Abstract

Preeclampsia is an important cause of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality. Previous studies have tested calcium supplementation and aspirin separately to reduce the incidence of preeclampsia but not the effects of combined supplementation. The objective of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of aspirin combined with calcium supplementation to prevent preeclampsia in women with chronic hypertension. A double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial was carried out at the antenatal clinic of a large university hospital in São Paulo, SP, Brazil. A total of 49 women with chronic hypertension and abnormal uterine artery Doppler at 20-27 weeks gestation were randomly assigned to receive placebo (N = 26) or 100 mg aspirin plus 2 g calcium (N = 23) daily until delivery. The main outcome of this pilot study was development of superimposed preeclampsia. Secondary outcomes were fetal growth restriction and preterm birth. The rate of superimposed preeclampsia was 28.6% lower among women receiving aspirin plus calcium than in the placebo group (52.2 vs 73.1%, respectively, P=0.112). The rate of fetal growth restriction was reduced by 80.8% in the supplemented group (25 vs 4.8% in the placebo vs supplemented groups, respectively; P=0.073). The rate of preterm birth was 33.3% in both groups. The combined supplementation of aspirin and calcium starting at 20-27 weeks of gestation produced a nonsignificant decrease in the incidence of superimposed preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction in hypertensive women with abnormal uterine artery Doppler.

Keywords: Preeclampsia, Hypertension, Ultrasonography, Doppler, Calcium carbonate, Aspirin

Introduction

Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy are still the leading cause of maternal mortality in developing nations. According to the most recent World Health Organization review, hypertensive disorders accounted for 25% of all maternal deaths in Latin America and the Caribbean, leading to 3800 deaths each year in the region (1). Superimposed preeclampsia is a condition characterized by increasing blood pressure and proteinuria after the 20th week of pregnancy in women with pre-existing chronic hypertension (2). Superimposed preeclampsia usually develops earlier than other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, tends to be more severe, and can lead to fetal growth restriction, elective preterm delivery, and increased risk for perinatal mortality. It can also lead to severe adverse maternal outcomes, including hypertensive encephalopathy, heart or kidney failure, placental abruption, HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets) syndrome, and maternal mortality (3-5). It is estimated that approximately 14 to 78% of all women with pre-existing chronic hypertension will develop superimposed preeclampsia during pregnancy; those with abnormal uterine artery Doppler are at even higher risk (4-11).

Second-trimester uterine artery Doppler ultrasound has been used for over a decade to screen women at high risk of preeclampsia. Increased impedance to flow in the uterine arteries in unselected women during the second trimester of pregnancy identifies approximately 40% of those who subsequently will develop preeclampsia. Compared to individual baseline risk, abnormal uterine Doppler findings increase the likelihood of preeclampsia by six times in unselected populations (12).

Screening is only worthwhile if there is an effective intervention available to prevent the disease or improve outcome. In the mid 1980s, small trials suggested that the prophylactic use of antiplatelet agents could reduce the incidence of preeclampsia (13,14). However, subsequent findings of larger trials did not support routine prophylactic or therapeutic use of aspirin (15-18), and a meta-analysis of individual data from 31 trials involving 32,000 women of varying baseline risk concluded that the use of antiplatelet agents during pregnancy is associated with a modest but significant reduction of several outcomes including preeclampsia (RR=0.90, 95%CI=0.84-0.97), delivery before 34 weeks (RR=0.90, 95%CI=0.83-0.98), and any serious adverse outcome (RR=0.90, 95%CI=0.85-0.96) (19). The use of aspirin seems to be more effective in reducing the incidence of preeclampsia in high-risk women than in those of low to moderate risk. A systematic review on aspirin to prevent preeclampsia in women at high risk due to abnormal second-trimester uterine artery Doppler identified five small randomized trials that included a total of approximately 500 women receiving 50-100 mg aspirin daily and reported a significant reduction in the incidence of preeclampsia (OR=0.55, 95%CI=0.32-0.95) (20). However, 2 years later, a large randomized controlled trial that tested low-dose aspirin in 560 women with abnormal artery Doppler at 23 weeks of gestation did not confirm those results. According to the authors, supplementation with 150 mg aspirin did not significantly decrease the incidence of preeclampsia (18 vs 19%, P=0.6 in the aspirin and placebo groups, respectively), preterm delivery due to preeclampsia (6 vs 8%, P=0.36) or birth weight below the fifth centile (22 vs 24%, P=0.4) (21). Supplementation with low-dose aspirin during pregnancy is safe. The incidence of potential adverse effects associated with aspirin, such as ante- or post-partum hemorrhage and placental abruption, were not significantly different in over 32,000 women randomly assigned to receive aspirin versus placebo (19).

