Abstract

The primary cilium is a microtubule-based organelle that functions in sensory and signaling pathways. Defects in ciliogenesis can lead to a group of genetic syndromes known as ciliopathies1–3. However, the regulatory mechanisms of primary ciliogenesis in normal and cancer cells are incompletely understood. Here, we demonstrate that autophagic degradation of a ciliopathy protein OFD1 (oral-facial-digital syndrome 1) at centriolar satellites promotes primary cilium biogenesis. Autophagy is a catabolic pathway in which cytosol, damaged organelles, and protein aggregates are engulfed in autophagosomes and delivered to lysosomes for destruction4. We show that the population of OFD1 at the centriolar satellites is rapidly degraded by autophagy upon serum starvation. In autophagy-deficient Atg5 or Atg3 null mouse embryonic fibroblasts, Ofd1 accumulates at centriolar satellites, leading to fewer and shorter primary cilia and a defective recruitment of BBS4 (Bardet-Biedl syndrome 4) to cilia. These defects are fully rescued by Ofd1 partial knockdown that reduces the population of Ofd1 at the centriolar satellites. More strikingly, OFD1 depletion at centriolar satellite promotes cilia formation in both cycling cells and transformed breast cancer MCF7 cells that normally do not form cilia. This work reveals that removal of OFD1 by autophagy at centriolar satellites represents a general mechanism to promote ciliogenesis in mammalian cells. These findings define a newly recognized role of autophagy in organelle biogenesis.

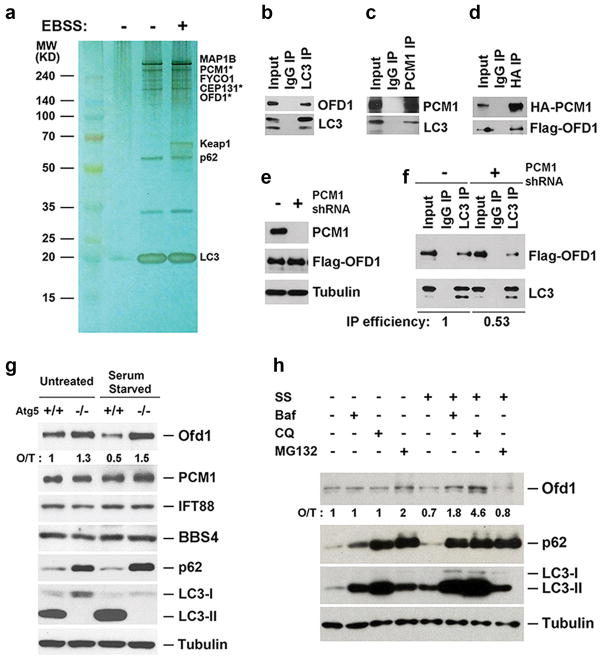

During autophagy, the membrane anchored LC3 (microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3) interacts with cargo and cargo-adaptor proteins, recruiting cargoes to the autophagosome for subsequent degradation upon fusion of the autophagosome with the lysosome5–11. We carried out a tandem-affinity purification using tagged LC3 as bait to search for its interacting proteins (Fig. 1a). In addition to known LC3-interacting proteins (MAP1B, FYCO1, p62, and Keap112), we identified a set of centriolar satellite proteins, including PCM1, OFD1 and CEP131, that had not previously been shown to associate with LC3. PCM1 was also pulled down by LC3 orthologs, GATE16 and GABARAP (Extended Data Fig. 1a). PCM1, OFD1 and LC3 co-immunoprecipitated with each other, suggesting that they are in the same complex (Fig. 1b–1d). PCM1 likely enhances the interaction between LC3 and OFD1, as the OFD1-LC3 interaction is compromised in PCM1-depleted cells (Fig. 1e, f).

Fig. 1. OFD1 is an autophagy substrate.

a, Silver staining of LC3 complexes purified from U2OS cells expressing ZZ-Flag-LC3 in normal medium or Earle’s balanced salt solution (EBSS) for 2-hour. *, centriolar satellites proteins. b, c, d, Co-immunoprecipitation of OFD1 with LC3, LC3 with PCM1, or OFD1 with PCM1 in HEK293T cells. e, Western blotting analysis of PCM1 and OFD1 protein levels in control or PCM1 knockdown (KD) HEK293T cells. f, Co-immunoprecipitation of OFD1 with LC3 in control or PCM1 KD HEK293T cells. IP efficiency is calculated as the ratio of immunoprecipitated OFD1/LC3. g, h, Western blotting analysis of protein levels of indicated proteins in MEFs with indicated genotypes in normal medium or subjected to 24-hour serum starvation (SS), 50 nM bafilomycin A1 (Baf), 20 μM chloroquine (CQ), or 1 μM MG132. Quantified Ofd1 level was normalized with β-tubulin.

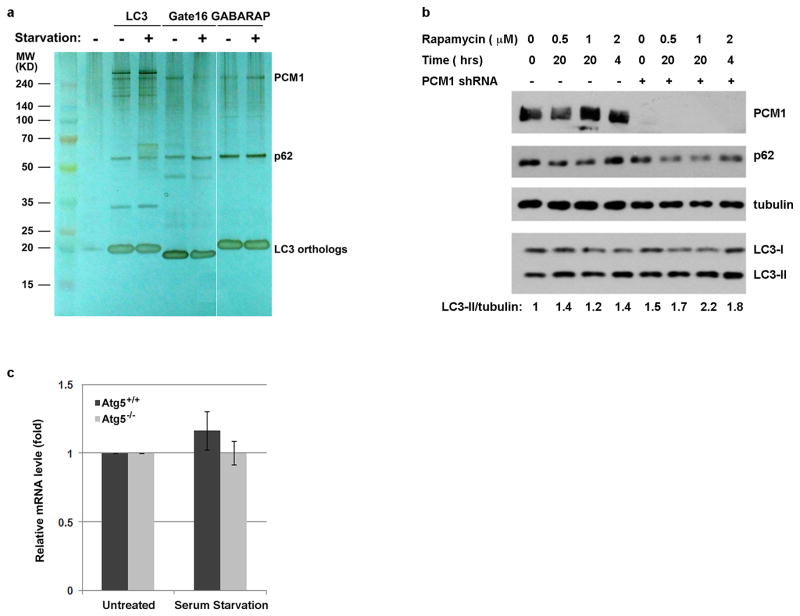

Extended Data Figure 1. LC3-interacting protein PCM1 is not required for autophagy.

a, PCM1 associates with LC3, Gate16 and GABARAP. Silver staining of LC3, Gate16 or GABARAP complexes purified from U2OS cells that stably express ZZ-Flag-LC3, ZZ-Flag-Gate16, or ZZ-Flag-GABARAP in normal medium or subjected to 2-hour Earle’s balanced salt solution (EBSS) starvation. Both PCM1 and p62 were identified by mass spectrometry analysis. b, PCM1 is not required for autophagy. Western blotting analysis of p62, LC3-I/II, PCM1 levels in control or PCM1 shRNA knockdown U2OS cells in normal medium or subjected to rapamycin treatment, quantified LC3-II level was normalized with β-tubulin. c, Ofd1 messenger RNA levels remain unchanged upon serum starvation. Quantitative analysis of messenger RNA levels of Ofd1 in Atg5+/+ and Atg5−/− MEFs in normal medium or subjected to 24-hour serum starvation. Ofd1 mRNA levels were detected by quantitative RT–PCR and plotted after normalization. b–c, Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments.

