Abstract

Importance

Sentinel lymph node (SLN) surgery provides reliable nodal staging information with less morbidity than axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) for clinically node-negative (cN0) breast cancer patients. The application of SLN surgery for staging the axilla following chemotherapy for women who initially had node-positive breast cancer (cN1) is unclear because of high false negative results reported in previous studies.

Objective

To determine the false negative rate (FNR) for SLN surgery following chemotherapy in patients initially presenting with biopsy-proven node-positive breast cancer.

Design, Setting, and Patients

The ACOSOG Z1071 trial enrolled women with clinical T0–4 N1–2, M0 breast cancer who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Following chemotherapy, patients underwent both SLN surgery and ALND. SLN surgery using both blue dye and a radiolabeled colloid mapping agent was encouraged.

Main Outcome Measure

The primary endpoint was the FNR of SLN surgery after chemotherapy in women who presented with cN1 disease. We examined the likelihood that the FNR in those with 2 or more SLNs examined was greater than 10%, the rate expected for women undergoing SLN surgery who present with clinically node-negative disease.

Results

Seven hundred fifty-six patients were enrolled from 136 institutions. Of 663 evaluable patients with cN1 disease, 649 underwent chemotherapy followed by both SLN surgery and ALND. A SLN could not be identified in 46 patients (7.1%). Only one SLN was excised in 78 patients (12.0%). Of the remaining 525 patients with 2 or more SLNs removed, no cancer was identified in the axillary lymph nodes of 215 patients yielding a pathological complete nodal response of 41.0% (95% CI: 36.7%–45.3%). In 39 patients, cancer was not identified in the SLNs but was found in lymph nodes obtained with ALND resulting in a FNR of 12.6% (90% Bayesian Credible Interval, 9.85%–16.05%).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among women with cN1 breast cancer receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy who had 2 or more SLNs examined, the FNR was not found to be 10% or less. Given this FNR threshold, changes in approach and patient selection that result in greater sensitivity would be necessary to support the use of SLN surgery as an alternative to ALND.

Trial Registration

clinicaltrials.gov; trial identifier NCT00881361.

INTRODUCTION

Axillary lymph node status is an important prognostic factor in breast cancer and is used to guide local, regional, and systemic treatment decisions. In patients with large primary tumors or involved lymph nodes, chemotherapy is often delivered preoperatively in order to assess response to chemotherapy and to increase the likelihood of breast conserving surgery. Residual axillary nodal disease is found in only 50–60% of breast cancer patients initially presenting with node-positive disease (cN1) who receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Accurate determination of axillary involvement after chemotherapy is important; however removing all axillary nodes to assess for residual nodal disease subjects many patients to the morbidity of surgery while potentially only a subset will benefit.

To avoid the complications associated with axillary lymph node dissection (ALND), it is preferable to identify nodal disease with the less invasive SLN procedure which results in less morbidity.1 SLN surgery is considered reliable for identifying axillary nodal disease in women initially presenting without clinically evident nodes (cN0). False negative results can occur when the SLNs do not contain cancer, but cancer is found in nodes obtained on completion ALND. False negative rates for SLN surgery range from 0% to 20%2–9 after chemotherapy in cN0 patients, with a meta-analysis reporting a FNR of 12%.10 Subsequently, investigators from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) B-27 trial including both cN0 and cN1 disease and reported a SLN FNR of 10.7% after chemotherapy9. However, the utility of SLN surgery following neoadjuvant chemotherapy for cN1 patients has been questioned, as the only available data has been from small series reporting FNRs ranging from 7% to 29.6%. Anthracyclines and taxane-based chemotherapy regimens have been shown to eradicate nodal disease in approximately 30–40% of patients.11 These patients would not benefit from ALND but may suffer complications of the procedure. In order to apply SLN surgery in this setting, an acceptably low FNR must be demonstrated. ACOSOG Z1071 was designed to determine the FNR of SLN surgery after chemotherapy in women initially presenting with axillary node-positive disease.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The ACOSOG Z1071 trial was a phase II clinical trial designed to determine the FNR for SLN surgery performed after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in women presenting with pathologically proven node-positive breast cancer. The institutional review boards of all participating institutions approved this study, and written informed consent was obtained from each patient before study entry.

