Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To determine whether tramadol has a protective effect against lung injury induced by skeletal muscle ischemia-reperfusion.

METHODS:

Twenty Wistar male rats were allocated to one of two groups: ischemia-reperfusion (IR) and ischemia-reperfusion + tramadol (IR+T). The animals were anesthetized with intramuscular injections of ketamine and xylazine (50 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg, respectively). All of the animals underwent 2-h ischemia by occlusion of the femoral artery and 24-h reperfusion. Prior to the occlusion of the femoral artery, 250 IU heparin were administered via the jugular vein in order to prevent clotting. The rats in the IR+T group were treated with tramadol (20 mg/kg i.v.) immediately before reperfusion. After the reperfusion period, the animals were euthanized with pentobarbital (300 mg/kg i.p.), the lungs were carefully removed, and specimens were properly prepared for histopathological and biochemical studies.

RESULTS:

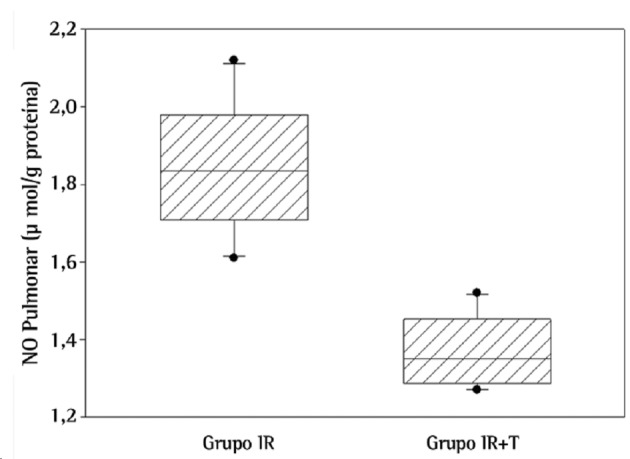

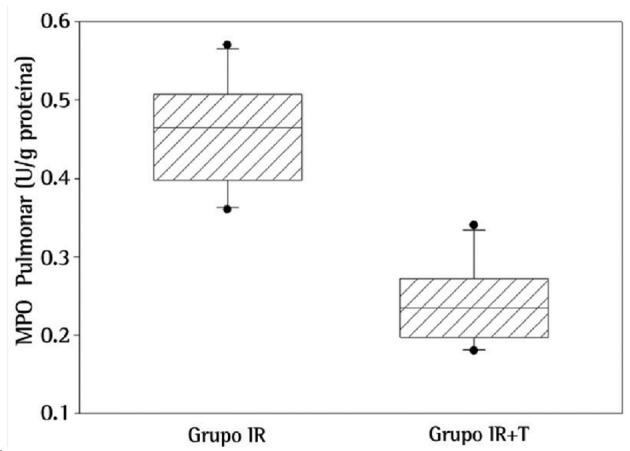

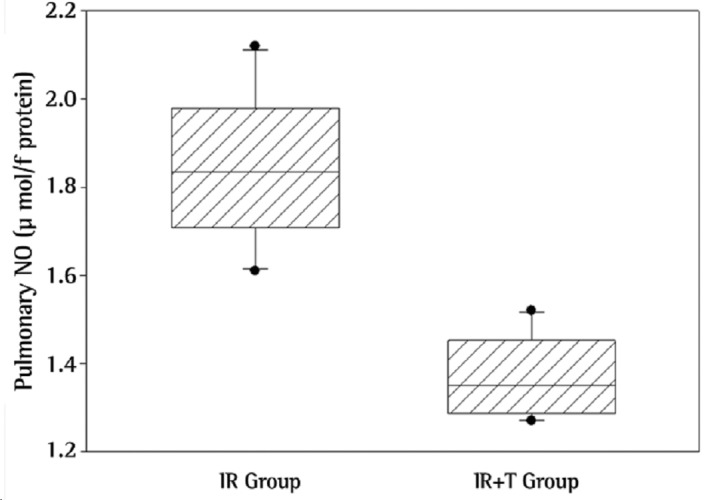

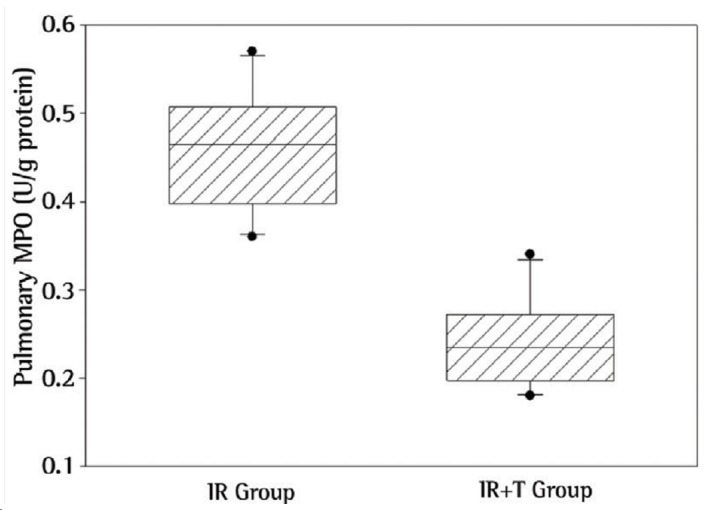

Myeloperoxidase activity and nitric oxide levels were significantly higher in the IR group than in the IR+T group (p = 0.001 for both). Histological abnormalities, such as intra-alveolar edema, intra-alveolar hemorrhage, and neutrophil infiltration, were significantly more common in the IR group than in the IR+T group.

CONCLUSIONS:

On the basis of our histological and biochemical findings, we conclude that tramadol prevents lung tissue injury after skeletal muscle ischemia-reperfusion.

Keywords: Tramadol; Muscle, skeletal; Ischemic attack, transient; Lung Injury

Introduction

Ischemia-reperfusion injury is one of the most common types of cell injury that occurs in a variety of surgical practices. Reperfusion of ischemic organs can result in tissue injury, which manifests as microvascular and parenchymal cell dysfunction. The mechanisms underlying ischemia-reperfusion injury have been previously described; polymorphonuclear leukocytes and reactive oxygen metabolites have been indicated to have pivotal roles in the etiology.( 1 - 3 )