Depletion of PCM1 by RNA interference had no significant effect on autophagy activity as determined by LC3 lipidation and p62 degradation (Extended Data Fig. 1b). We then examined if any of these centriolar satellite proteins is an autophagy substrate. Ofd1 protein levels were reduced by serum starvation and this reduction was compromised in autophagy-deficient Atg5−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) compared to Atg5+/+ MEFs, whereas PCM1, IFT88 and BBS4 protein levels were not altered by serum starvation or in Atg5−/− MEFs (Fig. 1g). The messenger RNA levels of Ofd1 were not significantly changed upon serum starvation in Atg5+/+ and Atg5−/− MEFs (Extended Data Fig. 1c), suggesting that Ofd1 protein level reduction upon serum starvation is through protein degradation rather than transcriptional downregulation. Blocking autophagic flux by lysosomal inhibitors bafilomycin A1 (Baf) or chloroquine (CQ) resulted in increased Ofd1 accumulation upon serum starvation (Fig. 1h). Taken together, these data suggest that Ofd1 is degraded via the autophagy-lysosome pathway upon serum starvation.

OFD1 is the gene underlying the human disease oral-facial-digital syndrome type 1 (OFD1), an X-linked ciliopathy characterized by morphological abnormalities and renal cysts, as well as Joubert syndrome and Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome type 213–18. OFD1 localizes to the distal ends of centrioles and is necessary for distal appendage formation, IFT88 recruitment, and primary cilium formation18,19. OFD1 also localizes to centriolar satellites, interacting with proteins associated with human ciliary disease, PCM1, Cep290, BBS420. However, the function of this OFD1 population remains unclear.

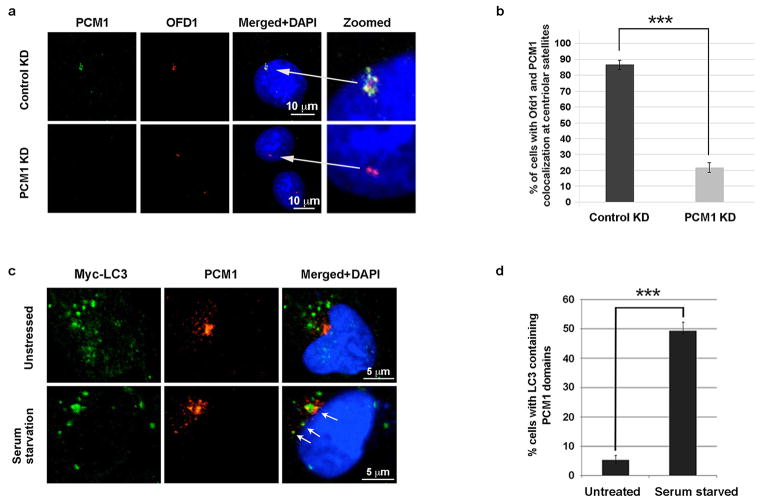

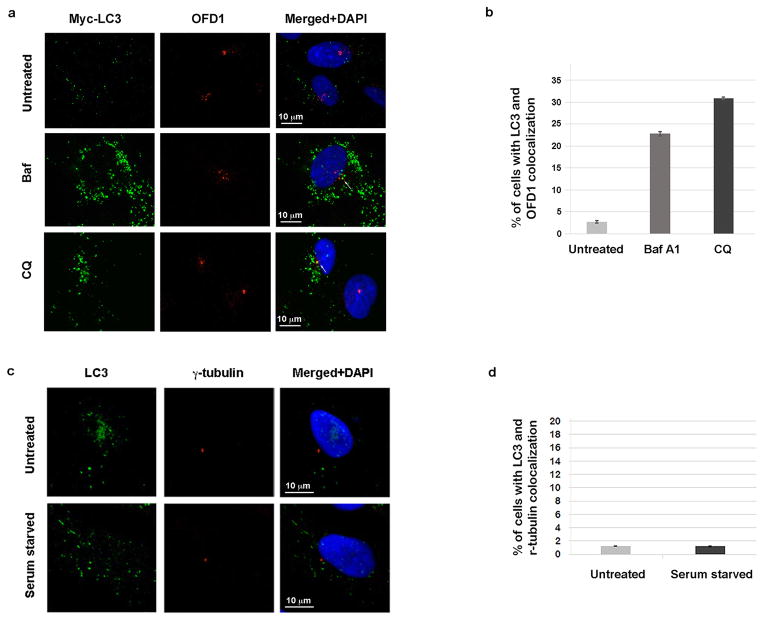

The centriolar satellite localization of OFD1 is determined by PCM1, since OFD1 was lost from satellites when PCM1 was depleted (Extended Data Fig. 2a, b). LC3 partially colocalized with PCM1 upon serum starvation in a majority of retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells, but rarely in unstressed cells (Extended Data Fig. 2c, d). LC3 also partially colocalized with endogenous OFD1 when lysosome activity is blocked by Baf or CQ treatment (Extended Data Fig. 3a, b). This colocalization was limited to the centriolar satellites, as LC3 did not colocalize with the centriole marker γ-tubulin (Extended Data Fig. 3c, d).

Extended Data Figure 2. PCM1 is required for OFD1 centriolar satellite localization.

a, Representative confocal images of OFD1 and PCM1 localization from control or PCM1 knockdown U2OS cells in normal medium. Data shown represent for 100 cells per well in triplicate samples. Scale bar, 10 mm. b, Quantified percentage of cells with PCM1 positive centriolar satellite OFD1 in a. Data shown represent 100 cells per well in triplicated samples. ***P<0.001, two-tailed unpaired student’s t-test. c, LC3 partially colocalizes with PCM1 upon serum starvation. Representative confocal images of Myc-LC3 and PCM1 colocalization in U2OS cells expressing Myc-LC3 in normal medium or subjected to 24-hour serum starvation. Arrows denote colocalized LC3 (green) and PCM1 (red) puncta. Data shown represent for 100 cells per well in triplicate samples. Scale bar, 5 mm. d, Quantified percentage of cells with colocalization of Myc-LC3 and PCM1 in c. ***P<0.001, two-tailed unpaired student’s t-test.

Extended Data Figure 3. LC3 partially colocalizes with OFD1 but not with g-tubulin.

a, LC3 colocalizes with OFD1 when the lysosome activity is blocked. Representative confocal images of Myc-LC3 and OFD1 colocalization in U2OS cells that stably express Myc-LC3 in normal medium or subjected to 2-hour 50 nM bafilomycin A1 (Baf) or 100 μM chloroquine (CQ). Data shown represent for 100 cells per well in triplicate samples. Scale bar, 10 mm. b, Quantified percentage of cells with colocalization of Myc-LC3 and OFD1 in a. c, LC3 does not colocalizes with centrioles. Representative confocal images of LC3 and g-tubulin colocalization in U2OS cells in normal medium or subjected to 24-hour serum starvation. Data shown represent for 100 cells per well in triplicate samples. Scale bar, 10 mm. d, Quantified percentage of cells with colocalization of LC3 and g-tubulin in c. a–d, Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments.

