Abstract

This article examines general trends in teacher-reported conflict and closeness among 878 children from kindergarten through sixth grade, and examines early childhood characteristics that predict differences in initial levels and growth of conflict and closeness over time. Results indicated modest stability of teacher-perceived conflict and closeness through sixth grade, with relatively greater stability in perceptions of conflict. Levels of conflict at kindergarten were higher for children who were male, Black, had greater mean hours of childcare, had lower academic achievement scores, and had greater externalizing behavior. Children identified as Black and those with less sensitive mothers were at greater risk for increased conflict with teachers over time. Levels of teacher-reported closeness were lower when children were male, had lower quality home environments, and had lower academic achievement scores. The gap in closeness ratings between males and females increased in the middle-elementary school years. Additional analyses were conduced to explore differences in teacher-ratings of conflict between Black and White students.

Keywords: Teacher-child relationships, elementary, conflict, closeness

Teacher-child relationships have emerged as a focus of both theory and research on school adjustment, and have been identified as an important predictor of child outcomes such as social interactions with peers (Howes, Hamilton, & Matheson, 1994; Howes, Hamilton, & Philipsen, 1998), social boldness (Rimm-Kaufman et al., 2002), academic success (Burchinal, Peisner-Feinberg, Pianta, & Howes, 2002; Pianta, La Paro, Payne, Cox, & Bradley, 2002; Pianta, Nimetz, & Bennett, 1997), and adjustment to school (Pianta & Steinberg, 1992). Despite the potential importance of these relationships, we lack a thorough understanding of how relationship quality changes over time as children form new relationships with different teachers each year. Whereas some children tend to experience consistency in the quality of relationships they form with teachers over the years, others experience more variability (Howes, Hamilton, & Philipsen, 1998; Pianta, & Stuhlman, 2004a; Pianta, & Stuhlman, 2004b). Moreover, some of the variation in relationship quality between children may be explained by characteristics that children have when they enter school. For example, there is some suggestion that characteristics such as maternal attachment status, socioeconomic status, race, gender, and behavioral problems relate to differences in relationship quality with non-parental adults (O’Connor & McCartney, 2006; Pianta, & Stuhlman, 2004a; Vondra, Shaw, Swearingen, & Owens, 2001). The present study describes individual student trajectories of relationship quality from kindergarten to sixth grade, and examines the extent to which demographic, behavioral, academic, familial, and early-childcare characteristics predict differences in both initial relationship quality with teachers at kindergarten and changes in relationship quality from kindergarten through sixth grade.

Unlike most primary attachment figures, teachers are fairly transient figures in children’s lives, and the strength and influence of these relationships on child development may seem comparatively inconsequential to long term development. However, there is evidence that the relationships teachers form with children are meaningful in and of themselves, as well as being predictive of later outcomes (Burchinal, Peisner-Feinberg, Pianta, & Howes, 2002; Howes, Hamilton, & Philipsen, 1998; Howes, Hamilton, & Matheson, 1994; Pianta, La Paro, Payne, Cox, & Bradley, 2002; Pianta, Nimetz, & Bennett, 1997). Children display the same patterns of interaction with teachers that are observed in parent-child relationships, and these attachment classifications present with similar frequencies in both groups (Hamilton & Howes, 1992; Pianta & Steinberg, 1992). Moreover, individual children may be able to form relational styles with teachers that are different from the relationships they have formed with their parents (Gossens & van IJzendoorn, 1990; Howes, Hamilton, & Philipsen, 1998; van IJzendoorn, Sagi, & Lambermon, 1992), which may be particularly important for children who have poor parent-child relationships. Teacher-child relationships may also add unique power, in addition to mother-child attachment characteristics, in predicting child outcomes (van IJzendoorn, Sagi, & Lambermon, 1992). These findings emphasize the importance of teacher-child relationships on child development, and call attention to the necessity for continued exploration of the nature of these relationships.

Relationships in the Context of Schools

When examining teacher-child relationships it is critical to consider the environment in which these interactions take place. The school environment differs considerably from other environments in which children form important early relationships, such as home or child-care settings (see Pianta, in press). Within school, children are subjected to an environment that is continually changing. Children experience changes in classrooms, peer groups, academic levels, physical settings, curriculum styles, expectations, regulations, and of course, teachers. Therefore, relationships with different teachers over the years are embedded within different contexts that are also changing over time. Unlike most home environments that remain constant and are comprised of consistent attachment figures, in school, children are experiencing much more fluctuation in factors that potentially influence relationships. Children’s relationship patterns reflect fluctuating external characteristics as well as internalized characteristics of the child. Examining children’s relationships over time allows us to examine consistent trends in relationship patterns across differing external environments.

Stability and Growth Trends in Teacher-Child Relationships

An important question arising from the literature on teacher-child relationships is whether children form separate relational patterns with each teacher or if, over time, they begin to develop a more generalized relational pattern that is then applied to the category of teachers (Howes, 1999; Howes & Hamilton, 1992). Most research on the stability of child-adult relationships over time has focused on attachment relationships between mothers and children and indicates a modest to high stability of attachment style throughout childhood (Howes, Hamilton, & Philipsen, 1998; Vondra, Shaw, Swearingen, & Owens, 2001; Wartner, Grossmann, Fremmer-Bombik, Suess, 1994) and adolescence (Allen, McElhaney, Kuperminc, & Jodl, 2004). It is important to note that mother-child attachments examine a specific relationship with one caregiver across time. Stability in teacher-child relationships, on the other hand, must examine the continuity in a child’s relationships with multiple adults over time. There is some evidence that younger children (i.e. toddlers) experience stability in relationships with teachers if the teacher remains constant and experience change if the teacher changes, but toward the preschool years children seem to have more continuity in relationships even with changing teachers (Howes & Hamilton, 1992). This may reflect children’s increasing ability to internalize relational styles over time, so that as children mature their relationships are more dependent on internalized styles than on the characteristics of each teacher. Research focused on attachment relationships with teachers found that 57% of attachments between teachers and children were stable from the toddler to preschool years (Howes, Hamilton, & Philipsen, 1998). Other research has found moderate correlations between different teachers’ perceptions of an individual student from preschool through first grade (Pianta, & Stuhlman, 2004a; Pianta, & Stuhlman, 2004b). Therefore, while children experience some consistency in relationship quality over time, there also appears to be variation between children in quality of relationships.

General trends in teacher-child relationships likely reflect typical developmental changes, such as the internalization of relational models and the shift from adult-control to self-control of behaviors (Bowlby, 1969; Cincchetti, Ganiban, Barnett, 1991; Kopp, 1989). For example, young children depend on adults to tell them what is appropriate behavior, to monitor their behavior, and to correct their behavior when necessary. However, as they get older, children are increasingly able to monitor and control their own behavior, without as much feedback from adults. As children grow, relationships with teachers may play a different functional role in their lives, and general trends in trajectories of teacher-child relationship quality may reflect these normative changes. For example, there is some indication that both closeness and conflict decrease over the early years of school (Pianta & Stuhlman, 2004b). In addition, theory on the transition to middle school suggests that as children get older, schools change in ways that do not meet their developmental needs (Eccles and Midgley, 1989; Harter, 1996). As children enter middle school, classes get bigger, students spend less time with teachers, and relationships become more evaluative and competitive. Although it is generally accepted that students need more supportive and positive relationships during this developmental period, these relationships may be less available during middle school. It is possible that teacher-child relationships generally decline in quality during this transition. Despite average changes in teacher-child relationship quality over time that can be attributed to normal developmental changes in children, trajectories of teacher-child relationship quality are likely influenced by myriad other factors. However, little research has identified these contributing factors and examined how they influence growth over time.

Factors that Influence Trajectories of Teacher-Child Relationships

Relationships between teachers and children operate as part of a complex system, which is dependent on a number of factors including the context of the relationship, attributes and attachment history of both the teacher and child, internalized relational styles that the teacher and child have developed, the child’s cognitive development and home environment, as well as a broad array of other factors (Ford & Lerner, 1992; Pianta, Hamre, & Stuhlman, 2003; Sameroff, 1995). Children have already developed relational styles with parents and caregivers that may shape the formation of relationships with teachers. Other factors, such as early life experiences, children’s behavior, and children’s ability level at school entry may all affect how children interact with teachers. For example, research had supported the idea that early environment affects children’s relational behavior in school, in turn influencing the quality of relationships that children form with teachers (Ladd, Birch, & Buhs, 1999). The experiences and characteristics that children bring with them to school may influence their relational experiences within school, and may help to explain between-children differences in trajectories of relationship quality over time. Although various studies have explored child level predictors of teacher-child relationship quality, few have examined predictors of change in relationship quality over time. The present study examines demographic characteristics and early environmental experiences that may predict variations in initial relationship quality with teachers in kindergarten as well as variations in the trajectories of teacher-child relationships through sixth grade.