Eligibility and Exclusion Criteria

We enrolled women older than 18 years of age who 1) had histologically proven clinical stage T0–4, N1–2, M0 primary invasive breast cancer according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 6th edition staging system (Table 1); 2) had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 or 1; 3) had completed or were planning to undergo neoadjuvant chemotherapy (the regimen was at the discretion of the patient’s medical team); and 4) had pre-chemotherapy axillary nodal disease confirmed by fine-needle aspiration or core needle biopsy. Patients with a history of prior ipsilateral axillary surgery, prior SLN surgery, or excisional lymph node biopsy for pathologic confirmation of axillary status were excluded. Patients were staged as cN1 according to the AJCC staging system: disease in movable axillary lymph nodes or cN2: disease in fixed or matted axillary lymph nodes.

Table 1.

Patient and Treatment Characteristics by Clinical Nodal Staging at Presentation*

| Characteristic | cN1 (n = 663) | cN2 (n = 38) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age, years | ||

|

| ||

| 18–39 | 120 (18.1) | 4 (10.5) |

|

| ||

| 40–49 | 213 (32.1) | 15 (39.5) |

|

| ||

| 50–59 | 197 (29.7) | 10 (26.3) |

|

| ||

| 60–69 | 112 (16.9) | 5 (13.2) |

|

| ||

| 70+ | 21 (3.2) | 4 (10.5) |

|

| ||

| Race (patient reported) | ||

|

| ||

| White | 537 (81.0) | 28 (73.7) |

|

| ||

| Black or African American | 95 (14.3) | 5 (13.2) |

|

| ||

| Asian | 18 (2.7) | 1 (2.6) |

|

| ||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2 (0.3) | 1 (2.6) |

|

| ||

| Not reported | 11 (1.6) | 3 (7.9) |

|

| ||

| Body mass index | ||

|

| ||

| Underweight/normal (BMI < 25.0) | 187 (28.2) | 9 (23.7) |

|

| ||

| Overweight/obese (BMI >= 25.0) | 475 (71.6) | 28 (73.7) |

|

| ||

| Unknown | 1 (0.2) | 1 (2.6) |

|

| ||

| Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status | ||

|

| ||

| 0 | 536 (80.8) | 26 (68.4) |

|

| ||

| 1 | 127 (19.2) | 12 (31.6) |

|

| ||

| Smoking status | ||

|

| ||

| Current | 81 (12.2) | 4 (10.5) |

|

| ||

| Never | 451 (68.0) | 30 (78.9) |

|

| ||

| Past | 104 (15.7) | 4 (10.5) |

|

| ||

| Not stated | 27 (4.1) | 0 |

|

| ||

| Concurrent conditions | ||

|

| ||

| Diabetes | 53 (8.0) | 4 (10.5) |

|

| ||

| Peripheral vascular disease | 3 (0.4) | 1 (2.6) |

|

| ||

| Arthritis | 44 (6.6) | 4 (10.5) |

|

| ||

| Cardiac disease | 169 (25.5) | 10 (26.3) |

|

| ||

| Clinical T category at diagnosis** | ||

|

| ||

| T0/Tis | 5 (0.8) | 2 (5.3) |

|

| ||

| T1 | 86 (13.0) | 5 (13.2) |

|

| ||

| T2 | 372*** (56.1) | 4 (10.5) |

|

| ||

| T3 | 175 (26.4) | 13 (34.2) |

|

| ||

| T4 | 25 (3.8) | 10 (26.2) |

|

| ||

| Approximated subtype | ||

|

| ||

| HER2-positive | 197 (29.7) | 12 (31.6) |

|

| ||

| Hormone receptor positive/HER2-negative | 301 (45.4) | 14 (36.8) |

|

| ||

| Triple receptor negative | 156 (23.5) | 10 (26.3) |

|

| ||

| Insufficient information to classify/no invasive breast tumor/prior breast surgery | 9 (1.4) | 2 (5.3) |

