Abstract

Background

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) is a well-established imaging modality for a wide variety of solid malignancies. Currently, only limited data exists regarding the utility of PET/CT imaging at very extended injection-to-scan acquisition times. The current retrospective data analysis assessed the feasibility and quantification of diagnostic 18F-FDG PET/CT oncologic imaging at extended injection-to-scan acquisition time intervals.

Methods

18F-FDG-avid lesions (not surgically manipulated or altered during 18F-FDG-directed surgery, and visualized both on preoperative and postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging) and corresponding background tissues were assessed for 18F-FDG accumulation on same-day preoperative and postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging. Multiple patient variables and 18F-FDG-avid lesion variables were examined.

Results

For the 32 18F-FDG-avid lesions making up the final 18F-FDG-avid lesion data set (from among 7 patients), the mean injection-to-scan times of the preoperative and postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT scans were 73 (±3, 70-78) and 530 (±79, 413-739) minutes, respectively (P < 0.001). The preoperative and postoperative mean 18F-FDG-avid lesion SUVmax values were 7.7 (±4.0, 3.6-19.5) and 11.3 (±6.0, 4.1-29.2), respectively (P < 0.001). The preoperative and postoperative mean background SUVmax values were 2.3 (±0.6, 1.0-3.2) and 2.1 (±0.6, 1.0-3.3), respectively (P = 0.017). The preoperative and postoperative mean lesion-to-background SUVmax ratios were 3.7 (±2.3, 1.5-9.8) and 5.8 (±3.6, 1.6-16.2), respectively, (P < 0.001).

Conclusions

18F-FDG PET/CT oncologic imaging can be successfully performed at extended injection-to-scan acquisition time intervals of up to approximately 5 half-lives for 18F-FDG while maintaining good/adequate diagnostic image quality. The resultant increase in the 18F-FDG-avid lesion SUVmax values, decreased background SUVmax values, and increased lesion-to-background SUVmax ratios seen from preoperative to postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging have great potential for allowing for the integrated, real-time use of 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging in conjunction with 18F-FDG-directed interventional radiology biopsy and ablation procedures and 18F-FDG-directed surgical procedures, as well as have far-reaching impact on potentially re-shaping future thinking regarding the “most optimal” injection-to-scan acquisition time interval for all routine diagnostic 18F-FDG PET/CT oncologic imaging.

Keywords: 18F-FDG, PET/CT, SUVmax, Injection-to-scan acquisition time, Delayed imaging, Lesion-to-background ratio, Tumor-to-background ratio, 18F-FDG-directed surgery, Real-time, Oncologic

Background

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) is a well-established imaging modality for a wide variety of solid malignancies [1-5]. Its utilities have included initial cancer diagnostics, staging, restaging, therapy planning, therapy response monitoring, surveillance, and cancer screening for at-risk populations. Beyond these utilities, there has been growing interest in evaluating the feasibility of utilizing 18F-FDG and PET/CT technology for providing real-time information within the operative room and perioperative arena [6-62].

As part of an effort to provide surgeons with improved intraoperative tumor localization and image-based verification of completeness of resection, our collaborative group at The Ohio State University has previously described a novel, multimodal imaging and detection strategy involving perioperative patient and ex vivo surgical specimen 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging performed in combination with intraoperative 18F-FDG gamma detection [51]. As part of this schema, patients could undergo both a same-day preoperative diagnostic whole-body 18F-FDG PET/CT and a same-day postoperative diagnostic limited field-of-view 18F-FDG PET/CT, utilizing a single preoperative dose of 18F-FDG. This has provided our group with a unique dual-set of diagnostic 18F-FDG PET/CT images, in which the initial same-day preoperative diagnostic whole-body 18F-FDG PET/CT images were acquired within the injection-to-scan acquisition time interval generally recommended for diagnostic whole-body 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging [63], and in which the second set of same-day diagnostic limited field-of-view 18F-FDG PET/CT images were acquired after the completion of the surgical procedure, once the patient had completed standard postoperative recovery in the post-anesthesia care unit. This second set of same-day diagnostic limited field-of-view 18F-FDG PET/CT images was highly dependent upon the length of the surgical procedures performed, thus creating injection-to-scan acquisition time intervals for that second set of same-day diagnostic limited field-of-view 18F-FDG PET/CT images at time points far beyond what is generally described.

The current retrospective data analysis was undertaken to examine 18F-FDG-avid lesions and corresponding background tissues on same-day preoperative and postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT scans to assess the feasibility and quantification of diagnostic 18F-FDG PET/CT oncologic imaging at extended injection-to-scan acquisition time intervals. Herein, we have: (1) demonstrated the ability to acquire diagnostic quality images at extended injection-to-scan acquisition times; (2) identified and quantified the amount of 18F-FDG accumulation in 18F-FDG-avid lesions and in corresponding background tissues at these extended injection-to-scan acquisition times; and (3) compared the amount of 18F-FDG accumulation in 18F-FDG-avid lesions and in corresponding background tissues at these extended injection-to-scan acquisition times to that of the corresponding injection-to-scan acquisition time interval generally recommended for diagnostic whole-body 18F-FDG PET/CT oncologic imaging.

Methods

All aspects of the current retrospective analysis were approved by the Cancer Institutional Review Board (IRB) at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. The data for the current retrospective analysis were acquired from a master prospectively-maintained database (with database inclusion dates from June 2005 to June 2012), which were generated from the combination of several Cancer IRB-approved protocols, and which involved a multimodal imaging and detection approach to 18F-FDG-directed surgery for the localization and resection of 18F-FDG-avid lesions in patients with known and suspected malignancies. Depending upon the clinical scenario, these 18F-FDG-directed surgical procedures were performed with either the intent for curative resection, for palliation, or for making a definitive tissue diagnosis, as based upon the standard of care management for any given disease presentation.

All patients who were eligible to be included in this current retrospective analysis consisted of those individuals who: (1) received a same-day single-dose preoperative intravenous injection of 18F-FDG; (2) underwent same-day preoperative diagnostic whole-body 18F-FDG PET/CT scan (usually consisting of 6 to 8 field-of-view PET bed positions, and with 2 minutes of PET imaging for each field-of-view PET bed position); (3) proceeded to the operating room for their anticipated surgical procedure and completed standard postoperative recovery in the post-anesthesia care unit; and (4) underwent a same-day postoperative diagnostic limited field-of-view 18F-FDG PET/CT scan (which was limited only to the immediate area of the surgical resection field, usually consisting of 1 to 3 field-of-view PET bed positions, in order to limit overall patient radiation exposure for the CT portion of the PET/CT, and with 10 minutes of PET imaging for each field-of-view PET bed position). All patients fasted for a minimum of 6 hours before undergoing the same-day preoperative diagnostic whole-body 18F-FDG PET/CT scan. Only a single intravenous dose of 18F-FDG was used on the day of surgery, and was attempted to be administered approximately 75 minutes prior to the planned time of the same-day preoperative diagnostic whole-body 18F-FDG PET/CT scan, which was performed within the time frame recognized by the Society of Nuclear Medicine for 18F-FDG PET/CT image acquisition [63]. The 18F-FDG PET/CT images were acquired on one of three clinical diagnostic scanners: (1) Siemens Biograph 16 (Siemens, Knoxville, Tennessee); (2) Phillips Gemini TF (Philips, Amsterdam, Netherlands); and (3) Siemens Biograph mCT (Siemens, Knoxville, Tennessee). Only those patients with 18F-FDG-avid lesions seen on both same-day preoperative diagnostic whole-body 18F-FDG PET/CT scan and same-day postoperative diagnostic limited field-of-view 18F-FDG PET/CT scan were used in the current retrospective analysis. For any individual patient, the same-day preoperative diagnostic whole-body 18F-FDG PET/CT scan and same-day postoperative diagnostic limited field-of-view 18F-FDG PET/CT scan were performed on the same clinical diagnostic scanner.

The same-day preoperative diagnostic whole-body 18F-FDG PET/CT images and same-day postoperative diagnostic limited field-of-view 18F-FDG PET/CT images were evaluated by two nuclear medicine physicians who were initially blinded to all clinical information related to each set of preoperative and postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT images. The two nuclear medicine physician readers first judged the quality of the preoperative and postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT images as either being of diagnostic image quality or of non-diagnostic image quality, based upon criteria that were previously reported [64]. The two readers evaluated each set of preoperative and postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT images for identification of all 18F-FDG-avid lesions that were considered suspicious for or consistent with malignancy. The location and maximum standard uptake value (SUVmax) of each 18F-FDG-avid lesion were recorded. Likewise, a corresponding background SUVmax was obtained either from (1) an area of tissue deemed as normal within the same organ as the 18F-FDG-avid lesion; (2) an area of tissue deemed as normal in a location adjacent to the 18F-FDG-avid lesion; or (3) within a single area of tissue deemed as normal elsewhere within the body when multiple 18F-FDG-avid lesions were being evaluated in an individual case. The corresponding background SUVmax values were taken from the same location on both the preoperative and postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT scans. Finally, the two readers were given access to the operative report for each case corresponding to each preoperative and postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT images data set, in order to determine which 18F-FDG-avid lesions had been: (1) completely surgically resected; (2) partially surgically resected or biopsied; or (3) not surgically manipulated or altered (i.e., intentionally left in situ within the patient at the time of the 18F-FDG-directed surgical procedure). The 18F-FDG PET/CT images were all analyzed/processed on a Philips Extended Brilliance Work Station (Philips, Amsterdam, Netherlands).