Demographic Predictors

A number of demographic characteristics may influence the quality of relationships that children form with teachers. Gender has been linked to teacher-child relationships, such that boys typically experience greater levels of conflict and girls experience more closeness (Bracken & Crain, 1994; Hamre & Pianta, 2001; Ladd, Birch, & Behs, 1999; Saft & Pianta, 2001). Gender may also contribute to differences in relationship trajectories over time. Hamre and Pianta (2001) found that early dependency on teachers predicted later conflict only in boys, and that early closeness with teachers predicted less conflict in later reports of behavior. Therefore, characteristics of children at school entry may not have the same longitudinal effect on relationships for both boys and girls.

Other factors that may influence teacher-child relationship trajectories are socioeconomic status (SES) and race. Children coming from families of lower SES and maternal education are more likely to be placed in classrooms that are more teacher-directed and less positive than their peers with greater socioeconomic resources (Pianta, La Paro, Cox, & Bradley, 2002). These, in turn, may foster poorer relationships between teachers and students. Consistent with this idea, children identified as having higher levels of socioeconomic risk display greater relational risk both in mother-child and teacher-child relationships (Pianta, & Stuhlman, 2004a). Past research has found ethnicity to be a small but significant predictor of both closeness and conflict in teacher-child relationships (Saft & Pianta, 2001). This study also found that ethnic match between teachers and children was related to more positive teacher ratings of relationships. In studies comprised of predominantly Caucasian teachers, Caucasian children have been found to have closer relationships with teachers than African American children (Ladd, Birch, & Behs, 1999). Children who enter school with high levels of socioeconomic risk may experience less optimal relationships with their teachers, and there may be differences in how teachers perceive their relationships with children of different racial and ethnic backgrounds.

Early Childhood Experiences and Child Characteristics

A number of environmental factors have already influenced child development prior to school entry, and characteristics of these early environments may affect the formation of later relationships with teachers. For example, the quality of the home environment has been linked to the quality of care children receive in other environments, such as non-maternal care in child-care home settings (NICHD-ECCRN, 1997). Therefore, it is possible that the quality of early care in the home is related to children’s experiences in school, such that children who experience higher quality home environments are more likely to experience higher quality care in school as well. Children who receive higher quality care may in turn experience higher quality relationships with teachers.

An important component of early child-care experience is maternal sensitivity. Having a sensitive mother is related to a number of child outcomes, such as social inhibition (Early, Rimm-Kaufman, & Cox, 2002), academic and social competence (NICHD ECCRN, 2001a; 2001b; 2002a), and behavior problems (Rimm-Kaufman, et al., 2003). Children with more sensitive mothers may learn better social-relational skills and display more positive behaviors in relationships with other adults, impacting later relationships with teachers. Maternal sensitivity may be especially influential on early relationships with teachers, as this is likely one of the few close adult relationships children have formed prior to school. However, as children mature and experience increasing exposure to adults outside of the home, the impact of maternal sensitivity is expected to become less salient. Therefore, maternal sensitivity is likely to be a better predictor of early relationship quality than of differences in relationship quality over time.

Security in past relationships appears to predict the quality of future relationships (see Howes et al., 1998), and it is likely that the quality of relationships children form with their primary caregiver is related to the quality of relationships they later form with teachers (Pianta et al., 1997). However, various theories on how relationships with teachers may influence child development have emerged from the literature on attachments with multiple caregivers (Howes, 1999; Howes & Matheson, 1992; Pianta, 1992; van IJzendoorn, Sagi, & Lambermon, 1992). Some evidence has shown that caregivers are able to form secure relationships even with children who lack previous secure relationships with parents (Goossens & van IJzendoorn, 1990). Research specifically examining the affects of maternal attachment on later teacher-child relationship quality has found that early maternal relationships do influence later relationships with teachers (O’Connor & McCartney, 2006), such that poor maternal attachments predict poor teacher-child relationships. Moreover, this study found that good relationships with early teachers mediated the effects of poor maternal attachment on later teacher-child relationships. This research suggests that relationships with teachers may be especially important for children who have not had prior opportunity to build adaptive relational skills, and that attachment status will not necessarily predispose children to poor teacher-child relationships over time. Based on this research, attachment classification is expected to be a greater predictor of early relationship quality with teachers than of differences in trajectories of relationship quality over time.

Children’s early experiences often extend beyond maternal care, and later relationships with teachers are likely influenced by time spent in non-maternal child-care. Children who spend a greater amount of time in child-care have been found to have higher levels of conflict in their relationships with teachers (NICHD-ECCRN, 2005). However, this relationship appears to decline over time and was no longer significant by third grade. Therefore, quantity of child-care is expected to predict differences in initial relationship quality, but this effect is not likely to affect growth of conflict or closeness over time.

By the time children enter school, they have developed numerous behavioral and relational strategies that potentially influence their relationships with teachers. Several studies suggest that behavioral problems are related to both parent-child and teacher-child relationships. For example, closeness in parental relationships is inversely related to behavior problems (Miliotis, Sesma, & Masten, 1999), and moderate correlations have been found between early ratings of behavior and teacher-child relationship quality (Hamre & Pianta, 2001). Howes, Phillipsen, and Peisner-Feinberg (2002) found that behavioral problems at preschool were the strongest predictor of conflict in teacher-child relationships, accounting for 37% of the variance in their model. Additionally, the relationship between gender and conflict may be influenced by boy’s increased display of conflict producing behaviors, which relate to poorer relationships with teachers (Ladd et al., 1999). Therefore, children who enter school with higher ratings of behavioral problems are likely to experience greater conflict and less closeness with teachers, and this effect may continue to impact teacher-child relationship quality over time.

Teacher-child relationships occur almost exclusively within the context of the school environment, and education and academic achievement are a major component of this environment. Therefore, it seems likely that academic achievement is also a significant component of teacher-child relationships, particularly as viewed by the teacher. In fact, the quality of teacher-child relationships has been found to predict a number of academic outcomes (Hamre & Pianta, 2001; Pianta et al., 2002), suggesting that good teachers increase academic achievement through positive relationships. However, it is also possible that children who enter school with greater academic abilities are more likely to be viewed positively by teachers. Teachers may be more likely to invest in relationships with children who are actively engaged in learning activities going on in the room. Children who are less successful at academic tasks may experience frustration in school, and may be less likely to participate actively in activities. Therefore, relationships between teachers and children may be better for children who come to school with more developed academic abilities.

In summary, a number of demographic, early environmental, and child characteristics are likely to affect the quality of teacher-child relationships both in kindergarten and throughout sixth grade. Based on the above theory and research, the following factors were included in this study as predictors of teacher-child relationship quality: gender, socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, quality of the home environment, maternal sensitivity, quantity of early child-care, behavior problems, mother-child attachment classification, and academic achievement.

The Present Study

The present investigation (a) examined the stability of teacher-ratings of conflict and closeness from kindergarten to sixth grade; (b) described initial levels of conflict and closeness between teachers and children at kindergarten and examines general trends in linear and curvilinear growth of conflict and closeness over the first seven years of school; and (c) examined variations in the intercept and slope of these trajectories based on child, family, and environmental traits present at 54 months. Based on previous research on stability and quality of relationships between teachers and children and the factors that contribute to these relationships, the following hypotheses were made:

Stability of Conflict and Closeness over Time: Based on the research discussed above, we expect that the overall stability of conflict and closeness over the first seven years of school will be low to moderate, as children are likely to form different types of relationships with different teachers and at different developmental time points. We also expect conflict to be more stable over time than closeness.

General Trends in Overall Growth: Based on past findings that both closeness and conflict decrease in the early years of school (Pianta & Stuhlman, 2004b), we expect slight decreases in both conflict and closeness in early elementary school. However, due to developmental and environmental changes occurring in later elementary and early middle school, we expect a greater overall decline in closeness as school becomes more focused on instruction and less on interactions between teachers and children, and an overall increase in conflict as children enter later childhood and early adolescence.

