Abstract

The context preexposure facilitation effect (CPFE) is a variant of context fear conditioning in which context preexposure facilitates conditioning to immediate foot shock. Learning about context (preexposure), associating the context with shock (training), and expression of context fear (testing) occur in successive phases of the protocol. The CPFE develops postnatally, depends on hippocampal NMDA receptor function, and is highly sensitive to neonatal alcohol exposure during the weanling/juvenile period of development (Murawski and Stanton, 2011; Schiffino et al., 2011). The present study examined some behavioral and pharmacological mechanisms through which neonatal alcohol impairs the CPFE in juvenile rats. We found that a 5-minute context preexposure plus five 1-minute preexposures greatly increases the levels of conditioned freezing compared to a single five- minute exposure or to five 1-minute preexposures (Experiment 1). Increasing conditioned freezing with the multiple- exposure CPFE protocol does not alter the neonatal alcohol-induced deficit in the CPFE (Experiment 2). Finally, systemic administration of 0.01 mg/kg physostigmine prior to all three phases of the CPFE reverses this ethanol-induced deficit. These findings show that impairment of the CPFE by neonatal alcohol is not confined to behavioral protocols that produce low levels of conditioned freezing. They also support recent evidence that this impairment reflects a disruption of cholinergic function (Monk et al., 2012).

Keywords: Contextual Fear Conditioning, Neonatal Alcohol Exposure, Cholinergic System, Hippocampus, Spatial Cognition, Fetal Alcohol Syndrome

1. Introduction

Alcohol is a major teratogen that damages the developing brain. Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) is the most common and preventable cause of intellectual and developmental disability, occurring in 0.2-7 cases per 1000 live births in the United States each year [1, 2]. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) is a broader term that characterizes children with prenatal alcohol exposure that have the developmental, behavioral, and cognitive deficits of FAS, but without the characteristic facial phenotype [2]. Children with FASD have behavioral impairments that include hyperactivity, and problems with attention, inhibition, motor performance, learning, and memory [3, 4]. Impairments of brain and behavioral development found in the human disorder can be studied in animal models of FASD [2, 3, 5, 6]. Research with animal models has contributed importantly to our understanding of the relationship between the pattern, timing, and dose of alcohol exposure, and subsequent neurobehavioral development.

The “brain growth spurt” is a period of extensive neurogenesis and synaptogenesis during the third trimester in humans when the brain is highly susceptible to the teratogenic effects of alcohol exposure [7, 8]. Neonatal alcohol exposure is used as a rodent model of third trimester exposure in humans, as the brain growth spurt in the rat occurs around postnatal day (PD) 4-10 [7, 9]. Alcohol exposure anytime during the brain growth spurt in the rat damages the hippocampus [8, 10, 11] and causes deficits on behavioral tasks that depend on the hippocampus [12-14]. Our lab has recently discovered that a variant of context fear conditioning, known as the context preexposure facilitation effect (CPFE) is especially sensitive to neonatal alcohol exposure compared to other commonly used tasks [14, 15]. In the CPFE, learning about the context (preexposure), associating the context with the foot shock (training), and expressing contextual fear (testing) occur on three separate occasions, in which learned fear is only expressed if the animal is exposed to the testing context on the preexposure day. The basis for the sensitivity of the CPFE to neonatal alcohol is not fully understood. One possibility is that spatial learning of the context in the CPFE is “incidental” rather than “reinforcement-driven” [16]. For example, standard context conditioning, in which a context is encoded and associated with shock reinforcement on a single occasion, is less impaired by neonatal alcohol than is the CPFE, in which context encoding occurs incidentally (without shock reinforcement) on the day before the context-shock association is acquired [14]. Another possibility is that the CPFE is more sensitive to neonatal alcohol because it is merely a weaker form of context conditioning, involving lower levels of conditioned freezing than standard context conditioning. One goal of the present study was to test this possibility by re-examining the alcohol-induced deficit in the CPFE using a variant of the CPFE protocol that produces much higher level of conditioned freezing.

Another goal of this study was to test the hypothesis that neonatal alcohol impairs the CPFE by disrupting cholinergic function [17-19]. Cholinergic function in the hippocampus plays an important role in learning and memory, including contextual fear conditioning [20-22]. Recent work has shown that neonatal alcohol exposure disrupts the development of the cholinergic system [17, 18] and that choline supplementation is capable of rescuing behavioral deficits caused by neonatal alcohol exposure [18, 23]. The CPFE is an ideal behavioral paradigm for investigating the effects of cholinergic drugs on learning and memory because drug effects on different task components—context learning, fear conditioning, and expression of context fear—can be determined by administering drugs during the separate phases of the CPFE protocol [24, 25]. The present study asked whether enhancing cholinergic function with physostigmine, an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, would reverse the deficit in the CPFE shown by animals with neonatal alcohol exposure.

The present study consisted of three experiments. Experiment 1 determined whether the levels of contextual fear expressed in the CPFE can be increased by manipulating the preexposure protocol to include multiple exposures. A variant of the CPFE protocol involving multiple preexposures to the context enhances contextual fear conditioning in adult rats [26]. Experiment 1 sought to determine if the same is true for juvenile rats (PD31-33). Experiment 2 asked whether the sensitivity of the CPFE to neonatal alcohol is also seen with this variant of the CPFE protocol. Experiment 3 used this protocol to determine whether systemic administration of physostigmine can reverse the ethanol-induced deficit in contextual fear conditioning (Experiment 3).