|

| ||

| Tumor histology | ||

| Invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) | 590 (89.0) | 30 (79.0) |

| Invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) | 37 (5.6) | 1 (2.6) |

| Mix of IDC and ILC | 11 (1.7) | 0 |

| Invasive carcinoma, other | 22 (3.0) | 5 (13.2) |

| DCIS | 2 (0.3) | 0 |

| no breast disease (stage T0 – no identifiable primary in the breast) | 3 (0.5) | 2 (5.3) |

|

| ||

| Type of axillary lymph node biopsy | ||

|

| ||

| Fine needle aspiration | 259 (39.1) | 13 (34.2) |

|

| ||

| Core needle biopsy | 404 (60.9) | 25 (65.8) |

|

| ||

| Clip placed in axilla | ||

|

| ||

| Yes | 214 (32.3) | 16 (42.1) |

|

| ||

| No | 448 (67.6) | 22 (57.9) |

|

| ||

| Not stated | 1 (0.2) | 0 |

|

| ||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimen | ||

|

| ||

| Contained an anthracycline and a taxane | 499 (75.3) | 24 (63.2) |

|

| ||

| Contained an anthracycline but not a taxane | 41 (6.2) | 3 (7.9) |

|

| ||

| Contained a taxane but not an anthracycline | 112 (16.9) | 10 (26.3) |

|

| ||

| Contained neither an anthracycline nor a taxane | 11 (1.7) | 1 (2.6) |

|

| ||

| Reason chemotherapy discontinued | ||

|

| ||

| Chemotherapy completed (not discontinued) | 609 (91.9) | 33 (86.8) |

|

| ||

| Disease progression | 6 (0.9) | 1 (2.6) |

|

| ||

| Intolerable adverse effects | 38 (5.7) | 4 (10.5) |

|

| ||

| Refusal | 5 (0.7) | 0 |

|

| ||

| Lack of tumor response | 3 (0.4) | 0 |

|

| ||

| Physician discretion | 1 (0.2) | 0 |

|

| ||

| Desire for alternative therapy | 1 (0.2) | 0 |

|

| ||

| Findings on clinical examination of axilla after chemotherapy | ||

|

| ||

| No palpable adenopathy | 556 (83.9) | 26 (68.4) |

|

| ||

| Palpable lymph nodes | 76 (11.5) | 8 (21.1) |

|

| ||

| Fixed or matted lymph nodes | 2 (0.3) | 2 (5.3) |

|

| ||

| Not reported | 29 (4.4) | 2 (5.3) |

|

| ||

| Type of breast surgery after chemotherapy | ||

|

| ||

| Partial mastectomy | 266 (40.1) | 11 (28.9) |

|

| ||

| Total mastectomy | 395 (59.6) | 25 (65.8) |

|

| ||

| None | 2 (0.3) | 2 (5.3) |

|

| ||

| Type of axillary surgery | ||

|

| ||

| SLN surgery only | 2 (0.3) | 0 |

|

| ||

| SLN attempted but no SLN identified; ALND | 46 (6.9) | 4 (10.5) |

|

| ||

| SLN with SLN identified; ALND | 603 (91.0) | 34 (89.5) |

|

| ||

| ALND | 12 (1.8) | 0 |

one patient underwent a partial mastectomy prior to chemotherapy

cN1: disease in movable axillary lymph nodes; cN2: disease in fixed or matted axillary lymph nodes.

cT0: no evidence of disease in the breast; cT1: breast tumor size ≤ 2 cm; cT2: breast tumor more than 2 cm but at most 5 cm; cT3: breast tumor size > 5 cm; cT4: tumor extension to chest wall or skin.

Abbreviations: ALND, axillary lymph node dissection; BMI, body mass index; SLN, sentinel lymph node.

Surgical Intervention and Nodal Evaluation

Breast cancer surgery was performed within 84 days after completion of chemotherapy. After chemotherapy and within 4 weeks before surgery, patients underwent a physical examination and axillary ultrasonography. At surgery, patients had appropriate treatment of the primary tumor and underwent SLN surgery and then ALND.