Skeletal muscle ischemia-reperfusion resulting from trauma, limb revascularization, orthopedic surgery, free flap reconstruction, or any other etiology not only leads to muscle damage itself but also causes injury involving a severe destruction of remote organs. Considerable advances have been made in the understanding of the mechanisms of this systemic response regarding the skeletal muscle ischemia-reperfusion sequence. Remote organs with intense microcapillary systems, such as the lungs, are prone to developing this type of systemic injury.( 3 , 4 )

Various investigators have demonstrated that the opioid pathway is involved in tissue preservation during hypoxia or ischemia, and this protection is mediated via the delta opioid receptor.( 5 , 6 ) Tramadol hydrochloride is an effective analgesic drug used for severe acute and chronic pain conditions. It has a weak affinity to the µ-opioid receptor and inhibits the reuptake of monoamines in the central nervous system, thereby activating the descending inhibitory systems.( 7 , 8 ) Recent research discloses that tramadol decreases lipid peroxidation and regulates noradrenalin uptake, and, therefore, these therapeutic properties are used for the management of myocardial ischemia.( 9 )

The aim of the present study was to investigate the potential protective effect of tramadol hydrochloride on lung ischemia-reperfusion injury induced by the hind limb model by means of histopathological evaluation and determination of inflammatory responses via myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity and nitric oxide (NO) levels in the lung tissue of rats.

Methods

All of the animals used in the present research were properly cared in accordance with the norms of the Laboratory of Animal Experimentation at the Islamic Azad University Faculty of Specialized Veterinary Sciences, in Tehran, Iran. The study was approved by the Animal Research Ethics Committee of the Department of Veterinary Surgery of the university.