Calcium has also been tested for the prevention of preeclampsia. A systematic review of 13 randomized trials that included over 15,000 women concluded that supplementation with 1-2 g calcium carbonate starting in the second trimester significantly reduced preeclampsia (RR=0.45, 95%CI=0.31-0.65), and this effect was greater in high-risk women (five trials, 587 women; RR=0.22, 95%CI=0.12-0.42), and in those with low baseline calcium intake (eight trials, 10,678 women; RR=0.36, 95%CI=0.20-0.65) (22). No side effects of calcium supplementation were reported in the 13 trials included in the review.

Despite some controversial findings, the existing evidence indicates that supplementing high-risk women with low-dose aspirin and calcium can potentially reduce their risk of developing preeclampsia. In 2011, the World Health Organization (23) recognized calcium and aspirin supplementation during pregnancy as effective interventions to prevent preeclampsia and to reduce maternal mortality. However, major questions remain unanswered, such as which specific subgroups of women are more likely to benefit from this prophylactic medication, what is the best gestational age to start this preventive treatment, and what is the ideal dose of the supplements (23,24). Additionally, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have analyzed the effects of the combined administration of these two supplements on the rate of preeclampsia in high-risk women.

Thus, the main objective of this pilot study was to test the hypothesis that the administration of a combination of low-dose aspirin and calcium would reduce the risk of superimposed preeclampsia in women at high risk for this condition due to chronic hypertension and abnormal uterine artery Doppler in the second trimester. Secondary outcomes of interest in this population were reduction in the rate of fetal growth restriction and preterm delivery.

Material and Methods

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study took place at the antenatal clinic for hypertensive disorders of a large, tertiary, university hospital located in the southern region of the city of São Paulo, SP, Brazil. This clinic offers free antenatal care to low-income women. Throughout the study period, the same team of physicians and nurses cared for all the women enrolled in the study. All participants delivered at the university hospital and were followed for 6 weeks post-partum.

All women receiving antenatal care and planning to deliver at the university hospital, and carrying a live, structurally normal, singleton fetus between 20 and 27 weeks of gestation were eligible if they had chronic hypertension and an abnormal uterine Doppler exam. Chronic hypertension was defined as known history of pre-existing hypertension prior to pregnancy, or blood pressure readings ≥140 systolic and/or ≥90 mmHg diastolic on two occasions over 6 h apart before week 20 of gestation (2). Gestational age was ascertained by menstrual dates confirmed by obstetric ultrasound prior to 20 weeks. In case of discrepancies greater than 8 days, sonographic gestational age was used. Doppler ultrasound screening of uterine arteries is routinely performed at this antenatal clinic in all hypertensive women at 20 to 27 weeks. The first author performed all Doppler exams using a Diasonics Synergy Color Doppler ultrasonography unit (OEC Diasonics, USA) with a 3.5-MHz transducer. Uterine arteries were identified through the transabdominal route using color Doppler. The filter was kept at 50-100 Hz, the angle of insonation was less than 60° and a 3-mm caliper was placed in the lumen of the vessels. Women with a high-resistance index (>0.55) and/or a protodiastolic notch in the placental side or in both uterine arteries were diagnosed as having abnormal uterine Doppler (25) and were eligible to enter the study. Women were ineligible to participate in the study if they had increased risk of bleeding due to coagulation disorders or placenta previa, asthma, allergy to aspirin, already been diagnosed with preeclampsia before 28 weeks of gestation, or were planning to deliver in other hospitals.