OFD1 was present at both the centrioles and the centriolar satellites in untreated RPE cells. Remarkably, the centriolar satellite pool of OFD1 was dramatically reduced upon serum starvation, while the population of OFD1 at the centrioles remained unchanged (Fig. 2a). This serum starvation- induced OFD1 degradation from centriolar satellites was blocked in Atg5+/+ MEFs treated with the lysosome inhibitor CQ (Extended Data Fig. 4a, b). Notably, PCM1 protein levels are not controlled by autophagy and the centriolar satellite distribution of PCM1 is not altered upon serum starvation (Fig. 1g, Extended Data Fig. 4c–e), suggesting that the autophagic degradation is specific to OFD1 at centriolar satellites rather than centriolar satellites as a whole. This notion is further supported by our observation that Ofd1 remained at centriolar satellites upon serum starvation in Atg5−/− MEFs but was lost from centriolar satellites in Atg5+/+ MEFs (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2. Autophagy specifically degrades OFD1 at centriolar satellites upon serum starvation.

a, Representative confocal images of OFD1 puncta with cilium marker acetylated tubulin, or centriole marker γ-tubulin in hTERT-RPE1 cells in normal medium or subjected to 24-hour serum starvation. b, Representative confocal images of endogenous Ofd1 and acetylated tubulin in Atg5+/+ and Atg5−/− MEFs subjected to 24-hour serum starvation. a, b, Data shown represent mean ± s.d. percentage of cells with centriolar satellite OFD1 for 100 cells per well in triplicate samples. ***P<0.001, two-tailed unpaired student’s t-test. Similar results were observed in three independent experiments.

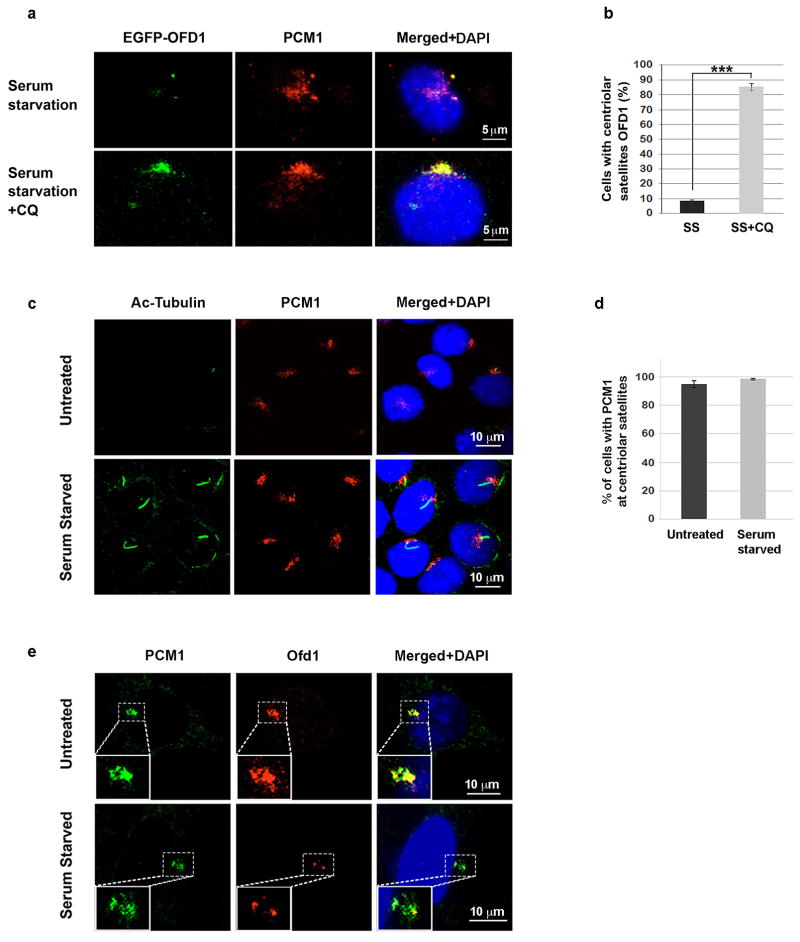

Extended Data Figure 4. OFD1 but not PCM1 at centriolar satellite was degraded by autophagy.

a, OFD1 accumulates at centriolar satellites in CQ-treated cells. Representative confocal images of EGFP-OFD1 and PCM1 colocalization in Atg5+/+ cells expressing EGFP-OFD1 subjected to 24-hour serum starvation or 20 μM CQ. b, Quantified percentage of cells with centriolar satellites OFD1 in a. Data shown represent mean ± s.d. for 100 cells per well in triplicate samples. ***P<0.001, two-tailed unpaired student’s t-test. c, PCM1 is not degraded upon serum starvation. Representative confocal images of PCM1 centriolar satellite staining in Atg5+/+ cells in normal medium or subjected to 24-hour serum starvation. Data shown represent for mean ± s.d. 200 cells per well in triplicate samples. d, Quantified percentage of cells with PCM1 centriolar satellite staining in c. e, Ofd1 but not PCM1 is degraded from centriolar satellites upon serum starvation. Representative confocal images of PCM1 and Ofd1 colocalization in Atg5+/+ cells in normal medium or subjected to 24-hour serum starvation. Data shown represent for 200 cells per well in triplicated samples. Enlarged images were shown in the left bottom panels. a–e, Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments.

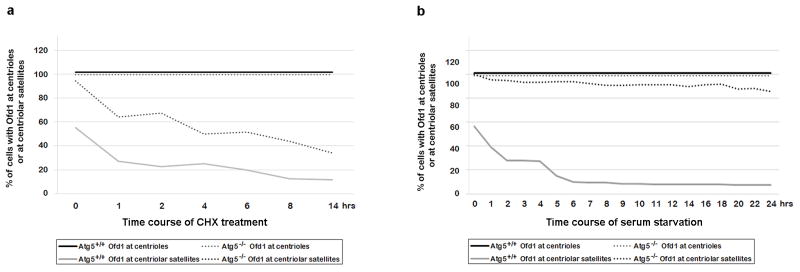

The loss of Ofd1 from centriolar satellites was significantly faster than the loss of Ofd1 from centrioles, and the rate of loss of Ofd1 in Atg5−/− MEFs was slower than that in Atg5+/+ MEFs (Extended Data Fig. 5a). The centriolar satellite pool of Ofd1 in Atg5+/+ cells was lost within six hours of serum starvation, whereas this pool of Ofd1 in Atg5−/− cells remained stable even after twenty-four hours of serum starvation (Extended Data Fig. 5b). These data confirm that Ofd1 at centriolar satellites has a faster turnover rate than Ofd1 at centrioles, and this serum starvation induced accelerated degradation is controlled by autophagy.

