Abstract

Background

Engineered heart tissue (EHT) is being developed for clinical implantation in heart failure or congenital heart disease. The validity of the approach depends on the comprehensive functional characterization of EHT. Here we optimized the effects of modulating cell composition in self-organizing EHT and present detailed electrophysiological and contractile functional characterization.

Methods

EHT fibers with different cell densities (0.5×106 - 3×106) were generated from neonatal rat cardiac cells on a fibrin hydrogel scaffold. We measured contractile function using a force transducer and assessed force-length relationship, maximal force generation and rate of force generation (dF/dt). Using optical mapping with voltage sensitive dye, we assessed EHT fiber action potential (AP) and conduction velocity (CV) while transcript levels of myosin heavy chain beta (MyHβ) was measured by RT-PCR.

Results

We found a clear force-length relationship that was negatively impacted by increasing cell density. Maximal force generation and dF/dt were also significantly decreased with increasing cell densities. This decrease was not due to a selective expansion of non-contractile cells as MyHβ levels at endpoint reflected initial seeding density. EHT fibers with optimal cell density had an AP duration of 140.2 ms and a CV of 23.2 cm/s.

Conclusion

EHT display physiologically relevant features shared with native myocardium. Higher cell densities abrogate EHT contractile function, possibly due to sub-optimal cardiomyocyte performance in the absence of a functional vasculature. Finally, CV approaches that of native myocardium without any electrical or mechanical conditioning, suggesting that the self-organizing method may be superior to other rigid scaffold based EHT.

Keywords: Bioengineering, Cell biology/culture/engineering, In vitro studies, Tissue engineering

Introduction

Tissue engineering is an attractive alternative to current treatment for a wide range of congenital and acquired heart disease in which replacement or remodeling of the diseased or deficient tissue is required. In vitro engineered heart tissue (EHT), has been developed by a number of groups using various strategies and has the potential to replace diseased native myocardial tissue in end-stage heart disease or augment deficient areas in congenital heart defects (Reviewed in [1]). Furthermore, EHT has been used as models for heart development and pharmacological assays. We and others have also used EHT to evaluate various stem cells as potential cardiac regenerative therapies [2].

The utility of EHT as a model for heart development and pharmacological assays and for clinical applications depends on its close correlation to native tissue. Basic properties of myocardial tissue such as force (F) generation, force-length relationship, force-frequency relationship, rate of force generation (dF/dtsys) and relaxation (dF/dtdia) have traditionally been obtained using isolated native myocardial tissue from both animals and humans in vitro [3]. However, isolated tissue, either in the form of papillary, trabeculae or pectinate muscles demonstrate infrequent (low frequency) spontaneous contractions that are thought to originate from Ca2+ oscillations from the sarcoplasmic reticulum and membrane damage [4,5]. These native tissue preparations therefore require electrical field pacing to elicit coordinated global and simultaneous contractile activity once isolated and evaluated in vitro [6]. Moreover, native tissue is poorly suited for clinical applications of regenerative medicine.

There have been several fundamental muscle dynamics studies of electrically paced EHT. Asnes et al determined the force-length relationship of EHT made from chicken embryo cardiomyocytes (CMs) under varying conditions [7] and both Eschenhagen and colleagues [8] and Birla and colleagues [9] have explored individual aspects of normal cardiac function in similar model system. However there has been no comprehensive assessment of EHT function and none have studied EHT during spontaneous contractile activity.

We utilize an EHT model that both possess spontaneous contractile activity and may also be electrically paced [2,9]. This spontaneous electromechanical activity allows us to explore fundamental properties of EHT without the need for electrical stimulation. The purpose of this study was therefore to perform a detailed functional characterization of spontaneously contracting EHT, including determination of relevant molecular and cellular parameters.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All procedures involving laboratory animals were done in accordance with protocols approved by the UC Davis Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Isolation of neonatal rat cardiac cells

Cells were isolated from neonatal Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) 2-4 days of age as described previously [2]. Briefly, hearts were placed in cardioplegic buffer (116 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES, 1 mM Na2HPO4, 5.5 mM glucose, 5.4 mM KCl, and 0.8 mM MgSO4), minced and suspended in cardioplegic buffer containing 0.32 mg/ml collagenase type II (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 0.6 mg/ml pancreatin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Enzymatic dissociation was done under gentle agitation for 20 min at 37°C. The supernatant containing liberated cells was then removed and replaced with fresh dissociation buffer for further rounds of dissociation. Supernatants containing dissociated cells from a total of three rounds of digestion were pooled, centrifuged and then suspended in plating medium (PM) consisting of 64% (v/v) M199, 20% F12K, 7% fetal bovine serum, 7% calf bovine serum, 1% penicillin-streptomycin (all Invitrogen), 40 ng/ml hydrocortisone, 25 μg/ml 6-aminocaproic acid, and 30 μg/ml ascorbic acid (all Sigma-Aldrich).