Demographic Predictors: We expect that boys, Black children, and children with low maternal education will have higher initial levels of conflict and greater growth in conflict over time, and that these children will have lower initial levels of closeness and greater decrease in closeness over time.

Early Environmental and Child Predictors: We expect that children with higher quality home environments and those with more sensitive mothers will have greater initial levels of closeness, lower initial conflict, less decline in closeness over time, and less increase in conflict over time. Because the effects of the quantity of early child-care appear to be strongest in the early years of school, we expect that children who spend a greater amount of time in non-matenral care will have higher initial levels of conflict. However, we expect that this effect will disappear over time and will not significantly affect trajectories of conflict or closeness in teacher-child relationships. Children with greater levels of behavioral problems and those with lower academic ability are likely to have lower initial levels of closeness and higher initial levels of conflict. Moreover, we expect that these children will experience greater increases in conflict over time and greater decreases in closeness. We expect that children with insecure attachment styles will have poorer teacher-child relationships in kindergarten, but we expect the effects of mother-child attachment style to lessen over time as children form different types of relationships with other adults, and therefore do not predict that attachment will have lasting effects on growth over time.

Methods

Participants

A sub-sample of 878 children from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development’s Study of Early Child Care (NICHD SECC) were participants in this study. The NICHD SECC is a prospective, longitudinal study that recruited participants through hospital visits across 10 sites in the United States. All women giving birth at these sites in 1991 (N = 8,986) were screened for eligibility. Of the 5,416 women who met sampling criteria, 1,364 families were randomly selected and became participants in the study. Observations and reports of children, parents, and teachers were recorded each year from birth through sixth grade.

Because Growth Curve Modeling requires data at three or more time points, but is able to include missing data, children used in this study were those with available conflict and closeness data for at least three of the seven time points. Just under 65% of the original NICHD-SECC sample was used in this study. Of these children, 55% had conflict and closeness data at all 7 time points, 26% had data at 6 time points, 10% at 5 time points, 6% at 4 time points, and 3% had data at only 3 time points. Forty-nine percent of the children in this study were male. Eleven percent of children were identified by parents as Black, 5.5% as Hispanic, and 4.2% as other race/ethnicity. Maternal education in this sample ranged from 7 to 21 years of school (M = 14.49; SD = 2.41). When compared to the original NICHD sample, this sub-sample had higher average maternal education (F = 26.5, p < .001), and a greater average income-to-needs ratio (F = 7.3, p < .01).

In kindergarten, 97% of children (with teachers who reported demographic information) had a female teacher, and 88% had a Caucasian teacher. The average kindergarten class had 21 children (SD = 5.9), and was led by a teacher with an average of 15 years teaching experience (SD = 8.9). In first grade, 96% of teachers were female, and 94% were Caucasian. The average first grade classroom had 21 children (SD = 5.3) and a teacher with 14 years of experience (SD = 9.5). Second grade teachers were 95% Caucasian with an average of 12 years teaching experience (SD = 10.1), and were a mean age of 45 (SD = 10.7). Third grade teachers were 92% Caucasian, with an average age of 42 (SD = 10.9), and 11.8 years of teaching experience in a public school (SD = 10.4). In fourth grade, teachers were 94% Caucasian, with an average of 11.4 years teaching experience in public schools (SD = 10.3), and with an average age of 41 (SD = 11.0). The average fourth grade class had 23 students (SD = 5.0). Fifth grade teachers were 93% Caucasian, had a mean of 12 years public school teaching experience (SD = 10.7), and were an average of 43 years old (11.2). The average fifth grade classroom contained 23 students (SD = 5.1). Finally in sixth grade, teachers were 94% Caucasian, had a mean of 11.4 years public school teaching experience (SD = 10.5), and had an average age of 42 (SD = 10.9). The average sixth grade class was comprised of 23 students (SD = 6.3).

Measures

Teacher-child Relationships

Relationships between teachers and children were assessed by using the Student-Teacher Relationship Scale (STRS). The STRS (Pianta, 2001) is a self-report measure of teacher perceived relationships with individual students. This study used the Conflict and Closeness subscales of the STRS to assess teacher perceived conflict and closeness with each student (Pianta, 2001). Conflict items are designed to attain information about perceived negativity within the relationship (e.g. “This child remains angry or is resistant after being disciplined,” “This child is sneaky or manipulative with me,” and “This child easily becomes angry with me”), while Closeness items ascertain the extent to which the relationship is characterized as warm, affectionate, and involving open communication (e.g. “I share an affectionate, warm relationship with this child,” “If upset, this child will seek comfort from me,” and “This child spontaneously shares information about himself/herself”). Items are rated on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 “definitely does not apply” to 5 “definitely applies”. The conflict subscale is comprised of seven items, and the closeness subscale is comprised of eight items. In order to make conflict and closeness scores comparable in this study, each child’s total conflict and closeness scores were divided by the total number of items measuring that construct, such that conflict and closeness scores indicate the average score per item. In terms of reliability, statistically significant test-retest correlations over a four-week period, and high internal consistency for both conflict and closeness subscales has been established (Pianta, 2001). The STRS has also demonstrated predictive and concurrent validity, and is related to current and future academic skills (Hamre & Pianta, 2001), behavioral adjustment (Birch & Ladd, 1998), risk of retention (Pianta, Steinberg, & Rollins, 1995), disciplinary infractions (Hamre & Pianta, 2001), and peer relations (Birch & Ladd, 1998). Cronbach’s alpha for conflict is .85 and for closeness is .84. The STRS was completed annually for each child from kindergarten through sixth grade by that child’s current teacher. Table 1 presents means and standard deviations for all predictors.

Table 1.

Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations of Predictor and Outcome Variables (N=878)

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Mothers Education | 14.49 | 2.41 | - | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Maternal Sensitivity | 0.05 | 0.69 | .49*** | - | |||||||||||||||||||

| 3. HOME Score | 46.3 | 5.2 | .47*** | .54*** | - | ||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Mean Hrs in Care | 32.4 | 12.6 | −.09** | −.17*** | - | ||||||||||||||||||

| 5. Academic Achievement | 100 | 11.5 | .41*** | .45*** | .48*** | - | |||||||||||||||||

| 6. Internalizing Behavior | 47.1 | 8.86 | −.10** | −.10** | −.14*** | - | |||||||||||||||||

| 7. Externalizing Behavior | 51.5 | 9.4 | −.13*** | −.17*** | −.23*** | .60*** | - | ||||||||||||||||

| 8. Conflict @ Kindergarten | 10.40 | 5.18 | −.10** | −.19*** | −.14*** | .13*** | −.18*** | .09** | .18*** | - | |||||||||||||

| 9. Conflict @ 1st Grade | 10.72 | 5.01 | −.14*** | −.18*** | −.17*** | .17*** | −.16*** | .21*** | .38*** | - | |||||||||||||

| 10. Conflict @ 2nd Grade | 10.77 | 5.32 | −.16*** | −.31*** | −.27*** | .15*** | −.23*** | .10** | .21*** | .41*** | .44*** | - | |||||||||||

| 11. Conflict @ 3rd Grade | 11.42 | 5.81 | −.17*** | −.27*** | −.20*** | .11** | −.21*** | .17*** | .33*** | .46*** | .54*** | - | |||||||||||

| 12. Conflict @ 4th Grade | 10.74 | 5.41 | −.21*** | −.27*** | −.27*** | .14*** | −.20*** | .16*** | .30*** | .36*** | .43*** | .47*** | - | ||||||||||

| 13. Conflict @ 5th Grade | 11.13 | 5.37 | −.21*** | −.27*** | −.28*** | −.20*** | .13*** | .24*** | .40*** | .37*** | .40*** | .46*** | - | ||||||||||

| 14. Conflict @ 6th Grade | 10.74 | 5.41 | −.17*** | −.20*** | −.24*** | .10** | −.21*** | .12** | .19*** | .39*** | .33*** | .39*** | .43*** | .51*** | - | ||||||||

| 15. Closeness @ Kindergarten | 34.25 | 5.33 | .10** | .11** | .18*** | .17*** | −.24*** | −.11** | −.12** | - | |||||||||||||

| 16. Closeness @ 1st Grade | 34.10 | 5.03 | .10** | .10** | .15*** | .12*** | −.28*** | −.11** | −.10** | −.10** | −.17*** | .30*** | - | ||||||||||

| 17. Closeness @ 2nd Grade | 33.70 | 5.18 | .13*** | .15*** | .18*** | .13*** | −.11** | −.36*** | −.19*** | −.15*** | −.15*** | −.18*** | .26*** | .36*** | - | ||||||||

| 18. Closeness @ 3rd Grade | 33.01 | 5.17 | .10** | .09** | .17*** | .13*** | −.09** | −.16*** | −.17*** | −.37*** | −.13** | −.15*** | −.17*** | .25*** | .32*** | .30*** | - | ||||||

| 19. Closeness @ 4th Grade | 32.69 | 5.08 | .10** | .11** | −.11** | −.19*** | −.34*** | −.14*** | −.17*** | .15*** | .24*** | .22*** | .35*** | - | |||||||||

| 20. Closeness @ 5th Grade | 31.91 | 5.32 | .11** | .11** | .17*** | −.32*** | −.17*** | .17*** | .26*** | .25*** | .31*** | .32*** | - | ||||||||||

| 21. Closeness @ 6th Grade | 30.49 | 5.61 | .10** | −.11** | −.28*** | .15*** | .24*** | .27*** | .23*** | .23*** | .31*** | - |