A single private laboratory (Farmácia de Manipulação Amarylis, Brazil) provided all the study medications (pills containing either 100 mg aspirin or microcrystalline cellulose and 3×5-cm transparent plastic envelopes containing 2 g elemental calcium in the form of calcium carbonate powder, or cellulose). Placebo pills and powder were matched to the study supplements for taste, color and size.

Randomization was carried out using a list of computer-generated random numbers provided by the Brazilian Cochrane Centre. Packets containing identical looking supplements or placebo (pills and envelopes containing a powder) were placed in individual, consecutively numbered boxes by staff of the Cochrane Centre. Each box contained either supplements or placebo following the sequence generated by the randomization list. Included participants were given the next consecutive prepacked, numbered box in the order of enrollment. The study participants and the medical team caring for them were blinded as to the contents of the boxes.

Upon enrollment, each woman received a box with 140 identical looking oblong white pills (containing either 100 mg aspirin or cellulose) and 140 plastic envelopes (containing either 2 g calcium or cellulose). They were asked to keep the box at room temperature away from direct sunlight and instructed to swallow one pill and dissolve one envelope of the powder in a glass of water daily, in the morning, approximately 2 h after breakfast.

All participants were specifically instructed not to take any aspirin or calcium supplements until delivery. A prescription for acetominophen was given to all participants to be taken in case of pain. At each follow-up visit until delivery, patients were questioned about the use of any medication since their last visit and the study instructions were repeated. Women were asked to return the medication boxes on their first post-partum visit including the remaining unused pills and envelopes, which were then counted. Adherence was classified as poor when the participant had taken less than 50% of the prescribed daily medication prior to delivery, regular for those taking 50-69% of the medication, and good for those taking 70% or more.

The main outcome was superimposed preeclampsia, defined by a) new-onset proteinuria (>300 mg/24 h) after the 20th week of pregnancy in a woman with pre-existing hypertension without proteinuria or b) the sudden increase in proteinuria, blood pressure, or platelet count <100,000/mm3, in women with pre-existing hypertension and proteinuria before 20 weeks of gestation (1). Secondary outcomes were preterm delivery (before 37 weeks) and fetal growth restriction, defined as birth weight below the third centile for gender and estimated gestational age, as described by Yudkin et al. (26). Gestational age at delivery was estimated as previously described, by menstrual dates confirmed through sonogram prior to 20 weeks of gestation. The investigators collected data on outcomes of interest directly from patient charts during pregnancy and after delivery.

To calculate sample size, the records of all women with chronic hypertension who received antenatal care in the clinic in the past 5 years were reviewed and those with abnormal second-trimester uterine artery Doppler were selected. The incidence of superimposed preeclampsia in this group was over 50%. Based on an expected rate of superimposed preeclampsia of 55% in the participants, and an estimated reduction of approximately 50% in this incidence in the group receiving aspirin plus calcium, with an alpha of 5% and a power of 80%, a total of 22 women would have to be randomly assigned to each group.

The two-sample test for equality of proportions, the chi-square test or the Fisher exact test, the independent-samples t-test, and the Mann-Whitney test were used to compare the outcomes in the placebo and study groups. P<0.05 was considered to be significant. All analyses were conducted according to intention to treat. The Ethics Committee of Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP) approved the study, and all participants gave written informed consent upon enrollment.