2. Experiment 1

Multiple context preexposures enhance the CPFE in adult rats [26-29] and mice [30], but it is not known whether this effect extends to developing rats. The present experiment therefore investigated the effect of multiple preexposures on the CPFE in juvenile rats. Rats were preexposed to the training and testing context, or to an alternate context. The preexposure protocol was manipulated such that rats were either exposed to the context for five 1-minute exposures, or were preexposed to the context for 5 minutes with an additional five 1-minute exposures. Performance of these groups was compared to previously published data involving a single 5-minute preexposure. We predicted that the CPFE would be present in both protocols, however the protocol that included an additional five 1-minute exposures would produce the highest levels of context fear conditioning,

2.1 Methods

2.1.1 Subjects

Subjects for Experiment 1 were 36 Long Evans rats (19 females and 17 males, derived from 5 litters bred at the Office of Laboratory Animal Medicine at the University of Delaware. Time-mated females were housed with breeder males overnight and were examined for an ejaculatory plug the following day and, if found, that day was designated as gestational day (GD) 0. Dams were housed in clear polypropylene cages measuring 45 × 24 × 21 cm with standard bedding and access to ad libitum water and rat chow. Animals were maintained on a 12:12h light/dark cycle with lights on at 7:00 am. Date of birth was designated as postnatal day (PD) 0 (all births occurred on GD22). Litters were culled on PD3 to eight pups (usually 4 males and 4 females) and were paw-marked with subcutaneous injections of non-toxic black ink for identification. Pups were weaned from their mother on PD21 and housed with same-sex litter mates in 45 × 24 × 17 cm cages. On PD29 animals were individually housed in small white polypropylene cages (24 × 18 ×13 cm) with ad libitum access to water and rat chow for the remainder of the experiment. All subjects were treated in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Delaware following guidelines established by the National Institute of Health.

2.1.2 Apparatus and Stimuli

Fear conditioning occurred in four clear Plexiglas chambers described previously [15]. They measured 16.5 × 12.1 × 21.6 cm and were arranged in a 2 × 2 formation on a Plexiglas stand within a fume hood which provided ambient light and background noise. Each chamber had a grid floor made of 9 stainless steel bars (11.5 cm from the top of the chamber), 0.5 cm in diameter and spaced 1.25 cm apart. The 2 second footshock unconditioned stimulus (US) was delivered using a shock scrambler (Med Associates, Georgia, VT ENV-414S) connected to the grid floor. Video of each session (preexposure, training, testing) was recorded using FreezeFrame software (Actimetrics, Wilmette IL), which measures change in pixilation, with freezing defined as a bout of 0.75 seconds or longer without a change in pixels. The FreezeFrame software recorded video from the four chambers simultaneously. The alternate context, Context B, was a wire mesh cage located in a different room in the same building. The cages used were the same chambers used for eye-blink conditioning, described in Brown & Stanton [16, 31].

2.1.3 Design and Procedure

Behavioral training occurred over three days from PD30-32 or PD31-33. Animals were assigned a priori to either the preexposure (Pre) or no preexposure (No Pre) group, and assigned to one of two different preexposure protocols, non-continuous preexposure (NC) or continuous + non-continuous preexposure (CNC). Animals in the preexposure group were preexposed to the training context (Context A), and those animals in the No Pre group were preexposed to the alternate context (Context B). Animals in the NC protocol were exposed to the context for one minute; they were then removed from the context, held in their transport cages in a nearby waiting room, and were returned 30-60s later for a subsequent 1 minute exposure. This was repeated for a total of five 1- minute exposures to the context. Animals in the CNC protocol were first exposed to the context for five minutes and then removed. They were then returned to the context for five 1- minute exposures, as just described for the NC group. No more than one same-sex littermate was assigned to a given experimental group. Sex, preexposure, and protocol were equally represented in a given litter.

On the first day of the behavioral protocol, PD30 or 31, animals were weighed, and then placed in transport cages of clear Lexan (11 × 11 × 18 cm) covered with orange construction paper to obscure visual cues during transport. The rats were brought over and remained in an adjacent room to the testing room for <5 min, while the fear chambers were cleaned with 5% ammonium hydroxide solution. This weighing, cleaning, and transport protocol was consistent across all sessions and days. Pre animals were brought over and placed in Context A, which was the training and testing context described previously (see above: Apparatus and stimuli). Animals were preexposed to the context according to either the NC or CNC protocols (see above). Animals were then removed and returned to their home cage, ending the preexposure session. Animals in the No Pre group were preexposed with the NC, or CNC protocol to the alternate context (Context B).

Twenty-four hours later, animals from all groups were trained with an immediate (<5 s) 1.5 mA 2-s footshock in Context A. Rats were brought over one at a time, placed in their respective training chamber, and received an immediate footshock. Animals were immediately removed from the chamber following the footshock, returned to their transport cages, and taken back to their home cages. All animals were tested in Context A for 5 min 24 hours later in the same chamber they had been trained in. All sessions were run in the afternoon between 14:00 to 18:00hr.

To determine how these revised preexposure protocols affected test freezing relative to the single 5-minute preexposure that we've used previously [14-16, 32], previously published data from Experiment 2 in Murawski & Stanton, 2011, [15] were included in the design. This preexposure condition was referred to as continuous-five minute preexposure (CF). The apparatus and procedure from this group was identical to that used in the present study except that No Pre context differed (see Murawski and Stanton, 2011 for description [15]), a difference that did not alter performance relative to our No Pre groups (see section 2.2.1).

2.1.4 Data & Statistical Analysis

Data and statistical analyses used were described previously in Murawski and Stanton [15]. All collected data were analyzed using FreezeFrame software (Acimetrics, Wilmette IL) with bout length set at 0.75 seconds. The freezing threshold, described as change in pixels/frame, was initially set as described in software instructions. A human observer blind to the subject's groups verified the threshold setting by watching the session and adjusting the threshold if necessary to ensure that small movements were not recorded as freezing. Freezing behavior was scored as the total percent time spent freezing (the cessation of all movement except breathing) over a five minute session for the testing session.

Animal data were imported into Statistica 10 data analysis software. Freezing behavior was analyzed with a 2 (Sex) × 2 (Preexposure Group; Pre vs. No pre) × 3 (Protocol; CF, NC or CNC) factorial ANOVA. Statistical significance was set to p ≤ 0.05. Planned comparisons were performed between Pre and No Pre groups within each protocol, and for protocol differences between each preexposure group as a difference between these groups was an apriori hypothesis. If a rat in a given group had a score ± 2 standard deviations from the mean of the remaining rats in their group, its data was excluded from analysis as an outlier. Three rats were removed, one from each of the following groups: CNC-Pre, NC-Pre, and NC-No-Pre. An additional 2 rats were inadvertently oversampled from the same litter and their freezing scores were averaged and counted as one animal. Behavioral analysis was conducted on the remaining 32 subjects from the present study distributed as follows: CNC-Pre (9), CNC-No Pre (7), NC-Pre (9), and NC-No Pre (7), plus an additional 17 rats from Murawski & Stanton, 2011, [15], distributed as CF-Pre (8) and CF-No Pre (9).