Only significant correlations reported;

= p < .01;

= p < .001

Demographic Characteristics

Gender, ethnicity, and years of maternal education were collected from parents when children were one month old. Gender was coded as a 1 (male) or 0 (female). Ethnicity was reported by parents, and mutually exclusive categories were used for this study. Children who were not classified by parents as White, Black, or Hispanic, were grouped together as “Other” due to the small numbers of children representing these other racial categories. All ethnic variables were dummy coded and are compared to the majority group (White) in analyses. Because maternal education has been shown to be a good indicator of child outcomes in the school environment (NICHD ECCRN, 2002b; Peisner-Feinberg, Burchinal, Clifford, et al., 2001; Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000), socioeconomic risk in this study will be assessed by level of maternal education. The variable used in this study was continuous years of maternal education.

Maternal Sensitivity

Maternal sensitivity was rated by trained observers during a structured home/lab activity at 6, 15, 24, 36, and 54 months. At 6, 15, and 24 months, mothers were rated on a 4 point qualitative rating scale in areas such as sensitivity to distress, stimulation of cognitive development, intrusiveness, positive regard for the child, and flatness of affect. At 36 months mothers were rated on a 7-point scale in areas of supportive presence (i.e., a mother’s ability to provide a secure base for the child and to encourage exploration of the environment), respect for child’s autonomy, stimulation of cognitive development, and hostility. At 54 months mothers were rated on a 7-point scale in areas including adult supportive presence, respect for autonomy, cognitive stimulation, quality of assistance, and hostility. At each time point a composite maternal sensitivity score was computed based on relevant items rated at each age. At 6, 15, and 24 months this composite was comprised of the sum of 4-point ratings on sensitivity to nondistress, positive regard, and intrusiveness (reverse scored). The maternal sensitivity composite at 36 months was the sum of ratings on three 7-points scales: supportive presence, respect for autonomy, and hostility (reverse scored). At 54 months a maternal sensitivity composite was created from supportive presence, respect for autonomy, and hostility (reverse scored). Average interclass correlations were used to determine intercoder reliability, and ranged from .83 to .87 across time points. Cronbach alphas were .75, .70, .79, .78, and .85 for respective time points. Maternal sensitivity has demonstrated predictive validity of constructs such as academic and social competence (NICHD ECCRN, 2001a; 2001b; 2002a). In this study, the mean of standardized scores of maternal sensitivity was computed for all 5 time points, indicating average maternal sensitivity up to 54 months.

Child Attachment Classification

Attachment style was rated when children were 15 months by use of the strange situation technique (see Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978). Strange Situation procedures were taped and rated by trained observers. Children were rated on four behaviors: proximity and contact seeking, contact maintaining resistance (i.e., the infant displays both contact seeking behavior and angry resistance toward mother), and avoidance. Children were then categorized into one of three attachment classifications: Secure (B), Insecure-Avoidant (A), and Insecure-Resistant (C). Children who were rated Secure were able to use their mothers for comfort and reassurance when distressed, thereby assuaging their anxiety. Avoidant children were those who tended not to be distressed by separation from their mothers and who refused contact with their mother upon her return. Resistant children became quite distressed when separated from their mothers, and alternated between seeking and resisting contact with her when she returned to the room. Taped interactions were rated by a team of 3 trained observers. Agreement between raters for the 5-category system was 83% (Kappa = .69), and 86% for the 2-category system (Kappa = .78). In cases of disagreement, coders conferenced and arrived at an agreed-upon code. Tapes were periodically double coded and intercoder agreement ranged from .93 to .96.

Quality of Home Environment at 54 Months

The Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME; Cladwell & Bradley, 1984) was used to assess the quality of children’s home environments at 54 months. This scale is comprised of 58 items that rate learning materials available to the child, language stimulation, physical components of the environment, parental responsiveness to the child, learning stimulation, parent’s modeling of social maturity, variety of experience available to the child, and parental acceptance of the child. Ratings by trained observers were compared with gold standard codes every 4 months, and trained raters maintained 90% agreement with the master coder. This scale has moderate internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = .82).

Quantity of Non-Maternal Child-Care Prior to 54 Months

Non-maternal child-care was defined as any child-care provided in or outside of the home and included care by fathers, relatives, non-relatives, centers, and other providers. The mean hours of child-care per week was obtained through parent interviews occurring at 3-month intervals prior to 36 months, and at 4-month intervals thereafter. In this study, the mean hours of care per-week was averaged from birth through 54 months.

Academic Achievement at School Entry

The Woodcock-Johnson Test of Achievement -Revised (WJ-R ACH; Woodcock & Johnson 1989) was used to assess academic ability at 54 months. The mean of standardized scores for the Letter-Word Identification, Applied Problems, and Word Attack subtests was computed to indicate overall academic ability prior to school entry. Letter-Word Identification measures the ability to identify isolated letters and words. Applied Problems measures the ability to solve practical mathematical problems, and the Word Attack subtest requires the use of phonic and structural skills to pronounce unfamiliar words. This battery has adequate test-retest (alpha = .80 – .87) and internal consistency reliability (.94 –.98), and is related to other measures of academic ability such as the Bracken Basic Concepts Scale (McGrew et al., 1991).

Maternal Ratings of Behavior at 54 Months

Mothers rated their child’s behavior on The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991). This scale is comprised of 118 items that measure a range of behavioral and emotional problems. Mothers rated how well each item described their child’s behavior over the past six months, with responses of 0 (not true), 1 (sometimes true), and 2 (often true). The scale is broken down into eight subscales, which load onto either the Internalizing Scale (comprised of the Withdrawn, Somatic Complaints, and Anxious/Depressed scales) or the Externalizing Scale (comprised of the Delinquent and Aggressive Behaviors scales). Achenbach reported a .70 agreement level between parents, a .71 level of stability over a 2 year period, and test-retest reliability of .89. For this study, standardized t scores were used for the externalizing and internalizing scales.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each of the variables included in this study. In order to assess the relatedness of the two dependent variables, correlations between conflict and closeness were examined across the seven time points. Additionally, correlations between conflict and closeness at each time point and the predictor variables were examined.

Growth Curve Modeling using Hierarchical Linear Modeling (GCM)

GCM postulates that individual growth over time is a function of where the individual starts (the intercept) and the rate of change over time (the slope). These two components shape the trajectory of the individual over time. Once individual growth trajectories have been established, GCM allows the researcher to examine differences in intercepts and slopes attributable to predictor variables (e.g. gender, race, & SES). Several benefits are associated with using GCM as opposed to other methods. First, GCM, although requiring at least 3 time points, allows for the inclusion of subjects with missing data. The second benefit is that GCM can incorporate time-specific measurement error into the analysis. Third, GCM can assess the covariance of the slope and the intercept, making it possible to examine how starting points affect the rate of change of individual trajectories.

Separate growth curve models were conducted for conflict and closeness. First, an unconditional model attempted to fit an overall growth curve to all subjects included in the model, and to determine if significant variability exists around the average intercept and slope. The second step was to add predictor variables that might account for some of the variance in the unconditional model.