Extended Data Figure 5. The turnover rate of centriolar satellite Ofd1 is faster than Ofd1 at centrioles.

a, Centriolar satellite Ofd1 has a shorter half-life compared to Ofd1 at centrioles. Quantified percentage of cells with Ofd1 at centrioles or at centriolar satellites from Atg5+/+ and Atg5−/− MEFs in normal medium or subjected to 75 μM cycloheximide (CHX) with indicated time points. Data shown represent for 200 cells per well in triplicate samples. b, Centriolar satellite Ofd1 but not centriole Ofd1 degrades upon serum starvation. Quantified percentage of cells with Ofd1 at centrioles or at centriolar satellites from Atg5+/+ and Atg5−/− MEFs in normal medium or subjected to serum starvation with indicated time points. Data shown represent for 200 cells per well in triplicate samples. a, b, Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments.

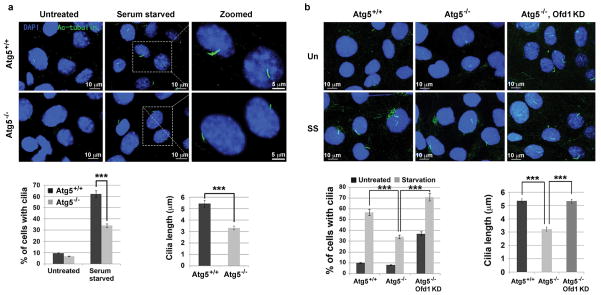

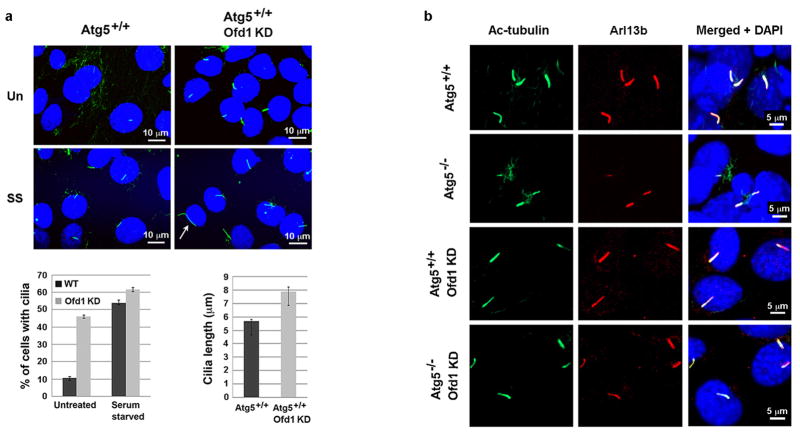

We next sought to understand how OFD1 regulation might affect ciliogenesis. We observed that the percentage of Atg5−/− cells that form a primary cilium, as compared to Atg5+/+ cells, was significantly reduced and the cilia that did form were shorter (Fig. 3a). This difference was not due to cell cycle regulation (Extended Data Fig. 6a). Lysosome inhibition also compromised primary ciliogenesis in Atg5+/+ MEFs (Extended Data Fig. 6b–d). The defective ciliogenesis phenotypes were not limited to Atg5−/− MEFs, as similar phenotypes were also observed in MEFs lacking another essential autophagy gene, Atg3 (Extended Data Fig. 6e–g).

Fig. 3. Autophagy promotes primary cilia biogenesis by regulating Ofd1 levels.

a, b, Representative confocal images of cilium marker acetylated tubulin from MEFs with indicated genotype subjected to 24 hour serum starvation, Data shown represent mean ± s.d. percentage of cells with primary cilia or length of the cilia for 500 cells or 100 cells per well, respectively, in triplicate samples. ***P<0.001, two-tailed unpaired student’s t-test. Similar results were observed in three independent experiments. UN, untreated. SS, serum starved.

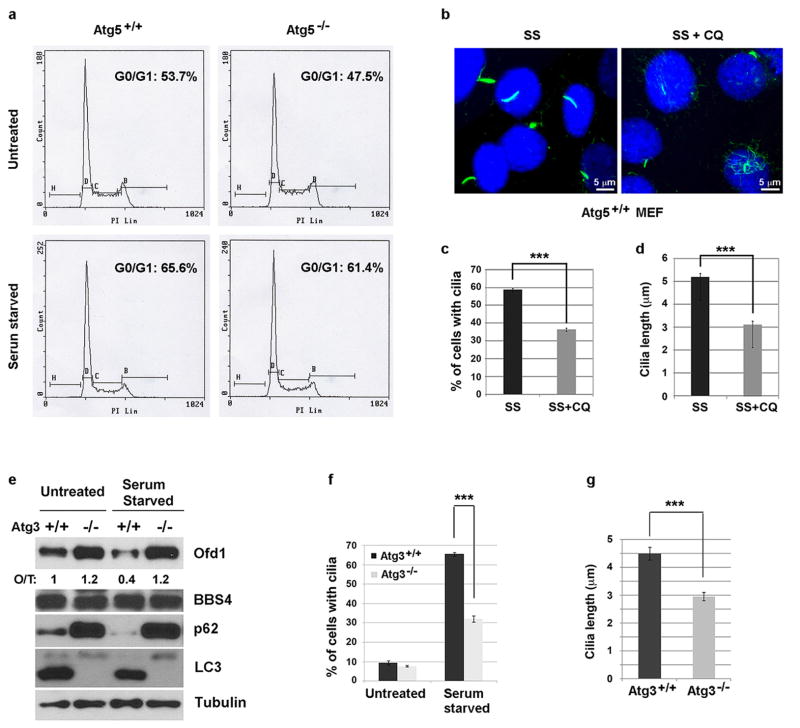

Extended Data Figure 6. Autophagy regulates primary ciliogenesis in a cell cycle independent manner.

a, FACS analysis of Atg5+/+ and Atg5−/− MEFs in normal medium or subjected to 24-hour serum starvation. Data shown represent for 1×106 cells per well in triplicate samples. b, Primary ciliogenesis is less efficient when the lysosome activity is blocked in MEFs. Representative confocal images of primary cilia formed in Atg5+/+ MEFs subjected to 24-hour serum starvation alone or combined with 20 μM CQ treatment. c, Quantified percentage of cells with primary cilia in b. d, Quantified length of primary cilia in b. e, Degradation of Ofd1 is also blocked in Atg3 −/− MEFs. Western blot analysis of Ofd1, p62, LC3-I/II and BBS4 protein levels in MEFs with indicated genotypes in normal medium or subjected to 24-hour serum starvation, quantified Ofd1 levels were normalized with β-tubulin. f, g, Primary ciliogenesis is also defective in Atg3−/− MEFs. f, Quantified percentage of cells with primary cilia in Atg3+/+ and Atg3−/− MEFs in normal medium or subjected to 24-hour serum starvation. g, Quantified length of primary cilia formed in Atg3+/+ and Atg3−/− MEFs as described in f. c, d, f, g, Data shown represent mean ± s.d. for 100 cells per well in triplicate samples. ***P<0.001, two-tailed unpaired student’s t-test. a–g, Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments.