All continuous variables were expressed as mean (±SD, range). The software program IBM SPSS® 21 for Windows® (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois) was used for the data analysis. All mean value comparisons for continuous variables (including the comparisons for 18F-FDG-avid lesion SUVmax values, background SUVmax values, and lesion-to-background SUVmax ratios) from the preoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT image group and the postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT image group were performed by using the 2-tailed paired samples t-test. All categorical variable comparisons were made using 2 × 2 contingency tables that were analyzed by either the Pearson chi-square test or the Fisher exact test, when appropriate. P-values determined to be 0.05 or less were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Derivation of the final 18F-FDG-avid lesion data set

From a total of 166 patients who gave consent to participate in one of the IRB-approved protocols, a total of 157 patients were taken to the operating room for 18F-FDG-directed surgery. A total of 31 of the 157 patients underwent both a same-day preoperative diagnostic whole-body 18F-FDG PET/CT scan and a same-day postoperative diagnostic 18F-FDG PET/CT scan utilizing a single same-day preoperative intravenous injection of 18F-FDG.

These 31 sets of preoperative and postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT images were evaluated by two nuclear medicine physicians for determination of diagnostic image quality versus non-diagnostic image quality. All of the 31 preoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging studies were determined to be of diagnostic image quality. A total of 5 of the 31 postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging studies were determined to be of non-diagnostic image quality. The average injection-to-scan time for these 5 postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT studies with non-diagnostic image quality was of significantly longer duration, at 719 minutes (±90, 612-853), as compared to 530 minutes (±79, 413-739) for the remaining 26 postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT studies with diagnostic image quality (P < 0.001), suggesting that the finding of non-diagnostic image quality on a postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT scan was a direct consequence of any given postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT scan being performed at the extreme outer-limit of the extended injection-to-scan acquisition time interval. No other 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging variables or any patient variables were significantly different for the postoperative non-diagnostic image quality group as compared to the postoperative diagnostic image quality group.

From the 26 remaining matching sets of preoperative and postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT studies that were determined to be of diagnostic image quality, a total of 87 individual 18F-FDG-avid lesions were identified on the preoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT images. There were 30 18F-FDG-avid lesions identified on the preoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT images that were completely surgical resected, 10 18F-FDG-avid lesions that were partially surgically resected or biopsied, and 12 18F-FDG-avid lesions were not within the field of view that was utilized on the postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT images (as the postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT scan was performed in a limited fashion to only to the bed of the surgical resection field). Therefore, these 52 of the original 87 individual 18F-FDG-avid lesions identified on the preoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT images were not considered for further data analysis.

The remaining 35 18F-FDG-avid lesions identified on the preoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT images were determined to represent preoperative 18F-FDG-avid lesions that had not been surgically manipulated and were left in situ within the patient at the time of the surgical procedure, and were within the field of view on the postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT images. There were 3 of these remaining 35 preoperative 18F-FDG-avid lesions that were not 18F-FDG-avid on the postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT images. Of the 3 preoperative 18F-FDG-avid lesions not found to be 18F-FDG-avid on the postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT images, 2 preoperative 18F-FDG-avid lesions were located within the bilateral tonsils in a patient who was later confirmed to have recurrent thyroid cancer within the mediastinum, but without any evidence of metastatic spread to the tonsils. These 2 areas of preoperative mild focal 18F-FDG-avidity seen within the bilateral palatine tonsils (SUVmax 4.3 on the left and 4.0 on the right), but not found to be 18F-FDG-avid on the postoperative PET/CT images, were determined to be secondary to nonmalignant inflammation, a well-known pitfall of diagnostic 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging of the tonsillar region. The third preoperative 18F-FDG-avid lesion was located within the stomach region of a patient with diffuse metastatic serous ovarian cancer. This area of preoperative focal 18F-FDG-avidity seen within the stomach region (SUVmax 10.0), but not found to be 18F-FDG-avid on the postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT images, has not been further evaluated to date secondary to the lack of performance of any subsequent follow-up diagnostic 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging. As such, these 3 18F-FDG-avid lesions were not considered for further data analysis. In the end, a total of 32 of the original 87 individual 18F-FDG-avid lesions identified on the preoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT images were considered as the final 18F-FDG-avid lesion data set for the current retrospective data analysis comparing the preoperative and postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT images. The region of the body in which these 32 18F-FDG-avid lesions were located was designated as the thorax for 12 lesions, abdomen/pelvis for 11 lesions, neck for 5 lesions, and axilla for 4 lesions.

Patient variables

The 32 18F-FDG-avid lesions, constituting the final 18F-FDG-avid lesion data set, originated from a total 7 patients (5 females and 2 males) from among the initial group of 31 patients who had undergone both a same-day preoperative diagnostic whole-body 18F-FDG PET/CT scan and a same-day postoperative diagnostic 18F-FDG PET/CT scan. For those 7 patients, the mean patient age was 65 (±12, 43-80) years, the mean patient weight was 80.3 (±28.1, 56.7-136.1) kilograms, the mean preoperative blood glucose level of 103 (±15, 82-121) milligrams/deciliter, and the mean intravenous 18F-FDG dose used on the day of surgery was 559 (±104, 437-755) megabecquerels. A histologic diagnosis of malignancy was known to be lymphoma in 3 cases, colorectal carcinoma in 2, breast carcinoma in 1, and ovarian carcinoma in 1.

Preoperative and postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT scan variables for the 32 18F-FDG-avid lesions and corresponding background areas

For the 32 18F-FDG-avid lesions, the mean injection-to-scan times of the preoperative and postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT scans were 73 (±3, 70-78) minutes and 530 (±79, 413-739) minutes, respectively (P < 0.001). The preoperative and postoperative mean 18F-FDG-avid lesion SUVmax values were 7.7 (±4.0, 3.6-19.5) and 11.3 (±6.0, 4.1-29.2), respectively (P < 0.001). The preoperative and postoperative mean background SUVmax values were 2.3 (±0.6, 1.0-3.2) and 2.1 (±0.6, 1.0-3.3), respectively (P = 0.017). The preoperative and postoperative mean lesion-to-background SUVmax ratios were 3.7 (±2.3, 1.5-9.8) and 5.8 (±3.6, 1.6-16.2), respectively, (P < 0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Preoperative and postoperative 18FDG PET/CT scan variables for the 32 18F-FDG-avid lesions and corresponding background areas

| Variable | Preoperative scan value | Postoperative scan value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Injection-to-scan time (minutes) |

73 (±3, 70-78) |

530 (±79, 413-739) |

<0.001 |

|

18F-FDG-avid lesion SUVmax |

7.7 (±4.0, 3.6-19.5) |

11.3 (±6.0, 4.1-29.2) |

<0.001 |

|

Background SUVmax |

2.3 (±0.6, 1.0-3.2) |

2.1 (±0.6, 1.0-3.3) |

0.017 |

| Lesion-to-background SUVmax ratio | 3.7 (±2.3, 1.5-9.8) | 5.8 (±3.6, 1.6-16.2) | <0.001 |

All variables are expressed as mean (±SD, range).

Abbreviations:18F-FDG 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose, PET/CT positron emission tomography/computed tomography, SUVmax maximum standard uptake value.

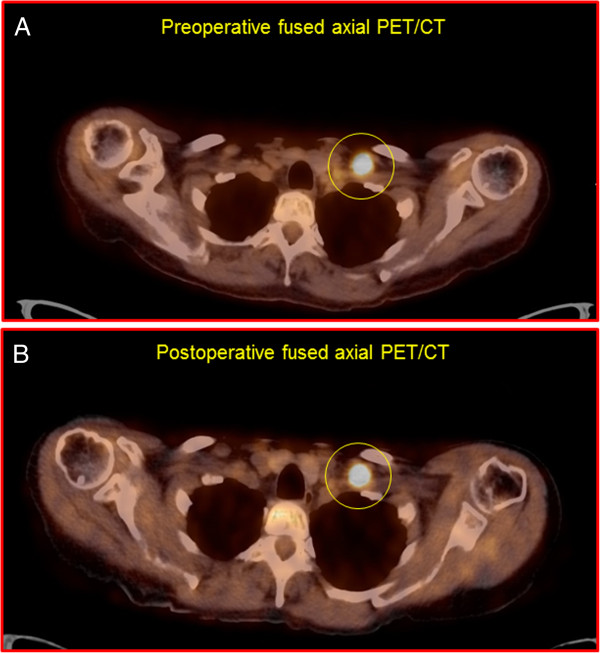

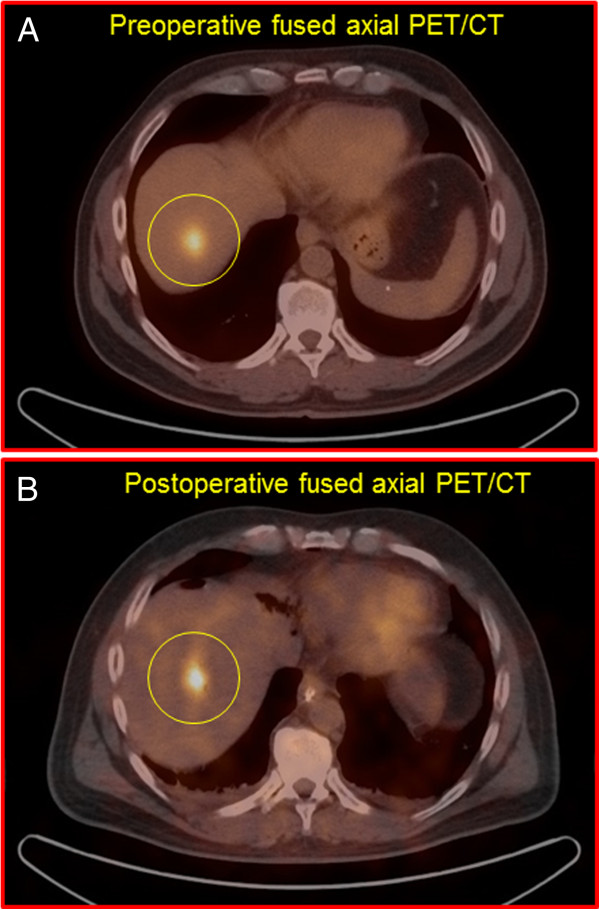

Two representative example cases of an 18F-FDG-avid lesion seen on both same-day preoperative diagnostic whole-body 18F-FDG PET/CT scan and same-day postoperative diagnostic limited field-of-view 18F-FDG PET/CT scan are shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