Results

Correlations Among Variables

Table 1 presents correlations, means, and standard deviations of predictor and outcome variables. Both conflict and closeness demonstrated modest stability over time. Individual correlations between consecutive years of conflict scores ranged from .38 – .54. By first grade, all consecutive years correlated at or above .44, and there was a moderate correlation between conflict at first grade and conflict at sixth grade. Correlations between closeness in consecutive years ranged from .30 – .36, and a significant correlation was found between teacher-ratings of closeness at first and sixth grade. At each time point, closeness and conflict were negatively correlated.

In order to test the overall stability of teacher-perceived conflict and closeness over the first seven years of school, a LAG variable was computed for conflict and for closeness. The LAG variable allows the conflict/closeness scores at each time point to be matched with conflict/closeness scores from the previous time point, so that a single correlation can be computed to represent overall stability of conflict/closeness over the first seven years of school. The overall correlation between conflict scores across the seven year time period was 0.47, and for closeness was 0.35. These two correlations were then statistically compared, and results suggest that different teacher’s perceptions of conflict (r = 0.47) are relatively more stable over the first seven years of school than are different teacher’s perceptions of closeness (r = 0.35), z = 3.03, p = 0.002.

Teacher ratings of conflict at each grade were negatively correlated with maternal education, maternal sensitivity, HOME scores, and academic achievement. Teacher ratings of conflict were positively correlated with mean hours in child-care outside the home prior to 54 months. Internalizing behavior was positively related to conflict at kindergarten, second, third, and fourth grade, and externalizing behavior was positively related to conflict at all time points. Higher levels of teacher-reported conflict in the previous grade were related to greater conflict in the current grade.

Correlations between teacher-ratings of closeness and predictor variables were less consistent across the years, however, some general trends were observed. Higher maternal education and higher scores on the HOME scale were related to greater teacher-reported closeness through 5th grade, and greater maternal sensitivity was related to greater closeness in every grade except 4th. Higher academic achievement was related to greater closeness from kindergarten through third grade, and then became non-significant. No relationships were found between closeness and internalizing behavior, externalizing behavior, or number of hours in child care prior to 54 months. Higher teacher-perceived closeness in the previous grade was related to greater closeness at each time point.

Growth Curve Modeling

Individual growth curve analysis was used to explore trajectories of conflict and closeness in teacher-child relationships over time. SAS PROC MIXED was used to conduct all analyses (see Singer, 1998). This type of analysis allowed examination of individual changes over time (unconditional model) and differences between individual trajectories due to demographic and environmental characteristics of children upon school entry (model with predictors). Separate models were run for conflict and closeness.

Unconditional Model for Conflict

In order to determine the best fit for the data, models with both linear and quadratic growth were examined. In order to determine the best fitting model, the difference between the −2LL statistic for the linear only and the linear plus quadratic models were compared with a Chi-square table. For this data, the model containing both linear and quadratic terms provided a significantly better fit than the linear model alone. Therefore, the baseline model for conflict included both linear and quadratic terms. Results of unconditional models can be seen in Table 2. Results of the unconditional model indicated that even when adding both terms into the model at once (thus controlling for each), there remained a significant linear (β = 0.05, p < .001) and quadratic (β = −0.01, p < .001) component to average growth in conflict. The unconditional model examines mean intercept and slope for all individuals, as well as individual variability around these estimates, such that:

Table 2.

Average Intercepts and Slopes and Variability around Intercepts and Slopes for Unconditional Models of Conflict and Closeness (N=878)

| Conflict | Closeness | |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.49*** (0.02) | 4.28*** (0.02) |

| Time (Linear Term) | 0.06*** (0.02) | −0.01 (0.01) |

| Time * Time (Quadratic Term) | −0.01*** (0.00) | −0.01*** (0.00) |

| Variability (Intercept) | 0.23*** (0.02) | 0.16*** (0.02) |

| Variability (Linear Slope) | 0.04*** (0.01) | 0.03*** (0.01) |

| Variability (Quadratic Slope) | 0.00*** (0.00) | 0.00** (0.00) |

= p < .05

= p < .01

= p < .001

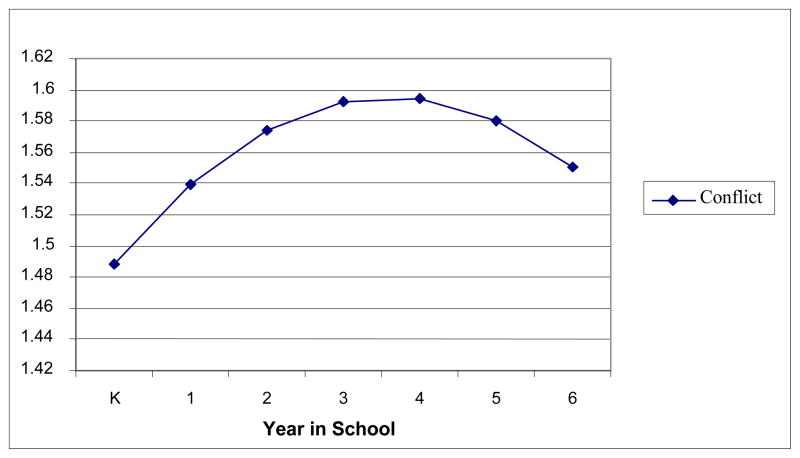

Here conflict for individual i at time j is a function of the sum of the amount of variation around the average intercept (π0j) and around the average slope (π1jTIMEij), the variation around the average intercept and slope for the quadratic term ([π0j + π1jTIMEij ]2), and the residual (εij). Time in both models was centered at kindergarten (i.e., intercepts indicate levels of conflict and closeness upon entry to school). Results indicate that the average level of teacher reported conflict at kindergarten was 1.49 (p < .001), that the average linear growth was 0.06 (p < .001), and that quadratic growth was −0.01 (p < .001). This means that the average child began kindergarten with a teacher-rating of an average of 1.49 on a 1–5 scale, and the average child’s rating of conflict increased by 0.06 points between kindergarten and first grade. The significant quadratic component indicates that the linear increase in growth of conflict gradually lessened over time, such that there were greater increases in the earlier years of school and that this growth slowed in later years (see Figure 1). Therefore, the average child experienced the greatest increase in conflict ratings between kindergarten and first grade and lesser increases between successive years up to fifth grade. After fifth grade, average ratings of conflict began to decline. There was significant individual variation around the average intercept (β = 0.23; p < .001), around the average linear slope (β = 0.04; p < .001), and around the average quadratic slope (β = 0.00; p < .001), meaning that the average intercept, linear slope, and quadratic slope do not adequately describe the growth of all children.

Figure 1.

Average student trajectory of teacher-ratings of conflict from kindergarten to sixth grade.

Predictors of Conflict

Given significant variability around the average trajectory, predictor variables were added to the model in attempt to explain some of this variation. Due to significant variability around both the linear and quadratic slopes, both of these terms were added to the model with predictors, such that this model examined the effects of predictors on initial levels of conflict, rate of linear change in conflict over time, and rate of quadratic change in conflict over time. Complete results are presented in Table 3. When adding predictors to the model, both the linear and quadratic components lost significance (β = 0.05, p = ns; β = 0.03, p = ns). This means that when the effect of predictors is held at zero, there is not significant change in conflict over time. In addition, this model accounted for additional variance around the intercept, linear, and quadratic slopes than did the baseline model alone (β = 0.18, p < .001; β = 0.038, p < .001; β = 0.00, p < .001), although significant variation remained in each case.

Table 3.