Results

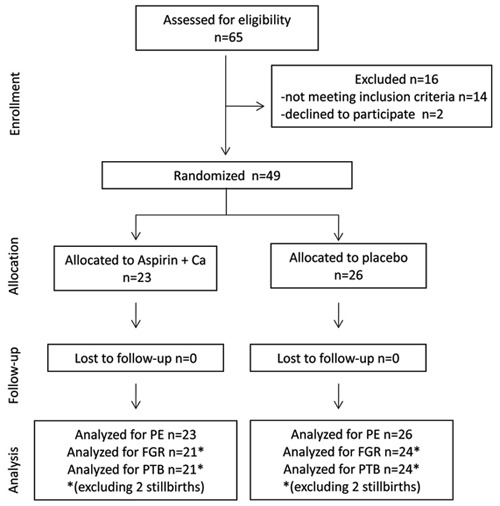

A total of 65 women with chronic hypertension and abnormal uterine artery Doppler were receiving antenatal care at the clinic during the study period; 14 did not meet the selection criteria, 2 refused to participate, and 49 were randomly assigned - 26 to the placebo group and 23 to the treatment group. There were no losses of follow-up, all women continued antenatal care, and were delivered at the study hospital. Analyses of the main outcome (superimposed preeclampsia) were performed on the 23 treated patients and the 26 women who received placebo supplements. There were four stillbirths; two in the placebo group at 20 and 27 weeks (both due to severe fetal growth restriction), and two in the treated group at 28 and 37 weeks (both due to placental abruption). These four cases were excluded from the analyses on fetal growth restriction and preterm delivery but were included in the preeclampsia analyses (Figure 1). None of the participants had eclampsia. There were no adverse events, side effects or complications that could be attributed to supplementation.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the randomized trial on supplementation with aspirin plus calcium for preventing superimposed preeclampsia in high-risk women at 20-27 weeks gestation, in São Paulo, Brazil. Ca: calcium; FGR: fetal growth restriction; PE: preeclampsia; PTB: preterm birth.

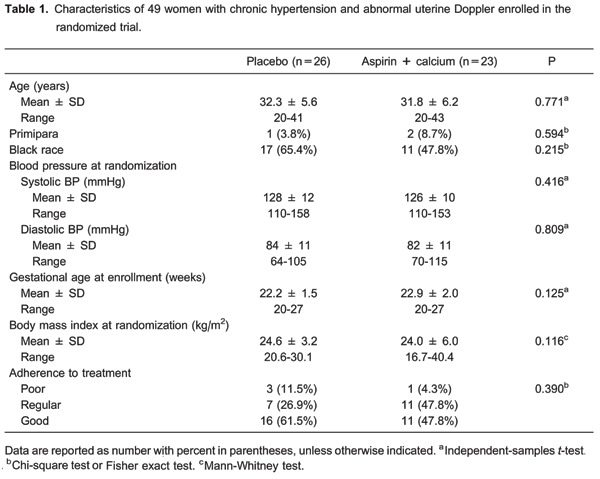

There were no significant differences in the two groups as to age, parity, race, body mass index, and blood pressure at randomization (Table 1). Adherence to prescribed treatment did not differ significantly between groups; the vast majority of women took over half of the prescribed medication (88.4 and 95.6% for the placebo and treatment groups, respectively).

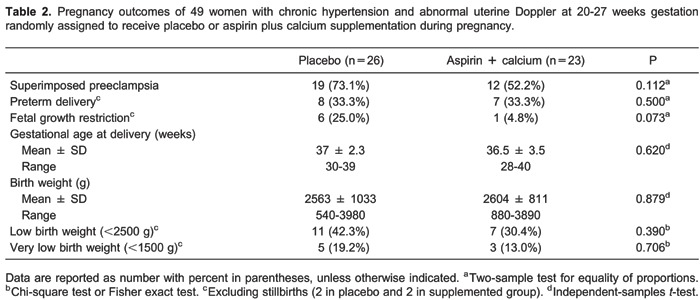

The rate of superimposed preeclampsia was 28.6% lower among women receiving aspirin plus calcium than in the placebo group (52.2 vs 73.1%, respectively), but this difference did not reach statistical significance (P=0.112). Women receiving aspirin plus calcium also had nonsignificant reductions in the rates of low and very low birth weight infants and slightly heavier infants. There was an 80.8% reduction in the rate of fetal growth restriction in the supplemented group (4.8 vs 25%), but this difference fell short of statistical significance (P=0.073). One third of the live births in both groups were delivered before 37 weeks (Table 2).

Discussion

As expected, there was a very high rate of superimposed preeclampsia in this selected group of high-risk women, with over 50% of all participants developing this complication. This led to a large number of growth-restricted infants and elective preterm deliveries. Supplementation with 100 mg aspirin plus 2 g calcium starting after 20 weeks of pregnancy reduced the rate of superimposed preeclampsia by 28.6% and the rate of fetal growth restriction by 80.8% in these women with chronic hypertension and abnormal second-trimester uterine artery Doppler. However, these reductions fell short of statistical difference. The supplements did not have an effect on the rate of preterm delivery.