2.2 Results

2.2.1 Behavioral Measures

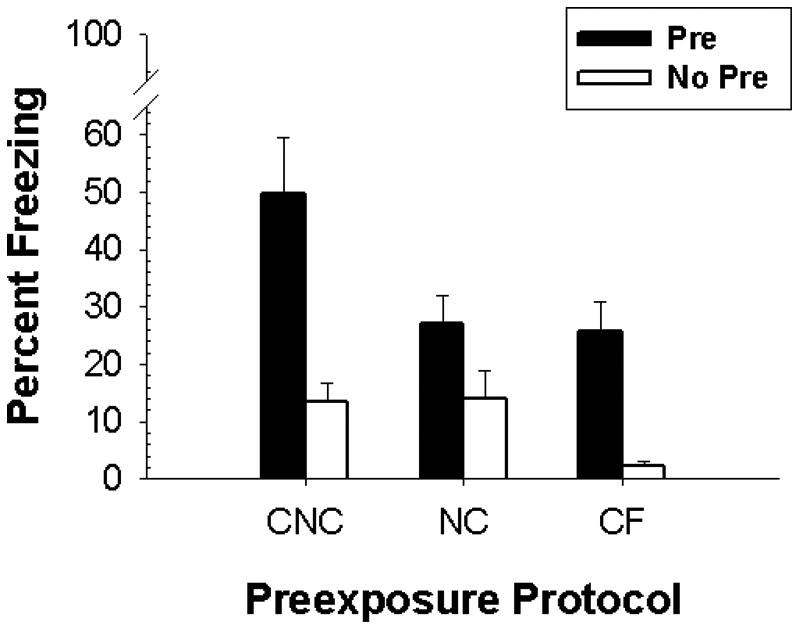

The results of Experiment 1 appear in Figure #1. Animals that were in the Pre group regardless of protocol showed greater freezing compared to their No Pre counterparts (i.e, the CPFE), and this effect was largest in the CNC protocol. ANOVA revealed a main effect of Preexposure [F(1,37)=29.05, p < 0.01] and Protocol [F(2,37)=5.78, p < 0.01], and a marginally significant Preexposure × Protocol interaction [F(2,37)=2.819, p < 0.073]. Planned comparisons showed that the CNC-Pre group froze significantly more (p < .006) than both the NC-Pre and CF-Pre groups, which did not differ. ANOVA also revealed a Sex × Protocol × Preexposure interaction [F(2,37)=3.59, p < 0.05]. Newman-Keuls tests showed that males never differed from females in any of the combinations of protocol × training group. However male CNC-Pre rats froze significantly more (p <. 01) than their CNC-No-Pre counterparts whereas this effect was not significant in females. This sex effect is probably spurious because we have not seen it previously [15, 16] and it was not replicated in the next experiment (see below).

Figure 1.

Mean (+/- SE) percent test freezing as a function of Protocol (CF, NC, or CNC) and Preexposure Group (Pre vs. No Pre) shown by rats in Experiment 1.

Taken together, this experiment shows that, in the Pre condition, the combination of a single 5-minute preexposure followed by five 1-minute preexposures substantially increases context freezing compared with either preexposure treatment performed alone. Freezing in the No Pre condition remained low regardless of preexposure protocol.

3. Experiment 2

The current experiment asked whether impairment of the CPFE by neonatal alcohol reflects the low levels of freezing produced by the single-exposure protocol (CF) used in our previous reports [14, 15]. The multiple exposures protocol from Experiment 1 (CNC), which caused an increase in the levels of context conditioning, was used to re-examine the effects of neonatal alcohol exposure. Rat pups were exposed to a high binge dose of alcohol (5.25 g/kg/d) or sham intubated over PD7-9 [15] and then trained on PD31-33 with the CNC variant of the CPFE protocol used in Experiment 1. The main question of interest was whether or not this would attenuate the alcohol-induced deficit in the CPFE.

3.1 Methods

3.1.1 Subjects

Subjects for Experiment 2 were 37 Long Evans rats (18 females and 19 males), derived from 5 litters. Animals were bred, culled, maintained, etc. as described previously (see section 2.1.1).

3.1.2 Alcohol Dosing

Rat pups from 5 litters were randomly assigned to receive a binge dose of 5.25g/kg/day of alcohol on PD7-9 (EtOH) or receive sham intubations (SI); an equal number of males and females were assigned to each group whenever possible. Dosing methods used were described previously [15, 33]. Pups were removed from their dam on PD7, weighed, and placed over a heating pad. Alcohol was administered via intragastric intubation, using PE10 tubing lubricated with corn oil and inserted down the esophagus and into the stomach of the rat pup. SI animals received an intubation lasting ∼10s without infusion of formula. Ethanol exposed animals received a custom ethanol milk formula (23.80% v/v) [33], delivered in a volume of 0.0278 ml/g body weight. Two hours following the first intubation, a small tail clip was made to collect a 20 μl blood sample of each pup, using a heparinized capillary tube. This was done for all animals on PD7 (SI animals received the tail-clip to control for any effect of this experience). Only the samples from ethanol animals were saved and analyzed for blood alcohol concentration levels. Immediately following blood sampling, pups were again intubated, ethanol animals received a milk infusion without ethanol; SI were intubated as before. A third intubation took place two hours later only on PD7, with the ethanol group receiving a second milk dose without ethanol. The milk infusions served to increase caloric intake, as ethanol animals do not suckle from the dam while inebriated. The time between each intubation was 2hrs±5 min, and intubations of a given litter took ∼25 min. Animals were dosed in a similar manner on PD8 and PD9, except that no blood samples were taken and pups received only one additional formula/sham intubation after the first intubation instead of two.