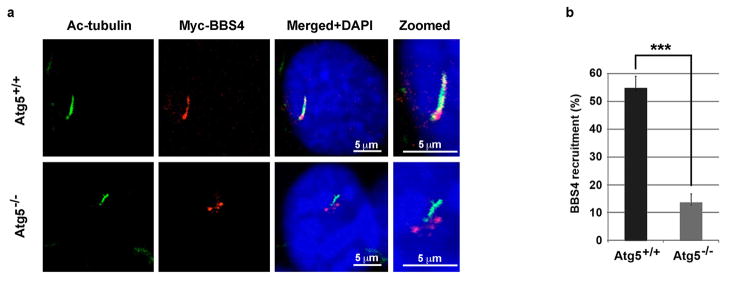

We next investigated if the ciliary recruitment of BBS4, a critical event for ciliogenesis19,21, is affected in autophagy-deficient cells. We observed that BBS4 accumulated at centriolar satellites in Atg5−/− MEFs; more than 50% of cilia had detectable BBS4 in Atg5+/+ MEFs, whereas only about 10% of cilia were positive for BBS4 in Atg5−/− MEFs (Extended Data Fig. 7). These data indicate that BBS4 recruitment to cilia is also defective in autophagy deficient cells.

Extended Data Figure 7. BBS4 recruitment to primary cilia is defective in Atg5−/− MEFs.

a, Representative confocal images of Atg5+/+ and Atg5−/− MEFs expressing Myc-BBS4 subjected to 24-hour serum starvation. Scale bar 5 μm. b, Quantified percentage of cells with Myc-BBS4 translocation into primary cilia in Atg5+/+ and Atg5−/− MEFs. Data shown represent mean ± s.d. for 100 cells per well in triplicate samples. ***P<0.001, two-tailed unpaired student’s t-test. a, b, Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments.

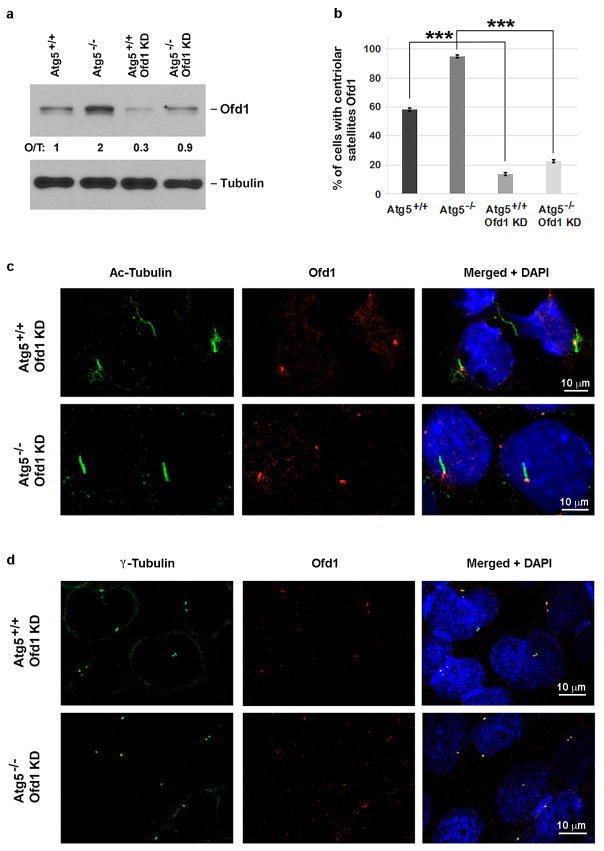

If Ofd1 accumulation at centriolar satellites is responsible for the ciliary defects in Atg5−/− MEFs, we would expect that depletion of Ofd1 by RNA interference might rescue these defects. In Atg5−/− MEFs stably expressing Ofd1 shRNA, with about 50% efficiency of overall depletion of Ofd1 (Extended Data Fig. 8a), Ofd1 remained at centrioles but was lost from centriolar satellites (Extended Data Fig. 8b–d). Primary cilium formation upon serum starvation was fully restored in these cells; nearly 70% of cells formed a cilium and the length of these cilia was comparable to those formed in Atg5+/+ MEFs (Fig. 3b). Hence, the centriolar satellite pool of Ofd1 indeed plays a key role in suppressing primary ciliogenesis in Atg5−/− MEFs. Strikingly, with Ofd1 knockdown, nearly 35% of the Atg5−/− cells formed cilia even without serum starvation (Fig. 3b), suggesting that Ofd1 degradation is likely required for serum starvation-induced primary ciliogenesis. This notion is supported by the observation that primary cilia formed efficiently even in the cycling Atg5+/+ MEFs depleted of Ofd1 without serum starvation (Extended Data Fig. 9a). The presence of cilia in MEFs was further confirmed by the positive staining of the cilium marker Arl13b (Extended Data Fig. 9b), which specifically decorates the ciliary membrane22.

Extended Data Figure 8. Partial shRNA knockdown of Ofd1 leads to depletion of Ofd1 from centriolar satellites in Atg5+/+ and Atg5−/− MEFs.

a, Western blot analysis of Ofd1 in MEFs with indicated genotypes in normal medium. Quantified Ofd1 levels were normalized with β-tubulin. KD, knockdown. b, Quantified percentage of cells with centriolar satellite Ofd1 in MEFs with indicated genotypes in normal medium. Data shown represent mean ± s.d. percentage of cells with centriolar satellite Ofd1 for 100 cells per well in triplicated samples. ***P<0.001, two-tailed unpaired student’s t-test. c, d, Ofd1 was depleted from centriolar satellites but not centrioles in Ofd1 knockdown MEFs. Representative confocal images of Ofd1 and axoneme marker acetylated tubulin in c or centriole marker g-tubulin in d in MEFs with indicated genotypes in normal medium. Data shown represent for 100 cells per well in triplicate samples. Scale bar 10 μm. a–d, Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments.

Extended Data Figure 9. Knockdown of Ofd1 in wild-type MEFs promotes primary ciliogenesis.

a, Representative confocal images of primary cilia formed in MEFs with indicated genotypes in normal medium (Un) or subjected to 24-hour serum starvation (SS). Quantified percentage of cells with primary cilia and the length of primary cilia from MEFs with indicated genotypes were shown in the bottom panels. Data shown represent mean ± s.d. for 100 cells per well in triplicate samples. Scale bar 10 mm. b, Representative confocal images of primary cilia formed in MEFs with indicated genotypes subjected to 24-hour serum starvation. The primary cilia formed are positive for both axoneme marker acetylated tubulin and cilia membrane marker Arl13b. Data shown represent for 100 cells per well in triplicate samples. Scale bar 5 mm. a, b, Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments.