SLN surgery allows surgeons to identify the first lymph node(s) along the lymphatic drainage pathway from the primary tumor in the breast to the axillary lymph node basin. It requires injection of a radiolabelled colloid, blue dye, or a combination (“mapping agents”) in the breast which is taken up by the breast lymphatics as they travel to the axillary nodes. If radiolabelled colloid is used, a gamma probe identifies radioactivity in the lymph nodes in the axilla. If blue dye is used, blue stained lymphatic channels visualized during surgery are followed to lymph nodes where the blue dye accumulates. Additionally, the axilla is carefully palpated and any palpably abnormal lymph nodes are identified. Lymph nodes that are radioactive, blue, or palpably abnormal are considered SLNs and are resected and submitted for pathological analysis.

In ACOSOG Z1071, SLN mapping with both blue dye (isosulfan blue or methylene blue) and radiolabeled colloid mapping agents was recommended to maximize the likelihood of SLN identification and to minimize the possibility of missing SLNs which could result in a false negative event. All SLNs were excised and submitted before the ALND was performed. The protocol required that at least 2 SLNs be resected. Each SLN was examined with hematoxylin-eosin staining and positive SLNs were defined as those with metastases larger than 0.2 mm as per the AJCC 6th edition staging system. Nodes removed at ALND were evaluated by hematoxylin-eosin staining using institutional standard operating procedures.

Statistical Analysis

This study was designed to evaluate the primary and secondary endpoints in the cN1 cohort independently of that in the cN2 cohort. The primary aim was to examine the FNR of SLN surgery after chemotherapy when at least 2 SLNs are excised. A secondary aim was to determine the pathologic complete nodal response (pCR) rate where a nodal pCR is the pathologic finding of negative nodes (pN0) on the basis of SLN surgery and ALND.

In the cN1 cohort, a Bayesian approach was chosen to determine whether the FNR was greater than 10%,,12,13 the rate expected for SLN surgery in women who initially present with clinically negative axillary lymph nodes. Assuming the number of women with negative SLN results after chemotherapy, X, has a binomial (n, θ) distribution, where θ is the probability of a false-negative SLN result and its prior distribution is a uniform (0,1) distribution, then the posterior distribution for θ is a Beta(x+1,n−x+1) distribution. The SLN FNR is considered too high if there is a greater than 95% chance that the FNR is greater than 10%. With a sample size of 300 patients, this translated to concluding that the SLN FNR is greater than 10% if 39 or more patients are found to have a false negative SLN finding. Operating characteristics of this design based on 10,000 simulations were such that the probability of concluding that that the true FNR is larger than 10% is 0.053 when the true FNR is 10% and 0.852 when the true FNR is 15%. A two-sided 90% Bayesian credible interval (BCI) for the true FNR was constructed.

In an exploratory analysis, Fisher exact tests and multivariable logistic regression modeling with Score statistics and likelihood ratio tests were used on the likelihood of a false-negative SLN finding. All tests were 2-sided.

In the cN2 cohort, it was anticipated that 43 women with cN2 disease would be enrolled who would have at least 2 SLNs examined after chemotherapy and have residual nodal disease. However, only 14 such women were enrolled and as such a 95% binomial confidential interval for the FNR in this patient population was constructed.

A 95% binomial confidence interval was constructed for the pathologic complete response rate.

The database used for these analyses was locked May 1, 2013. Statistical analyses were carried out using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The trial was registered on clinicaltrials.gov with trial identifier NCT00881361.