3.1.3 Blood Alcohol Concentration Analysis

Blood alcohol content (BAC) levels (expressed in mg/dl) were analyzed in a similar manner to those previously described [15]. Blood samples collected from alcohol-exposed pups were centrifuged, and the plasma was collected and stored at -20°C. The plasma samples were later analyzed using an Analox GLS Analyzer (Analox Instrument, Lunenburg, MA) and analox reagent; the Analyzer measures the rate of oxygen consumption that results from the oxidation of any ethanol present in the sample. BACs were calculated based on comparisons to known values of an alcohol standard solution.

3.1.4 Apparatus and Stimuli

Fear conditioning occurred in the same apparatus described previously in Experiment 1.

3.1.5 Design and Procedure

Behavioral training occurred over three days from PD31-33 using the continuous+noncontinuous (CNC) preexposure protocol described previously (see Experiment 1). Animals were assigned to either a preexposure (Pre) group or no preexposure group (No Pre), as previously described. Sex, preexposure, and dosing condition were equally represented in a given litter. Training and testing occurred on PD32 and PD33 respectively following the same procedure described in Experiment 1. All sessions were run in the afternoon between 14:00 to 18:00hr.

3.1.6 Data & Statistical Analysis

Data and statistical analyses were as described previously in Murawski and Stanton [15] and in Experiment 1 (see section 2.1.4). Weight gain over the dosing period (PD7-9) was analyzed with a repeated measures ANOVA with the between-subject factors of sex and dosing condition and the within-subjects factors of age. Body weights on the preexposure day (PD31) were examined using a 2 (Sex) × 2 (Dosing Condition; SI vs. EtOH) factorial ANOVA. BACs were examined using a one-way ANOVA on sex. Freezing behavior was analyzed with a 2 (Sex) × 2 (Dosing Condition; EtOH vs. SI) × 2 (Group; Pre vs. No Pre) factorial ANOVA. Statistical significance was set to p≤ 0.05. Outliers were defined and removed as described previously. Five rats met the outlier criterion based on their freezing scores during testing, this included one rat from each group and an additional rat from the EtOH-Pre group. Behavioral analysis was run on the remaining 32 animals distributed as follows: EtOH-Pre (8), EtOH-No Pre (8), SI-Pre (9), and SI-No Pre (7).

3.2 Results

3.2.1 Body Weights and BACs

Table #1 shows body weights and BACs for Experiment 2 and 3. ANOVA on PD7-9 body weights revealed a main effect of Dosing Condition [F(1,28)=67.01, p<0.05] and Days [F(2,56)=35.99, p<0.01), as well as a significant Days × Dosing Condition interaction [F(2,56)=38.20, p<0.01]. Newman-Keuls post hoc tests of the Days × Dosing Condition interaction showed that weights did not differ across dosing conditions on PD7 (ps > 0.77) or PD8 (ps > 0.08), but did differ from each other on PD9 (ps < 0.01). Within the EtOH groups, animals did not gain weight from PD7 to PD9, with none of the weights differing from each other (ps > 0.6). Within the SI groups, all pair wise contrasts across PD7, PD8 and PD9 were significant (ps < 0.01). Overall, SI animals gained weight across the PD7-9 dosing period, and EtOH animal's weight remained the same. A 2 (Sex) × 2 (Dosing Conditions) factorial ANOVA on PD31 body weights revealed no main effects or interactions, indicating weight loss in EtOH animals had recovered when testing began. BACs are also summarized in Table 1. ANOVA revealed no sex differences in BAC.

Table 1.

Mean weights (± SEM) and BACs for animals in Experiments 2 and 3.

| Experiment | Dose | Weights | BACs (mg/dl) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| PD7 | PD8 | PD9 | PD31 (males) | PD31 (females) | |||

| Exp 2 | EtOH | 13.7 ± 0.5 | 13.5 ± 0.5 | 13.6 ± 0.6* | 89.9 ± 5.8 | 79.1 ± 4.3 | 436.7 ± 16.2 |

| SI | 13.1 ± 0.4 | 15.6 ± 0.6 | 17.4 ± 0.7* | 92.5 ± 3.7 | 88.37 ± 4.1 | N/A | |

| Exp 3 | EtOH | 15.2 ± 0.4 | 15.0 ± 0.4* | 15.6 ± 0.4* | 93.8 ± 2.4*† | 88.4 ± 2.0*† | 457.9 ± 9.4 |

| SI | 15.0 ± 0.3 | 17.9 ± 0.4* | 19.9 ± 0 .4* | 102.9 ± 2.5*† | 95.8 ± 1.9*† | N/A | |

Denotes significant difference between EtOH and SI (p<0.01).

Denotes significant difference between males and females (p < 0.01).

3.2.2 Behavioral Measures

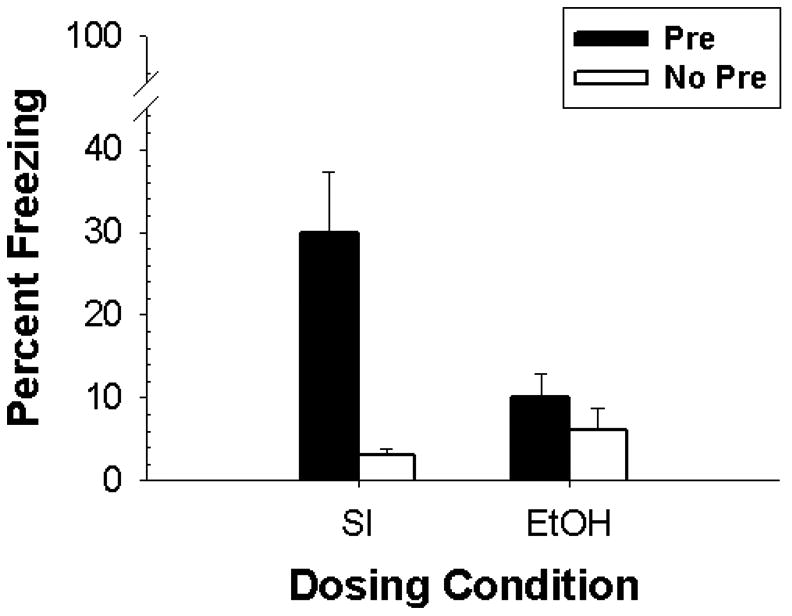

The results of Experiment 2 can be seen in Figure 2. The CPFE was present in SI controls, with Pre animals showing freezing compared to No Pre animals, but was not observed in animals exposed to ethanol during the neonatal period. ANOVA showed a main effect of Preexposure [F(1,24)=9.55, p < 0.01] and a Dosing Condition × Preexposure interaction [F(1,24)=5.26, p < 0.01]. There were no main effects or interactions involving the factor of sex. Newman-Keuls post hoc analysis showed that the SI-Pre group differed from all other groups (ps < 0.01), and also showed no difference between Pre and No Pre groups exposed to EtOH condition (ps > 0.59). This replicates previous findings that PD7-9 ethanol exposure eliminates the CPFE [15], and shows that this impairment extends to preexposure conditions that greatly increase the amount of conditioned freezing.