Plating

Cardiac cells were plated as described [2]. Briefly, 35 mm culture dishes were coated with polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) elastomer (Dow Chemical Corporation, Pittsburgh, CA) and six-mm-long segments of 0-0 silk sutures (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) that served as anchors for the EHT fiber were pinned 8 mm apart in the center of the culture plate unless specified otherwise. Thrombin (10U/ml) and fibrinogen (20 mg/ml, both Sigma-Aldrich) diluted in PM were mixed and layered on top of the PDMS to form a fibrin gel layer. Isolated cardiac cells re-suspended in PM were layered on top of the fibrin gel at varying densities, ranging from 0.5 to 3×106 cells/plate as indicated. n=6 plates per group unless specified otherwise. Plates were incubated in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C, 5% CO2 and media (PM) was changed every other day.

Force measurements

EHT contractile function was measured using a custom-built optical force transducer (R. Dennis, UNC). Briefly, EHT fibers in PM were maintained at 37°C on a heating plate and one end of the fiber was unpinned from the PDMS coating and attached to the force transducer load element. The force transducer was mounted on an optical board via an XYZ linear stage with a single dimension manual micrometer control in the dimension parallel to the long axis of the fiber (Newport, Irvine, CA). This allowed for preload adjustment by means of controlling the displacement, d, of the optical force transducer. Preload was increased in a stepwise manner from d=0 mm (slack length where F=0μN) to d=8mm and data was recorded for up to 30 sec at each displacement. Data was digitally recorded using LabVIEW (National Instruments Corporation, Austin, TX). In addition, high resolution images calibrated to the cell culture plate grid were used to estimate the fiber width averaged over three different positions along the fiber length and the average fiber cross sectional area was calculated. The analysis of force measurements was performed using a custom-written Python (ver. 2.6.6) script utilizing the Numpy (ver. 1.5.0b1), SciPy (ver. 0.8.0), and Matplotlib (ver. 1.0.1rc1) libraries.

RT-PCR

Total mRNA was isolated from whole fibers using RNA Stat-60 (Tel-Test, Friendswood, TX) and cDNA was generated using Taqman Reverse Transcriptase according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad CA). Real time PCR was done using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Applied Biosystems) and the following primers: Cardiac myosin heavy chain beta – forward: GGAGACCTTCAAGCGGGAGA, reverse: AGGGCTGACTGCAGCTCCA; Hypoxia inducible factor 1 – forward: TGCTTGGTGCTGATTTGTGA, reverse: GGTCAGATGATCAGAGTCCA; GAPDH – forward: TCCTGCACCACCAACTGCTTAG, reverse: AGTGGCAGTGATGGCATGGACT. The ΔΔCT method was used to quantify fold difference in gene expression using GAPDH as internal control. Primer specificity and efficiency was verified for all primers. All samples were run in triplicate. Results were pooled from experimental replicates when appropriate.

Optical mapping of transmembrane potential (Vm)

Fibers were superfused with warm (37 ± 1°C), oxygenated (95% O2, 5% CO2) Tyrode's solution of the following composition (in mM): NaCl 128.2, CaCl2 1.3, KCl 4.7, MgCl2 1.05, NaH2PO4 1.19, NaHCO3 20 and glucose 11.1 (pH 7.4 ± 0.05). After 15 min of equilibration, fibers were stained with the voltage-sensitive dye di-4-ANEPPS (2 μM, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). The excitation-contraction uncoupler Blebbistatin (BB, 10-15 μM, Tocris Bioscience) was added to the perfusate to eliminate motion artifacts in the optical recordings caused by fiber contraction. Excitation light was generated using LED light sources centered at 530nm (LEX-2, SciMedia, Costa Mesa, CA) and bandpass filtered through 531±20 nm excitation filters before being focused directly onto the preparation. Emitted light was collected through a longpass filter (650 nm) by a 50 mm objective (Nikon, Japan) and acquired by a MiCAM Ultima-L CMOS camera (SciMedia, Costa Mesa, CA) at 1 kHz. The spatial resolution of the camera was 100 × 100 pixels and the optical field of view was 10 × 10 mm2. Following staining with di-4-ANEPPS, baseline recordings were acquired to assure adequate signal-to-noise ratios. A bipolar pacing electrode was then placed near one end of the fiber to obtain proper viewing of Vm propagation. Optical recordings were acquired at a basic cycle length (BCL) of 200 ms (300 beats per minute). Standard analysis techniques were performed on the optical Vm data using custom software packages (SciMedia, Costa Mesa, CA, Optiq, Cairn, UK). Activation times were determined as the 50% rise time (baseline to peak). Repolarization time at 90% of return to baseline amplitude was used to calculate action potential duration (APD90). Isochronal maps of activation were constructed with isochrones every 3 ms. Conduction velocity (CV) was calculated in the direction normal to wave-front propagation.