Twenty Wistar male rats, weighing 250-300 g (12-15 weeks old), were used in the present study. All of the rats were maintained under constant room temperature and standard conditions, with ad libitum access to water and commercial food, and placed in individual plastic cages with soft bedding. The animals were divided randomly into two experimental groups of ten rats each: ischemia-reperfusion (IR) group and ischemia-reperfusion + tramadol (IR+T) group. Anesthesia was induced using ketamine and xylazine (i.m., 50 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg, respectively). After induction of anesthesia, the left hind limb was completely clipped. After clipping, disinfecting, and dropping, a skin incision was made on the medial surface of the left hind limb. The femoral artery and vein were isolated from the surrounding tissues, and the femoral artery was exposed and clamped with a mini bulldog forceps. Prior to the occlusion of the femoral artery, 250 IU heparin was administered via the jugular vein in order to prevent clotting. All of the animals underwent 2-h ischemia by the occlusion femoral artery with a vascular clamp and 24-h reperfusion. The animals were maintained in dorsal recumbency and kept anesthetized throughout the duration of the ischemic period. Additional doses of the anesthetics were given as necessary in order to maintain anesthesia during the experiment. Body temperature was maintained with a heating pad under anesthesia. The animals in the IR+T group were administered tramadol i.v. (20 mg/kg)( 10 ) immediately before reperfusion. Following the ischemic period, the vascular clamp was removed, and the surgical site was routinely closed. After the surgery, fluid losses were replaced by intraperitoneal administration of 5-mL warm isotonic saline, and the rats were returned to their cages with ad libitum access to commercial food and water during the reperfusion period. After 24 h of reperfusion, the rats were euthanized with an overdose of intraperitoneal pentobarbital injection (300 mg/kg), and the left lungs were harvested and fixed in 10% formaldehyde for histopathological examination under light microscopy. The right lungs were removed and stored at –20°C for analysis. The lung tissue homogenate and supernatant samples were prepared as described by Yildirim et al.( 11 )

The biochemical assay consisted of determining MPO activity and NO levels in lung tissue. The activity of MPO( 12 ) was analyzed spectrophotometrically as described elsewhere, whereas NO levels in lung tissue were measured by the Griess reaction.( 13 )

All of the left lung tissue samples were fixed in 10% formalin solution and processed routinely (embedded in paraffin blocks, the anterior lung region being sectioned into 6-µm sections, and stained with H E). The severity of lung injury was determined by a pathologist who was blinded to the experiment. Lung injury was classified into four levels, as follows: level 0, no diagnostic change; level 1, mild neutrophil leukocyte infiltration and mild to moderate interstitial congestion; level 2, moderate neutrophil leukocyte infiltration, perivascular edema formation, and partial destruction of pulmonary architecture; and level 3, dense neutrophil leukocyte infiltration and complete destruction of pulmonary structure.( 14 ) A total of four slides from each lung sample were randomly screened, and the mean level was considered representative of the sample.

Statistical analyses were carried out with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 11.2 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The distribution of the groups was analyzed with one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Biochemical results showed normal distribution, and one-way ANOVA was used. Histopathological results were analyzed using Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U tests. Values of p < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

All of the rats survived until the end of the study period.

Regarding biochemical results, NO levels were significantly higher in the lungs of the rats in the IR group than in those of the rats in the IR+T group (p = 0.001; Figure 1). Likewise, MPO activity, a novel indicator for neutrophil function, was significantly higher in the IR group than in the IR+T group (p = 0.001; Figure 2).

Figure 1. Levels of nitric oxide (NO) in lung tissue between the groups studied (p = 0.001).

Figure 2. Myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity in lung tissue between the groups studied (p = 0.001).