Figure 2.

Mean (+/- SE) percent test freezing as a function of Dosing Condition (EtOH vs. SI) and Preexposure Group (Pre vs. No Pre) shown by rats in Experiment 2.

4. Experiment 3

The CPFE depends on cholinergic function and neonatal alcohol may impair behavior via an action on cholinergic systems (see section 1. Introduction). Experiment 3 sought to determine whether increasing cholinergic function acutely during the CPFE procedure, might mitigate the disruption of the CPFE by neonatal ethanol. Systemic administration of the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, physostigmine, was used for this purpose. Animals received a 5.25 g/kg/day dose of ethanol or Sham intubation on PD7 through PD9 as described in Experiment 2. Subjects then received i.p. administration of either a 0.01 mg/kg dose of physostigmine or saline prior to all three phases of the CPFE. If neonatal alcohol impairs the CPFE by disrupting cholinergic function, then physostigmine should reverse the deficit in conditioned freezing in the ethanol exposed animals relative to sham-intubated controls.

4.1 Methods

4.1.1 Subjects

Subjects for Experiment 3 were 85 Long Evans rats (39 females and 42 males), derived from 13 litters. Animals were bred, culled, maintained, etc. as described previously.

4.1.2 Alcohol Dosing, BAC Analysis, Apparatus and Stimuli

The ethanol dosing, blood sampling procedures, BAC analyses, and apparatus, context, and stimuli were as described previously (see section 3.1.2-4).

4.1.3 Design and Procedure

Behavioral training occurred over three days from PD31-33. The CPFE preexposure procedure was the same CNC multiple-exposure protocol used previously (Experiments 1 and 2) except that only the Group Pre training condition was used. Physostigmine dose and volume was the same used by Hunt and Richardson (2007), who administered physostigmine to juvenile rats in a trace fear conditioning study[34]. Rats received an i.p. injection of either a .01 ml/kg dose of .01mg/kg physostigmine dissolved in saline or an equivalent volume of sterile saline prior to all three sessions (Preexposure, Training, and Testing). Injections occurred 10 minutes prior to the session, such that rats were weighed, received the injection, and were then brought over to a waiting room adjacent to the testing room 10 minutes prior to all three sessions. Animals were assigned randomly to either the physostigmine (Phys) or saline (Sal) treatment, with sex, alcohol dosing condition, and drug treatment equally represented per litter. All sessions were run in the afternoon between 14:00 and 18:00hr.

4.1.4 Data & Statistical Analysis

Data and statistical analyses were as described previously with one exception. To determine effects of alcohol and physostigmine on unlearned (baseline) performance, freezing behavior on the preexposure and testing days were analyzed using a repeated measures ANOVA. Thus, the analysis was a 2 (Sex) × 2 (Dosing Condition; EtoH or SI) × 2 (Drug Treatment; Phys or Sal) × 2 (Day: Preexposure, test) mixed factorial ANOVA. Statistical significance was set to p≤ 0.05. Outliers were defined and excluded from analysis as described previously. Three rats were excluded as outliers, one each from the EtOH-Sal, SI-Sal, and the EtOH-Phys groups. Data from another four animals were lost due to procedural errors during preexposure. Behavioral analyses were conducted on the remaining 78 animals distributed as follows: EtOH-Phys (19), EtOH-Sal (16), SI-Phys (20), and SI-Sal (23).

4.2 Results

4.2.1 Body Weights and BACs

Table #1 shows body weights and BACs for Experiment 3. ANOVA on PD 7-9 body weight revealed a main effects of Dosing Condition [F(1,74)=22.91,p<0.01] and days [F(2,148)=4604.86, p<0.01), as well as a significant Days × Dosing Condition interaction [F(2,148)=436.87, p<0.01]. Newman-Keuls post hoc tests of the Days × Dosing Condition interaction showed that weights of alcohol groups did not differ on PD7 (ps > 0.82), but did differ from each other on PD8 (ps < 0.01) and PD9 (ps < 0.01). Within the EtOH groups, PD9 weights were significantly higher than both PD7 and PD8 weights (ps < 0.01). Within the SI groups, all pairwise contrasts across PD7, PD8 and PD9 were significant (ps < 0.01). ANOVA on PD31 body weights revealed a main effects of sex [F(1,74)=7.65, p<0.01], with females weighing significantly less than males (Table 1), and dosing condition [F(1,74)=13.06, p<0.01), with ethanol exposed animals weighing significantly less than SI. BACs are also summarized in Table 1 for 35 animals. ANOVA on BACs revealed a main effect of sex [F(1,31)=4.39, p < 0.05], with females having a higher BACs (475.02 ± 12.14) than males (443.56 ± 13.47). However, there was no main effect or interaction involving treatment and the modestly higher BACs in females did not produce sex differences in the CPFE (see next section).

