins SM, Olefsky JM. GPR120 is an omega-3 fatty acid receptor mediating potent anti-inflammatory and insulin-sensitizing effects. Cell. 2010;142:687–698. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harris W. Omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids: partners in prevention. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2010;13:125–129. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3283357242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang L, Geng Y, Xiao N, Yin M, Mao L, Ren G, Zhang C, Liu P, Lu N, An L, Pan J. High dietary n-6/n-3 PUFA ratio promotes HDL cholesterol level, but does not suppress atherogenesis in apolipoprotein E-null mice 1. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2009;16:463–471. doi: 10.5551/jat.no1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang S, Wu D, Matthan NR, Lamon-Fava S, Lecker JL, Lichtenstein AH. Reduction in dietary omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids: eicosapentaenoic acid plus docosahexaenoic acid ratio minimizes atherosclerotic lesion formation and inflammatory response in the LDL receptor null mouse. Atherosclerosis. 2009;204:147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wan JB, Huang LL, Rong R, Tan R, Wang J, Kang JX. Endogenously decreasing tissue n-6/n-3 fatty acid ratio reduces atherosclerotic lesions in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice by inhibiting systemic and vascular inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:2487–2494. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.210054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deckelbaum RJ, Calder PC. Different outcomes for omega-3 heart trials: why? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2012;15:97–98. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32834ec9e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Calder PC, Deckelbaum RJ. Dietary fatty acids in health and disease: greater controversy, greater interest. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2014;17:111–115. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.