RESULTS

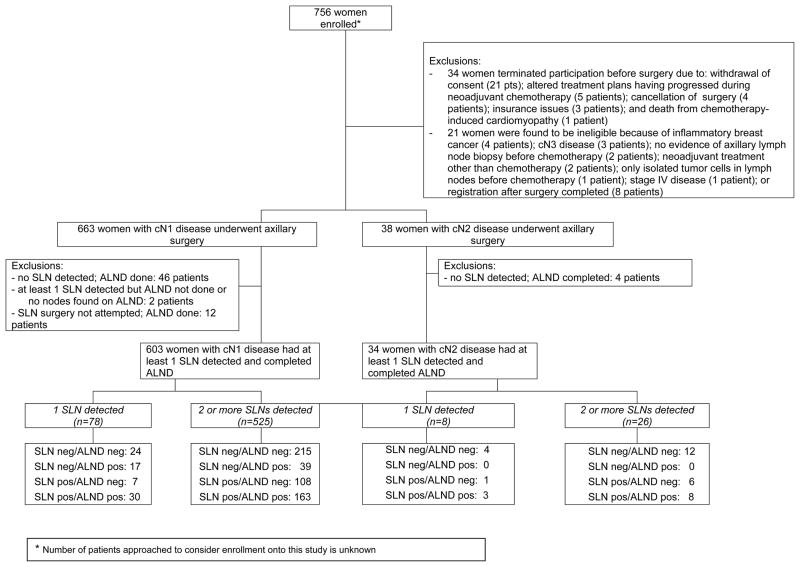

Seven hundred fifty-six women with clinical stage T0–4, N1–2, M0 breast cancer who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy were enrolled between July 2009 and June 2011 from 136 institutions. Twenty-one women were ineligible, and 34 patients withdrew from the study before surgery (Figure 1). Patient, disease, and chemotherapy characteristics for the remaining 701 women are presented in Table 1 by clinical nodal stage prior to chemotherapy. A total of 663 women had cN1 disease, and 38 had cN2 disease. The chemotherapy regimens varied, but the majority included an anthracycline and taxane (74.6%, see Table 1). The duration of chemotherapy varied from 1 month to 7 months (median, 4 months). Fifty-nine patients (8.4%) discontinued chemotherapy early because of disease progression (7 patients; 1.0%); intolerable adverse effects (42 patients; 6.0 %); refusal (5 patients; 0.7%); lack of tumor response (3 patients; 0.4%); physician discretion (1 patient; 0.1%); or desire for alternative therapy (1 patient; 0.1%).

Figure 1.

After completion of chemotherapy, clinical examination of the axilla revealed no palpable lymphadenopathy in 582 patients (83.0%), palpable nodes in 84 patients (12.0%), and fixed or matted nodes in 4 patients (0.6%). Results of palpation were not reported in 31 patients (4.4%).

Of the 701 evaluable women, 2 women (0.3%) underwent SLN surgery only; 687 women (98.0%) underwent both SLN surgery and ALND; and 12 (1.7%) underwent ALND only.

SLN Surgery

Of the 689 women who underwent SLN surgery, 28 (4.1%) had mapping performed with blue dye only, 116 (16.8%) had mapping with radiolabeled colloid only, and 545 (79.1%) had mapping with both blue dye and radiolabeled colloid.

At least 1 SLN was detected in 639 (92.7%; 95% CI, 90.5%–94.6%) of these 689 women. Rates of detection of at least 1 SLN were 92.9% (n=605; 95% CI, 90.7%–94.8%) in the 651 patients with cN1 disease and 89.5% (n=34; 95% CI, 75.2%–97.1%) in the 38 patients with cN2 disease.

FNR in Women With cN1 Disease and at Least 2 SLNs Examined

There were 525 patients with cN1 disease who had at least 2 SLNs excised and went on to complete ALND. Pathologic examination of the SLNs and nodes removed on ALND found no residual nodal disease in 215 of these patients yielding a nodal pathological complete response rate of 41.0% (95% CI: 36.7%–45.3%). Among the remaining 310 patients, residual nodal disease was confined to the SLNs in 108 patients (20.6%); confined to the nodes removed on ALND in 39 patients (7.4%); and present in nodes from both procedures in 163 patients (31.1%). Thus, 39 of the 310 patients with residual nodal disease had a false-negative SLN finding, a FNR of 12.6% (90% Bayesian credibility interval: 9.85%–16.05%).

Bivariable analyses found that the likelihood of a false-negative SLN finding was significantly decreased when the mapping was performed with the combination of blue dye and radiolabeled colloid (P = .052; FNR: 10.8% vs. 20.3%) and by examination of at least 3 SLNs (P = .007: 9.1% vs. 21.1%) (Table 3). Multivariable logistic modeling revealed that, once the number of SLNs examined (2 vs. 3 or more) was accounted for, no other factors made a significant contribution in explaining the variability in likelihood of a false-negative SLN finding.