Statistics

Mean values ± SD are depicted and between groups comparisons were done using ANOVA with Holm-Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Confidence Intervals (CI) of the mean are given with an α of 0.05. A p ≤ 0.05 was taken to be significant.

Results

Force-frequency relationship

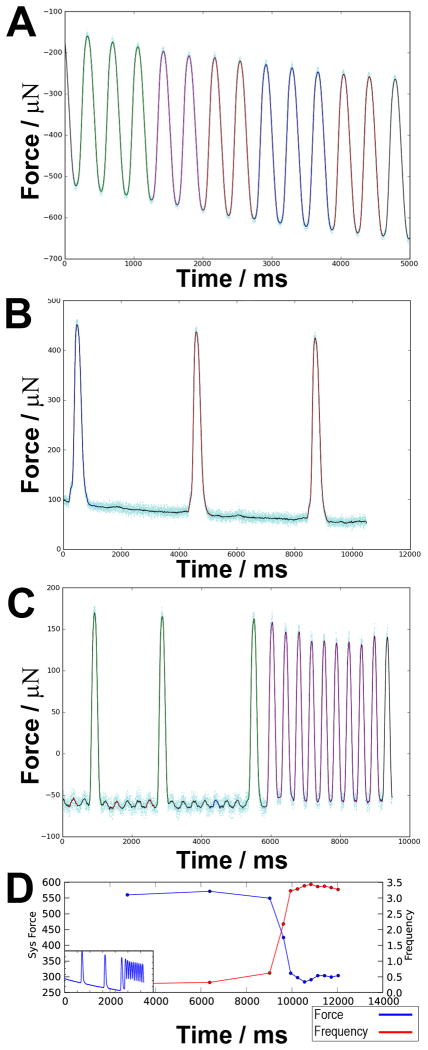

Force tracings from spontaneously contracting fibers differed significantly depending both on the plating density and the frequency (1, 2 or 3×106 cardiac cells per group in Group 1, 2, and 3, respectively, Figure 1A-C): type 1 had a high frequency of contractions (>1Hz) with no delay between individual contraction (Figure 1A); type 2 had sporadic contractions with long resting periods between individual contractions (<1Hz, Figure 1B); type 3 had a combination of high frequency contractions and sporadic contractions (Figure 1C). We noted a difference in amplitude of the force generated by the high and low frequency contractions as indicated in Figure 1C. In order to more accurately describe this relationship, we generated force-frequency plots for all the fibers at a preload corresponding to a displacement of 2.5mm over the slack length (Figure 1D). For each fiber we determined the best linear fit for the force-frequency data and used the sign of the alphas to determine the nature of the relationship for each group. Overall, we observed a negative force-frequency relationship for all three groups with the most pronounced effect seen in Group 1 (Figure 1D). The negative force frequency relationship was observed both for fibers contracting over a narrow frequency range (type 1 fibers) and for fibers with mixed contraction patterns (type 3 fibers).

Figure 1. Typical contraction patterns and force/frequency plots.

(A) Type 1 fiber showing consistent and high frequency contraction pattern, (B) Type 2 fiber with sporadic, low frequent contraction pattern, (C) Type 3 fiber with mixed Type1/2 contraction pattern, (D) Force (blue line)/frequency (red line) plot from a representative type 3 fiber (insert). Note that scaling on panels A-C are derived from raw data-output and are not normalized between panels.