A representative example of an 18 F-FDG-avid lesion in the left supraclavicular region (shown within the yellow circle) as seen on both same-day preoperative diagnostic whole-body 18 F-FDG PET/CT scan (panel A; SUV max of 16.7 at 70 minutes post-injection of 455 megabecquerels of 18 F-FDG) and same-day postoperative diagnostic limited field-of-view 18 F-FDG PET/CT scan (panel B; SUV max of 20.5 at 494 minutes post-injection of 18 F-FDG) in a patient with metastatic ovarian carcinoma.

Figure 2.

A representative example of an 18 F-FDG-avid lesion in the right hepatic lobe of the liver (shown within the yellow circle) as seen on both same-day preoperative diagnostic whole-body 18 F-FDG PET/CT scan (panel A; SUV max of 8.2 at 73 minutes post-injection of 585 megabecquerels of 18 F-FDG) and same-day postoperative diagnostic limited field-of-view 18 F-FDG PET/CT scan (panel B; SUV max of 9.8 at 688 minutes post-injection of 18 F-FDG) in a patient with metastatic colorectal carcinoma.

Of the 32 18F-FDG-avid lesions examined, only 1 18F-FDG-avid lesion demonstrated a reduction in the lesion-to-background SUVmax ratio from the preoperative to the postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT images. This particular 18F-FDG-avid lesion was located in the ascending colon of a patient with colorectal carcinoma, having a preoperative 18F-FDG-avid lesion SUVmax of 7.9 (with a preoperative background SUVmax of 1.0) and a postoperative 18F-FDG-avid lesion SUVmax of 7.5 (with a postoperative background SUVmax of 1.2), resulting in a change in the lesion-to-background SUVmax ratio of -1.7 from the preoperative to the postoperative study. Interestingly, on a subsequent follow-up diagnostic whole-body 18F-FDG PET/CT scan performed 9 months after 18F-FDG-directed surgery, the same area of this particular former 18F-FDG-avid lesion in the ascending colon was no longer characterized as 18F-FDG-avid, demonstrating a SUVmax of 2.1 (with a background SUVmax of 1.7).

For the 32 18F-FDG-avid lesions, the corresponding background SUVmax values were taken from contralateral axillary region (n = 13), normal mediastinum (n = 10), contralateral supraclavicular region (n = 4), normal adjacent liver parenchyma (n = 2), hepatic flexure (n = 1), descending colon (n = 1), and adjacent normal spleen (n = 1).

Discussion

The results of the current retrospective data analysis, comparing preoperative and postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging for 32 individual 18F-FDG-avid lesions (not surgically manipulated or altered during 18F-FDG-directed surgery, and for which all such 18F-FDG-avid lesions were visualized on both preoperative and postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging), yielded several very important observations. First, 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging performed at extended injection-to-scan acquisition times of up to a mean time of 530 minutes (i.e., approximately 5 half-lives for 18F-FDG) was able to maintain a designation of good/adequate diagnostic image quality deemed necessary for clinical interpretation. Second, the mean 18F-FDG-avid lesion SUVmax value increased significantly from preoperative to postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging (7.7 to 11.3; P < 0.001). Third, mean background SUVmax value decreased significantly from preoperative to postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging (2.3 to 2.1; P = 0.017). Fourth, the mean lesion-to-background SUVmax ratio increased significantly from preoperative to postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging (3.7 to 5.8; P < 0.001). These collective observations from our current analysis have potential far-reaching implications regarding the currently held premises related to 18F-FDG PET/CT oncologic imaging.

Multiple investigators [65-169] have evaluated the concepts of delayed phase and dual-time-point diagnostic 18F-FDG PET imaging approaches. In these numerous studies, attempts have been made to qualify and quantify the impact of the length of the injection-to-scan time interval on differentiating malignant processes from benign processes. As one might expect, the findings reported amongst these various investigators have been highly variable, with some supporting the use of delayed phase and dual-time-point diagnostic 18F-FDG PET imaging approaches [66-77,81-84,86,87,91-93,95-100,103-108,110,111,113,114,117-122,124-128,131,133,134,136,138,141,143,146,149,152,153,155,157,160-163,165,167,169], and with others not [65,78,89,90,94,101,102,109,115,116,123,129,130,132,135,137,139,140,147,148,150,151,156,158,164,166,168].

The inherent difference in intracellular glucose-6-phosphatase levels, as it relates to benign cells and tumor cells, can be used to support the notion that the delayed phase and dual-time-point diagnostic 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging approaches are advantageous [36,100,111,154,159,170-176]. Initially, benign cells, such as in the case of inflammatory processes, may appear hypermetabolic as they transport increased number of glucose molecules into their cytoplasm. However, the glucose is not indefinitely retained secondary to the fact that those benign cells contain normal levels of intracellular glucose-6-phosphatase, thus allowing glucose molecules to subsequently exit the cytoplasm of those cells via glucose transporter membrane proteins. On the other hand, tumor cells have decreased levels of intracellular glucose-6-phosphatase, thus allowing for a continuous accumulation of 18F-FDG into tumor cell over time. Therefore, methodologies that use a delayed phase in their diagnostic 18F-FDG PET imaging approach should allow for an expected gradual decline in intracellular 18F-FDG retention within initially hypermetabolic-appearing benign tissues as compared to the continued accumulation of intracellular 18F-FDG within malignant tissues [100,111,154,159].

Nevertheless, there are several reasons why the notion that delayed phase and dual-time-point diagnostic 18F-FDG PET imaging approaches are advantageous may not be so simple and clear cut. First, it is well-recognized that there can be a significant degree of overlap in the pattern of 18F-FDG uptake between benign tissues and various malignant tissues [154,159]. Second, there are substantial inherent variations in the methodology used in various delayed phase and dual-time-point diagnostic 18F-FDG PET imaging protocols from institution to institution, with great variability in the timing of the initial scan and the delayed scan, as well as a general paucity of data where the delayed scan is performed at very extended injection-to-scan acquisition time intervals after the initial time of 18F-FDG injection. Collectively, the vast majority of the reported series within the literature performed their delayed scan within approximately 1.5 to 2.5 hours from the initial time of 18F-FDG injection [65,67,70-74,79,82,83,85-93,97-100,102-104,106,107,109,110,112,113,115-127,129-135,137-143,145-169], and with far fewer series reporting their delayed scan at injection-to-scan acquisition times of approximately 3 hours or more from the initial time of 18F-FDG injection [66,68,69,75-78,80,81,84,94-96,101,105,108,111,114,128,136,144].

There are 5 groups of investigators, Lodge et al. in 1999 [68], Spence et al. in 2004 [81], Basu et al. in 2009 [111], Horky et al. in 2011 [136], and Prieto et al. in 2011 [144], who all performed delayed phase diagnostic 18F-FDG PET imaging at ultra-extended injection-to-scan acquisition time intervals, for which their clinical findings are particularly noteworthy of further discussion.

As pertaining specifically to 18F-FDG PET imaging for brain tumors, there have been 3 clinical series that have reported successful delayed imaging extending out to ultra-extended injection-to-scan acquisition time intervals [81,136,144]. Spence et al. reported dual-time-point diagnostic 18F-FDG PET imaging in various brain tumors with a median time of 5.4 hours (range of 2.9 to 9.4 hours) after 18F-FDG injection for the delayed scan in a series of 25 patients [81]. Prieto et al. reported dual-time-point diagnostic 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging in gliomas with a range of 180 to 480 minutes after 18F-FDG injection for the delayed scan in a series of 19 patients [144]. In both series [81,144], they reported better tumor identification and delineation, and advocated the use of delayed intervals imaging. Horky et al. reported dual-time-point diagnostic 18F-FDG PET imaging in patients treated with radiation for brain metastases, with delayed scans performed at a mean time of 225 minutes (range of 118 to 343 minutes) after the early scan done at 45 to 60 minutes after 18F-FDG injection in a series of 32 patients [136]. They found that although the early and late SUVmax values of the lesions alone did not differentiate residual tumor from post-radiation necrosis, the change in the lesion-to-gray matter early SUVmax ratio to late SUVmax ratio did.