We cannot compare our findings to others since this is the first study to test this combination of supplements in the prevention of preeclampsia. Although we observed beneficial effects in the supplemented group, the size of this effect fell short of our prediction, which was a 50% reduction in the rate of superimposed preeclampsia. A possible factor for this smaller effect could be the relatively late initiation of low-dose aspirin therapy, at a mean of 22-23 weeks gestation. As previously described, low-dose aspirin before week 16 is more effective in preventing preeclampsia (27). However, as in most developing countries, many high-risk women in our setting book late for antenatal care. Another possible explanation for the smaller than expected effect of combined supplementation could be an interaction between aspirin and calcium that reduced the bioavailability of each substance. This hypothesis cannot be confirmed or refuted because we did not assess the plasma concentration of calcium or aspirin in the participants. Pharmacological aspects of calcium administration could also have played a role in the lower than expected effects of the supplements. The bioavailability of calcium depends on the type of salt used, the daily dose, and whether the supplements are ingested with food. Calcium citrate malate has a higher bioavailability than other forms and has a good absorption even when consumed on an empty stomach. However, large doses (>500 mg/day) of this salt are less well absorbed than lower doses (28).

The etiology and physiopathology of preeclampsia are not yet completely understood. Preeclampsia is a complex disorder caused by nutritional, environmental and genetic factors that lead to an inflammatory state, activation of platelets, imbalance in the production and activity of thromboxane-prostacyclin and of the free radicals nitric oxide, superoxide and peroxynitrate by the vascular endothelium (29). The probable mechanism of action of low-dose aspirin in the prevention of preeclampsia is by inhibiting the excessive production of thromboxane by platelets in women who are susceptible to this disorder (13,14,19,20). Low calcium intake may cause high blood pressure by stimulating the release of parathyroid hormone or renin, thus leading to increased intracellular calcium in vascular smooth muscle (30) and consequent vasoconstriction. A possible mode of action for calcium supplementation is that it reduces parathyroid hormone release and intracellular calcium, and so reduces smooth muscle contractility (22). The explanation of the potential benefits of offering both aspirin and calcium to women at high risk for preeclampsia is at present hypothetical and possibly related to reduction in inflammatory factors and oxidative stress. A recent trial involving a small group of Iranian women at risk for preeclampsia reported that supplementation of low-dose calcium (500 mg) plus 80 mg aspirin for 9 weeks during the third trimester of pregnancy resulted in increased plasma levels of glutathione, total oxidant capacity, and significantly lower change in high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in the intervention group (31).

Our study had several strengths, including its originality, rigorous care to avoid bias in all phases including selection, randomization, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and physicians, and reporting of outcomes.

A potential limitation of our study was the lack of information on the baseline ingestion of dietary calcium in both groups. However, since the participants were from the same geographic setting and had similar socioeconomic characteristics, we can infer that the eating habits of these women were probably very similar. According to the latest national food inquiry survey, the mean dietary calcium intake of adult Brazilian women is less than 500 mg/day and over 90% do not reach the recommended dietary calcium intake for their age (32). Only a few studies with small sample sizes have assessed the ingestion of calcium by Brazilian pregnant women, and they focused on specific subgroups such as overweight participants and adolescents. According to those studies, mean daily calcium intake was below the recommended 1200 mg/day and ranged from 586.6 to 842.9 mg/day in those specific populations of pregnant women (33-35). The importance of baseline dietary calcium has been previously demonstrated in large randomized trials of calcium supplementation for the prevention of preeclampsia (36,37). In those studies, women with a high dietary ingestion of calcium (>1200 mg/day) had no significant reduction in the rate of preeclampsia, but those with lower dietary calcium seemed to benefit from supplementation.

Although this study had a relatively small sample size, all participants were women with essential chronic hypertension and abnormal uterine Doppler findings, which is not the case in the majority of published studies. The sample size calculation was based on an expected rate of superimposed preeclampsia of 55% in this very high-risk group of women and an estimated reduction of 50% in the group treated with aspirin plus calcium. There have been no previous studies to provide guidance on the expected effects of this combination of drugs. The first part of this estimation was based on clinical records of previous patients and it was correct. The incidence of superimposed preeclampsia was 73.1% in the placebo group. However, the effect of the supplements was overestimated. The treated group had an incidence of superimposed preeclampsia of 52.2%, which corresponds to a reduction of 28.6%, instead of 50%. Therefore, for this difference to be statistically significant, it would have been necessary to include approximately 82 participants in each group, instead of 22 women. Nevertheless, the results of this pilot study are valuable for future investigations on the use of combined supplements for the prevention of preeclampsia in high-risk women.