Force-length relationship

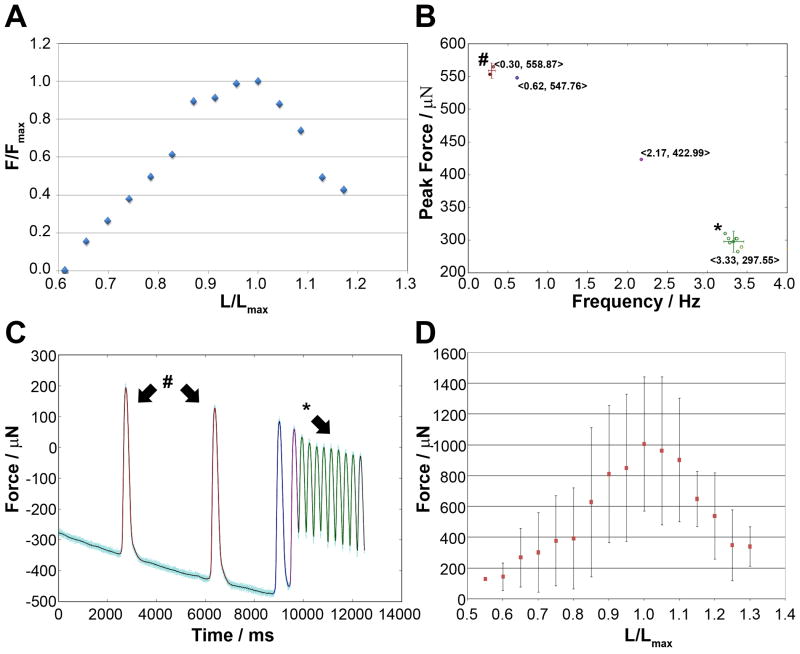

Next, we wanted to verify that the EHT fibers retained a Frank-Starling like force-length relationship similar to native myocardium which, in turn, would allow us to determine the peak force generation (F=Fmax). For each fiber we therefore measured spontaneous force generation under conditions of increasing preload by increasing fiber displacement in 0.5mm stepwise increments. From each fiber we thus obtained force tracings at extensions ranging from 0.5mm to 8.0mm over slack length (Figure 2A). In order to account for the differences in force production depending on frequency, as described above, we analyzed data (1) acquired only during periods of high frequency (HF) contraction (type 1 and 2 fibers) or, alternatively, (2) by identifying the maximal force (MF) generated within a given force tracing irrespective of local frequency (contractions labeled with # in Figure 2B-C).

Figure 2. Force-length relationship in EHT fibers.

(A) Representative plot of a force-length relationship from a fiber plated at an initial 3×106 cells density. (B) Cluster plot and force tracing (C) of a representative type 3 contraction pattern with indications of high (*) and low (#) frequency clusters. Numbers in <> indicate mean force and frequency of the corresponding cluster. (D) Representative mean force-length plot for a group of fibers plated at 106 cells per plate. Error-bars indicate SD and n=6 fibers.

Our analysis of high frequency data sets utilized a cluster analysis of the total recorded contractions as a function of contraction frequency (Figure 2B). From the cluster plots we determined the mean F of the most prominent high frequency contraction cluster (type 3 fibers) or the average of the entire dataset irrespective of clustering for type 1 fibers (Figure 2B-C). Force recordings that did not contain any high frequency (>1Hz) contraction patterns were excluded from the analysis (type 2 fibers). Excluding type 2 fibers, however, precluded the generation of meaningful force/length curve due to insufficient data points and we did not further evaluate data in this manner. The following data is thus based on MF, which was available from all recordings.