Table 3.

Factors Affecting the Likelihood of a False-Negative Finding on SLN Surgery in the 310 Women with cN1 Disease at Presentation, 2 or More SLNs Examined, and Residual Nodal Disease after Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy

| False-Negative SLN Findings | FNR and 95% CI | Fisher’s exact test p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age | |||

| 18.0–49.9 years | 20/150 | 13.3% (8.3–19.8%) | 0.734 |

| 50.0+ years | 19/160 | 11.9% (7.3–17.9%) | |

|

| |||

| Body mass index | |||

| Overweight/obese (≥ 25.0) | 25/227 | 11.0% (7.3–15.8%) | 0.179 |

| Underweight/normal (< 25.0) | 14/83 | 16.9% (9.5–26.7%) | |

|

| |||

| cT category prior to chemotherapy | |||

| Tis/T0/T1/T2 | 32/225 | 14.2% (9.9–19.5%) | 0.182 |

| T3/T4 | 7/85 | 8.2% (3.4–16.2%) | |

|

| |||

| Chemotherapy duration (months) | |||

| 4.0 or less | 20/201 | 10.0% (6.2–15.0%) | 0.073 |

| 4.1 or more | 19/109 | 17.4% (10.8–25.9%) | |

|

| |||

| Palpable/fixed/matted Nodes after chemotherapy* | |||

| yes | 10/52 | 19.2% (9.6–32.5%) | 0.166 |

| no | 28/247 | 11.3% (7.7–16.0%) | |

|

| |||

| Mapping agents used | |||

| single | 12/59 | 20.3% (11.0–32.8%) | 0.052 |

| dual | 27/251 | 10.8% (7.2–15.3%) | |

|

| |||

| Multiple injection sites** | |||

| yes | 5/70 | 7.1% (2.4–15.9%) | 0.206 |

| no | 30/225 | 13.3% (9.2–18.5%) | |

|

| |||

| Number of SLNs examined | |||

| 2 | 19/90 | 21.1% (13.2–31.0%) | 0.007 |

| 3 or more | 20/220 | 9.1% (5.6–13.7%) | |

not reported in 11 patients

not reported in 15 patients

Women With cN2 Disease and at Least 2 SLNs Examined

Among the 26 women with cN2 disease with at least 2 SLNs excised followed by ALND; 12 patients had no residual nodal disease found resulting in a pathological complete response rate of 46.1% (95%CI: 26.6–66.6%). Fourteen patients had residual nodal disease either confined to the SLNs (6 patients) or present in both SLNs and nodes removed on ALND (8 patients) yielding a FNR of 0% (95%CI: 0–23.2%).

DISCUSSION

This multicenter trial showed that the FNR of SLN surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with cN1 breast cancer and at least 2 SLNs identified at the time of surgery was 12.6%,. higher than the prespecified threshold of 10%. This threshold was considered acceptable based on prior studies of SLN surgery reporting a 10–12% FNR following chemotherapy in cN0 patients10.

Although our findings suggest that one cannot reliably detect all axillary lymph node metastases in cN1 breast cancer patients following chemotherapy by SLN procedures, we did identify important factors influencing the likelihood of a false-negative SLN. The FNR was significantly lower when a dual-agent mapping technique (10.8%) relative to single agent mapping (20.3%, p=0.05) technique was utilized. The FNR with dual agent mapping reported in this study is similar to the findings from the NSABP B-27 trial where investigators reported a FNR of 9.3% with dual agent mapping in predominantly cN0 but some cN1 patients.13 After chemotherapy, the axilla often has more fibrosis, making evaluation of lymphatic drainage and surgical dissection more challenging. Using two mapping agents with different molecular sizes and transit times is an important surgical standard that should be adhered to for SLN surgery after chemotherapy.