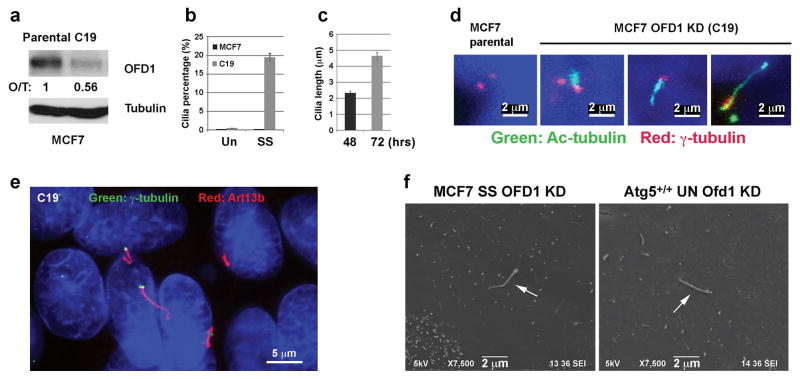

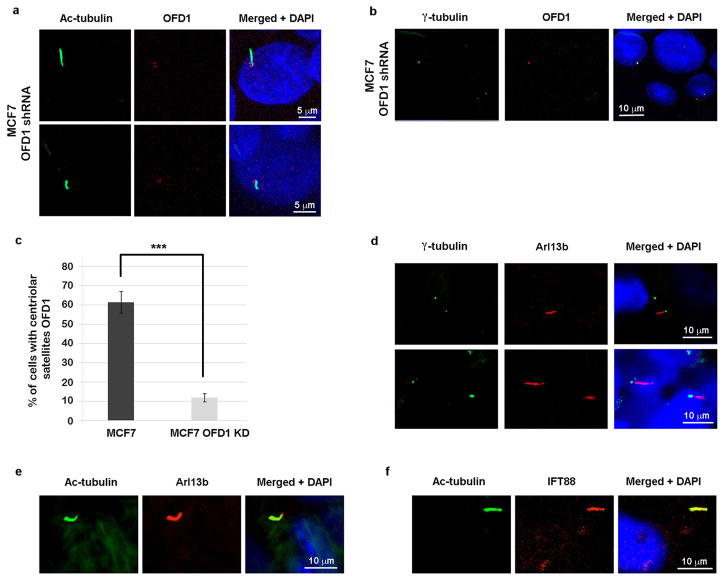

Primary cilia are formed in normal breast epithelial cells but not detected in breast cancer cell lines such as MCF723. Restoration of primary cilia in human cancer cells might be beneficial to reduce malignancy, since cilia are required for proper functions of several signaling pathways (hedgehog etc.) that play crucial roles in many types of cancers24. We further tested if OFD1 reduction could restore primary ciliogenesis in MCF7 cells. We generated an OFD1 stable knockdown clone (C19) in MCF7 cells, which exhibited 44% ODF1 depletion efficiency (Fig. 4a). Similar to OFD1 knockdown MEFs, the centriolar satellite population of OFD1 in C19 cells was dramatically reduced, while the centriole pool remained stable (Extended Data Fig. 10a–c). Remarkably, primary cilia formed in about 20% C19 cells upon serum starvation, but were completely absent in parental MCF7 cells (Fig. 4b, c). The length of these cilia ranged from 2 μm to 6 μm (Fig. 4d). As expected for normal primary cilia, these cilia extended from basal bodies and were positive for Arl13b, acetylated-tubulin, and the intraflagellar transport protein IFT88 (Fig. 4e, Extended Data Fig. 10d–f). Finally these cilia could be directly visualized under the scanning electron microscope (Fig. 4f). Thus, by manipulating the expression of one protein, OFD1, it is possible to reverse the cilia-defective phenotype of a transformed breast cancer cell line. Primary ciliogenesis remains inefficient in C19 cells, suggesting that addition factors are required to reach full capacity. Nevertheless, these data confirm that OFD1 at the centriolar satellite functions as a crucial suppressor of primary ciliogenesis in human cancer cells.

Fig. 4. Forced OFD1 reduction promotes ciliogenesis in human breast cancer MCF7 cells.

a, Western blotting analysis of OFD1 protein levels in control or OFD1 knockdown MCF7 (C-19) cells, quantified Ofd1 level was normalized with β-tubulin. b, Quantification of percentage of cells with primary cilia in MCF7 or C19 cells subjected to 72-hour serum starvation. Data shown represent mean ± s.d. percentage of cells with primary cilia for 500 cells per well in triplicate samples. c, Quantification of length of primary cilia in C19 cells subject to 48-hour or 72-hour serum starvation. d, e, Representative confocal images of primary cilia with variable length formed in MCF7 or C19 cells subject to 72-hour serum starvation. Data shown represent for 100 cells per well in triplicate samples. f, Scanning electron microscope analysis of primary cilia (marked by arrows) formed in C-19 cells subject to 72-hour serum starvation and cycling Atg5+/+ MEFs in normal medium for 24-hour. In a–e, similar results were observed in three independent experiments.

Extended Data Figure 10. Partial knockdown OFD1 in MCF7 cells depletes OFD1 from centriolar satellites and promotes primary ciliogenesis.

a, b, OFD1 was depleted from centriolar satellites in OFD1 shRNA knockdown MCF7 cells. a, Representative confocal images of relative localization of OFD1 with axoneme marker acetylated tubulin in MCF7 OFD1 Knockdown clone (C19). Data shown represent for 100 cells per well in triplicate samples. Scale bar 5 mm. b, Representative confocal images of OFD1 and centriole marker g-tubulin from C19. Data shown represent for 100 cells per well in triplicated samples. Scale bar 10 mm. c, Quantified percentage of parental MCF7 and C19 cells with centriolar satellite OFD1. Data shown represent mean ± s.d. for 100 cells per well in triplicate samples. ***P<0.001, two-tailed unpaired student’s t-test. d, e, f, Primary cilia formed in OFD1 knockdown C19 MCF7 cells are positive for cilia markers. Representative confocal images of primary cilia formed in C19 subjected to 72-hour serum starvation. Cilia were positive for ciliary membrane marker Arl13b, axoneme marker acetylated tubulin and intraflagellar transport protein IFT88. a–f, Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments.

We show here that autophagy is linked to primary ciliogenesis, by controlling the degradation of OFD1 at centriolar satellites. We propose that autophagy deficiency serves as a potential underlying mechanism of ciliopathies, and that autophagy modulation might provide a novel means of ciliopathy treatment. We demonstrate that OFD1 at centriolar satellites plays a crucial role in suppressing primary ciliogenesis, which is different from OFD1 at centrioles that has been shown to be essential for ciliogenesis. Removing OFD1 from centriolar satellites promotes ciliogenesis in autophagy-deficient cells, wild-type MEFs without serum starvation, and human breast cancer MCF7 cells that normally completely lack cilia, suggesting a general role of OFD1 in suppressing ciliogenesis. Primary ciliogenesis is defective in human breast and pancreatic cancer cells, but activated in the corresponding normal tissues/cells23,25. The contribution of primary cilium function to tumorigenesis is complex26,27, however our results suggest that dissecting the regulatory mechanisms of OFD1 will provide insight into these functions and potentially offer new therapeutic tools for treatment of ciliopathies and cancers.

Methods (online only)

Reagents

Rabbit anti-OFD1 antibody, EGFP-OFD1 and Flag-OFD1 were described before18,30,31. Another rabbit anti-OFD1 antibody was a gift from Jeremy Reiter at University of California at San Francisco. Rabbit anti-IFT88 antibody was a gift from Bradley Yoder at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. To generate BBS4-MycHAHis (pTS1686), BBS4 was PCR-amplified, verified by sequencing and cloned into a pEGFP-N1-derived plasmid (Clontech Laboratories, Inc.) in which GFP was replaced with a Myc-HA-His tag created as BBS4-MycHAHis32. Primary antibodies used for western blotting and immunostaining are; rabbit anti-PCM1 (Cell signaling), mouse anti-PCM1 (Sigma), mouse anti-β-tubulin (Sigma); rabbit anti-p62 (MBL); rabbit anti-LC3 (Sigma), mouse anti-tubulin (Sigma), mouse anti-acetylate tubulin (Sigma), mouse or rabbit anti-γ tubulin (Sigma), BBS4 (Santa Cruz), chloroquine (Sigma), bafilomycin A1 and rapamycin (LC Laboratories), and MG132 (Alexis).