Along similar lines for 18F-FDG PET imaging of soft tissues masses, Lodge et al. reported a series of 29 patients in which a 6-hour 18F-FDG PET imaging protocol was used [68]. In this protocol, a 2-hour dynamic emission data acquisition was performed after 18F-FDG administration, followed by 2 further 30-minute static scans, which were started at 4 hours and 6 hours after 18F-FDG administration. They found that the SUV value for high-grade sarcomas increased with time, reaching a peak SUV value at approximately 4 hours after initial 18F-FDG administration, while benign soft tissue lesions reached a maximum SUV value within approximately 30 minutes after initial 18F-FDG administration. They concluded that improved differentiation of high-grade sarcomas from benign soft tissue lesions was aided by SUV values derived from delayed intervals imaging.

Likewise, for 18F-FDG PET imaging of non-small cell lung cancer, Basu et al. reported on 3 patients in whom an 8-hour 18F-FDG PET imaging protocol was used [111]. In this protocol, 18F-FDG PET imaging was performed, starting at 5 minutes, and continuing at 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 hours after initial 18F-FDG administration. They found that sites of non-small cell lung cancer showed a progressive increase in 18F-FDG uptake over the 8-hour course, while surrounding normal tissues demonstrated either a declining or stable pattern of 18F-FDG uptake with time. They concluded that delayed injection-to-scan acquisition time intervals had “implications in detecting malignant lesions with greater degree of certainty”…“due to better contrast between the abnormal site and the surrounding background”.

Of last mention, similar recommendations for the use of delayed injection-to-scan acquisition time interval imaging have been made by other investigators at somewhat less extended injection-to-scan acquisition time intervals of approximately 3 hours in breast cancer [66,105,128], cervical cancer [76,77], hepatocellular cancer [84], biliary malignancies [95], lung cancer [75,96,108], and thymic epithelial tumors [114].

The results of the previously reported series demonstrating their ability to successfully perform delayed imaging at extended injection-to-scan acquisition time intervals of approximately 3 hours or more from the initial time of 18F-FDG injection [66,68,69,75-78,80,81,84,94-96,101,105,108,111,114,128,136,144], as well as those demonstrating the added value to performing delayed imaging at extended injection-to-scan acquisition time intervals of approximately 3 hours or more from the initial time of 18F-FDG injection [66,68,75-77,81,84,95,96,105,108,111,114,128,136,144], are all highly consistent with the results of our current retrospective data analysis. It is clear that our currently presented data, demonstrating increasing 18F-FDG-avid lesion SUVmax values, decreasing background SUVmax values, and increasing lesion-to-background SUVmax ratios from preoperative to postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging, supports the potential utility of delayed phase and dual-time-point diagnostic 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging. This suggests that delayed scans performed at an appropriately selected extended injection-to-scan acquisition times can potentially minimize or alleviate the issue of overlap in the pattern of 18F-FDG uptake between benign tissues versus malignant tissues, as well as between background tissues versus malignant tissues. This phenomenon appears to be the temporal outcome of a resultant gradual accumulation of 18F-FDG within malignant tissues and continued decreased background level of 18F-FDG within the surrounding normal tissues, thus leading to a progressive increase in the lesion-to-background SUVmax ratio. A key element to this overall line of reasoning, as it relates to the proper use of 18F-FDG in molecular imaging, is the recognition of the negative impact of “background” issues, and “not signal”, as recently eloquently described by Frangioni [177], but which was recognized early on in the evolution of PET imaging by Hoffman and Phelps [178]. This time-dependent phenomenon observed in our current retrospective analysis is consistent with our previously reported findings regarding same-day preoperative diagnostic whole-body 18F-FDG PET/CT images and same-day perioperative ex vivo surgical specimen 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging, in which we observed similar trends of increased 18F-FDG accumulation in 18F-FDG-avid lesions within ex-vivo surgical specimens and of decreased 18F-FDG activity within adjacent normal tissues [37]. However, we fully acknowledge and recognize that significant further investigations are warranted to better assess this phenomenon and to formally evaluate the clinical usefulness of extended injection-to-scan acquisition time intervals in various diagnostic 18F-FDG PET/CT oncologic imaging applications.

Analogous to our current discussions regarding the evaluation and quantification of 18F-FDG-avid lesions and corresponding background tissues at these extended injection-to-scan acquisition time intervals for 18F-FDG PET imaging approaches, there have been two groups of investigators utilizing 18F-FDG-directed surgery [11,17,21], other than our own collaborative group [51], who have previously examined the equivalent question as it pertains to the impact of the length of time from injection of 18F-FDG to the performance of intraoperative gamma detection probing [11,17,21]. One such group [17,21] recognized that there was an increased tumor-to-background ratio of 18F-FDG seen during intraoperative gamma detection probing when there was a longer duration (i.e., up to 6 hours of time) from injection of the 18F-FDG dose to intraoperative probing. However, they did not endorse lengthening the duration from injection of the 18F-FDG dose to performing intraoperative gamma detection probing or to performing perioperative 18F-FDG PET imaging [21]. Instead, they specifically commented that lengthening the duration from injection of the 18F-FDG dose “might compromise image quality as a result of lower count rates” [21]. The other such group [11], as based upon the evaluation of 18F-FDG count rates for only three patients, concluded that intraoperative gamma detection probing was “more suitable” at 1 to 3 hours post-injection of 18F-FDG as compared to 6 to 7 hours post-injection of 18F-FDG. In both instances, these two groups of investigators fell short of recognizing the potential efficacies of extended injection-to-scan acquisition time intervals.

Although we clearly recognize that the current retrospective data analysis is based upon only 32 individual 18F-FDG-avid lesions, the potential significance of our current collective observations is far-reaching for 18F-FDG PET/CT oncologic imaging. While the possibility of ultra-extended injection-to-scan acquisition time intervals of up to approximately 5 half-lives for 18F-FDG was first alluded to in the dose uptake ratio simulation studies by Hamberg et al. in 1994 [179] and was later clinically examined by Lodge et al. in 1999 [68], Spence et al. in 2004 [81], Basu et al. in 2009 [111], Horky et al. [136], and Prieto et al. in 2011 [144], its potential future impact has not previously been fully realized within the nuclear medicine or surgical literature. The ability to maintain good/adequate diagnostic image quality for 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging at extended injection-to-scan acquisition time intervals of up to approximately 5 half-lives and the resultant time-dependent increase in the observed 18F-FDG-avid lesion SUVmax values, decrease in the observed background SUVmax values, and increase in the lesion-to-background SUVmax ratios allow for and justify the more widespread and integrated, real-time use of diagnostic 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging in conjunction with 18F-FDG-directed interventional radiology biopsy procedures and ablation procedures, as well as with 18F-FDG-directed surgical procedures. Such integrated, real-time utilities for diagnostic 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging would facilitate periprocedural verification of appropriate tissue targeting during 18F-FDG-directed interventional radiology biopsy procedures and ablation procedures and for perioperative verification of appropriate tissue targeting and completeness of resection during 18F-FDG-directed surgical procedures. Furthermore, these resultant time-dependent observations could have far-reaching impact on potentially re-shaping future thinking regarding what represents the “most optimal” injection-to-scan acquisition time interval for all routine diagnostic 18F-FDG PET/CT oncologic imaging, as the current procedure guideline for tumor imaging with 18F-FDG PET/CT, as published by the Society of Nuclear Medicine, simply states that “emission images should be obtained at least 45 minutes after radiopharmaceutical injection” [63].

Conclusions

Our current retrospective data analysis demonstrates that 18F-FDG PET/CT oncologic imaging can be successfully performed at extended injection-to-scan acquisition time intervals of up to approximately 5 half-lives for 18F-FDG while maintaining good/adequate diagnostic image quality. The resultant increased 18F-FDG-avid lesion SUVmax values, decreased background SUVmax values, and increased lesion-to-background SUVmax ratios seen from preoperative to postoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging have great potential for allowing for the integrated, real-time use of 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging in conjunction with 18F-FDG-directed interventional radiology biopsy and ablation procedures and 18F-FDG-directed surgical procedures, as well as have far-reaching impact on potentially re-shaping future thinking regarding the “most optimal” injection-to-scan acquisition time interval for all routine diagnostic 18F-FDG PET/CT oncologic imaging. In these regards, we fully acknowledge and recognize the need for further investigations to better assess and formally evaluate the clinical utility of extended injection-to-scan acquisition time intervals in various diagnostic 18F-FDG PET/CT oncologic imaging applications.

Competing interests

All the authors declare that they have no competing interests to report.

Authors’ contributions

SPP was responsible for the overall study design, data collection, data organization, data analysis/interpretation, writing of all drafts of the manuscript, and has approved final version of the submitted manuscript. DAM was involved in study design, data collection, data organization, data analysis/interpretation, writing portions of the manuscript, and has approved final version of the submitted manuscript. SMS was involved in data organization, data analysis, and has approved final version of the submitted manuscript. EWM was involved in discussion about study design, data analysis/interpretation, critiquing drafts of the manuscript, and has approved final version of the submitted manuscript. NCH was involved in study design, discussion about data analysis/interpretation, editing portions of the manuscript, and has approved final version of the submitted manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Stephen P Povoski, Email: stephen.povoski@osumc.edu.