Our study also found that the FNR is lower when 3 or more SLNs are evaluated relative to only 2 SLNs being evaluated. In the NSABP B-27 study this issue was not addressed. The NSABP B-32 trial, in which SLN surgery was performed before any chemotherapy, reported that there was a significant decrease in the FNR as more SLNs were resected: 18% with 1 SLN resected, 10% with 2 SLNs resected, and 7% with 3 SLNs resected.14 Similarly, Hunt et al. showed that removal of fewer than 2 SLNs was associated with a higher FNR in patients with clinically node-negative disease undergoing SLN surgery after chemotherapy.15 As the accuracy of any sampling test is dependent on the amount of material sampled, these results are not surprising.

A shortcoming of this study is that patients who had node-positive disease prior to planned chemotherapy could be enrolled before, during, or after chemotherapy regardless of type or length of therapy, reason for discontinuing chemotherapy, or nodal response after chemotherapy (based on physical examination or axillary ultrasound). More appropriate candidates for SLN surgery may have been patients with the highest likelihood of nodal response and lowest likelihood of residual nodal disease and those with normalization of nodal architecture on ultrasonography. As such, patients with significant residual nodal disease or poor clinical or radiologic response to chemotherapy are most likely poor candidates for SLN surgery. Until further data are available, we recommend that SLN surgery after chemotherapy not be performed in patients with clinically evident residual nodal disease or poor response to chemotherapy.

In summary, the ACOSOG Z1071 trial found that among women presenting with cN1 breast cancer who received chemotherapy and had 2 or more SLNs examined, the FNR was 12.6% (90% BCI, 9.85%–16.05%). Both the use of dual mapping agents and recovery of more than 2 SLNs were associated with a lower likelihood of false-negative SLN findings.

CONCLUSION

Among women with cN1 breast cancer receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy who had 2 or more SLNs examined, the FNR with SLN surgery exceeded the pre-specified threshold of 10%. Given this acceptability threshold, changes in approach and patient selection that result in greater sensitivity would be necessary to support use of SLN surgery as an alternative to ALND in this patient population.

Table 2.

Details of SLN Surgery

| Variable | cN1 (n = 651) | cN2 (n = 38) |

|---|---|---|

| Mapping agent used | ||

| Blue dye | 25 (3.8) | 3 (7.9) |

|

| ||

| Radiolabelled colloid | 109 (16.7) | 7 (18.4) |

|

| ||

| Both | 517 (79.4) | 28 (73.7) |

|

| ||

| Timing of radiolabelled colloid injection | ||

| Day before surgery | 160 (24.6) | 5 (13.2) |

|

| ||

| Morning of surgery | 466 (71.6) | 30 (78.9) |

|

| ||

| Not used | 25 (3.8) | 3 (7.9) |

|

| ||

| Injection site(s) | ||

| Subareolar/periareolar | 404 (62.1) | 31 (81.6) |

|

| ||

| Peritumoral | 56 (8.6) | 1 (2.6) |

|

| ||

| Intradermal | 17 (2.6) | 2 (5.3) |

|

| ||

| Multiple sites | 147 (22.6) | 2 (5.3) |

|

| ||

| Not specified | 27 (4.1) | 2 (5.3) |

|

| ||

| Number of SLNs examined | ||

| 0 | 46 (7.1) | 4 (10.5) |

|

| ||

| 1 | 78 (12.0) | 8 (21.1) |

|

| ||

| 2 | 155 (23.8) | 10 (26.3) |

|

| ||

| 3 | 148 (22.7) | 6 (15.8) |

|

| ||

| 4 | 90 (13.8) | 5 (13.2) |

|

| ||

| 5+ | 134 (20.6) | 5 (13.2) |

Abbreviation: SLN, sentinel lymph node.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This work was supported by National Cancer Institute grant U10 CA76001 to the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures:

All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and none were reported.

Role of the Sponsor: The National Cancer Institute had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Additional Contributions: We thank the ACOSOG staff and David Ota, MD (Duke University, Durham, North Carolina). These individuals contributed to study design, manuscript review, or both; none received compensation for their contributions. We also thank the patients with breast cancer who participated in the study and their caregivers, and we thank the investigators and their research teams. We thank Sue Paxton and Amy Oeltjen for their work with data quality, Karla Ballman for initial statistical planning, and Susan Budinger for protocol development. We thank Stephanie Deming for her assistance with critical editing of the manuscript.