This is the first study to assess the effects of the combined supplementation of calcium plus low-dose aspirin on the prevention of preeclampsia in women at high risk for this complication. Our results need to be confirmed by other studies involving a larger number of high-risk participants. Besides larger sample sizes, future studies could test the introduction of combined supplementation at an earlier gestational age (i.e., between 16-20 weeks), determine the dietary calcium ingestion of the participants (e.g., through a food questionnaire), and perform bioavailability studies to ascertain the actual absorption of aspirin and calcium.

According to the findings of this pilot study, the combined supplementation of aspirin and calcium starting at 20-27 weeks of gestation produced a nonsignificant decrease in the incidence of superimposed preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction in hypertensive women with abnormal uterine artery Doppler findings.

Footnotes

First published online April 4, 2014.

References

- 1.Khan KS, Wojdyla D, Say L, Gulmezoglu AM, Van Look PF. WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: a systematic review. Lancet. 2006;367:1066–1074. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68397-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Report of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:S1–S22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chappell LC, Enye S, Seed P, Briley AL, Poston L, Shennan AH. Adverse perinatal outcomes and risk factors for preeclampsia in women with chronic hypertension: a prospective study. Hypertension. 2008;51:1002–1009. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.107565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giannubilo SR, Dell'Uomo B, Tranquilli AL. Perinatal outcomes, blood pressure patterns and risk assessment of superimposed preeclampsia in mild chronic hypertensive pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006;126:63–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCowan LM, Buist RG, North RA, Gamble G. Perinatal morbidity in chronic hypertension. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;103:123–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1996.tb09662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sibai BM, Lindheimer M, Hauth J, Caritis S, VanDorsten P, Klebanoff M, et al. Risk factors for preeclampsia, abruptio placentae, and adverse neonatal outcomes among women with chronic hypertension. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:667–671. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809033391004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rey E, Couturier A. The prognosis of pregnancy in women with chronic hypertension. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:410–416. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(94)90276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lecarpentier E, Tsatsaris V, Goffinet F, Cabrol D, Sibai B, Haddad B. Risk factors of superimposed preeclampsia in women with essential chronic hypertension treated before pregnancy. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62140. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilbert WM, Young AL, Danielsen B. Pregnancy outcomes in women with chronic hypertension: a population-based study. J Reprod Med. 2007;52:1046–1051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 125: Chronic hypertension in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:396–407. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318249ff06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henrique AJ, Borrozzino NF, Gabrielloni MC, Barbieri M, Schirmer J. [Perinatal outcome in women suffering from chronic hypertension: literature integrative review] Rev Bras Enferm. 2012;65:1000–1010. doi: 10.1590/S0034-71672012000600017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papageorghiou AT, Yu CK, Cicero S, Bower S, Nicolaides KH. Second-trimester uterine artery Doppler screening in unselected populations: a review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002;12:78–88. doi: 10.1080/jmf.12.2.78.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beaufils M, Uzan S, Donsimoni R, Colau JC. Prevention of pre-eclampsia by early antiplatelet therapy. Lancet. 1985;1:840–842. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(85)92207-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wallenburg HC, Dekker GA, Makovitz JW, Rotmans P. Low-dose aspirin prevents pregnancy-induced hypertension and pre-eclampsia in angiotensin-sensitive primigravidae. Lancet. 1986;1:1–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)91891-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.CLASP: a randomised trial of low-dose aspirin for the prevention and treatment of pre-eclampsia among 9364 pregnant women. CLASP (Collaborative Low-dose Aspirin Study in Pregnancy) Collaborative Group. Lancet. 1994;343:619–629. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(94)92633-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ECPPA: randomised trial of low dose aspirin for the prevention of maternal and fetal complications in high risk pregnant women. ECPPA (Estudo Colaborativo para Prevenção da Pre-eclâmpsia com Aspirina) Collaborative Group. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;103:39–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1996.tb09513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sibai BM, Caritis SN, Thom E, Klebanoff M, McNellis D, Rocco L, et al. Prevention of preeclampsia with low-dose aspirin in healthy, nulliparous pregnant women. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1213–1218. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199310213291701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caritis S, Sibai B, Hauth J, Lindheimer MD, Klebanoff M, Thom E, et al. Low-dose aspirin to prevent preeclampsia in women at high risk. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:701–705. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803123381101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Askie LM, Duley L, Henderson-Smart DJ, Stewart LA. Antiplatelet agents for prevention of pre-eclampsia: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet. 2007;369:1791–1798. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60712-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coomarasamy A, Papaioannou S, Gee H, Khan KS. Aspirin for the prevention of preeclampsia in women with abnormal uterine artery Doppler: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:861–866. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(01)01569-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu CK, Papageorghiou AT, Parra M, Palma DR, Nicolaides KH. Randomized controlled trial using low-dose aspirin in the prevention of pre-eclampsia in women with abnormal uterine artery Doppler at 23 weeks' gestation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;22:233–239. doi: 10.1002/uog.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hofmeyr GJ, Lawrie TA, Atallah AN, Duley L. Calcium supplementation during pregnancy for preventing hypertensive disorders and related problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010: doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001059.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations for prevention and treatment of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241548335_eng.pdf [PubMed]