Douglas A Murrey, Jr, Email: douglas.murrey@osumc.edu.

Sabrina M Smith, Email: sabrina.smith@osumc.edu.

Edward W Martin, Jr, Email: edward.martin@osumc.edu.

Nathan C Hall, Email: nathan.hall@osumc.edu.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the following people from The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center for their ongoing assistance with the 18F-FDG-directed surgery program: Dr. Charles Hitchcock from the Department of Pathology; Dr. Michael V. Knopp from the Department of Radiology; Dr. David W. Barker from the Division of Molecular Imaging and Nuclear Medicine, Department of Radiology; Deborah Hurley, Marlene Wagonrod, and the entire staff of the Division of Molecular Imaging and Nuclear Medicine, Department of Radiology; Nichole Storey from the Department of Radiology; and the operating room staff from the Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute.

References

- Hillner BE, Siegel BA, Liu D, Shields AF, Gareen IF, Hanna L, Stine SH, Coleman RE. Impact of positron emission tomography/computed tomography and positron emission tomography (PET) alone on expected management of patients with cancer: initial results from the National Oncologic PET Registry. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2155–2161. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.5631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poeppel TD, Krause BJ, Heusner TA, Boy C, Bockisch A, Antoch G. PET/CT for the staging and follow-up of patients with malignancies. Eur J Radiol. 2009;70:382–392. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroobants S. To PET or not to PET: what are the indications? Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(Suppl 3):S304–S305. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(11)70180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czernin J, Allen-Auerbach M, Nathanson D, Herrmann K. PET/CT in oncology: current status and perspectives. Curr Radiol Rep. 2013;1:177–190. doi: 10.1007/s40134-013-0016-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schöder H, Gönen M. Screening for cancer with PET and PET/CT: potential and limitations. J Nucl Med. 2007;48(Suppl 1):4S–18S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai D, Arnold M, Saha S, Hinkle G, Soble D, Frye J, DePalatis L, Mantil J, Satter M, Martin E. Intraoperative gamma detection of FDG distribution in colorectal cancer. Clin Positron Imaging. 1999;2:325. doi: 10.1016/s1095-0397(99)00085-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai DC, Arnold M, Saha S, Hinkle G, Soble D, Fry J, DePalatis LR, Mantil J, Satter M, Martin EW. Correlative whole-body FDG-PET and intraoperative gamma detection of FDG distribution in colorectal cancer. Clin Positron Imaging. 2000;3:189–196. doi: 10.1016/s1095-0397(00)00052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zervos EE, Desai DC, DePalatis LR, Soble D, Martin EW. 18F-labeled fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-guided surgery for recurrent colorectal cancer: a feasibility study. J Surg Res. 2001;97:9–13. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2001.6092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essner R, Hsueh EC, Haigh PI, Glass EC, Huynh Y, Daghighian F. Application of an [(18) F] fluorodeoxyglucose-sensitive probe for the intraoperative detection of malignancy. J Surg Res. 2001;96:120–126. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2000.6069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essner R, Daghighian F, Giuliano AE. Advances in FDG PET probes in surgical oncology. Cancer J. 2002;8:100–108. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200203000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashi T, Saga T, Ishimori T, Mamede M, Ishizu K, Fujita T, Mukai T, Sato S, Kato H, Yamaoka Y, Matsumoto K, Senda M, Konishi J. What is the most appropriate scan timing for intraoperative detection of malignancy using 18F-FDG-sensitive gamma probe? Preliminary phantom and preoperative patient study. Ann Nucl Med. 2004;18:105–114. doi: 10.1007/BF02985100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap JT, Carney JP, Hall NC, Townsend DW. Image-guided cancer therapy using PET/CT. Cancer J. 2004;10:221–233. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200407000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barranger E, Kerrou K, Petegnief Y, David-Montefiore E, Cortez A, Daraï E. Laparoscopic resection of occult metastasis using the combination of FDG-positron emission tomography/computed tomography image fusion with intraoperative probe guidance in a woman with recurrent ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;96:241–244. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrera D, Fernandez A, Estrada J, Martin-Comin J, Gamez C. Detection of occult malignant melanoma by 18F-FDG PET-CT and gamma probe. Rev Esp Med Nucl. 2005;24:410–413. doi: 10.1016/s0212-6982(05)74186-0. [Spanish] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franc BL, Mari C, Johnson D, Leong SP. The role of a positron- and high-energy gamma photon probe in intraoperative localization of recurrent melanoma. Clin Nucl Med. 2005;30:787–791. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000186856.86505.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraeber-Bodéré F, Cariou B, Curtet C, Bridji B, Rousseau C, Dravet F, Charbonnel B, Carnaille B, Le Néel JC, Mirallié E. Feasibility and benefit of fluorine 18-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose-guided surgery in the management of radioiodine-negative differentiated thyroid carcinoma metastases. Surgery. 2005;138:1176–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulec SA, Daghighian F, Essner R. PET-Probe. Evaluation of Technical Performance and Clinical Utility of a Handheld High-Energy Gamma Probe in Oncologic Surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Meller B, Sommer K, Gerl J, von Hof K, Surowiec A, Richter E, Wollenberg B, Baehre M. High energy probe for detecting lymph node metastases with 18F-FDG in patients with head and neck cancer. Nuklearmedizin. 2006;45:153–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nwogu C, Fischer G, Tan D, Glinianski M, Lamonica D, Demmy T. Radioguided detection of lymph node metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:1815–1820. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.05.104. discussion 1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtet C, Carlier T, Mirallié E, Bodet-Milin C, Rousseau C, Barbet J, Kraeber-Bodéré F. Prospective comparison of two gamma probes for intraoperative detection of 18F-FDG: in vitro assessment and clinical evaluation in differentiated thyroid cancer patients with iodine-negative recurrence. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:1556–1562. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0393-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulec SA, Hoenie E, Hostetter R, Schwartzentruber D. PET probe-guided surgery: applications and clinical protocol. World J Surg Oncol. 2007;5:65. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-5-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulec SA. PET probe-guided surgery. J Surg Oncol. 2007;96:353–357. doi: 10.1002/jso.20862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall NC, Povoski SP, Murrey DA, Knopp MV, Martin EW. Combined approach of perioperative 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging and intraoperative 18F-FDG handheld gamma probe detection for tumor localization and verification of complete tumor resection in breast cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2007;5:143. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-5-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piert M, Burian M, Meisetschlager G, Stein HJ, Ziegler S, Nahrig J, Picchio M, Buck A, Siewert JR, Schwaiger M. Positron detection for the intraoperative localisation of cancer deposits. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:1534–1544. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0430-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarikaya I, Povoski SP, Al-Saif OH, Kocak E, Bloomston M, Marsh S, Cao Z, Murrey DA, Zhang J, Hall NC, Knopp MV, Martin EW. Combined use of preoperative 18F FDG-PET imaging and intraoperative gamma probe detection for accurate assessment of tumor recurrence in patients with colorectal cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2007;5:80. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-5-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D, Bloomston M, Hinkle G, Al-Saif OH, Hall NC, Povoski SP, Arnold MW, Martin EW. Radioimmunoguided surgery (RIGS), PET/CT image-guided surgery, and fluorescence image-guided surgery: past, present, and future. J Surg Oncol. 2007;96:297–308. doi: 10.1002/jso.20869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior JO, Kosinski M, Delaloye AB, Denys A. Initial report of PET/CT-guided radiofrequency ablation of liver metastases. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2007;18:801–803. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, Hall NC, Ringel MD, Povoski SP, Martin EW Jr. Combined use of perioperative TSH-stimulated 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging and gamma probe radioguided surgery to localize and verify resection of iodine scan-negative recurrent thyroid carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2008;118:2190–2194. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e3181845738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn DE, Hall NC, Povoski SP, Seamon LG, Farrar WB, Martin EW Jr. Novel perioperative imaging with 18F-FDG PET/CT and intraoperative 18F-FDG detection using a handheld gamma probe in recurrent ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;110:152–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall NC, Povoski SP, Murrey DA, Knopp MV, Martin EW. Bringing advanced medical imaging into the operative arena could revolutionize the surgical care of cancer patients. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2008;5:663–667. doi: 10.1586/17434440.5.6.