4.2.2 Behavioral Measures

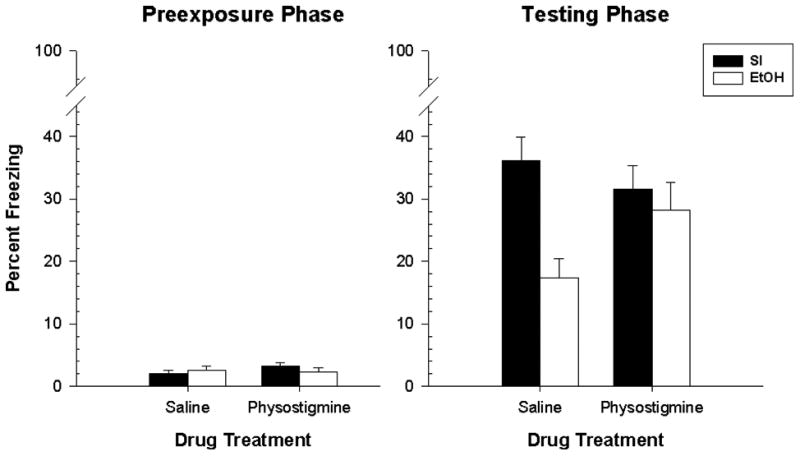

The results of Experiment 4 can be seen in Figure 3. Overall, neonatal EtOH impaired test freezing in animals injected with saline vehicle but not in animals injected with physostigmine (Fig. 3, right panel); whereasbaseline freezing was unaffected by alcohol or drug treatment (Fig. 3, left panel). Mixed factorial ANOVA revealed a Days × Dosing Condition interaction [F(1,70)=7.41,p < 0.01] and a Days × Dosing Condition × Treatment interaction [F(1,70)=4.74, p < 0.05]. Newman-Keuls tests showed that freezing during the preexposure phase was significantly less for all groups than freezing during the test phase (p < .002). Freezing during the Preexposure phase did not differ by ethanol or treatment group. Freezing during the testing phase showed that EtOH-Sal animals froze significantly less (p < 0.002). than SI-Sal, SI-Phys, and EtOH-Phys animals. EtOH-Phys animals did not significantly differ from the SI-Phys animals during the test phase nor did the SI-Phys animals differ significantly from SI-Sal animals. These findings show that physostigmine administration prior to all three phases of the CPFE mitigates the behavioral impairment in alcohol-exposed rats without affecting performance of the SI control animals. This outcome is not a result of a direct affect of physostigmine on freezing behavior per se because freezing during the preexposure phase did not differ across experimental groups. The CPFE depends on hippocampal function during all three phases[16] and so physostigmine was administered prior to all three phases in this experiment. It remains to be determined whether administration of the drug during a particular phase of the CPFE might rescue the alcohol-induced deficit.

Figure 3.

Mean (+/- SE) percent freezing by rats in Experiment 3 as a function of experimental phase (preexposure vs. testing); dosing condition (EtOH vs. SI) and drug treatment (Phys vs. Sal). All groups were exposed to the training context on the preexposure day (Pre group in previous experiments).

5. Discussion

There were three main findings in this study. The use of multiple exposures during the preexposure day of the CPFE enhanced the amount of freezing seen on the testing day (Experiment 1). This enhanced freezing did not alter the sensitivity of the CPFE to neonatal alcohol (Experiment 2), which reflects a deficit in learning and not performance [14]. Neonatal alcohol exposure does not impair conditioned freezing to discrete cues (e.g., tone) paired with shock, indicating that changes in sensory, motor, motivational processes such as differences in shock sensitivity or hyperactivity do not account for impairment of the CPFE [14]. Finally, impairment of the CPFE by neonatal alcohol is reversed by systemic injections of physostigmine, a cholinesterase inhibitor, at the time of behavioral training and testing. These findings suggest that neonatal alcohol exposure impairs context learning by disrupting cholinergic function and support other reports that the cholinergic system is involved in the CPFE.

Experiment 1 showed that 5 minutes of preexposure followed by five 1-minute preexposures (the CNC protocol) doubled the amount of conditioned freezing compared to either five 1-minute preexposures (the NC protocol) or to a single 5-minute preexposure (CF) [15]. The NC and CF protocols produced comparable levels of conditioned freezing. The CNC protocol in the present study is an adaptation of the one used by Rudy and colleagues [26-28]. They suggest that the additional exposures enhance the salience of the context memory and the association of the transport cues with the context. The memory of the transport cues are not directly associated with the learned fear, otherwise animals in the No Pre condition trained with the NC protocol would also express comparable freezing to the Pre condition on test day. Instead, it is most likely that the transport cues enhance the memory of the context representation established on the preexposure day. A previous study by Brown and colleagues [30] made a similar parametric comparison between the CPFE design used by Rudy [26-28] and that used by Gould [24] in mice. Their findings are similar to those of the present study, in that the multiple preexposure CPFE design enhanced contextual conditioning to an immediate shock compared to a single preexposure session. The enhanced freezing in the CNC condition in the present study may be attributed to the combined effects of both protocols.

Experiments 2 showed that the deficit in the CPFE caused by PD7-9 ethanol exposure is still present when rats are tested with the multiple exposure CNC protocol. This extends the finding that ethanol exposure from PD7-9 is sufficient to disrupt the CPFE from the original CF protocol of Murawski and Stanton [15] to the present CNC protocol. Because more context exposure does not ameliorate the ethanol-induced impairment of the CPFE, it appear that this impairment is a result of a qualitative deficit in contextual processing rather than a quantitative deficit reflecting insufficient time to explore or process the context. The findings of Experiment 2 also further inform a task dissociation reported by Murawski and Stanton that neonatal alcohol impairs the CPFE but not conditioned freezing seen in tone and standard context fear [14]. One problem with this dissociation is that the overall levels of freezing were much higher in these two tasks compared to the lower levels of freezing in the CPFE [14]. The present findings indicate that this variable does not explain the differential effect of neonatal alcohol across these tasks because increasing conditioned freezing in the CPFE with the CNC protocol does not alter the sensitivity of this task to neonatal alcohol.