Effects of Predictors on Initial Levels (Intercept) and Growth over Time (Slope) for each Model (N=878)

| Model 1: Conflict | Model 2: Closeness | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.17*** | 3.26*** | ||||

| (0.35) | (0.33) | |||||

| Time | 0.05 | −0.10 | ||||

| (0.24) | (0.23) | |||||

| Time * Time | 0.03 | 0.04 | ||||

| (0.04) | (0.04) | |||||

| Intercept | Linear | Quadratic | Intercept | Linear | Quadratic | |

| Maternal Education | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.00 |

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.00) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.00) | |

| Gender | 0.17*** | 0.05 | −0.01 | −0.14** | −0.08* | 0.01* |

| (0.05) | (0.03) | (0.01) | (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.01) | |

| Black | 0.22** | 0.15** | −0.02* | −0.02 | −0.05 | 0.01 |

| (0.09) | (0.06) | (0.01) | (0.08) | (0.05) | (0.01) | |

| Hispanic | −0.07 | 0.03 | −0.00 | −0.00 | −0.06 | 0.01 |

| (0.09) | (0.07) | 0.01 | (0.09) | (0.06) | (0.01) | |

| Maternal Sensitivity @ 54 months | −0.03 | −0.06* | 0.01* | −0.02 | −0.03 | 0.01 |

| (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.01) | (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.01) | |

| HOME Score @ 54 Months | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02** | 0.00 | −0.00 |

| (0.01) | (0.00) | (0.00) | 0.01 | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Mean Hours Child Care up to 54 months | 0.01*** | −0.00 | −0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.00 |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Academic Achievement Scores @ 54 months | −0.01** | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.01* | −0.00 | 0.00 |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Mother Report Behavioral Internalizing @ 54 months | −0.01 | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.00 |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Mother Report Behavioral Externalizing @ 54 months | 0.02*** | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.00 |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Avoidant Attachment Classification | 0.04 | −0.07 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.01 |

| (0.07) | (0.05) | (0.01) | 0.06 | (0.04) | (0.01) | |

| Resistant Attachment Classification | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.00 |

| (0.08) | (0.05) | (0.01) | (0.07) | (0.05) | (0.01) | |

| Disorganized Attachment Classification | 0.08 | −0.05 | 0.01 | −0.04 | −0.03 | 0.01 |

| 0.06 | (0.04) | (0.01) | (0.06) | 0.04 | (0.01) | |

= p < .05

= p < .01

= p < .001

Teachers tended to rate boys as having higher levels of conflict in kindergarten than girls (β = 0.17, p < .001). Black children had significantly higher levels of teacher-perceived conflict in kindergarten than White children (β = 0.22, p < .01). Children who entered school with more hours spent in non-maternal care (β = 0.01, p < .001), lower academic achievement scores (β = −0.01, p < .01), and greater maternal ratings of externalizing behavior at 54 months (β = −0.02, p < .001) had significantly more teacher-reported conflict in kindergarten.

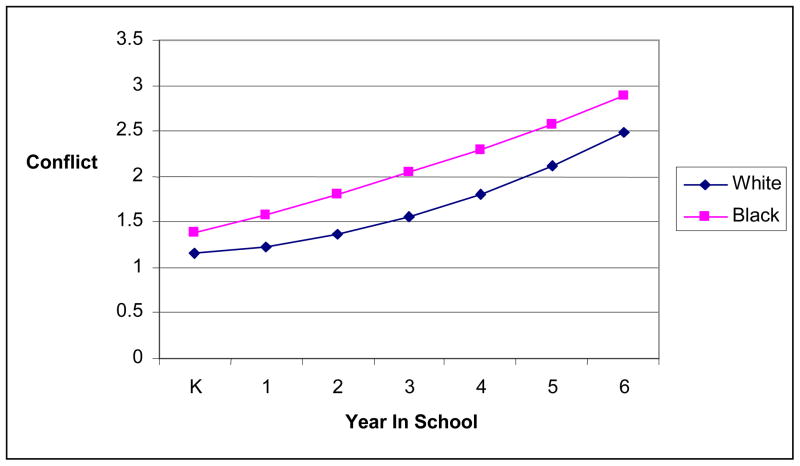

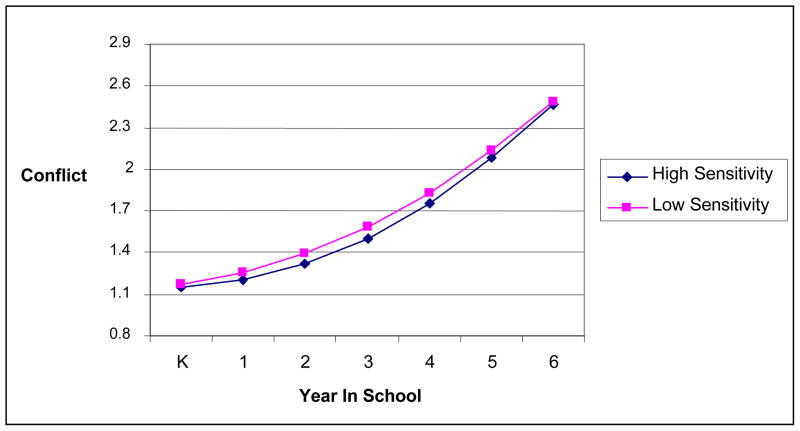

Differences in rate of growth in conflict over time were significantly predicted by race (β = 0.15, p < .01; β = −0.02, p < .05 ) and maternal sensitivity (β = −0.06, p < .05; β = 0.01, p < .01). Children identified as Black experienced a stronger linear affect than children identified as White (see Figure 3). Both groups had less increase in conflict scores in early years of school and greater increases in conflict scores in later years, but the variation in the amount of increase between consecutive years was greater for White children, while Black children’s growth appears more linear. The result is an increasing gap between Black and White children’s conflict scores toward the middle elementary school years. It appears that this gap lessens in later elementary and early middle school. A similar trend appeared with maternal sensitivity. Children with less sensitive mothers experienced more consistent, linear growth in conflict over time, while children with more highly sensitive mothers had less increase in conflict in the early years of school (see Figure 4). However, by late elementary school this gap in conflict scores began to decrease.

Figure 3.

Trajectories of teacher-rated conflict with students from kindergarten to sixth grade for children identified as back and white.

Figure 4.

Trajectories of teacher-ratings of conflict with students from kindergarten to sixth grade for children with mothers with high or low ratings of maternal sensitivity.

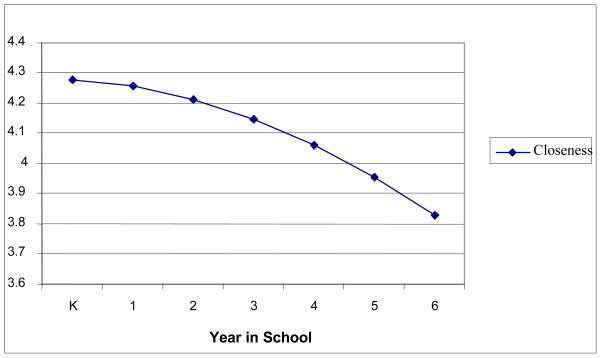

Unconditional Model for Closeness

Examination of fit statistics indicated that the best fitting unconditional model for closeness was one that included the linear and quadratic term (e.g., lower −2LL). Once the quadratic term was entered into the model (β = −0.01, p < .001), the linear effect became non-significant (β = −0.01, p = ns), indicating that when controlling for quadratic growth in closeness, the average linear growth is not significantly different from zero. The following equation represents this model:

Here closeness for individual i at time j is a function of the sum of the variation around the average intercept (π0j), slope (π1jTIMEij), quadratic slope (π1jTIMEij)2, and error (εij). The average rating of teacher-child closeness at kindergarten for all children was 4.28 (p < .001), and on average there was no significant decrease in growth between kindergarten and first grade (β = −0.01, p = ns). However, the significant quadratic component indicates that the average child experienced exponentially greater decrease in closeness over time, such that the change in closeness between kindergarten and first grade was less than the difference in scores between first and second grade. Therefore, the average child experienced greater decreases in closeness over time. There was significant variability around the intercept (β = 0.16, p < .001), linear slope (β = 0.03, p < .001), and quadratic slope (β = 0.00, p < .001).

Predictors of Closeness

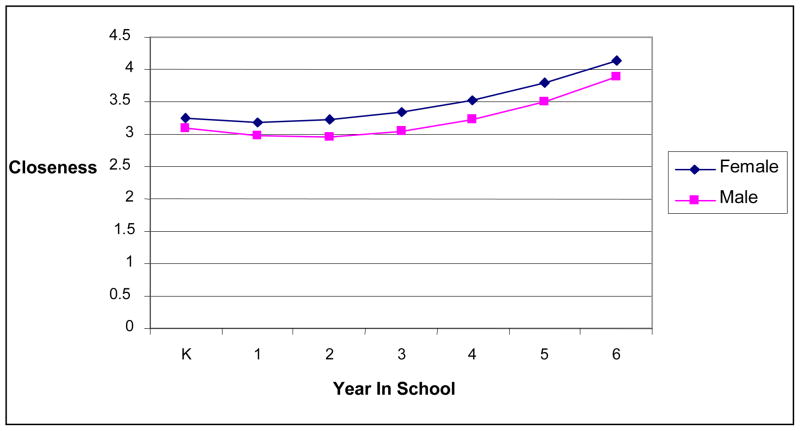

As with conflict, due to significant individual variation around the average intercept, linear slope, and quadratic slope, all three were entered into the model with predictors. Results can be seen in Table 3. Gender was a significant predictor of teacher ratings of closeness at kindergarten, with boys being rated an average of 0.14 points lower than girls on a scale of 1–5 (β = −0.14, p < .01). Higher scores on the HOME scale were related to greater teacher-reported closeness at kindergarten (β = 0.02, p < .01), as were higher academic achievement scores at 54 months (β = 0.01, p < .05).