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffatt-Bruce SD, Povoski SP, Sharif S, Hall NC, Ross P Jr, Johnson MA, Martin EW Jr. A novel approach to positron emission tomography in lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86:1355–1357. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piert M, Carey J, Clinthorne N. Probe-guided localization of cancer deposits using [(18) F] fluorodeoxyglucose. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;52:37–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povoski SP, Hall NC, Martin EW, Walker MJ. Multimodality approach of perioperative 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging, intraoperative 18F-FDG handheld gamma probe detection, and intraoperative ultrasound for tumor localization and verification of resection of all sites of hypermetabolic activity in a case of occult recurrent metastatic melanoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2008;6:1. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povoski SP, Sarikaya I, White WC, Marsh SG, Hall NC, Hinkle GH, Martin EW Jr, Knopp MV. Comprehensive evaluation of occupational radiation exposure to intraoperative and perioperative personnel from 18F-FDG radioguided surgical procedures. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:2026–2034. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0880-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Baardwijk A, Bosmans G, van Suylen RJ, van Kroonenburgh M, Hochstenbag M, Geskes G, Lambin P, De Ruysscher D. Correlation of intra-tumour heterogeneity on 18F-FDG PET with pathologic features in non-small cell lung cancer: a feasibility study. Radiother Oncol. 2008;87:55–58. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povoski SP, Neff RL, Mojzisik CM, O’Malley DM, Hinkle GH, Hall NC, Murrey DA Jr, Knopp MV, Martin EW Jr. A comprehensive overview of radioguided surgery using gamma detection probe technology. World J Surg Oncol. 2009;7:11. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-7-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murrey DA Jr, Bahnson EE, Hall NC, Povoski SP, Mojzisik CM, Young DC, Sharif S, Johnson MA, Abdel-Misih S, Martin EW Jr, Knopp MV. Perioperative (18) F-fluorodeoxyglucose-guided imaging using the becquerel as a quantitative measure for optimizing surgical resection in patients with advanced malignancy. Am J Surg. 2009;198:834–840. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollub MJ, Akhurst TJ, Williamson MJ, Shia J, Humm JL, Wong WD, Paty PB, Guillem JG, Weiser MR, Temple LK, Dauer LT, Jhanwar SC, Kronman RE, Montalvo CV, Miller AR, Larson SM, Margulis AR. Feasibility of ex vivo FDG PET of the colon. Radiology. 2009;252:232–239. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2522081864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaeser B, Mueller MD, Schmid RA, Guevara C, Krause T, Wiskirchen J. PET-CT-guided interventions in the management of FDG-positive lesions in patients suffering from solid malignancies: initial experiences. Eur Radiol. 2009;19:1780–1785. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1338-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina MA, Goodwin WJ, Moffat FL, Serafini AN, Sfakianakis GN, Avisar E. Intra-operative use of PET probe for localization of FDG avid lesions. Cancer Imaging. 2009;9:59–62. doi: 10.1102/1470-7330.2009.0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallarajapatna GJ, Kallur KG, Ramanna NK, Susheela SP, Ramachandra PG. PET/CT-guided percutaneous biopsy of isolated intramuscular metastases from postcricoid cancer. J Nucl Med Technol. 2009;37:220–222. doi: 10.2967/jnmt.109.064709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall NC, Povoski SP, Murrey DA, Martin EW Jr, Knopp MV. Ex vivo specimen FDG PET/CT imaging for oncology. Radiology. 2010;255:663–664. doi: 10.1148/radiol.0102515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalley C, Wiebeck K, Bartel TB, Bodenner D, Stack BC Jr. Intraoperative radiation exposure with the use of (18) F-FDG-guided thyroid cancer surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;142:281–283. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong JS, van Ginkel RJ, Slart RH, Lemstra CL, Paans AM, Mulder NH, Hoekstra HJ. FDG-PET probe-guided surgery for recurrent retroperitoneal testicular tumor recurrences. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36:1092–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2010.08.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartemink KJ, Muller S, Smulders YM, Petrousjka Van Den Tol M, Comans EF. Fluorodeoxyglucose F18(FDG)-probe guided biopsy. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2010;154:A1884. [Dutch] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee GO, Costouro NG, Groome T, Kashani-Sabet M, Leong SPL. The use of intraoperative PET probe to resect metastatic melanoma. BMJ Case Reports. 2010. doi:10.1136/bcr.12.2009.2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Klaeser B, Wiskirchen J, Wartenberg J, Weitzel T, Schmid RA, Mueller MD, Krause T. PET/CT-guided biopsies of metabolically active bone lesions: applications and clinical impact. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:2027–2036. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1524-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García JR, Fraile M, Soler M, Bechini J, Ayuso JR, Lomeña F. PET/CT-guided salvage surgery protocol. Results with ROLL Technique and PET probe. Rev Esp Med Nucl. 2011;30:217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.remn.2011.02.011. [Spanish] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WW, Kim JS, Hur SM, Kim SH, Lee SK, Choi JH, Kim S, Choi JY, Lee JE, Kim JH, Nam SJ, Yang JH, Choe JH. Radioguided surgery using an intraoperative PET probe for tumor localization and verification of complete resection in differentiated thyroid cancer: A pilot study. Surgery. 2011;149:416–424. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manca G, Biggi E, Lorenzoni A, Boni G, Roncella M, Ghilli M, Volterrani D, Mariani G. Simultaneous detection of breast tumor resection margins and radioguided sentinel node biopsy using an intraoperative electronically collimated probe with variable energy window: a case report. Clin Nucl Med. 2011;36:e196–e198. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e31821c9a4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povoski SP, Hall NC, Murrey DA Jr, Chow AZ, Gaglani JR, Bahnson EE, Mojzisik CM, Kuhrt MP, Hitchcock CL, Knopp MV, Martin EW Jr. Multimodal imaging and detection approach to 18F-FDG-directed surgery for patients with known or suspected malignancies: a comprehensive description of the specific methodology utilized in a single-institution cumulative retrospective experience. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:152. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-9-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatli S, Gerbaudo VH, Feeley CM, Shyn PB, Tuncali K, Silverman SG. PET/CT-guided percutaneous biopsy of abdominal masses: initial experience. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22:507–514. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner MK, Aschoff P, Reimold M, Pfannenberg C. FDG-PET/CT-guided biopsy of bone metastases sets a new course in patient management after extensive imaging and multiple futile biopsies. Br J Radiol. 2011;84:e65–e67. doi: 10.1259/bjr/26998246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainani NI, Shyn PB, Tatli S, Morrison PR, Tuncali K, Silverman SG. PET/CT-guided radiofrequency and cryoablation: is tumor fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose activity dissipated by thermal ablation? J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22:354–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis CL, Nalley C, Fan C, Bodenner D, Stack BC Jr. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose and 131I Radioguided Surgical Management of Thyroid Cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;146:26–32. doi: 10.1177/0194599811423007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bains S, Reimert M, Win AZ, Khan S, Aparici CM. A patient with psoriatic arthritis imaged with FDG-PET/CT demonstrated an unusual imaging pattern with muscle and fascia involvement: a case report. Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;46:138–143. doi: 10.1007/s13139-012-0137-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos CG, Hartemink KJ, Muller S, Oosterhuis JW, Meijer S, van den Tol MP, Comans EF. Clinical applications of FDG-probe guided surgery. Acta Chir Belg. 2012;112:414–418. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2012.11680864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall NC, Povoski SP, Zhang J, Knopp MV, Martin EW Jr. Use of intraoperative nuclear medicine imaging technology: strategy for improved patient management. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2013;10:149–152. doi: 10.1586/erd.13.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povoski SP, Chapman GJ, Murrey DA Jr, Lee R, Martin EW Jr, Hall NC. Intraoperative detection of 18F-FDG-avid tissue sites using the increased probe counting efficiency of the K-alpha probe design and variance-based statistical analysis with the three-sigma criteria. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:98. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerci JJ, Pereira Neto CC, Krauzer C, Sakamoto DG, Vitola JV. The impact of coaxial core biopsy guided by FDG PET/CT in oncological patients. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40:98–103. doi: 10.1007/s00259-012-2263-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Win AZ, Aparici CM. Real-time FDG PET/CT-guided bone biopsy in a patient with two primary malignancies. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40:1787–1788. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2492-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerci JJ, Huber FZT, Bogoni M. PET/CT-guided biopsy of liver lesions. Clin Transl Imaging. 2014;2:157–163. [Google Scholar]