Experiment 3 found that enhancing cholinergic function with acute physostigmine administration reverses the alcohol-induced deficit in the CPFE. This finding supports literature showing that cholinergic function plays an important role in the CPFE [24, 30], and that neonatal alcohol impairs cognition through an action on cholinergic brain systems [17, 18]. Importantly, cholinergic function seems to play a selective role in “cognitive” forms of fear conditioning rather than sensory, motor, or motivational processes related to “performance” [20-22, 34, 35]. That the CPFE depends on cholinergic function is supported by studies that have administered cholinergic drugs during various phases of the procedure [24, 25, 30]. Nicotine enhances learning of the CPFE only when administered prior to both preexposure and testing in (normal) adult mice. Administration prior to each phase of the procedure alone or prior to both preexposure and training or training and testing has no effect [24]. We found no effect of physostigmine on the CPFE in our SI control groups when it was administered prior to all three phases of the CPFE. Numerous factors (age, strain, drug, and exposure scenario) make it difficult to directly compare the findings of our study with that of Kenney and Gould [24]. Brown et al. found that administration of the muscaranic receptor antagonist, scopolamine, disrupts the CPFE in adult mice [30]. Scopolamine was administered prior to the preexposure day in their study. However, using the same juvenile rat procedure in the present report, we have found that scopolamine administered prior to any individual phase, or during all three phases, of the CPFE protocol disrupts contextual fear conditioning [36].

In Experiment 3, physostigmine did not alter conditioned freezing in SI animals, but the drug did reverse the CPFE deficit shown by EtOH-treated animals. This suggests that the ethanol induced deficit in the CPFE may be due in part to the disruption of normal cholinergic function. Ethanol exposure during development is known to target NMDA receptors and may cause excitotoxicity of neurons during alcohol withdrawal [37, 38]. This excitotoxic cell death targets hippocampal neurons that are subject to cholinergic input and contributes to the hippocampal deficits on behavioral tasks observed during adolescence and adulthood. Neonatal alcohol exposure also alters the development of the cholinergic system [17, 18]. Neonatal alcohol exposure decreases expression of muscarinic acetylcholine M1 receptors, and increases the M2/4 receptor ratio in the dorsal hippocampus of juvenile rats. Furthermore, dietary choline supplementation reversed ethanol-induced changes in M2/4 receptor density (but not in M1 receptors) and eliminated the effects of neonatal alcohol on exploratory activity. Thus, ethanol exposure has a long-term impact on the cholinergic system within the hippocampus that is correlated with behavioral deficits [18]. Additional studies by Thomas and colleagues have shown that choline supplementation reverses spatial learning deficits in the Morris water maze that result from neonatal alcohol exposure [23]. The present findings further support these studies by showing that enhancing cholinergic function acutely during behavioral testing is sufficient to reverse alcohol-induced memory deficits.

Behavioral evidence from Nagahara and Handa further support the disruption of the cholinergic system development as a result of ethanol exposure [39, 40]. Prenatal ethanol exposure during the last two weeks of gestation in the rat resulted in a loss of behavioral responsiveness to nicotine at two months of age [40], and causes a differential response to cholinergic drugs at three months of age on an T-maze alternation task [39]. They did not examine the effects of physostigmine, a non-specific choline agonist in either study and its effects on memory or behavior. A few previous studies have examined the ability of acute physostigmine administration to reverse behavioral deficits in animals exposed prenatally to alcohol [19, 41, 42]. Riley et al. found that physostigmine reversed ethanol-induced hyperactivity in 18-day-old rats [19], whereas Bond found no effect of the drug on ethanol-induced changes in the ontogeny of motor activity [42]. Blanchard and Riley also obtained negative results in a study of active avoidance learning [41]. The present study is the first to examine this question in rats exposed to alcohol during the neonatal period. As noted, the findings support other research implicating impaired cholinergic function as one mechanism through which neonatal alcohol impairs cognitive function [23, 37, 38]. The findings also support the use of interventions that target the development of brain cholinergic systems to treat cognitive deficits in human FASD.

Highlights.

Preexposure parameters influence the CPFE similarly in adult and juvenile rats.

Enhanced preexposure does not alter impairment of the CPFE by neonatal alcohol.

Neonatal alcohol impairs spatial cognition by disrupting cholinergic function.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank William Schreiber and Dr. Nathen Murawski for technical assistance, and Dr. Jeffrey Rosen for graciously allowing us to use his fear conditioning equipment. The study was supported by 2-R01-AA9838-14; 1-R21-HD070662-01, and the Undergraduate Research Program of the University of Delaware