The rate of change in closeness scores over time was predicted by gender (β = −0.08, p < .05; β = 0.01, p < .05; see Table 3). Male children experienced greater decreases in early teacher-reports of closeness than female students, resulting in an increasing gap between males and females toward middle elementary school (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Trajectories of teacher-ratings of closeness with students from kindergarten to sixth grade for male and female children.

Further Analysis of the Effects of Race on Conflict

In order to further explore the effects of race on teacher-ratings of conflict, a follow-up analysis was conducted. A number of three-way interactions were added to the conflict model, along with the original predictors, to examine whether race interacted with gender, academic achievement, maternal education, or mean hours in childcare. When added to the model, none of these four interaction terms were significant (see Figure 4). However, when controlling for these interactions, both the linear and quadratic effects of race on conflict became non-significant, while all other significant findings remained constant. This suggests that the effect of race on conflict scores over time is a function of more complex interactions between race and other variables rather than direct effects of race.

Discussion

The goals of the current study were to (a) examine the stability of teacher-ratings of conflict and closeness from kindergarten to sixth grade; (b) explore average levels of teacher-reported conflict and closeness with students, as well as average changes in the amount of conflict and closeness between teachers and children over time, and (c) to determine what characteristics children bring with them upon school entry that influence the degree to which teachers report conflict and closeness with them in kindergarten and throughout sixth grade.

Stability of Conflict and Closeness

Consistent with our hypotheses, this study found different teacher’s ratings of both conflict and closeness to be moderately stable between kindergarten and sixth grade. There are numerous explanations for why relationship quality is not highly stable over time. First of all, children are forming relationships with different teachers each year, and each relationship with each individual teacher is unique. Children will naturally form better relationships with certain teachers than they will with others, and certain teachers may be better than others at forming high quality relationships with students in general. The level of teacher-perceived conflict in teacher-child relationships showed greater stability over time than did closeness. This finding suggests that different teacher’s perceptions of conflict with a given child are more consistent over the years than are perceptions of closeness. Compared to closeness, levels of conflict may depend more on attributes of the child (e.g., externalizing behavior) than the fluctuating characteristics of teachers and dyadic interactions over the years.

Another possibility is that communication between teachers has an effect on teacher-ratings of conflict and closeness. For example, new teachers may already hold biases toward new students based on information obtained from other teachers. When teachers rate relationship quality, they might take into account not only their own perceptions of students, but also other teachers’ perceptions of those students. It seems reasonable to expect that teachers are most likely to discuss their most problematic students rather then their well-behaved students, which could contribute to greater stability in conflict scores over the years.

General Relationship Trends

Our second hypothesis was that average levels of conflict would increase over time, whereas closeness would ultimately decrease as schools become more focused on academics and less on interactions. As anticipated, average levels of teacher-reported conflict increased between kindergarten and fifth grade, with greater increases in the early years of school. This finding is inconsistent with research that has found modest decreases in conflict between kindergarten and first grade in a smaller sample of children (Pianta & Stuhlman, 2004b). Closeness decreased over the entire seven years, which is consistent with past findings of moderate decline in closeness between kindergarten and first grade (Pianta & Stuhlman, 2004b). This study also found greater decreases in closeness in later years, suggesting that relationships with teachers become exponentially less close as children enter later elementary and middle school.

After fifth grade, both conflict and closeness in teacher-child relationships began to decline. The developmental transition to middle school has been cited as an important and potentially difficult time for children, and may be associated with increased behavioral and relational problems and decreased quality of academic performance (Eccles, Lord, Roeser, Barber, & Jozeforowicz, 1997). Decreasing teacher-perceptions of conflict and closeness may reflect important changes in the nature and function of teacher-child relationships in later school years, such as a greater focus on individual work and more teacher-directed activity. In addition, children begin changing classrooms toward the middle school years, which reduces the amount of contact they have with a single teacher. Eccles and Midgley (1989) note that these changes in the schooling environment during middle school do not coincide with the developmental needs of early adolescents. Having less time to build relationships with children might contribute to less teacher-perceived conflict and closeness during this time (see Eccles & Midgley, 1989), and help to explain the observed decline in both conflict and closeness after fifth grade. Future research examining teacher-child relationship quality into the middle- and high-school years would help to further explain this trend.

Another consideration surrounding changes in conflict and closeness during middle school is the potential lack of communication between elementary and middle school teachers. As discussed above, teachers in an elementary school setting often discuss students with each other, and children who experience conflictual relationships with one teacher are sometimes known throughout the school as a “problem child.” However, as children transition to middle school, it is possible that their elementary school reputation does not follow them as closely, giving them a fresh start with their new teachers. An interesting question for future research would be to examine whether children who remain in the same school for elementary and middle school have more stable levels of relationship quality than do children who switch schools.

Predictors of Relationship Quality

It was hypothesized that children who were male, Black, had mothers with fewer years of education, less sensitive mothers, lower quality home environments, higher maternal ratings of behavior problems and lower academic ability would experience lower initial levels of closeness, higher initial levels of conflict, and less favorable changes in growth over time. In addition, children who spent more time in non-maternal childcare and who had poorer quality attachment relationships with their mothers were expected to have higher initial conflict and less closeness with kindergarten teachers, although we did not expect these variables to continue to effect teacher-child relationship quality past the first few years of school. As expected, male and Black children, children with more hours in non-maternal care, those with lower academic ability, and those with greater behavioral externalizing were rated as having greater conflict with kindergarten teachers. Contrary to expectations, maternal education, maternal sensitivity, hours in non-maternal childcare, behavioral internalizing, and attachment style did not affect teacher-ratings of conflict in kindergarten. Children were rated by teachers as having more close relationships if those children were female, came from higher quality home environments, and had higher levels of academic ability. However, teacher-ratings of closeness were not associated with maternal education, race of the child, maternal sensitivity, hours of non-maternal childcare, behavioral problems, or attachment to mothers.

In general, characteristics and experiences children brought to school were more influential on initial levels of conflict and closeness than on changes in relationship quality over time. This finding suggests that early childhood factors influence initial quality of relationships with teachers more than the rate of change in relationship quality over time. However, if all children grow at the same rate, those who start out with greater conflict or less closeness will end with greater conflict or less closeness as well. In this way, initial relationship quality does influence children beyond kindergarten, even if it does not predict greater rates of growth over time. For example, higher academic achievement scores predicted less initial conflict and greater initial closeness with teachers. Because there were no differences in rate of growth over time for high and low achievers, children who began school with lower achievement scores not only started out with greater conflict and less closeness, but continued to have lower quality relationships with teachers at each time point through sixth grade. However, the finding that early-childhood predictors generally did not predict increasingly deleterious effects on teacher-child relationship quality over time is reassuring. For example, children with lower academic achievement scores did not experience greater increases in conflict or decreases in closeness over time.

Although most variables did not contribute to differential growth in conflict or closeness over time, results did identify a few early childhood characteristics that continue to impact relationship quality over time. For example, the gap between teacher-ratings of conflict between children with mothers with high and low sensitivity increased during the later elementary school years, but then begins to close toward middle school (see Figure 4). There is some evidence that maternal sensitivity is relatively stable across the first few years of development (see Pianta, Sroufe, & Egeland, 1989), however, less is known about the stability of maternal sensitivity beyond the early years. If maternal sensitivity is assumed to remain stable over time, this finding suggests that maternal sensitivity is not as influential on early relationships, but that it may become increasingly influential during certain developmental periods. In addition, gender appears to have a lasting impact on teacher-ratings of closeness with students. Not only do girls start out with higher teacher-ratings of closeness, but the gap between closeness ratings for girls and boys increases over the later elementary school years (see Figure 5). This suggests that, when controlling for all other variables, female students experience more favorable relationships with teachers through sixth grade.