- Delbeke D, Coleman RE, Guiberteau MJ, Brown ML, Royal HD, Siegel BA, Townsend DW, Berland LL, Parker JA, Hubner K, Stabin MG, Zubal G, Kachelriess M, Cronin V, Holbrook S. Procedure guideline for tumor imaging with 18F-FDG PET/CT 1.0. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:885–895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall N, Murrey D, Povoski S, Barker D, Zhang J, Bahnson E, Chow A, Martin EW, Knopp MV. Evaluation of 18FDG PET/CT image quality with prolonged injection-to-scan times. Mol Imaging Biol. 2012;14(2, supplement):610. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe VJ, DeLong DM, Hoffman JM, Coleman RE. Optimum scanning protocol for FDG-PET evaluation of pulmonary malignancy. J Nucl Med. 1995;36:883–887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerner AR, Weckesser M, Herzog H, Schmitz T, Audretsch W, Nitz U, Bender HG, Mueller-Gaertner HW. Optimal scan time for fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in breast cancer. Eur J Nucl Med. 1999;26:226–230. doi: 10.1007/s002590050381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hustinx R, Smith RJ, Benard F, Rosenthal DI, Machtay M, Farber LA, Alavi A. Dual time point fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography: a potential method to differentiate malignancy from inflammation and normal tissue in the head and neck. Eur J Nucl Med. 1999;26:1345–1348. doi: 10.1007/s002590050593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodge MA, Lucas JD, Marsden PK, Cronin BF, O’Doherty MJ, Smith MA. A PET study of 18FDG uptake in soft tissue masses. Eur J Nucl Med. 1999;26:22–30. doi: 10.1007/s002590050355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamoto Y, Higashi T, Sakahara H, Tamaki N, Kogire M, Doi R, Hosotani R, Imamura M, Konishi J. Delayed (18) F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography scan for differentiation between malignant and benign lesions in the pancreas. Cancer. 2000;89:2547–2554. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001215)89:12<2547::aid-cncr5>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota K, Itoh M, Ozaki K, Ono S, Tashiro M, Yamaguchi K, Akaizawa T, Yamada K, Fukuda H. Advantage of delayed whole-body FDG-PET imaging for tumour detection. Eur J Nucl Med. 2001;28:696–703. doi: 10.1007/s002590100537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang H, Pourdehnad M, Lambright ES, Yamamoto AJ, Lanuti M, Li P, Mozley PD, Rossman MD, Albelda SM, Alavi A. Dual time point 18F-FDG PET imaging for differentiating malignant from inflammatory processes. J Nucl Med. 2001;42:1412–1417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama K, Okamura T, Kawabe J, Ozawa N, Higashiyama S, Ochi H, Yamada R. The usefulness of 18F-FDG PET images obtained 2 hours after intravenous injection in liver tumor. Ann Nucl Med. 2002;16:169–176. doi: 10.1007/BF02996297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthies A, Hickeson M, Cuchiara A, Alavi A. Dual time point 18F-FDG PET for the evaluation of pulmonary nodules. J Nucl Med. 2002;43:871–875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad GR, Sinha P. Narrow time-window dual-point 18F-FDG PET for the diagnosis of thoracic malignancy. Nucl Med Commun. 2003;24:1129–1137. doi: 10.1097/00006231-200311000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demura Y, Tsuchida T, Ishizaki T, Mizuno S, Totani Y, Ameshima S, Miyamori I, Sasaki M, Yonekura Y. 18F-FDG accumulation with PET for differentiation between benign and malignant lesions in the thorax. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:540–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma SY, See LC, Lai CH, Chou HH, Tsai CS, Ng KK, Hsueh S, Lin WJ, Chen JT, Yen TC. Delayed (18) F-FDG PET for detection of paraaortic lymph node metastases in cervical cancer patients. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:1775–1783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen TC, Ng KK, Ma SY, Chou HH, Tsai CS, Hsueh S, Chang TC, Hong JH, See LC, Lin WJ, Chen JT, Huang KG, Lui KW, Lai CH. Value of dual-phase 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose positron emission tomography in cervical cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3651–3658. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Döbert N, Hamscho N, Menzel C, Neuss L, Kovács AF, Grünwald F. Limitations of dual time point FDG-PET imaging in the evaluation of focal abdominal lesions. Nuklearmedizin. 2004;43:143–149. doi: 10.1267/nukl04050143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota K, Yokoyama J, Yamaguchi K, Ono S, Qureshy A, Itoh M, Fukuda H. FDG-PET delayed imaging for the detection of head and neck cancer recurrence after radio-chemotherapy: comparison with MRI/CT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;31:590–595. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1408-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai CH, Huang KG, See LC, Yen TC, Tsai CS, Chang TC, Chou HH, Ng KK, Hsueh S, Hong JH. Restaging of recurrent cervical carcinoma with dual-phase [18F] fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography. Cancer. 2004;100:544–552. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence AM, Muzi M, Mankoff DA, O’Sullivan SF, Link JM, Lewellen TK, Lewellen B, Pham P, Minoshima S, Swanson K, Krohn KA. 18F-FDG PET of gliomas at delayed intervals: improved distinction between tumor and normal gray matter. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:1653–1659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YK, Kao CH. Metastatic hepatic lesions are detected better by delayed imaging with prolonged emission time. Clin Nucl Med. 2005;30:455–456. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000163379.64480.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Loving VA, Chauhan A, Zhuang H, Mitchell S, Alavi A. Potential of dual-time-point imaging to improve breast cancer diagnosis with (18) F-FDG PET. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1819–1824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin WY, Tsai SC, Hung GU. Value of delayed 18F-FDG-PET imaging in the detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nucl Med Commun. 2005;26:315–321. doi: 10.1097/00006231-200504000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyshchik A, Higashi T, Nakamoto Y, Fujimoto K, Doi R, Imamura M, Saga T. Dual-phase 18F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography as a prognostic parameter in patients with pancreatic cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:389–397. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1656-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama Y, Yamamoto Y, Monden T, Sasakawa Y, Tsutsui K, Wakabayashi H, Ohkawa M. Evaluation of delayed additional FDG PET imaging in patients with pancreatic tumour. Nucl Med Commun. 2005;26:895–901. doi: 10.1097/00006231-200510000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanghera B, Wong WL, Lodge MA, Hain S, Stott D, Lowe J, Lemon C, Goodchild K, Saunders M. Potential novel application of dual time point SUV measurements as a predictor of survival in head and neck cancer. Nucl Med Commun. 2005;26:861–867. doi: 10.1097/00006231-200510000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So Y, Chung JK, Jeong JM, Lee DS, Lee MC. Usefulness of additional delayed regional F-18 Fluorodeoxy-Glucose Positron Emission Tomography in the lymph node staging of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer patients. Cancer Res Treat. 2005;37:114–121. doi: 10.4143/crt.2005.37.2.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen TC, Chang YC, Chan SC, Chang JT, Hsu CH, Lin KJ, Lin WJ, Fu YK, Ng SH. Are dual-phase 18F-FDG PET scans necessary in nasopharyngeal carcinoma to assess the primary tumour and loco-regional nodes? Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:541–548. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1719-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada K, Tomita Y, Ueda T, Enomoto K, Kakunaga S, Myoui A, Higuchi I, Yoshikawa H, Hatazawa J. Evaluation of delayed 18F-FDG PET in differential diagnosis for malignant soft-tissue tumors. Ann Nucl Med. 2006;20:671–675. doi: 10.1007/BF02984678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwee SA, Wei H, Sesterhenn I, Yun D, Coel MN. Localization of primary prostate cancer with dual-phase 18F-fluorocholine PET. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:262–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavi A, Urhan M, Yu JQ, Zhuang H, Houseni M, Cermik TF, Thiruvenkatasamy D, Czerniecki B, Schnall M, Alavi A. Dual time point 18F-FDG PET imaging detects breast cancer with high sensitivity and correlates well with histologic subtypes. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:1440–1446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama Y, Yamamoto Y, Fukunaga K, Kimura N, Miki A, Sasakawa Y, Wakabayashi H, Satoh K, Ohkawa M. Dual-time-point 18F-FDG PET for the evaluation of gallbladder carcinoma. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:633–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z, Wang B, Cheng W, Cheng X, Cui R, Huo L, Dang Y, Fu Z. Endometrial and ovarian F-18 FDG uptake in serial PET studies and the value of delayed imaging for differentiation. Clin Nucl Med. 2006;31:781–787. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000247261.82757.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama Y, Yamamoto Y, Kimura N, Miki A, Sasakawa Y, Wakabayashi H, Ohkawa M. Comparison of early and delayed FDG PET for evaluation of biliary stricture. Nucl Med Commun. 2007;28:914–919. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e3282f1ac85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Núñez R, Kalapparambath A, Varela J. Improvement in sensitivity with delayed imaging of pulmonary lesions with FDG-PET. Rev Esp Med Nucl. 2007;26:196–207. doi: 10.1157/13107971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiu Y, Bhutani C, Dhurairaj T, Yu JQ, Dadparvar S, Reddy S, Kumar R, Yang H, Alavi A, Zhuang H. Dual-time point FDG PET imaging in the evaluation of pulmonary nodules with minimally increased metabolic activity. Clin Nucl Med. 2007;32:101–105. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000252457.54929.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkhawaldeh K, Bural G, Kumar R, Alavi A. Impact of dual-time-point (18) F-FDG PET imaging and partial volume correction in the assessment of solitary pulmonary nodules. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:246–252. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arena V, Skanjeti A, Casoni R, Douroukas A, Pelosi E. Dual-phase FDG-PET: delayed acquisition improves hepatic detectability of pathological uptake. Radiol Med. 2008;113:875–886. doi: 10.1007/s11547-008-0287-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu S, Mavi A, Cermik T, Houseni M, Alavi A. Implications of standardized uptake value measurements of the primary lesions in proven cases of breast carcinoma with different degree of disease burden at diagnosis: does 2-deoxy-2-[F-18] fluoro-D-glucose-positron emission tomography predict tumor biology? Mol Imaging Biol. 2008;10:62–66. doi: 10.1007/s11307-007-0121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YM, Huang G, Sun XG, Liu JJ, Chen T, Shi YP, Wan LR. Optimizing delayed scan time for FDG PET: comparison of the early and late delayed scan. Nucl Med Commun. 