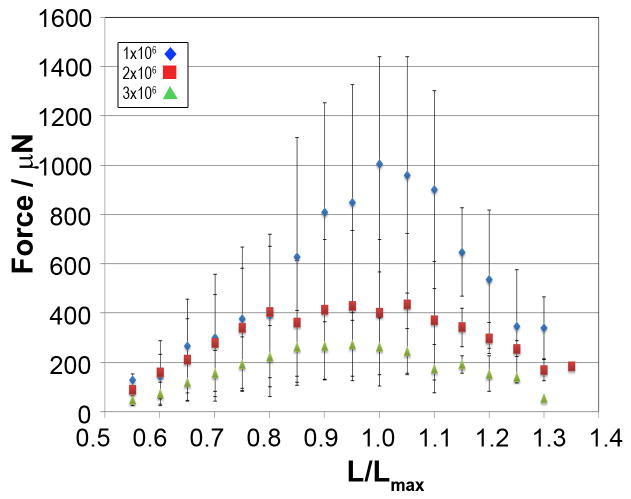

We then calculated force per cross sectional area of each fiber and plotted the resulting specific force against the displacement for each fiber (Figure 2D). From the resulting force-length plots we were able to determine the maximal preload dependent specific force, Fmax, for each fiber and saw a typical Frank-Starling force-length pattern for the majority of the individual fibers (Figure 2D). Within each group, we next calculated the mean specific MF at the individual preloads and derived the mean Fmax and Lmax and corresponding force-length plots for each group (Figure 3 and Table 1). The Lmax at which we observed the mean Fmax was only slightly different between the three groups (5.0, 5.5, and 4.5mm for Groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively, Table 1). The difference in mean Fmax was however highly affected by the plating density with a progressive decline in the mean force over a broad range of preloads spanning L=Lmax with increasing plating densities. The difference in Fmax was statistically significantly different between Group 1 and Group 3, while the difference between Group 1 and Group 2 trended towards significance (Table 1). We also observed a flattening of the force-length curves around the mean Fmax with increasing plating densities (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Force-length relationship is dependent on plating density.

Fibers were plated at 1, 2 or 3×106 cells/fiber (◆, ●, and ▲, respectively) and force was measured at increasing displacements. Mean forces for each group of fibers at all displacements are shown. Error-bars indicate SD and n=6 for all three groups.

Table 1. Maximal force generation in dependent on plating density.

| Group | L at Lmax/cm | Fmax/μN | CI/ μN | p vs. Grp 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| 1 | 5.0 | 1006.28 | 657.25-1355.30 | - |

| 2 | 5.5 | 438.39 | 186.42-690.37 | 0.034708# |

| 3 | 4.5 | 274.71 | 161.03-388.39 | 0.005828* |

: Significant after Holm-Bonferroni correction

:Non-significant after Holm-Bonferroni correction

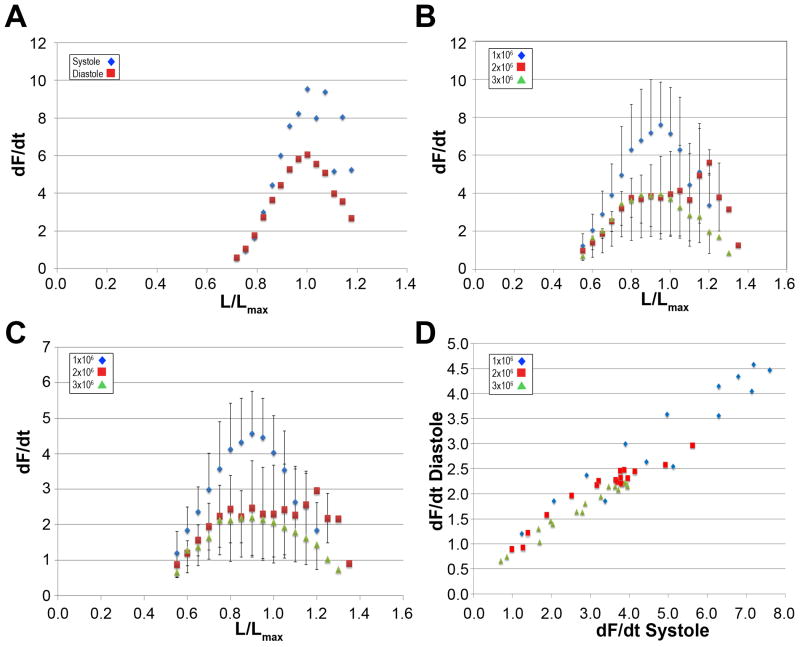

Rate of Force Generation

The rate of force generation with respect to time (dF/dt) during systole and diastole was determined numerically from the force acquisition data. By plotting dF/dt as a function of the preload (L), we could determine the maximal systolic (dF/dtSystole) and diastolic (dF/dtDiastole) velocities for each fiber at all preloads (Figure 4A) and the mean dF/dtSystole and dF/dtDiastole for each group (Figure 4B-C). We found that the both the systolic and diastolic velocities were adversely affected by increasing plating densities in a preload dependent manner (p=0.021 and 0.0121 comparing 1×106 cell/fiber vs. 3×106 cells/fiber in systole and diastole, respectively). Interestingly however, we found that the interdependence of the systolic and diastolic velocities remained relatively constant irrespective of plating densities (Figure 5D, α=0.511, 0.441 and 0.472 for 1, 2 and 3 ×106cells/plate, respectively).

Figure 4. Rate of Force Generation in EHT Fibers.