Although most predictors did not influence changes in teacher-child relationship quality over time, the effect of race on growth over time is noteworthy. As hypothesized, children identified by parents as Black not only started kindergarten with higher average teacher-perceptions of conflict, but the gap between teacher ratings of conflict for these children and White children became greater toward the middle elementary school years. Although this gap appears to lessen toward middle school, there remains a larger gap between teacher-ratings of conflict for Black and White children in sixth grade than there was in kindergarten. This suggests that, regardless of other controlled variables, such as maternal education, Black children are perceived as having more conflictual relationships with teachers, and may be at greater risk for increasing conflict in their relationships with teachers throughout elementary school and continuing into middle school. Given strong evidence supporting links between teacher-child relationship quality and academic and social outcomes (Burchinal, Peisner-Feinberg, Pianta, & Howes, 2002; Howes, Hamilton, & Matheson, 1994; Howes, Hamilton, & Philipsen, 1998; Pianta, La Paro, Payne, Cox, & Bradley, 2002; Pianta, Nimetz, & Bennett, 1997), having greater levels of conflict with teachers may be one factor helping to explain consistent findings of achievement gaps between Black and White children (see Berlack, 2005). It is important to note that this sample was comprised of predominately Caucasian teachers, and the small number of minority teachers did not allow us to examine the effects of ethnic match/mismatch on teacher-child relationship quality. Some research suggests that African American teachers perceive less conflict with students (Saft & Pianta, 2001), though these findings are not consistent (Hamre, Pianta, Downer, & Mashburn, in press).

In order to further explore the findings for Black children, a number of three-way interactions were added to the conflict model (see Tables 4–8). These interactions were designed to explore whether the effect of race on conflict was different for Black children who were male versus female, were high versus low achievers, had high versus low maternal ratings of behavior problems, and for Black children who had higher versus lower levels of maternal education or greater versus fewer hours in non-maternal childcare. Each interaction was added to the conflict model individually, controlling for all previous predictors. None of the three-way interactions was significant, and they did not significantly alter the overall model. This means that even when controlling for possible interactions, differences between teacher-ratings of conflict for Black and White students remained. This suggests that differences between teacher-ratings of Black and White children appear to exist for all Black children, regardless of their academic achievement, gender, behavioral problems, maternal sensitivity, maternal education, or time spent in non-maternal childcare. This finding is concerning, and poses important questions for future research. Research exploring teacher-child relationships in a more diverse sample, particularly in terms of teacher ethnicity and overall school composition, could yield important information on factors that contribute to higher teacher-ratings of conflict for Black children.

Table 4.

Follow-up Model for Conflict Including Interaction Between Race and Gender (N=878)

| Conflict | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.17*** | ||

| (0.35) | |||

| Time | 0.05 | ||

| (0.24) | |||

| Time * Time | 0.03 | ||

| (0.04) | |||

| Intercept | Linear | Quadratic | |

| Maternal Education | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.00 |

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.00) | |

| Gender | 0.17*** | 0.05 | −0.01 |

| (0.05) | (0.03) | (0.01) | |

| Black | 0.22** | 0.15** | −0.02* |

| (0.09) | (0.06) | (0.01) | |

| Hispanic | −0.07 | 0.03 | −0.00 |

| (0.09) | (0.07) | 0.01 | |

| Maternal Sensitivity @ 54 months | −0.03 | −0.06* | 0.01* |

| (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.01) | |

| HOME Score @ 54 Months | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.00 |

| (0.01) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Mean Hours Child Care up to 54 months | 0.01*** | −0.00 | −0.00 |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Academic Achievement Scores @ 54 months | −0.01** | 0.00 | −0.00 |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Mother Report Behavioral Internalizing @ 54 months | −0.01 | −0.00 | 0.00 |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Mother Report Behavioral Externalizing @ 54 months | 0.02*** | 0.00 | −0.00 |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Avoidant Attachment Classification | 0.04 | −0.07 | 0.01 |

| (0.07) | (0.05) | (0.01) | |

| Resistant Attachment Classification | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.01 |

| (0.08) | (0.05) | (0.01) | |

| Disorganized Attachment Classification | 0.08 | −0.05 | 0.01 |

| 0.06 | (0.04) | (0.01) | |

| Interaction: Race* Gender* Time | 0.01 | ||

| (0.02) | |||

= p < .05

= p < .01

= p < .001

Table 8.

Follow-up Model for Conflict Including Interaction Between Race and Behavioral Externalizing (N=878)

| Conflict | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.17*** | ||

| (0.35) | |||

| Time | 0.05 | ||

| (0.24) | |||

| Time * Time | 0.03 | ||

| (0.04) | |||

| Intercept | Linear | Quadratic | |

| Maternal Education | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.00 |

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.00) | |

| Gender | 0.17*** | 0.05 | −0.01 |

| (0.05) | (0.03) | (0.01) | |

| Black | 0.22** | 0.13 | −0.02* |

| (0.09) | (0.08) | (0.01) | |

| Hispanic | −0.07 | 0.03 | −0.00 |

| (0.09) | (0.07) | 0.01 | |

| Maternal Sensitivity @ 54 months | −0.03 | −0.06* | 0.01* |

| (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.01) | |

| HOME Score @ 54 Months | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.00 |

| (0.01) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Mean Hours Child Care up to 54 months | 0.01*** | −0.00 | −0.00 |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Academic Achievement Scores @ 54 months | −0.01** | 0.00 | −0.00 |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Mother Report Behavioral Internalizing @ 54 months | −0.01 | −0.00 | 0.00 |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Mother Report Behavioral Externalizing @ 54 months | 0.02*** | 0.00 | −0.00 |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Avoidant Attachment Classification | 0.04 | −0.07 | 0.01 |

| (0.07) | (0.05) | (0.01) | |

| Resistant Attachment Classification | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.01 |

| (0.08) | (0.05) | (0.01) | |

| Disorganized Attachment Classification | 0.08 | −0.05 | 0.01 |

| 0.06 | (0.04) | (0.01) | |

| Interaction: Race* Behavioral Externalizing* Time | 0.00 | ||

| (0.00) | |||

= p < .05

= p < .01

= p < .001

One of the more surprising findings of this study, and one that did not support our hypotheses, is that the type of attachment style that children form with their mothers is not predictive of teacher-perceptions of either conflict or closeness in kindergarten. Given that parent-child attachment style is believed to heavily influence other child-adult relationships (e.g., Howes et al., 1998), it is surprising that attachment did not predict teacher-child relationship quality. One explanation for this finding is that children have formed a number of relationships with different adults prior to school entry (e.g., fathers, extended family members, childcare providers, etc) and it is possible that the additive effect of these relationship qualities would be a better predictor of teacher-child relationship quality than maternal attachment alone. Unfortunately, few children in our sample had data on relationship quality with non-maternal caregivers, and we were unable to evaluate this hypothesis. This finding is reassuring in that it supports the theory that children with poor maternal attachment are not necessarily predisposed to poor quality relationships throughout the rest of their lives. This may be particularly important when evaluating teacher-child relationship quality, as high quality relationships with teachers may attenuate some of the risk involved with poor early child-caregiver relationships. Additional research is needed in this area to identify specific ways in which child-adult relationships can ameliorate or worsen the effects of poor maternal attachment on later relationships, and whether there are certain ages at which positive relationships are especially valuable for child development.

Limitations and Conclusions

A number of limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. First, this study used teacher-reports of relationship quality as opposed to observed or student-report measures. While this method captures consistent trends in individual students across teachers, it does not account for varying teacher characteristics or the child’s perception of relationships. Future studies that utilize observational and student-report measures would be beneficial to our understanding of teacher-child relationships. Second, in this study all predictors were measured prior to 54 months, and we did not explore how changing child characteristics might influence teacher-child relationship quality over time. For example, if academic ability increases over time, later relationships with teachers may improve as well. The addition of time-varying covariates, such as academic ability and teacher characteristics would be beneficial in future research. A third consideration is the composition of this sample. Participants in this study were predominantly White families with relatively high socioeconomic status, and this sample should not be considered characteristic of a high risk sample. The low percentage of minority children and teachers prevented us from exploring issues such as the effects of ethnic match between teachers and children on outcomes. High risk, low-income, or minority status families may present much differently, and cultural and economic considerations in the formation of relationships with teachers should be explored further. Finally, due to the limited number of children with data on early caregiver relationship quality, this variable was not included in this study. It would be interesting to examine whether having a high quality relationship with an early non-maternal caregiver predicts differences in later teacher-child relationship quality.