Cell culture and transfection

HEK293T, MCF7 and MEFs were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin and streptomycin in a 5% CO2 incubator (Thermo). hTERT-RPE1 cells were cultured in DMEM/Hams F12 with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin at streptomycin in a 5% CO2 incubator (Thermo). Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) was used for mammalian cell transfection. Cells were incubated in OPTI medium (GIBCO 51985091) for one hour before transfection. 10 μg or 5 μg plasmid was used for each 150 mm or 100 mm tissue culture dish, respectively. U2OS cells stably expressing Myc-LC3 were described before28. Atg5+/+ and Atg5−/− MEFs were kind gifts from Noboru Mizushima at Tokyo Medical and Dental University33. Atg3+/+ and Atg3−/− MEFs were kind gifts from Masaaki Komatsu at Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science34. PCM1 shRNA knockdown was carried out using a 19-mer shRNA targeting human PCM1 with the sequence: 5′-GTATCACATCTGAACTAAA-3′ (pTS2063). PCM1 shRNA oligos were designed using pSicoOligomaker 1.5, annealed and subcloned into the lentiviral vector, pSicoR-puro, which confers puromycin resistance. Stable depletion of PCM1 was carried out by infection of cells with shRNA-expressing lentiviral particles and selection with puromycin (3 μg/ml); positive clones were screened by western blotting. Stable depletion of OFD1 was carried out by infection of cells with shRNA-expressing lentiviral particles (sc-91245-V, from Santa Cruz) and selection with puromycin (1 μg/ml or 10 μg/ml) for MCF7 cells or MEFs, positive clones were screened by western blotting. The OFD1 Lentiviral Particles are a pool of 3 different shRNA plasmids, targeting the OFD1 sequence: 5′-GGAUGACUACAUC AUUAGAtt-3′, 5′-CUACUCAGGUUGCCGAUUUtt-3′, 5′-GAACGAAGAGAACU AGAAAtt-3′,

Primary Cilia biogenesis assay

Equal numbers (3×105 for serum rich medium and 4.5×105 for serum starved medium) of Atg5+/+ MEFS and Atg5−/− MEFs were seeded into 6-well dishes. After cells were attached on the coverslips for 8 hours, they were incubated in either fresh regular medium (10% FBS, 1% P/S DMEM) or serum starved medium (0.5% FBS, 1% P/S DMEM) for 24 hours. Cells were seeded at different numbers at beginning to ensure that these cells reach the same confluence one day after treatment. Cells were then fixed for immunofluorescence staining. For western blotting, cells cultured in 10 cm dishes were serum starved alone or in combination with 50 nM bafilomycin A1, 20 μM chloroquine or 1 μM MG132 treatment for 24 hours and lysed with TAP buffer.

Immunofluorescence Staining

Cells were treated according to the protocol described above with or without serum starvation or compound treatment. Cells were fixed with cold methanol for five minutes at −20°C. Cells were then washed three times with PBS and then blocked with blocking buffer (2.5% BSA + 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS) at room temperature for one hour. Cells were incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight, washed five times with PBS buffer and then incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa 488- Alexa 549 (Molecular Probes) for two hours at room temperature. DNA was stained with DAPI. Slides were examined using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 510 META UV/Vis).

Autophagy Analysis

Autophagy was induced by serum starvation or rapamycin treatment, or blocked by lysosome inhibitors, chloroquine or bafilomycin A1. For rapamycin (LC Laboratories) treatment, cells were incubated with 500nM rapamycin in complete medium for 16 hours at 37°C. To block autophagy flux, 50 nM Bafilomycin A1 (LC Laboratories) or 20 μM chloroquine (Sigma) was added to complete medium or serum starvation medium and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Autophagy activity was assessed using two approaches, LC3-II formation and p62 degradation. For LC3-II and p62 detection, cell lysates were prepared as described above and subjected to standard western blotting protocols using 1:10,000 dilution of the antibody against LC3 (Sigma) and 1:1,000 dilution of the antibody against p62 (MBL).

Establishment of stable RNA interference cell lines

Human MCF7 cells or Atg5+/+ and Atg5−/− MEFs were seeded into 12-well dishes at 50% confluency before transfection. 24 hours after seeding, cells were incubated with complete medium containing 5 μg/ml polybrene (Santa Cruz), and infected overnight with lentiviral particles carrying short hairpin RNA OFD1 (Santa Cruz). 24 h later, cells were selected with puromycin (Invitrogen) (1 μg/ml for MCF 7 or 10 μg/ml for MEFs) until positive clones were identified. Single clones were picked and identified by western blotting or immunofluorescence analysis.

Cell cycle analysis

1×106 cells were centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 minutes, washed once with PBS, and pellets were resuspended in 1 ml PBS and fixed overnight in 75% ethanol at −20°C. Fixed cells were washed three times with 10 ml PBS, resuspended in 200–400 μl PBS with 10 μl RNAase (Qiagen) at 37°C for 30 minutes in the dark. Cells were subjected to FACS analysis using DAKO-Cytomation MoFlo High Speed Sorter at the Flow Cytometry Facility at UC Berkeley.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblot

Transfected cells were lysed in TAP lysis buffer on ice for 30 minutes, and centrifuged at 13,000 g for 15 minutes. For immunoprecipitation, cell lysates were incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C, and then incubated with IgG beads for 2 hours at 4°C. The beads were washed 5 times with 1 ml of lysis buffer and boiled in SDS sample buffer. Co-immunoprecipitated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad), and detected with antigen-specific primary antibodies followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies.

Tandem Affinity Purification of LC3 Complexes

This protocol is adapted from what was described before12,28,29. Stable cell lines expressing ZZ-Flag-LC3, ZZ-Flag-Gate16, or ZZ-Flag-GABARAP, upon doxycycline induction were treated with 10 ng/ml DOX for one day. The collected cell pellet was washed with chilled PBS three times and suspended in TAP lysis buffer. Resuspended cell pellets were incubated on ice for 30 minutes and then gently vortexed for one minute. Homogenates were centrifuged for 20 minutes at 10,000 g. The supernatants were transferred to fresh tubes containing 0.8 ml of packed IgG beads followed by gentle rotation overnight at 4°C. Bound protein was eluted using TEV protease cleavage and further purified by Anti-Flag M2 Affinity Gel (Sigma). Bound protein was eluted using Flag peptide and resolved using SDS-PAGE on a 4–12% gradient gel (Invitrogen) and visualized by silver staining (Invitrogen). Distinct bands were cut and subjected to mass spectrometry analysis.