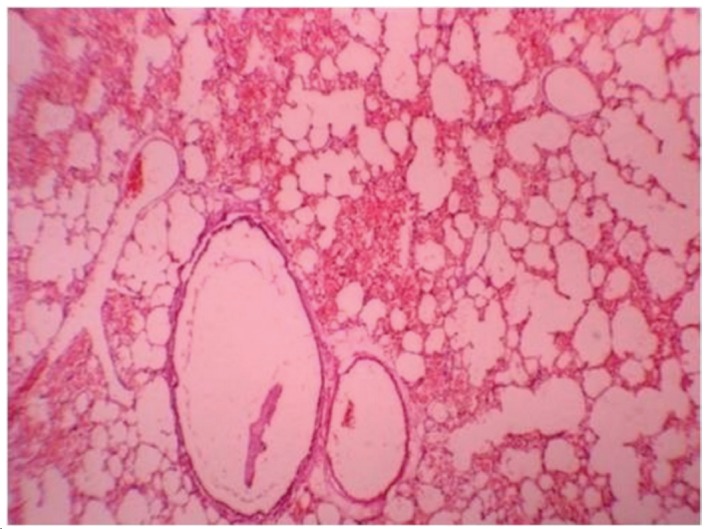

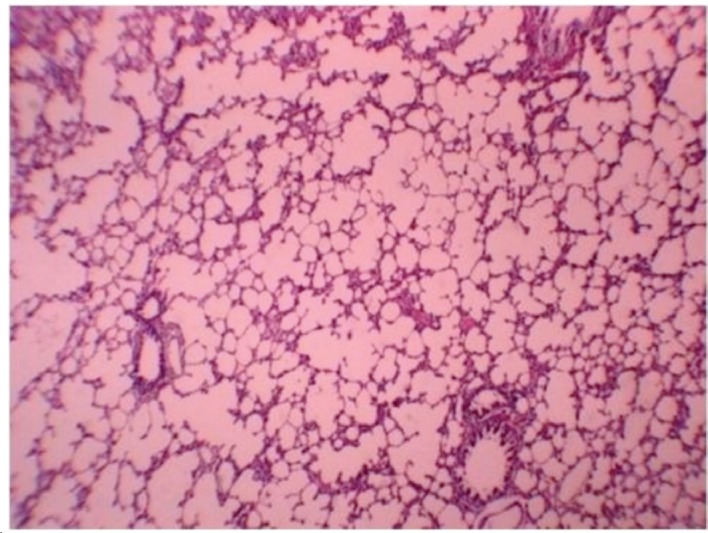

Figure 3 illustrates a representative photomicrograph of lung tissue of the rats in the IR group 24 h after reperfusion. Histological changes in the IR group included intra-alveolar edema, intra-alveolar hemorrhage, and neutrophil infiltration. The mean level of lung injury in the IR group was 2.10 ± 0.89. These pathological changes, particularly neutrophil infiltration, were much less common in the IR+T group (Figure 4). One animal in the IR+T group presented no injury, whereas the level of lung injury in the other animals ranged from 1 to 2 (mean, 1.70 ± 0.23). Histopathologically, there was a significant difference between two groups (p = 0.035).

Figure 3. Photomicrograph under light microscopy. Lung tissue of a rat in the ischemia-reperfusion group showing extensive intra-alveolar hemorrhage (HE; magnification, Ã-40).

Figure 4. Photomicrograph under light microscopy. Lung tissue of a rat in the ischemia-reperfusion + tramadol group showing fewer histological changes and better preserved, practically normal structures (HE; magnification, Ã-40).

Discussion

The lung is one of the most important target organs in multiple organ dysfunction syndrome or multiple system organ failure caused by severe injury. Lungs can be damaged by indirect injuries caused by the intestine, liver, and skeletal muscle reperfusion, as well as by circulatory shock.( 15 , 16 ) The mechanism of respiratory failure after ischemia-reperfusion injury is a complex process which is associated with the activation of systemic inflammatory mediators, including bacteriotoxins, immunocytokines, and inflammatory mediators, such as TNF and interleukins.( 17 , 18 ) TNF and NO are significant determinants of the lung injury process, which is caused by lower extremity ischemia-reperfusion,( 19 , 20 ) whereas MPO is an index for the accumulation of activated leukocytes in tissues and is associated with an overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS); therefore, leukocyte accumulation, high MPO activity, and excessive ROS production exist together in the inflammatory process. Overproduction of ROS results in a quick depletion of antioxidant capacity of the body, which consequently leads to the damage of target organs.( 21 , 22 )

Animal studies showed that opioids can act as a trigger for both phases of ischemic preconditioning,( 23 ) and serotonin augments( 24 ) or attenuates( 25 ) this phenomenon depending on the concentration. Mayfield et al.( 6 ) and Chien et al.( 5 ) have demonstrated that the opioid pathway is involved in tissue preservation during hypoxia or ischemia. It has been proven that morphine has cardioprotective effects during ischemia-reperfusion.( 26 , 27 ) Factors such as respiratory depression and histamine release are the disadvantages of morphine usage during the postoperative period.( 28 ) Tramadol is a centrally acting analgesic drug with negligible respiratory depressant action, very low tolerance, and physical dependence liability. The use of tramadol (10 and 20 mg/kg) showed a protective effect against transient forebrain ischemia in rats.( 10 ) In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that 20 mg/kg of tramadol could protect the lungs from remote organ injury after skeletal muscle ischemia-reperfusion. Higher doses of tramadol should be investigated in order to determine whether higher doses would have a higher protective effect.

The present study, in concert with previous ones,( 29 - 31 ) confirmed that lower limb ischemia-reperfusion could induce acute lung injury in rats. We demonstrated that the acute lung injury induced by lower limb ischemia-reperfusion could be mitigated by tramadol. Our data demonstrate that tramadol significantly decreases the severity of acute lung injury, the infiltration of macrophages and polymorphonuclear leukocytes in the lungs, pulmonary vascular permeability, and intra-alveolar hemorrhage, as well as inhibiting cellular apoptosis in the lungs after skeletal muscle ischemia-reperfusion injury. These results suggest the possibility of clinical application of tramadol in ischemia-reperfusion injury of the lung. Different dosages, alternative time protocols, and forms of tramadol administration for lung injury induced by skeletal muscle ischemia-reperfusion should be investigated in future studies.