Author Contributions: Judy Boughey and Vera Suman had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Boughey, Hunt, Leitch.

Acquisition of data: Boughey, Hunt, Mittendorf.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Boughey, Haffty, Hunt, Leitch, Mittendorf, Suman, Symmans.

Drafting of the manuscript: Boughey, Hunt, Suman.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Ahrendt, Boughey, Bowling, Buchholz, Byrd, Flippo-Morton, Haffty, Hunt, Julian, Kuerer, Leitch, Le-Petross, McLaughlin, Mittendorf, Nelson, Ollila, Suman, Symmans, Taback, Wilke.

Statistical analysis: McCall, Suman.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Boughey, Hunt, Nelson.

Study supervision: Boughey, Hunt.

References

- 1.Veronesi U, Paganelli G, Viale G, et al. A randomized comparison of sentinel -node biopsy with routine axillary dissection in breast cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2003 Aug 7;349(6):546–553. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stearns V, Ewing CA, Slack R, Penannen MF, Hayes DF, Tsangaris TN. Sentinel lymphadenectomy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer may reliably represent the axilla except for inflammatory breast cancer. Annals of surgical oncology. 2002 Apr;9(3):235–242. doi: 10.1007/BF02573060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brady EW. Sentinel lymph node mapping following neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. The breast journal. 2002 Mar-Apr;8(2):97–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4741.2002.08205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller AR, Thomason VE, Yeh IT, et al. Analysis of sentinel lymph node mapping with immediate pathologic review in patients receiving preoperative chemotherapy for breast carcinoma. Annals of surgical oncology. 2002 Apr;9(3):243–247. doi: 10.1007/BF02573061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balch GC, Mithani SK, Richards KR, Beauchamp RD, Kelley MC. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy after preoperative therapy for stage II and III breast cancer. Annals of surgical oncology. 2003 Jul;10(6):616–621. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piato JR, Barros AC, Pincerato KM, Sampaio AP, Pinotti JA. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. A pilot study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2003 Mar;29(2):118–120. doi: 10.1053/ejso.2002.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reitsamer R, Peintinger F, Rettenbacher L, Prokop E. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer patients after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Surg Oncol. 2003 Oct;84(2):63–67. doi: 10.1002/jso.10294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz GF, Meltzer AJ. Accuracy of axillary sentinel lymph node biopsy following neoadjuvant (induction) chemotherapy for carcinoma of the breast. The breast journal. 2003 Sep-Oct;9(5):374–379. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4741.2003.09502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mamounas EP, Brown A, Anderson S, et al. Sentinel node biopsy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer: results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Protocol B-27. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Apr 20;23(12):2694–2702. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xing Y, Foy M, Cox DD, Kuerer HM, Hunt KK, Cormier JN. Meta-analysis of sentinel lymph node biopsy after preoperative chemotherapy in patients with breast cancer. The British journalof surgery. 2006 May;93(5):539–546. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hennessy BT, Hortobagyi GN, Rouzier R, et al. Outcome after pathologic complete eradication of cytologically proven breast cancer axillary node metastases following primary chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Dec 20;23(36):9304–9311. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.5023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spiegelhalter DJ, Abrams KR, Myles JP. Bayesian Approaches to Clinical Trials and Health-Care Evaluation. Wiley & Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berry DA, Stangl DL, editors. Bayesian Biostatistics. CRC Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krag DN, Anderson SJ, Julian TB, et al. Technical outcomes of sentinel-lymph-node resection and conventional axillary-lymph-node dissection in patients with clinically node-negative breast cancer: results from the NSABP B-32 randomised phase III trial. The lancet oncology. 2007 Oct;8(10):881–888. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70278-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunt KK, Yi M, Mittendorf EA, et al. Sentinel Lymph Node Surgery After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy is Accurate and Reduces the Need for Axillary Dissection in Breast Cancer Patients. Annals of surgery. 2009 Aug 27;250:558–566. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b8fd5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]