Abbreviations

- EtOH

Ethanol exposed animals

- BAC

Blood alcohol content

- CF

continuous-five minute preexposure

- CNC

Continuous + non-continuous preexposure

- CPFE

Context preexposure facilitation effect

- FAS

Fetal alcohol syndrome

- FASD

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder

- GD

Gestational day

- NC

Non-continuous preexposure

- No Pre

No preexposure group

- PD

Postnatal day

- Phys

Physostigmine

- Pre

Preexposure group

- Sal

Saline

- SI

Sham intubated animals

- US

Unconditioned stimulus

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.May PA, Gossage JP, Marais AS, Adnams CM, Hoyme HE, Jones KL, Robinson LK, Khaole NC, Snell C, Kalberg WO, Hendricks L, Brooke L, Stellavato C, Viljoen DL. The epidemiology of fetal alcohol syndrome and partial FAS in a South African community. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:259–271. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riley EP, Infante MA, Warren KR. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: an overview. Neuropsychol Rev. 2011;21:73–80. doi: 10.1007/s11065-011-9166-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mattson SN, Crocker N, Nguyen TT. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: neuropsychological and behavioral features. Neuropsychol Rev. 2011;21:81–101. doi: 10.1007/s11065-011-9167-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kodituwakku PW, Kodituwakku EL. From research to practice: an integrative framework for the development of interventions for children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Neuropsychol Rev. 2011;21:204–223. doi: 10.1007/s11065-011-9170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riley EP. The long-term behavioral effects of prenatal alcohol exposure in rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1990;14:670–673. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1990.tb01225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones KL. The effects of alcohol on fetal development. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2011;93:3–11. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dobbing J, Sands J. Comparative aspects of the brain growth spurt. Early Hum Dev. 1979;3:79–83. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(79)90022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Livy DJ, Miller EK, Maier SE, West JR. Fetal alcohol exposure and temporal vulnerability: effects of binge-like alcohol exposure on the developing rat hippocampus. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2003;25:447–458. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(03)00030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodlett CR, Stanton ME, Steinmetz JE. Alcohol-induced damage to the developing brain: functional approaces to classical eyeblink conditioning. In: Woodruff-Pak DS, Steinmetz JE, editors. Eyeblink Classical Conditioning vol 2. Vol. 2. Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2000. pp. 135–153. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonthius DJ, West JR. Alcohol-induced neuronal loss in developing rats: increased brain damage with binge exposure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1990;14:107–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1990.tb00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berman RF, Hannigan JH. Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on the hippocampus: spatial behavior, electrophysiology, and neuroanatomy. Hippocampus. 2000;10:94–110. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(2000)10:1<94::AID-HIPO11>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodlett CR, Johnson TB. Neonatal binge ethanol exposure using intubation: timing and dose effects on place learning. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1997;19:435–446. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(97)00062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunt PS, Jacobson SE, Torok EJ. Deficits in trace fear conditioning in a rat model of fetal alcohol exposure: dose-response and timing effects. Alcohol. 2009;43:465–474. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murawski NJ, Stanton ME. Variants of contextual fear conditioning are differentially impaired in the juvenile rat by binge ethanol exposure on postnatal days 4-9. Behav Brain Res. 2010;212:133–142. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murawski NJ, Stanton ME. Effects of dose and period of neonatal alcohol exposure on the context preexposure facilitation effect. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:1160–1170. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01449.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schiffino FL, Murawski NJ, Rosen JB, Stanton ME. Ontogeny and neural substrates of the context preexposure facilitation effect. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2011;95:190–198. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelly SJ, Black AC, Jr, West JR. Changes in the muscarinic cholinergic receptors in the hippocampus of rats exposed to ethyl alcohol during the brain growth spurt. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;249:798–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monk BR, Leslie FM, Thomas JD. The effects of perinatal choline supplementation on hippocampal cholinergic development in rats exposed to alcohol during the brain growth spurt. Hippocampus. 2012;22:1750–1757. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riley EP, Barron S, Driscoll CD, Hamlin RT. The effects of physostigmine on open-field behavior in rats exposed to alcohol prenatally. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1986;10:50–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1986.tb05613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anagnostaras SG, Maren S, Fanselow MS. Scopolamine selectively disrupts the acquisition of contextual fear conditioning in rats. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1995;64:191–194. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1995.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anagnostaras SG, Maren S, Sage JR, Goodrich S, Fanselow MS. Scopolamine and Pavlovian fear conditioning in rats: dose-effect analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:731–744. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00083-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gale GD, Anagnostaras SG, Fanselow MS. Cholinergic modulation of pavlovian fear conditioning: effects of intrahippocampal scopolamine infusion. Hippocampus. 2001;11:371–376. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas JD, Biane JS, O'Bryan KA, O'Neill TM, Dominguez HD. Choline supplementation following third-trimester-equivalent alcohol exposure attenuates behavioral alterations in rats. Behav Neurosci. 2007;121:120–130. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kenney JW, Gould TJ. Nicotine enhances context learning but not context-shock associative learning. Behav Neurosci. 2008;122:1158–1165. doi: 10.1037/a0012807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kenney JW, Raybuck JD, Gould TJ. Nicotinic receptors in the dorsal and ventral hippocampus differentially modulate contextual fear conditioning. Hippocampus. 2012;22:1681–1690. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matus-Amat P, Higgins EA, Barrientos RM, Rudy JW. The role of the dorsal hippocampus in the acquisition and retrieval of context memory representations. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2431–2439. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1598-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rudy JW, Barrientos RM, O'Reilly RC. Hippocampal formation supports conditioning to memory of a context. Behav Neurosci. 2002;116:530–538. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.116.4.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rudy JW, Huff NC, Matus-Amat P. Understanding contextual fear conditioning: insights from a two-process model. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;28:675–685. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rudy JW. Context representations, context functions, and the parahippocampal-hippocampal system. Learn Memory. 2009;16:573–585. doi: 10.1101/lm.1494409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown KL, Kennard JA, Sherer DJ, Comalli DM, Woodruff-Pak DS. The context preexposure facilitation effect in mice: a dose-response analysis of pretraining scopolamine administration. Behav Brain Res. 2011;225:290–296. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.07.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown KL, Stanton ME. Cross-modal transfer of the conditioned eyeblink response during interstimulus interval discrimination training in young rats. Dev Psychobiol. 2008;50:647–664. doi: 10.1002/dev.20335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jablonski SA, Schiffino FL, Stanton ME. Role of age, post-training consolidation, and conjunctive associations in the ontogeny of the context preexposure facilitation effect. Dev Psychobiol. 2011;54:714–22. doi: 10.1002/dev.20621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelly SJ, Lawrence CR. Intragastric intubation of alcohol during the perinatal period. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;447:101–110. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-242-7_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hunt PS, Richardson R. Pharmacological dissociation of trace and long-delay fear conditioning in young rats. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2007;87:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robinson L, Platt B, Riedel G. Involvement of the cholinergic system in conditioning and perceptual memory. Behav Brain Res. 2011;221:443–465. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dokovna LB, Stanton ME. International Society for Developmental Psychobiology. New Orleans, LA: 2012. Scopolamine impairs the context pre-exposure facilitation effect in juvenile rats. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomas JD, Fleming SL, Riley EP. Administration of low doses of MK-801 during ethanol withdrawal in the developing rat pup attenuates alcohol's teratogenic effects. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:1307–1313. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000025888.60664.D9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thomas JD, Weinert SP, Sharif S, Riley EP. MK-801 administration during ethanol withdrawal in neonatal rat pups attenuates ethanol-induced behavioral deficits. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21:1218–1225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagahara AH, Handa RJ. Fetal Alcohol-Exposed Rats Exhibit Differential Response to Cholinergic Drugs on a Delay-Dependent Memory Task. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1999;72:230–243. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1999.3909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagahara AH, Handa RJ. Loss of Nicotine-Induced Effects on Locomotor Activity in Fetal Alcohol-Exposed Rats. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1999;21:647–652. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(99)00040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blanchard BA, Riley EP. Effects of physostigmine on shuttle avoidance in rats exposed prenatally to ethanol. Alcohol. 1988;5:27–31. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(88)90039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bond NW. Prenatal alcohol exposure and offspring hyperactivity: effects of physostigmine and neostigmine. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1988;10:59–63. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(88)90067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]