2008;29:425–430. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e3282f4d389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CJ, Lee BF, Yao WJ, Cheng L, Wu PS, Chu CL, Chiu NT. Dual-phase 18F-FDG PET in the diagnosis of pulmonary nodules with an initial standard uptake value less than 2.5. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:475–479. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirisamer A, Halpern BS, Schima W, Heinisch M, Wolf F, Beheshti M, Dirisamer F, Weber M, Langsteger W. Dual-time-point FDG-PET/CT for the detection of hepatic metastases. Mol Imaging Biol. 2008;10:335–340. doi: 10.1007/s11307-008-0159-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M, Yu JM, Liu NB, Liu LP, Guo HB, Yang GR, Zhang PL, Xu XQ. Significance of dual-time-point 18F-FDG PET imaging in evaluation of hilar and mediastinal lymph node metastasis in non-small-cell lung cancer. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2008;30:306–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imbriaco M, Caprio MG, Limite G, Pace L, De Falco T, Capuano E, Salvatore M. Dual-time-point 18F-FDG PET/CT versus dynamic breast MRI of suspicious breast lesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:1323–1330. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan XL, Zhang YX, Wu ZJ, Jia Q, Wei H, Gao ZR. The value of dual time point (18) F-FDG PET imaging for the differentiation between malignant and benign lesions. Clin Radiol. 2008;63:756–764. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama Y, Yamamoto Y, Kimura N, Ishikawa S, Sasakawa Y, Ohkawa M. Dual-time-point FDG-PET for evaluation of lymph node metastasis in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Nucl Med. 2008;22:245–250. doi: 10.1007/s12149-007-0103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uesaka D, Demura Y, Ishizaki T, Ameshima S, Miyamori I, Sasaki M, Fujibayashi Y, Okazawa H. Evaluation of dual-time-point 18F-FDG PET for staging in patients with lung cancer. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:1606–1612. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.051250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen RF, Chen KC, Lee JM, Chang YC, Wang J, Cheng MF, Wu YW, Lee YC. 18F-FDG PET for the lymph node staging of non-small cell lung cancer in a tuberculosis-endemic country: is dual time point imaging worth the effort? Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:1305–1315. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0733-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zytoon AA, Murakami K, El-Kholy MR, El-Shorbagy E. Dual time point FDG-PET/CT imaging. Potential tool for diagnosis of breast cancer. Clin Radiol. 2008;63:1213–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu S, Kung J, Houseni M, Zhuang H, Tidmarsh GF, Alavi A. Temporal profile of fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in malignant lesions and normal organs over extended time periods in patients with lung carcinoma: implications for its utilization in assessing malignant lesions. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;53:9–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin BB, Green ED, Turkington TG, Hawk TC, Coleman RE. Increasing uptake time in FDG-PET: standardized uptake values in normal tissues at 1 versus 3 h. Mol Imaging Biol. 2009;11:118–122. doi: 10.1007/s11307-008-0177-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q, Wang W, Zhong X, Yuan S, Fu Z, Guo H, Yu J. Dual-time-point FDG PET for the evaluation of locoregional lymph nodes in thoracic esophageal squamous cell cancer. Eur J Radiol. 2009;70:320–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue A, Tomiyama N, Tatsumi M, Ikeda N, Okumura M, Shiono H, Inoue M, Higuchi I, Aozasa K, Johkoh T, Nakamura H, Hatazawa J. (18) F-FDG PET for the evaluation of thymic epithelial tumors: Correlation with the World Health Organization classification in addition to dual-time-point imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36:1219–1225. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim IJ, Kim SJ, Kim YS, Lee TH, Jeong YJ. Characterization of pulmonary lesions with low F-18 FDG uptake using double phase F-18 FDG PET/CT: comparison of visual and quantitative analyses. Neoplasma. 2009;56:33–39. doi: 10.4149/neo_2009_01_33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laffon E, de Clermont H, Begueret H, Vernejoux JM, Thumerel M, Marthan R, Ducassou D. Assessment of dual-time-point 18F-FDG-PET imaging for pulmonary lesions. Nucl Med Commun. 2009;30:455–461. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e32832bdcac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavi A, Basu S, Cermik TF, Urhan M, Bathaii M, Thiruvenkatasamy D, Houseni M, Dadparvar S, Alavi A. Potential of dual time point FDG-PET imaging in differentiating malignant from benign pleural disease. Mol Imaging Biol. 2009;11:369–378. doi: 10.1007/s11307-009-0212-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schillaci O, Travascio L, Bolacchi F, Calabria F, Bruni C, Cicciò C, Guazzaroni M, Orlacchio A, Simonetti G. Accuracy of early and delayed FDG PET-CT and of contrast-enhanced CT in the evaluation of lung nodules: a preliminary study on 30 patients. Radiol Med. 2009;114:890–906. doi: 10.1007/s11547-009-0400-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinya T, Rai K, Okumura Y, Fujiwara K, Matsuo K, Yonei T, Sato T, Watanabe K, Kawai H, Sato S, Kanazawa S. Dual-time-point F-18 FDG PET/CT for evaluation of intrathoracic lymph nodes in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Nucl Med. 2009;34:216–221. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e31819a1f3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga K, Kawakami Y, Hiyama A, Sugi K, Okabe K, Matsumoto T, Ueda K, Tanaka N, Matsunaga N. Differential diagnosis between (18) F-FDG-avid metastatic lymph nodes in non-small cell lung cancer and benign nodes on dual-time point PET/CT scan. Ann Nucl Med. 2009;23:523–531. doi: 10.1007/s12149-009-0268-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga K, Kawakami Y, Hiyama A, Sugi K, Okabe K, Matsumoto T, Ueda K, Tanaka N, Matsunaga N. Dual-time point 18F-FDG PET/CT scan for differentiation between 18F-FDG-avid non-small cell lung cancer and benign lesions. Ann Nucl Med. 2009;23:427–435. doi: 10.1007/s12149-009-0260-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga K, Kawakami Y, Hiyama A, Matsunaga N. Differentiation of FDG-avid loco-regional recurrent and compromised benign lesions after surgery for breast cancer with dual-time point F-18-fluorodeoxy-glucose PET/CT scan. Ann Nucl Med. 2009;23:399–407. doi: 10.1007/s12149-009-0261-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su MG, Fan QP, Tian Y, Li FL, Yang XC, Li L, Fan CZ, Tian R. Differentiation of malignant and benign superficial lymph nodes by dual time point 18F-FDG PET. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2009;40:517–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian R, Su M, Tian Y, Li F, Li L, Kuang A, Zeng J. Dual-time point PET/CT with F-18 FDG for the differentiation of malignant and benign bone lesions. Skeletal Radiol. 2009;38:451–458. doi: 10.1007/s00256-008-0643-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, Kameyama R, Togami T, Kimura N, Ishikawa S, Yamamoto Y, Nishiyama Y. Dual time point FDG PET for evaluation of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Nucl Med Commun. 2009;30:25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CY, Noujaim D, Fu HF, Huang WS, Cheng CY, Thie J, Dalal I, Chang CY, Nagle C. Time sensitivity: a parameter reflecting tumor metabolic kinetics by variable dual-time F-18 FDG PET imaging. Mol Imaging Biol. 2009;11:283–290. doi: 10.1007/s11307-009-0206-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zytoon AA, Murakami K, El-Kholy MR, El-Shorbagy E, Ebied O. Breast cancer with low FDG uptake: characterization by means of dual-time point FDG-PET/CT. Eur J Radiol. 2009;70:530–538. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caprio MG, Cangiano A, Imbriaco M, Soscia F, Di Martino G, Farina A, Avitabile G, Pace L, Forestieri P, Salvatore M. Dual-time-point [18F]-FDG PET/CT in the diagnostic evaluation of suspicious breast lesions. Radiol Med. 2010;115:215–224. doi: 10.1007/s11547-009-0491-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloran FJ, Banks KP, Song WS, Kim Y, Bradley YC. Limitations of dual time point PET in the assessment of lung nodules with low FDG avidity. Lung Cancer. 2010;68:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai T, Motoori K, Horikoshi T, Uchiyama K, Yasufuku K, Takiguchi Y, Takahashi F, Kuniyasu Y, Ito H. Dual-time point scanning of integrated FDG PET/CT for the evaluation of mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes in non-small cell lung cancer diagnosed as operable by contrast-enhanced CT. Eur J Radiol. 2010;75:143–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DW, Jung SA, Kim CG, Park SA. The efficacy of dual time point F-18 FDG PET imaging for grading of brain tumors. Clin Nucl Med. 2010;35:400–403. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3181db4cfb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sathekge MM, Maes A, Pottel H, Stoltz A, van de Wiele C. Dual time-point FDG PET-CT for differentiating benign from malignant solitary pulmonary nodules in a TB endemic area. S Afr Med J. 2010;100:598–601. doi: 10.7196/samj.4082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkhawaldeh K, Biersack HJ, Henke A, Ezziddin S. Impact of dual-time-point F-18 FDG PET/CT in the assessment of pleural effusion in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Nucl Med. 2011;36:423–428. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3182173823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan WL, Ramsay SC, Szeto ER, Freund J, Pohlen JM, Tarlinton LC, Young A, Hickey A, Dura R. Dual-time-point (18) F-FDG-PET/CT imaging in the assessment of suspected malignancy. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2011;55:379–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-9485.2011.02287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi WH, Yoo IR, O JH, Kim SH, Chung SK. The value of dual-time-point 18F-FDG PET/CT for identifying axillary lymph node metastasis in breast cancer patients. Br J Radiol. 2011;84:593–599. doi: 10.1259/bjr/56324742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horky LL, Hsiao EM, Weiss SE, Drappatz J, Gerbaudo VH. Dual phase FDG-PET imaging of brain metastases provides superior assessment of recurrence versus post-treatment necrosis. J Neurooncol. 2011;103:137–146. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0365-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao YC, Wu PS, Chiu NT, Yao WJ, Lee BF, Peng SL. The use of dual-phase F-18-FDG PET in characterizing thyroid incidentalomas. Clin Radiol. 2011;66:1197–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]