(A) A representative plot of the rate of force generation (dF/dt) at systole (◆) and diastole (■) at increasing preloads. Mean rate of force generation at systole (B) and diastole (C) at increasing preloads for groups of fibers plated at 1, 2 or 3×106 cells/fiber (◆, ●, and ▲, respectively). (D) Interdependence of mean rate of force generation at systole and diastole at increasing preloads for groups of fibers plated at 1, 2 or 3×106 cells/fiber (◆, ●, and ▲, respectively). Error-bars indicate SD and n=6 for all three groups in panels B-D.

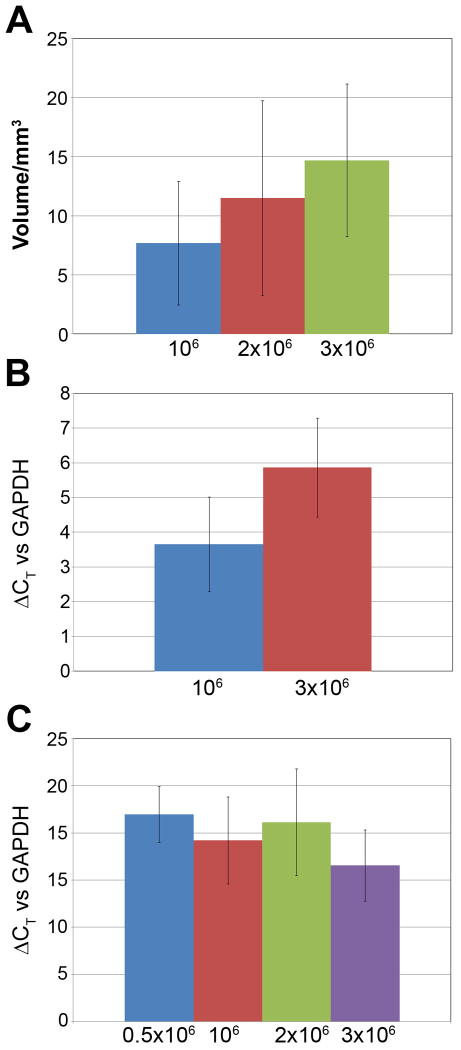

Figure 5. Fiber volume and expression of MyHβ.

(A) The group mean fiber volumes for fibers plated at 1, 2 or 3×106 cells/fiber were calculated from known fiber lengths and average widths measured at three points along the length of each fiber. Error-bars indicate SD and n=6 for all three groups. (B) qPCR targeting MyHβ mRNA isolated from whole fibers was compared between fibers plated at 1 or 3×106 cells/fiber. The ΔΔCT method was used to compare the two plating densities and GAPDH was used as internal control. Error-bars indicate SD, n=7 and 6 for 1×106 and 3×106 cells/fiber respectively.

RT-PCR

We found that the volume of the fiber increased with increasing plating densities. Although the increase in volume failed to reach significance (Figure 5A, 1×106 cell/fiber vs. 3×106 cells/fiber: p=0.066) the clear trend toward increased tissue volume at higher plating densities combined with the unexpected decrease in Fmax indicated a possible selective loss of cardiomyocytes during the compaction phase in the higher plating densities or a suboptimal performance in the larger and more cellular EHT fibers. We therefore evaluated the cardiomyocyte content of the fibers as specified by myosin heavy chain beta (MyHβ) by RT-PCR. Groups of fibers (n=3-4 per group) were plated at densities ranging between 0.5 and 3 ×106 cardiac cells per plate and functional competence of all fibers was verified on the force transducer before total mRNA was isolated. We were able to confirm that the relative cardiomyocyte content was maintained with increasing plating densities over entire range analyzed (Figure 5B). We found that the MyHβ expression was significantly increased at the higher plating densities with an average 2.5 to 5.7 fold increase in mRNA in three separate experiments covering a 3-4 fold increase in plating density (Figure 5B).

Since the decrease in force production was not related to a decrease in MyHβ content at the higher plating densities, we hypothesized that, in the absence of a functional vasculature, the combination of increased cellularity and volume would negatively impact the oxygen supply to the cardiomyocytes. We therefore evaluated the hypoxic stress by comparing expression of Hypoxia Inducible Factor 1α (Hif1α) at the above mentioned plating densities (Figure 5C). In two separate experiments, we noticed no clear change in Hif1α expression relative to plating density with a 0.5-1.1 fold change in mRNA expression in response to a 3-4 fold change in plating density.