Footnotes

Study carried out in the Department of Veterinary Surgery, Faculty of Specialized Veterinary Science, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Hesarak, Tehran, Iran.

Financial support: None.

Contributor Information

Mohammad Ashrafzadeh Takhtfooladi, Department of Veterinary Surgery, Faculty of Specialized Veterinary Science, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran..

Amirali Jahanshahi, Department of Veterinary Surgery, Faculty of Specialized Veterinary Science, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran..

Amir Sotoudeh, Assistant Professor. Faculty of Veterinary Science, Kahnooj Branch, Islamic Azad University, Kerman, Iran..

Gholamreza Jahanshahi, Department of Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology, School of Dentistry, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran..

Hamed Ashrafzadeh Takhtfooladi, Faculty of Veterinary Science, Karaj Branch, Islamic Azad University, Alborz, Iran..

Kimia Aslani, Faculty of Veterinary Science, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran..

References

- 1.Zimmerman BJ, Granger DN. Mechanisms of reperfusion injury. Am J Med Sci. 1994;307(4):284–292. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199404000-00009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00000441-199404000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atahan E, Ergun Y, Belge Kurutas E, Cetinus E, Guney Ergun U. Ischemia-reperfusion injury in rat skeletal muscle is attenuated by zinc aspartate. J Surg Res. 2007;137(1):109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.05.036. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2006.05.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welbourn CR, Goldman G, Paterson IS, Valeri CR, Shepro D, Hechtman HB. Pathophysiology of ischaemia reperfusion injury: central role of the neutrophil. Br J Surg. 1991;78(6):651–655. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800780607. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/bjs.1800780607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schoenberg MH, Beger HG. Reperfusion injury after intestinal ischemia. Crit Care Med. 1993;21(9):1376–1386. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199309000-00023. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00003246-199309000-00023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chien S, Oeltgen PR, Diana JN, Salley RK, Su TP. Extension of tissue survival time in multiorgan block preparation with a delta opioid DADLE ([D-Ala2, D-Leu5]-enkephalin) J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;107(3):964–967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayfield KP, D'Alecy LG. Delta-1 opioid receptor dependence of acute hypoxic adaptation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;268(1):74–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raffa RB, Friderichs E, Reimann W, Shank RP, Codd EE, Vaught JL. Opioid and nonopioid components independently contribute to the mechanism of action of tramadol, an 'atypical' opioid analgesic. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;260(1):275–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Driessen B, Reimann W, Giertz H. Effects of the central analgesic tramadol on the uptake and release of noradrenaline and dopamine in vitro. Br J Pharmacol. 1993;108(3):806–811. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb12882.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb12882.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bilir A, Erkasap N, Koken T, Gulec S, Kaygisiz Z, Tanriverdi B, et al. Effects of tramadol on myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2007;41(4):242–247. doi: 10.1080/14017430701227747. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14017430701227747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagakannan P, Shivasharan BD, Thippeswamy BS, Veerapur VP. Effect of tramadol on behavioral alterations and lipid peroxidation after transient forebrain ischemia in rats. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2012;22(9):674–678. doi: 10.3109/15376516.2012.716092. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/15376516.2012.716092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yildirim Z, Kotuk M, Erdogan H, Iraz M, Yagmurca M, Kuku I, et al. Preventive effect of melatonin on bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis in rats. J Pineal Res. 2006;40(1):27–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2005.00272.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-079X.2005.00272.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei H, Frenkel K. Relationship of oxidative events and DNA oxidation in SENCAR mice to in vivo promoting activity of phorbol ester-type tumor promoters. Carcinogenesis. 1993;14(6):1195–1201. doi: 10.1093/carcin/14.6.1195. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/carcin/14.6.1195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cortas NK, Wakid NW. Determination of inorganic nitrate in serum and urine by a kinetic cadmium-reduction method. Pt 1 Clin Chem. 1990;36(8):1440–1443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koksel O, Yildirim C, Cinel L, Tamer L, Ozdulger A, Bastürk M, et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase attenuates lung tissue damage after hind limb ischemia-reperfusion in rats. Pharmacol Res. 2005;51(5):453–462. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2004.11.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2004.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rotstein OD. Pathogenesis of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome: gut origin, protection, and decontamination. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2000;1(3):217-23; discussion 223-5. doi: 10.1089/109629600750018141. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/109629600750018141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou JL, Zhu XG, Ling T, Zhang JQ, Chang JY. Effect of endogenous carbon monoxide on oxidant-mediated multiple organ injury following limb ischemia-reperfusion in rats [Article in Chinese] Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2002;16(4):273–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishii H, Ishibashi M, Takayama M, Nishida T, Yoshida M. The role of cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant-1 in neutrophil-mediated remote lung injury after intestinal ischaemia/reperfusion in rats. Respirology. 2000;5(4):325–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Souza DG, Cassali GD, Poole S, Teixeira MM. Effects of inhibition of PDE4 and TNF-alpha on local and remote injuries following ischaemia and reperfusion injury. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;134(5):985–994. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704336. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjp.0704336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Welbourn R, Goldman G, O'Riordain M, Lindsay TF, Paterson IS, Kobzik L, et al. Role for tumor necrosis factor as mediator of lung injury following lower torso ischemia. J Appl Physiol. 1991;70(6):2645–2649. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.70.6.2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tassiopoulos AK, Carlin RE, Gao Y, Pedoto A, Finck CM, Landas SK, et al. Role of nitric oxide and tumor necrosis factor on lung injury caused by ischemia/reperfusion of the lower extremities. J Vasc Surg. 1997;26(4):647–656. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(97)70065-x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0741-5214(97)70065-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crinnion JN, Homer-Vanniasinkam S, Gough MJ. Skeletal muscle reperfusion injury: pathophysiology and clinical considerations. Cardiovasc Surg. 1993;1(4):317–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carden DL, Granger DN. Pathophysiology of ischaemia-reperfusion injury. J Pathol. 2000;190(3):255–266. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(200002)190:3<255::AID-PATH526>3.0.CO;2-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(200002)190:3 <255::AID-PATH526>3.0.CO;2-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fryer RM, Hsu AK, Eells JT, Nagase H, Gross GJ. Opioid-induced second window of cardioprotection: potential role of mitochondrial KATP channels. Circ Res. 1999;84(7):846–851. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.7.846. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/01.RES.84.7.846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nebigil CG, Etienne N, Messaddeq N, Maroteaux L. Serotonin is a novel survival factor of cardiomyocytes: mitochondria as a target of 5-HT2B receptor signaling. FASEB J. 2003;17(10):1373–1375. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1122fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bianchi P, Pimentel DR, Murphy MP, Colucci WS, Parini A. A new hypertrophic mechanism of serotonin in cardiac myocytes: receptor-independent ROS generation. FASEB J. 2005;19(6):641–643. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2518fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Groban L, Vernon JC, Butterworth J. Intrathecal morphine reduces infarct size in a rat model of ischemia-reperfusion injury. Anesth Analg. 2004;98(4):903–909. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000105878.96434.05. http://dx.doi.org/10.1213/01.ANE.0000105878.96434.05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McPherson BC, Yao Z. Signal transduction of opioid-induced cardioprotection in ischemia-reperfusion. Anesthesiology. 2001;94(6):1082–1088. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200106000-00024. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00000542-200106000-00024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ellmauer S, Dick W, Otto S, Müller H. Different opioids in patients at cardiovascular risk. Comparison of central and peripheral hemodynamic adverse effects [Article in German] . Anaesthesist. 1994;43(11):743–749. doi: 10.1007/s001010050117. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s001010050117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yassin MM, Barros D'Sa AA, Parks G, Abdulkadir AS, Halliday I, Rowlands BJ. Mortality following lower limb ischemia-reperfusion: a systemic inflammatory response? World J Surg. 1996;20(8):961-6; discussion 966-7. doi: 10.1007/s002689900144. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s002689900144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yassin MM, Harkin DW, Barros D'Sa AA, Halliday MI, Rowlands BJ. Lower limb ischemia-reperfusion injury triggers a systemic inflammatory response and multiple organ dysfunction. World J Surg. 2002;26(1):115–121. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0169-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00268-001-0169-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sirmali M, Uz E, Sirmali R, KilbaÅŸ A, Yilmaz HR, AÄŸaçkiran Y, et al. The effects of erdosteine on lung injury induced by the ischemia-reperfusion of the hind-limbs in rats. J Surg Res. 2008;145(2):303–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2007.02.027. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2007.02.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]