- 24.Dekker G, Sibai B. Primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention of pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2001;357:209–215. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03599-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCowan LM, Ritchie K, Mo LY, Bascom PA, Sherret H. Uterine artery flow velocity waveforms in normal and growth-retarded pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158:499–504. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(88)90013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yudkin PL, Aboualfa M, Eyre JA, Redman CW, Wilkinson AR. New birthweight and head circumference centiles for gestational ages 24 to 42 weeks. Early Hum Dev. 1987;15:45–52. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(87)90099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bujold E, Roberge S, Lacasse Y, Bureau M, Audibert F, Marcoux S, et al. Prevention of preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction with aspirin started in early pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:402–414. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e9322a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reinwald S, Weaver CM, Kester JJ. The health benefits of calcium citrate malate: a review of the supporting science. Adv Food Nutr Res. 2008;54:219–346. doi: 10.1016/S1043-4526(07)00006-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lopez-Jaramillo P, Casas JP, Serrano N. Preeclampsia: from epidemiological observations to molecular mechanisms. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2001;34:1227–1235. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2001001000001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Belizan JM, Villar J, Repke J. The relationship between calcium intake and pregnancy-induced hypertension: up-to-date evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158:898–902. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(88)90091-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asemi Z, Samimi M, Heidarzadeh Z, Khorrammian H, Tabassi Z. A randomized controlled clinical trial investigating the effect of calcium supplement plus low-dose aspirin on hs-CRP, oxidative stress and insulin resistance in pregnant women at risk for pre-eclampsia. Pak J Biol Sci. 2012;15:469–476. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2012.469.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística - IBGE. Pesquisa de orçamentos familiares 2008-2009: Análise do consumo alimentar pessoal no Brasil. http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/condicaodevida/pof/2008_2009_analise_consumo/pofanalise_2008_2009.pdf

- 33.Azevedo DV, Sampaio HAC. [Food consumption of pregnant adolescents assisted by prenatal service] Rev Nutr Campinas. 2003;16:273–280. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fazio ES, Nomura RM, Dias MC, Zugaib M. [Dietary intake of pregnant women and maternal weight gain after nutritional counseling] Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2011;33:87–92. doi: 10.1590/S0100-72032011000200006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nascimento E, Souza SB. [Evalutation of diet of overweight pregnant women] Rev Nutr Campinas. 2002;15:173–179. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levine RJ, Hauth JC, Curet LB, Sibai BM, Catalano PM, Morris CD, et al. Trial of calcium to prevent preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:69–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199707103370201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Villar J, Abdel-Aleem H, Merialdi M, Mathai M, Ali MM, Zavaleta N, et al. World Health Organization randomized trial of calcium supplementation among low calcium intake pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:639–649. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.01.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]