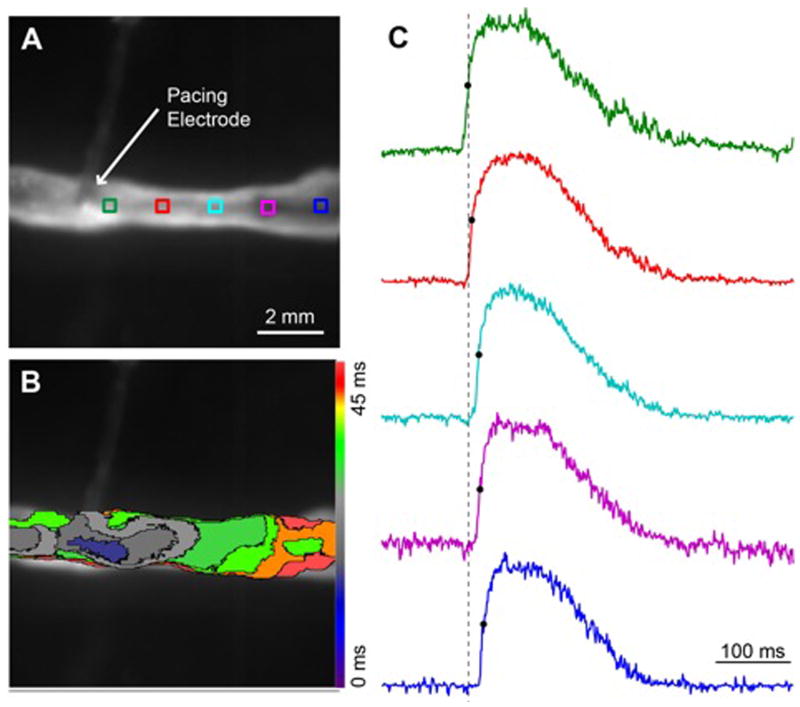

Electrophysiological evaluation

To evaluate the action potential and conduction velocity (CV) characteristics, optical mapping of Vm was performed in fibers plated at 1 ×106 cardiac cells per plate. Figure 6A illustrates the orientation of the fiber in the optical mapping field of view. As it is shown in Figure 6B, when the fiber was stimulated at one end, the activation wavefront quickly propagated to the other end with an average CV of 23.2±3.92 cm/s (n=6). Figure 6C shows individual optical action potentials from different locations along the fiber. At a BCL of 200 ms, the average APD90 was 140.2±12.1 ms (n=6).

Figure 6. Optical mapping of Vm was performed in Group 1 fibers.

Representative illustration of (A) the orientation of the fiber in the optical mapping field of view and (B) the propagation of the activation wavefront. (C) Representative illustration of individual optical action potentials from different locations along the fiber corresponding to similarly colored ROIs in panel A. Average CV = 23.2±3.92 cm/s, average APD90 = 140.2±12.1 ms, n=6.

Comment

Spontaneous contraction of in vitro cultured myocardium has previously been described [4]. Spontaneous contractions observed in isolated myocardial tissue are thought to originate from calcium fluctuations from the sacroplasmic reticulum [4,5]. We found an inverse relationship between force and frequency similar to what has previously been described for native myocardium from small rodents (reviewed in [10]). Furthermore, by gradually increasing the preload, we were able to demonstrate that our EHT observed the Frank-Starling relationship with linear increases and decrease in force generation. By increasing the preload by 0.5mm increments, we were thus able to identify the maximal force attainable by a given fiber and groups of fibers treated in parallel. The steepness of the increase and decrease in force production around the optimal preload has further implications when comparing data from different experiments or different EHT based constructs in that small deviation from the optimal preload in itself may result in large differences in force production irrespective of other experimental interventions.

We were surprised to find that increasing the cell density did not result in an increase but rather a decrease in force production. Although the tissue volume and the relative amount of MyHβ did increase, we demonstrated a significant decrease in maximal force production at the optimal preload when comparing fibers with one million versus three million isolated cardiac cells. Since the EHT here lacked a functional vasculature, we speculate that increasing the plating density results in an EHT construct with a core that no longer can meet its metabolic demand by diffusion. We did however not see any difference in the expression of Hif1-α over a wide range of plating densities or in response to pacing when comparing high and low plating densities which may have been related to the decreased spontaneous contractile activity (data not shown). Further experiments are needed to elucidate this point.