Quantitative RT–PCR

Total RNAs were extracted with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen), from which 1 μg was used for reverse transcription in a 20-μL reaction system with the RNA PCR (AMV) kit (Promega). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed with SYBR-Green PCR Mastermix (Applied Biosystems), and amplification was real-time monitored on a MicorAmp optical 96-Well Reaction Plate (Applied Biosystems). The level of transcript abundance relative to reference gene (termed ΔCT) was determined according to the function ΔCT = CT (test gene) − CT (reference gene). To compare untreated and treated expression levels, the function ΔΔCT was first determined using the equation ΔΔ CT = Δ CT (treatment) − Δ CT (control) where control represented mock-treated cells. The induction ratio of treatment/control was then calculated by the equation 2−ΔΔ CT. Gene expression levels were normalized with the Atg5+/+ untreated sample.

Acknowledgments

We thank Noboru Mizushima for Atg5+/+ and Atg5−/− MEFs and Masaaki Komatsu for Atg3+/+ and Atg3−/− MEFs; Haiying Zhou for helpful discussions and quantitative RT-PCR data analysis; Andrew Kodani and Jeremy F. Reiter for reagents, helpful discussions and technical assistance; and Beth Levine for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. The electron microscopy studies were performed by Caroline Miller and Vincent Gattone II at the Indiana University School of Medicine EM Center that is supported by the Polycystic Kidney Disease Foundation. This work was supported by grants (RSG-11-274-01-CCG, CA133228) to Q. Z. and grants (TGM11CB3, n° 241955) to B.F. The work was partially supported by China Scholarship Council to Z.T..

Footnotes

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Readers are welcome to comment on the online version of this article at www.nature.com/nature.

Author Contributions Z.T., M.L. and T.S. performed the experiments; C.S. carried out mass spectrometry analysis; M.Z., T.S. and B.F. provided technical and intellectual support; Z.T. and Q.Z. conceived the project, designed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript with the help of all authors.

References

- 1.Sang L, et al. Mapping the NPHP-JBTS-MKS protein network reveals ciliopathy disease genes and pathways. Cell. 2011;145:513–528. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hildebrandt F, Benzing T, Katsanis N. Ciliopathies. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;364:1533–1543. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1010172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nigg EA, Raff JW. Centrioles, centrosomes, and cilia in health and disease. Cell. 2009;139:663–678. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levine B, Klionsky DJ. Development by self-digestion: molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Dev Cell. 2004;6:463–477. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thurston TL, Ryzhakov G, Bloor S, von Muhlinen N, Randow F. The TBK1 adaptor and autophagy receptor NDP52 restricts the proliferation of ubiquitin-coated bacteria. Nature immunology. 2009;10:1215–1221. doi: 10.1038/ni.1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johansen T, Lamark T. Selective autophagy mediated by autophagic adapter proteins. Autophagy. 2011;7:279–296. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.3.14487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirkin V, McEwan DG, Novak I, Dikic I. A role for ubiquitin in selective autophagy. Mol Cell. 2009;34:259–269. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Novak I, et al. Nix is a selective autophagy receptor for mitochondrial clearance. EMBO reports. 2010;11:45–51. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orvedahl A, et al. Image-based genome-wide siRNA screen identifies selective autophagy factors. Nature. 2011;480:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature10546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y, et al. SEPA-1 mediates the specific recognition and degradation of P granule components by autophagy in C. elegans. Cell. 2009;136:308–321. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirkin V, et al. A role for NBR1 in autophagosomal degradation of ubiquitinated substrates. Mol Cell. 2009;33:505–516. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fan W, et al. Keap1 facilitates p62-mediated ubiquitin aggregate clearance via autophagy. Autophagy. 2010;6 doi: 10.4161/auto.6.5.12189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feather SA, Woolf AS, Donnai D, Malcolm S, Winter RM. The oral-facial-digital syndrome type 1 (OFD1), a cause of polycystic kidney disease and associated malformations, maps to Xp22.2-Xp22.3. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:1163–1167. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.7.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coene KL, et al. OFD1 is mutated in X-linked Joubert syndrome and interacts with LCA5-encoded lebercilin. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85:465–481. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Field M, et al. Expanding the molecular basis and phenotypic spectrum of X-linked Joubert syndrome associated with OFD1 mutations. European journal of human genetics: EJHG. 2012 doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zullo A, et al. Kidney-specific inactivation of Ofd1 leads to renal cystic disease associated with upregulation of the mTOR pathway. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:2792–2803. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrante MI, et al. Identification of the gene for oral-facial-digital type I syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:569–576. doi: 10.1086/318802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferrante MI, et al. Oral-facial-digital type I protein is required for primary cilia formation and left-right axis specification. Nat Genet. 2006;38:112–117. doi: 10.1038/ng1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singla V, Romaguera-Ros M, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Reiter JF. Ofd1, a human disease gene, regulates the length and distal structure of centrioles. Dev Cell. 2010;18:410–424. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lopes CA, et al. Centriolar satellites are assembly points for proteins implicated in human ciliopathies, including oral-facial-digital syndrome 1. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:600–612. doi: 10.1242/jcs.077156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nachury MV, et al. A core complex of BBS proteins cooperates with the GTPase Rab8 to promote ciliary membrane biogenesis. Cell. 2007;129:1201–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cantagrel V, et al. Mutations in the cilia gene ARL13B lead to the classical form of Joubert syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:170–179. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yuan K, et al. Primary cilia are decreased in breast cancer: analysis of a collection of human breast cancer cell lines and tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 2010;58:857–870. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2010.955856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goetz SC, Anderson KV. The primary cilium: a signalling centre during vertebrate development. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:331–344. doi: 10.1038/nrg2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seeley ES, Carriere C, Goetze T, Longnecker DS, Korc M. Pancreatic cancer and precursor pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia lesions are devoid of primary cilia. Cancer Res. 2009;69:422–430. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472. CAN-08-1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong SY, et al. Primary cilia can both mediate and suppress Hedgehog pathway-dependent tumorigenesis. Nat Med. 2009;15:1055–1061. doi: 10.1038/nm.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han YG, et al. Dual and opposing roles of primary cilia in medulloblastoma development. Nat Med. 2009;15:1062–1065. doi: 10.1038/nm.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun Q, et al. Identification of Barkor as a mammalian autophagy-specific factor for Beclin 1 and class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19211–19216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810452105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen D, et al. A mammalian autophagosome maturation mechanism mediated by TECPR1 and the Atg12-Atg5 conjugate. Mol Cell. 2012;45:629–641. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giorgio G, et al. Functional characterization of the OFD1 protein reveals a nuclear localization and physical interaction with subunits of a chromatin remodeling complex. Molecular biology of the cell. 2007;18:4397–4404. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-03-0198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bimonte S, et al. Ofd1 is required in limb bud patterning and endochondral bone development. Developmental biology. 2011;349:179–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stowe TR, Wilkinson CJ, Iqbal A, Stearns T. The centriolar satellite proteins Cep72 and Cep290 interact and are required for recruitment of BBS proteins to the cilium. Molecular biology of the cell. 2012 doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-02-0134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuma A, et al. The role of autophagy during the early neonatal starvation period. Nature. 2004;432:1032–1036. doi: 10.1038/nature03029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sou YS, et al. The Atg8 conjugation system is indispensable for proper development of autophagic isolation membranes in mice. Molecular biology of the cell. 2008;19:4762–4775. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-03-0309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]