The reduction in force generation at higher plating densities was also accompanied by a similar decrease in the systolic and diastolic velocities. Interestingly, we found that the interdependence of the systolic and diastolic velocities was maintained irrespective of the plating density in accordance with previous reports of native murine heart tissue [11]. Nonetheless, in addition to the possible unfavorable metabolic status of the more cellular EHT fibers, as discussed above, the reduced rate of force generation at higher plating densities may relate to an imbalance in fiber composition at higher cell densities. Cardiomyocytes are more sensitive to the isolation procedure and have a comparatively more limited proliferative potential thereby possibly favoring parenchymal cell proliferation and, consequently, extracellular matrix deposition. This, in turn, may lead to altered mechanical and physiological properties. Although we did not formally test this hypothesis, we did find that the CV measured in the Group 1 fibers was consistent with what has previously been reported for native neonatal cardiac tissue (27 cm/s for 10 day old rats [12]) and was superior to what has previously been reported for unstimulated EHT (8.6 ± 2.3 cm/s [13]). Our measured APD90 was, however, longer than what has previously been reported for native neonatal rat cardiac tissue (43 ms for 10 day old rats [12]). The similarities in the electrophysiological properties of our fibers relative to native neonatal rat heart tissue, however, further highlights the overall close correlation between our in vitro EHT and native cardiac tissue with respect to key mechanical and physiological parameters.

In conclusion, we here show that EHT generated by the self-organization of neonatal rat cardiac cells in a fibrin hydro-scaffold retains major hallmarks of native cardiac tissue. The fact that our spontaneously contracting EHT constructs mirror native tissue with respect to clinically relevant parameters make them ideally suited as platforms for both in vitro drug development and generation of implantable engineered heart tissue. However, the absence of a functional vasculature currently limits the scalability of the tissue constructs beyond the range of passive oxygen diffusion thus necessitating extensive pre-vascularization, which is the object of our continued research efforts [14].

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Children's Miracle Network and the UC Davis Department of Surgery (MSS) and NIH HL101280-01 (CMR). CSS was supported in part by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine.

References

- 1.Si MS, Sondergaard CS, Mathews GM. Cardiac Tissue Engineering. Recent Patents on Regenerative Medicine. 2011;1(3):13. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sondergaard CS, Hodonsky CJ, Khait L, et al. Human thymus mesenchymal stromal cells augment force production in self-organized cardiac tissue. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90(3):796–803. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.04.080. discussion 803-794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foex P. Experimental models of myocardial ischaemia. Br J Anaesth. 1988;61(1):44–55. doi: 10.1093/bja/61.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kimura H, Takemura H, Imoto K, Furukawa K, Ohshika H, Mochizuki Y. Relation between spontaneous contraction and sarcoplasmic reticulum function in cultured neonatal rat cardiac myocytes. Cell Signal. 1998;10(5):349–354. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(97)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kort AA, Lakatta EG. Calcium-dependent mechanical oscillations occur spontaneously in unstimulated mammalian cardiac tissues. Circ Res. 1984;54(4):396–404. doi: 10.1161/01.res.54.4.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kenakin T. Isolated cardiac muscle assays. Curr Protoc Pharmacol Chapter 4: Unit43. 2001 doi: 10.1002/0471141755.ph0403s00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asnes CF, Marquez JP, Elson EL, Wakatsuki T. Reconstitution of the Frank-Starling mechanism in engineered heart tissues. Biophys J. 2006;91(5):1800–1810. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.065961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eschenhagen T, Fink C, Remmers U, et al. Three-dimensional reconstitution of embryonic cardiomyocytes in a collagen matrix: a new heart muscle model system. FASEB J. 1997;11(8):683–694. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.8.9240969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang YC, Khait L, Birla RK. Contractile three-dimensional bioengineered heart muscle for myocardial regeneration. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;80(3):719–731. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Endoh M. Force-frequency relationship in intact mammalian ventricular myocardium: physiological and pathophysiological relevance. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;500(1-3):73–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janssen PM. Kinetics of cardiac muscle contraction and relaxation are linked and determined by properties of the cardiac sarcomere. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299(4):H1092–1099. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00417.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun LS, Legato MJ, Rosen TS, Steinberg SF, Rosen MR. Sympathetic innervation modulates ventricular impulse propagation and repolarisation in the immature rat heart. Cardiovasc Res. 1993;27(3):459–463. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.3.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Radisic M, Fast VG, Sharifov OF, Iyer RK, Park H, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Optical mapping of impulse propagation in engineered cardiac tissue. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15(4):851–860. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Novosel EC, Kleinhans C, Kluger PJ. Vascularization is the key challenge in tissue engineering. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2011;63(4-5):300–311. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]